Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To evaluate the association of institutional protocols for vaginal preparation with antiseptic solution and surgical site infection (SSI) rate in women undergoing cesarean delivery during labor.

METHODS

This is a secondary analysis of a multicenter randomized controlled trial of adjunctive azithromycin prophylaxis for cesarean delivery performed in laboring patients with viable pregnancies. The primary outcome for this analysis was the rate of superficial or deep SSI within 6 weeks postpartum, as per CDC criteria. Maternal secondary outcomes included a composite of endometritis, wound infection, or other infections, postoperative maternal fever, length of hospital stay, and the rates of hospital readmission, unexpected office visits, and emergency room visits.

RESULTS

A total of 523 women delivered in institutions with vaginal antisepsis policies prior to cesarean delivery and 1,490 delivered in institutions without such policies. There was no difference in superficial and deep SSI rates between women with and without vaginal preparation (5.5% vs 4.1%; OR 1.38, 95% CI 0.87 – 2.17), even after adjusting for possible confounders (aOR 0.86, 95% CI 0.43 – 1.73). The lack of significant benefit was noted in all other maternal secondary outcomes.

CONCLUSION

Institutional policies for vaginal preparation prior to cesarean delivery were not associated with lower rates of SSI in women undergoing cesarean delivery during labor.

INTRODUCTION

Cesarean delivery is the most common major surgical procedure worldwide. Over 30% of women that deliver in the United States undergo a cesarean delivery (1).

Women who deliver by cesarean have markedly increased risk of infections including superficial and deep surgical site infection (SSI), endometritis, and other wound complications when compared to vaginal deliveries (2). These outcomes occur more commonly in women who labor before cesarean delivery, and have an important impact on maternal morbidity and health care costs(3). Based on the need for decreasing these complication rates, Tita et al. showed that adding azithromycin to standard antibiotic prophylaxis prior to cesarean delivery during labor significantly decreased the rate of maternal post-cesarean infections, readmissions and unscheduled visits. (4) A new guideline for the prevention of surgical site infection was published by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), highlighting the importance of prophylactic antibiotics.(5)

Vaginal preparation prior to cesarean delivery has been proposed as an intervention to decrease the risk of morbidity due to infection. Most of the studies evaluating vaginal preparations have evaluated endometritis rates but not wound complications.(6, 7) Also, the vast majority of patients enrolled in the trials were patients that underwent scheduled cesarean sections and received cefazolin or ampicillin for prophylaxis. With this study, we aim to evaluate the association of institutional protocol of vaginal preparation with antiseptic solution and SSI rate in a high-risk population with standardized prophylactic measures enrolled in a trial of adjunctive azithromycin prophylaxis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted a secondary analysis of a multicenter randomized controlled trial of adjunctive azithromycin prophylaxis for cesarean delivery (C-SOAP trial – NCT01235546) performed in laboring patients with viable pregnancies of at least 24 weeks.(4) Labor was defined as painful contractions with cervical change or membrane rupture for at least 4 hours. The primary outcome of the C-SOAP trial was a composite of endometritis, wound infection, or other infection occurring within 6 weeks.

The primary outcome for this secondary analysis was the rate of SSI within 6 weeks postpartum, defined as superficial incisional, deep incisional, or organ/space wound infection as per the criteria of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria(8). Maternal secondary outcomes included each component of the primary outcomes (superficial or deep SSI, and endometritis), postoperative maternal fever, length of hospital stay, and the rates of hospital readmission, unexpected office visits, and emergency room visits. Neonatal secondary outcomes included death, suspected or confirmed sepsis, and positive blood and CSF cultures. Trained research coordinators obtained these outcomes and masked investigators centrally adjudicated the maternal infections. Outcomes were compared between women who received antiseptic vaginal preparation prior to their cesarean delivery versus those who did not based on the policy at participating institutions at the time the cesarean delivery was performed.

