Abstract

Objectives

This study’s objective was to assess the morbidity of self-employed workers in the food service industry, an industry with a large amount of occupational health risks.

Methods

A cross-sectional study, consisting of 437 participants, was conducted between 2011 and 2013 in Champagne-Ardenne, France. The health questionnaire included an interview, a clinical examination, and medical investigations.

Results

The study population consisted of 146 self-employed workers (not working for an employer) and 291 employees (working with employment contracts for an employer). Logistic regression analysis revealed that self-employed workers had a higher morbidity than employees, after adjusting for age (OR: 3.45; 95% CI: 1.28 to 9.25). Main adverse health conditions were joint pain (71.2% self-employed vs. 38.1% employees, p < 0.001), ear disorders (54.1% self-employed vs. 33.7%, employees, p < 0.001), and cardiovascular diseases (47.3% self-employed vs. 21% employees, p < 0.001).

Conclusions

The study highlights the need for occupational health services for self-employed workers in France so that they may benefit from prevention of occupational risks and health surveillance. Results were presented to the self-employed healthcare insurance fund in order to establish an occupational health risks prevention system.

Keywords: Occupational health, morbidity, food service

Introduction

In 2013, there were 2.8 million self-employed workers in France, a number that has been increasing each year. The difference between self-employed workers and employees is employment status. self-employed workers are working for themselves and not for an employer. Employees have an employment contract with an employer. Self-employed workers are covered by a specific healthcare insurance fund that differs from the national health insurance system. One key difference is that self-employed workers have no occupational health services and, therefore, have fewer benefits than employees. As a result, self-employed workers cannot obtain financial support via insurance for occupational diseases. There is a paucity of literature describing the health status of self-employed workers. This may be due to the lack of reliable information about occupational health in this population of self-employed workers [1]. The few studies that did focus on self-employed workers evaluate specific occupational diseases, and account for the overall health status [2–4]. The food service industry has numerous workplace hazards, including mechanical, physical, psychosocial, chemical, and work organizational exposures due to a difficult to regulate industry (reference) and physically and pyschologically demanding job tasks. Risk factors consist of prolonged standing position, walking long distances, material handling, repetitive work, extreme temperatures, noise, mental stress, exposure to chemicals, and shift- and night work. As a result of these hazards, work within the food service industry is associated with a high level of work-related injury [5]. Available data regarding occupational diseases in the food service industry indicate a high prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) [6]. A survey conducted in Norway’s offshore petroleum industry found that caterers have the second highest rate of MSDs [7]. Research also indicates that contact dermatitis affects 10% of the ALL workers in THE food service industry, which can be directly linked with exposure to wet work, and the irritant and allergen potential of a wide variety of materials and foods [8,9]. Other studies suggest a relationship between working in kitchens and respiratory symptoms, such as irritation due to exposure to cooking fumes [10]; however, precise causative agents have not been identified. There is also a possible relationship between air pollutants in kitchen environments and increased ischemic heart disease [11]. Research also shows a relation between alcohol consumption and work, with higher rates of alcohol abuse in specific industries, including the food service industry [12], and a higher prevalence of addiction among men. Additionally, the literature demonstrates a correlation between cooks and an increased risk of several cancers, notably cancers of the esophagus [13], lung and large intestine [14]. However, none of these studies in the food service industry have included a global health assessment of self-employed workers. Moreover, self-employed workers and employees do not have the same working conditions, which might influence their health status. self-employed workers have a positive perception of their health status, showing a low health insurance claims rate. This notwithstanding, they have a higher prevalence of long-term health conditions (which are exempt from co-payment). Consequently, we hypothesize that in the food service industry, the prevalence of diseases is significantly higher among self-employed workers than employees. The aim of this study was to assess the health status of self-employed workers in the food service industry in the Champagne-Ardenne region of France. The main objective was to identify the prevalence of morbidity in this population compared with employees in the same occupational branch. A secondary objective was to focus on the distribution of occupational diseases among workers in the service industry.

Materials and methods

A cross-sectional study of workers in the food service industry was conducted from June 2011 to December 2013 in the Champagne-Ardenne county of France.

Study population

Invitation letters to visit the Occupational Health Department of Reims Hospital were sent by the healthcare insurance fund to all self-employed workers working in food service in France. An occupational checkup, which included a health examination, and additional tests (spirometry test, tonal audiogram, urinary test), were administered to self-employed workers by this department, financed by their healthcare insurance fund. Self-employed workers were compared with employees working in the same occupational branch. This control group was recruited from several occupational health services in the same county during their bi-annual routine medical visit, which is obligatory for employees. Two employees were enrolled in the study for each self-employed worker. To be eligible, workers from both samples (self-employed workers and employees) had to belong to perform one of the following jobs: kitchen staff (cooks, kitchen assistants, dishwashers) or service staff (waiters, bartenders). The same exposures were involved in both groups. Participants had to be between 18 and 60 years of age and had to have at least one year of food service experience. Each participant was informed of the purpose of the study and provided written informed consent. A declaration was sent to the French supervisory authority. The protocol was submitted to the ethics committee. Questionnaires with missing data were excluded from analyses.

