Abstract

Genetic labeling techniques allow for noninvasive lineage tracing of cells in vivo. Two-photon inducible activators provide spatial resolution for superficial cells, but labeling cells located deep within tissues is precluded by scattering of the far-red illumination required for two-photon photolysis. Three-photon illumination has been shown to overcome the limitations of two-photon microscopy for in vivo imaging of deep structures, but whether it can be used for photoactivation remains to be tested. Here we show, both theoretically and experimentally, that three-photon illumination overcomes scattering problems by combining longer wavelength excitation with high uncaging three-photon cross-section molecules. We prospectively labeled heart muscle cells in zebrafish embryos and found permanent labeling in their progeny in adult animals with negligible tissue damage. This technique allows for a noninvasive genetic manipulation in vivo with spatial, temporal and cell-type specificity, and may have wide applicability in experimental biology.

Keywords: multi-photon microscopy, photoactivation, three-photon microscopy, zebrafish

Introduction

Controlling cell behavior by manipulating the expression of proteins has become a fundamental tool in biology1, 2. Whether triggering their expression using chemical means or using irradiating heat or light3, 4, the predetermination of cells/tissues selected for undergoing a given modification is as important as predicting the moment of the event. Photoactivation of protein expression allows cell or subcellular spatial resolution and high temporal precision5, 6. An attractive system to study the long-term effects of photoactivation in deep tissues in vivo is the Cre–loxP genetic switch system7, 8, which is widely used in biology for controlling protein expression. It controls protein expression by modifying the precise sites in the DNA allowing for the use of specific promoters to target specific cell types and using an external stimulus as a trigger. Because this is in turn a DNA modification, it persists throughout the lifespan of the cell and is also transmitted to its progeny. This technique has been genetically implemented in mice7 and more recently in zebrafish8. A noninvasive, photoinducible Cre–loxP system shown by Sinha et al.9, 10 allows for the activation of the expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP) with temporal and single-cell spatial resolution (Figure 1). This system uses an inactive, caged inducer that penetrates the whole organism but only becomes functional when it is uncaged in the region of interest (Figure 1b and 1c). Uncaging of the inducer was reported to be achieved using ultraviolet illumination without having resolution along the beam path. Using femtosecond pulses at 750 nm, two-photon photolysis allowed for a three-dimensional (3D) spatial resolution successfully labeling single cells in the eye and the somites of 24 h post fertilization (h.p.f.) zebrafish embryos9, 10. However, investigation of the internal organs during development requires accessibility to cells masked by more complex tissues and maintaining long-term viability of the labeled cells. The efficiency of the photoactivation in a selected cell is a function of the number of effective photons (that is, not affected by scattering) that reach the cell (ballistic photons). Far-red photons at 700–750 nm already suffer from significant scattering11, which results in suboptimal photoactivation for powers below the damage threshold.

