Abstract

Objective

To define the accuracy of administrative datasets to identify primary diagnoses of breast cancer based on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9th or 10th revision codes.

Design

Systematic review.

Data sources: MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science and the Cochrane Library (April 2017).

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were: (a) the presence of a reference standard; (b) the presence of at least one accuracy test measure (eg, sensitivity) and (c) the use of an administrative database.

Data extraction

Eligible studies were selected and data extracted independently by two reviewers; quality was assessed using the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic accuracy criteria.

Data analysis

Extracted data were synthesised using a narrative approach.

Results

From 2929 records screened 21 studies were included (data collection period between 1977 and 2011). Eighteen studies evaluated ICD-9 codes (11 of which assessed both invasive breast cancer (code 174.x) and carcinoma in situ (ICD-9 233.0)); three studies evaluated invasive breast cancer-related ICD-10 codes. All studies except one considered incident cases.

The initial algorithm results were: sensitivity ≥80% in 11 of 17 studies (range 57%–99%); positive predictive value was ≥83% in 14 of 19 studies (range 15%–98%) and specificity ≥98% in 8 studies. The combination of the breast cancer diagnosis with surgical procedures, chemoradiation or radiation therapy, outpatient data or physician claim may enhance the accuracy of the algorithms in some but not all circumstances. Accuracy for breast cancer based on outpatient or physician’s data only or breast cancer diagnosis in secondary position diagnosis resulted low.

Conclusion

Based on the retrieved evidence, administrative databases can be employed to identify primary breast cancer. The best algorithm suggested is ICD-9 or ICD-10 codes located in primary position.

Trial registration number

CRD42015026881.

Keywords: breast cancer, administrative database, validity, accuracy, sensitivity and specificity, systematic review

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Based on a prepublished protocol, this is the first review that systematically addressed the accuracy of administrative databases in identifying subjects with breast cancer.

We performed a comprehensive electronic databases search complemented with reference check of relevant articles, and we evaluated the quality of reporting of included studies by the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic checklist.

We considered only papers written in English and this might have introduced a language bias.

The knowledge and experience of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9/ICD-10 coders could have influenced the quality of breast cancer case definition in each study, and consequently the results presented in our review could be biased by this factor.

Generalisability of validated administrative databases is limited to the context in which they are generated.

Introduction

The burden of cancer is increasingly growing among populations, and it is associated with major economic expenditure worldwide,1 especially in low-income and middle-income countries.2

As breast cancer is the most common cancer and the leading cause of cancer death in women,3 knowledge of its epidemiology and the ability to monitor related outcomes over time is important for health planning services. Administrative healthcare databases are increasingly being used in oncology for epidemiological evaluation,4 population outcome research,5 drug utilisation reviews,6–8 evaluation of health service delivery and quality9 10 as well as health policy development.11–13 Generally, these databases gather longitudinal information concerning health resource utilisation regarding hospitalisations, outpatient care and, often, drug prescriptions and vital statistics.14 In other words, these databases provide a readily available source of ‘real-world’ data on a large population of unselected patients allowing the performance of less expensive and more representative assessment of disease surveillance and outcome research compared with randomised trials.15 16

By definition, administrative healthcare databases contain data that are routinely and passively collected without an a priori research question, as they are usually established for billing or, in general, for administrative purposes, and not for research uses. Hence, the diagnostic codes used to identify, for example, cancers, must be validated according to an accepted ‘reference standard’ diagnosis.17 In validation studies of administrative databases, the reference standard usually used is the clinical chart or cancer registry.18

The current International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, (ICD-9) codes are 233.0 for breast carcinoma in situ and 174.0–174.9 for invasive breast cancer, whereas the ICD-10 codes are D05.0-D05.9 and C50.0-C50.9, respectively. These codes help to identify subjects that have breast cancer within an administrative healthcare database. Since the clinical diagnosis of breast cancer is based on a combination of clinical and/or instrumental examinations and a pathological assessment,19 these codes are limited in confirming whether a specific subject within the databases truly has the disease of interest. As a result, researchers have proposed a number of different claim-based algorithms for case identification of breast cancers, such as a combination of healthcare claims data,20 the use of chemotherapy21 and the number of medical claims on separate dates.11 In addition, since patients with metastatic cancer have different prognoses and typically different treatment patterns to those with earlier-stage malignancies, researchers suggest using algorithms to identify patients with metastatic cancer.11 22

To our knowledge, data on the validity of breast cancer diagnosis codes have not been synthesised in the medical literature. Our objective was to determine the best algorithms with which to identify breast cancer cases using administrative databases based on a comprehensive systematic search of primary studies that validated ICD-9 or ICD-10 codes related to breast cancer. The present work has been conceived within a project of validating three large administrative healthcare databases in Italy concerning ICD-9-CM codes for breast, colorectal and lung cancers.23–25 For our purposes, it was important to identify all available case definitions or algorithms that best identify subjects with the cancer diseases of interest as outlined in our protocol.26

Methods

This study is part of different projects supported by national and local funding with the objectives of assessing case definitions of diseases as well as validating ICD-9 codes for cancer23 26 and other diseases.27–29

As outlined in the protocol,26 the target population consisted of patients with primary diagnosis of breast cancer, the index test was represented by administrative data algorithms related to breast cancer, the reference standard was represented by medical charts, validated electronic health records or cancer registries.

Literature search

Comprehensive searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science and the Cochrane Library from their inception to April 2017 were performed to identify published peer-reviewed literature. We developed a search strategy based on the combination of: (a) keywords and Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms to identify records concerning breast cancer; (b) terms to identify studies likely to contain validity or accuracy measures and (c) a search strategy designed to capture studies that used healthcare administrative databases based on the combination of terms used by Benchimol et al30 and the Mini-Sentinel’s program.31 32 The developed search strategy is reported in the online supplementary file 1. To retrieve additional articles, the authors searched relevant reference lists of key articles. Titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility by two independent reviewers. Discrepancies were solved by discussion.

bmjopen-2017-019264supp001.pdf (93.2KB, pdf)

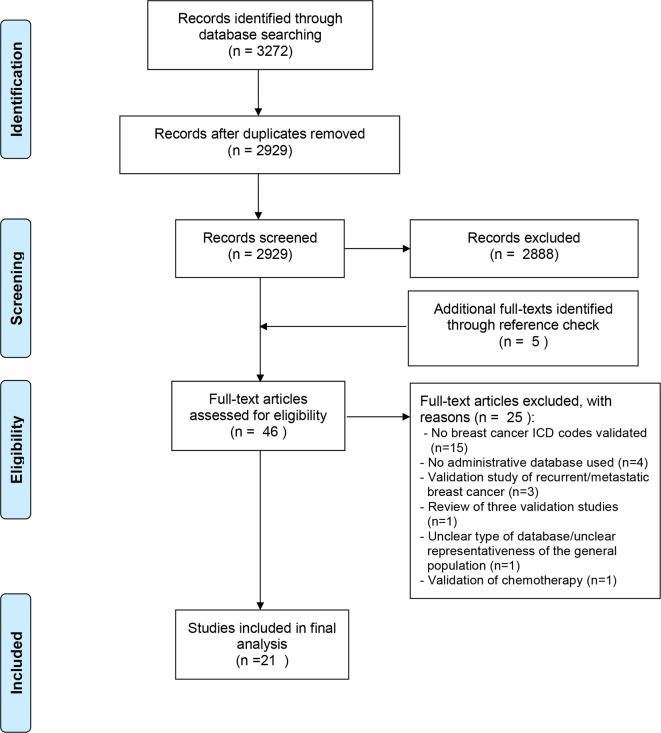

This systematic review was prepared according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 Statement33 and the results were presented following the PRISMA flow diagram (figure 1).34 A protocol of this review has also been published at the BMJ Open26 as well as an outline in the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of systematic reviews with registration number CRD42015026881 (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO).

Figure 1.

Study screening process.

Inclusion criteria

Full texts of eligible peer-reviewed articles without publication date restriction, published in English that used administrative data for the ICD-9 or ICD-10 codes related to breast cancer diagnoses were obtained. For each study, the following inclusion criteria were applied: (a) the presence of a reference standard (clinical chart, cancer registry or electronic health records), together with the presence of any case definition or algorithm for breast cancer; (b) the presence of at least one test measure (eg, sensitivity, positive predictive value (PPV), etc); (c) the data source was from an administrative database (ie, a database in which data are routinely and passively collected without an a priori research question) and (d) the study database was from a representative sample of the general population.

We aimed to focus on primary diagnosis of breast cancers, hence studies that considered algorithms to identify cancer history, cancer progression or recurrence were not evaluated.

