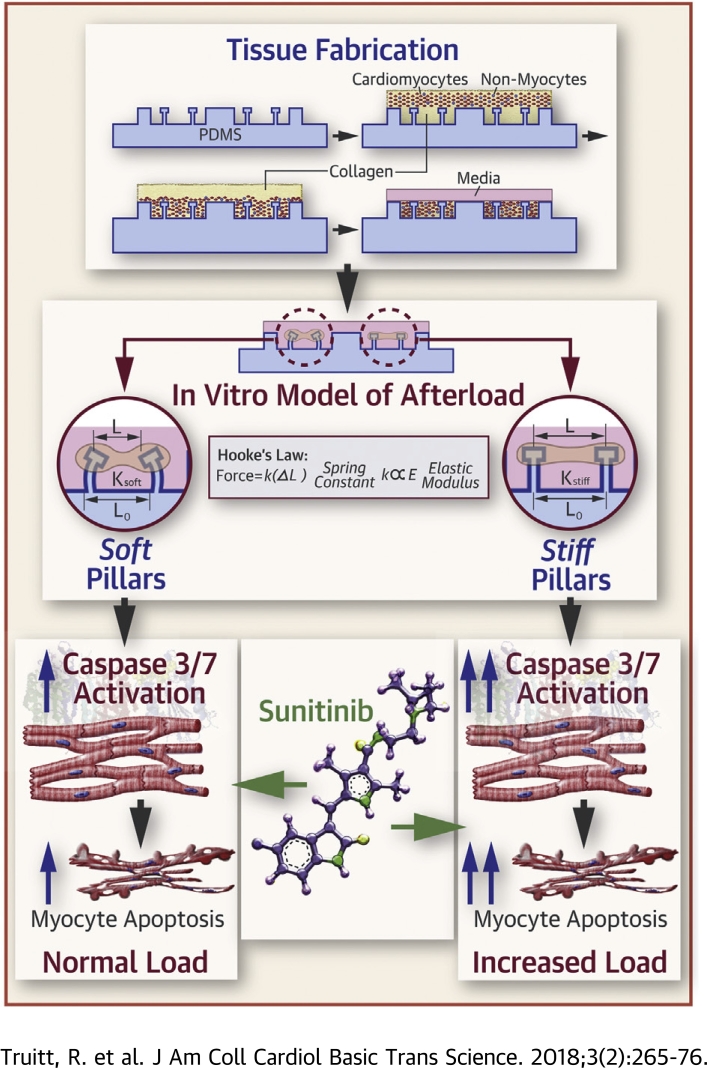

Visual Abstract

Key Words: afterload, apoptosis, cardiotoxicity, sunitinib, tissue engineering, toxicology, tyrosine kinase inhibitors

Abbreviations and acronyms: 2D, 2-dimensional; 3D, 3-dimensional; AICAR, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide 1-β-D-ribofuranoside; AMPK, adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; CCCP, carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazine; CMT, cardiac microtissue; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; EDTA, ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid; huMSC, human mesenchymal stem cell; Hu-iPS-CM, human induced pluripotent stem cell cardiomyocyte; iPS-CM, induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocyte; LV, left ventricle; NRVM, neonatal rat ventricular myocyte; PDMS, polydimethylsiloxane; RPMI, Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium; TMRM, tetramethylrhodamine

Highlights

-

•

Sunitinib, an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor used widely to treat solid organ tumors, frequently induces hypertension and causes LV dysfunction in up to 19% of treated individuals.

-

•

Sunitinib-induced cardiotoxicity can be modeled using engineered CMT.

-

•

In CMT, sunitinib induces dose- and duration-dependent activation of apoptosis pathways and decreases in CMT force generation, spontaneous beating, and mitochondrial membrane potential.

-

•

Exposure of CMT to increased in vitro afterload intensifies the cardiotoxicity of clinically relevant sunitinib concentrations.

-

•

These findings suggest that intensive antihypertensive therapy may be an appropriate strategy to mitigate LV dysfunction observed in patients treated with sunitinib.

Summary

Sunitinib, a multitargeted oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor, used widely to treat solid tumors, results in hypertension in up to 47% and left ventricular dysfunction in up to 19% of treated individuals. The relative contribution of afterload toward inducing cardiac dysfunction with sunitinib treatment remains unknown. We created a preclinical model of sunitinib cardiotoxicity using engineered microtissues that exhibited cardiomyocyte death, decreases in force generation, and spontaneous beating at clinically relevant doses. Simulated increases in afterload augmented sunitinib cardiotoxicity in both rat and human microtissues, which suggest that antihypertensive therapy may be a strategy to prevent left ventricular dysfunction in patients treated with sunitinib.

The rise of small molecule inhibitors targeting receptor tyrosine kinases that regulate tumor vasculature angiogenesis and cellular proliferation have resulted in important gains in cancer survival (1). However, many of these “targeted” therapies have unintended consequences on the cardiovascular system 2, 3, 4, 5. Sunitinib, a multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor used widely in the treatment of renal cell carcinoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, and neuroendocrine tumors, is currently under investigation in over 500 active clinical trials 6, 7, 8. However, among sunitinib-treated patients, hypertension occurs in 11% to 43% of patients and left ventricular (LV) dysfunction in up to 19% 9, 10, 11. These toxicities, although often manageable, can result in dose reduction or treatment interruption, which can affect oncologic outcomes.

Cardiovascular toxicity with sunitinib has been hypothesized to be a result of off-target inhibition of receptor tyrosine kinases and mitochondrial function that are important for maintaining cardiovascular homeostasis 3, 6, 12, 13, 14, particularly during states of increased stress 15, 16, 17, 18, 19. However, the relative contribution of each of these factors remains poorly understood. Another contributing factor that may be critical in the development of LV dysfunction during sunitinib treatment is hypertension 20, 21, 22. More specifically, it is not clear whether hypertension unmasks LV dysfunction or actually lowers the threshold for sunitinib cardiotoxicity. We hypothesized that increased afterload augments the cardiotoxic effects of sunitinib.

Testing this hypothesis in humans would likely require substantial resources and involve ethical challenges with cohorts of patients with untreated hypertension. Current in vitro cell culture and animal models also suffer from limitations that minimize their usefulness for modeling how biomechanical influences affect sunitinib cardiotoxicity in humans 23, 24. Thus, we used an engineered in vitro 3-dimensional (3D) cardiac microtissue (CMT) model incorporating cardiomyocytes from neonatal rats or human pluripotent stem cells that self-assemble onto polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) pillars 25, 26. We used this system to characterize sunitinib cardiotoxicity using metrics for cell viability, mitochondrial dysfunction, and cardiac function, and examined how these characteristics are affected by sunitinib dose, treatment duration, and the magnitude of biomechanical loading.

