The proper placement of different cell types during a developmental program requires the creation and maintenance of a biological pattern to define the cells that will differentiate. Here we show that the HetN inhibitor, responsible for pattern maintenance of specialized nitrogen-fixing heterocyst cells in the filamentous cyanobacterium Anabaena, may be produced from two different start methionine codons. This work demonstrates that the two start sites are individually involved in a different HetN function, either membrane localization or inhibition of cellular differentiation.

KEYWORDS: Anabaena, cyanobacteria, development, hetN, heterocyst

ABSTRACT

Multicellular organisms must carefully regulate the timing, number, and location of specialized cellular development. In the filamentous cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120, nitrogen-fixing heterocysts are interspersed between vegetative cells in a periodic pattern to achieve an optimal exchange of bioavailable nitrogen and reduced carbon. The spacing between heterocysts is regulated by the activity of two developmental inhibitors, PatS and HetN. PatS functions to create a de novo pattern from a homogenous field of undifferentiated cells, while HetN maintains the pattern throughout subsequent growth. Both PatS and HetN harbor the peptide motif ERGSGR, which is sufficient to inhibit development. While the small size of PatS makes the interpretation of inhibitory domains relatively simple, HetN is a 287-amino-acid protein with multiple functional regions. Previous work suggested the possibility of a truncated form of HetN containing the ERGSGR motif as the source of the HetN-derived inhibitory signal. In this work, we present evidence that the glutamate of the ERGSGR motif is required for proper HetN inhibition of heterocysts. Mutational analysis and subcellular localization indicate that the gene encoding HetN uses two methionine start codons (M1 and M119) to encode two protein forms: M1 is required for protein localization, while M119 is primarily responsible for inhibitory function. Finally, we demonstrate that patS and hetN are not functionally equivalent when expressed from the other gene's regulatory sequences. Taken together, these results help clarify the functional forms of HetN and will help refine future work defining a HetN-derived inhibitory signal in this model of one-dimensional periodic patterning.

IMPORTANCE The proper placement of different cell types during a developmental program requires the creation and maintenance of a biological pattern to define the cells that will differentiate. Here we show that the HetN inhibitor, responsible for pattern maintenance of specialized nitrogen-fixing heterocyst cells in the filamentous cyanobacterium Anabaena, may be produced from two different start methionine codons. This work demonstrates that the two start sites are individually involved in a different HetN function, either membrane localization or inhibition of cellular differentiation.

INTRODUCTION

The development of a multicellular organism relies on the spatiotemporal regulation of signals to properly place different cell types. Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 (here Anabaena) is a multicellular filamentous cyanobacterium that places specialized nitrogen-fixing heterocysts in a periodic pattern in response to nitrogen starvation (1–3). Heterocysts are morphologically distinct, terminally differentiated cells that create a microoxic environment for the oxygen-labile nitrogenase complex to fix environmental dinitrogen into ammonia, which is provided to adjacent photosynthetic vegetative cells in exchange for a source of reductant. A semiregular interval of 10 to 20 photosynthetic vegetative cells is formed and maintained between heterocysts to ensure that all cells receive fixed nitrogen and therefore maintain filament integrity. The biological pattern that places heterocysts is initially formed and subsequently perpetuated by the interactions of three key regulators, HetR, PatS, and HetN, in a manner consistent with the activator-inhibitor model.

The activator-inhibitor model, proposed by Alan Turing and refined by Gierer and Meinhardt, is the basis of biological pattern formation in a variety of organisms across genera (4–6). This model is predicated on the function of an autocatalytic activator that regulates both its own production and the production of its inhibitor, which prevents differentiation via the inactivation of the activator. The activator and inhibitor may diffuse from source cells at differing rates to create a pattern from a homogenous field of cells. In this case, the interaction of the activator (HetR) and its inhibitors (PatS and HetN) defines and maintains the pattern of cells capable of differentiating into heterocysts along filaments in the Anabaena developmental system. HetR is an autocatalytic transcriptional regulator that is required for differentiation in a wild-type background; strains lacking a functional copy of hetR fail to differentiate, while those overexpressing hetR produce supernumerary heterocysts (7–9). The expression of hetR is upregulated early in the developmental cascade, and patterned expression in cells that will become heterocysts has been shown to occur roughly 8 to 10 h after the induction of differentiation (9). HetR binds to its own promoter region and that of its inhibitor patS, and such interactions with DNA are required for HetR to exert its regulatory function (10, 11). While HetR has not been shown to diffuse between cells, PatS- and HetN-dependent inhibitory signals produced by source cells have been demonstrated (12).

PatS is a 17-amino-acid peptide that is upregulated by HetR, and its activity travels laterally from source cells (10, 12, 13). The interaction of PatS and HetR leads to the posttranslational degradation of HetR and creates the periodicity of vegetative and heterocyst cells characteristic of wild-type Anabaena (12, 14). This periodic pattern can be visualized about 8 h after the induction of differentiation by the cell-type-specific expression of hetR or patS promoter fusions to the green fluorescent protein gene (gfp) (9, 15). Anabaena strains lacking patS produce a multiple-contiguous-heterocyst (Mch) phenotype by 24 h postinduction, which gradually resolves into a wild-type pattern of heterocyst spacing over time (13). Pattern resolution is driven by the second inhibitor, HetN, which is expressed later in developing heterocysts and functions to maintain the regular spacing of heterocysts along filaments (16–18). Mutations in hetN, originally annotated as a ketoacyl reductase gene, that abrogate inhibitory function result in an Mch phenotype that is not visible until roughly 48 h postinduction. Thus, the PatS- and HetN-dependent inhibitory signals contribute to de novo pattern formation and pattern maintenance, respectively.

Although PatS and HetN regulate the progression of development differently, they share a conserved RGSGR motif that is absolutely required for function (13, 19, 20). Mutations in the RGSGR motif result in the production of greatly attenuated or nonfunctional patS and hetN alleles. The exogenous addition of the RGSGR pentapeptide to cultures of the wild type inhibits heterocyst formation, and in vitro studies have shown that this pentapeptide interacts directly with HetR (13, 14). While the pentapeptide RGSGR interacts with HetR, the addition of one conserved amino acid (ERGSGR) results in a much higher binding affinity for HetR in vitro (21). Mutational analysis of the entire patS gene identified amino acids required for activity and showed that mutation of the conserved glutamate in the ERGSGR motif resulted in a patS allele with decreased function (20). The mutation of four regions of hetN that show differences in hydrophobicity demonstrated that the E/RGSGR motif and the region upstream are required for protein function (19, 22). Despite those studies, the exact nature of the mature PatS and HetN inhibitors remains unknown.

Previous work has shown that the full-length HetN protein does not exit the producing cell, but a HetN-dependent signal is exported from source cells (23). It is therefore possible that HetN is processed following translation or that a truncated form of HetN is produced. Here we show that, like PatS, HetN alleles lacking the glutamate residue in the conserved ERGSGR motif display decreased functionality. Five possible translational start sites in the N terminus of HetN upstream of the ERGSGR motif were assessed, and it was found that M119 is required for the production of the HetN-dependent inhibitory signal when expressed from the native locus. Additionally, swapping of the inhibitors at the native loci (patS in the place of hetN and vice versa) also demonstrated that patS and hetN are not functionally redundant. These results indicate that HetN can be produced from an alternate translational start site and may produce a truncated protein to maintain heterocyst patterning.

RESULTS

The E131 residue of HetN is required for proper function.

