Abstract

Sodium diisopropylamide in tetrahydrofuran is an effective base for the metalation of 1,4-dienes and isomerization of alkenes. Dienes metalate via tetrasolvated sodium amide monomers, whereas 1-pentene is isomerized by trisolvated monomers. Facile, highly Z-selective isomerizations are observed for allyl ethers under conditions that compare favorably to those of existing protocols. The selectivity is independent of the substituents on the allyl ethers; rate and computational data show that the rates, mechanisms, and roles of sodium–oxygen contacts are substituent-dependent. The competing influences of substrate coordination and solvent coordination to sodium are discussed.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Sodium diisopropylamide (NaDA) is a case study of reagent popularity within the synthetic organic community. First prepared by Levine in 1959,1 NaDA is demonstrably more reactive than lithium diisopropylamide (LDA).2 During the intervening half century, however, NaDA has been used in approximately a dozen studies,3 whereas LDA is probably used thousands of times daily. What explains this huge disparity? We believe inconvenience plays a role: NaDA is insoluble in inert hydrocarbons and unstable in solubilizing ethereal solvents, which makes it difficult to handle as stock solutions.

From previous studies of lithium amides solvated by simple trialkylamines4—an overlooked and underappreciated class of solvents—we surmised that NaDA might be soluble and stable. Indeed, 1.0 M solutions of NaDA in N,N-dimethylethylamine (DMEA), N,N-dimethylbutylamine, or N-methylpyrrolidine are homogeneous and stable for weeks at room temperature and for months and possibly years with refrigeration. NaDA/trialkylamine solutions can be prepared in 15 min from unpurified commercial reagents, which means that long-term storage is unnecessary. As strange as it may sound, organosodium chemistry is likely in its infancy.5,6

Our first study illustrated the synthetic importance of NaDA in DMEA by metalating a dozen functionally diverse substrates and comparing the rates and selectivies with LDA in tetrahydrofuran (THF).7 Subsequent structural studies showed that NaDA is dimeric when solvated by a number of mono-, di-, and trifunctional solvents.8 Tetrasolvated dimer 1 is germane to the work described herein.

The current study explored NaDA-mediated metalations of alkenes and dienes in THF to probe the role of aggregation and solvation (Scheme 1). We examined whether potentially coordinating substituents influence rate and mechanism through direct sodium–ligand interactions or through induction.

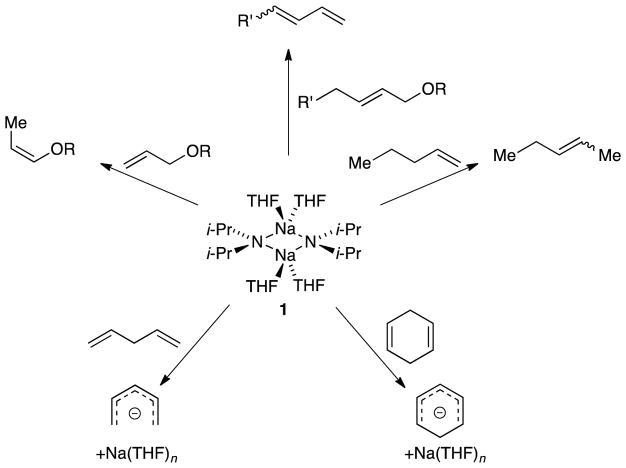

Scheme 1.

Summary of alkene and diene metalation with NaDA/THF.

Results

General

Stock solutions of 1.0 M NaDA in DMEA were prepared as described previously.7 (The importance of using fresh sodium dispersion cannot be overstated.) NaDA was crystallized from DMEA/hexane for spectroscopic and rate studies despite no evidence that this added precaution has a significant effect.8 Solutions of NaDA in neat DMEA containing >4.0 equiv of THF contained exclusively (>95%) THF solvate 1.8

The metalation and isomerization rates were monitored by following the alkene and diene absorbances using a combination of in situ IR9 and 1H NMR spectroscopies. Control experiments showed that DMEA and hexane could be used interchangeably as cosolvents without detectable changes in reactivity. The temperature for IR spectroscopy was controlled using baths comprising ice/water (0 °C), dry ice/acetone (−78 °C), liquid nitrogen/methanol (−95 °C), and liquid nitrogen/Et2O (−116 °C). The reproducibility of the latter two temperatures surprised us.

Rate studies were carried out at standard yet variable concentrations of NaDA (0.025–0.40 M) and THF (1.00–12.3 M) in either DMEA or hexane cosolvent, whereas the substrate concentrations were typically low (0.0050 M) to maintain pseudo-first-order conditions. Non-linear least-squares fits to the decays of the substrate afforded pseudo-first-order rate constants (kobsd). The method of initial rates was used when pseudo-first-order conditions were not rigorously established. Reactions with equimolar base and substrate showed no evidence of autocatalysis or autoinhibition.

