Abstract

Some of the limitations of fine needle aspiration (FNA) in the cytodiagnosis of lymphoma include problems encountered in differentiating reactive hyperplasia from low-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), lower cytodiagnostic accuracy for NHL with a follicular (nodular) pattern and nodular sclerosis type of classical Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), and overlapping morphological features between T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma (TCRBCL), anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), and HL. Immunocytochemistry may be of help in such situations. The B-cell lymphomas such as small lymphocytic lymphoma/CLL, follicular lymphoma (FL), mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), MALT lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma (BL), and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) have pan-B-cell markers (CD19, CD20, CD22, CD23, and CD79a). The FL (centrocytic), MCL, and MALT lymphoma can be differentiated with the use of a panel consisting of CD5, CD10, and CD23. In addition, FL is BCL2+ and MCL is BCL2+ as well as cyclin D1+. The DLBCL is BCL6+ in 60–90% cases. Besides pan B-cell marker, the immunocytochemical profile of BL includes CD10+, BCl6+, EBV±, and Ki67+ (100% cells). TCRBCL, a rare variant of DLBCL can be immunocytochemically differentiated from anaplastic large cell lymphoma (CD45+, CD30+, CD15‒, T±, B‒, EMA+, ALK1±) and classical HL (CD30+, CD15+, CD45‒, B‒, T‒, EMA‒). Unlike classical HL, the nodular lymphocytic predominant HL has a phenotype that includes LCA+, CD20+, CD79a+, CD15‒, and CD30‒. Whereas the immature neoplastic cells of T-lymphoblastic lymphoma (LBL) are CD3+, CD20‒, and Tdt+, the rarely encountered mature T-CLL/T-PLL are immunophenotypically CD3+, CD4+, CD5+, CD7+, CD8‒, CD20‒, CD23‒, and Tdt‒.

Keywords: Fine needle aspiration cytology, Hodgkin lymphoma, immunocytochemistry, non-Hodgkin lymphoma

INTRODUCTION

Histologically, malignant lymphomas are characterized by a homogeneous neoplastic cell population and a tumor growth pattern either of cohesive cellular aggregates called the follicular or nodular pattern, or of diffuse infiltration.[1] Immunologically, lymphomas are expanded clones of lymphocytic precursors or functional cell types (B- or T-cell), which appear to develop from a block or switch on (de-repression) of lymphocytic transformation. Genetically, in most lymphoid neoplasms antigen receptor gene rearrangement precedes transformation of lymphoid cells; as a result, all daughter cells derived from the malignant progenitor share the same antigen receptor gene configuration and sequence and synthesize identical antigen receptor proteins (either Ig or T-cell receptor); whereas B-cell neoplasms are positive for surface immunoglobulin (sIg+) and/or cytoplasmic immunoglobulin (cIg+), and express pan-B cell markers (CD19, CD20, CD22, and CD79α), T-cell neoplasms express T-cell markers such as CD2, CD3 (considered lineage specific), CD5, CD7, CD4, and CD8.[2]

The cytodiagnosis of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) depends upon finding a relatively monotonous population of lymphoid cells[3,4] and Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is diagnosed in smears on finding Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg (HRS) cells among reactive cell population which consists of lymphocytes, plasma cells, histiocytes, and eosinophils.[5,6] Some of the limitations of FNA in cytodiagnosis of lymphoma include problem encountered in differentiating reactive hyperplasia from low-grade NHL, lower cytodiagnostic accuracy of NHL with a follicular (nodular) pattern, and nodular sclerosis type of classical HL, and overlapping morphological features between T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma (TCRBCL), anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), and HL.[7] In order to overcome the diagnostic difficulties of lymphomas and their subtypes in FNA smears, immune-phenotyping is essential.

“WHO Classification of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Neoplasms,”[8] comprises nearly 100 subtypes of lymphoid neoplasms and their variants. The cytomorphology and ICC results of a few usual and unusual lymphoma subtypes, viz., CLL/small lymphocytic lymphoma including rare variants like T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia (T-PLL), follicular lymphoma (FL), mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), MALT lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) including T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma (THRBCL or TCRBCL), Burkitt lymphoma (BL), lymphoblastic lymphoma (LBL), ALCL, and HL, both nodular lymphocyte predominant (NLPHL) and classical type (CHL), are presented in this communication. Reference has been made mostly to the WHO monographs and a few journal articles for cytomorphological features and immunocyto/histochemical results.[7,8,9,10,11,12]

SMALL LYMPHOCYTIC NON-HODGKIN LYMPHOMA (CHRONIC LYMPHOCYTIC LEUKEMIA)

