Abstract

Background

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is a leading cause of death globally. Increase in AMI mortality during winter has also been identified in existing literature. This has been associated with low outdoor and indoor temperatures and increasing age. The relationship between AMI and other factors such as gender and socioeconomic factors varies from study to study. Influenza epidemics have also been identified as a contributory factor.

Objective

This paper aims to illustrate the seasonal trend in mortality due to AMI in England and Wales with emphasis on excess winter mortality (EWM).

Methods

Monthly mortality rates per 10 000 population were calculated from data provided by the UK Office for National Statistics (ONS) for 1997–2005. To quantify the seasonal variation in winter, the EWM estimates (EWM, EWM ratio, Excess Winter Mortality Index) for each year were calculated. Negative binomial regression model was used to estimate the relationship between increasing age and EWM.

Results

The decline in mortality rate for AMI was 6.8% yearly between August 1997 and July 2005. Significant trend for reduction in AMI-associated mortality was observed over the period (p<0.001). This decline was not seen with EWM (p<0.001). 17% excess deaths were observed during winter. This amounted to about 20 000 deaths over the 8-year period. Increasing winter mortality was seen with increasing age for AMI.

Conclusion

EWM secondary to AMI does occur in England and Wales. Excess winter deaths due to AMI have remained high despite decline in overall mortality. More research is needed to identify the relationship of sex, temperature, acclimatisation, vitamin D and excess winter deaths due to AMI.

Keywords: winter mortality, seasonal variation, myocardial infarction, fuel poverty, outdoor temperature

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The data used involved a large sample size, and this was able to capture relevant results in the data analysis and this data represents the population of interest.

The paper uses statistical methods that have been verified to analyse trends in mortality as well as to define the concept of excess winter mortality. The data analysis was thorough, standardising the outcomes and presenting the data in a way that can be comparable with various populations.

Although the data provided by the Office for National Statistics was complete and considered accurate, the data characteristics, however, restricted the number of variables that could be controlled such as sex distribution. To reach a more robust conclusion, it would have been necessary to have data to test for effects of housing, indoor temperatures, outdoor temperatures, influenza epidemics and other possible confounders.

The population data which were used as denominator would reduce in accuracy as the year of study moved away from the recent census (29 April 2001). This is because the mid-year populations after this date were extrapolated using birth and death data; these data are prone to their own type of error. However, it is anticipated that the brief period used in the research was unlikely to experience any dramatic changes in population.

Background

Studies over time have observed an increase in mortality rate during winter months.1–3 This appears to be a global phenomenon with evidence of excess winter mortality occurring in a number of countries, including the UK,4 5 Japan,6 Brazil,7 Canada,2 the USA3 and New Zealand.8

The relationship between mortality and temperature observes a U shape9: an increase in mortality is seen with extremes in temperature. Excess winter mortality which is defined as ‘a significant increase in the number of deaths during winter compared with the average of the non-winter seasons’ has been linked to the drop in temperature.10 Low temperatures have been implicated in the increase in number of deaths during the winter months; however, they are not due to hypothermia. There is evidence to suggest that low temperatures trigger pathological mechanisms that lead to increase in blood pressure and thrombus formation.2 The consequence of this is the initiation of physiological stress that results in the development of a myocardial infarction or a stroke. A study involving data from various countries in Europe found a similar association but also identified 18°C as the threshold for this to occur.11 Research carried out in Scotland12 and England13 could quantify this relationship: a 1°C drop in temperature resulted in a 1%–2% increase in the number of deaths. This corresponds to increased odds of dying during the winter by 1.5%.10

The effects of temperature are both direct and immediate. Time series analyses have shown that there is a minimum lag time of about 24 hours between drop in temperature and increase in mortality.14 The impact of cold temperature could also extend over a period of 1–2 weeks. This lag time shows that there is a possible mechanism that is initiated by the low outdoor temperatures directly that leads to death supporting evidence from previous studies. It has also been shown that the effect of temperature is significantly potentiated by high relative humidity and strong winds.15

There are suggestions that the influence of winters and low temperatures on the increase in mortality rates is preventable. This is because there is ecological evidence that countries with colder winters do not have greater excess winter mortality when compared with countries with milder winters,4 for example, the UK when compared with Scandinavian countries.16 17 This observation is referred to as the excess winter paradox.

