Abstract

Although previous work has demonstrated that the overexpression of wild-type or mutant α-synuclein (α-syn) can induce cell death via a number of different mechanisms, including oxidative stress, dysfunction of the ubiquitin-proteasome degradation system, mitochondrial damage and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, research interest has primarily focused on neurons. However, there is accumulating evidence that suggests that astrocytes may be involved in the earliest changes, as well as the progression of Parkinson's disease (PD), though the role of α-syn in astrocytes has not been widely studied. In the present study, it was revealed that the mutant α-syn (A53T and A30P) in astrocytes triggered ER stress via the protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase/eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α signaling pathway. Astrocyte apoptosis was induced through a CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein homologous protein-mediated pathway. In addition, Golgi fragmentation was observed in the process. On the other hand, it was also demonstrated, in a primary neuronal-astroglial co-culture system, that the overexpression of α-syn significantly decreased the levels of glia-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) and partly inhibited neurite outgrowth. Although direct evidence is currently lacking, it was proposed that dysfunction of the ER-Golgi compartment in astrocytes overexpressing α-syn may lead to a decline of GDNF levels, which in turn would suppress neurite outgrowth. Taken together, the results of the present study offer further insights into the pathogenesis of PD from the perspective of astrocytes, which may provide novel strategies for the diagnosis and treatment of PD in the future.

Keywords: α-synuclein, astrocytes, Parkinson's disease, endoplasmic reticulum stress, Golgi fragmentation, apoptosis

Introduction

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a common neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the progressive degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) and abnormal aggregation of α-synuclein (α-syn) (1). With increasing awareness of the importance of genetic factors involved in the disease, several genes that lead to hereditary PD were identified over a period of ten years. Among them, α-syn was the first genetic factor found to be linked to PD. At the time of writing, 6 pathogenic mutations of α-syn were known to be involved in autosomal recessive parkinsonism-A53T, E46K, A30P, H50Q, G51D and A53E (2–7). A53T and A30P were the first two identified SNCA mutations and more slightly common occurrence among the point mutations (8).

The aggregation of α-syn in the brain, from soluble oligomers to insoluble inclusions, may be the initial pathophysiological change in PD, and it also contributes to the pathogenesis of familial or idiopathic PD (5). Moreover, there is accumulating evidence that many cellular defects are implicated in the etiology of synucleinopathies, including impairment of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction (9). A variety of conditions that disturb folding of proteins in the endoplasmic-reticulum (ER) can trigger ER stress response (10). The accumulation of unfolded proteins in the ER can trigger an evolutionarily conserved response, termed the unfolded protein response (UPR). UPR is the response which transiently clears unfolded proteins in order to restores ER homeostasis and to promote cell survival (11). The typical UPR consists of three pathways in eukaryotic cells, which are mediated by three ER membrane-associated proteins: PKR-like eukaryotic initiation factor 2a kinase (PERK), inositol requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1), and activating transcription factor-6 (ATF6) (12). Under stress-free conditions, these sensors are combined with the ER chaperone Bip/GRP78 (glucose regulated protein 78) and exist in their deactivated form (13). When misfolded proteins accumulate in the ER lumen, UPR sensors detach from GRP78, causing PERK oligomerization and autophosphorylation. Active PERK phosphorylates eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α), rendering it inactive and blocking protein translation (14,15). The phosphorylation of eIF2α inhibits the recycling of eIF2α to its active GTP-bound form, which prevents the further influx of nascent proteins into the already stressed ER lumen (16). If the various UPR-induced mechanisms fail to alleviate ER stress, the PERK pathway activation can induce expression of the proapoptotic transcription factor C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP/GADD153), downstream of the PERK-eIF2α-ATF4 pathway, which eventually cleaves caspase-3 to mediate cell apoptosis (17).

The association between α-syn and ER stress, as well as the role of ER and the Golgi apparatus (GA) in the neurodegeneration observed in PD has attracted more attention in recent years. Previous studies have demonstrated that the accumulation of α-syn oligomers within the ER compartment causes chronic ER stress which can induce cell death (11,18). Moreover, studies in mutant mice showed that the overexpression of α-syn leads to the fragmentation of GA in dopaminergic neurons in the midbrain of mutant mice (19). Furthermore, Cooper et al (20) have found evidence that α-syn accumulation inhibits vesicular trafficking between the ER and GA in vitro. However, all of these studies of the effects of α-syn on the ER-Golgi compartment have focused exclusively on neurons.

Recently, increasing evidence has suggested that neurodegeneration associated with the expression of these muteins is not restricted to dopaminergic neurons, indicating that dysfunction of non-dopaminergic systems also contributes to the pathogenesis of PD (21,22). In a 2011 systematic review of glial involvement in PD, Halliday and Stevens drew the conclusion that astrocytes play an important role in both the initiation and progression of PD degeneration (23). Although astrocytes constitute the largest population of non-excitable cells in the central nervous system (CNS), they were initially considered to be passive supporting cells. However, a growing list of studies indicates that astrocytes are involved in a much wider range of brain functions, including the active control of synaptogenesis (24) and plasticity (25,26), the regulation of blood flow (27) and restoration of neurons (28), as well as the nourishing of nerves and the promotion of myelination (29). Meanwhile, increasing attention has been paid to the role of astrocytes in neurodegenerative disorders, especially in PD. For example, direct experiments confirmed that astrocytes take up altered α-syn that has been released from axon terminals and astrocytes containing α-syn aggregates, after which they produce proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, which in turn elicit microglial activation and finally contribute to the degeneration of neurons (30).

In our study, we obtained highly purified primary rat astrocytes by a modification of a previously described method, followed by infection with appropriate packaged lentiviral vectors to establish astrocyte lines overexpressing wild-type and mutant α-syn (A30P and A53T). Furthermore, western bolt analysis, immunofluorescence, flow cytometry and ELISA were used to study in detail the links between α-syn and ER stress, Golgi fragmentation, apoptosis, secretion of neurotrophic factors, and growth of neurons. In general, our research might provide new perspectives for understanding the roles of astrocytes in the pathogenesis of PD.