Methods

CMT platform

CMT arrays were fabricated as previously described 25, 26 (Supplemental Appendix). Devices were cast from PDMS pre-polymer (5:1 to 15:1 base to curing agent ratio) to create devices with stiff and soft pillars, respectively. Unless otherwise stated, arrays used in this study were created using a 5:1 base to curing ratio of PDMS.

Microtissue seeding procedure

Microtissues derived from neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVM) were prepared, as previously described (26) (Supplemental Appendix). CMTs, derived from human-induced pluripotent stem cell cardiomyocytes (Hu-iPS-CM) were prepared in the same manner as rat CMT with a few exceptions. Specifically, monolayers of beating Hu-iPS-CM (days 16 to 30) were detached from culture plates using TrypLE Express (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts) for 7 to 10 min at 37⁰C with 5% CO2. Human mesenchymal stem cells (huMSC) were detached from culture plates with 0.05% Trypsin ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) for 5 min at 37⁰C with 5% CO2. Hu-iPS-CM and huMSC were mixed to create tissues composed of 93% CM per 7% huMSC. Tissues were maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium (RPMI) + 20% fetal bovine serum + 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin + 5 μmol/l Y27632 media for the first 24 h and then switched to RPMI + B27 (plus insulin) + 1% penicillin/streptomycin media, which was exchanged every 2 days. Experiments were performed on day 5 of microtissue culture.

Drug studies

Stock solutions (10 mmol/l) of Sunitinib malate (S-8803, LC Laboratories, Woburn, Massachusetts) were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (D12345, Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and were remade every 6 months to ensure biological activity. Stock solutions were diluted at least 1:1000 in media for experiments to avoid any DMSO-induced toxicity. Samples treated with DMSO at the same volume per volume percentage were used as control samples (vehicle). Microtissues treated with 1 μmol/l Staurosporine (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri) were used as a positive control for apoptosis (27). Carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP) (Sigma Aldrich) was used a positive control for mitochondria membrane potential disruption (28) at a concentration of 50 μmol/l and was incubated with cells for 30 min at 37⁰C. In a subset of experiments, 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide 1-β-D-ribofuranoside (AICAR) (Sigma Aldrich) was administered concurrently with sunitinib at a concentration of 1 mmol/l.

Caspase 3/7 activation

Activated caspase 3/7 levels were measured using the Caspase-Glo 3/7 assay (Promega Corporation, Madison, Wisconsin), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Microtissue arrays were washed with Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline (without Ca2+, Mg2+) to remove residual media. At least 6 to 12 tissues were collected per experimental sample. Samples were pipetted and vortexed to completely lyse tissues and analyzed on BioTek Synergy H1 Multi-Mode plate reader (Winooski, Vermont) equipped with Gen5.0 software.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was assessed by trypan blue exclusion (29). Briefly, whole microtissue arrays were digested in a 1 mg/ml collagenase IV (Gibco) solution in Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline (with Ca++, Mg++) with 10% fetal bovine serum for 15 min at 37⁰C to digest collagen I gel. Tissues were further broken down into single cells by dissociating with 0.05% Trypsin EDTA.

Microtissue force generation measurements

Static (diastolic) tension was inferred by measuring the displacement of pillars, as previously described (26). Images were acquired using a 10× Plan Fluor objective on a Nikon TE2000U inverted microscope equipped with QImaging Exi Blue camera (Surry, British Columbia, Canada) and NIS-Elements BR software (Nikon Instruments, Melville, New York). Images were taken from the bottom, middle, and top of the microwells. The width of a single cap (φ), as well as the separation between caps (S) and bases of pillars (B) was measured in ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland) in units of pixels. We derived the displacement (μm) of the pillar using the formula provided in Equation 1, where 0.1706 is the conversion factor between pixels and microns for the objective used in these experiments.

| (1) |

For active (systolic) tension measurements, fluorescence videos were captured and displacements of fluorescent beads imbedded into caps of pillars were traced in ImageJ as previously described (26).

Mitochondrial membrane potential measurements

NRVM were cultured in 24-well plates for 24 to 48 h post-isolation before any drug treatments. Cells were treated with 1 μmol/l sunitinib for 30 min to 24 h. Cells were labeled with 10 nmol/l tetramethylrhodamine (TMRM), methyl ester perchlorate (Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific) in serum-free media, as previously described (30). Samples were analyzed on a Beckman Dickinson LSRII Flow Cytometer equipped with a 488-nm blue laser for excitation and 575/26 emission filter to measure TMRM. Post-experimental analysis of data was performed using Flow Jo V10 software (FlowJo LLC, Ashland, Oregon). The TMRM high population within the TMRM positive plot was quantified using the 575/26 histogram plot, where a shift to the left indicates lower levels of TMRM fluorescence and therefore decreased mitochondrial membrane potential.

ATP assay

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) levels were quantified using the ATP assay from Calbiochem (EMD Millipore, Burlington, Massachusetts) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Using NRVM cultured in a conventional 2-dimensional (2D) format, plates were analyzed on a BioTek Synergy H1 Multi-Mode plate reader equipped with Gen5.0 software. To ensure that total protein content did not significantly vary between experimental samples, protein readings were performed using a Qubit system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

All graphs were plotted as mean ± SD; except for box-and-whisker plots where error bars extend from median to minimum and maximum values. Individual experiments measuring caspase 3/7 and ATP levels were conducted with 3 technical replicates per experimental sample. In experiments utilizing trypan blue exclusion, at least 100 cells were counted per measurement and both chambers of hemocytometer were assayed to give 2 technical replicates per experimental group. Measurements of microtissue function, such as force generation and electrical parameters, were assayed on individual tissues. We tracked the functional changes in individual tissues instead of performing a bulk average before and after treatment, and thus results will be presented as the percentage of change from baseline measurements conducted before treatment. For experiments using flow cytometry, at least 20,000 cells were analyzed per experimental sample, and the percentage of TMRM high cells was calculated from this population. Unpaired 2-tail Student t tests were performed when appropriate (GraphPad QuickCalcs, GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, California). To model the dose dependence of sunitinib-induced caspase 3/7 activation, caspase data was fit to a log2 function (y = a log2 x + b) using nonlinear regression in Microsoft Excel Solver (Redmond, Washington).