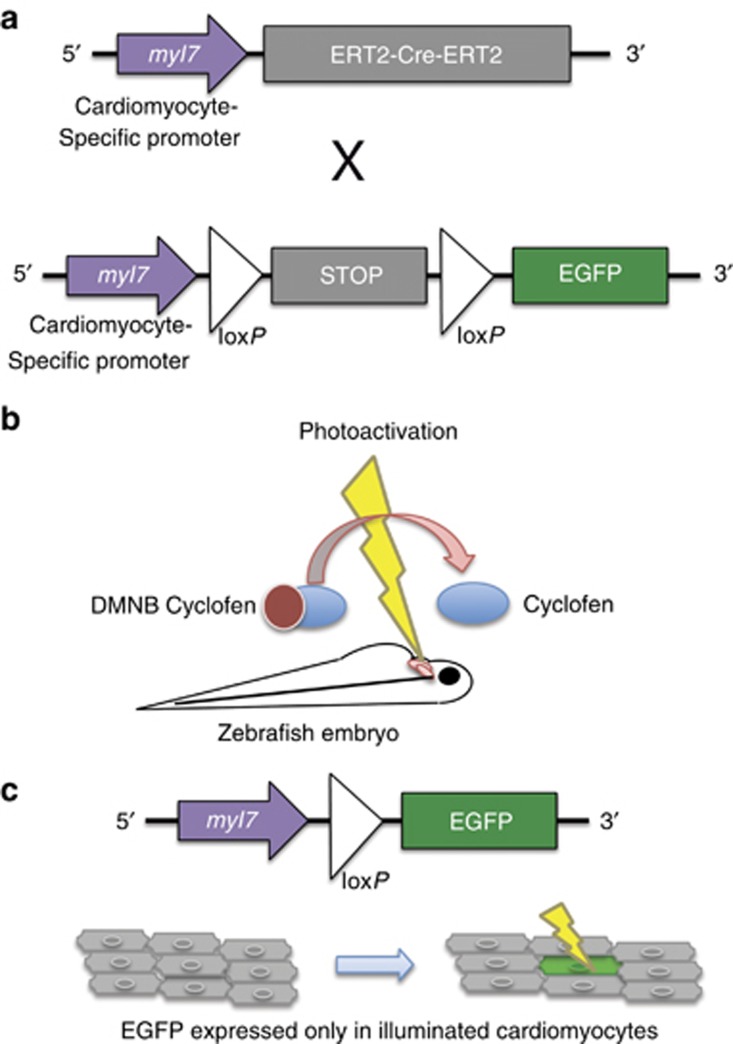

Figure 1.

Photoinducible Cre–lox system. In this system, Cre activity is controlled by fusion to a modified fragment of the estrogen receptor (ERT2), which sequesters Cre outside of the nucleus where it cannot perform recombination. In the presence of an estrogen receptor antagonist, Cre enters the nucleus where it mediates recombination. (a) The transgenic lines used for labeling the zebrafish heart; (b) uncaging of DMNB cyclofen; (c) the final transgene resulting from Cre-mediated recombination in photoactivated cardiomyocytes.

Having been inspired by previous work focused on increasing the imaging depth11, 12, we demonstrate that illuminating at longer wavelengths results in lower scattering when traveling through the tissues, while still inducing nonlinear photoactivation.

Materials and methods

Numerical results

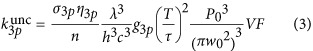

We calculated the n-photon uncaging rate when the laser illuminates a thick sample,  13

13

when n=3 for three-photon and n=2 for two-photon uncaging rates for 4,5-dimethoxy-2-nitrobenzyl (DMNB; with δ2p=σ2p η2p=4 × 10−53 cm4 s per photon and δ3p=σ3p η3p=4 × 10−85 cm6 s2 per photon2, where σnp is the n-photon absorption cross-section and ηnp is the quantum efficiency of uncaging) illuminating with pulses at a period T=50 ns, a pulse of duration τ=180 fs and a focal radius w0=0.25 μm, where h is the Planck constant, c is the velocity of light, VF is the fraction of the excitation volume in the photolysis volume, P0 is the power at the surface of the sample, and the wavelength is λ=730 nm and g2p=0.59 (temporal coherence of the excitation source) for two-photon and λ=1064 nm and g3p=0.41 for three-photon uncaging. The scattering lengths l2p=235 μm and l3p=500 μm were calculated using Mie approximation considering a solution containing 1 μm spheres with ns=1.5, and for water nm=1.33 with a concentration of 5.4 × 10−3 spheres per μm3 with λ=730 nm in the two-photon and λ=1064 nm in the three-photon case.

Zebrafish

Zebrafish were maintained at 28.5 °C and raised according to standard methods14. All experiments were conducted following procedures approved by the Ethics Committees on Experimental Animals of the Barcelona Science Park and Barcelona Biomedical Research Park.

The generation and characterization of the transgenic zebrafish lines used in this study: Tg(-1myl7:ERT2-Cre-ERT2)/Tg(-1myl7:LOXP-STOP-LOXP-EGFP) and Tg(actb2:ERT2-Cre-ERT2)/Tg(Xla.Eef1a1-actb2:LOXP-LOX5171-FRT-F3-EGFP,mCherry), have previously been described15, 16.

Animal procedures

We inhibited pigmentation using 75 μM 1-phenyl 2-thiourea at 22 h.p.f. (28 somite stage) as previously described17.

Caged 4-hydroxy-cyclofen (DMNB cyclofen) was synthesized as previously described9, 10. Zebrafish embryos were incubated in embryo medium containing 2 μM DMNB cyclofen for 12 h before photoactivation. Before illumination, the embryos were thoroughly washed with fresh embryo medium to avoid any possible interference originating from the photorelease of the DMNB cyclofen in the medium.

For a positive control, the embryos were incubated in 2 μM 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen (Sigma-Aldrich, Madrid, Spain).

Before illumination, zebrafish were anesthetized using 4.2 mL of a tricaine solution (4 mg mL−1) per 100 mL of fish tank water14.