1-Pentene Isomerization

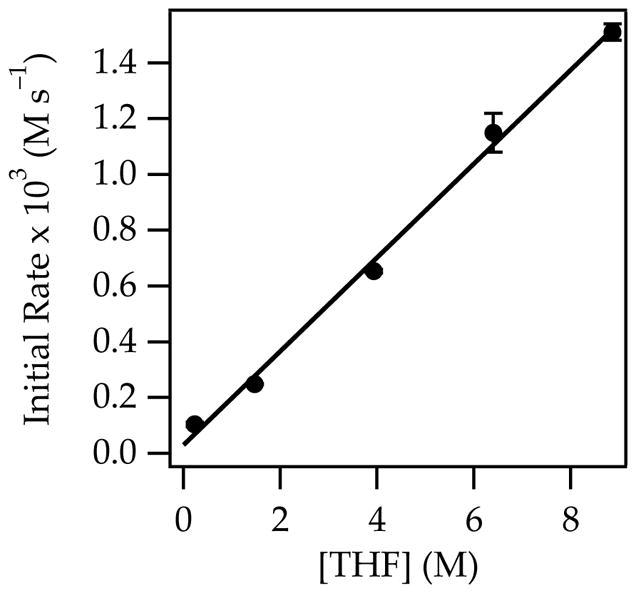

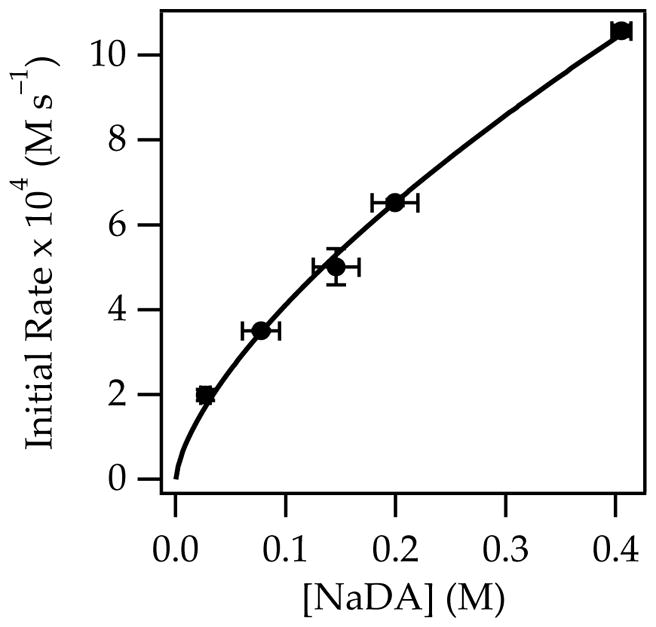

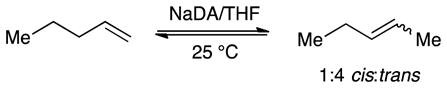

The metalation of 1-pentene with NaDA/THF to provide pentenyl sodium is endothermic. Nonetheless, facile isomerization of 1-pentene was observed in the presence of NaDA/THF at 25 °C via the presumed intermediacy of pentenyl sodium. Monitoring with 1H NMR spectroscopy showed an initial formation of 2-pentene as a 1:1 cis/trans mixture that slowly equilibrated to a 1:4 cis/trans mixture (eq 1; see Figure 1). The proportions of cis- and trans-2-pentene at early conversion were independent of THF and NaDA concentrations, confirming that both are formed via isomeric transition states. Plots of the initial rates for the loss of 1-pentene versus THF concentration (Figure 2) and NaDA concentration (Figure 3) revealed first- and half-order dependencies, respectively. The overall rate law described by eq 2 is consistent with a trisolvated-monomer-based transition structure, [A(THF)3]‡ (eqs 2 and 3; ‘A’ denotes a NaDA subunit).10

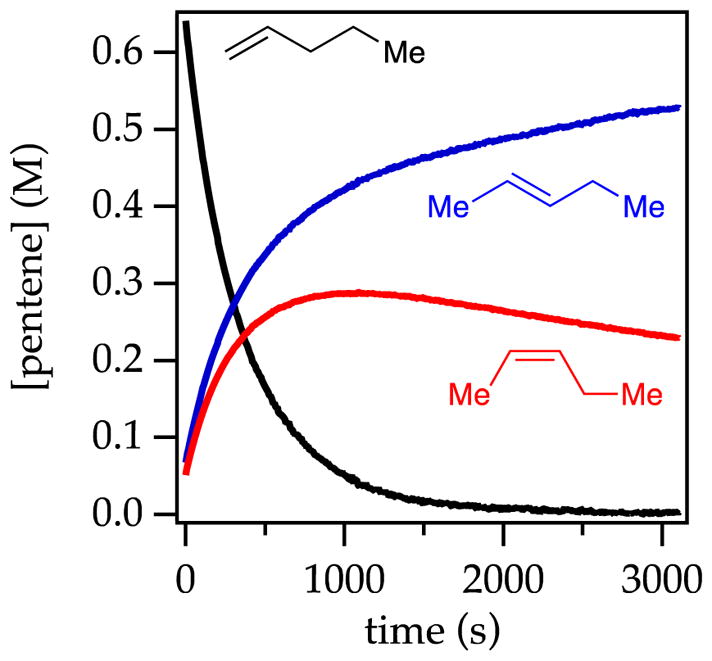

Figure 1.