Results

Rat CMT demonstrate decreases in cell viability following sunitinib treatment

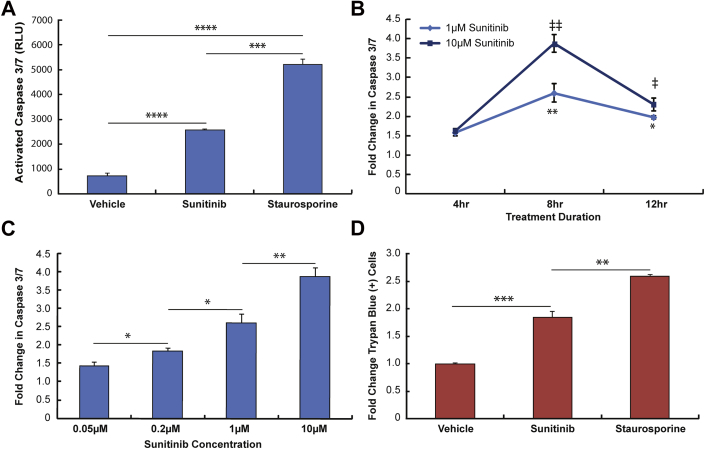

In CMT derived from NRVM, we first examined time- and dose-dependent effects of in vitro sunitinib exposure on apoptosis as indicated by caspase 3/7 activation. We found that a clinically relevant concentration of sunitinib (1 μmol/l) induced significant activation of caspases 3 and 7, though to a lesser degree than the positive control staurosporine did (Figure 1A). Also, we found that caspase activation reached a maximum level at 8 h in CMT treated with 1 μmol/l and 10 μmol/l sunitinib (Figure 1B). All subsequent experiments examined caspase 3/7 activation at 8 h regardless of dose.

Figure 1.

Detecting Changes in Cell Viability With Sunitinib Treatment Using a Rat CMT Model

(A) Activated caspase 3/7 levels in response to treatment with 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide (vehicle), 1 μmol/l sunitinib, or 1 μmol/l staurosporine for 8 h (dimethyl sulfoxide and sunitinib) or 6 h (staurosporine). ****p < 0.0001 relative to vehicle (n = 3 experiments); ***p < 0.001 1 μmol/l sunitinib versus staurosporine (n = 3 experiments). (B) Time-dependent changes in caspase 3/7 activation. Fold changes (relative to vehicle) in caspase levels for cardiac microtissues (CMT) treated with 1 μmol/l or 10 μmol/l sunitinib for 4 h, 8 h, or 12 h. **p < 0.01 1 μmol/l sunitinib 4 h versus 8 h; *p < 0.05 1 μmol/l sunitinib 4-h versus 12-h time points (n = 2 experiments for all time points); ‡‡p < 0.01 10 μmol/l sunitinib 4 h versus 8 h; ‡p < 0.05 10 μmol/l sunitinib 4-h versus 12-h time points (n = 2 experiments for all time points). (C) Dose-dependent changes in caspase activation in CMT treated with 50 nmol/l, 200 nmol/l, 1 μmol/l, 10 μmol/l sunitinib for 8 h. *p < 0.05 50 nmol/l versus 200 nmol/l sunitinib (n = 2 experiments); *p < 0.05 200 nmol/l versus 1 μmol/l sunitinib (n = 2 experiments for 200 nmol/l; n = 4 experiments for 1 μmol/l); **p < 0.01 1 μmol/l versus10 μmol/l sunitinib (n = 4 experiments for 1 μmol/l; n = 2 experiments for 10 μmol/l). (D) Detecting necrotic/late apoptotic cells. Percentages of cells stained with trypan blue were manually measured and normalized to vehicle levels to express as a fold change. **p < 0.01 10 μmol/l sunitinib versus 1 μmol/l staurosporine (n = 2 experiments); ***p < 0.001 vehicle versus 10 μmol/l sunitinib (n = 2 experiments for sunitinib; n = 3 experiments for vehicle). RLU = relative light units.

We determined that 50 nmol/l was the threshold concentration for caspase activation for our model and observed dose-dependent increases in caspase 3/7 activation in the range of 50 nmol/l to 10 μmol/l sunitinib (Figure 1C). Doses >10 μmol/l were not deemed physiologically relevant to humans given that the clinically observed concentrations of sunitinib in human blood are typically 0.1 to 1.9 μmol/l. We found that the degree of caspase activation correlated strongly with sunitinib dose (Figure 1C). Using nonlinear curve fitting methods, our results fit strongly with a logarithmic (log2) function that produced an R2 value >0.99 (Supplemental Figure 1). Finally, we found increased numbers of late apoptotic/necrotic cells in CMT treated with 10 μmol/l sunitinib as compared to vehicle (DMSO)-treated cells after performing a trypan blue exclusion (Figure 1D).

Collectively, these results demonstrate the ability of the rat microtissue model to detect decreases in viability due to sunitinib treatment that is dependent on sunitinib dose and treatment duration. These results also established the dose and treatment duration for subsequent experiments.

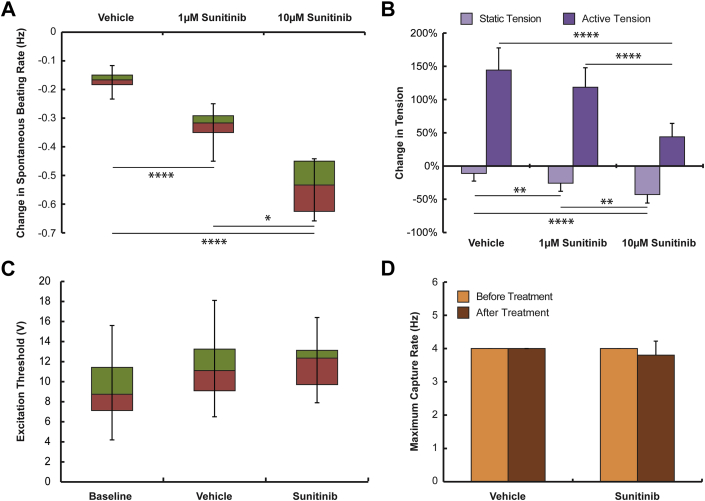

Rat CMT reveal changes in cardiac function following sunitinib treatment

Cardiomyocyte dysfunction remains an important toxicity of sunitinib treatment; however, there are a limited number of studies characterizing changes in myocyte force generation and electrophysiological properties. We found that 1 μmol/l sunitinib was sufficient to decrease the spontaneous beating rates of microtissues, and beating rates continued to decline in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2A), with complete arrest at 10 μmol/l sunitinib. Static (diastolic) forces generated by microtissues also decreased in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2B). We found that active (systolic) force generation increased during the 24-h period of observation in vehicle-treated tissues, with tissues treated with 10 μmol/l sunitinib showing significantly smaller increases in force generation (Figure 2B). When microtissues were subjected to field stimulation, we found neither significant differences in excitation threshold nor maximum capture rate between vehicle- and sunitinib-treated tissues (Figures 2C and 2D). These results suggest that the rat CMT model serves as a robust tool for early detection of drug-induced cardiotoxicity, because it can detect parallel changes in cell viability and cardiac function.

