Abstract

Nucleosome assembly proteins (NAPs) are histone chaperones with an important role in chromatin structure and epigenetic regulation of gene expression. We find that high gene expression levels of mouse Nap1l3 are restricted to haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in mice. Importantly, with shRNA or CRISPR-Cas9 mediated loss of function of mouse Nap1l3 and with overexpression of the gene, the number of colony-forming cells and myeloid progenitor cells in vitro are reduced. This manifests as a striking decrease in the number of HSCs, which reduces their reconstituting activities in vivo. Downregulation of human NAP1L3 in umbilical cord blood (UCB) HSCs impairs the maintenance and proliferation of HSCs both in vitro and in vivo. NAP1L3 downregulation in UCB HSCs causes an arrest in the G0 phase of cell cycle progression and induces gene expression signatures that significantly correlate with downregulation of gene sets involved in cell cycle regulation, including E2F and MYC target genes. Moreover, we demonstrate that HOXA3 and HOXA5 genes are markedly upregulated when NAP1L3 is suppressed in UCB HSCs. Taken together, our findings establish an important role for NAP1L3 in HSC homeostasis and haematopoietic differentiation.

Introduction

Haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are rare multipotent blood-forming cells in the bone marrow giving rise to all lineages of mature cells throughout the postnatal life. The balanced self-renewal and differentiation capacity of HSCs is critical for preserving a stable source of HSCs while constantly replenishing all types of mature blood cells1. However, the mechanisms that orchestrate the balance remain poorly understood. It is well established that activation or suppression of lineage specific genes is tightly controlled by transcription factors that act in concert with epigenetic enzymes to determine the fates of HSCs2. These epigenetic enzymes catalyse the removal or addition of epigenetic modifications (e.g. DNA methylation and post-translational modifications of histone and histone variants) and alteration of the chromatin structure, without affecting the DNA coding sequence. Regulation of chromatin structure and inheritance of epigenetic information are instrumental in determining transcriptionally permissive or silenced chromatin states during the development and differentiation2.

The nucleosome assembly proteins (NAP) represent a family of evolutionarily conserved histone chaperones consisting of five members in mammals, having first been identified in mammalian cells3. These histone chaperones are thought to facilitate the import of H2A–H2B histone dimers from the cytoplasm to the nucleus4,5 and to regulate chromatin dynamics by catalysing the assembly or disassembly of nucleosomes4,6–9. More recently these histone chaperones have been implicated in the regulation of covalent histone modifications10–14 and exchange of histone variants in chromatin15–19. The composition and architecture of chromatin is important in all biological processes involving DNA20 and consequently the Nap1 family of proteins is important for a broad range of biological processes; including transcriptional regulation10,14,21–34, cell proliferation35, epigenetic transcriptional regulation10,12,14,26,29,34,36,37, DNA recombination38–40, chromosome segregation18,41–43 and DNA repair42,44,45. Moreover, the Nap1 family of histone chaperones has been associated with a role in the development of various organisms; including Arabidopsis46,47, C. elegans48, and Drosophila49–51, as well as in neural differentiation and function in mouse52.

However, the role of Nap1 proteins in haematopoiesis is largely unknown. Depletion of Nap1 in Xenopus embryos resulted in downregulation of alpha-globin and haematopoietic precursors genes, suggesting that Nap1 proteins have specific functions in haematopoiesis53. In this study, we investigate the in vitro and in vivo role of NAP1L3 in HSC activities and haematopoietic differentiation. Furthermore, we delineate the key transcriptional and signalling pathways underlying the role of NAP1L3 in haematopoiesis.

Results

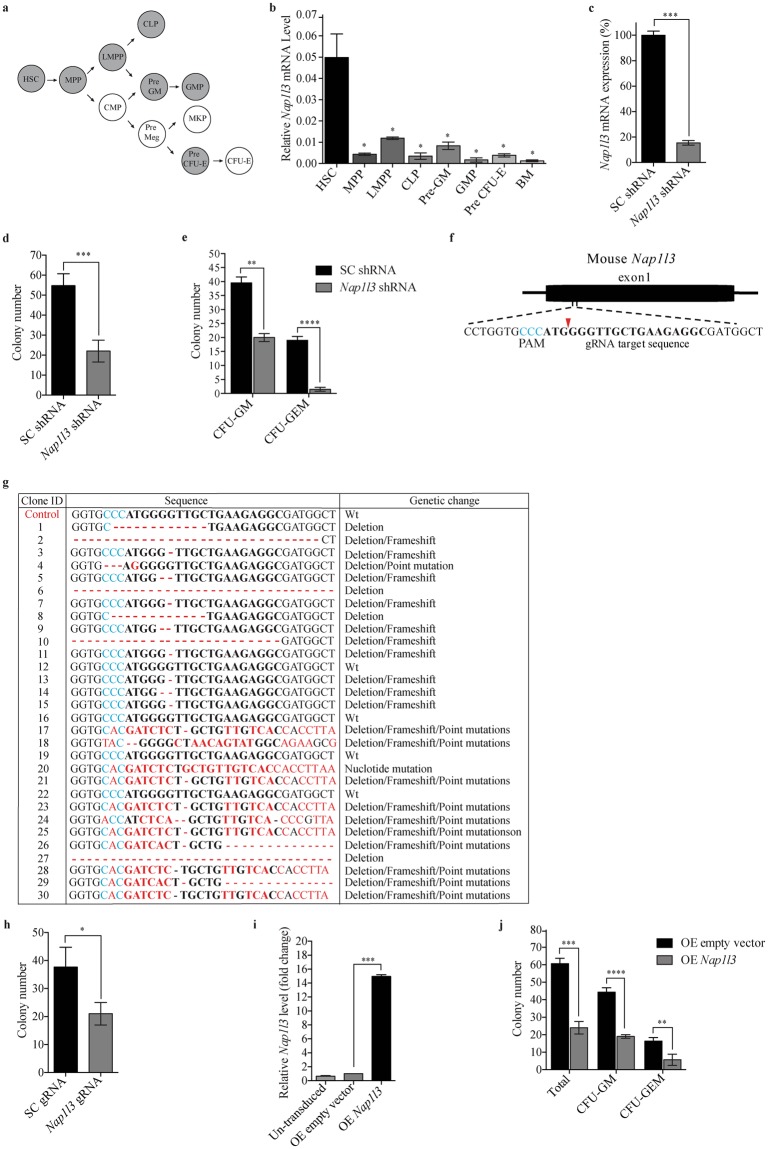

Nap1l3 is highly expressed in mouse haematopoietic stem cells

Nap1l3 has previously been shown to be expressed predominantly in haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), compared to downstream haematopoietic progenies54,55, indicative of a potential functional role in primitive haematopoietic cells. To investigate the gene expression profile of Nap1l3 in different populations of mouse haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), we used a well-established flow cytometry protocol56 to determine Nap1l3 mRNA levels in seven HSPCs cell populations from mouse bone marrow cells (BM); HSC (Lin− Sca1+cKit+ [LSK+]CD105+CD150+), multi-potent progenitors (MPP; LSK+CD105+CD150+), lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitors (LMPP; LSK+Flk2high+), common lymphoid progenitors (CLP; Lin−IL7Ra+flk2+), pre-granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (pre-GM; LSK−CD41−CD150−CD105−), granulocyte-monocyte progenitors (GMP; LSK−CD41−CD150−FcgR+), and erythrocyte progenitors (pre-CFU E; LSK−CD41−CD105+) (Fig. 1a). Consistent with previous expression profiling experiments in mouse55 and human haematopoietic cells54, quantitative real time PCR (qPCR) showed that high Nap1l3 mRNA expression was restricted to the HSC fraction, compared to the downstream haematopoietic progenitor cells and unfractionated BM cells (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1.

Nap1l3 is predominantly expressed in murine haematopoietic stem cells and loss of function or overexpression impairs colony-forming capacity. (a) Illustration of 11 different primary murine HSPCs populations. The seven cell populations highlighted in grey were analysed in (b). (b,c) qPCR analysis showing Nap1l3 mRNA levels (normalised to Hprt) of indicated cell populations (b) and of sorted LSK HSCs transduced with an shRNA against Nap1l3 (Nap1l3 shRNA), or a control vector (SC shRNA) (c). The data is represented as the mean ± s.e.m, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.005 (unpaired t-test), n = 3. (d,e) The total colony numbers (d), and colony numbers of CFU-GM and CFU-GEM (e), formed from LSK HSCs transduced with Nap1l3 shRNA (Nap1l3 shRNA) or a control vector (SC shRNA) after ten days of clonal growth in methylcellulose. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005, ****p < 0.001 (unpaired t-test), n = 3. (f) Homology of the gRNA designed to target the murine Nap1l3 gene (the protospacer adjacent motif [PAM] = blue letters, the Cas9 nuclease cutting site = red arrow and the gRNA target sequence = bold letters). (g) Sequencing results of 30 clones of the Nap1l3 gene targeted by CRISPR-Cas9 in LSK HSCs (gRNA targeting sequence = bold letters, the PAM sequence = blue letters, and nucleotide changes relative to the WT Nap1l3 = red dashes or letters), and the genetic changes are indicated in the last column (h) Colony numbers resulting from sorted LSK HSCs expressing Cas9 transduced with an inducible gRNA vector targeting Nap1l3 (Nap1l3 gRNA), or a control vector (SC gRNA). The colonies were analysed after 10 days of clonal growth in methylcellulose supplemented with doxycycline. The data is represented as the mean ± s.e.m., *p < 0.05 (unpaired t-test), n = 3. (i) qPCR analysis showing Nap1l3 mRNA levels (normalised to Hprt) of enriched cKit+ HSCPs overexpressing Nap1l3 (OE Nap1l3), an empty vector (OE empty vector) or un-transduced cells. The data is represented as the mean ± s.e.m., ***p < 0.005 (unpaired t-test), n = 3. (j) The total number of colonies, GM and GEM colonies formed of sorted cKit+ HSCPs overexpressing Nap1l3 (OE Nap1l3) or an empty vector (OE empty), after ten days of clonal growth in methylcellulose. The data is represented as the mean ± s.e.m., **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005, ****p < 0.001 (unpaired t-test).