Both PatS and HetN are required for the formation and maintenance of a biological pattern that ensures the proper spacing of heterocysts along Anabaena filaments. Each protein acts by diffusing its activity laterally from source cells to inhibit HetR function via direct binding, which leads to the posttranslational degradation of HetR (12, 20, 23). In previous work, a conserved RGSGR motif present in both PatS and HetN has been shown to catalyze HetR degradation when added exogenously to growth medium (12, 13, 19). The removal of this motif, or mutation of amino acids within it, abrogates or decreases the inhibitory capacity of PatS or HetN (19, 20, 22). Recent work to identify amino acids required for PatS function showed that an E12A mutation yielded an allele with decreased inhibition, which resulted in an increased percentage of heterocysts formed (20). This glutamate residue in PatS is present in the ERGSGR sequence (amino acids 12 to 17), and these six amino acids are conserved in HetN (amino acids 131 to 136). It is therefore possible that this conserved glutamate is required for the normal function of both inhibitors. To determine the contribution of E131 to the function of HetN, the residue was individually mutated to alanine (E131A), leucine (E131L), or glutamine (E131Q).

Each hetN allele was introduced into the native locus and assessed for function by determining the heterocyst frequency and pattern following nitrogen step-down. By 48 h following nitrogen step-down (N−), the ΔhetN phenotype is most pronounced. At this time, the wild type produced 9.5% ± 0.3% heterocysts, while the ΔhetN mutant (UHM150) yielded 16.2% ± 0.2% heterocysts (Table 1). Strains harboring E131A (UHM352) and E131L (UHM353) alleles of hetN produced 13.6% ± 0.6% and 15.0% ± 0.6% heterocysts after 48 h of N−, respectively (Table 1). In contrast to strains harboring E131A and E131L mutations, a strain containing the E131Q allele of hetN (UHM354) produced 10.3% ± 0.1% heterocysts after 48 h of N−. The heterocyst percentages produced by UHM352, UHM353, and UHM354 were significantly different from those of the wild type and UHM150, as indicated by a t test (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). Despite the intermediate percentage of heterocysts produced, both UHM352 and UHM353 displayed an Mch phenotype, similarly to UHM150, while the wild type did not (Table 1). Strain UHM354 did not produce an Mch phenotype at any time but instead displayed a small yet significant decrease in the number of vegetative cells separating heterocysts (9.1 ± 0.3) after 48 h of N− compared to the wild type (11.5 ± 0.3; P < 0.002). Taken together, the increased heterocyst percentages and potential to form Mch suggest that E131 is required for the normal inhibitory function of HetN as it is in PatS.

TABLE 1.

Patterns of heterocysts produced by strains of Anabaenaa

| Strain (genotype) | Time following N− (h) | Mean % heterocysts ± SD | Mean no. of vegetative cells ± SEM | Avg % heterocyst occurrence ± SD (single, double, and multiple contiguous heterocysts) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 24 | 9.1 ± 0.3 | 10.3 ± 0.5 | 96 ± 1.7, 4 ± 1.7 |

| 48 | 9.5 ± 0.3 | 11.5 ± 0.3 | 96.7 ± 1.5, 3.3 ± 1.5 | |

| 72 | 8.9 ± 0.2 | 12.7 ± 0.4 | 95.3 ± 0.6, 6.7 ± 0.6 | |

| UHM150 (ΔhetN) | 24 | 9.5 ± 0.5 | 10.4 ± 0.3 | 88.3 ± 3.8, 10.7 ± 2.1, 1 ± 1.7 |

| 48 | 16.2 ± 0.2 | 5.9 ± 0.2 | 41.7 ± 2.1, 33.3 ± 4.0, 25 ± 4.4 | |

| 72 | 16.1 ± 0.1 | 6.1 ± 0.5 | 29 ± 1, 29.11 ± 2.1, 42 ± 2.5 | |

| UHM114 (ΔpatS) | 24 | 21.3 ± 3.1 | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 51.6 ± 2.5, 40.8 ± 2.3, 7.7 ± 3.6 |

| 48 | 18.1 ± 2.4 | 4.5 ± 0.3 | 56.1 ± 7.6, 39.6 ± 8.1, 6.3 ± 3.6 | |

| 72 | 15.9 ± 1.8 | 5.9 ± 1.1 | 61.7 ± 0.7, 33.1 ± 1.8, 5.2 ± 2.1 | |

| UHM328 [ΔhetN(M1L)] | 24 | 9.7 ± 0.2 | 10.6 ± 1.2 | 93.3 ± 1.5, 6.7 ± 1.5 |

| 48 | 9.3 ± 0.2 | 11.6 ± 0.1 | 94.3 ± 2.1, 5.4 ± 1.5, 0.3 ± 0.6 | |

| 72 | 9.3 ± 0.4 | 11.3 ± 0.3 | 95 ± 1.7, 5 ± 1.7 | |

| UHM345 [ΔhetN(M119L)] | 24 | 10 ± 0.2 | 8.8 ± 0.4 | 82 ± 1, 14 ± 1, 4 ± 1 |

| 48 | 14.3 ± 0.3 | 7 ± 0.5 | 70.7 ± 3.1, 20.3 ± 2.3, 9 ± 3.5 | |

| 72 | 15.3 ± 0.6 | 6.4 ± 0.2 | 70 ± 1, 19.7 ± 3.5, 10.3 ± 3.1 | |

| UHM346 [ΔhetN(M129L/M130L)] | 24 | 10.2 ± 0.2 | 9.2 ± 0.3 | 95 ± 1.7, 5 ± 1.7 |

| 48 | 10 ± 0.6 | 9.7 ± 0.1 | 91 ± 0.6, 8.7 ± 0.6, 0.3 ± 1 | |

| 72 | 9.9 ± 0.5 | 10.5 ± 0.5 | 93 ± 1, 7 ± 1 | |

| UHM356 [ΔhetN(M1L,M119L)] | 24 | 9.2 ± 0.9 | 11.2 ± 0.7 | 93.3 ± 2.5, 6.7 ± 2.5 |

| 48 | 15.2 ± 1.1 | 6.2 ± 0.1 | 50.3 ± 3.8, 36.7 ± 3.2, 13 ± 2.7 | |

| 72 | 15 ± 0.6 | 6.4 ± 0.2 | 49.7 ± 3.5, 36.3 ± 4.6, 14 ± 2.7 | |

| UHM347 [ΔhetN(M1L,M129L/M130L)] | 24 | 10.3 ± 0.3 | 8.7 ± 0.2 | 95.3 ± 0.6, 4.7 ± 0.6 |

| 48 | 10.1 ± 0.3 | 9.4 ± 0.5 | 93 ± 1, 7 ± 1 | |

| 72 | 10.2 ± 0.4 | 10 ± 0.3 | 94 ± 1, 5.7 ± 1.2, 0.3 ± 0.6 | |

| UHM348 [ΔhetN(M119L,M129L/M130L)] | 24 | 10.6 ± 0.2 | 9.4 ± 0.5 | 86.7 ± 3.5, 12 ± 2.7, 1.3 ± 1.2 |

| 48 | 15.7 ± 1.0 | 6.4 ± 0.2 | 61.3 ± 3.2, 26.7 ± 0.6, 12 ± 3.6 | |

| 72 | 16.7 ± 1.1 | 6.5 ± 0.4 | 49 ± 7, 30 ± 2, 21 ± 5.2 | |

| UHM349 [ΔhetN(M1L,M119L,M129L/M130L)] | 24 | 10.9 ± 0.2 | 9.6 ± 0.1 | 82.3 ± 2.1, 14.7 ± 1.5, 3 ± 1 |

| 48 | 16.8 ± 0.7 | 5.9 ± 0.5 | 39 ± 3, 34.7 ± 6.1, 26.3 ± 4.7 | |

| 72 | 17.7 ± 0.5 | 5 ± 0.5 | 39.7 ± 2.1, 29.3 ± 3.8, 31 ± 4.6 | |

| UHM362 {ΔhetN(M1L,V64V[GTG to GTT],M129L/M130L)} | 24 | 9.3 ± 0.1 | 10.9 ± 0.3 | 97.7 ± 1.2, 2.3 ± 1.2 |

