Titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs) are inorganic materials with a diameter of 1–100 nm.

Titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs) are inorganic materials with a diameter of 1–100 nm.

Abstract

Titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs) are inorganic materials with a diameter of 1–100 nm. In recent years, TiO2 NPs have been used in a wide range of products, including food, toothpaste, cosmetics, medicine, paints and printing materials, due to their unique properties (high stability, anti-corrosion, and efficient photocatalysis). Following exposure via various routes including inhalation, injection, dermal deposition and gastrointestinal tract absorption, NPs can be found in various organs in the body potentially inducing toxic effects. Thus more attention to the safety of TiO2 NPs is necessary. Therefore, the present review aims to provide a comprehensive evaluation of the toxic effects induced by TiO2 NPs in the lung, liver, stomach, intestine, kidney, spleen, brain, hippocampus, heart, blood vessels, ovary and testis of mice and rats in in vivo experiments, and evaluate their potential toxic mechanisms. The findings will provide an important reference for human risk evaluation and management following TiO2 NP exposure.

1. Introduction

Nanomaterials (NMs) are composed of nanoparticles, which are also known as ultrafine particles. NMs have special physicochemical properties depending on their particle size, chemical composition (purity, crystalline phase, charge), surface structure, solubility, aggregation and shape.1 With the development of nanotechnology, NMs have been manufactured in large quantities worldwide and used in a wide range of products such as sunscreen, catalysts, food, cosmetics and drug carriers due to their small size effect, surface effect, quantum size effect and macroscopic quantum tunneling effect.

Titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs) are one of the most widely used NMs. Anatase and rutile are the most common crystalline forms. TiO2 NPs are widely used in various industries such as paints, printing, food, toothpaste, medicine and cosmetics due to their high stability, anti-corrosion, and efficient photocatalysis.2–5 Therefore, contact with TiO2 NPs in our daily life is inevitable. The small size effect of TiO2 NPs makes them different from bulk TiO2 materials. They can reach various parts of the body via exposure routes including inhalation, injection, dermal deposition and gastrointestinal tract (GIT) absorption. Accordingly, the toxicity of TiO2 NPs has been increasingly questioned.6

After entering the body, NPs are probably transported to different systems by systemic circulation, and deposition in organs or tissues, thus inducing possible toxicity. TiO2 NPs ranging in size from 5–100 nm can be transported to the rat lung and then lymphatic drainage and blood vessels. When NPs are relocated into the blood circulation, they may systemically enter the cardiovascular, central-nervous and immune systems, resulting in potential toxicity if they are not eliminated from the body.7 Our research group investigated the distribution and toxicity of anatase-TiO2 NPs (5 nm) after intraperitoneal injection into mice for 14 days.8 The results showed that the coefficients of the liver, kidney and spleen increased, while the coefficients of the lung and brain decreased, and the coefficient of the heart showed little change. The order of NP accumulation in the organs was liver > kidneys > spleen > lung > brain > heart. NPs caused damage to the liver, kidney, and myocardium, and impaired the blood sugar and lipid balance in mice.

TiO2 nano-toxicity is an important issue in toxicology, and this topic has been reviewed several times. For example, Jovanović reviewed TiO2-induced toxicity via oral ingestion to assess the safety of TiO2 as an additive in human food.9 Shi et al. determined the toxicity of TiO2 NPs in terms of acute, sub-acute, sub-chronic or chronic exposure conditions, as well as the genotoxicity, carcinogenicity, and the reproductive and developmental toxicity of TiO2 NPs.10 In addition, the in vivo toxic effects of TiO2 NPs in different systems have been reviewed.11 However, studies on the systemic toxicity of TiO2 NPs, exposure routes, doses and timing of TiO2 NPs, bio-distribution/bio-accumulation, toxicokinetics, and potential toxic mechanisms following exposure to TiO2 NPs in in vivo experiments in mice and rats have not been reviewed. Our research group has been engaged in TiO2 nanotoxicity studies for more than 8 years, and we have found that TiO2 NP exposure induced toxicity in various organs in mice.

