Abstract

Objective

Informed by the family stress and family investment models, this study investigated whether income is indirectly related to adherence and glycemic control through parenting constructs among youth with type 1 diabetes.

Methods

Youth and their families (n=390) from four geographically-disperse pediatric endocrinology clinics in the United States were participants in a multi-site clinical trial from 2006-2009 examining the efficacy of a clinic-integrated behavioral intervention targeting family disease management for youth with type 1 diabetes. Baseline data were collected from youth age 9 to 14 years and their parents. Parents reported family income and completed a semi-structured interview assessing diabetes management adherence. Parents and children reported diabetes-specific parent-child conflict. Children completed measures of collaborative parent involvement and authoritative parenting. Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), a biomarker of glycemic control, was analyzed centrally at a reference laboratory. The relations of income, parenting variables, regimen, adherence, and HbA1c were examined using structural equation modeling.

Results

Lower family income was associated with greater parent-child conflict and a less authoritative parenting style. Authoritative parenting was associated with more collaborative parent involvement and less parent-child conflict, both of which were associated with greater adherence, which was associated with more optimal glycemic control (p<.05 all associations). Indirect effects of family income on adherence and glycemic control through parenting constructs were significant (p<.001).

Conclusions

Findings lend support for the family stress and family investment models, suggesting that lower family income may negatively impact parent-child constructs, with adverse effects on diabetes management.

Keywords: adolescents, socioeconomic status, parenting, type 1 diabetes, family, income

INTRODUCTION

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is an autoimmune disease that generally develops during childhood and adolescence, affecting approximately one in every 500 persons under the age of 20.1 T1D develops when the body’s immune system destroys insulin-producing beta cells of the pancreas. This results in the inability to produce insulin, a hormone necessary for the body to use food consumed for energy. The treatment regimen for T1D is demanding - requiring daily monitoring of blood glucose levels, multiple daily insulin injections or infusion from an insulin pump, monitoring carbohydrate intake, and altering insulin dose to match lifestyle.2 Given the intensity and complexity of the regimen, optimal adherence among youth with type 1 diabetes is a challenge and requires considerable parental and financial support.

Lower family income has been linked to poorer health outcomes in the general population3,4 and also to poorer glycemic control among youth with T1D.5,6 Consequently, individuals with T1D who experience lower family income have higher rates of diabetes complications.7 In a longitudinal study of individuals with child-onset T1D7 lower family income in early adulthood predicted future nerve damage and lower-extremity artery disease, both of which are consequences of poor glycemic control.

Limited research has examined the reasons for the income disparity in disease outcomes among youth with T1D. This disparity may be a product of the direct financial burden of diabetes management, including cost of medical visits, daily testing supplies, and expensive equipment (e.g. glucometers, insulin pump) that may not be fully covered by insurance plans. Consequently, youth from lower income households are less likely to be using an insulin pump regimen,8 which is associated with improved glycemic control.8 However, this explanation for the inverse association of income and glycemic control is not fully consistent with the linear, inverse association of income with glycemic control observed among youth with diabetes residing in Canada, where health care is provided at no cost to patients.6

It is plausible that interpersonal factors in addition to direct cost may be relevant in understanding the association of income with diabetes outcomes among youth. Resource models – a family of models including the family stress model and the family investment model9– attribute poor health outcomes to the adverse effect of low income on a family’s personal, social, and economic resources, resulting in compromised parent-child relationship quality.10 Consistent with these models, lower household income is associated with poorer family functioning across a range of pediatric chronic conditions.11 According to these conceptual frameworks, income may impact parent-child relationship quality (a) due to family stress (the family stress model) and (b) by decreasing the ability of parents to invest time and other resources in their children (the family investment model). The family stress model focuses on the economic dimension of socioeconomic status, whereby low family income and adverse financial experiences create stress in the family. Ultimately, this additional stress and depleted parental resources may result in problems that compromise the parent-child relationship. According to the family investment model, parents with greater resources (in the forms of income, education, and occupation) are more likely to invest these resources in ways that facilitate the well-being of their children.10 These influences may be particularly salient for families of children and adolescents with T1D, who are more likely to report an adverse impact on time and finances than families of youth with other special health care needs.12