The database questionnaire

The study was conducted using an interviewer-administered health questionnaire and clinical examination. Occupational physicians completed the same questionnaire in both groups. The questionnaire included information about age, gender/sex, and seniority in food service, establishment type, and undertaken activities. Establishments were classified into three categories: restaurant, bar, or a combination of both. Tasks performed were divided into five categories: cooking, washing dishes/cleaning, table service, material handling, and entertainment. Versatile work was defined as the first four of these activities. Participants were questioned about the existence of smoking areas and ventilation systems in the establishment, as well as about work schedules (the hour the workday ended, and shift work, defined as more than two days per week starting before 7 am or ending after 9 pm). Participants were also asked about occupational exposure to passive smoking throughout their professional career. Lifestyle behaviors, such as daily alcohol consumption, particularly whether participants drank more than three glasses of alcohol per day, were obtained. The study population was divided into three groups concerning their smoking habits: current smokers, ex-smokers (cessation more than 3 years previously), and never smokers. The extent of smoking was expressed in packs per year.

The database included respiratory symptoms and ear, nose, and throat (ENT) disorders. Respiratory symptoms taken into account were dyspnea and coughing (daily cough for at least 3 months in a year). It was specified whether these symptoms seemed related to their work, and whether participants underwent respiratory explorations (less than 1 year previously) and treatment. ENT disorders were work-related rhinorrhea and the presence of abnormal difficulty hearing in a noisy atmosphere that required repeating the phrase. Atopy was discussed and suspected when there was a personal history of asthma or eczema during childhood [15]. Other questions covered MSDs (presence and location of joint pain), skin pathologies (diagnosis, location, work-related symptoms, checkup, and treatment) and sleep disorders. Data were also gathered regarding digestive complaints, such as abdominal pain, heartburn, and changes in bowel habits. Cardiovascular examination assessed hypertension and venous insufficiency of the lower limbs. Participants’ body mass index (BMI) was calculated; obesity was defined as BMI ≥30. Workers were asked about their vaccination status concerning tetanus, diphtheria and poliomyelitis (Td-Polio), and hepatitis (A and B). Perceived stress levels were assessed using two methods: asking the question “Do you feel stressed?” as a proxy for job strain [16] and a visual analogue scale, with 0 indicating no stress and 10 the worst possible stress. The scale yielded a subjective stress score between 0 and 10. A score ≥7 was deemed high [17]. The primary endpoint was overall morbidity, defined by the presence of at least one functional disorder or the identification of one physical symptom (i.e. stress, sleep disorders, respiratory symptoms, ENT symptoms, joint pain, skin pathologies, cardiovascular diseases, digestive complaints, obesity).

Medical investigations

Workers were asked to undergo medical investigations. A spirometry test was performed with a calibrated device for each worker. Measures recorded were forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), and forced expiratory flow as 25–75% of FVC (FEF 25–75). Results were reported as absolute values (FEV1 and FVC in liters, FEF 25–75 in liters per second) and as a percentage of predicted values based on age, sex/gender, weight, size, and ethnicity. The FEV1/FVC ratio was then calculated. Abnormal spirometries were classified into three categories. A diagnosis of obstructive syndrome required an FEV1/FVC ratio <70%. Restrictive syndrome was possible if FVC was <80%, and mixed syndrome when obstructive and restrictive syndromes were combined. FEF 25–75 was considered abnormal if the result was <70%. A tonal audiogram was administered with calibrated headphones in a soundproof, closed room. We focused on the minimum number of decibels heard at 4000 Hz for each ear, according to age and sex/gender. When hearing loss exceeded 30 decibels in at least one ear, the test result was considered abnormal. The urinary test was considered abnormal when blood, leukocyte, protein, or glucose was present. The visual test was considered abnormal when visual acuity was <6/10 for far- and near sight in at least one eye.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics

For the descriptive analysis, variables were expressed as means and standard deviations; Categorical variables were expressed as percentages. The Student’s t test was used to compare continuous variables, and the χ2 test was used to compare qualitative variables. When Student’s t test could not be used because statistical assumptions did not hold, the Mann–Whitney U test was applied. The χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test (when samples were too small) were used for categorical variables. Multivariable logistic regression analysis followed, adjusting for covariates to test the link between variables. The variables that were added into the models were significant in bivariate analysis or had p-values < 0.20 [18]. The results were expressed as the odds ratio (OR) and the 95% confidence interval (95% CI). For all statistical analyses, the significance threshold was fixed at p < 0.05. We used SPPS software version 12.0 for statistical analysis (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Principal component analysis