Therefore, in the present review, we comprehensively evaluated the current knowledge regarding TiO2 NPs including exposure mode, bio-distribution/bio-accumulation, target organs (toxicokinetics), and potential toxic mechanisms following exposure to TiO2 NPs in in vivo experiments in mice and rats. These findings may provide an important reference for human risk evaluation and management following TiO2 NP exposure.

2. Application and exposure routes

Applications

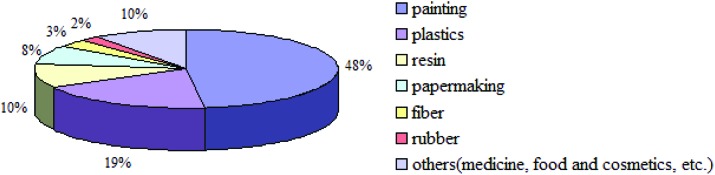

TiO2 NPs are currently widely used in various industries including paints (48%), plastics (19%), resin (10%), papermaking (8%), fiber (3%), rubber (2%), and others (medicine, food and cosmetics; 10%) due to their high stability, anti-corrosion, and efficient photocatalysis.12Fig. 1 shows the various applications of TiO2 NPs.

Fig. 1. The application areas of TiO2 NPs.12.

Exposure routes and in vivo toxicokinetics

TiO2 NPs gain entry to the body via various routes, but mainly through the respiratory tract, GIT, skin and following injection.

Inhalation, and intranasal or intratracheal instillation

TiO2 NPs enter the body through the respiratory tract and skin due to their small particle size. The major routes of TiO2 NP exposure in the workplace are inhalation and dermal exposure. The respiratory system consists of the respiratory tract and lungs. The respiratory tract includes the nasal cavity, pharynx, larynx, trachea and bronchi. NPs potentially enter the body both through inhalation, and intranasal or intratracheal exposure. Simko and Mattsson13 found that TiO2 NPs were distributed in different regions of the respiratory tract after inhalation.

A small fraction of TiO2 NPs were transported from the airway lumen to the interstitial tissue that subsequently entered the systemic circulation in WKY/NCrl BR rats.14 Wang et al. reported that NPs were relocated to the brain through the olfactory nerve after intranasal instillation of TiO2 NPs (80 nm, rutile; 155 nm, anatase).15 The majority of deposited TiO2 NPs were transferred to the interstitial space in rats following intratracheal instillation for 42 days, and the bio-accumulation of 80 nm rutile NPs was found to be greater than that of 155 nm anatase NPs.16 A small fraction of pulmonary NPs gained entry into the blood circulation and reached extra-pulmonary tissues.17 A plasma metabonomics study in rats intratracheally injected with TiO2 NPs showed that the liver, kidney and heart were potential target organs.18

Oral or gavage

Due to the wide use of TiO2 NPs in food colorants, ingestion has become a potential exposure route. Following oral exposure, NPs then enter the GIT, which is a significant absorption route for TiO2 NPs.19,20 Weir et al. found that candies and gums contain abundant TiO2 NPs with a particle size less than 100 nm.21 In recent years, GIT absorption of NPs has been a novel way of developing effective carriers to enhance the oral intake of drugs and vaccines in the field of nanomedicine.22 Evidence shows that oral exposure to TiO2 NPs (5 g kg–1) induced hepatic histopathologic damage, as the NP-treated group exhibited alterations in serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and alpha-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase (α-HBDH) levels indicating myocardial injury compared with the controls.23 Our research group also reported that toxic damage in the brain was observed in mice following TiO2 NPs administered by gavage (5 nm, anatase).24

Dermal

Whether TiO2 NPs penetrate human skin and enter the body has attracted widespread attention due to their extensive application in various sunscreens and cosmetics. It is difficult for inorganic particles to penetrate intact human skin due to the strong protective effect of the stratum corneum (SC). Some investigations have shown that NPs are unable to penetrate intact human skin.25–29 However, some studies have shown the opposite findings.30,31 Therefore, there is controversy as to whether TiO2 NPs induce toxicity via dermal deposition.

