Abstract

Advances in breast cancer treatment have markedly increased survivorship over the past three decades, with over 3.1 million survivors expected to live into their 70s and 80s. Without symptom relief interventions, nearly 35% of these survivors will have life-altering and distressing cognitive symptoms. This pilot study explored associations between serum markers of vascular aging, laterality in cerebral oxygenation, and severity of cognitive impairment in women, 12–18 months after chemotherapy for stage 2/3 invasive ductal breast cancer. Fifteen women (52–84 years) underwent a brief cognitive assessment (Montreal Cognitive Assessment [MOCA]) and blood draws to assess markers of vascular aging (interleukin-6 [IL-6], tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α], C-reactive protein [CRP], and insulin growth factor-1 [IGF-1]). All underwent a computer-based test protocol that is known to increase blood flow within the frontal lobes. Percent cerebral oxyhemoglobin saturation (rcSO2) was recorded during and after testing. Laterality in rcSO2 was defined by ≥ 3% difference between left and right rcSO2 (|rcSO2 meanRIGHT – meanLEFT|). Eight participants had MOCA scores between 21 and 25 points, suggestive of mild cognitive impairment. Neither CRP (r = −.24) nor IL-6 (r = .34) nor TNF-α (r = .002) were associated with MOCA scores. Higher IL-6 was associated with greater laterality (r = .41). MOCA scores were significantly lower in subjects with laterality in rcSO2 than in those without laterality (F(1,14) = 13.5, p = 003). Lower IGF-1 was significantly associated with greater laterality (r = − .66, p = .007) and lower cognitive function (r = .58). These findings suggest that persistent cognitive impairment is associated with phenotypical changes consistent with accelerated vascular aging.

Keywords: Chemotherapy, Survivorship, Cerebral blood flow, Vascular aging, Cognitive symptoms

Introduction

More than one third of the 3.5 million breast cancer survivors experience life-altering cognitive impairments that can persist for decades after completing chemotherapy (Ahles et al. 2010; Koppelmans et al. 2012; Nguyen et al. 2013; Wefel et al. 2010). These symptoms are commonly described as events that temporarily disrupt the ability to accurately and efficiently process information, learn new tasks, plan, or make decisions (Myers 2012; Von Ah and Tallman 2015). The unpredictability of symptoms is often given as a reason to discontinue employment or even disengage in previous personal and social activities (Boykoff et al. 2009; Meeker et al. 2017). Functional MRI studies suggest that the persistence of symptoms for years following treatment is associated with regional alterations in blood flow and structure within the frontal lobes (Holohan et al. 2013; McDonald and Saykin 2013). The underlying pathological mechanisms, however, are unknown.

Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress are tightly linked to diseases associated with endothelial dysfunction (Ungvari et al. 2010), and the cerebral microcirculation is the source of, and a target for, inflammatory proteins (Csiszar et al. 2012; Irwan et al. 2009). During chemotherapy, a proinflammatory shift occurs in vascular gene expression profiles, including an upregulation of inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules, and inducible nitric oxide synthase (Janelsins et al. 2012). Plasma concentrations of several inflammatory markers (predominantly IL-1, IL-6, TNF, and C-reactive protein) rise during treatment and, in many, return to nearly normal levels within 1-year posttreatment (Lyon et al. 2016; Tsavaris et al. 2002). While trends in these inflammatory markers suggest an increase in inflammation and oxidative stress associated with treatment, reported (Lyon et al. 2016; Tsavaris et al. 2002) effect sizes between any given marker and function are relatively small (Pearson r of .2–.3), and the correlation between a specific factor and cognitive function is not seen at all treatment time points. Such findings suggest that there are additional mediating variables linking inflammation to cognitive function in breast cancer survivors.

A promising hypothesis is that chemotherapy induces an accelerated aging phenotype in the brain microvasculature that is characterized by alterations in regional cerebral blood flow. A number of commonly used, first-line chemotherapeutic agents, like paclitaxel and docetaxel, cause endothelial cell death at doses less than those needed to destroy cancer cells (Ahles and Saykin 2001). Others (Di Lisi et al. 2017; Soultati et al. 2012) interfere with endothelial cell function (doxorubicin and epirubicin) or alter vascular permeability and angiogenesis (cyclophosphamide and bevacizumab). In addition to limiting the availability of oxygen and vital nutrients to working cells, the declines in regional flow also impair the removal of toxic substances, which can evoke inflammatory-oxidative pathways that can accelerate damage to endothelial cells and allow easier passage of circulating factors that can damage neurons (Di Marco et al. 2015).

In addition to the lasting effects of chemotherapy on cerebral microvessels and the permeability of this barrier to inflammatory factors, the persistence of symptoms after treatment may also depend upon the depletion of factors that offset injuries due to neuroinflammation and oxidative stress. For example, a number of women undergo additional therapies aimed at preventing cancer reoccurrence (tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors) that disrupt estrogen pathways and limit estrogen production (Acaz-Fonseca et al. 2014; Christopoulos et al. 2015). Disruptions of these estrogen pathways can disrupt other factors, like insulin growth factor 1, that mitigate the damaging effects of inflammation and oxidative stress on endothelial cells and neurons (Cardona-Gomez et al. 2001). Thus, the persistence of symptoms years after treatment may depend upon both the restoration of both regional blood flow and factors important for restoring neural networks after injury.

The aim of this pilot project was to provide preliminary data for a more conclusive test of the mechanistic links between serum markers associated with vascular aging (C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and insulin growth factor) to alterations in cerebral blood flow, and persistent neurocognitive symptoms in breast cancer survivors, 12–18 months after active chemotherapy for breast cancer. We hypothesize that inflammation triggers damage to cerebral microvessels, which over time alters the vessels’ ability to regulate regional blood flow. Reflecting a major cause of vascular aging, we hypothesize that higher levels of inflammatory markers will be associated with greater laterality, as measured by percent cerebral oxyhemoglobin saturation (rcSO2). In contrast, lower IGF-1 levels, which are instrumental in cellular growth and repair, will not only be associated with greater laterality in rcSO2, but also with more severe cognitive symptoms.

