Abstract

Work stress is a major contributor to absenteeism and reduced work productivity. A randomised and controlled study in employee-volunteers (with Perceived Stress Scale [PSS-14]>22) was performed to assess a mindfulness program based on brief integrated mindfulness practices (M-PBI) with the aim of reducing stress in the workplace. The PSS-14 of the employees before and after 8-weeks M-PBI program, as well as after a 20-week follow-up, was assessed (primary endpoint). The employees also carried the following questionnaires (secondary endpoints): Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ), Self-Compassion Scale (SCS), Experiences Questionnaire-Decentering (EQ-D), and Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI-GS). Heart Rate Variability (HRV) was measured during each session in a subgroup of employees (n = 10) of the interventional group randomly selected. A total of 40 employees (77.5% female median [SD] age of 36.6 [5.6] years) took part in this study: 21 and 19 in the intervention and control group, respectively. No differences in baseline characteristics were encountered between the groups. Results show a significant decrease in stress and increase in mindfulness over time in the intervention group (PSS-14 and FFMQ; p < 0.05 both). Additionally, an improvement in decentering (EQ-D), self-compassion (SCS) and burnout (MBI-GS) were also observed compared to the control group (p < 0.05 in all). HRV measurement also showed an improvement. In conclusion, a brief practices, 8-weeks M-BIP program is an effective tool to quickly reduce stress and improve well-being in a workplace.

Keywords: Mindfulness, stress, M-PBI, FFMQ, EQ-D, burnout, workplace, heart rate variability

Introduction

Work stress is a type of stress inherent of industrialised societies [1]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) work stress is defined as the response people may have when presented with work demands and pressures that are not matched to their knowledge and abilities and which challenge their ability to cope [2]. According to a survey on work stress conducted in 2013 by the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work, half of European workers believe that job stress is common in their workplace. In Spain, 49% of workers considered work-related stress as common, and nearly 4 of 10 (44%) believed work stress is not well controlled in their workplace [3]. Psychological stress is recognized as a major contributor to absenteeism, high staff turnover, and reduced productivity at work [4].

In 1979, Jon Kabat-Zinn developed the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program [5], which is a relatively new approach within behavioral medicine and mainstream health care. Mindfulness is defined as moment-to-moment non-judgmental awareness [6]. It is a training for self-regulation of attention, non-judgmental awareness, adoption of an orientation of curiosity, openness and acceptance of one’s experience in the present moment [7]. Mindfulness interventions started to be used in clinical psychology and related fields, and increasing numbers of studies confirm their effectiveness in different clinical and sub-clinical studies. The positive outcomes of mindfulness have led to the introduction of these interventions and programs in non-clinical fields such as the workplace. The health benefits of mindfulness in the workplace were mainly directed towards stress reduction [8,9]. However, benefits such as improvement in social relations, resiliency and task performance [10], as well as, in task commitment, memory [11], emotional regulation and job satisfaction [12] have also been observed when using mindfulness interventions.

Companies as Aetna [9], General Mills [13], and Google [14] have established mindfulness programs in order to enhance employee well-being and effectiveness.

However, most mindfulness trainings require participants to invest substantial amounts of time and discipline such as in the MBSR [5]. Nevertheless, brief/abbreviated mindfulness programs, with reduced number of sessions and/or time of meditation practices, have been recently established and have reported to be effective in terms of mindfulness and distress reduction [15–17].

The measurement of stress during the mindfulness program can be assessed by specific and validated scales/questionnaires as DASS (Depression, Anxiety, and Stress), PSQ (Perceived Stress Questionnaire), or PSS-14 (Perceived Stress Scale) [18–20].

In addition, there are some biomarkers as the Heart Rate Variability (HRV) which measure the activity of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system [21,22] and can be used as measure of stress. Several areas including the amygdala and the pre-frontal cortex that are involved in perceptions of threat and safety have been found to be associated with HRV [23]. An optimal level of HRV within an organism reflects healthy function and an inherent self-regulatory capacity, adaptability, or resilience. Thus, high HRV values are indicative of low stress levels and greater resiliency. By contrast, low HRV levels show greater stress and lower resiliency [24–27]. Some studies described the relationship between HRV and mindfulness, showing that mindfulness was positively associated with HRV [28,29]. A high HRV correlates with a high capacity to calm down in stressful contexts. Related to this, it has been reported that compassion-based practices can directly increase HRV and potentially other biological, physiological, and neurophysiological measures, such as cortisol [30].

The mindfulness program implemented in this study is based on brief integrated mindfulness practices (M-PBI), which includes compassion practices [31]. This program incorporates short practices to facilitate daily compliance. The purpose of this pilot, controlled study was to assess in employee-volunteers the efficacy of an 8-weeks M-BIP training program in reducing stress and increasing mindfulness ability and increasing the HRV. Additionally the changes in self-compassion, decentering, and the burnout syndrome were assessed.

Methods

Subjects

This was an interventional, randomised and controlled study performed in a workplace sample at the private international clinical research organization company, Trial Form Support (TFS). A total of 47 employee volunteers were screened in October 2015 (2 weeks recruitment), 40 of which were included and randomised into an interventional group (21 subjects) and a control group (corresponding to a waiting list group) (19 subjects) (see Figure 1). The recruitment methods included an informative face-to-face meeting including a short introduction about mindfulness to all the employees in TFS Barcelona’s offices, where employees were invited to participate. Those who were interested in participating and who met the selection criteria received the subject information of the study and signed the consent form.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the pilot study.

The inclusion criteria were: active employees from the TFS Barcelona’s office; who had a PSS-14 score >22 (scores range from 0 to 56); consented to meditate 12–16 min per day during the 8 weeks of the mindfulness program; commit to attend weekly sessions of 1.5 h at the workplace; consented to complete the questionnaires and scales in the established assessments; and were available to undergo a follow-up period of 3 months after the 8-week program was finalized (week-20). Participants, who practice or had practiced meditation or yoga, had any heart problem diagnosed (arrhythmias, cardiovascular diseases, myocardial infarction, or a pacemaker) which could interfere with the HRV measurements and who were considered unfit for study to the discretion of the investigators were excluded.

This cut-off was selected based on an exploratory sample of employee volunteers in TFS Barcelona that showed a PSS-14 median value of 22. In order to get highest differences after the mindfulness program, employers with PSS-14 score >22 were selected.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committees (RECs) of the Facultat de Psicologia i Ciències de l’Educació i de l’Esport Blanquerna-URL (CER de la FPCEE Blanquerna-URL).

