Abstract

Objectives

Non-persistence may be a significant barrier to the use of metformin. Our objective was to assess reasons for metformin non-persistence, and whether initial metformin dosing or use of extended release (ER) formulations affect persistence to metformin therapy.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

Electronic health record data from a network of urban academic practices.

Participants

The cohort was restricted to individuals receiving a metformin prescription between 2009/1/1 and 2015/9/31, under care for at least 6 months before the first prescription of metformin. The cohort was further restricted to patients with no evidence of any antihyperglycaemic agent use prior to the index date, an haemoglobin A1c measured within 1 month prior to or 1 week after the index date, at least 6 months of follow-up, and with the initial metformin prescription originating in either a general medicine or endocrinology clinic.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was early non-persistence, as defined by the absence of further prescriptions for metformin after the first 90 days of follow-up.

Results

The final cohort consisted of 1259 eligible individuals. The overall rate of early non-persistence was 20.3%. Initial use of ER and low starting dose metformin were associated with significantly lower rates of reported side effects and non-persistence, but after multivariable analysis, only use of low starting doses was independently associated with improved persistence (adjusted OR 0.54, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.76, for comparison of 500 mg daily dose or less to all higher doses).

Conclusions

These data support the routine prescribing of low starting doses of metformin as a tool to improve persistence. In this study setting, many providers routinely used ER metformin as an initial treatment; while this practice may have benefits, it deserves more rigorous study to assess whether increased costs are justified.

Keywords: adverse events, general diabetes

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Sample is composed of a cohort from a large, diverse academic medical centre.

Traditional claims-based datasets do not offer access to electronic health record free-text.

Electronic prescriptions were used as a proxy for medication use; out-of-network dispenses would not be recorded.

Efforts to infer causality may be limited by unmeasured confounding.

Background

Metformin is the first-line drug for type 2 diabetes (T2DM), and evidence also supports its off-label use for obesity and prediabetes.1 2 Yet, even among patients with T2DM, only half take metformin.3 4 Non-use of metformin in patients with T2DM has many possible causes: providers may not offer the medication, patients may decline to start once it is recommended (primary non-adherence) or patients may start metformin but discontinue it later (non-persistence).5 6 For patients diagnosed with T2DM, both overall utilisation and long-term metformin persistence are approximately 50%,6 7 consistent with most patients being offered the medication but roughly half of them not taking it long-term.

Given metformin’s low cost, excellent safety profile and effectiveness, such high rates of non-persistence warrant explanation. They may reflect many patients being undertreated, or requiring more costly and less safe second-line antihyperglycaemic agents (AHAs). But, the reasons and the implications of low rates of metformin persistence are not clearly understood. In some cases, a failure to continue to take metformin might reflect lack of need for the drug, for example if T2DM is well controlled with diet alone. In other cases, a clear clinical need may be present but patients may lack motivation to adhere to chronic medication, be unable to afford the cost, or have concerns about drug safety or stigma.8

A third potential factor in metformin non-persistence is intolerance. Metformin is widely described as poorly tolerated due to gastrointestinal side effects, and providers are advised to use low starting doses and consider extended release (ER) formulations to curb these side effects.9 10 It has been proposed that patients with less functional variants in the organic cation transport 1 (OCT-1) gene may also have worsened side effects from metformin due to accumulation in the gut,11 and that patients with Helicobacter pylori infection or other conditions predisposing them to gastrointestinal distress may be less likely to adhere to metformin.12

Because metformin is a cornerstone of diabetes management, understanding the reasons for metformin non-persistence is an important step for identifying effective interventions to improve metformin persistence and diabetes care. We conducted a study using the electronic health record (EHR) of a network of academic outpatient practices combined with chart review to assess the prevalence, risk-factors and causes of metformin non-persistence. In addition to these descriptive aims, we hypothesised that initial use of low starting doses and ER formulations would be associated with improved persistence.

Methods

Cohort definition

A retrospective cohort study was conducted using EHR at the Weill Cornell Medicine outpatient practices. The cohort was restricted to individuals receiving a metformin prescription between 1 January 2009 and 2015/9/30 who were under care for at least 6 months before the first prescription of metformin (the ‘index date’). The cohort was further restricted to patients with no evidence of any AHA use prior to the index date, an haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) measured within 1 month prior to or 1 week after the index date, at least 6 months of follow-up, and with the initial metformin prescription originating in either a general medicine or endocrinology clinic. Follow-up was defined as a period of time with an average of at least one clinic encounter every 6 months, ending at the last recorded clinic encounter.