An extensive literature documents a consistent, positive association of parent-child relationship qualities, including more parental support and involvement and lower family conflict and parental control with more optimal diabetes outcomes.13 In the general population, parent-child conflict tends to increase during the early adolescent developmental period.14 The management of a chronic illness like T1D places numerous demands on families that may increase conflict,15–17 with well-documented adverse effects on diabetes outcomes.16,18,19 The ability of parents to remain involved in diabetes management in ways that are effective and useful is also an important influence on diabetes outcomes during adolescence.20–22 Parents must balance providing assistance as needed throughout childhood and adolescence while allowing their child to develop a sense of autonomy; as such, optimal parenting during this period is characterized by a shift from a directive role to a more consultative role (e.g., parent’s problem solving with rather than for the youth). This type of collaborative parent involvement is associated with more optimal diabetes management and quality of life.23,24

Parenting practices, such as parent involvement and parent-child conflict, are influenced by overall parenting style.25,26 In the general child development literature, an authoritative parenting style – warm/responsive, demanding (i.e., behavioral control), and accepting of adolescent psychological autonomy (i.e. low psychological control) - has been found to promote positive psychosocial development cross-culturally and across all income levels,26,27 and is consistently associated with a range of positive health outcomes.28,29 Specific to pre-adolescents and adolescents with T1D, an authoritative parenting style is associated with greater adherence to treatment as well as better glycemic control.30–33

Considerable evidence suggests that parenting style varies as a function of socioeconomic status. Studies show that parents in lower income strata tend toward a more authoritarian style of parenting.34–36 Consistent with the family stress and investment models, the stressors that accompany lower economic status have been shown to negatively influence parental resources, leading to more authoritarian parenting.34,36 In contrast, parents in higher income strata tend toward a more authoritative parenting style (for full review, see 37). There is a paucity of research examining the association of family income with parenting style and practices in youth with type 1 diabetes, however. Lower socio-economic status has been associated with higher diabetes-related parent-child conflict,38 and lower parental acceptance,9 but was unassociated with parent monitoring of diabetes care.38,39

Given literature supporting an association between family income and parenting constructs, and literature supporting an association between parenting constructs and diabetes outcomes, it is plausible that the association of income with diabetes outcomes could be attributed in part to the quality of the parent-child relationship. To our knowledge, only one study has examined this question. Drew and colleagues9 found that the relationship of lower family income with glycemic control occurred indirectly through lower parental acceptance. Parents with lower income were observed to be less accepting, and adolescents who perceived their parents as less accepting had worse glycemic control.

The aim of the present study was to expand upon this previous research by examining the direct and indirect pathways between family income and glycemic control through both general parenting style and diabetes-specific parenting behaviors. To our knowledge, no previous study has examined the role of both general parenting style and diabetes-specific parenting behaviors as they relate to the well-documented association between lower family income and glycemic control. Based on the literature on authoritative parenting, we posit an association of general parenting style with two diabetes-specific parenting behaviors – diabetes-related conflict and collaborative parent involvement. We hypothesize that lower family income will be associated with less optimal parenting and will be indirectly associated with adherence and glycemic control through these parenting constructs.

METHODS

Participants

Youth and their parents (N = 390 families) were participants in a multi-site clinical trial examining the efficacy of a clinic-integrated behavioral intervention targeting family disease management for youth with type 1 diabetes conducted from 2006-2009. Participants were recruited from four large, geographically-disperse pediatric endocrinology clinics in the United States. Youth inclusion criteria included being between the ages of 9 and 14.9; diagnosed with T1D for at least 3 months, daily insulin dose ≥0.5 μ/kg/day for those diagnosed ≥1 year or 0.2 μ/kg/day for those diagnosed <1 year and with ≥2 injections or use of insulin pump; most recent hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) >6.0% and <12.0% for those diagnosed ≥1 year and >6.0% at any time post-diagnosis for those diagnosed <1 year; no other major chronic disease (with the exception of well-controlled thyroid, asthma and celiac) or cognitive disability; no psychiatric hospitalization or use of anti-psychotic medications in the past 6 months. Additional parent/family inclusion criteria included home telephone access, fluency in English, the attendance of at least two clinic visits in the past year, and no major psychiatric diagnoses in participating parents.

Procedure

Research staff screened medical records to identify potentially eligible patients with scheduled routine clinic visits and sent families a recruitment letter and brochure with information about the study. Families were then invited to participate during their clinic visit; informed consent was obtained from parents and assent from children. Data from the baseline assessment were used for the present study. Self-report data were collected separately from children and parents in their homes by interviewers not affiliated with the health care team. Of 564 patients invited to participate, 422 consented (75%) and 392 completed baseline assessment (70%); data were excluded from 1 sibling each of 2 sibling pairs. Of these 39 were missing data on family income; resulting in an analytic sample of 351 families. Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of each participating institution.

