Abstract

Objective

To examine current trends in the characteristics of patients visiting California emergency departments (EDs) in order to better direct the allocation of acute care resources.

Design

A retrospective study.

Setting

We analysed ED utilisation trends between 2005 and 2015 in California using non-public patient data from California’s Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development.

Participants

We included all ED visits in California from 2005 to 2015.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

We analysed ED visits and visit rates by age, sex, race/ethnicity, payer and urban/rural trends. We further examined age, sex, race/ethnicity and urban/rural trends within each payer group for a more granular picture of the patient population. Additionally, we looked at the proportion of patients admitted from the ED and distribution of diagnoses.

Results

Between 2005 and 2015, the annual number of ED visits increased from 10.2 to 14.2 million in California. ED visit rates increased by 27.8% (p<0.001), with the greatest increases among patients aged 5–19 (37.4%, p<0.001) and 45–64 years (41.1%, p<0.001), non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic patients (56.8% and 48.8%, p<0.001), the uninsured and Medicaid-insured (36.1%, p=0.002; 28.6%, p<0.001) and urban residents (28.3%, p<0.001). The proportion of ED visits resulting in hospitalisation decreased by 18.3%, with decreases across all payer groups.

Conclusions

Our findings reveal an increasing demand for emergency care and may reflect current limitations in accessing care in other parts of the healthcare system. Policymakers may need to recognise the increasingly vital role that EDs are playing in the provision of care and consider ways to incorporate this changing reality into the delivery of health services.

Keywords: emergency department, healthcare delivery, utilization, demand

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study examines patient characteristics and emergency department (ED) use trends longitudinally using a dataset containing all ED visits for the state of California.

California’s initiatives to increase Medicaid enrolment through the Affordable Care Act and Low-Income Health Programmes provide a unique opportunity to study how patient characteristics and healthcare needs have changed over time under continual and gradual efforts to increase healthcare access.

Our data are limited to California residents, potentially limiting the generalisability of our results despite California’s diverse population.

ED visit rates may be slightly overestimated due to the fact that some populations who visit the ED frequently—including patients who are undocumented and homeless or live in nursing homes, extended-care facilities, prisons and mental health facilities—are not accounted for in the population denominator.

Introduction

Emergency departments (EDs) are an integral component of the USA healthcare system, as they provide the only around-the-clock healthcare to all, regardless of a patient’s ability to pay.1 In the past two decades, the annual number of ED visits in the USA has increased by 50%, while the number of EDs has decreased by 11%,2 raising concerns about the ability of EDs to provide accessible care amid the rise in demand for emergency care services. Appropriate allocation of resources to meet such demands may require greater focus on ED utilisation trends, which reflect the changing patterns of patient healthcare needs and reveal possible factors—including patient conditions, healthcare reform or insurance coverage changes—that may contribute to the increase in demand for emergency care.3 4

Despite outpatient and primary care expansions and increased strategies aimed at reducing emergency care demand,5–8 ED visits have continued to rise, with greater reliance on EDs to provide care that may be unavailable in other parts of the healthcare system.9 Previous literature suggests that older patients, minorities, lower-income patients and Medicaid beneficiaries are more likely to use the ED,10 and recent reports have continued to show substantial increases in ED utilisation, especially among Medicaid-insured patients.11 However, most studies have either focused on short-term study periods using limited sample sizes to evaluate the impact of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) or have not incorporated measures to evaluate ED utilisation relative to population changes.12–15

State-level examinations of the association between health insurance and ED use—particularly in the context of ACA reforms—have yielded complex and often conflicting results.16 Although evaluating the impact of the ACA on healthcare utilisation and outcomes remains an important task, our study provides a more comprehensive assessment of how patient characteristics and healthcare needs have changed over an 11-year period in California—one of the largest and most diverse states in the country17—to help better design the necessary policies and programmes to meet patients’ healthcare needs. Additionally, California’s initiatives to increase enrolment in Medicaid (a government health insurance programme for qualified low-income or disabled people) through the ACA and Low-Income Health Programmes provide a unique opportunity to study how patient characteristics and healthcare needs have changed over time under continual and gradual efforts to increase healthcare access. Thus, we sought to examine state-level trends in emergency care demand from 2005 to 2015 in California. Using state-level data, we analysed patient age, sex, race/ethnicity, insurance status and region of care to examine where emergency care demands are most critical and where future resources may be directed to improve care and lessen ED utilisation. We hypothesised that ED visit rates would increase between 2005 and 2015, particularly among minority, Medicaid-insured and uninsured patients.