Procedure

The M-PBI is a mindfulness program with brief integrated practices. It is based on progressive experiential learning that promotes the practice of focusing attention on a particular object (such as the breath or body sensations), in order to increase the ability of the mind to be in the present without reactivity. Moreover, it includes compassion, open awareness practices, and practices to improve the HRV.

The original M-PBI program is an 8-weeks training consisting of 8 sessions (distributed in different modules) of two and half hours each, and a retreat of four hours of mindfulness practices [31]. For this study, the time of weekly sessions was reduced to 1.5 h and the retreat to 3 hours. In each session, different modules were developed including essential aspects of emotional and relational intelligence. The different modules followed an agenda and were focused on specific formal and informal mindfulness techniques. The duration of the formal daily practices was 12–16 min.

Subjects completed self-reported efficacy measures prior to the start of the first session, at week-8 (session 8, end of the program), and week-20 (session 9, follow-up session). In the interventional group, a subgroup of 10 subjects was randomly selected to assess the HRV during the whole session in the 8 sessions of the program, and at week-20 (follow-up session).

Mindfulness compliance

During the 8-week intervention, participants kept a daily recorded diary describing when they had performed their practices and their practice duration. At the beginning of each session, the subjects delivered their diary to the investigator which would document the practices performed during the previous week. Mindfulness compliance with the formal practice was defined as commitment to meditated 12–16 min per day during the 8 weeks of the mindfulness program.

Measures

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14)

The PSS-14 is a self-reported measure which assesses the degree of stress perceived by the subject in his/her life within the past month [18]. The PSS-14 is comprised of 14 items intended to measure how unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overloaded individuals find their life circumstances.

Individuals rate items on a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 0 “Never” to 4 “Very often.” Scores are obtained by reverse scoring the positively stated items (4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, and 13) and then summing the scores across all 14 items. Scores range from 0–56, with higher scores indicating greater perceived stress. This questionnaire was validated to Spanish by Remor E. [32].

Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ)

The FFMQ is a self-reported 39-item scale to measure five factors of mindfulness: observing (attending to or noticing internal and external stimuli, such as sensations, emotions, cognitions, sights, sounds, and smells), describing (noting or mentally labeling these stimuli with words), acting with awareness (attending to one’s current actions, as opposed to behaving automatically or absent-minded), non-judging of inner experience (refraining from evaluation of one’s sensations, cognitions, and emotions) and non-reactivity to inner experience (allowing thoughts and feeling to come and go, without attention getting caught up in them) [33]. This questionnaire was validated to Spanish by Cebolla et al. [34]. Responses to the items are given on a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = never or very rarely true, 5 = very often or always true). Higher scores indicate more mindfulness in each of the five facets (observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judging and non-reactivity).

Self-Compassion Scale (SCS)

The SCS is a self-reported 26-item questionnaire with six defined subscales: self-kindness, self-judgment, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and over-identification [35]. Responses are designed to assess how respondents perceive their actions toward themselves in difficult times and are rated using a Likert-type scale anchored from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always), validated to Spanish by Garcia-Campayo et al. [36]. Subscale scores are computed by calculating the mean of subscale item responses. A total self-compassion score was calculating by reverse score the negative subscale items self-judgment, isolation, and over-identification, and to sum with self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness. Higher scores indicate greater self-compassion.

Experiences Questionnaire-Decentering (EQ-D)

The Experiences Questionnaire (EQ) is an 11-item self-report scale assessing decentering and rumination [37]. Based on the psychometric characteristics of this original scale – which showed poor loadings of other items placed on rumination factor and a robust structure for decentering factor – only the EQ-Decentering (EQ-D) has been used in the present study, validated to Spanish by Soler et al. [38]. It is an 11-item self-report measure of decentering. Items are rated on a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = never to 5 = always). Higher scores indicate greater decentering.

Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey (MBI-GS)

El MBI-GS [39] is a version of the MBI (Maslach Burnout Inventory for family practice physicians) [40] designed to assess the three components of the burnout syndrome: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment. The self-reported questionnaire used in this study was the validated Spanish version by Salanova et al. [41]. It is a 16-item questionnaire and they are answered in terms of the frequency with which the respondent experiences these feelings, on a seven-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0, “never” to 6, “every day”. The scores of each subscale are the sum of the corresponding item scores divided by the number of items. The scores for each subscale are considered separately and are not combined into a single total score, thus, three scores are computed for each respondent. A high degree of burnout is one in which a respondent has high scores on the emotional exhaustion and depersonalization subscales, and a low score on the personal accomplishment subscale.

Heart Rate Variability

HRV was analysed during all the 1.5 h of the 8 sessions and the follow-up session. To record all R-R intervals, a Polar® H7 hear rate sensor was used. All heart rate sensors were connected via Bluetooth to an iPad (Apple) to monitor and save the R-R intervals of entire sessions through the FitLab® Team App (Health&SportLab, SL). All R-R records were corrected previously to calculate the prior and after HRV parameters (three minutes prior and 3 min after) two breathing coherent measures, one at the beginning of the session and the other one at the end of the session (Pre 1 and Pre 2 prior breathing coherent measures and Post 1 and Post 2 after breathing coherent measures). Prior to each of these two HRV measurements, the natural breathing measurement was recorded (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of the HRV measures.

Notes: Heart Rate Variability (HRV) was measured continuously during the 1.5 h session, and HRV was reported in two points, 3 min prior and 3 min after (pre and post) the two breathing coherent measurements.

Abbreviations: NB; Natural breathing measures, BC; Breathing coherent measures.

Two HRV parameters from time domain were obtained: SDNN (standard deviation of the normal-to-normal intervals) and RMSSD (square root of the mean squared differences of successive normal-to-normal intervals) following the standards of The Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and The North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology [42].

Breathing coherence is included as a technique in the M-PBI program [31] and was obtained using a breathing pattern of 5.5 bpm with an I:E ratio of 5:5 achieved, which was described to allow greater HRV than other breathing patterns [43].

Statistical methods

Description of the qualitative variables was performed using absolute frequencies and percentages and description of quantitative variables was performed using the mean, standard deviation, median, and interquartile range (Q1 and Q3).