Figure 2.

Modeling Variations in Cardiac Function Following Administration of Sunitinib in Rat CMT

(A) Dose-dependent decreases in spontaneous beating rates following 24 h of treatment with 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide (vehicle n = 10 tissues), 1 μmol/l sunitinib (n = 11 tissues), or 10 μmol/l sunitinib (n = 11 tissues). ****p < 0.0001 versus vehicle; *p < 0.05 1 μmol/l sunitinib versus 10 μMmol/l sunitinib. (B) Dose-dependent decreases in static (diastolic) tension generated by CMT treated for 24 h with 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide (n = 12 tissues), 1 μmol/l sunitinib (n = 20 tissues), or 10 μmol/l (n = 10 tissues) sunitinib. **p < 0.01 vehicle versus 1 μmol/l sunitinib, 1 μmol/l sunitinib versus 10 μmol/l sunitinib; ****p < 0.0001 vehicle versus 10 μmol/l sunitinib. Decrease in active (systolic) tension with 10 μmol/l sunitinib treatment. ****p < 0.0001 vehicle (n = 4 tissues) or 1 μmol/l sunitinib (n = 5 tissues) versus 10 μmol/l sunitinib (n = 9 tissues). We did not observe any changes in excitation threshold (C) or maximum capture rate (D) following 24 h treatment with 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide or 10 μmol/l sunitinib. (A, C) Data are box-and-whisker plots; median-first quartile are plotted in red, third quartile-median are plotted in green, and error bars extend from median to minimum/maximum. Abbreviation as in Figure 1.

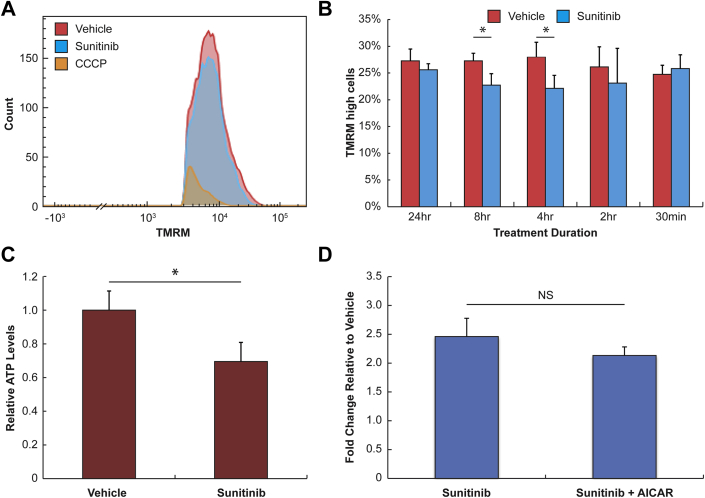

Sunitinib induces decreases in mitochondrial membrane potential and cellular ATP levels in rat CMT

Recognizing that mitochondrial dysfunction is a proposed mechanism of sunitinib cardiotoxicity, we assayed mitochondrial membrane potential in NRVM at various time points following treatment with 1 μmol/l sunitinib using TMRM and a flow cytometric analysis. We used CCCP, a known disruptor of mitochondrial membrane potential, as a positive control for these experiments. Figure 3A shows a typical histogram of TMRM levels in vehicle-treated, sunitinib-treated (1 μmol/l), and CCCP-treated (50 μmol/l) NRVM. The plot demonstrates significant decreases in mitochondrial membrane potential with 1 μmol/l sunitinib treatment, although this change is relatively modest compared with the change seen with CCCP-treated cells. We hypothesized that like caspase activation, mitochondrial membrane potential may also exhibit time-dependent changes; therefore, we quantified differences in mitochondrial membrane potential between vehicle- and sunitinib-treated cells across various time points (Figure 3B). We found significant decreases in mitochondria membrane potential at 4-h and 8-h treatment durations, but none before or after this time interval. Interestingly, these time points corresponded to peak caspase 3/7 activation. We also observed modest decreases in cellular ATP levels in NRVM treated with 1 μmol/l sunitinib (Figure 3C). Previous studies have identified the inhibition of adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activity as an off-target effect of sunitinib. We hypothesized that treating CMT with an AMPK activator, AICAR, could reverse caspase 3/7 activation. However, upstream activation of AMPK with AICAR was insufficient to attenuate caspase 3/7 activation in sunitinib-treated cells (Figure 3D). Our results reveal time-dependent changes in mitochondrial membrane potential with sunitinib treatment, which may contribute to observed decreases in cellular ATP levels.

Figure 3.

Characterizing Changes in Mitochondrial Function and Cell Energetics With Sunitinib Treatment

(A) Flow cytometry histogram showing levels of tetramethylrhodamine (TMRM). Neonatal rat ventricular myocytes grown in flat culture were treated with 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide (vehicle), 1 μmol/l sunitinib, or 50 μmol/l carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazine (CCCP) for 30 min (CCCP) or 4 h (dimethyl sulfoxide and sunitinib) and then were labeled with 10 nmol/l TMRM. (B) Time-dependent decreases in mitochondria membrane potential following treatment with 1 μmol/l sunitinib. Neonatal rat ventricular myocytes grown in flat culture were treated with 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide or 1 μmol/l sunitinib for 30 min to 24 h and labeled with TMRM to assess mitochondria membrane potential. *p < 0.05 (n = 3 experiments). (C) Decreases in adenosine triphosphate (ATP) levels in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes following 24 h treatment with 1 μmol/l sunitinib. *p < 0.05 (n = 3 experiments). (D) Upstream activation of adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase with molecule 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide 1-β-D-ribofuranoside (AICAR) did not reverse sunitinib-induced caspase activation in rat cardiac microtissues (n = 2 experiments). NS = not significant.