| 48 | 10.1 ± 0.3 | 9.1 ± 0.3 | 94.7 ± 2.1, 5.3 ± 2.1 | |

| 72 | 9.6 ± 0.2 | 9.2 ± 0.3 | 93 ± 1.7, 7 ± 1.7 | |

| UHM352 [ΔhetN(E131A)] | 24 | 9.3 ± 0.6 | 10.8 ± 0.5 | 96.3 ± 0.6, 3.7 ± 0.6 |

| 48 | 13.6 ± 0.6 | 7 ± 0.5 | 63.3 ± 9.3, 25 ± 7.9, 11.7 ± 1.5 | |

| 72 | 15.5 ± 1.2 | 6.6 ± 0.3 | 47.7 ± 1.2, 32 ± 3.6, 20.3 ± 4.5 | |

| UHM353 [ΔhetN(E131L)] | 24 | 10.7 ± 1.0 | 8.5 ± 0.8 | 91.7 ± 4.6, 7.7 ± 4.2, 0.7 ± 1.2 |

| 48 | 15 ± 0.6 | 6.5 ± 0.5 | 65.7 ± 4.6, 24.7 ± 7.6, 9.7 ± 3.1 | |

| 72 | 15.9 ± 0.8 | 5.8 ± 0.3 | 55.3 ± 2.5, 32 ± 1, 12.7 ± 2.1 | |

| UHM354 [ΔhetN(E131Q)] | 24 | 8.7 ± 0.7 | 11.8 ± 0.4 | 98 ± 1, 2 ± 1 |

| 48 | 10.3 ± 0.1 | 9.1 ± 0.3 | 97.7 ± 1.5, 2.3 ± 1.5 | |

| 72 | 10.7 ± 0.3 | 8.3 ± 0.2 | 93.7 ± 1.5, 6.3 ± 1.5 | |

| UHM357 (ΔhetN::patS) | 24 | 9.3 ± 0.8 | 10.6 ± 0.1 | 88.2 ± 3.5, 11.8 ± 3.5 |

| 48 | 11.4 ± 0.4 | 8.4 ± 0.3 | 56.3 ± 4.0, 17.4 ± 6.7, 7.3 ± 3.5 | |

| 72 | 11.13 ± 0.6 | 7.5 ± 0.9 | 52.3 ± 4.0, 18.3 ± 6.7, 10.4 ± 3.5 | |

| UHM358 (ΔpatS::hetN) | 24 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | ||

| 48 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | |||

| 72 | 3.2 ± 0.4 |

At the indicated times following nitrogen step-down, 500 cells were counted in triplicate, and total heterocysts are presented as means ± standard deviations. For heterocyst occurrences, the presence of single, double, or multiple contiguous heterocysts was determined for 300 heterocysts in triplicate and is presented as the average percentage ± standard deviation. The vegetative cells between heterocysts were counted for 300 intervals and are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of the mean.

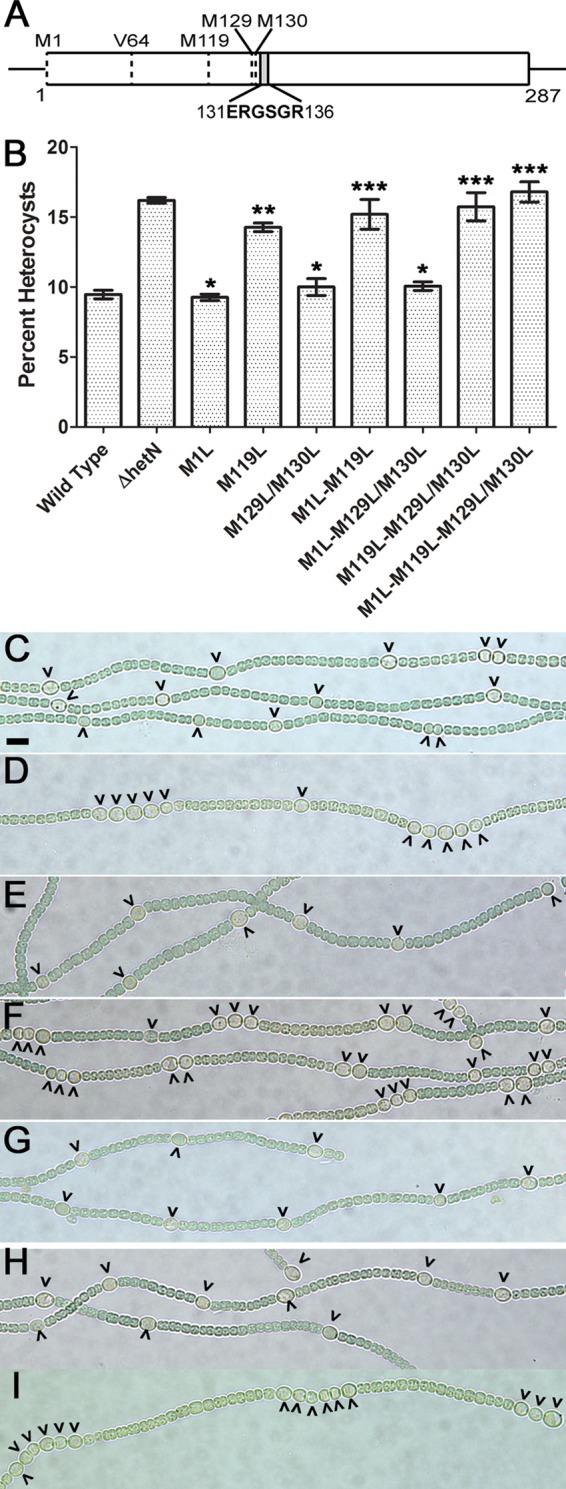

Methionine 119 of HetN is required for proper differentiation.

HetN can be divided into four domains based on hydrophobicity, but only the N-terminal hydrophilic domain harboring the ERGSGR motif is required for inhibition (19). Four methionine residues and one valine residue, encoded by the translational initiation codon GTG, are present within the N-terminal region upstream of the ERGSGR motif. While the exact nature of HetN inhibitory activity remains uncertain, previous work indicates that the full-length HetN protein does not move from cell to cell away from the source (23). If HetN itself constitutes the substance from which the inhibitory signal is derived, this implies that either multiple sizes of HetN protein are produced or HetN is processed posttranslationally. Based on the presence of up to five translational start sites upstream of the ERGSGR motif, it is possible that HetN-mediated inhibitory activity is produced from one of several start sites. An in silico analysis of the coding region upstream of the ERGSGR motif predicted that M1 and M119 are likely translational start sites, while V64 and M129/M130 are not predicted to initiate translation frequently (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). To determine which translational start site(s) is required to produce HetN-mediated inhibitory activity, each possible start codon in the N-terminal hydrophilic domain was inactivated individually and in combination, and the alleles were assessed for their ability to maintain a proper pattern of heterocysts when reintroduced into the native hetN locus.

Each methionine was mutated to leucine in every possible combination, except that M129 and M130 were always mutated together, as they are directly upstream of ERGSGR (amino acids 131 to 136) in HetN. After 48 h of N−, UHM328 [hetN(M1L)], UHM346 [hetN(M129L/M130L)], UHM347 [hetN(M1L,M129L/M130L)], and UHM362 {hetN(M1L,V64V[GTG to GTT],M129L/M130L)} differentiated 9.3% ± 0.2%, 10.0 ± 0.6%, 10.1% ± 0.3%, and 10.1% ± 0.3% of heterocysts, respectively (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Compared to the wild type (9.5% ± 0.3%) and UHM150 (16.2% ± 0.2%), the heterocyst percentages produced by UHM328, UHM346, UHM347, and UHM362 were not significantly different from that produced by the wild type but were significantly different from that produced by UHM150 (Table S3). UHM328, UHM346, UHM347, and UHM362 also did not produce an Mch phenotype (Table 1). These results suggest that the M1, M129, M130, and V64 residues are not required for proper HetN inhibitory function and heterocyst pattern maintenance.