In addition, studies that considered index test databases that were not truly administrative (eg, cancer registries, epidemiology surveillance systems, etc) were excluded. However, studies that used electronic health records to validate breast cancer were also included.35 36

Selection process

After screening titles and abstracts, we subsequently obtained full texts of eligible articles to determine if they meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria. We conducted data abstraction using standardised data collection forms that were tested on a sample of three eligible articles. Two review authors working independently and in duplicate were involved in titles and abstracts screening, full-texts screening and data abstraction (FC, MO, AG, VS). Discrepancies were resolved by consensus, and where necessary with the involvement of a third review author (IA). Calibration exercises were performed at each level of the process.

Data extraction

Data extraction included the following information: the details of the included study (including title, year and journal of publication, country of origin and sources of funding; the type of disease (invasive, in situ or both); the target population from which the administrative data were collected; the type of administrative database used (eg, hospitalisation discharge data), outpatient records (eg, physician billing claims); the ICD-9 or ICD-10 codes used or the administrative data algorithms tested (including Current Procedural Terminology; prescription fills, etc); the position of the ICD codes in the discharge abstract database (ICD codes in primary position indicate the principal diagnosis, that is, the condition identified at the end of the admission, which is the main cause of the need for treatment or diagnostic investigations; ICD codes in secondary positions refer to secondary diagnoses, that is, conditions that coexist at the time of the admission or which develop after that time and which influence the treatment received and/or the length of hospital stay); the modality of development of the algorithm (eg, using Classification and Regression Trees, logistic regression, expert opinion, etc); external validation; use of training and testing cohorts; the reference standard used to determine the validity of the diagnostic codes (eg, medical chart review, patient self-reports, cancer registry, etc); the characteristic of the test used to determine the validity of the diagnostic code or algorithm (eg, sensitivity, specificity, PPVs and negative predictive values (NPVs), area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, likelihood ratios and kappa statistics).

Quality assessment

The design and methods of the included primary studies were assessed using a checklist developed by Benchimol et al,30 based on the criteria published by the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic accuracy (STARD) initiative for the accurate reporting of studies using diagnostic studies.37 The checklist is provided in online supplementary file 2. The presence of potential biases within the studies were reported in a descriptive way.

bmjopen-2017-019264supp002.pdf (93.9KB, pdf)

Analysis

For each algorithm, we abstracted the performance statistics provided in the included studies including sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV. Where necessary, we calculated validation statistics together with their 95% CIs as far as raw numbers for cases and controls were provided.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not directly involved. This was a retrospective study based on the consultation of electronic medical literature.

Results

Literature search

After removing duplicate records identified through MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science and The Cochrane Library, 2929 citations were screened in titles and abstracts. Overall, we assessed 41 full-text articles for eligibility, of which 1710 38–53 were included in the final evaluation. In addition, a reference check of pertinent articles permitted the identification of five potentially relevant studies of which four were included in the final analysis54–57 (figure 1). The list of excluded studies, together with the reasons of their exclusion is reported in the online supplementary file 3.

bmjopen-2017-019264supp003.pdf (92.4KB, pdf)

Study characteristics

The included studies were published between 1992 and 2015 and collected data between 1977 and 2011. Fifteen studies were performed in the USA,39 41 42 44–47 51–53 55–59 two were conducted in Italy,10 38 two in France,40 54 one in Japan49 and one in Australia.43 Seventeen studies used Cancer Registry data as the reference standard,38–40 42 43 45–47 49–57 60 four studies used medical chart review.45 50 51 57

Eighteen studies10 38 39 41 42 44–48 50–57 evaluated ICD-9 codes, and three studies40 43 49 evaluated ICD-10 codes. Of the studies that evaluated ICD-9 codes, 11 reported the evaluation of the ICD-9 codes related to invasive breast cancer (code 174.x) and carcinoma in situ (ICD-9 233.0)10 38 42 44–47 50–53; three evaluated only invasive cancer (ICD-9 174.x)39 41 55; three studies did not specify the number of the ICD-9 codes evaluated.54 56 57 Three studies evaluated ICD-10 codes for invasive breast cancer without evaluating carcinoma in situ codes.40 43 49

In terms of representativeness or generalisability, the studies varied greatly. Eight studies considered all women beneficiaries of the Medicare programme, USA), age 65 years or above residing in specific areas,39 42 46 51–53 55 56 nine studies considered all women with any age38 49 or aged 15+54 or 20+10 38 40 45 50 57 in specific areas, two studies considered all women aged 40+44 or 45+43 residing in specific areas and three studies randomly sampled residents at a national level,41 or residents at regional level.47 59

Basic characteristics of these studies are displayed in table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| First author, year of publication | Period of data collection | Country | Records evaluated (N) | Source population | Type of administrative data | Diagnostic codes | Algorithm | Reference standard |

| Fisher et al41 1992 | 1984–1985 | USA | 33 cases (any position); 24 cases (first position) from each 239 hospitals | All National Medical beneficiaries, | Medicare claim database: inpatient hospital discharge. | 174–174.9 | (a) Diagnosis in any position. (b) Diagnosis in primary position. |

Medical records review |

| McBean et al55 1994 | 1986–1987 | USA | 5744 cases | Persons 65 years of age and older living in the five states participating in the SEER Program. | Medicare claim database: inpatient hospital data. | 174–174.9 | New cases of breast cancer with diagnostic codes in any position. | Cancer Registry (SEER) |

| Solin et al50 1994 | 1988–1989 | USA | 469 cases | Women aged ≥21 years enrolled in the USA. Healthcare in the southeastern Pennsylvania region. | Claims database included inpatient hospital stays, short procedure unit stays and professional services. Each claim included the USA (comprised ICD-9 code and CPT-4). | 174–174.9; 233.0 | (A) Initial algorithm based on new case of breast carcinoma+one or more of the following: (1) mastectomy, (2) partial mastectomy with lymphadenectomy, (3) excision, breast biopsy or partial mastectomy+lymphadenectomy, (4) excision, breast biopsy or partial mastectomy+the diagnosis of carcinoma of the breast, (5) excision, breast biopsy or partial mastectomy followed by radiation therapy treatment or (6) excision, breast biopsy or partial mastectomy followed by chemotherapy treatment. (B) Best algorithm with multiple modifications of the initial algorithm. |

Medical records review |

| Warren et al53 1996 | 1989 | USA | 3454 cases | All women aged 65+ years with one or more hospitalisations with a diagnosis of breast cancer in Medicare. | Medicare Hospital Inpatient (ICD-9-CM). | 174–174.9; 233.0 | (i) Any hospitalisation breast cancer (ICD-9-CM 174–174.9 and 233.0) as principal diagnosis. (ii) Incident cases of breast cancer (no prior hospitalisation with breast cancer in any of the 5 positions from 1984 to 1988 or history of breast cancer (ICD-9-CM V.10.3) appearing as any of the five positions from 1984 to 1989). (iii) Analysis limited to women who were residents in one of the five SEER states. |

Cancer Registry (SEER) |

| Solin et al51 1997 | 1993–1994 | USA | 177 cases | All women aged ≥65 years enrolled in the US Healthcare (Pennsylvania and New Jersey). | Claims database included hospital inpatient, short procedure unit stays and professional services (ICD-9 diagnosis code, and the CPT-4 procedure code). | 174–174.9; 233.0 | This study was performed to evaluate prospectively a previously published algorithm50 used to identify women with the new diagnosis of carcinoma of the breast. | Medical records review |

| McClish et al46 1997 | 1986–1989 | USA | 3690 cases | All residents aged 65+ years diagnosed with breast cancer (Virginia). | MEDPAR (Medicare) inpatient hospital claim database (ICD- 9 CM). | 174–174.9; 233.0 | Incident cases of breast cancer ICD-9-CM 174; V174.9; 233 and 233.0. | Cancer Registry |

| Cooper et al61 1999 | 1984–1993 | USA | 71 862 cases | All women aged 64+ years with breast cancer (Atlanta, Detroit, Seattle-Puget Sound, San Francisco Oakland, Connecticut, Hawaii, Iowa, New Mexico and Utah). | (1) MEDPAR (Medicare: inpatient hospital claim database (ICD-9 CM and specific procedural codes ICD-9-CM and HCPCS/CPT-4. (2) Part B: physician and outpatient claim data. |

174–174.9 |

Basic: incidence breast cancer (174.0–174.9); (i) all other inpatient diagnostic codes; inpatient cancer-specific surgical code (local excision/lumpectomy: 85.20, 85.21, 85.22); Part B: first position diagnosis code; any other part B diagnosis codes and part B cancer-specific surgical code; (ii) first position diagnostic coding+the inclusion of the following: all other part B diagnosis codes; part B cancer-specific procedural code; inpatient first position diagnosis; all other inpatient diagnoses and inpatient cancer-specific surgery. |