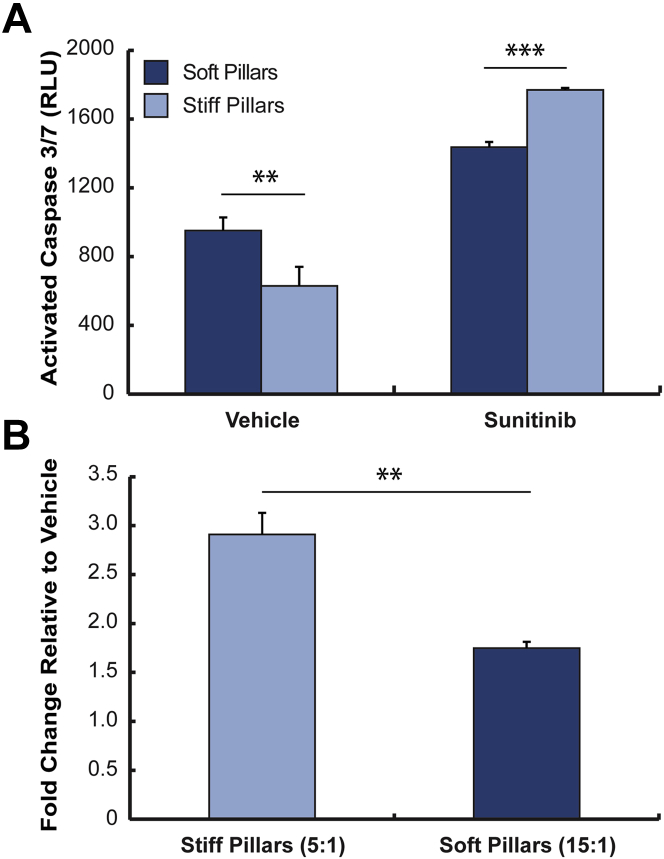

Cardiotoxic effects of sunitinib are augmented by increased in vitro afterload in the rat CMT model

Recognizing that the pillar stiffness is the primary load constraining active shortening of the CMT, we cultured CMT for 48 h on stiff (5:1 base-to-curing ratio) and soft (15:1 base-to-curing ratio) pillars and treated them with either 0.1% DMSO (vehicle) or 1 μmol/l sunitinib. Figure 4A shows caspase 3/7 activation for this experiment; in vehicle-treated CMT, we see greater caspase activation in soft pillars versus stiff pillars. However, in sunitinib-treated tissues, we observed greater caspase activation in stiff versus soft pillars, and that increased afterload augments sunitinib-induced caspase 3/7 activation (Figure 4B). These results suggest that increased in vitro afterload augments the myocardial toxicity associated with a given dose and duration of sunitinib.

Figure 4.

Using CMT to Assess the Contribution of Afterload to Observed Cardiotoxic Effects of Sunitinib

(A) Rat CMT cultured on stiff (5:1) or soft (15:1) pillars were treated with 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide (vehicle) or 1 μmol/l sunitinib for 8 h. Differences in active caspase 3/7 levels were observed between soft and stiff vehicle-treated CMT. **p < 0.01 (n = 3 experiments) and sunitinib-treated CMT. ***p < 0.001 (n = 3 experiments). (B) Results in (A) plotted as fold changes in active caspases 3/7 relative to vehicle-treated CMT. **p < 0.01 (n = 3 experiments). Abbreviations as in Figure 1.

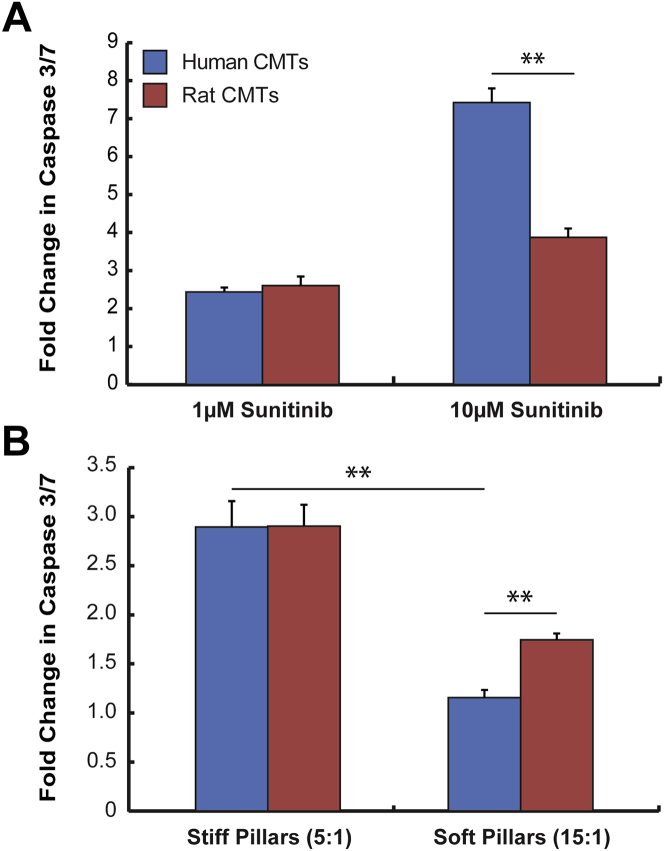

Human CMT exhibit afterload-dependent caspase 3/7 activation following sunitinib treatment

We examined the responses of CMT composed of Hu-iPS-CM to sunitinib. Human CMT treated with 10 μmol/l sunitinib for 8 h exhibited significant elevations in caspase 3/7 levels (Figure 5A). When we compared these responses to ones we obtained with rat CMT treated at the same concentration of sunitinib, we found that human CMT have nearly 3-fold greater caspase activation than rat CMT despite the absence of the established antiangiogenic sunitinib targets platelet-derived growth factor receptor-2 and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (Supplemental Figure 2). When human CMT are treated with a more physiologically relevant dose of sunitinib (1 μmol/l), we found that caspase activation is very similar to what we observed in rat CMT (Figure 5A). These results suggest that human CMT exhibit robust toxicity responses to sunitinib.

Figure 5.

Sunitinib Cardiotoxicity in CMT Composed of Human iPS-CM

Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (iPS-CM) were combined with 7% human mesenchymal stem cells to create human CMT. (A) Fold changes in activated caspase 3/7 levels of human CMT on stiff pillars treated 8 h with 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide (vehicle) or 1 μmol/l, 10 μmol/l sunitinib for 8 h compared with neonatal rat CMT. **p = 0.0116 10 μmol/l sunitinib human CMT (n = 2 experiments) versus neonatal rat CMT (n = 2 experiments). (B) Human CMT were cultured on stiff (5:1) or soft pillars (15:1) and treated with 1 μmol/l sunitinib for 8 h. Plotted are fold changes (relative to vehicle) in caspase 3/7 levels in human and rat CMT. **p < 0.01 human CMT on stiff versus soft pillars (n = 2 experiments); **p < 0.001 human CMT (n = 2 experiments) versus neonatal rat CMT (n = 3 experiments) cultured on soft pillars. Abbreviation as in Figure 1.