Plot of alkene concentration versus time measured with 1H NMR spectroscopy for the isomerization of 0.76 M 1-pentene with 0.18 M NaDA and 0.59 M diisopropylamine in 8.83 M THF/hexane at 25 °C. The traces show 1-pentene (black), trans-2-pentene (blue), and cis-2-pentene (red) at partial equilibration.

Figure 2.

Plot of initial rates versus THF concentration for the isomerization of 0.76 M 1-pentene (eq 1) with 0.18 M NaDA and 0.59 M diisopropylamine in hexane cosolvent at 25 °C. The curve depicts an unweighted least-squares fit to the function f(x) = ax + b: a = 0.168 ± 0.006; b = 0.03 ± 0.03.

Figure 3.

Plot of initial rates versus NaDA concentration for the isomerization of 0.76 M 1-pentene (eq 1) with 0.59 M diisopropylamine in 3.93 M THF/hexane at 25 °C. The curve depicts an unweighted least-squares fit to the function f(x) = axb: a = 19.2 ± 0.8; b = 0.67 ± 0.03. Covariance is used because the NaDA titer was measured.

|

(1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

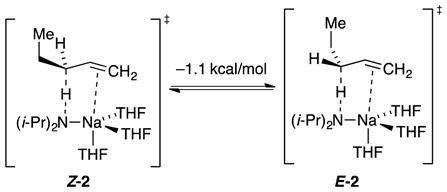

The reaction coordinate for metalation was examined using density functional theory (DFT) calculations at the B3LYP/6–31G(d) level of theory with single-point MP2 calculations.11 Transition structures Z-2 and E-2, affording cis- and trans-2-pentene, respectively, predicted a modest trans selectivity (eq 4) that was not borne out experimentally. A distinct π interaction between sodium and the developing allyl anion was visible in both cases.12

|

(4) |

Allyl Ether Isomerizations

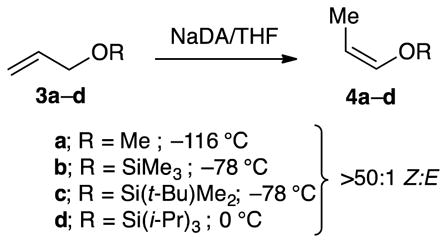

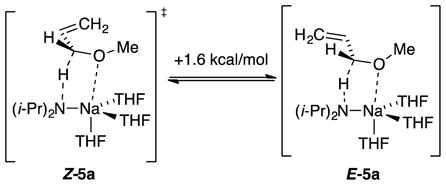

NaDA-mediated metalations of allyloxy ethers 3a–d are also endothermic, but the catalyzed isomerizations afforded enol ethers 4a–d13 in synthetically useful >50:1 Z:E selectivities (eq 5). Analogously selective isomerizations have been reported by Williard and co-workers14 using LDA/THF but are >1000-fold slower.15 Monitoring the isomerization of allyl methyl ether with NaDA in THF at −116 °C revealed a first-order THF dependence and half-order NaDA dependence (supporting information), which implicated a trisolvated-monomer-based metalation (eqs 6 and 7). DFT computations showed a strong preference for transition structure Z-5a relative to E-5a. Distinct methoxy–sodium interactions were observed in lieu of the allyl–sodium interactions observed with simple alkenes (eq 8). The energies were consistent with the Z selectivity.