Materials and methods

Participant recruitment

Fifteen women were recruited from a breast cancer clinic located in a major catchment center in Central Oklahoma. Participants were identified through weekly reviews of the electronic medical record. Their eligibility to participate was verified with a standardized telephone screen adapted from our prior studies.

Inclusion criteria included: postmenopausal, at least 50 years of age or older, normal hearing and vision, with or without visual correction (for the purpose of cognitive testing), and 12–18 months postchemotherapy for breast cancer. Exclusion criteria included a history of a neurological disorder (stroke, arteriovenous malformation, schizophrenia, bipolar affective disorder, seizure disorder, or substance abuse), diagnosis of heart failure (stage B or above), peripheral vascular disease (on anticoagulants, history of ischemia on walking short distances, and/or edema or history of phlebitis), a clotting disorder, or active autoimmune/inflammatory disorders affecting blood flow or oxygenation (i.e., sickle-cell, systemic lupus erythematosus, or chronic pulmonary disease). Persons with common disorders of aging or cancer (i.e., depression, anxiety, non-vascular peripheral neuropathy, and arthritis) were not excluded, but the condition was recorded and used in descriptive-exploratory analyses. Since brain activation patterns in response to verbal cues differ between native and bilingual English speakers, non-native English speakers were excluded. The institutional review board approved the study. All participants gave informed consent.

Participant procedure

All participants underwent a 1.5 h standardized protocol that included a blood draw followed by measurements of global cognitive function and a computer-based working memory test, with a 30-min rest-recovery period between the first and second recall periods.

Severity of cognitive symptoms was assessed with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA). The MOCA (Nasreddine et al. 2005) assesses a wide range of abilities: attention and concentration, executive functions, memory, language, visual-constructional skills, conceptual thinking, calculations, and orientation. It has excellent internal consistency (Cronbach alpha = 0.83) and test-retest reliability (r = .92, mean change 1 month apart of 0.9 points). Reported concurrent validity (Trzepacz et al. 2015) against the Mini-Mental State Examination in patients with mild cognitive impairment (n = 94), Alzheimer’s disease (n = 93), and cognitively intact, age-matched controls (n = 90) was excellent (r = 0.87). Cognitive impairment is defined by a score of < 26 points, which prior studies show yields acceptable specificity (87%) and sensitivity (78%) for detecting mild cognitive impairment (Tsoi et al. 2015).

Percent cerebral oxyhemoglobin was measured continuously from the right and left frontal areas of the brain and recorded every 4 s using the INVOS 5100c cerebral oximeter (Somanetics, Troy, MI). The INVOS 5100c, uses continuous-wave, near infrared spectroscopy to track trends in rcSO2 in the small blood vessels (primarily arterioles, capillaries, and venules) under the sensors. Since these small cerebral blood vessels account for approximately 70–75% of the cerebral vasculature, measures typically range from 50% in adults with impairment to 80% in young adults (Madsen and Secher 1999). The validity of cerebral oximetry as a means of evaluating changes in rcSO2 has been established under a number of experimental conditions, including measurement of jugular bulb venous oxygen saturation (Pollard et al. 1996), blood oxygen level with blood-oxygen-level-dependent contrast imaging (Mehagnoul-Schipper et al. 2002), and cerebral blood flow as measured using transcranial Doppler sonography (Hirth et al. 1997).

The sensors were placed on the forehead, approximately 1 cm to right and left of midline and monitored while participants completed a computerized version of the free cued selective reminding task (Wenger et al. 2010). The test consists of three parts. The first part is encoding. During encoding, subjects are seated in a recliner chair, facing the monitor, and search for and verbally identify a picture of a particular object to-be-remembered (e.g., “sweater”) among a set of pictures in response to a 32 categorical cue (e.g., “item of clothing”). Following presentation of the entire set of to-be-remembered items, they were given 3 min to freely recall (FR) as many items as possible. Encoding ends after retrieval cues (e.g., the category labels that were used to guide initial encoding) are provided for words that were not recalled. Participants were asked to identify the missed items from the cues (Cued Recall (CR)). After encoding, participants were asked to close their eyes and rest for 30 min, yet remain awake (rest-recovery). In the third and last part of the test (delayed memory recall), participants were asked to recall as many items from the to-be-remembered list and the missed items list as they could, and to recall items with the assistance of retrieval cues (delayed recall).

Electroencephalogram recordings verified that all participants remained awake throughout the encoding, rest-recovery, and delayed recall periods. Percent arterial oxyhemoglobin (SaO2) was measured every 0.33 s using a Nellcor pulse oximeter (Mallinckrodt Inc., St. Louis, MO) placed on the middle finger of the person’s non-dominant hand to verify the absence of desaturations (SaO2 > 94% or a decline in SaO2 > 4%) during testing.

The means of right and left rcSO2 were calculated for each one-minute epoch during testing and during the rest-recovery period. Laterality in rcSO2 was determined during testing (encoding, rest-recovery, and delayed recall) by calculating, for each epoch, the average absolute difference in 1-min means (|rcSO2 meanRight − meanLeft|). Error in rcSO2 measurements is reported to range between − 1 and + 1%. Thus, we conservatively defined significant laterality in frontal measures as an absolute difference ≥ 3%. The aim of this study was to examine associations between laterality and cognition. Thus, classification of laterality was done during encoding. Laterality was also examined during the rest-recovery and delayed recall periods in order to characterize how laterality changes during rest-recovery and resumption of the memory task (delayed recall).

