Abstract

Purpose:

This joint position statement, by the Indian Association of Palliative Care (IAPC) and Academy of Family Physicians of India (AFPI), proposes to address gaps in palliative care provision in the country by developing a community-based palliative care model that will empower primary care physicians to provide basic palliative care.

Evidence:

India ranks very poorly, 67th of 80 countries in the quality of death index. Two-thirds of patients who die need palliative care and many such patients spend the last hours of life in the Intensive care unit. The Indian National Health Policy (NHP) 2017 and other international bodies endorse palliative care as an essential health-care service component. NHP 2017 also recommends development of distance and continuing education options for general practitioners to upgrade their skills to provide timely interventions and avoid unnecessary referrals.

Methods:

A taskforce was formed with Indian and International expertise in palliative care and family medicine to develop this paper including an open conference at the IAPC conference 2017, agreement of a formal liaison between IAPC and AFPI and wide consultation leading to the development of this position paper aimed at supporting integration, networking, and joint working between palliative care specialists and generalists. The WHO model of taking a public health approach to palliative care was used as a framework for potential developments; policy support, education and training, service development, and availability of appropriate medicines.

Recommendations:

This taskforce recommends the following (1) Palliative care should be integrated into all levels of care including primary care with clear referral pathways, networking between palliative care specialist centers and family medicine physicians and generalists in community settings, to support education and clinical services. (2) Implement the recommendations of NHP 2017 to develop services and training programs for upskilling of primary care doctors in public and private sector. (3) Include palliative care as a mandatory component in the undergraduate (MBBS) and postgraduate curriculum of family physicians. (4) Improve access to necessary medications in urban and rural areas. (5) Provide relevant in-service training and support for palliative care to all levels of service providers including primary care and community staff. (6) Generate public awareness about palliative care and empower the community to identify those with chronic disease and provide support for those choosing to die at home.

Keywords: Academy of Family Physicians of India, community, Indian Association of Palliative Care, integration, palliative care, position statement

Introduction

The United Nations (UN) Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural rights report that it is essential to provide “attention and care to chronically and terminally ill persons, sparing them avoidable pain, and enabling them to die with dignity.”[1] Despite being endorsed as an essential health-care service by the Indian National Health Policy (NHP) in 2017[2] and other international bodies; UN, Worldwide Palliative Care Association and Human Rights Watch,[3] palliative care is not available to most people who need it in India. NHP 2017 also recommends creation of distance and continuing education programs for general practitioners in both private and public sectors, which would upgrade their skills at providing basic palliative care at the community level in a timely manner and avoid unnecessary referrals.[2]

At the World Health Assembly (WHA) resolution WHA67.19 (2014), Geneva, a seminal resolution was passed where member nations committed to integrate palliative care into their National Health Systems and improve access to palliative care with emphasis on primary health care, community, and home-based care. Integration into preservice curricula for health professionals was identified as crucial to this process.[3]

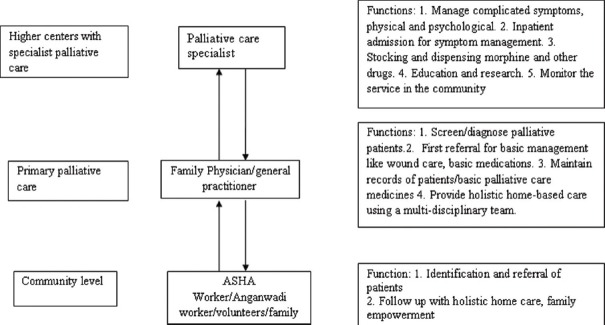

The World Health Organization (WHO) Public Health Strategy for Palliative Care highlights four crucial components for effective delivery of palliative care; appropriate policies, adequate drug availability, education of health-care workers, and public and implementation of palliative care services at all levels [Figure 1].[4]

Figure 1.

The World Health Organization Public Health Strategy for Palliative Care

The International Hospice and Palliative Care Association led a program in 2012 to develop a list of Essential Practices in Palliative Care to help define appropriate generalist and primary palliative care and improve the quality of care delivered globally. The 23 essential practices had different levels of intervention under the following domains of care: Physical care, psychological/emotional/spiritual care, care planning and coordination, and communication issues.[5] More recently, the Lancet Commission on palliative care[6] has suggested a new category of serious health-related suffering to help identify and quantify palliative care needs. It also defined essential package to contain the inputs for safe and effective provision of essential palliative care and pain relief interventions to alleviate physical and psychological symptoms, including the medicines and equipment that can be safely prescribed or administered in a primary care setting. The list of essential medicines in the essential package is based on the WHO's list of essential medicines.[7]

This joint position paper describes the vital contribution of palliative care in achieving universal health coverage; it will focus on the Indian context and the need for education and training in the core competencies appropriate for provision of generalist palliative care. The task force was formed and brainstormed on integration, networking, and bringing specialists and generalist physicians under one umbrella, firstly at a conference, and then through developing this paper electronically. The Indian Association of Palliative Care (IAPC) and AFMC together make recommendations that can be adopted jointly to support the growth of palliative care education and services across primary care physicians in India.