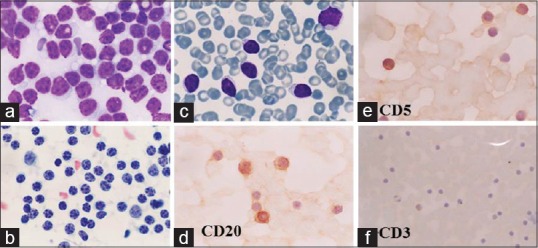

Most of the patients are elderly with generalized lymphadenopathy. The small lymphocytic lymphoma/CLL cells are invariably of B-cell lineage with following immuno-phenotype: CD3‒, CD5+, CD10‒, CD19+, CD20+ (low), CD22+, CD23+, CD43+, CD79a+, and Ig+ (low).[8] FNA smear from the lymph nodes show features of a small lymphocytic lymphoma with a monotonous population of lymphoid cells consistent with CLL;[13] positive reaction for CD20 and CD5 is observed in neoplastic cells in FNA smears and/or peripheral blood smear whenever there is evidence of leukemic infiltration [Figure 1]. T-cell CLL/T-prolymphocytic leukemia (T-PLL), which has an aggressive clinical course with a median survival of less than 1 year, account for less than 2% of all lympho-proliferative diseases and <5% of the total number of chronic lymphoproliferative disorders.[14,15] In a report on a rare case of T-PLL by Das et al.[16] FNA smears from cervical lymph node showed a monomorphic population of small lymphoid cells with a frequent hand-mirror cell configuration, coarse chromatin, and small but distinct nucleoli; immunocytochemically the lymphoid cells were CD3+, CD4+, CD5+, CD7+, CD8‒, CD20‒, CD23‒, and Tdt‒ [Figure 2].

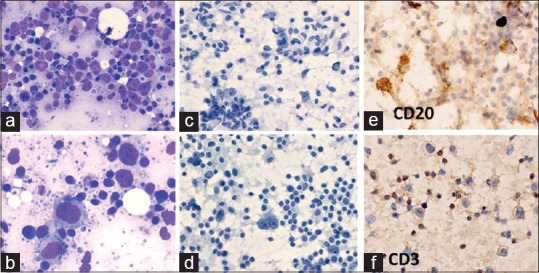

Figure 1.

FNA smears from the retro-auricular swelling (LN) and peripheral blood smear (PS) in a 58-year-old man, known to be suffering from CLL. Cytodiagnosis was NHL (small cell type)/CLL. ICC findings were CD20+, CD3–, and CD5+. (a, b) FNA smear from the cervical lymph node. (a) Monotonous lymphoid cell population, slightly larger than RBCs (MGG × 1000). (b) Clumping of chromatin is coarse (Pap × 1000). (cf) Peripheral blood smear. (c) CLL cells similar in morphology to lymph node aspirate (MGG × 1000). (d) CLL cells are positive for CD20 (×1000). (e) CLL cells are positive for CD5 (x1000). (f) CLL cells are CD3– (×400)

Figure 2.

T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia (T-PLL): A 92-year-old man presented with generalized lymphadenopathy. FNA cytodiagnosis: CLL. Total leukocyte count was 26 × 109/L. Direct smear was CD20–, CD23–, and CD3+. Cell block preparation: CD3+, CD4+, CD5+, CD7+, CD20–, CD8–, and Tdt–. (a) FNA smear from cervical lymph node shows small monomorphic neoplastic lymphoid cells, slightly larger than mature lymphocytes with scanty cytoplasm and small nucleoli (MGG × 1000). (b) FNA smears from axillary lymph node shows lymphoid cells with coarse chromatin and small nucleoli, some of them with hand-mirror configuration (Pap × 1000). (c) Cervical lymph node: occasional tumor cells were positive for CD20 (×1000). (d) axillary lymph node: most tumor cells were positive for CD3 (×1000). (e) Peripheral smear: small lymphocyte with lobulated/irregular nuclei (MGG × 1000). (f-h): Cell block of left cervical lymph node FNA showing positive reactions for (f): CD3 (×1000), (f): CD5 (×1000), and (h): CD7 (×1000)

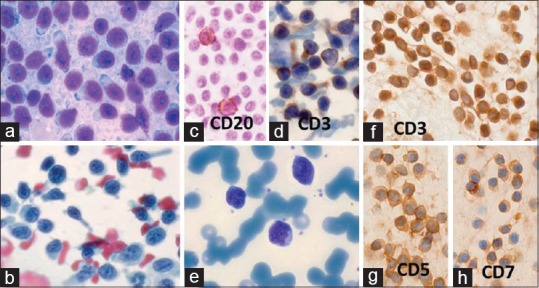

FOLLICULAR LYMPHOMAS

Middle-aged and older people are affected, and frequently present with generalized lymphadenopathy. Cytologically these cases could be centrocytic (CC), centroblastic (CB), or mixed centrocytic-centroblastic (CC-CB) type. The immunophenotype is Bcl2+, CD5‒, CD10±, CD19+, CD23±, and CD43‒ in over 80% cases.[17] Whereas the centrocytic lymphomas (NHL-CC) show a monotonous population of CD20 positive atypical, small- to medium-sized lymphoid cells with variably irregular, indented, or cleaved nuclei having moderately clumped to more dispersed chromatin and inconspicuous nucleoli [Figure 3a and b], the centrocytic-centroblastic lymphoma (NHL-CCCB) show a mixed cell population centrocytes and large centroblasts (large cleaved cells/large noncleaved cells), which are positive for CD20 and BCl2 [Figure 3c–f]. The FNA smears in centroblastic lymphoma on the other hand contain mostly CD20 and BCl2 positive centroblasts with prominent nucleoli, either central or at nuclear margin [Figure 4a-d].

Figure 3.

(a, b) NHL-follicular: centrocytic. A 37-year-old man had 1.5 × 2 cm right cervical lymphadenopathy and hepato-splenomegaly. FNA cytodiagnosis was NHL: FCC-centrocytic, histopathological diagnosis was NHL: follicular (Grade 1/3). (a) Small monomorphic lymphoid cells, slightly larger than mature lymphocytes, have mostly cleaved nuclei (MGG × 1000). (b) Most of the lymphoids cells were CD20+ (×1000). (c-f) FNA smears from a huge right neck swelling of 5 months duration in a 50-year-old man. FNA cytodiagnosis: NHL: Centrocyticcentroblastic (CC-CB), immunocytochemical results were as follows: CD20+, BCl2+. Histopathological diagnosis: NHL: B-cell. (c) Smears show large cleaved- and noncleaved cells (centroblasts) (MGG × 1000). (d) The neoplastic cells had prominent nucleoli (Papanicolaou × 1000). (e) The tumor cells and lymphoglandular bodies were positive for CD20 (×1000). (f) The tumor cells were positive for BCl2 (×1000)

Figure 4.

