Abstract

Neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA) comprises a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized by the presence of radiologically discernible high brain iron, particularly within the basal ganglia. A number of childhood NBIA syndromes are described, of which two of the major subtypes are pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration (PKAN) and PLA2G6-associated neurodegeneration (PLAN). PKAN and PLAN are autosomal recessive NBIA disorders due to mutations in PANK2 and PLA2G6, respectively. Presentation is usually in childhood, with features of neurological regression and motor dysfunction. In both PKAN and PLAN, a number of classical and atypical phenotypes are reported. In this chapter, we describe the clinical, radiological, and genetic features of these two disorders and also discuss the pathophysiological mechanisms postulated to play a role in disease pathogenesis.

1. INTRODUCTION

Neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA) comprises a heterogeneous group of disorders characterized clinically by progressive motor dysfunction, with evidence of radiologically discernible brain iron, particularly within the basal ganglia. A number of NBIA phenotypes are reported (Gregory & Hayflick, 2013), including pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration (PKAN) (Gregory & Hayflick, 2002), PLA2G6-associated neurodegeneration (PLAN) (Gregory, Kurian, Maher, Hogarth, & Hayflick, 2008), mitochondrial membrane protein-associated neurodegeneration (MPAN), and the newly described beta propeller-associated neurodegeneration (BPAN). Most of the major NBIA subtypes of childhood (PKAN/PLAN/MPAN) are autosomal recessive disorders, except BPAN, which shows an X-linked pattern of inheritance. In this overview, we will focus on the clinical phenotypes, radiological features, pathological findings, disease mechanisms, and management strategies in PKAN and PLAN. Together, these two NBIA subtypes account for approximately two-thirds of patients with childhood onset disease. Increasingly, adult phenotypes caused by these genes are recognized (Schneider & Bhatia, 2010).

2. PANTOTHENATE KINASE-ASSOCIATED NEURODEGENERATION

First described as a clinical syndrome in 1924 (Hallervorden, 1924), PKAN was originally known as Hallervorden–Spatz syndrome (HSS) (Dooling, Schoene, & Richardson, 1974), but in view of the unethical activities of these German neuropathologists before and during the second World War (Shevell, 2003), the syndrome was renamed PKAN, the new acronym clearly reflecting the underlying genetic cause of this disease. PKAN is a major form of NBIA accounting for approximately 50% of childhood NBIA. It has an estimated prevalence of 1–3/million (Gregory, Polster, & Hayflick, 2009) with a general population carrier frequency of 1/275–500. PKAN is typically characterized by the onset of progressive neurological symptoms in association with a characteristic pattern of basal ganglia iron deposition. The allelic disorder, hypobetalipoproteinaemia, acanthocytosis, retinitis pigmentosa, and pallidal degeneration (HARP) syndrome, is also caused by PANK2 mutations and is considered part of the PKAN phenotypic spectrum (Ching, Westaway, Gitschier, Higgins, & Hayflick, 2002; Gregory et al., 2009; Houlden et al., 2003).

2.1. Clinical presentation

2.1.1 Onset of clinical symptoms

Classic PKAN

75% of PKAN cases have a classic phenotype (childhood onset disease and faster disease progression), whereas the remainder of patients present with “atypical PKAN” (disease onset in the second or third decade of life, slower progression of disease). Classical PKAN will usually clinically present before age 6 years (mean age 3.4 years) in the majority of patients, but there is some variability (6 months–12 years). Some affected children often have a history of nonspecific features prior to presentation, including clumsiness, dyspraxia, and motor/global neurodevelopmental delay (Gregory & Hayflick, 2002). Early clinical features are commonly gait abnormalities and postural instability, which result from a combination of lower-limb spasticity, dystonia, and rigidity. Visual symptoms may be the presenting feature of PKAN. Toe walking and upper body dystonia are less common presenting signs.

Atypical PKAN

In contrast, patients with atypical PKAN present at a mean age of 14 years (range 1–28 years) (Hartig et al., 2006; Hayflick et al., 2003), often with speech difficulties (palilalia or dysarthria), mild gait disturbance with subtle dystonia, or neuropsychiatric features.

2.1.2 Clinical disease features

Classic PKAN

The clinical features of classic PKAN are remarkably homogeneous between patients. In classical PKAN, dystonia is always reported and it is the most common extrapyramidal feature. Dystonia can affect any part of the body but is often very prominent in the limbs and face. The majority of PKAN patients have oromandibular dystonia and dysarthria (Hartig et al., 2006). Cranial dystonia may lead to recurrent tongue trauma, in some cases requiring full-mouth dental extraction (Gregory & Hayflick, 2002). Limb dystonia can lead to long bone fracture, where extreme bone stress (from severe dystonia) and osteopenia (from reduced mobility) are contributory risk factors. Other motor phenotypes such as choreoathetosis, rigidity, and parkinsonism are rarely described. Pyramidal tract features are also reported, resulting in upper motor neuron signs of hypertonicity, hyperreflexia, and spasticity. Seizures are rarely reported in this group of patients.

Two-thirds of patients with classical PKAN (Hayflick et al., 2003) demonstrate a pigmentary retinopathy, which can lead to significant visual impairment (Hayflick et al., 2003). Clinical symptoms include nyctalopia with subsequent progressive loss of peripheral visual fields and sometimes eventual blindness. Abnormal vertical saccades and saccadic pursuits are reported. Sectoral iris paralysis and partial loss of the pupillary ruff in keeping with bilateral Adie’s pupil (Egan et al., 2005) are also reported. Early changes on funduscopic examination include a flecked appearance to the retina, and later in the disease course, there is evidence of bone spicule formation, prominent choroidal vasculature, and “bull’s-eye” annular maculopathy. The pigmentary retinopathy is thought to occur early in the disease course and requires a full ophthalmologic diagnostic evaluation including electroretinogram (ERG) and visual field testing for accurate diagnosis. Of note, individuals with a normal ophthalmologic examination at initial diagnosis generally tend not to develop retinopathy later.

As well as motor and visual symptoms, patients also develop cognition dysfunction with progressive disease, although there is much variability in severity (Freeman et al., 2007). Age of PKAN disease onset had a strong inverse correlation with intellectual impairment (Freeman et al., 2007). More recent data suggest that due to the practical difficulties in performing cognitive testing in those with PKAN (because the severity of their motor impairments limits what cognitive assessments can be performed), cognitive decline may be overestimated in PKAN patients (Mahoney, Selway, & Lin, 2011). Acanthocytosis is evident in 8% of affected individuals.