Palliative care

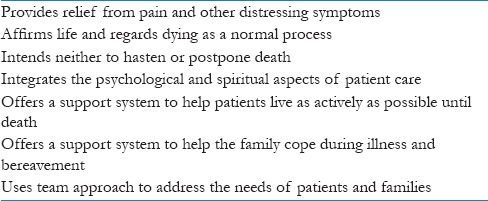

The WHO defines palliative care as “an approach that improves the quality of life (QOL) of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual.”[8] The key principles and components of palliative care are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Principles of palliative care

Currently, there are over 908 palliative care centers in India, which are accessible to <1% of a population of over 1.3 billion population.[9] India ranks at the bottom of the Quality of Death Index. The Quality of Death Index, commissioned by the Lien Foundation, Singapore, measured the quality of palliative care in 80 countries around the world, using 20 quantitative and qualitative indicators across five categories: The Palliative and Healthcare environment, human resources, the affordability of care, and the level of community engagement; while the UK and the US ranked 1st and 9th, respectively; India ranked 67th.[10] In addition, in the Indian context, increasing numbers of patients spend their last days in intensive care settings without adequate goal planning and perhaps futile and expensive interventions despite excellent joint work from the IAPC and Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine.[11] The barriers to palliative care include lack of community awareness, inadequate trained health-care providers, and difficulty in opioid access.

Palliative care needs are evident not only in cancer but also in other diseases including chronic infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis; solid organ failure such as kidney failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cardiac failure; and neurodegenerative diseases including Parkinson's disease, motor neuron disease, and Alzheimer's disease.[12] There is evidence that palliative care helps patients and families navigate through the difficult disease process, facilitates treatment decision-making and advance care planning, promotes health-care utilization, reduces health costs by reducing length of stay in hospital and hospital admissions, enhances patient and caregiver satisfaction, and improves QOL and survival.[13,14,15,16]

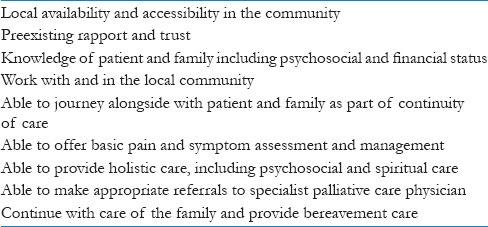

The overwhelming need and challenges for palliative care in India can be addressed through an internationally recognized approach termed, “Primary palliative care”.[17] In countries where primary care system is in place, general practitioners deliver the majority of palliative care to patients in the last year of life.[18] Screening of disease, delivering bad news, offering family counseling, guiding in treatment decision-making, offering good and comprehensive care by networking with other GPs, specialists, other community health/social worker and volunteers, and providing domiciliary palliative care are very important aspects of family medicine practice. Thus, empowered family physicians and community health teams are an important fulcrum for continuity of palliative care [Table 2]. Integration of palliative care into the practice of family medicine will also ensure that quality care is provided to the vulnerable population more tailored to the patient's choice.[19]

Table 2.

Advantages of incorporating palliative care in the practice of family medicine

Policy and Advocacy

Palliative care should be available wherever the need is greatest and this will often mean domiciliary care, especially at the end of life. This is difficult to provide with full coverage by specialist teams and hence the integrated approach empowering and working with generalists, community teams, and family physicians is crucial. In our country, specialists in hospitals work in isolation from generalists in the community. This disjointed approach results in increased burden and suffering among patients and family as they have to rush to the specialists even for minor ailments. There is thus a necessity for good referral pathways and communication between specialists and generalists to ensure continuity of care.

Education

As a first step, it is imperative to agree the core competencies required for generalists and family physicians to identify and treat patients who might benefit from palliative care and to design a model robust training module format [Appendix 1]. This will include Level 1 and 2 competencies as defined in the WHA resolution. The training should be flexible and take into account the time constraints for general practitioners in the community, who often have overwhelming workloads. The competencies and training framework must be accredited to both the national bodies of palliative care and family physician to add credibility for practice. Every state body must take the responsibility at their level to conduct regular training programs and devise a mechanism for networking and ensuring continuity of education including empowering family physicians as trainers and providing opportunities for clinical rotations in specialist palliative care settings. While this collaboration gains momentum, the national bodies of palliative care and family physicians must persuade the Medical Council of India (MCI) to ensure that palliative care is made mandatory in the curricula of undergraduate (MBBS) and postgraduation in family medicine.