Maternal, pregnancy, and delivery characteristics were compared between women from institutions with and without vaginal preparation policies using t-tests and chi-square tests of association for continuous and categorical characteristics, respectively. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to examine the association of vaginal preparation while controlling for important potential covariates. Characteristics considered in the multivariable models were identified by p <0.25 in the initial bivariate analyses. A backward selection approach using a retention criterion of p<0.10 was used to generate parsimonious models. The randomized antibiotic group was included in all models. The primary trial was approved by the Institutional Review Board as described in the original paper.(4)

RESULTS

Of the 2013 patients enrolled to the C-SOAP trial (Figure 1), 523 (26%) delivered in institutions with vaginal preparation policies (95% 10% povidone-iodine and the remaining chlorhexidine) prior to cesarean delivery. These women were compared to the remaining 1,490 delivered in institutions without such policies (Table 1). Tobacco and alcohol use during pregnancy, Pfannstiel incision, and GBS colonization were more common in the women who delivered institutions without vaginal antisepsis preparation policies. Patients who delivered in institutions with antisepsis were more likely to have had induction of labor and staples for closure. There were no significant differences in the rates of prophylactic antibiotics or in the rate of randomized assignment to azithromycin or placebo. Regarding the primary outcome, there was no difference in SSI rates between the 2 groups (10.5% vs 8.5%; OR 1.27, 95% CI 0.91 – 1.78). (Table 2) This lack of a significant difference persisted after adjusting for possible confounders (aOR 0.93, 95% CI 0.62 – 1.41). Patients delivered in institutions with antisepsis policies were less likely to stay more than 4 days in the hospital. Otherwise, delivery in a hospital with an antisepsis policy was not significantly associated with other maternal secondary outcomes (Table 3).

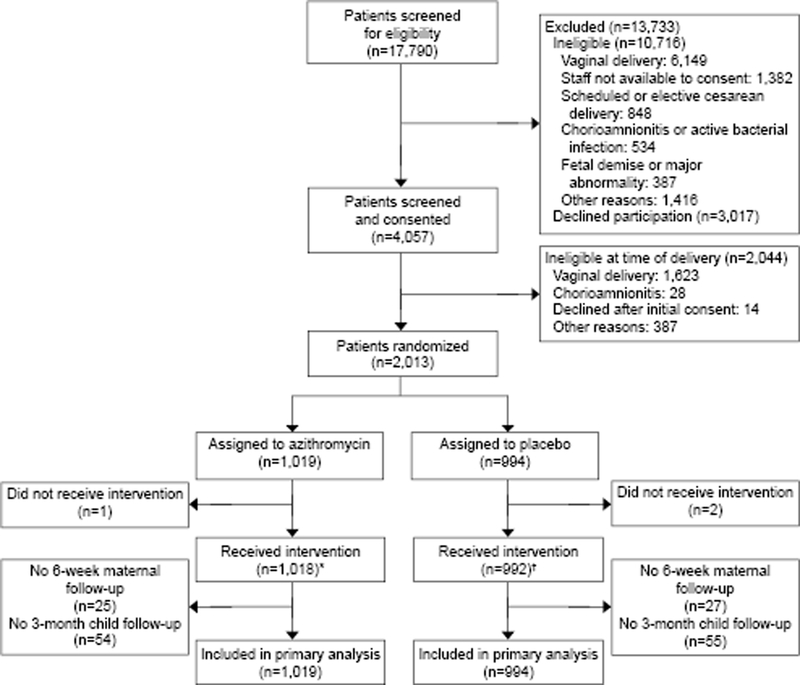

Figure 1.

Enrollment information for the original trial. *Timing not documented (n=9). †Timing not documented (n=11).

Table 1.

Maternal, clinical and delivery characteristics

| Vaginal Prep (n=523) |

No Vaginal Prep (n=1490) |

P- value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MATERNAL CHARACTERISTICS | |||

| Maternal Age, mean (SD) | 27.5 (6.2) | 28.6 (6.3) | 0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 35.4 (7.6) | 35.4 (7.9) | 0.862 |