Next, we sought to address our hypothesis that increased in vitro afterload augments sunitinib cardiotoxicity in human CMT. Human CMT were cultured on both stiff and soft pillars for 5 days before being treated with 1 μmol/l sunitinib. Using caspase 3/7 activation as a metric for cardiotoxicity, we found that human CMT cultured on stiff pillars exhibited increased caspase 3/7 activation following sunitinib treatment (2.43 ± 0.11-fold vs. vehicle) compared with human CMT cultured on soft pillars (Figure 5B), which demonstrated minimal increases in caspase 3/7 levels (1.15 ± 0.08-fold vs. vehicle). Transcriptional profiling of fetal/hypertrophic genes prior to sunitinib exposure did not reveal significant expression differences based on pillar stiffness (Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental Figure 3). These findings suggest that increased in vitro afterload potentiates the toxicity of sunitinib without significantly altering the baseline myocyte phenotype. In summary, increased in vitro afterload augments sunitinib-induced caspase 3/7 activation in human CMT.

Discussion

Currently, more than 100,000 people have been treated with sunitinib, and there are over 500 open clinical trials with this drug listed at ClinicalTrials.gov; this fact stresses the need to improve our understanding of sunitinib-induced cardiotoxicity. Many basic and translational studies in cardio-oncology are constrained by inadequate preclinical models. Animal models do not allow for precise control over biomechanical and biochemical factors (31). Likewise, the use of 2D cell cultures also suffers from serious shortcomings, such as inability to apply mechanical pre-load and afterload, which are essential features of cardiac physiology (32). Taking advantage of recent advances in tissue engineering, we created 3D CMT that better mimic in vivo conditions without sacrificing control over cellular, biochemical, and mechanical inputs. Using the CMT platform, we successfully created a preclinical cardiomyocyte model for characterizing sunitinib toxicity and used this model to gain insights into the mechanisms of sunitinib toxicity. These studies establish a template for broader preclinical analysis of cardiomyocyte toxicity for the thousands of tyrosine kinase inhibitors currently in development.

First, we confirmed our CMT model could recapitulate previously observed increases in cell death with sunitinib treatment. We detected significant increases in caspase 3/7 activation following treatment of physiological doses of sunitinib, which is consistent with reports by others 33, 34. To our knowledge, we are the first to report that the degree of caspase 3/7 activation correlates logarithmically (log2) with sunitinib dose. Additionally, we confirmed that caspase activation was time-dependent, a finding that has also been reported by others (33). Our results also demonstrated that many of these early apoptotic cells go on to become nonviable, providing a basis for elevated troponin levels in patients (35), creatine kinase-myocardial band elevations in rodent studies (36), and increases in terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase 2′-deoxyuridine 5′-triphosphate nick end labeling–positive cells in in vitro NRVM studies (35).

Our microtissue model detected dose-dependent decreases in spontaneous beating rate and cessation of spontaneous contraction at 10 μmol/l sunitinib. We postulate that these dose-dependent decreases in beating may be connected to inhibition of human ether-à-go-go-related gene channels because this has been shown to result in arrhythmias in neonatal rodent cells 37, 38. We also observed dose-dependent decreases in static (diastolic) and active (systolic) tension generated by microtissues. These findings differ slightly from those of Rainer et al. (39) who reported decreases in systolic but not diastolic stresses in short-term (30 min) sunitinib experiments (doses ≥1.87 μmol/l) performed on human atrial muscle strips. These differences may be explained by the fact that reduced diastolic tension likely increased diastolic length, which could conceal decreases in systolic tension due to sunitinib, particularly in experiments where we treated with low doses of sunitinib (1 μmol/l).

In addition to creating a preclinical model for sunitinib cardiotoxicity, our studies provide insights about the mechanisms of this toxicity. First, our findings of toxicity in a CMT model that is not dependent on an intact circulation support the potential for direct toxicity of sunitinib, independent of vascular effects. These findings are consistent with the findings of Kerkela et al. (14) who implicated sunitinib-induced inhibition of cyclic AMPK as a mechanism for in vitro and in vivo cardiotoxicity with sunitinib. In this regard, the 1 μmol/l dose found to be consistently toxic in our studies was above the half maximal effective concentration for AMPK (0.216 μmol/l), as defined by Kerkela et al. (14). In addition, findings of modest, yet significant, decreases in mitochondrial membrane potential with sunitinib treatment complements patient biopsies showing swollen mitochondria and in vitro studies showing qualitative decreases in mitochondrial membrane potential at a single time point 14, 35, 40. Though sunitinib-induced caspase activation and changes in mitochondrial membrane potential appeared to peak at 8 h after exposure, reductions in spontaneous beating rate and force generation were most apparent at 24 h after initiation of sunitinib. This sequence suggests reductions in contractility are likely secondary to the metabolic disturbances and resulting cytotoxicity rather than a direct negative inotropic effect of sunitinib. It has been previously shown that activation of caspases 3 and 7 are key mediators of mitochondrial apoptosis events, such as decreases in membrane potential 40, 41, 42. Therefore, sunitinib may be directly affecting mitochondrial function or indirectly via caspase 3/7 activation. We further observed modest decreases in ATP levels, and these may be consequent to the changes in mitochondrial membrane integrity. Our findings of direct sunitinib-induced toxicity in vitro, do not preclude additional contributions of microvascular abnormalities in vivo. This might include defects in coronary flow reserve associated with pericyte loss, as implicated by Chintalgattu et al. (43) or attenuated increases in coronary capillary density during pressure overload, as implicated by Izumiya et al. (15). From this perspective, differences in rates of cardiotoxicity observed with alternative vascular endothelial growth factor–signaling pathway inhibitors might reflect differences in their potential for direct myocardial toxicity that could exacerbate the impact of in vivo microvascular effects.

The CMT model is particularly well suited for providing insight into whether increases in afterload augment cardiotoxic effects of sunitinib. We varied in vitro afterload by altering the stiffness of the pillars to which CMT are tethered and observed an increased magnitude of sunitinib-associated caspase activation with stiff pillars. When CMT are cultured on stiff pillars in the absence of sunitinib, we actually observed somewhat lower caspase activation, further supporting an interaction between sunitinib and increased in vitro afterload. Our results suggest that afterload is a key mediator of sunitinib’s effects on LV function. We believe these results have direct clinical implications: early administration of antihypertensive therapy to patients on sunitinib may be useful in preventing subsequent LV dysfunction.

