Abstract

Determining the neural factors contributing to compulsive behaviors such as alcohol-use disorders (AUDs) has become a significant focus of current preclinical research. Comparison of phenotypic differences across genetically distinct mouse strains provides one approach to identify molecular and genetic factors contributing to compulsive-like behaviors. Here we examine a rodent assay for punished ethanol self-administration in four widely used inbred strains known to differ on ethanol-related behaviors: C57BL/6J (B6), DBA/2J (D2), 129S1/SvImJ (S1), and BALB/cJ (BALB). Mice were trained in an operant task (FR1) to reliably lever-press for 10% ethanol using a sucrose-fading procedure. Once trained, mice received a punishment session in which lever pressing resulted in alternating ethanol reward and footshock, followed by tests to probe the effects of punishment on ethanol self-administration. Results indicated significant strain differences in training performance and punished attenuation of ethanol self-administration. S1 and BALB showed robust attenuation of ethanol self-administration after punishment, whereas behavior in B6 was attenuated only when the punishment and probe tests were conducted in the same contexts. By contrast, D2 were insensitive to punishment regardless of context, despite receiving more shocks during punishment and exhibiting normal footshock reactivity. Additionally, B6, but not D2, reduced operant self-administration when ethanol was devalued with a bitter tastant. B6 and D2 showed devaluation of sucrose self-administration, and punished suppression of sucrose seeking was context dependent in both the strains. While previous studies have demonstrated avoidance of ethanol in D2, particularly when ethanol is orally available from a bottle, current findings suggest this strain may exhibit heightened compulsive-like self-administration of ethanol, although there are credible alternative explanations of the phenotype of this strain. In sum, these findings offer a foundation for future studies examining the neural and genetic factors underlying AUDs.

Keywords: Alcohol, Mouse, Punishment, Addiction, Hippocampus, Amygdala

1. Introduction

Alcohol-use disorders (AUDs) are often characterized by persistent drinking despite negative consequences (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Determining the neural factors contributing to such behaviors has become a significant focus of current preclinical research (Everitt et al., 2008; Koob & Volkow, 2010; Vengeliene, Celerier, Chaskiel, Penzo, & Spanagel, 2009). One potentially useful approach in this regard involves assaying ethanol self-administration after punishment (Hopf & Lesscher, 2014; Radke et al., 2015; Radwanska & Kaczmarek, 2012; Seif et al., 2013). For instance, comparing punished ethanol self-administration across genetically distinct mouse strains offers a means to identify brain regions, molecular pathways, and genetic factors contributing to ethanol self-administration in the face of aversive outcomes.

Four widely studied inbred mouse strains, C57BL/6J (B6), DBA/2J (D2), 129S1/SvImJ (S1), and BALB/cJ (BALB), have been shown to show disparities in neural function and anatomy (Andolina, Puglisi-Allegra, & Ventura, 2015) that may contribute to differences in learning (Holmes, Wrenn, Harris, Thayer, & Crawley, 2002; Lederle et al., 2011; Owen, Logue, Rasmussen, & Wehner, 1997; Paylor, Baskall, & Wehner, 1993), stress responsivity (Graybeal et al., 2014; Lattal & Maughan, 2012; Moy et al., 2007; Mozhui et al., 2010), and ethanol-related behaviors (Belknap, Crabbe, & Young, 1993; Boyce-Rustay, Janos, & Holmes, 2008; Chesler et al., 2012; Crabbe, 1983; Debrouse et al., 2013; Elmer, Meisch, & George, 1987a; Elmer, Meisch, & George, 1987b; Elmer, Meisch, Goldberg, & George, 1988; Fish et al., 2010; Ford, Steele, McCracken, Finn, & Grant, 2013; Palachick et al., 2008; Rhodes et al., 2007; Rodgers & McClearn, 1962; Yoneyama, Crabbe, Ford, Murillo, & Finn, 2008). Of particular note, a now classic observation is that D2 exhibit reduced ethanol drinking and preference compared to B6 in two-bottle choice tests (Belknap et al., 1993; Boyce-Rustay et al., 2008; Crabbe, 1983; Rhodes et al., 2007; Rodgers & McClearn, 1962; Yoneyama et al., 2008), along with evidence that ethanol is a less effective reinforcer for D2 than B6 (Risinger, Brown, Doan, & Oakes, 1998). These findings have led to conceptualization of these two mouse strains as high- (B6) and low- (D2) ethanol preferring.

However, a number of recent observations have clouded the distinction between D2 and B6. D2 mice show stronger conditioned place preference (CPP) (Cunningham & Noble, 1992; Cunningham, Niehus, Malott, & Prather, 1992; Gremel, Gabriel, & Cunningham, 2006; Risinger, Malott, Riley, & Cunningham, 1992) and locomotor (Crabbe, 1983; Phillips, Dickinson, & Burkhart-Kasch, 1994; Rose, Calipari, Mathews, & Jones, 2013) responses to ethanol injections, and D2 < B6 differences in ethanol self-administration are attenuated when ethanol is delivered intragastrically or intravenously (Fidler et al., 2012, 2011; Grahame & Cunningham, 1997) or adulterated with certain tastants (e.g., monosodium glutamate) (McCool & Chappell, 2014). These findings suggest that taste aversion may at least partially account for lower two-bottle ethanol drinking in the D2 strain. They also raise interesting questions about how mouse strains, and D2 and B6 in particular, that have been characterized for their ethanol-related phenotypes in traditional behavioral assays would perform on measures posited to be more relevant to the addicted state, such as punished ethanol self-administration.

In the current study, we first compared the B6 and D2, along with S1 and BALB, strains on an operant measure of responding for ethanol after punishment, recently developed in our laboratory (Radke, Jury, et al., 2015; Radke, Nakazawa, & Holmes, 2015), based on prior studies of ethanol and cocaine self-administration in rats (Belin, Berson, Balado, Piazza, & Deroche-Gamonet, 2011; Marchant, Khuc, Pickens, Bonci, & Shaham, 2013; Pelloux, Murray, & Everitt, 2013, 2015). Additional experiments were then performed to further characterize differences in punished ethanol responding between B6 and D2 by testing for strain differences in sensitivity to ethanol devaluation and contextual cues. The results obtained offer novel insight into punished ethanol self-administration in mice and provide a foundation for exploiting these strains to delineate the neural and genetic basis of this behavior.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects

Male S1, BALB, B6, and D2 mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). These strains were chosen based on their extensive use in neuroscience, their inclusion in the Mouse Phenome Project (www.jax.org/phenome) (Bogue & Grubb, 2004), and their use in our previous analyses of strain differences in behavioral phenotypes of active sensitivity and ethanol self-administration (Boyce-Rustay et al., 2008; Chen & Holmes, 2009; Lederle et al., 2011).