Initial chart reviews suggested that a significant number of individuals included in the original study protocol were not true new users of metformin. Since it was essential to accurately identify and classify new metformin use, free text in the EHR was used to confirm that metformin was truly a new medication. Two investigators reviewed an initial sample of 160 patient charts to develop a simple regular expressions classifier to confirm new use of metformin. The script (written in the R statistical programing language, V.3.2.2) needed to implement the classifier is available on request. Briefly, the regular expression was applied only to text appearing within 100 characters of the word ‘metformin’ or one of its synonyms, and searched this text using the regular expression:

“start.*metformin|begin.*metformin|try.*metformin|consider.*metformin|prescrib.*metformin|initiate.*metformin”, using the ‘gsub’ function in R.

The classifier was evaluated against manual review (by two independent reviewers) in a validation set of an additional 200 patients. The sensitivity and recall rate of this classifier was then evaluated against a separate sample of 200 patient charts, using blinded chart review by two reviewers as the gold standard.

Characterisation of initial prescription

Metformin prescriptions were characterised by formulation and daily dose. Patients were characterised using baseline demographic information, laboratory, vital signs, ICD-9 codes and other prescriptions. If the HbA1c was <6.5%, charts were manually reviewed by two reviewers to identify the indication, classified as ‘diabetes’, ‘obesity’, ‘prediabetes’, ‘obesity and prediabetes’, ‘polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS)’, ‘other’ and ‘unknown’. The indication for metformin was assumed to be for treatment of diabetes if the baseline HbA1c was ≥6.5%.

Each prescription was linked to the prescribing provider, and provider preference (in terms of initial dose and formulation) was calculated by, for each prescription, examining all earlier initial metformin prescriptions for other patients from that same provider. Providers were defined as ‘preferring low dose’ if over half of their earlier initial metformin prescriptions were for 500 mg daily doses or less, and defined as ‘preferring ER’ if more than half of their earlier initial metformin prescriptions were for ER, as opposed to immediate release (IR).

Outcomes

Early non-persistence (the primary outcome) was defined as absence of any further metformin prescriptions after the first 90 days of follow-up, in patients with at least 18 months of follow-up after the index date. Therefore, patients who had only a single prescription for metformin were classified as non-persistent, as were those patients who received multiple prescriptions within the first 90 days but none after 90 days. Charts were manually reviewed by two independent reviewers, blinded to the study outcome, to determine the reason for early non-persistence and presence or absence of side effects. Additional secondary outcomes were daily metformin dose, formulation and HbA1c results during follow-up.

Analysis

Associations between baseline characteristics and the outcomes were assessed using logistic models with the following a priori variables forced in: baseline HbA1c, age, sex, use of statins, use of antihypertensives, use of OCT-1 inhibiting drugs (citalopram, verapamil, diltiazem, doxazosin, spironolactone, clopidogrel, tramadol, codeine or quinine), calendar year, type of prescriber (general internist vs endocrinologist) and comorbidities derived from ICD-9 codes (diabetes, pulmonary disease, heart failure, hypothyroidism, renal disease, liver disease, obesity and depression). The initial dose of metformin used as well as the formulation was also included in the model.

Patient and public involvement

Development of the research question and outcome measures was informed by literature review and the investigators’ subject matter knowledge. Patients were not directly involved in the design of this study.

