Abstract

Leveraging developments in microfabrication open new possibilities for optical manipulation. With the structural design freedom from three-dimensional printing capabilities of two-photon polymerization, we are starting to see the emergence of cleverly shaped ‘light robots’ or optically actuated micro-tools that closely resemble their macroscopic counterparts in function and sometimes even in form. In this work, we have fabricated a new type of light robot that is capable of loading and unloading cargo using photothermally induced convection currents within the body of the tool. We have demonstrated this using silica and polystyrene beads as cargo. The flow speeds of the cargo during loading and unloading are significantly larger than when using optical forces alone. This new type of light robot presents a mode of material transport that may have a significant impact on targeted drug delivery and nanofluidics injection.

Keywords: material transport, optical manipulation, thermal convection, two-photon fabrication

Introduction

It is a great challenge to build, power and control tiny machines to perform specific tasks1. One of the earliest demonstrations of tiny machines powered by chemical fuel is the catalytic nanorods. These are composed of platinum and gold at defined zones that catalyze the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) to propel them. Nickel is added to the nanorods so that they can be guided externally by magnets. The linear speed can reach up to 20 μm s−1 depending on the concentration of the H2O22, 3. An improvement on this design uses a rolled-up thin film of InGaAs/GaAs/Cr/Pt and can reach speed of up to 110 μm s−1. The rolled-up nanotools can be designed to perform corkscrew motions and have been demonstrated to be capable of penetrating a fixed HeLa cell4. 3D-printed ‘microfish’ using the same propulsion mechanisms has been demonstrated and applied in detoxification5. Recently, an approach for attaching living bacterial flagella motors in a synthetic structure has been presented6. The purpose was to construct a bio-hybrid micro-robot that can move autonomously or be guided by chemical gradients, and the synthetic structure could be designed to accommodate drug delivery. In these examples, chemicals introduced to the medium are utilized to drive the tiny machines. Chemical ‘fuel’ can provide high propulsion power; however, the challenge with these types of machines is the compatibility issues of the fuel with biological samples. Magnetic control requires the inclusion of nickel, which is inherently toxic to organic systems. Furthermore, magnetic and chemical gradient controls are difficult to realize for 3D-manipulation, and fine movements are very limited7, 8.

Light is an attractive mechanism for powering tiny machines. Advanced control over natural or fabricated micro- or nano-structures using light has been demonstrated throughout the years, starting with the pioneering work of Ashkin9. Developments in pulsed lasers, light-curing polymers and complex optical trapping mechanisms all serve to catalyze the advent of more complex light-based machines and thus the emergence of so-called light robotics10. The fabrication of a microscopic bull with nano-features by Kawata et al11 is a popular example of the precision and control that one can achieve with 3D-printing based on two-photon absorption of light sensitive polymers, with the earliest work dating back to the mid 90’s12. From then on, gradually more sophisticated micro- and nano-structures mimicking macroscopic tools have been first light-fabricated and subsequently light-actuated. A functional micro-oscillatory system has been made and proposed as a means to investigate the mechanical properties of minute objects11. There have been reports on microscopic gears13, 14, pumps15 and even sophisticated light foils16, 17 that were all first fabricated and subsequently driven by light only.

The hallmark of light robotics is the use of light for fabrication, active actuation and control. One approach, akin to traditional robotics, exploits materials that can exhibit light-activated contraction to work as artificial muscles. A typical example is the recently reported microscopic walkers, which use the contraction of liquid crystal elastomers for locomotion18. Another interesting modality is made possible through the use of parallel optical trapping, whether holographic19, 20, 21 or Generalized Phase Contrast (GPC) based22, 23, 24. Progress in optical manipulation has been boosted by novel technologies, such as graphics processing units and advanced spatial light modulators, which can enable the real-time calculation and generation of multi-beam trapping configurations25. Advanced optical traps can be controlled independently or orchestrated to move a plurality of microscopic objects simultaneously within an imaged plane or even in an extended volume. This has been successfully demonstrated in applications for optical assembly26, 27, 28 and particle sorting29, 30, 31. An early demonstration of the feasibility of light robotics is the real-time 3D manipulation of custom-fabricated micro-tools made from silica32. The micro-tools were optically translated, rotated and tilted, thus demonstrating all six-degrees-of-freedom, which is a crucial requirement for light robotics to perform delicate tasks such as surface imaging and force measurements33, 34. Surface imaging has been further improved with two-photon fabricated tools to the level where the achieved lateral resolution is ~200 nm, and the depth resolution is an impressive 10 nm35, 36. Our former work on light robotics that provides targeted-light delivery utilized two-photon fabricated waveguide structures that are optically manipulated to confine and redirect weakly focused incident light to illuminate specific targets orthogonal to the original light propagation. The nanometric feature sizes that can be achieved using two-photon fabrication tightly confine the redirected light radiating from the tip of free-floating waveguides, thus achieving targeted focusing that is stronger and tighter than what the objective lenses in the optical setup can normally provide37, 38. Other functionalities, such as surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy39 and fluorescence enhancement40, have been demonstrated using metal-coated micro-tools. The flexibility in microfabrication even allows the possibility to optimize the shape of micro-tools to maximize momentum transfer16, 41, 42, 43 or force clamping36, 44. Similar optimizations can be made for trapping light by using position clamping45, efficient illumination46, 47 or adaptive structured illumination48.