Methods

Study design and data sources

We obtained 2005–2015 non-public Patient Discharge Data (PDD), Emergency Department Data (EDD), Hospital Annual Financial Data and Hospital Annual Utilization Data from California’s Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD), which conducts annual, standardised surveys required of all hospitals and health service facilities in California.18 19 To account for changes in California’s population over time, we calculated annual ED utilisation rates by age, sex, race/ethnicity, insurance payer and urban/rural residence. We used annual age and sex population estimates provided by the US Census Bureau20 21; state population insurance coverage estimates from the Current Population Survey’s Annual Social and Economic Supplements (for the years 2005–2012) and American Community Survey (for the years 2013–2015)22 23 and race/ethnicity population estimates from the California Department of Finance (for the years 2005-2009) and the US Census Bureau (for the years 2010–2015).24 25

Inclusion criteria and variable definition

We included all ED visits in California from 2005 to 2015 and classified ED visits as inpatient if the visit resulted in a hospital admission and outpatient if the visit resulted in a discharge directly from the ED without admission. All observation stays that initially came through the ED—whether they were admitted to the inpatient setting or discharged directly from the ED—were captured in our dataset and categorised as either a hospital admission or ED discharge. We designated hospitals as urban or rural based on the corresponding county listed in the non-public PDD documentation.

Patient involvement

Patients were not involved in the development of the research question, outcome measures or study design. We did not actively recruit patients for this study, and the results will not be disseminated to the study participants as we used unidentified data and have no way of contacting the patients.

Statistical analysis

We analysed ED visits and visit rates using a linear regression model to test for significant linear temporal trends in California from 2005 to 2015 by age group (<5 years, 5–19 years, 20–44 years, 45–64 years and 65 years and over); sex (male, female, unknown); race/ethnicity group (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Other); payer/insurance status (private, Medicare, Medicaid, uninsured/self-pay, other, unknown) and metropolitan statistical area (rural or urban). Furthermore, we looked at age, sex, race/ethnicity, urban/rural trends by payer/insurance status for a more granular picture of patient population differences within each insurance group. We obtained International Classification of Disease, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes for principal hospital discharge diagnoses for 2005–2014 and categorised them into multilevel diagnoses codes using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Clinical Classification Software (CCS) to examine changes in conditions observed in the ED over time. We clustered 2015 primary diagnoses into multilevel CCS categories using single-level CCS categorisations provided in the data, which accounted for the transition from ICD-9 to ICD-10 coding in October 2015. We performed all analyses using Stata software (V.14, Stata, College Station, Texas, USA). The University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Results

Between 2005 and 2015, total annual ED visits in California increased by 39.7% (p<0.001), from 10.2 million to 14.2 million (online supplementary table 1). ED utilisation in California gradually increased across most years in the study period, with two pronounced jumps from 2008 to 2009 (8.1%) and 2014 to 2015 (6.3%). The number of ED visits grew the most among patients aged 45–64 (55.8%; p<0.001), female patients (42.5%; p<0.001), Hispanic patients (78.4%; p<0.001), Medicaid beneficiaries (151.0%; p=0.001) and those living in urban areas (40.5%; p<0.001).

bmjopen-2017-021392supp001.pdf (103.3KB, pdf)