FIG 1.

Alleles of hetN encoding M119L substitutions result in an Mch phenotype similar to that of a ΔhetN strain. (A) Schematic depicting the positions of potential start codons (M1, M119, M129/130, and V64, encoded by a GTG codon) and the ERGSGR motif in the hetN coding region. (B) Heterocyst percentages for the wild-type and ΔhetN strains as well as strains with the indicated chromosomal mutations. Data are presented as the averages of results from three replicates. Error bars represent standard deviations. Statistical significance was calculated by a t test with a P value of <0.05 (*, different from the ΔhetN strain and not different from the wild type; **, different from both the ΔhetN and wild-type strains; ***, different from the wild type and not different from the ΔhetN strain). (C to I) Bright-field images of the wild type (C), UHM150 (ΔhetN) (D), UHM328 [hetN(M1L)] (E), UHM345 [hetN(M119L)] (F), UHM346 [hetN(M129L/M130L)] (G), UHM347 [hetN(M1L,M129L/M130L)] (H), and UHM349 [hetN(M1L,M119L,M129L/M130L)] (I). Micrographs were taken 48 h after the removal of combined nitrogen. Carets indicate heterocysts. Bar in panel C, 10 μm.

In contrast to the above-described mutants, any allele containing a mutated M119 residue differentiated supernumerary heterocysts. Strains UHM345 [hetN(M119L)], UHM348 [hetN(M119L,M129L/M130L)], UHM349 [hetN(M1L,M119L,M129L/M130L)], and UHM356 [hetN(M1L,M119L)] differentiated 14.3% ± 0.3%, 15.7% ± 1.0%, 16.8% ± 0.7%, and 15.2% ± 1.1% of heterocysts, respectively, after 48 h of N− (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Compared to the wild type and UHM150, the percentages of heterocysts produced by UHM348, UHM349, and UHM356 were significantly different from that produced by the wild type but were not significantly different from that produced by UHM150 (Table S3). While the heterocyst percentage produced by UHM345 was significantly different from those produced by both the wild type and UHM150, it was more similar to that produced by UHM150 than to that produced by the wild type. All four mutant strains, UHM345, UHM348, UHM349, and UHM356, produced an Mch phenotype (Fig. 1 and Table 1). These data show a stark contrast between alleles that function like the wild type and those that are inactive and result in a ΔhetN phenotype, specifically via the formation of Mch and an increased heterocyst percentage. Taken together, these results suggest that M119 is required for proper HetN inhibitory function and may represent a translational start site.

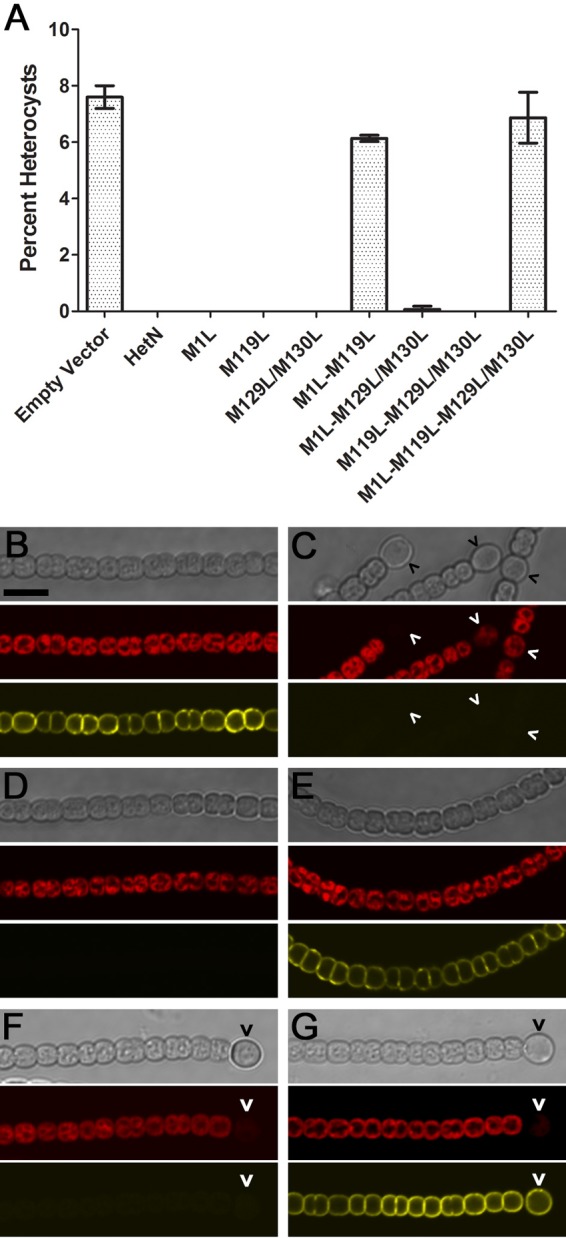

The hetN(M119L) allele produces a protein that localizes to the cell membrane.

When amino acids are mutated individually or in combination, it is possible that any resulting impairments in protein activity are caused by either the alteration of active regions required for function or destabilization of the protein structure leading to degradation. It is therefore possible that the results presented above, which indicated that alleles harboring the hetN(M119L) mutation were nonfunctional, were due to unforeseen changes in the protein structure rather than mutation of a translational start site. Such misfolded proteins are usually degraded by the cell and would present the same phenotype as a nonfunctional but properly folded allele. To verify that the hetN(M119L) mutation described above resulted in the production of proteins that display the characteristics of HetN, rather than producing misfolded and degraded variants, mutant alleles of hetN were translationally fused to yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) and assessed for both fluorescence localization in a pattern analogous to that of HetN-YFP and inhibition of heterocyst differentiation (19, 22, 23). Each of the following hetN alleles was fused to YFP and introduced on a multicopy plasmid into the wild type and UHM163, which contains hetR(R250K) at the native hetR locus and forms heterocysts even when hetN is overexpressed: hetN(M1L), hetN(M119L), hetN(M129L/M130L), hetN(M1L,M119L), hetN(M1L,M129L/M130L), hetN(M119L,M129L/M130L), and hetN(M1L,M119L,M129L/M130L). The expression of the wild-type and mutant hetN alleles was controlled by the copper-inducible petE promoter in both the wild type and UHM163 and by the native hetN promoter in UHM163.

Following introduction into host strains, it was possible that different HetN-YFP fusion proteins would be produced and give rise to yellow fluorescence, which indicates the expected membrane localization of a stable protein, or that no fluorescence would be observed, indicating that the allele did not produce a stable, full-length fusion protein. Yellow fluorescence should be observed in either all cells of UHM163 when functional hetN alleles are expressed by PpetE or heterocysts alone when controlled by PhetN. Twenty-four hours following the removal of combined nitrogen (N−), UHM163 containing PpetE-hetN(M119L), PpetE-hetN(M129L/M130L), and PpetE-hetN(M119L,M129L/M130L) displayed YFP fluorescence in both vegetative and heterocyst cells along the inner membrane in a pattern similar to HetN-YFP fusion results reported previously (Fig. 2; see also Table S2 in the supplemental material) (19, 22). Under the same conditions, strains harboring any combination that included mutation of the M1 residue, PpetE-hetN(M1L), PpetE-hetN(M1L,M119L), PpetE-hetN(M1L,M129L/M130L), and PpetE-hetN(M1L,M119L,M129L/M130L), did not show detectable YFP fluorescence in any cell type (Fig. 2 and Table S2). The expression of the same hetN alleles from the native hetN promoter in UHM163 or the petE promoter resulted in detectable YFP; however, fluorescence was restricted exclusively to heterocysts when expressed by the native promoter (Fig. S2 and Table S2). These results suggest that the M1 residue is required for the presence of a detectable YFP fusion protein.