Injection

Intraperitoneal injection and intravenous injection are the most common methods of administration, by which NPs can then directly enter the blood circulation. Chen et al. reported that TiO2 NPs deposited in the liver, kidney, spleen and lung, especially the spleen, induced hepatocyte apoptosis and fibrosis, and glomerular swelling in mice after intraperitoneal injection of 3.6 nm anatase NPs (324, 648, 972, 1296, 1944 and 2592 mg kg–1) for 24 h, 48 h, 7 d and 14 d.32 The order of the TiO2 NP distribution (70/30 anatase/rutile, 20–30 nm) in the intravenously injected rats was liver > spleen > lung > kidney.33

In vivo toxicokinetics

The administration of TiO2 NPs can be carried out by any route: inhalation, and intranasal or intratracheal instillation with regard to the respiratory tract (RT) and lungs, gavage or oral exposure with regard to the GIT, intravenous or intraperitoneal injection with regard to the blood circulation and by dermal exposure with regard to the skin. When TiO2 NPs are transported into the systemic circulation, they potentially interact with platelets, coagulation factors, red or white blood cells and plasma–proteins,34 which may have a significant effect on the distribution, metabolism, and excretion of NPs.35

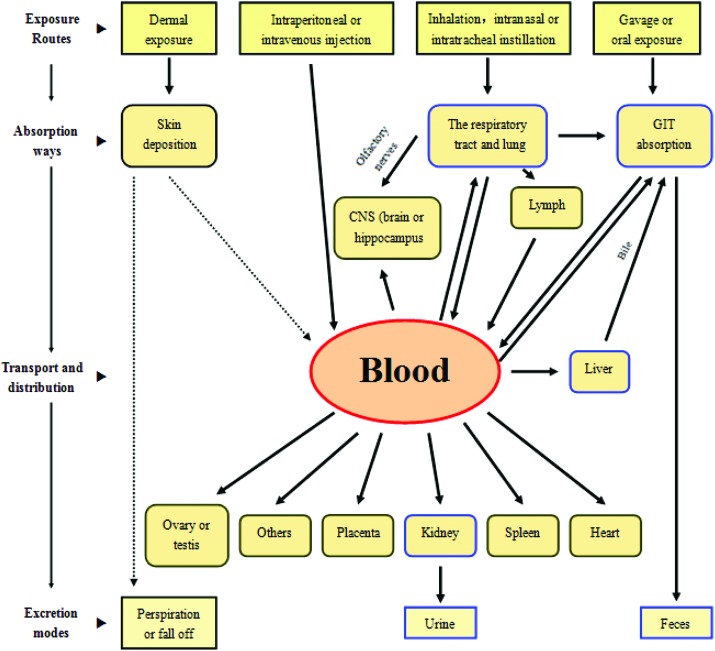

In general, NPs can be distributed to all organs or tissues from the original site by the blood circulation (Fig. 2).10 However, under normal conditions, TiO2 NPs may not have the potential to penetrate intact skin and enter the human body due to the protective effect of the SC, although an in vitro study showed that anatase-TiO2 (0–150 μg ml–1) caused cytotoxicity in the HEL-30 mouse keratinocyte cell line.36 It is not known whether TiO2 NPs have a marked effect on the body after dermal exposure.

Fig. 2. The toxicokinetics of TiO2 NPs in vivo (the arrows in dotted lines represent uncertainties).10.

The central nervous system (CNS) is the potential target of inhaled NPs. Wang et al. demonstrated that intranasal instillation of TiO2 NPs (80 nm/155 nm, rutile/anatase) entered the CNS via the olfactory nerve and caused potential brain lesions.37 TiO2 NPs with a diameter of 35 nm caused pregnancy complications when intravenously injected into pregnant mice.38 These NPs were deposited in the placenta, fetal liver and fetal brain. The treatment groups had smaller uteri and smaller fetuses than the controls. It was revealed that mice prenatally exposed to TiO2 NPs (25 and 70 nm; 16 mg kg–1) by subcutaneous administration led to genital and CNS damage in male offspring.39 Furthermore, NPs were found in the testes and brain of 6-week-old exposed male mice. The above results indicate that TiO2 NPs can penetrate the blood–testis, blood–brain and blood–placenta barriers.