Atypical PKAN

There are clearly defined differences in the main clinical features observed in typical PKAN compared to atypical PKAN. In atypical PKAN, one-third of patients have neuropsychiatric manifestations including behavioral difficulties and vocal and motor tics (Scarano, Pellecchia, Filla, & Barone, 2002), obsessions, obsessive–compulsive disorder, aggression, change in personality, emotional lability, impulsivity, depression, a frontotemporal-like dementia early in their disease (Pellecchia et al., 2005), and, rarely, psychotic symptoms (del Valle-López, Pérez-García, Sanguino-Andrés, & González-Pablos, 2011; Pellecchia et al., 2005). Speech abnormalities are common and include palilalia, tachylalia/tachylogia, and dysarthria (Benke & Butterworth, 2001; Benke, Hohenstein, Poewe, & Butterworth, 2000). Like in classical PKAN, many atypical PKAN patients develop motor features later in their disease course. Indeed, retrospective history taking reveals that some have an early history of clumsiness in childhood or adolescence. Dystonia is the most common extrapyramidal feature in atypical PKAN, although it is generally perceived to be less severe than that seen in classical PKAN (Hayflick et al., 2003). Other motor symptoms are also reported in atypical PKAN, including parkinsonism (Zhou et al., 2001), adult-onset pure akinesia (Molinuevo, Marti, Blesa, & Tolosa, 2003), focal dystonias (Zhou et al., 2001), corticospinal tract signs, freezing of gait (Guimaraes & Santos, 1999), and an essential tremor-like syndrome (Yamashita et al., 2004). Retinitis pigmentosa is only rarely described in atypical disease, although recent literature suggests that subclinical retinal changes may be more common than previously thought in the atypical PKAN subgroup. Optic atrophy is not associated with atypical phenotype. Similar to classical PKAN, cognitive impairment is also reported in late-onset PKAN phenotype (Freeman et al., 2007).

2.1.3 Disease course

PKAN is a disorder of neuroregression, and lost skills are not regained. The rate of disease progression seems to be faster in patients with earlier disease onset. Patients with PKAN show a pattern of stepwise decline, with periods of relative clinical stability combined with episodic neurological deterioration, cognitive decline, and loss of motor skills. The reason for this stepwise pattern of regression is unclear, and there seems to be no correlation with intercurrent infection or illness (Gregory & Hayflick, 2013). Loss of ambulation is seen in the majority of patients with classical disease within 10–15 years of diagnosis (Hartig et al., 2006; Hayflick et al., 2003). Secondary complications are commonly encountered including gut-related symptoms, such as gastroesophageal reflux, dysphagia, and constipation. Premature death does occur, but advances in medical care have resulted in a greater number of PKAN patients surviving into adulthood. Death is usually secondary to (i) cardiorespiratory complications (chest infections and aspiration pneumonia) and (ii) complications from malnutrition (such as immunodeficiency) and rarely associated with (iii) status dystonicus. Atypical PKAN appears to be less aggressive than classic disease, and most individuals remain ambulant into adulthood, with loss of ambulation occurring over a longer timescale, usually within 15–40 years of disease onset.

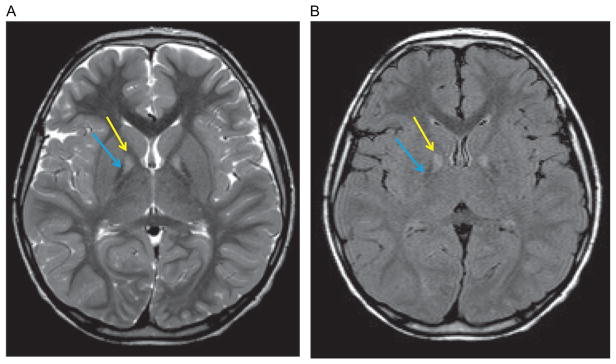

2.2. Neuroimaging features in PKAN (Fig. 2.1)

Figure 2.1.

Radiological features of PKAN on brain MRI. Axial T2 (A) and axial FLAIR (B) images indicating the “eye-of-the-tiger” sign with medial globus pallidus hyperintensity (yellow arrow) surrounded by a region of hypointensity (blue arrow).

As for all forms of NBIA, brain MRI is the neuroimaging modality of choice for the diagnostic evaluation of suspected PKAN. The characteristic feature on neuroimaging is the “eye-of-the-tiger” sign defined as a central area of hyperintensity within a hypointense globus pallidus on coronal or axial T2-weighted imaging. Some patients with PKAN may also have additional hypointensity indicative of iron deposition within the substantia nigra (McNeill et al., 2008). The PKAN “eye-of-the-tiger signature” is highly predictive for at least one mutation in PANK2 (Ching et al., 2002; Guimaraes & Santos, 1999). In addition, MRI has accurately predicted PKAN in presymptomatic siblings (Hayflick et al., 2001). Although the majority of patients with PANK2 mutations have the classical “eye-of-the-tiger” sign, it is not universally present in every patient for a number of reasons: (i) imaging may have been undertaken too early in the disease course (Chiapparini et al., 2011); (ii) in more advanced disease, the region of hyperintensity is replaced by a more uniform hypointensity from increasing iron accumulation (Baumeister, Auer, Hortnagel, Freisinger, & Meitinger, 2005; Delgado et al., 2012); and (iii) specific PANK2 mutations may be associated with features of NBIA on neuroimaging without classical “eye-of-the-tiger,” such as is evident in a subset of the cohort of PKAN patients from the Dominican Republic (Delgado et al., 2012). Of note, appearances similar to the “eye-of-the-tiger” sign are also observed in other NBIA disorders including MPAN, where MRI indicates iron within the globus pallidus and hyperintense streaking of the medial medullary lamina (Hogarth et al., 2013). “Eye-of-the-tiger” may also be seen in multiple system atrophy (Strecker et al., 2007), neuroferritinopathy (McNeill et al., 2008), and progressive supranuclear palsy (Hartig et al., 2006).

2.3. Neuropathological features of PKAN

Before the modern era of high-resolution MR imaging, NBIA disorders were diagnosed on postmortem examination, which showed iron-rich rust-brown pigmentation within the globus pallidus and substantia nigra (Hallervorden, 1924). More recently, post-gene discovery, there have been studies providing further insight into the neuropathologic features of PKAN (Kruer et al., 2011). The globus pallidus is the most affected structure, with depletion of viable neurons within the globus pallidus interna. Iron, mainly as coarse granular hemosiderin deposits, is distributed in a perivascular pattern. Spheroids (swollen axons) are also seen (Koeppen & Dickson, 2001) in the pallidonigral system and also in the cerebrum (Swaiman, 2001). Large spheroid structures (degenerating neurons) stain for ubiquitin and smaller axonal spheroids are positive for amyloid precursor protein detected by immunoreactivity, with less anti-ubiquitin staining (Kruer et al., 2011; Malandrini et al., 1995). Li et al. (2012) report postmortem findings from a single case (20-year-old male) with significant tau pathology (neurofibrillary tangles and neuropil threads).

