Abstract

Objectives

To illuminate the association between interferon-based therapy (IBT) and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in patients infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV).

Design, setting, participants and interventions

This retrospective cohort study used Taiwan’s Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2005 that included 18 971 patients with HCV infection between 1 January 1997 and 31 December 2012. We identified 1966 patients with HCV infection who received IBT (treated cohort) and used 1:4 propensity score-matching to select 7864 counterpart controls who did not receive IBT (untreated cohort).

Outcome measures

All study participants were followed until the end of 2012 to calculate the incidence rate and risk of incident RA.

Results

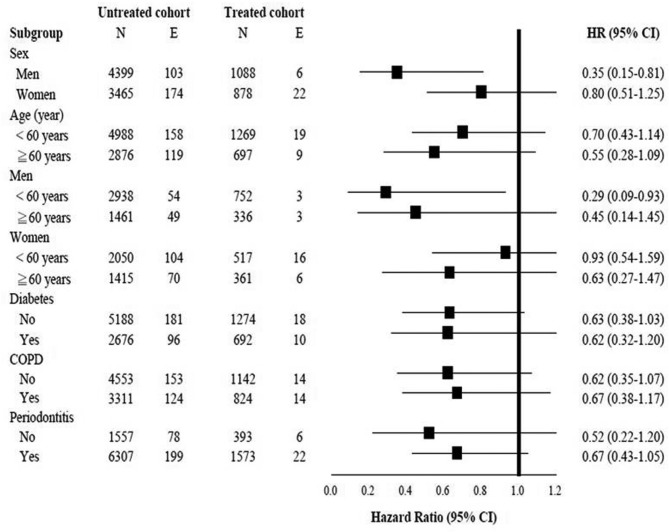

During the study period, 305 RA events (3.1%) occurred. The incidence rate of RA was significantly lower in the treated cohort than the untreated cohort (4.0 compared with 5.5 per 1000 person-years, p<0.018), and the adjusted HR remained significant at 0.63 (95% CI 0.43 to 0.94, p=0.023) in a Cox proportional hazards regression model. Multivariate stratified analyses revealed that the attenuation in RA risk was greater in men (0.35; 0.15 to 0.81, p=0.014) and men<60 years (0.29; 0.09 to 0.93, p=0.036).

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that IBT may reduce the risk of RA and contributes to growing evidence that HCV infection may lead to development of RA.

Keywords: HCV infection, interferon-based therapy, rheumatoid arthritis, cohort study

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study estimated the association between interferon-based therapy (IBT) for hepatitis C virus infection and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) risk using a national database covering more than 99% of the Taiwanese population.

This study used a propensity score matching to reduce the confounding effects.

The RA diagnosis code in the Registry of Catastrophic Illness Patient Database has been validated.

The main limitation of the current study is that laboratory data (eg, viral load, sustained virological response) and RA severity are not available.

Caution is advised before directly applying our results to the West because of relatively lower antiviral efficacy of IBT in the West than in Taiwan and Asian countries.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory and autoimmune disease with a prevalence of 57.7–99.6 per 100 000 persons in Taiwan.1 2 RA affects the peripheral joints and extra-articular organ systems and can cause joint deformity, cardiovascular morbidity and disability if untreated. The exact cause(s) of RA is unknown. However, previous research indicates that genetic factors and environment factors, including hormones, infection, diabetes and smoking, may promote the development of RA.3–6

Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection can induce an antiviral immune response in the host. Previous research indicates that 2%–38% of patients with HCV infection have rheumatological symptoms.7 Many extrahepatic features of HCV infection, including arthralgia, myalgia, sicca, cryoglobulinemia and polyarteritis nodosa, are associated with the B cell lymphoproliferative response after HCV infection.8 Besides, the serum of patients with HCV infection often has evidence of production of abnormal autoantibodies, including rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody.9 10 A previous population-based Taiwanese study reported that HCV infection was associated with development of RA.11

Although interferon-free regimens composed of direct acting antiviral agents are now becoming a new paradigm,12 interferon-based therapy (IBT) plus ribavirin has been widely used as the regimen of choice for a decade and achieves an eradication rate over 70% among treatment-naïve patients in Taiwan and creates excellent therapeutic responses in Asian countries where interleukin-28B genotypic polymorphism is prevalent.13–15 However, IBT can exacerbate disease activity in patients with HCV with a concurrent rheumatic disease, such as RA or psoriasis.16 17 Furthermore, autoimmune side effects may occur during IBT, ranging from asymptomatic formation of autoantibodies to development of autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, autoimmune thyroiditis, psoriasis and autoimmune thrombocytopaenia.18 19 However, IBT reduces the autoimmune response in patients with HCV infection with concurrent cryoglobulinemia.20 IBT also alleviates the symptoms of HCV-related arthritis, which may be associated with the HCV immune response.21 22 Some case reports suggest that RA can develop during or after IBT for HCV infection.16 18 23–25