Cancer Registry (SEER) |

| Warren et al52 1999 | 1992 | USA | Women residing in the SEER states n=6 59 260; cases=6784. | All Medicare eligible women residing in one of five SEER states who were age 65 years and older as of 1 January 1992. | Medicare inpatient and physician claim database (ICD-9). | 174–174.9; 233.0 |

Model 1: inpatient primary diagnosis (174–174.9, 233.0), excluding prevalent cases), inpatient-secondary diagnosis, and physician bills—reference group). Model 2: inpatient-secondary diagnosis and cases identified from the physician data, breast cancer-related procedures. |

Cancer Registry (SEER) |

| Leung et al45 1999 | 1994–1996 | USA | 1033 cases | All women aged 21 years or older who were enrolled in Health Net (California). | Claims database includes claims received for inpatient hospital stays, short procedure unit stays and professional services (code ICD-9-CM). | 174–174.9; 233.0 | Basic breast cancer diagnosis and one of the following: (1) mastectomy; (2) partial mastectomy with lymphadenectomy; (3) excision, breast biopsy or partial mastectomy+lymphadenectomy; (4) excision, breast biopsy or partial mastectomy+diagnosis of carcinoma; (5) excision, breast biopsy or partial mastectomy followed by radiation therapy or (6) excision, breast biopsy or partial mastectomy followed by chemotherapy. | Medical chart review |

| Freeman et al42 2000 | 1990–1992 | USA | 7464 cases; 1415 controls: | Females aged 65–74 years (in 1992) diagnosed with breast cancer (San Francisco/Oakland, Detroit, Atlanta and Seattle and the states of Connecticut, Iowa, New Mexico, Utah and Hawaii). | ICD-9 inpatient record; outpatient record; physician claim (Medicare). | 174–174.9; 233.0; V103 | Model 1 (6 predictors): hospital inpatient: breast cancer principal or additional diagnosis) or 1992 hospital. Model 2: (10 predictors) (model 1 or breast cancer-related procedure (mastectomy, partial mastectomy, excisional biopsy, incisional biopsy). Model 3 (36 predictors): (hospital inpatient, hospital outpatient, physician claim): model 1 and breast cancer-related procedure (mastectomy biopsy, biopsy, chemotherapy); mammography, breast cancer-related radiology, radiation oncology, laboratory test on a hospital outpatient. Model 4 (hospital inpatient, hospital outpatient, physician claim): model 1 and breast cancer-related procedure (mastectomy biopsy, biopsy, chemotherapy); mammography, breast cancer-related radiology, radiation oncology, laboratory test on a hospital outpatient; biopsy, radiation oncology, laboratory test on a physician claim; mammography, other radiological procedures in 1992 on a hospital outpatient claim. |

Cancer Registry (SEER) |

| Wang et al57 2001 | 1989–1991 | USA | 8872 cases | All women aged 20 years and older who were enrolled in either Medicaid or Medicare and PAAD (New Jersey State). | Medicaid in patient files. | ICD-9 code: not reported | New cases of breast cancer: primary algorithm definitions:: surgical claims for (a) a CPT or ICD-9 procedure code for a mastectomy; (b) a CPT or ICD-9 procedure code for an excision of a breast mass+CPT or ICD-9 procedure code for an axillary node biopsy; (c) a DRG hospitalisation code for breast cancer surgical hospitalisation. Alternative algorithms: combinations of ICD-9 diagnostic codes, DRG hospitalisation codes, and codes for non-surgical treatments. |

Cancer registry |

| Koroukian et al44 2003 | 1997–1998 | USA | 2635 incident cases | Women aged 40 years or older (Ohio). | Medicaid claims and enrolment files. ICD-9-CM. | 174–174.9; 233.0 | Incident of breast cancer (ICD-9 174.0–174.9 233.0) and combinations of diagnosis and procedures codes (chemotherapy or radiation therapy, mastectomy, lumpectomy). | Cancer Registry (OCISS) |

| Ganry et al54 2003 | 1998 | France | 198 incident cases | All women aged 15 years or older who were diagnosed or treated (in the Amiens University Hospital and five general hospitals) of the Somme area. | French hospital database adapted from the Diagnosis Related Group (DRG). | ICD-9 code: not reported | New case of breast cancer—at least one of the following criteria: (a) breast cancer as primary diagnosis, alone or with (i) mastectomy; (ii) partial mastectomy with lymphadenectomy or (iii) excision, breast biopsy or partial mastectomy for procedures; (b) breast cancer as secondary diagnosis, with (i) chemotherapy as principal diagnosis or (ii) without specific procedures (excluding prevalent cases: women with history of breast cancer between 1991 and 1997). | Cancer registry (French Somme Area) |

| Nattinger et al47 2004 | Validation set: 1994; training set: 1995 | USA | 7607 cases and 120 317 controls | Training set: claims from 7700 SEER-Medicare breast cancer subjects (age 65+ years) diagnosed in 1995, and 124 884 controls. Validation set: claims from 7607 SEER-Medicare breast cancer subjects diagnosed in 1994, and 120 317 controls. |

Random sample; ICD-9 inpatient record; outpatient record; physician claim (Medicare). | 174–174.9; 233.0 | Four-step algorithm: (1) breast cancer diagnosis+procedure code; (2) both conditions: (a) mastectomy or a lumpectomy or partial mastectomy followed by at least one outpatient or carrier claim for radiotherapy with a breast cancer diagnosis; (b) at least two outpatient or carrier claims on different dates containing breast cancer as the primary diagnosis; (3) this step applies to all potential cases that passed step 1, but were not directly included at step 2; (4) removal of prevalent cases. |

Cancer Registry (SEER) |

| Penberthy et al59 2005 | 1995 | USA | 249 cases | Women aged 65+ years with breast cancer diagnosis. | (a) lnpatient Medicare; (b) inpatient or Part B claims. | ICD-9 174 | Six case definitions: A1) diagnosis first position; A2) inpatient diagnosis in any position; A3) inpatient diagnosis in any position+inpatient surgical procedure; B1) inpatient diagnosis in any position+inpatient surgical procedure; B2) inpatient diagnosis in any position+inpatient surgical procedure OR a diagnostic procedure+diagnosis+a surgery or chemotherapy or radiation therapy procedure in an outpatient or physician office record within 4 months of a diagnostic procedure; B3) inpatient diagnosis in any position OR a diagnosis+a surgery or chemotherapy or radiation therapy procedure in an outpatient or physician office record. | Cancer Registry (Virginia State); medical chart review |

| Setoguchi et al56 2007 | 1997–2000 | USA | 2004 cases | Subjects aged 65+ years Medicare recipients in Pennsylvania. | Medicare inpatient hospital claim and drug benefit programme data. | Unclear | Four algorithms based on the combination of the following: (a) ICD-9 diagnosis codes (numbers not provided), (b) CPT codes for screening procedures, surgical procedures, radiation therapy, chemotherapy and nuclear medicine procedures and/or (c) National Drug Code prescription codes for medications used for cancer treatment available in Pharmaceutical Assistance Contract for the Elderly. | Cancer Registry (Pennsylvania State) |

| Baldi et al38 2008 | 2000 training set, 2001 validation set | Italy | 925 cases | All residents in Piedmont region. | Regional inpatient administrative database. | 174–174.9; 233.0 | Algorithms based on combination between (i) ICD-9-CM diagnosis breast cancer (invasive 174.0–174.9, in situ 233.0); and ICD-9-CM procedures code incisional breast biopsy: 85.12 excision or destruction of breast tissue: 85.20–85.25 subcutaneous mastectomy: 85.33–85.36 mastectomy: 85.41–85.48 | Cancer Registry (Piedmont Region) |

| Couris et al40 2009 | 2002 | France | 995 cases | Women aged 20 years or older living in one of the nine French districts covered by a cancer registry in 2002. | Inpatient hospital administrative data (French National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies) based on ICD-10. |