After adjusting for the 9.3% population growth in California during our study period, we found an overall 27.8% (p<0.001) increase in ED visit rates between 2005 and 2015 (table 1), with significant increases among all patient characteristics examined. In 2015, ED visit rates were the highest among patients aged less than 5 and 65 and over (543 visits and 503 visits per 1000 California residents aged less than 5 and 65 and over, respectively), non-Hispanic Black patients (703 per 1000), Medicaid-insured patients (747 per 1000) and rural residents (501 per 1000). ED visit rates grew the fastest among patients aged 5–19 (37.4% increase, from 196 to 269 per 1000) and 45–64 (41.1% increase, from 101 to 142 per 1000) (p<0.001 for both)—in particular, a 232% increase among Medicaid-insured 45–64 year-olds (online supplementary table 2)—uninsured patients (36.1% increase, from 242 to 330 per 1000; p=0.002) and urban residents (28.3% increase, from 281 to 361 per 1000; p<0.001). Although non-Hispanic Black patients had a strikingly higher ED visit rate in 2015, both non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic patients experienced similar high levels of ED visit rate growth (56.8% increase, from 448 to 703 per 1000 and 48.8% increase, from 237 to 353 per 1000, respectively; p<0.001 for both) during the study period. See online supplementary tables 3–5 for additional results on ED visits stratified by insurance groups (privately insured, Medicare insured and uninsured, respectively).

Table 1.

California ED visit rates (per 1000 population), 2005–2015

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | % Change | P values | |

| Total ED visit rate | 284.3 | 282.4 | 289.0 | 294.4 | 315.3 | 309.8 | 317.3 | 326.0 | 331.1 | 344.9 | 363.5 | 27.8% | <0.001 |

| Age group | |||||||||||||

| <5 | 455.4 | 448.4 | 474.8 | 479.1 | 544.5 | 514.3 | 510.3 | 508.8 | 518.5 | 512.9 | 542.5 | 19.1% | <0.001 |

| 5–19 | 195.7 | 191.3 | 196.7 | 200.4 | 234.0 | 215.8 | 223.4 | 227.3 | 239.0 | 250.1 | 268.9 | 37.4% | <0.001 |

| 20–44 | 266.9 | 264.9 | 270.7 | 274.5 | 291.9 | 290.0 | 296.3 | 306.0 | 309.2 | 328.6 | 346.4 | 29.8% | <0.001 |

| 45–64 | 100.7 | 102.4 | 106.1 | 110.5 | 116.2 | 118.1 | 121.8 | 127.0 | 128.3 | 135.5 | 142.1 | 41.1% | <0.001 |

| 65+ | 461.0 | 464.1 | 464.0 | 470.3 | 471.5 | 474.8 | 485.9 | 490.6 | 486.6 | 486.2 | 503.0 | 9.1% | <0.001 |

| Sex | |||||||||||||

| Male | 266.4 | 264.7 | 270.1 | 273.6 | 291.7 | 285.9 | 292.5 | 300.1 | 305.1 | 317.2 | 336.0 | 26.2% | <0.001 |

| Female | 300.1 | 299.9 | 307.7 | 315.0 | 338.7 | 333.3 | 341.7 | 351.6 | 356.7 | 372.2 | 390.6 | 30.1% | <0.001 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||||||||

| NH White | 294.5 | 299.4 | 308.8 | 315.3 | 336.8 | 339.6 | 347.9 | 358.2 | 357.4 | 366.8 | 381.1 | 29.4% | <0.001 |

| NH Black | 448.2 | 469.0 | 497.7 | 524.7 | 581.5 | 593.7 | 615.1 | 642.3 | 646.9 | 675.1 | 702.9 | 56.8% | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 237.1 | 238.9 | 249.5 | 259.5 | 288.8 | 278.1 | 287.8 | 296.8 | 310.6 | 328.0 | 352.9 | 48.8% | <0.001 |

| Other | 185.3 | 191.6 | 199.8 | 199.9 | 214.7 | 211.3 | 213.6 | 215.7 | 217.6 | 230.2 | 249.2 | 34.4% | <0.001 |

| Payer | |||||||||||||

| Private | 171.0 | 166.2 | 168.9 | 174.7 | 196.9 | 180.1 | 186.5 | 181.8 | 186.1 | 184.6 | 181.4 | 6.1% | 0.012 |

| Medicaid | 580.9 | 574.7 | 596.5 | 605.6 | 611.2 | 638.0 | 623.6 | 654.1 | 645.2 | 731.6 | 747.3 | 28.6% | <0.001 |

| Medicare | 459.2 | 490.6 | 492.0 | 501.3 | 497.7 | 496.4 | 516.7 | 539.1 | 529.8 | 528.7 | 536.9 | 16.9% | <0.001 |