The major pathway for NP clearance from the RT and alveoli is mucociliary transport to the larynx from where they can be eliminated in the sputum or inhaled and then enter the GIT. However, there is evidence that not all NPs are removed by mucociliary clearance from the lung surface, resulting in prolonged TiO2 NP retention.40 Only 25% of NPs were removed by mucociliary clearance within 24 h, while the rest were retained for more than 48 h, which potentially further interacted with the inner lung surface cells, especially macrophages, and dendritic and epithelial cells,41 and enhanced the probability of NPs traversing the epithelial barrier. The uptake of NPs by alveolar macrophages which transport them to the larynx is also a key factor in TiO2 NP clearance in the airway and alveoli. However, Geiser et al. found that lung surface macrophages did not efficiently phagocytose NPs after aerosol inhalation. As a result, the deposited TiO2 NPs may relocate from the lung surface into pulmonary tissue, enter the lymphatic drainage and then the blood circulation, favoring subsequent translocation and accumulation in extra-pulmonary organs or tissues.42

In addition to the clearance mechanisms in the respiratory system, clearance of TiO2 NPs can also occur by two other pathways, kidneys/urine and bile/feces. The International Program on Chemical Safety for TiO2 showed that the majority of ingested TiO2 are eliminated in urine.43 Therefore, it can be hypothesized that TiO2 NPs deposited in the kidney may be excreted via urine. It is well known that elimination of particles from the liver is via bile into the feces for pharmaceutics and is also adopted for TiO2 NP elimination.44 Moreover, clearance of NPs not absorbed by the gut epithelium from the body may occur via this pathway. Although a significant number of absorbed TiO2 NPs can be rapidly eliminated, it is possible that not all of these NPs will be excreted from the body. As a result, these NPs may accumulate in systemic organs and tissues after continuous exposure, leading to nanotoxicity.8

3. Potential mechanisms involved in in vivo toxicity

There is sufficient evidence to suggest that TiO2 NPs can induce toxicity in various organs, including the lung, liver, stomach, intestine, kidney, spleen, brain, hippocampus, heart, blood vessels, ovary and testis, and potential toxicity mechanisms in mice and rats have been investigated.

Lung

Mice were exposed to TiO2 NPs (2–5 nm) by whole-body inhalation exposure.45 In acute tests with 0.77 or 7.22 mg per m3 TiO2 NPs (4 h), there was no obvious toxic effect on lung tissue. In sub-acute tests (8.88 mg m–3, 4 h per day for 10 days), NPs caused an increase in total cell counts and alveolar macrophages in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) after 1 or 2 weeks of exposure, which recovered by week 3 post-exposure. When mice were treated with 0.1 or 0.5 mg TiO2 NPs by intratracheal injection for 3 days, and 1 and 2 weeks, Chen et al. found that NPs induced histopathologic changes in lungs including pulmonary emphysema, macrophage accumulation and epithelial cell apoptosis.46 Microarray analyses showed that the expression of genes involved in the cell cycle, apoptosis, chemokines, and complement cascades was altered. In particular, the expression of the placental growth factor (PLGF) and other chemokines (CXCL1, CXCL5, and CCL3) was up-regulated in the TiO2 NP-treated mouse lung, which may have contributed to pulmonary emphysema and alveolar epithelial cell apoptosis.

Our research group investigated the potential effects of long-term (90 consecutive days) exposure to TiO2 NPs (2.5, 5 and 10 mg per kg BW) in mice. It was found that exposure to TiO2 NPs caused significant accumulation of NPs in the lung, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, increased lipid peroxidation, decreased antioxidant capacity, and enhanced expression of inflammatory cytokines such as nuclear factor (NF)-κB, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, cyclooxygenase (COX)-2, heme oxygenase (HO)-1 and interleukin (IL)-2 in a dose-dependent manner.47 In addition, TiO2 NPs (10 mg per kg BW) showed a time-dependent toxic response in the mouse lung, and induced the expression of nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) which may have a protective effect against NP-induced pulmonary damage during certain exposure terms.48