Service development

The national bodies of palliative care and family physicians should design standard operating procedures for collaboration between the specialist and generalist physicians, define roles and responsibilities of family physicians, and agree pathways for referral to and from generalist to specialist which include other key members of the multidisciplinary team. There should be meticulous documentation of care at follow-up and cross-referrals as this will ensure seamless integration of services. Regular meetings at state and national levels will further strengthen the opportunities for better collaboration.

Research collaboration

The national bodies of palliative care and family physicians should conduct audits of the work done and expand the scope for innovation and improvisation in the existing practices. Research is an integral component of service and education to ensure quality, evidence-based care that is focused on the needs of patients and families. Both the associations should collaborate to design research protocols to identify and care for patients in primary care and understand the patient and family experience, using relevant outcome measures.

Education and Training

Palliative care education

Education is one of the pillars of the public health strategy for palliative care.[4] This should include education of professional, nonprofessional team members, and laypersons, who assist as semi-skilled home-based caregivers or family caregivers. The training must be appropriate and holistic including physical, psychosocial, and spiritual aspects with an emphasis on empowering basic palliative care practice. Particular care should be taken to educate and inform opinion leaders in health departments, government services, and community leaders on the benefits and successes in palliative care as affording dignity[20] and respecting human rights[21] and to encourage those responsible for budgets and services to include palliative care in budgets. Those responsible for the drafting and implementation of policy and guidelines should be made aware of the benefits of palliative care and the international and national imperatives to meet the WHA resolution targets.[3]

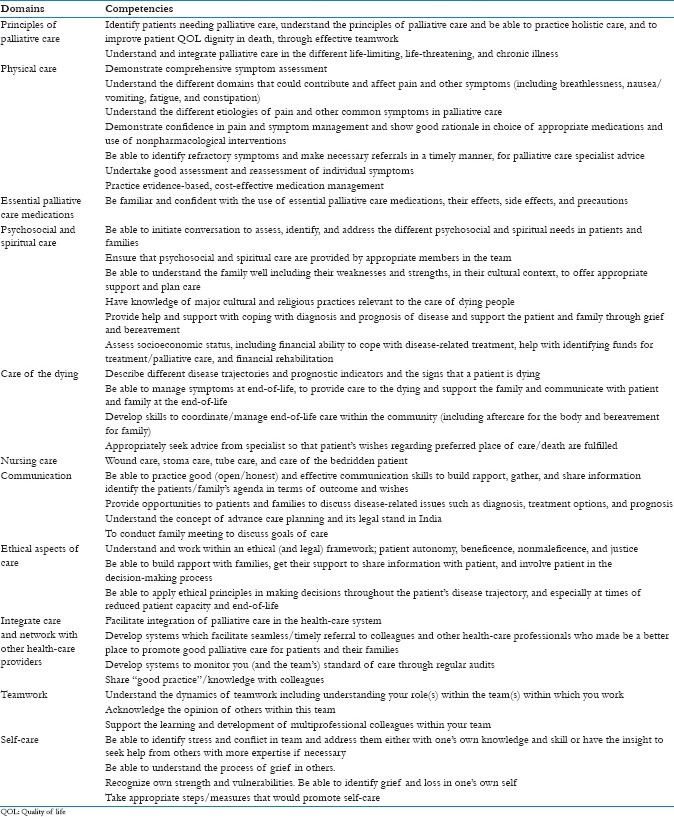

Competencies

Core competencies represent essential knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values that a clinician is expected to acquire to deliver good palliative care. They underpin quality practice and may require behavioral and value based change.[22] Competencies required by generalists in the community to care for patients with life-limiting and chronic diseases should be set at the level of primary palliative care [Appendix 1]. Quill and Abernethy[23] refer to a generalist plus specialist palliative care model in the community as a sustainable model. The vast majority of palliative care should be provided by generalists from any discipline, with clear, timely, and accessible support from specialist palliative care. The skills necessary in generalist or primary palliative care include the following: basic symptom control management of pain and symptoms, anxiety and depression, and the ability to have basic appropriate advance care discussions including; prognosis, goals of treatment, suffering, and discussion on resuscitation and intensive care in the event of further deterioration.[23]