|

(5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

|

(8) |

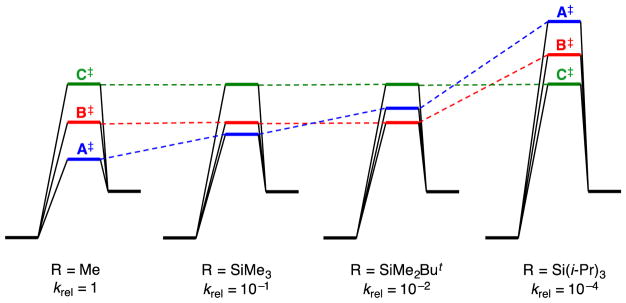

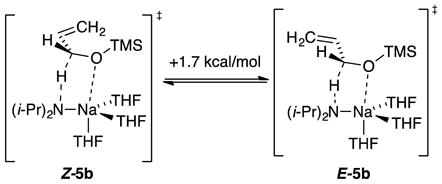

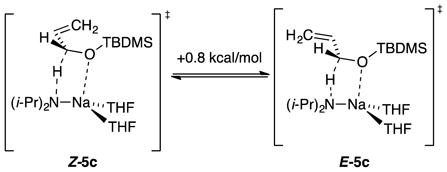

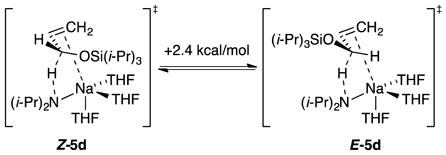

Trimethylsilyl groups are often suggested to suppress O–Li interactions owing to a combination of steric and electronic effects,16 and the tert-butyldimethylsilyl moiety is larger. Of course, this conventional wisdom gleaned largely from empirical evidence—even if true—may not apply to organosodium reagents. In the event, the highly Z-selective isomerizations (eq 5) occurred at the following approximate relative rates: R = methyl (1), trimethylsilyl (10−1), tert-butyldimethylsilyl (10−2), and triisopropylsilyl (10−4). Rate studies (supporting information) revealed that the trimethylsilyl ether isomerized at −78 °C via monomer-based transition structure [A(THF)3(3b)]‡, which is analogous to that for the isomerization of allyl methyl ether; the high Z preference is reflected in eq 9. A small non-zero intercept was consistent with [A(THF)2(3b)]‡. The tert-butyldimethylsilyl ether isomerized at −78 °C and was shown kinetically to occur via a disolvated monomer, [A(THF)2(3c)]‡, while retaining a high Z preference supported computationally (eq 10). Given that the loss of primary shell solvation is typically endothermic by >5 kcal/mol, the rate reduction is surprisingly muted. The triisopropylsilyl ether isomerized at 0 °C and was shown kinetically to metalate via trisolvated monomer [A(THF)3(3d)]‡ while retaining the Z selectivity observed experimentally and supported computationally (eq 11). We return to the role of stereoelectronic control and changing solvation numbers in the discussion.

|

(9) |

|

(10) |

|

(11) |

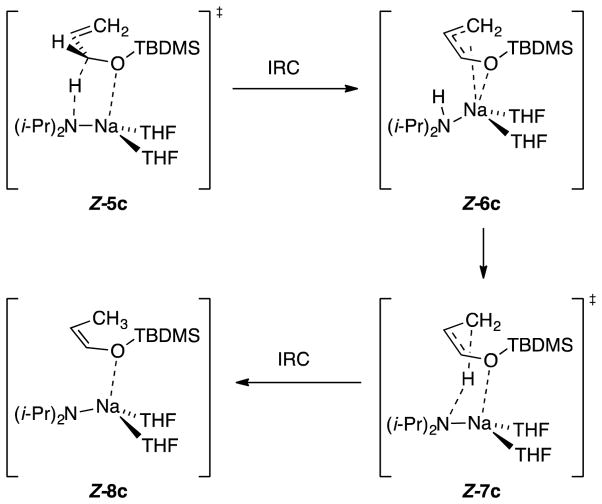

Isomerization of allyloxy-tert-butyldimethylsilane 3c using NaDA in neat THF containing 3 equiv of (i-Pr)2N–D with monitoring by 1H NMR spectroscopy showed <20% deuterium incorporation in Z-4c, indicating that the proton transfer is intramolecular. The sequence in Scheme 2 is computationally viable. The Na–N contact stretches to ~3.5 Å computationally en route to Z-8c while the proton reorients toward the allyl anion terminus.

Scheme 2.

Intramolecular proton transfer in allyloxy to enol ether conversion.

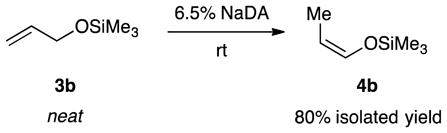

Isomerization: Catalysis

The isomerizations described above, although carried out stoichiometrically in the rate studies, were inherently catalytic in NaDA. The simplicity of a catalytic protocol is illustrated in eq 12. Treatment of neat allyloxytrimethylsilane with 6.5% NaDA monitored with 1H NMR spectroscopy showed quantitative conversion to 4b in 30–60 seconds at room temperature. Compared with other protocols, this preparation is a remarkably simple one for a useful synthon.14,17

|

(12) |

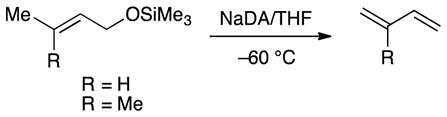

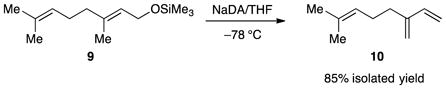

Allyloxy 1,4-Eliminations

The high Z selectivity for allyl ether isomerization prompted us to examine substituted allyl ethers as putative substrates, but 1,4-eliminations intervened (eqs 13 and 14) to the exclusion of isomerization. The volatile alkenes in eq 13 were formed cleanly as shown by 1H NMR spectroscopy. Myrcene (10) was isolated pure in excellent yield.

