Abstract

Objective

To describe nationwide patterns in outpatient opioid dispensing after vaginal delivery.

Methods

Using the Truven Health Analytics MarketScan data base, we performed a large, nationwide retrospective cohort study of commercially-insured beneficiaries had a vaginal delivery between 2003–2015 and who were opioid-naïve for 12 weeks prior to the delivery admission. We assessed the proportion of women dispensed an oral opioid within 1 week of discharge, the associated median oral morphine milligram equivalent (MME) dose dispensed, and the frequency of opioid refills during the 6 weeks following discharge. We evaluated predictors of opioid dispensing using multivariable logistic regression.

Results

Among 1,345,244 women having a vaginal delivery, 28.5% were dispensed an opioid within 1 week of discharge. The most commonly dispensed opioids were hydrocodone (44.7%), oxycodone (34.6%), and codeine (13.1%). The odds of filling an opioid were higher among those using benzodiazepines (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 1.87, 95%CI 1.73 to 2.02) and antidepressants (aOR 1.63, 95%CI 1.59 to 1.66), smokers (aOR 1.44, 95%CI 1.38 to 1.51), and among those having tubal ligation (aOR 3.77, 95%CI 3.67 to 3.87), operative vaginal delivery (aOR 1.52, 95%CI 1.49 to 1.54), and higher order perineal laceration (aOR 2.15, 95%CI 2.11 to 2.18). The median (interquartile range, IQR; 10th–90th percentile) dose of opioids dispensed was 150 (113–225; 80–345) MME, equivalent to 20 tablets (IQR 15–30; 10th–90th percentile 11–46) of oxycodone 5mg. Six weeks after discharge, 8.5% of women filled ≥1 additional opioid prescription.

Conclusion

Opioid dispensing after vaginal delivery is common and often occurs at high doses. Given the frequency of vaginal delivery, this may represent an important source of overprescription of opioids in the United States.

Introduction

Approximately three million vaginal deliveries occur every year in the United States, making it the most common indication for hospitalization (1). Pain following vaginal delivery frequently occurs but is generally short-lived and mild to moderate in severity, and non-opioid analgesics are recommended for pain management (2). Jarlenski and colleagues recently reported that among opioid-naïve Medicaid patients having a vaginal delivery in Pennsylvania, 12% filled a prescription for opioids within 5 days postpartum (3). Of these women, only 28% had painful peripartum events such as tubal ligation, episiotomy, or higher order perineal lacerations. Nationwide data on opioid dispensing after vaginal delivery are lacking. Therefore, we undertook a descriptive study to examine patterns of opioid dispensing after vaginal delivery using a large, nationwide cohort of commercial insurance beneficiaries.

Materials and Methods

The Truven Health Analytics MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental claims database includes patient demographics, insurance enrollment history, inpatient and outpatient medical claims, and outpatient prescription claims for nearly 13 million U.S. reproductive age women per year. The data come from a selection of large employers, health plans, and government and public organizations from all 50 states, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico. The data are entered for billing purposes and coding is considered high-quality as the adjudication of the claim depends on accuracy; additional validation is performed after data entry to ensure accuracy of diagnosis and procedure codes (4). This claims database has been used in other pregnancy-related research (5).

We identified all women hospitalized for vaginal delivery between 2003 and 2015 (all codes used to define study variables are included in Supplementary Appendix 1). Patients in the cohort were required to have continuous medical and prescription drug benefit coverage from twelve weeks prior to the delivery admission (baseline period) until at least one week following discharge. We excluded women with a diagnosis of opioid or other substance use disorder, use of methadone, buprenorphine, or prescription opioids during the baseline period, as well as women who had a peripartum hysterectomy or a code for cesarean delivery.

We calculated the proportion (and 95% confidence interval, CI) of women who had an oral opioid (tablet, capsule, or liquid formulation) dispensed within 7 days of discharge, and the median (interquartile, IQR, and 10th–90th percentile ranges) total oral morphine milligram equivalents (MME) dose dispensed in this prescription (6). We investigated the relationship between calendar year and the proportion dispensed an opioid, using a linear trend test.