| Gestational age wks, mean (SD) | 39 (1.6) | 38.9 (2.5) | 0.117 |

| Race/Ethncity | <.001 | ||

| -- Black, non-Hispanic (%) | 73 (14%) | 619 (41.5%) | |

| -- White, non-Hispanic (%) | 125 (23.9%) | 573 (38.5%) | |

| -- Hispanic/Other (%) | 325 (62.1%) | 298 (20%) | |

| 12 years of education or more (%) | 253 (64.5%) | 868 (79.3%) | <.001 |

| Public insurance (%) | 375 (74.6%) | 846 (56.9%) | <.001 |

| Tobacco use during pregnancy (%) | 41 (7.8%) | 178 (11.9%) | 0.009 |

| Alcohol use during pregnancy (%) | 9 (1.7%) | 79 (5.3%) | 0.001 |

| Drug use during pregnancy (%) | 13 (2.5%) | 50 (3.4%) | 0.326 |

| Nulliparous (%) | 240 (45.9%) | 661 (44.4%) | 0.546 |

| Diabetes (Pregestational) (%) | 16 (3.1%) | 67 (4.5%) | 0.155 |

| Chronic hypertension (%) | 18 (3.4%) | 87 (5.8%) | 0.034 |

| GBS status (%) | 100 (19.1%) | 415 (27.9%) | <.001 |

| PREGNANCY COMPLICATIONS | |||

| Diabetes (Gestational) (%) | 47 (9%) | 158 (10.6%) | 0.293 |

| Gestational hypertension/pre- eclampsia/eclampsia/HELLP |

113 (21.6%) | 309 (20.7%) | 0.675 |

| DELIVERY CHARACTERISTICS | |||

| Prophylaxis Antibiotics (%) | 519 (99.2%) | 1488 (99.9%) | 0.043 |

| Induced Labor (%) | 333 (63.7%) | 760 (51%) | <.001 |

| Labor dystocia (%) | 275 (52.7%) | 731 (49.1%) | 0.154 |

| Non-Transverse uterine incision (%) | 21 (4%) | 58 (3.9%) | 0.914 |

| Pfannenstiel incision (%) | 491 (94.1%) | 1443 (96.9%) | 0.004 |

| Staples for skin closure (%) | 405 (77.4%) | 423 (28.4%) | <.001 |

| Randomization group - Azithromycin (%) | 265 (50.7%) | 754 (50.6%) | 0.98 |

| Vaginal preparation - Iodine (%) | 497 (95%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Vaginal preparation prep - Chlorexidine (%) |

26 (5%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Rupture of membanes > 6 hours (%) | 361 (69.4%) | 1000 (67.5%) | 0.413 |

| Surgery length > 49 minutes (%) | 268 (51.5%) | 698 (47%) | 0.077 |

| Estimated blood loss >= 1500 (%) | 27 (5.2%) | 60 (4%) | 0.268 |

| Pre hemoglobin, median (IQR) | 11.9 (11.2-12.8) | 11.9 (11-12.7) | 0.194 |

| PP hemoglobin, median (IQR) | 9.5 (8.7-10.3) | 9.6 (8.6-10.6) | 0.461 |

| Length of stay (days) (IQR) | 3 (2-3) | 3 (3-4) | <.001 |

Table 2.

Outcomes by study group

| Vaginal Prep (n=523) |

No Vaginal Prep (n=1490) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MATERNAL OUTCOMES | |||

| Surgical site infection (%) | 55 (10.5%) | 126 (8.5%) | 0.157 |

| Superficial or Deep SSI (%) | 29 (5.5%) | 61 (4.1%) | 0.167 |

| Endometritis (%) | 28 (5.4%) | 72 (4.8%) | 0.637 |

| PP Fever (%) | 42 (8%) | 90 (6%) | 0.114 |

| Readmission (%) | 18 (3.4%) | 58 (3.9%) | 0.642 |

| Clinic Visit (%) | 24 (4.6%) | 61 (4.1%) | 0.628 |

| ER Visit (%) | 43 (8.2%) | 95 (6.4%) | 0.151 |

| Maternal Hosp Days >= 5 days (%) | 9 (1.7%) | 77 (5.2%) | 0.001 |

| NEONATAL OUTCOMES | |||

| Neonatal/Fetal Death (%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (0.3%) | 0.578 |

| Suspected Sepsis (%) | 28 (5.4%) | 216 (14.5%) | <.001 |

| Confirmed Sepsis (%) | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.1%) | 0.452 |

Table 3.

Logistic regression results*

| Outcome | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)† |

|---|---|---|

| MATERNAL OUTCOMES | ||

| Surgical site infection | 1.27 (0.91-1.78) | 0.93 (0.62-1.41) |

| Superficial or Deep SSI (%) | 1.38 (0.87-2.17) | 0.86 (0.43-1.73) |

| Endometritis | 1.11 (0.71-1.74) | 1.37 (0.76-2.50) |

| PP Fever | 1.36 (0.93-1.99) | 1.45 (0.86-2.43) |

| Readmission | 0.88 (0.51-1.51) | 1 (0.47-2.13) |

| Clinic Visit | 1.13 (0.7-1.83) | - |

| ER Visit | 1.32 (0.9-1.91) | 1.1 (0.7-1.72) |

| Maternal Hospital >= 5 days | 0.32 (0.16-0.65) | 0.18 (0.07-0.47) |

| NEONATAL OUTCOMES | ||

| Neonatal/Fetal Death | - | - |

| Sepsis (Suspected or Proven) | 0.34 (0.23-0.51) | 0.54 (0.32-0.92) |

| Suspected Sepsis | 0.33 (0.22-0.5) | 0.43 (0.26-0.7) |

| Confirmed Sepsis | 2.85 (0.18-45.69) | - |

Table presents the odds of the outcome with vaginal preparation compared to no vaginal preparation.