| Uninsured/self-pay | 242.2 | 251.5 | 263.6 | 255.8 | 249.0 | 254.4 | 253.5 | 278.9 | 293.8 | 290.8 | 329.7 | 36.1% | 0.002 |

| MSA | |||||||||||||

| Urban | 281.0 | 279.1 | 286.0 | 291.5 | 312.6 | 307.2 | 314.8 | 323.6 | 328.5 | 342.3 | 360.6 | 28.3% | <0.001 |

| Rural | 425.7 | 421.8 | 418.7 | 419.9 | 435.1 | 425.0 | 429.0 | 434.7 | 451.0 | 466.3 | 500.8 | 17.6% | 0.010 |

ED visit rate denominator includes the population of the corresponding characteristic (eg, ED visits by male patients in given year/total male population in given year in CA).

CA, California; ED, emergency department; MSA, metropolitan statistical area; NH, non-Hispanic.

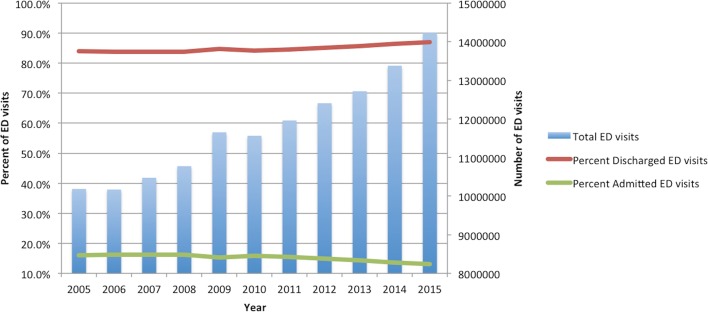

When examining ED discharge and hospital admission trends, the number of ED visits resulting in a discharge increased by 44.5%, from 8.6 million to 12.4 million and the number resulting in a hospital admission increased by 14.2%, from roughly 1.6 million to 1.9 million during the study period. The proportion of ED visits that resulted in a discharge increased by 3.5% (from 84.0% of ED visits in 2005 to 86.9% in 2015), while the proportion that resulted in a hospital admission decreased by 18.3% (from 16.0% of ED visits in 2005 to 13.1% in 2015; figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proportion of California ED visits resulting in admission versus discharge, 2005–2015. Source: Authors’ analysis of Emergency Discharge Data and Patient Discharge Data from the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, 2005–2015. ED, emergency department.

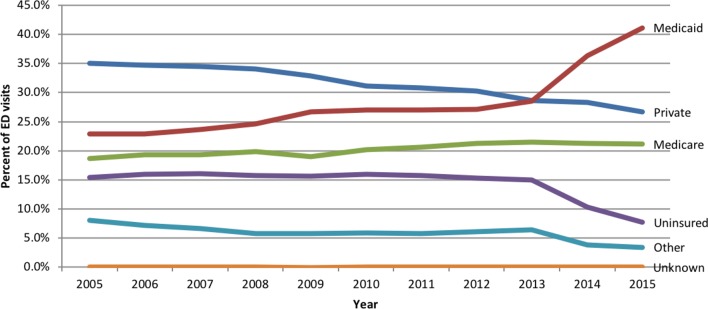

ED visit patient composition trends by payer

Although ED visit rates increased across all payer groups, the proportion of ED visits from private and uninsured patients decreased by 24.0% (from 35.0% to 26.6%) and 50.1% (from 15.4% to 7.7%), respectively, while the proportion of ED visits from Medicare-insured and Medicaid-insured patients increased by 13.1% (from 18.7% to 21.1%) and 79.7% (from 22.9% to 41.1%), respectively, during the study period (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Proportion of California ED visits by payer, 2005–2015. Source: Authors’ analysis of Emergency Discharge Data and Patient Discharge Data from the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, 2005–2015. ED, emergency department.

We further examined payer composition trends by looking at ED visits resulting in a hospital admission. The number of ED visits resulting in hospitalisation grew for Medicaid-insured and Medicare-insured patients by 72.0% and 18.5%, respectively, but declined for privately insured and uninsured patients by 8.3% and 71.3%, respectively. However, we found that the proportion of all ED visits resulting in hospitalisation reduced across all payer groups, with decreases of 13.6% for the privately insured, 31.4% for the Medicaid-insured, 25.0% for the Medicare-insured and 58.8% for the uninsured.

