Abstract

Background

The value of fractional excretion (FE) of electrolytes to characterize and prognosticate acute kidney injury (AKI) is poorly documented in dogs.

Objectives

To evaluate the diagnostic and prognostic roles of FE of electrolytes in dogs with AKI.

Animals

Dogs (n = 135) with AKI treated with standard care (February 2014‐December 2016).

Methods

Prospective study. Clinical and laboratory variables including FE of electrolytes, were measured upon admission. Dogs were graded according to the AKI‐IRIS guidelines and grouped according to AKI features (volume‐responsive, VR‐AKI; intrinsic, I‐AKI) and outcome (survivors/non‐survivors). Group comparison and regression analyses with hazard ratios (HR) evaluation for I‐AKI and mortality were performed. P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Fifty‐two of 135 (39%) dogs had VR‐AKI, 69/135 (51%) I‐AKI and 14/135 (10%) were unclassified. I‐AKI dogs had significantly higher FE of electrolytes, for example, FE of sodium (FENa, %) 2.39 (range 0.04‐75.81) than VR‐AKI ones 0.24 (range 0.01‐2.21; P < .001). Overall, case fatality was 41% (55/135). Increased FE of electrolytes were detected in nonsurvivors, for example, FENa 1.60 (range 0.03‐75.81) compared with survivors 0.60 (range 0.01‐50.45; P = .004). Several risk factors for death were identified, including AKI‐IRIS grade (HR = 1.39, P = .002), FE of electrolytes, for example, FENa (HR = 1.03, P < .001), and urinary output (HR = 5.06, P < .001).

Conclusions and Clinical Importance

Fractional excretion of electrolytes performed well in the early differentiation between VR‐AKI and I‐AKI, were related to outcome, and could be useful tools to manage AKI dogs in clinical practice.

Keywords: AKI grade, natriuresis, tubular damage, urine chemistry, urine output

Abbreviations

- AKI

acute kidney injury

- AUC

area under the curve

- BE

base excess

- CI

confidence interval

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- CRP

C‐reactive protein

- FE

fractional excretion

- FECa

fractional excretion of calcium

- FECl

fractional excretion of chloride

- FEK

fractional excretion of potassium

- FEMg

fractional excretion of magnesium

- FENa

fractional excretion of sodium

- FEP

fractional excretion of phosphorus

- FEurea

fractional excretion of urea

- GFR

glomerular filtration rate

- HR

hazard ratio

- iCa

ionized calcium

- ICU

intensive care unit

- NA

not applicable

- ROC

receiver operator characteristic

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

- sCr

serum creatinine

- SD

standard deviation

- UAC

urine albumin to creatinine ratio

- uCr

urine creatinine

- uCr/sCr

urine creatinine to serum creatinine ratio

- uGlucose/uCr

urine glucose to creatinine ratio

- UO

urine output

- UPC

urine protein to creatinine ratio

- USG

urine specific gravity

- uUA/uCr

urine uric acid to creatinine ratio

- VTH

veterinary teaching hospital

1. INTRODUCTION

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a broad clinical syndrome characterized by sudden renal damage or dysfunction, frequently associated with a reduction in urine output (UO).1, 2 The diagnosis of AKI still relies on clinical findings and relative or absolute changes in serum creatinine (sCr) and UO in humans.1 Acute kidney injury is gaining attention in small animal medicine, but universally accepted diagnostic criteria are lacking.3, 4 Recently, an AKI grading system for dogs was proposed by Cowgill,5 accepted by the IRIS group (http://www.iris-kidney.com/pdf/grading-of-acute-kidney-injury.pdf), and applied in clinical settings.6, 7, 8, 9 Diagnostic criteria and five AKI grades based on medical data, sCr concentrations, and UO are suggested. Definitions for non‐azotemic and volume‐responsive AKI are proposed in the guidelines. These criteria are still rarely used for AKI diagnosis in veterinary clinical practice.

The terms “volume‐responsive” and “intrinsic” AKI have been proposed in human medicine to ameliorate the classification of “prerenal” and “renal” kidney injury.10, 11 While the concept of intrinsic AKI refers to structural damage to the renal parenchyma, volume‐responsive AKI is characterized by a transient reduction of renal function, which can be reversed after short‐term fluid administration.10, 11 Despite its potential reversibility and superior short‐term prognosis, when compared with the intrinsic form, volume‐responsive AKI is an independent risk factor for mortality in humans.12, 13 Moreover, clinicopathological or even pathological findings of renal damage have been detected in the latter state.11, 12, 14, 15 Studies designed to compare these conditions are lacking in dogs.

Serum and urine chemistry, including the evaluation of the fractional excretion (FE) of electrolytes, are used in the assessment of human AKI aiming to differentiate between functional and structural kidney injury and give prognostic information.10 Specifically, volume‐responsive AKI is characterized by low (<1%) FE of sodium (FENa), increased (>35%) FE of urea (FEurea), and increased urine creatinine (uCr) to sCr ratio (uCr/sCr; >40).10 The validity of this diagnostic paradigm in clinical practice, however, has been questioned due to the impact of different confounders (diuretic or vasopressor administration, fluid therapy, or specific AKI etiologies).16, 17, 18

Fractional excretion of electrolytes have been recently re‐evaluated in dogs with AKI as readily available and cost‐effective markers of tubular damage and kidney function.2, 7 Fractional excretion of sodium was an early and accurate predictor of AKI in a population of dogs with naturally occurring heatstroke despite fluid resuscitation.7 Additionally, a recent investigation evaluated the prognostic value of sequential changes of glomerular filtration rate (GFR), UO, and renal solute excretion in 10 dogs with naturally occurring AKI.2 Increased GFR and UO, and decreased FENa during hospitalization were associated with renal recovery and predicted survival in this population.2

The main objective of the current study was to evaluate the performance of clinical and clinicopathological variables, focusing on the FE of electrolytes and urea, in early differentiation between volume‐responsive and intrinsic AKI in a population of dogs with naturally occurring AKI and to investigate their potential for outcome prediction at the time of hospital admission. In addition, the prognostic power of an AKI grading system for dogs (http://www.iris-kidney.com/pdf/grading-of-acute-kidney-injury.pdf)5 was assessed. Our hypothesis was that the FE of electrolytes and urea could predict the occurrence of volume‐responsive or intrinsic AKI in dogs early, and that the AKI grade and urine chemistry were of prognostic value during AKI.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study design

This was a prospective, observational case‐control study with intensive care unit (ICU) follow‐up performed at a Veterinary Teaching Hospital (VTH), between February 2014 and December 2016.