There has been no clear evidence to address the effect of IBT on the risk of RA in patients with HCV infection, and it is uncertain if IBT has different effects on different subsets of patients with HCV infection on the risk of RA. Taiwan is an endemic area of HCV infection and an ideal research hub for this relationship. Hence, we used reimbursement claims data from the Taiwan Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2005 (LHID2005) to elucidate the association between IBT for HCV and risk of RA during a follow-up period of 16 years.

Patients and methods

Data source

This is a retrospective cohort study based on the LHID2005, a subset of the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD). The NHIRD and LHID2005 have been described in detail in our previous research.26–29 In brief, Taiwan National Health Insurance (NHI) programme launched in 1995 is a single-payer compulsory programme that contains various types of healthcare for all residents in Taiwan. Thus, the NHIRD is a comprehensive healthcare database that is freely accessible for academic purpose after deidentification of all personal information by National Health Research Institute. The present study did not require informed consent. In the NHIRD, disease is coded according to ICD-9. The coding accuracy for major diseases, such as viral hepatitis and RA, has been validated in previous research.4 5 11 13 15 26–32

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved in this study because permanent deidentification of patient information in the NHIRD was conducted by the National Health Research Institute before data analysis and the NHIRD was freely available for academic research.

Study sample

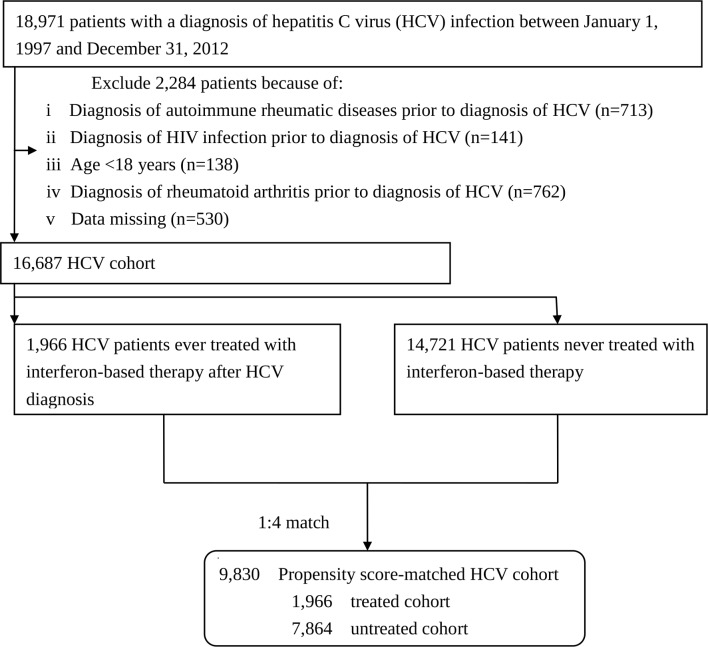

From the outpatient and inpatient datasets of the LHID2005, we identified 18 971 patients infected with HCV (ICD-9-CM codes 070.41, 070.44, 070.51, 070.54, V02.62)27 from 1 January 1997 to 31 December 2012 (figure 1). We excluded 2284 patients who were younger than 18 years old or were diagnosed with RA (ICD-9 code 714.0), some autoimmune rheumatic diseases (ICD-9 codes 710.0, 710.2, 710.1, 710.3, 710.4, 446.0–446.7, 136.1) or HIV (ICD-9 codes 042, 043, 044, V08, 795.8) prior to the diagnosis of HCV. We also excluded patients who received IBT after a diagnosis of RA or had data missing. Finally, a total of 16 687 patients with HCV infection were enrolled.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the enrolment process. One treated patient with HCV infection was matched with four untreated patients with HCV infection according to a propensity score that was estimated by logistic regression built on age, sex and comorbidities.