We described patient characteristics, selected a priori, of women with and without an opioid prescription including the following: maternal age, geographic region (U.S. Census regions of South, West, Northeast, Midwest, or unknown), delivery year, delivery characteristics that may be associated with additional pain (tubal ligation, operative vaginal delivery, or higher order perineal laceration – third- or fourth-degree), as well as other comorbidities that have been previously related to opioid use (smoking, anxiety disorders, mood disorders, use of anti-depressants, use of benzodiazepines). We performed multivariable logistic regression analysis to evaluate the independent association between each of these variables and having an opioid dispensed. Use of anti-depressants was defined as dispensing of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), tricyclic antidepressant, or other antidepressant in the 12 weeks prior to admission for delivery. Use of benzodiazepines was similarly defined during the same interval. We examined the median MME dose dispensed by each delivery characteristic that may be associated with additional pain.

To examine the frequency of opioid refills, we restricted the cohort to women with a follow-up period at least 6 weeks and calculated the proportion (and 95% CI) of women receiving at least 1 opioid refill.

All analyses were conducted using the Aetion platform (r2.4), which has been validated for a range of studies including observational cohort studies, and SAS (v9.4) (7). The use of this deidentified database was approved by the Partners Human Research Committee.

Results

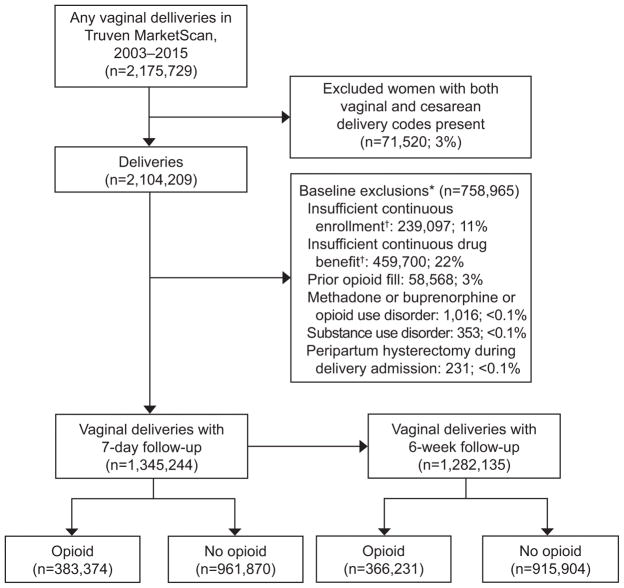

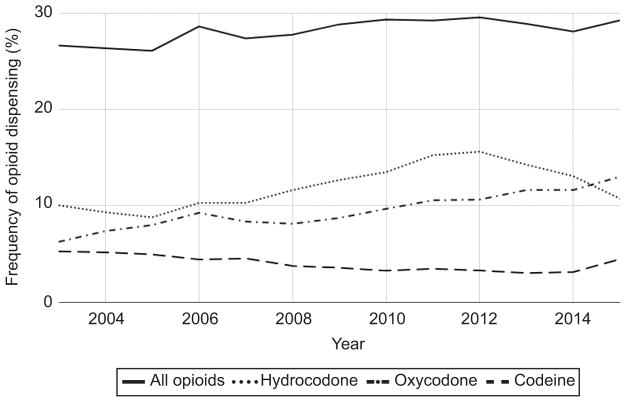

Among the 1,345,244 vaginal deliveries included in the cohort between 2003–2015 (Figure 1), 383,374 (28.5%; 95% CI 28.4 to 28.6%) had an opioid dispensed within 7 days of discharge. During the period of analysis, the frequency of opioid dispensing increased from 26.7% (95% CI 26.2 to 27.1%) in 2003 to 29.3% (95% CI 29.0 to 29.6%) in 2015 (p<0.001 for trend). The most commonly dispensed opioids were hydrocodone [44.7% (95% CI 44.5 to 44.8%)], oxycodone [34.6% (95% CI 34.5 to 34.8%)], and codeine [13.1% (95% CI 13.0% to 13.2%)] (Figure 2). Tubal ligation, operative vaginal delivery, and higher order perineal laceration occurred among 18.0% of women dispensed opioids (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Selection of the cohort. *All exclusions were assessed during the baseline period, unless otherwise specified. The baseline period started 12 weeks (84 days) prior to the delivery admission date and ended 1 day prior to the delivery admission date. †Continuous enrollment and drug benefit coverage required daily medical and prescription coverage during the baseline period, throughout the delivery admission, and until 7 days after delivery discharge date.