We built different groups through principal component analysis (PCA) [19], which were identified in several axes. The objective of the PCA was to answer the following questions: (1) which participants are the same (proximity between individuals); (2) which variables are similar/different; and (3) what are the relationships between variables? The following variables were used in the PCA: age, sex/gender, category, seniority, tasks performed, versatile work, cooking, washing dishes/cleaning, table service, material handling, entertainment, smoking areas, atopy, coughing, dyspnea, smoking habits, drinking habits, passive smoking, joint pain, sleep disorders, abnormal stress (visual analogue scale), morbidity, and obesity. Based on two axes built, we used these data to summarize the most important information with Frontier’s “broken stick” test [20]. These two axes were used to identify three groups, explaining 50% of the sample variance. For axis 1, the variables represent age, category, seniority, versatile work, morbidity, and joint pain; for axis 2, the variables represent tasks performed, cooking, and table service. For PCA, we used the open-source software Tanagra (Ricco Rakotomalala, Lyon, France)

Results

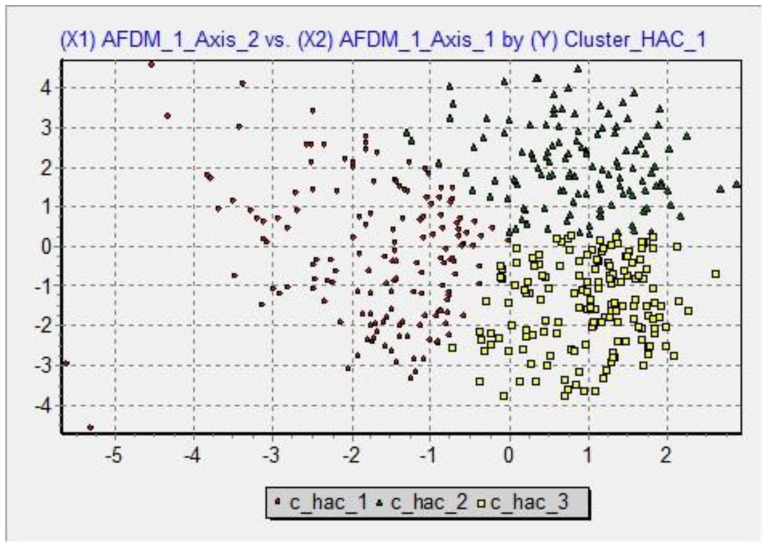

Fifty-three percent out of 272 self-employed workers who were invited to participate in the Occupational Health Department of Reims Hospital responded. For employees, 7 of 15 occupational health services in the county participated. After exclusion of questionnaires with missing data, there were 146 Self-employed workers and 291 employees. The distribution of age and seniority differed between groups. We observed significant differences concerning versatile work, work schedules, and exposure to passive smoking (Table 1). Restaurant was the most frequent establishment type in both groups (45.9% self-employed workers and 63.5% of employees), followed by bar (41.8% self-employed workers and 34.4% employees) and establishments comprising both (12.3% self-employed and 2.1% employees). Regarding the drinking and smoking habits of self-employed workers and employees, all criteria differed significantly between groups, except among never smokers. Self-employed workers exhibited greater consumption of alcohol than employees and a higher mean number of packs per year (Table 2). Table 3 shows the distribution of functional disorders and physical symptoms in both groups. The morbidity was 95.9% in self-employed workers vs. 75.3% in employees (p < 0.001). Although more self-employed workers responded “yes” to the question “do you feel stressed?” results of the stress visual analogue scale did not differ between self-employed workers and employees. The prevalence of sleep disorders was greater in self-employed workers. Prevalence of respiratory and ENT symptoms was also higher in self-employed workers, except for coughing and rhinorrhea. No significant differences were detected in respiratory exploration (4.1% self-employed workers vs. 1% for employees) or treatment (2.1% self-employed workers vs. 2.4% employees). We observed no significant difference concerning the relationship between dyspnea and work in both groups (4.1% for self-employed workers vs. 2.1% employees). The correlation between coughing and work was the same in both groups (0.7%). Atopy was significantly higher among employees vs. self-employed workers (13.7% vs. 6.8%, p < 0.05). Joint pain was more prevalent in self-employed workers in all anatomical sites. Cardiovascular diseases and digestive complaints were also more prevalent among self-employed workers. No significant differences were observed in obesity or skin pathologies (eczema, psoriasis, urticaria, mycosis, xerosis) between groups. Eczema was the most frequent dermatitis: 4.5% of employees vs. 3.4% for self-employed workers, with hands as the predominant location. We observed no significant difference concerning work-related dermatitis between the groups (2.1% self-employed workers vs. 1.4% employees). Likewise, no significant differences were detected in dermatological check-up (2.1% self-employed workers vs. 2.7% employees) or treatment (3.4% self-employed workers vs. 3.8% employees). Vaccination status differed significantly regarding Td-Polio (52.1% self-employed workers vs. 63.6% employees, p < 0.01) and type B hepatitis (13.7% self-employed workers vs. 34% employees, p < 0.001); however, no significant differences were observed regarding type A hepatitis (4.8% self-employed workers vs. 7.9% employees). Regarding the results of medical investigations, we did not observe differences in spirometry results or visual tests. The rates of abnormal audiogram and urinary tests were significantly higher for self-employed workers than employees (Table 4). The logistic regression analysis identified a strong association between the self-employed category and morbidity; an association between age and morbidity was also observed. Protective effects were observed between absence of stress and morbidity and female sex/gender and morbidity (Table 5). The PCA highlights three groups of workers (Figure 1): Cluster_hac_1, Cluster_hac_2, 277 and Cluster_hac_3.