Mice were 9–10 weeks old at the start of the experiments. They were housed in pairs in a temperature (72 ± 5 °F) and humidity (45 ± 15%) controlled vivarium, under a 12-h light/dark cycle (lights on at 0630 h). Over approximately 1 week prior to behavioral training, mice were reduced to 85% of their free-feeding body weight, which was maintained through completion of behavioral testing. All experimental procedures carried out were approved by the NIAAA Animal Care and Use Committee and followed the NIH guidelines outlined in Using Animals in Intramural Research, as well as the local Animal Care and Use Committees. See Fig. S1 for a schematic depiction of the sequence of tests used.

2.2. Operant training

Behavioral training was conducted in 21.6 × 17.8 × 12.7 cm operant chambers housed within sound- and light-attenuating enclosures (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT, USA). Grid floors of the chambers were fully covered with Plexiglas® for all sessions except the punishment session, during which it was removed in order to administer footshock. Pellet and liquid dispensers delivered rewards into a receptacle at one end of the chamber, which was located in the middle of two ultra-sensitive response levers (5 cm from the receptacle). Speakers emitting a 3-kHz pure tone cue that signaled reward delivery were positioned above the levers. Med-PC software (Med Associates) controlled reward delivery and recorded lever presses.

Mice were initially trained to press one of the two levers (= ‘active lever’) to receive delivery of a 14-mg food pellet reward (40-min sessions on a fixed-ratio 1 [FR1]/continuous schedule of reinforcement). Presses on the second, inactive lever had no programmed consequences. Once responding was established (at least 35 active-lever presses in a 40-min session), mice were trained to respond for ethanol using a sucrose-fade procedure (Radke, Jury, et al., 2015), whereby the food pellet reward was replaced with a 10-μL liquid reward delivered over 0.3 s. The liquid solutions were 10% sucrose, 10% sucrose + 10% ethanol, 5% sucrose + 10% ethanol, and 10% ethanol, with training proceeding on a given solution until criterion was met (= consistent active-lever pressing with less than 20% inter-session variation on three consecutive sessions). The rate of active-lever pressing (per minute) for each reward type is reported as the mean average during the three sessions at criterion.

2.3. Punished responding for ethanol

Following training, there was a 40-min punishment session in which active-lever pressing alternated between being rewarded (10% ethanol) and being coincident with a 0.3-mA, 0.75-s footshock. Punishment sessions took place in the same room where the mice had received their training, using shock-equipped operant chambers that were identical to training chambers in all aspects other than having an exposed metal-rod floor due to removal of the Plexiglas® floor insert in order to deliver shock to the mouse. The number of shocks received during the punishment session was recorded. Post-punishment probe tests were conducted (using the procedure as pre-punishment training) on each of the 2 days following punishment, in the same operant chambers where training had occurred and with the Plexiglas® floor insert present. Three dependent variables were measured during the probe tests: 1) the per-minute rate of active-lever pressing, 2) the latency to first make an active-lever press, and 3) the vigor of active-lever pressing (= the maximum number of consecutive 1-min bins in which an active-lever press was made). These values were averaged over the two probe tests and compared with the average at pre-punishment criterion.

2.4. Ethanol devaluation

Beginning 24 h after probe testing, B6 and D2 were tested under the same procedures used for training until active-lever rates returned to pre-punishment levels (S1 and BALB were excluded from subsequent experiments because their performance did not differ from B6 during punished responding for ethanol). There were then an additional five daily sessions (testing procedures again equivalent to training) to ensure a reliable level of responding. Beginning on day 6, the ethanol solution was adulterated using the bitter compound, denatonium benzoate (DB) (Sigma Aldrich, Allentown, PA, USA) – previously shown to be avoided to an equal extent by B6 and D2 (Boughter, Raghow, Nelson, & Munger, 2005). Concentrations of DB increased daily from day 6 through day 11 as follows: 0.01, 0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, and 10 mM. Active-lever pressing at each concentration was calculated as percent change from non-devalued baseline.

2.5. Footshock reactivity

Five days after devaluation testing, mice were placed in a 27 × 27 × 11 cm chamber (Med Associates) with a metal-rod floor, and after a 60-s baseline period, exposed to five 0.3-mA, 0.75-s footshocks delivered randomly, once every 90 s on average. Shock responsivity was measured automatically by Med Associates VideoFreeze System as movement during shock delivery.

2.6. Training, punishment, and devaluation of responding for sucrose

A test-naïve cohort of B6 and D2 were tested as above, but with the exception that the reward was 10% sucrose throughout operant training, punishment, and (DB-adulterated sucrose) devaluation.

2.7. Punished responding for ethanol (punishment = probe context)

A test-naïve cohort of B6 and D2 were trained using the same procedures as described above, but with the exception that the probe tests were conducted in a context with the same fully exposed (as opposed to Plexiglas®-covered) grid floor as was present during the punishment session. The punishment/probe test chamber was also housed in a room different than the room used for training.