2.2. Animals

Dogs with naturally occurring AKI hospitalized in the ICU of our VTH were considered for the study. Inclusion criteria were acute onset of clinical signs (<7 days) and signalment; history; and clinical, clinicopathological, and imaging findings suggesting AKI.19 In particular, sCr >1.6 mg/dL (azotemic AKI) or a progressive non‐azotemic ≥0.3 mg/dL increase in sCr from baseline within 48 hours, persistent oliguria/anuria (UO <1 mL kg−1 h−1) over 6 hours, or both criteria were required, as previously reported (http://www.iris-kidney.com/pdf/grading-of-acute-kidney-injury.pdf).5, 19 Dogs with historical, clinical, laboratory, and imaging findings consistent with chronic kidney disease (CKD), AKI on CKD, postrenal AKI (eg, uroabdomen, urinary tract obstruction), and dogs who received treatments known to increase urinary electrolyte excretion (eg, diuretics, hypertonic saline) before the admission to the ICU were excluded from the study. Additionally, dogs that were euthanized for reasons other than ethical ones were also excluded.

2.3. Grouping

Dogs were graded (I‐V) according to the IRIS grading system for AKI at the time of AKI diagnosis and through the overall study period. Volume‐responsive or intrinsic AKI were classified according to the IRIS guidelines for AKI (http://www.iris-kidney.com/pdf/grading-of-acute-kidney-injury.pdf).5 Specifically, volume‐responsive AKI was defined as an increase in urine production above 1 mL kg−1 h−1 over 6 hours of adequate fluid therapy, or a decrease in sCr concentrations to baseline over 48 hours. On the contrary, intrinsic AKI was defined as persistent azotemia for longer than 48 hours, inappropriate oligo/anuria despite appropriate fluid therapy once any volume deficit had been restored and euvolemia achieved, or both. Furthermore, dogs were classified according to their outcome as survivors if discharged alive and as nonsurvivors if they died despite medical treatment or were humanely euthanized for ethical reasons. For all dogs, the total number of days spent in the ICU was recorded. In addition, 14‐day survival and 1‐month follow‐up were recorded for survivors.

A group of dogs (n = 81) considered healthy according to history, physical examination, and clinicopathological and imaging data were included as controls.

2.4. Clinical and clinicopathological data

Complete clinical and laboratory data were collected and analyzed at the time of AKI diagnosis; clinical monitoring was performed and recorded during the overall duration of hospital stay. The Apple Fast score for illness severity was calculated.20 Daily recorded clinical data included body weight, body temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, noninvasive systolic blood pressure (SBP) measured using Doppler (Minidop ES‐100VX Hadeco Inc, Kawasaki, Japan) or an oscillometric device (petMAPTM graphic, Ramsey Medical, Inc, Tampa, Florida) according to the ACVIM guidelines,21 hydration/volume status, fluid input, and UO (mL). For the purpose of the study, UO was measured at the time of hospital admission to achieve AKI diagnosis. Only once fluid resuscitation had been performed and fluid therapy instituted for at least 6 hours, UO was used to classify AKI (intrinsic/volume‐responsive) and then during the overall hospital stay. Dogs received medical management and supportive care based on the assessment made by the ICU team and the nephrologists. Treatments were targeted to each dog individually, depending on the severity of clinical signs, hydration/volume status, UO, presence of specific organ dysfunction and electrolytes abnormalities, and presumptive or confirmed etiology of AKI. Leptospirosis was considered a differential diagnosis in dogs with known risk factors exposure and indicative clinical and laboratory findings, and diagnosed by means of a single microagglutination test titer ≥1:800 for nonvaccinal serovars or by the evidence of a 4‐fold increase in the titer in paired serum samples (convalescent titer). Sepsis was diagnosed in cases of systemic inflammatory response syndrome22 and evidence of a septic focus by means of cytology or microbiology. Discontinuation of fluid therapy and diuretic administration were performed in cases of oligo/anuria attributed to intrinsic AKI, presence of fluid overload, or both conditions. Treatment of AKI was provided through conventional medical therapy (n = 134) and peritoneal dialysis (n = 1).

Blood specimens were collected by standard venipuncture using blood vacuum collection systems; concurrent urine specimens were obtained by means of cystocentesis, spontaneous voiding, or catheterization. Samples were collected and analyzed within 1 hour after inclusion. The following analyses were performed: venous or arterial blood gas analysis including pH, base excess (BE), anion gap, lactate, and ionized calcium (iCa) concentration; CBC; and chemistry profile including sCr, albumin, total proteins, glucose, alanine transaminase, aspartate transaminase, alkaline phosphatase, total bilirubin, γ‐glutamyltransferase, cholesterol, sodium, potassium, magnesium, chloride, total calcium, phosphorus, C‐reactive protein (CRP), and uric acid. Urinalysis included urine specific gravity (USG), dipstick examination, microscopic evaluation of the urine sediment, uCr, urine protein to creatinine ratio (UPC), urine albumin to creatinine ratio (UAC), urinary electrolytes, urea and uric acid to creatinine ratio (uUA/uCr). Pigmented urine specimens were excluded from UAC and UPC measurements. The study was approved by the local Scientific Ethical Committee for Animal Testing.

2.5. Laboratory methods

CBC was obtained using an automated hematology system (ADVIA 2120, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Tarrytown NY). C‐reactive protein (CRP OSR6147, Olympus/Beckman Coulter, O'Callaghan's Mills, Ireland) and urinary albumin (MICROALBUMIN OSR6167, Olympus/Beckman Coulter, O'Callaghan's Mills, Ireland) were measured using immunoturbidimetric assays previously validated in our laboratory for dogs.23 Blood gas analysis was determined by a blood gas analyzer (ABL 800 Flex, Radiometer Medical ApS, Brønshøj, Denmark). Urine specific gravity was measured by a hand refractometer (American Optical, Buffalo, New York). Urinary proteins and uCr were measured using commercially available colorimetric methods (Urinary/CSF Protein, OSR6170, Olympus/Beckman Coulter, O'Callaghan's Mills, Irleand; Creatinine OSR6178, Olympus/Beckman Coulter, O'Callaghan's Mills, Ireland). Fractional excretion of electrolytes including FENa, FE of potassium (FEK), FE of chloride (FECl), calcium (FECa), phosphate (FEP), magnesium (FEMg), and FEurea were calculated according to the equation reported previously,2 as follows:

where uX and sX were the concentrations of a specific analyte in urine and serum, respectively. Urinary uric acid concentrations were measured using a colorimetric method (URIC ACID OSR6098 Olympus/Beckman Coulter, O'Callaghan's Mills, Ireland) and expressed as the uUA/uCr ratio. The uCr/sCr ratio was calculated. All analyses were performed using an automated chemistry analyzer (OLYMPUS AU 400, Olympus/Beckman Coulter, Brea, California).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed by standard descriptive statistics and presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median and (range), based on their distribution. Normality was assessed graphically and by using the D'Agostino‐Pearson test. The Mann‐Whitney U test and Kruskall‐Wallis test with compensated post hoc analysis were used to evaluate differences between groups (intrinsic AKI, volume‐responsive AKI and control dogs; survivors and nonsurvivors). Unclassified dogs in respect to AKI categories (n = 14) were excluded from the comparison. Categorical variables were compared using the chi‐squared test. Logistic regression and Cox proportional regression analyses (using univariate and multivariate models) were performed to evaluate risk factors for the presence of intrinsic AKI and outcome (death/survival at discharge; stepwise approach), respectively. Results were presented as hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Overall model fit was assessed by the percentage of outcome correctly classified by receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve analysis and by the chi‐squared test for the relationship between time and all the covariates in the model. Receiver operator characteristic curves were used to find optimal cut‐off values with the maximal sum of sensitivity and specificity for variables discriminating between volume‐responsive AKI and healthy controls, between volume‐responsive and intrinsic AKI, and between survivors and nonsurvivors. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was calculated. Results of all statistics were considered significant if P < .05. Statistical analyses were performed using an online available statistical software (MedCalc Statistical Software version 13.3.1 [MedCalc Software bvba, Ostend, Belgium; http://www.medcalc.org; 2014]).