Serum markers of vascular aging

Blood was drawn from the antecubital fossa into a red-topped vacutainer tube by a certified phlebotomist, with the participant reclining for at least 10 min. The blood was allowed to clot and serum was separated by centrifugation within 20 min of being drawn. Serum was divided into 0.5-mL aliquots and stored at − 80 °C. After the study was closed to patient enrollment, serum was analyzed in single batches for each cytokine. Serum Interleukin 6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and C-reactive protein (CRP) were assayed in duplicate using high sensitivity immunoassay kits according to manufacturer’s instructions (Quantikine HS ELISA, Minneapolis, MN). Insulin growth factor-1 (IGF-1) was also assayed from serum using a commercially available ELISA kit (R&D, Minneapolis, MN). Average intraassay coefficients of variation were 7.0% for CRP (median 5.3%, range 0.02–20.5%) and 6.1% for IGF-1 (median 4.5%, range 0.05–18.5%); the average of all 15 duplicates were used in the analysis. Intraassay coefficient of variation of two IL-6 and four TNF-α assay duplicates were > 25%; data from these subjects were excluded from the analysis. With the discrepant duplicates removed, intraassay coefficient of variation fell to an average of 8% for IL-6 (median 8.7%, range 0.1–16.8%) and 10% for TNF-α (median 10.6%, range 1.0–17.9%).

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Prior to each analysis, the data was examined for possible outliers (greater than 3.0 standard deviations). When outliers were found, the analysis was performed with and without the suspected outlier. In the case of discrepancies between these parallel analyses, we reported the results without outliers. Since the study is a small sample exploratory study in an undeveloped area of inquiry, hypothesis generation was favored over strict control of type I error, and corrections for multiple tests were not used. Statistical significance was set at p < .05.

Results

Sample characteristics

One hundred twelve women, 12–18 months from active treatment and 50 years of age and older, were identified from electronic medical records. Sixty-four were deemed eligible to participate. Fifteen were approached and recruited, all of whom completed the study protocol. Data collection occurred between January 2015 and December 2015.

The resulting predominantly Caucasian (n = 13) sample (Table 1) ranged in age from 52 to 84 years (median 62.5 years). All had completed high school. About one half held a baccalaureate degree and two completed a master’s degree. Seven were employed full time. Of the eight retirees studied, three were between the ages of 50 and 65 years.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics by laterality in cerebral oxygenation

| All | Laterality | No laterality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 15 | 8 | 7 |

| Sociodemographics | |||

| Age (M | 64.4 ± 12.3 | 64.5 ± 8.4 | 64.1 ± 11.9 |

| Caucasian (f) | 13 | 7 | 6 |

| # Post-secondary education | 7 | 4 | 3 |

| Employment | |||

| # Unemployed | 0 | – | – |

| # Employed | 7 | 3 | 4 |

| # Retired | 8 | 5 | 3 |

| Cancer-related variables | |||

| Cancer stage | |||

| Stage I | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Stage II | 8 | 3 | 5 |

| Stage III | 6 | 4 | 2 |

| Treatment regimen | |||

| Surgery | 12 | 6 | 6 |

| Radiation | 11 | 5 | 6 |

| Hormones | 10 | 5 | 5 |

| Cardiovascular health | |||

| Body mass index | 28.1 ± 4.7 | 29.5 ± 5.3 | 26.5 ± 3.5 |

| # Hypertension | 11 | 7 | 4 |

| # Hyperlipidemia | 10 | 8 | 2 |

| # Sleep apnea | 5 | 3 | 2 |

The majority of participants had either stage 2 or stage 3 invasive ductal carcinoma. All had undergone chemotherapy and surgery; eight were taking aromatase inhibitors. Review of their most recent clinic visit verified that all had serum hemoglobin levels above 12.0 g/dL. Depressive symptoms were minimal; all had a score of < 5 on the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale. Eleven were treated for hypertension and hypercholesterolemia. None were diagnosed with diabetes. Body mass indices ranged from 21.5 to 35.9 Kg/M2. At the time of the study, all were normotensive (systolic < 140 mmHg), had normal body temperatures (36.5–37.5 °C), had no symptoms of flu or cold, and arterial oxyhemoglobin levels of 94% or greater. All were at least 6 months from surgery or procedures requiring general anesthesia.

Neither age nor treatment regimen appear to distinguish participants with laterality in rcSO2 from those without laterality in rcSO2. More than one-half of both groups attained degrees beyond high school. Slightly more participants with laterality were retired. Half of those with laterality were diagnosed with Stage III breast cancer, as compared with approximately a third without laterality. Although not statistically significant, participants with laterality in rcSO2 tended to have more cardiac comorbidities (higher body mass index, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia) than participants without laterality. Based on self-report, diagnosis of sleep apnea did not distinguish participants with and without laterality in rcSO2.

Post hoc review of their most recent posttreatment body scans provided further data to assess the extent of cardiovascular pathology in ten subjects. These ten included subjects with the highest and lowest MOCA scores and the lowest and greatest laterality in cerebral oxygenation. Review of their T1 and T2 MRI verified the absence of stroke, brain tumor, or significant white matter disease (≤ 2 out of a possible 4 points on the Age Related White Matter Scale [ARWMC] scale) (Wahlund et al. 2001). The oldest subject, at 84 years of age, had mild generalized cortical atrophy on MRI. Cardiac ultrasounds were unremarkable. All had normal ejection fractions (51–68%). One subject (age 60 years) had an ejection fraction with lower range of normal (EF < 51%). Review of the subject’s chest/abdominal scans revealed mild-moderate calcification of the coronary arteries. Calcification of the vessels was minimal in the remaining nine subjects.