2.8. Statistical analyses

Strain comparisons were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVAs), followed by Tukey HSD post hoc tests using B6 mice as the reference to compare the other strains. Comparisons between B6 and D2 were analyzed using either two-way ANOVAs or Student’s t tests. The threshold for statistical significant was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Strain differences in training

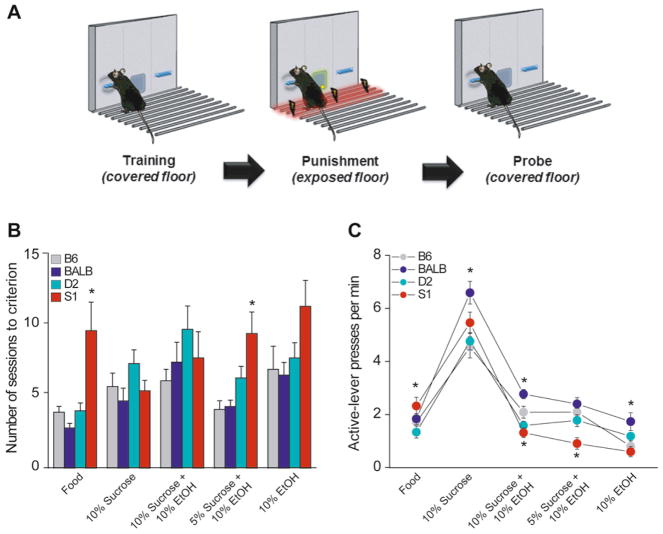

Strains significantly differed in the number of sessions to reach the training criterion for the food-pellet reward (F[3,42] = 8.81, p < 0.01). Post hoc tests showed that S1 took more sessions to attain criterion than B6, but neither BALB nor D2 differed from B6 (Fig. 1B). After reaching criterion, S1 made significantly more active-lever presses than B6 (F[3,42] = 5.16, p < 0.01, followed by post hoc test: p < 0.05) (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1. Strain differences in operant training.

(A) Plexiglas® flooring was removed only during punishment sessions to expose shock-grid flooring. (B) S1 required more sessions than B6 to attain criterion for food and for 5% sucrose + 10% ethanol. (C) S1 had a higher rate of active-lever pressing for food reward, but lower rates for all sucrose + ethanol reward mixes, as compared to B6. BALB had a higher rate of active-lever pressing for 10% sucrose, 10% sucrose + 10% ethanol and 10% ethanol, relative to B6. *p < 0.05 versus B6.

For liquid rewards, the number of sessions to reach criterion only differed significantly between strains at the 5% sucrose + 10% ethanol solution (F[3,42] = 6.846, p < 0.01); S1 took more sessions than B6 to reach criterion for this reward (post hoc test: p < 0.01) (Fig. 1B). There were significant strain differences in rates of active-lever pressing at each reward type: 10% sucrose (F[3,42] = 5.93, p < 0.01), 10% sucrose + 10% ethanol (F[3,42] = 16.34, p < 0.01), 5% sucrose + 10% ethanol (F[3,42] = 7.74, p < 0.01), and 10% ethanol only (F[3,42] = 5.06, p < 0.01). Post hoc tests showed that BALB pressed at a higher rate than B6 for every mix, except 5% sucrose + 10% ethanol, whereas S1 pressed at lower rates than B6 for the 10% sucrose + 10% ethanol and the 5% sucrose + 10% ethanol mixes (Fig. 1C). B6 and D2 did not differ on this measure for any reward type. The average doses of the 10% ethanol-alone reward attained (as indicated by the amount of liquid dispensed) differed between strains (B6: 1.09 ± 0.3, BALB: 2.58 ± 0.5, D2: 1.62 ± 0.1, and S1: 1.06 ± 0.2 g/kg ethanol).

3.2. Strain differences in punished responding for ethanol

There was a significant effect of strain for the number of shocks received during the punishment session (F[3,42] = 4.19, p < 0.05), due to D2 receiving more shocks than B6 (post hoc test: p < 0.05) (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2. Strain differences in responding for ethanol under punishment.

(A) D2 received more shocks during punishment than B6. BALB and S1, but not B6 or D2, had a lower rate of active-lever pressing (B), a longer latency to first press (C), and a reduction in the vigor of pressing (D) on post-punishment probe tests, relative to pre-punishment. *p < 0.05 versus B6, ‡p < 0.05, ‡‡p < 0.01 pre-punish versus punish.

On the punishment-probe tests, there was a significant (probe versus pre-punishment) session × strain interaction for the rate of active-lever pressing (F[3,39] = 5.10, p < 0.01). BALB and S1 had reduced rates on the probe tests, relative to pre-punishment (post hoc tests: p < 0.01), whereas D2 and B6 did not (Fig. 2B). There was a significant effect of session (F[1,43] = 9.83, p < 0.01) and strain (F[3,42] = 4.13, p < 0.05), but no interaction, for the latency to the first active-lever press during the probe tests. BALB and S1, but not D2 or B6, had significantly longer latencies on the probe tests, as compared to pre-punishment (post hoc tests: p < 0.05) (Fig. 2C). There was also a significant session × strain interaction for the vigor of active-lever pressing (F[3,39] = 4.05, p < 0.05); BALB and S1 reduced vigor during the probe tests, whereas D2 and B6 did not (Fig. 2D).

3.3. No strain differences in footshock reactivity

In response to pseudorandomly delivered footshocks at the same intensity as used for punishment, D2 and B6 did not significantly differ in the magnitude of their movement response (t[19] = 1.87, p = 0.08) (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3. Strain differences in footshock sensitivity and ethanol devaluation.

(A) D2 and B6 had similar footshock-reactivity scores. (B) Adulterating ethanol with denatonium benzoate (DB) reduced active-lever pressing in B6, but not D2. D2 pressed significantly more than B6 at the 3-mM and 10-mM DB concentrations. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 versus B6, #p < 0.05 concentration-dependent decrease.

3.4. Strain differences in ethanol devaluation

There was a significant interaction between strain and DB concentration (F[5,95] = 2.33, p < 0.05). B6, but not D2, showed a concentration-dependent decrease in responding such that, at the highest DB concentrations, active-lever press values were higher in D2 than B6 (post hoc tests: p < 0.05) (Fig. 3B).

3.5. No strain differences in training, punishment, and devaluation of responding for sucrose

During training, B6 and D2 did not differ in sessions to criterion or active-lever press rates for either food or sucrose (Fig. 4A and B). The strains also did not differ in the number of shocks received during the punishment session (Fig. 4C), or in the latency, rate, or vigor of active-lever responding during the probe tests (Fig. 4D–F).

Fig. 4. Strain differences in responding for sucrose.

During operant training, D2 and B6 did not differ in sessions to reach criterion (A) or rates of active-lever pressing (B) for either food or sucrose. (C) D2 and B6 did not differ in shocks received during punishment. Neither strain showed altered rates of active-lever pressing (D), latency to first lever press (E), or vigor of pressing (F) on punishment probes, relative to pre-punishment. (G) B6 and D2 exhibited a reduction in pressing for sucrose adulterated with denatonium benzoate (DB). #p < 0.05 concentration-dependent decrease.