3. RESULTS

A total of 135 dogs with AKI were included in the study. Median age was 7 years (0.3–16), and median body weight was 19.4 kg (1.3–69.6). Sex distribution was as follows: 54/135 (40%) intact males, 13/135 (10%) castrated males, 39/135 (29%) intact females, and 29/135 (21%) spayed females. Mixed‐breed dogs were 49/135 (36%), while purebred dogs were 86/135 (64%). Median length of hospitalization was 5 days (1–20).

3.1. Characterization of dogs with AKI

According to the IRIS grading of AKI, the following AKI grades of severity were documented in the study population: 32/135 dogs (24%) AKI grade I, 39/135 (29%) AKI grade II, 25/135 (18%) AKI grade III, 27/135 (20%) AKI grade IV, and 12/135 (9%) AKI grade V.

Continuous UO monitoring was obtained by means of an indwelling urinary catheter connected to a closed urinary drainage system (n = 100) or through voided urine collection and quantification (n = 25). Urine specimens and UO monitoring were not available in 10/135 cases because of complete anuria. Oligo/anuria was present in 47/135 (35%) dogs at the time of inclusion in the study: 37/135 dogs had inappropriate oligo/anuria and were in the intrinsic‐AKI group, 5/135 dogs had appropriate oligo/anuria and were classified as volume‐responsive AKI based on sCr changes. Five additional dogs had oligo/anuria at the initial stages of hospitalization, but early death precluded any further classification in regard to UO. Attempts to convert oligo/anuria to polyuria were made through diuretic therapy in 32/37 dogs with inappropriate oligo/anuria: in 10 dogs, UO response after furosemide administration was noticed. In the remaining 22 dogs, mannitol, diltiazem, or both drugs were considered in the absence of contraindications, without any significant increase in urine production.

Fifty‐two of 135 dogs (39%) were diagnosed as having volume‐responsive AKI, while intrinsic AKI was recognized in 69/135 (51%) dogs. AKI classification was not performed in 14/135 (10%) cases because of early death. Causes of AKI and comorbidities in the study population are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Recognized causes and diseases associated with AKI in the study population

| AKI etiologies/comorbidities | Volume‐responsive AKI (n = 52) | Intrinsic AKI (n = 69) | Unclassified AKI (n = 14) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leptospirosis | 26 | 1 | |

| Toxic | |||

| Nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs | 4 | ||

| Ethylene glycol | 4 | ||

| Noninfectious inflammatory diseases | 18 | 11 | 3 |

| Neoplasia | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| Sepsis | 21 | 6 | 3 |

| Trauma | 6 | 3 | 1 |

| Diabetic ketoacidosis | 3 | ||

| Heatstroke | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Gastric dilatation‐volvulus | 3 | 1 | |

| Undetermined etiology/miscellanea | 7 | 2 |

Overall, 80/135 (59%) dogs were classified as survivors and 55/135 (41%) as nonsurvivors. All survivors were also alive at 14 and 30 days of follow‐up. Significantly higher frequencies of death were detected in dogs with intrinsic compared with volume‐responsive AKI (52.2% versus 17.3%, P < .001), and in dogs with oligo/anuria, as previously defined, compared with nonoliguric ones (69.8% versus 23.9%, P < .001). Frequency of death was significantly higher in dogs with oligo/anuria than in dogs with intrinsic AKI dogs (P = .007).

3.2. Acute kidney injury group comparison

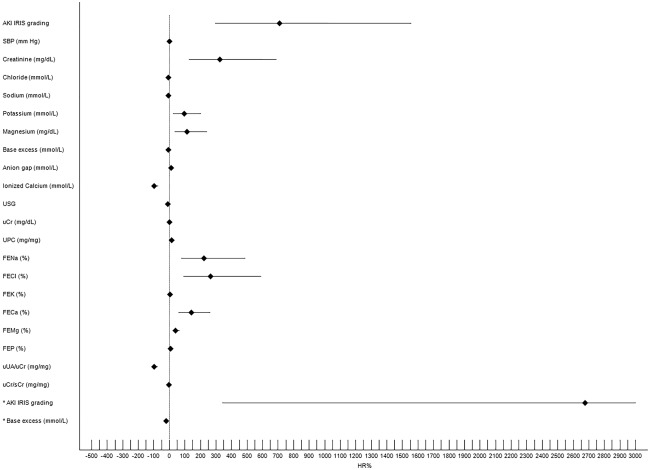

Results and main significant differences among dogs with volume‐responsive AKI, dogs with intrinsic AKI, and healthy controls are reported in Table 2. Specifically, dogs diagnosed with intrinsic AKI had significantly increased SBP, AKI grade, sCr, urea, magnesium, phosphorus, total bilirubin, anion gap, FE of electrolytes, and UPC and significantly decreased blood pH, iCa, USG, uCr, and uCr/sCr compared with dogs with volume‐responsive AKI and control dogs (Table 2 and Supporting Information Table S5). Dogs with volume‐responsive AKI had significantly higher lactate concentration and uUA/uCr than dogs with intrinsic AKI and controls. No statistically significant difference was detected for CRP and Apple Fast score between dogs with intrinsic and volume‐responsive AKI (Table 2 and Supporting Information Table S5). Results of univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis for the risk of having intrinsic AKI at the time of AKI diagnosis are reported in Figure 1. Acute kidney injury grade and BE were the only variables retained in the multivariate model.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and comparison among intrinsic AKI, volume‐responsive AKI, and control dogs for clinical and clinicopathological variables

| Variable | AKI (n = 135) | Intrinsic AKI (n = 69) | Volume‐responsive AKI (n = 52) | Controls (n = 81) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical variables and scores | |||||

| AKI IRIS grading | 2 (1–5) | 4 (1–5) b | 2 (1–4) | NA | <.001 |

| UO (mL kg−1 h−1; over 12 h) | 1.2 (0.0–7.0) | 1.4 ± 1.2 | 1.3 (0.6–7.0) | NA | .061 |

| APPLE fast score | 23.2 ± 6.3 a | 22 (12–44) a | 21.7 ± 6.4 a | 11 (7–15) | <.001 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 154 ± 35 a | 160 ± 34 a ,b | 148 ± 35 a | 128 ± 11 | <.001 |