Nap1l3 downregulation in primitive murine bone marrow cells reduces colony formation capacity

Given that high levels of Nap1l3 gene expression were restricted to HSCs (Fig. 1b), we investigated the functional importance of Nap1l3 in HSPCs differentiation and proliferation of primitive murine BM cells by shRNA-mediated loss of function studies. In this approach, the shRNA knockdown vectors were introduced by lentiviral transfer (i.e. transduction) to Lin−Sca+cKit+ (LSK) HSPCs sorted from lineage depleted BM cells. shRNA-mediated downregulation of Nap1l3 resulted in a significant reduction (~85%) in mRNA levels compared to the negative scramble control vector expressing scrambled shRNA (Fig. 1c). Subsequently, downregulation of Nap1l3 caused a marked reduction (approximately three-fold) in the total number of colony-forming units (CFUs) in the HSPCs compared to the control cells transduced with a negative control vector (Fig. 1d). Remarkably, downregulation of Nap1l3 in LSK HSPCs led to a significant reduction of mixed myelo-erythroid CFUs (CFU-GEM) (ten-fold reduction) and a significant reduction in the number of granulocyte/macrophage CFUs (CFU-GM) (50% reduction), compared to cells transduced with a negative control vector (Fig. 1e). Consistent with this, downregulation of Nap1l3 in LSK HSPCs with an independent shRNA, caused a similar reduction of total number of CFU-GEM and CFU-GM colony-forming units (Supplementary Fig. 1). This suggests that Nap1l3 suppression preferentially affect the proliferation and survival of the more primitive HSPCs, which is in line with its restricted expression in HSCs.

CRISPR-Cas9 mediated disruption of Nap1l3 confirms a specific role in HSCs and differentiation

shRNA-mediated RNA interference (RNAi) can be associated with off-target effects if the shRNA itself possesses partial complementary to an undesired target elsewhere in the genome. Although the shRNAs targeting Nap1l3 used in our present studies had no significant homology to any other open reading frame, we took advantage of highly specific CRISPR-Cas9 technology to ensure that the previously observed role of this nucleosome assembly enzyme in haematopoietic cells was specific. To test this, LSK HSPC BM cells from transgenic mice overexpressing Cas9 nuclease were isolated and transduced with inducible guide RNA (gRNA) vectors targeting the Nap1l3 gene (Fig. 1f). Sanger sequencing of CRISPR-Cas9 targeted genomic DNA from the LSK HSPCs demonstrated that 25 out of in total 30 sequenced clones displayed genetic alterations in the Nap1l3 gene. 17% of the cells carried significant deletions or continuous stretches of changed nucleotides (>10 base pair), and 60% of the cells displayed frameshift mutations, which likely will disrupt the gene function of Nap1l3 (Fig. 1g). Consistent with our results from shRNA-mediated knockdown, CRISPR-Cas9 targeted disruption of the Nap1l3 gene caused a significant reduction in number of total CFUs (>50% reduction) compared to the control cells after ten days of clonal growth (Fig. 1h), thus confirming a specific function of Nap1l3 in colony forming capacity and proliferation of HSPCs.

Overexpression of Nap1l3 in primitive murine bone marrow cells reduces colony formation capacity

To further investigate the functional importance of Nap1l3 in haematopoiesis, we used a lentiviral vector for stable exogenous expression of Nap1l3 in cKit+ HSPCs. Constitutive overexpression of Nap1l3 resulted in an approximately 14-fold increase in mRNA levels compared to endogenous levels in un-transduced cKit+ HSPCs and cKit+ cells transduced with an empty control vector (Fig. 1i). Surprisingly, as in our shRNA and CRISPR-Cas9 experiments (Fig. 1d,e and h), overexpression of Nap1l3 in cKit+ HSPCs resulted in a significant reduction in the total number of CFUs, CFU-GM and CFU-GEM colonies, compared to control cells transduced with an empty vector after ten days of clonal growth and differentiation in methylcellulose (Fig. 1j).

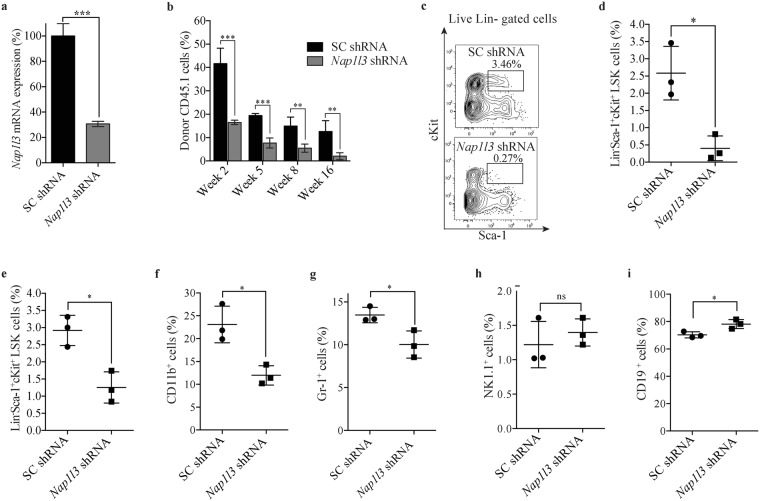

Nap1l3 downregulation reduces the engraftment and frequency of primitive mouse cells in vivo

To understand the importance of Nap1l3 in haematopoiesis in vivo, we used a congenic murine bone marrow transplantation model. Accordingly, we transplanted sorted CD45.1+ cKit+ donor HSPCs transduced with either an shRNA vectors efficiently downregulating Nap1l3 mRNA levels or a negative control vector expressing scrambled shRNA into lethally-radiated isogenic CD45.2+ wild-type (wt) C57BL/6 recipient mice (Fig. 2a). Longitudinal flow cytometric analysis of peripheral blood from the transplanted mice showed significant engraftment of donor cells transduced with negative control vectors at two, five, eight and 16 weeks post transplantation (15–45% of engraftment) (Fig. 2b). Conversely, transplanted cKit+ donor HSPCs transduced with an shRNA vector against Nap1l3 resulted in a significant reduction (2–18% of engraftment) of engrafted cells compared to the control mice at two, five, eight and 16 weeks post transplantation (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2.

Nap1l3 downregulation impairs maintenance of murine HSCs and blood lineage regeneration. (a) qPCR analysis of Nap1l3 mRNA levels (normalised to Hprt) of sorted LSK HSCs transduced with an shRNA against Nap1l3 (Nap1l3 shRNA), or a control vector (SC shRNA). The data is represented as the mean ± s.e.m, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.005 (unpaired t-test), n = 3. (b) Flow cytometric analysis of the percentage of CD45.1+ donor cells resulting from transduction of sorted cKit+ HSPCs transduced with Nap1l3 shRNA (Nap1l3 shRNA) or a control vector (SC shRNA) in peripheral blood of lethally radiated recipient mice, at two, five, eight and 16 weeks post transplantation. The data is represented as the mean ± s.e.m., **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005 (unpaired t-test), n = 3. (c) Representative flow cytometric chart showing percentage of LSK HSC BM CD45+ donor cells, transduced with a negative control vector (SC shRNA, upper panel), or an shRNA vector targeting Nap1l3 (Nap1l3 shRNA, lower panel) in recipient mice five weeks post transplantation. The percentage of LSK HSCs is highlighted in each flow cytometry chart. (d,e) Percentage of donor derived LSK HSCs transduced with shRNAs against Nap1l3 or a control vector. The cells were isolated from the bone marrow of recipient mice 5 weeks (c) and 16 weeks (d) after transplantation and analysed by flow cytometry. **p < 0.01 (unpaired t-test), n = 3. (f–i) Percentage of mature donor cells; CD11b+ myeloid (f), Gr-1+ granulocytes (g), NK1.1+ NK cells (h) and CD19+ B cells (i) after transduction of sorted cKit+ HSPCs transduced with shRNAs against Nap1l3 (Nap1l3 shRNA) or a control vector (SC shRNA). Bone marrow cells were isolated and analysed by flow cytometry 16 weeks post transplantation. ns = non-significant, *p < 0.05, (unpaired t-test).

Wanting to focus on studying the importance of Nap1l3 in HSCs short-term maintenance in vivo, we used the same procedure as in Fig. 2b, and transplanted LSK HSCs with and without shRNA-mediated Nap1l3 knockdown into lethally radiated recipient mice. Flow cytometric analysis of bone marrow cells from the recipient mice five weeks after transplantation revealed that downregulation of Nap1l3 caused a distinct reduction of donor LSK cells (median percent of 0.4%), compared to transplanted LSK HSCs transduced with the negative control vector expressing scrambled shRNA (median percent of 2.6%) (Fig. 2c,d). To investigate the long-term effects of Nap1l3 downregulation on LSK HSCs, we repeated our experiments and performed flow cytometric analysis at eight and 16 weeks post-translation. Consistent with the short terms results in Fig. 2d, downregulation of Nap1l3 caused a significant reduction in donor LSK HSCs both at eight weeks (median percent of 0.2% in knockdown cells vs 1.8% in the control cells) and at 16 weeks (median percent of 1.2% in knockdown cells vs 3.0% in control cells), (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 2a). Altogether, this data suggests that Nap1l3 plays an important role both in HSC short-term and long-term maintenance in vivo.

Nap1l3 downregulation in mouse HSPCs affects their capacity in blood lineage regeneration after transplantation

To investigate if the downregulation of Nap1l3 affects the reconstitution of haematopoietic cells in vivo, we transplanted cKit+ donor HSPCs transduced with either Nap1l3 shRNA or a negative control vector into lethally irradiated recipient mice, as in Fig. 2b–e. Flow cytometric analysis of mature blood cells showed a significant decrease in the frequency of myeloid cells (CD11b+), granulocytes (Gr-1+) (Fig. 2f,g), whereas the percentage of NK cells (NK1.1+) was not significantly changed (Fig. 2h), 16 weeks after transplantation. In contrast, the percentage of B cells (CD19+) was significantly increased in Nap1l3 knockdown cells compared to the control cells (Fig. 2i). Apart from the results of the NK cells, comparable results were obtained after eight weeks after transplantation, as the results at 16 weeks after transplantation (Supplementary Fig. 2b–e). These data suggest that Nap1l3 is required for HSC maintenance and haematopoietic restoration.