Figure 2.

Annual trends in opioids dispensed after vaginal delivery, 2003–2015.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of women with vaginal deliveries, with and without opioid dispensing within 7 days of discharge, 2003–2015 (n=1,345,244)

| Opioids filled (n=383,374) | No opioids filled (n=961,870) | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Age, mean (SD) | 29 (5.1) | 29 (5.3) |

| Age categories, n (%) | ||

| <18 | 1,797 (0.5%) | 5,249 (0.5%) |

| 18 – <26 | 71,111 (18.5%) | 168,809 (17.6%) |

| 26 – <35 | 257,104 (67.1%) | 627,170 (65.2%) |

| 35 – <44 | 52,669 (13.7%) | 158,141 (16.4%) |

| ≥44 | 693 (0.2%) | 2,501 (0.3%) |

| Region, n (%) | ||

| Northeast | 21,865 (5.7%) | 171,294 (17.8%) |

| Midwest | 85,612 (22.3%) | 241,137 (25.1%) |

| South | 196,270 (51.2%) | 331,547 (34.5%) |

| West | 73,073 (19.1%) | 200,487 (20.8%) |

| Unknown | 6,554 (1.7%) | 17,405 (1.8%) |

| Smoking, n (%) | 3,375 (0.9%) | 5,719 (0.6%) |

| Anxiety disorders, n (%) | 3,976 (1.0%) | 9,172 (1.0%) |

| Mood disorders, n (%) | 5,244 (1.4%) | 11,230 (1.2%) |

| Use of benzodiazepines, n (%) | 1,405 (0.4%) | 1,663 (0.2%) |

| Use of SSRI, SNRI, TCA, other antidepressants, n (%) | 15,498 (4.0%) | 24,285 (2.5%) |

| Tubal ligation, n (%) | 14,145 (3.7%) | 9,595 (1.0%) |

| Operative vaginal delivery, n (%) | 36,631 (9.6%) | 58,967 (6.1%) |

| Higher order perineal laceration, n (%) | 27,094 (7.1%) | 32,089 (3.3%) |

| No additional delivery characteristics * | 314,349 (82.0%) | 869,340 (90.4%) |

| Hospital length of stay, mean median (SDIQR) | 3.0 (3.0–3.0) | 3.0 (3.0–3.0) |

| Delivery year, n (%) | ||

| 2003 | 10,442 (2.7%) | 28,719 (3.0%) |

| 2004 | 15,715 (4.1%) | 43,863 (4.6%) |

| 2005 | 16,333 (4.3%) | 46,215 (4.8%) |

| 2006 | 15,080 (3.9%) | 37,570 (3.9%) |

| 2007 | 21,439 (5.6%) | 56,788 (5.9%) |

| 2008 | 34,225 (8.9%) | 88,967 (9.2%) |

| 2009 | 41,722 (10.9%) | 102,834 (10.7%) |

| 2010 | 39,656 (10.3%) | 95,431 (9.9%) |

| 2011 | 43,088 (11.2%) | 104,181 (10.8%) |

| 2012 | 46,185 (12.0%) | 109,852 (11.4%) |

| 2013 | 35,559 (9.3%) | 87,435 (9.1%) |

| 2014 | 39,897 (10.4%) | 101,966 (10.6%) |

| 2015 | 24,033 (6.3%) | 58,049 (6.0%) |

No additional delivery characteristics defined as nonoccurrence of tubal ligation, operative vaginal delivery, or higher order perineal laceration

