Abstract

Primary care physicians encounter a broad range of problems and therefore require a broad knowledge to manage patients. They encounter patients at early undifferentiated stage of a disease and most of the presentations are due to non sinister problems but in minority of patients same presentations could be due to serious conditions. One of the main tasks of a primary care doctor is to marginalize the risk of missing these serious illnesses. To achieve this they can look for red flags which are clinical indicators of possible serious underlying condition. Red flags are signs and symptoms found in the patient's history and clinical examination. Evaluation of red flags is of paramount important as decision making is mainly dependent on history and examination with the availability of minimal investigatory facilities at primary care level. Some Red flags like loss of weight and loss of appetite are general in nature and could be due to many pathologies while hematemesis and melena are specific red flags which indicate GIT bleeding. All red flags, whether highly diagnostic or not, general or specific, warn us the possibility of life-threatening disorders. The term ‘red flag’ was originally associated with back pain and now lists of red flags are available for other common presentations such as headache, red eye and dyspepsia as well. Identification of red flags warrant investigations and or referral and is an integral part of primary care and of immense value to primary care doctors.

Keywords: General practice, primary care, red flags, serious diseases

Introduction

General practice/primary care is the first medical contact within the health-care system, providing open and unlimited access, dealing with all health problems regardless of the age, sex, or any other characteristic of the person concerned.[1] Therefore, primary care physicians require a broad knowledge of medicine and the role of the general practitioner (GP) in patient management is problem recognition and decision-making rather than arriving at a definitive conclusion.

In primary care, patients often present with nonspecific symptoms and the incidence of serious illness is low. Differentiating between innocent symptoms and a rare, but serious organic disease is a challenge for the primary care physician. Unnecessary referrals and diagnostic testing need to be balanced against the risk of missing a diagnosis.[2] The red flag concept is of immense value in facing this challenge.

The one main aim of the GP in the process of management is to marginalize danger by recognizing and responding to signs and symptoms of possible serious illness. In primary care, they have limited access to perform investigations to catch up serious medical conditions,[3] but for each presentation, primary care physician can look for red flags which are clinical indicators of possible serious underlying condition requiring further medical intervention.[4] The presence of red flags indicates the need for investigations and or referral. Essentially red flags are signs and symptoms found in the patient history and clinical examination that may tie a disorder to a serious pathology.[5] Hence, the evaluation of red flags is an integral part of primary care and can never be underestimated.

The term “red flag” was originally associated with back pain. They were actually designed for use in acute low back pain, but the underlying concept can be applied more broadly in any presentation. The first catalog of red flags for back pain appeared in the literature in the early 1980s, and since then numerous lists have been compiled.[6]

Recognizing and managing “red flags” in clinical medicine also presents a challenge[6] since all the red flags do not have an equal diagnostic power. Some are highly diagnostic while others are far less diagnostic. Even the presence of far less diagnostic red flags does not exclude the possibility of serious pathology so one must assume its presence until proven otherwise.[7]

Some red flags are general in nature because they have several possible explanations. General red flags direct the clinicians to recognize a serious illness even though the exact disease is not known. Unexplained weight loss is one such general red flag.

Specific red flags signal-specific illnesses and present in specific anatomical regions. When a chronic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug user presents with coffee ground vomiting, it is a specific red flag for upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to peptic ulceration.

Even common and mild signs and symptoms can indicate a serious illness when combined with other specific signs and symptoms. Constipation is not a red flag by itself, but when it is combined with painless per rectal bleeding, the combination is a red flag for possible colonic cancer.

But all red flags, whether highly diagnostic or not, general or specific, warn us the possibility of disabling and life-threatening disorders. Hence, it is important to remember that they only need to be sufficiently suggestive to compel us to rule out a serious condition to be a red flag.[7]

There is confusion however as different guidelines have produced a different set of red flags for the same presentation. Koes et al. in their review of 8 back pain guidelines,[8] revealed that none of the eight guidelines they reviewed, endorsed the same set of red flags. In addition, guidelines generally provide no information on the diagnostic accuracy of a particular red flag, which limits their value in clinical decision-making. However, evaluation of red flags is a useful way of identifying patients with a higher likelihood of sinister pathology. It is essential to use the clinical acumen to overcome the deficiencies.