FIG 2.

The M1 and M119 residues of hetN are required for function and proper translation of a YFP fusion protein. (A) Heterocyst percentages for the wild-type strain carrying either pPJAV153 as an empty vector control or plasmids harboring the indicated hetN alleles expressed by the petE promoter 24 h after the removal of combined nitrogen. (B to G) The wild type (B to E) and strain UHM163, which contains hetR(R250K) at the native locus and forms heterocysts even when hetN is overexpressed (F and G), 24 h after the removal of combined nitrogen with the following plasmids: pAD135 containing PpetE-hetN-YFP (B), pAD131 containing PpetE-hetN(M1L,M119L)-YFP (C), pAD128 containing PpetE-hetN(M1L)-YFP (D), pAD129 containing PpetE-hetN(M119L)-YFP (E), pAD128 containing PpetE-hetN(M1L)-YFP (F), and pAD129 containing PpetE-hetN(M119L)-YFP (G). From top to bottom are bright-field images, red autofluorescence, and yellow fluorescence from HetN-YFP alleles. Carets indicate heterocysts. Bar in panel B, 10 μm.

While the production of a properly localized YFP fusion protein is a noteworthy characteristic, maintaining the ability to suppress heterocyst differentiation is also pertinent to hetN function. It is possible that the expression of the YFP fusion constructs described above either would suppress heterocyst differentiation in the wild type, indicative of a functional allele, or would allow differentiation, showing that the allele is nonfunctional. All hetN alleles were expressed from PpetE to ensure that they would be expressed in all cells along filaments (8). Furthermore, because none of the RGSGR motifs are altered, even a nonfunctional protein that is produced and degraded into smaller peptides could still be capable of inhibiting differentiation, as was previously suggested (24). After 24 h of N−, the wild type containing an empty vector control plasmid produced 7.6% ± 0.4% heterocysts and no detectable YFP. In contrast, the wild type harboring PpetE-hetN-yfp failed to produce heterocysts, and YFP fluorescence was observed primarily in the inner membrane in a pattern similar to that reported in previous work (Fig. 2 and Table S2) (19, 22, 23). All but two of the above-described constructs containing a hetN allele fused to YFP inhibited heterocyst differentiation in the wild type. Only plasmids expressing PpetE-hetN(M1L,M119L)-yfp and PpetE-hetN(M1L,M119L,M129L/M130L)-yfp allowed significant heterocyst differentiation in the wild type, producing 6.1% ± 0.1% and 6.9% ± 0.9% heterocysts, respectively, and lacked detectable YFP fluorescence (Fig. 2 and Table S2). These results suggest that there may be separable functionalities within HetN: the M1 residue was required to produce an observable YFP fusion protein, but, like the data for hetN alleles integrated into the chromosome presented above, the M119 residue was required to suppress heterocyst differentiation when the alleles were overexpressed.

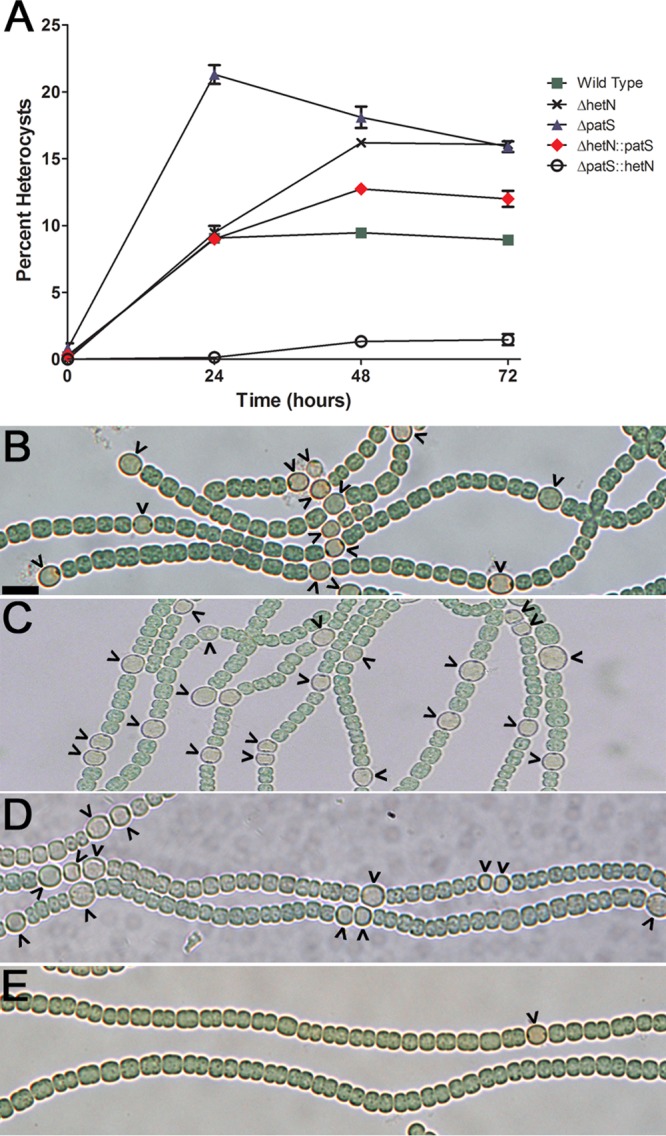

PatS and HetN are not functionally redundant.

PatS and HetN are the primary inhibitors responsible for de novo pattern formation and then pattern maintenance within Anabaena. Both proteins harbor the conserved ERGSGR motif that interacts directly with HetR, they are produced by source cells, and they each have activity that diffuses laterally. However, the hetN coding region is much larger than that of patS, patS is expressed early in differentiation while hetN is expressed primarily by mature heterocysts, and patS is expressed at a much higher level than hetN (13, 15–18, 25–27). Previous bioinformatic analyses have shown that patS homologs harboring an RGSGR motif are widely distributed throughout filamentous cyanobacteria (28). While hetN homologs are common among many cyanobacterial lineages, only five strains encode an RGSGR motif (22). It has been hypothesized that patS is the evolutionary predecessor and that the use of hetN in lateral inhibition may be a relatively new occurrence in cellular differentiation. Recent work indicated differing roles for the hetC gene, which is also thought to be involved in lateral inhibition (29), and that evolutionary divergence of this gene has occurred among several isolates of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 (30). Due to their similarities, and the possibility of evolutionary divergence in hetN function among cyanobacteria, as has been shown for hetC, it is possible that there is some functional redundancy between the two proteins. To determine whether hetN and patS are functionally redundant, strains in which the coding region of patS was replaced by the coding region of hetN and vice versa were created, and heterocyst differentiation was measured (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). In both of these strains, the native copy of the unaltered gene was maintained (e.g., PhetN-hetN was present at the native locus, and PpatS-hetN was expressed from the patS locus). If these genes are functionally redundant, swapping their loci should not greatly alter the percentages of heterocysts produced.