| Serum chemistry (n = 135) | |||||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 2.41 (0.57‐21.39) a | 5.22 (1.41‐21.39) a ,b | 1.79 ± 1.69 a | 1.07 ± 0.15 | <.001 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 139 (16–785) a | 233 (30–785) a ,b | 85 (16–441) a | 34 ± 8 | <.001 |

| Urea/creatinine (mg/mg) | 41.7 (16.6–139.7) a | 40.5 (17.8–95.2) a | 43.3 (18.5–137.8) a | 32.8 ± 8.9 | <.001 |

| Phosphate (mg/dL) | 7.7 (0.8–42.2) a | 11.4 (1.1–42.2) a ,b | 5.9 ± 2.7 a | 3.7 ± 0.6 | <.001 |

| Albumin (mg/dL) | 2.75 ± 0.69 a | 2.78 ± 0.64 a | 2.70 ± 0.76 a | 3.27 ± 0.28 | <.001 |

| Chloride (mmol/L) | 104 (59–123) a | 105 ± 15 a ,b | 109 (71–122) a | 113 (107–119) | <.001 |

| Sodium (mmol/L)) | 143 (116–163) a | 142 (116–154) a ,b | 144 ± 6 a | 146 ± 3 | <.001 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4.2 (2.3–8.7) a | 4.4 (2.3–8.7) b | 4.0 ± 0.6 a | 4.5 (3.8‐5.3) | <.001 |

| Magnesium (mg/dL) | 2.70 (1.11‐6.10) a | 3.08 (1.43‐6.10) a ,b | 2.30 (1.11‐5.60) a | 2.04 ± 0.22 | <.001 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 8.08 (0.44–45.48) a | 7.07 (0.44–45.48) a | 8.83 (0.90‐38.85) a | 0.22 (0.01‐0.5) | <.001 |

| Blood gas analysis (n = 135) | |||||

| pH | 7.30 (6.90‐7.50) a | 7.30 (6.90‐7.50) a | 7.32 ± 0.09 | 7.35 ± 0.03 | .017 |

| (mmol/L) | 17.5 (6.6–40.0) a | 17.2 ± 6.5 a | 18.4 (9.1–40.0) a | 20.9 ± 1.6 | .002 |

| BE (mmol/L) | −7.1 (–28.0–43.0) a | −8.6 ± 7.6 a | −5.8 (–17.2–43.0) a | −3.4 ± 1.3 | .001 |

| Anion gap (mmol/L) | 20.7 ± 7.3 a | 23.0 ± 7.8 a ,b | 17.8 ± 5.6 a | 6.8 (3.6–15.0) | <.001 |

| Ionized calcium (mmol/L) | 1.16 (0.49‐1.41) a | 1.03 ± 0.24 a ,b | 1.18 ± 0.13 a | 1.29 (1.07‐1.36) | <.001 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 2.2 (0.3–20.0) a | 1.7 (0.3–20.0) a ,b | 3.2 ± 1.9 a | 0.9 ± 0.3 | <.001 |

| Urinalysis (n = 125) | |||||

| USG | 1020 (1007–1074) a | 1016 (1008–1050) a ,b | 1028 (1007–1074) a | 1044 ± 14 | <.001 |

| uCr (mg/dL) | 92.0 (7.6–769.8) a | 75.3 (7.6–422.5) a ,b | 130 (18–770) a | 316 ± 145 | <.001 |

| UPC (mg/mg) | 1.62 (0.09–72.00) a | 2.21 (0.09–72.00) a ,b | 1.00 (0.10‐10.15) a | 0.07 (0.04‐0.28) | <.001 |

| UAC (mg/mg) | 0.41 (0.00–55.71) a | 0.44 (0.02–55.71) a | 0.40 (0.00–5.11) a | 0.00 (0.00‐0.03) | <.001 |

| FENa (%) | 0.94 (0.01–75.81) a | 2.36 (0.04–75.81) a ,b | 0.24 (0.01–2.21) | 0.20 (0.02‐1.11) | <.001 |

| FECl (%) | 0.89 (0.03–83.45) a | 2.70 (0.06–83.45) a ,b | 0.22 (0.03‐3.14) a | 0.42 (0.04‐1.71) | <.001 |

| FEK (%) | 41.7 (1.6–399.7) a | 74.9 (5.3–399.7) a ,b | 23.3 (1.6–74.1) a | 9.47 ± 3.68 | <.001 |

| FECa (%) | 1.04 (0.05–70.02) a | 4.1 (0.1–70.0) a ,b | 0.3 (0.1–3.7) a | 0.08 (0.02‐0.82) | <.001 |

| FEMg (%) | 5.6 (0.3–131.8) a | 10.2 (0.9–80.9) a ,b | 2.9 (0.3–13.8) a | 1.61 (0.04–6.30) | <.001 |

| FEP (%) | 25.8 (0.4–233.5) a | 38.4 ± 24.9 a ,b | 17.9 ± 13.4 | 13.24 (0.17–45.91) | <.001 |

| FEurea (%) | 39.9 (2.5–533.8) a | 45.0 (2.5–121.2) a | 38.7 ± 17 a | 57.91 ± 12.60 | <.001 |

| uUA/uCr (mg/mg) | 0.07 (0.00–2.56) a | 0.05 (0.01‐0.81) b | 0.14 (0.00–2.56) | 0.05 (0.02‐0.15) | <.001 |

| uGlucose/uCr (mg/mg) | 0.21 (0.01–58.19) a | 0.32 (0.01–58.19) a ,b | 0.09 (0.01‐0.93) a | 0.03 (0.01‐0.11) | <.001 |

| uCr/sCr (mg/mg) | 34 (1–546) a | 14 (1–218) a ,b | 78 (10–546) a | 285 (50–780) | <.001 |

Data are reported as mean ± SD or median and (range) based on their distribution.

Abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; BE, base excess; CRP, C‐reactive protein; FECa, fractional excretion of calcium; FECl, fractional excretion of chloride; FEK, fractional excretion of potassium; FEMg, fractional excretion of magnesium; FENa, fractional excretion of sodium; FEP, fractional excretion of phosphate; FEurea, fractional excretion of urea; NA, not applicable; SBP, systolic blood pressure; UAC, urine albumin to creatinine ratio; uCr, urine creatinine; uCr/sCr, urine creatinine to serum creatinine ratio; uGlucose/uCr, urine glucose to creatinine ratio; UO, urinary output; UPC, urine protein to creatinine ratio; USG, urinary specific gravity; uUA/uCr, urine uric acid to creatinine ratio.

aSignificantly different from control dogs.

bSignificantly different from dogs with volume‐responsive AKI.

Figure 1.