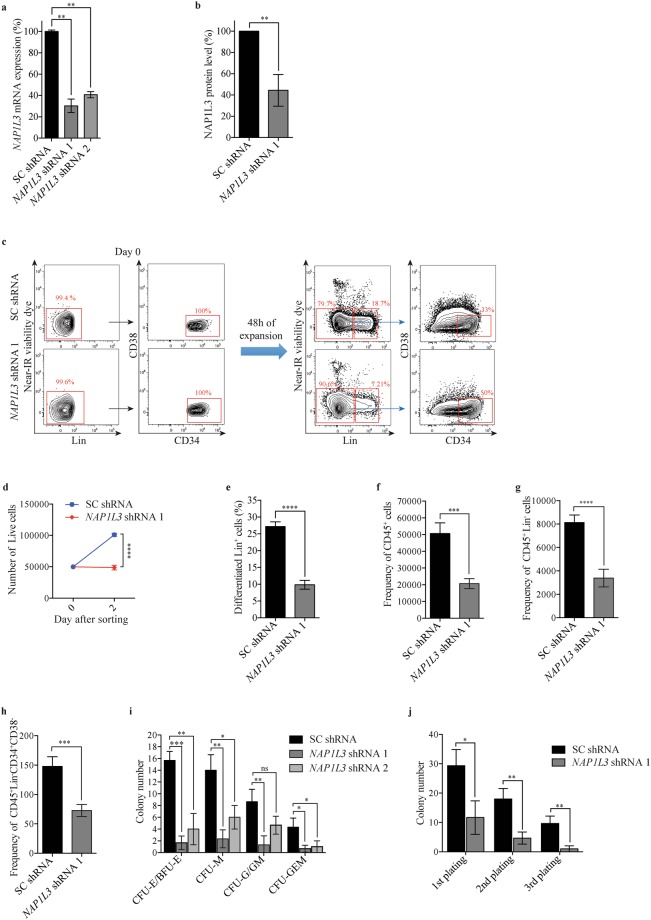

NAP1L3 is important for maintenance of human HSCs and proliferation in vitro

We next investigated if NAP1L3 was also important for human HSC maintenance. Thus, to investigate early cellular responses of primitive UCBs to downregulation of NAP1L3, we transduced sorted human (Lin−CD34+CD38−) UCB enriched HSCs (hereinafter referred to as UCB HSCs) with either two independent shRNAs against NAP1L3 or a negative control vector. qPCR analysis of mRNA levels (Fig. 3a) and flow cytometry analysis of intracellular protein levels (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 3), demonstrated an efficient downregulation of NAP1L3 gene expression levels. Flow cytometric analysis revealed that UCB HSCs transduced with a control vector underwent a cell doubling after 48 hours of culture in suspension, whilst NAP1L3 downregulated-HSCs displayed impaired cell proliferation (Fig. 3c,d), suggesting that NAP1L3 is required for the in vitro proliferation of UCB HSCs. In addition, we also observed a reduction of the frequency of cells expressing mature cell lineage markers (Lin+) derived from the NAP1L3 shRNA targeted UCBs as compared to the control cells (Fig. 3e).

Figure 3.

NAP1L3 is important for proliferation and survival of human haematopoietic stem cells in vitro. (a,b) qPCR analysis showing NAP1L3 mRNA levels (normalised to UBC) (a), or flow cytometric quantification of intracellular NAP1L3 protein levels (b), in of sorted (Lin−CD34+CD38−) UCB HSCs transduced with two independent shRNA vectors targeting NAP1L3 (NAP1L3 shRNA1 and 2) or a control vector (SC shRNA). The data is represented as the mean ± s.e.m., **p < 0.01 (unpaired t-test), n = 3. (c) Representative flow cytometry charts showing expression levels of lineage markers (Lin), CD34 and CD38 resulting from sorted (Lin−CD34+CD38−) UCB HSCs transduced with NAP1L3 shRNA (NAP1L3 shRNA), or a control vector (SC shRNA), immediately after sorting (Day 0, left panels) and 48 hours post sorting (right panels). The percentages of live Lin−, Lin+, and Lin−CD34+CD38− cells are highlighted in red. (d) Absolute numbers of sorted (Lin−CD34+CD38−) UCB HSCs transduced with NAP1L3 shRNA (NAP1L3 shRNA), or a control vector (SC shRNA), immediately after transduction and sorting of 50,000 cells (day 0) and 48 hours after antibiotic selection (Day 2). The numbers of (Lin−CD34+CD38−) UCB HSCs was determined by flow cytometry according to (c). The data is represented as the mean ± s.e.m., ****p < 0.001 (unpaired t-test), n = 3. (e) Percentage of Lin+ UCBs transduced with NAP1L3 shRNA (NAP1L3 shRNA), or a negative control vector expressing scrambled shRNA (SC shRNA), determined by flow cytometry analysis according to (b), 48 hours post transduction and sorting of the cells. The data is represented as the mean ± s.e.m., ****p < 0.001 (unpaired t-test), n = 3. (f–h) Frequency of CD45+ (e), Lin−CD45+ (f) and Lin−CD34+CD38− (g), after maintaining CD34+ enriched UCB HSPCs transduced with an shRNA against NAP1L3 (NAP1L3 shRNA) or a control vector (SC shRNA), for three weeks on murine LS/LS and M2-10B4 bone marrow stromal cells. The data is represented as the mean ± s.e.m., ***p < 0.005, ****p < 0.001 (unpaired t-test), n = 3. (i) Average number of CFU-E/BFU-E, CFU-M, CFU-G/GM, CFU-GEM, resulting from CD34+ enriched UCBs transduced with two individual shRNA vectors targeting NAP1L3 (NAP1L3 shRNA) or a control vector (SC shRNA), after 14 days of clonal growth in methylcellulose. The data is represented as the mean ± s.e.m., ns = non-significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005 (unpaired t-test), n = 3. (j) Serial replating assay of colony formation by control or NAP1L3 transduced HSPC UCBs. CFUs were scored every 14 days and the cells were replated in triplicate. The data is represented as the mean ± s.e.m., *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 (unpaired t-test), n = 3.

To investigate the long-term effects of NAP1L3 suppression in UCB HSCs in vitro, we transduced CD34+ enriched HSPC UCBs with vectors targeting NAP1L3 or control vectors and co-cultured these cells with murine SL/SL and M2-10B4 bone marrow stromal cell lines, allowing for the maintenance and functional detection of primitive human haematopoietic cells57. Consistent with the results in murine haematopoietic cells (Fig. 1d,e,h and j) and in the short-term experiment using human UCBs (Fig. 3b–d), flow cytometric analysis revealed a significant reduction in CD45+ (Fig. 3f), Lin−CD45+ (Fig. 3g), and UCB HSCs (Fig. 3h), after maintaining the cells for three weeks on the stromal cells.

Wanting to further investigate the role of NAP1L3 in proliferation and differentiation of haematopoietic cells in human cells, we transduced CD34+ enriched UCB HSPCs with one of two shRNAs against human NAP1L3 or a negative control vector. After 14 days of clonal growth in methylcellulose, a significant reduction in the numbers of; burst-forming unit erythroid cells (CFU-E/BFU-E, 90%), macrophages (CFU-M, 50%), granulocytes/macrophages (CFU-G/GM, 50%), and mixed myelo-erythroid cells (CFU-GEM, 75%) were observed for both shRNAs compared to the control cells transduced with a negative control vector, with the exception of NAP1L3 shRNA 2 in CFU-G/GM cells, which did not yield a significant reduction (Fig. 3i). Strikingly, serial replating of HSPCs expressing shRNAs against NAP1L3 resulted in a significant reduction in the total number of colonies in the first plating, which was further reinforced in the second and third replating of the cells, compared to control cells (Fig. 3j).

These data indicate that the importance of mouse Nap1l3 in maintenance of HSCs is conserved in human UCBs.

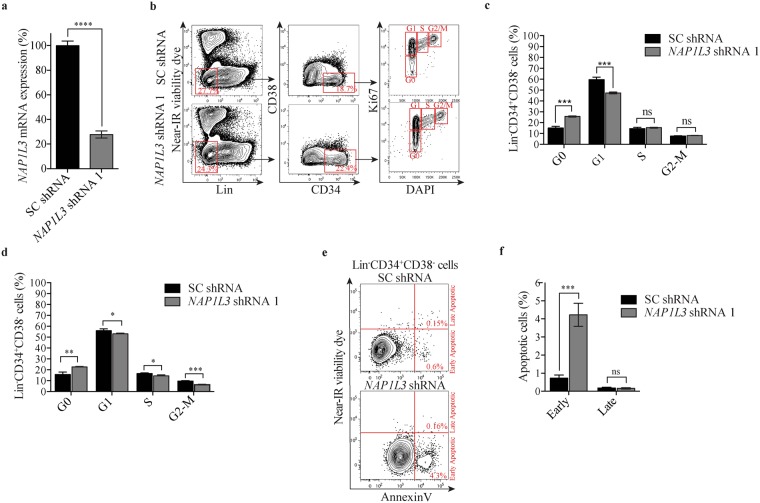

NAP1L3 downregulation induces an arrest in the G0 phase of the cell cycle and apoptosis in UCBs

To investigate the cellular mechanisms by which NAP1L3 is important for haematopoiesis, we sorted UCB HSCs and transduced the cells with shRNAs against NAP1L3 or negative control vectors (Fig. 4a). NAP1L3 knockdown resulted in a marked accumulation of UCB HSCs in the G0 phase of the cell cycle (25%) compared to control cells (15%), at four days after transduction. In addition, we observed a similar reduction of NAP1L3 knockdown cells in G1 (48%) compared to that of the control cells (60%), whereas no significant change was observed for the S or G2/M phases (Fig. 4b,c). After six days of propagation, a similar proportion of the UCB HSCs resided in the G0 phase of the cell cycle as compared to four days after transduction, but this time we also observed a significant reduction of cells in the S and G2/M phases (Fig. 4d).

Figure 4.