Here, we present a new generation of light-driven micro-robots with a novel and disruptive functionality embedded inside the micro-structure. Aside from using light to impart momentum to the trapped micro-tool, we use light to generate and control secondary hydrodynamic effects by heating an embedded thin metal layer within the body of the tool itself. Thermal convection currents occur inside the micro-structure, which, in turn, draw fluid together with potential fluid-borne cargo in or out of its body. This loading/unloading functionality and maneuverability make it suitable as a mode of material transport that can present new and important mechanisms in nanofluidics and drug delivery. This new functionality has the advantages of optical manipulation, such as the ability to work in sealed environments—microfluidic channels, and being able to work around optical constraints, such as refractive index contrast requirements and absorption effects in the particles being manipulated. Although thermal heating of metal surfaces49 and particles50, the use of bubbles as valves49 and fluid mixing using convection currents51 have already been demonstrated, our work is, to the best of our knowledge, the first attempt to integrate the aforementioned functionalities in a self-contained light-printed and light-driven micro-robot.

Materials and methods

Fabrication of micro-tools

The fabrication process of the micro-tools is summarized in Figure 1. The shape of each micro-tool is designed to work as a tiny vessel for material transport. Cargo may be loaded and unloaded through an opening at the anterior part of the structure. Spherical handles are added to the structure for optical trapping and manipulation. The micro-tools are fabricated via two-photon direct laser writing using a commercial fabrication setup (Nanoscribe Photonic Professional, Nanoscribe GmbH, Germany). Photoresist (IP-L 780) is prepared over a microscope cover slip by simple drop casting. Normally, structures for two-photon fabrication are designed using CAD or similar 3D rendering software and the volumetric data for the structure is then sliced to identify the layers to be printed. The fabrication proceeds by scanning back and forth, layer by layer, from bottom to top until the structure is fully printed. Although this approach works well for photonic structures, such as woodpile structures, it is very inefficient for our hollow micro-tools because the laser beam will only ‘write’ the outer shell, and there is a possibility of the structure appearing irregular due to this on-off switching of the scanning laser beam. The software for our fabrication setup accepts Cartesian coordinates to define the scanning trajectory, and we find that it is more efficient to use parametric equations to define the shape of our micro-tools52. The hollow body of the micro-tool is based on the surface of revolution of a so-called teardrop curve53, 54.

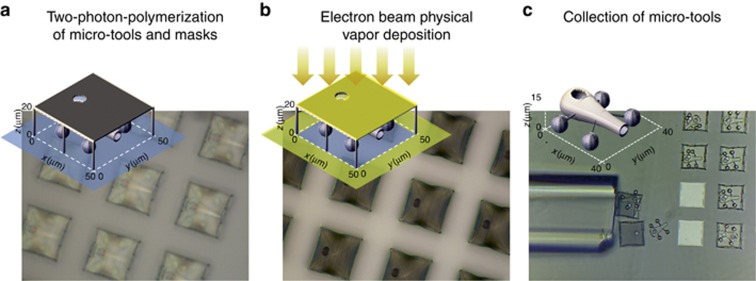

Figure 1.

Fabrication of micro-tools for material transport via enhanced light-induced thermal convection. (a) Each micro-tool is fabricated using the two-photon-polymerization process. A mask fabricated on top of each micro-tool defines the metal-coated region on the micro-tool. (b) After the micro-tools have been developed, a thin adhesion layer of titanium (1 nm) is first deposited, followed by a thin gold layer (5 nm), using electron beam physical vapor deposition. The mask shields the rest of the micro-tool and exposes only the region where the metal layer is going to be deposited (c) Selected micro-tools are collected by carefully dislodging and then drawing them into a fine glass capillary tube. They are subsequently loaded into a cytometry cuvette for trapping experiments. Each micro-tool has a footprint of 40 μm × 40 μm.

The body of the micro-tools has two openings. One serves as the spout of the micro-tool, where cargo can be loaded and ejected, and has a diameter of 6 μm. The other opening is located on top of each micro-tool body and has a diameter of 8 μm. The top opening enables subsequent deposition of a thin gold disk on the bottom inner wall of the micro-tool via electron beam vapor deposition. A mask with a matching hole is first fabricated to expose the target region while shielding the rest of the micro-tool during the deposition process. After two-photon exposure, the written structures are developed in a bath of isopropyl alcohol for 15 min. A second alcohol bath ensures that no photoresist remains inside the hollow body of each micro-tool.

The developed structures are subjected to electron beam physical vapor deposition to embed a thin metal layer inside the body of each micro-tool. First, a 1-nm layer of titanium is deposited as an adhesion layer, followed by a 5-nm layer of gold. The deposited metal layer is a circular disk with a diameter of 8 μm corresponding to the hole on the mask and on the micro-tool. More details regarding the fabrication can be found in the accompanying Supplementary Information.