IQR: interquartile range

SD: Standard deviation

SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

SNRI: serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor

TCA: tricyclic antidepressant

Northeast: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont

Midwest: Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, Wisconsin

South: Alabama, Arkansas Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, Oklahoma, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, District of Columbia, West Virginia

West: Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, Wyoming

In multivariable regression analysis, the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) for filling an opioid was 4.70 (95% CI 4.63 to 4.77) among women from the South, aOR 2.94 (95% CI 2.90 to 2.99) among women from the West, and aOR 2.77 (95% CI 2.72 to 2.81) among women from the Midwest region, as compared to women from the Northeast (Table 2). Women using benzodiazepines or antidepressants also had greater odds of filling an opioid after vaginal delivery [aOR 1.87 (95% CI 1.73 to 2.02) and aOR 1.63 (95% CI 1.59 to 1.66), respectively]. Characteristics potentially associated with increased pain following vaginal delivery – tubal ligation, operative vaginal delivery, and third- or fourth-degree perineal laceration – were also associated with an increased odds of having an opioid dispensed, with the highest odds among women having a tubal ligation (aOR 3.77, 95% CI 3.67 to 3.87) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariable model Predictors predicting Patient characteristics associated with opioid dispensing within 7 days of discharge, 2003–2015 (n=1,345,244)

| CrudeUnadjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age categories, years | ||

| <18 | 0.84 (0.79–0.88) | 0.82 (0.78–0.87) |

| 18 – <26 | 1.03 (1.02–1.04) | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) |

| 26 – <35 | 1.00 (referent)Referent | Referent1.00 (referent) |

| 35 – <44 | 0.81 (0.80–0.82) | 0.83 (0.82–0.84) |

| >=44 | 0.68 (0.62–0.74) | 0.68 (0.62–0.74) |

| Region | ||

| Northeast | Referent1.00 (referent) | Referent1.00 (referent) |

| North CentralMidwest | 2.78 (2.74–2.83) | 2.77 (2.72–2.81) |

| South | 4.64 (4.57–4.71) | 4.70 (4.63–4.77) |

| West | 2.85 (2.81–2.90) | 2.94 (2.90–2.99) |

| Unknown | 2.95 (2.86–3.04) | 2.90 (2.80–2.99) |

| Smoking | 1.49 (1.42–1.55) | 1.44 (1.38–1.51) |

| Anxiety disorders | 1.09 (1.05–1.13) | 1.02 (0.98–1.06) |

| Mood disorders | 1.17 (1.14–1.21) | 1.05 (1.02–1.09) |

| Use of benzodiazepines | 2.12 (1.98–2.28) | 1.87 (1.73–2.02) |

| Use of SSRI, SNRI, TCA, or other antidepressants | 1.63 (1.59–1.66) | 1.63 (1.59–1.66) |

| Tubal ligation | 3.80 (3.70–3.90) | 3.77 (3.67–3.87) |

| Operative vaginal delivery | 1.62 (1.60–1.64) | 1.52 (1.49–1.54) |

| Higher order perineal laceration | 2.20 (2.17–2.24) | 2.15 (2.11–2.18) |

| Delivery year | ||

| 2003 | Referent1.00 (referent) | Referent1.00 (referent) |

| 2004 | 0.99 (0.96–1.01) | 0.97 (0.94–1.00) |

| 2005 | 0.97 (0.95–1.00) | 0.96 (0.93–0.99) |

| 2006 | 1.10 (1.07–1.14) | 1.05 (1.01–1.08) |

| 2007 | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) | 1.01 (0.99–1.04) |