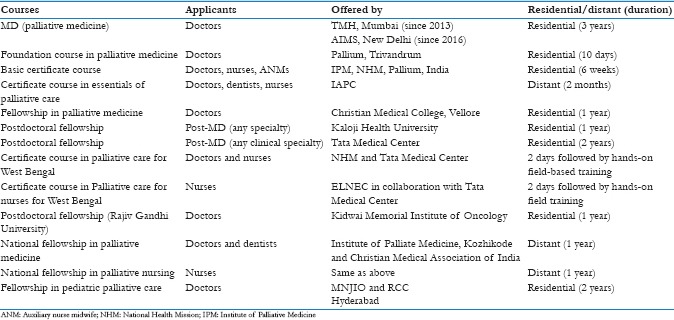

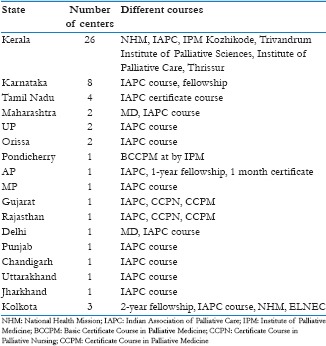

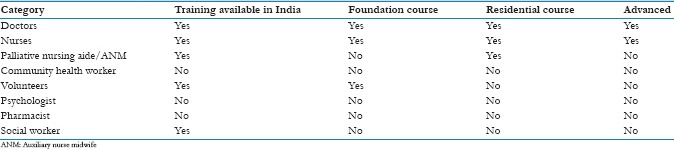

Palliative care education and training should be available and accessible to medical practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech and language pathology practitioners, social workers, chaplains, and spiritual workers; and all other disciplines who are involved in palliative care. It should be a part of the curriculum of all health-care professionals at undergraduate and postgraduate levels include members of the public, volunteers, and policymakers to advocate for early palliative care and to encourage the adoption of palliative care policies and practices in all the health-care facilities. The current opportunities for formal palliative care education in India remain sparse. Palliative medicine as a postgraduate specialty course was recognized by the MCI in the year 2011, but few MD seats are available at present. Details of the residential and distant learning courses available, for all categories of staff involved in palliative care service, in different parts of the country are provided in [Appendices 2–5. Core domains for palliative care have been delineated in several settings and include the following: (1) basics of palliative care, (2) psychosocial and spiritual, (3) ethical and legal, (4) communication skills, and (5) teamwork and professionalism.[24,25,26,27]

Delivery of education

In India, primary care is delivered by a wide variety of medical practitioners with differing types of training, which include AYUSH as well as allopathic. To have a set of recommendations on how best to teach palliative care in various clinical and educational settings one must focus on 5 topics;

Rationale for training

Core competencies for the appropriate level of practice and cadre

Content and modes of teaching

Portals to facilitate teaching

Positive outcomes and barriers.

Rationale for training

The basic core knowledge required to provide high-quality palliative care and excellent primary care overlap in many aspects:[28] relationship-centered care; communication skills; delivering comprehensive, integrated care for patient and family; attention to psychosocial–spiritual concerns and cultural diversity; emphasis on QOL and maximizing function; respect for the patient's values, goals, and priorities in managing illness; and providing care in the community in collaboration with other professionals (including specialists), thus reinforcing and strengthening each other's role.[29,30] Added emphasis on preparing primary care physicians for this role has the potential of enhancing the professional satisfaction and confidence among physicians.[31,32,33]

Proposal of Strategies for Palliative Care in India (expert group report) from Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, have given a plan to incorporate principles of long-term care and palliative care into the educational curricula, including action plan and topics needed to be covered.[34]

Content and modes of teaching

Case-based discussion, role play, standardized patient exercises, and practical sessions in communication skills such as breaking bad news and advance care planning and lectures should be used to expose learners to the range of palliative care issues. As part of rotations as undergraduate (MBBS) or postgraduate trainee in Family Medicine, each student should participate in collaborative, longitudinal palliative care setting or hospice experiences, including interdisciplinary team meetings, patient home visits, and telephone contact with patients, families, and caregiver nurses. Assessment methods should be summative and formative and include ways to assess clinical competency as well as knowledge. This can include modified objective structured clinical examinations designed to assess communication, clinical skills, decision-making, clinical reasoning, and ethical problem solving around the end-of-life issues.

Portals to deliver the teaching

Family physicians at any and every stage of their career should have the opportunity to avail formal palliative care education, as well as self-directed learning. Recipients should include all general physicians including mid-career clinicians and training should be conducted periodically.