Sample preparation

The fabricated micro-tools are anchored to the glass substrate. A fine glass capillary tube (Vitrocom, 80 μm × 80 μm inner cross section) fitted to a microliter syringe (Hamilton, 25 μl gas tight syringe) is used to remove the protective mask and collect selected micro-tools. The capillary tube-syringe assembly that we made is controlled by motorized actuators (Thorlabs, 6 mm DC actuators). Another motorized actuator controls the microliter syringe plunger to load microtools inside the capillary tube and, subsequently, unload them into a cytometry cuvette (Hellma, 250 μm × 250 μm inner channel cross section). The micro-tools are transferred into a cytometry cuvette containing a solution of deionized water, 0.5% Tween 80 surfactant and 10% ethanol. The process is performed under a microscope, and the transfer efficiency can be as high as 100% due to the selective and interactive picking approach. Video microscopy of the collection and transfer of micro-tools is provided as Supplementary Material. Unused micro-tools remain safely anchored to the substrate for succeeding experiments. Figure 1c shows that the masks have successfully shielded the micro-tools based on the bright square regions on the substrate (unexposed area) where the mask and micro-tool used to stand. Similar image analysis confirms that a circular disk was deposited inside the micro-tool.

Optical manipulation and light-induced thermal convection

Optical trapping and manipulation experiments are performed on our BioPhotonics Workstation (see Figure 2). The BioPhotonics Workstation uses multiple dual-beam optical traps, relayed to the sample through two opposing microscope objectives (Olympus LMPLN 50 × IR, WD=6.0 mm, NA=0.55), from multiple synchronized beams generated by a proprietary, computer-controlled illumination module. This illumination module uses a spatial light modulator to generate multiple beams out of a CW near-infrared (IPG Photonics, λ=1070 nm, 40 W max power). Up to 100 independently controllable dual beam traps can currently be generated. Each dual beam trap consists of two co-axial, counter-propagating beams. A trapped particle can be laterally manipulated by synchronously shifting the counter-propagating beams, whereas axial motion is controlled by changing the intensity ratio of these two beams. We have shown an earlier work how this optical trapping modality is able to manipulate a plurality of particles in 3D space55. In contrast to single beam optical tweezers, which use gradient forces from a tightly focused beam, counter-propagating beams use scattering forces and do not require tight focusing. This means that low numerical aperture objective lenses can be used in our workstation. Low numerical aperture objectives have long working distances and can thus accommodate bigger samples, such as our cytometry cuvette and side imaging37, if needed.

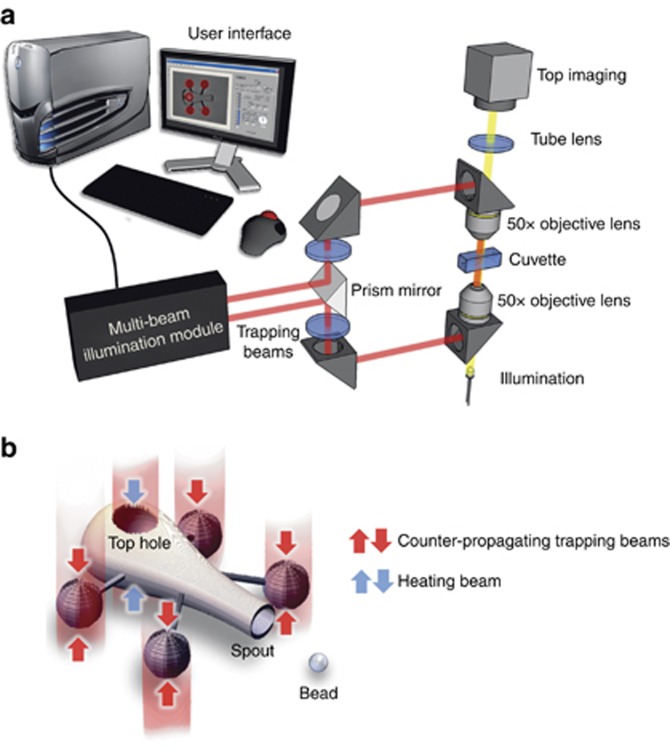

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram shows the BioPhotonics Workstation for optical trapping, manipulation and actuation of a micro-tool. (a) The BioPhotonics Workstation generates counter-propagating beam traps using a multi-beam illumination module. The top and bottom set of counter-propagating beams are imaged in the cuvette through opposing 50 × objective lenses. The top imaging is fed real-time to the user-interface for intuitive optical manipulation. (b) Once loaded in the cuvette, optical manipulation of the micro-tools is done using real-time configured counter-propagating beams for each sphere handle. The use of multiple trapping beams allows tool movements with full six-degrees-of-freedom actuation and is controlled using a LabVIEW-based user interface. An extra beam aimed at the micro-tool’s top hole is used for heating the thin metallic layer.

During experiments, a user traps and steers each micro-tool in three dimensions through an interactive computer interface, where an operator can select, trap, move and reorient them in real-time. With the aid of a LabVIEW-based graphical user interface, lateral manipulation is performed by simply dragging the traps, shown as overlay graphics over real-time images acquired from the microscope, whereas axial manipulation is performed by sliding a graphical control object.