| 2008 | 1.06 (1.03–1.09) | 1.13 (1.10–1.16) |

| 2009 | 1.12 (1.09–1.14) | 1.24 (1.21–1.27) |

| 2010 | 1.14 (1.11–1.17) | 1.31 (1.28–1.34) |

| 2011 | 1.14 (1.11–1.17) | 1.29 (1.25–1.32) |

| 2012 | 1.16 (1.13–1.19) | 1.29 (1.26–1.33) |

| 2013 | 1.12 (1.09–1.15) | 1.25 (1.22–1.28) |

| 2014 | 1.08 (1.05–1.10) | 1.21 (1.18–1.25) |

| 2015 | 1.14 (1.11–1.17) | 1.22 (1.19–1.26) |

CI: confidence interval

SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

SNRI: serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor

TCA: tricyclic antidepressant

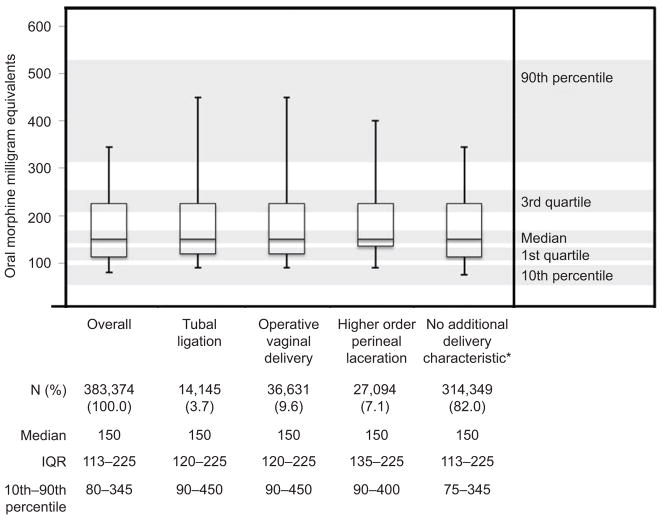

The median total opioid dose dispensed was 150 MME (IQR, 113–225; 10th–90th percentile, 80–345) (Figure 3). This dose is equivalent to prescribing a median 20 (IQR 15–30; 10th–90th percentile 11–46) tablets of oxycodone 5mg. The median MME dose was 150 MME for each delivery characteristic potentially associated with pain.

Figure 3.

Oral morphine milligram equivalents total dose dispensed after vaginal delivery, 2003–2015. *No additional delivery characteristic defined as nonoccurrence of tubal ligation, operative vaginal delivery, or higher order perineal laceration.

Follow-up data to 6 weeks was available for 1,282,135 women (95.3% of initial cohort) and baseline characteristics in this subset were similar to the overall cohort (data not shown). The frequency of opioid dispensing was 28.6% (95% CI 28.5–28.6%), and the median total opioid dose dispensed was 150 MME (IQR, 113–225; 10th–90th percentile, 80–345). Among the 366,691 women with at least 6 weeks follow-up who were dispensed an opioid at the time of discharge after vaginal delivery, 8.5% (95% CI 8.4%–8.6%) had at least 1 refill within 6 weeks.

Discussion

Nearly 30% of women having vaginal deliveries in this nationwide sample of commercially insured beneficiaries were dispensed an opioid following their delivery hospitalization, often in high quantities. Additional procedures at the time of vaginal delivery, which may be associated with increased pain, accounted for less than a fifth of the cases where opioids were dispensed. The median opioid dose dispensed was the same following deliveries with additional procedures or complications as those without these features. The proportion of patients dispensed an opioid was stable over the study interval.

Excessive opioid use unnecessarily exposes women to these addictive medications and generates leftover medications that are available for misuse or diversion (8). Multiple studies suggest that opioid exposure for acute indications can be a trigger for long-term opioid use and misuse (9–11). Further, the most common source of opioids used non-medically are from family or friends, likely from leftover medication from legitimate prescriptions (12). Given these risks, it is imperative for clinicians to consider whether an opioid is necessary for the treatment of pain or whether other, safer analgesics such as acetaminophen or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are adequate. Pain for the great majority of patients following vaginal delivery is in the mild-to-moderate range, suggesting that use of opioids in this clinical setting should be rare (2).