Strains UHM358 (ΔpatS::hetN) and UHM357 (ΔhetN::patS) were created, and their ability to differentiate heterocysts was determined 24 and 48 h after the removal of combined nitrogen (N−). After 24 h, the wild type and UHM114 (ΔpatS) produced 9.1% ± 0.3% and 21.3% ± 3.1% heterocysts, respectively, while UHM358 produced 0.3% ± 0.2% heterocysts (Fig. 3 and Table 1). When hetN replaced patS in UHM358, heterocyst differentiation did not exceed ∼3% for the duration of the experiment, which indicates that the expression of hetN at levels comparable to those of patS is sufficient to inhibit differentiation. After 48 h of N−, the wild type and UHM150 (ΔhetN) produced 9.5% ± 0.3% and 16.2% ± 0.2% heterocysts, respectively, while UHM357 produced 11.4% ± 0.4% heterocysts (Fig. 3 and Table 1). When patS was controlled by the hetN promoter in UHM357, an increased but intermediate number of heterocysts was formed, but Mch was observed. It is likely that the expression of patS and hetN has been optimized for these genes and that driving patS or hetN by the other promoter results in differences in expression that give rise to these phenotypes. These results indicate that hetN and patS are not functionally redundant due to the strongly inhibitory influence of hetN in the patS locus and the decrease in inhibition by patS in the hetN locus.

FIG 3.

Proper positioning of patS and hetN in the genome is required for their function in heterocyst differentiation. (A) Heterocyst percentages from 500 cells were determined in triplicate various times after nitrogen step-down for the wild-type, ΔhetN, ΔpatS, ΔhetN::patS, and ΔpatS::hetN strains and are presented as averages ± standard deviations. (B to E) Bright-field micrographs of the wild-type (B), ΔpatS (UHM114) (C), ΔhetN::patS (UHM357) (D), and ΔpatS::hetN (UHM358) (E) strains. Micrographs were taken either 24 h (B, C, and E) or 48 h (D) after the removal of combined nitrogen. Carets indicate heterocysts. Bar in panel B, 10 μm.

DISCUSSION

The proper placement of differentiated cells is paramount to the development and function of multicellular organisms. In all multicellular developmental systems studied, biological patterns are created and often rely on graded responses from opposing signals. In the Anabaena system, heterocyst positioning is initially defined by the interaction of HetR and PatS, and this pattern is maintained through successive generations by the function of HetN (3). This biological pattern of differentiated cells facilitates the optimized movement of fixed nitrogen and carbon throughout the filament, which allows continued growth during times of nitrogen starvation. In this work, we showed that, like PatS, the glutamate in the ERGSGR motif is required for proper HetN function (20). Additionally, HetN and PatS are not functionally redundant, because replacing the hetN coding region with the patS coding region and vice versa did not recapitulate a wild-type pattern of heterocysts. The data presented here also indicate that two translational start sites may be utilized to produce HetN for pattern maintenance.

In the chromosome, hetN encodes a 287-amino-acid protein annotated as a ketoacyl reductase, which has been shown to have some functionality in this regard (31). To date, studies of mutations in hetN have primarily investigated the size of the gene necessary to produce inhibitory activity, which has soundly demonstrated that the RGSGR motif is required for HetN function (19, 22). Both an initial study that mutated the RGSGR motif and subsequent work that mutated the entire ERGSGR motif showed that this motif is required for heterocyst inhibition. A study designed to determine the amino acids required for PatS activity and the size of the inhibitory peptide in the cell showed that the conserved glutamate in the ERGSGR motif alone is required for optimal PatS function (20). This is also consistent with in vitro work demonstrating that the binding affinity of ERGSGR for HetR is roughly 30 times higher than that of RGSGR (14). The work presented here builds on the observation that the ERGSGR motif is required for HetN function and shows that the conserved glutamate is specifically necessary for HetN function in a manner equivalent to that for the glutamate of PatS. These findings indicate that the HetN and PatS inhibitors may act in a similar mechanistic manner.

The results presented here point to two possible translational start sites for HetN at M1 and M119. When alleles mutant for the five possible start codons were reintroduced into the native hetN locus, only those harboring M119 mutations failed to maintain the normal heterocyst pattern and allowed the formation of Mch. When hetN alleles with M119 mutations translationally fused to YFP were expressed from a plasmid, fluorescence localized to the inner membrane in a manner similar to that of a native HetN-YFP fusion protein, suggesting that M119 is required for inhibitory signal production but not necessarily localization. Mutation of M1, however, resulted in alleles with wild-type inhibitory function, but this did not produce any membrane-localized YFP fluorescence, suggesting that M1 is required for localization but not inhibitory signal production. Together, these results indicate that two different sizes of HetN may be produced: one that is full length and localizes to the inner membrane of Anabaena cells but does not contribute the majority of inhibitory activity and one that initiates from M119, may localize to the membrane but does not result in the production of a complete fluorescent fusion protein, and is the main contributor of inhibitory activity.

It is possible to argue against this hypothesis by asserting that even hetN alleles lacking M119 were capable of halting differentiation when overexpressed in every cell in the filament. Previous work has shown that the overexpression of any protein harboring an RGSGR sequence in every cell in the filament, including the unannotated orf77, will abrogate differentiation (24). This is a nonspecific response to the increased concentration of the RGSGR motif in cells, even from proteins not involved in differentiation, rather than a specific response to a developmentally regulated inhibitor. The difference between assessing fluorescence from protein fusions and the ability of the protein to inhibit differentiation reveals two separate HetN functionalities, consistent with the existence of two different translational start sites for HetN. This realization explains several phenomena associated with previously reported HetN results.

In previous work, HetN-YFP was isolated from Anabaena cells, and the size was determined by Western blotting using an anti-YFP antibody (23). That analysis was conducted to determine whether HetN was posttranslationally modified and a smaller peptide was passed between cells as the active portion of HetN. It was possible that several band sizes would have been visualized, particularly those of full-length HetN-YFP and a smaller C-terminally processed portion of HetN-YFP; however, only full-length HetN-YFP was detected. Visualization of only the full-length protein makes sense in light of the above-described findings. Given the observation that the truncated HetN-YFP protein produced from an M119 start site failed to yield observable fluorescence (Fig. 2), it is unlikely that this truncated form would be present in a sufficient abundance to be detected by an anti-YFP antibody. The use of multiple start sites also provides a reason why the HetN-YFP fusion protein was never observed to travel from cell to cell, but the inhibitory signal continued to propagate laterally. The possibility of multiple start sites would allow HetN to function both as a ketoacyl reductase and as an inhibitory signal without requiring complicated posttranslational machinery. Indeed, a lipidomic analysis comparing the wild type and a ΔhetN mutant lacking this ketoacyl reductase functionality has not been conducted but would determine the role of HetN in Anabaena lipid metabolism.

The finding that an M1L mutation results in the lack of HetN-YFP-mediated fluorescence is very much in line with previous findings regarding the functional regions of HetN. Previous work indicated that the N-terminal region of HetN represents a hydrophobic domain that may act as a leader peptide (19, 22). The creation of a HetN-YFP translational fusion to an allele lacking residues 2 to 46 (hetNΔ2–46) resulted in the production of a protein that did not properly localize to the cell periphery and lacked observable yellow fluorescence (19). The overexpression of the hetNΔ2–46 allele halted heterocyst differentiation, and expression from the native locus produced a wild-type developmental phenotype; both of these results indicate that this allele was functional. The hetN(M1L) allele presented in this work presumably would fail to translate the hydrophobic leader peptide domain, which could impair its membrane localization and yield a phenotype similar to that of the hetNΔ2–46—YFP fusion. It was originally suggested that the posttranslational processing of HetN created a truncated peptide lacking YFP that could be transferred between cells and was responsible for HetN-mediated inhibitory activity. It is alternatively possible that premature translational stopping produces a short peptide that is the source of HetN-mediated inhibitory activity. The second possibility of a short peptide produced from the M119 translational start site was advanced previously and would result in a product with a size similar to the functional size of PatS needed to achieve lateral inhibition (22). Previous results have also indicated that mutations in sepJ and hetC influenced the movement of the hetN inhibitory signal but not that of patS (23, 29). It is possible that the multiple potential sizes of HetN interact with the cell pole machinery or septal channels differently than does PatS. These differences in protein size could also provide some basis for why patS and hetN are not functionally redundant. The potential of two translational start sites for HetN may provide the information necessary to define the size and functional nature of HetN required for inhibition and fulfill the majority of the criteria to define it as a morphogen in this model system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The growth of Escherichia coli and wild-type Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 and its derivatives, concentrations of antibiotics, and the induction of heterocysts in medium lacking a source of combined nitrogen were described previously (32, 33). Growth medium containing 6 mM ammonia as a nitrogen source was prepared as described previously and used to grow strains prior to the induction of heterocyst differentiation (26). Heterocyst percentages; frequencies of single contiguous heterocysts, double contiguous heterocysts, and higher numbers of contiguous heterocysts; and the mean vegetative cell intervals between heterocysts were determined as described previously (29). Expression from the copper-inducible petE promoter was induced with the addition of copper to a final concentration of 2 μM (8). Plasmids were introduced into Anabaena strains by conjugation from E. coli as described previously (34).