Centroblastic lymphoma: A 37-year-old man presented with 2 × 2 cm submental lymph node and 1 × 0.5 cm pre-auricular lymph node. Clinical diagnosis: lymphoma versus nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cytodx: NHL: centroblastic lymphoma/large B-cell lymphoma, ICC: CD20+, BCl2+, histopathological diagnosis: NHL: follicular Gr II. (a) Large lymphoma cells with cleaved- or noncleaved nuclei (MGG × 1000). (b) Lymphoma cells with prominent central or peripheral nucleoli (Pap × 1000). (c) Lymphoma cells with cytoplasmic positivity for CD20 (×400). (d) Lymphoma cells with cytoplasmic positivity for BCl2 (×1000). (e-h) Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL): A 60-year-old man presented with 3 × 2 cm right axillary lymph node of >2 months duration. FNA cytodiagnosis: TCRBCL, ICC: CD20+ (tumor cells), CD3+ (lymphocytes), CD30–, and EMA–. Histopathological diagnosis: DLBCL. (e) Lymphoma cells mixed with numerous mature lymphocytes (Pap × 400). (f) Large lymphoma cells and lymphoglandular bodies (MGG × 1000). (g) Lymphoma cells positive for CD20 (×1000). (h) Mature lymphocytes positive for CD3 (×1000)

THE MANTLE CELL LYMPHOMA

On cytologic preparations, MCLs comprise small- to medium-sized cells with delicate nuclear indentations, the chromatin generally being less clumped or coarse compared to small lymphocytic lymphoma. The immunophenotype is CD5+, CD10‒, BCl2+, BCl6‒, MUM1‒, CD43+, CD23±, and cyclin D1+.[11]

MARGINAL ZONE B-CELL LYMPHOMA

These cases are known as monocytoid B-cell lymphoma of the mucosal associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma). The smears show monomorphic population of small- to medium-sized lymphoid cells with plasmacytoid features and round or slightly irregular nuclei. Kaba et al.[18] described the FNA cytologic features of histologically and immunohistochemically proved MALT lymphomas as smears containing numerous plasma cells, lymphocytes with plasma cell differentiation and scattered centrocyte-like cells. The immunophenotype of MALT lymphoma is sIg+, CD5‒, CD10‒, CD19+, CD20+, CD22+, CD23‒, CD43+, BCl2+, BCl6‒, and cyclin D1‒.[8,11]

LARGE B-CELL LYMPHOMA

Large B-cell lymphomas are a heterogeneous group comprising centroblatic, immunoblastic, and anaplastic variants.[8] The large noncleaved cells (centroblasts) and immunoblasts are at least twice to thrice the size of small-cleaved cells; the cytoplasm is abundant, plasmacytoid, or clear to pale, and nuclei have round outlines, vesicular chromatin, and single to multiple prominent nucleoli, which are situated at the nuclear margin in centroblasts and central in immunoblasts.[9,13] Cozzolino et al.[19] described the cytologic features of these cases comprising a predominant large and isolated cell population with irregular nuclear membrane and coarse, granular chromatin but with a pale appearance, and one or two eccentric nucleoli; the cytoplasm was often ill-preserved or occasionally absent imparting the appearance of naked large nuclei. When a large number of mature lymphocytes are present in the background, especially of T-cell origin, TCRBCL is a differential diagnostic possibility in cytologic preparations [Figure 4e–h]. In histology most of these cases have a diffuse architectural pattern, hence, the name DLBCL. The immunohistochemical features include positive reaction for pan B-cell markers (CD19+, CD20+, CD22+, and CD79a+), CD10+ (30–60% cells), BCl6+ (60–90% cells), MUM1+ (35–65% cells), Ki67+ (>90% cells), and p53+ (20–60% cells).[8] Cozzolino et al.[19] divided the DLBCL cases into two groups based on gene expression profiling: germinal center B (GCB) and non-GCB and successfully studied immunocytochemical (ICC) profiles using CD10, BCl6, and MUM1 in 33 cases; ICC combinations were CD10–/BCl6–/MUM1+ (20 cases), and CD10+/BCl6+/MUM1– (8 cases) were the two most common among six different patterns, representing mostly non-GCB and GCB cases, respectively.