Table 1.

Characteristics of self-employed and workers for employers.

| Self-employed (n = 146) | Workers for employers (n = 291) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (%) | |||

| Men | 52.1 | 58.1 | ns |

| Mean age in years (standard deviation) | 47 (8.6) | 31.7 (11.4) | <0.001 |

| Mean seniority in years (standard deviation) | 18.9 (10.6) | 10.4 (9.9) | <0.001 |

| Tasks performed (%) | |||

| Versatile work | 37.7 | 12.7 | <0.001 |

| Cooking | 69.2 | 63.2 | ns |

| Washing dishes/cleaning | 90.4 | 74.2 | <0.001 |

| Table service | 73.3 | 52.2 | <0.001 |

| Material handling | 84.2 | 58.8 | <0.001 |

| Entertainment | 15.1 | 9.3 | ns |

| Ventilation systems (%) | 62.3 | 91.8 | <0.001 |

| Smoking areas (%) | 4.1 | 5.8 | ns |

| Occupational exposure to passive smoking (%) | 71.9 | 36.4 | <0.001 |

| Work schedules | |||

| Mean hour of the workday’s end (standard deviation) | 21.55 (2.4) | 20.40 (3.1) | <0.001 |

| Shift work (%) | 88.4 | 77.7 | <0.01 |

Table 2.

Lifestyle behaviors of self-employed and workers for employers.

| Self-employed (n = 146) | Workers for employers (n = 291) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drinking habits (%) | |||

| Daily alcohol consumption | 19.9 | 3.8 | <0.001 |

| More than 3 glasses of alcohol per day | 9.6 | 0.7 | <0.001 |

| Smoking habits | |||

| Current smokers (%) | 28.1 | 51.5 | <0.001 |

| Ex-smokers (%) | 28.1 | 5.8 | <0.001 |

| Never smokers (%) | 43.8 | 42.7 | ns |

| Mean number of packs per year | 16.3 (13.9) | 8.9 (8.5) | <0.001 |

Table 3.

Distribution of functional disorders and physical symptoms among self-employed and workers for employers.

| Self-employed (n = 146) | Workers for employers (n = 291) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | ||

| Stress | |||

| Feeling stressed | 57.5 | 41.6 | <0.01 |

| Abnormal stress visual analogue scale | 17.8 | 15.5 | ns |

| Sleep disorders | 37 | 23.4 | <0.01 |

| Respiratory symptoms | 26 | 16.8 | <0.05 |

| Dyspnea | 17.8 | 11 | <0.05 |

| Coughing | 11.6 | 8.6 | ns |

| ENT symptoms | 54.1 | 33.7 | <0.001 |

| Rhinorrhea | 5.5 | 4.8 | ns |

| Difficulty hearing | 44.5 | 24.4 | <0.001 |

| Requiring repetition | 36.3 | 19.2 | <0.001 |

| Joint pain | 71.2 | 38.1 | <0.001 |

| Back | 42.5 | 18.2 | <0.001 |

| Upper limbs | 37 | 11.3 | <0.001 |

| Lower limbs | 32.2 | 15.1 | <0.001 |

| Skin pathologies | 12.3 | 10.3 | ns |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 47.3 | 21 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 36.3 | 12.4 | <0.001 |

| Venous insufficiency | 19.2 | 10.3 | <0.05 |

| Digestive complaints | 16.4 | 3.8 | <0.001 |

| Obesity | 16.4 | 13.7 | ns |

Table 4.

Results of medical investigations among self-employed and workers for employers.

| Self-employed (n = 146) | Workers for employers (n = 291) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | ||

| Spirometry results | |||

| Obstructive syndrome | 3.4 | 3.4 | ns |

| Restrictive syndrome | 17.8 | 14.1 | ns |

| Mixed syndrome | 0.7 | 0.7 | ns |

| Abnormal DEM | 8.2 | 9.6 | ns |

| Abnormal audiogram | 29.5 | 8.6 | <0.001 |

| Abnormal urinary strip | 26 | 7.2 | <0.001 |

| Abnormal visual test | 37.7 | 31.3 | ns |

Table 5.

Association between employment status and morbidity (n = 437).

| p | Odds ratio* (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Self-employed category | 0.01 | 3.45 (1.28–9.25) |

| Female gender | 0.05 | 0.57 (0.33–1.00) |

| Age | 0.02 | 1.04 (1.02–1.07) |

| Absence of stress | 0.01 | 0.81 (0.08–0.82) |

*Logistic regression analysis was used to examine the main explanatory variable, self-employed workers, adjusting for female/sex, age, and absence of stress (answered “no” to the question “do you feel stressed?”).

Figure 1.

Scatter plot with 3 groups of workers.