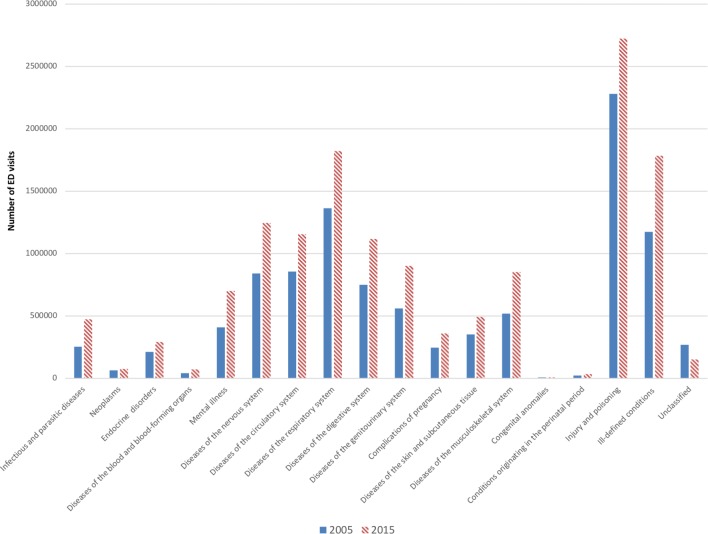

ED visit trends by CCS diagnoses

When we analysed ED visits by multilevel CCS diagnosis groups, we found that the number of ED visits increased across all CCS diagnoses except for the unclassified conditions group (figure 3). The top three conditions for which ED visits grew the most included infectious and parasitic diseases (88.2%), diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs (78.7%) and mental illness (70.8%). However, the top three most prevalent conditions during the study period were injury and poisoning (20.6%), diseases of the respiratory system (12.8%) and ill-defined conditions (12.5%).

Figure 3.

California ED visits by diagnosis, 2005 and 2015. Source: Authors’ analysis of Emergency Discharge Data from the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, 2005 and 2015. ED, emergency department.

Discussion

Between 2005 and 2015, ED visit rates increased by 27.8% in California, with the greatest ED visit rate growth among patients aged 5–19 and 45–64 years old, uninsured and Medicaid-insured patients, non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic patients and patients living in urban areas. Despite relatively slower ED visit rate growth trends, the youngest (less than 5 years) and elderly (65 and over) patient groups as well as Medicare-insured patients retained high ED visit rates throughout the study period.

Our findings are consistent with previous studies8 10 15 and suggest that healthcare needs tend to exist across the entire age spectrum, although for a range of reasons. Patients aged less than 5 had the highest ED utilisation rate as of 2015, outpacing the ED utilisation rate for patients 65 and over. This finding, along with the high ED visit rate growth for patients aged 5–19, potentially suggests a need for coordinated acute care for the paediatric population as well as the need to re-examine the availability and role of EDs equipped to treat children, particularly among underinsured paediatric patients. On the other hand, while patients aged 45–64 had the lowest overall ED visit rate during the study period, this group experienced the greatest ED utilisation rate increase. This suggests that patients nearing 65 may have significant healthcare needs given prior evidence of sharp increases in healthcare utilisation once patients turned 65 years old.26 Meanwhile, patients aged 65 and over retained high steady ED visit rates.27 The consistent high ED utilisation rates and current trends in providers who refer elderly patients to the ED28 29 suggests a need for improving geriatric care at a systemic level to treat elderly patients effectively and in a timely manner.

Our results revealed that ED utilisation rates grew the fastest among non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic patients. Although we found similar ED visit rates between non-Hispanic White and Hispanic patients, it is possible that the observed number of ED visits by Hispanic patients is overall lower because this demographic may be more likely to avoid visiting the ED for reasons such as language barriers, fear of deportation and other cultural factors.30 These trends may point to substantial gaps in the healthcare system, specifically for racial/ethnic minorities. They may also suggest that although healthcare access has increased to some extent, disparities still exist31 as EDs, acting as ‘safety nets,’ continue to provide increasingly more care.