Models are adjusted for:

Surgical site infection - Randomization Group, BMI, Insurance, Pfannenstiel Incision, Surgery Length, Age

Superficial or deep SSI - Randomization Group, BMI, Race, Staples, Surgery Length

Endometritis – Randomization Group, Insurance, Labor Dystocia, Staples, Age

Postpartum Fever - Randomization Group, Race, GBS, Spontaneous rupture of membranes, Age

Readmission - Randomization Group, BMI, Race, Alcohol, Pfannenstiel Incision

Clinic Visit - Randomization Group, BMI, GBS, Age

Emergency room Visit - Randomization Group, BMI, Insurance, Induced, Labor Dystocia

Neonatal Sepsis (Suspected or Proven) - Randomization Group, Race, Insurance, Pregestational DM, Chronic Hypertension, GBS, Staples, Labor Dystocia

Suspected Sepsis – Randomization Group, Insurance, Pregestational DM, Chronic Hypertension, Labor Dystocia, Staples

Maternal Hospital stay- Randomization Group, Insurance, Alcohol, Chronic hypertension, Pfannensteil incision, Spontaneous rupture of membranes

Neonates born in hospitals with vaginal antisepsis policies had a lower risk of suspected neonatal sepsis (5.4% vs 14.5%; OR 0.33, 95% CI 0.22 – 0.50) but no difference in positive blood or CSF cultures or mortality.

DISCUSSION

In this secondary analysis of the C-SOAP trial we compared the SSI rates of high-risk laboring patients that underwent a cesarean delivery between those that received vaginal preparation prior to the procedure and those that did not, based on institutional policy. We found that the institutional policy of vaginal preparation prior to cesarean delivery during labor was not associated with a reduced incidence of SSI. Results were similar when the secondary maternal outcomes were evaluated. We did not find a significant difference between the groups in the rates of postpartum fever and endometritis. This was contrary to the results of the latest meta-analysis.(7) We also did not find any significant difference in the incidence of maternal outcomes such as readmission, unscheduled clinic visits, or emergency room visits.

Prior studies have evaluated the impact on endometritis rates alone or had different definitions for wound infections or a composite of post cesarean infections. A 2014 meta-analysis concluded that vaginal preparation with povidone-iodine prior to cesarean delivery reduced the risk of postpartum endometritis in patients with ruptured membranes (4.3 % versus 17.9 %; RR 0.24, 95% CI 0.10-0.55) compared to vaginal preparation with saline or no vaginal preparation. (6) This Cochrane review did not show a decrease in wound infection or postoperative fever rates. One pitfall of these data is that neither the type of antibiotic prophylaxis nor the abdominal preparation technique and solutions were described.

A more recent meta-analysis by Caissutti et al. showed that vaginal preparation performed with 10% povidone – iodine with a sponge stick for 30 seconds significantly decreased the rates of endometritis (4.5% versus 8.8%; RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.37– 0.72) and postpartum fever (9.4% versus 14.9%; RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.50– 0.86).(7) The impact of this intervention was limited to patients in labor prior to cesarean delivery and those with ruptured membranes. These results were based on data collected from seven trials, which include a total of 1020 laboring patients. Those trials were performed in several different countries, using different antibiotic prophylaxis, and had different conclusions. In the same meta-analysis, the authors reported no significant difference between the groups neither for wound infection (2.9% vs 3.8%; RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.53 – 1.05) nor for other wound complications, defined as seroma, hematoma, wound separation and cellulitis (5.1% vs 7.1%; RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.43 – 1.17). All the studies that reported wound infection or other wound complications as a secondary outcome had low number of patients enrolled in each arm. An additional pitfall of these studies is the lack of a uniform definition for wound infection and wound complication.(9-16) Also, one of the studies used vaginal metronidazole(10) and another used chlorhexidine.(16)