Housing insulation and the concept of fuel poverty, both of which affect the indoor temperature, are some of the factors thought to be responsible for the paradox. Houses in Britain have lower insulation properties compared with houses in Germany, Russia or the Scandinavian countries.18 Due to the low insulation properties of houses in England and Wales, it is more expensive to warm these homes when compared with houses in other European states. This introduces the concept of fuel poverty. Fuel poverty is defined as a situation ‘when in order to heat its home to an adequate standard of warmth a household needs to spend more than 10% of its income on total fuel use’.19 The WHO’s recommendation of adequate standard warmth is defined as 18°C in occupied rooms and 21°C in living room. The temperature level of 18°C is remarkable because below this threshold has been identified as when significant mortality occurs. The ability to generate heat to a surrounding temperature above this identified threshold might prove necessary. A behavioural component may also be contributory to the paradox. For example, people living in warmer winters, such as in the UK and Portugal, were less likely to heat the living and bedroom to recommended levels when outdoor temperature drops.11 This is a marked contrast to persons leaving in countries like Russia20 who maintained their indoor temperatures at 20.9°C and 24.2°C when the temperature outside was 7°C. Studies also show that people in the UK were also less likely to wear protective clothing such as hats, heavy jackets and gloves.11 The UK Government has acknowledged that excess winter mortality is a problem and currently has put in place policies to tackle this phenomenon.

Other factors that are considered to play a role in excess winter mortality include socioeconomic status,17 influenza,21 22 age16 and vitamin D deficiency. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] levels <20 ng/mL is considered an independent additional risk factor for acute myocardial infarction (AMI)23 24 and is not just a reflection of poor health. Dietary sources of vitamin D are usually insufficient, and deficiency occurs with inadequate sun exposure. Seasonality in 25(OH)D levels have been observed and levels are usually lower around winter,23 25 creating an extra burden on the cardiovascular system by various postulated mechanisms leading to significant coronary artery disease26 and poor collateral circulation.27 This seasonality is attributed to variability in ultraviolet-B (UVB) exposure during the seasons.28 There is the suggestion that correction of vitamin D deficiency may reduce the cardiovascular risk.

There are few studies that have examined the phenomenon of excess winter mortality specifically due to AMI in England and Wales. Most studies treat the subject of excess winter mortality by assessing total mortality without isolating individual diagnosis. Assessing individual diseases might produce stronger evidence on the impact seasonal variation on a particular disease condition. Due to the overwhelming global impact of this condition, it is important to identify seasonal variation of mortality due to AMI and also points of possible preventive strategies that can help in reducing the incidence of the disease.

Methodology

This study was a secondary data analysis that assessed excess winter deaths due to AMI in England and Wales. The study used anonymised mortality data provided by the Office for National Statistics (ONS), UK, and mean monthly temperature data provided by the Meteorological Office, UK. The database provided by the ONS consisted of anonymised data of daily mortality in England and Wales for the period from 1997 to 2005. The International Classification of Disease (ICD) was used for coding the various cause of death. The ninth edition (ICD-9) was used from 1997 to 2000 while the tenth edition (ICD-10) was used between 2001 and 2005. The cause of death considered for the study was AMI (ICD-9:410; ICD-10: I21). This was presented in three age groups: 0–64 years, 65–74 years, and 75 years and above. There was no sex distribution provided.

Age-specific mortality rates were also calculated for each age group. The daily, monthly and yearly mortality rates were calculated, and the age-specific population served as denominator. The population data for each year and each age group were extracted from ONS yearly publications. The monthly rates were standardised to 30-day months.

Adjustments in mortality rates were also made to account for changes in ICD coding. This was done using this formula: MA (y, d)=MO (y, d). R. MA is the adjusted daily mortality (deaths) for a day, d, in year, y. MO is the observed mortality. R is the comparability ratio: the ICD-10/ICD-9 comparability ratio for AMI 0.9889 was used to adjust ICD-9 code death counts.29

Specifically, the concept of excess winter deaths was explored in this study. The method used to analyse the excess winter deaths was first described by Curwen, and it is similar to that used by the ONS.30 The months of December–March defines the winter period. The non-winter period is defined as the months of August–November before this winter period, and the months of April–July following the winter period.