This HCV cohort was divided into a treated cohort (patients who used IBT, namely, interferon alpha, pegylated interferon alpha-2a or pegylated interferon alpha-2b alone or in combination with ribavirin)30 and an untreated (control) cohort. The NHI Administration has been reimbursing the 6 months of use of IBT for treatment of all HCV genotypes since 1 October 2003.30 Most subjects with HCV infection (97.8%) were prescribed combination regimen with IBT and ribavirin. The index date of follow-up was the first date of IBT prescription for the treated cohort. Patients with HCV infection who never received IBT during the study period was defined as the untreated cohort (n=14 721). The treated patient was matched with four untreated counterparts according to a propensity score that adjusted for baseline differences between the treated and untreated cohorts. Propensity scores were calculated using multivariable logistic regression to estimate the probability of treatment. Age, sex and comorbidities were included in the propensity score model. Furthermore, the untreated controls were intentionally matched for the time period elapsing from HCV diagnosis to IBT prescription in treated patients so as to reduce the immortal time bias.31 Finally, the treated and untreated cohorts included 1966 and 7864 patients with HCV infection, respectively.

Main outcome measurement

The treated cohort was followed after starting IBT, whereas the untreated cohort after the matched date. All study participants were observed for the occurrence of RA, withdrawal from the insurance system or the end of 2012, whichever date came first. RA is one of statutory major diseases in Taiwan and only subjects who fulfil the diagnostic criteria of RA are issued a catastrophic illness certificate that grants exemption from copayment for healthcare. This issuance was validated by at least two rheumatologists after rigorous review of clinical data. Thus, the diagnostic accuracy of RA is reliable. In the present study, all RA cases were identified from the Registry of Catastrophic Illness Patient Database, a part of the NHIRD.

Covariate assessment

We included some comorbidities (ICD-9 codes) associated with RA, including diabetes (250),5 periodontitis (523.3, 523.4, 523.5)4 and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (490-496) as a proxy for cigarette smoking.6 Additional covariates included were geographic region (northern, central, eastern, southern Taiwan), urbanisation level (urban, suburban and rural), enrolee category (EC) (1 (highest status) to 4 (lowest status)), number of medical visits and Deyo-Charlson comorbidity index. Geographic region and number of medical visits were adjusted to reduce potential confounding of differential accessibility and availability of medical care and urbanisation level and EC as socioeconomic measures to reduce environmental effects.26 In the NHIRD, EC was classified as four subgroups: EC1 (highest socioeconomic status, eg, civil servants, full-time or regularly paid personnel in governmental agencies and public schools), EC2 (employees of privately owned enterprises or institutions), EC3 (self-employed, other employees or paid personnel and members of the farmers or fishers associations) or EC4 (lowest socioeconomic status, eg. substitute service draftees, members of low-income families and veterans).33

Statistical analysis

Sociodemographic data were compared between the treated and untreated cohorts. The incidence rates (per 1000 person-years) with 95% CIs of RA in both cohorts were analysed. The cumulative incidence of RA was estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method, with statistical significance examined by the log-rank test. After confirming the assumption of proportional hazards, we applied a Cox proportional hazard regression model32 to evaluate the association between IBT and RA risk, with adjustment for all covariates (age per year, sex, comorbidities, geographic region, urbanisation level, EC, number of medical visits and Charlson comorbidity index). The impact of IBT on RA risk was further investigated in different strata according to age, sex and comorbidities. We analysed all data with SAS (V.9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA) and SPSS (V.20.0; IBM, New York City, New York, USA) and considered a 2-sided p value less than 0.05 as statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the propensity score-matched patients with HCV

The treated cohort had a mean (±SD) duration of IBT of 0.6±1.0 years (table 1). There were no significant differences between the treated and untreated cohorts in age, sex, comorbidities, geographic region and urbanisation level. The treated cohort had a higher percentage of EC 1 and 3, number of medical visits and Charlson comorbidity index.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics in the propensity score-matched HCV cohort in Taiwan, 1997–2012 (n=9830)

| Variable | Treated cohort (n=1966), N (%) |

Untreated cohort (n=7864), N (%) |

P values | ||

| Sex | 0.63 | ||||

| Men | 1088 | 55.3 | 4399 | 55.9 | |

| Women | 878 | 44.7 | 3465 | 41.1 | |

| Age (pear year) | 54.7±11.2 | 54.5±12.6 | 0.56 | ||

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Diabetes | 692 | 35.2 | 2676 | 34.0 | 0.33 |