For the optical manipulation of our micro-tools, we use four pairs of counter-propagating beams located at the four spherical handles. We can move the micro-tools at ∼ 10 μm s−1 and rotate them at 17° s−1. The BioPhotonics Workstation also generates an additional trapping beam, which is ‘repurposed’ to illuminate the thin metal layer inside each structure, which then serves as a light-activated heating element for the fluid inside the micro-tool. This additional beam controls the loading and unloading, which we will discuss in the next section. Convection becomes observable when the laser power at the sample is ∼ 17 mW. Videos of the experiments are obtained from the top-view (e.g., see Supplementary Material), and selected snapshots are presented in the manuscript.

Results and discussion

Each of our micro-tools was designed to function as a vessel that can be moved with optical traps in real-time. Proof-of-principle experiments demonstrate that each of them can be used to load and unload cargo using laser-induced thermal convection. When the thin metal layer is heated by one of the available trapping beams, we observe that the heat generated is enough to create a microbubble and produce strong convection currents that can pull silica (Ø=2 μm) and polystyrene (Ø=1 μm) beads toward the spout and into the tool. We show in Figure 3 an illustrative flow speed measurement for a silica bead, starting from outside the micro-tool until it enters the body. We observed flow speeds of ∼ 10 μm s−1 near the opening, which decrease as it moves toward the wider cross section, in accordance with the continuity equation. Near the heating element, the flow speed reaches more than 25 μm s−1. This is greater than previously reported flow speeds generated by two-photon fabricated rotors acting as micropumps15.

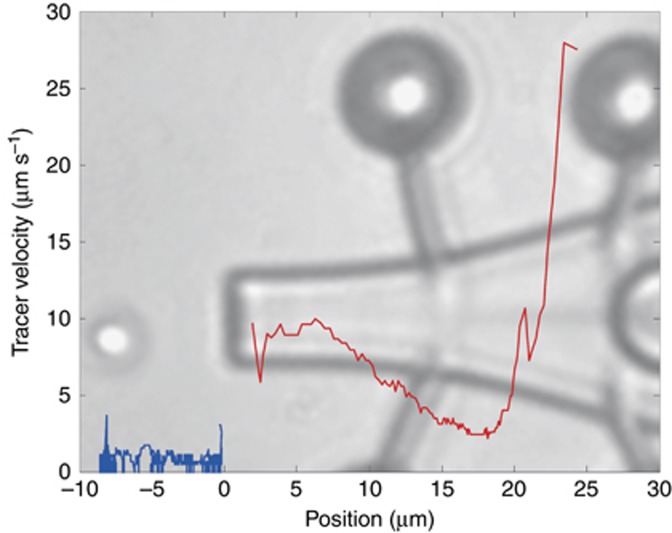

Figure 3.

Flow speed measurement. The thin metal layer inside the body of each micro-tool is heated using a laser beam (1070 nm), which, in turn, creates a microbubble and generates strong thermal convection currents that gradually draw the cargo toward the spout of the micro-tool. We use a feature tracking algorithm to monitor the movement of the beads. The zero position is set at the spout of the micro-tool. The clear gap observed in the velocity plot is due to the limitation of the tracking algorithm to identify the bead when it crosses the dark outline of the micro-tool. The blue and red plots represent the velocity of the bead while it is outside and inside of the micro-tool, respectively. An image of a micro-tool is added to give a scale-indication of the horizontal axis. See Supplementary Material.

Thermal convection due to photothermal heating involves both photonic and fluidic phenomena. Multi-physics computer modeling of plasmonic heating elements having dimensions of less than 200 nm predicts flow speeds of ∼ 10 nm s−1, and it has been suggested that heating elements should be greater than 1 μm for microfluidic applications56 (we used an 8-μm diameter disk). The convection current that draws particles into our micro-tools can be the combined result of natural and Marangoni convection57. The temperature gradient from the light-heated metal layer can directly create natural convection, but it can also create a surface tension gradient along a microbubble surface. The surface tension gradient due to the temperature difference between the top and bottom surfaces of a bubble leads to Marangoni convection, which can be very strong58. Once the particle touches the microbubble, surface tension force essentially traps the particle and thus prevents it from coming out. A study of particle assembly on a sandwiched colloidal suspension using Marangoni convection reports a maximum flow velocity at the gas/liquid interface as high as ~0.3 m s−1. Away from the bubble, there is a significant decrease in the velocity57. The trend in our flow speed measurement of a tracer particle while it is being dragged by the convective flow (Figure 3) is consistent with this observation. An increase of 1–2 orders of magnitude of the mass transfer has also been observed for dissolved molecules59.

Photothermal particles and thin metal films have been previously used in microfluidics for heat-induced flow control, sorting and mixing. However, the precise spatial control of particles’ motion and locations, such as placing them where and when they are needed, can be challenging for smaller particles60. Moreover, thin metal films deposited on fixed regions within microfluidic channels completely lack the maneuverability that we show here. In short, our approach demonstrates a solution to this challenge by integrating a thin metal film within each light-controlled micro-tool that can readily function to transport cargo.