2.4. Molecular genetics of PKAN

In 2001, Zhou et al. (2001) demonstrated that PKAN was caused by mutations in the PANK2 gene. PKAN is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner, and for genetic counseling purposes, recurrence risk at conception for each subsequent sibling of an affected individual with PKAN has (i) 1 in 4 chance of being affected with PKAN, (ii) 1 in 2 chance of being an asymptomatic carrier, and (iii) 1 in 4 chance of being an unaffected non-carrier. From a practical perspective, carrier testing for at-risk relatives, prenatal testing for future at-risk pregnancies, and preimplantation genetic diagnosis are all possible if both disease-causing mutations have been identified in an affected family member.

To date, mutations have been identified in all coding regions of the PANK2 gene (Hartig et al., 2006; Hayflick et al., 2003). A wide variety of mutations have been reported but most PANK2 mutations are missense variants distributed across the conserved domains of PANK2. Globally, the c.1561G>A missense mutation is the most common cause of PKAN, and many PKAN patients with this mutation have a shared haplotype, suggested of an ancestral founder effect. Mutation founder effects have been reported in specific populations including in the Netherlands (Rump et al., 2005) and also in a small isolated community from the Dominican Republic (c.680A>G, p.Tyr227Cys), where there is a significant increase in c.680A>G carrier frequency (Delgado et al., 2012).

Other more commonly identified mutations include c.1351C>T and c.1583C>T. Many rarer PANK2 variants have also been identified, and mutations “private” to individual families have been reported. In about 5–10% of cases, only one mutated allele can be detected. Some of these cases are resolved with gene dosage analysis by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) or exon-level array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH), where a second mutation is detected as an intragenic deletion or duplication. Mutations in the promoter, regulatory, or intronic regions (which cannot be detected on standard diagnostic testing) may also account for some of these unresolved “single mutation” cases.

Genotype–phenotype correlations for PKAN are still emerging, and certain patterns are already reported. Patients with 2 null mutations (resulting in absent PANK2 enzyme) consistently have the classical early-onset phenotype. Homozygotes of c.1561G>A missense mutation have classic PKAN. A recent study of PANK2 mutations confirmed that p.Gly521Arg leads to a protein that is misfolded and devoid of activity (Zhang, Rock, & Jackowski, 2006). Homozygosity of other alleles seems not to be so clearly predictive of phenotype. Intrafamilial disease variation in families with multiple affected members is more evident in families with atypical rather than classical PKAN.

2.5. Pathophysiological disease mechanisms in PKAN

PANK2 encodes a predicted 50.5 kDa protein that is a functional pantothenate kinase (Zhou et al., 2001). PKAN is attributed to loss of function of pantothenate kinase 2, one of the four human pantothenate kinase proteins.

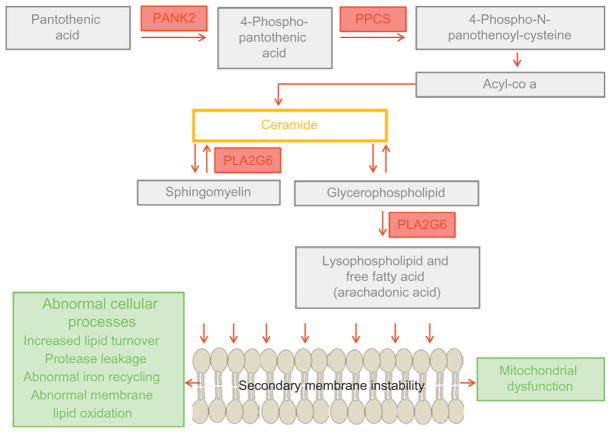

Pantothenate kinase is an essential regulatory enzyme in coenzyme A (CoA) biosynthesis, catalyzing the phosphorylation of pantothenate (vitamin B5), N-pantothenoyl-cysteine, and pantetheine (Fig. 2.2). CoA has a multitude of roles in adenosine triphosphate synthesis as well as fatty acid and neurotransmitter metabolism. The PANK2 enzyme localizes to mitochondria in both the human and mouse brain (Brunetti et al., 2012). PANK2 mutations are postulated to cause mitochondrial dysfunction, although the precise mechanisms are yet to be elucidated. Recent data from Pank2-defective neurons derived from knockout mice show altered mitochondrial membrane potential, swollen mitochondria at the ultrastructural level, and defective respiration (Brunetti et al., 2012). PANK2 dysfunction leads to neurotoxic accumulation of its substrates cysteine and pantetheine (Yang, Campbell, & Bondy, 2000; Yoon, Koh, Floyd, & Park, 2000). Cysteine is a potent iron chelator, and high local cysteine levels may lead to secondary iron accumulation and secondary oxidative stress-induced neuronal injury.

Figure 2.2.

PLA2G6 and PANK2 enzymes: biochemical pathway and implicated cellular processes in PLAN and PKAN.

The lack of a robust mammalian model of the disease (that accurately recapitulates the human phenotype) is an ongoing limiting factor in further elucidation of the disease mechanisms in PKAN. A Drosophila melanogaster model is one of the best animal models to date, and the PANK2 (fumble)−/− fly has reduced coordination and an impaired ability to climb, with recovery of the motor phenotype with pantetheine therapy (Rana et al., 2010). Despite promising data from knockout murine neurons (Brunetti et al., 2012), the knockout mouse model of PKAN develops retinal degeneration and azoospermia (Kuo et al., 2005) but no motor features nor brain iron accumulation. Other PANK isoforms (1, 3, and 4) are suspected to compensate for PANK2 loss in these animal models.

2.6. Management of PKAN treatment

2.6.1 Clinical assessment

Detailed neurological examination

Neurodevelopmental assessment by a multidisciplinary team including physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and speech and language therapists

Ophthalmologic assessment and ERG

MRI brain scan

Medical genetics consultation for counseling

Regular monitoring of height, weight, and nutritional status.

2.6.2 Treatment strategies

To date, the majority of treatment strategies are supportive and focus on palliation and symptom control, rather than disease modification.