Laterality in cerebral oxygenation

Representative plots showing trends in right and left rcSO2 values in participants with and without laterality in rcSO2 are shown in Fig. 1. In both groups, values declined upon initial presentation of the “to-be-remembered” items (encoding) and increased during free and cued recall. In both groups, left- and right-sided values trended in the same direction. During rest-recovery, rcSO2 remained unchanged in those without laterality. In six of the eight subjects with laterality during testing, the magnitude of laterality declined within the first 15 minutes of rest. With delayed recall of to-be-remembered items, both groups exhibited similar fluctuations in rcSO2 as seen during encoding and initial FR and CR. In those who exhibited laterality during encoding, laterality reoccurred during delayed recall. None of the seven participants without laterality during encoding exhibited laterality during delayed recall.

Fig. 1.

Representative plots of trends in right- and left-sided rcSO2 in participants without (a) and with (b) laterality in rcSO2. Note with laterality, the side with the lowest rcSO2 remains the same across time and test conditions. The consistency in sidedness and the restoration of laterality with cognitive testing (encoding and recall) was seen in all eight participants with laterality in rcSO2

Relationship between laterality in cerebral oxygenation and markers of vascular aging

Table 2 shows the distribution of serum proinflammatory markers and IGF-1 values in persons with and without laterality in rcSO2. None of the vascular aging markers differentiated participants with and without laterality, but the findings suggest a link between vascular inflammation and laterality. Seven subjects had serum CRP levels above 3 mg/dL, which is considered at high risk for cardiovascular disease (Yeh 2005). Six of these women also showed laterality in rcSO2. Consistent with the susceptibility of the cerebral blood vessels to chronic exposure to inflammatory factors, greater laterality in rcSO2 tended to be associated with higher serum levels of IL-6 (r = .41, p = .10), but not CRP (r = .36), nor TNFα (r = .22). In contrast, greater laterality in rcSO2 was significantly associated with lower IGF-1 (r = − .55, p = .05). As with laterality, lower serum IGF-1 was also significantly associated with higher serum IL-6 (r = − .60, p = .01).

Table 2.

Distribution of vascular aging markers by laterality in cerebral oxygenation (rcSO2)

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | TNF-α (pg/mL) | CRP (mg/L) | IGF-1 (ng/mL) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All subjects | ||||

| n | 14 | 11 | 15 | 15 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.3 (1.0) | 1.2 (0.5) | 3.2 (2.8) | 98.1 (36.5) |

| Median (range) | 1.2 (0.1–4.1) | 0.9 (0.6–2.2) | 1.9 (0.3–9.9) | 110.0 (5.2–136.4) |

| Laterality | ||||

| n | 7 | 5 | 8 | 8 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.4 (1.2) | 1.0 (0.7) | 3.9 (3.4) | 74.0 (48.0) |

| Median (range) | 1.1 (0.4–4.1) | 0.9 (0.6–2.1) | 1.8 (0.3–4.1) | 90.3 (5.2–131.7) |

| No laterality | ||||

| n | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.1 (0.7) | 1.2 (0.5) | 2.5 (2.0) | 115.1 (20.4) |

| Median (range) | 1.3 (0.1–1.8) | 1.1 (0.6–1.9) | 1.9 (0.3–5.0) | 116.2 (74.5–136.4) |

| Association with laterality | ||||

| Spearman rho | 0.41 | 0.22 | 0.36 | − 0.55 |

Laterality: absolute difference in right and left frontal rcSO2, formula: (|rcSO2right-rcSO2left |)

IL-6 interleukin-6, TNF-α tumor necrosis factor alpha, CRP C-reactive protein, IGF-1 insulin growth factor 1

Vascular aging, laterality in cerebral oxygenation, and severity of cognitive impairment

Scores on the MOCA ranged from 21 to 29 points. Eight participants had MOCA scores between 21 and 25 points. All participants reported normal everyday function as defined by an Older Adults Resource Services Activity of Daily Living Scale score of 26 or higher and a 15-Geriatric Depression Scale Score of > 5 points, which meets Petersen’s criteria for mild cognitive impairment (Petersen et al. 2014).

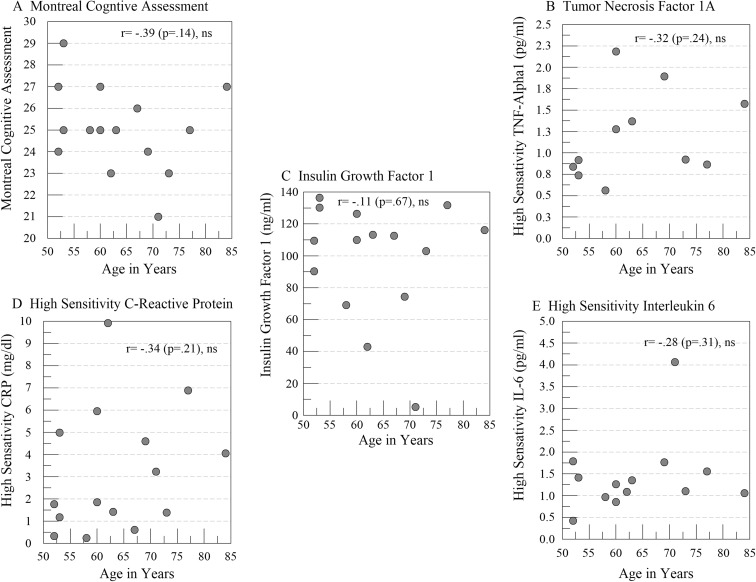

On average, CRP levels were almost 2-fold higher in participants with cognitive impairment (3.2 ± 0.7 versus 1.7 ± 1.7 mg/L), but neither CRP (− .24) nor IL-6 (r = − .34) nor TNFα (r = .002) were associated with MOCA scores. Rather, lower MOCA scores were associated with lower IGF-1 (r = .66, p = .007) and greater laterality in rcSO2 (r = .58, p < .02). Unlike what we typically see with vascular aging, age was not associated with lower MOCA scores or higher values on any of the inflammatory markers (Fig. 2). Although associated with lower scores on the MOCA and greater laterality, age was not associated with serum IGF-1 levels.