MCI – Incorporating modules of palliative care training into existing undergraduate training programs will be needed. An oversight body with responsibility for reviewing palliative care content across the entire curriculum would facilitate appropriate inclusion of this material in preclinical education and clinical teaching sites. “Modules on palliative care” has been submitted to MCI for consideration to be included in UG medical education curriculum, in 2013 by the WHO Collaborating Centre for community participation in palliative care and long-term care. In Vision 2015, in Strategies For Large-scale Faculty Development for India, MCI, has recognized that palliative care has a major role to play[35]

Indian Medical Association (IMA) – Most Indian doctors are members of this organization which has branches and chapters across the country. It organizes periodic Continuing Medical Educations (CME's) and workshops, in which palliative care should be included. As a part of the advocacy for community-based palliative care, the IAPC and Academy of Family Physicians of India (AFPI) will approach the IMA to start a short certificate course in palliative care by college of physicians run by IMA

E-learning – Many organizations such as Cousera run free online courses on a wide variety of subjects. These courses do not offer formal certification but are very popular because of high quality and ease of access. Some paid courses include contact sessions and offer formal diplomas. These types of courses targeted to family practitioners over 6–8 weeks would be very attractive to busy practitioners[36]

Blended learning – Distance education is one of the very important methods of training health professionals. Christian Medical College, Vellore, one of the largest teaching hospitals in India, has been offering a blended education family medicine training program, of 2-year duration, since 2003, and has incorporated palliative care modules. This program uses textbooks as teaching modules and has practical aspects of consultation, counseling, and pain management using patient clinical scenarios during contact programs. These contact sessions have introduced the concept of palliative care to many general practitioners in various parts of the country and have encouraged them to incorporate it into their practice. More recently, a blended learning Masters in Family Medicine linked with the University of Edinburgh has been delivered at CMC Vellore

National Board of Examinations (NBE) – The syllabus for postgraduate course in family medicine includes palliative care. However, adequate training probably does not occur due to lack of trainers and training sites. IAPC should offer to train selected faculty who are running Family Medicine courses throughout the country. The IAPC will work with the NBE to suggest how palliative knowledge, skills, and attitudes can be adequately included in the assessment (formative and summative) on a regular basis. This will drive greater emphasis on the subject

AFPI – Major primary care organization for the development of education in primary care has the opportunity to assume leadership roles in improving education in palliative care. Primary care CME programs done by AFPI must include palliative care as core content.

In view of the immediate need of human resource, linking up with existing training workshops, certifications, and fellowships will be helpful. Distance education is one of the very important methods of training health professionals.

Barriers and opportunities

An awareness of the barriers and incentives can help to foster integration of palliative care educational content across the educational spectrum.

Barriers

As palliative medicine is an emerging discipline, the lack of institutional palliative care programs or linkages with community hospice programs are likely to hinder the development of educational opportunities for students in primary care

Lack of a vision of excellence in chronic disease management and end-of-life care may limit aspirations and expectations of both students and faculty, resulting in acceptance of suboptimal care processes and outcomes

Lack of adequately trained faculty to promote and implement this vision and these new educational offerings and increasing the availability of continuing education.[37]

Opportunities

The confluence of primary care and palliative care education improves both through integrated teaching

Improvements in palliative care education will have benefits for dying patients and their families, including many other primary care patients, for example, geriatric patients and those with chronic illnesses.

Service Development for Community Palliative Care

Preamble: Distribution of palliative care services in the country

Lack of awareness about palliative care and poor availability and accessibility to existing services result in vast suffering and poor QOL and death.[9] Successfully piloted and established community-based palliative care models allow care to be undertaken in patient's homes. This will ensure that holistic care is practiced taking social, cultural, and economic background into consideration. Widening the home-based care network with trained multidisciplinary teams can enhance palliative care delivery.

Examples of existing home care models in the country

The “Neighborhood Network in Palliative Care,” a WHO demonstration project, was developed in Kerala to empower local communities to supplement the work of home-based palliative care health providers. This is a collaborative program between the government and nongovernmental organization (NGO) sector.[38] Volunteers work in close collaboration with medical professionals in providing essential emotional and spiritual support, nursing care, nutritional support, and empowering family caregivers. The model has made palliative care a people's movement, thus transferring responsibility and ownership to the community. This serves as an alternative to the present expensive overmedicalized and specialized institutional care of the dying. Replicating this model in the country remains a challenge due to dependency on committed community volunteers and outlining their level of involvement.

A community-based palliative care program for rural/tribal population was initiated in the state of Maharashtra as a collaborative project between National Health Mission and Tata Memorial Center, Mumbai. The program aimed at utilizing the existing health system to provide palliative care. Community volunteers like the Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) were trained to identify patients with palliative care needs. She is an important link between the community and physicians in Primary Health Centers (PHCs). The ASHAs and auxiliary nurse midwives provided regular follow-up, notified physicians, and organized for patient transport to PHC. The major challenge is that the physicians in the PHCs are inundated with many government-run programs that take precedence over palliative care. Much time is spent in preparing reports for different programs, leaving little time for palliative patient care and counseling.