Cluster_hac_1

The group Cluster_hac_1 (“c_hac_1”) comprised 154 workers (35.2% of the study sample). These workers had a mean age of 35.2 years and a mean seniority of 11.5 years. There were more current smokers (59.7% c_hac_1 vs. 43.7% total study sample) and more worked in bars (13.6% vs. 5.5%), mainly working in table service (90.3% vs. 59.3%). Most did not engage in versatile work (98.1% vs. 78.9%) and did not cook (87.7% vs. 34.8%). Most workers neither washed dishes (35.1% vs. 20.4%) nor engaged in material handling (51.3% vs. 32.7%). The rate of sleep disorders was higher in this group (41.6% vs. 27.9%).

Cluster_hac_2

The group “c_hac_2” comprised 125 workers (28.6% of the study sample). This group was composed of older self-employed workers (mean age, 48 years, mean seniority, 22.2 years): 75.2% were self-employed vs. 33.4% in the study sample. There were more ex-smokers in this group (33.6% vs. 13.3%) and more had been exposed to passive smoking (71.2% vs. 48.3%). The rate of versatile work was higher (56% vs. 21.1%) and comprised cooking (95.2% vs. 65.2%), washing dishes (95.2% vs. 79.6%), and material handling (92.8% vs. 67.3%). Joint pain was more prevalent in this group (76.8% vs. 49.2%), as was obesity (28% vs. 14.6%). Morbidity was also higher in this group (97.9% 298 vs. 82.2%).

Cluster_hac_3

The group “c_hac_3” comprised 158 workers (36.2% of the study sample). These were younger employees (mean age, 29.6 years, mean seniority, 8 years). 95% were employees vs. 66.6% in the study population. They worked mainly in restaurants (76.6% vs. 57.7%). Members of this group were more likely to engage in cooking (93% vs. 65.2%) and more likely not to engage in table service (74.7% vs. 40.7%) or entertainment (97.5% vs. 307 88.8%). Most had not been exposed to passive smoking (79.1% vs. 51.7%) and they did not drink alcohol daily (100% vs. 90.8%). Most did not have stress based the visual analogue scale (93.7% vs. 83.8%) and were more likely not to have sleep disorders (89.9% vs. 72.1%) or joint pain (73.4% vs. 50.8%). There was a lower percentage of morbidity in this group (33.5% vs. 17.8%).