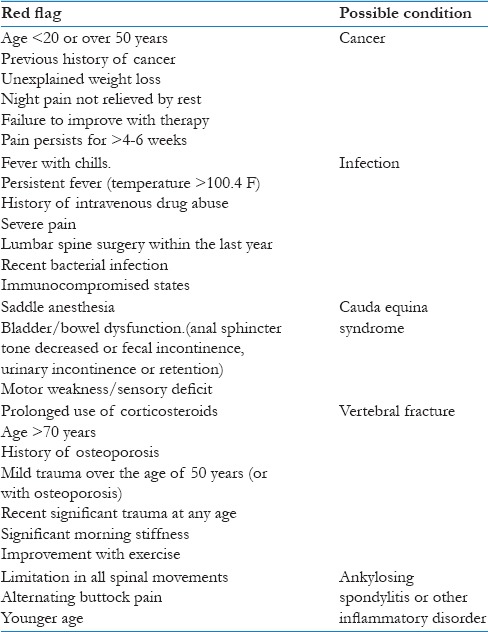

Backache

Most adults experience low back pain at some point during their lives, making it one of the most common conditions encountered in primary care.[9,10] Most low back pain in primary care is mechanical in nature and does not signify a dangerous underlying abnormality, but minority indicates a serious condition, such as inflammatory disease, fracture, or cancer.[11] Among low back pain patients in primary care between 1% and 4% will have a spinal fracture[12] and in <1% malignancy, primary tumor, or metastasis.[13]

Identification of serious pathologies, when they exist, is important in the clinical assessment and further assessment and specific treatment is usually required.[11,14] For instance, early detection of spinal malignancy could prevent further spread of metastatic disease.[15] Identification of spinal fracture will prevent the prescription of treatment such as manual therapy, which is contraindicated,[16] as well as directing the patient toward further testing and treatment of underlying disease (such as osteoporosis). Despite the potential consequences of a late or missed diagnosis of these serious pathologies, their low prevalence in primary care settings does not justify routine, ancillary testing of patients presenting with low back pain. Therefore, it is a challenge for the primary care doctor to detect and not to miss patients with serious underlying pathologies. Evaluation of red flags is of immense value in such instances to a busy primary care physician [Table 1].[17,18]

Table 1.

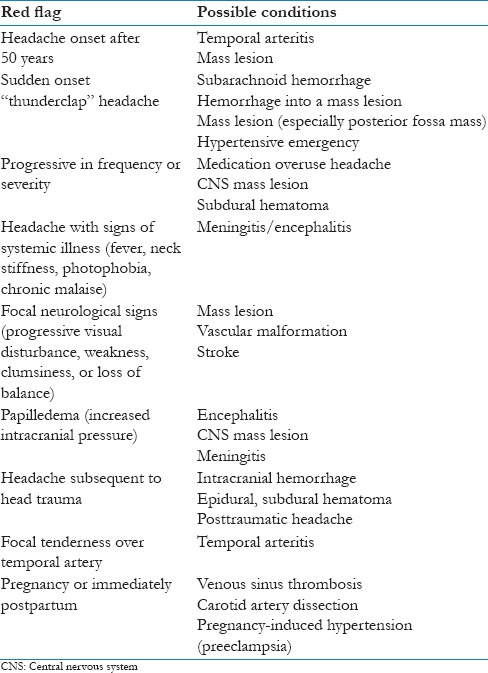

Headache

Headache is among the most common pain problems encountered in family practice. One epidemiologic study found that 95% of young women and 91% of young men experienced a headache during a 12-month period; 18% of these women and 15% of these men consulted a physician because of their headache.[19]

It is diagnostically and therapeutically useful to consider headaches being divided into two categories as primary and secondary. Primary headaches, which include migraine, tension-type headache, and cluster headache, are benign. These headaches are usually recurrent and have no organic disease as their cause. Secondary headaches are caused by underlying organic diseases ranging from sinusitis to subarachnoid hemorrhage.[20] The primary task of the family physician is to determine whether a patient has an organic, potentially life-threatening cause of headache [Table 2].[18,21]

Table 2.

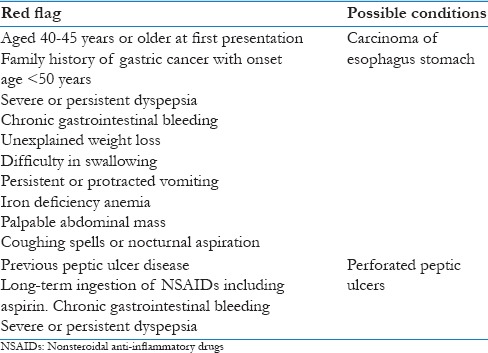

Red flags of Symptoms Suggestive of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Gastroesophageal reflux disease can manifest in a multitude of symptoms, the most common being heartburn and regurgitation. Even though its benign most of the time these symptoms also could be due to a sinister pathology. Screening for red flags helps to identify sinister pathologies [Table 3].22

Table 3.

Red flags for gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms[22]

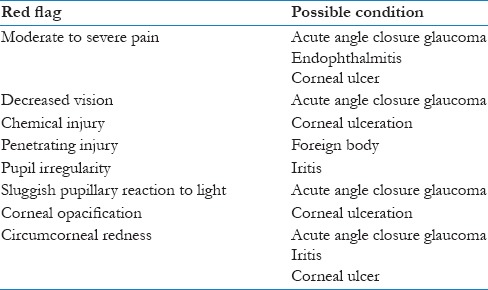

Red Eye

The most likely cause of a red eye in patients who present to general practice is conjunctivitis. However, red eye can also be a feature of a more serious eye condition, in which a delay in treatment due to a missed diagnosis can result in permanent visual loss.