C50.0 to C50.9 | (a) Principal diagnosis for invasive breast cancer—ICD-10 codes C50.0 to C50.9; (b) principal diagnosis+specific surgery procedures. | French cancer registries |

| Yuen et al10 2011 | 2002–2005 | Italy | 11 615 cases | Women aged 20 years older with incident breast cancer (Emilia-Romagna region). | Regional administrative database (Hospital discharge files). | 174–174.9; 233.0 | Women having a diagnosis code for cancer as well as a principal or secondary surgical code for lumpectomy or mastectomy: principal or secondary procedure indicating excision or destruction of breast tissue (ICD-9-CM code 85.20–85.25) or mastectomy (ICD-9-CM code 85.41–85.48); and principal or secondary diagnosis of carcinoma in situ of the breast (ICD-9-CM code 233.0) or malignant neoplasm of the breast (ICD-9-CM code 174.0–174.9). | Cancer registry (AIRTUM) |

| Kemp et al43 2013 | 2004–2008 | Australia | 2039 women with invasive breast tumour | Women aged 45+ years who had completed breast cancer-related items in the baseline survey of the 45 and up study (New South Wales). | i) Administrative hospital separations records (ICD-10-AM); ii) outpatient medical service claims; iii) prescription medicines claims and iv) the 45 and up study baseline survey. | C50.0 to C50.9 | Principal inpatient diagnosis of invasive breast cancer using ICD-10- AM codes C50.0-C50.9. | Cancer Registry |

| Sato et al49 2015 | 2011 | Japan | 50 056 women included in the study cohort (633 with breast cancer) | Women with no prior cancer-related history, from the claims data at a single institution between 1 January and 31 December 2011. | ICD for oncology, third edition (ICD-O-3): topography code of breast cancer (C500 to C506, C508, C509). | C50.0 to C50.9 | 14 definitions starting from (1) breast cancer alone and subsequent addition of (2) diagnosis code related to breast cancer (3) diagnostic imaging code (4) biopsy code (5) marker test code (6) surgery code (7) chemotherapy code (8) medication code (9) radiation procedure code (10) the other code related to breast cancer (11) diagnosis code related to breast cancer or marker test code (12) surgery, chemotherapy, medication or radiation procedure code (13) diagnosis code related to the breast cancer, marker test code, surgery, chemotherapy, medication or radiation procedure code (14) ≥3 diagnoses of breast cancer. | Cancer Registry |

AIRTUM, Associazione Italiana dei Registri Tumori; CPT-4: current procedural terminology-4; HCPCS, Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; MEDPAR, Medicare Annual Demographic Files, the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review; OCISS, Ohio Cancer Incidence Surveillance System; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program.

Validity of breast cancer data

Accuracy results by initial algorithms

All the studies considered new (incident) breast cancer cases except Fisher et al.41 Nineteen studies presented the initial accuracy results based on breast cancer diagnosis only; in 18 studies the diagnosis was in primary position,10 38–50 52–54 56 in 1 study in any position55 and in 2 studies the position was unclear,51 57 whereas 2 studies evaluated breast cancer diagnosis with surgical procedures.10 38

Sensitivity was reported by 17 studies, and was at least 80% in 65% (n=11) of them10 41 43 44 46 47 49 53–55 57 (range 57%–99%). PPV, obtained from 19 studies, was ≥83% in the majority (n=14) of them (range 15%–98%). Specificities resulted higher than 98% in all the eight studies that provided sufficient data to permit calculation.10 40 43 47 49 52 54 56 Similarly, the NPV for the five studies for which it was possible to calculate was ≥99%.40 43 52 54 56 Table 2 displays the results of the algorithm with which the studies presented their initial data stratified by ICD codes.

Table 2.

Accuracy results by initial algorithm in the 21 included studies

| Study ID | Initial algorithm | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) |

| ICD-9 | |||||

| Fisher et al41 1992 | BCD in primary position | 96 (79 to 100) | 88 (70 to 98) | ||

| McBean et al55 1994 | BCD in any position | 97 | 96 | ||

| Solin et al50 1994 | BCD in primary position | 88 (85 to 91) | |||

| Warren et al53 1996 | BCD in primary position | 94 (93 to 95) | 97 | 83 (78 to 89) | |

| McClish et al46 1997 | BCD in primary position | 83 (82 to 84) | 91 (90 to 93) | ||

| Solin et al51 1997 | BCD (unclear position) | 83 (77 to 87) | |||

| Leung et al45 1999 | BCD in primary position | 84 (82 to 87) | |||

| Warren et al52 1999 | BCD in primary position | 57 (55 to 59) | 99 (99 to 99) | 91 (90 to 93) | 99 (98 to 100) |

| Cooper et al61 1999 | BCD in primary position | 68 (68 to 69) | |||

| Freeman et al42 2000 | BCD in primary position | 68 (66 to 70) | 74 (72 to 76) | ||

| Wang et al57 2001 | BCD (unclear position) | 89 (88 to 90) | |||

| Koroukian et al44 2003 | BCD in primary position | 69 (66 to 71) | 15 (13 to 17) | ||

| Ganry et al54 2003 | BCD in primary position | 85 (80 to 90) | 100 (100 to 100) | 98 (94 to 99) | 100 (100 to 100) |

| Nattinger et al47 2004 | BCD in primary position | 80 (79 to 81) | 100 (100 to 100) | 89 (87 to 92) | |

| Penberthy et al59 2005 | BCD in primary position | 53 | 96 | ||

| Setoguchi et al56 2007 | ≥1 BCD in primary position | 87 (86 to 89) | 100 (100 to 100) | 50 (49 to 52) | 100 (100 to 100) |

| Baldi et al38 2008 | BCD in primary position+surgical procedures | 74 (71 to 77) | 90 (87 to 92) | ||

| Yuen et al10 2011 | BCD in primary position+surgical procedures | 85 (84 to 86) | 99 (99 to 99) | 91 (90 to 91) | |

| ICD-10 | |||||

| Couris et al40 2009 | BCD in primary position | 69 (66 to 72) | 99 (99 to 99) | 57 (54 to 60) | 100 (100 to 100) |

| Kemp et al43 2013 | BCD in primary position | 86 (85 to 88) | 99 (99 to 99) | 86 (84 to 87) | 100 (100 to 100) |

| Sato et al49 2015 | BCD in primary position | 99 (98 to 100) | 99 (93 to 99) | 66 (63 to 69) | |

BCD, breast cancer diagnosis; ICD, International Classification of Disease; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

Accuracy results by combinations of diagnosis and surgical procedures

Twelve studies reported validation results using algorithms with different combinations.10 38 40 43–45 49–52 54 56 All algorithms, except in two studies,10 38 started evaluating basic breast cancer codes and progressively added surgical procedures, secondary diagnosis, chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy. The addition of one or more of these items to the algorithms produced different results over the basic accuracy results obtained with the use of the diagnosis code alone. The addition of excision to the incident diagnosis of invasive cancer codes did not add any value to the PPV in the studies by Solin et al50 (88% vs 89%), Leung et al45 (83% vs 84%) and Kemp et al43; conversely, in the study by Solin et al51 while in the first algorithm there were no improvements between the new diagnosis and the addition of the excision (83% vs 84%), using the best algorithm set, the PPV rose from 84% to 92% when excision was added to the basic breast diagnosis code. In the study by Koroukian et al,44 the addition of mastectomy or mastectomy/lumpectomy significantly raised the PPV from 15% to 84% and 87%, respectively. In the study by Kemp et al,43 the sensitivity and PPV values of breast cancer diagnosis remained substantially unchanged with the addition of mastectomy, lumpectomy or both (PPV 86% vs 89%). Setoguchi et al56 proposed four algorithms: the algorithm based on one or more diagnoses of breast cancer generated a sensitivity of 87% and a PPV of 50%; the addition of any surgical procedure lowered the sensitivity to 46% but enhanced the PPV to 82%. In the study by Sato et al,49 the addition of any code related to breast cancer, marker tests, surgical procedures, chemotherapy treatment or radiation therapy did not affect the sensitivity (that resulted high: 98%) but raised the PPV from 66% to 83%. Similarly in the study by Ganry et al,54 the addition of any breast or lymph nodal surgical procedures enhanced the PPV from 91% to 98%. Table 3 shows the sensitivities and PPVs with the respective CIs of the studies that in addition to accuracy measures of breast cancer diagnosis also reported accuracy data of surgical procedures.

Table 3.