NAP1L3 downregulation causes an arrest in the G0 phase of the cell cycle and induces apoptosis. (a) qPCR analysis showing NAP1L3 mRNA levels (normalised to UBC) in sorted (Lin−CD34+CD38−) UCB HSCs transduced with shRNA vectors targeting NAP1L3 (NAP1L3 shRNA) or control vectors (SC shRNA). The data is represented as the mean ± s.e.m., **p < 0.01 (unpaired t-test), n = 3. (b) Representative flow cytometry charts of intracellular Ki67 and DNA content (DAPI) staining in (Lin−CD34+CD38−) UCB HSCs transduced with NAP1L3 shRNA (NAP1L3 shRNA), or a control vector (SC shRNA), 5 days post transduction. The percentages of Lin− and CD34+CD38− UCBs and the different phases of the cell cycle are highlighted in red. (c,d) The proportion of (Lin−CD34+CD38−) UCB HSCs transduced with NAP1L3 shRNA (NAP1L3 shRNA) or a control vector (SC shRNA), in the different phases of the cell cycle four days (c) and six days (d), post transduction. The data is presented as mean ± s.e.m., ns = non significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005 (unpaired t-test), n = 3. (e) Representative flow cytometry charts of (Lin− CD34+CD38−) HSC UCBs transduced with NAP1L3 shRNA (NAP1L3 shRNA), or a control vector (SC shRNA), stained with near-IR viability control and Annexin V, to detect apoptotic cells, five days post transduction. The percentage of cells in each population is highlighted in red. (f) The proportion of early or late apoptotic (Lin−CD34+CD38−) UCB HSCs transduced with NAP1L3 shRNA or a control vector, two days after sorting live cells. The data is presented as mean ± s.e.m., ns = non significant, ***p < 0.005, (unpaired t-test), n = 3.

UCB HSCs transduced with a negative control vector displayed low levels of both early apoptotic cells (Annexin V+NIR−) (0.6%) and late apoptotic cells (Annexin V+NIR+) (0.2%) after maintaining the sorted live cells for two days in culture (Fig. 4e,f). In contrast, UCB HSCs transduced with shRNAs against NAP1L3 resulted in a marked increase in the percentage of early apoptotic cells (4.5%), but no significant increase in late apoptotic cells (0.9%) (Fig. 4e,f).

Together, this data suggests that downregulation of NAP1L3 causes a growth arrest of UCB HSCs in the G0 phase of cell cycle progression and triggers apoptosis, which might explain the observed reduction in HSC numbers and activities.

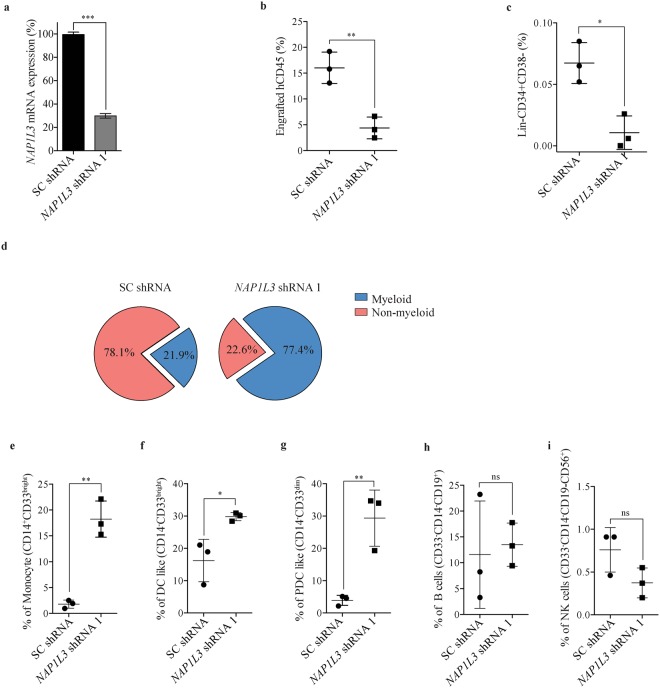

NAP1L3 downregulation is important for HSCs maintenance and SCID-repopulation capacity in vivo

To investigate the importance of human NAP1L3 in haematopoiesis we transplanted CD34+ enriched HSPC UCBs transduced with shRNA vectors against NAP1L3, or a negative control vector expressing scrambled shRNAs (Fig. 5a), into a humanised NSG-SGM3 xenograft mouse model of haematopoiesis58. Flow cytometric analysis of UCB BM cells transduced with a negative control vector revealed a robust engraftment of human nucleated haematopoietic cell (CD45+) in transplanted recipient mice at 16 weeks after transplantation (Fig. 5b). In contrast, when analysing UCB BM CD45+ cells from recipient mice transplanted with shRNA vectors efficiently knocking down NAP1L3 (Fig. 5a), a notable reduction of engraftment was observed using flow cytometric analysis (median 75% compared to control mice) (Fig. 5b). When analysing the UCB HSCs transduced with NAP1L3 shRNAs, we observed a significant reduction of these primitive cells in the NSG-SGM3 recipient mice, compared to the control cells transduced with a negative control vector (Fig. 5c).

Figure 5.

NAP1L3 suppression reduces HSC maintenance and affects differentiation in vivo. (a) Bar chart showing relative mRNA levels of NAP1L3 determined by qPCR of enriched CD34+ UCBs, transduced with shRNA vectors targeting NAP1L3 (NAP1L3 shRNA) or negative control vector (SC shRNA). NAP1L3 mRNA expression levels were normalised to the UBC gene mRNA levels. The data is represented as the mean ± s.e.m., ***p < 0.005 (unpaired t-test), n = 2. (b,c) Percentage of engraftment of CD45+ (b) or Lin−CD34−CD38+ HSC UCBs (c), transduced with shRNAs against NAP1L3 or a control vector. The UCBs were isolated from the bone marrow of recipient NSG-SGM3 mice at 16 weeks. The data is analysed by flow cytometry and is represented as the mean ± s.e.m.*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 (unpaired t-test), n = 3. (d) Pie charts depicting the proportion of myeloid (monocytes, dendritic like cells, plasmacytoid dendritic cells) and non-myeloid BM cells (lymphoid B cells, and NK cells, from the same mice as in (b) and (c). (e–i) Percentage of engraftment of monocytes (e), dendritic like cells (f), plasmacytoid dendritic cells (g), B cells (h), and NK cells (i), transduced with shRNAs against NAP1L3 or a control vector. The data is analysed by flow cytometry and is represented as the mean ± s.e.m. ns = non significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 (unpaired t-test), n = 3.

To determine the importance of NAP1L3 in cell differentiation of UCB BM cells in vivo we further analysed the engraftment of myeloid (monocytes, dendritic like cells, plasmacytoid dendritic cells) and non-myeloid BM cells (lymphoid B-cells, NK cells), in the transplanted mice. Flow cytometric analysis of UCBs transduced with NAP1L3 shRNA vectors revealed a dramatic increase in the proportion of myeloid cells, compared to UCBs transduced with non-targeting vectors (p-value = 0.0006), and a resulting reverse correlation of non-myeloid cells (Fig. 5d). In agreement with the increased proportion of myeloid UCBs when NAP1L3 is downregulated, we observed a significant increase of monocytes (Fig. 5e), dendritic like cells (DC like) (Fig. 5f), and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (PDC) (Fig. 5g), compared to the control cells. Although the proportion of lymphoid cells was substantially different between NAP1L3 knockdown cells and control cells (Fig. 5d), we did not observe any significant difference in engraftment when we compared the proportion of B cells (Figure H) and NK cells (Figure I).

Collectively, these data show that NAP1L3 has an important role in engraftment and maintenance of human HSCs and cell differentiation in vivo.

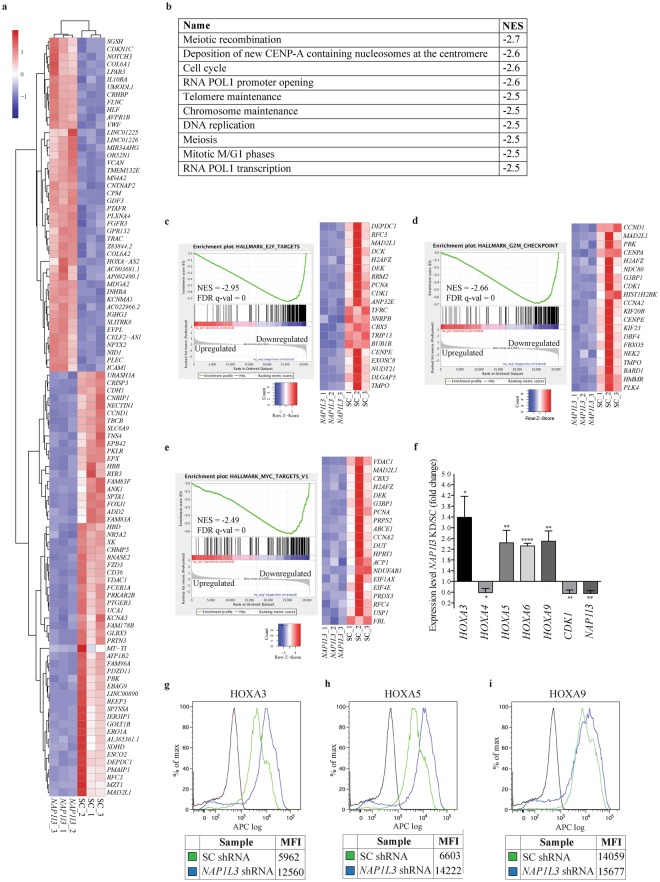

Downregulation of NAP1L3 induces suppression of transcriptional programs correlating to cell cycle progression

The importance of NAP1L3 in haematopoiesis is likely to be attributed to its function in regulating chromatin structure and consequently transcriptional gene regulation. To investigate the molecular mechanisms by which NAP1L3 contributes to human HSC function and haematopoietic differentiation, we performed RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) and global expression profiling analysis of sorted human UCB HSCs, transduced with shRNA vectors targeting NAP1L3, compared to cells transduced with a negative control vector, 72 hours post transduction of the cells.

Analysis of the RNA-Seq data showed a high degree of correlation between the triplicates and a significant differentiation between the UCB HSCs transduced with shRNAs against NAP1L3, compared to their control counterpart cells (Fig. 6a). We identified 310 genes which mRNA levels were significantly upregulated and 244 genes that were downregulated in NAP1L3 knockdown cells compared to control cells (1 or log2FC < −1; p > 0.05; p-value adjusted for multiple testing p < 0.05) (Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 6.