Materials and methods

Materials

Newborn Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (day 0–3) were obtained from the Experimental Animal Center of Xiangya Medical College, Central South University (Changsha, Hunan, China). Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Xiangya Medical College, Central South University. The experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of State Key Laboratory of Medical Genetics (Hunan, China). The mammalian expression plasmids α-syn-A53T-HA-FUIGW-GFP, α-syn-A30P-HA-FUIGW-GFP, α-syn-WT-HA-FUIGW-GFP and FUIGW-GFP (31) were constructed by our group (State Key Laboratory of Medical Genetics). 293FT cells were from the cell bank of the Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). The antibodies against HA (1:1,000; SAB1306169), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; 1:500; SAB4300647), binding immunoglobulin heavy chain protein (BiP; 1:3,000; G8918), MAP2 (1:1,000; HPA012828), and β-actin (1:2,000; A5316) were all from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck-Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). Anti-α-syn (1:1,000; cat. no. 2642), PEARK (1:1,000; cat. no. 5683), p-PEARK (1:1,000; cat. no. 3179), eIF2α (1:1,000; cat. no. 5324), p-eIF2α (1:1,000; cat. no. 3398), caspase-3 (1:1,000; cat. no. 9664) and anti-CHOP antibodies (1:1,000; cat. no. 5554) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). The GDNF enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit was from Promega Corp. (Madison, WI, USA) and the Annexin V-FITC/PI Apoptosis Detection kit was purchased from Invitrogen (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The small interfering RNA (siRNA) for the CHOP protein and the non-targeting scramble siRNA were purchased from (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck-Millipore). The first RNA sequence was: Sense, 5′GGAAGAACUAGGAAACGGA; antisense, 5′UCCGUUUCCUAGUUCUUCC. The second siRNA sequence was: Sense, 5′CUGGGAAACAGCGCAUGAA; antisense, 5′UUCAUGCGCUGUUUCCCAG. The Lipofectamine® RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent was from Invitrogen (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The ViraPower Packaging Mix and Lipofectamine 2000 were from Invitrogen (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). DMEM/F12 and 0.25% trypsin (with EDTA) were from Gibco (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Neurobasal-A medium, B27 supplement, Hank's Balanced Salt Solution, 0.125% trypsin (without EDTA) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were from Gibco (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Isolation, purification and culture of primary rat astrocytes and cortical neurons

Astrocytes were obtained as described previously (32,33), with some modifications as follows: Postnatal day 1–3, SD rats were decapitated and the cortices were dissociated. The removed cortices were washed with precooled Hank's balanced salt solution and minced, followed by incubating with 0.25% (wt/vol) trypsin/1 mM EDTA for 10 min at 37°C. After centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min, the pellet was resuspended in DMEM and F12 (1:1) with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin (both Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The cells were cultured for 1 h at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere comprising 5% CO2 in an incubator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and the flasks were shaken every 10 min to remove fibroblasts and blood cells. After collecting the supernatant, the cells were resuspended and seeded into culture flasks. After 72 h, the medium was changed to fresh DMEM/F12 and replaced every 3–4 days. The resulting mixed glial cells were cultured for 7–10 days at 37°C, in an atmosphere comprising 5% CO2. Astrocytes were purified from the mixed cultures by mild trypsinization (0.05% trypsin, without EDTA) to remove microglial cells and oligodendrocytes. The purified astrocytes were cultured in DMEM/F12 with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin, and identified by phase-contrast microscopy (Leica Microsystems Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) and immunofluorescence.

Isolation and purification of cortical neurons and co-culture with astrocytes

The method used was based on a previously described protocol (34). Briefly, cortices were isolated from neonatal SD rats within 24 h of birth. The tissue was cut into small pieces and digested with 0.125% (wt/vol) trypsin for 10 min at 37°C, followed by centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min and resuspension in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, after which the resulting suspension was planted into the bottom compartment of a porous Transwell cell culture chamber treated with 1 mg/ml polylysine (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck-Millipore) for co-culture. The medium was changed to Neurobasal/B27 medium with 2 mM L-glutamine 4 h later. Astrocytes infected with appropriate lentiviral vectors were placed on the top of the culture chamber and co-cultured with neurons for 4 days at 37°C in an atmosphere comprising 5% CO2.

Lentivirus vector construction and infection of primary rat astrocytes

The protocol used is based on the method described by Su et al (35). Briefly, 3 µg of the mammalian expression plasmids α-syn-A53T-HA-FUIGW-GFP, α-syn-A30P-HA-FUIGW-GFP, α-syn-WT-HA-FUIGW-GFP and FUIGW-GFP were individually used to transfected 293FT cells using Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer's instructions, according to the steps in the lentivirus equipment package. Transfection efficiency was assessed under a fluorescent microscope (Leica Microsystems Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) and cell culture supernatant was collected 72 h post-transfection. The lentiviral particles were concentrated by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 2 h and stored at −70°C until use.

Astrocytes were seeded into the wells of 12-well plates and grown to 70% confluence before infection. The following day, an appropriate amount of lentiviral particle suspension was diluted into medium containing 6 µg/ml of hexadimethrine bromide (Polybrene; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck-Millipore), after which the old medium was exchanged for the thus-prepared virion-containing medium, and infection was conducted overnight. The virion-containing medium was replaced with complete culture medium the following day. At 7 days after infection, the expression of α-syn was examined by western blot analysis and immunofluorescence using an antibody against HA.

Knockdown of CHOP

Astrocytes were seeded into the wells of 10 cm plates and grown to 70% confluence. Cells were cultured in 10 ml medium composed of 8 ml of antibiotic-free growth medium and 2 ml of Opti-MEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 20 µl of Lipofectamine RNAiMAX, and 200 pmol of CHOP siRNA. After 24 h of transfection, cells were changed to normal growth medium and plated into 12-well plates.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were washed with 1×PBS and fixed with 4% w/v paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck-Millipore) in PBS for 15 min at room temperature. After washing three times, the cells were permeabilized by incubation in 1xPBS containing 1% Triton-X100 and 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h at room temperature, after which they were incubated with the primary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature. Appropriate secondary antibodies were used to detect the corresponding proteins, after which the cells were washed three times with 1xPBS. The cells were stored in the dark at 4°C until visualization under a confocal laser microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Immunoassay for the detection of GDNF Secretion

For the GDNF secretion assay, the supernatants of primary rat astrocytes infected with lentiviral vectors overexpressing wild-type α-syn, mutant α-syn or GFP-FUIGW (Control) were collected at the 7th day after infection and stored at −80°C until further use. Measurement of GDNF was performed using the GDNF ELISA kit according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Western blot analysis

Cells were collected and lysed in RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitors. 20 µg of protein were separated via SDS-PAGE on a 12% polyacrylamide gel in running buffer. After electrophoresis, the proteins were blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham, Bensheim, Germany), after which the membranes were incubated in PBST containing 5% fat-free milk (Nestle, Beijing, China) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by incubation with different primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. The primary antibodies were detected using a horse-radish peroxidase-linked secondary antibody in conjunction with an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagent (Pharmacia; GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA).

Annexin V and PI double staining

Different groups of cells were trypsinized and gently washed once with medium, followed by washing with PBS before re-suspension in 85 µl of binding buffer. Double staining was performed with 10 µl of Annexin V-FITC and 5 µl of PI were added to the re-suspended cells. After incubation at room temperature for 15 min in the dark, 400 µl of binding buffer was added to the cell suspension. Measurement of the cell samples was performed on an EPICS ALTRA flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Miami, US).

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as means ± standard deviation. Analysis was conducted using ImageJ 1.51j8 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, USA), GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, USA) and SPSS software (v16.0; IBM Corp, Chicago, IL, USA). Comparisons between groups were determined by one-way analysis of variance with Dunnett's t-test, P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. All experiments were repeated three times.