The main strength of our study is the large number of patients that were included in this randomized controlled trial. This study has almost double the amount of laboring patients that were analyzed in the most current meta-analysis.(7) Based on the number of patients analyzed in this secondary analysis, our study had over 90% power to find a 50% reduction on the rate of surgical site infection. Another strength is the well stablished definition of SSI during the trial, which is based on the current CDC recommendations. All the patients enrolled in the study received the same strict sterile precautions except for the regimen of antibiotic prophylaxis and the use of vaginal preparation. The main weakness of our study is that women were not randomized to vaginal preparation. Another limitation is that the use or non-use of vaginal preparation was based on institutional policy at the time of cesarean delivery and we were not able to evaluate actual adherence to these policies. Also, the technique for vaginal preparation varied from hospital to hospital. It is therefore possible that an alternative explanation for the finding may be that patients at centers with vaginal prep or those that get selected for vaginal prep may differ from those without vaginal prep, perhaps at higher risk of infection to overcome any potential benefits.

In conclusion, institutional policies of vaginal preparation prior to cesarean delivery was not significantly associated with the rate of SSI in women undergoing cesarean delivery during labor.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure

The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Each author has indicated that he or she has met the journal’s requirements for authorship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Betran AP, Ye J, Moller A-B, Zhang J, Gulmezoglu AM, Torloni MR. The Increasing Trend in Caesarean Section Rates: Global, Regional and National Estimates: 1990-2014. PloS one. 2016;11(2):e0148343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gibbs RS. Clinical risk factors for puerperal infection. Obstet Gynecol. 1980;55(5 Suppl):178S-84S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirkland KB, Briggs JP, Trivette SL, Wilkinson WE, Sexton DJ. The impact of surgical-site infections in the 1990s: attributable mortality, excess length of hospitalization, and extra costs. Infection control and hospital epidemiology. 1999;20(11):725-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tita AT, Szychowski JM, Boggess K, Saade G, Longo S, Clark E, et al. Adjunctive Azithromycin Prophylaxis for Cesarean Delivery. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(13):1231-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berríos-Torres SI, Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion CfDCaP, Atlanta, Georgia, Umscheid CA , Center for Evidence-Based Practice UoPHS, Philadelphia, Bratzler DW , College of Public Health TUoOHSC, Oklahoma City , et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guideline for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection, 2017. JAMA Surgery. 2018;152(8):784-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haas DM, Morgan S, Contreras K. Vaginal preparation with antiseptic solution before cesarean section for preventing postoperative infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014(12):CD007892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caissutti C, Saccone G, Zullo F, Quist-Nelson J, Felder L, Ciardulli A, et al. Vaginal Cleansing Before Cesarean Delivery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(3):527-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horan TC, Gaynes RP, Martone WJ, Jarvis WR, Emori TG. CDC definitions of nosocomial surgical site infections, 1992: a modification of CDC definitions of surgical wound infections. Am J Infect Control. 1992;20(5):271-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haas DM, Pazouki F, Smith RR, Fry AM, Podzielinski I, Al-Darei SM, et al. Vaginal cleansing before cesarean delivery to reduce postoperative infectious morbidity: a randomized, controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(3):310.e1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pitt C, Sanchez-Ramos L, Kaunitz AM. Adjunctive intravaginal metronidazole for the prevention of postcesarean endometritis: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98(5 Pt 1):745-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Memon S, Qazi RA, Bibi S, Parveen N. Effect of preoperative vaginal cleansing with an antiseptic solution to reduce post caesarean infectious morbidity. J Pak Med Assoc. 2011;61(12):1179-83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reid VC, Hartmann KE, MCMahon M, Fry EP. Vaginal preparation with povidone iodine and postcesarean infectious morbidity: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(1):147-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Starr RV, Zurawski J, Ismail M. Preoperative vaginal preparation with povidone-iodine and the risk of postcesarean endometritis. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(5 Pt 1): 1024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asghania M, Mirblouk F, Shakiba M, Faraji R. Preoperative vaginal preparation with povidone-iodine on post-caesarean infectious morbidity. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;31(5):400-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yildirim G, Güngördük K, Asicioğlu O, Basaran T, Temizkan O, Davas I, et al. Does vaginal preparation with povidone-iodine prior to caesarean delivery reduce the risk of endometritis? A randomized controlled trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(11):2316-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmed MR, Aref NK, Sayed Ahmed WA, Arain FR. Chlorhexidine vaginal wipes prior to elective cesarean section: does it reduce infectious morbidity? A randomized trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;30(12):1484-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]