Set-up for measuring three-photon cross-section

The set-up used for the measurement of the cross-sections was the following: 280-fs pulses at 1064 nm (~20 nm bandwidth) at a repetition rate of 20 MHz, generated by a fiber laser (Femtopower, Fianium Ltd, Southampton, UK), were sent to an inverted microscope through a telescope to overfill the back aperture of the objective. The light was focused using a 60 × numerical aperture(NA)=1.0 water objective to a femtoliter volume. The emission fluorescence was collected in epifluorescence configuration using photon counting (H9319, Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan).

Three-photon behavior

To test the three-photon behavior for the excitation wavelength of our experimental set-up, we measured the three-photon excited fluorescence versus the excitation power using blue fluospheres (FluoSpheres Carboxylate-Modified Microspheres, 1 μm, blue fluorescent (365/415), Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) that were in suspension (0.02% solids in water, Figure 2a).

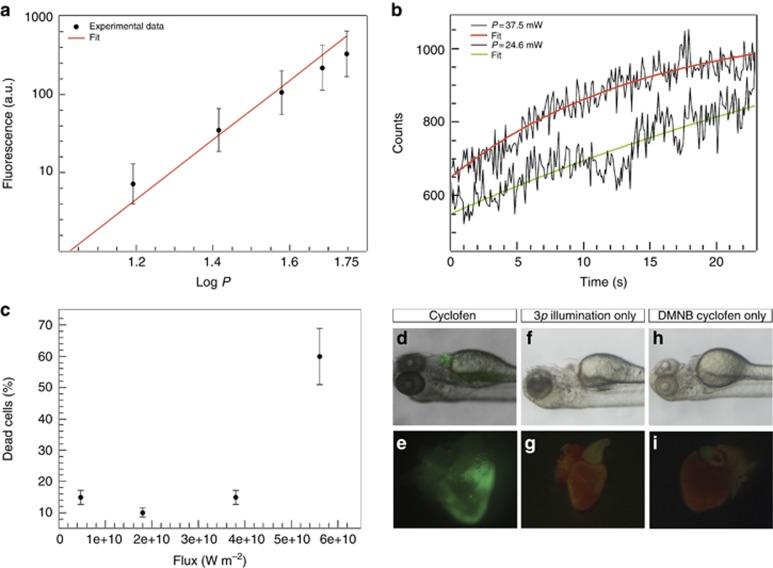

Figure 2.

(a) Three-photon excitation fluorescence from blue fluospheres in suspension (slope of the linear fit, m=2.95) versus the input power at 1064 nm. (b) Three-photon uncaging of DMNB coumarin. Fluorescence increase observed upon illumination of a single cell using 24.6 (lower curve) and 37.5 mW (upper curve). (c) Percentage of dead cells as function of laser flux for illumination at 1064 nm. (d–i) Control experiments showing activated heart when the animal is exposed to cyclofen (d, e), non-activated heart when the animal was illuminated with the three-photon source but not treated with DMNB cyclofen (f, g) or when the animal was treated with DMNB cyclofen but not illuminated with the three-photon source (h, i).

Measurement of the three-photon uncaging cross-section

The three-photon uncaging reaction that takes place within the illuminated volume Vexc resulting from the laser focusing is18

where A is the active substrate, G is the caging group and cA is the caged compound. The corresponding uncaging rate within the photolysis volume is

|

with w0=0.55 μm, T=50 ns, τ=280 fs and λ=1064 nm. Considering that the diffusion coefficient of DMNB is expected to be in the 10−10 m2 s−1 range, the time for diffusing in or out of the focal radius for DMNB is ~1 ms. For pulse durations ≲0.5 ps, the excitation volume is the photolysis volume, and VF=1.

Neglecting diffusion of the reactant and products of the reaction (2) in and out of a single cell inside the fish embryo within the uncaging timescales, each cell can be assumed to be a closed system. The uncaging rate  in the photolysis volume/excitation volume is related to the measured uncaging rate k in a closed volume V=500±50 μm3 (cell) that contains the focal volume Vexc by

in the photolysis volume/excitation volume is related to the measured uncaging rate k in a closed volume V=500±50 μm3 (cell) that contains the focal volume Vexc by

where the reactant and products of the reaction can be considered to be homogeneously distributed within the cell. Then, the concentrations in cA (DMNB substrate) and A (substrate) obey

where the solution is

Measuring the increase of the fluorescence intensity of photo-releasing of fluorescent substrate A in a single cell of the zebrafish embryo that was previously incubated with cA, the rate constant k can be estimated. We chose coumarin as substrate A. We illuminated a superficial single cell in 48 h.p.f. zebrafish embryos with 280-fs pulses at 1064 nm (~20 nm bandwidth) with a repetition rate of 20 MHz using the previously described set-up. For these experiments, the beam was fixed to a predetermined position in the embryo using a 60 × NA=1.0 water objective, and the epifluorescence was detected using photon counting (H9319, Hamamatsu). Figure 2b shows that the intensity exhibits an exponential growth as predicted by expression (6) derived from the kinetic model.