Forest plot showing results of the univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses for the prediction of intrinsic AKI in the study population. Black rhombus represents HR reported as percentage of risk (HR%). The horizonal black line indicates the 95% confidence interval values. Asterisk indicates variables retained in the multivariate model. The upper limit of 95% Confidence Interval for AKI grade in the multivariate model was 17392, and the horizontal line was truncated at 3000 for graphical reasons (see Table 3 in Supporting Information for details). Only variable with P < .05 are reported. FECa, fractional excretion of calcium; FECl, fractional excretion of chloride; FEK, fractional excretion of potassium; FEMg, fractional excretion of magnesium; FENa, fractional excretion of sodium FEP, fractional excretion of phosphate; HR, hazard ratio; SBP, systolic blood pressure; uCr, urine creatinine; uCr/sCr, urine creatinine to serum creatinine ratio; UPC, urine protein to creatinine ratio; USG, urine specific gravity; uUA/uCr urine uric acid to urine creatinine ratio; uCr/sCr urine creatinine to serum creatinine ratio

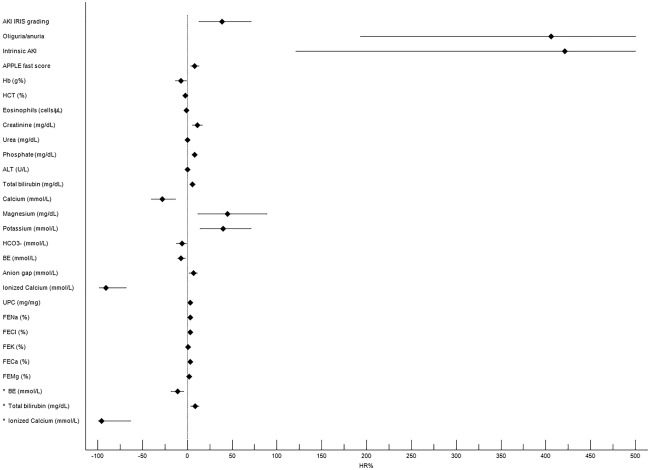

Nonsurvivors had significantly higher AKI grade, sCr, urea, potassium, phosphorus, magnesium, total bilirubin, anion gap, FE of electrolytes, UPC, and Apple Fast score values and significantly lower hemoglobin, iCa, BE, pH, and uCr/sCr values than survivors (Table 3 and Supporting Information Table S7). These findings were mainly confirmed when the comparison between survivors (n = 33) and nonsurvivors (n = 36) was performed in dogs having intrinsic AKI (Supporting Information Table S8). Several variables were associated with an increased risk of death in the overall population of dogs with AKI. Base excess, total bilirubin, and iCa were retained in the multivariate model (Figure 2 and Supporting Information Table S9).

Table 3.

Comparison of clinical and clinicopathological variables between surviving (n = 80) and nonsurviving (n = 55) dogs with AKI

| Variable (n = 135) | Survivors | Nonsurvivors | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical variables and scores | |||

| AKI IRIS grading | 2 (1–5) | 3 (1–5) | .003 |

| UO (mL kg−1 h−1; over 12 hours) | 1.4 (0.2–7.0) | 0.7 (0.0–4.7) | <.001 |

| APPLE fast score | 21.6 ± 5.3 | 26.5 ± 6.9 | <.001 |

| Serum chemistry (n = 135) | |||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 2.2 (0.6–11.8) | 4.4 (0.8–21.4) | .002 |

| Phosphate (mg/dL) | 6.6 (0.8–30.0) | 11.2 (1.8–42.2) | <.001 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 9.9 ± 0.9 | 9.1 ± 1.6 | .009 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4.1 (2.3–8.0) | 4.3 (2.7–8.7) | .011 |

| Chloride (mmol/L) | 107 (605‐123) | 97 (59–120) | .039 |

| Magnesium (mg/dL) | 2.52 (1.11‐5.60) | 3.04 (1.64‐6.10) | .017 |

| Blood gas analysis (n = 135) | |||

| pH | 7.31 ± 0.08 | 7.26 ± 0.12 | .027 |

| (mmol/L) | 18.5 (8.5–40.0) | 14.7 (6.6–38.1) | .005 |

| BE (mmol/L) | −5.9 (–17.2–43.0) | −9.6 (‐28.0–10.7) | .003 |

| Anion gap (mmol/L) | 18.8 ± 6.9 | 23.5 ± 6.9 | .002 |

| Ionized calcium (mmol/L) | 1.19 (0.64‐1.41) | 1.09 (0.49‐1.38) | .003 |

| Urinalysis (n = 125) | |||

| UPC (mg/mg) | 1.4 (0.1–14.7) | 2.7 (0.2–72.0) | .001 |

| FENa (%) | 0.60 (0.01–50.45) | 1.60 (0.03–75.81) | .004 |

| FECl (%) | 0.57 (0.05–49.24) | 2.57 (0.03–83.45) | .004 |

| FEK (%) | 34.3 (1.6–215.9) | 59.9 (5.3–399.7) | <.001 |

| FECa (%) | 0.6 (0.1–56.1) | 4.0 (0.1–70.0) | <.001 |

| FEMg (%) | 4.8 (0.3–70.6) | 12.0 (0.3–131.8) | <.001 |

| uGlucose/uCr (mg/mg) | 0.13 (0.01–17.37) | 0.45 (0.01–58.19) | .001 |

| uCr/sCr (mg/mg) | 45.5 (1.9–545.9) | 17.4 (1.2–377.2) | .006 |

Only statistically significant variables (P < .05) are reported.

Abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; BE, base excess; FECa, fractional excretion of calcium; FECl, fractional excretion of chloride; FEK, fractional excretion of potassium; FEMg, fractional excretion of magnesium; FENa, fractional excretion of sodium; uCr/sCr, urine creatinine to serum creatinine ratio; uGlucose/uCr, urine glucose to creatinine ratio; UO, urinary output; UPC, urine protein to creatinine ratio.

Figure 2.

Forest plot reporting results of univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses for the prediction of mortality in dogs with AKI. Black rhombus represents HR reported as percentage of risk (HR%). The horizontal black line indicates the 95% confidence interval values. Asterisk indicates variables retained in the multivariate model. In the univariate model, the horizontal lines indicating the upper limit of 95% confidence interval for intrinsic AKI (1131) and oligo/anuria (773) were truncated at 500 for graphical reasons (see Table 5 in supporting information for details). Only variables with P < .05 are reported. ALT, alanine transaminase; BE, base excess; FECa, fractional excretion of calcium; FECl, fractional excretion of chloride; FEK, fractional excretion of potassium; FEMg, fractional excretion of magnesium; FENa, fractional excretion of sodium; Hb, hemoglobin concentration; HCT, hematocrit value; HR, hazard ratio; UPC, urine protein to creatinine ratio. Oliguria/anuria defined as urinary output <1 mL kg– 1 h– 1 for at least 6 hours

Results of ROC curve analyses evaluating the FE of electrolytes and uCr/sCr for the discrimination between volume‐responsive AKI and healthy controls, volume‐responsive and intrinsic AKI, and survivors and nonsurvivors are reported in Table 4.

Table 4.