In our experiments, laser-induced heating of the metallic layer is able to form a microbubble inside the body of each micro-tool. Such microbubble formation is known to occur at temperatures between 220 and 240 °C for an array of nanoparticles and is more or less invariant with the size of the illuminated area and incident laser power61. Moreover, we have observed that some of the polystyrene beads captured by a micro-tool can be melted by continuously heating the fluid. No damage has been observed on either micro-tools or metal layers due to the photothermal heating.

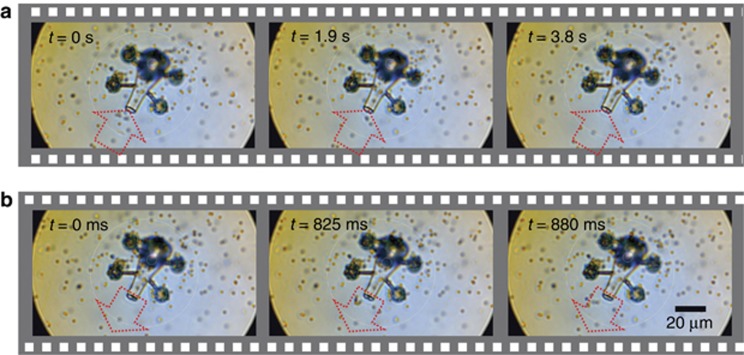

Continuous illumination generates strong thermal convection currents that pull surrounding particles toward a laser-induced microbubble. Others have shown the feasibility of exploiting this for material transport, e.g., direct-writing of patterned particle assemblies. It has been reported that dragging a microbubble with a heating CW laser beam can result in the collection and deposition of particles along its path to accomplish direct-writing of patterned particle assemblies62. Our tool utilizes the same principle, with the advantage of greater selectivity and control over the particle collection because the design of the tool limits the direction of convective flow. In Figure 4, we demonstrate spatial control of the micro-tool by picking up scattered silica beads. The particle velocities we have measured for our micro-tool are significantly larger than when using an optical trap alone. We have therefore exploited the conversion of optical energy to heat and, consequently, to kinetic energy via hydrodynamic effects to realize a new light-based micro-tool capable of performing controlled mechanical interactions with its surrounding micro-world in a way that goes beyond the limitations of conventional optical trapping. Whereas conventional optical trapping requires sufficient refractive index contrast between the captured particles and their surrounding medium, our method does not suffer from this inherent limitation. Potentially unwanted radiation effects to the sample can also be minimized or prevented.

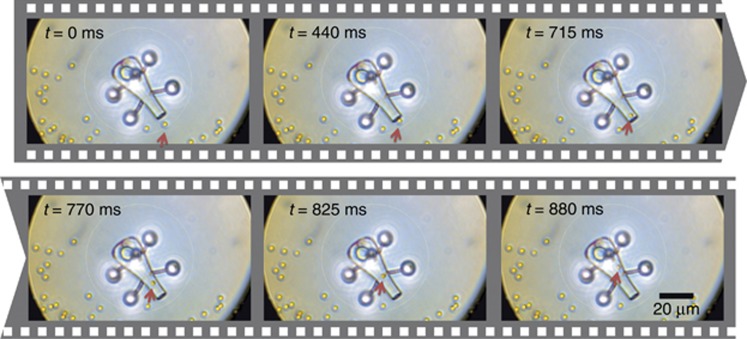

Figure 4.

Loading of cargo inside the micro-tool. Due to the spatial control provided by optical manipulation, the light robot can pick up cargo at different locations. See Supplementary Material.

Upon loading cargo inside the tool and conveniently moving the tool to another location via optical micromanipulation, our experiments show that we can also exploit light-induced processes to eject captured particles. Figure 5 shows experiment results demonstrating that the cargo can be ejected by slightly moving the heating beam across the body of the micro-tool to perturb the microbubble to pump fluids with the particles out of the structure. This functionality mimics the familiar action of pumping a syringe. It has been observed that bubbles get attracted to regions of higher temperature, a phenomenon called thermocapillary bubble migration58. The attraction of a bubble to a heat source is very strong (i.e., up to an order of magnitude stronger than optical forces); thus, it is feasible to use thermocapillary bubble migration as a control for pumping. Trapping of bubbles has also been observed in more viscous molten glass media, where deformation of the bubble is the proposed trapping mechanism63. Some simulations have shown that the Marangoni convection can reverse when there are many particles adhering to the bubble57. This reversal of the Marangoni convection may also be present during the unloading of cargo inside our micro-tools. Most studies have been done on unconstrained Marangoni convection, where there is a thin fluid film, and the boundary is only at the bottom or both top and bottom surfaces. For our micro-tool, the fluid is practically constrained in all directions, allowing only a small opening for the cargo and for the continuity of fluid flow to hold (i.e., top hole). Thus, we expect a nontrivial flow phenomenon that warrants further investigation. At this point, it suffices to say that the pumping action of the micro-tool is light-activated and, to our knowledge, this functionality has never been demonstrated before in a light-actuated micro-tool. Future work will explore new structure designs to optimize control over the convection processes constrained within them and even avoid ejecting particles out through the top hole, which occasionally happens in the current design (e.g., covering the top hole with mesh-like features after metal deposition).