| COPD | 824 | 41.9 | 3311 | 42.1 | 0.88 |

| Periodontitis | 1573 | 80.0 | 6307 | 80.2 | 0.85 |

| Geographic region | 0.43 | ||||

| Northern | 554 | 31.3 | 2475 | 31.5 | |

| Central | 12 413 | 28.2 | 2325 | 29.5 | |

| Eastern | 62 | 3.1 | 212 | 2.7 | |

| Southern | 735 | 37.4 | 2852 | 36.3 | |

| Urbanisation level | 0.32 | ||||

| Urban | 498 | 25.3 | 1871 | 23.8 | |

| Suburban | 853 | 43.4 | 3440 | 43.7 | |

| Rural | 615 | 31.3 | 2553 | 32.5 | |

| Enrolee category | 0.003 | ||||

| 1 | 698 | 35.5 | 2616 | 33.3 | |

| 2 | 29 | 1.5 | 144 | 1.8 | |

| 3 | 968 | 49.2 | 3767 | 47.9 | |

| 4 | 271 | 13.8 | 1337 | 17.0 | |

| Number of medical visits | 29.3±20.8 | 26.9±23.5 | <0.0001 | ||

| Charlson comorbidity index | 3.2±2.1 | 2.7±2.3 | <0.0001 | ||

Categorical variables given as number (percentage); continuous variable as mean±SD.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Comparisons of RA incidence rates between the treated and untreated cohorts

During the mean follow-up of 5.8±3.9 years, 305 patients (3.1%) developed RA, with 28 (1.4%) and 277 (3.5%) in the treated and untreated cohorts, respectively (table 2). By the end of follow-up, the incidence rate of RA was 4.0/1000 person-years (95% CI 2.63 to 2.87) for the treated cohort and 5.5/1000 person-years (95% CI 2.33 to 2.88) for the untreated cohort. The Kaplan-Meier estimate revealed that the cumulative incidence of RA was significantly lower in the treated cohort than in the untreated cohort (log rank p=0.018; figure 2).

Table 2.

Incidence rate (per 1000 person-years) of incident RA in the propensity score-matched HCV cohort

| RA event (%) | Number of patients | Person-years | Incidence rate | |

| Treated cohort | 28 (1.4) | 1966 | 6928 | 4.0 |

| Untreated cohort | 277 (3.5) | 7864 | 50 259 | 5.5 |

HCV, hepatitis C virus; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of RA estimated by the Kaplan-Meier approach in treated (red line) and untreated (blue line) propensity score-matched HCV-infected cohorts during the 16-year follow-up period. The treated cohort had a lower incidence rate than the untreated cohort (Log-rank test, p=0.018). HCV, hepatitis C virus; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

Risk factors for RA in the propensity score-matched patients with HCV

The risk of RA was significantly lower in the treated cohort (adjusted HR (aHR), 0.63; 95% CI 0.43 to 0.94, p=0.023) and males (aHR, 0.49; 95% CI 0.38 to 0.62, p<0.001) and higher in old age (1.01; 1.00 to 1.02, p=0.013), residence in eastern Taiwan (2.05; 1.14 to 3.67, p=0.016), and more number of medical visits (1.01; 1.00 to 1.01, p=0.005) (table 3).

Table 3.

HRs for rheumatoid arthritis in the propensity score-matched HCV cohort

| Variable | Crude | Adjusted* | ||||

| HR | 95% CI | P values | HR | 95% CI | P values | |

| HCV cohort | ||||||

| Untreated | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||

| Treated with IBT | 0.63 | 0.42 to 0.93 | 0.019 | 0.63 | 0.43 to 0.94 | 0.023 |

| Sex (men/women) | 0.45 | 0.36 to 0.57 | <0.001 | 0.49 | 0.38 to 0.62 | <0.001 |