Discussion

The logistic regression analysis demonstrated that self-employed workers were associated with greater morbidity compared with employees, after adjusting for age (OR: 3.45, 95% CI 1.28 to 9.25). Two French studies have evaluated morbidity among self-employed workers; one study of house painters, hairdressers, and bakerpastry cooks reported 60% morbidity [2], while another study reported 89% morbidity among woodworkers [3]. Our findings suggest that self-employed workers in the food service industry have a higher morbidity (95.9%) than other French self-employed workers. The same questionnaire was used in both groups. The questionnaire was completed by doctors, as this method ensured better quality data than self-administered Questionnaires [21]. However, an observation bias may have existed because different occupational physicians performed the clinical examination; moreover, closed questions were not used during clinical examinations. Physicians were informed about the study and tended to examine participants as exhaustively as possible. However, additional examination was possible in the self-employed group because physicians believed they had a higher incidence of occupational disease than employees. This could have increased the strength of the association between morbidity and self-employment. Recruitment of self-employed workers may have introduced selection bias; indeed, they had the choice to consult or not consult an occupational physician. It is possible that self-employed workers experiencing serious medical problems do not always consult a physician; consequently, the morbidity among self-employed workers may be higher than reported. Conversely, the invitation to participate to the study may have acted as a catalyst for these patients to engage with the health system. However, it seems unlikely that self-employed workers would systematically overreport their health issues. The two study groups differed in age and seniority. Overall, the French self-employed population and French employees present nearly the same differences as study groups. There is a high proportion of young employees in the food service industry in France, with a mean age of 34 years in 2013. Self-employed workers become self-employed at approximately 40 years of age, which might explain their older average age and higher average seniority in the food service industry. Based on our findings, men are slightly more numerous than women in the French food service industry. Furthermore, the healthcare insurance fund of self-employed workers reports that 70% of self-employed are men; this figure is much higher than in our population of self-employed, but it concerns all self-employed categories. With regard to lifestyle behavior, a number of previous studies have reported a significant proportion of smokers and a high level of alcohol intake in the food service industry [12,22,23]. Self-employed workers exhibited a higher level of alcohol consumption. The prevalence of alcohol dependence is known to be higher in self-employed workers [24]. The self-employed group had a lower proportion of current smokers; however, the mean number of packs per year was significantly higher among the self-employed. A report describing tobacco consumption by occupation and activity sector in the French population has recorded similar results for self-employed workers. Exposure to passive smoking was more frequent among self-employed workers. The French smoke-free legislation in restaurants and bars since 2008 might explain this difference. The banning of smoking in public places is associated with improved respiratory health [25]. Versatile work was more frequent in the self-employed group. This result may reflect the fact that self-employed workers usually work alone or with only a few employees, so they undertake most of the job tasks. Shift work was more frequent among self-employed workers, and their workday ended later than employees. Unlike employees, self-employed workers do not have fixed schedules and spend more time at work. French self-employed workers performed on average 53 h per week, compared with 38 h per week for employees. This may also explain the higher level of sleep disorders for self-employed workers. There is evidence that the food service industry has high levels of occupational diseases, likely associated with physical and psychosocial hazards [26]. One problem with comparing data is the definition of food service, which varies largely from one study to another. Some studies include barmen, bakers, and butchers, while others restrict the definition to chefs, kitchen hands, and waitresses [27]. The survey highlights joint pain as the most prevalent problem among self-employed workers and employees, with the back as the predominant location. Previous studies have shown that MSDs are the most troubling occupational illness in the food service industry, with a higher risk for cooks and the lower back and shoulders as the two most frequent regions reported [28]. Indeed, the food service industry includes several risk factors for MSDs: repetitive manual work (chopping and dicing), awkward postures (neck flexion, reaching for supplies, small working places), and heavy lifting (food package, pots, dishes). In addition, psychosocial factors, such as long working hours, contribute to MSDs. A systematic review has recorded a wide range of MSD prevalence in the food service industry, from 3% to 86%; such a wide range might be due to the broad types of restaurants or the diversity in work methods and job titles [6]. The prevalence of joint pain was also higher among self-employed than employees (71.2% vs. 38.1%); this result might be related to more time spent at work, a larger workload, more stress, and more versatile positions (material handling, washing dishes/cleaning, and table service) among self-employed workers. Older age could also contribute to the higher levels of joint pain. The prevalence of dermatitis did not differ significantly between the two groups, which was in agreement with the literature [8]. Research indicates that workers in the food service industry are at risk of dermatitis from contact with workplace irritants (detergents, soaps, foods) and allergens (fruits, spices, food additives, nickel). The need for relatively frequent hand washing is an additional factor in the development of dermatitis [23]. We found that self-employed workers had more cardiovascular problems. A French study on self-employed workers showed a high prevalence of cardiovascular disease, which may have multifactorial origins, including organizational constraints of work, shift work, occupational stress, and passive smoking [29,30]. A previous study found a higher risk of venous diseases among self-employed workers because they stand for prolonged periods of time [31]. Previous heart and lung diseases, affecting mainly the self-employed group, may explain why this group of workers had to give up tobacco consumption. Digestive complaints were much more prevalent in the self-employed group. Eating quickly and at irregular hours might explain digestive symptoms of workers in the food service industry. An Indian survey reported that 9.4% restaurant workers had digestive complaints [32]. High stress and shift work may explain the greater prevalence of digestive complaints in this group. Shift work and night work are also well known to be associated with increased blood pressure and BMI. The visual analogue scale is particularly well suited to assess stress in occupational medicine [17]. Our questionnaire used two methods to assess stress. Results concerning the question “Do you feel stressed?” differed significantly, while the visual analogue scale did not differ between groups. However, results in both groups trended toward the same direction. Moreover, logistic regression analysis identified a positive association between absence of stress (A “No” answer to “Do you feel stressed?”) and lower morbidity. Self-employed workers might have more cardiovascular diseases, joint pain, digestives complaints, and psychosocial exposures because self-employment expose them to unpredictable, contingent, and fragmented work. Self-employment in the food service industry could be considered as a determinant of poor health. Logistic regression analysis indicated that four variables were significantly associated with higher or lower morbidity. The 95% CIs were unstable, especially for the self-employed category, which suggests that this study may not have been inadequately powered. Although a protective effect was observed between female sex/gender and morbidity, we cannot draw any conclusions because of the wide confidence interval and the cross-sectional study design [33]. Differences in morbidity are corroborated by the PCA, which identified three different groups, including a group of employees without illnesses and a group of self-employed workers with morbid conditions. Abnormal audiograms and ENT symptoms (except rhinorrhoea) were more prevalent among the self-employed group. The kitchen is a noisy environment, as are some bars; however, hearing protectors are not used. Many years of noise exposure might affect audiogram results and explain the higher rate of abnormal audiograms in self-employed workers. No significant differences in the spirometry results were detected between the groups; nevertheless, dyspnoea was more prevalent in self-employed workers. One explanation for dyspnoea could be that the workplaces of self-employed workers were less well ventilated. Interesting, the percentage of restrictive syndrome is identical to the percentage of obesity, a well-known link in the literature [34]. Nevertheless, the definition of restrictive syndrome requires total lung capacity measurements; FVC only provides only an orientation. The heavy operator dependence of the spirometry quality is another possible source of bias. This group should benefit from vaccination against tetanus and hepatitis A and B because of the high risk of injuries in this industry. Results showed that employees have better vaccine coverage, possibly because their occupational health service provides vaccinations. We also observed that the two groups had low percentages of hepatitis A vaccine, although this vaccine is recommended for individuals that work in food service.