Fig. 2.

Scatter plots showing the relationships and correlation coefficients between age in years and a total scores on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment Test, as well as serum measurement of b tumor necrosis factor, c insulin growth factor 1, d high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, and e high-sensitivity interleukin-6

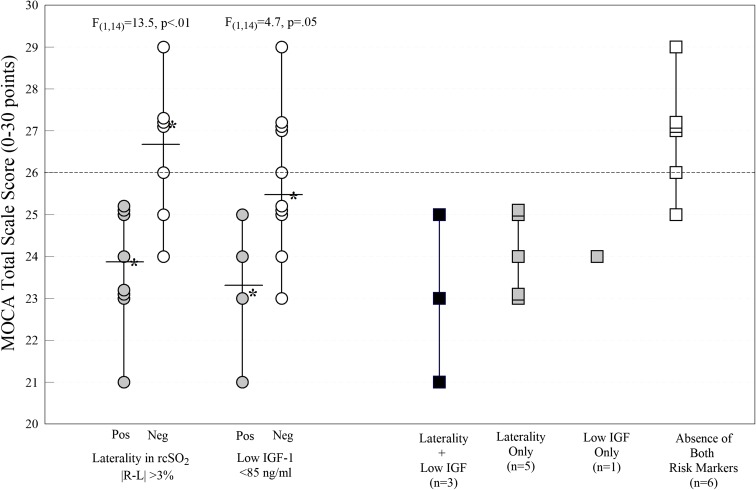

Compared with those without laterality in rcSO2 (Fig. 3), MOCA scores were significantly lower in subjects with laterality (F(1,14) = 13.5, p = .003). The dotted line in Fig. 3 marks the MOCA cutpoint score for mild cognitive impairment. All eight participants with laterality, but only two of the seven without laterality, met criteria for mild impairment. Four subjects with cognitive impairment had IGF-1 levels less than 85 ng/mL, which is considered a risk factor for vascular dysfunction and cognitive impairment (Falleti et al. 2006). Participants with serum IGF-1 values < 85 ng/mL had significantly greater cognitive impairment (F(1,14) = 4.7, p = .05) than did participants with higher IGF-1 values. The far right of Fig. 3 (squares) further illustrates the interactive effects of laterality and IGF-1 levels on cognitive function. Three of eight participants with laterality had low serum IGF-1. Only one subject without laterality had low IGF-1. Of the six participants without laterality or low IGF-1 levels, only one scored below 26 points on the MOCA.

Fig. 3.

Differences in total scores on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment Scale (MOCA) in participants with laterality and serum insulin growth factor 1 (IGF-1) < 85 ng/dL. Each filled symbol (circles and squares) marks participants with the positive predictive marker. The open symbols mark participants without the marker. Solid line marks the group mean. Stars indicate the median for each group. The dotted horizontal line extending from the X-axis indicates the clinical cutpoint for mild cognitive impairment, as measured by the MOCA

Discussion

This study supports our developing concept that persistent cognitive symptoms 12–18 months after chemotherapy for breast cancer are the net effect of cumulative exposures to proinflammatory factors that disrupt the structural integrity and function of cerebral microvascular endothelial cells (CMVECs). The lasting impact of this damage to CMVECs is the loss of vascular support for cognitive processing. Whereas prior studies demonstrate significant association between systemic inflammation and cognitive function, our findings suggest that laterality in mixed venous cerebral oxygenation (rcSO2) may be a prognostic marker of persistent cognitive impairment associated with the loss of vascular support for cognitive processing.

Cerebral oximetry, as well as technologies derived from it, such as functional near infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), are valid methods for assessing disruptions in cerebral blood flow both at rest and during cognitive challenge. When monitored during a task that requires the person to pay attention and respond based on the stimuli presented, the rise in regional oxyhemoglobin levels correlates with the overshoot of cerebral blood flow brought on by the brain activation associated with mental processing (Zhang et al. 2005). In general, reported rcSO2 ranged from 60 to 80%. Differences between right-to-left sided measures are typically no more than 1–2% in healthy adults. Laterality in rcSO2 (one side higher than the other) of 3% or more has been reported in cases of carotid disease (Jonsson et al. 2017; Mason et al. 1994) and surgery-induced cerebral ischemia (Calderon-Arnulphi et al. 2007). In those without significant carotid disease, laterality in cerebral oxygenation is also present in patients undergoing stellate ganglion block for migraines (Park et al. 2010), which suggest that suggesting laterality can also reflect disruptions in adrenergic modulation of regional blood flow.

In this study, rcSO2 rose during cognitive testing and fell during periods of quiet wakefulness, regardless of whether it was recorded at the right or left side of the brain. Our findings further suggest difference in right and left-sided rcSO2 measures is most profoundly seen during testing and will decline with periods of extended rest (15–20 min). The reliability of this characteristic of rcSO2 during testing and its association with cognitive impairment suggest that greater laterality in cerebral oxygenation may point to relevant disruptions in neurovascular coupling. While laterality has also been reported in persons with local microinfarcts or misery perfusion (White et al. 2016), laterality in this sample occurred in persons with minimal cardiac and cerebrovascular pathology. This finding further supports the idea that laterality may also reflect disruptions in neurovascular coupling.