Results

Highly purified astrocytes were obtained and their derivative lines overexpressing wild-type or mutant α-syn were established successfully

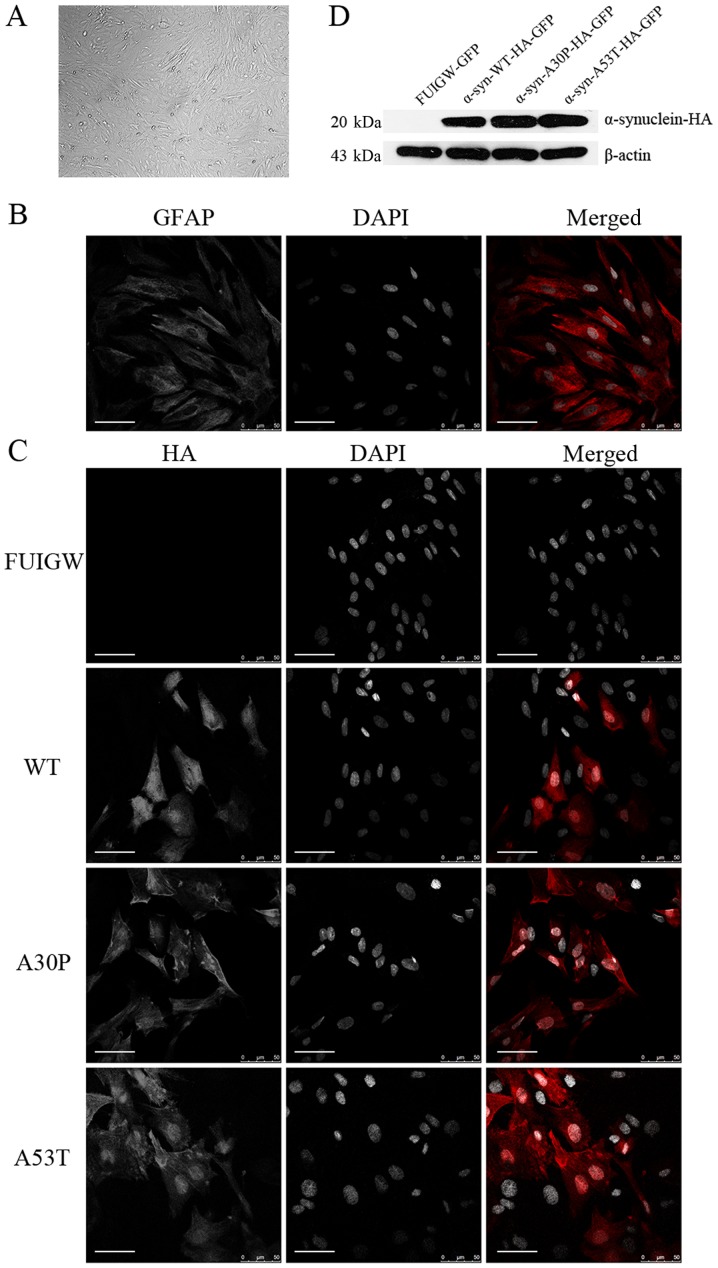

Astrocytes were isolated and purified by differential adhesion and mild trypsinization as described in Materials and Methods. When growing to 90% confluence, the astrocytes displayed irregular shapes with long and rich processes under the phase-contrast microscope (Fig. 1A). Additionally, immunofluorescence with antibodies reactive against GFAP was used to confirm the cells' identity (Fig. 1B). The purity of the thus obtained astrocytes was almost 90%.

Figure 1.

Identification of cultured astrocytes and the determination of the expression of the α-syn-HA fusion protein following lentiviral infection. (A) Under a phase-contrast microscope, the cultured primary astrocytes displayed an irregular shape with long and rich processes (magnification, ×100). (B) Astrocytes were immunostained with an anti-GFAP antibody (red) and the nuclei were stained with DAPI (gray). (C) Immunofluorescence localization analysis of the α-syn-HA fusion protein. Astrocytes were infected with lentiviral vectors expressing α-syn-WT-HA-FUIGW-GFP, α-syn-A53T-HA-FUIGW-GFP, α-syn-A30P-HA-FUIGW-GFP and FUIGW-GFP, respectively. Using immunofluorescent microscopy, the fusion proteins α-syn-WT-HA-FUIGW-GFP, α-syn-A53T-HA-FUIGW-GFP and α-syn-A30P-HA-FUIGW-GFP stained positively for HA (red), while there was no red fluorescence in the astrocytes infected with the control vector FUIGW-GFP. Nuclei are shown in gray (DAPI). DAPI staining has been altered to gray to more clearly show the morphological structure. Scale bars, 50 µm. (D) Western blot analysis of the expression of the fusion protein α-syn-HA in the three cell lines overexpressing WT and two mutant α-syn proteins, and the negative control expressing FUIGW-GFP. The results were consistent with the immunofluorescence observations. α-syn, α-synuclein; WT, wild-type; HA, influenza A hemagglutinin; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein.

To establish astrocyte lines overexpressing wild-type or mutant α-syn, we infected the primary astrocytes with lentiviral vectors. The results of immunofluorescence using anti-HA antibodies to label the α-syn-HA fusion protein and DAPI to stain the nuclei showed that the fusion protein was diffusely distributed within the astrocytes infected with the α-syn-HA-FUIGW-GFP lentivirus vector, while the astrocytes infected with the FUIGW-GFP control vector showed negative immunostaining (Fig. 1C). Further western blot analysis was in agreement with the immunofluorescence results (Fig. 1D). The data thus indicate that astrocyte lines overexpressing wild-type or mutant α-syn were established successfully.

ER stress in astrocytes is triggered by the overexpression of wild-type or mutant α-syn

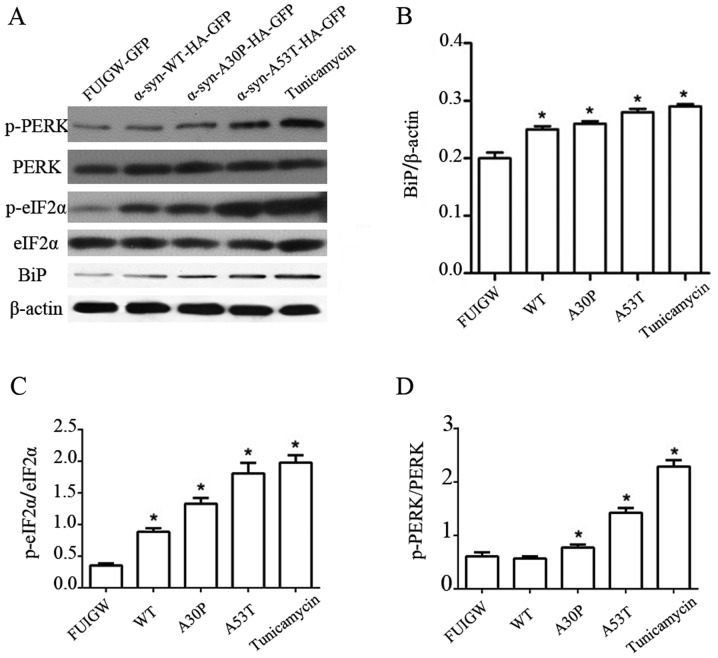

It has been suggested that ER stress caused by the accumulation of α-syn in dopaminergic neurons is pivotal to the pathogenesis of PD (36). To confirm whether similar changes happened in astrocytes, primary rat astrocytes were infected with lentiviral vectors expressing wild-type or mutant α-syn, respectively. In addition, total proteins from primary rat astrocytes treated with tunicamycin for 6 h were also analyzed as a positive control. Cells were cultured for 7 days after infection and we examined the expression of BiP, phosphorylated or total forms of PERK and eIF2α. Bip is an ER-resident chaperone, which is regarded as a marker of ER stress. The activation of PERK-eIF2α axis was demonstrated by p-PERK and p-eIF2α. Cells expressing mutant proteins showed increase in BiP, p-PERK and p-eIF2α than the empty vector control (Fig. 2A-D). These results thus show that overexpression of mutant α-syn can induce the PERK-eIF2α axis of ER stress in astrocytes, whereas wild-type might induce ER stress through other axises.