2.6.3 Spasticity and dystonia

Intramuscular focal botulinum toxin to specific muscle groups

Oral baclofen and intrathecal baclofen in severe cases

Trihexyphenidyl and benzodiazepines

Deep brain stimulation (DBS).

Data regarding surgical intervention with DBS are still emerging. A cohort of patients treated with DBS showed improved motor function with gains in writing, speech, walking, and global measures of motor skills (Castelnau et al., 2005). Long-term data on this study are eagerly awaited. In addition, Mahoney et al. (2011) report improvement in cognitive function post-DBS in a cohort of seven children with PKAN. A number of additional single-case reports with varying follow-up times and anecdotal reports from PKAN families also support the notion that DBS can provide benefit in some cases (Isaac, Wright, Bhattacharyya, Baxter, & Rowe, 2008; Krause et al., 2006; Lim et al., 2012; Mikata, Yehya, Darwish, Karam, & Comair, 2009; Shields, Sharma, Gale, & Eskandar, 2007). The largest study to date by Timmermann et al. (2010) reports 23 PKAN patients undergoing DBS treatment (from 16 different DBS centers) and found improvement in both dystonia (particularly in the most severely affected patients) and the quality of life up to 15 months post-DBS. Further data on DBS treatment will no doubt inform clinical practice for PKAN patients in the future.

2.6.4 Multidisciplinary team input

Physiotherapy and occupational therapy to optimize joint mobility, minimize contractures, maintain posture, and maximize motor function

Adaptive aids for ambulation and mobility (walkers and wheelchairs)

Speech and language therapy (for dysarthria) and communication devices

Swallow assessment for safety of swallow

Dietetic input to maintain adequate caloric requirements and prevent malnutrition

Treatment of constipation and gastroesophageal reflux

Prompt PEG referral (as needed) to support any feeding difficulties

Vision support

Appropriate educational setting (and statementing of needs as appropriate)

Dental extraction or bite blocking if orolingual dystonia leads to recurrent tongue biting

Prompt recognition and treatment of painful factors that may exacerbate the movement disorder, such as occult GI bleeding, urinary tract infections, pressure sores from immobility, and bone fractures.

2.6.5 New experimental therapies under consideration (see Chapter 7)

2.6.5.1 Iron chelation (see Chapter 7)

The potential for iron chelation using deferiprone (an iron chelator that is able to cross the blood–brain barrier) to modify disease and improve clinical symptoms is highly topical at present with the start of the Treat Iron-Related Childhood-Onset Neurodegeneration (TIRCON) trial. To date, there are mixed reports in the literature. Abbruzzese et al. (2011) reported good tolerability of deferiprone, with reduction of radiologically discernible brain iron, and clinical improvement in some PKAN patients. Another pilot phase II trial showed that deferiprone was tolerated well in the nine PKAN patients who completed the study, with statistically significant reduction of iron in the pallida by MRI evaluation but disappointingly without clinical improvement of symptoms. Zorzi et al. (2011) postulated that a longer trial period may be necessary to produce clinical benefit.

2.6.5.2 Pantothenate

In PKAN patients who have residual PANK2 activity, the possibility of using high-dose pantothenate therapy has been considered. Pantothenate is well tolerated with no known toxicity. The effect of pantothenate supplementation in PKAN is currently unknown although patients with atypical PKAN have anecdotally reported improvement in motor symptoms, speech, cognition, and well-being while on treatment.

3. PLA2G6-ASSOCIATED NEURODEGENERATION

In 1952, Seitelberger (1952) first described an infantile-onset disorder characterized by neurological regression and lipid storage in the brain. Originally coined as Seitelberger disease, he described a disorder later to be known as infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy (INAD). More than 50 years later, the disease-causing gene was identified (PLA2G6) (Morgan et al., 2006), and over time, it is clear that a number of different, yet related phenotypes are caused by mutations in this gene. The newly termed PLAN is a second major NBIA phenotype and comprises a continuum of three overlapping phenotypes:

Classic INAD

Atypical neuroaxonal dystrophy (atypical NAD), including Karak syndrome

PLA2G6-related dystonia-parkinsonism.

Disease prevalence is not established but PLAN is rare, with an estimated prevalence rate of approximately 1/million (Gregory et al., 2009).

3.1. Clinical features of PLAN

3.1.1 Disease onset

Classical INAD

INAD usually manifests between 6 months and 3 years of age. Infants are usually born following an unremarkable pregnancy and have a normal neurodevelopmental course in early infancy. At presentation, the majority of children display neurological regression with loss of previously acquired skills. Some present following an intercurrent illness (Kurian et al., 2008). Gait disturbance and loss of ambulation are often seen in the early stages of disease, as well as truncal hypotonia and strabismus.

Atypical NAD

Patients with atypical NAD have a slightly later age of disease onset in early childhood but it can also be as late as the end of the 2nd decade. Like in INAD, presentation is often associated with gait impairment or ataxia, but a number of patients also present with social communication difficulties, displaying speech difficulties, and autistic traits (Gregory, Westaway, et al., 2008). Indeed, these nonspecific features may be the only symptoms present for a significant period of time before the onset of motor symptoms.

PLA2G6-related dystonia-parkinsonism

PLA2G6-related dystonia-parkinsonism has a wide age range of presentation (4–30 years) (Bower, Bushara, Dempsey, Das, & Tuite, 2011; Paisan-Ruiz et al., 2009; Yoshino et al., 2010), although most presented in early adulthood (second and early third decade). Patients presenting with this condition in childhood showed features similar to those seen in atypical NAD (gait abnormalities and speech difficulties), whereas young adults seem to present with gait disturbance or neuropsychiatric symptoms.

3.1.2 Disease clinical features

Classical INAD

Clinical presentation is fairly homogenous in this PLAN subtype. Truncal hypotonia is often seen early in the disease course. Upper motor neuron signs are commonly reported. Initially patients show hyper-reflexia and hypertonicity, and later in the disease course, there is evidence of spastic tetraparesis, with symmetrical pyramidal tract signs, areflexia, and contractures on clinical examination. Visual features are also commonly reported, and strabismus and nystagmus are often seen early in the disease course. As disease progresses, optic nerve pallor and then optic atrophy are reported in the majority of cases. Seizures are uncommon in INAD and usually a late manifestation of disease (Nardocci et al., 1999; Wu et al., 2009).