The fluorescence intensity growth can be fitted by

where k=0.07 s−1 for an input power of 37.5 mW and k=0.02 s−1 for an input power of 24.6 mW. Both k values satisfactorily fulfill the expected cubic dependence of k on the input power. From equations (4) and (3), the three-photon uncaging cross-section of DMNB is δ3p=(4±2) × 10−85 cm6 s−1 per photon2.

In vitro damage assay

Primary cultures of zebrafish cardiomyocytes were obtained after dissociating the hearts of the wild-type fish as previously described19 and were illuminated for 100 s with 280-fs pulses at 1064 nm using an upright microscope to study cell damage. After 24 h, we counted the dead cells. The results are shown in Figure 2c. We defined the ‘damage threshold’ as the power where >50% of the cells survived.

Control experiments

Control experiments were performed by exposing the animals to the following: (1) cyclofen, without illumination (Figure 2d and 2e); (2) 280-fs pulses illumination without previous treatment with DMNB cyclofen (Figure 2f and 2g); and, finally, (3) DMNB cyclofen without illumination (Figure 2h and 2i). For further details see Supplementary Table S1.

Three-photon activation set-up

The photoactivation of the DMNB cyclofen was performed using 280-fs pulses at 1064 nm with a repetition rate of 20 MHz generated by a fiber laser (FemtoPower, Fianium Ltd). The pulses were sent by a set of galvo-scanners (Thorlabs, GVSM002/M, Newton, NJ, USA) through a telescope to fulfill the back aperture of the objective. The pulses then were sent to an inverted microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a motorized xy-stage (Märzhäuser, SCAN IM 120 × 80, Wetzlar, Germany) and a motorized objective holder (Märzhäuser, MA42). Typically, a 40x objective with 1.3 NA (Olympus, UPLFLN 40 XO) was used. Targeting the specific tissue was achieved using custom software (Labview, National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA) and a PCI board (National Instruments, NI PCI-6024E) that controlled the galvo-scanners and the motorized stage. A charge-coupled device camera (EverFocus, EQ200E) was used for wide-field imaging of the animal during the experiment. A custom-made software forced the focal spot to follow a 3D sinusoid. Typical patches targeted at the heart were 10 × 5, 20 × 5, 15 × 15, 15 × 20 and 20 × 20 μm2 at 0.1 patch per s using raster scanning. The transient increment of the temperature inside the focal volume, which was generated by the femtosecond pulses, accumulated in time20. To minimize this effect, we combined the heart beating rate with the movement of the beam by adding a z-oscillation to the objective to produce a pulsed photoactivation with a ~25–50 ms pulse width and ~2–3 Hz repetition rate.

Illumination experiments

First, 48–80 h.p.f. zebrafish embryos were placed in a glass-bottom Petri dish (MatTek, Ashland, MA, USA) after 2 min in embryo medium with anesthesia. The zone of photoactivation was previously chosen from a schematic of the ventricle of the zebrafish heart divided into the top, central and bottom portions. The illumination experiment consisted of the three-photon activation using the dedicated software with parameters described above and lasted 2–4 min. After illumination, embryos were transferred to individual tanks for further follow-up. Twenty-four hours later, the embryos were imaged under a fluorescence microscope, were classified according to GFP expression and were transferred to rearing tanks.

Microscopy, in vivo imaging and image processing

General screening of the GFP-positive zebrafish embryos was performed using a fluorescence stereomicroscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany), and for detailed in vivo imaging, a spinning-disk confocal microscope (PerkinElmer UltraViewERS Spinning-Disk microscopy system, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA, mounted on a Zeiss Axiovert 200 M microscope) equipped with a Hamamatsu C9100-50 EMCCD camera was used. Images and videos were processed using Adobe Photoshop (San Jose, CA, USA) and Volocity (PerkinElmer), respectively.

