Abstract

Objective

The pathogenesis of keloid is largely unknown. Because keloid and atopic dermatitis have overlapping pathophysiological mechanisms, we aimed to evaluate keloid risk in patients with atopic dermatitis.

Study design

Population-based retrospective cohort study.

Setting

The Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database was used to analyse data for people who had been diagnosed with atopic dermatitis.

Participants

We identified 8371 patients with newly diagnosed atopic dermatitis during 1996–2010. An additional 33 484 controls without atopic dermatitis were randomly identified and frequency matched at a one-to-four ratio.

Primary and secondary outcome measure

The association between atopic dermatitis and keloid risk was estimated using Cox proportional hazard regression models.

Results

After adjustment for covariates, the atopic dermatitis patients have a 3.19-fold greater risk of developing keloid compared with the non-atopic dermatitis group (3.19vs1.07 per 1000 person-years, respectively). During the study period, 163 patients with atopic dermatitis and 532 patients without atopic dermatitis developed keloid. Notably, keloid risk increased with severity of atopic dermatitis, particularly in patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that patients with atopic dermatitis had a higher than normal risk of developing keloid and suggest that atopic dermatitis may be an independent risk factor for keloid.

Keywords: keloid; dermatitis, atopic; national health programs

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The cohort study evaluates the risk of developing keloids in patients with atopic dermatitis by using multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression models.

This study was based on secondary dataset, which encrypted patient information to keep privacy.

The strengths of this study are the large population size, the same ethnic group and long follow-up period.

Detailed personal information including risk factors was not found in the database, which compromised our findings and hindered further analyses.

All insurance reimbursement was peer reviewed and checked by well- trained specialists.

Introduction

Keloid is a pathological disorder as a result of dermal injury and excess production in the extracellular matrix (ECM) (mainly type I collagen and proteoglycans). Keloids are characterised by concomitant annoying symptoms such as pain and pruritus. The recurrence rate after surgical excision is high. The pathogenesis of keloids is largely unknown,1 2 and no standard treatment has emerged. Although the cause of this disorder is not well understood, known risk factors for keloids are age 10–30 years, female gender3 4 and dark skin pigmentation (eg, in Asian, African-American and Hispanic people). Notably, the risk of keloid development is highest in populations with the darkest complexions.5 6

In a recent case–control study performed in Northeast China, comparisons of blood test results for 283 subjects with keloids and 290 controls suggested that keloid development may be associated with the single-nucleotide polymorphisms, a disintegrin and metalloprotease 33 (ADAM33).1 Earlier studies have also shown that ADAM33 is associated with immune-mediated disorders such as atopic dermatitis (AD).7 8 In the first epidemiological study of the relationship between ADAM33 gene polymorphisms and AD risk, Matsusue et al reported a significant association between ADAM33 gene polymorphisms and AD in comparisons of 140 children with AD and 258 healthy controls recruited from June 2006 to January 2007. We hypothesised that AD and keloids may develop through common pathways, particularly in the ADAM33-related gene. Since no population-based data were available for investigating the association between AD and keloids, this study retrospectively analysed data from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) to investigate this relationship.

Materials and methods

Source of data

The data used in this population-based cohort study were obtained from the NHIRD established by the Taiwan national healthcare system. This encrypted secondary database, which was implemented in March 1995 contains medical reports for almost 99% of the 23.74 million residents of Taiwan. The NHIRD contains records of medical services and enrolment data for all beneficiaries. The database is publicly available to researchers, but its use is strictly regulated by Taiwan Personal Electronic Data Protection Law. The NHIRD has been used in many studies published in scientific journals.9–11 The current study used the Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2010, in which diseases are coded according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM).

The study was proceeded according to Declaration of Helsinki guidelines. Because all NHIRD data had been deidentified and personal information traced was anonymised before data analysis, informed consent was not needed.

Study design

We examined medical claims and identified 8371 patients who had at least one AD diagnosis (ICD-9-CM code 691.8) during 1996–2010.12 To ensure accurate data, the analysis was limited to patients who had received ≥3 AD diagnoses during outpatient visits or ≥1 AD diagnoses during inpatient medical service. The date of the first clinical visit for AD was defined as the index date. Patients with moderate to severe AD were defined as patients who had received systemic corticosteroids.13–16 The exclusion criterion was any diagnosis of a keloid (ICD-9-CM code 701.4) before the index date.17 During the follow-up period, the occurrence of keloid was defined as ≥3 keloid diagnoses in outpatient visits or ≥1 keloid diagnoses in inpatient medical service. The two cohorts were limited to patients who had an ICD-9 code for keloid assigned by a dermatologist. Another 33 484 controls without AD were randomly identified after eliminating study case cohort and frequency matched at a one-to-four ratio for age, gender and index year (year of AD diagnosis).18 Both cohorts were followed up until 31 December 2010, or until the occurrence of keloids. Figure 1 shows a flow chart of the study procedure.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram summarising the process of the enrolment. LHID, Longitudinal Health Insurance Database.

Ethics approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines.