Finally, we examined responses of Hu-iPS-CM to sunitinib. We found the human CMT exhibited significant activation of caspase 3/7 in response to 10 μmol/l sunitinib, more than 3× what we observed in rat CMT (Figure 5A). This difference is possibly species-related or maturation-related. Our results are in stark contrast to other studies using iPS-CM that required much higher concentrations of sunitinib to see decreases in cell viability (caspase activation and/or lactate dehydrogenase release) in 2D cultures (44). These differences may be due to differences in iPS-CM derivation and/or choice of culture platform (2D vs. 3D). However, our finding that increased in vitro afterload not only augments but is required for sunitinib-induced caspase 3/7 activation in human CMT (Figure 5B) suggests that the biomechanical loading intrinsic to the CMT model (and clinical sunitinib use) is an important regulator of sunitinib cardiac toxicity. The dependence of cardiotoxicity on in vitro afterload correlates well with clinical observations that development of LV dysfunction following sunitinib treatment is nearly always associated with hypertension. Our results suggest that human CMT may be the next step in improving our modeling of human sunitinib cardiotoxicity.

Study limitations

One limitation of this study is using neonatal rat cells to model adult human cardiotoxicity. In the absence of an adult human cardiomyocyte cell line, NRVM have been used for years and are able to recapitulate many aspects of human cardiac biology. Nevertheless, we will ultimately be limited by interspecies differences. Though cardiac myocytes derived from Hu-iPS mitigate the species difference, these cells are also functionally immature. Another limitation is the inability to discern whether cells are becoming “sick” due to sunitinib and cannot generate as much force per cell or whether there are fewer live cells contributing to force generation. However, our results clearly demonstrate a decrease in the beating rates of live cells in CMT treated with sunitinib. This result suggests that sunitinib is making cells “sick” and less functional. Hence, it may be possible that sunitinib is affecting myocyte force generation independent of myocyte attrition due to apoptosis. Finally, our culturing of CMT on pillars with increased stiffness does not fully mimic the complex in vivo characteristics of ventricular-arterial coupling in a pulsatile flow environment and an onset of hypertension that is coincident with sunitinib exposure. Additional CMT model refinement to permit dynamic increases in afterload that better match in vivo conditions would further enhance the clinical relevance of this in vitro model system.

Conclusions

Overall, we are the first to describe using a 3D-engineered tissue platform to model human sunitinib cardiotoxicity. We recapitulated decreases in myocyte viability and function described in previous studies and demonstrated, for the first time, a loss of mitochondrial membrane potential with sunitinib treatment. We demonstrated that increased in vitro afterload augments the cardiotoxic effects of sunitinib in both rat and human CMT, supporting recent endorsement of aggressive blood pressure control during treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (45).

Perspectives.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE: Many studies cite an association between developing hypertension and the eventual development of LV dysfunction during or after sunitinib treatment. The contribution of increased afterload to sunitinib’s cardiotoxic effects has been understudied. We report that increased afterload augments cardiotoxicity of sunitinib. Our results suggest that afterload reduction may be important for preventing eventual LV dysfunction in patients receiving sunitinib.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK: As tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as sunitinib continue to be widely used in the treatment of cancer, better preclinical models for identifying the risks and mechanisms of cardiotoxicity will be very important. We have created an in vitro model of sunitinib cardiotoxicity that allows us to identify effects on cell viability and cardiac function while accounting for biomechanical inputs. These models may also serve as robust tools for disease modeling.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the technical assistance of Dr. Rosa Álvarez, Dr. Wenli Yang of Penn Institute for Regenerative Medicine iPS core facility, and Charles (Hank) Pletcher from University of Pennsylvania Flow Cytometry core facility.

Footnotes

Supported by the National Center for Research Resources, grant UL1RR024134; the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, grant UL1TR000003; and in part by the University of Pennsylvania’s Institute for Translational Medicine and Therapeutics (ITMAT) Transdisciplinary Program in Translational Medicine and Therapeutics. Dr. Truitt received support from the American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship (11PRE7610168) and National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (2011125128) programs. Dr. Ky has received Pfizer’s Investigator Initiated Award. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

All authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the JACC: Basic to Translational Scienceauthor instructions page.