Measures

Authoritative Parenting Style

Authoritative parenting style was assessed by youth report using the 16-item Authoritative Parenting Index40 and the 8-item Psychological Control Scale.41 The Authoritative Parenting Index has two factors reflecting an authoritative parenting style - responsiveness (e.g. ‘I have a parent who likes me just the way I am.’) and demandingness (e.g. ‘I have a parent who has rules that I must follow.’). In previous research40 the factors have shown good internal consistency (alphas ranging from .71 to .85). Cronbach’s α in the current study were .82 and .72. The Psychological Control Scale (e.g. ‘I have a parent who is less friendly to me if I don’t see things his/her way’) was administered to represent an additional dimension of authoritative parenting. Cronbach’s α’s in the current study was .82. Greater authoritative parenting is indicated by higher responsiveness, higher demandingness, and lower psychological control.

Collaborative Parent Involvement

Collaborative parent involvement in diabetes management was assessed using the Collaborative Parent Involvement Scale.23 This 12-item measure assesses diabetes management parenting behaviors that reflect responsive parenting (e.g., “I have a parent/guardian who helps me plan my diabetes care to fit my schedule”). The measure, which has previously been shown to have good psychometric properties and associations with diabetes management,23,24 was completed by children separately for each parent in their household; 92% of children completed the measure for two parents. Higher scores indicate greater perception of collaborative parent collaborative involvement. Cronbach’s α in the current study was .93.

Diabetes-related Conflict

The level of parent-child conflict over diabetes management issues that typically occurs between the child and the parents was assessed by both child and parent report using the 19-item (e.g. “During the past month, I have argued with my parent(s) about remembering to check blood sugars”) Diabetes Family Conflict Scale, which has previously demonstrated internal consistency and association with glycemic control.42 Higher scores indicate higher levels of conflict. Cronbach’s α was .92 for child-report and .89 for parent-report.

Adherence

Adherence to optimal diabetes management practices was measured with the Diabetes Self- Management Profile,43,44 a structured interview conducted with parents. The measure has demonstrated adequate internal consistency (α =.76), 3-month test-retest reliability (r=.67), inter-interviewer agreement (r=.94), and association with glycemic control.43,44 Cronbach’s α in the current study was .76.

Glycemic Control

Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c; Tosoh A1c 2.2 Plus Glycohemoglobin AnalyzerTM, Tosoh Medics, South San Francisco, CA) was obtained at each visit via blood samples analyzed by a central laboratory. HbA1c is the medical standard for evaluating the quality of diabetes control, and reflects average blood glucose levels over approximately the past 3 months higher values indicate poorer diabetes control.

Income

Parents reported approximate family household income, choosing income ranges in increments from “under $20,000” to “$150,000 or over”. The distribution was <$20,000 (5.9%); $20,000-29,999 (4.4%); $30,000-39,999 (5.6%); $40,000-49,999 (6.4%); $50,000-69,999 (13.8%); $70,000 - 99,999 (21.5%); $100,000-149,999 (18.2%); >$150,000 (14.1%).

Demographic and Diabetes Characteristics

Demographic variables including age, sex, dates of diagnosis, race/ethnicity, and diabetes management regimen were obtained from medical records. Diabetes management regimen was classified as injection versus pump regimen.

Statistical Analysis

Sample characteristics were summarized using means±SD for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables. Chi-square analysis and analysis of variance were used to assess bivariate associations of family income with regimen, adherence, and HbA1c. Polynomial contrasts were used for assessment of linear trends in adherence and HbA1c across family income levels.