Atypical NAD

Patients with atypical NAD are less homogenous in clinical presentation than those with INAD. Over the disease course, patients mainly develop a predominantly extrapyramidal phenotype with prominent dystonia and dysarthria. Neuropsychiatric disturbances are also common (Gregory, Westaway, et al., 2008) and include hyperactivity, impulsivity, poor attention, and periods of emotional lability. Visual features are similar to those seen in INAD. Spastic tetraparesis may be evident but is usually a feature at end-stage disease, and in contrast to INAD, it is rarely preceded by early truncal hypotonia.

PLA2G6-related dystonia-parkinsonism

To date, only a few cases of this adult-onset PLAN subtype have been described in the literature. Dystonia-parkinsonism is universally seen developing in late teenage years or early twenties and is associated with rapid decline in cognitive function. Psychiatric features are commonly reported and may precede or occur at the same time as motor dysfunction. Parkinsonism manifests with progressive bradykinesia, resting coarse tremor, rigidity, and postural instability. Hand/foot dystonia is commonly seen but some patients will also have a more generalized dystonia. Although it has been reported that patients respond to L-dopa, this appears to be a temporary effect, and patients rapidly develop progressive motor symptoms of medication-related dyskinesia.

3.1.3 Disease course

Classical INAD

Of all the PLAN phenotypes, disease progression is the fastest in INAD. Severe neurological regression leads to spasticity, contractures, progressive cognitive dysfunction, and visual impairment. By end-stage disease children are in a vegetative state. Death is common from the end of the 1st decade and usually is a consequence of secondary complications such as intercurrent respiratory illnesses or aspiration pneumonia secondary to bulbar dysfunction. Appropriate supportive care can improve longevity in these children.

Atypical NAD

Affected patients often will have fairly stable course during early childhood with neurological deterioration in midchildhood (Nardocci et al., 1999). Atypical cases are rare, and only a handful of cases are reported in the literature, including those with Karak syndrome (Mubaidin et al., 2003). Consequently, little is currently known about the life span in atypical NAD, although with its less severe presentation, and course, it is typically longer than that described in classic disease.

PLA2G6-related dystonia-parkinsonism

The rarity of cases precludes an accurate picture of long-term prognosis. Following onset of symptoms, motor and cognitive decline progress rapidly in affected patients.

3.1.4 Electrophysiological investigations in PLAN

Infantile PLAN is associated with a number of abnormalities on electrophysiological investigation that can aid diagnosis (Carrilho et al., 2008). High-amplitude fast activity is often seen on electroencephalography (EEG). Fast rhythms of EEG have not been reported in atypical NAD, although some children may develop epileptiform EEG changes. In INAD, denervation may be seen on electromyography (EMG), with a distal axonal-type sensorimotor neuropathy on nerve conduction studies (NCS). Visual evoked potentials show either absent or delayed reduced amplitude.

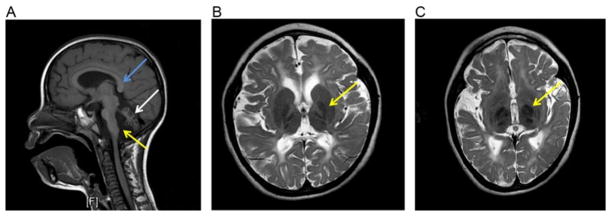

3.2. Neuroimaging features of PLAN (Fig. 2.3)

Figure 2.3.

Radiological features of PLAN on brain MRI. Sagittal T1-weighted sequence (A) showing abnormal orientation of the posterior splenium of the corpus callosum (blue arrow), apparent claval hypertrophy (yellow arrow), and marked atrophy of the cerebellum (white arrow). T2-weighted sequences showing hypointensity in the globus pallidus (B) and substantia nigra (C), both indicated by yellow arrows. Note symmetrical white matter changes are evident on images (B) and (C), which can be reported in PLAN.

For INAD, cerebellar atrophy is a universal feature and often the earliest sign on MRI (Farina et al., 1999). Cerebellar gliosis is additionally seen in many cases but not in all INAD patients (Kurian et al., 2008). Secondary posterior corpus callosum abnormalities (vertical orientation, thinning, and elongation of the splenium) secondary to cerebellar atrophy are also reported. Brain iron accumulation within the (medial) globus pallidus (McNeill et al., 2008), dentate nuclei, and substantia nigra is also described, with increasing severity with age (Kurian et al., 2008). Clinical optic atrophy is also evident radiologically with reduced volume of the optic chiasm and optic nerves. Cerebral white matter changes such as high signal on T2-weighted sequences as well as atrophy have also been described. More recently, apparent “claval hypertrophy” has been identified as a consistent feature in INAD (Maawali et al., 2011).

In atypical NAD, prominent brain iron is the main neuroradiological feature with or without cerebellar atrophy. In patients with PLA2G6-related dystonia-parkinsonism, to date, reports only detail the presence of nonspecific changes such as cerebral atrophy.

3.3. Neuropathological features of PLAN

Electron microscopic examination of nerve structure in conjunctival, skin, muscle, rectal, or sural nerve tissue demonstrates the present of axonal spheroids in later-stage INAD. However, it is not a consistent finding in early disease or indeed in all INAD patients. The presence of peripheral spheroids has been reported in atypical PLAN but not in patients with PLA2G6-related dystonia-parkinsonism—the advent of molecular testing has negated the need for biopsy; therefore, it is still unclear whether this pathological hallmark is truly evident in the non-INAD PLAN subtypes.

Paisán-Ruiz et al. (2012) examined postmortem brain tissue from PLAN patients (age of death 8–36 years) and demonstrated widespread alpha-synuclein-positive Lewy pathology (diffuse neocortical type). In three-fifths of cases, there was hyperphosphorylated tau accumulation as threads, pretangles, and neurofibrillary tangles. The authors reported that in cases of PLA2G6-associated dystonia-parkinsonism, there was less tau involvement but still severe alpha-synuclein pathology. These data certainly suggest a link between the clinical and pathological features of PLAN and parkinsonian disorders.

3.4. Molecular genetic features of PLAN

In 2006, Morgan et al. (2006) identified PLA2G6 as the causative gene for INAD and atypical NAD. PLAN is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner, with similar recurrence risks to those described in PKAN. Identification of 2 disease-causing mutations will therefore facilitate appropriate genetic counseling, prenatal testing, and also preimplantation diagnosis.

To date, over 70 disease-causing mutations in PLA2G6 have been reported, including pathogenic missense variants, small exonic deletions, nonsense mutations, splice site mutations, and more recently copy number variants (Crompton et al., 2010). Common mutations have been identified in a number of reportedly unrelated families although the commonality of ethnic background in these families suggests a possible founder effect (such as the homozygous mutation c.1634A>C, p.Lys545Thr in a number of Pakistani PLAN families).