Strengths and limitations

One of the study strengths was to examine the relation between self-employed workers and health in an understudied but ubiquitous industry. Likewise, few studies have taken into account the overall health status, using a global health assessment of self-employed workers in the food service industry. Studies conducted in several European countries have found participation rates that differ by country [35,36] with lower response rates in the “Latin” countries (Italy, France, and Spain). Our results showed group classes of workers with adequate response rates [36,37]. However, some methodological flaws must be considered in interpreting our findings. When the two groups are compared, age differences may partly explain some results, such as MSDs and cardiovascular diseases. Although our recruitment methodology was unable to avoid this bias, this factor was controlled by logistic regression. Morbidity was considered present when at least one of the physiological systems explored in our questionnaire was affected. The variable thus constructed was a sensitive indicator for pathologic processes but should be interpreted with caution due to its heterogenous nature. The healthy worker effect is another possible source of bias. Indeed, self-employed workers might have previously left employment because of difficulties associated with an illness, so that only healthy employees remain. Thus, this study may underestimate the true morbidity of self-employed workers in the food service industry [38]. Some measures (e.g. audition) could have been executed in different conditions for employees and self-employed workers. Further studies should measure outcomes in the same conditions whenever possible. Finally, our results underscore the need to promote occupational health and safety among self-employed workers. Due to the lack of occupational health services for self-employed workers, they probably have less knowledge about enacting preventive measures at work. There are a variety of actions that can be taken in the workplace to reduce the risk of occupational diseases.

Therefore, it is important that self-employed workers benefit from this system by obtaining information about occupational health risks and by implementing occupational health surveillance. Results were presented to the self-employed healthcare insurance fund in order to set up an occupational health risks prevention system.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare self-employed workers and Employees in the food service industry. Our study demonstrated that self-employed workers have a higher morbidity than employees. This result is confirmed by the logistic regression analysis after adjusting for age. The difference identified could be explained by several factors: a larger variety of tasks performed, longer work schedules, and higher stress for self-employed. Conversely, the self-employed group had greater task variation, which might reduce morbidity effects [39]. The lack of occupational health services also contributes to this difference. In addition, the present study helps to provide a broader picture of occupational diseases in the food service industry. Joint pain, ENT symptoms and cardiovascular diseases were the most frequent dysfunctions in the two groups. Further studies could explore the morbidity of employees that are also managers. This study emphasizes the need for occupational health services for self-employed workers, with occupational health surveillance and prevention strategies in order to reduce occupational risks.

Copyright

The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, a worldwide licence to the Publishers and its licensees in perpetuity, in all forms, formats and media (whether known now or created in the future), to (i) publish, reproduce, distribute, display, and store the Contribution, (ii) translate the Contribution into other languages, create adaptations, reprints, include within collections and create summaries, extracts and/or, abstracts of the Contribution, (iii) create any other derivative work(s) based on the Contribution, (iv) to exploit all subsidiary rights in the Contribution, (v) the inclusion of electronic links from the Contribution to third party material where-ever it may be located; and, (vi) licence any third party to do any or all of the above.

Detail of contributors

Study concept and design (MG, FD, SS); Acquisition of data (MG, JS, SS); Statistical analysis (MG, SS); Analysis and interpretation of data (MG, SS, FD, JS); Drafting of the manuscript (MG, SS); Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content (MG, FD, JS, SS). SS had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Transparency declaration

SS affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Ethics approval

Waived.

Funding

University Hospital of Reims & Hospices Civils de Lyon – Lyon 1 University. Researchers had full intellectual independence regarding their research.

Disclosure statement

All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: all authors had financial support from Hospices Civils de Lyon teaching hospital and University Hospital of Reims for conducting independently the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