Figure 2.

Induction of UPR and PERK pathway in astrocytes overexpressing α-syn. (A) Western blot analysis of astrocytes 7 days following infection with lentiviral vectors expressing α-syn-WT-HA-FUIGW-GFP, α-syn-A53T-HA-FUIGW-GFP, α-syn-A30P-HA-FUIGW-GFP and the negative control FUIGW-GFP. Protein levels of Bip, total PERK, phosphorylated PERK, total eIF2α and phosphorylated eIF2α were determined by western blot analyses. β-actin blotting was used as a loading control. (B) Integrated density values for BiP relative to β-actin. (C) Integrated density values for phosphorylated eIF2α relative to total eIF2α. (D) Integrated density values for phosphorylated PERK relative to total PERK. The bars represent the mean ± standard deviation. *P<0.05 vs. FUIGW (negative control). α-syn, α-synuclein; WT, wild-type; HA, influenza A hemagglutinin; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; GFP, green fluorescence protein; UPR, unfolded protein response; PERK, protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase; Bip, binding immunoglobulin heavy chain protein; p-, phosphorylated; eIF2α, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α.

Overexpression of wild-type or mutant α-syn damages the GA of astrocytes

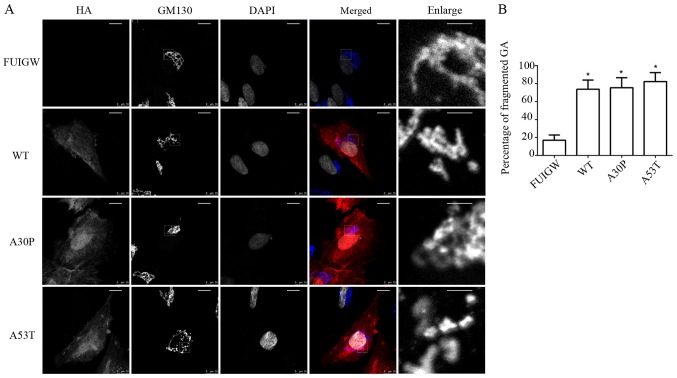

To examine whether the GA was also affected by the overexpression of wild-type or mutant α-syn, immunofluorescence was used. We infected primary rat astrocytes as described before, while cells expressing GFP-FUIGW were used as a control. We analyzed the morphology of the GA in the primary rat astrocytes at the 7th day post-transfection using the cis-Golgi matrix protein marker GM130 (37,38), which can be used to visualize the morphology of GA, as well as its location. At least 200 cells were analyzed in each group and the percentage of fragmented GA was calculated as described previously (19). Under the confocal laser microscope, the GA of astrocytes overexpressing wild-type or mutant α-syn was diffusely distributed in the cytoplasm, reticulate structures were apparently disturbed, which was accompanied by apparent breakdown. By contrast, the GA of the cells expressing GFP-FUIGW maintained a normal juxtanuclear anastomosing linear profile (Fig. 3A). Compared with the control group, in which Golgi fragmentation was observed in 16.9±5.8% of cells, the percentage of fragmented GA in the cells overexpressing wild-type or mutant α-syn (A30P and A53T) was much higher, at 73.7±10.1, 75.5±11.1 and 82.3±9.9%, respectively. Moreover, the results were statistically significant (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, immunofluorescence showed that the α-syn-HA fusion protein did not co-localize with the GA, which was consistent with previous studies (39). The results therefore indicate that the overexpression of wild-type or mutant α-syn causes fragmentation of the GA in astrocytes.

Figure 3.

Golgi fragmentation in astrocytes overexpressing WT and mutant α-syn. (A) Morphology of GA was observed 7 days following infection. α-syn-HA and GA were stained using antibodies reactive against HA (red) and GM130 (blue, in merged image), and nuclei were stained with DAPI (altered to gray). A breakdown of the GA was visible in the astrocytes overexpressing WT or mutant α-syn (A30P and A53T, respectively), while they were intact in the control group (scale bars, 10 µm). The single-channel staining images for GM130 and DAPI have been altered to gray to more clearly show the morphological structure. The images labelled ‘enlarge’ are the enlarged images of the section surrounded by a dotted line in the GM130 images (scale bars, 2 µm). (B) Quantitative analysis of GA fragmentation among the different groups. The bars represent mean values ± standard deviation. *P<0.05 vs. FUIGW (negative control). α-syn, α-synuclein; WT, wild-type; HA, influenza A hemagglutinin; GFP, green fluorescence protein; GA, Golgi apparatus.

Overexpression of wild-type or mutant α-syn can activate CHOP and induce apoptosis in astrocytes

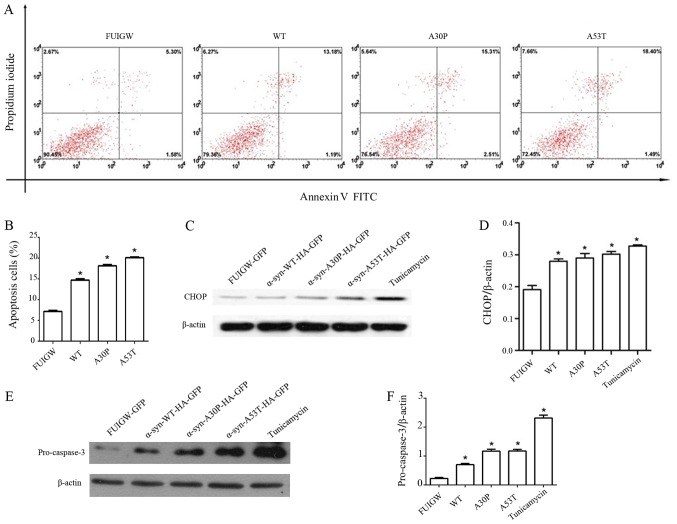

Although the exact molecular mechanism remains speculative, several lines of evidence indicate that the accumulation of misfolded α-syn within ER induces ER stress and, ultimately, neuronal apoptosis, which contributes to neurodegeneration in PD (11). The results of this study demonstrated that ER stress and Golgi injury were present in astrocytes overexpressing α-syn. To confirm whether apoptosis was induced by the overexpression of α-syn, 7 days after infecting the primary rat astrocytes with lentiviral vectors overexpressing wild-type α-syn, mutant proteins and GFP-FUIGW, respectively, we performed Annexin V and PI double staining followed by flow cytometry. The results revealed four groups of astrocytes in varying stages of apoptosis (Fig. 4A). Quantitative analyses revealed that the overexpression of wild-type or mutant α-syn caused a 2-fold increase of the apoptosis rate relative to the control group (Fig. 4B). Different lines of evidence have shown that CHOP mediates apoptosis during ER stress (17,40). Given this, we further examined the levels of CHOP and cleaved caspase-3 by western blot. Comparing with astrocytes expressing GFP-FUIGW, the ones overexpressing either wild-type or mutant α-syn had higher CHOP and cleaved caspase-3 levels (Fig. 4C-F). These results suggest that ER stress induced by the overexpression of α-syn in astrocytes might further lead to apoptosis through a CHOP-mediated pathway.