Lesson to be learned from Hospice Africa Uganda

Uganda has achieved much in palliative care in a low-income setting and is making progress advanced in integrating palliative care into the health-care system. Hospice Africa Uganda was started as a pilot project in 1993. A purely nurse-led home care model was started, oral liquid morphine was formulated locally, and medical professionals were trained in palliative care. Nurses underwent 9-month training in palliative care and the government provided legislation for them to prescribe morphine in the community.[39] In the past 10 years, family medicine has emerged as a separate postgraduate discipline with agreed integrated competencies for palliative care in Makerere University and all postgraduates complete 4 weeks clinical rotation in specialist palliative care.

Model of care

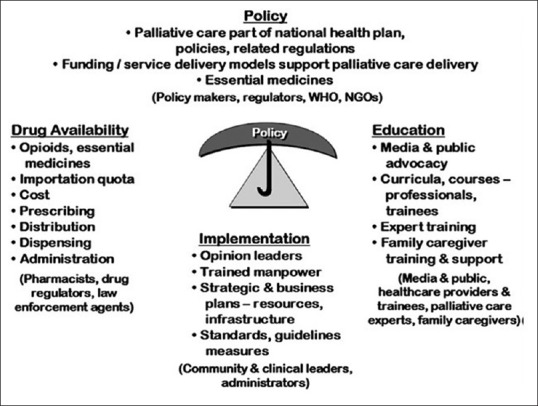

Considering our large population and disparate distribution of health services and health system hierarchy between rural and urban areas, it is difficult to develop a unified model of care across the country. Integration of services into existing health systems seems to be the only feasible solution as it will ensure both accessibility and sustainability of services. Thus, a model of care that empowers health-care personnel from the community up to tertiary center will be a practical solution to the present problem [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Algorithm depicting patient flow

Learning from other community models, an “integrated model of care” with ongoing care provided by primary care physicians with expert inputs from specialist palliative care physicians seems a feasible approach.[29] Primary palliative care in the community can be provided by general practitioners, family physicians, and public health physicians in the outpatient clinics or through domiciliary care after obtaining mandatory training in basic palliative care. The physician provides the first aid for emergencies and refers the patients to the specialist palliative care physician for more complex cases or cases demanding inpatient care. The specialist palliative care physician will provide care for more complex physical and psychological symptoms and admits patients who need inpatient care. The physician will also provide medical advice and education support to primary care physicians and volunteers in the community. In addition, the specialist will be responsible for providing managerial input on the running of the program on a timely basis and amend the program as appropriate.

Essential Palliative Care Medicines Availability

The WHO defines essential medicines as, “that satisfy the priority health care needs of the population; they should therefore be available at all times in adequate amounts and in appropriate dosage forms, at a price the community can afford.”[7] The essential medicines list needs to be country specific addressing the disease burden of the nation. The WHO Model List of essential medicine for both adults and children,[40] serves as a guide for the development of essential medicine lists. In the year 2013, the WHO created a new separate section “Medicines for Care and Palliative care.” The new section included a list of medications used in palliative care to treat the most common symptoms based on the recommendation given by experts and organizations like IAHPC.[41]

People with illness highly value the avoidance of pain and suffering, yet most health-investment decisions, both public and private, focus on extending life and increasing productivity. This obsession with extension of life and treatment of disease has displaced adequate attention to human dignity and QOL. The dying patients are ignored and excluded from most health-care planning. Stringent regulations on opioid medications like oral morphine for analgesia, scarcity of trained health professionals in palliative care are critical factors that affect palliative care reaching the needy.[42]

The cost of caring for patients with serious, complex, or life-limiting health problems is often borne out-of-pocket by most patients and their families. This put them at serious financial risk and risk of exhaustion and health problems of their own. Data on low cost, cost-effectiveness, and cost-savings impacts of palliative care need to be communicated with government and decision-making bodies. Universal health coverage must include access to pain control and palliative care with financial protection as a fundamental goal. However, most essential packages typically do not include drugs and other interventions to alleviate pain and suffering.[43] India has a National List of Essential Medicine (NLEM)[44] and each state their own list of essential medicines. The section on “Analgesics, Antipyretics, Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Medicines, Medicines used to Treat Gout and Disease-Modifying Agents used in Rheumatoid Disorders” of NLEM mentions oral morphine.

Way forward

Community-based palliative care programs where care continues to reach the patient at the doorstep and is recognized as an essential part of the UHC needs to be implemented across the country. This can only be implemented by concerted efforts between specialist palliative care physicians, general physicians, and family physicians with the aid of support teams like the community nurses, social workers, and community volunteers. To ensure that palliative care reaches the distant villages and tribal population, palliative care must be integrated into the existing health system. The integration must be all-encompassing including patients, family, and community volunteers such as community-based volunteers.