Comparisons were analysed using the Wilcoxon’s test for paired comparisons and the Mann–Whitney U-test. Cohen’s d was calculated to estimate the effect size. Small, medium, and large effect size were defined as Cohen’s d values of 0.3, 0.5, and 0.8, respectively.

The generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) analysis of the covariance was conducted for the primary outcome (PSS-14).

In the HRV subgroup, the four different measures obtained during each the session (pre 1, post 1, pre 2, post 2) were described separately.

The analyses were conducted in the Intention To Treat (ITT) population defined as all participants who were randomised.

Mindfulness compliance was defined as those subjects who had mindfulness meditation practice at home ≥80% of the theoretical compliance during the first 8 weeks. Theoretical compliance was calculated according to the time of mindfulness practice defined as: minutes per day expected of mindfulness meditation practices (12 min) multiplied by the total days of the program (8 weeks per 7 days a week). Comparison between subjects with and without mindfulness compliance in the PSS-4 and FFQM was performed.

The missing data values were not replaced.

Data analysis and randomisation were performed using the SAS® statistical package for Windows (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, U.S.). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Demographic characteristics

A total of 40 participants were included in the study, 21 in the interventional group and 19 in the control group. Participants in both groups had a mean (SD) age of 36.6 (5.6) years, 77.5% were female, 92.5% worked full time, with a mean of 5.4 (4.2) years working at the company. Both groups were well balanced according to the sociodemographic characteristics at baseline (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics at baseline.

| Intervention group (n = 21) | Control group (n = 19) | Total (n = 40) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 38.2 (5.0) | 34.8 (5.9) | 36.6 (5.6) | 0.0614 |

| Female, n (%) | 16 (76.2) | 15 (79.0) | 31 (77.5) | 1.0000 |

| Marital status, n (%) | 0.1576 | |||

| Never married | 6 (28.6) | 8 (42.1) | 14 (35.0) | |

| Married or cohabiting | 15 (71.4) | 9 (47.4) | 24 (60.0) | |

| Divorced or separated | 0 (0.0) | 2 (10.5) | 2 (5.0) | |

| Number of children, mean (SD) | 1.1 (0.8) | 1.0 (0.9) | 1.1 (0.8) | 0.7547 |

| Psychological or psychiatric treatment*, n (%) | 4 (19.1) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (10.0) | 0.1079 |

| Work status, n (%) | 0.6284 | |||

| Full time | 19 (90.5) | 18 (94.7) | 37 (92.5) | |

| Part time | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.5) | |

| Others | 1 (4.8) | 1 (5.3) | 2 (5.0) | |

| Job, n (%) | 0.8109 | |||

| Biometry | 7 (33.3) | 5 (26.3) | 12 (30.0) | |

| Clinical operations | 6 (28.6) | 9 (47.4) | 15 (37.5) | |

| Medical writing | 4 (19.1) | 3 (15.8) | 7 (17.5) | |

| Financial | 1 (4.8) | 1 (5.3) | 2 (5.0) | |

| Administration | 1 (4.8) | 1 (5.3) | 2 (5.0) | |

| Human resources | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.5) | |

| Information technology | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.5) | |

| Years working in the company, mean (SD) | 6.4 (4.2) | 4.3 (4.1) | 5.4 (4.2) | 0.0683 |

| Do you have person at your charge? (yes), n (%) | 7 (33.3) | 2 (10.5) | 9 (22.5) | 0.0845 |

Three subjects received psychological treatment and one subject was on treatment with citalopram. None of the participants had diagnosed arrhythmias, cardiovascular diseases, myocardial infarction, or a pacemaker. Abbreviations: standard deviation (SD).

Self-reported measures

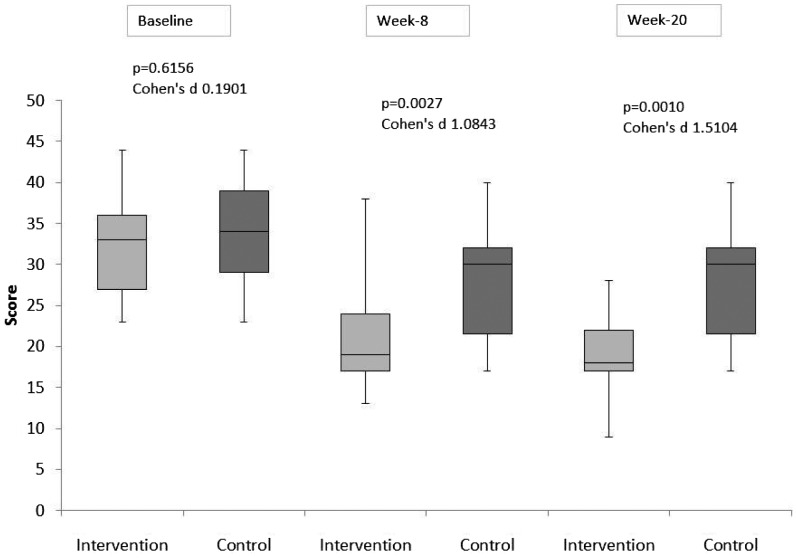

At baseline all self-reported measures showed similar results among the interventional and the control groups (see Figures 3 and 4, and Table 2).

Figure 3.

Evolution of PSS-14 during the study (baseline, week-8 and week-20).

Notes: The box spans data values between the two quartiles (25th and 75th percentiles), with the horizontal line within the box marking the median value. The upper and lower limits represent the maximum and minimum values, respectively.

Figure 4.

Evolution of FFMQ during the study by scales.

Notes: The box spans data values between the two quartiles (25th and 75th percentiles), with the horizontal line within the box marking the median value. The upper and lower limits represent the maximum and minimum values, respectively. A: Observe, B: Describe, C: Non-judge, D: Non-react, and E: Act-aware.

Table 2.