Prior studies have reported high ED utilisation rates among Medicaid-insured and uninsured patients,8 10 32 consistent with our findings of large ED visit rate increases in these payer groups. Our findings could reflect a number of trends. First, the use of EDs as ‘safety nets’ has been previously reported,33 with one study reporting that more than 50% of all acute visits by uninsured patients were to emergency physicians, who comprise less than 5% of all physicians in the US.34 Second, difficulty in accessing primary care has been widely cited as a potential source for the increasing trends of ED use by Medicaid-insured patients.5 32 Despite initiatives such as the ACA—designed to provide low-income individuals with healthcare access—Medicaid-insured patients increasingly seek care in the ED as a result of untimely access to primary and specialty care.9 The high use of EDs by Medicaid-insured patients has been largely attributed to the reluctance of many primary care providers to accept Medicaid insurance due to low reimbursement rates.5 35 At the same time, however, increasing literature shows that even patients with adequate primary care access are often referred to the ED by their primary care physicians,14 suggesting that physicians themselves are also relying on the emergency care system to help diagnose and manage patients. Last, the utilisation of EDs over other ambulatory care venues by patients of low socioeconomic status is influenced by insurance status or affordability and by accessibility, availability, perceptions of accommodation and high disease burden.36 37 These factors are important to consider when exploring potential solutions to improve the accessibility, provision and quality of care.

Despite increasing numbers of ED visits, the proportion of ED visits resulting in inpatient admissions decreased. Prior studies have indicated that high numbers of complex and urgent patients are being managed in EDs,38 39 and the decreases in the proportion of admissions seen in our study could indicate that patients with complex conditions are being evaluated, treated and discharged from the ED rather than being admitted or cared for elsewhere. Although this has potential benefits to healthcare systems, management of high-acuity outpatients in the ED could further contribute to the demands on EDs.

Other changes in ED visit trends included decreases in the proportion of ED visits for conditions related to injury and poisoning and increases in the proportion of medical conditions, including infectious and parasitic diseases and mental illness. Consistent with prior evidence of a decrease in ED visit rates for injuries in California from 2005 to 2011 but an increase for non-injury diagnoses,40 our findings reveal the changing role of the ED in the healthcare system, where EDs are treating and providing care for more complex medical conditions. As chronic illnesses increase in the USA41 and the management of these conditions becomes more complex, it will become critical to expand services and access to treatments for conditions that drive ED utilisation and demand for emergency care.

Limitations

Our study includes several limitations. First, OSHPD collects retrospective, self-reported data from hospitals, which could introduce potential reporting errors or missing data; however, hospitals submit routine accuracy checks using OSHPD’s Medical Information Reporting for California (MIRCal) online system, which reduces such errors. Second, our data are limited to California residents and may limit the generalisability and applicability of our results on a national or global level, despite California’s diverse and high Medicaid-insured population. Third, US Census Bureau surveys exclude undocumented and homeless populations as well as individuals residing in nursing homes, extended-care facilities, prisons and mental health facilities. Many of these individuals visit the ED on a frequent basis and thus ED visit rates could be overestimated because many of these people are not accounted for in the population denominator.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that the demand for emergency care continues to rise. ED visit rates in California increased from 2005 to 2015, across all age groups, and particularly among the uninsured, Medicaid-insured, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic and urban-residing patients. Increased ED visit rates by Medicaid-insured and uninsured patients may reflect current limitations in accessing care in other parts of the healthcare system. Furthermore, changes in conditions seen in the ED suggest that patient healthcare needs are becoming increasingly great and complex. Rather than focusing solely on efforts to reduce ED use, policymakers may need to recognise that EDs are playing an increasingly vital role in the provision of care and consider ways to incorporate this changing reality into the delivery of health services.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development for their assistance in preparing the datasets used in this project.

Footnotes

Contributors: RYH and MJN contributed to the conception and design of the study. SHS and TJN drafted the manuscript. MJN and JG contributed to the analysis of data. RYH provided supervision. RYH, SHS, JG, TJN and MJN contributed to the interpretation of the data and critically reviewed, revised and approved the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the California Health Care Foundation.