Results of studies validating diagnoses of breast cancer (first row) and surgical procedures (subsequent rows)

| # | Author/year | Algorithms invasive breast cancer | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV |

| 1 | Solin et al50 1994 | Diagnosis incident cases | – | – | 88 (85 to 91) | – |

| 2 | Solin 1994 | Mastectomy | – | – | 95 (92 to 98) | – |

| 3 | Solin 1994 | Partial mastectomy with lymphadenectomy | – | – | 96 (91 to 100) | – |

| 4 | Solin 1994 | Excision and lymphadenectomy | – | – | 100 (100 to 100) | – |

| 1 | Solin et al51 1997 | Initial algorithm: diagnosis incident cases | – | – | 83 (78 to 89) | – |

| 2 | Solin 1997 | Initial algorithm: mastectomy | – | – | 95 (90 to 100) | – |

| 3 | Solin 1997 | Initial algorithm: partial mastectomy with lymphadenectomy | – | – | 95 (88 to 100) | – |

| 4 | Solin 1997 | Initial algorithm: excision and lymphadenectomy | – | – | 92 (83 to 100) | – |

| 5 | Solin 1997 | Best algorithm: diagnosis incident cases | – | – | 84 (79 to 90) | – |

| 6 | Solin 1997 | Best algorithm: mastectomy | – | – | 82 (76 to 88) | – |

| 7 | Solin 1997 | Best algorithm: partial mastectomy with lymphadenectomy | – | – | 84 (78 to 89) | – |

| 8 | Solin 1997 | Best algorithm: excision and lymphadenectomy | – | – | 84 (78 to 89) | – |

| 1 | McClish et al46 1997 | incident cases identified in MEDPAR | 83 (82 to 84) | – | – | – |

| 2 | McClish 1997 | incident cases identified in VCR | 82 (81 to 83) | – | – | – |

| 3 | McClish 1997 | aggregated (VCR+MEDPAR) | 97 (96 to 97) | – | – | – |

| 4 | McClish 1997 | MEDPAR definitive surgical therapy | 80 (79 to 81) | – | – | – |

| 5 | McClish 1997 | VCR definitive surgical therapy | 87 (86 to 88) | – | – | – |

| 1 | Leung et al45 1999 | Initial algorithm: diagnosis | – | – | 84 (82 to 87) | – |

| 2 | Leung 1999 | Mastectomy | – | – | 92 (90 to 95) | – |

| 3 | Leung 1999 | Partial mastectomy with lymphadenectomy | – | – | 98 (96 to 100) | – |

| 4 | Leung 1999 | Excision, breast biopsy or partial mastectomy plus lymphadenectomy | – | – | 92 (87 to 98) | – |

| 1 | Cooper et al61 1999 | First set of analysis (increase in SE including in order inpatient other diagnosis, surgical, part B, etc): inpatient, first position diagnostic codes | 68 (68 to 69) | – | – | – |

| 2 | Cooper 1999 | First set of analysis: inpatient, surgical | 79 (79 to 79) | – | – | – |

| 3 | Cooper 1999 | First set of analysis: part B, first position | 91 (91 to 91) | – | – | – |

| 4 | Cooper 1999 | First set of analysis: part B, surgical | 94 (93 to 94) | – | – | – |

| 5 | Cooper 1999 | Second set of analysis (increase in SE including in order part B other diagnosis, surgical, inpatient, etc): part B, first position | 66 (66 to 66) | – | – | – |

| 6 | Cooper 1999 | Second set of analysis: part B, other diagnostic codes | 77 (77 to 77) | – | – | – |

| 7 | Cooper 1999 | Second set of analysis: part B, surgical | 81 (81 to 81) | – | – | – |

| 8 | Cooper 1999 | Second set of analysis: inpatient, first position | 91 (91 to 91) | – | – | – |

| 9 | Cooper 1999 | Second set of analysis: inpatient, surgical | 94 (93 to 94) | – | – | – |

| 1 | Freeman et al42 2000 | Primary diagnosis: hospital inpatient in Medicare Provider Analysis (MEDPAR) | 68 (66 to 70) | – | 74 (72 to 76) | – |

| 2 | Freeman 2000 | Mastectomy hospital inpatient | 53 (51 to 56) | – | 73 | – |

| 3 | Freeman 2000 | Partial mastectomy hospital inpatient | 7 (4 to 11) | – | 64 | – |

| 4 | Freeman 2000 | Excisional biopsy hospital inpatient | 8 (5 to 12) | – | 56 | – |

| 5 | Incisional biopsy hospital inpatient | 8 (5 to 11) | – | 73 | – | |

| 1 | Ganry et al54 2003 | Hospitalisation with breast cancer as primary diagnosis: mastectomy | – | – | 100 (100 to 100) | – |

| 2 | Ganry 2003 | Hospitalisation with breast cancer as primary diagnosis: partial mastectomy with lymphadenectomy | – | – | 100 (100 to 100) | – |

| 3 | Ganry 2003 | Hospitalisation with breast cancer as primary diagnosis: biopsy/excision plus the diagnosis of carcinoma | – | – | 100 (100 to 100) | – |

| 1 | Kemp et al43 2013 | Diagnosis of invasive breast cancer | 86 (85 to 88) | 100 (100 to 100) | 86 (84 to 87) | 100 (100 to 100) |

| 2 | Kemp 2013 | Lumpectomy | 61 (59 to 63) | 99 (99 to 99) | 52 (50 to 54) | 99 (99 to 99) |

| 3 | Kemp 2013 | Mastectomy | 33 (31 to 35) | 100 (100 to 100) | 71 (68 to 74) | 99 (99 to 99) |

| 4 | Kemp 2013 | Lumpectomy OR mastectomy | 84 (83 to 86) | 99 (99 to 99) | 56 (55 to 58) | 100 (100 to 100) |

MEDPAR, Medicare Annual Demographic Files, the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; VCR, Virginia Cancer Registry.

Accuracy results by combinations of diagnosis and surgical procedures followed by chemoradiation or radiation therapy

Six studies added chemotherapy or radiation therapy procedures to their algorithm.44 45 49–51 54 Compared with the initial algorithm with only the diagnosis of breast cancer, the PPV value increased in all instances to values higher than 94% in four studies.45 50 51 54 However, in all studies except one the algorithms contained surgical procedures. Table 4 displays the sensitivity and PPV values for the studies that combined chemoradiation or radiation therapy procedures with diagnosis of breast cancer.

Table 4.

Results of studies that combined surgical procedures followed by chemoradiation or radiation therapy with diagnosis of breast cancer

| N | Author/year | Algorithms invasive breast cancer | Sensitivity % (CI) |

Specificity % (CI) |

PPV % (CI) |

| 1 | Solin et al50 1994 | Diagnosis incident cases | – | – | 88 (85 to 91) |

| 2 | Solin 1994 | Excision followed by radiation therapy | – | – | 94 (88 to 99) |

| 3 | Solin 1994 | Excision followed by chemotherapy | – | – | 94 (88 to 100) |

| 1 | Solin et al51 1997 | Initial algorithm: diagnosis incident cases | – | – | 83 (78 to 89) |

| 2 | Solin 1997 | Initial algorithm: excision followed by radiation therapy treatment | 97 (91 to 100) | ||

| 3 | Solin 1997 | Initial algorithm: excision followed by chemotherapy | – | – | 90 (77 to 100) |

| 4 | Solin 1997 | Best algorithm: diagnosis incident cases | – | – | 84 (79 to 90) |

| 5 | Solin 1997 | Best algorithm: excision followed by radiation therapy treatment | – | 84 (78 to 89) | |

| 6 | Solin 1997 | Best algorithm: excision followed by chemotherapy | – | 84 (78 to 89) | |

| 1 | Leung et al45 1999 | Initial algorithm: diagnosis | – | – | 84 (82 to 87) |

| 2 | Leung 1999 | Excision, breast biopsy or partial mastectomy followed by radiation therapy | 96 (94 to 98) | ||

| 3 | Leung 1999 | Excision, breast biopsy or partial mastectomy followed by chemotherapy | 93 (90 to 97) | ||

| 1 | Koroukian et al44 2003 | Incident breast cancer | – | – | 15 (13 to 17) |

| 2 | Koroukian 2003 | Breast cancer diagnosis, chemotherapy or radiation therapy | – | 34 (29 to 39) | |

| 3 | Koroukian 2003 | Breast cancer diagnosis, lumpectomy, chemotherapy or radiation therapy | 85 (78 to 92) | ||

| 1 | Ganry et al54 2003 | Hospitalisation with breast cancer (primary diagnosis): without any procedure | – | – | 91 (81 to 100) |

| 2 | Ganry 2003 | Hospitalisation with breast cancer (secondary diagnosis): chemotherapy as primary diagnosis | – | – | 98 (94 to 100) |

| 1 | Sato et al49 2015 | Diagnosis of breast cancer | 99 (99 to 100) | 99 (93 to 100) | 66 (63 to 69) |

| 2 | Sato 2015 | Diagnosis of breast cancer+diagnosis code related to the breast cancer, marker test code, surgery, chemotherapy, medication or radiation procedure code | 97 (96 to 100) | 100 (100 to 100) | 83 (80 to 85) |

PPV, positive predictive value.