NAP1L3 downregulation in cord blood cells induces an expression profile linked to cell cycle progression. (a) Heatmap of the top 100 genes differentially expressed in (Lin−CD34+CD38−) UCB HSCs transduced with shRNA vectors against NAP1L3, relative to a control vector, 72 hours post transduction. Up regulated genes are shown in red and down regulated genes are shown in blue. The data represents clustering of the individual experiments, n = 3. (b) List of the ten most significant correlations between the predefined MSigDB GO Biocarta gene set pathways and the gene expression changes resulting from shRNA-based downregulation of NAP1L3, relative to UCB HSCs transduced with negative control vectors. Normalised enrichment score (NES) for each pathway is shown in the right column. (c–e) Enrichment plots of gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of gene expression profiling changes in response to NAP1L3 knockdown in UCBs, demonstrating significant negative correlations with E2F targets (c), G2/M checkpoint (d) and MYC targets (e). The bar charts represent the top ranked correlations in the predefined MSigDB: H hallmark collections. The heatmap on the right in Fig. 5c–e shows the relative level of gene expression (red = high, blue = low) of the leading edge gene subset. NES scores, FDR-q values and up or downregulated genes as a consequence of NAP1L3 knockdown compared to control cells, are indicated in the diagrams (f). qPCR analysis of mRNA levels (normalised to UBC) of genes showing changes in expression in RNA-Seq of CD34+ HSPC UCBs cells transduced with shRNA against NAP1L3, relative to cells transduced with control vectors, 72 hours post transduction. The data is represented as the mean ± s.e.m., *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.001 (unpaired t-test), n = 3. (g–i) Flow cytometric quantification of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of intracellular HOXA3 (g), HOXA5 (h) and HOXA9 (i), protein levels, of CD34+ HSPC UCBs cells transduced with shRNA against NAP1L3 or cells transduced with control vectors, 72 hours post transduction.

To identify biological processes and pathways involving NAP1L3, which are important for the function of UCB HSCs, we performed gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)59. GO-term analysis of Biocarta gene set pathways revealed that the top ten most significant correlations were all negatively correlated to cell cycle regulation, chromosome function, recombination and replication (Fig. 6b). Moreover, additional GSEA analysis, with a focus on molecular signatures, showed that the most significant correlations to the transcriptome profile, due to NAP1L3 downregulation in UCB HSCs, encompassed a gene set enriched for; E2F targets (false discover rate (FDR) q value = 0.0, normalised enrichment score (NES) = −3.0) (Fig. 6c), a signature of genes involved in G2/M checkpoint (FDR q value = 0.0, NES −2.7) (Fig. 6d) and MYC targets (FDR q value = −0.0, NES −2.5) (Fig. 6e). In addition to the described pathways and gene signatures, we also observed that many of the genes in the HOXA cluster were significantly upregulated in the RNA-seq data (Supplementary Table S1).

To validate the RNA-Seq data and the GSEA analysis, we performed additional shRNA-mediated suppression of NAP1L3 in UCB HSCs. qPCR analysis of mRNA expression revealed that nearly all the genes selected for validation (except for HOXA4) showed the same trend and comparable levels of changes to the RNA-seq results in human UCB HSCs transduced with shRNA vectors targeting NAP1L3, compared to cells transduced with a negative control vector (Fig. 6f). Further flow cytometric assessment of the NAP1L3 shRNA-targeted UCBs with a significant reduction in NAP1L3 protein levels in Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 3, demonstrated a more than two-fold upregulation of HOXA3 and HOXA5 of protein levels, whereas no significant change was observed for HOXA9 (Fig. 6g–i).

To investigate how enforced expression of NAP1L3 affected HOXA3, HOXA5 and HOXA9 gene expression levels, qPCR and flow cytometric analysis was performed on UCBs transduced with lentiviral vectors expressing of NAP1L3. The analysis revealed a close to two-fold increased expression of NAP1L3 on both mRNA and protein levels over endogenous levels, but no significant change was observed for the HOXA genes (Supplementary Fig. 4c–e).

In conclusion, both the RNA-Seq analysis and the validation showed that downregulation of NAP1L3 in UCB HSCs induces gene expression signatures associated to cell cycle progression and HOXA gene expression.

Discussion

Regulation of chromatin dynamics is important in all biological processes where DNA accessibility needs to be regulated60. Histone chaperones constitute a family of chromatin regulators that have an important function in these processes. Our studies identified a novel role of the histone chaperone NAP1L3 in early haematopoiesis. Moreover, we found NAP1L3 to be highly expressed in HSCs, and showed that loss of function of NAP1L3 in primitive human UCB HSCs had a remarkable impact on the survival and proliferation of HSCs and cell differentiation in vivo. These effects appears to be associated to its role in the transcriptional regulation of genes, which in turn encode the proteins required for proper cell cycle progression and differentiation.

The Nap1 family of histone chaperones has previously been implicated in cell cycle regulation via functional and physical interactions with mitotic cyclins in both budding yeast and frogs35,61,62. In addition, Nap1 null mutants in S. pombe cause a delay in mitosis63. In contrast, we here show that NAP1L3 is required for maintenance of HSCs and that its downregulation induces an arrest in the G0 phase of the cell cycle. Whilst further studies are required to delineate if the induced growth arrest due to NAP1L3 downregulation is reversible (quiescence) or irreversible (senescence), it is possible that NAP1L3 controls HSC cell-cycle entry and proliferation in a normal setting. Nevertheless, this seems to, at least in part, be mediated by transcriptional regulation of signalling pathways with essential functions in cell cycle progression, including MYC and E2F targets. Consistent with this notion, the NAP1 family have previously been shown to physically interact with and to augment p300/CBP gene transcription of E2F1 and p53, both of which play a critical role in cell cycle progression and apoptosis29. The importance of NAP1L3 in primitive haematopoietic cells may represent its multifaceted functions in various signalling pathways (e.g. cell cycle progression, apoptosis via MYC and E2F targets). On the other hand, it may be reflective of a critical function in one signalling pathway causing secondary effects in several other processes. Further studies are clearly needed to fully understand the various aspects of NAP1L3 function in regulating HSC fates. Nonetheless, our data suggest that NAP1L3 is involved in transcriptional regulation of HSC cycling.

Although high expression of NAP1L3 is restricted to HSCs, its importance in haematopoiesis might also be related to HSC reconstitution activities since gene knockdown of the human NAP1L3 cause abnormal mature blood lineage regeneration after transplantation. One explanation for this phenomenon might be that NAP1L3 establishes a chromatin landscape in HSCs, which is crucial for primitive haematopoietic cell function that is further propagated via epigenetic mechanisms to more mature haematopoietic cells. This is supported by the fact that the NAP1 family of proteins has been reported to be involved in development and cell differentiation in various species46,49–52,64–66, tissues, and cell types47,67,68, including haematopoiesis in Xenopus53 and epigenetic transcriptional regulation10–14. Together these findings show that the Nap1 family of proteins are emerging as regulators of development and cell differentiation. Surprisingly, our global transcriptome analysis in NAP1L3 downregulated UCBs did not identify strong correlations to signalling pathways with a known role in haematopoietic differentiation. However, the mRNA levels of five out of 13 HOXA genes are significantly upregulated in UCBs upon suppression of NAP1L3 and two out of three also show increased protein levels. Although the mechanistic basis for this remains to be determined, it is possible that the important role of NAP1L3 in HSCs maintenance and haematopoietic restoration shown in this study, may involve epigenetic transcriptional regulatory mechanisms of the HOXA genes in a similar way to what has been previously reported14,26,29,34,36,37,42. Nonetheless, it is known that the HOXA cluster of genes are highly expressed in uncommitted HSPCs compared to mature cells and they play a pivotal role in self-renewal and haematopoietic differentiation69. Although the mechanisms by which NAP1L3 contribute to regulation of the HOXA gene cluster in haematopoiesis is unknown, this correlation may provide a plausible explanation for the observed effects in differentiation.

Surprisingly, both overexpression and loss-of-function of Nap1l3 produce similar phenotypes in primitive haematopoietic and differentiated cells. A likely explanation for this is that forced overexpression at non-physiological levels of the protein causes dominant negative effects. It is well established that over-enforced expression of wild-type proteins can cause a mutant phenotype due to competition with other macromolecules and/or non-functional subassemblies/disassembly’s, leading to a reduced function of the protein70. However, enforced expression of NAP1L3, which cause effects in haematopoietic stem cell function and maintenance, do not affect HOXA gene regulation, suggesting that deregulation of other downstream effectors may play a critical role in these processes. Regardless, the overexpression and subsequent phenotype in HSCs and cell differentiation confirms the importance of Nap1l3 in haematopoiesis.

In contrast to many other transcription factors and epigenetic enzymes with a role in HSC function and cellular differentiation, NAP1L3 has not been reported to be genetically mutated in haematological malignancies71 or to be associated with clinical outcomes2,54,72. However, NAP1L3 is significantly overexpressed in AML HSPCs compared to normal HSPCs54. Although the transplanted animals in this study did not display any features of malignant transformation into leukaemia, this overexpression in AML cells together with a strong association to HOXA genes, cell cycle progression, MYC and E2F, indicate that NAP1L3 may have a role in leukemogenesis. Future studies will investigate whether NAP1L3 contributes to cellular transformation or maintenance of AML by modulating cell cycle progression and HOXA, MYC, and E2F gene expression.

Methods

Isolation and culturing of primary cells

Sorted primary murine cKit+ and LSK cells were cultured in SFEMII media (Stemcell technology) supplemented with; rhFlt3/Flk-2 ligand (Stemcell technology), rhTPO (Stemcell technology), rhIL-6 (R&D system), rmIL-3 (R&D systems) and rmSCF (R&D systems) at a concentration of 20 ng/mL. UCB samples were provided by the Karolinska Hospital (Stockholm, Sweden) with informed consent from the parents and all investigation has been performed according ethical standards and to the declaration of Helsinki and to national and international guidelines. The experiments on the UCB samples were approved by The Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (Dnr: 2012/480-31/1).

Lymphoprep solution (Invitrogen) was used to isolate mononuclear cell fraction and CD34+ cells were enriched by using CD34 microbead kit (Miltenyi Biotec). The CD34+ and sorted HSC UBC cells were expanded in SFEMII media supplemented with; rhIL-6, rhIL-3 (R&D systems), rhFl3/Flk-2 ligand, rhTPO and rhSCF (R&D systems) all in final concentrations of 20 ng/mL.

Mice

All mice studies were performed in the pathogen-free animal facility at Karolinska Institutet, Huddinge, Sweden. The animal studies were approved by Linköping Animal Research Ethics Committee, Sweden and the Swedish board of agriculture (Ethical number; ID 530) and all investigations were performed in accordance with national and international guidelines and regulations. The C57BL/6 J wt mice and the NOD-scid IL2Rgnull-3/GM/SF, NSG-SGM3 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. The Cas9 mice were bought from Jackson Laboratory, stock: Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1.1(CAG-cas9*,-EGFP)Fezh/J.