When prescribed, guidelines suggest that opioids should be dispensed at the lowest effective dose for the shortest duration necessary to treat anticipated severe pain (13). We found the median opioid dose prescribed to be 150 MME, equivalent to 20 tablets of oxycodone 5mg; at the 90th percentile the amount prescribed was equivalent to 46 tablets. A recent analysis of 99 primiparous women after vaginal delivery found that for those using opioids, the median time to opioid cessation was less than 1 day (IQR 0–2) after delivery (2). These data suggest that the quantity of opioids prescribed after vaginal delivery greatly exceeds the needs for postpartum pain management for most women.

Notably, codeine accounted for 15.2% of opioids dispensed after vaginal delivery in our data in 2015. This is worrisome, in light of the Food and Drug Administration’s warning against the use of codeine among breastfeeding women, given variable metabolism and risk to the breastfed infant (14). Specifically, infants of mothers who are “ultra-rapid” metabolizers of codeine are at risk for respiratory depression, and rare cases of neonatal deaths have been attributed to exposure to codeine through breast milk.

We also observed strong regional differences in opioid dispensation, with women in the South, West, and Midwest regions having much higher odds of opioid dispensing than those in the Northeast. These regional differences are consistent with other data analyzing contemporary opioid prescribing from pharmacy records, which highlight the South and West as regions of high opioid prescribing (15,16). Although the frequency of opioid dispensings after vaginal delivery in our national cohort of commercially-insured beneficiaries is twice as high as the 12% observed by Jarleenski et al among Medicaid beneficiaries in Pennsylvania, the proportion among commercially-insured beneficiaries in the state of Pennsylvania was similar (14.8%, 95% CI 14.5–15.1%) (3). Similar to our findings, pain-inducing delivery complications and procedures such as bilateral tubal ligation, perineal laceration, and episiotomy were associated with receiving an opioid prescription in Pennsylvania, but they were not associated with the number of days supplied.

Our study is subject to limitations inherent in its design. First, our analysis describes opioid dispensings when a prescription drug benefit was used. This analysis inherently does not capture the number of opioid prescriptions written and not filled, or filled and paid for out of pocket. Moreover, the quantity of opioids consumed (as opposed to dispensed) cannot be determined from these data. The results of our analysis are generalizable only to opioid-naïve women with commercial insurance with a prescription drug benefit. As a significant proportion of U.S. deliveries are covered by Medicaid, nationwide analyses of opioid prescribing and dispensing after vaginal delivery in this population are also needed. Finally, the procedure and diagnostic codes used to define deliveries favored specificity over sensitivity, since a linkage to infants (which is sometimes used in claims-based studies to confirm that the encounter resulted in a birth) was not done for these analyses.

Assuming our results are generalizable to all women delivering vaginally in the United States, our results suggest that around 850,000 women are dispensed an opioid prescription each year. Given the large number of vaginal deliveries each year, curbing unnecessary opioid prescribing in this clinical situation could have a significant public health impact.

Box 1. ICD-9 and CPT Codes for Diagnoses, and List of Medications.