In order to quantify the seasonal variation in winter, the excess winter mortality (EWM), EWM ratio (EWMR) and the EWM Index (EWMI) for each year were calculated. The EWM reflects the absolute difference in mortality between the winter season and non-winter season. Whereas the EWMR represents the relative risk of death during the winter months compared with the non-winter months. The EWMI represents a variant of relative risk reduction or ‘excess’. The EWMR and EWMI are viable tools for comparisons between age, sex, regions or countries. These estimates were also calculated for each age group. These estimates were calculated using the following formulae:

EWM=O–E

EWMR=O/E

EWMI = (O–E)/E or EWMR-1 (represented as a percentage)

Where, O is the observed death count. This is the total death counts during the winter months, a period of 4 months (winter deaths). E is the expected death count which is the total death counts during the non-winter months, a period of 8 months, divided by 2.

Direct correlation between mean monthly temperature and monthly mortality rate was carried out with a significance level set at <0.05. Addition trend analysis with autoregressive integrated moving average model and forecasting was done with a significance level <0.05.

A regression model was used in assessing the rates of death during the winter season and non-winter seasons. The log-linear model was derived with the mortality count during winter period as the estimated outcome while age was the explanatory variable. The hypothesis was to test if there was any difference between EWMRs among the various age groups. Therefore, the log of the average non-winter deaths was used as offset to fit the model. The model was fitted using a negative binomial model with a log-link function due to overdispersion in the initial analysis. All analyses were carried out using SPSS V.19. Significant p value was defined as <0.05.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved in the design study.

Results

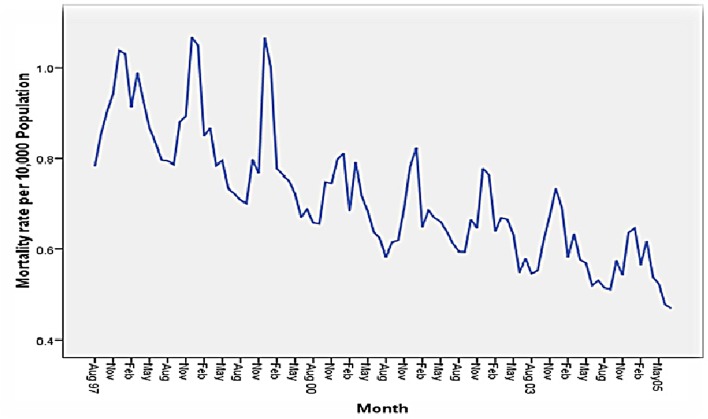

Between August 1997 and July 2005, there were 359 408 deaths due to AMI with an average death count of 44 926 occurring yearly (table 1). Of the total deaths, 62.7% were seen in the age group 75 years and above, 23.1% in the age group 65–74 years and 14.2% in the age group 0–64 years. A steady decline in the absolute death counts and mortality rates were seen in all age groups across the years (figure 1). Overall, the decline in mortality rate for AMI was 6.8% yearly between August 1997 and July 2005.

Table 1.

Yearly mortality patterns of acute myocardial infarction from August 1997 to July 2005

| Year period* | Mortality rate per 10 000 (number of deaths) | |||

| Age: 0–64 years | Age: 65–74 years | Age: 75 years and above | Total | |

| 1997/1998 | 1.96 (8184) | 24.72 (14299) | 83.59 (33678) | 10.87 (56161) |

| 1998/1999 | 1.81 (7581) | 22.59 (13119) | 79.84 (32283) | 10.22 (52983) |

| 1999/2000 | 1.64 (6924) | 20.11 (11724) | 74.70 (30330) | 9.41 (48978) |

| 2000/2001 | 1.52 (6435) | 17.99 (10528) | 67.98 (27716) | 8.55 (44679) |

| 2001/2002 | 1.40 (5964) | 16.28 (9567) | 65.00 (26610) | 8.03 (42141) |

| 2002/2003 | 1.35 (5784) | 14.71 (8685) | 64.45 (26495) | 7.77 (40964) |

| 2003/2004 | 1.21 (5189) | 13.39 (7937) | 60.84 (25125) | 7.22 (38251) |

| 2004/2005 | 1.16 (5005) | 11.84 (7066) | 55.79 (23180) | 6.62 (35251) |

| Total | 1.51 (51066) | 17.70 (82925) | 69.02 (225417) | 8.59 (359408) |

*Year period is August the previous year to July the next year. E.g. Year period 1997/1998 is August 1997 to July 1998.

Figure 1.

A steady decline in mortality rate due to acute myocardial infarction over the year periods.