| Age (per year) | 1.02 | 1.01 to 1.03 | <0.001 | 1.01 | 1.00 to 1.02 | 0.013 |

| Comorbidities (yes/no) | ||||||

| Diabetes | 1.20 | 0.95 to 1.52 | 0.13 | 1.03 | 0.79 to 1.36 | 0.81 |

| COPD | 1.37 | 1.09 to 1.72 | 0.006 | 1.18 | 0.92 to 1.52 | 0.20 |

| Periodontitis | 0.80 | 0.62 to 1.02 | 0.08 | 0.79 | 0.61 to 1.02 | 0.07 |

| Geographic region | ||||||

| Northern | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||

| Central | 1.34 | 1.00 to 1.78 | 0.048 | 1.36 | 0.98 to 1.88 | 0.07 |

| Eastern | 2.19 | 1.26 to 3.79 | 0.005 | 2.05 | 1.14 to 3.67 | 0.016 |

| Southern | 1.04 | 0.78 to 1.39 | 0.77 | 1.01 | 0.74 to 1.38 | 0.95 |

| Urbanisation level | ||||||

| Urban | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||

| Suburban | 1.11 | 0.83 to 1.49 | 0.49 | 0.10 | 0.73 to 1.37 | 0.98 |

| Rural | 1.20 | 0.88 to 1.64 | 0.24 | 0.96 | 0.67 to 1.39 | 0.83 |

| Enrolee category | ||||||

| 1 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||

| 2 | 1.11 | 0.48 to 2.52 | 0.81 | 0.71 | 0.39 to 1.29 | 0.26 |

| 3 | 1.14 | 0.88 to 1.47 | 0.33 | 0.90 | 0.60 to 1.32 | 0.60 |

| 4 | 1.32 | 0.95 to 1.84 | 0.10 | 1.07 | 0.77 to 1.50 | 0.68 |

| Number of medical visits | 1.01 | 1.01 to 1.01 | <0.0001 | 1.01 | 1.00 to 1.01 | 0.005 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 1.06 | 1.00 to 1.11 | 0.033 | 0.99 | 0.92 to 1.06 | 0.77 |

*Adjusted for age per year, sex, comorbidities, geographic region, urbanisation level, enrolee category, number of medical visits and Charlson comorbidity index.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HCV, hepatitis C virus; IBT, interferon-based therapy.

Multivariate stratified analyses

The treated cohort also had a reduced risk of RA in all stratified analyses, especially greater risk reduction in men (0.35; 0.15 to 0.81, p=0.014) and men<60 years (0.29; 0.09 to 0.93, p=0.036) (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Multivariate stratified analyses for the association between interferon-based therapy and RA in the propensity score-matched HCV cohort. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HCV, hepatitis C virus; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

Discussion

To date, this is the first large longitudinal cohort study to demonstrate a decreased risk for RA in patients with HCV infection who received IBT. More specifically, after propensity score matching and adjustment for potential confounders, we found that IBT for HCV infection was associated with a 37% reduced risk of RA over 16 years and the associations between IBT and risk reduction of RA remained significant in HCV-infected men and those aged <60 years. These findings imply that HCV infection may play a pathogenetic role in the development of RA and that treatment of HCV infection decreases this risk.

IBT can diminish or even cure HCV infection.34 IBT provides a sustained virological response (SVR) in 40%–50% of patients with HCV genotype 1 and in 70%–80% of patients with HCV genotypes 2 and 3.35–37 However, interferons are pleiotropic cytokines, with both immunomodulatory and proinflammatory effects.19 A previous study reports that IBT increased MHC class I expression and may increase self-antigen presentation.38 IBT can also increase production of B-cell activating factor, leading to increased B-cell proliferation and subsequent autoantibody formation.39 This autoimmune response may develop de novo or as a flare-up from a preclinical condition, but frequently resolves after discontinuation of treatment. Previous case studies reported that RA appeared during and after IBT.16 18 23 25 However, interferon also increased expression of the anti-inflammatory molecules, interleukin-1 receptor antagonist and soluble TNF receptor.40 A previous study reported effective treatment of RA with an IBT.41 Therefore, IBT may have two effects on RA. First, as demonstrated here, IBT may directly decrease the risk of RA development in patients with HCV infection; second, IBT may promote HCV clearance and thereby decrease the chronic antiviral immune response and the probability of an autoimmune response.

The details of the pathogenesis of RA are unclear, but there is some indication that viruses can play a role. HCV is a chronic viral infection that has hepatotrophic and lymphotrophic effects. In particular, HCV can cause chronic immune activation, lymphoproliferation and immune complex formation in the host. The host may also develop an abnormal defensive immune response. Development of autoimmune diseases such as RA, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjogren syndrome and polyarteritis nodosa can occur in patients with HCV infection.42–44 A nationwide cohort study reported that HCV infection was significantly associated with RA development.11 However, this raises a concern whether antiviral treatment for HCV can reduce this RA risk. Our results demonstrated that treatment of HCV with IBT decreases the development of RA in susceptible individuals. Therefore, eradication of HCV infection may decrease the risk of RA. The new HCV eradication therapy without the use of interferon may be used to further confirm this hypothesis.

Our results are concordant with previous studies which reported that patients with female gender and older age in Taiwan had a greater risk of RA.1 However, in contrast to previous studies, we found no significant associations of smoking, periodontitis and diabetes with risk of RA.4–6 This apparent inconsistency may be because we examined patients with HCV, whereas the previous studies examined general populations. Differences in the race, geographic distribution and medical accessibility of the study populations as well as the duration of the investigations might also have contributed to this discrepancy. Besides, previous research showed that the risk of developing RA associated with HCV infection was higher in men than in women11 and that IBT had better SVR of HCV eradication in younger age.35 This may account for our results that male patients with HCV infection and those <60 years were more likely to benefit from IBT.