|

(13) |

|

(14) |

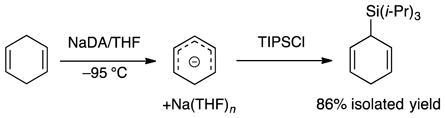

Diene Metalations

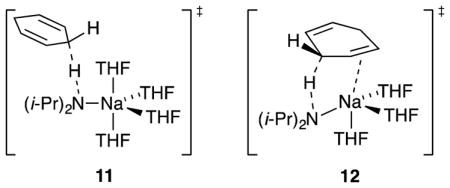

1,4-Dienes are sufficiently acidic to metalate exothermically with NaDA in THF (eq 15) and afford synthetically useful dienyl sodiums at rates that outpace those of alternative deprotonations with BuLi/TMEDA and LDA/THF. Monitoring the reaction of 1,4-cyclohexadiene with NaDA in 2.0–10 M THF at −95 °C showed a loss of substrate (1642 cm−1) and the formation of the cyclohexadienyl sodium (1558 cm−1). The transformation was confirmed by trapping the resulting sodium salt with TIPSCl.7 Rate studies using IR spectroscopy (supporting information) showed a first-order dependence on diene, half-order dependence on NaDA, and second-order dependence on THF (eq 16) consistent with a tetrasolvated-monomer-based transition structure as depicted in eq 17. Although the A(THF)4 fragment in isolation was computationally viable, attempts to calculate 11 consistently led to the extrusion of a THF ligand, which afforded trisolvate 12 displaying a distinct π-allyl sodium interaction. Rate studies of the metalation of 1,4-pentadiene revealed an entirely analogous [A(THF)4·(diene)]‡ stoichiometry and a π-bonded [A(THF)3·(diene)]‡ transition structure computationally (supporting information). Attempted metalations of 1,3-cyclohexadiene appeared to afford polymer under relatively forcing conditions (0 °C) as might be expected.18

|

(15) |

| (16) |

| (17) |

Discussion

The first paper in this series promulgated NaDA/DMEA as an easily prepared, effective Brønsted base that compares favorably to LDA/THF.7 A second paper described detailed structural studies of NaDA in various standard coordinating solvents8 as a foundation for the current mechanistic study and those that will follow. The temptation to rely on analogies of sodium amides to lithium amides owing to decades of experience is fraught with risk.19 Parallel behaviors of lithium and sodium do exist, but they are imperfect and require experimental support. The mechanistic studies described herein begin to examine the relationships among organosodium aggregation, solvation, reactivity, mechanism, and selectivity.

The current study probed a combination of the synthetic utility and underlying mechanism of NaDA/THF-mediated reactions of alkenes and dienes. NaDA cleanly and rapidly metalates 1,4-dienes, whereas synthetic chemists often resort to using potentially more destructive alkyllithiums.20,21 By contrast, metalations of simple alkenes and allyloxy ethers are endothermic, yet facile isomerizations underscore synthetic opportunities and provide an opportunity to study fundamental principles of sodium coordination chemistry.

Diene Metalation

NaDA metalates 1,4-cyclohexadiene and 1,4-pentadiene to form dienylsodiums rapidly and quantitatively. Both react via tetrasolvated monomers; transition structure 11 is emblematic. 1,4-Cyclohexadiene reacts approximately 10-fold slower than 1,4-pentadiene, presumably owing to unproductive substituents as well as the suboptimal alignment of the C–H bond with the π system. Tetrasolvation in the rate-limiting transition structures contrasts with the trisolvation observed with alkene isomerizations.

The synergies of kinetics and computations offer excellent opportunities to test theory–experiment correlations, which is crucial for our fledgling studies of sodium amides. In this case, however, the correlation proved imperfect: all attempts to find tetrasolvated transition structure 11 afforded trisolvate 12, which resulted from the extrusion of a THF ligand with the formation of a π-allyl sodium interaction. It is plausible that the transition structure includes four solvents (demonstrated kinetically) and the π interaction predicted computationally. DFT often fails to replicate highly solvated lithiums.22

1-Pentene Isomerization

Despite the inherent endothermicity of alkene metalations, mechanistic details were obtained from studies of the isomerization of 1-pentene to cis- and trans-2-pentenes (eq 1). The kinetic formation of both stereoisomers in equal proportions is followed by a slower stereochemical equilibration (Figure 1). Rate studies showing trisolvated-monomer-based transition structures are supported by computational studies showing Z-2 and E-2 transition structures manifesting distinct π-allyl sodium interactions. A predicted kinetic preference for E-2 is not observed experimentally. As noted by a referee, the results seem to be at odds with thermodynamic preferences for the Z allyl sodiums,24c but that is not surprising for kinetic versus thermodynamic control. The observed equilibration, of course, is for the alkenes rather than the allyl sodiums.