Figure 5.

The micro-tool can be used as a tiny pump. (a) A relatively large number of polystyrene beads (1 μm diameter) are dispersed in the trapping medium, and the micro-tool is used to collect them. (b) By changing the location of the heating beam, the micro-tool can be used to eject the captured particles by using the microbubble as a light-controlled piston. See Supplementary Material.

Conclusion

Various methods and technologies can be integrated to build and control optically-actuated micro-tools or light robots that can perform specific tasks. Microfluidics, plasmonics, optical manipulation and fabrication have already found successful applications in their respective areas. However, combining them presents not only new challenges but also new and exciting ways to enable disruptive functionalities that would otherwise be difficult to realize by each sub-discipline in isolation. In this work, we have presented an integration of optical manipulation, two-photon fabrication and metal deposition to create a new category in the toolbox of light robotics. We have embedded thin metal layers inside a plurality of light-driven micro-tools that enable the conversion of incident optical energy into heat and eventually hydrodynamic effects. Heating the metal layers generates thermal convection currents that can be used to load and unload cargo. We have demonstrated that light-controlled pumping makes each micro-tool suitable for material transport. A potential application that can fully utilize the capability of our new micro-tools is drug delivery. Micro-machined devices with modified surface chemistry and morphology have already been successfully used in drug delivery64. Such devices are fabricated using a standard lithography process and have a planar geometry. However, using optically manipulated micro-sources can provide much better spatial and temporal selectivity, as shown by experiments on cell stimulation via chemotaxis65. Such examples motivate the idea of a structure-mediated approach in biological studies that use light-controlled, steered and actuated microstructures to mediate access to the sub-micron domain. Light robotics is thus an excellent candidate for realizing these new functionalities in a fully flexible and dynamic context. The structural design freedom in two-photon fabrication can even adopt micro-needle structures, which are commonly used for transdermal drug delivery66, as an approach to advanced intracellular drug delivery. There has been interest in understanding diseases such as circulating tumor cells, which are very rare in blood samples. Because of their rarity, bulk measurement will average out the unique signature of this type of cell67. Our micro-tools can work in plurality and even with other micro-tools of different functionality to probe this single cell to investigate cellular responses to spatially or temporally correlated mechanical or chemical stimulation.

Because the operation of our first batch of novel, internally functionalized micro-tools is based on photothermal heating, resonant plasmonic structures can be readily integrated and used in future light robotic tools for more efficient heating and wavelength selectivity. The metal coating can be added on the spout of the micro-tool and can also be heated up once in contact with a cell of interest. It has been proposed in transfection experiments that heating of the cell membrane induces phase changes in the lipid layer and thus allows the entry of foreign material. Our micro-tools do not preclude the possibility of being loaded prior to introduction to the trapping medium; thus, it is also possible to have micro-tools with different chemicals that can perform precise chemical stimulation that is not possible in a standard cell culture. We envision these micro-tools to be an important addition to the current tools for understanding biology at the micro-scale.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the Enhanced Spatial Light Control in Advanced Optical Fibres (e-space) project, financed by Innovation Fund Denmark (Grant No. 0603-00514B).

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary Information for this article can be found on the Light: Science & Applications' website(http://www.nature.com/lsa).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ozin GA, Manners I, Fournier-Bidoz S, Arsenault A. Dream nanomachines. Adv Mater 2005; 17: 3011–3018. [Google Scholar]

- Paxton WF, Kistler KC, Olmeda CC, Sen A St, Angelo SK et al. Catalytic nanomotors: autonomous movement of striped nanorods. J Am Chem Soc 2004; 126: 13424–13431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxton WF, Sundararajan S, Mallouk TE, Sen A. Chemical locomotion. Angew Chemie Int Ed 2006; 45: 5420–5429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solovev AA, Xi W, Gracias DH, Harazim SM, Deneke C et al. Self-propelled nanotools. ACS Nano 2012; 6: 1751–1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Li JX, Leong YJ, Rozen I, Qu X et al. 3D-printed artificial microfish. Adv Mater 2015; 27: 4411–4417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barroso Á, Landwerth S, Woerdemann M, Alpmann C, Buscher T et al. Optical assembly of bio-hybrid micro-robots. Biomed Microdevices 2015; 17: 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campuzano S, Kagan D, Orozco J, Wang J. Motion-driven sensing and biosensing using electrochemically propelled nanomotors. Analyst 2011; 136: 4621–4630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Guo JH, Xu XB, Fan DL. Recent progress on man-made inorganic nanomachines. Small 2015; 11: 4037–4057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkin A, Dziedzic JM, Bjorkholm JE, Chu S. Observation of a single-beam gradient force optical trap for dielectric particles. Opt Lett 1986; 11: 288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palima D, Glückstad J. Gearing up for optical microrobotics: micromanipulation and actuation of synthetic microstructures by optical forces. Laser Photon Rev 2013; 7: 478–494. [Google Scholar]