In the sucrose-devaluation test, there was a significant concentration × strain interaction (F[5,60] = 4.58, p < 0.05) and a significant main effect of concentration (F[5,60] = 36.50 p < 0.01), but no effect of strain. Both strains reduced responding in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 4G).

3.6. Strain differences in punished responding for ethanol-tested mice (punishment = probe context)

During training, B6 and D2 did not differ in sessions to criterion (Fig. 5B or active-lever press rates (Fig. 5C) for any reward type. D2 received more shocks than B6 during the punishment session (t[11] = 4.60, p < 0.01) (Fig. 5D). B6 had reduced active-lever press rates on the probe tests, relative to pre-punishment (Fig. 5E), whereas D2 did not (strain × session interaction: F[1,11] = 6.58, p < 0.05, followed by planned post hoc tests: p < 0.01). Additionally, compared to pre-punishment, B6 had a higher latency to active-lever press (t[6] = 2.45, p < 0.05) and a reduction in response vigor (t[6] = 4.52, p < 0.05) during the punishment-probe, whereas D2 did not show a change in any of these variables (Fig. 5F and G).

Fig. 5. Strain differences in punished responding for ethanol tested in same context.

(A) Plexiglas® flooring was removed to expose grid flooring during both punishment and probe tests, which took place in a different room than training. D2 and B6 did not differ in sessions to reach criterion (B) or rates of active-lever pressing (C) for any reward. (D) D2 received more shocks than B6 during punishment. B6, but not D2, showed reduced rates of active-lever pressing (E), an increased latency to first press (F), and a decrease in the vigor of pressing (G) during punishment probe tests, as compared to pre-punishment. ***p < 0.001 versus B6, ‡p < 0.05, ‡‡p < 0.01 pre-punishment versus punishment.

4. Discussion

A major novel finding of the current study was that inbred mouse strains differed in punished responding for ethanol. Moreover, in the D2 and B6 strains, the effects of punishment were differentially modulated by context and extended to differences in sensitivity to ethanol devaluation.

Prior to punishment, the four mouse strains tested varied in the acquisition of reliable instrumental responding for a food reward and for various liquid ethanol and sucrose combinations, as evidenced by sessions to reach performance criterion and/or the rates of active-lever pressing after reaching criterion. As compared to B6, S1 was slower to reach criterion and responded at lower rates for some reward types. This difference was not due to gross learning or motoric effects in S1, because the strain responded at a higher rate for at least one reward type (food). Moreover, previous studies show that S1 mice exhibit good learning across a range of operant- and maze-based behavioral assays (Clapcote & Roder, 2004; Holmes et al., 2002; Merritt & Rhodes, 2015). Thus, the lesser responding for ethanol-containing solutions in S1 mice likely reflects the aversion to ethanol, whether straight or sweetened, that has been reported in this strain previously (Rhodes et al., 2007; Yoneyama et al., 2008).

Two of the other strains tested in the current study, BALB and D2, also displayed higher or no difference in responding for ethanol-containing solutions, relative to B6. This seemingly contradicts earlier re ports that these strains show aversion to ethanol (Elmer et al., 1987a, 1987b, 1988; Belknap et al., 1993; Boyce-Rustay et al., 2008; Crabbe, 1983; Hutsell & Newland, 2013; Rhodes et al., 2007; Rodgers & McClearn, 1962; Yoneyama et al., 2008). However, earlier operant-based studies have concluded that ethanol acts as a poor reinforcer in BALB (Elmer et al., 1987a, 1987b, 1988), suggesting the response rates observed in the current study may be unrelated to the reinforcing properties of ethanol in this strain. This brings up a more general point regarding the extent to which ethanol served as a strong reinforcer in any of the strains. The amount of ethanol consumed is much lower in mouse operant self-administration paradigms than, for example, two-bottle drinking, and even if response rates are very high, it is difficult to discern that responding is driven by ethanol as opposed to other stimuli. Additionally, we did not obtain measures of BECs or behavioral signs of intoxication after operant testing. Thus, we cannot exclude the possibility that ethanol reinforcement was the primary driver of operant self-administration.

A wealth of prior evidence has characterized D2 as ‘ethanol-avoiding’ and B6 as ‘ethanol-preferring’, mainly in two-bottle, but also in operant-based, settings (Belknap et al., 1993; Boyce-Rustay et al., 2008; Risinger et al., 1998; Rodgers & McClearn, 1962; Yoneyama et al., 2008). Indeed, these observations have led to the strains being adopted as progenitors of the BXD recombinant lines that have historically been a mainstay of neural and genetic studies of ethanol-related behaviors (Crabbe, Belknap, Buck, & Metten, 1994; Crabbe, Belknap, Mitchell, & Cranshaw, 1994; Phillips et al., 1994). The reasons for the lack of strain differences in responding for ethanol under these conditions remain to be determined. Contributing factors may be the use of food deprivation and/or sucrose fading; although, arguing against the latter possibility, previous studies have reported clear differences in ethanol seeking are still evident between B6 and D2 when a sucrose-fading procedure is used (Camarini & Hodge, 2004). It is also worth pointing out that clear-cut differences in ethanol self-administration between D2 and B6 are not evident in all experimental settings. For instance, avoidance in D2 is attenuated when ethanol is available through the intravenous or intragastric route (Fidler et al., 2012, 2011; Grahame & Cunningham, 1997) or orally when mixed with monosodium glutamate (McCool & Chappell, 2014). In addition, D2 show robust locomotor stimulation and CPP for intraperitoneally or intravenously administered ethanol (Crabbe, 1983; Cunningham et al., 1992; Cunningham & Noble, 1992; Grahame & Cunningham, 1997; Gremel et al., 2006; Phillips et al., 1994; Risinger et al., 1992; Rose et al., 2013). Thus, differences between B6 and D2 appear to vary as a function of the assay employed.