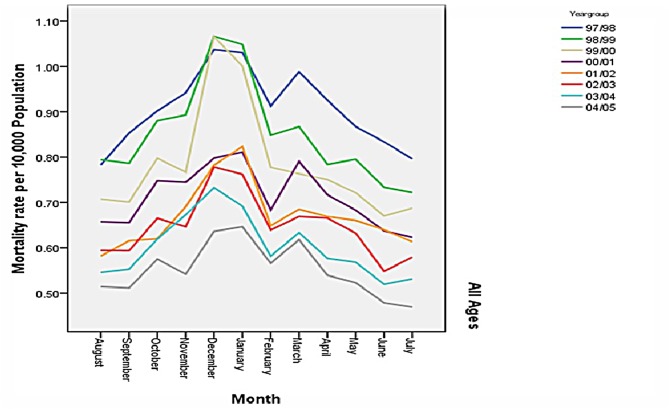

A sharp rise in mortality is noticed in early November and peaks between December and January (figure 2). A second rise also occurs around the month of March but the mortality rate seen during this period is not as high as that observed during the December and January months. The lowest mortality rates occurred during July and August months.

Figure 2.

Showing variation in mortality rate over the months over the year periods.

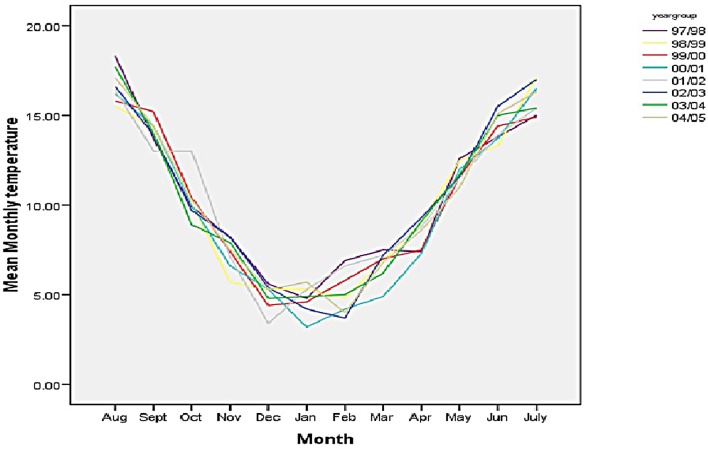

A plot of the mean temperatures in Celsius (figure 3) showed a trough during the months of December to March and when compared with figure 2, this indicates that lower temperatures are observed during the peaks of mortality during the year. A plot of the mean monthly temperature with mortality rate showed a significant negative correlation between the two variables (r=−0.48; p<0.0001).

Figure 3.

A plot of the mean monthly temperatures in Celsius with an obvious dip in temperatures during the months of December to March.

Estimation of EWM due to AMI

EWM was seen in all the years observed. An average of about 2463 excess winter deaths occurred yearly. In all year periods, the highest absolute EWM occurred in those 75 years and above (table 2). This age group also contributed an average of 70% to the excess winter deaths yearly. The EWM over the 8-year period resulted in 19 635 total deaths. This is equivalent to 5.5% of the overall yearly mortality due to AMI over the 8-year period.

Table 2.

Excess winter mortality and index secondary to AMI between 1997 and 2005

| Year period | EWM (EWMI) | |||

| Age: 0–64 years, n (%) | Age: 65–74 years, n (%) | Age: 75 years +, n (%) | Total, n (%) | |

| 1997/1998 | 244.5 (9) | 731.5 (16) | 1716.0 (16) | 2692.0 (15) |

| 1998/1999 | 281.5 (12) | 756.0 (18) | 2280.0 (23) | 3317.5 (20) |

| 1999/2000 | 333.0 (15) | 643.5 (17) | 2715.0 (29) | 3691.5 (24) |

| 2000/2001 | 148.5 (7) | 368.5 (11) | 1332.5 (15) | 1849.5 (13) |

| 2001/2002 | 258.0 (14) | 453.0 (15) | 1372.5 (16) | 2083.5 (16) |

| 2002/2003 | 196.5 (11) | 423.0 (15) | 1430.0 (17) | 2049.5 (16) |

| 2003/2004 | 251.0 (15) | 260.0 (10) | 1339.5 (17) | 1850.5 (15) |

| 2004/2005 | 140.5 (9) | 466.0 (21) | 1494.5 (21) | 2101.0 (19) |

| Total | 1853.5 (11) | 4101.5 (16) | 13 680.0 (19) | 19 635.0 (17) |

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; EWM, excess winter mortality; EWMI, EWM Index.