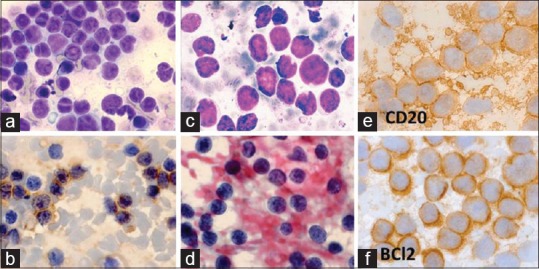

T-CELL HISTIOCYTE-RICH LARGE B-CELL LYMPHOMA

Also known as TCRBCL, this entity represents a rare variant of DLBCL. FNA smears of THRLBCL/TCRBCL cases show a predominant population of small lymphoid cells and variable number of large atypical cells, Hodgkin- and Reed-Sternberg-like cells and scattered or small aggregates of benign histiocytes; immunocytochemical stainings for B-cell marker CD20 and T-cell marker CD3 reveal positive reactions in the large atypical cells and small lymphoid cells, respectively [Figure 5]. Besides pan B-cell markers, TCRBCL is BCl6+, BCl2+ (variable), EMA+ (variable), CD15–, CD30–, CD138–; the background mature cells are CD68+ histiocytes, and CD3+, and CD5+ T-cells.[8] While describing the limitations of FNA cytology in the diagnosis of TCRBCL, Das et al.[20] pointed out that TCRBCL may mostly be confused with HL (CD30+, CD15+, CD45–, B–, T–, EMA–) and ALCL (CD45+, CD30+, CD15–, T+, B–, EMA+, ALK1±); therefore, adequate immunocytochemical studies should be performed before diagnosing this rare neoplasm. According to Cheng and O’Connor,[21] various lymphoma types in which T-cell rich infiltrate is observed among large neoplastic B-cells are classical and nodular sclerosis type HL, TCRBCL, and angio-immunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. We also observed that in some DLBCL, there is variable amount of T-cell infiltration giving rise to confusion with TCRBCL.

Figure 5.

TCRBCL: A 61-year-old man presented with fever, 2 × 3 cm right upper cervical lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly. FNA cytodiagnosis was TCRBCL. ICC: tumor cells were CD20+, CD3–, CD30–, and CD15–, and mature lymphocytes were CD3+. Histopathological diagnosis was THRLBCL. (a) A mixture of large atypical lymphoid cells and mature lymphocytes (MGG × 400). (b) Atypical lymphoid cells have abundant bluish cytoplasm (MGG × 1000). (c) The background also shows many benign histiocytes (Papanicolaou × 400). (d) There were scattered binucleated RS-like cells with prominent nucleoli (Pap × 1000). (e) Large atypical lymphoid cells were positive for CD20 (×400). (f) The background mature lymphocytes were positive for CD3

BURKITT LYMPHOMA

These cases have frequent extranodal disease. Unlike the African counterpart with frequent jaw tumor, abdominal mass is a common presentation in Indian cases.[22] The FNA smears from BL cases contain neoplastic lymphoid cells (10–12 μm in average size) with small noncleaved nuclei and scanty to moderate amount of deep basophilic cytoplasm having fine vacuoles due to neutral lipids and the neoplastic cells are interspersed with tingible body macrophages [Figure 6a and b]; mitotic activity is invariably brisk.[22,23] In our experience, BL is usually under diagnosed in histologic samples.[22,24] The immunohistochemical profile of BL is as follows: mIgM (with light chain restriction), CD1a+, CD20+, CD22+, CD10+, CD38+, CD43+, CD77+, BCl2– (positive in 20% only), BCl6+, Tdt–, and Ki67+ (100% cells).[8] In FNA smears and imprint cytology, the neoplastic cells of BL are invariably of B-cell phenotype with kappa or lambda chain restriction.[25] Demonstration of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) in BL is infrequent in nonendemic areas; in the case of BL mentioned above, Epstein–Barr virus nuclear antigen (EBNA) could be demonstrated along with CD20 and CD10 positivity and negative reaction for BCl2 in the cell block preparation of fine needle aspirates [Figure 6c–f].

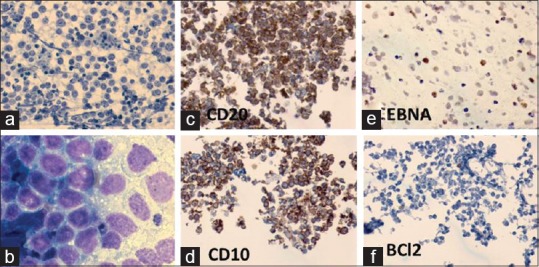

Figure 6.

Burkitt lymphoma: A 78-year-old man had 2 × 2 cm right submandibular lymph node. FNA cytodiagnosis: NHL: BL, ICC: CD20+, CD10+, EBNA+, BCl2–. Histopathological diagnosis: NHL: B-cell type (BL on review). IHC: CD20+, CD79a+, CD10+, CD3–, BCl2–, and EBV-LMP–. (a) FNA smear shows lymphoma cells and tingible body macrophages (MGG × 400). (b) Lymphoma cells had fine cytoplasmic lipid vacuoles (MGG × 1000). (c-f) : In cell block preparations, the neoplastic lymphoid cells were positive for (c) CD20, (d) CD10, and (e) EBNA, and negative for (f) BCL2 (×400)

LYMPHOBLASTIC LYMPHOMA

FNA smears are characterized by intermediate-sized lymphoma cells (9.5–18.5 μm) with irregular nuclear contours, fine nuclear chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and scant cytoplasm along with brisk mitotic activity.[26] These cases have frequent mediastinal mass and associated pleural effusion.[27,28] Because of presence of high content of cells with nuclear convolutions (>50% in 61% cases), these cases were termed malignant lymphoma of convoluted lymphocytes in late-1970s and early-1980s, and their T-cell nature was confirmed by cytochemical staining (focal acid phosphatize and alpha-naphthyl acetate esterase positivity) and E-rosette tests.[27] In the following years, the T-cell nature of these neoplasms were established by detection T-cell immunophenotype (Tdt+, CD3+, CD5+, etc.) and T-cell receptor gene rearrangement studies; Jacobs et al.[26] observed T-cell phenotype in 14 cases and B-cell phenotype in one case only. Frequent hand-mirror cell configuration has been observed by us in the neoplastic cells, which were CD3+, CD20‒, and Tdt+ [Figure 7].