Limited genotype–phenotype correlations are evident although it appears that, similar to PKAN, all individuals with two null alleles present with infantile-onset PLAN. In addition, patients with atypical NAD tend to have two missense PLA2G6 mutations. Furthermore, mutations in PLA2G6-related dystonia-parkinsonism do not impair the catalytic activity of the PLA2G6 enzyme (Engel, Jing, O’Brien, Sun, & Kotzbauer, 2010), in contrast to mutations studied for INAD.

3.5. Pathogenic disease mechanisms in PLAN

PLA2G6 encodes an 85 kDa calcium-independent phospholipase A2 enzyme iPLA2-VIA (which is one of several calcium-independent phospholipases), active in a tetrameric form. This class of enzyme catalyzes the hydrolysis of glycerophospholipids, generating a free fatty acid (usually arachidonic acid) and a lysophospholipid (Fig. 2.2). iPLA2-VIA protein has proposed roles in phospholipid remodeling, arachidonic acid release, leukotriene and prostaglandin synthesis, and apoptosis (Balsinde & Balboa, 2005). The iPLA2 enzymes regulate levels of phospholipids (Baburina & Jackowski, 1999) thereby playing an important role in cell membrane homeostasis. Defects in iPLA2-VIA could lead to an imbalance of membrane phospholipids with secondary structural consequences to the cell. This may indeed contribute to the axonal pathology observed in INAD (Morgan et al., 2006).

Both knockout and knock-in murine models of PLAN have been developed (Wada, Kojo, & Seino, 2013), which show progressive motor dysfunction, hematopoietic abnormalities, and widespread axonal spheroids akin to those seen in human disease.

3.6. Management of PLAN

3.6.1 Clinical assessment

Detailed neurological examination

Neurodevelopmental assessment by a multidisciplinary team including physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and speech and language therapists

MRI brain scan

Ophthalmologic assessment and VER for optic atrophy

EEG

EMG/NCS

Medical genetics consultation for counseling

Consider biopsy if any doubts regarding diagnosis following genetic testing

Regular monitoring of height, weight, and nutritional status

Periodic assessment of vision and hearing

Psychiatry review if prominent psychiatric symptoms.

3.6.2 Multidisciplinary team input

Control of drooling and secretions with transdermal hyoscine patches or oral glycopyrrolate therapy

Supportive treatment for constipation (softeners and laxatives)

Feeding modifications (such as nasogastric or PEG feeding) as needed to prevent aspiration pneumonia and achieve adequate nutrition

A rehabilitation program with physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and orthopedic input to optimize joint mobility, minimize contractures, maintain posture, and maximize motor function.

3.6.3 New experimental therapies under consideration (see Chapter 7)

As previously discussed earlier in this chapter, the iron chelator, deferiprone is currently under investigation in PKAN. Promising results may lead the way for future trials in PLAN.

3.6.4 PLA2G6-dystonia parkinsonism

Consider treatment with dopaminergic agents such as L-dopa

Appropriate treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms by a psychiatrist.

3.6.5 Treatment strategies

3.6.5.1 For INAD and atypical NAD

Routine pharmacological treatment of spasticity (e.g., with baclofen) and seizures (with standard antiepileptic agents)

Treatment of dystonia in atypical NAD: trial of oral or intrathecal baclofen. A single case of atypical NAD treated with DBS resulted in clinical benefit (L Cif—personal communication).

4. CONCLUSION

Both PKAN and PLAN are major NBIA subtypes. In both disorders, neurological regression in tandem with cognitive decline, progressive motor dysfunction (with pyramidal and extrapyramidal features), and additional visual and neuropsychiatric features are reported. Both disorders are associated with a number of distinct, yet overlapping phenotypes. Advances in molecular genetic techniques and the availability of genetic testing will no doubt lead to further detailed characterization of the subtypes and clinical spectrum of PLAN and PKAN. Future research is likely to provide insight into the epigenetic mechanisms that determine specific PLAN/PKAN phenotypes. Despite advances in understanding the clinical, molecular, and pathological features of PKAN and PLAN, treatment strategies remain palliative, with currently little disease-modifying therapies for these two conditions. Future research in developing novel therapeutic strategies should be prioritized, given the life-limiting nature of these disorders.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patients and families for their ongoing support for NBIA research, which has allowed detailed characterization of these phenotypes. MAK is funded by the Wellcome Trust and Great Ormond Street Hospital Children’s Charity (GOSHCC); SJH is supported by the NBIA Disorders Association and Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute (UL1 RR024140 NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