The EWMR (winter:non-winter rate ratio) is greater than one in all year periods considered, indicating that there is greater mortality in winter compared with the non-winter months (table 3). The EWMR describes the risk in dying during winter compared with non-winter months. This can also be represented as a percentage (EWMI). This shows that there is an average 17% excess death yearly (table 2).

Table 3.

Excess winter mortality ratio secondary to acute myocardial infarction between 1997 and 2005

| Year period | Excess winter mortality ratio (CI) | |||

| Age: 0–64 years | Age: 65–74 years | Age: 75 years + | Total | |

| 1997/1998 | 1.09 (1.07 to 1.11) | 1.16 (1.15 to 1.18) | 1.16 (1.15 to 1.17) | 1.15 (1.14 to 1.16) |

| 1998/1999 | 1.12 (1.09 to 1.14) | 1.18 (1.17 to 1.20) | 1.23 (1.22 to 1.24) | 1.20 (1.19 to 1.21) |

| 1999/2000 | 1.15 (1.13 to 1.17) | 1.17 (1.16 to 1.19) | 1.29 (1.28 to 1.31) | 1.24 (1.24 to 1.25) |

| 2000/2001 | 1.07 (1.05 to 1.09) | 1.11 (1.09 to 1.13) | 1.15 (1.14 to 1.16) | 1.13 (1.12 to 1.14) |

| 2001/2002 | 1.14 (1.11 to 1.16) | 1.15 (1.13 to 1.17) | 1.16 (1.15 to 1.17) | 1.16 (1.15 to 1.17) |

| 2002/2003 | 1.11 (1.08 to 1.13) | 1.15 (1.13 to 1.17) | 1.17 (1.16 to 1.18) | 1.16 (1.15 to 1.17) |

| 2003/2004 | 1.15 (1.13 to 1.18) | 1.10 (1.08 to 1.12) | 1.17 (1.16 to 1.18) | 1.15 (1.14 to 1.16) |

| 2004/2005 | 1.09 (1.06 to 1.11) | 1.21 (1.19 to 1.23) | 1.21 (1.19 to 1.22) | 1.19 (1.18 to 1.20) |

| All periods | 1.11 (1.10 to 1.13) | 1.16 (1.14 to 1.17) | 1.19 (1.18 to 1.20) | 1.17 (1.17 to 1.18) |

A regression analysis was carried out using a negative binomial regression to estimate the EWMR and age (table 4). The relative risk of excess mortality in age groups 65–74 years and 75 years and above was 1.36 and 2.45, respectively, compared with the younger age group.

Table 4.

Excess winter mortality ratio and age

| Age | Coefficient | EWM (%) | Relative risk | P values |

| 0–64 years | reference | 11 | ||

| 65–74 years | 0.31 | 16 | 1.36 (1.18–1.57) | <0.0001 |

| 75 years + | 0.89 | 19 | 2.45 (2.16–2.77) | <0.0001 |

EWM, excess winter mortality.

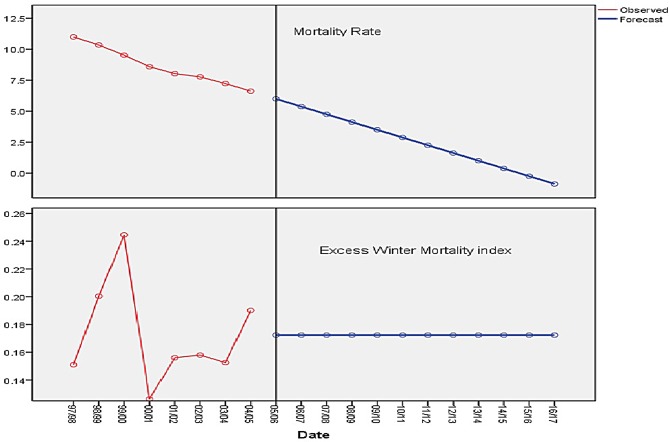

Figure 4 shows the trend of mortality rate and EWMI secondary to AMI. There is a steady decline in mortality rate with a significant trend for reduction in AMI-associated mortality observed over the period studied (p<0.001). The forecast for the next 11-year periods shows a continued decline. The forecast for the EWMI shows no change and remains relatively the same (p<0.001).

Figure 4.