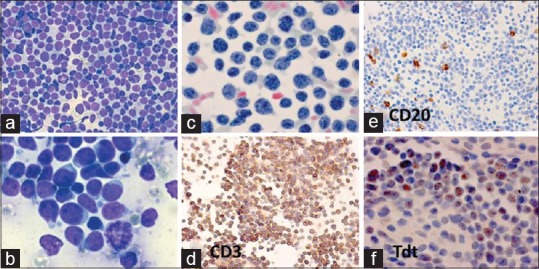

Figure 7.

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma: lymphoblastic (LB). A 5-year-old boy had 3 × 3 cm bilateral cervical and axillary lymphadenopathy. FNAC and histopathological diagnosis: NHL: LB. ICC: CD3+, CD20–, and Tdt+. FNA smears from axillary lymph nodes showed: (a) Uniform population of lymphoblasts with increased mitotic activity (MGG × 400). (b) The lymphoblasts displayed a hand-mirror cell configuration (MGG × 1000). (c) The nuclear chromatin was finely stippled in lymphoblasts (Pap × 1000). (d-f) The neoplastic cells in cell block preparation were (d) positive for CD3 (×400), (e) negative for CD20 (400), and (f) positive for Tdt (1000)

ANAPLASTIC LARGE CELL LYMPHOMA

ALCL, initially described as Ki-1 lymphoma in 1985, was characterized by pleomorphic appearing cells with horseshoe-shaped nucleus, which were immune-reactive for CD30 and EMA.[29] In 1994, the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) t (2;5) translocation took the place as the molecular morphologic counterpart to the hallmark cells.[30] The cytomorphologic features of ALCL include the following: 1) hallmark cells (because they are present in all variants) with eccentric, horseshoe- or kidney-shaped nuclei, which are typically large (but presence of smaller cells with similar morphology greatly aid in accurate diagnosis), 2) doughnut cells: cells with intranuclear inclusion, which represents invagination of cytoplasm into the nucleus.[30,31,32] ALCL is a T/null cell lymphoma with positive immunocytochemical staining for ALK-1 protein in 33% to 57% cases in cytologic specimen.[30,32] ALCL can be distinguished from morphologically similar lesions by immunophenotype CD30+, CD45+, CD15‒, EMA+, BNH9+, keratin‒, lysozyme‒; a recurrent cytogenetic translocation, t (2;5)(p23;q35).[33] Five morphologic patterns of ALCL can be recognized: the common pattern (60%), the lymphohistiocytic pattern (10%), the small cell pattern (5–18%), the Hodgkin-like pattern (3%), and the composite pattern (15%).[8] In addition, there are rare variants including one recently reported by Das et al.[34] an ALCL of the chest wall with peculiar cytoplasmic hyaline globules [Figure 8] and marked variability in nuclear morphology including a teddy bear-shaped nucleus.

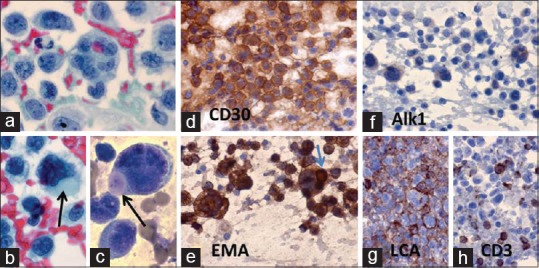

Figure 8.

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL): A 52-year-old man had an 8 × 10 cm chest wall mass on right side. FNA cytodiagnosis: ALCL. ICC findings: LCA+, CD30+, CD15–, CD20–, CD3–, EMA+, Akl1+, CK–, and HMB45–. Histopathological diagnosis: ALCL. IHC: CD45+, CD30+, EMA+, CD2+, CD3+, CD4+, CD5+, CD7+, CD25+, CD43+, Alk1+, and Ki67+ (90% cells). (a) Very large and pleomorphic lymphoma cells (Pap × 1000). (b, c). The lymphoma cells had intracytoplasmic hyaline globules (arrows) (b: Pap × 1000, and c: MGG × 1000). (d) The lymphoma cells were positive for CD30 (×1000). (e) The lymphoma cells including hyaline globule (arrow) are positive for EMA (×1000). (f) The lymphoma cells showed weak positive reaction for Alk1 (×1000). (g) Positive reaction of lymphoma cells to LCA in cell block preparation (×1000). (h) Positive reaction of lymphoma cells to CD3 (×1000)