Results of ROC curve analyses evaluating the FE of electrolytes and uCr/sCr for discrimination between study groups

| Variable | AUC | Cut‐off | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Volume‐responsive AKI versus healthy controls | |||||

| FENa (%) | 0.556 | <0.64 | 25 | 96.3 | .336 |

| FECl (%) | 0.660 | <0.22 | 55.3 | 80.0 | .004 |

| FEMg (%) | 0.685 | <3.16 | 50.0 | 81.5 | <.001 a |

| FECa (%) | 0.901 | <0.16 | 91.5 | 77.5 | <.001 a , b , c |

| FEK (%) | 0.870 | <17.79 | 70.8 | 98.8 | <.001 a , b , c |

| uCr/sCr (mg/mg) | 0.883 | >163 | 83.3 | 81.5 | <.001 a , b , c |

| (b) Intrinsic versus volume‐responsive AKI | |||||

| FENa (%) | 0.856 | >0.90 | 83.3 | 75.8 | <.001 |

| FECl (%) | 0.872 | >0.53 | 78.7 | 83.9 | <.001 |

| FEMg (%) | 0.879 | >4.93 | 82.6 | 83.6 | <.001 |

| FECa (%) | 0.885 | >0.55 | 76.6 | 90.3 | <.001 |

| FEK (%) | 0.868 | >33.9 | 77.1 | 85.5 | <.001 |

| uCr/sCr (mg/mg) | 0.883 | <33.6 | 87.5 | 90.0 | <.001 |

| (c) Survivors versus nonsurvivors | |||||

| FENa (%) | 0.654 | >4.38 | 41.7 | 93.4 | .004 |

| FECl (%) | 0.657 | >7.49 | 38.3 | 94.7 | .005 |

| FEMg (%) | 0.697 | >11.64 | 51.1 | 85.3 | <.001 |

| FECa (%) | 0.701 | >3.41 | 55.3 | 81.6 | <.001 |

| FEK (%) | 0.692 | >130 | 35.4 | 96.1 | <.001 |

| uCr/sCr (mg/mg) | 0.646 | ≤7.36 | 41.7 | 93.5 | .008 |

Cut‐off values with the maximal sum of sensitivity and specificity are provided to identify controls (a), intrinsic AKI (b) and non‐survivors (c).

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; FECa, fractional excretion of calcium; FECl, fractional excretion of chloride; FEK, fractional excretion of potassium; FEMg, fractional excretion of magnesium; FENa, fractional excretion of sodium; ROC, receiver operator characteristic; uCr/sCr, urine creatinine to serum creatinine ratio. P value refers to the ROC curve analysis for single variables.

aSignificantly different from FENa in the ROC curve comparison.

bSignificantly different from FECl in the ROC curve comparison.

cSignificantly different from FEMg in the ROC curve comparison.

4. DISCUSSION

Our study characterized clinical and clinicopathological features of AKI occurring in a wide population of critically ill dogs. The prevalence rates of intrinsic and volume‐responsive AKI were similar in the study population. Causes and diseases associated with AKI were various and mainly related to septic and noninfectious inflammatory conditions. These results are in partial contrast with the available veterinary literature, as volume‐responsive AKI seems to be poorly represented, and AKI during sepsis or systemic inflammation is scarcely documented in dogs.4, 19, 24, 25, 26 On the contrary, systemic inflammation and sepsis are the most common conditions associated with AKI in humans.4, 12 Our findings might be due to a different case series composition and case selection based on the novel and more sensitive diagnostic criteria for AKI used.

Several clinical and clinicopathological variables could discriminate between intrinsic and volume‐responsive AKI at the time of diagnosis in the study population. In particular, higher SBP, a more severe reduction of renal function, and a lower urinary concentrating ability associated with higher concentrations of urine proteins and greater electrolytes losses, were significantly related to the presence of intrinsic AKI. These results suggest that the structural integrity of renal tubules and parenchyma are more severely compromised during intrinsic AKI, with subsequent uremic toxin accumulation and more serious acid/base derangements.27

Fractional excretion of various electrolytes performed similarly and well overall in the differentiation between intrinsic and volume‐responsive AKI, being potentially promising and easy to obtain at the time of AKI diagnosis. Interestingly, the cut‐off values of FENa and uCr/sCr detected in the current study are in line with the ones recognized and recommended in humans.10 Fractional excretion of urea was not different between intrinsic and volume‐responsive AKI and control dogs, refuting our initial hypothesis. Species‐specific differences due to urea metabolism, renal handling, and dietary supply might potentially account for the lack of its diagnostic significance, in contrast to the data reported in humans,10, 18 and warrant further investigations.

Significant increases in blood lactate concentration and uUA/uCr were documented in dogs with volume‐responsive AKI compared with those with intrinsic AKI and healthy dogs. A more severe grade of tissue hypoperfusion characterizing volume‐responsive AKI might explain our findings. Urinary uric acid has been proposed as a marker of tissue hypoxia in humans,28, 29 and an increase in uUA/uCr occurs in dogs with volume‐responsive AKI and systemic inflammation combined with alterations in variables of low tissue perfusion.30

Our study documented a significantly lower frequency of death in dogs with volume‐responsive AKI than in those with intrinsic AKI. According to our diagnostic criteria, dogs with volume‐responsive AKI had an apparently less severe impairment of renal function documented by a lower AKI grade and sCr upon admission. Although GFR could not be correctly estimated by sCr during AKI, this hypothesis might explain the lower case fatality rate noticed in this group. Discriminating intrinsic versus volume‐responsive AKI could not have any apparent therapeutic implication.31 However, the early differentiation of transient volume‐responsive kidney injury from the intrinsic form could add clinical and prognostic information. In this regard, both the veterinary clinician and the animal owner could be supported in the decision‐making process and the management of the AKI patient (eg, predicting the reversibility of kidney failure, or proposing adequate therapies depending on the expected “renal outcome”). The potential of urine chemistry to distinguish between these conditions quickly at the time of AKI diagnosis is, therefore, of value and supports its evaluation in the clinical practice.

The performances of urine chemistry and FE of electrolytes with respect to AKI diagnosis were variable in our study. In this regard, FECa, FEK, and uCr/sCr performed excellently (Table 4), showing that lower FEs and higher uCr/sCr values should be expected in healthy dogs with normal renal function. On the contrary, and unexpectedly, FENa was not different between volume‐responsive AKI and control dogs. These latter results are difficult to compare with the available veterinary literature due to the paucity of data and the lack of inclusion of healthy control dogs.7, 25, 32 Moreover there is evidence that AKI in the course of sepsis and systemic inflammation can trigger severe sodium retention in humans.16, 33 For these reasons, the diagnostic value of FE of electrolytes other than sodium could be more suitable for the diagnosis and prediction of AKI in similar settings in dogs.