Structural equation modeling was conducted in Mplus version 7 (Muthen & Muthen, Los Angeles CA, 2012) to examine the hypothesized associations among family income, parenting variables, regimen, adherence, and glycemic control. The measurement model was first examined to ensure the measured variables adequately represented the hypothesized latent variables. Authoritative parenting was modeled as a latent variable indicated by responsiveness, demandingness, and psychological control. Collaborative parent involvement was modeled as a latent variable indicated by youth report of each parent. Diabetes-specific parent-child conflict was modeled as a latent variable indicated by child and parent report of conflict. In the model specifying relations among income, parenting constructs, regimen, and diabetes outcomes, we hypothesized that family income would be associated directly with authoritative parenting and parent-child conflict, and indirectly with collaborative parent involvement through authoritative parenting because collaborative parent involvement represents behaviors indicative of responsive parenting. We hypothesized that general parenting style (authoritative parenting) would be directly associated with diabetes-specific parenting behaviors (parent-child conflict and collaborative parent involvement), and that diabetes-specific parenting would be directly associated with adherence. As such, the model specified the following effects: a) family income on authoritative parenting, diabetes-specific parent-child conflict, regimen, adherence, and glycemic control, b) authoritative parenting on collaborative parent involvement and diabetes-specific parent- child conflict, c) diabetes-specific parent-child conflict and collaborative parent involvement on adherence, and d) adherence and regimen on HbA1c. Age was included post hoc as a covariate on those parenting variables with which it demonstrated a significant bivariate relationship – parent-reported parent-child conflict, collaborative parent involvement, and responsiveness. Post hoc, we compared fit of this model with that of a model eliminating the paths from income to parenting constructs, to determine whether the full model specifying an indirect effect of income on adherence and glycemic control through the parenting constructs was a better fit to the data.

Model fit was evaluated with respect to three goodness-of-fit statistics: comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis fit index (TLI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). A model with CFI >.90, TLI >.90, and RMSEA < .08 was considered to be adequate fit.45

RESULTS

The demographic and disease characteristics of participants are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of youth participants was 12.4 years; three-quarters were non-Hispanic white. The mean A1c of youth participants was 8.4%, and the mean duration of diagnosis was 4.6 years. Approximately one-third used an insulin pump. Disease management characteristics by family income are shown in Table 2. Median family income group was $70,000-$99,999. Lower family income was associated with less insulin pump use, poorer adherence, and poorer glycemic control. Bivariate associations among income, parenting variables, adherence, and glycemic control are shown in Table 3.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the sample of youth with type 1 diabetes (n=390)

| Mean ± SD or N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age, years; mean ± SD | 12.4 ± 1.7 |

| Gender, N (%) | |

| Female | 198 (50.8) |

| Male | 192 (49.2) |

| Race/ethnicity, N (%) | |

| White | 276 (75.0) |

| Hispanic | 37 (10.1) |

| Black | 34 (9.2) |

| Other | 21 (5.7) |

| Number of adults in the home | |

| One | 51 (13.7%) |

| Two | 285 (76.8%) |

| Three or more | 35 (9.4%) |

| Duration of diabetes, years; mean ± SD | 4.8 ± 3.3 |

| Regimen, N (%) | |

| Pump | 131 (33.8) |

| Injection | 257 (66.2) |

| Hemoglobin A1c (%), mean (SD) | 8.4 ± 1.2 |

Table 2.

Diabetes regimen and management by income level.

| Annual Income | N (%) | % Pump* | Adherence** (Mean ± SD) |

HbA1c** (Mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < $20,000 | 23 (6.6) | 8.7 | 57.4 ± 10.0 | 8.9 ± 1.5 |

| $20,000-$29,999 | 17 (4.8) | 17.5 | 57.7 ± 9.0 | 8.7 ± 1.3 |

| $30,000-$39,999 | 22 (6.3) | 23.8 | 58.4 ± 8.6 | 8.7 ± 1.3 |

| $40,000-$49,999 | 25 (7.1) | 20.0 | 58.6 ± 10.6 | 8.6 ± 1.6 |

| $50,000-$69,999 | 54 (15.4) | 25.9 | 63.1 ± 8.8 | 8.5 ± 0.9 |

| $70,000-$99,999 | 84 (23.9) | 37.3 | 62.4 ± 9.3 | 8.2 ± 1.1 |

| $100,000-$149,999 | 71 (20.2) | 46.5 | 61.3 ± 9.6 | 8.2 ± 1.1 |

| ≥ $150,000 | 55 (15.7) | 41.8 | 63.6 ± 10.1 | 8.1 ± 1.1 |

Note.

chi square p=.005,

p for linear trend <.001

HbA1c Hemoglobin A1c

Table 3.