Against this background, a notable finding from the current study was that neither D2 nor B6 suppressed ethanol responding following a session of footshock punishment that was sufficient to robustly suppress responding in S1 and BALB. Punished suppression in S1 and BALB was not due to these strains making more approaches to the active lever during the punishment session and, as a result, accruing more press = punish associative experience. Rather, these data are consistent with heightened sensitivity to the effects of punishment on ethanol self-administration – an effect that may relate to the more persistent and generalizable fear, and the increased anxiety-related behavior shown by these strains in other tests (Belzung & Griebel, 2001; Camp et al., 2012, 2009; Crawley et al., 1997; Hefner et al., 2008; Lad et al., 2010; Moy et al., 2007; Norcross et al., 2008).

The absence of punished suppression of ethanol-responding in B6 under these conditions was surprising, given previous studies from our laboratory showing significant suppression of operant responding for ethanol (or food) in this genetic background strain (Radke, Jury, et al., 2015; Radke, Nakazawa, et al., 2015). We confirmed, however, that this lack of a punishment of effect in B6 extended to self-administration of a sucrose reward. We also identified a key procedural difference between this earlier work and the current study: the contexts used for the punishment session and post-punishment probe tests. Specifically, we found that B6 showed significant suppression of ethanol-responding (here and in Radke, Nakazawa, et al., 2015) when the probe and punishment contexts were the same, but that the insertion of a solid floor over the shock grid during the probe tests was a sufficient change in context to occlude the effect of punishment in B6. This indicates that floor texture is the principal factor gating the expression of the punishment effect in B6.

The significance of floor texture as the critical discriminative contextual feature in this task concurs with previous studies of conditioned context fear in rats (González, Quinn, & Fanselow, 2003). More pertinently, the importance of context fits well with the recent findings that the effects of punishment on operant ethanol self-administration in rats are also highly context-dependent (Bouton & Schepers, 2015; Marchant et al., 2013). One implication of our data is that other cues, notably including the reward lever itself, were not capable of supporting this behavior, at least within the procedural parameters we employed. In other words, it would appear that an instrumental contingency between the reward lever and punishment was either too weak to effectively suppress responding for reward, not established at all, or only expressed when coupled with the appropriate punished context (i.e., acts as an operant occasion setter [Holland, 1983; Skinner, 1938]). As such, this issue recasts how we might view punished suppression of ethanol seeking as relevant to compulsive behaviors in AUDs, which are more tightly defined as the continuation of behaviors directed at obtaining alcohol despite punishment.

Another interesting finding was that D2 failed to show punished suppression of ethanol responding even when the punishment and probe testing contexts were equivalent. One explanation of this finding is that this lack of contextual gating reflects impaired representation of contextual information in D2 mice. This would be consistent with reports of impaired contextual fear conditioning in D2 (André, Cordero, & Gould, 2012; Nie & Abel, 2001; Upchurch & Wehner, 1988); which some authors have attributed to hippocampal abnormalities in the strain (Fordyce, Bhat, Baraban, & Wehner, 1994; Heimrich, Schwegler, & Crusio, 1985; Nguyen, Abel, Kandel, & Bourtchouladze, 2000; Sunyer, An, Kang, Höger, & Lubec, 2009; Wehner, Sleight, & Upchurch, 1990). The current experiments however, cannot exclude the alternative interpretation that D2 are resistant to the effects of punishment, irrespective of context – perhaps due to a failure to learn the lever-shock contingency. Of note in this regard, D2 received more shocks than B6 during the punishment session. This difference was seen despite the strains showing similar reactivity to footshock – arguing against lesser pain perception in D2 and consistent with prior studies (Kazdoba, Del Vecchio, & Hyde, 2007; Patrono et al., 2015).

The possibility that D2 mice exhibit a punishment-resistant ethanol self-administration phenotype will require testing in future studies. This idea however, does fit with the recent observation that D2 are also relatively insensitive to footshock-punished chocolate consumption, as compared to B6 (Patrono et al., 2015). Another pertinent finding in the current study was that D2, in contrast to B6, maintained operant responding for ethanol adulterated with the bitter-tasting compound, denatonium benzoate (DB). This does not appear to be an artifact of altered D2 taste perception, because the two strains have been found to have equivalent taste sensitivity for the same concentrations of DB used here (Boughter et al., 2005), and both demonstrated clear and similar reductions in responding for DB-adulterated sucrose between the strains.

Also of note are prior studies demonstrating increased impulsive behavior in D2 mice on various operant-based tests, including delay discounting, go/no go, and the five-choice serial reaction time task (Gubner, Wilhelm, Phillips, & Mitchell, 2010; Helms, Reeves, & Mitchell, 2006; Loos et al., 2010; Patel, Stolerman, Asherson, & Sluyter, 2006; Pinkston & Lamb, 2011). There is growing evidence that impulsivity and compulsivity are related traits in rodents (Belin, Mar, Dalley, Robbins, & Everitt, 2008; Belin-Rauscent et al., 2015) and human patient populations (Brook, Brook, Zhang, & Koppel, 2010; Fernández-Serrano, Perales, Moreno-López, Pérez-García, & Verdejo-García, 2012; Lopez-Ibor, 1990; Wilens, 2007). In addition, in some but not all studies, D2 exhibit exaggerated responses to ethanol in the midbrain-striatal dopamine system, which is strongly implicated in both impulsivity and compulsivity (Brodie & Appel, 2000; Kapasova & Szumlinski, 2008; Zapata, Gonzales, & Shippenberg, 2006). The strain also has reduced midbrain-striatal dopamine D2 receptor expression (Carneiro et al., 2009; Patrono et al., 2015), which has been linked to increased risk for substance abuse (Belin, Belin-Rauscent, Everitt, & Dalley, 2016). These prior findings, taken together with the current results, raise the intriguing possibility that D2 could represent a model of heightened persistence in ethanol self-administration. As already noted, this hypothesis remains speculative in the absence of further study.