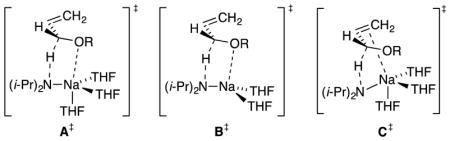

Allyloxy Isomerizations: Mechanistic Chameleons

The series of NaDA/THF-mediated allyl ether (CH2=CHCH2OR) isomerizations (eq 5) constitutes the most interesting portion of this study both synthetically23 and mechanistically. Rates of isomerization correlate with apparent steric effects following the order R = Me > SiMe3 > Si(t-Bu)Me2 > Si(i-Pr)3. The underlying mechanistic differences, however, are far more nuanced (eqs 8–11). Methyl and SiMe3 moieties are essentially interchangeable, reacting via a trisolvated-monomer-based transition structure depicted generically as A‡ with prominent Na–O interactions to the exclusion of Na–C π-allyl contacts. The decidedly larger Si(t-Bu)Me2 group metalates significantly more slowly via a disolvated monomer, B‡, while retaining the putative Na–O contact. The notoriously large Si(i-Pr)3 (TIPS) moiety blocks the Na–O contact, replacing it with an Na–C π-allyl interaction, which allows it to return to a trisolvated monomer (C‡).

Scheme 3 offers an alternative perspective on the interplay among allyloxy RO–Na coordination, steric bulk, and solvation number. We have taken the liberty of normalizing the energies of the reactants to a common level. Transition structures A‡, B‡, and C‡ are color-coded. Moving from left to right reflects increasing steric demand and decreasing relative rate constants (krel). The energy of A‡, which is stabilized by both trisolvation and a Na–O contact with the allyloxy fragment, is sterically sensitive. The intermediate steric demand of the Si(t-Bu)Me2 moiety sacrifices a stabilizing Na–THF interaction to retain the Na–O contact with the allyloxy. In the limit of high steric demand, the Na–O contact is inaccessible, which reveals the inferior Na–C contact (C‡) while returning to trisolvation. Transition structure C‡ is insensitive to the steric demands of the R group, which make it dominant by default for the TIPS ether.

Scheme 3.

Qualitative barriers for the isomerization of allyloxy ethers via differing transition structures.

Allyloxy Isomerization: Origin of Z Selectivity

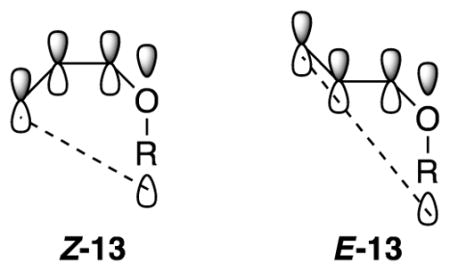

The contrasteric isomerization of allyl ethers to provide Z-(1-propenyl) ethers (eq 5) tempts us to invoke a privileged role for NaDA in this transformation, but Z-selective isomerizations have been noted with t-BuOK/DMSO17 and LDA/THF.14 An overlay of the computed pro-Z and pro-E transition structures (Z-5 and E-5, respectively) reveals complete superposition of the A(THF)3 fragment, with the sole distinction being the terminal methylene orientation. Given that transition states 5a–d are product-like in accord with the Hammond postulate, we directed our attention toward stereoelectronic preferences endemic to the putative allylsodium intermediate. Geometric preferences within this class of allyl anions have been addressed both experimentally24 and computationally.25 Compared with E-11, Z-11 shows a greater spatial overlap—and consequent stabilization—of the allyl anion π manifold with the O–R σ* orbital. The transition-state energy differences cited in eqs 8–11 are reflected in the calculated relative energies of allyl anions Z-13 and E-13 and are consistent with this highly simplified, purely stereoelectronic model.26

Conclusion

NaDA/THF observably metalates dienes and transiently metalates alkenes and allyloxy ethers. The NaDA-mediated isomerization of 1-pentene shows no stereoselectivity. By contrast, the >50:1 Z-selective isomerization of allyl ethers is synthetically noteworthy. Rate and computational data revealed the roles of solvation and aggregation, which are key for understanding organosodium coordination chemistry. The current investigation reinforces our enthusiasm for NaDA to effect difficult metalations that plague synthetic chemists. That it can be prepared as stock solutions in trialkylamines in minutes using standard glassware and stored for months with refrigeration amplifies its appeal.7

Experimental

Reagents

NaDA was prepared from diisopropylamine, isoprene, and sodium dispersion by using a modified7 procedure first reported by Wakefield.3a Despite little evidence of improved efficacy, NaDA was crystallized from DMEA/hexane as an added measure.8 THF, hexane, and DMEA were vacuum-transferred from purple solutions of sodium benzophenone ketyl. Air- and moisture-sensitive materials were manipulated under argon using standard glovebox, vacuum line, and syringe techniques. The substrates were commercially available or prepared with standard protocols.27