Results

Cohort definition

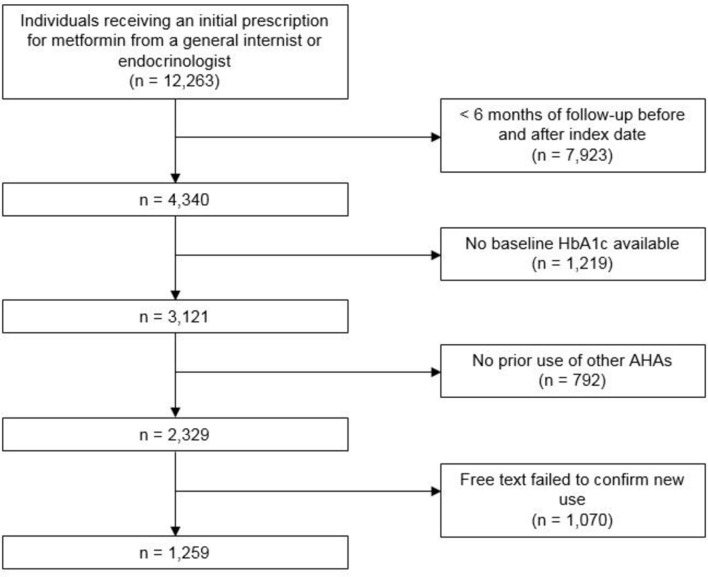

A total of 12 263 individuals received an initial prescription for metformin from either a general internist or an endocrinologist during the study period. After requirements for 6 months of follow-up before and after the index date, the cohort was reduced to 4340. A total of 3121 had baseline HbA1c available and 2329 had no prior use of other AHAs (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patient attrition. Initial cohort size and patient attrition. AHA, antihyperglycaemic agent; HbA1c, haemoglobin A1c.

Review of a subset of 160 charts initially classified as new metformin users confirmed that 66.3% of patients were new users of metformin, but that 21.3% of patients in the cohort were not new initiators while 12.5% could not be determined either way. In order to reduce the rate of misclassified patients, a regular expression classifier was developed through manual review of the 160 charts to identify new initiators.

Of 111 patients in the 200 patient validation set classified as new initiators of metformin based on the regular expression, 106 (94.4%) were new metformin initiators on manual chart review. Conversely, of the 89 patients who were not classified as new initiators based on the regular expression, only 6 (6.7%) could be confirmed as new metformin users on chart review.

Use of the free-text classifier to restrict the cohort to individuals with free-text evidence of metformin use identified a final cohort of 1259 patients.

Baseline characteristics and initial prescribing patterns

Of the final cohort, 30% of patients were male, with a median age of 58 years. Median baseline HbA1c was 6.6% (IQR 6.0%–7.2%). Thirty nine per cent of patients were on statins, and 38% were on antihypertensives. A minority of patients, 44%, had recorded body mass index, median 32.5 kg/m2 (IQR 27.8 to 37.8) (table 1). When HbA1c was stratified into non-diabetic (HbA1c<6.5%) and diabetic (HbA1c≥6.5%) ranges, the demographic composition was different across strata, with more of the non-diabetic patients being women (table 1). Stratification on other variables, including dose and initial formulation, showed imbalance on baseline characteristics including baseline HbA1c (online supplementary table S1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of baseline cohort

| Baseline HbA1c <6.5 | Baseline HbA1c ≥6.5 | |||

| Mean or % | SD | Mean or % | SD | |

| N | 564 | 695 | ||

| Men | 0.18 | 0.39 | 0.42 | 0.49 |

| Age | 52.05 | 14.37 | 60.87 | 13.02 |

| White | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.26 | 0.44 |

| Black | 0.21 | 0.41 | 0.28 | 0.45 |

| Asian | 0.07 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.24 |

| Other | 0.39 | 0.49 | 0.39 | 0.49 |

| A1c (%) | 5.92 | 0.37 | 7.71 | 1.59 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.81 | 0.18 | 0.88 | 0.23 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 34.09 | 8.22 | 32.63 | 7.28 |

| Statin | 0.28 | 0.45 | 0.39 | 0.49 |

| Antihypertensive | 0.31 | 0.46 | 0.53 | 0.5 |

| Diabetes diagnosis | 0.34 | 0.47 | 0.8 | 0.4 |

| Diabetes complications | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.38 |

| Heart failure | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.23 |

| Hypothyroidism | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.16 | 0.36 |

| Renal disease | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.26 |

| Liver disease | 0.06 | 0.23 | 0.12 | 0.32 |

| Obesity | 0.6 | 0.49 | 0.46 | 0.5 |

| Depression | 0.19 | 0.4 | 0.19 | 0.39 |

| 500 mg starting dose | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.46 | 0.5 |

| 1000 mg dose | 0.46 | 0.5 | 0.48 | 0.5 |

| Other starting dose | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.24 |

| ER formulation | 0.57 | 0.49 | 0.47 | 0.5 |

| Endocrinology clinic | 0.37 | 0.48 | 0.16 | 0.37 |

BMI, body mass index; ER, extended release; HbA1c, haemoglobin A1c.

bmjopen-2018-021505supp001.pdf (182.8KB, pdf)

The percentage of patients with baseline HbA1c <6.5% receiving metformin increased from 33% in 2010 to 54% in 2015 (p<0.01). For patients with baseline HbA1c<6.5%, the most common indications based on manual chart review were prediabetes (36%), diabetes (9.8%), obesity (9.2%), the combination of prediabetes and obesity (7.0%) and PCOS (8.2%). Indications could not be identified for 26% of these patients.