The study has several strengths. We used a highly representative sample with random sampling to reduce selection bias. We also examined the use of medical services to reduce detection bias and socioeconomic indicators to reduce environmental effects.26 Besides, the study population was well-defined and well-followed because of complete nationwide coverage. Hence, our finding that IBT decreases the risk of RA in patients with HCV infection in Taiwan is robust.

The study also has some potential limitations. First, although the NHIRD does not document adverse reactions and compliance with IBT, overuse of IBT is impossible because Taiwan places strict regulations on IBT prescription. Second, miscoding errors in administrative data are inevitable. However, a strict audit and penalty system has been established in order to ensure the accuracy of all claims.45 Claims-based diagnoses of RA and HCV have been applied in prior NHIRD-based research.4 5 11 13 15 26–32 Although RA shares similar feature of arthralgia with HCV infection, there is less concern about the diagnostic accuracy of RA in Taiwan. A catastrophic illness certificate for RA will be issued after the strict review of patients’ medical charts, laboratory data (eg, anticyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibody) and X-ray images by at least two qualified rheumatologists.4 5 11 Thus, patients with RA selected in the Registry of Catastrophic Illness Patient Database meet the American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for RA. Third, with high specificity (88%–98%) and moderate to high sensitivity (79%–82.1%), anti-CCP antibody test has a significant role in confirming the diagnosis of RA and is widely used as a routine laboratory test in Taiwanese population before issuing catastrophic illness certificates for RA.46–48 However, anti-CCP data were not available from the NHIRD and we failed to calculate the percentage of patients with RA tested positive for anti-CCP antibodies in the present study. Nevertheless, previous research reported that 79.5%–82.1% of patients with RA in Taiwan tested positive for anti-CCP.47 48 Although HCV-induced inflammatory arthritis can present as polyarticular, symmetrical arthritis and positive rheumatoid factor, which mimic RA or meet the diagnosis of RA, it is generally less aggressive, non-nodular, non-deforming, non-erosive and negative for antibodies against anti-CCP in comparison to RA.49 Moreover, there was no statistically significant difference in the frequency of erosive arthritis or anti-CCP positivity between patients with HCV-antibody-positive and HCV-antibody-negative RA.49 Thus, anti-CCP is a reliable test to distinguish RA from HCV-induced inflammatory arthritis in addition to X-ray findings.46 Together, these findings provide a theoretical basis and support the hypothesis that it is truly RA rather than HCV-associated inflammatory arthritis in the present study. Fourth, there is a paucity of information on laboratory data (eg, SVR, HCV RNA and genotype), genetic predispositions, lifestyle and RA severity in the NHIRD. Therefore, these variables failed to be included in the propensity analysis and the association between SVR, viral count, genotype and RA severity and IBT failed to be directly analysed. Nevertheless, we included Charlson comorbidity index in the regression analysis to control for confounding. This method had been applied in prior administrative database research.26–28 Furthermore, we used propensity score matching to minimise allocation bias and improve the comparability of the IBT and control cohorts.50 Finally, the SVR rate to IBT in Asian patients with HCV genotype-1 infection is higher than that in Western patients with HCV genotype-1 infection, largely because of the greater prevalence of interleukin-28B genotypic polymorphism in Asia.14 15 Hence, we are convinced of IBT’s efficacy in the treated cohort, because overall SVR rates with IBT have exceeded 70% in Taiwan.15 However, discretion is advised in the interpretation of these findings in the Western populations.