The case fatality in our study was 41% and is partially in line with the previous case fatality rates for dogs with AKI.34, 35, 36 Although dogs with volume‐responsive and intrinsic AKI showed similar grades of disease severity at the time of hospital admission, as indicated by similar Apple Fast scores, dogs with intrinsic AKI had higher IRIS AKI grades and higher frequencies of death, as previously stated. This result underlines the significant impact of intrinsic kidney damage on the overall patient outcome, independently of the final diagnosis. However, reversibility of renal dysfunction does not define the absence of mortality risk, as nearly 20% of the enrolled dogs with volume‐responsive AKI died in our study. Limited studies have reported various variables as potential risk factors for mortality in dogs with AKI, including hypercalcemia, hyperphosphatemia, proteinuria, anemia, and different grading systems to reflect AKI severity, while the prognostic role of azotemia at the time of hospital admission remains controversial.19, 37, 38, 39, 40 Recently, increased GFR and UO and decreased FENa over the course of hospitalization were associated with renal recovery and predicted survival in a population of 10 dogs with naturally occurring AKI mainly managed using hemodialysis.2 Several clinical and clinicopathological variables were associated with mortality in our population of dogs with AKI, including FE of electrolytes; overall, they were mainly indexes of renal dysfunction and tubular impairment. In particular, FECa had the best diagnostic and prognostic accuracy among the FEs evaluated in the study. Moreover, sCr and uCr/sCr upon admission had a prognostic value in our cohort. These results might have been influenced by case series composition and AKI etiologies or mainly by the lack of renal replacement therapy in our setting. Nevertheless, the prognostic impact of variables that could reflect renal damage/dysfunction independently of the therapeutic management available, such as FE of electrolytes, was shown to be more useful in dogs with AKI, as previously suggested.2

Urinary volume was predictive of death in previous studies in dogs2, 38 and maintains a prognostic role in humans.41 Frequencies of death were significantly higher in dogs with oligo/anuria (UO <1 mL kg−1 h−1 for at least 6 hours in the face of euvolemia), and presence of oligo/anuria was among the variables retained in the univariate survival analysis. Since most of the dogs showing oligo/anuria at the time of inclusion in the study had intrinsic AKI, hence the most severe form of renal disease, this result might be expected in our cohort. However, frequency of death was significantly higher in dogs with oligo/anuria than in dogs with intrinsic AKI, confirming the prognostic role of UO alone when conventional treatment for AKI is performed. These statements corroborate the clinical usefulness of the IRIS grading system for AKI, in which UO is combined with other clinical and laboratory variables for AKI diagnosis and classification.

According to the survival analysis, BE, iCa, and total bilirubin were significantly associated with mortality. These data are preliminary and partially in line with the available literature on AKI in dogs.37 In addition, the prognostic role of hyperbilirubinemia, metabolic acidosis, and hypocalcemia has been suggested previously in critically ill dogs in different clinical settings, particularly during sepsis.25, 42, 43, 44 For these reasons, in our cohort, their prognostic role might have been influenced by factors other than renal damage, as well as by AKI etiology (eg, leptospirosis, sepsis), and requires further assessment.

There are some limitations to acknowledge when interpreting our results. No clearance study was performed for our study. Although clearance techniques using timed urine collection are considered gold standard to assess the daily urinary solute excretions,32, 45, 46 a recent study suggested that FE can be used in clinical practice as a reliable surrogate for fractional clearance of urinary solutes in dogs.2 Although unlikely due to the historical, laboratory, and imaging findings of the dogs in our study, pre‐existing renal disease cannot be completely ruled out. Additionally, specimens and data collected through the overall hospitalization period to assess full renal recovery were not analyzed for our study nor were novel biomarkers of kidney damage aimed at a better characterization of volume‐responsive AKI. Finally, previous or ongoing fluid therapy was not considered as an exclusion criteria for the study. Although only a minority of dogs was included while on intravenous fluid therapy (data not shown), the impact of fluid administration on FE values should be considered, especially in the comparison between AKI and control dogs.

In conclusion, our study contributes to the characterization of AKI in a wide population of critically ill dogs. Volume‐responsive and intrinsic AKI seem to be related to numerous etiologies, mainly of inflammatory and septic origin. Fractional excretion of electrolytes and of uCr/sCr in particular show good performances for the differentiation between volume‐responsive and intrinsic AKI at the time of diagnosis and could also act as prognostic tools. Their measurement could be suggested in daily practice, as they are feasible and cost‐effective biomarkers of tubular integrity and function. The clinical application of both sCr and UO criteria to diagnose AKI and grade the disease in dogs, as performed in our study, could be strongly recommended in veterinary practice, to raise the suspicion of the disease in high‐risk patients and to obtain prognostic information, with significant implications in research and clinical fields.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DECLARATION

Authors declare no conflict of interest

OFF‐LABEL ANTIMICROBIAL DECLARATION

Authors declare no off‐label use of antimicrobials

INSTITUTIONAL ANIMAL CARE AND USE COMMITTEE (IACUC) OR OTHER APPROVAL DECLARATION

The study was approved by the local Scientific Ethical Committee for Animal Testing.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found online in the supporting information tab for this article.

Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was done at the University of Bologna‐Veterinary Teaching Hospital, Department of Veterinary Medical Sciences, Alma Mater Studiorum ‐ University of Bologna, Via Tolara di Sopra 50, 40064, Ozzano dell'Emilia (BO), Italy. Preliminary results were presented as oral presentation to the 14th EVECCS Congress, 11th‐14th June 2015, Lyon, France.

Troìa R, Gruarin M, Grisetti C, et al. Fractional excretion of electrolytes in volume‐responsive and intrinsic acute kidney injury in dogs: Diagnostic and prognostic implications. J Vet Intern Med. 2018;32:1372–1382. 10.1111/jvim.15146

REFERENCES

- 1. Kellum JA, Lameire N; KIDIGO AKI Guideline Work Group . Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of acute kidney injury: a KIDIGO summary (Part 1). Crit Care. 2013;17:204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brown N, Segev G, Francey T, Kass P, Cowgill LD. Glomerular filtration rate, urine production and fractional clearance of electrolytes in acute kidney injury in dogs and their association with survival. J Vet Intern Med. 2015;29:28–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Harison E, Langston C, Palma D, Lamb K. Acute azotemia as a predictor of mortality in dogs and cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2012;26:1093–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Keir I, Kellum JA. Acute kidney injury in severe sepsis: pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment recommendations. J Vet Emer Crit Care. 2015;25:200–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cowgill LD. Staging patients with acute kidney injury: a new paradigm. In: Proceedings of the 2010 ACVIM forum; June 9–12, 2010; Anaheim, CA.