References

- [1].Mirabelli MC, Loomis D, Richardson DB. Fatal occupational injuries among self-employed workers in North Carolina. Am J Ind Med. 2003;44(2):182–190. 10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lesage F-X, Deschamps F. Évaluation de l’état de santé d’une population d’artisans et de commerçants (health assessment of self-employed and tradesmen). Arch Mal Prof Environ. 2005;66(5):456–464. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lesage F-X, Salles J, Deschamps F. Self-employment in joinery: an occupational risk factor? Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2014;27(3):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Deschamps F, Langrand J, Lesage F-X. Health assessment of self-employed hairdressers in France. J Occup Health. 2014;56:157–163. 10.1539/joh.13-0139-FS [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gleeson D. Health and safety in the catering industry. Occup Med Oxford Engl. Sep. 2001;51(6):385–391. 10.1093/occmed/51.6.385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Xu Y-W, Cheng ASK, Li-Tsang CWP. Prevalence and risk factors of work-related musculoskeletal disorders in the food service industry: a systematic review. Work. 2013;44(2):107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Morken T, Mehlum IS, Moen BE. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders in Norway’s offshore petroleum industry. Occup Med (London). 2007;57(2):112–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Smith TA. Occupational skin conditions in the food industry. Occup Med (London). 2000;50(8):597–598. 10.1093/occmed/50.8.597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wood BP, Greig DE. Food service industry. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15(4):567–571. 10.1016/S0738-081X(97)00003-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Svendsen K, Sjaastad AK, Sivertsen I. Respiratory symptoms in kitchen workers. Am J Ind Med. 2003;43(4):436–439. 10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sjögren Bengt BL. Ischemic heart disease among cooks, cold buffet managers, kitchen assistants, and wait staff. Scand J Work Environ Health Suppl. 2009;7:24–29. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Mangili A. Alcohol and working. G Ital Med Lav Ergon. 2004;26(3):255–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Chow WH, McLaughlin JK, Malker HS, et al. Esophageal cancer and occupation in a cohort of swedish men. Am J Ind Med. 1995;27(5):749–757. 10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Coggon D, Wield G. Mortality of army cooks. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1993;19(2):85–88. 10.5271/sjweh.1493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Illi S, von Mutius E, Lau S, et al. The natural course of atopic dermatitis from birth to age 7 years and the association with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. mai. 2004;113(5):925–931. 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.01.778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ota A, Masue T, Yasuda N, et al. Association between psychosocial job characteristics and insomnia: an investigation using two relevant job stress models – the demand-control-support (DCS) model and the effort-reward imbalance (ERI) model. Sleep Med. 1 juill 2005;6(4):353–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lesage F-X, Berjot S, Deschamps F. Clinical stress assessment using a visual analogue scale. Occup Med (London). 2012;62(8):600–605. 10.1093/occmed/kqs140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hosmer Jr. DW, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX. Applied logistic regression. 3rd ed Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2013. p. 500 (Wiley series in probability and statistics). 10.1002/9781118548387 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Falissard B. Analysis of questionnaire data with R. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2012. p. 269. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Frontier S. Etude de la décroissance des valeurs propres dans une analyse en composantes principales : comparaison avec le modèle du bâton brisé. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 1976;25:67–75. 10.1016/0022-0981(76)90076-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kilbom A. Assessment of physical exposure in relation to work-related musculoskeletal disorders–what information can be obtained from systematic observations? Scand J Work Environ Health. 1994;20:30–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Benavides FG, Ruiz-Forès N, Delclós J, et al. Consumption of alcohol and other drugs by the active population in Spain. Gac Sanit. 2013;27(3):248–253. 10.1016/j.gaceta.2012.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hannerz H, Tüchsen F, Kristensen TS. Hospitalizations among workers for employers in the Danish hotel and restaurant industry. Eur J Public Health. 2002;12(3):192–197. 10.1093/eurpub/12.3.192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Harford TC, Parker DA, Grant BF, et al. Alcohol use and dependence among employed men and women in the United States in 1988. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1992;16(2):146–148. 10.1111/acer.1992.16.issue-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Eisner MD, Smith AK, Blanc PD. Bartenders' respiratory health after establishment of smoke-free bars and taverns. JAMA. 1998;280(22):1909–1914. 10.1001/jama.280.22.1909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gleeson D. Health and safety in the food service industry. Occup Med (London). 2001;51(6):385–391. 10.1093/occmed/51.6.385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Blair PW, Deborah EG. Food service industry. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15(4):567–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Tsai JH-C. Chinese immigrant restaurant workers’ injury and illness experiences. Arch Environ Occup Health. 2009;64(2):107–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Teo S, Teik-Jin Goon A, Siang LH, et al. Occupational dermatoses in restaurant, food service and fast-food outlets in Singapore. Occup Med (London). 2009;59(7):466–471. 10.1093/occmed/kqp034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Bréchon F, Czernichow P, Leroy M, et al. Chronic diseases in self-employed french workers. J Occup Environ Med. 2005;47(9):909–915. 10.1097/01.jom.0000169566.45853.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Benigni JP, Cazaubon M, Kasiborski F, et al. Chronic venous disease in the male. An epidemiological survey. Int Angiol. 2004;23(2):147–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kokane S, Tiwari RR. Occupational health problems of highway restaurant workers of Pune, India. Toxicol Ind Health. 2011;27(10):945–948. 10.1177/0748233711399322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Punnett L, Wegman DH. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders: the epidemiologic evidence and the debate. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. févr 2004;14(1):13–23. 10.1016/j.jelekin.2003.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kessler R, Chaouat A, Schinkewitch P, et al. The obesity-hypoventilation syndrome revisited: a prospective study of 34 consecutive cases. Chest. 2001;120(2):369–376. 10.1378/chest.120.2.369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].O’Neill TW, Marsden D, Matthis C, et al. Survey response rate: national and regional differences in a European multicentre study of vertebral osteoporosis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1995;49:87–93. 10.1136/jech.49.1.87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Siemiatycki J, Campbell S. Nonresponse bias and early versus all responders in mail and telephone surveys. Am J Epidemiol. 1984;120:291–301. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Goldberg M, Chastang JF, Leclerc A, et al. Socioeconomic, demographic, occupational, and health factors associated with participation in a long-term epidemiologic survey: a prospective study of the French GAZEL cohort and its target population. Am J Epidemiol. Aug 15 2001;154(4):373–384. 10.1093/aje/154.4.373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Rothman K, Greenland S, Lash T. Modern Epidemiology. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Mathiassen SE. Diversity and variation in biomechanical exposure: what is it, and why would we like to know? Appl Ergon. juill 2006;37(4):419–427. 10.1016/j.apergo.2006.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]