Disclaimer: The sponsor had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data are available through the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development.

References

- 1. EMTALA. Emergency medical treatment and active labor act of 1985, 1986. Pub L No. 99-272, 42 USC §1395dd. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. American Hospital Association. Trendwatch chartbook 2016: trends affecting hospitals and health systems. Table 3.3: emergency department visits, emergency department visits per 1,000 persons, and number of emergency departments, 1994-2014, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Skinner HG, Blanchard J, Elixhauser A. Trends in emergency department visits, 2006-2011. HCUP Statistical Brief #179. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2014. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb179-Emergency-Department-Trends.pdf (accessed 06 Dec 2017). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Emergency Physicians: Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield policy violates federal law [press release]. Washington: PRNewswire-USNewswire, 2017. http://newsroom.acep.org/2017-05-16-Emergency-Physicians-Anthem-Blue-Cross-Blue-Shield-Policy-Violates-Federal-Law (accessed 06 Dec 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kellermann AL, Weinick RM. Emergency departments, Medicaid costs, and access to primary care-understanding the link. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2141–3. 10.1056/NEJMp1203247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Friedman AB, Saloner B, Hsia RY. No Place to Call Home–Policies to Reduce ED Use in Medicaid. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2382–5. 10.1056/NEJMp1502627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Flores-Mateo G, Violan-Fors C, Carrillo-Santisteve P, et al. . Effectiveness of organizational interventions to reduce emergency department utilization: a systematic review. PLoS One 2012;7:e35903 10.1371/journal.pone.0035903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Taubman SL, Allen HL, Wright BJ, et al. . Medicaid increases emergency-department use: evidence from Oregon’s Health Insurance Experiment. Science 2014;343:263–8. 10.1126/science.1246183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. American College of Emergency Physicians. ER visits continue to rise since implementation of Affordable Care Act. 2015. http://newsroom.acep.org/2015-05-04-ER-Visits-Continue-to-Rise-Since-Implementation-of-Affordable-Care-Act (accessed 06 Dec 2017).

- 10. McConville S, Lee H. Emergency department care in California: who uses it and why? 10 San Francisco, CA: The Public Policy Institute of California, 2008. http://www.ppic.org/publication/emergency-department-care-in-california-who-uses-it-and-why/ (accessed 06 Dec 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 11. HCUP Fast Stats, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. California: All ED visits (adults and pediatric) by expected payer. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2017. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/faststats/StatePayerEDServlet?state1=CA (accessed 06 Dec 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 12. Garthwaite C, Gross T, Notowidigdo M, et al. . Insurance expansion and hospital emergency department access: evidence from the affordable care act. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:172–9. 10.7326/M16-0086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sommers BD, Blendon RJ, Orav EJ, et al. . Changes in utilization and health among low-income adults after medicaid expansion or expanded private insurance. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:1501–9. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.4419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Finkelstein AN, Taubman SL, Allen HL, et al. . Effect of medicaid coverage on ED use - further evidence from oregon’s experiment. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1505–7. 10.1056/NEJMp1609533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Barakat MT, Mithal A, Huang RJ, et al. . Affordable Care Act and healthcare delivery: A comparison of California and Florida hospitals and emergency departments. PLoS One 2017;12:e0182346 10.1371/journal.pone.0182346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sommers BD, Simon K. Health Insurance and Emergency Department Use - A Complex Relationship. N Engl J Med 2017;376:1708–11. 10.1056/NEJMp1614378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. The California health care landscape. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2015. http://kff.org/health-reform/fact-sheet/the-california-health-care-landscape/ (accessed 01 Mar 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hospital Annual Financial Data 2005-2015. California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development. 2016. http://www.oshpd.ca.gov/hid/Products/Hospitals/AnnFinanData/SubSets/SelectedData/default.asp (accessed 01 Sep 2016).

- 19. Hospital Annual Utilization Data 2005-2015. California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development. 2016. https://www.oshpd.ca.gov/HID/Hospital-Utilization.html (accessed 01 Sept 2016).