In conclusion, this national cohort study of Taiwanese patients with HCV infection indicates that IBT may reduce the risk of RA and contributes to growing evidence that HCV infection has a role in the pathogenesis of RA. Further investigation is warranted to well recognise the mechanism underlying this effect.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: Study design: C-HT, N-SL and Yi-CC. Acquisition of data: Yi-CC and S-JT. Analysis and interpretation of data: C-HT, N-SL, C-YL, S-JT, Ye-CC and Yi-CC. Manuscript writing: C-HT and Yi-CC. All authors were involved in revising the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final revision to be published.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The Institution Review Board of the Buddhist Dalin Tzu Chi Hospital (B10501028).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Yu KH, See LC, Kuo CF, et al. . Prevalence and incidence in patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases: a nationwide population-based study in Taiwan. Arthritis Care Res 2013;65:244–50. 10.1002/acr.21820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lai CH, Lai MS, Lai KL, et al. . Nationwide population-based epidemiologic study of rheumatoid arthritis in Taiwan. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2012;30:358–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hoovestol RA, Mikuls TR. Environmental exposures and rheumatoid arthritis risk. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2011;13:431–9. 10.1007/s11926-011-0203-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen HH, Huang N, Chen YM, et al. . Association between a history of periodontitis and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis: a nationwide, population-based, case-control study. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1206–11. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lu MC, Yan ST, Yin WY, et al. . Risk of rheumatoid arthritis in patients with type 2 diabetes: a nationwide population-based case-control study. PLoS One 2014;9:e101528 10.1371/journal.pone.0101528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stolt P, Bengtsson C, Nordmark B, et al. . Quantification of the influence of cigarette smoking on rheumatoid arthritis: results from a population based case-control study, using incident cases. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:835–41. 10.1136/ard.62.9.835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Agnello V, De Rosa FG. Extrahepatic disease manifestations of HCV infection: some current issues. J Hepatol 2004;40:341–52. 10.1016/j.jhep.2003.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zignego AL, Ferri C, Pileri SA, et al. . Extrahepatic manifestations of Hepatitis C Virus infection: a general overview and guidelines for a clinical approach. Dig Liver Dis 2007;39:2–17. 10.1016/j.dld.2006.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cacoub P, Renou C, Rosenthal E, et al. . Extrahepatic manifestations associated with hepatitis C virus infection. A prospective multicenter study of 321 patients. The GERMIVIC. Groupe d’Etude et de Recherche en Medecine Interne et Maladies Infectieuses sur le Virus de l’Hepatite C. Medicine 2000;79:47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tzang BS, Chen TY, Hsu TC, et al. . Presentation of autoantibody to proliferating cell nuclear antigen in patients with chronic hepatitis B and C virus infection. Ann Rheum Dis 1999;58:630–4. 10.1136/ard.58.10.630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Su FH, Wu CS, Sung FC, et al. . Chronic hepatitis C virus infection is associated with the development of rheumatoid arthritis: a nationwide population-based study in taiwan. PLoS One 2014;9:e113579 10.1371/journal.pone.0113579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. European Association for Study of Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol 2014;60:392–420. 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hsu YC, Ho HJ, Huang YT, et al. . Association between antiviral treatment and extrahepatic outcomes in patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Gut 2015;64:495–503. 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liu CH, Kao JH. Nanomedicines in the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection in Asian patients: optimizing use of peginterferon alfa. Int J Nanomedicine 2014;9:2051–67. 10.2147/IJN.S41822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hsu YC, Lin JT, Ho HJ, et al. . Antiviral treatment for hepatitis C virus infection is associated with improved renal and cardiovascular outcomes in diabetic patients. Hepatology 2014;59:1293–302. 10.1002/hep.26892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Conlon KC, Urba WJ, Smith JW, et al. . Exacerbation of symptoms of autoimmune disease in patients receiving alpha-interferon therapy. Cancer 1990;65:2237–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Quesada JR, Gutterman JU. Psoriasis and alpha-interferon. Lancet 1986;1:1466–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)91502-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ioannou Y, Isenberg DA. Current evidence for the induction of autoimmune rheumatic manifestations by cytokine therapy. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:1431–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Conrad B. Potential mechanisms of interferon-alpha induced autoimmunity. Autoimmunity 2003;36:519–23. 10.1080/08916930310001602137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ferri C, Sebastiani M, Antonelli A, et al. . Current treatment of hepatitis C-associated rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Res Ther 2012;14:215 10.1186/ar3865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zuckerman E, Keren D, Rozenbaum M, et al. . Hepatitis C virus-related arthritis: characteristics and response to therapy with interferon alpha. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2000;18:579–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kemmer NM, Sherman KE. Hepatitis C-related arthropathy: Diagnostic and treatment considerations. J Musculoskelet Med 2010;27:351–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cacopardo B, Benanti F, Pinzone MR, et al. . Rheumatoid arthritis following PEG-interferon-alfa-2a plus ribavirin treatment for chronic hepatitis C: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Res Notes 2013;6:437 10.1186/1756-0500-6-437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Izumi Y, Komori A, Yasunaga Y, et al. . Rheumatoid arthritis following a treatment with IFN-alpha/ribavirin against HCV infection. Intern Med 2011;50:1065–8. 