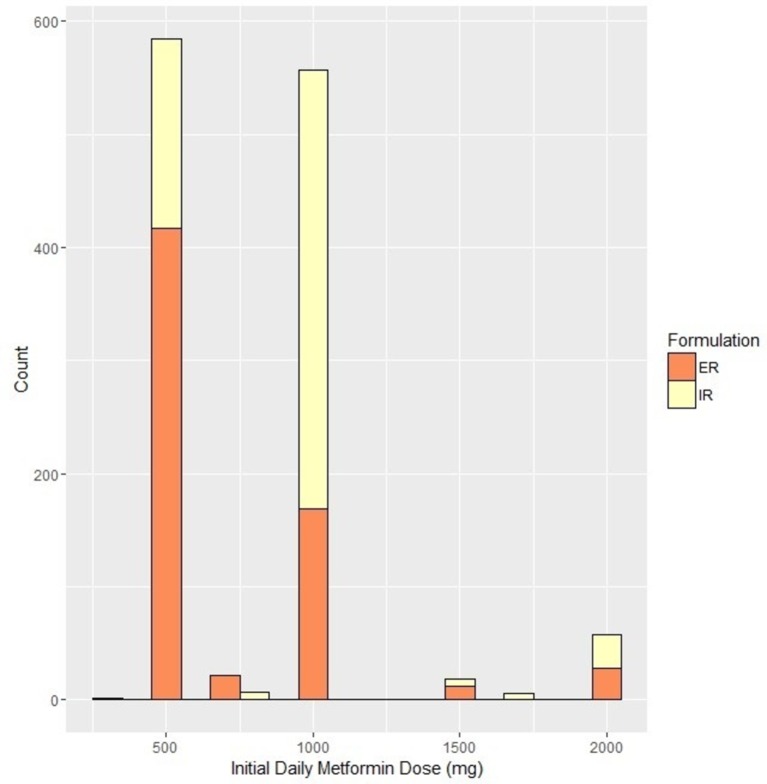

Almost half, 48%, of patients were started on 500 mg of metformin per day. Forty six per cent started at doses between 500 mg and 1000 mg per day and 6.5% started at doses>1000 mg per day. Fifty two per cent were started on ER formulations. Use of low initial metformin dose and of ER formulations were correlated. Among patients who started on ER, 67.6% were prescribed the minimum starting dose of 500 mg daily. In contrast, among patients who started on IR only 27.7% received a starting dose of 500 mg daily (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Baseline doses and formulation. Orange denotes immediate release (IR) formulation, Yellow denotes extended release (ER) formulation.

One hundred and fifty-eight distinct providers had a history of more than one initial metformin prescription, making it possible to assess their prescribing patterns. Of these, 28% preferentially (over half the time) wrote new prescriptions for metformin that were 500 mg daily (‘low dose’) and ER. Conversely, 34% of providers preferentially wrote new prescriptions for metformin that were IR and over 500 mg daily. Eighteen percent of providers preferentially wrote metformin prescriptions that were low dose and IR, while 20% wrote metformin prescriptions that were over 500 mg daily and were ER.

After adjustment for patient characteristics (age, sex, baseline HbA1c and year of prescribing) patients who were seen by a provider who had prescribed ER metformin more than half the time for prior patients had an OR of 7.2 (95% CI 5.4 to 9.7) for receiving ER metformin. Patients who were seen by a provider who prescribed a starting dose of 500 mg more than half the time for other patients had an OR of 3.42 for receiving a starting dose of 500 mg themselves (95% CI 2.6 to 4.6).