Bone marrow transplantation

Congenic non-competitive engraftment was carried out by transplanting 20,000–50,000 cKit+ or LSK CD45.1+ cells and 200,000 unfractionated CD45.2 supporter cells into lethally radiated (950 cGy) CD45.2+ mice via tail vein injection. The level of engraftment of donor cells was investigated at two, five, eight and 16 weeks post transplantation by sampling peripheral blood via the tail vein of transplanted mice. The level of engraftment in the bone marrow was determined by flow cytometric analysis of bone marrow cells extracted from the tibia and femur of euthanised mice eight weeks post transplantation to detect CD45.1 + cells. Mouse xenograft transplantations were performed by sub-lethal radiation (220 cGy) of humanised NSG-SGM3 mice aged six to eight weeks. 50,000–100,000 CD34+ UCBs were injected per mouse, six-12 hours post irradiation via tail vein injection. Ciprofloxacin antibiotic was administrated via drinking water to avoid infection after radiation. To determine the level of engraftment in euthanised recipient mice, human UCBs in the BM, tibia and femur were collected at six weeks post transplantation, where engraftment efficiency (hCD45+) and cell population frequency were analysed by flow cytometry.

Lentiviral production and transduction of primary cells

Transfection and transduction were performed as previously described73. Briefly, 293-FT cell were transfected with lentiviral targeting, psPAX2 packaging and VSV-G envelope plasmids constructs using the calcium phosphate method. The produced virus particles were harvested 24 h and 48 h after transduction and thereafter concentrated by 16 h centrifugation at 5000 × g. The virus pellet was then washed and re-suspended in media supplemented with growth factors according to the cell culture media requirements of the target cells. Lentiviral transduction was performed by adding the virus supernatant to primary cells maintained in ultra-low attachment plates (Corning) to a final volume of 500 μL. Thereafter, the cells with the virus was spinoculated for two hours at 1000 × g. After centrifugation, the cells were exposed to the virus for 12 hours. After washing, the cells were re-suspended and cultured in fresh SFEMII media supplemented with cytokines for two days. The transduced cells were selected with puromycine (2 ug/mL) for 48 hours.

Flow cytometry analysis and sorting

To investigate the level of engraftment in BM of transplanted mice, BM cells were harvested from tibia and femur bones and after stained with purified anti-CD16/CD32 (Fc-block), and with anti-mouse lineage markers (CD11b, Gr-1, CD3, CD19 NK1.1 and TER119) together with CD117 (cKit) and Sca-1, for 20 minutes at 4 °C. Cells were washed and resuspended in promidium iodine (PI) (Invitrogen) to visualise live cells. To determine the level of engraftment of human CD45+ cells in transplanted NSG-SGM3 mice, BM cells were isolated from tibia and femur. The isolated BM cells were first subjected to Fc-blocking antibodies (ChromPure Mouse IgG, Jackson ImmmunoResearch) and thereafter stained with lineage antibodies (Lin; CD56, CD235a, CD3, CD19, CD11b, CD14) as well as CD34 and CD38. The cells were then incubated with Near-IR Live/Dead marker to detect live cells. Flow cytometric analysis was performed with a 4-laser BD LSRFortessa. To analyse the different mature human cell populations in NSG-SGM3 transplanted mice, the BM cells were isolated and stained with CD11b, CD14, CD56, CD19, CD33, CD16, CD3, HLA-DR and CD45. To exclude dead cells in the analysis, the Live/Dead fixable Aqua dead cells stain kit (Invitrogen) was used.

High resolution sorting of seven fractions of mouse HSCs and progenitor cells was done according to a previously published protocol56. For sorting of Lin− cKit+ or LSK, BM cells they were first isolated by crushing iliac crest bones, femurae and tibiae of C57BL/6 J mice. cKit+ cells were enriched by depletion of mature cells using magnetic Dynabeads (Invitrogen) and purified using antibodies specific for Ter119, B220, Gr1, CD3, Nk1.1 and CD11b. The cells were then stained with flourochrome-conjugated CD117 (cKit), Sca-1 and Lin antibodies. Dead cells were excluded by staining the cells with PI.

To sort HSC UBCs, CD34+ cells they were enriched as described above and re-suspended in PBS with 2% FBS and stained with purified anti-human Fc block purified antibody. Thereafter, cells were stained with fluorescence-conjugated antibodies; Lin, CD45, CD34, CD38 antibodies. Dead cells were excluded using PI. Cell sorting was performed on BD FACS Aria III cell sorter or BD FACS FUSION BSL2 using a 85 or 100 microns nozzle. All analysis was performed using FlowJo Version 9.3.3 software (TreeStar). Monoclonal antibodies and conjugations used in this study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Antibodies used for flow cytometry.

| Antibody | Conjugated | Clone | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-mouse TER-119 | Purified | TER-119 | Biolegend |

| Anti-mouse CD3 | Purified | 17A2 | Biolegend |

| Anti-mouse/Human CD45R/B220 | Purified | RA3-6B2 | Biolegend |

| Anti-mouse Ly-6G/Ly-6C (Gr-1) | Purified | RB6-8C5 | Biolegend |

| Anti-mouse NK1.1 | Purified | PK136 | Biolegend |

| Anti-mouse CD11B | Purified | M1/70 | Biolegend |

| Anti-mouse CD16/32 | Purified | 93 | Biolegend |

| Anti-mouse CD117 (c-kit) | APC-Cy7 | 2B8 | Biolegend |

| Anti-mouse CD4 | PECy5 | RM4-5 | Biolegend |

| Anti-mouse CD8a | PECy5 | 53-6.7 | Biolegend |

| Anti-mouse/Human CD11b (Mac1) | PECy5 | M1/70 | Biolegend |

| Anti-mouse CD11c | PECy7 | N418 | Biolegend |

| Anti-mouse CD16/32 | PECy7 | 93 | Biolegend |

| Anti-mouse CD19 | PE-CF594 | 1D3 | BD |

| Anti-mouse CD41 | FITC | MWReg30 | Biolegend |

| Anti-mouse CD45R/B220 | PECy5 | RA3-6B2 | Biolegend |

| Anti-mouse CD48 | PE | HM48-1 | Biolegend |

| Anti-mouse CD105 | Biotin | MJ7/18 | Biolegend |

| Anti-mouse CD117 (cKit) | PerCP-eFluor710 | 2B8 | eBioscience |

| Anti-mouse CD117 (cKit) | APCeFluor780 | 2B8 | eBioscience |

| Anti-mouse CD127 (IL7Ra) | Biotin | A7R34 | Biolegend |

| Anti-mouse CD135 (Flt3) | PE | A2F10 | Biolegend |

| Anti-mouse CD150 | APC | TC15-12F12.2 | Biolegend |

| Anti-mouse Gr1(Ly6G/Ly6C) | PECy5 | RB6-8C5 | Biolegend |

| Anti-mouse Ly-6C | APC | HK1.4 | Biolegend |

| Anti-mouse Ly6D | FITC | 49-H4 | Biolegend |

| Anti-mouse NK1.1 | PECy5 | PK136 | Biolegend |

| Anti-mouse Sca1 | PB | D7 | Biolegend |

| Anti-mouse Streptavidin | QD655 | Invitrogen | |

| Anti-mouse TER119 | PECy5 | TER-119 | Biolegend |

| Anti-mouse TER119 | PECy5.5 | TER-119 | eBioscience |

| Ki-67 | FITC | B56 | BD |

| Anti-human CD56 | PE-Cy5 | HCD56 | Biolegend |

| Anti-human CD235a | PE-Cy5 | HIR2 | Biolegend |

| Anti-human CD3 | PE-Cy5 | HIT3a | Biolegend |

| Anti-human CD19 | PE-Cy5 | HIB19 | Biolegend |

| Anti-human CD14 | PE-Cy5 | 6103 | Biolegend |

| Anti-human CD34 | APC | 581 | Biolegend |

| Anti-human CD38 | PE-Cy7 | HB7 | BD |

| Anti-human CD45 | BV786 | HI30 | BD |

| Anti-human HLA-DR | APC-Cy7 | L243 | Biolegend |

| Anti-human CD11b | Alexa Fluor488 | ICRF44 | BD |

| Anti-human CD14 | PerCP-Cy5.5 | HCD14 | Biolegend |

| Anti-human CD56 | BV605 | HCD56 | Biolegend |

| Anti-human CD19 | BV786 | SJ25c1 | BD |

| Anti-human CD33 | PE | WM53 | Biolegend |

| Anti-human CD16 | PE-CF594 | 3G8 | BD |

| Anti-human CD3 | PE-Cy5 | HIT3a | Biolegend |

| Anti-human CD45 | APC | HI30 | Biolegend |

| Anti NAP1L3 | Purified | AA1-506 | Antibodies-online |

| Anti homeobox A3 | Purified | AA 414-443 | Antibodies-online |

| Anti homeobox A5 | Purified | Polyclonal Middle Region | Antibodies-online |

| Anti-HOXA9 | Purified | AA 245–272 | Antibodies-online |

Intracellular protein staining

To determine intracellular protein levels by flow cytometry, we used transcription factor staining buffer set (eBioscience, 00-5523-00). Briefly cells were fixed with fixation buffer for 20 minutes and after washing incubated with permeabilisation buffer for 20 minutes. The cells were incubated with primary antibodies (information about antibodies are listed in Table 1) diluted in permeabilisation buffer, then washed cells stained with secondary antibody (anti-rabbit IgG, F fragment Alexa Flour 647 conjugate, Cell signaling) for 20 minutes. The stained cells were washed and resuspended in PBS + 2% FBS for flow cytometry.

Cell cycle analysis

UCB HSCs were washed with PBS and stained with first anti-human CD16/32 and then with fluorescence-conjugated anti-human Lin, CD34 and CD38 antibodies. After washing the cells with PBS, they were stained with Live/Dead Fixable Near IR viability dye for 20 minutes at room temperature (RT) and then washed with cold PBS. Cells were fixed with 1% of formaldehyde for 10 min at RT and the crosslinking was stopped with 0.1 M Glycine. 0.05% Triton X-100 in PBS was used to permeabilise the cells and after washing the cells once in PBS, they were incubated in 10 uL of Ki67 for 2 hours at 4 °C in the dark. Washed cells were resuspended in 0.5 μg/mL DAPI for 20 min at RT before FACS analysis using Fortessa LSRII (BD).