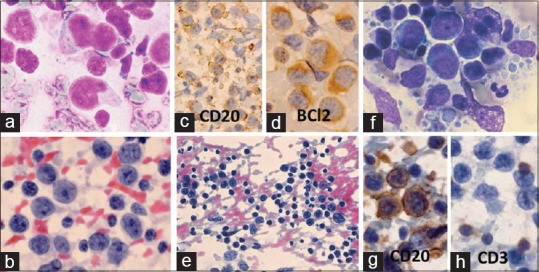

HODGKIN LYMPHOMA

Cytodiagnosis classical HL in FNA smears depends upon demonstration of Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg (HRS) cells or their variants in an appropriate reactive cellular environment consisting of lymphocytes, plasma cell, histiocytes and eosinophils, and its subtyping is based on the relative proportion neoplastic HRS cells to reactive cellular components.[6] The current WHO classification of Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL) generally distinguishes the relatively rare variant of nodular lymphocytic predominant type (approximately 5% of all cases of HL) from a second group, which comprises classical HL and is separated into four subtypes: lymphocyte rich type, nodular sclerosis type, mixed cellular type, and lymphocyte depleted type.[35] The immunophenotype and genetic features are useful in the classification of HL and in distinguishing HL from two recently described, aggressive lymphomas that were in the past often diagnosed as HL, that is, anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, T-cell type, and T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma.[36] Das et al.[37] also found that ALCL and TCRBCL were the two NHL subtypes that created confusion with HL in FNA smears; in view of these investigators,[37] proper interpretation of cytologic features, together with immunocytochemical parameters can be of help in reducing the margin of error in cytodiagnosis of HL. Zhang et al.[38] described the FNA cytologic features of HL based on recent WHO classification. Whereas classical HL can be confirmed with the use of immunophenotype CD15+, CD30+, and CD45‒, the nodular lymphocytic predominant HL has phenotype that includes LCA+, CD20+, CD79a+, CD15‒, and CD30‒ [Figure 9]. However, it will be necessary to extend this panel depending upon the differential diagnostic entities, especially when HL is associated with one or more other pathological lesions; these cases also highlight the limitations of cytodiagnosis when ICC panel is incomplete.[39,40]

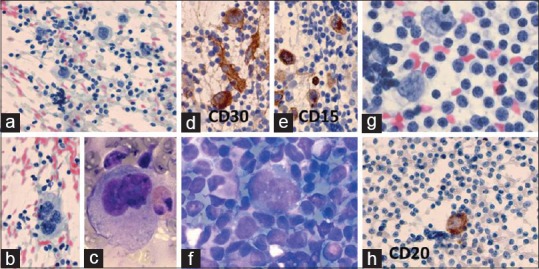

Figure 9.

(a-e) Classical HL: A 32-year-old man with 2 × 2 cm left cervical lymphadenopathy. FNA cytodiagnosis: CHL-MC, ICC results: CD30+, CD15+, LCA–, CD20–, and EMA–. Histopathological diagnosis: CHL-NS. (a) Many large mononucleated Hodgkin cells among mature lymphocytes (Pap × 400). (b) A large tetranucleated Reed-Sternberg cell among lymphocytes (Pap × 400). (c) A large binucleated Reed-Sternberg cell and an eosinophil (MGG × 1000). (d) Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg (HRS). HRS cells are positive for CD30 (×1000). (e) HRS cells are positive for CD15 (×1000). (f-h) Nodular lymphocytic predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL): A 28-year-old man 2 × 2 cm left cervical lymph node. FNA and histopathological diagnosis: NLPHL. IHC of RS cells: LCA+, CD20+, CD79a+, EMA+, CD3–, CD57–, CD68–, Ki67+, HLA-DR+, CD15–, CD30–, CD21–, CD23–, and EBV–. (f) “Popcorn” type of RS cell with lobulated nucleus surrounded by lymphocytes (MGG × 1000). (g) Two “popcorn” types of RS cells partly surrounded by lymphocytes (Pap × 1000). (h) One RS cell with positive reaction for CD20 (×400)

One of the limitations of cytology in the field of lymphoreticular malignancy is its inability to diagnose the follicular pattern, which is a strict histopathological criterion. The small cell NHLs considered in the differential diagnosis of small lymphocytic lymphoma and FL, especially centrocytic type, are MCL and marginal zone/MALT lymphoma.[9] According to Young and Al-Salim,[9] the four subtypes of small cell NHL can be differentiated by a minimum panel of ICC reactions which is as follows: small lymphocytic NHL: CD10‒, CD5+, and CD23+; MCL: CD10‒, CD5+, and CD23‒; FL: CD10+, CD5‒, and CD23±; and MALT lymphoma: CD10‒, CD5‒, and CD23‒. Based on cytomorphology, NHL of follicular center cell origin can be diagnosed when the lymphoma cell population consists of centrocytes or a mixture of centrocytes and centroblasts. A differential diagnosis of DLBCL comes into consideration when the population of lymphoma cell is almost exclusively centroblasts.

The greatest advantage of immunophenotyping of lymphoma in smears, especially cytospin preparations is that the cell morphology can be visually associated with immunophenotype; cell size, configuration, staining pattern, and intensity of staining; the background can be assessed simultaneously.[10] According to Sneige et al.,[41] FNA used in association with ICC is a reliable tool for establishing the diagnosis and classification of majority of cases of lymphomas; 79% of the histologically confirmed lymphomas could be diagnosed and 7% were interpreted as suspicious of lymphoma by these investigators. Mihaescu et al.[42] found 20 cases of lymphomas and 26 suspicious lymphoma cases in a cytomorphological study of 95 effusions; these authors could detect eight additional cases of lymphomas by immunocytochemical studies and were also able to achieve lineage classification in 15 of 20 cases. According to Das et al.,[43] cytomorphological features, along with contribution from ICC studies on fresh as well as archival smears of lymphomatous effusions, serve as useful tool in classifying NHL under the WHO system; however, the presence of appreciable number of cells with convoluted/lobulated nuclei may create difficulty in separating centroblastic lymphoma from lymphoblastic lymphoma, requiring the help of immunocytochemical study. According to Cozzolino et al.,[19] the CD10-BCl6-MUM1 ICC algorithm is reliable in FNA specimen, and equally effective on conventional smear (CS) and cell block preparation (CB); it could subclassify DLBCL cases as germinal center B (GCB) type and non-GCB, which has prognostic implications, GCB group being associated with overall better survival. Higgins et al.[11] also observed that approximately 30–45% of DLBCL are germinal center phenotype (CD10+ or CD10‒, BCl6+, and MUM1‒) and 55–70% are non-germinal center phenotype (CD10‒, BCl6±, and MUM1+) with better survival in germinal center type. A review by Rao[44] shows that besides having a role in subtyping of lymphomas based on morphology and immunohistochemistry (IHC), the latter parameter plays role in prognostication and targeted therapy of lymphoma cases, for example, (1) primary nodal DLBCL-germinal center type being associated with longer survival, (2) BCL2 positivity with MYC translocation in FL is associated with aggressive course, and (3) ALK positive ALCL has better prognosis than ALK negative cases (5-year survival 80% vs 48%).