Median SCS, EQ-D and MBI-GS outcomes scores over time for the interventional and control group.

| Measure | Baseline | Week-8 | Follow-up (week-20) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (Q1, Q3) | Intervention | Control | Cohen’s d | Intervention | Control | Cohen’s d | Intervention | Control | Cohen’s d |

| SCS: | |||||||||

| Self-kindness | 2.4 (2.0, 3,0) | 2.8 (2.2, 3.0) | 0.3395 | 3.2 (2.8, 3.6) | 2.4 (2.0, 3.0)* | 1.0016 | 3.2 (3.0, 3.8) | 2.5 (2.1, 3.1)** | 0.8108 |

| Self-judgment reverse code | 3.0 (2.2, 3.2) | 2.8 (2.0, 3.4) | 0.0154 | 3.8 (2.8, 4.2) | 2.6 (2.2, 3.0)* | 1.1421 | 3.6 (3.2, 3.8) | 2.6 (2.4, 3.4)* | 0.6850 |

| Common humanity | 2.8 (2.3, 3.3) | 2.6 (2.0, 2.8) | 0.2923 | 2.8 (2.0, 4.0) | 2.8 (2.3, 3.3) | 0.3674 | 3.5 (3.0, 3.8) | 2.5 (2.3, 3.0)** | 1.4059 |

| Isolation reverse code | 3.0 (2.3, 3.5) | 3.0 (2.5, 3.8) | 0.1813 | 3.8 (3.0, 4.3) | 2.8 (2.3, 3.0)* | 1.1949 | 3.8 (3.0, 4.0) | 2.8 (2.5, 3.1)* | 0.7790 |

| Mindfulness | 2.3 (2.3, 3.3) | 2.8 (2.0, 3.5) | 0.2596 | 3.3 (2.8, 3.8) | 2.5 (2.0, 3.3)* | 0.8549 | 3.3 (3.0, 3.5) | 2.5 (2.3, 3.1)* | 0.7980 |

| Over-identification reverse code | 2.3 (2.0, 2.8) | 2.5 (2.0, 3.0) | 0.3134 | 3.3 (2.8, 3.5) | 2.5 (2.3, 3.0)* | 1.0102 | 3.3 (2.8, 3.3) | 2.4 (2.0, 3.0)* | 0.8029 |

| Total score | 2.7 (2.2, 3.1) | 2.8 (2.2, 3.1) | 0.1601 | 3.3 (3.0, 3.7) | 2.6 (2.2, 2.9)* | 1.1979 | 3.3 (3.2, 3.5) | 2.7 (2.4, 2.8)* | 1.1881 |

| EQ-D | 33.0 (27.0, 35,0) | 33.0 (29.0, 36.0) | 0.6837 | 40.0 (35.0, 41.0) | 33.0 (28.0, 34.0)** | 1.3379 | 39.0 (36.0, 41.0) | 32.0 (28.0, 34.0)* | 1.2016 |

| MBI-GS: | |||||||||

| Emotional exhaustion | 2.8 (2.2, 4.0) | 2.8 (1.8, 3.4) | 0.1230 | 2.0 (1.6, 2.8) | 2.4 (2.0, 3.6) | 0.5127 | 1.6 (1.2, 2.8) | 2.5 (1.5, 4.2) | 0.4666 |

| Depersonalization | 2.4 (1.4, 3.6) | 1.8 (1.2, 2.6) | 0.4183 | 1.6 (1.2, 2.4) | 2.0 (1.2, 2.4) | 0.0366 | 1.8 (1.0, 2.6) | 1.7 (1.0, 3.1) | 0.1917 |

| Personal accomplishment | 4.2 (3.5, 4.7) | 4.5 (3.8, 5.0) | 0.3576 | 4.2 (3.8, 4.8) | 4.2 (3.5, 4.8) | 0.3210 | 4.7 (3.7, 5.0) | 4.5 (3.7, 4.7) | 0.5096 |

Notes: On the EQ-D, higher scores indicate greater decentering (range from 11 to 55). On the MBI-GS, a high degree of burnout is one in which a respondent has high scores on the emotional exhaustion (range from 0 to 5) and depersonalization subscales (range from 0 to 5), and a low score on the personal accomplishment subscale (range from 0 to 6). On the SCS, higher scores indicate greater self-compassion (from 1 to 5).

Abbreviations: EQ-D, The Experiences Questionnaire; Q, quartile; MBI-GS, Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey; SCS, Self-Compassion Scale.

P-value (Wilcoxon’s test) between groups *<0.05, **<0.001.

Perceived Stress Scale

At the end of the program (week-8), significantly median lower scores were observed in the interventional group compared with the control group (19.0 [17.0, 24.0] vs. 28.0 [23.0, 37.0], p = 0.0027), these were maintained at week-20 (18.0 [17.0, 22.0] vs. 30.0 [21.5, 32.0], p = 0.0010) (Figure 3). The results of the GLMM analysis showed significantly lower adjusted mean values at week 8 in the intervention group vs. control group (p = 0.0062).

Significant median differences (week-8 and week-20 vs. baseline) between the two groups were observed (see Table S1).

Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire

At the end of the mindfulness program (week-8), significantly higher values in all subscales in the intervention vs. control groups were observed (intervention vs. control groups: 26.0 [21.0, 28.0] vs. 16.0 [12.0, 23.0] observe, 25.0 [22.0, 31.0] vs. 21.0 [17.0, 23.0] describe, 27.0 [24.0, 30.0] vs. 23.0 [19.0, 25.0] act aware, 31.0 [27.0, 36.0] vs. 25.0 [22.0, 28.0] non-judge, and 21.0 [20.0, 24.0] vs. 17.0 [13.0, 20.0] non-react), and were maintained at week-20 in all subscales (p < 0.05, in all cases) (Figure 4).

Significant median differences (week-8 and week-20 vs. baseline) between the two groups were observed in all five-scales, except observed and described at week-20 vs. baseline (see Table S1).

Self-compassion

At week-8, higher median significant values in the intervention vs. control groups were observed in all subscales (p < 0.05, in all cases), except common humanity. At week-20, all subscales in the interventional groups showed higher significant values compared with control group (p < 0.05, in all cases) (Table 2). The mean (SD) values are shown in Table S1.

Significant median differences (week-8 and week-20 vs. baseline) between the two groups were observed in all scales, except mindfulness at week-8 and week-20 20 vs. baseline (see Table S1).

Experiences Questionnaire-Decentering

At the end of the program (week-8), a significant higher median was observed in the interventional group compared with the control group. This significant higher value was maintained at week-20 (Table 2).

Significant median differences (week-8 and week-20 vs. baseline) were observed between the two groups (Table S1).