Appendix

References

- 1.Gschwind A., Fischer O.M., Ullrich A. The discovery of receptor tyrosine kinases: targets for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:361–370. doi: 10.1038/nrc1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Force T., Krause D.S., Van Etten R.A. Molecular mechanisms of cardiotoxicity of tyrosine kinase inhibition. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:332–344. doi: 10.1038/nrc2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah R.R., Morganroth J., Shah D.R. Cardiovascular safety of tyrosine kinase inhibitors: with a special focus on cardiac repolarisation (QT interval) Drug Saf. 2013;36:295–316. doi: 10.1007/s40264-013-0047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah R.R., Morganroth J. Update on cardiovascular safety of tyrosine kinase inhibitors: with a special focus on QT interval, left ventricular dysfunction and overall risk/benefit. Drug Saf. 2015;38:693–710. doi: 10.1007/s40264-015-0300-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gurevich F., Perazella M.A. Renal effects of anti-angiogenesis therapy: update for the internist. Am J Med. 2009;122:322–328. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faivre S., Demetri G., Sargent W., Raymond E. Molecular basis for sunitinib efficacy and future clinical development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:734–745. doi: 10.1038/nrd2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demetri G.D., Van Oosterom A.T., Garrett C.R. Efficacy and safety of sunitinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumour after failure of imatinib: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;368:1329–1338. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69446-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Motzer R.J., Hutson T.E., Tomczak P. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:115–124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Telli M.L., Witteles R.M., Fisher G.A., Srinivas S. Cardiotoxicity associated with the cancer therapeutic agent sunitinib malate. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1613–1618. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Di Lorenzo G., Autorino R., Bruni G. Cardiovascular toxicity following sunitinib therapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a multicenter analysis. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1535–1542. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zamorano J.L., Lancellotti P., Rodriguez Muñoz D. 2016 ESC Position Paper on cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity developed under the auspices of the ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines: the Task Force for cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2768–2801. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fabian M.A., Biggs W.H., Treiber D.K. A small molecule–kinase interaction map for clinical kinase inhibitors. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:329–336. doi: 10.1038/nbt1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laderoute K.R., Calaoagan J.M., Madrid P.B., Klon A.E., Ehrlich P.J. SU11248 (sunitinib) directly inhibits the activity of mammalian 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;10:1–8. doi: 10.4161/cbt.10.1.12162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerkela R., Woulfe K.C., Durand J.B. Sunitinib-induced cardiotoxicity is mediated by off-target inhibition of AMP-activated protein kinase. Clin Transl Sci. 2009;2:15–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2008.00090.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Izumiya Y., Shiojima I., Sato K., Sawyer D.B., Colucci W.S., Walsh K. Vascular endothelial growth factor blockade promotes the transition from compensatory cardiac hypertrophy to failure in response to pressure overload. Hypertension. 2006;47:887–893. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000215207.54689.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zentilin L., Puligadda U., Lionetti V. Cardiomyocyte VEGFR-1 activation by VEGF-B induces compensatory hypertrophy and preserves cardiac function after myocardial infarction. FASEB J. 2010;24:1467–1478. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-143180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chintalgattu V., Ai D., Langley R.R. Cardiomyocyte PDGFR-beta signaling is an essential component of the mouse cardiac response to load-induced stress. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:472–484. doi: 10.1172/JCI39434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hellstrom M., Kalen M., Lindahl P., Abramsson A., Betsholtz C. Role of PDGF-B and PDGFR-beta in recruitment of vascular smooth muscle cells and pericytes during embryonic blood vessel formation in the mouse. Development. 1999;126:3047–3055. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.14.3047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Di Siena S., Gimmelli R., Nori S.L. Activated c-Kit receptor in the heart promotes cardiac repair and regeneration after injury. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7:e2317. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernandes-Silva M.M., Shah A.M., Hedge S. Race-related differences in left ventricular structural and functional remodeling in response to increased afterload: the ARIC Study. J Am Coll Cardiol HF. 2017;5:157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen X.J., Sun X.L., Zhang Q. Uncontrolled blood pressure as an independent risk factor of early impaired left ventricular systolic function in treated hypertension. Echocardiography. 2016;33:1488–1494. doi: 10.1111/echo.13289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ozkan A., Kapadia S., Tuzcu M., Marwick T.H. Assessment of left ventricular function in aortic stenosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8:494–501. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2011.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Astashkina A., Mann B., Grainger D.W. A critical evaluation of in vitro cell culture models for high-throughput drug screening and toxicity. Pharmacol Ther. 2012;134:82–106. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seok J., Warren H.S., Cuenca A.G., for the Inflammation and Host Response to Injury Large Scale Collaborative Research Program. Genomic responses in mouse models poorly mimic human inflammatory diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:3507–3512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222878110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Legant W.R., Pathakb A., Yang M.T., Deshpande V.S., McMeeking R.M., Chen C.S. Microfabricated tissue gauges to measure and manipulate forces from 3D microtissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:10097–10102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900174106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boudou T., Legant W.R., Mu A. A microfabricated platform to measure and manipulate the mechanics of engineered cardiac microtissues. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18:910–919. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghelli A., Porcelli A.M., Zanna C., Rugolo M. 7-Ketocholesterol and staurosporine induce opposite changes in intracellular pH, associated with distinct types of cell death in ECV304 cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;402:208–217. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9861(02)00085-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nieminen A.L., Saylor A.K., Tesfai S.A., Herman B., Lemasters J.J. Contribution of the mitochondrial permeability transition to lethal injury after exposure of hepatocytes to t-butylhydroperoxide. Biochem J. 1995;307:99–106. doi: 10.1042/bj3070099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He Y., Huang 1, Farischon C. Combined effects of atorvastatin and aspirin on growth and apoptosis in human prostate cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2017;37:953–960. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nguyen P.D., Hsiao S.T., Sivakumaran P., Lim S.Y., Dilley R.J. Enrichment of neonatal rat cardiomyocytes in primary culture facilitates long-term maintenance of contractility in vitro. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;303:C1220–C1228. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00449.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Houser S.R., Margulies K.B., Murphy A.M. Animal models of heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Res. 2012;111:131–150. doi: 10.1161/RES.0b013e3182582523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma S.P., Vunjak-Novakovic G. Tissue-engineering for the study of cardiac biomechanics. J Biomech Eng. 2016;138:021010. doi: 10.1115/1.4032355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hasinoff B.B., Patel D., O'Hara K.A. Mechanisms of myocyte cytotoxicity induced by the multiple receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:1722–1728. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.050104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doherty K.R., Wappel R.L., Talbert D.R. Multi-parameter in vitro toxicity testing of crizotinib, sunitinib, erlotinib, and nilotinib in human cardiomyocytes. Toxicol Appl Pharamacol. 2013;272:245–255. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2013.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chu T.F., Rupnick M.A., Kerkela R. Cardiotoxicity associated with tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib. Lancet. 2007;370:2011–2019. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61865-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maayah Z.H., Ansari M.A., El Gendy M.A., Al-Arifi M.N., Korashy H.M. Development of cardiac hypertrophy by sunitinib in vivo and in vitro rat cardiomyocytes is influenced by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling pathway. Arch Toxicol. 2014;88:725–738. doi: 10.1007/s00204-013-1159-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin E.C., Holzem K.M., Anson B.D. Properties of WT and mutant hERG K channels expressed in neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H1842–H1849. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01236.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gilchrist K.H., Lewis G.F., Gay E.A., Sellgren K.L., Greg S. High-throughput cardiac safety evaluation and multi-parameter arrhythmia profiling of cardiomyocytes using microelectrode arrays. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2015;288:249–257. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2015.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rainer P.P., Doleschal B., Kirk J.A. Sunitinib causes dose-dependent negative functional effects on myocardium and cardiomyocytes. BJU Int. 2012;110:1455–1462. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.French K.J., Coatney R.W., Renninger J.P. Differences in effects on myocardium and mitochondria by angiogenic inhibitors suggest separate mechanisms of cardiotoxicity. Toxicol Pathol. 2010;38:692–702. doi: 10.1177/0192623310373775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lakhani S.A., Masud A., Kuida K. Caspases 3 and 7: key mediators of mitochondrial events of apoptosis. Science. 2006;311:847–851. doi: 10.1126/science.1115035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Safiulina D., Veksler V., Zharkovsky A., Kaasik A. Loss of mitochondrial membrane potential is associated with increase in mitochondrial volume: physiological role in neurones. J Cell Physiol. 2006;206:347–353. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chintalgattu V., Rees M.L., Culver J.C. Coronary microvascular pericytes are the cellular target of sunitinib malate-induced cardiotoxicity. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:187ra69. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohen J.D., Babiarz J.E., Abrams R.M. Use of human stem cell derived cardiomyocytes to examine sunitinib mediated cardiotoxicity and electrophysiological alterations. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2011;257:74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Armenian S.H., Lacchettti C., Barac A. Prevention and monitoring of cardiac dysfunction in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:893–911. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.5400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.