Figure 4.

α-synuclein can induce the apoptosis of astrocytes. Apoptosis was measured by a flow cytometry assay. (A) Apoptosis was observed in 4 groups: The control group, the α-syn-WT transfected group, the α-syn-A30P transfected group and the α-syn-A53T transfected group. (B) Statistical analysis of the percentage of apoptotic cells. (C) Cell lysates were prepared for western blot analysis of CHOP levels. (D) Integrated density values for CHOP relative to β-actin. (E) Cell lysates were prepared for western blot analysis of pro-caspase-3 levels. (F) Integrated density values for pro-caspase-3 relative to β-actin. The bars represent mean values ± standard deviation. *P<0.05 vs. FUIGW (negative control). α-syn, α-synuclein; WT, wild-type; HA, influenza A hemagglutinin; GFP, green fluorescence protein; CHOP, CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein homologous protein.

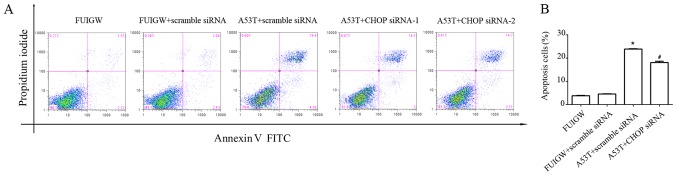

Inhibiting of CHOP partially decreases the apoptosis induced by overexpression of A53T

CHOP plays a convergent role in the UPR and it has been identified as one of the most important chaperonins mediated ER stress-induced apoptosis (41). We took a direct approach to knockdown CHOP gene to examine its effect on ER stress-induced apoptosis. As shown in Fig. 5, overexpression of A53T increased apoptosis in astrocytes compared with the control cells. The apoptotic effect of overexpressed A53T was partially decreased by knocking down CHOP with siRNA compared with A53T-mutant type transduced with scrambled siRNA. Combine with the previous results, parallel to the CHOP-mediated pathway, overexpression of A53T in astrocytes may lead to apoptosis through other pathways.

Figure 5.

Effect of inhibiting CHOP on apoptosis in the astrocytes overexpressed A53T. Apoptosis was measured by flow cytometry assay. (A) Apoptosis was observed in 4 groups: The negative control expressing FUIGW, cells expressing FUIGW stably transduced with scramble siRNA, cells expressing A53T stably transduced with scramble siRNA and cells expressing A53T stably transduced with CHOP siRNA. (B) Statistical analysis of the percentage of apoptotic cells. *P<0.05 vs. FUIGW (negative control); #P<0.05 vs. A53T+scramble siRNA. CHOP, CCAAT-enhancer-binding protein homologous protein; siRNA, small interfering RNA; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate.

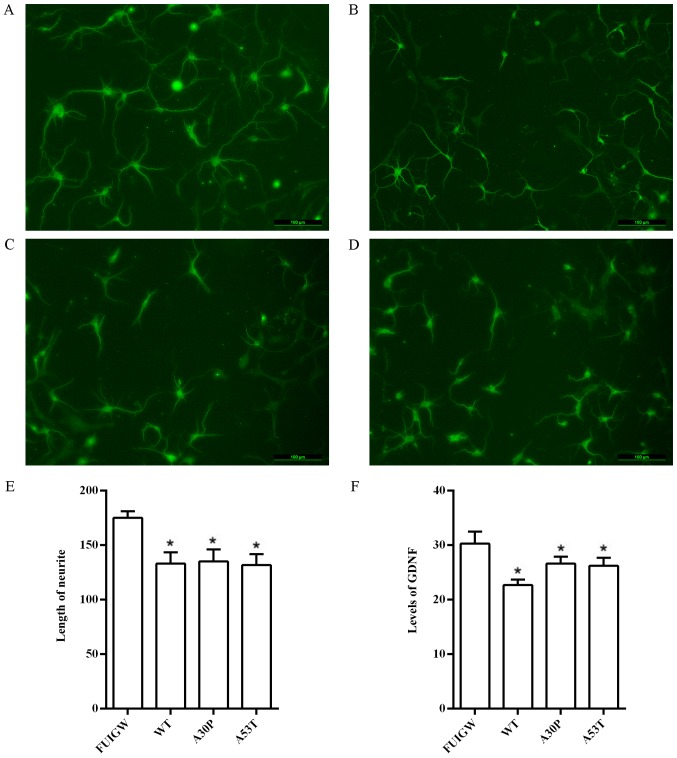

Overexpression of wild-type or mutant α-syn in astrocytes inhibits neurite outgrowth likely by reducing the secretion of GDNF

Our work demonstrated that the overexpression of wild-type or mutant α-syn in astrocytes causes ER-Golgi dysfunction and even induces apoptosis. In recent years, increasing evidence appears to suggest that astrocytes can also regulate neuronal activity and synaptic transmission and plasticity, and are thus far from being mere passive supportive cells (42). We therefore presumed that astrocyte dysfunction may affect the outgrowth and function of neighboring neurons. To investigate the relationship of dysfunctional astrocytes and neurite outgrowth, we co-cultured cortical neurons with the primary rat astrocytes overexpressing wild-type or mutant α-syn in Transwell cell culture inserts containing a permeable collagen-coated PTFE membrane. After 4 days, neurites were clearly identified under the fluorescence microscope upon immunostaining with an antibody against MAP2 (Fig. 6A-D). The lengths of the longest neurites of 100 neurons were measured using the Image J software, and statistical analysis suggested that the neurons in the control group had significantly longer neurites than the neurons co-cultured with astrocytes overexpressing α-syn (Fig. 6E). The results thus demonstrated that the overexpression of α-syn in astrocytes can attenuate neurite outgrowth, at least in vitro.

Figure 6.

Effect of overexpressing α-syn in astrocytes on the GDNF levels and neurite outgrowth. Neurites were clearly identified under the fluorescence microscope via immunostaining with an anti-MAP2 antibody: (A) Negative control group (FUIGW-GFP), (B) α-syn-WT-HA group, (C) α-syn-A30P-HA group and (D) α-syn-A53T-HA group. Scale bars, 100 µm. (E) The length of the neurites was quantified using ImageJ software. (F) The levels of GDNF in the supernatants were measured by ELISA. The bars represent mean values ± standard deviation. *P<0.05 vs. FUIGW (negative control). α-syn, α-synuclein; WT, wild-type; HA, influenza A hemagglutinin; GFP, green fluorescence protein; GDNF, glia-derived neurotrophic factor.