Maslach Burnout Inventory-General Survey

Higher values observed in the interventional group compared to the control group, without statistical significance, neither at week-8 nor at week-20 (Table 2). However, the median differences (week-8 vs. baseline) between the two groups were statistically significant in the three subscales (intervention vs. control groups) (emotional exhaustion –1.0 [–1.4, –0.4] vs. 0.0 [–0.6, 0.4], p = 0.0014; depersonalization –0.6 [–1.4, 0.2] vs. 0.2 [–0.2, 0.4], p = 0.0264), and reduced personal accomplishment (0.3 [ 0.0, 0.7] vs. –0.1[–0.7, 0.1], p = 0.0118). Furthermore, at week-20, these differences vs. baseline were maintained (Table S1).

Results according to compliance with the M-BIP program

In the intervention group, 11 subjects (52.4%) showed compliance with the program. The comparison of changes in PSS-14 scores (week-8 vs. baseline) between subjects from the intervention group with or without mindfulness compliance showed no significant differences (median [Q1, Q3] of –13.0 [–19.0, –11.0] vs. –8.0 [–14.4, –3.0], p = 0.1851), even though the change was quantitatively greater in the compliant group. On the other hand, the FFMQ (total score) comparison showed a significantly higher improvement (change at week-8 vs. baseline) in subjects with mindfulness compliance vs. subjects without compliance (31.0 [25.0, 35.0] vs. 11.0 [4.0, 15.0], p = 0.0024).

Comparison of PSS-14 and FFMQ values (change at week-8 vs. baseline) between non-compliant subjects and control group showed higher values in the non-compliant subjects (–8.0 vs. –3.0 PSS-14, p = 0.0617 and 11.0 vs. –1.0 FFMQ, p = 0.0245, respectively).

Heart rate variability

The results of the HRV (SDNN and RMSSD) measurements are shown in Table 3. In the eight weekly sessions, the SDNN and RMSSD values at baseline and prior to the first coherent breathing (pre 1) were lower than after the first coherent breathing (post 1). At the end of the sessions, the values prior to the second coherent breathing (pre 2) were generally higher than those observed at baseline (pre 1), and the values after the second coherent breathing (post 2) showed a further increase compared to pre 2. The SDNN and RMSSD values showed a similar pattern during the eight sessions.

Table 3.

HRV values: SDNN and RMSSD parameters prior and after two coherent breathing measures.

| Median (Q1-Q3) | Pre 1 | Post 1 | Pre 2 | Post 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDNN (msec) | ||||

| Session 1 (n = 9) | 47.0 (42.0–61.0) | 98.5 (81.5–117.5) | 69.0 (56.0–93.0) | 98.5 (78.5–103.0) |

| Session 2 (n = 8) | 40.5 (40.0–104.0) | 83.0 (73.0–93.0) | 96.0 (63.0–110.0) | 91.0 (78.0–99.0) |

| Session 3 (n = 8) | 53.0 (45.0–58.0) | 76.0 (70.0–116.0) | 84.0 (52.0–95.0) | 110.0 (74.0–131.0) |

| Session 4 (n = 7) | 61.0 (48.0–79.0) | 85.0 (66.0–91.0) | 70.0 (61.0–99.0) | 87.0 (73.0–103.0) |

| Session 5 (n = 9) | 55.0 (49.0–56.0) | 71.0 (53.0–84.0) | 74.0 (53.0–84.0) | 83.5 (58.0–112.0) |

| Session 6 (n = 8) | 48.0 (45.0–79.5) | 81.0 (48.0–107.0) | 71.5 (69.0–89.0) | 96.5 (81.0–145.0) |

| Session 7 (n = 9) | 53.5 (45.0–78.0) | 71.0 (51.0–110.0) | 72.0 (51.0–83.0) | 92.0 (71.0–117.0) |

| Session 8 (n = 8) | 56.0 (42.5–65.5) | 91.0 (61.0–106.0) | 68.0 (42.5–65.5) | 83.5 (61.0–130.0) |

| Follow-up (n = 6) | 59.0 (43.0–72.5) | 84.0 (74.0–115.0) | 59.5 (43.0–72.5) | 96.5 (66.0–110.0) |

| RMSSD (msec) | ||||

| Session 1 (n = 9) | 25.0 (20.0–33.0) | 52.0 (42.0–77.0) | 37.0 (31.0–56-0) | 53.5 (43.5–55.5) |

| Session 2 (n = 8) | 28.0 (20.5–52.5) | 42.5 (38.5–48.0) | 49.0 (28.0–57.0) | 54.0 (44.0–66.0) |

| Session 3 (n = 8) | 32.0 (24.5–33.0) | 53.0 (37.0–65.0) | 42.0 (25.0–65.0) | 68.0 (47.0–71.0) |

| Session 4 (n = 7) | 34.0 (30.0–51.0) | 40.0 (34.0–54.0) | 41.5 (29.0–59.0) | 55.0 (40.0–59.0) |

| Session 5 (n = 9) | 39.0 (25.0–45.0) | 41.0 (36.0–55.0) | 48.0 (39.0–52.0) | 57.5 (44.0–84.0) |

| Session 6 (n = 8) | 30.5 (24.0–56.0) | 44.0 (22.0–73.0) | 46.0 (40.0–64.0) | 59.5(55.0–101.0) |

| Session 7 (n = 9) | 28.5 (17.0–90.0) | 45.0 (24.0–81.0) | 41.0 (32.0–62.0) | 60.0 (42.0–74.0) |

| Session 8 (n = 8) | 31.5 (25.5–50.5) | 44.0 (27.0–63.0) | 46.0 (42.0–104) | 49.5 (38.0–87.0) |

| Follow-up (n = 6) | 30.5 (17.0–46.5) | 46.0 (32.0–71.0) | 39.0 (27.0–46.0) | 56.0 (42.0–78.0) |

Abbreviations: Q, quartile; Pre 1 (prior to the first coherent breathing), Post 1 (after the first coherent breathing), Pre 2 (prior to the second coherent breathing), Post 2 (after the second coherent breathing), RMSSD, root of the mean of squared differences of successive normal-to-normal intervals; SDNN, standard deviation of the normal-to-normal intervals.

Discussion

The results of this study support the efficacy of this brief practice mindfulness program in reducing stress in a workplace. Moreover, it has also been effective in increasing mindfulness ability, HRV, self-compassion, and decentering as well as decreasing burnout syndrome. Previous results of this mindfulness program (M-BIP) have demonstrated an improvement in mindfulness ability, decentering and depression, anxiety and stress [44]. This study presents for the first time a pilot, randomized controlled trial using this brief mindfulness practices program. Different abbreviated mindfulness programs have showed good results related to stress and anxiety reduction, improving attention, and self-regulation [15,17,43–47].