Serial replating assays

Transduced cells were selected with Puromycine in concentration of 2 μg/ml for 48 hours and thereafter resuspended in Methocult H4435 (Stemcell technology) at concentration of 1 cell in 150 μl per well in 96-well plates. After 14 days, the colonies from each well were washed with PBS, resuspended in 20 μl of IMDM and cultured in new 96-well plate contain 150 μl Methocult.

Apoptosis analysis

After staining THP-1 cells with fluorescence-conjugated antibodies and Live/Dead fixable marker as described above, the cells were washed and re-suspended in Annexin-binding buffer (BioLegend) containing Annexin V FITC (BioLegend) for 20 minutes AT RT. After another round of washing the cells were re-suspended in Annexin-binding buffer and analysed by flow cytometric analysis. The absolute number of human cells was analysed by a high-throughput automated plate reader (BD LSRFortessa).

Vectors and Molecular Cloning

The inducible gRNA vectors were generated as previously described74. Briefly, gRNAs were designed using Optimised CRISPR Design - MIT (http://crispr.mit.edu), and subsequently cloned into the inducible vector pRSITEP-U6Tet-(sh)-EF1-TetRep-2A-Puro (Cellecta). PCR amplification using primers homologous to upstream and downstream genomic regions of the NAP1L3 gRNA target site were used to generate DNA fragments that were sub-cloned for sequencing of in total 10 individual clones. For cloning Nap1l3 cDNA into an overexpression vector, cDNA was purchase from Thermoscientific and PCR amplified by primers providing overhangs with restriction enzyme sites; XbaI, NotI. After cutting, the cDNA was cloned into pCHD-the MCS-EF1 lentivector from Biocat (pCDH-MSCV-MCS-EF1-GFP-Puro, Cat. No. CD713B-1). All oligos used in the study are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Oligos used in the studies.

| Target site | Application | Forward oligo (5′ > 3′) | Reverse oligo (5′ > 3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| mNap1l3* | qPCR | ||

| mHprt1** | qPCR | ||

| hNAP1L3 | qPCR | ACCAGAGGTGAAAGCTGAA | CCTGGGGGACTTCTTTAGGA |

| hUBC | qPCR | CTGGAAGATGGTCGTACCCTG | GGTCTTGCCAGTGAGTGTCT |

| hHOXA3 | qPCR | CTCCAGCTCAGGCGAAAG | ACAGGTAGCGGTTGAAGTGG |

| hHOXA4 | qPCR | CATGTCAGCGCCGTTAACC | ACCTGCTGCCGGGTGTAG |

| hHOXA5 | qPCR | CGCCCAACCCCAGATCTAC | CCGCCTATGTTGTCATGACTTATG |

| hHOXA6 | qPCR | CGCGGGTGCTGTGTATG | CCTTCTCCAGCTCCAGTGTC |

| hHOXA9 | qPCR | CCCCATCGATCCCAATAACC | CCAGGGTCTGGTGTTTTGTATAGG |

| hCDK1 | qPCR | GGAAACCAGGAAGCCTAGCA | GATCATAGATTAACATTTTCGAGAGCAA |

| mNAP1l3 | OE cloning | ANGCTCTAGAATGGCAGAAGCGGATCCTAAAATG | ANGCGCGGCCGCCTACTTGTAGTACTTCCTATTT CATAAT |

| mNAP1l3 | CRISPR gRNA | ACCGGCGCCTCTTCAGCAACCCCAT | AAACATGGGGTTGCTGAAGAGGCGC |

| mNAP1l3 | PCR mutation analysis | CCACAGCTGCTGCAGTCC | GCCCTTCTGGAAGGCTCAG |

| mNAP1l3 | Sequencing mutation analysis | CAGTCCGTGTTGCCACTG |

*mNap1l3 Taqman probes was purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific (Mm01214875_s1).

**mHrpth Taqman probes was purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific (Mm03024075_m1).

CFU-C assay

The sorted normal mouse (cKit+/LSK) and human BM (Lin−CD34+CD38−) were seeded in the MethoCult semi-solid media (Stem Cell Technologies) for mouse 150–300 cells/1 cm2 dish (M3434) and for human (M4435) 200–400 cells/1 cm2 dish for 10–12 days (mouse) or 12–14 days (human) respectively. The colonies were stained with Giemsa (Sigma) and scored under microscope, where a cluster of more than 50 cells was defined as one colony.

RNA-Sequencing

Total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen) from 20 × 105 FACS-sorted Lin−CD34+CD38− UCBs. TotalScriptTM RNA-seq kit (Epicentre, Madison, WI) was used to create strand specific pair-end RNA libraries according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Libraries were sequenced by using the Illumina platform. RNA-Seq reads were mapped to the Ensembl Homo_sapiens and GRCh38 reference genome using the STAR aligner. Gene assignment was performed using featureCounts. Normalisation and the sample group comparisons were performed using DESeq. 2. GSEA analysis was performed to analyse the enrichment of the gene sets following the developer’s protocol 60 (http://www.broad.mit.edu/gsea/). The Biocarta gene sets (CP) were used to identify pathways significantly associated with genes that were up or downregulated as a result of NAP1L3 downregulation in UCBs. As an approach to identify correlations to defined biological states or processes the Hallmark gene sets (H) was used to analyse enrichments of gene sets.

Statistical analysis

Τhe unpaired t-tests for the statistical analysis of our data were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the GEO repository: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE106170.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank Emma Andersson and Linus Christerson for help with the Cas9 mice. We thank Karin Belander-Strålin for input in clinical aspects of childhood AML and Ying Qu for helping with the RNA-Seq analysis. We thank Cecilia Götherström and the National Cord Blood bank at the Karolinska University Hospital for providing the umbilical cord blood cells. We would like to acknowledge the MedH Core Flow Cytometry facility (Karolinska Institutet), supported by KI/SLL, for providing cell sorting services, cell analysis services, technical expertise, and scientific input. We also would like to thank the Affymetrix core facility at Novum, BEA, Bioinformatics, and Expression Analysis, which is supported by the board of research at the Karolinska Institute and the research committee at the Karolinska hospital. This work was supported by the Wallenberg Foundation, The Swedish Cancer Society, Magnus Bergwalls Foundation, Karolinska Institutet, Åke Wibergs Foundation, and Dr. Åke Olsson Foundation for Haematological Research.