Primary outcome

Early non-persistence occurred in 20.3% of patients, including 28.6% of those with baseline HbA1c <6.5% and 14.1% of those with baseline HbA1c ≥6.5%. Multivariable analysis confirmed an association between higher baseline HbA1c and lower rates of non-persistence (OR 0.70 per percentage point of HbA1c, 95% CI 0.55 to 0.85). Use of ER metformin was also associated with lower rates of non-persistence (OR 0.62, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.88), as was use of lower doses of metformin (OR 0.54, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.76) for comparison of 500 mg daily dose or less to all higher doses. When both characteristics were included in the model, the association between ER and non-persistence was no longer significant, but higher initial doses of metformin were associated with higher rates of non-persistence (table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariable model for persistence

| Point estimate | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | P values | |

| ER | 0.8 | 0.55 | 1.18 | 0.27 |

| 500 mg or less | ref | |||

| 500–1500 mg | 1.66 | 1.13 | 2.44 | 0.01 |

| >1500 mg | 2.24 | 1.02 | 4.73 | 0.04 |

| HbA1c increase 1% | 0.73 | 0.59 | 0.88 | <0.01 |

| Age 50–65 | 1.02 | 0.66 | 1.57 | 0.94 |

| Age≥65 | 1.06 | 0.65 | 1.72 | 0.82 |

| Male | 0.74 | 0.49 | 1.13 | 0.17 |

| White | ref | |||

| Black | 0.53 | 0.32 | 0.86 | 0.01 |

| Asian | 0.41 | 0.17 | 0.9 | 0.04 |

| Other | 0.78 | 0.53 | 1.16 | 0.22 |

| Statin | 0.62 | 0.41 | 0.93 | 0.02 |

| Antihypertensive | 0.96 | 0.64 | 1.42 | 0.83 |

| Endocrine clinic | 0.62 | 0.4 | 0.96 | 0.03 |

| OCT-1 inhibitor use | 0.89 | 0.52 | 1.48 | 0.67 |

| Diabetes diagnosis | 0.38 | 0.19 | 0.75 | 0.01 |

| Diabetes complications | 0.52 | 0.33 | 0.79 | <0.01 |

| Heart failure | 1.43 | 0.6 | 3.13 | 0.39 |

| Hypothyroidism | 0.96 | 0.63 | 1.44 | 0.84 |

| Renal disease | 1.59 | 0.76 | 3.15 | 0.20 |

| Liver disease | 0.54 | 0.23 | 1.12 | 0.12 |

| Obesity | 0.58 | 0.41 | 0.83 | <0.01 |

| Depression | 0.7 | 0.44 | 1.11 | 0.14 |

ER, extended release; HbA1c, haemoglobin A1c; OCT-1, organic cation transport 1.

Secondary outcomes

Side effects attributed to metformin were documented in 26% of patients (23.5% of patients with baseline HbA1c <6.5% and 27.7% of patients with baseline HbA1c ≥6.5%). The majority were gastrointestinal (61.7%, typically nausea or diarrhoea); 16.1% were not gastrointestinal related (most commonly headache and fatigue) and 17.4% were not specified. After multivariable adjustment, side effects were less common in men and in those initially prescribed ER metformin, and were more common in patients receiving starting dose of metformin >1500 mg per day (table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable model for side effects

| Point estimate | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | P values | |

| ER | 0.61 | 0.42 | 0.87 | 0.01 |

| 500 mg | ref | |||

| 500–1500 mg | 0.97 | 0.68 | 1.39 | 0.88 |

| >1500 mg | 2.16 | 1.07 | 4.32 | 0.03 |

| HbA1c increase 1% | 1 | 0.88 | 1.14 | 0.96 |

| Age 50–65 | 0.92 | 0.6 | 1.39 | 0.68 |

| Age ≥65 | 1.09 | 0.69 | 1.72 | 0.71 |

| Male | 0.61 | 0.41 | 0.9 | 0.01 |

| White | ref | 0.68 | ||

| Black | 1.1 | 0.7 | 1.71 | 0.93 |

| Asian | 0.97 | 0.43 | 2.01 | 0.88 |

| Other | 0.97 | 0.65 | 1.45 | 0.34 |

| Statin | 0.84 | 0.58 | 1.21 | 0.33 |

| Antihypertensive | 0.84 | 0.58 | 1.2 | 0.88 |

| Endocrine clinic | 0.94 | 0.62 | 1.42 | 0.76 |

| OCT-1 inhibitor use | 1.13 | 0.72 | 1.75 | 0.58 |

| Diabetes diagnosis | 1.39 | 0.77 | 2.51 | 0.28 |

| Diabetes complications | 1.08 | 0.7 | 1.67 | 0.73 |

| Heart failure | 1.29 | 0.62 | 2.57 | 0.48 |

| Hypothyroidism | 0.81 | 0.54 | 1.21 | 0.31 |

| Renal disease | 1.06 | 0.54 | 2 | 0.87 |

| Liver disease | 0.89 | 0.49 | 1.54 | 0.68 |

| Obesity | 1.28 | 0.91 | 1.79 | 0.15 |

| Depression | 1.76 | 1.2 | 2.57 | <0.01 |

ER, extended release; HbA1c, haemoglobin A1c; OCT-1, organic cation transport 1.