The first step toward developing a community program in palliative care includes training and empowering physicians and nurses in the community on the principles of palliative care. There are multiple courses ranging from basic palliative care to more specialized training in palliative care conducted throughout the year across the country. To ensure standardized care across the country, the training program must be unified under the umbrella of IAPC and the AFPI. Training must be initiated in the MBBS and nursing curriculum as this will ensure that every doctor and nurse imbibe the principles of palliative care right at the inception of their career, and the training must continue into the postgraduate curriculum as well. Initiating palliative care and sustaining the efforts is resource intensive. This demands strong leadership and continued political will to support the endeavor. There is thus a need for multiple stakeholders including community leaders, government, NGOs, CBOs, media to be actively involved in advocating for the cause, and generating public awareness. Every individual in the community must be sensitized to the needs of patients with palliative care needs and empowered into supporting the cause.

Although some of the barriers inaccessibility to palliative care have been overcome, there still exist challenges in large parts of the country, especially in the rural and tribal areas. There are larger reforms needed in the health-related policies in the country. The specialist palliative care physicians must harmoniously work with generalists in the community, thus ensuring continuity of care.

And finally, as Mark Twain put forth, “Do the right thing. It will gratify some people and astonish the others.”

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Appendix 1: Core competencies for generalists to provide primary palliative care

Appendix 2: Palliative care courses available in India

Appendix 3: Palliative care training centers in various states

Appendix 4: Training opportunities for different categories of staff in India

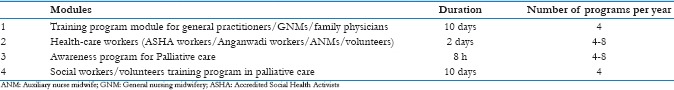

Appendix 5: Training modules - duration/frequency of programs

References

- 1.Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR). General Comment 14, para 25. [Last accessed on 2017 Nov 04]. Available from: http://www.refworld.org/pdfid/4538838d0.pdf .

- 2. [Last accessed on 2018 Jan 08]. Available from: https://www.nhp.gov.in/NHPfiles/national_health_policy_2017.pdf .

- 3. [Last accessed on 2017 Nov 04]. Available from: http://www.apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA67/A67_R19.en.pdf .

- 4.Stjernswärd J, Foley KM, Ferris FD. The public health strategy for palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:486–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Lima L, Bennett MI, Murray SA, Hudson P, Doyle D, Bruera E, et al. International association for hospice and palliative care (IAHPC) list of essential practices in palliative care. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2012;26:118–22. doi: 10.3109/15360288.2012.680010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knaul FM, Farmer PE, Krakauer EL, De Lima L, Bhadelia A, Jiang Kwete X, et al. Alleviating the access abyss in palliative care and pain relief-an imperative of universal health coverage: The lancet commission report. Lancet. 2018;391:1391–454. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32513-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. [Last accessed on 2018 Mar 30]. Available from: http://www.who.int/medicines/services/essmedicines_def/en/

- 8.WHO. Definition of Palliative Care. [Last accessed on 2018 Jan 08]. Available from: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/

- 9.Khanna I, Lal A. Palliative care – An Indian perspective. ARC J Public Health Community Med. 2016;1:27–34. [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Economist Intelligence Unit. The 2015 Quality of Death Index: Ranking Palliative Care Across the World. [Last accessed on 2017 Nov 05]. Available from: https://www.eiuperspectives.economist.com/sites/default/files/2015%20EIU%20Quality%20of%20Death%20Index%20Oct%2029%20FINAL.pdf .