Accuracy results based on the position of the diagnosis

Three studies provided results based on the position of the diagnosis.41 52 54 Fisher et al41 provided sensitivity and PPV for breast cancer diagnosis in any position and it resulted in similar results in the primary position (sensitivity 97% and PPV 84% in any position; sensitivity 96% and PPV 88% in the primary position). Accuracy results for secondary position breast cancer diagnosis was provided by two studies and the estimates resulted lower than the accuracy results for diagnosis in primary position in the studies by Ganry et al54 and Warren et al.52 PPVs were 26% and 65% in secondary position against 91% and 91% in primary position, respectively (see online supplementary file 4, eTable 1).

bmjopen-2017-019264supp004.pdf (24.5KB, pdf)

Accuracy results based on outpatient or physician’s data

Only two studies assessed the accuracy of breast cancer diagnosis codes based on outpatient or physician’s records42 52; the other 19 studies considered inpatient data alone or in combination with other types of data (short procedure unit stays, professional services, prescription medicines claims, etc). For the physician’s mammography and laboratory data, the sensitivities resulted 87% in both cases but with very low corresponding PPV values (0% and 15%, respectively).42 The remaining cases concerning biopsy, surgical procedures, nodal dissection in the physician records or outpatient records showed very low PPVs (see online supplementary file 4, eTable 2).

Stratified analysis by administrative data source, type of ICD code, country of origin and publication year

Accuracy data stratified by setting of diagnosis showed that outpatient accuracy data were much lower than diagnosis in primary position, although the outpatient accuracy data were reported by only one study.42 In terms of codes, both ICD-9 and ICD-10 showed significant variation in both sensitivity and PPV. In terms of country of origin, most of the studies were conducted in the USA where the variability of the accuracy results showed important variation. The studies conducted in Italy10 38 and France40 54 showed similar ranges of sensitivities, whereas the studies conducted in Italy performed better in terms of PPVs than any other country. Accuracy results of the initial algorithm did not change over time and the range of sensitivities remained similar between the studies published before 2001 compared with the studies published after 2000. PPVs estimates remained also similar provided one outlier, that is, the study by Koroukian et al,44 is excluded. Table 5 shows ranges of sensitivities and PPVs stratified by administrative data source, type of ICD code, country of origin and publication year.

Table 5.

Range of sensitivities and PPVs stratified by administrative data source, type of ICD code and country of origin

| Range of sensitivities | Range of PPVs | |

| Administrative data source | ||

| Inpatient (primary position only) | 53%–99% (18 studies) | 15%–98% (19 studies) |

| Outpatient (outpatient diagnosis only) | 9% (1 study) | 19% (1 study) |

| Type of ICD | ||

| ICD-9 (initial algorithm) | 53%–97% (15 studies) | 15%–98% (16 studies) |

| ICD-10 (initial algorithm) | 69%–99% (3 studies) | 57%–86% (3 studies) |

| Country of origin | ||

| USA (initial algorithm) | 53%–97% (12 studies) | 15%–96% (13 studies) |

| Italy (initial algorithm) | 74%–85% (2 studies) | 90%–91% (2 studies) |

| France (initial algorithm) | 69%–85% (2 studies) | 57%–98% (2 studies) |

| Japan (initial algorithm) | 99% (1 study) | 66% (1 study) |

| Australia (initial algorithm) | 86% (1 study) | 86% (1 study) |

| Accuracy over time | ||

| Before 2001 (initial algorithm) | 57%–97% (7 studies) | 74%–96% (9 studies) |

| After 2000 (initial algorithm) | 53%–99% (11 studies) | 15%–98% (10 studies) |

ICD, International Classification of Disease; PPV, positive predictive value.

Quality of the studies

All the studies explicitly reported their intention to evaluate the accuracy of the administrative database and described validation cohort, age, disease and location of participants. All the studies reported inclusion criteria and only seven45 49–51 55 57 59 (33%) did not report exclusion criteria, and three52 53 56 (14%) did not report any description regarding the patient sampling method. In terms of the methodology used, all the studies described the methods used to calculate diagnostic accuracy, none of the studies described number, training and expertise of persons reading reference standards; none of the studies reported the consistency and the number of persons involved in reading reference standards and, of the studies that used the medical chart review as the reference standard only one41 reported the blinding of the interpreters. In terms of statistical methods, all the studies except one55 described adequately the statistics used to obtain accuracy. None of the studies reported at least four estimates of diagnostic accuracy. The most common statistics used to estimate diagnostic accuracy were sensitivity in 17 studies10 38–41 43 44 46 47 49 52–57 59 (81%), PPV in 19 studies10 38 40–47 49–56 59 (90%) and specificity in 9 studies10 40 43 47 49 52–54 56 (43%); 10 studies10 39 44 46 47 49 50 52 53 57 (48%) reported accuracy results for subgroups; and only 6 studies10 38 41 46 47 49 (29%) reported CIs (see online supplementary file 2).

Discussion

Summary of findings

To our knowledge, this is the first review that systematically addressed the validity of algorithms related to breast cancer diseases in administrative databases. Using several medical literature databases, we have identified a significant number of validation studies related to breast cancer disease. Because of the heterogeneity of the results due to the different settings of each included study, we decided to present them in a descriptive manner rather than aggregate them by means of a meta-analysis. Findings from this review suggest that algorithms based on ICD-9 or ICD-10 codes related to breast cancer are accurate in identifying subjects with invasive breast cancer when the diagnosis is in primary position and the algorithm is based on incident cases. Sixty-seven per cent of the studies reported sensitivities or PPVs higher than 80% for inpatient breast cancer code at the initial presentation. The addition of other fields such as surgical procedures, chemotherapy or radiation therapy, outpatient data and physician claims may improve the accuracy results but depend on the accuracy measure used. Breast cancer codes in secondary position yielded lower accuracy values.

Quality of primary studies and heterogeneity

The overall quality of the studies included in our review was judged quite good. There are only some concerns about the items of the modified STARD checklist related to the description of data collection (who identified the patients, who collected data and whether the authors used an a priori data collection form) of which, evaluating the primary studies, we were not able to find these descriptions in the text. However, we do not think that this could significantly affect the results of our review, as it was common to all the studies and it could be related in general to the peculiarity of the studies validating administrative databases that are substantially different from the typical diagnostic accuracy studies.

Regarding reference standard, most of the studies used cancer registries and the confirmation of the cancer disease was based on the presence of the corresponding code within the registry. When medical charts were used as a reference standard, in three studies the diagnosis of carcinoma of the breast was confirmed when there was evidence of a histological documentation of ‘invasive carcinoma of the breast’, ‘intraductal carcinoma (ductal carcinoma in situ) of the breast’ or ‘Paget’s disease of the breast’,45 50 51 whereas Fisher et al41 reported that ‘accredited records technicians, blinded to the coding in the original records, reviewed the medical records, selected the supportable diagnoses and procedures and translated them into ICD-9-CM’.

The included studies differed in the geographical area, temporal period, healthcare system, reference standard considered and other factors, and this heterogeneity could explain the variability of the diagnostic accuracy measures. Because of the heterogeneity of the results due to the different settings of each included study, we decided to present them in a descriptive manner rather than aggregate them by means of a meta-analysis.

Prioritising accuracy measures

In assessing the validity of healthcare databases, researchers will need to weigh the relative importance of epidemiological measures and prioritise the accuracy measure that is most important to a particular study. As pointed out by Chuback et al,35 for example, contrary to PPV estimates, sensitivity and specificity do not depend on the disease prevalence but can vary across populations. Privileging sensitivity to specificity is relevant in a scenario where identifying all cases with the characteristic of interest is important rather than only those with severe disease characteristics. PPV is generally preferred when one wants to ensure that only the subjects who truly have the condition of interest are included in the study. In our assessment, 19 studies provided PPV measures, 15 of which also measured sensitivity.10 38 40–44 46–49 53–55 Most of these performed an accuracy assessment with the intent to define the incidence of breast or other cancer diseases. Several authors included different variables in their algorithm, including surgical, chemoradiation or radiation treatment, outpatient care, such as physician’s claims in order to obtain algorithms with a balanced value between PPV and sensitivity. While three studies obtained similar values between sensitivity and PPV,40 43 55 in six studies10 38 42 46 48 54 the initial PPVs were higher than sensitivity and most of these studies had the priority of estimating the incidence of breast cancer disease. Sato et al49 attributed the gain of optimal sensitivity (90%) and PPV (99%) to the use of both inpatient and outpatient claims data. The authors argue that they might have obtained high sensitivity but low PPV if they had used the outpatient database alone. In two Italian validation studies10 38 of regional administrative databases, the combination of hospital diagnosis together with surgical procedures accurately identified the majority of cases in the cancer registry (PPV 90% and 91%, respectively). In other circumstances, the aims of the studies were substantially methodological. Freeman et al,42 who aimed at obtaining the optimal combination of predictors, used a logistic regression model using 1992 data from the linked SEER registries. The authors were able to obtain a high sensitivity (90%) with the use of three kinds of claims data (inpatients, outpatients and physician services), but with a loss of PPV (70%) that was probably due to limitations in distinguishing recurrent and secondary cancers. Cooper et al39 only investigated the sensitivity of diagnostic and procedural coding for case ascertainment of breast and five other cancer diseases. The authors used two sets of analyses: the first set was the inpatient Medicare claims, which include diagnoses and procedures ICD-9 codes; the second set was the part B claims, which include physician and outpatient data. The first set considered the sensitivity of inpatient first position (68.3%) and the increase in sensitivity provided by including additional fields (other diagnosis (76.1%), surgical (79.1%), part B first position (91%), part B other diagnosis (93.1%), part B surgical code (93.6%)). In the second set of analyses, they considered the sensitivity of part B first position (66%) and included the following additional fields: part B other diagnosis (76.9%), part B surgical (80.9%), inpatient first position (90.9%), inpatient other diagnosis (93%) and inpatient surgical (93.6%).