Of all non-persistent patients, manual chart review showed that 30% had side effects documented as the reason for discontinuation, 8.9% never started taking metformin despite the prescription (primary non-persistence), 7.2% were felt to no longer need metformin due to clinical improvement and 3.3% had other reasons documented. But, most charts (50.6%) did not include a reason for discontinuation.

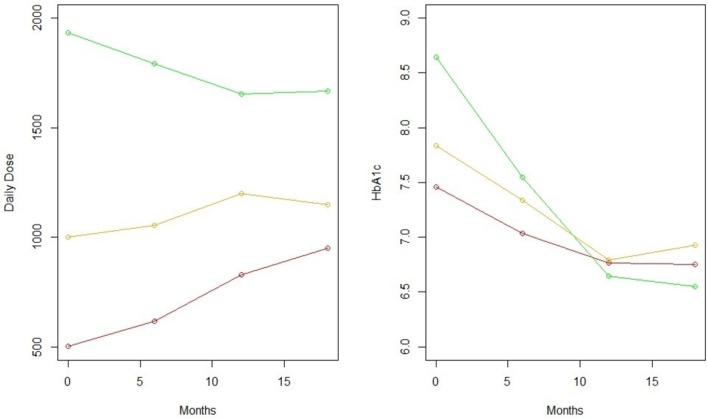

During follow-up, metformin doses were typically increased, and in patients with baseline HbA1c ≥6.5%, HbA1c at 1 year of follow-up was comparable regardless of starting dose (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Dose and haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) curves over time. Green=starting dose >1500 mg, yellow=starting dose 500–1500 mg, red=starting dose 500 mg or less.

At the end of follow-up, in patients who continued to receive metformin prescriptions after 1 year, the prescribed mean daily metformin dose was 1022 mg among patients with baseline HbA1c <6.5% and 1199 mg in patients with baseline HbA1c ≥6.5%, with 61.1% of persistent patients remaining at daily metformin doses of 1000 mg or less. 21.2% patients who started on IR switched to ER before the end of follow-up, and documentation of side effects was associated with switching to ER (OR 3.5, 95% CI 2.2 to 5.6).

An exploratory analysis examined the association between provider preference in initial prescription and the primary outcome of non-persistence. Rates of non-persistence were 22% for providers who typically used IR metformin, and 20% for those who used ER metformin. For providers who preferred low versus high starting doses, rates of non-persistence were 21% and 20%, respectively.

Conclusions

Clinical findings

This study shows wide variation in metformin prescribing practices, supports current recommendations for maximising its tolerability, and identifies opportunities to further optimise prescribing practices for this widely used drug.13 Use of low starting doses of metformin is associated with less early non-persistence, while use of ER formulations is associated with a lower rate of side effects but has no significant independent association with persistence. While it is reasonable to advocate low starting doses of metformin as a standard treatment strategy, the impact of a strategy of initial ER formulation needs further study.

Dose and formulation selection for metformin were diverse, with about half of patients starting at 500 mg daily dose versus 1000 mg daily, and about half of patients starting with ER versus IR formulations. These two initial decisions appeared to be based primarily on provider prior use habits rather than on patient characteristics. Rates of early non-persistence were approximately 20%, consistent with other studies.14 The strongest independent predictors of non-persistence were a low baseline HbA1c and high starting doses.

Low initial doses of metformin were associated with lower rates of initial non-persistence, consistent with existing research, particularly an older observational study based on insurance claims data which found that higher doses of metformin are associated with lower persistence.15 It is usually assumed that lower doses are beneficial due to lower rates of side effects, and indeed previous observational study showed that higher doses of metformin are associated with more side effects.16 But, our results only show a relationship between increased side effects and dose at the highest initial doses. Interestingly, this is consistent with a meta-analysis that did not show a dose–response relationship between metformin and its side effects.17 One possibility is that patients prefer low initial doses and only taking a single pill or tablet at a time, even if the rate of side effects is not materially affected by the low dose.