Vaginal delivery

ICD-9 codes V27.x AND 650; or V27.x AND CPT codes 59400, 59409, 59410, 59610, 59612, or 59614

Bilateral tubal ligation

ICD-9 code 66.3x, 66.4, 66.5, 66.6 or CPT codes 58600, 58605, 58611, 58615

Higher order perineal laceration

ICD-9 code 664.2, 664.2x, 664.3, 664.3x

Operative vaginal delivery

ICD-9 code 72.0, 72.1, 72.21, 72.29, 72.31, 72.39, 72.7, 72.71, 72.79, 72.8, 72.9, 669.5, 763.2

Opioid use disorder

ICD-9 code 304.0, 304.00, 304.01, 304.02, 304.03, 304.7, 304.70, 304.71, 304.72, 304.73, 305.5, 305.50, 305.51, 305.52, 305.53

Peripartum hysterectomy

ICD-9 code 68.3, 68.4, 68.6, 68.39, 68.49, 68.69

Cesarean delivery

ICD-9 code 74.0, 74.1, 74.2, 74.4, 74.9, or 74.99; OR CPT codes 59510, 59514, 59515, 59620, or 59622

Substance use disorder

ICD-9 code 304.1, 304.10, 304.11, 304.12, 304.13, 304.2, 304.20, 304.21, 304.22, 304.23, 304.3, 304.30, 304.31, 304.32, 304.33, 304.40, 304.41, 304.42, 304.43, 304.5, 304.50, 304.51, 304.52, 304.53, 304.6, 304.60, 304.61, 304.62, 304.63, 304.8, 304.80, 304.81, 304.82, 304.83, 304.9, 304.90, 304.91, 304.92, 304.93

Smoking

ICD-9 code 305.1, 649.0, 649.00, 649.01, 649.02, 649.03, 649.04, V15.82, 989.84, or CPT codes 99406, 99407, G0436, G0437, 9016, 1034F, 4001F, 4004F, G9276, G9458, S4995, S9453

Anxiety disorders

ICD-9 code 300.00, 300.01, 300.02, 300.09, 300.20, 300.21, 300.22, 300.23, 300.29, 300.3, 308.0, 308.1, 308.2, 308.3, 308.4, 308.9, 309.81

Mood disorders

ICD-9 code 296.00, 296.01, 296.02, 296.03, 296.04, 296.05, 296.06, 296.10, 296.11, 296.12, 296.13, 296.14, 296.15, 296.16, 296.20, 296.21, 296.22, 296.23, 296.24, 296.25, 296.26, 296.30, 296.31, 296.32, 296.33, 296.34, 296.35, 296.36, 296.40, 296.41, 296.42, 296.43, 296.44, 296.45, 296.46, 296.50, 296.51, 296.52, 296.53, 296.54, 296.55, 296.56, 296.60, 296.61, 296.62, 296.63, 296.64, 296.65, 296.66, 296.7, 296.80, 296.81, 296.82, 296.89, 296.90, 296.99, 300.4, 311

Use of SSRI, SNRI, TCA, other antidepressants

sertraline, fluoxetine, paroxetine, citalopram, escitalopram, amitriptyline, perphenazine/amitriptyline, nortriptyline, venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, bupropion, clomipramine, amoxapine, desipramine, doxepin, trimipramine, imipramine, fluvoxamine, mirtazapine, nefazodone, trazodone

Use of benzodiazepines

alprazolam, lorazepam, clobazam, clonazepam, estazolam, quazepam, chlordiazepoxide, clorazepate, midazolam, oxazepam, flurazepam, triazolam, temazepam

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA044293-01A1). KFH was supported by a career development grant K01MH099141 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Footnotes

Each author has indicated that he or she has met the journal’s requirements for authorship.

Presented as a poster at the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine meeting in in Dallas, TX, on February 1, 2018.

Financial Disclosure

Elizabeth M. Garry is an employee of Aetion, Inc., a software and data analytics company, of which she holds stock options. Sonia Hernandez-Diaz is an investigator on grants to the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health from GSK, Lilly, and Pfizer for unrelated work; she receives salary support from the North American AED Pregnancy Registry and is a consultant to UCB, Teva, and Boehringer-Ingelheim; her institution received training grants from Pfizer, Takeda, Bayer, and Asisa. Krista F. Huybrechts is an investigator on grants to Brigham and Women’s Hospital from Lilly, GSK, Pfizer, and Boehringer Ingelheim, unrelated to this study. Brian T. Bateman is an investigator on grants to Brigham and Women’s Hospital from Lilly, GSK, Pfizer, Baxalta, and Pacira, unrelated to this study. He is also a consultant to Aetion, Inc. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Malavika Prabhu, Research Fellow, Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics, Department of Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55 Fruit Street, Founders 460, Boston, MA 02114.