Immunohistochemistry and imaging

Immunohistochemistry was performed on 10-μm cryosections using MF20 (DSHB) and anti-GFP (GFP-1020; Aves Labs, Tigard, OR, USA) antibodies. Images of the heart sections were obtained using a Leica SP5 microscope.

Results and discussion

To address whether three-photon absorption at longer wavelengths is efficient at deeper tissues when excited with powers below the damage threshold, we first calculated the rate of n-uncaging as a function of the quantity of the ballistic photons that reach the target cell. The power of the ballistic photons contributing to the nonlinear absorption follows a Lambert–Beer-like exponential decline

with depth z, characteristic length ls calculated using Mie theory and power P0 at the surface of the sample. The n-photon uncaging rate when the laser illuminates a thick sample is  13

13

where σnp is the n-photon absorption cross-section, ηnp is the quantum efficiency of the uncaging, δnp=σnp ηnp is the action uncaging cross-section, T is the period, τ is the duration of the pulses, λ is the central wavelength, h is the Planck constant, c is the velocity of light, w0 is the focal radius at the xy-plane, gnp is a measure of the n-order of the temporal coherence of the excitation source, VF is the fraction of the excitation volume in the photolysis volume and lnp is the scattering length at the wavelength for the n-photon absorption. The uncaging rates depend on the molecule by δnp and on the illumination by λ, τ, T, w0 and P0. A compromise of the uncaging efficiency and damage constricts the illumination parameters for each tissue.

Several moieties can be used for caging the activating molecule21, 22. We chose DMNB because it was likely to be photoactive at ~1 μm when excited with three photons. The choice of 1 μm excitation is based on the minimization of the scattering effects while using caged molecules that will not be one- and/or two-photon activated in the visible/very near-infrared wavelength allowing their combination with any fluorescent label that is excited within this range. Furthermore, 1 μm is a suitable wavelength for three-photon photoactivation of most caging groups. We measured the three-photon action uncaging cross-section for DMNB (Materials and Methods): δ3p=(4±2) × 10−85 cm6 s−2 per photon2. To our knowledge, there are no measurements of the three-photon action uncaging cross-section and very few three-photon excitation cross-sections13 values in the literature. From the characterization of the one-photon uncaging of DMNB21, we could expect η3p~η1p~0.01 and, therefore, σ3p~10−83 cm6 s−2 per photon2. The latter order of magnitude satisfactorily compares with typical values extracted from three-photon excitation cross-sections of molecules used in functional imaging, such as fura-2 with Ca2+, where  =30 × 10−83 cm6 s−2 per photon2 or indo-1 with Ca2+, were

=30 × 10−83 cm6 s−2 per photon2 or indo-1 with Ca2+, were  =6 × 10−83 cm6 s−2 per photon2 (ref 13) assuming

=6 × 10−83 cm6 s−2 per photon2 (ref 13) assuming  (ref 23). Moreover, the value obtained for the three-photon action uncaging cross-section of DMNB is in a range suitable for efficient uncaging using three-photon excitation.

(ref 23). Moreover, the value obtained for the three-photon action uncaging cross-section of DMNB is in a range suitable for efficient uncaging using three-photon excitation.