- Kawata S, Sun HB, Tanaka T, Takada K. Finer features for functional microdevices. Nature 2001; 412: 697–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruo S, Nakamura O, Kawata S. Three-dimensional microfabrication with two-photon-absorbed photopolymerization. Opt Lett 1997; 22: 132–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galajda P, Ormos P. Complex micromachines produced and driven by light. Appl Phys Lett 2001; 78: 249–251. [Google Scholar]

- Kelemen L, Valkai S, Ormos P. Integrated optical motor. Appl Opt 2006; 45: 2777–2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruo S, Inoue H. Optically driven micropump produced by three-dimensional two-photon microfabrication. Appl Phys Lett 2006; 89: 144101. [Google Scholar]

- Swartzlander GA, Peterson TJ, Artusio-Glimpse AB, Raisanen AD. Stable optical lift. Nat Photonics 2011; 5: 48–51. [Google Scholar]

- Glückstad J. Optical manipulation: sculpting the object. Nat Photonics 2011; 5: 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng H, Wasylczyk P, Parmeggiani C, Martella D, Burresi M et al. Light-fueled microscopic walkers. Adv Mater 2015; 27: 3883–3887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liesener J, Reicherter M, Haist T, Tiziani HJ. Multi-functional optical tweezers using computer-generated holograms. Opt Commun 2000; 185: 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Dufresne ER, Spalding GC, Dearing MT, Sheets SA, Grier DG. Computer-generated holographic optical tweezer arrays. Rev Sci Instrum 2001; 72: 1810–1816. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis JE, Koss BA, Grier DG. Dynamic holographic optical tweezers. Opt Commun 2002; 207: 169–175. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen RL, Daria VR, Glückstad J. Fully dynamic multiple-beam optical tweezers. Opt Express 2002; 10: 597–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo PJ, Daria VR, Glückstad J. Four-dimensional optical manipulation of colloidal particles. Appl Phys Lett 2005; 86: 074103. [Google Scholar]

- Ulriksen HU, Thøgersen J, Keiding S, Perch-Nielsen I, Dam J et al. Independent trapping, manipulation and characterization by an all-optical biophotonics workstation. J Eur Opt Soc Rapid Publ 2008; 3: 08034. [Google Scholar]

- Persson M, Engström D, Goksör M. Real-time generation of fully optimized holograms for optical trapping applications. Proc SPIE 2011; 8097: 80971H.

- Chapin SC, Germain V, Dufresne ER. Automated trapping, assembly, and sorting with holographic optical tweezers. Opt Express 2006; 14: 13095–13100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo PJ, Kelemen L, Alonzo CA, Perch-Nielsen IR, Dam JS et al. 2D optical manipulation and assembly of shape-complementary planar microstructures. Opt Express 2007; 15: 9009–9014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo PJ, Kelemen L, Palima D, Alonzo CA, Ormos P et al. Optical microassembly platform for constructing reconfigurable microenvironments for biomedical studies. Opt Express 2009; 17: 6578–6583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buican TN, Smyth MJ, Crissman HA, Salzman GC, Stewart CC et al. Automated single-cell manipulation and sorting by light trapping. Appl Opt 1987; 26: 5311–5316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MM, Tu E, Raymond DE, Yang JM, Zhang HC et al. Microfluidic sorting of mammalian cells by optical force switching. Nat Biotechnol 2005; 23: 83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perch-Nielsen I, Palima D, Dam JS, Glückstad J. Parallel particle identification and separation for active optical sorting. J Opt A Pure Appl Opt 2009; 11: 34013–34018. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo PJ, Gammelgaard L, Bøggild P, Perch-Nielsen IR, Glückstad J. Actuation of microfabricated tools using multiple GPC-based counterpropagating-beam traps. Opt Express 2005; 13: 6899–6904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips DB, Grieve JA, Olof SN, Kocher SJ, Bowman R et al. Surface imaging using holographic optical tweezers. Nanotechnology 2011; 22: 285503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikin L, Carberry DM, Gibson GM, Padgett MJ, Miles MJ. Assembly and force measurement with SPM-like probes in holographic optical tweezers. New J Phys 2009; 11: 023012. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips DB, Gibson GM, Bowman R, Padgett MJ, Hanna S et al. An optically actuated surface scanning probe. Opt Express 2012; 20: 29679–29693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips DB, Padgett MJ, Hanna S, Ho YLD, Carberry DM et al. Shape-induced force fields in optical trapping. Nat Photonics 2014; 8: 400–405. [Google Scholar]

- Palima D, Bañas AR, Vizsnyiczai G, Kelemen L, Ormos P et al. Wave-guided optical waveguides. Opt Express 2012; 20: 2004–2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villangca M, Bañas A, Palima D, Glückstad J. Dynamic diffraction-limited light-coupling of 3D-maneuvered wave-guided optical waveguides. Opt Express 2014; 22: 17880–17889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizsnyiczai G, Lestyán T, Joniova J, Aekbote BL, Strejčková A et al. Optically trapped surface-enhanced Raman probes prepared by silver photo-reduction to 3D microstructures. Langmuir 2015; 31: 10087–10093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aekbote BL, Schubert F, Ormos P, Kelemen L. Gold nanoparticle-mediated fluorescence enhancement by two-photon polymerized 3D microstructures. Opt Mater 2014; 38: 301–309. [Google Scholar]