Bivariate associations of study variables.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 CPI(P1) | − | |||||||||||

| 2 CPI(P2) | .48** | − | ||||||||||

| 3 PCC(C) | −.17** | −.10 | − | |||||||||

| 4 PCC(P) | −.22** | −.12* | .24** | − | ||||||||

| 5 AUTH(R) | .54** | .38** | −.25** | −.26** | − | |||||||

| 6 AUTH(D) | .31** | .19** | −.10 | −.11* | .27** | − | ||||||

| 7 AUTH(P) | −.40** | −.31** | .22** | .23** | −.70** | −.09 | − | |||||

| 8 Regimen | −.04 | .04 | .11* | .09 | −.12* | −.10 | .06 | − | ||||

| 9 Adherence | .33** | .25** | −.14** | −.33** | .30** | .14** | −.22** | −.09 | − | |||

| 10 HbA1c | −.21** | −.17** | .17 | .28** | −.18** | −.12* | .07 | .11* | −.37** | − | ||

| 11 Age | −.22** | −.28** | −.02 | .21** | −.11* | −.01 | .08 | −.03 | −.25** | .18** | − | |

| 12 Income | .13* | .11 | −.21** | −.42** | .21** | .18** | −.24** | −.23** | .18** | −.18** | −.06 | − |

Notes:

Pearson correlation is significant at the 0.01 level;

Pearson correlation is significant at the 0.05 level.

CPI = collaborative parent involvement; for parent with primary (P1), secondary (P2) involvement in diabetes management, PCC = diabetes-specific parent-child conflict reported by child (C), parent (P), AUTH = authoritative parenting; for responsiveness (R), demandingness (D), psychological control (P), Regimen = insulin regimen (dichotomous 1 = injection; 2 = pump

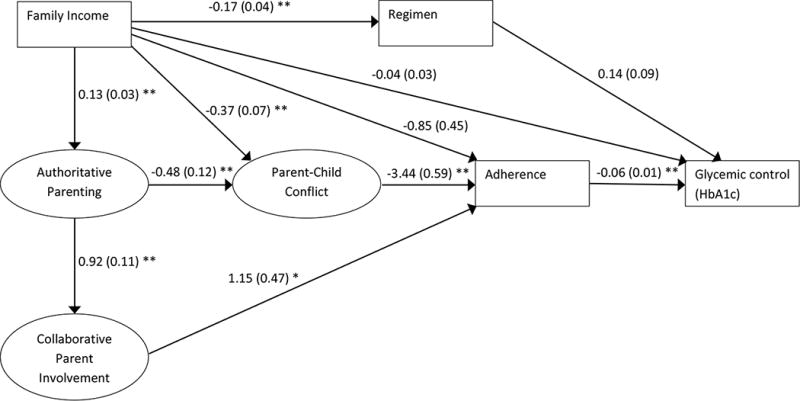

The structural equation model testing the a priori hypothesized associations among family income, parent-child relationship variables, adherence, and HbA1c (Figure 1) demonstrated adequate fit (RMSEA=.05, CFI=.94, TLI=.91). Family income was associated positively with authoritative parenting (p<.001) and negatively with diabetes-specific parent-child conflict (p<.001). Authoritative parenting was directly associated with both diabetes-specific parenting behaviors: collaborative parent involvement (p<.001) and diabetes-specific parent-child conflict (p<.001). Both collaborative parent involvement (p=.02) and diabetes-specific parent-child conflict (p<.001) were directly associated with adherence, and adherence was positively associated with HbA1c (p<.001). Indirect effects of family income on adherence and glycemic control through authoritative parenting, parent-child conflict, and collaborative involvement were significant (p<.001). Also, family income was negatively associated with regimen (p<.001), which was not significantly associated with HbA1c. The direct paths from family income to adherence and HbA1c were not significant. Overall, the model accounted for 24% of the variance in HbA1c.

Figure 1. Results of a structural equation model depicting associations between family income, parent-child relationship quality, and diabetes outcomes.

Note. Coefficients presented as unstandardized β (SE). Authoritative parenting is indicated by responsiveness [β=0.45 (0.02) **], demandingness [β=0.12 (0.02) **], and psychological control [β=-0.36 (0.03) **]. Collaborative parent involvement is indicated by report of parent with primary [β=0.52 (0.07) **] and secondary [β=0.42 (0.05) **] involvement in diabetes management. Parent-child conflict is indicated by child [β=2.50 (0.42) **] and parent [β=2.72 (0.40) **] report. Regimen is dichotomous (1 = injection; 2 = pump). Age is included as a covariate on parenting variables with which it demonstrated a significant bivariate relationship.