Author Contributions

Y.H. designed and performed experiments, analysed data, prepared the figures, and wrote the manuscript. S.K. helped with flow cytometry design, analysis and cell sortings. G.T. performed experiments and analysed data. D.C. and T.B. cloned and validated the CRISPR-Cas9. E.K.D. optimised the conditions for the co-culture system. J.B. generated the inducible gRNA and shRNA vectors. A.K. established the RNA-Seq method, generated RNA-Seq libraries and analysed data. E.W. validated the CRISPR-Cas9 experiments. N.K. designed and analysed flow cytometry data for the NSG mice. R.M. supervised establishment of RNA-Seq method, analysed data and provided input. M.A. designed the gRNA and shRNA vectors and provided input. H.Q. helped to design the studies, analysis of the experiment and supervision of Y.H. J.W. conceived the project, supervised the study, analysed the data, interpreted result and wrote the manuscript. All authors participated in editing of the manuscript and reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-29518-z.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Seita J, Weissman IL. Hematopoietic stem cell: self-renewal versus differentiation. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews. Systems biology and medicine. 2010;2:640–53. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orkin SH, Zon LI. Hematopoiesis: an evolving paradigm for stem cell biology. Cell. 2008;132:631–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ishimi Y, Yasuda H, Hirosumi J, Hanaoka F, Yamada M. A protein which facilitates assembly of nucleosome-like structures in vitro in mammalian cells. Journal of biochemistry. 1983;94:735–44. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a134414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang L, et al. Histones in transit: cytosolic histone complexes and diacetylation of H4 during nucleosome assembly in human cells. Biochemistry. 1997;36:469–80. doi: 10.1021/bi962069i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mosammaparast N, Ewart CS, Pemberton LF. A role for nucleosome assembly protein 1 in the nuclear transport of histones H2A and H2B. EMBO J. 2002;21:6527–38. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujii-Nakata T, Ishimi Y, Okuda A, Kikuchi A. Functional analysis of nucleosome assembly protein, NAP-1. The negatively charged COOH-terminal region is not necessary for the intrinsic assembly activity. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:20980–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hammond CM, Stromme CB, Huang H, Patel DJ, Groth A. Histone chaperone networks shaping chromatin function. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2017;18:141–58. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2016.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishimi Y, Kikuchi A. Identification and molecular cloning of yeast homolog of nucleosome assembly protein I which facilitates nucleosome assembly in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:7025–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ito T, Bulger M, Kobayashi R, Kadonaga JT. Drosophila NAP-1 is a core histone chaperone that functions in ATP-facilitated assembly of regularly spaced nucleosomal arrays. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3112–24. doi: 10.1128/MCB.16.6.3112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asahara H, et al. Dual roles of p300 in chromatin assembly and transcriptional activation in cooperation with nucleosome assembly protein 1 in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:2974–83. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.9.2974-2983.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berndsen CE, et al. Molecular functions of the histone acetyltransferase chaperone complex Rtt109-Vps75. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2008;15:948–56. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moshkin YM, et al. Histone chaperones ASF1 and NAP1 differentially modulate removal of active histone marks by LID-RPD3 complexes during NOTCH silencing. Molecular cell. 2009;35:782–93. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schimmack S, et al. A mechanistic role for the chromatin modulator, NAP1L1, in pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm proliferation and metastases. Epigenetics & chromatin. 2014;7:15. doi: 10.1186/1756-8935-7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xue YM, et al. Histone chaperones Nap1 and Vps75 regulate histone acetylation during transcription elongation. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33:1645–56. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01121-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buchanan L, et al. The Schizosaccharomyces pombe JmjC-protein, Msc1, prevents H2A.Z localization in centromeric and subtelomeric chromatin domains. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000726. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kepert JF, Mazurkiewicz J, Heuvelman GL, Toth KF, Rippe K. NAP1 modulates binding of linker histone H1 to chromatin and induces an extended chromatin fiber conformation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:34063–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507322200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okuwaki M, Kato K, Nagata K. Functional characterization of human nucleosome assembly protein 1-like proteins as histone chaperones. Genes to cells: devoted to molecular & cellular mechanisms. 2010;15:13–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2009.01361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tachiwana H, et al. Nap1 regulates proper CENP-B binding to nucleosomes. Nucleic acids research. 2013;41:2869–80. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tachiwana H, Osakabe A, Kimura H, Kurumizaka H. Nucleosome formation with the testis-specific histone H3 variant, H3t, by human nucleosome assembly proteins in vitro. Nucleic acids research. 2008;36:2208–18. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luger K, Dechassa ML, Tremethick DJ. New insights into nucleosome and chromatin structure: an ordered state or a disordered affair? Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2012;13:436–47. doi: 10.1038/nrm3382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen X, et al. Histone Chaperone Nap1 Is a Major Regulator of Histone H2A-H2B Dynamics at the Inducible GAL Locus. Mol Cell Biol. 2016;36:1287–96. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00835-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Del Rosario BC, Pemberton LF. Nap1 links transcription elongation, chromatin assembly, and messenger RNP complex biogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:2113–24. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02136-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang W, Nordeen SK, Kadonaga JT. Transcriptional analysis of chromatin assembled with purified ACF and dNAP1 reveals that acetyl-CoA is required for preinitiation complex assembly. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39819–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000713200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuryan BG, et al. Histone density is maintained during transcription mediated by the chromatin remodeler RSC and histone chaperone NAP1 in vitro. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:1931–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109994109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levchenko V, Jackson V. Histone release during transcription: NAP1 forms a complex with H2A and H2B and facilitates a topologically dependent release of H3 and H4 from the nucleosome. Biochemistry. 2004;43:2359–72. doi: 10.1021/bi035737q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luebben WR, Sharma N, Nyborg JK. Nucleosome eviction and activated transcription require p300 acetylation of histone H3 lysine 14. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:19254–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009650107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohkuni K, Shirahige K, Kikuchi A. Genome-wide expression analysis of NAP1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2003;306:5–9. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)00907-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okuwaki M, Kato K, Shimahara H, Tate S, Nagata K. Assembly and disassembly of nucleosome core particles containing histone variants by human nucleosome assembly protein I. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:10639–51. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.23.10639-10651.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shikama N, et al. Functional interaction between nucleosome assembly proteins and p300/CREB-binding protein family coactivators. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:8933–43. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.23.8933-8943.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Son O, et al. Identification of nucleosome assembly protein 1 (NAP1) as an interacting partner of plant ribosomal protein S6 (RPS6) and a positive regulator of rDNA transcription. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2015;465:200–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.07.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walfridsson J, Khorosjutina O, Matikainen P, Gustafsson CM, Ekwall K. A genome-wide role for CHD remodelling factors and Nap1 in nucleosome disassembly. EMBO J. 2007;26:2868–79. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walter PP, Owen-Hughes TA, Cote J, Workman JL. Stimulation of transcription factor binding and histone displacement by nucleosome assembly protein 1 and nucleoplasmin requires disruption of the histone octamer. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6178–87. doi: 10.1128/MCB.15.11.6178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang S, Frappier L. Nucleosome assembly proteins bind to Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1 and affect its functions in DNA replication and transcriptional activation. J Virol. 2009;83:11704–14. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00931-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wunsch A, Jackson V. Histone release during transcription: acetylation stabilizes the interaction of the H2A-H2B dimer with the H3-H4 tetramer in nucleosomes that are on highly positively coiled DNA. Biochemistry. 2005;44:16351–64. doi: 10.1021/bi050876o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kellogg DR, Kikuchi A, Fujii-Nakata T, Turck CW, Murray AW. Members of the NAP/SET family of proteins interact specifically with B-type cyclins. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:661–73. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.3.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gadad SS, Shandilya J, Swaminathan V, Kundu TK. Histone chaperone as coactivator of chromatin transcription: role of acetylation. Methods in molecular biology. 2009;523:263–78. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-190-1_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee JY, Lee J, Yue H, Lee TH. Dynamics of nucleosome assembly and effects of DNA methylation. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:4291–303. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.619213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gao J, et al. NAP1 family histone chaperones are required for somatic homologous recombination in Arabidopsis. The Plant cell. 2012;24:1437–47. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.096792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Machida S, et al. Nap1 stimulates homologous recombination by RAD51 and RAD54 in higher-ordered chromatin containing histone H1. Scientific reports. 2014;4:4863. doi: 10.1038/srep04863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou W, et al. Distinct roles of the histone chaperones NAP1 and NRP and the chromatin-remodeling factor INO80 in somatic homologous recombination in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant journal: for cell and molecular biology. 2016;88:397–410. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Higgins JM, Herbert M. Nucleosome assembly proteins get SET to defeat the guardian of chromosome cohesion. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003829. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moshkin YM, et al. Histone chaperone NAP1 mediates sister chromatid resolution by counteracting protein phosphatase 2A. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003719. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shintomi K, Takahashi TS, Hirano T. Reconstitution of mitotic chromatids with a minimum set of purified factors. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:1014–23. doi: 10.1038/ncb3187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lankenau S, et al. Knockout targeting of the Drosophila nap1 gene and examination of DNA repair tracts in the recombination products. Genetics. 2003;163:611–23. doi: 10.1093/genetics/163.2.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Z, et al. Molecular and reverse genetic characterization of NUCLEOSOME ASSEMBLY PROTEIN1 (NAP1) genes unravels their function in transcription and nucleotide excision repair in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Plant journal: for cell and molecular biology. 2009;59:27–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Galichet A, Gruissem W. Developmentally controlled farnesylation modulates AtNAP1;1 function in cell proliferation and cell expansion during Arabidopsis leaf development. Plant physiology. 2006;142:1412–26. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.088344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu Y, et al. The Histone Chaperone NRP1 Interacts with WEREWOLF to Activate GLABRA2 in Arabidopsis Root Hair Development. The Plant cell. 2017;29:260–76. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patel FB, et al. The WAVE/SCAR complex promotes polarized cell movements and actin enrichment in epithelia during C. elegans embryogenesis. Dev Biol. 2008;324:297–309. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bogdan S, Grewe O, Strunk M, Mertens A, Klambt C. Sra-1 interacts with Kette and Wasp and is required for neuronal and bristle development in Drosophila. Development. 2004;131:3981–9. doi: 10.1242/dev.01274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kimura S. The Nap family proteins, CG5017/Hanabi and Nap1, are essential for Drosophila spermiogenesis. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:922–9. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schroter RH, et al. kette and blown fuse interact genetically during the second fusion step of myogenesis in Drosophila. Development. 2004;131:4501–9. doi: 10.1242/dev.01309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Attia M, Rachez C, De Pauw A, Avner P, Rogner UC. Nap1l2 promotes histone acetylation activity during neuronal differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:6093–102. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00789-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abu-Daya A, et al. Zygotic nucleosome assembly protein-like 1 has a specific, non-cell autonomous role in hematopoiesis. Blood. 2005;106:514–20. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bagger FO, et al. BloodSpot: a database of gene expression profiles and transcriptional programs for healthy and malignant haematopoiesis. Nucleic acids research. 2016;44:D917–24. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Riddell J, et al. Reprogramming committed murine blood cells to induced hematopoietic stem cells with defined factors. Cell. 2014;157:549–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pronk CJ, et al. Elucidation of the phenotypic, functional, and molecular topography of a myeloerythroid progenitor cell hierarchy. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:428–42. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hogge DE, Lansdorp PM, Reid D, Gerhard B, Eaves CJ. Enhanced detection, maintenance, and differentiation of primitive human hematopoietic cells in cultures containing murine fibroblasts engineered to produce human steel factor, interleukin-3, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Blood. 1996;88:3765–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Billerbeck E, et al. Development of human CD4+FoxP3+regulatory T cells in human stem cell factor-, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-, and interleukin-3-expressing NOD-SCID IL2Rgamma(null) humanized mice. Blood. 2011;117:3076–86. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-301507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Subramanian A, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:15545–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bell O, Tiwari VK, Thoma NH, Schubeler D. Determinants and dynamics of genome accessibility. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:554–64. doi: 10.1038/nrg3017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Altman R, Kellogg D. Control of mitotic events by Nap1 and the Gin4 kinase. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:119–30. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.1.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kellogg DR, Murray AW. NAP1 acts with Clb1 to perform mitotic functions and to suppress polar bud growth in budding yeast. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:675–85. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.3.675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Grande M, et al. Crosstalk between Nap1 protein and Cds1 checkpoint kinase to maintain chromatin integrity. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2008;1783:1595–604. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Biswas S, et al. Protocadherin-18b interacts with Nap1 to control motor axon growth and arborization in zebrafish. Molecular biology of the cell. 2014;25:633–42. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e13-08-0475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yokota Y, Ring C, Cheung R, Pevny L, Anton ES. Nap1-regulated neuronal cytoskeletal dynamics is essential for the final differentiation of neurons in cerebral cortex. Neuron. 2007;54:429–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhu Z, Bhat KM. The Drosophila Hem/Kette/Nap1 protein regulates asymmetric division of neural precursor cells by regulating localization of Inscuteable and Numb. Mechanisms of development. 2011;128:483–95. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gong H, et al. Knockdown of nucleosome assembly protein 1-like 1 induces mesoderm formation and cardiomyogenesis via notch signaling in murine-induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem cells. 2014;32:1759–73. doi: 10.1002/stem.1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rogner UC, Spyropoulos DD, Le Novere N, Changeux JP, Avner P. Control of neurulation by the nucleosome assembly protein-1-like 2. Nat Genet. 2000;25:431–5. doi: 10.1038/78124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lebert-Ghali CE, et al. Hoxa cluster genes determine the proliferative activity of adult mouse hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Blood. 2016;127:87–90. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-02-626390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Prelich G. Gene overexpression: uses, mechanisms, and interpretation. Genetics. 2012;190:841–54. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.136911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia. The New England journal of medicine. 2013;368:2059–74. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mizuno H, Kitada K, Nakai K, Sarai A. PrognoScan: a new database for meta-analysis of the prognostic value of genes. BMC medical genomics. 2009;2:18. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-2-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sadeghi B, et al. Xeno-immunosuppressive properties of human decidual stromal cells in mouse models of alloreactivity in vitro and in vivo. Cytotherapy. 2015;17:1732–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Eshtad S, et al. hMYH and hMTH1 cooperate for survival in mismatch repair defective T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Oncogenesis. 2016;5:e275. doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2016.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement