Abstract

Introduction:

Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) is one of the most prevalent disorders at reproductive age and has a negative impact on emotions and performance of women. Since various factors play a role in the development of this syndrome, the present study was aimed to examine biopsychosocial etiology of PMS in the form of a narrative review.

Materials and Methods:

Relevant studies were collected based on the three subjects of biological, psychological, and social etiologies during 1987–2015. First, Medical Subject Headings was used to specify the relevant keywords such as biological, psychological, social, and premenstrual syndrome which were used to search Internet databases including Google Scholar, Scopus, PubMed, PMDR, Ovid, Magiran, and Iranmedex, which led to collection of 1 book and 26 Persian and English articles.

Results:

The results were classified into three sections. In the biological section, the effect and role of sex hormones and their changes in PMS were examined. In the psychological section, hypotheses on PMS and the role of psychological problems in the development of PMS were examined. In the social section, the role and social, religious, and cultural position of women and its relationship with PMS were examined.

Conclusion:

To reduce negative experiences of PMS, it is recommended that girls should be provided with necessary scientific information on puberty and premenstrual health. The results showed that paying attention to the complaint on premenstrual symptoms is significant in women's comprehensive assessment, and it plays an essential role in diagnosing psychological and physical annoying diseases.

Keywords: Biopsychosocial, etiology, premenstrual syndrome

Introduction

Nowadays, women's health is taken into account as one of their obvious rights and one of the main goals of social and economic development of societies; therefore, paying attention to problems and diseases that threaten women's physical and mental health, such as premenstrual syndrome (PMS), is among health priorities. PMS, which refers to periodic recurrence of a combination of physical, psychological, and behavioral changes in the luteal phase of menstrual cycle, is one of the prevalent problems among women.[1] Reviewing the background of PMS shows that this disorder was even known in ancient times. Hippocrates was the first one that proposed behavioral changes associated with the menstrual cycle. He believed that headaches and heaviness before menstruation is an anxious blood that is looking for a way to exit.[2] However, PMS was first proposed as a broad diagnostic concept as recurrent symptoms during the premenstrual or menstrual 1st days in 1953 by Green and Dalton, and these symptoms completely disappear after menstruation. Later in 1987, this syndrome was described as late luteal phase dysphoric disorder by the American Psychiatric Association, and after other symptoms such as being out of control was added in 1992, it was referred to as premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD).[3] Many researchers consider PMS as one of the most prevalent psychosomatic disorders which remarkably disrupts women's lives.[4] PMS which involves changes and disruption in women's mood or emotional states is highly significant because mood states play an essential role in determining lifestyle.[5] Most women experience discomfort before menstruation. Women with PMS choose not to go to work more than ever, sometimes they get injured and need to be hospitalized in a hospital, they experience mental discomfort, and they may even attempt to commit suicide. If they have to participate in an exam or job interview during these days, the score obtained by them will drop by 13% on average.[5]

This syndrome affects all age groups; however, the most common age group is 25–45 years, and the time of referral for its treatment is the middle or late third decade of life. Moreover, it seems that an increase in age plays an important role in an increase in symptoms.[4] The frequency of this syndrome in Europe has been reported to be 41%, in Africa 83%, in Asia 46%, and in South America 61%. The overall prevalence of PMS is 48% (confidence interval 95%: 33–68). Different studies have reported the different prevalence rate of PMS in different countries, such that it was reported as 98% in Iran and 10% in Switzerland.[6]

Some believe that patients with this syndrome account for 50% of clients to gynecological clinics. PMS is basically a psychosocial problem which is biologically, psychology, or sociologically tied with menstrual cycle.[7] The cause of PMS has remained unknown, and the research results refer to multiplicity of its causes.[5] Genetic factors, familial inheritance, the role of and changes in sex hormones, neurotransmitters and central nervous system, environmental factors, depression, migraine, and lack of social and emotional support can affect the development and intensity of the symptoms.[8] According to what was said above, it is highly necessary to examine biological, psychological, and social etiologies of PMS, and discussion of more intellectual and diverse approaches is needed.[9] The present study was a narrative review of biopsychosocial etiology of PMS.

Materials and Methods

In preparation and completion stages of the present review, relevant studies carried out based on three methods of biological, psychological, and social etiologies during 1987–2015 were taken into account. First, Medical Subject Headings were used to specify the relevant keywords such as biological, psychological, social, and premenstrual syndrome which were used to search Internet databases including Google Scholar, Scopus, PubMed, PMDR, Ovid, Magiran, and Iranmedex, and articles, reports, and publications of the World Health Organization. The main criterion for inclusion of the articles was documentation related to biology, psychology, and psychology of PMS, and those studies that focused on other aspects of PMS or were based on certain strategies in particular regions were crossed out from the study. Search for studies related to PMS related to collecting 49 articles and 1 book. In the first phase, the summary of the articles was examined using Abstract Screening Sheet, and 7 irrelevant studies were excluded from the study. In the next phase, Full-Text Screening Sheet was used to examine all of the articles from the previous phase. Finally, 26 articles and 1 book were listed, out of which 3 articles were in Persian, 23 in English, and a book and the required data were extracted from them.

Results

The results were classified into biological, psychological, and social factors.

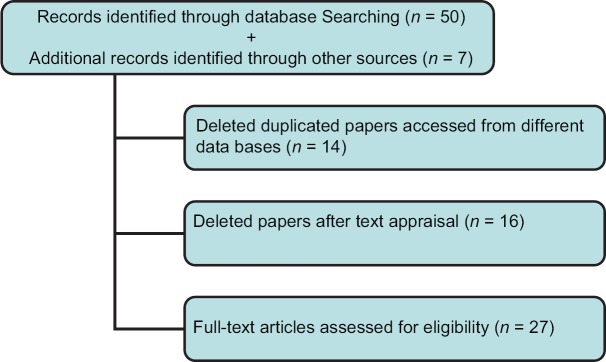

After searching for keywords and applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria’ 27 qualified articles were selected [Figure 1 and Table 1].

Figure 1.

Papers search and review flowchart

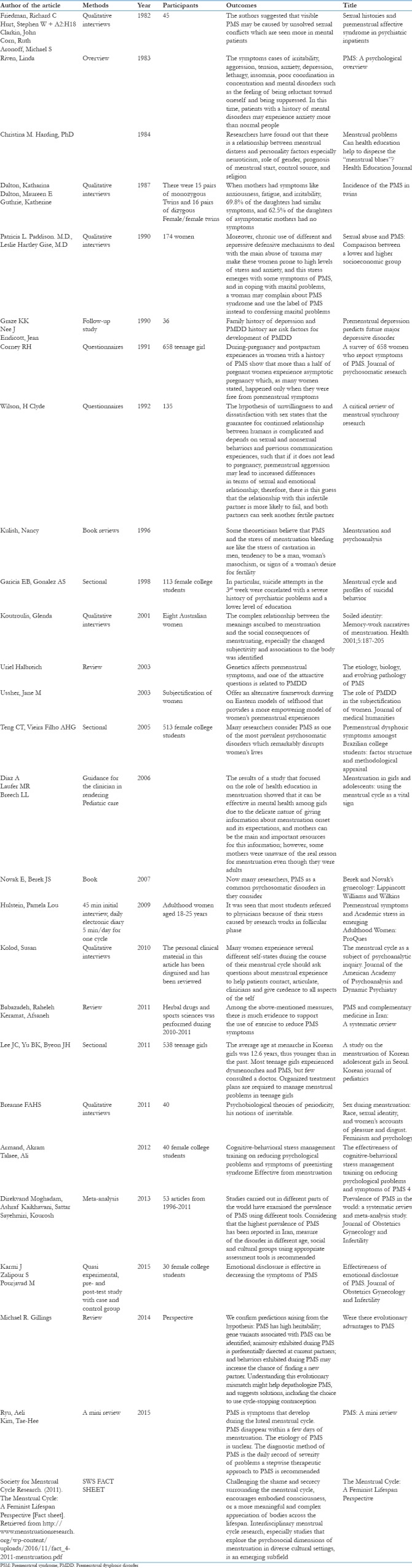

Table 1.

Description of the studies included in the A narrative review

Biological factors

Biological difference between women and men is the importance of menstrual cycle.

The role of hormones and premenstrual syndrome

An increase in the level of gonadal hormones and their fluctuations may not be the only cause of PMS but might intensify the results of the symptoms in hormone-sensitive individuals. Reports by patients with PMS who experienced a remarkable decrease in symptoms after administration of gonadotropin-releasing hormones, i.e., leuprolide, support the hypothesis of high sensitivity, and reaction to hormones. In addition, using estrogen or progesterone leads to recurrence of the symptoms. Researchers have indicated that PMS is characterized by abnormal response of hormonal receptors to normal levels of gonadal steroids.[8]

There were similar reports on the onset of symptoms in postmenopausal women such as intense bad temper, tension, and other symptoms after acute exacerbations and changes in the level of their gonadal hormones during consumption of the onset of taking high doses of estradiol in the beginning of hormone replacement therapy. These complications subside through continuous and stable administration of estrogen; moreover, a similar effect was observed after administration of progesterone.[8]

Estrogen affects large and complex neurotransmitters such as serotonin, noradrenaline, gamma butyric acid, dopamine, and acetylcholine which regulate mood, behavior, and cognitive function. Moreover, it plays a strong role in nervous irritability. Therefore, luteal phase proliferation and decrease in estrogen level play a role in the development of PMS symptoms. However, this simple hypothesis that an increase and decrease in estrogen during follicular phase changes over a period and is almost asymptotic indicates that other additional factors contribute to the development of PMS symptoms.[8]

Hormonal fluctuations in estrogen and progesterone, neuroendocrine disorders, diversity of estrogen receptors, and prostaglandin synthesis play a role in biological etiology of PMS.[10]

The role of genetics and premenstrual syndrome

Genetics affects premenstrual symptoms, and one of the attractive questions is related to PMDD. Feminine lifecycle is similar in most women, but only a group of women are restless during their menstruation or in response to such events. The probability of development or vulnerability to depression in these women is one of the rapid explanations.[8]

Heritance of premenstrual symptoms is now well accepted and plays an important role in expression of PMS symptoms. In 1971, it was indicated that there was a strong correlation between mothers and their daughters in terms of premenstrual tension, and they had numerous similarities in the subgroup of PMS symptoms. When mothers had symptoms such as anxiousness, fatigue, and irritability, 69.8% of the daughters had similar symptoms, and 62.5% of the daughters of asymptomatic mothers had no symptoms.[11]

These symptoms may be one of the main reasons for paying attention to PMDD as a different clinical entity or distinction of a subgroup of women. Women with PMSS disorder and those with seasonal mood disorder have a lot in common, and light therapy has been proved to have positive effects on both groups. Both disorders; however, are interpreted as related disorders of periodic and seasonal hormonal changes.[12] Family history of depression and PMDD history are risk factors for development of PMDD.[12]

The role of body metabolites and premenstrual syndrome

The assumption of deviation and changes in body metabolites shows that in premenstrual period, glucose-induced by metabolism of food deviates from the brain to the reproductive system and its surroundings including an increase in the level of blood in uterus vessels, which provides menstruation. Afterward, this deviation leads to changes in brain control adjustment processes, which in turn causes impulsive symptoms which is the characteristic of PMS. This hypothesis; however, has contradictions with observations that state obesity increases the risk of PMS development. For example, increased fat deposits compensate for lack of metabolism required by the body and simply enhances glucose consumption.[13] Since in premenstrual phase, it is characterized by a decrease in hormone in the bloodstream, no significant increase in function in the ovary and the uterus at the beginning and development of the next cycle, and there is no clear reason for increased metabolic costs which are different during the premenstrual phase.[13,14]

In a hypothesis, it is stated that the immune system is suppressed in the luteal phase, and as the immune system becomes weak, pathogens increase their activities, which in turn leads to development of PMS symptoms. In this phase, taking antibiotics helps with general improvement of women with PMS.[13]

Psychological factors

In France, PMS is formally known as the transient cause of mental illness.

Premenstrual behavior is referred to as temporary insanity or incompetence of a woman. There is little evidence that confirms this, and there is no laboratory test or measure that confirms a woman's incompetence and her temporary insanity.[15]

The symptoms include cases of irritability, aggression, tension, anxiety, depression, lethargy, insomnia, poor coordination in concentration, and mental disorders such as the feeling of being reluctant toward oneself and being suppressed. In this time, patients with a history of mental disorders may experience anxiety more than normal people.[15]

The hypothesis of increased enthusiasm and jealousy in men states that PMS is the woman's hostility toward her male partner late in the luteal phase, which is the result of losing opportunities for mating. It also postulates that PMS is the result of fertility failure during the current cycle; therefore, it leads to aggravation of lust and provocation of jealousy in man, which in turn improves the chance of fertilization in the next ovulation.[13,14] The hypothesis of pleasant feelings and cheerful mood during ovulation in women's cycle refers to improvement in the chances of fertility in women and states that in this phases, women experience more positive physical and behavioral states such as happiness, relaxation, and desire for sex. When these positive states stop during premenstrual phase and turn into irritable, depressed, anxious, and tired moods, they lead to experiencing less physical, mental, and intellectual happiness, and are characterized by PMS syndromes.[13]

The hypothesis of unwillingness to and dissatisfaction with sex states that the guarantee for continued relationship between humans is complicated and depends on sexual and nonsexual behaviors and previous communication experiences, such that if it does not lead to pregnancy, premenstrual aggression may lead to increased differences in terms of sexual and emotional relationship; therefore, there is this guess that the relationship with this infertile partner is more likely to fail, and both partners can seek another fertile partner.[13,14]

In the women's discussion and the official history of psychiatry and psychology, it can be seen that PMDD is a verbal achievement that has formed through private and public narratives and discourses of women and the experts that study the knowledge of the body. However, PMDD is a phenomenon that cannot verbally be defined in the discourse. This phenomenon is interconnected with a set of physical, mental, and social status and our relationship with ourselves, and affects the women's lives. Including PMDD in DSM provides the legitimacy of a set of facts. In interpreting PMDD or PMS experience, physicians and researchers formally use the title of pathology. They consider examination, diagnosis, and treatment as legitimate and legal, and people call women with this condition as afflicted, sick, unstable, or insane.[16]

Lupton agrees that favorable aspects of PMS such as desire for pregnancy are referred in menstrual psychology; however, they are rare. Some theoreticians believe that PMS and the stress of menstruation bleeding are like the stress of castration in men, tendency to be a man, woman's masochism, or signs of a woman's desire for fertility.[17]

During-pregnancy and postpartum experiences in women with a history of PMS show that more than a half of the pregnant women experience asymptotic pregnancy which, as many women stated, happened only when they were free from premenstrual symptoms. However, 50% of the women had an average feeling, and in postpartum period, a large number of them experienced depression which continued for more than 4 months in over half of them. While treating postpartum depression, the general practitioners and health personnel did not pay attention to before-pregnancy PMS.[18]

Researchers have found out that there is a relationship between menstrual distress and personality factors especially neuroticism, role of gender, prognosis of menstrual start, control source, and religion. The results of different studies; however, are incomplete and mostly contradictory. The results of a study showed that there is a correlation between anxiety and PMS stress. Moreover, there is a correlation between painful menstruation and an increase in menstruation time and depression and the role of femininity. There is a significant relationship between maternal role and decreased depression and PMS stress and bleeding time. It seems that women who are mothers experience shorter periods of menstruation.[19]

Experience of sex during menstruation in a group of women was challenging, and the women made a number of negative comments such as women's discomfort, physical pain, confusion, obvious discomfort of the partner, the feeling of not being clean, and other unpleasant feelings. They also had a number of positive ideas, for example, women who had more men's feelings referred to their positive feelings during their sex with their partner during their menstruation. In other words, women with more femininity power had negative feeling while those with masculine feeling experienced positive feelings.[20]

In the late 20th Century, many psychiatrists concluded that premenstrual fluctuations and changes as natural phenomenon. They also stated that some women experienced some issues which can be harmful if they are neglected, and they need psychological diagnosis.[16]

In the study carried out by Hulstein et al., the effect of stress caused by research works and PMS was extracted from electronic diaries of 50 students of Women's Health B. Sc. They indicated that scientific research stress affected the students in follicular phase, and there was a significant relationship between the number of days of the follicular phase and PMS symptoms of distress, i.e., with an increase in the length of follicular phase, PMS distress rises. There was also a significant relationship between luteal phase and academic stress such as presentations, papers, and projects. The results indicated that there are common components among PMS symptoms and academic stress. The results of the relationship between the symptoms of PMS stress and depression and academic stress provided a more obvious definition for this phenomenon.[21] It was seen that most students referred to physicians due to their stress caused by research works in follicular phase.[21]

Friedman et al. carried out a study in the US on 45 women who were hospitalized due to schizophrenia, depression, and borderline personality. They observed that 28 patients had probable or definite criteria for PMS. Out of them, 16 patients had the experience of abnormal sexual relationship (sexual abuse). On the contrary, only 1 out of 17 patients without PMS criteria did not have an abnormal sexual experience. Twelve out of 28 patients had depression and borderline personality disorder and PMS, 9 had both PMS with visible symptoms and abnormal sexual history. Six out of nine patients with sexual abuse experience had all effective PMS criteria. The authors suggested that visible PMS may be caused by unsolved sexual conflicts which are seen more in mental patients.[22]

Social factors

The results were collected from different and contradictory hypotheses on PMS and social and religious attitudes toward PMS. It seems that this contradiction was called a prevalent abnormality; and sometimes, it was claimed that it has hidden advantages such as the evolution of human from the past to now, likewise PMS is evolving.[13] It is utilized to justify the discrimination against women and girls in many cases. To understand the fundamental orders of human society better, shame, and secrecy about the menstrual cycle should be challenged, and it is necessary to encourage humans to become aware of and understand the complex meaning of the mood of the body throughout life.[23]

Culture affects the probability of development and prevalence of PMS. Attitude may play an important role in the emergence of signs and intensity of symptoms. However, religion is among other factors that are referred to as a predictor for the discomfort of menstruation onset. Wherever religion has a positive attitude toward menstruation, positive feelings, and less anxiety and stress are observed. A woman's religion can extremely affect her menstrual distress. For example, Jewish women who have many menstruation-related taboos suffer from a large amount of discomfort associated with menstruation. It seems that Protestants, who are heterogeneous religious groups, suffer less.[19]

There are different legends about menstruation, including touching a woman on menstruation is like the turning of wine to vinegar, burned crops, extremely dried seedlings, burning of an orchard, picking fruit from a tree, a blurred mirror, being deeply shaved, rusted iron, decayed moon, and dead honey bee. Moreover, in the history of the Middle Ages, premenstrual mental disorders in women were contributed to magic. Such descriptions of menstruation can double the adverse effects of PMS in women and intensify the unpleasant experience of PMS.[15]

The concept of menstruation and physical experience of menstruation can be influenced by social issues, and when physical changes are observed, they are related with our mentality and awareness of the body and change as the body turns into adulthood.

When a woman on menstruation is socially and religiously considered as a sexual, dirty, shameful, dangerous, and scary creature that is also unbalanced in terms of mood, mad and inconsistent in decision-making, she sees herself highly vulnerable in experiencing menstruation. When blood flows inside the body, it is clean and the sign of life, but once it exits the body, it is considered unclean, and the body gets dirty. The release of menstrual discharge is thought to be insanitary, and a woman who is not on her menstruation is regarded as sanitary and a healthy creature.[24]

Feminist activists have questioned the philosophy of menstruation and the current state of shame from menstruation, secrecy and silence, and attempted to directly and indirectly hold workshops through visual and artistic performances, celebrations, and sarcasm to provide information and produce and distribute small and big journals using websites, blogs, and other social media. They have also conducted studies that present menstrual cycle as a process of a healthy body. Some activists celebrate menstruation period as a link to the power source of women. Moreover, they have assigned the menstrual care industry as a global goal, and they are developing and paying attention to it. America's Vital Signs Campaign considers menstruation as a key index of the overall health of girls and women.[23] Some patients knowingly express their status in a complete way and talk about their lives and the issues that have caused them deep sorrow and the phases of menstruation distinctly, then they quickly deny such perceptions, “I was just PMS,” they are quite aware of their physical-mental status.[25] When an individual feels physically and mentally strong, she spends all event and ups and downs of her life well, but vulnerability in both physical and emotional aspects increases in PMS phase. Individuals who concealed their feelings while dealing with unpleasant thoughts were more physically and mentally sensitive, irritable, depressed, and vulnerable, but those who embraced such events and considered them as natural happenings learned that they needed more rest in such situations, and more care changed their feeling about them.[25] The results of a study that focused on the role of health education in menstruation showed that it can be effective in mental health among girls due to the delicate nature of giving information about menstruation onset and its expectations, and mothers can be the main and important resources for this information; however, some mothers were unaware of the real reason for menstruation even though they were adults. Most mothers have no information, and young patients and most mothers and fathers are unaware of the natural signs. Physicians may not also have sufficient information about menstrual patterns, natural period for menstruation, and the amount of bleeding in adolescents or they may choose not to ask their young patients about their menstrual cycle.[26]

In their study, Donna et al. interviewed 174 women with a complaint about PMS and reported the following results. About 33% of the women with high-socioeconomic position and 52% with low-socioeconomic position suffered from PMS; however, more women with high-socioeconomic position referred to private clinics and gynecologists. Moreover, there was a significant relationship between the rate of sexual abuse among women with high- and low-social position and PMS, and about 40% of the women complaining about PMS referred to their experience of sexual abuse. The author found a correlation between sexual abuse and hospitalization in the mental hospital among women who were after PMS treatment. The scores obtained from Beck Depression Inventory were high.[27]

Moreover, chronic use of different and repressive defensive mechanisms to deal with the main abuse of trauma may make these women prone to high levels of stress and anxiety, and this stress emerges with some symptoms of PMS, and in coping with marital problems, a woman may complain about PMS syndrome and use the label of PMS instead to confessing marital problems.[27]

Discussion

In their study, Gelling et al. stated that various PMS theories considered PMS as a result of women's hostility to nonpregnancy or hostility to a sexual partner, or an agent of suppressive immunity. Based on these hypotheses, PMS and PMSS are more frequent in modern populations, which is attributed to lack of compatibility between historical evolution and current cultural conditions, because in the modern culture, limited number of pregnancy and prevalence frequency of PMS and PMDD are more than before.

In the study of Koutroulis they concluded that social and religious theories refer to women during menstruation as unclean and women with PMS as insane. They also considered women as inferior due to having no control over the exit of fluids such as milk and menstrual blood. In their study, they stated that men also have involuntary withdrawal of fluid from their reproductive system, but why is masculine body the symbol of purity, normality, and power but women's body the symbol of impurity, abnormality, and vulnerability? Moreover, according to their viewpoint, there are two types of women; menstruating and not menstruating. In some places, involuntary exit of and lack of control over exit of fluids such as milk and menstrual blood is referred to as unclean; in some cases, both voluntary and involuntary exit of such fluids is called unclean; and in some cases, menstrual blood is introduced as hazardous due to its red color, high viscosity, pollution capability, and leaving spots.[24]

In the study conducted by Lee et al., the causes of PMS were referred to as hormonal changes in women's body, and the most hormonal changes occur in the last days of cycle,[10] which is in contrast with the study conducted by the study carried out by Gillings who stated that PMS symptoms decline during menstruation (minimum hormones); however, the reason was not explained. It was also stated that PMS symptoms occur all of the time except for ovulation time because maximum hormonal changes happen at that time.[13,14] Moreover, it was stated that “Why do not all women react to PMS symptoms and only a certain group reacts?”[13] This theory that hormonal changes affect these feelings is like a lightless light because it does not respond to these questions: Why are some women with PMS unable to do their daily tasks and their routines are disrupted? And while some women do not react at all, some other women think it is debilitating. All women have hormones, they why do only some of them suffer from PMS?[19]

According to the study carried out by Riven and diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders book, PMS is formally referred to as a mental and physical disorder.[15] In the late 20th Century, the results of the study of Ussher showed that psychiatrists referred to premenstrual changes as a normal phenomenon.[16] In positive structuralism, when we move forward beyond deconstructionism, an alternative framework is proposed to understand premenstrual signs from the Eastern models of mental health. Realities show that PMDD serves not only to regulate femininity but also to normal mood and personality.[16] In this framework, women are not encouraged to suppress their legitimate and legal feelings such as the certain feeling in PMS, and there is no criticism or management of PMS.[16]

PMS emerges when women are vulnerable and under pressure.[16] Here, the problem is not that women should get rid of their bad premenstrual feelings, but to change their understanding. Women learn to reduce their feelings or live with them or consider them as a part of themselves, and instead of fearing or hating them, they are helped to adapt to them. We also want to finish medicating PMS.[16]

In the study conducted by Kolod et al., who are Women's Rights Advocate and are challenging classic theories of DSM, it is pointed out that attentions are paid to hormonal experience and mood disorder is interpreted as a result of hormonal changes, in fact, negative attitude toward women and use of unstable mood titles are somewhat supported. Furthermore, the effect of body hormones on the psyche is vivid, which is an important issue related to psychoanalytic research. The method of understanding and knowledge of the patient and the psychoanalyst is different.[25] Women expressed different experiences of their menstrual cycle. Clinical experts need to ask the patients about their menstrual experience and PMS and pay attention to all individual aspects to use them for treatment. Why do not most physicians ask their patients about their menstruation date or experience? How do most doctors use the symptoms that emerge only during PMS days as evidence for mental disorders such as borderline personality and accuse the individual of having a borderline personality disorder.[25]

In such cases, girls are often willing to talk to their mothers; however, most mothers do not have enough information. Most physicians are unaware of abnormal patterns of bleeding which is caused by underlying medical issues with a prolonged potential. In examining 8-year-old girls or older, doctors should pay special attention to physical changes in puberty and the importance of training, following up, and supervising the menstrual cycle. They need to inform the parents about the normal state of their child's puberty and introduce menstrual cycle as a sign of feminine power, health, and a sensitive, essential, and powerful tool to evaluate the natural hormonal development. It is recommended that comprehensive instructions should be given to girls and women of reproductive age to help them deal with PMS appropriately and decline its symptoms. During PMS, girls with full awareness of their menstrual cycle experience less stress that those who are unaware of it.[19,26]

There are no new and various studies of biopsychosocial etiology of PMS and most of the conducted studies date back to before 2000. With a high prevalence of PMS in Iran, and by having sufficient knowledge and understanding of biopsychosocial etiologies, the stress and anxiety caused by PMS can be controlled through different techniques of relaxing exercise, proper nutrition, traditional medicine, or drug therapy, and women are given health and liveliness. If other mood disorders that overlap with PMS symptoms and intensify them, it is necessary to refer to psychiatric specialists.

Conclusion

According to the studies, it can be concluded that PMS disorder mostly exists in today's modern countries. According to the results of the present study and awareness of biological, psychological, and social etiology of PMS, PMS can be considered from a different point of view to reduce these negative experiences.

Young girls and their parents should be provided with necessary trainings including trainings of the first menstruation. It is equally significant to have a correct understanding of bleeding patterns in young girls and distinguish between normal and abnormal menstruations, and evaluate the conditions of young girls by their physician. Menstrual cycle should be considered as an important sign of life and a strong tool to evaluate women's health. Sexual health education and prevention of sexual abuse from children secure future children and women against many mood disorders including PMS. These results show that in comprehensive evaluation of the women, it is necessary to pay attention to their complaints about premenstrual signs, and paying attention to them plays an essential and pivotal role in diagnosing annoying mental and physical abnormalities, and it is possible that many causes of mood disorders are vividly revealed and appropriately managed.

Using the findings of the present study, discomfort, stress, anxiety, and unstable mood caused by PMS can be replaced by relaxing and enjoyable feelings.

It is suggested that when women with unspecified mood and physical symptoms refer to health-care providers or physicians, a complete history of their female reproduction needs to be taken, and children need to be provided with sufficient understandable information on normal and abnormal menstrual signs at the onset of their puberty.

Clinical application of the study

Women's fertility awareness (FA) and capacity lead to their supervision over the events of their menstrual cycle to determine fertility and infertility phases. Women with FA can prevent or obtain pregnancy and control and monitor phases of pregnancy and childbirth and their general health. There are numerous technical differences between women with and without FA in terms of concentration on primary signs of pregnancy and prevention of sexually transmitted diseases and immunodeficiency, and complete prevention of pregnancy.[23]

Body literacy is obtained by self-aware women who observe imagine the place of body organs, understand scientific signs of fertility and infertility, understand the events of their menstrual cycle, and take care of the health of other parts of their body. A woman's body literacy helps her understand how to connect her health with menstrual cycle, and thus she can make informed decisions about her health care. Resistance to body control through pharmaceutical companies is another advantage of body literacy.[23]

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ryu A, Kim TH. Premenstrual syndrome: A mini review. Maturitas. 2015;82:436–40. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babazadeh R, Keramat A. Premenstrual syndrome and complementary medicine in Iran: A systematic review. KAUMS J (FEYZ) 2011;15:174–87. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teng CT, Filho AH, Artes R, Gorenstein C, Andrade LH, Wang YP, et al. Premenstrual dysphoric symptoms amongst Brazilian college students: Factor structure and methodological appraisal. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;255:51–6. doi: 10.1007/s00406-004-0535-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armand A, Golden AS. The effectiveness of stress management training, cognitive-behavioral therapy on reducing psychological problems and symptoms of premenstrual syndrome. J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2012;15:24–31. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karami J, Zalipoor S, Pourjavad M. Efficacy of emotional disclosure on premenstrual syndrome. The Iranian J Obstetrics, Gynecology and Infertility. 2015;17:6–12. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Direkvand Moghadam A, Kaikhavani S, Sayehmiri K. Prevalence of premenstrual syndrome in the world: A met analysis and systematic review. Iran J Obstet Gynecology Infertile. 2013;16:8–17. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Novak E. Berek and Novak's gynecology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halbreich U. The etiology, biology, and evolving pathology of premenstrual syndromes. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2003;28(Suppl 3):55–99. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(03)00097-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baca-García E, Sánchez-González A, González Diaz-Corralero P, González García I, de Leon J. Menstrual cycle and profiles of suicidal behaviour. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1998;97:32–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb09959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JC, Yu BK, Byeon JH, Lee KH, Min JH, Park SH, et al. Astudy on the menstruation of Korean adolescent girls in Seoul. Korean J Pediatr. 2011;54:201–6. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2011.54.5.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalton K, Dalton ME, Guthrie K. Incidence of the premenstrual syndrome in twins. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1987;295:1027–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.295.6605.1027-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graze KK, Nee J, Endicott J. Premenstrual depression predicts future major depressive disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1990;81:201–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1990.tb06479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gillings MR. Were there evolutionary advantages to premenstrual syndrome? Evol Appl. 2014;7:897–904. doi: 10.1111/eva.12190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson HC. A critical review of menstrual synchrony research. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1992;17:565–91. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(92)90016-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riven L. Premenstrual syndrome: A psychological overview. Can Fam Physician. 1983;29:1919–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ussher JM. The role of premenstrual dysphoric disorder in the subjectification of women. J Med Humanit. 2003;24:131–46. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kulish N. Menstruation and psychoanalysis. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 1996;44:1286–90. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corney RH, Stanton R. A survey of 658 women who report symptoms of premenstrual syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 1991;35:471–82. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(91)90042-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harding CM. Can health education help to disperse the ‘menstrual blues’? Health Educ J. 1984;43:62–6. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fahs B. Sex during menstruation: Race, sexual identity, and women's accounts of pleasure and disgust. Fem Psychol. 2011;21:155–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hulstein PL. Premenstrual Symptoms and Academic Stress in Emerging Adulthood Women. ProQuest. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedman RC, Hurt SW, Clarkin J, Corn R, Aronoff MS. Sexual histories and premenstrual affective syndrome in psychiatric inpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139:1484–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.11.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Society for Menstrual Cycle Research. The Menstrual Cycle: A Feminist Lifespan Perspective [Fact sheet] 2011. Retrieved from: http://www.menstruationresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/fact_4-2011-menstruation.pdf .

- 24.Koutroulis G. Soiled identity: Memory-work narratives of menstruation. Health. 2001;5:187–205. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kolod S. The menstrual cycle as a subject of psychoanalytic inquiry. J Am Acad Psychoanal Dyn Psychiatry. 2010;38:77–98. doi: 10.1521/jaap.2010.38.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescence, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Adolescent Health Care. Diaz A, Laufer MR, Breech LL. Menstruation in girls and adolescents: Using the menstrual cycle as a vital sign. Pediatrics. 2006;118:2245–50. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paddison PL, Gise LH, Lebovits A, Strain JJ, Cirasole DM, Levine JP, et al. Sexual abuse and premenstrual syndrome: Comparison between a lower and higher socioeconomic group. Psychosomatics. 1990;31:265–72. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(90)72162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]