10.2169/internalmedicine.50.4790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Okanoue T, Sakamoto S, Itoh Y, et al. . Side effects of high-dose interferon therapy for chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol 1996;25:283–91. 10.1016/S0168-8278(96)80113-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen YC, Lin HY, Li CY, et al. . A nationwide cohort study suggests that hepatitis C virus infection is associated with increased risk of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2014;85:1200–7. 10.1038/ki.2013.455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chen YC, Su YC, Li CY, et al. . A nationwide cohort study suggests chronic hepatitis B virus infection increases the risk of end-stage renal disease among patients in Taiwan. Kidney Int 2015;87:1030–8. 10.1038/ki.2014.363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen YC, Hwang SJ, Li CY, et al. . A Taiwanese Nationwide Cohort Study Shows Interferon-Based Therapy for Chronic Hepatitis C Reduces the Risk of Chronic Kidney Disease. Medicine 2015;94:e1334 10.1097/MD.0000000000001334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chen YC, Li CY, Tsai SJ, et al. . Nationwide cohort study suggests that nucleos(t)ide analogue therapy decreases dialysis risk in Taiwanese chronic kidney disease patients acquiring hepatitis B virus infection. World J Gastroenterol 2018;24:917–28. 10.3748/wjg.v24.i8.917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hsu CS, Kao JH, Chao YC, et al. . Interferon-based therapy reduces risk of stroke in chronic hepatitis C patients: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;38:415–23. 10.1111/apt.12391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hsu YC, Ho HJ, Wu MS, et al. . Postoperative peg-interferon plus ribavirin is associated with reduced recurrence of hepatitis C virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2013;58:150–7. 10.1002/hep.26300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wu CY, Chen DY, Shen JL, et al. . The risk of cancer in patients with rheumatoid arthritis taking tumor necrosis factor antagonists: a nationwide cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther 2014;16:449 10.1186/s13075-014-0449-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chen CY, Liu CY, Su WC, et al. . Factors associated with the diagnosis of neurodevelopmental disorders: a population-based longitudinal study. Pediatrics 2007;119:e435–43. 10.1542/peds.2006-1477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, et al. . Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 2002;347:975–82. 10.1056/NEJMoa020047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dienstag JL, McHutchison JG. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the management of hepatitis C. Gastroenterology 2006;130:231–64. 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hwang SJ, Lee SD, Chan CY, et al. . A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial of consensus interferon in the treatment of Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:2496–500. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01382.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yao GB, Fu XX, Tian GS, et al. . A multicenter, randomized, controlled trial of interferon alfacon-1 compared with alpha-2a-interferon in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000;15:1165–70. 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02307.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. De Maeyer E, De Maeyer-Guignard J, interferons TI. Int Rev Immunol 1998;17:53–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liu Z, Bethunaickan R, Huang W, et al. . Interferon-α accelerates murine systemic lupus erythematosus in a T cell-dependent manner. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:219–29. 10.1002/art.30087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wong T, Majchrzak B, Bogoch E, et al. . Therapeutic implications for interferon-alpha in arthritis: a pilot study. J Rheumatol 2003;30:934–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shiozawa S, Shiozawa K, Kita M, et al. . A preliminary study on the effect of alpha-interferon treatment on the joint inflammation and serum calcium in rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol 1992;31:405–8. 10.1093/rheumatology/31.6.405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cacoub P, Poynard T, Ghillani P, et al. . Extrahepatic manifestations of chronic hepatitis C. MULTIVIRC Group. Multidepartment Virus C. Arthritis Rheum 1999;42:2204–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sayiner ZA, Haque U, Malik MU, et al. . Hepatitis C virus infection and its rheumatologic implications. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;10:287–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Palazzi C, D’Amico E, D’Angelo S, et al. . Rheumatic manifestations of hepatitis C virus chronic infection: Indications for a correct diagnosis. World J Gastroenterol 2016;22:1405–10. 10.3748/wjg.v22.i4.1405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sheu JJ, Kang JH, Lin HC, et al. . Hyperthyroidism and risk of ischemic stroke in young adults: a 5-year follow-up study. Stroke 2010;41:961–6. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.577742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chou C, Liao H, Chen C, et al. . The Clinical Application of Anti-CCP in Rheumatoid Arthritis and Other Rheumatic Diseases. Biomark Insights 2007;2:117727190700200–71. 10.1177/117727190700200007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lin HK, Lan JL, Chen DY, et al. . The diagnostic value of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies and rheumatoid factor in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Formosan J Rheumatol 2008;22:68–73. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chang PY, Yang CT, Cheng CH, et al. . Diagnostic performance of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide and rheumatoid factor in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Rheum Dis 2016;19:880–6. 10.1111/1756-185X.12552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mahmoud GA, Zayed HS, Sherif MM, et al. . Characteristics of rheumatoid arthritis patients with concomitant hepatitis C virus infection. The Egyptian Rheumatologist 2011;33:139–45. 10.1016/j.ejr.2011.05.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. D’Agostino RB. Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med 1998;17:2265–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.