- 6. De Loor J, Daminet S, Smets P, Maddens B, Meyer E. Urinary biomarkers for acute kidney injury in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2013;27:998–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Segev G, Daminet S, Meyer E, et al. Characterization of kidney damage using several renal biomarkers in dogs with naturally occurring heatstroke. Vet J. 2015;206:231–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sigrist NE, Kalin N, Dreyfus A. Changes in serum creatinine concentration and acute kidney injury (AKI) grade in dogs treated with hydroxyethyl starch 130/0.4 from 2013 to 2015. J Vet Intern Med. 2017;31:434–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nivy R, Avital Y, Aroch I, Segev G. Utility of urinary alkaline phosphatase and y‐glutamyl transpeptidase in diagnosing acute kidney injury in dogs. Vet J. 2017;220:43–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Makris K, Spanou L. Acute kidney injury: diagnostic approaches and controversies. Clin Biochem Rev. 2016;37:153–175. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Himmelfarb J, Joannidis M, Molitoris B, et al. Evaluation and initial management of acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:962–967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Endre ZH, Kellum JA, Di Somma S, et al. Differential diagnosis of AKI in clinical practice by functional and damage biomarkers: Workgroup Statements from the Tenth Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative Consensus Conference. Contrib Nephrol. 2013;182:30–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Uchino S, Bellomo R, Bagshaw SA, Goldsmith D. Transient azotemia is associated with a high risk of death in hospitalized patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:1833–1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vanmassenhove J, Glorieux G, Hoste E, Dhondt A, Vanholder R, Van Biesen W. AKI in early sepsis in a continuum from transient AKI without tubular damage over transient AKI with minor tubular damage to intrinsic AKI with severe tubular damage. Int Urol Nephrol. 2014;46:2003–2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sharfuddin AA, Molitoris BA. Pathophysiology of ischemic acute kidney injury. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2011;7:189–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Prowle J, Bagshaw SM, Bellomo R. Renal blood flow, fractional excretion of sodium and acute kidney injury: time for a new paradigm? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2012;18:585–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bagshaw SM, Bennett M, Devarajan P, Bellomo R. Urine biochemistry in septic and non‐septic acute kidney injury: a prospective observational study. J Crit Care. 2013;28:371–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vanmassenhove J, Glorieux G, Hoste E, Dhondt A, Vanholder R, Van Biesen W. Urinary output and fractional excretion of sodium and urea as indicators of transient versus intrinsic acute kidney injury during early sepsis. Crit Care. 2013;17:R234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cowgill LD, Langston C. Acute kidney insufficiency In: Bartges J, Polzin DJ, eds. Nephrology and Urology of Small Animals. New Jersey: Wiley‐Blackwell; 2011:472–523. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hayes G, Mathews K, Doig G, et al. The acute patient physiologic and laboratory evaluation (APPLE) score: a severity of illness stratification system for hospitalized dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2010;24:1034–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brown S, Atkins C, Bagley R, et al. Guidelines for the identification, evaluation, and management of systemic hypertension in dogs and cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2007;21:542–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hauptman JG, Walshaw R, Olivier NB. Evaluation of the sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic criteria for sepsis in dogs. Vet Surg. 1997;26:393–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gentilini F, Mancini D, Dondi F, et al. Validation of a human immunoturbidimetric assay for measuring canine C‐reactive protein. Vet Clin Pathol. 2005;34:318. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ateca LB, Drobatz KJ, King LG. Organ dysfunction and mortality risk factors in severe canine bite wound trauma. J Vet Emerg Crit Care (San Antonio). 2014;24:705–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Giunti M, Troia R, Famigli Bergamini P, Dondi F. Prospective evaluation of the acute patient physiologic and laboratory evaluation score and an extended clinicopathological profile in dogs with systemic inflammatory response syndrome. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2015;25:226–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kenney EM, Rozanski EA, Rush JE, et al. Association between outcome and organ system dysfunction in dogs with sepsis: 114 cases (2003–2007). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2010;236:83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Devarajan P. Acute kidney injury: still misunderstood and misdiagnosed. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017;13:137–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ozanturk E, Ucar ZZ, Koca H, et al. Urinary uric acid excretion as an indicator of severe hypoxia and mortality in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Rev Port Pneumol. 2016;22:18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kosmadakis G, Viskaduraki M, Michail S. The validity of fractional excretion of uric acid in the diagnosis of acute kidney injury due to decreased kidney perfusion. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54:1186–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Troìa R, Gruarin M, Agnoli C, et al. Urinary uric acid excretion in dogs with acute kidney injury and systemic inflammation. Abstract from the International Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care Symposium, the European Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care Annual Congress, and the ACVECC VetCOT Veterinary Trauma & Critical Care Conference 2016. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2016; doi: 10.1111/vec.12516, S31–32.

- 31. Bellomo R, Bagshaw S, Langenberg C, Ronco C. Pre‐renal azotemia: a flowed paradigm in critically ill septic patients? Contrib Nephrol. 2007;156:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lefebvre HP, Dossin O, Trumel C, Braun JP. Fractional excretion tests: a critical review of methods and applications in domestic animals. Vet Clin Pathol. 2008;37:4–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vitorio D, Maciel AT. Acute kidney injury induced by systemic inflammatory response syndrome is an avid and persistent sodium‐retaining state. Case Rep Crit Care. 2014;2014:471658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Segev G, Kass PH, Francey T, Cowgill LD. A novel clinical scoring system for outcome prediction in dogs with acute kidney injury managed by hemodialysis. J Vet Intern Med. 2008;22:301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Thoen ME, Kerl ME. Characterization of acute kidney injury in hospitalized dogs and evaluation of a veterinary acute kidney injury staging system. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2011;21:648–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Segev G, Langston C, Takada K, Kass PH, Cowgill LD. Validation of a clinical scoring system for outcome prediction in dogs with acute kidney injury managed by hemodialysis. J Vet Intern Med. 2016;30:803–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vaden SL, Levine J, Breitschwerdt EB. A retrospective case‐control of acute renal failure in 99 dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 1997;11:58–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Behrend EN, Grauer GF, Mani I, Groman RP, Salman MD, Greco DS. Hospital‐acquired acute renal failure in dogs: 29 cases (1983–1992). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1996;208:537–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lee YJ, Chang CC, Chan PW, Hsu WL, Lin KW, Wong ML. Prognosis of acute kidney injury in dogs using RIFLE (Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss and End‐stage renal failure) like criteria. Vet Rec. 2011;168:264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mastrorilli C, Dondi F, Agnoli C, Turba ME, Vezzali E, Gentilini F. Clinicopathologic features and outcome predictors of Leptospira interrogans Australis serogroup infection in dogs: a retrospective study of 20 cases (2001–2004). J Vet Intern Med. 2007;21:3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kellum JA, Sileanu FE, Murugan R, Lucko N, Shaw AD, Clermont G. Classifying AKI by urine output versus serum creatinine level. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:2231–2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Conti‐Patara A, Caldeira J, de Mattos‐Junior E, et al. Changes in tissue perfusion parameters in dogs with severe sepsis/septic shock in response to goal‐directed hemodynamic optimization at admission to ICU and the relation to outcome. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2012;22:409–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Luschini MA, Fletcher DJ, Schoeffler GL. Incidence of ionized hypocalcemia in septic dogs and its association with morbidity and mortality: 58 cases (2006–2007). J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2010;20:406–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Goggs R, Dennis SG, Di Bella A, et al. Predicting outcome in dogs with primary immune‐mediated hemolytic anemia: results of a multicenter case registry. J Vet Intern Med. 2015;29:1603–1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pressler BM. Clinical approach to advanced renal function testing in dogs and cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2013;43:1193–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Finco DR, Brown SA, Barsanti JA, Bartges JW, Cooper TA. Reliability of using random urine samples for “spot” determination of fractional excretion of electrolytes in cats. Am J Vet Res. 1997;58:1184–1187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional Supporting Information may be found online in the supporting information tab for this article.

Supporting Information