Measures and definition

As in previous NHIRD studies, the patients were classified into three urbanisation levels according to their residence addresses recorded in the databases: urban (those living in the ‘city’), suburban (those living in ‘Jeng’ areas) and rural (those living in ‘Xiang’ areas).19–21

In addition to demographic risk factors (urbanisation level, gender and age), concurrent allergic diseases identified by ICD-9-CM codes in the claims records before the index date included asthma (ICD-9-CM code 493), allergic rhinitis (ICD-9-CM code 477) and allergic conjunctivitis (ICD-9-CM code 372.05, 372.10 and 372.14). Baseline comorbidities were also identified by ICD-9-CM codes, including hypertension (ICD-9-CM codes 401–405), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (ICD-9-CM code 491, 492, 494 and 496), hyperlipidaemia (ICD-9-CM code 272), chronic kidney disease (ICD-9-CM code 582, 583, 585, 586 and 588), diabetes mellitus (ICD-9-CM code 250), chronic liver disease (ICD-9-CM code 571), stroke (ICD-9-CM code 430–438), mental disorders (ICD-9-CM code 290–319), coronary artery disease (ICD-9-CM code 410–414) and alcohol-attributed disease (ICD-9-CM codes 291.0–9, 303, 305.0,357.5, 425.5, 535.3, 571.0–3980.0 and V11.3). Concurrent allergic diseases and comorbidities were ascertained at least more than two outpatient claims during study periods.

Statistical analysis

We used χ2 test to compare distributions of categorical demographic and clinical characteristics between the AD and non-AD control cohorts. Student’s t-test and Wilcoxon rank-sum test were used to compare mean age and follow-up time (y) between the two cohorts, as appropriately. In the patients with AD, survival time was calculated until hospitalisation, an ambulatory visit for keloids or the end of the study period (31 December 2010), whichever came first. Keloid incidence rates per 1000 person-years were compared between the two cohorts. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to estimate cumulative incidence of keloids, and the differences between the curves were compared by two-tailed log-rank test. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression models were used to calculate HRs and 95% CIs for keloids in patients with AD when the proportional hazards assumption was satisfied. Multivariate Cox models were adjusted for age, gender, urbanisation level, concurrent allergic diseases and relevant comorbidities. Statistical Analysis Software, V.9.4 was used for data analyses; a p value less than 0.05 in a two-tailed test was considered statistically significant.

Patient and public involvement

There were neither patients nor the public involved in this study.

Results

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics and comorbidities of patients in the AD and non-AD cohorts. In the AD cohort, 50.71% patients were younger than 40 years old, and 64.81% patients were female. Compared with the non-AD cohort, the AD cohort had significantly higher percentages of patients with asthma (25.41 vs 12.91, p<0.001), allergic rhinitis (54.78 vs 35.92, p<0.001), allergic conjunctivitis (57.22 vs 42.08, p<0.001), hypertension (34.09 vs 21.60, p<0.001), diabetes mellitus (23.51 vs 13.46, p<0.001), hyperlipidaemia (34.56 vs 21.08, p<0.001), chronic kidney disease (12.03 vs 6.20, p<0.001), chronic liver disease (35.83 vs 21.98, p<0.001), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (26.74 vs 15.08, p<0.001), stroke (5.85 vs 2.97, p<0.001), coronary artery disease (5.02 vs 2.71, p<0.001), mental disorders (18.05 vs 11.33, p<0.001) and alcohol-attributable disease (3.72 vs 2.28, p<0.001). During a median observation time of 1.9 years, 1.95% (163) of the patients with AD had keloids (IQR=0.8–4.3). The incidence of keloids was significantly (p=0.022) higher in the AD cohort compared with the non-AD cohort (532 patients with keloids out of 33 484 controls matched for age, and gender (1.59%)) during a median observation time of 9.0 years (IQR=6.2–11.8)). The median duration of follow-up for keloids was significantly shorter in the AD group (1.9 years) compared with the non-AD group (9.0 years).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with and without atopic dermatitis

| Variables | Atopic dermatitis | P values | |

| Yes (n=8371) | No (n=33 484) | ||

| Keloid patients, n (%) | 163 (1.95) | 532 (1.59) | 0.022 |

| Period of developing keloid, median (IQR), years | 1.9 (0.8–4.3) | 9.0 (6.2–11.8) | <0.001 |

| Mean age at diagnosis of keloid, years | 33.1 (14.8) | 36.8 (14.4) | <0.001 |

| Age group, n (%) | |||

| <40 | 4245 (50.71) | 16 980 (50.71) | |

| 40–59 | 2601 (31.07) | 10 404 (31.07) | |

| ≥60 | 1525 (18.22) | 6100 (18.22) | 1.000 |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Men | 2946 (35.19) | 11 784 (35.19) | |

| Women | 5425 (64.81) | 21 700 (64.81) | 1.000 |

| Degree of urbanisation, n (%) | |||

| Urban | 5267 (62.92) | 20 463 (61.11) | |

| Suburban | 1332 (15.91) | 5665 (16.92) | |

| Rural | 1772 (21.17) | 7356 (21.97) | 0.008 |

| Concurrent allergic disease, n (%) | |||

| Asthma | 2127 (25.41) | 4323 (12.91) | <0.001 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 4586 (54.78) | 12 028 (35.92) | <0.001 |