Most general practice clinics will not have access to specialized equipment for eye examination, for example, a slit lamp and tonometer for measuring intraocular pressure, and some conditions can only be diagnosed using these tools. Therefore, primary care management relies on noting key features to identify which patients require referral for ophthalmological assessment [Table 4].[23,24] In general, a patient with a unilateral presentation of a red-eye suggests a more serious cause than a bilateral presentation.[23]

Table 4.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Allan J, President B, Crebolder H. The European Definition of General Practice/Family Medicine. 3rd ed. Barcelona: WHO Europe Office; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holtman GA, Lisman-van Leeuwen Y, Kollen BJ, Escher JC, Kindermann A, Rheenen PF, et al. Challenges in diagnostic accuracy studies in primary care: The fecal calprotectin example. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:179. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson C. Book review. In: Wong WC, Lindsay M, Lee A, editors. Diagnosis and management in primary care: A problem-based approach. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press; 2008. Asia Pac J Public Health 2009;21:346. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang G. Book review guide to assessing psychosocial yellow flags in acute low back pain: Risk factors for long-term disability and work loss. In: Kendall NA, Linton SJ, Main CJ, editors. Wellington, New Zealand: Accident Rehabilitation and Compensation Insurance Corporation of New Zealand and the National Health Committee; 1997. p. 22. Public Domain. J Occup Rehabil 1997;7:249.50. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lamont AC, Alias NA, Win MN. Red flags in patients presenting with headache: Clinical indications for neuroimaging. Br J Radiol. 2003;76:532–5. doi: 10.1259/bjr/89012738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Welch E. Red flags in medical practice. Clin Med (Lond) 2011;11:251–3. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.11-3-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anzaldua D. An Acupuncturist's Guide to Medical Red Flags & Referrals. Boulder, CO: Blue Poppy Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koes BW, van Tulder M, Lin CW, Macedo LG, McAuley J, Maher C, et al. An updated overview of clinical guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care. Eur Spine J. 2010;19:2075–94. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1502-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deyo RA, Tsui-Wu YJ. Descriptive epidemiology of low-back pain and its related medical care in the United States. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1987;12:264–8. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198704000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Côté P. The Saskatchewan health and back pain survey. The prevalence of low back pain and related disability in Saskatchewan adults. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1998;23:1860–6. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199809010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, Herbert RD, Cumming RG, Bleasel J, et al. Prevalence of and screening for serious spinal pathology in patients presenting to primary care settings with acute low back pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:3072–80. doi: 10.1002/art.24853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM. A systematic review identifies five “red flags” to screen for vertebral fracture in patients with low back pain. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:110–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Downie A, Williams CM, Henschke N, Hancock MJ, Ostelo RW, de Vet HC, et al. Red flags to screen for malignancy and fracture in patients with low back pain: Systematic review. BMJ. 2013;347:f7095. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f7095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chou R, Qaseem A, Owens DK, Shekelle P. Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Diagnostic imaging for low back pain: Advice for high-value health care from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:181–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-3-201102010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loblaw DA, Perry J, Chambers A, Laperriere NJ. Systematic review of the diagnosis and management of malignant extradural spinal cord compression: The cancer care ontario practice guidelines initiative's neuro-oncology disease site group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2028–37. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waddell G. The back Pain Revolution. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maher C, Williams C, Lin C, Latimer J. Managing Low Back Pain in Primary Care – Australian Prescriber. 2015. [Last accessed on 2015 Oct 13]. Available from: http://www.australianprescriber.com/magazine/34/5/128/32 .

- 18.Simon C, Everitt H, Kendrick T. Oxford Handbook of General Practice. 3rd ed. Oxford, GB: Oxford University Press; 2010. Assessment of headache; p. 560. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parizel PM, Voormolen M, Van Goethem JW, van den Hauwe L. Headache: When is neuroimaging needed? JBR-BTR. 2007;90:268–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solomon S. Diagnosis of primary headache disorders. Validity of the international headache society criteria in clinical practice. Neurol Clin. 1997;15:15–26. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8619(05)70292-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clinch CR. Evaluation of acute headaches in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:685–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barbezat G. Managing heartburn undifferentiated dyspepsia and functional dyspepsia in general practice. Best Pract J. 2007;4:10–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cronau H, Kankanala RR, Mauger T. Diagnosis and management of red eye in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81:137–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simon C, Everitt H, Kendrick T. Oxford Handbook of General Practice. 3rd ed. Oxford, GB: Oxford University Press; 2010. The red eye and conjuctivitis; p. 964. [Google Scholar]