Proinflammatory factors that become attached to endothelial cells within the cerebral microcirculation are probably a trigger that ultimately results in these longer term disruptions in neurovascular coupling. It is well known that the endothelial cells, that line the cerebral microvasculature, is both the source of, and a target for, inflammatory proteins. In general, the characteristics of the pretreatment phase of breast cancer resemble a state of arrested vascular aging. Pre-treatment levels of proinflammatory markers are markedly less than those of age-matched controls (Lyon et al. 2016; Tsavaris et al. 2002). Tumors may produce growth factors, such as VEGF and IGF, to promote cancer cell proliferation (Christopoulos et al. 2015; Hawsawi et al. 2013). Most studies report increased pretreatment levels of proinflammatory markers (predominantly IL-1, IL-6, TNF, and C-reactive protein) that return to nearly normal levels within 1-year posttreatment (Lyon et al. 2016; Starkweather et al. 2017; Tsavaris et al. 2002). Consistent with this earlier research, we found that greater laterality in rcSO2 was associated with all three markers of systemic inflammation (CRP, IL-6, and TNF-α). In the present study, these markers were not associated with age, which further suggest that laterality may be an important marker that links the exposure of proinflammatory factors to cognition. The identification of these proinflammatory factors, their association with cancer or its treatment, and the mechanism that leads to laterality of rcSO2 are certainly important areas for future investigations.

Lower IGF-1 was associated with laterality in rcSO2 and cognitive impairment, but not age, suggesting that a lower ability to repair damage cells contributes to the development of vascular aging and cognitive impairment. Several preclinical studies suggest that deficiencies in IGF-1 promote alteration in cerebral autoregulation and disrupt vessel wall integrity (Tarantini et al. 2017; Toth et al. 2014, 2015). Alternatively, IGF-1 plays an important role in cellular growth and repair. Thus, lower IGF-1 may reflect significant depletion of this neuroprotective factor. Clearly, IGF-1, which plays a role in vascular health, brain development, maturation, and neuroplasticity (Dyer et al. 2016), is an important mediator of cognitive impairment. In this small sample, the absence of laterality and higher serum IGF-1 characterized those with normal MOCA scores. All 8 subjects with laterality had MOCA scores in the impaired range (< 26 points). Impaired performance was also seen in all four subjects with low serum IGF-1. All but one of the subjects with low IGF-1 had concurrent laterality in cerebral oxygenation. The Further study is clearly needed to understand how these two markers act to influence cognition.

While we cannot draw conclusions about causal effects of laterality in rcSO2 and low serum IGF-1 on cognitive function, our findings of associations between biomarkers of vascular function with measures of cognitive function open the door for further study. Clearly, investigating how oxidative stress and inflammation relate to laterality in neurovascular coupling and cerebral oxygen levels are important areas for future study. If laterality follows the restoration of cytokines in the posttreatment period, then laterality may be an important clinical biomarker of advanced vascular aging. IGF has also been known to induce inflammatory responses in endothelial cells (Che et al. 2002). Thus, the relationships between IGF-1 levels, laterality, and cognitive function may change over the course of treatment and recovery. The fact that proinflammatory cytokines are associated with laterality in rcSO2 suggests that one could institute interventions in the postchemotherapy period that would support endothelial function and enhance cerebral blood flow by counteracting the over activation of inflammatory or oxidative pathways (dietary modifications or antioxidants), or improving vascular function (e.g., dietary supplementation or exercise). Since many long-term treatments for breast cancer target estrogen pathways and limit IGF-1 production, it may not be desirable to increase IGF-1, but it may be possible to use this marker to identify persons who should receive aggressive treatment to minimize vascular dysfunction.

One limitation is the lack of pretreatment assessment of cognitive functioning. Although detected at 12–18 months posttreatment, it is possible that the lower scores on the MOCA reflect a persistent pretreatment deficit. Likewise, the lack of pretreatment assessment will not differentiate between participants who may have scored above normal before treatment and then scored in the normal range after treatment, incorrectly implying that those patients were unaffected by the chemotherapy. Given that 17% of breast patient survivors have some form of cardiovascular disease (Al-Kindi and Oliveira 2016), it is likely that larger samples could include more persons with occult cardiovascular disease. Thus, more extensive vascular assessments (i.e., carotid Doppler, T1/T2 imaging, echocardiograms) should be done to differentiate lateralities secondary to ischemia (low resting flow, stroke, misery perfusion, carotid disease) from regional disruption in neurovascular coupling. A critical next step in this area is the use of prospective, longitudinal designs in which patients are evaluated before treatment and followed over time after treatment. Lastly, this study did not allow analysis of potential interactive effects of treatements with normal aging processes. An age-matched control group who have not received chemotherapy would be important in making these distinctions and should be considered once these study findings are replicated in a more representative sample of breast cancer survivors.

Conclusion

Until therapeutic agents that specifically target cancer cells without harming vasculature become standard of care, survivors must undergo therapies that disrupt the viability of endothelial cells and allow proinflammatory factors to potentially adhere to or even cross the blood-brain barrier. For now, the best approach is to develop interventions that lessen posttreatment damage or that identify at-risk individuals early so that interventions can be implemented. These interventions could be designed to prevent damage resulting from inflammation/oxidative stress or to promote the repair to damage cells. The findings from this pilot study suggest that alterations in cerebral blood flow, as indicated by laterality in rcSO2, may mark persons with impending vascular damage who may benefit from interventions aimed at lessening oxidative stress and lessening the severity of cognitive impairment following chemotherapy.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by a grant from the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation to MAC. We also wish to thank Elangovan Thavathiru, Ph.D. for the processing and analyses of the samples.

Contributor Information

Barbara W. Carlson, Phone: 919-225-4214, Email: Barbara-Carlson@ouhsc.edu

Melissa A. Craft, Email: Melissa-Craft@ouhsc.edu

John R. Carlson, Email: jcarlson2000-mail@yahoo.com

Wajeeha Razaq, Email: Wajeeha-Razaq@ouhsc.edu.