ER metformin was not associated independently with higher rates of adherence, but was associated with lower rates of side effects. These results cohere with existing evidence. Multiple randomised studies have shown that ER formulations do reduce rates of side effects,18 but only two observational studies showed that ER formulations have an impact on adherence.19 20 One analysis was limited by small sample size and did not adjust for major potential confounders, including metformin dose,19 while the other study found an improvement in adherence among metformin ER patients, but did not report statistical significance. One possible explanation for our study finding no apparent benefit from initial use of ER metformin is that some patients who begin IR may switch to ER when side effects manifest. We may have also missed a modest true benefit due to limitations in sample size.

ER formulations are slightly more expensive than IR, and guidelines that take cost into account recommend beginning with IR metformin and only switching to ER if side-effects occur (https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28/chapter/1-recommendations). Nonetheless, some providers use ER formulations initially, on the assumption that it will result in better tolerability and hence better adherence. One cost-effectiveness analysis found that modest cost savings and improved clinical outcomes would be associated with initial choice of ER metformin over IR.21

Overall, these findings suggest that whenever clinically appropriate, providers should consider starting metformin at the lowest possible dose. Systematic efforts to promote initial use of ER formulations of metformin seem premature due to limited evidence for benefit, possible unintended effects including increased cost from the ER formulation, and the option to switch to ER if needed later in a treatment course. But, since even small increases in metformin adherence and persistence might have significant benefits on the level of the healthcare system, this question deserves further study.

This study yielded two notable incidental findings. The first was a high proportion of metformin use off label. Epidemiological studies should consider that metformin use alone may not reliably imply a diagnosis of diabetes. Second, while metformin doses are titrated up over time, most patients remain on doses of 1000 mg daily or less. Pivotal studies of metformin have typically used higher doses of the drug. In the Diabetes Prevention Program study, 84% of the metformin group took a daily dose of 1700 mg.22 In the U K Prospective Diabetes Study, the median daily dose of metformin was 2550 mg, with an IQR of 1700–2550 mg/day.23

It is not clear why less than half of patients in the present study had been titrated to a daily dose greater than 1000 mg after a year. One possibility is that providers increased metformin only as needed to maintain goal HbA1c, instead of trying to replicate the regimen used in studies that showed clinical benefits. Another is that doses may be limited by intolerance. In either case, the relatively low metformin doses used in chronic care represent a potential gap in translation from clinical trial results to practice.

Limitations

This study has limitations. Electronic prescriptions were used as a proxy for medication use. If a patient ultimately received metformin prescriptions from another provider network, this would lead to misclassification of patients as non-persistent. But, the most widely used alternative measures of persistence—claims data—would not have been clearly superior, as claims data will not identify patients who receive a prescription but never fill it or who pay out-of-pocket without generating a claim. Furthermore, claims-based sources typically do not offer access to free text. Finally, efforts to infer causality in this study are limited by the potential for unmeasured confounding. Baseline characteristics including HbA1c differed between dose and formulation groups (online supplementary table S1), emphasising the need for future studies to adjust for confounding as thoroughly as possible. One particularly important possibility is that providers who tend to use low starting doses and ER formulations may have other practice patterns, such as more careful communication with patients, that might improve persistence.

Summary

This study shows high variability, largely driven by provider preference, in choice of initial metformin dosing and formulation. It suggests that a strategy of starting metformin at minimal dose improved persistence, while also showing that only half of the providers routinely use that dosing strategy. The utility of routinely using ER metformin as an initial treatment remains uncertain.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JHF: responsible for entire protocol and manuscript. SJK: data analysis and manuscript preparation. DS: protocol design and manuscript preparation. AIM: data analysis and manuscript preparation. All authors have contributed sufficiently to the production of the manuscript to satisfy the ICMJE criteria for authorship. All authors have agreed on the collective joint-authorship, and author order.

Funding: This project was supported by AHRQ training grant K08HS023898-01.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Weill Cornell Medical College IRB.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Technical appendix, statistical and NLP R code are available on request. Data are protected data from Weill Cornell Medical College and may not be redistributed.