- 11.Myatra SN, Salins N, Iyer S, Macaden SC, Divatia JV, Muckaden M, et al. End-of-life care policy: An integrated care plan for the dying: A joint position statement of the Indian society of critical care medicine (ISCCM) and the Indian association of palliative care (IAPC) Indian J Crit Care Med. 2014;18:615–35. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.140155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelley AS, Morrison RS. Palliative care for the seriously ill. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:747–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1404684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Temel JS, Greer JA, El-Jawahri A, Pirl WF, Park ER, Jackson VA, et al. Effects of early integrated palliative care in patients with lung and GI cancer: A randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:834–41. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.5046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salins N, Ramanjulu R, Patra L, Deodhar J, Muckaden MA. Integration of early specialist palliative care in cancer care and patient related outcomes: A critical review of evidence. Indian J Palliat Care. 2016;22:252–7. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.185028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z, Lyons KD, Hull JG, Li Z, et al. Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: Patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1438–45. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.6362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray SA, Boyd K, Sheikh A, Thomas K, Higginson IJ. Developing primary palliative care. BMJ. 2004;329:1056–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7474.1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell GK. How well do general practitioners deliver palliative care? A systematic review. Palliat Med. 2002;16:457–64. doi: 10.1191/0269216302pm573oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramanayake RP, Dilanka GV, Premasiri LW. Palliative care; role of family physicians. J Family Med Prim Care. 2016;5:234–7. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.192356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alt-Epping B, Lohse C, Viebahn C, Steinbüchel NV, Benze G, Nauck F, et al. On death and dying – An exploratory and evaluative study of a reflective, interdisciplinary course element in undergraduate anatomy teaching. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:15. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-14-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brennan F. Palliative care as an international human right. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:494–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larkin P. Critical complexity – Guidelines for clinical competencies in palliative nursing: A global perspective. Report from the International Working Group on Palliative Nursing Education. Rome. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care – Creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1173–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1215620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.APCA. Core Competencies: A Framework of Core Competencies for Palliative Care Providers in Africa. Uganda: APCA; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snell K, Leng M, Downing J, Barnard A, Murray S, Grant L. The Palliative Care Curriculum Toolkit. Practical Guide to Integrating Palliative Care into Health Professional Education. [Last accessed on 2018 Mar 26]. Available from: https://www.ed.ac.uk/files/atoms/files/curriculum_toolkit_-_ks_final_07_10_15_2_final.pdf .

- 26.Association for Palliative Care (EAPC). Recommendations of the EAPC for the Development of Undergraduate Curricula in Palliative Medicine at European Medical Schools. EAPC; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palliative Care Australia. Standards for Providing Quality Care for all Australians. Deakin West Australia: PCA; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Block SD, Bernier GM, Crawley LM, Farber S, Kuhl D, Nelson W, et al. Incorporating palliative care into primary care education. National consensus conference on medical education for care near the end of life. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:768–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00230.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marshall D, Howell D, Brazil K, Howard M, Taniguchi A. Enhancing family physician capacity to deliver quality palliative home care: An end-of-life, shared-care model. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:1703.e7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howard M, Chalifoux M, Tanuseputro P. Does primary care model effect healthcare at the end of life. A population-based retrospective cohort study? J Palliat Med. 2017;20:344–51. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2016.0283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.von Gunten CF, Von Roenn JH, Johnson-Neely K, Martinez J, Weitzman S. Hospice and palliative care: Attitudes and practices of the physician faculty of an academic hospital. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 1995;12:38–42. doi: 10.1177/104990919501200413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steinmetz D, Walsh M, Gabel LL, Williams PT. Family physicians’ involvement with dying patients and their families. Attitudes, difficulties, and strategies. Arch Fam Med. 1993;2:753–60. doi: 10.1001/archfami.2.7.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schneiderman LJ. The family physician and end-of-life care. J Fam Pract. 1997;45:259–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Directorate General of Health Services. Proposal of Strategies for Palliative Care in India (Expert Group Report). Ministry of Health & Family Welfare; 6 November. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 35. [Last accessed on 2017 Jul 24]. Available from: http://www.niti.gov.in/writereaddata/files/mci1.pdf .

- 36. [Last accessed on 2017 Jul 24]. Available from: http://www.ecancer.org/education/course/16-palliative-care-e-learning-course-for-healthcareprofessionals-in-india.php .

- 37.Mahtani R, Kurahashi AM, Buchman S, Webster F, Husain A, Goldman R, et al. Are family medicine residents adequately trained to deliver palliative care? Can Fam Physician. 2015;61:e577–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rajagopal MR, Kumar S. A model for delivery of palliative care in India – The Calicut experiment. J Palliat Care. 1999;15:44–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Downing J, Batuli M, Kivumbi G, Kabahweza J, Grant L, Murray SA, et al. A palliative care link nurse programme in Mulago hospital, Uganda: An evaluation using mixed methods. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15:40. doi: 10.1186/s12904-016-0115-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. [Last accessed on 2017 Jul 24]. Available from: http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/en/index.html .

- 41. [Last accessed on 2017 Jul 24]. Available from: https://www.hospicecare.com/about-iahpc/projects/palliative-care-essentials/iahpc-essential-medicines-for-palliative-care/

- 42.Knaul FM, Farmer PE, Bhadelia A, Berman P, Horton R. Closing the divide: The Harvard global equity initiative-lancet commission on global access to pain control and palliative care. Lancet. 2015;386:722–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60289-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ratcliff C, Thyle A, Duomai S, Manak M. Poverty reduction in India through palliative care: A pilot project. Indian J Palliat Care. 2017;23:41–5. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.197943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. [Last accessed on 2017 Jul 24]. Available from: http://www.cdsco.nic.in/WriteReadData/NLEM-2015/Recommendations.pdf .