Kelley K. Deardeuff, Email: Kelley-Deardeuff@ouhsc.edu

Doris M. Benbrook, Email: Doris-Benbrook@ouhsc.edu

References

- Acaz-Fonseca E, Sanchez-Gonzalez R, Azcoitia I, Arevalo MA, Garcia-Segura LM. Role of astrocytes in the neuroprotective actions of 17beta-estradiol and selective estrogen receptor modulators. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014;389:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahles TA, Saykin A. Cognitive effects of standard-dose chemotherapy in patients with cancer. Cancer Investig. 2001;19:812–820. doi: 10.1081/CNV-100107743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahles TA, Saykin AJ, McDonald BC, Li Y, Furstenberg CT, Hanscom BS, Mulrooney TJ, Schwartz GN, Kaufman PA. Longitudinal assessment of cognitive changes associated with adjuvant treatment for breast cancer: impact of age and cognitive reserve. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4434–4440. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.0827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Kindi SG, Oliveira GH. Prevalence of preexisting cardiovascualr disease in patiehts with different types of cancer: the unmet need for onco-cardiology. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:81–83. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boykoff N, Moieni M, Subramanian SK. Confronting chemobrain: an in-depth look at survivors' reports of impact on work, social networks, and health care response. J Cancer Surviv. 2009;3:223–232. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0098-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calderon-Arnulphi M, Alaraj A, Amin-Hanjani S, Mantulin WW, Polzonetti CM, Gratton E, Charbel FT. Detection of cerebral ischemia in neurovascular surgery using quantitative frequency-domain near-infrared spectroscopy. J Neurosurg. 2007;106:283–290. doi: 10.3171/jns.2007.106.2.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardona-Gomez GP, Mendez P, DonCarlos LL, Azcoitia I, Garcia-Segura LM. Interactions of estrogens and insulin-like growth factor-I in the brain: implications for neuroprotection. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2001;37:320–334. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0173(01)00137-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che W, Lerner-Marmarosh N, Huang Q, Osawa M, Ohta S, Yoshizumi M, Glassman M, Lee JD, Yan C, Berk BC, Abe J. Insulin-like growth factor-1 enhances inflammatory responses in endothelial cells: role of Gab1 and MEKK3 in TNF-alpha-induced c-Jun and NF-kappaB activation and adhesion molecule expression. Circ Res. 2002;90:1222–1230. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000021127.83364.7D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopoulos PF, Msaouel P, Koutsilieris M. The role of the insulin-like growth factor-1 system in breast cancer. Mol Cancer. 2015;14:43. doi: 10.1186/s12943-015-0291-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csiszar A, Sosnowska D, Wang M, Lakatta EG, Sonntag WE, Ungvari Z. Age-associated proinflammatory secretory phenotype in vascular smooth muscle cells from the non-human primate Macaca mulatta: reversal by resveratrol treatment. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67:811–820. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lisi D, et al. Anticancer therapy-induced vascular toxicity: VEGF inhibition and beyond. Int J Cardiol. 2017;227:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.11.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marco LY, Farkas E, Martin C, Venneri A, Frangi AF. Is Vasomotion in cerebral arteries impaired in Alzheimer’s disease? J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;46:35–53. doi: 10.3233/JAD-142976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer AH, Vahdatpour C, Sanfeliu A, Tropea D. The role of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) in brain development, maturation and neuroplasticity. Neuroscience. 2016;325:89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falleti MG, Maruff P, Burman P, Harris A. The effects of growth hormone (GH) deficiency and GH replacement on cognitive performance in adults: a meta-analysis of the current literature. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:681–691. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawsawi Y, El-Gendy R, Twelves C, Speirs V, Beattie J. Insulin-like growth factor - oestradiol crosstalk and mammary gland tumourigenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1836:345–353. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirth C, Obrig H, Valdueza J, Dirnagl U, Villringer A. Simultaneous assessment of cerebral oxygenation and hemodynamics during a motor task. A combined near infrared and transcranial Doppler sonography study. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1997;411:461–469. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5865-1_59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holohan KN, Von Ah D, McDonald BC, Saykin AJ. Neuroimaging, cancer, and cognition: state of the knowledge. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2013;29:280–287. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwan YY, Feng Y, Gach HM, Symanowski JT, McGregor JR, Veni G, Schabel M, Samlowski WE. Quantitative analysis of cytokine-induced vascular toxicity and vascular leak in the mouse brain. J Immunol Methods. 2009;349:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janelsins MC, Mustian KM, Palesh OG, Mohile SG, Peppone LJ, Sprod LK, Heckler CE, Roscoe JA, Katz AW, Williams JP, Morrow GR. Differential expression of cytokines in breast cancer patients receiving different chemotherapies: implications for cognitive impairment research. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:831–839. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1158-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson M, Lindstrom D, Wanhainen A, Djavani Gidlund K, Gillgren P. Near infrared spectroscopy as a predictor for shunt requirement during carotid endarterectomy. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2017;53:783–791. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2017.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppelmans V, Breteler MM, Boogerd W, Seynaeve C, Gundy C, Schagen SB. Neuropsychological performance in survivors of breast cancer more than 20 years after adjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1080–1086. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.0189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon DE, Cohen R, Chen H, Kelly DL, McCain NL, Starkweather A, Ahn H, Sturgill J, Jackson-Cook CK. Relationship of systemic cytokine concentrations to cognitive function over two years in women with early stage breast cancer. J Neuroimmunol. 2016;301:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen PL, Secher NH. Near-infrared oximetry of the brain. Prog Neurobiol. 1999;58:541–560. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0082(98)00093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason PF, Dyson EH, Sellars V, Beard JD. The assessment of cerebral oxygenation during carotid endarterectomy utilising near infrared spectroscopy. Eur J Vasc Surg. 1994;8:590–594. doi: 10.1016/S0950-821X(05)80596-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald BC, Saykin AJ. Alterations in brain structure related to breast cancer and its treatment: chemotherapy and other considerations. Brain Imaging Behav. 