Astrocytes have the ability to synthesize and secrete a variety of neurotrophic factors, which are thought to play a prominent role in regulating the growth of neurons (43). The question is therefore prescient whether the inhibition of neurite outgrowth involves a decrease of the secretion of neurotrophic factors from astrocytes induced by the overexpression of wild-type or mutant α-syn. To investigate this question, we further measured the effects of α-syn on the secretory function of astrocytes. GDNF, a neurotrophic factor which is intimately related to PD (44), was chosen as an efficient evaluation index. We therefore infected primary rat astrocytes with lentiviral vectors overexpressing wild-type and mutant α-syn, as well as GFP-FUIGW as a control, and measured the levels of GDNF in the cell culture supernatants 7 days after infection using a commercially available ELISA kit. We found that the levels of GDNF were significantly lower in primary rat astrocytes overexpressing wild-type or mutant α-syn than in the control group (Fig. 6F). These findings indicate that the overexpression of α-syn can decrease the secretion of neurotrophic factors, as observed for GDNF. Taken together, the data indicate that the inhibition of neurite outgrowth may be linked to the diminished secretion of neurotrophic factors by astrocytes that accumulate α-syn.

Discussion

Aberrant aggregation of α-syn in neurons, resulting in the so-called Lewy bodies (LBs), is a defining feature of idiopathic and most autosomal dominant forms of PD (45). Homeostasis can be reestablished upon abnormal aggregation of α-syn via induction of the UPR and the autophagy-lysosome pathway (ALP) (11). However, when α-syn inclusions overwhelm the ability of the degradation pathway to successfully process and remove excess α-syn, oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage and ER stress are triggered (41). In spite of the apparent relevance of these mechanisms in astrocytes, most studies have focused on dopaminergic neurons, and we presently have only a limited understanding of the relationship between α-syn and astrocytes. In addition, astrocytes play a key role in neuron physiology, including trophic support, gliotransmission and antioxidant activity (46,47). Therefore, we studied the effects of α-syn on physiological processes in primary rat astrocytes and their relation to the growth of co-cultured neurons.

It should be noted that the ER stress response can be triggered by a variety of conditions that disturb folding of proteins in the ER (10). The thus induced stress can be reversed by the UPR, which aims to clear unfolded proteins and restore ER homeostasis (11). BiP assists the folding of proteins and regulates the activity of transmembrane-signaling proteins during ER stress (48). IRE1, PERK, and ATF6 are the three transmembrane signaling proteins that associate with BiP in their inactive state, in resting cells. In conditions of ER stress, BiP is sequestered through binding to unfolded or misfolded proteins, which lead to the releasing from IRE1/PERK/ATF6 and activation of ER stress sensors. BiP/GRP78 expression is therefore widely used as a marker for ER stress (49). The three UPR transmembrane signaling proteins, as mentioned above, use unique mechanisms of signal transduction to regulates the expression of various transcriptional factors and signaling events to adapt to ER stress (40). We only explored the effect of overexpression of α-syn in astrocytes on the PERK branch of UPR and the impact of CHOP on apoptosis. The ATF6 and the IRE1 branches of UPR were not examined. We used western blot analysis to show that there was a significant increase in the levels of BiP in astrocytes overexpressing α-syn, which indicated that ER stress was caused by the overexpression of α-syn in astrocytes.

If the UPR fails, impaired protein homeostasis can lead to chronic ER stress which induces cell death (19). At least three apoptosis pathways are known to be involved in the cell apoptotic. The first is transcriptional activation of the gene for CHOP. The second is activation of the cJUN NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway. The third is activation of ER-associated caspase-12 (17). CHOP appears to be a crucial proapoptotic factor found at the convergence point in the regulatory network used to initiate apoptosis caused by ER stress. Further investigations in our test suggested that ER stress contributed to the activation of CHOP and induced apoptosis. CHOP−/− astrocytes overexpressing A53T were partially resistant to ER stress-mediated apoptosis, suggesting the presence of other pathways mediating apoptosis in astrocytes overexpressed wide-type and mutant α-syn besides the CHOP signaling pathway. Further studies are warranted to investigate the role of other pathways in α-syn induced apoptosis of astrocytes. Previous work revealed the that pro-apoptotic transcriptional factor CHOP activates the expression of apoptosis-related proteins such as GADD34, TRAIL receptor-2, and endoplasmic reticulum oxidoreductase-1 (Ero1α) (11). Another possible mechanism by which CHOP induces apoptosis is via direct inhibition of Bcl-2 transcription and induction of the expression of the pro-apoptotic BH3-only protein (Bim) (11).

Immunostaining with an antibody against GM130 revealed Golgi fragmentation in astrocytes overexpressing α-syn under laser confocal microscopy, which demonstrated that the overexpression of α-syn in astrocytes induced Golgi damage. Mukherjee et al (50) stated that the fragmentation of GA is an early event during apoptosis that occurs independently of major changes of the cytoskeleton. Human and animal studies have shown clear evidence of morphological changes of GA in neurons affected by a variety of neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's disease (51) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (52,53). Fragmentation of GA may be explained by the fact that aggregated α-syn blocks ER-Golgi traffic, which leads to further cell defects (20).

In order to understand changes of neurite outgrowth in cocultures with astrocytes infected with lentiviral vectors overexpressing α-syn-A53T-HA-FUIGW-GFP, α-syn-A30P-HA-FUIGW-GFP, and α-syn-WT-HA-FUIGW-GFP, respectively, we established a primary neuronal-astroglial co-culture system in which primary neurons were seeded into the lower compartment of Transwell cell culture inserts, and primary rat astrocytes were grown in the upper compartment. Both primary neurons and primary rat astrocytes could not touch each other directly, but a permeable polycarbonate template membrane with 0.4 µm diameter between them allowed substrate exchange. As a member of the microtubules-associated protein family, MAP2 is involved in the formation of microtubules in neurons, and is consequently used to label neurites (54). Using immunofluorescence, we proved that the overexpression of either wild-type or mutant α-syn in astrocytes inhibited neurite outgrowth to a similar degree. We further showed that astrocytes overexpressing wild-type or mutant α-syn had reduced levels of GDNF. It is known that neurotrophic factors play an important role in the growth of neurites, differentiation of neurons, synaptogenesis, synaptic plasticity and maturation of electrophysiological characteristics (55). In fact, several neurotrophic factors are closely associated with PD, and this includes GDNF. GDNF specifically promotes the survival and morphological differentiation of dopaminergic neurons and increases their high-affinity dopamine uptake (44), which is more effective than other neurotrophic factors (56). A large number of tests have demonstrated that the suppression of GDNF could inhibit the neurites produced by neurons in vitro (56–59). According to our results, we hypothesized that diminished GDNF levels might account for the observed inhibition of neurite outgrowth, but the exact mechanism underlying it will require further experimental investigation. In addition, soluble proteins other than GDNF that are secreted by astrocytes also contribute to the growth of neurons (60). It is believed that functions of astrocytes depend on the amounts of proteins synthesized and secreted by the normal ER-Golgi compartment (47). Further evidence will be provided to demonstrate whether inhibition of neurite outgrowth by overexpression of α-syn in astrocytes can be rescued by supplement GDNF.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that the mutant α-syn (A53T and A30P) in astrocytes triggered ER stress via PERK/eIF2α signaling pathway. Astrocytes apoptosis were induced through a CHOP-mediated pathway. In addition, Golgi fragmentation was found in the process. Overexpressing wild-type or mutant α-syn in astrocytes significantly decreased the levels of GDNF, and partly inhibited neurite outgrowth. Further study of the effects of α-syn on astrocytes might help us understand the exact role of astrocytes in the pathogenesis of PD, possibly revealing novel therapeutic targets in the future.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by a grant from The Major State Basic Research and Development Program of China (973 Program; grant no. 2011CB510001), and grants from The National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81000542, 81200870, 30900469, 81430023, 81130021, 81371405, 31500832 and 81361120404), as well as The Science and Technology Program of Hunan province (grant no. 2014TT2014), and SRFDP (grant no. 20120162120079).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