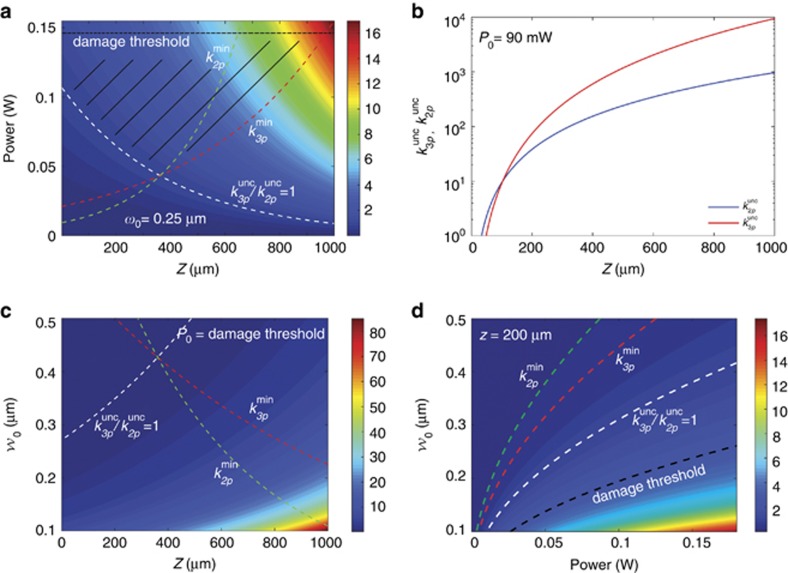

Next, to investigate whether three-photon excitation could improve the uncaging rate for cells within tissues, we compared it theoretically with two-photon uncaging using δ2p=4 × 10−53 cm4 s−1 per photon4 (see Materials and Methods for details on the parameters used). We calculated the ratio between the DMNB uncaging rates for two- and three-photon excitation, and predicted the three-photon excitation for deeply embedded cells to be up to five times more efficient than two-photon illumination (Figure 3a), while being below the damage threshold and above a minimum production rate of the uncaged molecule (Figure 3c). Specifically, our calculations predict greater efficiency of two-photon uncaging for superficial tissues, and the opposite behavior the deeper the cells are within the tissue for powers still below the damage threshold (Figure 3b). Moreover, a higher efficiency of three-photon compared with two-photon uncaging can be achieved by decreasing the focal spot size (Figure 3c); however, this effect is limited by the damage threshold for a specific depth (Figure 3d). In summary, our calculations predict that three-photon uncaging at longer wavelengths could be a solution for photoactivation in tissues located deep inside an animal where two-photon absorption suffers strong scattering that affects the efficiency of activation versus the damage threshold24.

Figure 3.

Numerical results of the ratio between three- and two-photon uncaging rates for DMNB (see Materials and Methods for details on the parameters used). Ratio between three- and two-photon uncaging rates for DMNB: (a) as a function of the input power and the depth inside the embryo (black dashed line is the damage threshold); (b) three-photon (red) and two-photon (black) uncaging rates for DMNB for P0=90 mW as a function of depth; and (c) ratio between the three- and two-photon uncaging rates for DMNB for the same parameters as in a but when P0=damage threshold as function of the focal spot radius w0; and (d) as function of power and the focal spot radius w0 for z=200 μm. In all the plots, the curves represent the damage threshold (black),  (white),

(white),  (red) and

(red) and  (green).

(green).

We confirmed and applied our predictions by investigating the in vivo three-photon activation of cardiomyocytes of 48–80 h.p.f. zebrafish embryos transgenic for a Cre–loxP system that labels cardiomyocytes by expressing GFP (Figure 4). These embryos expressed inducible Cre in their cardiomyocytes and were treated with DMNB cyclofen. Successful uncaging of the DMNB cyclofen would initiate the Cre–loxP recombination process leading to the expression of GFP in the photoactivated cardiomyocytes. We built a custom set-up and designed a protocol with ad hoc photoactivation strategies for optimizing the quantity of molecules uncaged while avoiding tissue damage (see Materials and Methods for details). Targeted cells at >150 μm were successfully labeled and found to express GFP (Figure 4a–4f; Supplementary Video 1). We also accessed different parts of the heart at varying depths (150–200 μm) and labeled distinct areas (Figure 4g; Supplementary Video 2). The overall efficiency of the photoactivation using this system was ~18% (see Supplementary Tables S2 and S3 for details). To test successful activation at even greater depths, we used a transgenic zebrafish line with ubiquitous expression of GFP that switches to mCherry upon activation. This fish line allowed us to target areas not limited to the depth of the heart and to determine more accurately the depth of illumination because we could target non-beating tissue. We could reach depths of z~360 μm in the zebrafish tail, which is promising in applications for more developed animals (Supplementary Figures S1 and S2).