Plasmid and strain construction.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 2. The primers used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The integrity of all PCR-derived constructs was verified by sequencing. Details regarding plasmid creation can be found in the supplemental material. Replacement of the coding regions of hetN or patS with different hetN alleles or the coding region of patS was accomplished by allelic exchange as described previously (18, 32, 35). The following plasmids were used to introduce altered hetN alleles at the native hetN locus in UHM150: pOR101 for UHM328, pOR102 for UHM345, pOR103 for UHM346, pOR104 for UHM356, pOR105 for UHM347, pOR106 for UHM348, pOR107 for UHM349, pOR115 for UHM352, pOR116 for UHM353, and pPJAV369 for UHM354. The coding region of hetN was replaced with the coding region of patS at the hetN locus with plasmid pPJAV348 to create UHM357. The coding region of patS was replaced with the coding region of hetN at the patS locus with plasmid pPJAV349 to create UHM358. Strains with mutations in the hetN and patS genes were verified by PCR with primer set patSfor and patSrev and primer set up-hetN-F and down-hetN-R, respectively, which anneal outside the regions used to make the mutations.

TABLE 2.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s)a | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Anabaena strains | ||

| PCC 7120 | Wild type | Pasteur Culture Collection |

| UHM114 | ΔpatS | 32 |

| UHM150 | ΔhetN | 19 |

| UHM163 | ΔhetR(R250K) | 14 |

| UHM328 | ΔhetN(M1L) | This study |

| UHM345 | ΔhetN(M119L) | This study |

| UHM346 | ΔhetN(M129L/M130L) | This study |

| UHM347 | ΔhetN(M1L,M129L/M130L) | This study |

| UHM348 | ΔhetN(M119L,M129L/M130L) | This study |

| UHM349 | ΔhetN(M1L,M119L,M129L/M130L) | This study |

| UHM352 | ΔhetN(E131A) | This study |

| UHM353 | ΔhetN(E131L) | This study |

| UHM354 | ΔhetN(E131Q) | This study |

| UHM356 | ΔhetN(M1L,M119L) | This study |

| UHM357 | patS replacing hetN in the hetN locus | This study |

| UHM358 | hetN replacing patS in the patS locus | This study |

| UHM362 | ΔhetN(M1L,V64V[GTG to GTT],M129L/M130L) | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pAM504 | Shuttle vector for replication in E. coli and Anabaena; Kmr Nmr | 38 |

| pDR320 | pAM504 with PpetE-hetN | 12 |

| pDR382 | pRL277 to introduce hetN into the native locus | 19 |

| pPJAV153 | pAM504 with PpetE-YFP | 23 |

| pPJAV213 | pAM504 with PpetE | 27 |

| pRL277 | Suicide vector; Spr Smr | 39 |

| pAD120 | pAM504 with PhetN-hetN(M1L)-YFP | This study |

| pAD121 | pAM504 with PhetN-hetN(M119L)-YFP | This study |

| pAD122 | pAM504 with PhetN-hetN(M129L/M130L)-YFP | This study |

| pAD123 | pAM504 with PhetN-hetN(M1L,M119L)-YFP | This study |

| pAD124 | pAM504 with PhetN-hetN(M1L,M129L/M130L)-YFP | This study |

| pAD125 | pAM504 with PhetN-hetN(M119L,M129L/M130L)-YFP | This study |

| pAD126 | pAM504 with PhetN-hetN(M1L,M119L,M129L/M130L)-YFP | This study |

| pAD127 | pAM504 with PhetN-hetN-YFP | This study |

| pAD128 | pAM504 with PpetE-hetN(M1L)-YFP | This study |

| pAD129 | pAM504 with PpetE-hetN(M119L)-YFP | This study |

| pAD130 | pAM504 with PpetE-hetN(M129L/M130L)-YFP | This study |

| pAD131 | pAM504 with PpetE-hetN(M1L,M119L)-YFP | This study |

| pAD132 | pAM504 with PpetE-hetN(M1L,M129L/M130L)-YFP | This study |

| pAD133 | pAM504 with PpetE-hetN(M119L,M129L/M130L)-YFP | This study |

| pAD134 | pAM504 with PpetE-hetN(M1L,M119L,M129L/M130L)-YFP | This study |

| pAD135 | pAM504 with PpetE-hetN-YFP | This study |

| pAHB174 | pRL277 to make UHM362 | This study |

| pOR101 | pRL277 to make UHM328 | This study |

| pOR102 | pRL277 to make UHM345 | This study |

| pOR103 | pRL277 to make UHM346 | This study |

| pOR104 | pRL277 to make UHM356 | This study |

| pOR105 | pRL277 to make UHM347 | This study |

| pOR106 | pRL277 to make UHM348 | This study |

| pOR107 | pRL277 to make UHM349 | This study |

| pOR108 | pAM504 with PpetE-hetN(M1L) | This study |

| pOR109 | pAM504 with PpetE-hetN(M119L) | This study |

| pOR110 | pAM504 with PpetE-hetN(M129L/M130L) | This study |

| pOR111 | pAM504 with PpetE-hetN(M1L,M119L) | This study |

| pOR112 | pAM504 with PpetE-hetN(M1L,M129L/M130L) | This study |

| pOR113 | pAM504 with PpetE-hetN(M119L,M129L/M130L) | This study |

| pOR114 | pAM504 with PpetE-hetN(M1L,M119L,M129L/M130L) | This study |

| pOR115 | pRL277 to make UHM352 | This study |

| pOR116 | pRL277 to make UHM353 | This study |

| pPJAV348 | pRL277 to make UHM357 | This study |

| pPJAV349 | pRL277 to make UHM358 | This study |

| pPJAV369 | pRL277 to make UHM354 | This study |

Kmr, kanamycin resistance; Nmr, neomycin resistance; Spr, spectinomycin resistance; Smr, streptomycin resistance.

Microscopy and prediction of ribosomal binding sites.

Photomicroscopy was routinely conducted as described previously (32). Confocal microscopy was performed as described previously (19). The location and relative strength of ribosomal binding sites were predicted by using RBS Calculator v2.0 (36, 37). Statistical analysis was conducted by using GraphPad Prism software.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Sean Callahan (University of Hawaii at Manoa) for guidance, resources, and feedback, Dale Droge and Nancy Presuhn (Dakota State University) for thoughtful comments, insight, and support, and Andrew Burger (University of Hawaii at Manoa) for technical assistance in plasmid creation.

This work was supported by NSF-PRFB award 1103610 (to L.M.C.), an Illinois Wesleyan artistic and scholarly development grant (to L.M.C.), a Dakota State University Arts and Sciences Faculty research grant (to P.V.), and a Dakota State University faculty research initiative grant (to P.V.).

We declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00220-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wolk CP. 1996. Heterocyst formation. Annu Rev Genet 30:59–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.30.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar K, Mella-Herrera RA, Golden JW. 2010. Cyanobacterial heterocysts. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2:a000315. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muro-Pastor AM, Hess WR. 2012. Heterocyst differentiation: from single mutants to global approaches. Trends Microbiol 20:548–557. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turing A. 1952. The chemical basis of morphogenesis. Philos Trans R Soc Ser B 237:37–72. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1952.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gierer A, Meinhardt H. 1972. A theory of biological pattern formation. Kybernetik 12:30–39. doi: 10.1007/BF00289234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meinhardt H. 2008. Models of biological pattern formation: from elementary steps to the organization of embryonic axes. Curr Top Dev Biol 81:1–63. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(07)81001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buikema WJ, Haselkorn R. 1991. Characterization of a gene controlling heterocyst development in the cyanobacterium Anabaena 7120. Genes Dev 5:321–330. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buikema WJ, Haselkorn R. 2001. Expression of the Anabaena hetR gene from a copper-regulated promoter leads to heterocyst differentiation under repressing conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:2729–2734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051624898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Black TA, Cai Y, Wolk CP. 1993. Spatial expression and autoregulation of hetR, a gene involved in the control of heterocyst development in Anabaena. Mol Microbiol 9:77–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang X, Dong Y, Zhao J. 2004. HetR homodimer is a DNA-binding protein required for heterocyst differentiation, and the DNA-binding activity is inhibited by PatS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:4848–4853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400429101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim Y, Ye Z, Joachimiak G, Videau P, Young J, Hurd K, Callahan SM, Gornicki P, Zhao J, Haselkorn R, Joachimiak A. 2013. Structures of complexes comprised of Fischerella transcription factor HetR with Anabaena DNA targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:E1716–E1723. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305971110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Risser DD, Callahan SM. 2009. Genetic and cytological evidence that heterocyst patterning is regulated by inhibitor gradients that promote activator decay. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:19884–19888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909152106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoon H-S, Golden JW. 1998. Heterocyst pattern formation controlled by a diffusible peptide. Science 282:935–938. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5390.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feldmann EA, Ni S, Sahu ID, Mishler CH, Risser DD, Murakami JL, Tom SK, McCarrick RM, Lorigan GA, Tolbert BS, Callahan SM, Kennedy MA. 2011. Evidence for direct binding between HetR from Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 and PatS-5. Biochemistry 50:9212–9224. doi: 10.1021/bi201226e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoon H-S, Golden JW. 2001. PatS and products of nitrogen fixation control heterocyst pattern. J Bacteriol 183:2605–2613. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.8.2605-2613.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Black TA, Wolk CP. 1994. Analysis of a Het− mutation in Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 implicates a secondary metabolite in the regulation of heterocyst spacing. J Bacteriol 176:2282–2292. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.8.2282-2292.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bauer CC, Ramaswamy KS, Endley S, Scappino LA, Golden JW, Haselkorn R. 1997. Suppression of heterocyst differentiation in Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 by a cosmid carrying wild-type genes encoding enzymes for fatty acid synthesis. FEMS Microbiol Lett 151:23–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Callahan SM, Buikema WJ. 2001. The role of HetN in maintenance of the heterocyst pattern in Anabaena sp. PCC 7120. Mol Microbiol 40:941–950. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higa KC, Rajagopalan R, Risser DD, Rivers OS, Tom SK, Videau P, Callahan SM. 2012. The RGSGR amino acid motif of the intercellular signaling protein, HetN, is required for patterning of heterocysts in Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. Mol Microbiol 83:682–693. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corrales-Guerrero L, Mariscal V, Flores E, Herrero A. 2013. Functional dissection and evidence for intercellular transfer of the heterocyst-differentiation PatS morphogen. Mol Microbiol 88:1093–1105. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feldmann EA, Ni S, Sahu ID, Mishler CH, Levengood JD, Kushnir Y, McCarrick RM, Lorigan GA, Tolbert BS, Callahan SM, Kennedy MA. 2012. Differential binding between PatS C-terminal peptide fragments and HetR from Anabaena sp. PCC 7120. Biochemistry 51:2436–2442. doi: 10.1021/bi300228n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corrales-Guerrero L, Mariscal V, Nürnberg DJ, Elhai J, Mullineaux CW, Flores E, Herrero A. 2014. Subcellular localization and clues for the function of the HetN factor influencing heterocyst distribution in Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J Bacteriol 196:3452–3460. doi: 10.1128/JB.01922-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rivers OS, Videau P, Callahan SM. 2014. Mutation of sepJ reduces the intercellular signal range of a hetN-dependent paracrine signal, but not of a patS-dependent signal, in the filamentous cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. Mol Microbiol 94:1260–1271. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu X, Liu D, Lee MH, Golden JW. 2004. patS minigenes inhibit heterocyst development of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. J Bacteriol 186:6422–6429. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.19.6422-6429.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ehira S, Ohmori M. 2006. NrrA, a nitrogen-responsive response regulator facilitates heterocyst development in the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. Mol Microbiol 59:1692–1703. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitschke J, Vioque A, Haas F, Hess WR, Muro-Pastor AM. 2011. Dynamics of transcriptional start site selection during nitrogen stress-induced cell differentiation in Anabaena sp. PCC7120. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:20130–20135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112724108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Videau P, Oshiro RT, Cozy LM, Callahan SM. 2014. Transcriptional dynamics of developmental genes assessed with an FMN-dependent fluorophore in mature heterocysts of Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. Microbiology 160:1874–1881. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.078352-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang JY, Chen WL, Zhang CC. 2009. hetR and patS, two genes necessary for heterocyst pattern formation, are widespread in filamentous nonheterocyst-forming cyanobacteria. Microbiology 155:1418–1426. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.027540-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Videau P, Rivers OS, Higa KC, Callahan SM. 2015. ABC transporter required for intercellular transfer of developmental signals in a heterocystous cyanobacterium. J Bacteriol 197:2685–2693. doi: 10.1128/JB.00304-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y, Gao Y, Li C, Gao H, Zhang CC, Xu X. 23 April 2018. Three substrains of the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 display divergence in genomic sequences and hetC function. J Bacteriol doi: 10.1128/JB.00076-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu J, Chen WL. 2009. Characterization of HetN, a protein involved in heterocyst differentiation in the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. FEMS Microbiol Lett 297:17–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borthakur PB, Orozco CC, Young-Robbins SS, Haselkorn R, Callahan SM. 2005. Inactivation of patS and hetN causes lethal levels of heterocyst differentiation in the filamentous cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC 7120. Mol Microbiol 57:111–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higa KC, Callahan SM. 2010. Ectopic expression of hetP can partially bypass the need for hetR in heterocyst differentiation by Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120. Mol Microbiol 77:562–574. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Elhai J, Wolk CP. 1988. Conjugal transfer of DNA to cyanobacteria. Methods Enzymol 167:747–754. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)67086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Orozco CC, Risser DD, Callahan SM. 2006. Epistasis analysis of four genes from Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 suggests a connection between PatA and PatS in heterocyst pattern formation. J Bacteriol 188:1808–1816. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.5.1808-1816.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salis HM, Mirsky EA, Voigt CA. 2009. Automated design of synthetic ribosome binding sites to control protein expression. Nat Biotechnol 27:946–950. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Espah Borujeni A, Channarasappa AS, Salis HM. 2014. Translation rate is controlled by coupled trade-offs between site accessibility, selective RNA unfolding and sliding at upstream standby sites. Nucleic Acids Res 42:2646–2659. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wei T-F, Ramasubramanian R, Golden JW. 1994. Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 ntcA gene required for growth on nitrate and heterocyst development. J Bacteriol 176:4473–4482. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.15.4473-4482.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cai Y, Wolk CP. 1990. Use of a conditionally lethal gene in Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 to select for double recombinants and to entrap insertion sequences. J Bacteriol 172:3138–3145. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.3138-3145.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.