Conversely, the aim of Nattinger et al47 was to maintain a high specificity and they proposed a four-step algorithm to identify women with surgically treated incident breast cancer that was applied in both a validation set and a training set. For their objective, they considered cases treated in the ambulatory surgical setting as well as prevalent cases. The authors were able to obtain high specificity (99.9%) with a decrease in sensitivity from 85% to 80% but with a good PPV performance (range 89%–93%). As recognised by the authors, the algorithm may have little usefulness in determining the incidence of breast cancer, but it may be much more relevant for outcome classification.35

Strengths and limitations

Our strengths include the use of comprehensive electronic databases with reference checks of relevant reviews of articles, the use of STARD criteria to assess the quality of reporting of primary studies, transparency based on prepublication of a protocol (online supplementary file 5), the use of detailed and explicit eligibility criteria and the use of duplicate and independent processes for study selection, data abstraction and data interpretation.

bmjopen-2017-019264supp005.pdf (696.3KB, pdf)

We must acknowledge that our assessment was focused on primary breast cancer and we did not take into account diagnosis of metastases due to breast cancer. A recent study that evaluated the accuracy of ICD-9 codes in identifying metastatic breast and other cancer diseases found that the performance of the metastases codes from Medicare claims data compared with the gold standard of SEER stage was poor and never exceeded 80% for any of the accuracy measures for any stage for any cancer metastatic disease.60 Other studies reported similar low values of accuracy and this may misclassify a significant number of patients and lead to a biased assessment of survival.22 61 62

Second breast cancer recurrences and second primary breast cancers are of interest in the epidemiological and outcome research of breast cancer. In our assessment, we did not consider studies that used algorithms to identify recurrences and second breast cancer events. A recent study assessed several algorithms to identify second breast cancer events following early stage invasive breast cancer and found high accuracy measures.63 In addition, we were not able to consider articles that were not written in English and this may have introduced language bias. In addition, despite the comprehensive nature of our search, a few pertinent articles may have been missed given that some identified articles did not use the term ‘administrative database’ as a subject heading, and the term is not recognised as a MeSH by Medline. Indeed, we were able to identify four primary studies54–57 using the Cited-By’ tools in PubMed, Google Scholar or checking the reference of included studies. Fourth, the knowledge and experience of the ICD-9/ICD-10 coders could have influenced the quality of breast cancer case definition in each study, and consequently the results presented in our review could be biased by this factor. Finally, we emphasise that the applicability of validation studies depends much on the methods used to identify subjects with the condition of interest to validate the algorithm because this may influence the disease prevalence, and the generalisability of the subjects characteristics as well as the diagnostic accuracy measures. Hence, the generalisability of a database is limited to the setting in which the validation has been performed.64 For example, while Medicare covers the elderly41 42 47 55 59 61 and Medicaid covers indigent and other particular group of patients groups,44 57 the US Healthcare, is an independent practice association model, that may represent patient populations of a relatively higher socioeconomic class.50 51 Hence, inference from these validated databases cannot be made to those who despite residing in the same area of the residents registered in the above reported systems but do not benefit from them or to subjects aged 64 years or less as is in most cases of the Medicare system. Conversely, the database in Italy10 38 and France40 54 where the provision of healthcare is universally provided to residents, the applicability of the results from the validated databases is adequate, although it cannot be extended at a national level. Finally, we found a study that validated data from a single institution in Japan and as acknowledged by the authors it is unclear whether the accuracy results can be directly applicable to other hospitals.49

Conclusion

In summary we conclude that, based on the retrieved evidence, administrative databases can be employed to identify primary breast cancer. The best algorithm suggested is ICD-9 or ICD-10 codes located in primary position. Caution should be used when surgical procedures, chemotherapy, radiation therapy or outpatient data and physician claims are added to the algorithm. We believe that our findings will help researchers that would like to validate breast cancer ICD-9 or ICD-10 codes in administrative databases using either cancer registry or medical charts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Kathy Mahan for editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: IA, AM, GG, DG, MF conceived and designed the study; EB, VS, AG, FC, MO, IA and AM were involved in the data acquisition; IA, AM, DS, MF and GG analysed and interpreted the data and IA, EB, MO, GG, DS, VS, AG, FC, MF and AM contributed in the drafting and revising the study and have approved submission of the final version of the article. AM is the guarantor of the review.

Funding: This systematic review protocol was developed within the D.I.V.O. project (Realizzazione di un Database Interregionale Validato per l’Oncologia quale strumento di valutazione di impatto e di appropriatezza delle attività di prevenzione primaria e secondaria in ambito oncologico) supported by funding from the National Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (CCM 2014), Ministry of Health, Italy.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The authors will give full access to our database that gathered data of individual studies included in this review. The request must be done by sending an email to amontedori@regione.umbria.it.