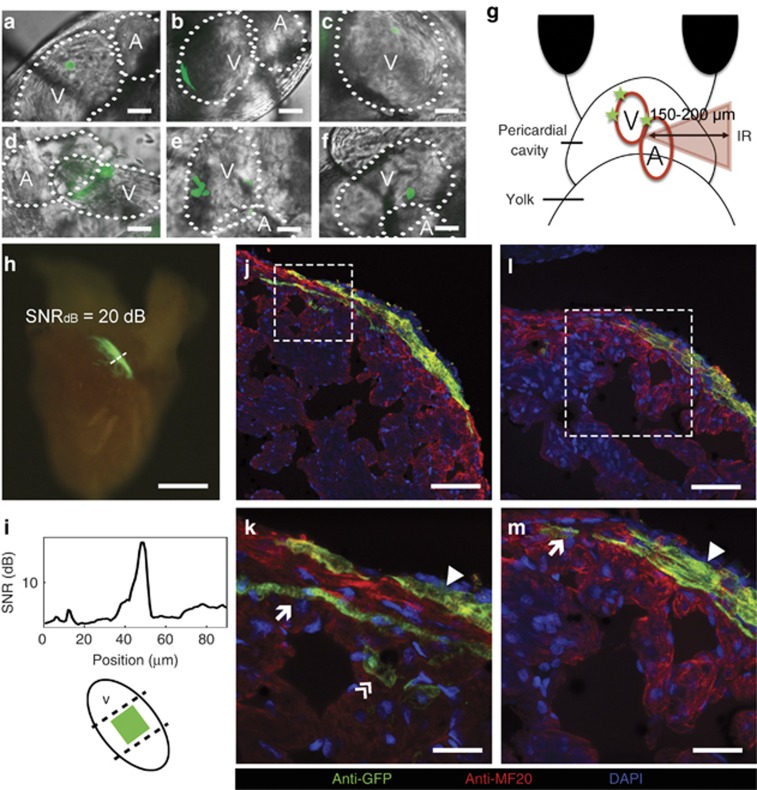

Figure 4.

Long-term in vivo lineage tracing of zebrafish cardiomyocytes. (a–f) Selected areas labeled in the heart of the zebrafish embryo in order of accessibility (scale bar=10 μm, for more details see Materials and Methods): (a, b) approximately100 μm2-labeled areas; (c) a single cell of 100 μm2; (d–f) multiple labeled areas at different locations; and (g) a diagram depicting how areas behind inhomogeneous tissue were labeled at z~150–200 μm. (h) Excised heart of an adult zebrafish. The original ~100 μm2-labeled area was extended to ~0.125 mm2 (scale bar=250 μm); (i) a fluorescence SNR of ~20 dB and the position of the original labeled zone. (j–m) Immunostaining images of the adult zebrafish heart show the participation of the photoactivated cardiomyocytes in the three layers of the heart wall. Scale bars=50 μm (j); 5 μm (k); 20 μm (l); and 10 μm (m). DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; SNR, signal-to-noise ratio.

To investigate the long-term survival of the labeled cells and their progeny, we allowed some of the fish to develop until adulthood at which time their hearts were collected for analysis. Figure 4h shows a heart collected 3 months after three-photon illumination, which originally affected an area of 0.01 mm2 in the central part of the heart ventricle. The final labeled area in the adult heart was ~0.126 mm2 with a signal-to-noise ratio of 20 dB (Figure 4i). Photoactivated cardiomyocytes and their progeny were identified in the adult myocardium and were shown to contribute to all three recently25 identified primordial, cortical and trabecular layers (Figure 4j–4m). Negligible damage occurred during three-photon uncaging in the cardiomyocytes at this embryo stage as the labeled cells were able to survive and divide, and their progeny was found after 3 months in the heart of the adult zebrafish that was indistinguishable from the unlabeled cardiomyocytes.

Conclusions

In summary, we stipulated and confirmed, both theoretically and experimentally, that three-photon illumination of a typical caging group provides a solution to the ubiquitous scattering problem and effectively activates proteins in deep tissues without causing damage along the lifespan of the animal. We have demonstrated, for the first time, that three-photon illumination at ~1 μm of caged cyclofen results in successful uncaging of the compound in deep tissue cells. In combination with a genetic Cre–loxP-labeling system, three-photon activation enables long-term cell lineage tracing of cells embedded in deep tissues or structures. This methodology, which was demonstrated in the heart of the zebrafish, can be extended to other tissues and animal models as well as for activating, with time and space resolution, the expression of different proteins that can provide long-term control of individual or multiple cell behavior in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cristina García for excellent technical assistance with zebrafish husbandry and Angelique di Domenico for critical reading of the manuscript. IT and DZ were partially supported by a pre-doctoral fellowship from MINECO and the I3 program, respectively. Additional support was provided by grants from MINECO (SAF2012-33526, SAF2015-69706-R and BFU2012-38146), ISCIII/FEDER (Red de Terapia Celular—TerCel RD12/0019/0019), AGAUR (2014-SGR-1460), Fundació La Marató de TV3 (201534-30) and ERC (Grant Agreement 242993).