Trend in mortality rate and EWMI over the year period observed and forecast for the next 11 years. There is a steady decline in mortality rate with a significant trend for reduction in AMI-associated mortality. The forecast for the next 11-year period shows a continued decline. The forecast for the EWMI shows no change. AMI, acute myocardial infarction; EWMI, Excess Winter Mortality Index.

Discussion

The results from the data analysis showed that there is a significant increase in mortality rates due to AMI during the winter period in England and Wales. In this study, the EWMR over the 8-year study period for all age groups was 1.17 with a resultant 17% excess winter deaths for AMI. This amounted to about 20 000 excess deaths due to this disease. From their analysis of 2266 deaths, Biedrzycki and Baithun1 in their study of mortality from myocardial infarction found that December was the peak month of mortality. A decline was observed from February onwards with the lowest mortality rate observed during the month of August. This pattern is similar to what was elicited in this paper: the highest mortality rates peaked between December and January, and lowest mortality rates were observed during the months of July and August. Besides the demonstrable winter excess, the monthly mortality rate plot showed a double peak. A peak in mortality, which was clearly above the mean mortality rate, was observed around the month of March. This second peak in mortality was less than that seen in the months of December and January.

Since fluctuations in daily temperatures could not be appreciated from monthly mean temperature data, it is possible that absolute low outdoor temperatures may not be the only factor in causing mortality but rather daily changes in temperature may also be significant. It has already been established that in most countries in Europe a 1°C drop in temperature is associated with increase in mortality.12 13 Carson et al in their study found that cardiovascular diseases were more sensitive to temperature changes than respiratory disease.31 This relationship has also been recognised in other studies: Kysely et al14 found that fluctuations in daily temperatures resulted in increase in mortality rates of cardiovascular diseases. They also noted that a second cold spell usually had a lower excess mortality and suggested that the reason for this might be that some form of acclimatisation to the previous cold spell might be protective against the next. This might explain the double peaks that were observed in this study. Large variations in temperatures between winter and non-winter months as seen in countries with warm winters such as England and Wales may also explain the winter paradox observed in Europe. It is possible that the lack of acclimatisation due to the non-persistent cold weather, unlike in Iceland and Russia, may lead to a greater impact when the winter season does arrive. However, this is not conclusive and would require more research to clearly define such an association.

The study has shown that AMI has undergone a steady decline in England and Wales over the years. This is remarkable. The decline of mortality rate from 10.87 deaths per 100 000 population to 6.62 deaths per 10 000 population was observed over the 8-year study period. This was statistically significant. The reasons for this may include such factors as better diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, healthier life styles of the population and better awareness of the public. Despite this steady decrease in total yearly mortality rate, the risk of dying from AMI during winter has remained the same. This is suggestive that EWM is not a function of the overall mortality. This has important control and prevention implications: the measures used to control overall mortality may not necessarily influence winter excess.

One of such measures could be vitamin D supplementation. There are several factors which could be possibly associated with EWM, and this may include seasonal variations in solar UVB doses and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] concentrations, temperature and humidity.28 Among these factors, possibly 25(OH)D concentration (<20 ng/mL) would be a modifiable risk factor, and its supplementation to levels greater than 36 ng/mL might reduce death rates significantly in winter months. In a Study in Iran,32 supplementation of vitamin to levels greater than 20 ng/mL was effective in reducing the cholesterol level by about 16 mg/dL. The clinical significance of this result needs to be investigated. Several clinical trials as well as observational and ecological studies are ongoing, and these will provide results to clarify whether vitamin D deficiency is a modifiable factor to prevent cardiovascular disease.

There was a gradient relationship between excess winter deaths and age: we found increasing winter deaths with increasing age. A regression model was used to estimate the relationship between age and winter mortality, and we found a more than twofold increase in risk when the oldest age group was compared with the youngest. The older age groups seem to be more vulnerable to the effects of winter and should be an important risk targeted group for prevention policies and strategies.

The excess winter paradox observed across countries in Europe and the identified decline in winter deaths seen in some countries suggest that significant increases in death during winter are preventable. The decline observed in EWM in all age groups, as well as overall, observed during the 2000–2001 year is interesting. This period had the lowest EWMR and also observed the highest percentage drop in EWMR. It also had the least absolute excess winter death counts among all the year periods studied. A few months earlier, the UK Government introduced innovative measures to tackle the burden of winter excess deaths. These measures were robust interventions incorporated in the fuel poverty strategy. This sharp drop in EWMR may suggest that these measures may have had an immediate impact. However, this study cannot conclusively confirm this. Nevertheless, if these strategies had an immediate impact, it was definitely short-lived. This is because despite the fluctuations the trend has remained the same. In other words, the increased risk of dying during winter due to AMI has remained high in England and Wales despite the various strategies implemented by the government, and the trend analysis shows that it will remain so for a couple of years. It might be that it is too soon to evaluate the impact of these measures or they may not be effective.