* p<.05; ** p<.001

The post hoc structural equation model retaining direct paths between income and adherence/glycemic control, but eliminating the paths from income to parenting constructs demonstrated inadequate fit (RMSEA=.11, CFI=.74, TLI=.63). Difference testing indicated that the fit of the full hypothesized model was significantly greater χ2 (df=2) = 76.07, p<.0001.

DISCUSSION

Despite consistent findings of an association of lower income with poorer diabetes outcomes in youth with T1D, little research has examined the potential reasons for this income disparity in disease management. Consistent with resource models,10 findings from this study suggest that lower family income is indirectly associated with poorer adherence and glycemic control through general and diabetes-specific parenting constructs. The hypothesized pathways specifying that family income is indirectly associated with adherence and glycemic control through general authoritative parenting, collaborative parent involvement in diabetes management, and diabetes-related parent-child conflict were supported by the data. These findings provide support for the family stress and family investment models by demonstrating that the association of lower income with poorer diabetes outcomes may be attributable to the adverse effect of chronic stress among families in lower income strata on parenting constructs.

Findings extend those of Drew and colleagues9 by being the first to our knowledge to examine both general and diabetes-specific parenting constructs in relationship to family income and diabetes management. Consistent with previous research in the general population,34–36 lower family income was associated with a less authoritative parenting style. Additionally, similar to findings in one other sample of youth with type 1 diabetes, lower family income was also associated with greater family conflict.38 In accordance with findings regarding parenting styles and parenting practices across a wide range of behaviors,25,26,28 general parenting style was associated with diabetes-specific parenting practices, which impacted diabetes outcomes. Parents who display warmth and responsiveness while establishing clear standards for behavior are likely to facilitate their child’s adhering optimally to the regimen, while also reducing parent-child conflict and enhancing youth perceptions of collaborative parent involvement. This implies that efforts to promote optimal parent-child communication and collaboration around diabetes management should facilitate the development of an authoritative parenting style, while remaining sensitive to other stressors impacting the parents and family.

The present study suggests that at least some of the adverse impact of lower income on diabetes outcomes may be ameliorated through efforts to help families manage the chronic stressors associated with lower family income and their possible negative impact on the parent-child relationship. Management of diabetes places substantial added stressors on families; these may be particularly draining for families who have fewer resources. As such, attention to the parent-child relationship should be considered an integral part of diabetes education and care. Although differences are likely multifactorial, with components of socioeconomic status, family structure, and family experiences involved, it is evident that the parent-child relationship itself is an important factor that can affect families’ diabetes management.

Previous literature has found that insulin pump therapy is associated with better glycemic control than injections,46 and the lower use of insulin pump therapy among those experiencing lower income represents a plausible explanation for disparities in glycemic control. Our bivariate analysis is consistent with previous findings. However, after controlling for parent-child relationship variables and adherence, this association is no longer significant. As such, disparities in health outcomes by income among youth with T1D are unlikely to be attributable solely to differential access to or use of an insulin pump regimen. Rather, family contextual factors appear critical for understanding income disparities in diabetes outcomes.

Findings should be interpreted in light of study limitations. This was a cross- sectional analysis, which limits causal inference. Longitudinal analyses would be necessary to test mediation models of income and parenting constructs predicting adherence and glycemic control in this population. Nevertheless, the data support the theoretically informed hypothesized paths that income is indirectly related to health outcomes via parenting constructs. Findings provide promising directions for future research. Studies examining these questions in across different race/ethnicity groups would be informative, as some previous research suggests there may be differential associations of parenting style on outcomes by race/ethnicity29,47, while others have shown a beneficial effect of responsiveness across cultures.48 Additionally, the measures and sample size did not allow for an examination of potential differences between parents on parenting constructs in two-parent families, or differences between one-parent and two-parent families. However, previous research has indicated that single-parent status was not associated with adherence and glycemic control after accounting for socioeconomic status.38 Interpretation of household income is limited by the lack of data on total household size or insurance information. Further, the clinical sites where the participants were recruited were all major medical centers in primarily urban and suburban environments, and participation was restricted to an English-speaking sample. Income levels of the sample may not be representative of other urban hospitals. Youth in extremely poor glycemic control and those with recent psychiatric hospitalizations were excluded from the study. Future research examining these associations in additional populations is needed to determine the cross-cultural generalizability of these results.