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bonner H. The blood and the lymphoid organs. In: Rubin R, Farber JL, editors. Pathology. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Co; 1988. pp. 1014–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC, editors. Robbins & Cotran pathologic Basis of Disease. South Asian Edition. RELX India Private Limited, New Delhi. 2015:588–611. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koss LG, Woyke S, Olszewski W, editors, editors. New York: Igaku-Shoin; 1984. Aspiration biopsy: Cytologic interpretation and histologic basis; pp. 115–32. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Das DK, Gupta SK, Datta BN, Sharma SC. FNA cytodoagnosis of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and its sub-typing under working formulation of 175 cases. Diagn Cytopathol. 1991;7:487–98. doi: 10.1002/dc.2840070510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lopes Cardozo P. S’Hertogen Bosch: Targa BV; 1975. Atlas of clinical cytology; pp. 110–5. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Das DK, Gupta SK, Datta BN, Sharma SC. Fine needle aspiration cytodiagnosis of Hodgkin's disease and its subtypes. I. Scope and limitations. Acta Cytol. 1990;34:329–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Das DK. Value and limitations of fine-needle aspiration cytology in diagnosis and classification of lymphomas: A review. Diagn Cytopathol. 1999;21:240–9. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0339(199910)21:4<240::aid-dc3>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, et al., editors. WHO Classification of Tumors of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissue. International agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon. (4th ed) 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Young NA, Al-Saleem T. Diagnosis of lymphoma by fine-needle aspiration cytology using the Revised European–American Classification of Lymphoid Neoplasms. Cancer (Cancer Cytopathol) 1999;87:325–45. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19991225)87:6<325::aid-cncr3>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robins DB, Katz RL, Swan F, Jr, Atkinson EN, Ordonez NG, Huh YO. Immunophenotyping of lymphoma by fine-needle aspiration. A comparative study of cytospin preparations and flow cytometry. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;101:569–76. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/101.5.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins RA, Blankenship JF, Kinney MC. Application of immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis of non-Hodgkin and Hodgkin lymphoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:441–61. doi: 10.5858/2008-132-441-AOIITD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Z, Zhao L, Guo H, Pan Q, Sun Y. Diagnostic significance of immunocytochemistry on fine needle aspiration biopsies processed by thin-layer cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2012;40:1071–6. doi: 10.1002/dc.21736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Das DK. Lymph nodes. In: Bibbo M, editor. Comprehensive Cytopathology. 2nd ed. WB Saunders Co: Philadelphia; 1997. pp. 703–29. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bartlett NL, Longo DL. T-small lymphocyte disorders. Semin Hematol. 1999;36:164–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoyer JD, Ross CW, Li C-Y, Witzig TE, Gascoyne RD, Dewald GW, et al. True T-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: A morphologic and immunophenotypic study of 25 cases. Blood. 1995;86:1163–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Das DK, Pathan SK, Joneja M, Al-Musawi FA, John B, Mirza KR. T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia (T-PLL) with overlapping cytomorphological features with T-CLL and T-ALL: A case initially diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration cytology and immunocytochemistry. Diagn Cytopathol. 2013;41:360–5. doi: 10.1002/dc.21781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rassidakis GZ, Tani E, Svedmyr E, Porwit A, Skoog L. Diagnosis and sub-classification of follicle center and mantle cell lymphoma on fine-needle aspirates. A cytologic and immunocytochemical approach based on the Revised European-American Lymphoma (REAL) Classification. Cancer (Cancer Cytopathol) 1999;87:216–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaba S, Hirokawa M, Kuma S, Maekawa M, Yanase Y, Kojima M, et al. Cytologic findings of primary thyroid MALT lymphoma with extreme plasma cell differentiation: FNA cytology of two cases. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37:815–9. doi: 10.1002/dc.21106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cozzolino I, Varone V, Picardi M, Baldi C, Memoli D, Ciancia G, et al. CD10, BCl6, and MUM 1 expression in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in FNA samples. Cancer (Cancer Cytopathol) 2016;124:135–43. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Das DK, Pathan SK, Mothaffer FJ, John B, Mallik MK, Sheikh ZA, et al. T-cell-rich B-cell lymphoma (TCRBCL): Limitations in fine needle aspiration cytodiagnosis. Diagn Cytopathol. 2012;40:956–63. doi: 10.1002/dc.21683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng CL, O’Connor S. T cell-rich lymphoid infiltrates with large B cells”: A review of key entities and diagnostic approach. J Clin Pathol. 2017;70:187–201. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2016-204065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Das DK, Gupta SK, Pathak IQ, Sharma SC, Datta BN. Burkitt-type lymphoma. Diagnosis by fine needle aspiration cytology. Acta Cytol. 1987;31:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wright DH. Microscopic features, histochemistry, histogenesis and diagnosis. In: DP Burkitt, DH Wright., editors. Burkits Lymphoma. ES Livingstone: Edinburgh; 1970. pp. 82–102. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Das DK, Sheikh ZA, Jassar AK, Jarallah MA. Burkitt-type lymphoma of the breast: Diagnosis by fine-needle aspiration cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2002;27:60–2. doi: 10.1002/dc.99999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stastny JF, Almeida MM, Wakely PE, Jr, Kornstein MJ, Frable WJ. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy and imprint cytology of small non-cleaved cell (Burkitt’s) lymphoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 1995;12:201–7. doi: 10.1002/dc.2840120303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobs JC, Katz RL, Shabb N, El-Naggar A, Ordonez NG, Pugh W. Fine needle aspiration of lymphoblastic lymphoma. A multiparameter diagnostic approach. Acta Cytol. 1992;36:887–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Das DK, Gupta SK, Datta U, Sharma SC, Datta BN. Malignant lymphoma of convoluted lymphocytes. Diagnosis by fine needle aspiration cytology and cytochemistry. Diagn Cytopathol. 1986;2:307–11. doi: 10.1002/dc.2840020408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Das DK, Gupta SK, Ayyagari S, Bambery PK, Datta BN, Datta U. Pleural effusion in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. A cytomorphologic, cytochemical and immunologic study. Acta Cytol. 1987;31:119–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stein H, Mason DY, Gerdes J, O-Conor N, Wainscoat J, Pallesen G, et al. The expression of the Hodgkin's disease associated antigen Ki-1 in reactive and neoplastic lymphoid tissue: Evidence that Reed-Sternberg cells and histiocytic malignancies are derived from activated lymphoid cells. Blood. 1985;66:848–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rapkiewicz A, Wen H, Sen F, Das K. Cytomorphologic examination of anaplastic large cell lymphoma by fine-needle aspiration cytology. Cancer (Cancer Cytopathol) 2007;111:499–507. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ng W-K, Ip P, Choy C, Collins RJ. Cytologic and immunocytochemical findings in anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Analysis of ten fine-needle aspiration specimens over a 9-year period. Cancer (Cancer Cytopathol) 2003;99:33–43. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Das P, Iyer VK, Mathur SR, Ray R. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma: A critical evaluation of cytomorphological features in seven cases. Cytopathology. 2010;21:251–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2009.00675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kadin ME. Primary Ki-1 positive anaplastic large-cell lymphoma: A distinct clinicopathologic entity. Ann Oncol. 1994;5(Suppl):25–30. doi: 10.1093/annonc/5.suppl_1.s25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Das DK, Pathan SK, Al-Qaddomi SA, Al-Ghawas M, El-Sonbaty MR, Ali AE. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma of the chest wall with cytoplasmic globules and variability in nuclear morphology including a teddy bear-shaped nucleus. Diagn Cytopathol. 2015;43:559–62. doi: 10.1002/dc.23260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hansmann ML, Willenbrock K. WHO classification of Hodgkin's lymphoma and its molecular pathological relevance. Pathologie. 2002;23:207–18. doi: 10.1007/s00292-002-0529-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harris NL. Hodgkin's disease: Classification and differential diagnosis. Mod Pathol. 1999;12:159–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Das DK, Francis IM, Sharma PN, Sathar SA, John B, George SS, et al. Hodgkin's lymphoma: Diagnostic difficulties in fine-needle aspiration cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37:564–73. doi: 10.1002/dc.21064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang J-R, Raza AS, Greaves TS, Cobb CJ. Fine-needle aspiration diagnosis of Hodgkin lymphoma using current WHO classification-Re-evaluation of cases from 1999-2004 with new proposals. Diagn Cytopathol. 2006;34:397–402. doi: 10.1002/dc.20439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Das DK, Sheikh ZA, Alansary TA, Amir T, Al-Rabiy FN, Junaid TA. A case of Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis associated with Hodgkin's lymphoma: Fine-needle aspiration cytologic and histopathological features. Diagn Cytopathol. 2015;44:128–32. doi: 10.1002/dc.23392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Das DK, Sheikh ZA, Al-Shama’a MH, John B, Alawi AM, Junaid TA. A case of composite classical and nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma with progression to diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: Diagnostic difficulty in fine-needle aspiration cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 2017;45:262–6. doi: 10.1002/dc.23643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sneige N, Dekmezian RH, Katz RL, Fanning TV, Lukeman JL, Ordonez NF, et al. Morphologic and immunocytochemical evaluation of 220 fine needle aspirates of malignant lymphoma and lymphoid hyperplasia. Acta Cytol. 1990;34:311–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mihaescu A, Gebhard S, Chaubert P, Rochat MC, Braunschweig R, Bosman FT. Application of molecular genetics to the diagnosis of lymphocyte rich effusion: Study of 95 cases with concomitant immunophenotyping. Diagn Cytopathol. 2002;27:90–5. doi: 10.1002/dc.10150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Das DK, Al-Juwaiser A, George SS, Francis IM, Sathar SS, Sheikh ZA, et al. Cytomorphological and immunocytochemical study of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in pleural effusion and ascitic fluid. Cytopathology. 2007;18:157–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2007.00448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rao SI. Role of immunohistochemistry in lymphoma. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2010;31:145–7. doi: 10.4103/0971-5851.76201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]