- Metzger NK, Mazilu M, Kelemen L, Ormos P, Dholakia K. Observation and simulation of an optically driven micromotor. J Opt 2011; 13: 044018. [Google Scholar]

- Palima D, Bañas AR, Vizsnyiczai G, Kelemen L, Aabo T et al. Optical forces through guided light deflections. Opt Express 2013; 21: 581–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale SL, MacDonald MP, Dholakia K, Krauss TF. All-optical control of microfluidic components using form birefringence. Nat Mater 2005; 4: 530–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson SH, Phillips DB, Carberry DM, Hanna S. Bespoke optical springs and passive force clamps from shaped dielectric particles. J Quant Spectrosc Radiat Transf 2013; 126: 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Preece D, Bowman R, Linnenberger A, Gibson G, Serati S et al. Increasing trap stiffness with position clamping in holographic optical tweezers. Opt Express 2009; 17: 22718–22725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bañas A, Kopylov O, Villangca M, Palima D, Glückstad J. GPC light shaper: static and dynamic experimental demonstrations. Opt Express 2014; 22: 23759–23769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villangca M, Bañas A, Palima D, Glückstad J. GPC-enhanced read-out of holograms. Opt Commun 2015; 351: 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MA, Waleed M, Stilgoe AB, Rubinsztein-Dunlop H, Bowen WP. Enhanced optical trapping via structured scattering. Nat Photonics 2015; 9: 669–674. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Jian AQ, Zhang XM, Wang Y, Li ZH et al. Laser-induced thermal bubbles for microfluidic applications. Lab Chip 2011; 11: 1389–1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu GL, Kim J, Lu Y, Lee LP. Optofluidic control using photothermal nanoparticles. Nat Mater 2006; 5: 27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao XY, Wilson BK, Lin LY. Localized surface plasmon assisted microfluidic mixing. Appl Phys Lett 2008; 92: 124108. [Google Scholar]

- Villangca M, Bañas A, Palima D, Glückstad J. Generalized phase contrast-enhanced diffractive coupling to light-driven microtools. Opt Eng 2015; 54: 111308. [Google Scholar]

- Weisstein EW. Teardrop curve. Mathematica Notebook. [updated 22 March 2016; cited 29 March 2016]. Available from http://mathworld.wolfram.com/TeardropCurve.html.

- Weisstein EW. Surface of revolution. Mathematica Notebook. [updated 22 March 2016; cited 29 March 2016]. Available from http://mathworld.wolfram.com/SurfaceofRevolution.html.

- Rodrigo PJ, Perch-Nielsen IR, Alonzo CA, Glückstad J. GPC-based optical micromanipulation in 3D real-time using a single spatial light modulator. Opt Express 2006; 14: 13107–13112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donner JS, Baffou G, McCloskey D, Quidant R. Plasmon-assisted optofluidics. ACS Nano 2011; 5: 5457–5462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LH, Peng XL, Mao ZM, Li W, Yogeesh MN et al. Bubble-pen lithography. Nano Lett 2016; 16: 701–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry DW, Heckenberg NR, Rubinszteindunlop H. Effects associated with bubble formation in optical trapping. J Mod Opt 2000; 47: 1575–1585. [Google Scholar]

- Louchev OA, Juodkazis S, Murazawa N, Wada S, Misawa H. Coupled laser molecular trapping, cluster assembly, and deposition fed by laser-induced Marangoni convection. Opt Express 2008; 16: 5673–5680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayani AA, Khoshmanesh K, Ward SA, Mitchell A, Kalantar-zadeh K. Optofluidics incorporating actively controlled micro- and nano-particles. Biomicrofluidics 2012; 6: 031501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baffou G, Polleux J, Rigneault H, Monneret S. Super-heating and micro-bubble generation around plasmonic nanoparticles under cw illumination. J Phys Chem C 2014; 118: 4890–4898. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng YJ, Liu H, Wang Y, Zhu C, Wang SM et al. Accumulating microparticles and direct-writing micropatterns using a continuous-wave laser-induced vapor bubble. Lab Chip 2011; 11: 3816–3820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murazawa N, Juodkazis S, Misawa H, Wakatsuki H. Laser trapping of deformable objects. Opt Express 2007; 15: 13310–13317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao SL, Desai TA. Micromachined devices: the impact of controlled geometry from cell-targeting to bioavailability. J Control Release 2005; 109: 127–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kress H, Park JG, Mejean CO, Forster JD, Park J et al. Cell stimulation with optically manipulated microsources. Nat Methods 2009; 6: 905–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittard SD, Ovsianikov A, Chichkov BN, Doraiswamy A, Narayan RJ. Two-photon polymerization of microneedles for transdermal drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2010; 7: 513–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villangca M, Casey D, Glückstad J. Optically-controlled platforms for transfection and single-and sub-cellular surgery. Biophys Rev 2015; 7: 379–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.