Achieving good glycemic control during childhood and adolescence is crucial for optimizing health outcomes of persons with T1D, as poor glycemic control during these years is strongly associated with mortality and morbidity in adulthood.19,49 Challenges inherent to the management of T1D may pose a greater strain for families experiencing low income, with subsequent deleterious effects on the parent-child relationship and resulting disease management. As a result, there is a need to develop health care approaches that facilitate optimal parent-child relationships, with special attention to the challenges faced by families experiencing lower income.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support:

This research was supported by the intramural research program of the National Institutes of Health, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, contract numbers N01-HD-4-3364, N01-HD-4-3361, N01-HD-4-3362, N01-HD-4-3363, N01-HD-3-3360.

Footnotes

Author Disclosures:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Services DoHaH, editor. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes fact sheet: national estimates and general information on diabetes and prediabetes in the United States. Atlanta, GA, U.S.: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes–2014. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(Suppl 1):S14–80. doi: 10.2337/dc14-S014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larson K, Halfon N. Family income gradients in the health and health care access of US children. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14(3):332–342. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0477-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashiabi GS, O’Neal KK. Children’s health status: examining the associations among income poverty, material hardship, and parental factors. PLoS One. 2007;2(9):e940. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carter PJ, Cutfield WS, Hofman PL, et al. Ethnicity and social deprivation independently influence metabolic control in children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2008;51(10):1835–1842. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deladoey J, Henderson M, Geoffroy L. Linear association between household income and metabolic control in children with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus despite free access to health care. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(5):E882–885. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Secrest AM, Costacou T, Gutelius B, et al. Associations between socioeconomic status and major complications in type 1 diabetes: the Pittsburgh epidemiology of diabetes complication (EDC) Study. Ann Epidemiol. 2011;21(5):374–381. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paris CA, Imperatore G, Klingensmith G, et al. Predictors of insulin regimens and impact on outcomes in youth with type 1 diabetes: the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth study. J Pediatr. 2009;155(2):183–189 e181. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drew LM, Berg C, King P, et al. Depleted parental psychological resources as mediators of the association of income with adherence and metabolic control. J Fam Psychol. 2011;25(5):751–758. doi: 10.1037/a0025259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conger RD, Donnellan MB. An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:175–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herzer M, Godiwala N, Hommel KA, et al. Family functioning in the context of pediatric chronic conditions. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2010;31(1):26–34. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181c7226b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katz ML, Laffel LM, Perrin JM, et al. Impact of type 1 diabetes mellitus on the family is reduced with the medical home, care coordination, and family-centered care. J Pediatr. 2012;160(5):861–867. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dashiff C, Hardeman T, McLain R. Parent-adolescent communication and diabetes: an integrative review. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(2):140–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foster SL, Robin AL. Parent-adolescent conflict and relationship discord. In: Mash EJ, Barkley RA, editors. Treatment of Childhood Disorders. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1998. pp. 601–646. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kakleas K, Kandyla B, Karayianni C, et al. Psychosocial problems in adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. 2009;35(5):339–350. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller-Johnson S, Emery RE, Marvin RS, et al. Parent-child relationships and the management of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62(3):603–610. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.3.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubin RR, Young-Hyman D, Peyrot M. Parent–child responsibility and conflict in diabetes care. Diabetes Care. 1998;38 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wysocki T, Greco P, Harris MA, et al. Behavior therapy for families of adolescents with diabetes: maintenance of treatment effects. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(3):441–446. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.3.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wysocki T, Hough BS, Ward KM, et al. Diabetes mellitus in the transition to adulthood: adjustment, self-care, and health status. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1992;13(3):194–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berg CA, Butler JM, Osborn P, et al. Role of parental monitoring in understanding the benefits of parental acceptance on adolescent adherence and metabolic control of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(4):678–683. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wiebe DJ, Berg CA, Korbel C, et al. Children’s appraisals of maternal involvement in coping with diabetes: enhancing our understanding of adherence, metabolic control, and quality of life across adolescence. J Pediatr Psychol. 2005;30(2):167–178. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.King PS, Berg CA, Butner J, et al. Longitudinal trajectories of parental involvement in Type 1 diabetes and adolescents’ adherence. Health Psychol. 2014;33(5):424–432. doi: 10.1037/a0032804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nansel TR, Rovner AJ, Haynie D, et al. Development and validation of the collaborative parent involvement scale for youths with type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34(1):30–40. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wysocki T, Nansel TR, Holmbeck GN, et al. Collaborative involvement of primary and secondary caregivers: associations with youths’ diabetes outcomes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34(8):869–881. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113(3):487–496. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steinberg L. We Know Some Things: Parent–Adolescent Relationships in Retrospect and Prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steinberg L, Mounts NS, Lamborn SD, et al. Authoritative parenting and adolescent adjustment across varied ecological niches. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1991;1(1):19–36. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spera C. A Review of the Relationship Among Parenting Practices, Parenting Styles, and Adolescent School Achievement. Educational Psychology Review. 2005;17(2):125–146. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newman K, Harrison L, Dashiff C, et al. Relationships between parenting styles and risk behaviors in adolescent health: An integrative literature review. Rev Lat-Am Enferm. 2008;16(1):142–150. doi: 10.1590/s0104-11692008000100022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goethals ER, Oris L, Soenens B, et al. Parenting and Treatment Adherence in Type 1 Diabetes Throughout Adolescence and Emerging Adulthood. J Pediatr Psychol. 2017;42(9):922–932. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsx053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monaghan M, Horn IB, Alvarez V, et al. Authoritative parenting, parenting stress, and self-care in pre-adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2012;19(3):255–261. doi: 10.1007/s10880-011-9284-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Radcliff Z, Weaver P, Chen R, et al. The Role of Authoritative Parenting in Adolescent Type 1 Diabetes Management. J Pediatr Psychol. 2017 doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsx107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shorer M, David R, Schoenberg-Taz M, et al. Role of parenting style in achieving metabolic control in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(8):1735–1737. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McLoyd VC. The impact of economic hardship on black families and children: psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Dev. 1990;61(2):311–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McLoyd VC, Wilson L. The strain of living poor: Parenting, social support, and child mental health. In: Huston AC, editor. Children in poverty: Child development and public policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1991. pp. 105–135. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pinderhughes EE, Dodge KA, Bates JE, et al. Discipline responses: influences of parents’ socioeconomic status, ethnicity, beliefs about parenting, stress, and cognitive-emotional processes. J Fam Psychol. 2000;14(3):380–400. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.14.3.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoff E, Lauresen B, Tardif T. Socioeconomic status and parenting. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting Volume 2: Biology and ecology of parenting. 2nd. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers; 2002. pp. 231–252. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caccavale LJ, Weaver P, Chen R, et al. Family Density and SES Related to Diabetes Management and Glycemic Control in Adolescents With Type 1 Diabetes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2015;40(5):500–508. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsu113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang L, Ellis DA, Naar-King S, et al. Effects of socio-demographic factors on parental monitoring, and regimen adherence among adolescents with type 1 diabetes: A moderation analysis. J Child Fam Stud. 2016;25(1):176–188. doi: 10.1007/s10826-015-0215-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jackson C, Henriksen L, Foshee VA. The Authoritative Parenting Index: predicting health risk behaviors among children and adolescents. Health Educ Behav. 1998;25(3):319–337. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barber BK. Parental psychological control: revisiting a neglected construct. Child Dev. 1996;67(6):3296–3319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hood KK, Butler DA, Anderson BJ, et al. Updated and revised Diabetes Family Conflict Scale. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(7):1764–1769. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harris MA, Wysocki T, Sadler M, et al. Validation of a structured interview for the assessment of diabetes self-management. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(9):1301–1304. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.9.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Diabetes Research in Children Network Study Group. Diabetes self-management profile for flexible insulin regimens: cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis of psychometric properties in a pediatric sample. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(8):2034–2035. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.8.2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hooper D, Coughlin J, Mullen MR. Structural equation modeling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods. 2008;6(1):53–60. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johns C, Faulkner MS, Quinn L. Characteristics of adolescents with type 1 diabetes who exhibit adverse outcomes. Diabetes Educ. 2008;34(5):874–885. doi: 10.1177/0145721708322857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peterson GW, Steinmetz SK, Wilson SM. Persisting Issues in Cultural and Cross-Cultural Parent-Youth Relations. Marriage Fam Rev. 2005;36(3-4):229–240. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eshel N, Daelmans B, de Mello MC, et al. Responsive parenting: interventions and outcomes. B World Health Organ. 2006;84(12):991–998. doi: 10.2471/blt.06.030163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bryden KS, Peveler RC, Stein A, et al. Clinical and psychological course of diabetes from adolescence to young adulthood: a longitudinal cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(9):1536–1540. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.9.1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]