Rossi et al. examined BALB/c mice after inhalation of uncoated TiO2 NPs, SiO2 NPs and silica-coated TiO2 NPs (cnTiO2) at a concentration of 10 mg m–3, and the results showed that only cnTiO2 exposure induced pulmonary neutrophilia, accompanied by increased expression of TNF-α and CXCL1 in lung tissue.49 Following exposure of the Dark Agouti (DA) rat lung to TiO2 NPs (5 mg per kg BW) for up to 90 days, the innate immune activation of eosinophils, neutrophils, dendritic cells, and natural killer (NK) cells, followed by long-lasting activation of lymphocytes involved in adaptive immunity was induced by these NPs.50 In general, exposure to TiO2 NPs may lead to histopathologic changes, and the release of ROS in the lung or pulmonary inflammation in vivo. These findings were supported by a recent study.51

Liver, stomach and intestine

When 5–150 mg per kg BW of TiO2 NPs were injected intraperitoneally into ICR mice daily for 14 days, it was found that the NPs significantly accumulated in the liver, resulting in histopathological changes, hepatocyte apoptosis, the inflammatory response, and liver dysfunction in mice.52

Following 30 days of exposure to TiO2 NPs (62.5, 125 and 250 mg per kg BW), hepatic histopathological changes and liver dysfunction were observed in NP-treated mice, possibly related to reductions in IL-2 activity, white blood cells, red blood cells, hemoglobin, the mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration, thrombocytes, reticulocytes, T lymphocytes, NK lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, the ratio of CD4 to CD8, and enhancements in the NO level, mean corpuscular volume, mean corpuscular hemoglobin, red cell distribution width, platelets, hematocrit, mean platelet volume, markers of hemostasis and immune response damage.53 Moreover, TiO2 NPs (5–50 mg per kg BW) induced oxidative stress (OS), hepatocyte apoptosis, and alterations in the expression levels of genes involved in NP detoxification/metabolism regulation and radical scavenging action in the mouse liver after administration for 60 consecutive days.54 In particular, we found that the potential mechanism of liver injury in NP-stimulated mice may occur through activation of the TNF-α → TLRs → NIK → IκB kinase → NF-κB → inflammation → apoptosis → liver injury signaling pathway.55

To investigate the long-term and low-dose effects of TiO2 NPs, mice were exposed to 2.5–10 mg per kg BW TiO2 NPs by intragastric administration daily for 90 days or 6 months. The results indicated that NPs accumulated in the liver and aggregated in hepatocyte nuclei, leading to an inflammatory response, hepatocyte apoptosis or necrosis, and liver dysfunction. The expression of 785 genes related to the immune/inflammatory response, apoptosis, OS, metabolic process, stress response, cell cycle, ion transport, signal transduction, cell proliferation, cytoskeleton, and cell differentiation changed in the mouse liver following exposure to 10 mg per kg BW TiO2 NPs. In particular, the significant alterations in complement factor D (CFD) and Th2 factor expression were related to the hepatic immune/inflammatory response.56,57

When male Wistar albino rats were treated with TiO2 NPs (up to 252 mg per animal), hepatic histological alterations such as hydropic degeneration, fatty degeneration, chronic infiltration by inflammatory cells, congested dilated central veins, generation of ROS, altered serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activities and hepatocyte atrophy, apoptosis and necrosis were observed.58