IR Spectroscopic Analyses

IR spectra were recorded using an in situ IR spectrometer fitted with a 30-bounce, silicon-tipped probe. The spectra were acquired in 16 scans at a gain of 1 and a resolution of 4 cm−1. A representative reaction was carried out as follows: The IR probe was inserted through a nylon adapter and O-ring seal into an oven-dried, cylindrical flask fitted with a magnetic stir bar and a T-joint. The T-joint was capped with a septum for injections and a nitrogen line. After evacuation under full vacuum, heating, and flushing with nitrogen, the flask was charged with NaDA (62 mg, 0.50 mmol) in THF/DMEA (4.9 mL) and cooled in a dry ice–acetone bath prepared with fresh acetone. After a background spectrum was recorded, ether 3b (0.050 mmol) was added with stirring. For the most rapid reactions, IR spectra were recorded every 6 s with monitoring of the absorbance at 1510 cm−1 over the course of the reaction.

NMR Spectroscopy

All samples for reaction monitoring and structure elucidation were prepared using stock solutions and sealed under partial vacuum. Standard 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded at 500 and 125.79 MHz, respectively.

Myrcene (10)

To a stirred solution of NaDA (500 mg, 4.06 mmol) in THF (15 mL) at −78 °C was added geraniol trimethylsilyl ether 9 (836 mg, 3.70 mmol). After 5 h at −78 °C, the reaction was quenched with water and partitioned between water and pentane. The crude extract was chromatographed on silica with pentane (Rf = 0.5) and the fractions were concentrated to afford myrcene (428 mg, 85% yield) identical to that reported in the literature (1H and 13C NMR).28

Enol ether 4b: neat isomerization

To a NMR tube charged with solid NaDA (71 mg, 0.58 mmol) was added neat allyloxytrimethylsilane (1.5 mL, 8.9 mmol) at room temperature. After 1 minute, the crude reaction mixture was vacuum-transferred to a receiving flask cooled with dry ice–acetone to provide 0.982 g (84% yield) of product enol ether 4b contaminated by ~5% diisopropylamine.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health (GM039764) for support.

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supporting Information: Spectroscopic, kinetic, and computational data and authors for reference 11. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References and Footnotes

- 1.Raynolds S, Levine R. J Am Chem Soc. 1959;82:472. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Lochmann L, Janata M. Eur J Chem. 2014;12:537. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lochmann L. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2000:1115. [Google Scholar]; (c) Lochmann L, Trekoval J. J Organomet Chem. 1979;179:123. [Google Scholar]; (d) Lochmann L, Pospíšil J, Lím D. Tetrahedron Lett. 1966;2:257. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Barr D, Dawson AJ, Wakefield BJ. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1992;204:9. [Google Scholar]; (b) Andrews PC, Barnett NDR, Mulvey RE, Clegg W, O’Neil PA, Barr D, Cowton L, Dawson AJ, Wakefield BJ. J Organomet Chem. 1996;518:85. [Google Scholar]; (c) Munguia T, Bakir ZA, Cervantes-Lee F, Metta-Magana A, Pannell KH. Organometallics. 2009;28:5777. [Google Scholar]; (d) Boeckman RK, Boehmler DJ, Musselman RA. Org Lett. 2001;3:3777. doi: 10.1021/ol016738i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) LaMontagne MP, Ao MS, Markovac A, Menke JR. J Med Chem. 1976;19:363. doi: 10.1021/jm00225a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Bond JL, Krottinger D, Schumacher RM, Sund EH, Weaver TJ. J Chem Eng Data. 1973;18:349. [Google Scholar]; (g) Levine R, Raynolds S. J Org Chem. 1960;25:530. [Google Scholar]; (h) Mamane V, Louërat F, Iehl J, Abboud M, Fort Y. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:10699. [Google Scholar]; (i) Baum BM, Levine R. J Heterocyclic Chem. 1966;3:272. [Google Scholar]; (j) Tsuruta T. Makromol Chem. 1985;13:33. [Google Scholar]; (k) Andrikopoulos PC, Armstrong DR, Clegg W, Gilfillan CJ, Hevia E, Kennedy AR, Mulvey RE, O’Hara CT, Parkinson JA, Tooke DM. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:11612. doi: 10.1021/ja0472230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Zhao P, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:4008. doi: 10.1021/ja021284l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lucht BL, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:2217. [Google Scholar]; (c) Remenar JF, Lucht BL, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:5567. [Google Scholar]; (d) Bernstein MP, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:8008. [Google Scholar]; (e) Godenschwager P, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:8726. doi: 10.1021/ja800250q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mulvey RE, Robertson SD. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2013;52:11470. doi: 10.1002/anie.201301837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.For an interesting historical perspective on organoalkali metal chemistry, see: Seyferth D. Organometallics. 2006;25:2.Seyferth D. Organometallics. 2009;28:2.