All authors had full access to the data, and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. CW, JTan and LT contributed to the study conception and design. ML and LW performed the majority of the experiments, and LQ participated in the isolation and purification of primary rat astrocytes and cortical neurons. ML, LW, JTan and CW acquired the data. JTan, HZ, XS and JTang analyzed and interpreted the data. ML, LW and LQ drafted the manuscript. ML, JTan, CW and LQ critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. HZ, XS and JTang performed statistical analysis. CW, JTan and LT supervised the study and gave final approval of the version to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of State Key Laboratory of Medical Genetics.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Greenamyre JT. Glutamate-dopamine interactions in the basal ganglia: Relationship to Parkinson's disease. J Neural Transm Gen Sect. 1993;91:255–269. doi: 10.1007/BF01245235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kruger R, Kuhn W, Müller T, Woitalla D, Graeber M, Kösel S, Przuntek H, Epplen JT, Schöls L, Riess O. Ala30Pro mutation in the gene encoding alpha-synuclein in Parkinson's disease. Nat Genet. 1998;18:106–108. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Appel-Cresswell S, Vilarino-Guell C, Encarnacion M, Sherman H, Yu I, Shah B, Weir D, Thompson C, Szu-Tu C, Trinh J, et al. Alpha-synuclein p.H50Q, a novel pathogenic mutation for Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2013;28:811–813. doi: 10.1002/mds.25421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lesage S, Anheim M, Letournel F, Bousset L, Honoré A, Rozas N, Pieri L, Madiona K, Dürr A, Melki R, et al. G51D α-synuclein mutation causes a novel parkinsonian-pyramidal syndrome. Ann Neurol. 2013;73:459–471. doi: 10.1002/ana.23894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polymeropoulos MH, Lavedan C, Leroy E, Ide SE, Dehejia A, Dutra A, Pike B, Root H, Rubenstein J, Boyer R, et al. Mutation in the alpha-gene identified in families with Parkinson's disease. Science. 1997;276:2045–2047. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zarranz JJ, Alegre J, Gómez-Esteban JC, Lezcano E, Ros R, Ampuero I, Vidal L, Hoenicka J, Rodriguez O, Atarés B, et al. The new mutation, E46K, of alpha-synuclein causes Parkinson and Lewy body dementia. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:164–473. doi: 10.1002/ana.10795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pasanen P, Myllykangas L, Siitonen M, Raunio A, Kaakkola S, Lyytinen J, Tienari PJ, Pöyhönen M, Paetau A. Novel α-synuclein mutation A53E associated with atypical multiple system atrophy and Parkinson's disease-type pathology. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(2180):e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deng H, Yuan L. Genetic variants and animal models in SNCA and Parkinson disease. Ageing Res Rev. 2014;15:161–76. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin LJ, Pan Y, Price AC, Sterling W, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Price DL, Lee MK. Parkinson's disease alpha-synuclein transgenic mice develop neuronal mitochondrial degeneration and cell death. J Neurosci. 2006;26:41–50. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4308-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rao RV, Bredesen DE. Misfolded proteins, endoplasmic reticulum stress and neurodegeneration. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16:653–662. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colla E, Coune P, Liu Y, Pletnikova O, Troncoso JC, Iwatsubo T, Schneider BL, Lee MK. Endoplasmic reticulum stress is important for the manifestations of α-synucleinopathy in vivo. J Neurosci. 2012;32:3306–3320. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5367-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lai E, Teodoro T, Volchuk A. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: Signaling the unfolded protein response. Physiology (Bethesda) 2007;22:193–201. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00050.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi Y, Vattem KM, Sood R, An J, Liang J, Stramm L, Wek RC. Identification and characterization of pancreatic eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha-subunit kinase, PEK, involved in translational control. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:7499–7509. doi: 10.1128/MCB.18.12.7499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harding HP, Zhang Y, Ron D. Protein translation and folding are coupled by an endoplasmic-reticulum-resident kinase. Nature. 1999;397:271–274. doi: 10.1038/16729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harding HP, Zhang Y, Bertolotti A, Zeng H, Ron D. Perk is essential for translational regulation and cell survival during the unfolded protein response. Mol Cell. 2000;5:897–904. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80330-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oyadomari S, Mori M. Roles of CHOP/GADD153 in endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:381–389. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalia LV, Kalia SK, McLean PJ, Lozano AM, Lang AE. α-Synuclein oligomers and clinical implications for Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol. 2013;73:155–169. doi: 10.1002/ana.23746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonatas NK, Stieber A, Gonatas JO. Fragmentation of the Golgi apparatus in neurodegenerative diseases and cell death. J Neurol Sci. 2006;246:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooper AA, Gitler AD, Cashikar A, Haynes CM, Hill KJ, Bhullar B, Liu K, Xu K, Strathearn KE, Liu F, et al. Alpha-synuclein blocks ER-Golgi traffic and Rab1 rescues neuron loss in Parkinson's models. Science. 2006;313:324–328. doi: 10.1126/science.1129462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lim SY, Fox SH, Lang AE. Overview of the extranigral aspects of Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:167–172. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2008.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karpinar DP, Balija MB, Kügler S, Opazo F, Rezaei-Ghaleh N, Wender N, Kim HY, Taschenberger G, Falkenburger BH, Heise H, et al. Pre-fibrillar alpha-synuclein variants with impaired beta-structure increase neurotoxicity in Parkinson's disease models. EMBO J. 2009;28:3256–3268. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halliday GM, Stevens CH. Glia: Initiators and progressors of pathology in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2011;26:6–17. doi: 10.1002/mds.23455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barres BA. The mystery and magic of glia: A perspective on their roles in health and disease. Neuron. 2008;60:430–440. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faissner A, Pyka M, Geissler M, Sobik T, Frischknecht R, Gundelfinger ED, Seidenbecher C. Contributions of astrocytes to synapse formation and maturation-Potential functions of the perisynaptic extracellular matrix. Brain Res Rev. 2010;63:26–38. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haydon PG, Nedergaard M. How do astrocytes participate in neural plasticity? Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;7:a020438. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a020438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koehler RC, Roman RJ, Harder DR. Astrocytes and the regulation of cerebral blood flow. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:160–169. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silver J, Schwab ME, Popovich PG. Central nervous system regenerative failure: Role of oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, and microglia. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;7:a020602. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a020602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lundgaard I, Osório MJ, Kress BT, Sanggaard S, Nedergaard M. White matter astrocytes in health and disease. Neuroscience. 2014;276:161–173. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.10.