In conclusion, the results of the current study reveal differences between commonly used inbred mouse strains in a measure of punished ethanol self-administration. In addition, they show that this behavioral measure is gated by context in the B6 strain, while the D2 strain is unaffected by punishment regardless of context and also displays insensitivity to ethanol devaluation. These findings provide a valuable point from which to elucidate neural and genetic factors underlying addiction-related AUD traits.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Intramural Research Program.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.alcohol.2016.05.008.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2013. p. DSM-5. [Google Scholar]

- Andolina D, Puglisi-Allegra S, Ventura R. Strain-dependent differences in corticolimbic processing of aversive or rewarding stimuli. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience. 2015;8:207. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2014.00207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- André JM, Cordero KA, Gould TJ. Comparison of the performance of DBA/2 and C57BL/6 mice in transitive inference and foreground and background contextual fear conditioning. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2012;126:249–257. doi: 10.1037/a0027048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belin-Rauscent A, Daniel ML, Puaud M, Jupp B, Sawiak S, Howett D, et al. From impulses to maladaptive actions: The insula is a neurobiological gate for the development of compulsive behavior. Molecular Psychiatry. 2015;21:491–499. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belin D, Belin-Rauscent A, Everitt BJ, Dalley JW. In search of predictive endophenotypes in addiction: Insights from preclinical research. Genes, Brain, and Behavior. 2016;15:74–88. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belin D, Berson N, Balado E, Piazza PV, Deroche-Gamonet V. High-novelty-preference rats are predisposed to compulsive cocaine self-administration. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:569–579. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belin D, Mar AC, Dalley JW, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. High impulsivity predicts the switch to compulsive cocaine-taking. Science. 2008;320:1352–1355. doi: 10.1126/science.1158136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belknap JK, Crabbe JC, Young ER. Voluntary consumption of ethanol in 15 inbred mouse strains. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993;112:503–510. doi: 10.1007/BF02244901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belzung C, Griebel G. Measuring normal and pathological anxiety-like behaviour in mice: A review. Behavioural Brain Research. 2001;125:141–149. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00291-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogue MA, Grubb SC. The mouse phenome Project. Genetica. 2004;122:71–74. doi: 10.1007/s10709-004-1438-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boughter JD, Jr, Raghow S, Nelson TM, Munger SD. Inbred mouse strains C57BL/6J and DBA/2J vary in sensitivity to a subset of bitter stimuli. BMC Genetics. 2005;6:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-6-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, Schepers ST. Renewal after the punishment of free operant behavior. Journal of Experimental Psychology Animal Learning and Cognition. 2015;41:81–90. doi: 10.1037/xan0000051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce-Rustay JM, Janos AL, Holmes A. Effects of chronic swim stress on EtOH-related behaviors in C57BL/6J, DBA/2J and BALB/cByJ mice. Behavioural Brain Research. 2008;186:133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodie MS, Appel SB. Dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area of C57BL/6J and DBA/2J mice differ in sensitivity to ethanol excitation. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:1120–1124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook DW, Brook JS, Zhang C, Koppel J. Association between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adolescence and substance use disorders in adulthood. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2010;164:930–934. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camarini R, Hodge CW. Ethanol preexposure increases ethanol self-administration in C57BL/6J and DBA/2J mice. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 2004;79:623–632. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camp MC, Macpherson KP, Lederle L, Graybeal C, Gaburro S, Debrouse LM, et al. Genetic strain differences in learned fear inhibition associated with variation in neuroendocrine, autonomic, and amygdala dendritic phenotypes. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:1534–1547. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camp M, Norcross M, Whittle N, Feyder M, D’Hanis W, Yilmazer-Hanke D, et al. Impaired Pavlovian fear extinction is a common phenotype across genetic lineages of the 129 inbred mouse strain. Genes, Brain, and Behavior. 2009;8:744–752. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00519.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro AM, Airey DC, Thompson B, Zhu CB, Lu L, Chesler EJ, et al. Functional coding variation in recombinant inbred mouse lines reveals multiple serotonin transporter-associated phenotypes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:2047–2052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809449106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YC, Holmes A. Effects of topiramate and other anti-glutamatergic drugs on the acute intoxicating actions of ethanol in mice: Modulation by genetic strain and stress. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1454–1466. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesler EJ, Plitt A, Fisher D, Hurd B, Lederle L, Bubier JA, et al. Quantitative trait loci for sensitivity to ethanol intoxication in a C57BL/6J×129S1/SvImJ inbred mouse cross. Mammalian Genome. 2012;23:305–321. doi: 10.1007/s00335-012-9394-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapcote SJ, Roder JC. Survey of embryonic stem cell line source strains in the water maze reveals superior reversal learning of 129S6/SvEvTac mice. Behavioural Brain Research. 2004;152:35–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabbe JC. Sensitivity to ethanol in inbred mice: Genotypic correlations among several behavioral responses. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1983;97:280–289. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.97.2.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabbe JC, Belknap JK, Buck KJ, Metten P. Use of recombinant inbred strains for studying genetic determinants of responses to alcohol. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 1994a;2:67–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabbe JC, Belknap JK, Mitchell SR, Crawshaw LI. Quantitative trait loci mapping of genes that influence the sensitivity and tolerance to ethanol-induced hypothermia in BXD recombinant inbred mice. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1994b;269:184–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawley JN, Belknap JK, Collins A, Crabbe JC, Frankel W, Henderson N, et al. Behavioral phenotypes of inbred mouse strains: Implications and recommendations for molecular studies. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1997;132:107–124. doi: 10.1007/s002130050327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CL, Niehus DR, Malott DH, Prather LK. Genetic differences in the rewarding and activating effects of morphine and ethanol. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1992;107:385–393. doi: 10.1007/BF02245166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CL, Noble D. Conditioned activation induced by ethanol: Role in sensitization and conditioned place preference. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 1992;43:307–313. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(92)90673-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debrouse L, Hurd B, Kiselycznyk C, Plitt A, Todaro A, Mishina M, et al. Probing the modulation of acute ethanol intoxication by pharmacological manipulation of the NMDAR glycine co-agonist site. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37:223–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01922.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmer GI, Meisch RA, George FR. Differential concentration-response curves for oral ethanol self-administration in C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ mice. Alcohol. 1987a;4:63–68. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(87)90062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmer GI, Meisch RA, George FR. Mouse strain differences in operant self-administration of ethanol. Behavior Genetics. 1987b;17:439–451. doi: 10.1007/BF01073111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmer GI, Meisch RA, Goldberg SR, George FR. Fixed-ratio schedules of oral ethanol self-administration in inbred mouse strains. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1988;96:431–436. doi: 10.1007/BF02180019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BJ, Belin D, Economidou D, Pelloux Y, Dalley JW, Robbins TW. Review. Neural mechanisms underlying the vulnerability to develop compulsive drug-seeking habits and addiction. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series B, Biological Sciences. 2008;363:3125–3135. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Serrano MJ, Perales JC, Moreno-López L, Pérez-García M, Verdejo-García A. Neuropsychological profiling of impulsivity and compulsivity in cocaine dependent individuals. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012;219:673–683. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2485-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidler TL, Dion AM, Powers MS, Ramirez JJ, Mulgrew JA, Smitasin PJ, et al. Intragastric self-infusion of ethanol in high- and low-drinking mouse genotypes after passive ethanol exposure. Genes, Brain, and Behavior. 