References

- Abbruzzese G, Cossu G, Balocco M, Marchese R, Murgia D, Melis M, et al. A pilot trial of deferiprone for neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation. Haematologica. 2011;96:1708–1711. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.043018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baburina I, Jackowski S. Cellular responses to excess phospholipid. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:9400–9408. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsinde J, Balboa MA. Cellular regulation and proposed biological functions of group VIA calcium-independent phospholipase A2 in activated cells. Cellular Signalling. 2005;17:1052–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister FA, Auer DP, Hortnagel K, Freisinger P, Meitinger T. The eye-of-the-tiger sign is not a reliable disease marker for Hallervorden–Spatz syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;348:33–40. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-865714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benke T, Butterworth B. Palilalia and repetitive speech: Two case studies. Brain and Language. 2001;78:62–81. doi: 10.1006/brln.2000.2445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benke T, Hohenstein C, Poewe W, Butterworth B. Repetitive speech phenomena in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 2000;69:319–324. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.69.3.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bower MA, Bushara K, Dempsey MA, Das S, Tuite PJ. Novel mutations in siblings with later-onset PLA2G6-associated neurodegeneration (PLAN) Movement Disorders. 2011;26:1768–1769. doi: 10.1002/mds.23617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunetti D, Dusi S, Morbin M, Uggetti A, Moda F, D’Amato I, et al. Pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration: Altered mitochondria membrane potential and defective respiration in Pank2 knock-out mouse model. Human Molecular Genetics. 2012;21:5294–5305. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrilho I, Santos M, Guimarães A, Teixeira J, Chorão R, Martins M, et al. Infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy: What’s most important for the diagnosis? European Journal of Paediatric Neurology. 2008;12:491–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelnau P, Cif L, Valente EM, Vayssiere N, Hemm S, Gannau A, et al. Pallidal stimulation improves pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration. Annals of Neurology. 2005;57:738–741. doi: 10.1002/ana.20457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiapparini L, Savoiardo M, D’Arrigo S, Reale C, Zorzi G, Zibordi F, et al. The “eye-of-the-tiger” sign may be absent in the early stages of classic pantothenate kinase associated neurodegeneration. Neuropediatrics. 2011;42:159–162. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1285925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ching KH, Westaway SK, Gitschier J, Higgins JJ, Hayflick SJ. HARP syndrome is allelic with pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration. Neurology. 2002;58:1673–1674. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.11.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crompton D, Rehal PK, MacPherson L, Foster K, Lunt P, Hughes I, et al. Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) analysis is an effective tool for the detection of novel intragenic PLA2G6 mutations: Implications for molecular diagnosis. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 2010;100:207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Valle-López P, Pérez-García R, Sanguino-Andrés R, González-Pablos E. Adult onset Hallervorden–Spatz disease with psychotic symptoms. Actas Españolas de Psiquiatría. 2011;39:260–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado RF, Sanchez PR, Speckter H, Then EP, Jiminez R, Oviedo J, et al. Missense PANK2 mutation without “eye of the tiger” sign: MR findings in a large group of patients with pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration (PKAN) Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2012;35:788–794. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooling EC, Schoene WC, Richardson EP. Hallervorden–Spatz syndrome. Archives of Neurology. 1974;30:70–83. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1974.00490310072012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan RA, Weleber RG, Hogarth P, Gregory A, Coryell J, Westaway SK, et al. Neuro-ophthalmologic and electroretinographic findings in pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration (formerly Hallervorden–Spatz syndrome) American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2005;140:267–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel LA, Jing Z, O’Brien DE, Sun M, Kotzbauer PT. Catalytic function of PLA2G6 is impaired by mutations associated with infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy but not dystonia-parkinsonism. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12897. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farina L, Nardocci N, Bruzzone MG, D’Incerti L, Zorzi G, Verga L, et al. Infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy: Neuroradiological studies in 11 patients. Neuroradiology. 1999;41:376–380. doi: 10.1007/s002340050768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman K, Gregory A, Turner A, Blasco P, Hogarth P, Hayflick S. Intellectual and adaptive behavior functioning in pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2007;51:417–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00889.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory A, Hayflick SJ. Pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Fong CT, Stephens K, editors. GeneReviews™[Internet] Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 2012. (updated 2013 January 31) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory A, Hayflick SJ. Neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation disorders overview. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Fong CT, Stephens K, editors. GeneReviews™ [Internet] Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory A, Kurian MA, Maher ER, Hogarth P, Hayflick SJ. PLA2G6-associated neurodegeneration. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Bird TD, Dolan CR, Fong CT, Stephens K, editors. GeneReviews™ [Internet] Seattle, WA: University of Washington; 2008. (updated 2012 April 19) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory A, Polster BJ, Hayflick SJ. Clinical and genetic delineation of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2009;46:73–80. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.061929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory A, Westaway SK, Holm IE, Kotzbauer PT, Hogarth P, Sonek S, et al. Neurodegeneration associated with genetic defects in phospholipase A2. Neurology. 2008;71:1402–1409. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000327094.67726.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimaraes J, Santos JV. Generalized freezing in Hallervorden–Spatz syndrome: Case report. European Journal of Neurology. 1999;6:509–513. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.1999.640509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallervorden J. Uber eine familiare Erkrankung im extrapyramidalen System. Deutsche Zeitschrift für Nervenheilkunde. 1924;81:204–210. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig MB, Hortnagel K, Garavaglia B, Zorzi G, Kmiec T, Klopstock T, et al. Genotypic and phenotypic spectrum of PANK2 mutations in patients with neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation. Annals of Neurology. 2006;59:248–256. doi: 10.1002/ana.20771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayflick SJ, Penzien JM, Michl W, Sharif UM, Rosman NP, Wheeler PG. Cranial MRI changes may precede symptoms in Hallervorden–Spatz syndrome. Pediatric Neurology. 2001;25:166–169. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(01)00296-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayflick SJ, Westaway SK, Levinson B, Zhou B, Johnson MA, Ching KH, et al. Genetic, clinical, and radiographic delineation of Hallervorden–Spatz syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;348:33–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogarth P, Gregory A, Kruer MC, Sanford L, Wagoner W, Natowicz MR, et al. New form of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation: Features associated with MPAN. Neurology. 2013;80:268–275. [Google Scholar]