References

- 1. Png ME, Yoong JS. Evaluating the cost-effectiveness of lifestyle modification versus metformin therapy for the prevention of diabetes in Singapore. PLoS One 2014;9:e107225 10.1371/journal.pone.0107225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moin T, Duru OK, Mangione CM. Metformin prescription for insured adults with prediabetes From 2010 to 2012. Ann Intern Med 2015;163:483 10.7326/L15-5136-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hampp C, Borders-Hemphill V, Moeny DG, et al. . Use of antidiabetic drugs in the U.S., 2003-2012. Diabetes Care 2014;37:1367–74. 10.2337/dc13-2289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Flory JH, Hennessy S. Metformin use reduction in mild to moderate renal impairment: possible inappropriate curbing of use based on food and drug administration contraindications. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:458–9. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Raebel MA, Schmittdiel J, Karter AJ, et al. . Standardizing terminology and definitions of medication adherence and persistence in research employing electronic databases. Med Care 2013;51(8 Suppl 3):S11–S21. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31829b1d2a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Flory J, Gerhard T, Stempniewicz N, Keating S, et al. . Comparative adherence to diabetes drugs: An analysis of electronic health records and claims data. Diabetes Obes Metab 2017;19:1184–7. 10.1111/dom.12931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Floyd JS, Wiggins KL, Sitlani CM, et al. . Case-control study of second-line therapies for type 2 diabetes in combination with metformin and the comparative risks of myocardial infarction and stroke. Diabetes Obes Metab 2015;17:1194–7. 10.1111/dom.12537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hugtenburg JG, Timmers L, Elders PJ, et al. . Definitions, variants, and causes of nonadherence with medication: a challenge for tailored interventions. Patient Prefer Adherence 2013;7:675–82. 10.2147/PPA.S29549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Florez H, Luo J, Castillo-Florez S, et al. . Impact of metformin-induced gastrointestinal symptoms on quality of life and adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes. Postgrad Med 2010;122:112–20. 10.3810/pgm.2010.03.2128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bouchoucha M, Uzzan B, Cohen R. Metformin and digestive disorders. Diabetes Metab 2011;37:90–6. 10.1016/j.diabet.2010.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dujic T, Zhou K, Donnelly LA, et al. . Association of organic cation transporter 1 with intolerance to Metformin in Type 2 Diabetes: A GoDARTS Study. Diabetes 2015;64:1786–93. 10.2337/db14-1388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huang Y, Sun J, Wang X, et al. . Helicobacter pylori infection decreases metformin tolerance in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Technol Ther 2015;17:128–33. 10.1089/dia.2014.0203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sanchez-Rangel E, Inzucchi SE. Metformin: clinical use in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2017;60:1586–93. 10.1007/s00125-017-4336-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nichols GA, Conner C, Brown JB. Initial nonadherence, primary failure and therapeutic success of metformin monotherapy in clinical practice. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:2127–35. 10.1185/03007995.2010.504396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Selby JV, Ettinger B, Swain BE, et al. . First 20 months’ experience with use of metformin for type 2 diabetes in a large health maintenance organization. Diabetes Care 1999;22:38–44. 10.2337/diacare.22.1.38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Okayasu S, Kitaichi K, Hori A, et al. . The evaluation of risk factors associated with adverse drug reactions by metformin in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Biol Pharm Bull 2012;35:933–7. 10.1248/bpb.35.933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hirst JA, Farmer AJ, Ali R, et al. . Quantifying the effect of metformin treatment and dose on glycemic control. Diabetes Care 2012;35:446–54. 10.2337/dc11-1465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schwartz S, Fonseca V, Berner B, et al. . Efficacy, tolerability, and safety of a novel once-daily extended-release metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2006;29:759–64. 10.2337/diacare.29.04.06.dc05-1967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Donnelly LA, Morris AD, Pearson ER. Adherence in patients transferred from immediate release metformin to a sustained release formulation: a population-based study. Diabetes Obes Metab 2009;11:338–42. 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2008.00973.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gao H, Xiao W, Wang C, et al. . The metabolic effects of once daily extended-release metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes: a multicentre study. Int J Clin Pract 2008;62:695–700. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01733.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Alsultan M, Al-Omar H, Vandewalle B, et al. . Metformin extended versus immediate release In Saudi Arabia: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Value in Health 2017;20:A479 10.1016/j.jval.2017.08.456 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. The Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP). Diabetes Care 2002;25:2165–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. The UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). Lancet 1998;352:854–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-021505supp001.pdf (182.8KB, pdf)