2011;10:264–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00664.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidler TL, Powers MS, Ramirez JJ, Crane A, Mulgrew J, Smitasin P, et al. Dependence induced increases in intragastric alcohol consumption in mice. Addiction Biology. 2012;17:13–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2011.00363.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish EW, Riday TT, McGuigan MM, Faccidomo S, Hodge CW, Malanga CJ. Alcohol, cocaine, and brain stimulation-reward in C57Bl6/J and DBA2/J mice. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34:81–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01069.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford MM, Steele AM, McCracken AD, Finn DA, Grant KA. The relationship between adjunctive drinking, blood ethanol concentration and plasma corticosterone across fixed-time intervals of food delivery in two inbred mouse strains. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:2598–2610. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fordyce DE, Bhat RV, Baraban JM, Wehner JM. Genetic and activity-dependent regulation of zif268 expression: Association with spatial learning. Hippocampus. 1994;4:559–568. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450040505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González F, Quinn JJ, Fanselow MS. Differential effects of adding and removing components of a context on the generalization of conditional freezing. Journal of Experimental Psychology Animal Behavior Processes. 2003;29:78–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grahame NJ, Cunningham CL. Intravenous ethanol self-administration in C57BL/6J and DBA/2J mice. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1997;21:56–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graybeal C, Bachu M, Mozhui K, Saksida LM, Bussey TJ, Sagalyn E, et al. Strains and stressors: An analysis of touchscreen learning in genetically diverse mouse strains. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87745. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gremel CM, Gabriel KI, Cunningham CL. Topiramate does not affect the acquisition or expression of ethanol conditioned place preference in DBA/2J or C57BL/6J mice. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006;30:783–790. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubner NR, Wilhelm CJ, Phillips TJ, Mitchell SH. Strain differences in behavioral inhibition in a Go/No-go task demonstrated using 15 inbred mouse strains. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34:1353–1362. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefner K, Whittle N, Juhasz J, Norcross M, Karlsson RM, Saksida LM, et al. Impaired fear extinction learning and cortico-amygdala circuit abnormalities in a common genetic mouse strain. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2008;28:8074–8085. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4904-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimrich B, Schwegler H, Crusio WE. Hippocampal variation between the inbred mouse strains C3H/HeJ and DBA/2: A quantitative-genetic analysis. Journal of Neurogenetics. 1985;2:389–401. doi: 10.3109/01677068509101425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms CM, Reeves JM, Mitchell SH. Impact of strain and D-amphetamine on impulsivity (delay discounting) in inbred mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;188:144–151. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0478-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland PC. Occasion setting in Pavlovian feature positive discriminations. In: Commons ML, Herrnstein RJ, Wagner AR, editors. Quantitative analysis of behavior: Discrimination processes. Ballinger; New York: 1983. pp. 183–206. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes A, Wrenn CC, Harris AP, Thayer KE, Crawley JN. Behavioral profiles of inbred strains on novel olfactory, spatial and emotional tests for reference memory in mice. Genes, Brain, and Behavior. 2002;1:55–69. doi: 10.1046/j.1601-1848.2001.00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopf FW, Lesscher HM. Rodent models for compulsive alcohol intake. Alcohol. 2014;48:253–264. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutsell BA, Newland MC. A quantitative analysis of the effects of qualitatively different reinforcers on fixed ratio responding in inbred strains of mice. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2013;101:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapasova Z, Szumlinski KK. Strain differences in alcohol-induced neurochemical plasticity: A role for accumbens glutamate in alcohol intake. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:617–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdoba TM, Del Vecchio RA, Hyde LA. Automated evaluation of sensitivity to foot shock in mice: Inbred strain differences and pharmacological validation. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2007;18:89–102. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3280ae6c7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:217–238. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lad HV, Liu L, Paya-Cano JL, Parsons MJ, Kember R, Fernandes C, et al. Behavioural battery testing: Evaluation and behavioural outcomes in 8 inbred mouse strains. Physiology & Behavior. 2010;99:301–316. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lattal KM, Maughan DK. A parametric analysis of factors affecting acquisition and extinction of contextual fear in C57BL/6 and DBA/2 mice. Behavioural Processes. 2012;90:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lederle L, Weber S, Wright T, Feyder M, Brigman JL, Crombag HS, et al. Reward-related behavioral paradigms for addiction research in the mouse: Performance of common inbred strains. PLoS One. 2011;6:e15536. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loos M, Staal J, Schoffelmeer AN, Smit AB, Spijker S, Pattij T. Inhibitory control and response latency differences between C57BL/6J and DBA/2J mice in a Go/No-Go and 5-choice serial reaction time task and strain-specific responsivity to amphetamine. Behavioural Brain Research. 2010;214:216–224. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Ibor JJ., Jr Impulse control in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A biopsychopathological approach. Progress in Neuro-psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 1990;14:709–718. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(90)90041-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchant NJ, Khuc TN, Pickens CL, Bonci A, Shaham Y. Context-induced relapse to alcohol seeking after punishment in a rat model. Biological Psychiatry. 2013;73:256–262. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCool BA, Chappell AM. Persistent enhancement of ethanol drinking following a monosodium glutamate-substitution procedure in C57BL6/J and DBA/2J mice. Alcohol. 2014;48:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merritt JR, Rhodes JS. Mouse genetic differences in voluntary wheel running, adult hippocampal neurogenesis and learning on the multi-strain-adapted plus water maze. Behavioural Brain Research. 2015;280:62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moy SS, Nadler JJ, Young NB, Perez A, Holloway LP, Barbaro RP, et al. Mouse behavioral tasks relevant to autism: Phenotypes of 10 inbred strains. Behavioural Brain Research. 2007;176:4–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozhui K, Karlsson RM, Kash TL, Ihne J, Norcross M, Patel S, et al. Strain differences in stress responsivity are associated with divergent amygdala gene expression and glutamate-mediated neuronal excitability. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30:5357–5367. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5017-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen PV, Abel T, Kandel ER, Bourtchouladze R. Strain-dependent differences in LTP and hippocampus-dependent memory in inbred mice. Learning & Memory. 2000;7:170–179. doi: 10.1101/lm.7.3.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie T, Abel T. Fear conditioning in inbred mouse strains: An analysis of the time course of memory. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2001;115:951–956. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.115.4.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norcross M, Mathur P, Enoch AJ, Karlsson RM, Brigman JL, Cameron HA, et al. Effects of adolescent fluoxetine treatment on fear-, anxiety- or stress-related behaviors in C57BL/6J or BALB/cJ mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;200:413–424. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1215-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen EH, Logue SF, Rasmussen DL, Wehner JM. Assessment of learning by the Morris water task and fear conditioning in inbred mouse strains and F1 hybrids: Implications of genetic background for single gene mutations and quantitative trait loci analyses. Neuroscience. 1997;80:1087–1099. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00165-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palachick B, Chen YC, Enoch AJ, Karlsson RM, Mishina M, Holmes A. Role of major NMDA or AMPA receptor subunits in MK-801 potentiation of ethanol intoxication. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:1479–1492. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00715.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S, Stolerman IP, Asherson P, Sluyter F. Attentional performance of C57BL/6 and DBA/2 mice in the 5-choice serial reaction time task. Behavioural Brain Research. 2006;170:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrono E, Di Segni M, Patella L, Andolina D, Valzania A, Latagliata EC, et al. When chocolate seeking becomes compulsion: Gene-environment interplay. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0120191. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paylor R, Baskall L, Wehner JM. Behavioral dissociations between C57BL/6 and DBA/2 mice on learning and memory tasks: A hippocampal-dysfunction hypothesis. Psychobiology. 1993;21:11–26. [Google Scholar]