- Houlden H, Lincoln S, Farrer M, Cleland PG, Hardy J, Orrell RW. Compound heterozygous PANK2 mutations confirm HARP and Hallervorden–Spatz syndromes are allelic. Neurology. 2003;61:1423–1426. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000094120.09977.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaac C, Wright I, Bhattacharyya D, Baxter P, Rowe J. Pallidal stimulation for pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration dystonia. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2008;93:239–240. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.118968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeppen AH, Dickson AC. Iron in the Hallervorden–Spatz syndrome. Pediatric Neurology. 2001;25:148–155. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(01)00269-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause M, Fogel W, Tronnier V, Pohle S, Hörtnagel K, Thyen U, et al. Long-term benefit to pallidal deep brain stimulation in a case of dystonia secondary to pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration. Movement Disorders. 2006;21:2255–2257. doi: 10.1002/mds.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruer MC, Hiken M, Gregory A, Malandrini A, Clark D, Hogarth P, et al. Novel histopathologic findings in molecularly-confirmed pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration. Brain. 2011;134:947–958. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo YM, Duncan JL, Westaway SK, Yang H, Nune G, Xu EY, et al. Deficiency of pantothenate kinase 2 (Pank2) in mice leads to retinal degeneration and azoospermia. Human Molecular Genetics. 2005;14:49–57. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurian MA, Morgan NV, MacPherson L, Foster K, Peake D, Gupta R, et al. Phenotypic spectrum of neurodegeneration associated with mutations in the PLA2G6 gene (PLAN) Neurology. 2008;70:1623–1629. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000310986.48286.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A, Paudel R, Johnson R, Courtney R, Lees AJ, Holton JL, et al. Pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration is not a synucleinopathy. Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology. 2012;39:121–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2012.01269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim BC, Ki CS, Cho A, Hwang H, Kim KJ, Hwang YS, et al. Pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration in Korea: Recurrent R440P mutation in PANK2 and outcome of deep brain stimulation. European Journal of Neurology. 2012;4:556–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maawali AL, Yoon G, Halliday W, Clarke ATR, Feigenbaum A, Banwell B, et al. Hypertrophy of the clava, a new MRI sign in patients with PLA2G6 mutations. Poster presentation: American Society of Human genetics Meeting; October 2011.2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney R, Selway R, Lin JP. Cognitive functioning in children with pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration undergoing deep brain stimulation. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2011;53:275–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2010.03815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malandrini A, Cavallaro T, Fabrizi GM, Berti G, Salvestroni R, Salvadori C. Ultrastructure and immunoreactivity of dystrophic axons indicate a different pathogenesis of Hallervorden–Spatz disease and infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy. Virchows Archiv. 1995;427:415–421. doi: 10.1007/BF00199391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeill A, Birchall D, Hayflick SJ, Gregory A, Schenk JF, Zimmerman EA, et al. T2* and FSE MRI distinguishes four subtypes of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation. Neurology. 2008;70:1614–1619. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000310985.40011.d6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikata MA, Yehya A, Darwish H, Karam P, Comair Y. Deep brain stimulation as a mode of treatment of early onset pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology. 2009;13:61–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molinuevo JL, Marti MJ, Blesa R, Tolosa E. Pure akinesia: An unusual phenotype of Hallervorden–Spatz syndrome. Movement Disorders. 2003;18:1351–1353. doi: 10.1002/mds.10520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan NV, Westaway SK, Morton JE, Gregory A, Gissen P, Sonek S, et al. PLA2G6, encoding a phospholipase A2, is mutated in neurodegenerative disorders with high brain iron. Nature Genetics. 2006;38:752–754. doi: 10.1038/ng1826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mubaidin A, Roberts E, Hampshire D, Dehyyat M, Shurbaji A, Mubaidien M, et al. Karak syndrome: A novel degenerative disorder of the basal ganglia and cerebellum. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2003;40:543–546. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.7.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardocci N, Zorzi G, Farina L, Binelli S, Scaioli W, Ciano C, et al. Infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy: Clinical spectrum and diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1999;52:1472–1478. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.7.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paisan-Ruiz C, Bhatia KP, Li A, Hernandez D, Davis M, Wood NW, et al. Characterization of PLA2G6 as a locus for dystonia-parkinsonism. Annals of Neurology. 2009;65:19–23. doi: 10.1002/ana.21415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paisán-Ruiz C, Li A, Schneider SA, Holton JL, Johnson R, Kidd D, et al. Widespread Lewy body and tau accumulation in childhood and adult onset dystonia-parkinsonism cases with PLA2G6 mutations. Neurobiology of Aging. 2012;33:814–823. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellecchia MT, Valente EM, Cif L, Salvi S, Albanese A, Scarano V, et al. The diverse phenotype and genotype of pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration. Neurology. 2005;64:1810–1812. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000161843.52641.EC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana A, Seinen E, Siudeja K, Muntendam R, Srinivasan B, van der Want JJ, et al. Pantethine rescues a Drosophila model for pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:6988–6993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912105107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rump P, Lemmink HH, Verschuuren-Bemelmans CC, Grootscholten PM, Fock JM, Hayflick SJ, et al. A novel 3-bp deletion in the PANK2 gene of Dutch patients with pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration: Evidence for a founder effect. Neurogenetics. 2005;6:201–207. doi: 10.1007/s10048-005-0018-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarano V, Pellecchia MT, Filla A, Barone P. Hallervorden–Spatz syndrome resembling a typical Tourette syndrome. Movement Disorders. 2002;17:618–620. doi: 10.1002/mds.10105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider SA, Bhatia KP. Rare causes of dystonia parkinsonism. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 2010;10:431–439. doi: 10.1007/s11910-010-0136-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitelberger F. Eine unbekannte Form von infantiler lipoid-Speicher Krankheit des Gehirns. First international congress of neuropathology; Rome, Italy. 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Shevell M. Hallervorden and history. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;348:3–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp020158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields DC, Sharma N, Gale JT, Eskandar EN. Pallidal stimulation for dystonia in pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration. Pediatric Neurology. 2007;37:442–445. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strecker K, Hesse S, Wegner F, Sabri O, Schwarz J, Schneider JP. Eye of the tiger sign in multiple systems atrophy. European Journal of Neurology. 2007;14:e1–e2. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.01925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaiman KF. Hallervorden–Spatz syndrome. Pediatric Neurology. 2001;25:102–108. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(01)00253-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmermann L, Pauls KA, Wieland K, Jech R, Kurlemann G, Sharma N, et al. Dystonia in neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation: Outcome of bilateral pallidal stimulation. Brain. 2010;133:701–712. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada H, Kojo S, Seino KI. Mouse models of human INAD by Pla2g6 deficiency. Histology and Histopathology. 2013;28:965–969. doi: 10.14670/HH-28.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Jiang Y, Gao Z, Wang J, Yuan Y, Xiong H, et al. Clinical study and PLA2G6 mutation screening analysis in Chinese patients with infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy. European Journal of Neurology. 2009;16:240–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita S, Maeda Y, Ohmori H, Uchida Y, Hirano T, Yonemura K, et al. Pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration initially presenting as postural tremor alone in a Japanese family with homozygous N245S substitutions in the pantothenate kinase gene. Journal of Neurological Sciences. 2004;225:129–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang EY, Campbell A, Bondy SC. Configuration of thiols dictates their ability to promote iron-induced reactive oxygen species generation. Redox Report. 2000;5:371–375. doi: 10.1179/135100000101535942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon SJ, Koh YH, Floyd RA, Park JW. Copper, zinc superoxide dis-mutase enhances DNA damage and mutagenicity induced by cysteine/iron. Mutation Research. 2000;448:97–104. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(00)00005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshino H, Tomiyama H, Tachibana N, Ogaki K, Li Y, Funayama M, et al. Phenotypic spectrum of patients with PLA2G6 mutation and PARK14-linked parkinsonism. Neurology. 2010;75:1356–1361. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f73649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YM, Rock CO, Jackowski S. Biochemical properties of human pantothenate kinase 2 isoforms and mutations linked to pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281:107–114. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508825200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B, Westaway SK, Levinson B, Johnson MA, Gitschier J, Hayflick SJ. A novel pantothenate kinase gene (PANK2) is defective in Hallervorden–Spatz syndrome. Nature Genetics. 2001;28:345–349. doi: 10.1038/ng572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorzi G, Zibordi F, Chiapparini L, Bertini E, Russo L, Piga A, et al. Iron-related MRI images in patients with pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration (PKAN) treated with deferiprone: Results of a phase II pilot trial. Movement Disorders. 2011;26:1756–1759. doi: 10.1002/mds.23751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]