- 20. Table 2. Intercensal estimates of the resident population by sex and age for California: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2010. U.S: Census Bureau, Population Division, 2012. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/intercensal-2000-2010-state.html (accessed 06 Dec 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 21. Annual estimates of the resident population for selected age groups by sex for the United States, states, counties and Puerto Rico Commonwealth and Municipios: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015. U.S: Census Bureau, Population Division, 2016. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk (accessed 06 Dec 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 22. Health insurance coverage status and type of coverage by state and age for all people: 2005-2011. U.S: Census Bureau; Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement, 2006-2012 https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/cps-hi.html (accessed 06 Dec 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 23. Health insurance coverage status and type of coverage by state and age for all people: 2013-2015. U.S: Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2013-2015. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/health-insurance/acs-hi.2015.html (accessed 06 Dec 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 24. Race/ethnic population with age and sex detail, 2000-2010. State of California: Department of Finance, 2012. http://www.dof.ca.gov/Forecasting/Demographics/Estimates/Race-Ethnic/2000-2010/ (accessed 06 Dec 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 25. Annual estimates of the resident population by sex, age, race, and Hispanic origin for the United States and States: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015. U.S: Census Bureau, Population Division, 2016. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk (accessed 06 Dec 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 26. Card D, Dobkin C, Maestas N. The impact of nearly universal insurance coverage on health care utilization: evidence from medicare. Am Econ Rev 2008;98:2242–58. 10.1257/aer.98.5.2242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Samaras N, Chevalley T, Samaras D, et al. . Older patients in the emergency department: a review. Ann Emerg Med 2010;56:261–9. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Greenwald PW, Estevez RM, Clark S, et al. . The ED as the primary source of hospital admission for older (but not younger) adults. Am J Emerg Med 2016;34:943–7. 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.05.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schuur JD, Venkatesh AK. The growing role of emergency departments in hospital admissions. N Engl J Med 2012;367:391–3. 10.1056/NEJMp1204431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pérez-Escamilla R, Garcia J, Song D. HEALTH CARE ACCESS AMONG HISPANIC IMMIGRANTS: ¿ALGUIEN ESTÁ ESCUCHANDO? [IS ANYBODY LISTENING?]. NAPA Bull 2010;34:47–67. 10.1111/j.1556-4797.2010.01051.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Artiga S, Young K, Garfield R, et al. . Racial and ethnic disparities in access to and utilization of care among insured adults: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2015. https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/racial-and-ethnic-disparities-in-access-to-and-utilization-of-care-among-insured-adults/ (accessed 06 Dec 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hsia RY, Brownell J, Wilson S, et al. . Trends in adult emergency department visits in California by insurance status, 2005-2010. JAMA 2013;310:1181–3. 10.1001/jama.2013.228331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Burt CW, Arispe IE. Characteristics of emergency departments serving high volumes of safety-net patients: United States, 2000. Vital Health Stat 13 2004;13:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pitts SR, Carrier ER, Rich EC, et al. . Where Americans get acute care: increasingly, it’s not at their doctor’s office. Health Aff 2010;29:1620–9. 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Decker SL. In 2011, nearly one-third of physicians said they would not accept new Mediciad patients, but rising fees may help. Health Aff 2012;31:1673–9. 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kangovi S, Barg FK, Carter T, et al. . Understanding why patients of low socioeconomic status prefer hospitals over ambulatory care. Health Aff 2013;32:1196–203. 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hudon C, Sanche S, Haggerty JL. Personal Characteristics and Experience of Primary Care Predicting Frequent Use of Emergency Department: A Prospective Cohort Study. PLoS One 2016;11:e0157489 10.1371/journal.pone.0157489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Herring AA, Johnson B, Ginde AA, et al. . High-intensity emergency department visits increased in California, 2002-09. Health Aff 2013;32:1811–9. 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Burke LG, Wild RC, Orav EJ, et al. . Are trends in billing for high-intensity emergency care explained by changes in services provided in the emergency department? An observational study among US Medicare beneficiaries. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019357 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hsia RY, Nath JB, Baker LC. California emergency department visit rates for medical conditions increased while visit rates for injuries fell, 2005-11. Health Aff 2015;34:621–6. 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. General health status: chronic disease prevalence. 2016. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/about/foundation-health-measures/General-Health-Status#chronic (accessed 06 Dec 2017).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-021392supp001.pdf (103.3KB, pdf)