The results of this study can be generalised to any population where significant winter occurs, and an assumption can be made that a significant winter is when the temperature drops below 18°C over a defined period. As elucidated in the preceding paragraphs, this has been observed in various countries in Europe, America and Asia. However, the impact in winter mortality may vary from society to society because of other ecological factors such as behavioural, housing and immunisation practices.

This study was a secondary data analysis, and it faced certain limitations. Although the data provided by the ONS were complete and considered accurate, the data characteristics however restricted the number of variables that could be controlled such as sex distribution. To reach a more robust conclusion, it would have been necessary to have data to test for effects of housing, indoor temperatures, outdoor temperatures, influenza epidemics and other possible confounders. It has been identified in existing literature that these factors play a part in the complex mechanism that brings about EWM. It would have been appropriate to adjust for their effects. Also, the population data which was used as denominator would reduce in accuracy as the year of study moved away from the recent census (29 April 2001). This is because the mid-year populations after this date were extrapolated using birth and death data; these data are prone to their own type of error. However, it is anticipated that the brief period used in the research was unlikely to experience any dramatic changes in population. The method used in this study to estimate EWM was first described by Curwen,4 and this method defines the winter period between December and January. It has an advantage because these months have constantly shown mortality rates greater than the mean monthly mortality rates. It is essential to note this method of assessment when comparing future studies on EWM as other studies may use calendar winter months in their analysis.

Conclusion

This study has shown that increased winter mortality due to AMI does exist. The EWM has remained high for AMI for England and Wales over the years. The study also identified an association between increasing age and increasing EWM. There is a possibility that acclimatisation may play a role in the mechanisms that initiate winter deaths.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: OO: literature review, data analysis and interpretation of data. Drafting the manuscript, revising manuscript. Approval of the version of the manuscript to be published. BO: literature review, drafting the manuscript, revising manuscript. Approval of the version of the manuscript to be published. RM: conception and design of study, acquisition of data, literature review, revising manuscript. Approval of the version of the manuscript to be published. KP: drafting the manuscript, revising manuscript. Approval of the version of the manuscript to be published.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data used in this study were obtained from the Office of National Statistics, UK.

References

- 1. Biedrzycki O, Baithun S. Seasonal variation in mortality from myocardial infarction and haemopericardium. A postmortem study. J Clin Pathol 2006;59:64–6. 10.1136/jcp.2005.025965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sheth T, Nair C, Muller J, et al. Increased winter mortality from acute myocardial infarction and stroke: the effect of age. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;33:1916–9. 10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00137-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Spencer FA, Goldberg RJ, Becker RC, et al. Seasonal distribution of acute myocardial infarction in the second National Registry of Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998;31:1226–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Curwen M. Excess winter mortality: a British phenomenon? Health Trends 1991;22:169–72. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Healy JD. Excess winter mortality in Europe: a cross country analysis identifying key risk factors. J Epidemiol Community Health 2003;57:784–9. 10.1136/jech.57.10.784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rumana N, Kita Y, Turin TC, et al. Seasonal pattern of incidence and case fatality of acute myocardial infarction in a Japanese population (from the Takashima AMI Registry, 1988 to 2003). Am J Cardiol 2008;102:1307–11. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sharovsky R, Cé sar LA. Increase in mortality due to myocardial infarction in the Brazilian city of São Paulo during winter. Arq Bras Cardiol 2002;78:106–9. 10.1590/S0066-782X2002000100009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Davie GS, Baker MG, Hales S, et al. Trends and determinants of excess winter mortality in New Zealand: 1980 to 2000. BMC Public Health 2007;7:263–72. 10.1186/1471-2458-7-263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Curriero FC, Heiner KS, Samet JM, et al. Temperature and mortality in 11 cities of the eastern United States. Am J Epidemiol 2002;155:80–7. 10.1093/aje/155.1.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aylin P, Morris S, Wakefield J, et al. Temperature, housing, deprivation and their relationship to excess winter mortality in Great Britain, 1986-1996. Int J Epidemiol 2001;30:1100–8. 10.1093/ije/30.5.1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eurowinter Group. Cold exposure and winter mortality from ischaemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, respiratory disease, and all causes in warm and cold regions of Europe. The Eurowinter Group. Lancet 1997;349:1341–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gemmell I, McLoone P, Boddy FA, et al. Seasonal variation in mortality in Scotland. Int J Epidemiol 2000;29:274–9. 10.1093/ije/29.2.274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bhaskaran K, Hajat S, Haines A, et al. Short term effects of temperature on risk of myocardial infarction in England and Wales: time series regression analysis of the Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project (MINAP) registry. BMJ 2010;341:c3823 10.1136/bmj.c3823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kysely J, Pokorna L, Kyncl J, et al. Excess cardiovascular mortality associated with cold spells in the Czech Republic. BMC Public Health 2009;9:19 10.1186/1471-2458-9-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kunst AE, Looman CW, Mackenbach JP. Outdoor air temperature and mortality in The Netherlands: a time-series analysis. Am J Epidemiol 1993;137:331–41. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Laake K, Sverre JM. Winter excess mortality: a comparison between Norway and England plus Wales. Age Ageing 1996;25:343–8. 10.1093/ageing/25.5.343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McKee CM. Deaths in winter: can Britain learn from Europe? Eur J Epidemiol 1989;5:178–82. 10.1007/BF00156826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Clinch JP, Healy JD. Housing standards and excess winter mortality. J Epidemiol Community Health 2000;54:719–20. 10.1136/jech.54.9.719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fuel Poverty Team. UK fuel poverty strategy: November 2001 - Ministerial Foreword. www.berr.gov.uk/files/file16495.pdf (Accessed 5 Aug 2010).