In particular, an abbreviated mindfulness intervention study in primary care reported a significant stress reduction after week-8, and it was maintained at month-9 post-intervention (mean baseline score of 19.0 to 14.1 at week-8 and 14.7 at month-9) [16]. Similar results were also reported in a mind–body randomized controlled trial conducted in a workplace, showing a significant improvement on perceived stress (mean score of 24.7 at pre-intervention to 15.9 at post-intervention) [9]. On the other hand, these two studies measured perceived stress by the PSS-10, which cannot allow direct comparisons with our results. However, the results of a work impact of an online mindfulness intervention showed a significant reduction on perceived stress assessed by the PSS-14 (mean score of 24.5 at pre-intervention vs. 18.0 post-intervention, and was maintained [18.8] at 6 month follow-up) [48]. The mean baseline PSS-14 values reported in the last study (24.5) were lower than those observed in our study. This difference could be due to the inclusion criteria of subjects with PSS-14 score >22, which confers a selection bias.

Mindfulness ability measured by the FFMQ showed also a significant reduction in all subscales assessed, the main changes at week-8 compared to baseline were perceived in the subscales observe and non-judge . These main differences in these two subscales were also reported previously in primary care professionals in Spain [49].

Some studies suggested that mindfulness is a process that facilitates decentering, which is defined as the ability to dissenter from one’s thoughts and emotions, and viewing them as passing mental events [50,51]. In our study, significant improvements on decentering after finishing the mindfulness program and at follow-up were observed. Of note, a randomized controlled trial comparing a mindfulness intervention in a nonclinical adult sample, decentering was a significant mediator in the link between mindfulness and psychological well-being of the subjects [52].

Related to self-compassion, it was defined by Kristin Neff [53] as an emotionally positive self-attitude that should protect against the negative consequences of self-judgment, isolation, and rumination. After the 8 weeks of the MPB-I program, an increase in self-compassion was observed, an increase which was maintained at follow-up. On this note, a previous study performed in a cohort of nurses, reported that higher levels of self-compassion were linked with lower levels of burnout [54]. Moreover, a correlation between self-compassion and job satisfaction was also observed, leading to a positive impact on productivity, presence, and competitive performance and resulting in a decline in employee turnover rates and withdrawal behaviors [55].

Finally, the occupational burnout assessment classified the subjects in our study, at baseline, to have a medium-high emotional exhaustion, high depersonalization and medium-low personal accomplishment, according to the normative data of burnout scales in Spanish workers [56]. Nevertheless, after 8-weeks of the mindfulness program, the burnout decreased, this decrease was maintained at follow-up. Comparison of our results with two previous studies in Spanish workers showed that, at baseline, the subjects in our study presented a higher occupational burnout with a higher emotional exhaustion (2.8 vs. 2.1 or 2.3), higher depersonalization (2.4 vs. 1.5 or 1.6) and lower personal accomplishment (4.2 vs. 4.5 or 4.4) [41,56]. It was reported that women feel significantly more emotionally exhausted and less effective at the professional level than men [41]. The fact that our population was mostly women and that one of the study inclusion criteria was subjects must have a PSS-14 score >22, could affect the burnout scores observed at baseline.

Noteworthy, the results of different brief practices mindfulness program have showed good results in reduction of stress, job burnout, depression, and/or anxiety [15,16,57], providing a higher compliance with the mindfulness practice and less rate of dropouts. Related to this, the results of a MBSR program (52-h time) for Health Care Professionals showed a high rate of dropouts (44.4%), being the main cause a lack of time by the participants [58]. On the contrary, the results of a pilot uncontrolled study using an abbreviated version of the MBSR program showed a good compliance with only one subject leaving the study [16]. In our study, among 21 subjects included in the intervention group, only 2 dropouts at 8-week were observed. It is important to address the time limitation that currently has the majority of the population [58]. Although in our study few dropouts were observed, and all subjects who remain in the study attended all the sessions, compliance with the formal practice was observed in 52% of the participants in the intervention group. Compliant subjects showed a higher improvement in perceived stress (PSS-14) and mindfulness scores (FFMQ) at 8-week compared with non-compliant subjects. However, non-compliant subjects did show an improvement in stress and mindfulness when compared to the control group, which shows the importance of the workplace sessions and the mindfulness program on the subjects.

The effects of the mindfulness program were maintained at follow-up (three months after finishing the mindfulness program). These long-term effects of mindfulness intervention have been reported previously to last up to 9 months post-intervention [16]. This long-term effects are due to the neuroplasticity which occurs throughout the mindfulness program, as some studies demonstrated [59]. Related to this, Murakami et al. have also demonstrated a relationship between mindfulness meditation and brain structures, showing a positive association between the describing facet in the FFMQ and grey matter volume in the right anterior insula and right amygdala [60]. The developed right anterior insula volume in individuals with a higher describing score may facilitate more awareness of their own emotional states, and awareness of their own stressful states may enable them to exert cognitive control over their emotions. This neuroplasticity was also observed in perceived stress reductions which correlated positively with decreases in right basolateral amygdala grey matter density [61]. Other studies also supported the effects of mindfulness in different areas of the brain [59–61], demonstrating that neural systems are modifiable networks and changes in the neural structure can occur in adults as a result of training.

Regarding the usefulness of HRV as a biomarker of stress [23], we noticed a higher HRV values after coherent breathing compared to spontaneous breathing rate as has been previously described [43], both at the beginning and at the end of each mindfulness session. Moreover, the HRV increase observed during the first coherent breathing (prior to the session) was mostly maintained at the end of the session, before applying the second coherence breathing, suggesting a positive effect of mindfulness session in HRV. These results also suggest that the combined use of breathing training together with mindfulness practice may have a synergistic effect in stress reduction.

This study has some limitations, such as the modest sample size. Other important limitations include that participants in the study were people who voluntarily participated and presented a high stress level (PSS-14 score >22). This might have led to a selection bias towards subjects with a higher motivation toward mindfulness training. The lack of an active control is another limitation which may also bias the results of the study. Moreover, the sample was not selected to be representative of all employees and the HRV analysis was performed in a small subject sample, thus additional studies are required to further explore and verify the results presented here.