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary Information for this article can be found on the Light: Science & Applications' website(http://www.nature.com/lsa).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Buckingham ME, Meilhac SM. Tracing cells for tracking cell lineage and clonal behavior. Dev Cell 2011; 21: 394–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber T, Köster R. Genetic tools for multicolor imaging in zebrafish larvae. Methods 2013; 62: 279–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugai LJ, Choksi AT, Mesuda CK, Kane RS, Schaffer DV. Optogenetic protein clustering and signaling activation in mammalian cells. Nat Methods 2013; 10: 249–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madisen L, Mao T, Koch H, Zhuo JM, Berenyi A et al. A toolbox of Cre-dependent optogenetic transgenic mice for light-induced activation and silencing. Nat Neurosci 2012; 15: 793–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautier A, Gauron C, Volovitch M, Bensimon D, Jullien L et al. How to control proteins with light in living systems. Nat Chem Biol 2014; 10: 533–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis-Davies GCR. Caged compounds: photorelease technology for control of cellular chemistry and physiology. Nat Methods 2007; 4: 619–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feil R, Brocard J, Mascrez B, LeMeur M, Metzger D et al. Ligand-activated site-specific recombination in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996; 93: 10887–10890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan XF, Wan HY, Chia W, Tong Y, Gong ZY. Demonstration of site-directed recombination in transgenic zebrafish using the Cre/loxP system. Transgenic Res 2005; 14: 217–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha DK, Neveu P, Gagey N, Aujard I, Le Saux T et al. Photoactivation of the CreERT2 recombinase for conditional site-specific recombination with high spatiotemporal resolution. Zebrafish 2010; 7: 199–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha DK, Neveu P, Gagey N, Aujard I, Benbrahim-Bouzidi C et al. Photocontrol of protein activity in cultured cells and zebrafish with one- and two-photon illumination. ChemBioChem 2010; 11: 653–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobat D, Durst ME, Nishimura N, Wong AW, Schaffer CB et al. Deep tissue multiphoton microscopy using longer wavelength excitation. Opt Express 2009; 17: 13354–13364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton NG, Wang K, Kobat D, Clark CG, Wise FW et al. In vivo three-photon microscopy of subcortical structures within an intact mouse brain. Nat Photonics 2013; 7: 205–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakowicz JR. Topics in Fluorescence Spectroscopy: Volume 5. Nonlinear and Two-photon-Induced Fluorescence. New York: Plenum Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Westerfield M. The Zebrafish Book: A Guide for the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) 4th ed. Press, Eugene: Univ. of Oregon Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jopling C, Sleep E, Raya M, Martí M, Raya A et al. Zebrafish heart regeneration occurs by cardiomyocyte dedifferentiation and proliferation. Nature 2010; 464: 606–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boniface EJ, Lu JJ, Victoroff T, Zhu MY, Chen WB. FlEx-based transgenic reporter lines for visualization of Cre and Flp activity in live zebrafish. Genesis 2009; 47: 484–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson J, von Hofsten J, Olsson PE. Generating transparent zebrafish: a refined method to improve detection of gene expression during embryonic development. Mar Biotechnol 2001; 3: 522–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neveu P, Aujard I, Benbrahim C, Le Saux T, Allemand JF et al. A caged retinoic acid for one- and two-photon excitation in zebrafish embryos. Angew Chem Int Ed 2008; 47: 3744–3746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander V, Suñe G, Jopling C, Morera C, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Isolation and in vitro culture of primary cardiomyocytes from adult zebrafish hearts. Nat Protoc 2013; 8: 800–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel A, Noack J, Hüttman G, Paltauf G. Mechanisms of femtosecond laser nanosurgery of cells and tissues. Appl Phys B 2005; 81: 1015–1047. [Google Scholar]

- Aujard I, Benbrahim C, Gouget M, Ruel O, Baudin JB et al. o-nitrobenzyl photolabile protecting groups with red-shifted absorption: syntheses and uncaging cross-sections for one- and two-photon excitation. Chem Eur J 2006; 12: 6865–6879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bort G, Gallavardin T, Ogden D, Dalko PI. From one-photon to two-photon probes: “caged” compounds, actuators, and photoswitches. Angew Chem Int Ed 2013; 52: 4526–4537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem 1985; 260: 3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiskin NI, Chillingworth R, McCray JA, Piston D, Ogden D. The efficiency of two-photon photolysis of a "caged" fluorophore, o-1-(2-nitrophenyl)ethylpyranine, in relation to photodamage of synaptic terminals. Eur Biophys J 2002; 30: 588–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta V, Poss KD. Clonally dominant cardiomyocytes direct heart morphogenesis. Nature 2012; 484: 479–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.