- 20. Donaldson GC, Tchernjavskii VE, Ermakov SP, et al. Winter mortality and cold stress in Yekaterinburg, Russia: interview survey. BMJ 1998;316:514–8. 10.1136/bmj.316.7130.514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Madjid M, Naghavi M, Litovsky S, et al. Influenza and cardiovascular disease: a new opportunity for prevention and the need for further studies. Circulation 2003;108:2730–6. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000102380.47012.92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Donaldson GC, Keatinge WR. Excess winter mortality: influenza or cold stress? Observational study. BMJ 2002;324:89–90. 10.1136/bmj.324.7329.89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tokarz A, Kusnierz-Cabala B, Kuźniewski M, et al. Seasonal effect of vitamin D deficiency in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Kardiol Pol 2016;74:786–92. 10.5603/KP.a2016.0002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Welles CC, Whooley MA, Karumanchi SA, et al. Vitamin D deficiency and cardiovascular events in patients with coronary heart disease: data from the Heart and Soul Study. Am J Epidemiol 2014;179:1279–87. 10.1093/aje/kwu059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Aleksova A, Belfiore R, Carriere C, et al. Vitamin D Deficiency in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction: An Italian Single-Center Study. Int J Vitam Nutr Res 2015;85(1-2):23–30. 10.1024/0300-9831/a000220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Verdoia M, Schaffer A, Sartori C, et al. Vitamin D deficiency is independently associated with the extent of coronary artery disease. Eur J Clin Invest 2014;44:634–42. 10.1111/eci.12281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sahin I, Okuyan E, Gungor B, et al. Lower vitamin D level is associated with poor coronary collateral circulation. Scand Cardiovasc J 2014;48:278–83. 10.3109/14017431.2014.940062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Grant WB, Bhattoa HP, Boucher BJ. Seasonal variations of U.S. mortality rates: Roles of solar ultraviolet-B doses, vitamin D, gene exp ression, and infections. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2017;173:5–12. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2017.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Anderson RN, Miniño AM, Hoyert DL, et al. Comparability of cause of death between ICD-9 and ICD-10: preliminary estimates. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2001;49:1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Johnson H, Griffiths C. Estimating excess winter mortality in England and Wales. Health Statistics Quarterly 2003;20:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Carson C, Hajat S, Armstrong B, et al. Declining vulnerability to temperature-related mortality in London over the 20th century. Am J Epidemiol 2006;164:77–84. 10.1093/aje/kwj147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rahimi-Ardabili H, Pourghassem Gargari B, Farzadi L. Effects of vitamin D on cardiovascular disease risk factors in polycystic ovary syndrome women with vitamin D deficiency. J Endocrinol Invest 2013;36:28–32. 10.3275/8303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.