Elizabeth M. Garry, Science, Aetion Inc. New York, NY.

Sonia Hernandez-Diaz, Department of Epidemiology, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Boston, MA.

Sarah C. MacDonald, Department of Epidemiology, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Boston, MA.

Krista F. Huybrechts, Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Boston, MA.

Brian T. Bateman, Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics, Department of Medicine and the Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA.

References

- 1.Martin J, Hamilton B, Osterman M, Driscoll A, Matthews TJ. Births: Final data for 2015. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2017;66(1):1–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Komatsu R, Carvalho B, Flood PD. Recovery after Nulliparous Birth: A Detailed Analysis of Pain Analgesia and Recovery of Function. Anesthesiology. 2017;127(4):684–94. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jarlenski M, Bodnar LM, Kim JY, Donohue J, Krans EE, Bogen DL. Filled Prescriptions for Opioids After Vaginal Delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(3):431–7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansen L. The Truven Health MarketScan Databases for life sciences researchers. White Paper. Truven Health Anal [Internet] 2017 [cited 2018 Apr 13];Available from: https://truvenhealth.com/Portals/0/Assets/2017-MarketScan-Databases-Life-Sciences-Researchers-WP.pdf.

- 5.Tepper NK, Boulet SL, Whiteman MK, Monsour M, Marchbanks PA, Hooper WC, et al. Postpartum venous thromboembolism: incidence and risk factors. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(5):987–96. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Von Korff M, Korff MV, Saunders K, Thomas Ray G, Boudreau D, Campbell C, et al. De facto long-term opioid therapy for noncancer pain. Clin J Pain. 2008;24(6):521–7. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318169d03b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang SV, Verpillat P, Rassen JA, Patrick A, Garry EM, Bartels DB. Transparency and Reproducibility of Observational Cohort Studies Using Large Healthcare Databases. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;99(3):325–32. doi: 10.1002/cpt.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kennedy-Hendricks A, Gielen A, McDonald E, McGinty EE, Shields W, Barry CL. Medication Sharing, Storage, and Disposal Practices for Opioid Medications Among US Adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):1027. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bateman BT, Franklin JM, Bykov K, Avorn J, Shrank WH, Brennan TA, et al. Persistent opioid use following cesarean delivery: patterns and predictors among opioid-naïve women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(3):353.e1–353.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun EC, Darnall BD, Baker LC, Mackey S. Incidence of and Risk Factors for Chronic Opioid Use Among Opioid-Naive Patients in the Postoperative Period. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1286–93. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.3298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brat GA, Agniel D, Beam A, Yorkgitis B, Bicket M, Homer M, et al. Postsurgical prescriptions for opioid naive patients and association with overdose and misuse: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2018;360:j5790. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j5790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones CM, Paulozzi LJ, Mack KA. Sources of prescription opioid pain relievers by frequency of past-year nonmedical use United States, 2008–2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(5):802–3. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.CDC. Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain — United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep [Internet] 2016:65. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1. [cited 2018 Jan 24] Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/rr/rr6501e1.htm. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Use of Codeine and Tramadol Products in Breastfeeding Women - Questions and Answers [Internet] [cited 2017 Jul 31];Available from: https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm118113.htm.

- 15.Guy GP. Vital Signs: Changes in Opioid Prescribing in the United States, 2006–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet] 2017:66. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6626a4. [cited 2018 Apr 3] Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/66/wr/mm6626a4.htm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.McDonald DC, Carlson K, Izrael D. Geographic Variation in Opioid Prescribing in the U. S J Pain Off J Am Pain Soc. 2012;13(10):988–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]