2013;7:374–387. doi: 10.1007/s11682-013-9256-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeker CR, Wong YN, Egleston BL, Hall MJ, Plimack ER, Martin LP, von Mehren M, Lewis BR, Geynisman DM. Distress and financial distress in adults with cancer: an age-based analysis. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2017;15:1224–1233. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehagnoul-Schipper DJ, van der Kallen BFW, Colier WNJM, van der Sluijs MC, van Erning LJTO, Thijssen HOM, Oeseburg B, Hoefnagels WHL, Jansen RWMM. Simultaneous measurements of cerebral oxygenation changes during brain activation by near-infrared spectroscopy and functional magnetic resonance imaging in healthy young and elderly subjects. Hum Brain Mapp. 2002;16:14–23. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers JS. Chemotherapy-related cognitive impairment: the breast cancer experience. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2012;39:E31–E40. doi: 10.1188/12.ONF.E31-E40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian Vé, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, Cummings JL, Chertkow H. The Montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen CM, Yamada TH, Beglinger LJ, Cavanaugh JE, Denburg NL, Schultz SK. Cognitive features 10 or more years after successful breast cancer survival: comparisons across types of cancer interventions. Psychooncology. 2013;22:862–868. doi: 10.1002/pon.3086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HM, Kim TW, Choi HG, Yoon KB, Yoon DM. The change in regional cerebral oxygen saturation after stellate ganglion block. Korean J Pain. 2010;23:142–146. doi: 10.3344/kjp.2010.23.2.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC, Caracciolo B, Brayne C, Gauthier S, Jelic V, Fratiglioni L. Mild cognitive impairment: a concept in evolution. J Intern Med. 2014;275:214–228. doi: 10.1111/joim.12190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard V, Prough DS, DeMelo AE, Deyo DJ, Uchida T, Stoddart HF. Validation in volunteers of a near-infrared spectroscope for monitoring brain oxygenation in vivo. Anesth Analg. 1996;82:269–277. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199602000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soultati A, Mountzios G, Avgerinou C, Papaxoinis G, Pectasides D, Dimopoulos MA, Papadimitriou C. Endothelial vascular toxicity from chemotherapeutic agents: preclinical evidence and clinical implications. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38:473–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkweather A, Kelly DL, Thacker L, Wright ML, Jackson-Cook CK, Lyon DE. Relationships among psychoneurological symptoms and levels of C-reactive protein over 2 years in women with early-stage breast cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:167–176. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3400-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarantini S, Valcarcel-Ares NM, Yabluchanskiy A, Springo Z, Fulop GA, Ashpole N, Gautam T, Giles CB, Wren JD, Sonntag WE, Csiszar A, Ungvari Z. Insulin-like growth factor 1 deficiency exacerbates hypertension-induced cerebral microhemorrhages in mice, mimicking the aging phenotype. Aging Cell. 2017;16:469–479. doi: 10.1111/acel.12583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth P, Tucsek Z, Tarantini S, Sosnowska D, Gautam T, Mitschelen M, Koller A, Sonntag WE, Csiszar A, Ungvari Z. IGF-1 deficiency impairs cerebral myogenic autoregulation in hypertensive mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34:1887–1897. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth P, Tarantini S, Ashpole NM, Tucsek Z, Milne GL, Valcarcel-Ares NM, Menyhart A, Farkas E, Sonntag WE, Csiszar A, Ungvari Z. IGF-1 deficiency impairs neurovascular coupling in mice: implications for cerebromicrovascular aging. Aging Cell. 2015;14:1034–1044. doi: 10.1111/acel.12372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trzepacz PT, Hochstetler H, Wang S, Walker B, Saykin AJ, et al. Relationship between the Montreal Cognitive Assessment and Mini-mental State Examination for assessment of mild cognitive impairment in older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:107. doi: 10.1186/s12877-015-0103-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsavaris N, Kosmas C, Vadiaka M, Kanelopoulos P, Boulamatsis D. Immune changes in patients with advanced breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy with taxanes. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:21–27. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsoi KK, Chan JY, Hirai HW, Wong SY, Kwok TC. Cognitive tests to detect dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1450–1458. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungvari Z, Kaley G, de Cabo R, Sonntag WE, Csiszar A. Mechanisms of vascular aging: new perspectives. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65:1028–1041. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Ah D, Tallman EF. Perceived cognitive function in breast cancer survivors: evaluating relationships with objective cognitive performance and other symptoms using the functional assessment of cancer therapy-cognitive function instrument. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2015;49:697–706. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlund LO, Barkhof F, Fazekas F, Bronge L, Augustin M, Sjogren M, et al. A new rating scale for age-related white matter changes applicable to MRI and CT. Stroke. 2001;32:1318–1322. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.32.6.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wefel JS, Saleeba AK, Buzdar AU, Meyers CA. Acute and late onset cognitive dysfunction associated with chemotherapy in women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2010;116:3348–3356. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger MK, Negash S, Petersen RC, Petersen L. Modeling and estimating recall processing capacity: sensitivity and diagnostic utility in application to mild cognitive impairment. J Math Psychol. 2010;54:73–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jmp.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White LR, Edland SD, Hemmy LS, Montine KS, Zarow C, Sonnen JA, Uyehara-Lock JH, Gelber RP, Ross GW, Petrovitch H, Masaki KH, Lim KO, Launer LJ, Montine TJ. Neuropathologic comorbidity and cognitive impairment in the Nun and Honolulu-Asia Aging Studies. Neurology. 2016;86(11):1000–1008. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh ET. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein as a risk assessment tool for cardiovascular disease. Clin Cardiol. 2005;28:408–412. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960280905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Toronov VY, Fabiani M, Gratton G, Webb AG. The study of cerebral hemodynamic and neuronal response to visual stimulation using simultaneous NIR optical tomography and BOLD fMRI in humans. Proc SPIE Int Soc Opt Eng. 2005;5686:566–572. doi: 10.1117/12.593435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]