| Allergic conjunctivitis | 4790 (57.22) | 14 089 (42.08) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 2854 (34.09) | 7232 (21.60) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1968 (23.51) | 4508 (13.46) | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 2893 (34.56) | 7059 (21.08) | <0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1007 (12.03) | 2076 (6.20) | <0.001 |

| Chronic liver disease | 2999 (35.83) | 7361 (21.98) | <0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 2238 (26.74) | 5050 (15.08) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 490 (5.85) | 994 (2.97) | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 420 (5.02) | 909 (2.71) | <0.001 |

| Mental disorders | 1511 (18.05) | 3794 (11.33) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol attributed disease | 311 (3.72) | 765 (2.28) | <0.001 |

Table 2 stratifies the keloid incidence rates and HRs by age, gender and concurrent allergic disease or comorbidity. During the follow-up period, keloids developed in 1.95% (163) of the patients with AD and in 1.59% (532) of the patients without AD. The overall keloid risk was 3.19 times greater in the AD group compared with the non-AD group (3.19 vs 1.07 per 1000 person-years, respectively) after adjusting for age, gender, urbanisation level, concurrent allergic diseases (asthma, allergic rhinitis and allergic conjunctivitis) and related comorbidities (hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, diabetes mellitus, chronic liver disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney diseases, stroke, mental disorders, coronary artery disease and alcohol attributed disease).

Table 2.

Incidence and HRs of keloid by demographic characteristics and concurrent allergic disease or comorbidity among patients with or without atopic dermatitis

| Variables | Patients with atopic dermatitis | Patients without atopic dermatitis | Compared with non-atopic dermatitis | ||||||

| Keloid | PYs | Rate | Keloid | PYs | Rate | Crude HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR* (95% CI) | Adjusted HR† (95% CI) | |

| Overall | 163 | 50 990.85 | 3.19 | 532 | 499087.75 | 1.07 | 3.84 (3.17 to 4.66)‡ | 3.80 (3.14 to 4.61)‡ | 3.19 (2.60 to 3.89)‡ |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Men | 47 | 17 992.05 | 2.61 | 123 | 176032.98 | 0.69 | 4.81 (3.31 to 6.99)‡ | 4.72 (3.24 to 6.85)‡ | 3.67 (2.47 to 5.44)‡ |

| Women | 116 | 32 998.80 | 3.52 | 409 | 323054.76 | 1.27 | 3.56 (2.84 to 4.45)‡ | 3.53 (2.82 to 4.42)‡ | 3.03 (2.39 to 3.83)‡ |

| Stratify by age (years) | |||||||||

| <40 | 122 | 26 311.81 | 4.64 | 75 | 63 234.61 | 1.19 | 4.07 (3.27 to 5.07)‡ | 4.07 (3.27 to 5.08)‡ | 3.44 (2.74 to 4.31)‡ |

| 40–59 | 30 | 15 707.99 | 1.91 | 29 | 38 829.76 | 0.75 | 3.31 (2.19 to 4.99)‡ | 3.32 (2.20 to 4.99)‡ | 2.74 (1.79 to 4.17)‡ |

| ≥60 | 11 | 8971.06 | 1.23 | 11 | 22 791.71 | 0.48 | 2.87 (1.49-5.56)§ | 2.82 (1.46-5.44)§ | 2.36 (1.22-4.59)¶ |

| Concurrent allergic disease** | |||||||||

| No | 22 | 9661.48 | 2.28 | 139 | 194784.11 | 0.71 | 5.41 (4.02 to 7.27)‡ | 4.03 (2.55 to 6.37)‡ | 4.41 (3.27 to 5.94)‡ |

| Yes | 141 | 41 329.37 | 3.41 | 393 | 304303.64 | 1.29 | 3.19 (2.52 to 4.05)‡ | 3.34 (2.72 to 4.12)‡ | 2.62 (2.05 to 3.34)‡ |

| Comorbidity†† | |||||||||

| No | 59 | 14 141.34 | 4.17 | 247 | 246626.44 | 1.00 | 4.13 (2.62 to 6.52)‡ | 4.85 (3.61 to 6.52)‡ | 3.78 (2.38 to 5.98)‡ |

| Yes | 104 | 36 849.51 | 2.82 | 285 | 252461.31 | 1.12 | 3.37 (2.74 to 4.15)‡ | 2.82 (2.22 to 3.58)‡ | 3.08 (2.48 to 3.82)‡ |

*Model adjusted for age and gender.

†Model adjusted for age, gender, urbanisation, concurrent allergic diseases (asthma, allergic rhinitis and allergic conjunctivitis)and relevant comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidaemia, chronic kidney diseases, chronic liver disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke, coronary artery disease, mental disorders and alcohol attributed disease).

‡P<0.001.

§P=0.002.

¶P=0.011.

**Patients with any concurrent allergic disease, including asthma, allergic rhinitis and allergic conjunctivitis, were classified as the allergic disease group.

††Patients with any examined comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidaemia, chronic kidney diseases, chronic liver disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke, coronary artery disease, mental disorders and alcohol attributed disease, were classified as the comorbidity group.

PYs, person-years; rate, incidence rate in per 1000 person-years.

In both the AD and non-AD cohorts, gender-specific analyses showed that the incidence of keloids was higher in women than in men (3.52 and 2.61 per 1000 person-years, respectively, in the AD cohort; 1.27 vs 0.69 per 1000 person-years, respectively, in the non-AD cohort). However, men in the AD group had a significantly higher keloid risk compared with men in the non-AD group (adjusted HR=3.67, 95% CI 2.47 to 5.44) and women in the AD group had a significantly higher keloid risk compared with women in the non-AD group (adjusted HR=3.03, 95% CI 2.39 to 3.83).

In all age groups, the AD cohort also had a significantly higher incidence of keloids compared with the non-AD cohort. Age-specific risk comparisons showed that compared with the non-AD cohort, the AD cohort had a significantly higher keloid risk in all age groups, and the risk was highest in patients under 40 years old. Keloid risk was higher in patients with AD than in patients without AD, regardless of concurrent allergic disease or comorbidity.

Table 3 shows that keloid risk increased with severity of AD, particularly in patients with moderate to severe AD.

Table 3.

Incidence rates and HRs of keloid risk in patients with different severity of atopic dermatitis

| Variables | N | keloid | Rate | Crude HR (95% CI) | Crude HR (95% CI) | AdjustedHR* (95% CI) | Adjusted HR* (95% CI) |

| Without atopic dermatitis | 33 484 | 532 | 1.07 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| With atopic dermatitis | 8371 | 163 | 3.19 | 3.84 (3.17 to 4.66)† | 3.19 (2.60 to 3.89)† | ||

| Mild | 5193 | 81 | 2.58 | 3.10 (2.42 to 3.97)† | 1.00 (reference) | 2.54 (1.98 to 3.27)† | 1.00 (reference) |

| Moderate to severe | 3178 | 82 | 4.19 | 5.02 (3.93 to 6.42)† | 1.62 (1.19-2.21)‡ | 4.39 (3.38 to 5.70)† | 1.73 (1.26 to 2.36)† |

*Model adjusted for age, gender, urbanisation, concurrent allergic diseases (asthma, allergic rhinitis and allergic conjunctivitis) and relevant comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidaemia, chronic kidney diseases, chronic liver disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke, coronary artery disease, mental disorders and alcohol attributed disease).

†P<0.001.

‡P=0.002.

IRR, incidence rate ratio; PYs, person-years; rate, incidence rate in per 1000 person-years.

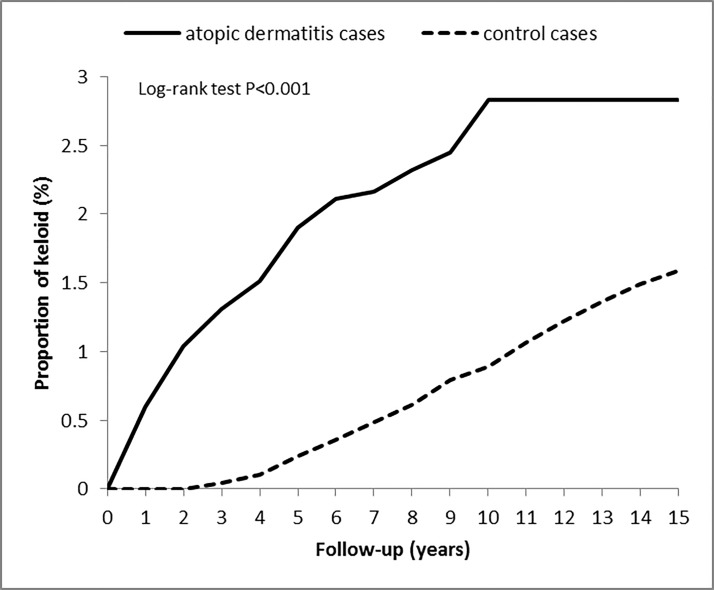

Figure 2 compares the Kaplan-Meier curves for the cumulative incidence of keloids between the AD and non-AD groups at the 15-year follow-up. The baseline risk of keloid development was significantly higher in the AD group (2.83%, p<0.001) compared with the non-AD group (1.59%). The Kaplan-Meier curves also showed a significantly higher cumulative incidence of keloids in the AD group compared with the non-AD group (log-rank test, p<0.001).

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of keloid among patients with atopic dermatitis and the control cohort. The incidence of keloid in atopic dermatitis patients and controls was compared using the log-rank test by a Kaplan-Meier analysis.

Discussion

The above comparisons supported our study hypothesis that patients with AD have a higher than normal risk of subsequently developing keloids. This study is the first to demonstrate an association between AD and keloids in an Asian population. The keloid risk was 3.19-fold higher in the AD group compared with the non-AD group. Notably, the females in the AD group had a significantly higher incidence rate of keloids compared with males. Specifically, compared with patients in the non-AD group, the AD group had a significantly higher keloid risk in all age groups, especially in those less than 40 years old. In the AD group, keloid risk was significantly associated with the presence of comorbidities and concurrent allergic diseases and keloid risk increased with the severity of AD.

Previous studies of the association between AD and keloids have obtained inconsistent results. In Hajdarbegovic et al,7 for example, a case–control study of 131 patients with keloids and 258 controls recruited during 2000–2012 revealed no association between AD and keloids in the adjusted model (adjusted OR 1.27; 95% CI 0.76 to 2.13). However, the questionnaire-based reporting method used in that study may have caused information bias resulting in under-diagnosis of AD. Another limitation is that the authors did not report AD-compatible itchy flexural rash with AD, which may have also contributed to underdiagnosis of AD. Underdiagnosis of keloids is also common because patients with keloids are often immigrants, who may be unaccustomed to seeking prompt medical attention for non-critical medical problems. Additionally, the diverse ancestry of the population analysed in Hajdarbegovic et al7 may have had a confounding effect on the association between AD and keloids. A final limitation of Hajdarbegovic et al is its small sample size.

Although the exact mechanisms underlying the relationship between AD and keloids are unclear, several possible links have been hypothesised. First, thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), an interleukin (IL)-7-like cytokine, is believed to cause Th2-type inflammatory responses.22 23 Upregulation of Th2 cytokines may be linked to atopic diseases.24 The TSLP is also reportedly linked to AD. In 2010, Lee et al collected sera from 232 children, including 75 with AD. Comparisons showed higher serum TSLP in children with AD compared with normal controls. Studies of patients with AD also indicate that skin lesions are associated with increased TSLP gene expression.25 In another recent study, Shin et al2 showed that TSLP expression was higher in keloidal tissue compared with normal tissue. Their data showed that by inducing production of collagen and tissue growth factor beta (TGF-β), TSLP contributes to excessive deposition of ECM. Since TSLP expression is apparently associated with keloids in patients with AD, keloids and AD may be induced through similar inflammatory pathways.

Periostin, which is in the fasciclin family of proteins, has important functions in the ECM and is also a matricellular protein associated with allergic inflammation.26 Kou et al reported that periostin expression in serum or in inflamed sites of patients with AD was associated with the clinical severity of AD, which suggests that periostin mediates AD.27 28 Furthermore, periostin can activate TGF-β and NF-κB to induce IL-6 in eosinophils and lead keratinocytes to produce TSLP. Periostin in fibroblasts can then be induced by activated eosinophils through TGF-β reciprocally. Besides, Zhou et al29 reported that increased expression of periostin was found in keloid scars. Since periostin participates in the epithelial–mesenchymal transition, periostin is important in forming both AD and keloids.

Sirtuins, which are class III histone deacetylases, are implicated in fibrotic disease, inflammation and cellular proliferation, apoptosis and differentiation.30 Ming et al demonstrated that loss of sirtuin can reduce the epidermal formation of filaggrin, resulting in disruption of the epidermal barrier and a predisposition to occurrence of AD.31 32 Bai et al33 showed that expression of sirtuin was suppressed in fibrotic scarring and that sirtuin deletion enhanced fibrotic wound healing. Sirtuin overexpression can attenuate the expression of ECM induced by TGF-β. Loss of sirtuin leads to both AD development and excessive fibrotic scarring. Finally, we hypothesised that individuals with AD may be predisposed to subsequent development of keloids.

TGF-β is a main fibrotic growth factor involved in wound healing and tissue repair.34 Upregulation of TGF-β gene with proinflammation cytokines was found in keloids,35 36 resulting in keloidal fibroblasts formation together with collagen synthesis.37 Previously mentioned literatures showed periostin, TSLP and loss of sirtuins can activate TGF-β in AD and keloids. Therefore, patients with AD are prone to develop keloids.

Psychological stress can trigger various physiological responses in the endocrine, nervous and immune systems.38–45 Psychoemotional stress is associated with a higher than normal incidence of several skin diseases including AD,38 46–53and it is also known to aggravate AD. Anxiety and depression have been reported to correlate with AD.54–56 In Chen et al,55 the patients with AD had a higher risk of developing major depression, any depressive disorder and anxiety disorders in later life. Other studies have reported an association between anxiety and keloids.57 In Furtado et al57, for example, psychological stress was evaluated in 25 patients with keloids before undergoing surgical resection and postoperative radiotherapy. They found that stress had a direct correlation with development of keloids. Notably, the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis has a well-known mediating role in the eventual contributing effects of psychological stress on development of both AD and keloids.48 58 Psychological stress also increases concentrations of nerve growth factor (NGF).59 Ewa and colleagues demonstrated that comparing to healthy ones, patients with AD had significant increased plasma levels of substance Pand NGF.60 The NGF is made by keratinocytes and contributes to neurogenic inflammation.61 Akaishi et al found that neurogenic inflammation has an important role in keloid formation.62 Therefore, we suggest that AD should be considered a risk factor for keloids.

A notable strength of this study is the use of a large representative population-based dataset, which enabled analysis of all cases of AD and keloids during the study period. Moreover, the large sample size also provided sufficient statistical power to compare the complex relationships between these two diseases in the AD and non-AD groups. Notably, since most of the Taiwan population is ethnic Chinese, analysis of this population may yield valuable insights into the roles of genetic ancestry in AD and keloids. However, several limitations of this study are noted. First, the data analysed in this study were originally collected for insurance purposes rather than for research purposes. Second, data for diagnoses of AD and keloids in the study population were based on ICD-9-CM codes entered by different doctors, which may have introduced coding errors. The Taiwan Bureau of National Health Insurance has attempted to minimise this problem by performing regular audits and by imposing large fines on hospitals that make coding errors. Nevertheless, the NHIRD has been rigorously examined and extensively used in many studies in recent years.63–65 Third, despite the relatively low healthcare costs in Taiwan, some patients attempt to eliminate AD and keloids through folk remedies or through private treatment by local pharmacists rather than by medical professionals. Moreover, the NHIRD does not record all information regarding risk factors such as body mass index, blood groups, smoking, alcohol consumption and operation sites, which potentially compromises our results. Lacking information about trauma history, anatomical sites, keloid size and number, acne and the different methods of surgery is also a flaw in the report. Finally, the retrospective design of this study only revealed statistically significant relationships. Further studies are needed to validate actual causal relationships. Further clinical trials are needed to clarify the underlying mechanisms of this association.

In conclusion, this study showed that AD is associated with development of keloids and suggested that AD could be an important risk factor in the future development of keloids. Nevertheless, further studies are needed to clarify this association and to explore pathophysiological mechanisms that are common to AD and keloids.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: Substantial contributions to conception and design: Y-YL, C-CL, W-WY, Q-RW, LZ and C-HW. Drafting and revising the article critically for important intellectual content: Y-YL, Q-RW, C-LZ, C-CL and C-HW. Final approval of the version to be published: Y-YL and C-HW.

Funding: The study was supported by Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital (VGHKS-106-68) (VGHKS-107-70).

Disclaimer: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Han J, Han J, Yu D, et al. Association of ADAM33 gene polymorphisms with keloid scars in a northeastern Chinese population. Cell Physiol Biochem 2014;34:981–7. 10.1159/000366314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shin JU, Kim SH, Kim H, et al. TSLP Is a Potential initiator of collagen synthesis and an activator of CXCR4/SDF-1 axis in keloid pathogenesis. J Invest Dermatol 2016;136:507–15. 10.1016/j.jid.2015.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Viera MH, Caperton CV, Berman B. Advances in the treatment of keloids. J Drugs Dermatol 2011;10:468–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jones ME, Hardy C, Ridgway J. Keloid management: a retrospective case review on a new approach using surgical excision, platelet-rich plasma, and in-office superficial photon X-ray radiation therapy. Adv Skin Wound Care 2016;29:303–7. 10.1097/01.ASW.0000482993.64811.74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bissek AC, Tabah EN, Kouotou E, et al. The spectrum of skin diseases in a rural setting in Cameroon (sub-Saharan Africa). BMC Dermatol 2012;12:7 10.1186/1471-5945-12-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Viera MH, Vivas AC, Berman B. Update on keloid management: clinical and basic science advances. Adv Wound Care 2012;1:200–6. 10.1089/wound.2011.0313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hajdarbegovic E, Bloem A, Balak D, et al. The association between atopic disorders and keloids: a case-control study. Indian J Dermatol 2015;60:635 10.4103/0019-5154.169144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Matsusue A, Kiyohara C, Tanaka K, et al. ADAM33 genetic polymorphisms and risk of atopic dermatitis among Japanese children. Clin Biochem 2009;42:477–83. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2008.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wu CH, Tung YC, Chai CY, et al. Increased risk of osteoporosis in patients with peptic ulcer disease: a nationwide population-based study. Medicine 2016;95:e3309 10.1097/MD.0000000000003309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wu CH, Chai CY, Tung YC, et al. Herpes zoster as a risk factor for osteoporosis: a 15-year nationwide population-based study. Medicine 2016;95:e3943 10.1097/MD.0000000000003943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wu CH, Tung YC, Lin TK, et al. Hip fracture in people with erectile dysfunction: a nationwide population-based cohort study. PLoS One 2016;11:e0153467 10.1371/journal.pone.0153467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wu LC, Hwang CY, Chung PI, et al. Autoimmune disease comorbidities in patients with atopic dermatitis: a nationwide case-control study in Taiwan. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2014;25:586–92. 10.1111/pai.12274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shreberk-Hassidim R, Hassidim A, Gronovich Y, et al. Atopic dermatitis in Israeli Adolescents from 1998 to 2013: trends in time and association with migraine. Pediatr Dermatol 2017;34:247–52. 10.1111/pde.13084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Katayama I, Aihara M, Ohya Y, et al. Japanese guidelines for atopic dermatitis 2017. Allergol Int 2017;66:230–47. 10.1016/j.alit.2016.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Werfel T, Schwerk N, Hansen G, et al. The diagnosis and graded therapy of atopic dermatitis. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2014;111:509–20. 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ricci G, Dondi A, Patrizi A, et al. Systemic therapy of atopic dermatitis in children. Drugs 2009;69:297–306. 10.2165/00003495-200969030-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sun LM, Wang KH, Lee YC. Keloid incidence in Asian people and its comorbidity with other fibrosis-related diseases: a nationwide population-based study. Arch Dermatol Res 2014;306:803–8. 10.1007/s00403-014-1491-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Flohr C, Mann J. New insights into the epidemiology of childhood atopic dermatitis. Allergy 2014;69:3–16. 10.1111/all.12270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shyu CS, Lin HK, Lin CH, et al. Prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in patients with pediatric allergic disorders: a nationwide, population-based study. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2012;45:237–42. 10.1016/j.jmii.2011.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chien IC, Chang KC, Lin CH, et al. Prevalence of diabetes in patients with bipolar disorder in Taiwan: a population-based national health insurance study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2010;32:577–82. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen CY, Liu CY, Su WC, Wc S, et al. Factors associated with the diagnosis of neurodevelopmental disorders: a population-based longitudinal study. Pediatrics 2007;119:e435–e443. 10.1542/peds.2006-1477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu YJ. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin: master switch for allergic inflammation. J Exp Med 2006;203:269–73. 10.1084/jem.20051745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sano Y, Masuda K, Tamagawa-Mineoka R, et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin expression is increased in the horny layer of patients with atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Immunol 2013;171:330–7. 10.1111/cei.12021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Irvine AD, McLean WH, Leung DY. Filaggrin mutations associated with skin and allergic diseases. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1315–27. 10.1056/NEJMra1011040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lee EB, Kim KW, Hong JY, et al. Increased serum thymic stromal lymphopoietin in children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2010;21:e457–e460. 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2009.00919.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Izuhara K, Nunomura S, Nanri Y, et al. Periostin in inflammation and allergy. Cell Mol Life Sci 2017;74:4293–303. 10.1007/s00018-017-2648-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Masuoka M, Shiraishi H, Ohta S, et al. Periostin promotes chronic allergic inflammation in response to Th2 cytokines. J Clin Invest 2012;122:2590–600. 10.1172/JCI58978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kou K, Okawa T, Yamaguchi Y, et al. Periostin levels correlate with disease severity and chronicity in patients with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol 2014;171:283–91. 10.1111/bjd.12943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhou HM, Wang J, Elliott C, et al. Spatiotemporal expression of periostin during skin development and incisional wound healing: lessons for human fibrotic scar formation. J Cell Commun Signal 2010;4:99–107. 10.1007/s12079-010-0090-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Serravallo M, Jagdeo J, Glick SA, et al. Sirtuins in dermatology: applications for future research and therapeutics. Arch Dermatol Res 2013;305:269–82. 10.1007/s00403-013-1320-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ming M, Zhao B, Shea CR, et al. Loss of sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) disrupts skin barrier integrity and sensitizes mice to epicutaneous allergen challenge. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;135:936–45. 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.09.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nomura T, Kabashima K. Advances in atopic dermatitis in 2015. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016;138:1548–55. 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bai XZ, Liu JQ, Yang LL, et al. Identification of sirtuin 1 as a promising therapeutic target for hypertrophic scars. Br J Pharmacol 2016;173:1589–601. 10.1111/bph.13460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fujiwara M, Muragaki Y, Ooshima A. Upregulation of transforming growth factor-beta1 and vascular endothelial growth factor in cultured keloid fibroblasts: relevance to angiogenic activity. Arch Dermatol Res 2005;297:161–9. 10.1007/s00403-005-0596-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu W, Wang DR, Cao YL. TGF-beta: a fibrotic factor in wound scarring and a potential target for anti-scarring gene therapy. Curr Gene Ther 2004;4:123–36. 10.2174/1566523044578004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chen W, Fu X, Sun X, et al. Analysis of differentially expressed genes in keloids and normal skin with cDNA microarray. J Surg Res 2003;113:208–16. 10.1016/S0022-4804(03)00188-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Andrews JP, Marttala J, Macarak E, et al. Keloids: the paradigm of skin fibrosis - Pathomechanisms and treatment. Matrix Biol 2016;51:37–46. 10.1016/j.matbio.2016.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hall JM, Cruser D, Podawiltz A, et al. Psychological stress and the cutaneous immune response: roles of the HPA axis and the sympathetic nervous system in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Dermatol Res Pract 2012;2012:1–11. 10.1155/2012/403908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dhabhar FS, Miller AH, McEwen BS, et al. Effects of stress on immune cell distribution. Dynamics and hormonal mechanisms. J Immunol 1995;154:5511–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bowers SL, Bilbo SD, Dhabhar FS, et al. Stressor-specific alterations in corticosterone and immune responses in mice. Brain Behav Immun 2008;22:105–13. 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dhabhar FS, McEwen BS. Acute stress enhances while chronic stress suppresses cell-mediated immunity in vivo: a potential role for leukocyte trafficking. Brain Behav Immun 1997;11:286–306. 10.1006/brbi.1997.0508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Altemus M, Rao B, Dhabhar FS, et al. Stress-induced changes in skin barrier function in healthy women. J Invest Dermatol 2001;117:309–17. 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2001.01373.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dhabhar FS. Acute stress enhances while chronic stress suppresses skin immunity. The role of stress hormones and leukocyte trafficking. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2000;917:876–93. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05454.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dhabhar FS, McEwen BS. Enhancing versus suppressive effects of stress hormones on skin immune function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999;96:1059–64. 10.1073/pnas.96.3.1059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dhabhar FS, Miller AH, Stein M, et al. Diurnal and acute stress-induced changes in distribution of peripheral blood leukocyte subpopulations. Brain Behav Immun 1994;8:66–79. 10.1006/brbi.1994.1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hochman B, Isoldi FC, Furtado F, et al. New approach to the understanding of keloid: psychoneuroimmune-endocrine aspects. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2015;8:67–73. 10.2147/CCID.S49195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Misery L, Touboul S, Vinçot C, et al. [Stress and seborrheic dermatitis]. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2007;134:833–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Suárez AL, Feramisco JD, Koo J, et al. Psychoneuroimmunology of psychological stress and atopic dermatitis: pathophysiologic and therapeutic updates. Acta Derm Venereol 2012;92:7–15. 10.2340/00015555-1188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yu R, Huang Y, Zhang X, et al. Potential role of neurogenic inflammatory factors in the pathogenesis of vitiligo. J Cutan Med Surg 2012;16:230–44. 10.1177/120347541201600404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hadshiew IM, Foitzik K, Arck PC, et al. Burden of hair loss: stress and the underestimated psychosocial impact of telogen effluvium and androgenetic alopecia. J Invest Dermatol 2004;123:455–7. 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23237.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chida Y, Mao X. Does psychosocial stress predict symptomatic herpes simplex virus recurrence? A meta-analytic investigation on prospective studies. Brain Behav Immun 2009;23:917–25. 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yosipovitch G, Tang M, Dawn AG, et al. Study of psychological stress, sebum production and acne vulgaris in adolescents. Acta Derm Venereol 2007;87:135–9. 10.2340/00015555-0231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Manolache L, Benea V. Stress in patients with alopecia areata and vitiligo. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2007;21:921–8. 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.02106.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hashizume H, Takigawa M. Anxiety in allergy and atopic dermatitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2006;6:335–9. 10.1097/01.all.0000244793.03239.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cheng CM, Hsu JW, Huang KL, et al. Risk of developing major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders among adolescents and adults with atopic dermatitis: a nationwide longitudinal study. J Affect Disord 2015;178:60–5. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hashiro M, Okumura M. Anxiety, depression and psychosomatic symptoms in patients with atopic dermatitis: comparison with normal controls and among groups of different degrees of severity. J Dermatol Sci 1997;14:63–7. 10.1016/S0923-1811(96)00553-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Furtado F, Hochman B, Farber PL, et al. Psychological stress as a risk factor for postoperative keloid recurrence. J Psychosom Res 2012;72:282–7. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Sheridan JF, Padgett DA, Avitsur R, et al. Experimental models of stress and wound healing. World J Surg 2004;28:327–30. 10.1007/s00268-003-7404-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Joachim RA, Kuhlmei A, Dinh QT, et al. Neuronal plasticity of the "brain-skin connection": stress-triggered up-regulation of neuropeptides in dorsal root ganglia and skin via nerve growth factor-dependent pathways. J Mol Med 2007;85:1369–78. 10.1007/s00109-007-0236-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Teresiak-Mikołajczak E, Czarnecka-Operacz M, Jenerowicz D, et al. Neurogenic markers of the inflammatory process in atopic dermatitis: relation to the severity and pruritus. Postepy Dermatol Alergol 2013;30:286–92. 10.5114/pdia.2013.38357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Tominaga M, Takamori K. Itch and nerve fibers with special reference to atopic dermatitis: therapeutic implications. J Dermatol 2014;41:205–12. 10.1111/1346-8138.12317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Akaishi S, Ogawa R, Hyakusoku H. Keloid and hypertrophic scar: neurogenic inflammation hypotheses. Med Hypotheses 2008;71:32–8. 10.1016/j.mehy.2008.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wu CH, Zhang ZH, Wu MK, et al. Increased migraine risk in osteoporosis patients: a nationwide population-based study. Springerplus 2016;5:1378 10.1186/s40064-016-3090-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wu CH, Lu YY, Chai CY, et al. Increased risk of osteoporosis in patients with erectile dysfunction: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Medicine 2016;95:e4024 10.1097/MD.0000000000004024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wu CH, Tsai TH, Su YF, et al. Traumatic Brain Injury and Substance Related Disorder: A 10-Year Nationwide Cohort Study in Taiwan. Neural Plast 2016;2016:8030676 10.1155/2016/8030676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.