In conclusion, this pilot study suggests that an 8-weeks mindfulness brief practices program is an effective and time-efficient tool to help employees to quickly reduce stress and improve their well-being. Future research with larger samples must examine the impact of such interventions on costs, long-term productivity, health outcomes, and assess the mechanisms of action of these mindfulness interventions.

Funding

The study was funded by TFS Develop.

Disclosure statement

MS, ML, RD are employees of TFS.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed https://doi.org/10.1080/10773525.2017.1386607.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work is dedicated to Mónica Mejía. Thank you very much for your support, your smile and your friendship. It has been a great to walk beside you all these years, an amazing learning experience and a personal growth. We would like to thank Montse Armengol for her valuable assistance in logistics of the sessions, Ana Huerto (Human Resources), and Ricard Quingles, Tània Nadal, Montse Barceló, and Marta Mas (management team members of TFS Spain) for their willingness to accept the projects funding support authorization. Petra Cantó collaborated in the study design and protocol writing as a part of a Master of the Pharmaceutical and Biotechnological Industry at the Universitat Pompeu Fabra

References

- [1].World Health Organization Raising awareness of stress at work in developed countries. 2007. Available from: http://www.who.int/occupational_health/publications/raisingawarenessofstress.pdf

- [2].Word Health Organization. Work organization and Stress Stress at the workplace. 2004. Available from:http://www.who.int/occupational_health/topics/stressatwp/en/.

- [3].European Agency for Safety and Health European opinion poll on occupational safety and health. Eur Agency Saf Health Work. 2013. Available from https://osha.europa.eu/en/surveys-and-statistics-osh/european-opinion-polls-safety-and-health-work/european-opinion-poll-occupational-safety-and-health-2013

- [4].Goetzel RZ, Long SR, Ozminkowski RJ, et al. Health, absence, disability, and presenteeism cost estimates of certain physical and mental health conditions affecting U.S. employers. J Occup Environ Med. 2004;46(4):398–412. 10.1097/01.jom.0000121151.40413.bd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophe living: using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain and illness. New York (NY): Dell Publishing; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kabat-Zinn J. Wherever you go, there you are: mindfulness meditation in everyday life. New York (NY): Hyperion; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chambers R, Gullone E, Allen NB. Mindful emotion regulation: an integrative review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(6):560–572. 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Klatt MD, Buckworth J, Malarkey WB. Effects of low-dose mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR-ld) on working adults. Health Educ Behav Off Publ Soc Public Health Educ. 2009;36(3):601–614. 10.1177/1090198108317627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wolever RQ, Bobinet KJ, McCabe K, et al. Effective and viable mind-body stress reduction in the workplace: a randomized controlled trial. J Occup Health Psychol. 2012;17(2):246–258. 10.1037/a0027278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Glomb TM, Duffy MK, Bono JE, et al. Research in personnel and human resources management. 2011. Available from: https://experts.umn.edu/en/publications/mindfulness-at-work [Google Scholar]

- [11].Levy DM, Wobbrock JO, Kaszniak AW, et al. The effects of mindfulness meditation training on multitasking in a high-stress information environment Proceedings of Graphics Interface 2012 [Internet]. Toronto: Canadian Information Processing Society; 2012. Available from: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2305276.2305285 [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hülsheger UR, Alberts HJEM, Feinholdt A, et al. Benefits of mindfulness at work: the role of mindfulness in emotion regulation, emotional exhaustion, and job satisfaction. J Appl Psychol. 2013;98(2):310–325. 10.1037/a0031313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gelles D. Mindful work: how meditation is changing business from the inside out. 1st ed. Boston: Eamon Dolan/Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kelly C. O.K., Google, Take a deep breath. 2012.