- 7.Ma Y, Algera RF, Collum DB. J Org Chem. 2016;81:11312. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b02287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Algera RF, Ma Y, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:7921. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b03061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Rein AJ, Donahue SM, Pavlosky MA. Curr Opin Drug Discov Dev. 2000;3:734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Connolly TJ, Hansen EC, MacEwan MF. Org Process Res Dev. 2010;14:466. [Google Scholar]

- 10.The rate law provides the stoichiometry of the transition structure relative to that of the reactants: Edwards JO, Greene EF, Ross J. J Chem Educ. 1968;45:381.

- 11.Frisch MJ, et al. GaussianVersion 3.09 revision A.1. Gaussian, Inc; Wallingford, CT: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haeffner F, Houk KN, Schulze SM, Lee JK. J Org Chem. 2003;68:2310. doi: 10.1021/jo0268761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Compound 4a: Leung DH, Bergman RG, Raymond KN. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:2746. doi: 10.1021/ja068688o.Compound 4b: Heathcock CH, Buse CT, Kleschick WA, Pirrung MC, Sohn JE, Lampe J. J Org Chem. 1980;45:1066.Compound 4c: Su C, Williard PG. Org Lett. 2010;12:5378. doi: 10.1021/ol102029u.Compound 4d: Guha SK, Shibayama A, Abe D, Sakaguchi M, Ukaji Y, Inomata K. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 2004;77:2147.

- 14.Su C, Williard PG. Org Lett. 2010;12:5378. doi: 10.1021/ol102029u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The acceleration was estimated assuming a factor 2 per 10 °C with the adjustment for the relative rates. This is likely to be an underestimate.

- 16.(a) Hattori K, Yamamoto H. J Org Chem. 1993;58:5301. [Google Scholar]; (b) Rücker C. Chem Rev. 1995;95:1009. [Google Scholar]; (c) Williard PG, Hintze MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:5539. [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Taskinen E. Tetrahedron. 1993;48:11389. [Google Scholar]; (b) J Am Chem Soc. 1961;83:1701. [Google Scholar]; (c) Martinez-Erro S, Sanz-Marco A, Gómez AB, Vázquez-Romero A, Ahlquist MSG, Martín-Matute B. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:13408. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b08350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsieh HL, Quirk RP. Anionic Polymerization: Principles and Practical Applications. Marcel Dekker; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collum DB, McNeil AJ, Ramírez A. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:3002. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Simonneau A, Oestreich M. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2013;52:11905. doi: 10.1002/anie.201305584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fujioka H, Sawama Y, Kotoku N, Ohnaka T, Okitsu T, Murata N, Kubo O, Li R, Kita Y. Chem–Eur J. 2007;13:10225. doi: 10.1002/chem.200700871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Landais Y, Zekri E. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:6547. [Google Scholar]

- 21.It appears to be unreported, but 1,4-dienes can be metalated with LDA. Literature procedures use alkyllithiums.17

- 22.Reyes-Rodríguez GJ, Algera RF, Collum DB. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:1233. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b11354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stereocontrolled silyl enol ethers are synthetically important: Denmark SE, Ghosh SK. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2001;40:4759. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011217)40:24<4759::aid-anie4759>3.0.co;2-g.Lim SM, Hill N, Myers AG. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:5763. doi: 10.1021/ja901283q.Wang X, Meng Q, Nation AJ, Leighton JL. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:10672. doi: 10.1021/ja027655f.Schumacher R, Reissig HU. Synlett. 1996:1121.

- 24.(a) Taskinen E. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans. 2;2001:1824. [Google Scholar]; (b) Bank S, Schriesheim A, Rowe CA. J Am Chem Soc. 1965;87:3244. [Google Scholar]; (c) Haag WO, Pines H. J Am Chem Soc. 1960;82:387. [Google Scholar]; (c) Schleyer PvR, Kante J, Yun-Dong W. J Organometal Chem. 1992;426:143. [Google Scholar]

- 25.(a) Mangelinckx S, Giubellina N, De Kimpe N. Chem Rev. 2004;104:2353. doi: 10.1021/cr020084p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Schleyer PvR, Dill JD, Pople JA, Hehre WJ. Tetrahedron. 1977;33:2497. [Google Scholar]

- 26.This stereoelectronic model rationalizes the outcome of 1-pentene isomerization, for which poorer overlap of the allyl anion π manifold with C–H(C) σ* results in minimal disproportionate stabilization and consequent stereorandom isomerization.)

- 27.De Carvalho ME, Meunier B. Nouv J Chim. 1986;10:223. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Myrcene is commercially available with 1H and 13C NMR spectra reported by Sigma-Aldrich.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.