References

- 1. Sullivan R, Peppercorn J, Sikora K, et al. Delivering affordable cancer care in high-income countries. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:933–80. 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70141-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ginsburg O, Bray F, Coleman MP, et al. The global burden of women’s cancers: a grand challenge in global health. Lancet 2017;389:847–60. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31392-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jemal A, Center MM, DeSantis C, et al. Global patterns of cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010;19:1893–907. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen HF, Liu MD, Chen P, et al. Risks of Breast and Endometrial Cancer in Women with Diabetes: A Population-Based Cohort Study. PLoS One 2013;8:e67420 10.1371/journal.pone.0067420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Escribà JM, Pareja L, Esteban L, et al. Trends in the surgical procedures of women with incident breast cancer in Catalonia, Spain, over a 7-year period (2005-2011). BMC Res Notes 2014;7:587 10.1186/1756-0500-7-587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Montero AJ, Eapen S, Gorin B, et al. The economic burden of metastatic breast cancer: a U.S. managed care perspective. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012;134:815–22. 10.1007/s10549-012-2097-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Earle CC, Venditti LN, Neumann PJ, et al. Who gets chemotherapy for metastatic lung cancer? Chest 2000;117:1239–46. 10.1378/chest.117.5.1239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Song X, Zhao Z, Barber B, et al. Treatment patterns and metastasectomy among mCRC patients receiving chemotherapy and biologics. Curr Med Res Opin 2011;27:123–30. 10.1185/03007995.2010.536912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vachon B, Désorcy B, Gaboury I, et al. Combining administrative data feedback, reflection and action planning to engage primary care professionals in quality improvement: qualitative assessment of short term program outcomes. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:391 10.1186/s12913-015-1056-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yuen E, Louis D, Cisbani L, et al. Using administrative data to identify and stage breast cancer cases: implications for assessing quality of care. Tumori 2011;97:428–35. 10.1177/030089161109700403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Whyte JL, Engel-Nitz NM, Teitelbaum A, et al. An Evaluation of Algorithms for Identifying Metastatic Breast, Lung, or Colorectal Cancer in Administrative Claims Data. Med Care 2015;53:e49–e57. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318289c3fb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bremner KE, Krahn MD, Warren JL, et al. An international comparison of costs of end-of-life care for advanced lung cancer patients using health administrative data. Palliat Med 2015;29:918–28. 10.1177/0269216315596505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mittmann N, Liu N, Porter J, et al. Utilization and costs of home care for patients with colorectal cancer: a population-based study. CMAJ Open 2014;2:E11–17. 10.9778/cmajo.20130026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schneeweiss S, Avorn J. A review of uses of health care utilization databases for epidemiologic research on therapeutics. J Clin Epidemiol 2005;58:323–37. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schulman KL, Berenson K, Tina Shih YC, et al. A checklist for ascertaining study cohorts in oncology health services research using secondary data: report of the ISPOR oncology good outcomes research practices working group. Value Health 2013;16:655–69. 10.1016/j.jval.2013.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sarrazin MS, Rosenthal GE. Finding pure and simple truths with administrative data. JAMA 2012;307:1433–5. 10.1001/jama.2012.404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. West SL, Strom BL, Poole C. Validity of Pharmacoepidemiologic Drug and Diagnosis Data, in Pharmacoepidemiology: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2007:709–65. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cox E, Martin BC, Van Staa T, et al. Good research practices for comparative effectiveness research: approaches to mitigate bias and confounding in the design of nonrandomized studies of treatment effects using secondary data sources: the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research Good Research Practices for Retrospective Database Analysis Task Force Report--Part II. Value Health 2009;12:1053–61. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00601.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Senkus E, Kyriakides S, Ohno S, et al. ESMO Guidelines Committee. Primary breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2015;26(suppl 5):v8–30. 10.1093/annonc/mdv298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weycker D, Edelsberg J, Kartashov A, et al. Risk and healthcare costs of chemotherapy-induced neutropenic complications in women with metastatic breast cancer. Chemotherapy 2012;58:8–18. 10.1159/000335604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vera-Llonch M, Weycker D, Glass A, et al. Healthcare costs in patients with metastatic lung cancer receiving chemotherapy. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:305 10.1186/1472-6963-11-305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nordstrom BL, Whyte JL, Stolar M, et al. Identification of metastatic cancer in claims data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2012;21(Suppl 2):21–8. 10.1002/pds.3247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Abraha I, Serraino D, Giovannini G, et al. Validity of ICD-9-CM codes for breast, lung and colorectal cancers in three Italian administrative healthcare databases: a diagnostic accuracy study protocol. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010547 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Montedori A, Bidoli E, Serraino D, et al. Accuracy of lung cancer ICD-9-CM codes in Umbria, Napoli 3 Sud and Friuli Venezia Giulia administrative healthcare databases: a diagnostic accuracy study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e020628 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Orso M, Serraino D, Abraha I, et al. Validating malignant melanoma ICD-9-CM codes in Umbria, ASL Napoli 3 Sud and Friuli Venezia Giulia administrative healthcare databases: a diagnostic accuracy study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e020631 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Abraha I, Giovannini G, Serraino D, et al. Validity of breast, lung and colorectal cancer diagnoses in administrative databases: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010409 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Montedori A, Abraha I, Chiatti C, et al. Validity of peptic ulcer disease and upper gastrointestinal bleeding diagnoses in administrative databases: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011776 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rimland JM, Abraha I, Luchetta ML, et al. Validation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) diagnoses in healthcare databases: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011777 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cozzolino F, Abraha I, Orso M, et al. Protocol for validating cardiovascular and cerebrovascular ICD-9-CM codes in healthcare administrative databases: the Umbria Data Value Project. BMJ Open 2017;7:e013785 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Benchimol EI, Manuel DG, To T, et al. Development and use of reporting guidelines for assessing the quality of validation studies of health administrative data. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:821–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Carnahan RM, Moores KG. Mini-Sentinel’s systematic reviews of validated methods for identifying health outcomes using administrative and claims data: methods and lessons learned. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2012;21:82–9. 10.1002/pds.2321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McPheeters ML, Sathe NA, Jerome RN, et al. Methods for systematic reviews of administrative database studies capturing health outcomes of interest. Vaccine 2013;31(Suppl 10):K2–6. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.06.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700 10.1136/bmj.b2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015;349:g7647 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chubak J, Pocobelli G, Weiss NS. Tradeoffs between accuracy measures for electronic health care data algorithms. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:343–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dean BB, Lam J, Natoli JL, et al. Review: use of electronic medical records for health outcomes research: a literature review. Med Care Res Rev 2009;66:611–38. 10.1177/1077558709332440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, et al. Towards complete and accurate reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy: The STARD Initiative. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:40–4. 10.7326/0003-4819-138-1-200301070-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Baldi I, Vicari P, Di Cuonzo D, et al. A high positive predictive value algorithm using hospital administrative data identified incident cancer cases. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:373–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cooper GS, Yuan Z, Stange KC, et al. The sensitivity of Medicare claims data for case ascertainment of six common cancers. Med Care 1999;37:436–44. 10.1097/00005650-199905000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Couris CM, Polazzi S, Olive F, et al. Breast cancer incidence using administrative data: correction with sensitivity and specificity. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:660–6. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fisher ES, Whaley FS, Krushat WM, et al. The accuracy of Medicare’s hospital claims data: progress has been made, but problems remain. Am J Public Health 1992;82:243–8. 10.2105/AJPH.82.2.243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Freeman JL, Zhang D, Freeman DH, et al. An approach to identifying incident breast cancer cases using Medicare claims data. J Clin Epidemiol 2000;53:605–14. 10.1016/S0895-4356(99)00173-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kemp A, Preen DB, Saunders C, et al. Ascertaining invasive breast cancer cases; the validity of administrative and self-reported data sources in Australia. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:17 10.1186/1471-2288-13-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Koroukian SM, Cooper GS, Rimm AA. Ability of Medicaid claims data to identify incident cases of breast cancer in the Ohio Medicaid population. Health Serv Res 2003;38:947–60. 10.1111/1475-6773.00155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Leung KM, Hasan AG, Rees KS, et al. Patients with newly diagnosed carcinoma of the breast: validation of a claim-based identification algorithm. J Clin Epidemiol 1999;52:57–64. 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00143-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. McClish DK, Penberthy L, Whittemore M, et al. Ability of Medicare claims data and cancer registries to identify cancer cases and treatment. Am J Epidemiol 1997;145:227–33. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nattinger AB, Laud PW, Bajorunaite R, et al. An algorithm for the use of Medicare claims data to identify women with incident breast cancer. Health Serv Res 2004;39(6 Pt 1):1733–50. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00315.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Penberthy L, et al. The added value of claims for cancer surveillance: results of varying case definitions. Med Care 2005;43:705–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sato I, Yagata H, Ohashi Y. The accuracy of Japanese claims data in identifying breast cancer cases. Biol Pharm Bull 2015;38:53–7. 10.1248/bpb.b14-00543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Solin LJ, Legorreta A, Schultz DJ, et al. Analysis of a claims database for the identification of patients with carcinoma of the breast. J Med Syst 1994;18:23–32. 10.1007/BF00999321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Solin LJ, MacPherson S, Schultz DJ, et al. Evaluation of an algorithm to identify women with carcinoma of the breast. J Med Syst 1997;21:189–99. 10.1023/A:1022864307036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Warren JL, Feuer E, Potosky AL, et al. Use of Medicare hospital and physician data to assess breast cancer incidence. Med Care 1999;37:445–56. 10.1097/00005650-199905000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Warren JL, Riley GF, McBean AM, et al. Use of Medicare data to identify incident breast cancer cases. Health Care Financ Rev 1996;18:237–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ganry O, Taleb A, Peng J, et al. Evaluation of an algorithm to identify incident breast cancer cases using DRGs data. Eur J Cancer Prev 2003;12:295–9. 10.1097/00008469-200308000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. McBean AM, Warren JL, Babish JD. Measuring the incidence of cancer in elderly Americans using Medicare claims data. Cancer 1994;73:2417–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Setoguchi S, Solomon DH, Glynn RJ, et al. Agreement of diagnosis and its date for hematologic malignancies and solid tumors between medicare claims and cancer registry data. Cancer Causes Control 2007;18:561–9. 10.1007/s10552-007-0131-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wang PS, Walker AM, Tsuang MT, et al. Finding incident breast cancer cases through US claims data and a state cancer registry. Cancer Causes Control 2001;12:257–65. 10.1023/A:1011204704153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ramsey SD, Scoggins JF, Blough DK, et al. Sensitivity of administrative claims to identify incident cases of lung cancer: a comparison of 3 health plans. J Manag Care Pharm 2009;15:659–68. 10.18553/jmcp.2009.15.8.659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Penberthy L, McClish D, Manning C, et al. The added value of claims for cancer surveillance: results of varying case definitions. Med Care 2005;43:705–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Chawla N, Yabroff KR, Mariotto A, et al. Limited validity of diagnosis codes in Medicare claims for identifying cancer metastases and inferring stage. Ann Epidemiol 2014;24:666–72. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.06.099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Cooper GS, Yuan Z, Stange KC, et al. The utility of Medicare claims data for measuring cancer stage. Med Care 1999;37:706–11. 10.1097/00005650-199907000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Thomas SK, Brooks SE, Mullins CD, et al. Use of ICD-9 coding as a proxy for stage of disease in lung cancer. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2002;11:709–13. 10.1002/pds.759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Chubak J, Yu O, Pocobelli G, et al. Administrative data algorithms to identify second breast cancer events following early-stage invasive breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2012;104:931–40. 10.1093/jnci/djs233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Abraha I, Orso M, Grilli P, et al. The Current State of Validation of Administrative Healthcare Databases in Italy: A Systematic Review. Int J Stat Med Res 2014;3:309–20. 10.6000/1929-6029.2014.03.03.10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-019264supp001.pdf (93.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-019264supp002.pdf (93.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-019264supp003.pdf (92.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-019264supp004.pdf (24.5KB, pdf)