- Pelloux Y, Murray JE, Everitt BJ. Differential roles of the prefrontal cortical subregions and basolateral amygdala in compulsive cocaine seeking and relapse after voluntary abstinence in rats. The European Journal of Neuroscience. 2013;38:3018–3026. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelloux Y, Murray JE, Everitt BJ. Differential vulnerability to the punishment of cocaine related behaviours: Effects of locus of punishment, cocaine taking history and alternative reinforcer availability. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2015;232:125–134. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3648-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips TJ, Dickinson S, Burkhart-Kasch S. Behavioral sensitization to drug stimulant effects in C57BL/6J and DBA/2J inbred mice. Behavioral Neuroscience. 1994;108:789–803. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.108.4.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinkston JW, Lamb RJ. Delay discounting in C57BL/6J and DBA/2J mice: Adolescent-limited and life-persistent patterns of impulsivity. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2011;125:194–201. doi: 10.1037/a0022919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radke AK, Jury NJ, Kocharian A, Marcinkiewcz CA, Lowery-Gionta EG, Pleil KE, et al. Chronic EtOH effects on putative measures of compulsive behavior in mice. Addiction Biology. 2015a doi: 10.1111/adb.12342. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Radke AK, Nakazawa K, Holmes A. Cortical GluN2B deletion attenuates punished suppression of food reward-seeking. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2015b;232:3753–3761. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-4033-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radwanska K, Kaczmarek L. Characterization of an alcohol addiction-prone phenotype in mice. Addiction Biology. 2012;17:601–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2011.00394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes JS, Ford MM, Yu CH, Brown LL, Finn DA, Garland T, Jr, et al. Mouse inbred strain differences in ethanol drinking to intoxication. Genes, Brain, and Behavior. 2007;6:1–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risinger FO, Brown MM, Doan AM, Oakes RA. Mouse strain differences in oral operant ethanol reinforcement under continuous access conditions. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1998;22:677–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb04311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risinger FO, Malott DH, Riley AL, Cunningham CL. Effect of Ro 15-4513 on ethanol-induced conditioned place preference. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 1992;43:97–102. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(92)90644-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers DA, McClearn GE. Mouse strain differences in preference for various concentrations of alcohol. Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1962;23:26–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JH, Calipari ES, Mathews TA, Jones SR. Greater ethanol-induced locomotor activation in DBA/2J versus C57BL/6J mice is not predicted by presynaptic striatal dopamine dynamics. PLoS One. 2013;8:e83852. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seif T, Chang SJ, Simms JA, Gibb SL, Dadgar J, Chen BT, et al. Cortical activation of accumbens hyperpolarization-active NMDARs mediates aversion-resistant alcohol intake. Nature Neuroscience. 2013;16:1094–1100. doi: 10.1038/nn.3445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF. The behavior of organisms. Appleton-Century; New York: 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Sunyer B, An G, Kang SU, Höger H, Lubec G. Strain-dependent hippocampal protein levels of GABA(B)-receptor subunit 2 and NMDA-receptor subunit 1. Neurochemistry International. 2009;55:253–256. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upchurch M, Wehner JM. DBA/2Ibg mice are incapable of cholinergically-based learning in the Morris water task. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 1988;29:325–329. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(88)90164-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vengeliene V, Celerier E, Chaskiel L, Penzo F, Spanagel R. Compulsive alcohol drinking in rodents. Addiction Biology. 2009;14:384–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehner JM, Sleight S, Upchurch M. Hippocampal protein kinase C activity is reduced in poor spatial learners. Brain Research. 1990;523:181–187. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91485-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens TE. The nature of the relationship between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and substance use. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2007;68(Suppl 11):4–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoneyama N, Crabbe JC, Ford MM, Murillo A, Finn DA. Voluntary ethanol consumption in 22 inbred mouse strains. Alcohol. 2008;42:149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapata A, Gonzales RA, Shippenberg TS. Repeated ethanol intoxication induces behavioral sensitization in the absence of a sensitized accumbens dopamine response in C57BL/6J and DBA/2J mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:396–405. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.