- [15].Bergen-Cico D, Possemato K, Cheon S. Examining the efficacy of a brief mindfulness-based stress reduction (Brief MBSR) program on psychological health. J Am Coll Health J ACH. 2013;61(6):348–360. 10.1080/07448481.2013.813853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Fortney L, Luchterhand C, Zakletskaia L, et al. Abbreviated mindfulness intervention for job satisfaction, quality of life, and compassion in primary care clinicians: a pilot study. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(5):412–420. 10.1370/afm.1511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Glück TM, Maercker A. A randomized controlled pilot study of a brief web-based mindfulness training. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:175. 10.1186/1471-244X-11-175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–396. 10.2307/2136404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Fliege H, Rose M, Arck P, et al. The perceived stress questionnaire (PSQ) reconsidered: validation and reference values from different clinical and healthy adult samples. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(1):78–88. 10.1097/01.psy.0000151491.80178.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33(3):335–343. 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Karim N, Hasan JA, Ali SS. Heart rate variability – a review. J Basic Appl Sci. 2011;7(1):71–77. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Shaffer F, McCraty R, Zerr CL. A healthy heart is not a metronome: an integrative review of the heart’s anatomy and heart rate variability. Front Psychol. 2014;5:1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Thayer JF, Åhs F, Fredrikson M, et al. A meta-analysis of heart rate variability and neuroimaging studies: Implications for heart rate variability as a marker of stress and health. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36(2):747–756. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Segerstrom SC, Nes LS. Heart rate variability reflects self-regulatory strength, effort, and fatigue. Psychol Sci. 2007;18(3):275–281. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01888.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].McCraty R, Childre D. Coherence: bridging personal, social, and global health. Altern Ther Health Med. 2010;16(4):10–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Reynard A, Gevirtz R, Berlow R, et al. Heart rate variability as a marker of self-regulation. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2011;36(3):209–215. 10.1007/s10484-011-9162-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].McCraty R, Zayas MA. Cardiac coherence, self-regulation, autonomic stability, and psychosocial well-being. Front Psychol. 2014;5:1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Azam MA, Katz J, Mohabir V, et al. Individuals with tension and migraine headaches exhibit increased heart rate variability during post-stress mindfulness meditation practice but a decrease during a post-stress control condition – a randomized, controlled experiment. Int J Psychophysiol Off J Int Organ Psychophysiol. 2016;110:66–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Mankus AM, Aldao A, Kerns C, et al. Mindfulness and heart rate variability in individuals with high and low generalized anxiety symptoms. Behav Res Ther. 2013;51(7):386–391. 10.1016/j.brat.2013.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kirby JN, Doty JR, Petrocchi N, et al. The current and future role of heart rate variability for assessing and training compassion. Front Public Health. 2017;5:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Arredondo M, Hurtado P, Sabaté M, et al. Mindfulness training program based on brief integrated practices (M-PBI). Rev Psicoter. 2016;27:133–150. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Remor E. Psychometric properties of a European Spanish version of the perceived stress scale (PSS). Span J Psychol. 2006;9(01):86–93. 10.1017/S1138741600006004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, et al. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment. 2006;13(1):27–45. 10.1177/1073191105283504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Cebolla A, García-Palacios A, Soler J, et al. Psychometric properties of the Spanish validation of the Five Facets of Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ). Eur J Psychiatry. 2012;26(2):118. 10.4321/S0213-61632012000200005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Neff KD. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Identity. 2003;2:223–250. 10.1080/15298860309027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Garcia-Campayo J, Navarro-Gil M, Andrés E, et al. Validation of the Spanish versions of the long (26 items) and short (12 items) forms of the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12:4. 10.1186/1477-7525-12-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Fresco DM, Moore MT, van Dulmen MHM, et al. Initial psychometric properties of the experiences questionnaire: validation of a self-report measure of decentering. Behav Ther. 2007;38(3):234–246. 10.1016/j.beth.2006.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Soler J, Franquesa A, Feliu-Soler A, et al. Assessing decentering: validation, psychometric properties, and clinical usefulness of the experiences questionnaire in a Spanish sample. Behav Ther. 2014;45(6):863–871. 10.1016/j.beth.2014.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP, Maslach C, et al. The Maslach Burnout Inventory: General Survey (MBI-GS) En: Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP, editors. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. 30 edición, Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist Press; 1996. p. 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Rafferty JP, Lemkau JP, Purdy RR, et al. Validity of the Maslach burnout inventory for family practice physicians. J Clin Psychol. 1986;42(3):488–492. 10.1002/(ISSN)1097-4679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Salanova M, Schaufeli WB, Llorens S, et al. Desde el “burnout” al “engagement”: una nueva perspectiva. Rev Psicol Trab Las Organ. 2000;16(2):117–134. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Heart rate variability Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Eur Heart J. 1996;17(3):354–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Lin IM, Tai LY, Fan SY. Breathing at a rate of 5.5 breaths per minute with equal inhalation-to-exhalation ratio increases heart rate variability. Int J Psychophysiol Off J Int Organ Psychophysiol. 2014;91(3):206–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Arredondo M, Sabaté M, Botella L, et al. Estudio Piloto del Programa de Entrenamiento en Mindfulness Basado en Prácticas Breves Integradas (M-PBI). Rev Psicoter. 2016;27(103):151–168. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Tang Y-Y, Ma Y, Wang J, et al. Short-term meditation training improves attention and self-regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(43):17152–17156. 10.1073/pnas.0707678104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Zeidan F, Johnson SK, Diamond BJ, et al. Mindfulness meditation improves cognition: evidence of brief mental training. Conscious Cogn. 2010;19(2):597–605. 10.1016/j.concog.2010.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Chen Y, Yang X, Wang L, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the effects of brief mindfulness meditation on anxiety symptoms and systolic blood pressure in Chinese nursing students. Nurse Educ Today. 2013;33(10):1166–1172. 10.1016/j.nedt.2012.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Aikens KA, Astin J, Pelletier KR, et al. Mindfulness goes to work: impact of an online workplace intervention. J Occup Environ Med. 2014;56(7):721–731. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Martín Asuero A, Rodríguez Blanco T, Pujol-Ribera E, et al. Evaluación de la efectividad de un programa de mindfulness en profesionales de atención primaria. Gac Sanit. 2013;27(6):521–528. 10.1016/j.gaceta.2013.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Hayes SC. Get out of your mind and into your life: the new acceptance and commitment therapy. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Pearson MR, Brown DB, Bravo AJ, et al. Staying in the moment and finding purpose: the associations of trait mindfulness, decentering, and purpose in life with depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and alcohol-related problems. Mindfulness. 2015;6(3):645–653. 10.1007/s12671-014-0300-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Josefsson T, Lindwall M, Broberg AG. The effects of a short-term mindfulness based intervention on self-reported mindfulness, decentering, executive attention, psychological health, and coping style: examining unique mindfulness effects and mediators. Mindfulness. 2014;5(1):18–35. 10.1007/s12671-012-0142-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Neff K. Self-compassion an alternative conceptualization of a health attitude toward oneself. Self Ident. 2003;2:85–101. 10.1080/15298860309032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Durkin M, Beaumont E, Hollins Martin CJ, et al. A pilot study exploring the relationship between self-compassion, self-judgement, self-kindness, compassion, professional quality of life and wellbeing among UK community nurses. Nurse Educ Today. 2016;46:109–114. 10.1016/j.nedt.2016.08.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Abaci R, Arda D. Relationship between self-compassion and job satisfaction in white collar workers. Procedia – Soc Behav Sci. 2013;106:2241–2247. 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.255 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Bresó E, Salanova M, Schaufeli W, et al. NTP 732: Síndrome de estar quemado por el trabajo “Burnout” (III): Instrumento de medición. Minist Trab Asun Soc Guías Buenas Prácticas; Available from: http://www.insht.es/InshtWeb/Contenidos/Documentacion/FichasTecnicas/NTP/Ficheros/701a750/ntp_732.pdf [Google Scholar]

- [57].Mackenzie CS, Poulin PA, Seidman-Carlson R. A brief mindfulness-based stress reduction intervention for nurses and nurse aides. Appl Nurs Res ANR. 2006;19(2):105–109. 10.1016/j.apnr.2005.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Shapiro SL, Astin JA, Bishop SR, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for health care professionals: results from a randomized trial. Int J Stress Manag. 2005;12(2):164–176. 10.1037/1072-5245.12.2.164 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Gotink RA, Meijboom R, Vernooij MW, et al. 8-week mindfulness based stress reduction induces brain changes similar to traditional long-term meditation practice – a systematic review. Brain Cogn. 2016;108:32–41. 10.1016/j.bandc.2016.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Murakami H, Nakao T, Matsunaga M, et al. The structure of mindful brain. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e46377. 10.1371/journal.pone.0046377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Holzel BK, Carmody J, Evans KC, et al. Stress reduction correlates with structural changes in the amygdala. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2009;5(1):11–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.