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee HJ, Suk JE, Patrick C, Bae EJ, Cho JH, Rho S, Hwang D, Masliah E, Lee SJ. Direct transfer of alpha-synuclein from neuron to astroglia causes inflammatory responses in synucleinopathies. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:9262–9272. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.081125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.La Rocca R, Fulciniti M, Lakshmikanth T, Mesuraca M, Ali TH, Mazzei V, Amodio N, Catalano L, Rotoli B, Ouerfelli O, et al. Early hematopoietic zinc finger protein prevents tumor cell recognition by natural killer cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:4529–4537. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang C, Hu ZL, Wu WN, Yu DF, Xiong QJ, Song JR, Shu Q, Fu H, Wang F, Chen JG. Existence and distinction of acid-evoked currents in rat astrocytes. Glia. 2010;58:1415–1424. doi: 10.1002/glia.21017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shu Q, Hu ZL, Huang C, Yu XW, Fan H, Yang JW, Fang P, Ni L, Chen JG, Wang F. Orexin-A promotes cell migration in cultured rat astrocytes via Ca2+-dependent PKCα and ERK1/2 signals. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95259. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaech S, Banker G. Culturing hippocampal neurons. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2406–2415. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Su YR, Wang J, Wu JJ, Chen Y, Jiang YP. Overexpression of lentivirus-mediated glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in bone marrow stromal cells and its neuroprotection for the PC12 cells damaged by lactacystin. Neurosci Bull. 2007;23:67–74. doi: 10.1007/s12264-007-0010-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sugeno N, Takeda A, Hasegawa T, Kobayashi M, Kikuchi A, Mori F, Wakabayashi K, Itoyama Y. Serine 129 phosphorylation of alpha-synuclein induces unfolded protein response-mediated cell death. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:23179–23188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802223200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramirez IB, Lowe M. Golgins and GRASPs: Holding the Golgi together. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20:770–779. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seemann J, Pypaert M, Taguchi T, Malsam J, Warren G. Partitioning of the matrix fraction of the Golgi apparatus during mitosis in animal cells. Science. 2002;295:848–851. doi: 10.1126/science.1068064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fujita Y, Ohama E, Takatama M, Al-Sarraj S, Okamoto K. Fragmentation of Golgi apparatus of nigral neurons with alpha-synuclein-positive inclusions in patients with Parkinson's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2006;112:261–265. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0114-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sano R, Reed JC. ER stress-induced cell death mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833:3460–3470. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu C, Bailly-Maitre B, Reed JC. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: Cell life and death decisions. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2656–2664. doi: 10.1172/JCI26373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pérez-Alvarez A, Araque A. Astrocyte-neuron interaction at tripartite synapses. Curr Drug Targets. 2013;14:1220–1224. doi: 10.2174/13894501113149990203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oliveira SL, Pillat MM, Cheffer A, Lameu C, Schwindt TT, Ulrich H. Functions of neurotrophins and growth factors in neurogenesis and brain repair. Cytometry A. 2013;83:76–89. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin LF, Doherty DH, Lile JD, Bektesh S, Collins F. GDNF: A glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor for midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Science. 1993;260:1130–1132. doi: 10.1126/science.8493557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simón-Sánchez J, Schulte C, Bras JM, Sharma M, Gibbs JR, Berg D, Paisan-Ruiz C, Lichtner P, Scholz SW, Hernandez DG, et al. Genome-wide association study reveals genetic risk underlying Parkinson's disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1308–1312. doi: 10.1038/ng.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang DD, Bordey A. The astrocyte odyssey. Prog Neurobiol. 2008;86:342–367. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bélanger M, Magistretti PJ. The role of astroglia in neuroprotection. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2009;11:281–295. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.3/mbelanger. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tiffany-Castiglioni E, Qian Y. ER chaperone-metal interactions: Links to protein folding disorders. Neurotoxicology. 2012;33:545–557. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li J, Ni M, Lee B, Barron E, Hinton DR, Lee AS. The unfolded protein response regulator GRP78/BiP is required for endoplasmic reticulum integrity and stress-induced autophagy in mammalian cells. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:1460–1471. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mukherjee S, Chiu R, Leung SM, Shields D. Fragmentation of the Golgi apparatus: An early apoptotic event independent of the cytoskeleton. Traffic. 2007;8:369–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tillement JP, Papadopoulos V. Subcellular injuries in Alzheimer's disease. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2014;13:593–605. doi: 10.2174/18715273113126660197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sundaramoorthy V, Walker AK, Yerbury J, Soo KY, Farg MA, Hoang V, Zeineddine R, Spencer D, Atkin JD. Extracellular wildtype and mutant SOD1 induces ER-Golgi pathology characteristic of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in neuronal cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70:4181–4195. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1385-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fujita Y, Okamoto K, Sakurai A, Kusaka H, Aizawa H, Mihara B, Gonatas NK. The Golgi apparatus is fragmented in spinal cord motor neurons of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with basophilic inclusions. Acta Neuropathol. 2002;103:243–247. doi: 10.1007/s004010100461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dehmelt L, Halpain S. The MAP2/Tau family of microtubule-associated proteins. Genome Biol. 2005;6:204. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-6-1-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Airavaara M, Voutilainen MH, Wang Y, Hoffer B. Neurorestoration. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012;18(Suppl 1):S143–S146. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(11)70045-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jiao L, Zhang Y, Hu C, Wang YG, Huang A, He C. Rap1GAP interacts with RET and suppresses GDNF-induced neurite outgrowth. Cell Res. 2011;21:327–337. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Takaku S, Yanagisawa H, Watabe K, Horie H, Kadoya T, Sakumi K, Nakabeppu Y, Poirier F, Sango K. GDNF promotes neurite outgrowth and upregulates galectin-1 through the RET/PI3K signaling in cultured adult rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. Neurochem Int. 2013;62:330–339. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gavazzi I, Kumar RD, McMahon SB, Cohen J. Growth responses of different subpopulations of adult sensory neurons to neurotrophic factors in vitro. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:3405–3414. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zurn AD, Winkel L, Menoud A, Djabali K, Aebischer P. Combined effects of GDNF, BDNF, and CNTF on motoneuron differentiation in vitro. J Neurosci Res. 1996;44:133–141. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19960415)44:2<133::AID-JNR5>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sampaio TB, Savall AS, Gutierrez MEZ, Pinton S. Neurotrophic factors in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases: implications for pathogenesis and therapy. Neural Regen Res. 2017;12:549–557. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.205084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.