Using proteomics methods, Tananova et al. showed that the protein spots were altered and the expression of several proteins was activated in rat liver microsomes after treatment with intragastric TiO2 NPs at doses of 0–10 mg per kg BW daily for 28 days,59 suggesting that TiO2 NPs increased the serum liver enzyme activities, liver coefficient and malondialdehyde (MDA) levels in mice. Azim et al. also showed that TiO2 NPs suppressed the hepatic glutathione (GSH) level and triggered both inflammatory and apoptotic responses. Moreover, the NPs activated caspase-3 and caused damage to liver DNA.60 TiO2 NPs may have effects on small intestinal mucosa in rats.61 Wang et al. revealed the negative results of TiO2 NPs in rats following daily oral exposure (0–200 mg per kg BW) for 30 days.62 Liver edema and non-allergic mast cell activation in stomach tissues were found in young rats, while decreased intestinal permeability and molybdenum contents, and slight liver injury were observed in adult rats.62 Recently, Shakeel et al. revealed that higher doses of TiO2 NPs resulted in steatosis, necrosis, ballooning degeneration, apoptosis and fibrosis, reductions in the activities of CAT, SOD, and GST as well as elevations in ALP, ALT, AST, MDA and GSH in the liver and blood of rats after 28 days of exposure.63 The interaction of TiO2 NPs with genotoxicity and possible induction of chronic gastritis in mice were also studied in vivo.64 In this study, mice were orally administered different concentrations (5, 50 and 500 mg per kg BW) of NPs daily for 5 days, and then sacrificed 24 h or 1 or 2 weeks after the last treatment. The results showed that TiO2 NPs resulted in apoptotic DNA fragmentation, mutations in p53 exons (5–8) and significant elevations in MDA and nitrogen oxide (NO) levels as well as decreases in the reduced GSH level and catalase (CAT) activity in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Histopathological examination showed evidence of necrosis and inflammation. Thus, exposure to TiO2 NPs, even at low doses, led to the accumulation of NPs in mice, resulting in OS, inflammation and apoptosis, and ultimately the induction of chronic gastritis.64

Kidney

TiO2 NPs can be used in solid-phase extraction to preconcentrate and gauge lead (Pb) in river water and sea water. Zhang et al. investigated the possible acute toxicity of the interaction between TiO2 NPs (50 and 120 nm, 5 mg per kg BW) and PbAc in adult mice.65 They found that there was a significant difference in the damage to kidneys between the groups treated with NPs alone or the TiO2 and PbAc mixture. Although there was no clear evidence that TiO2 NPs and PbAc result in synergistic acute toxicity in the mouse kidney after oral administration, PbAc may, to some extent, increase the acute toxicity of NPs.

Our research group demonstrated that TiO2 NPs induced OS, resulting in nephritis in mice.66 In this study, Ti accumulation and histopathological changes were observed in the kidney, accompanied by an increase in ROS and MDA generation, and a decrease in antioxidase activity and total antioxidant capacity as well as antioxidants. In addition, kidney function was disrupted, including an increase in creatinine, calcium and phosphonium, and a reduction in uric acid and blood urea nitrogen. When mice were intragastrically exposed to TiO2 NPs (2.5–10 mg per kg BW) for 90 consecutive days, we also found similar kidney injury, including peroxidation of lipids, proteins and DNA, and histopathological damage characterized by a reduction in the number of renal glomeruli, fatty degeneration, disorganization of renal tubules, infiltration of inflammatory cells, tissue necrosis, GSH depletion, excessive production of ROS and nephrocyte apoptosis, necrosis, and dysfunction.

Accumulation of ROS may have contributed to kidney damage in TiO2 NP-treated mice in our previous studies, and thus the potential mechanisms of nephrotoxicity in mice induced by TiO2 NPs were investigated. The results showed that NF-κB was activated after NP exposure, promoting the expression of TNF-α, macrophage migration inhibitory factor, the IL family including IL-4, 6, 8, 10 and IL-1β, cross-reaction protein (CRP) and IFN-γ, while Hsp 70 expression was inhibited. These findings suggested that kidney injury induced by TiO2 NPs in mice was associated with alterations in inflammatory cytokine expression and a reduction in the detoxification of NPs.67 Inhibition of Nrf2 expression, which regulates the expression of genes encoding many antioxidants and detoxifying enzymes, along with down-regulation of its target gene products including HO-1, the glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit and glutathione S-transferase (GST) were observed in the TiO2 NP-treated mouse kidney. This indicated that NP-induced mouse kidney injury was potentially associated with the Nrf2 signaling pathway.68

The interaction of ROS/RNS (reactive nitrogen species) related signaling pathways in chronic renal damage induced by intratracheal instillation of TiO2 NPs in mice was investigated.69 Renal pathological changes increased in a dose-dependent manner. The contents of nitrotyrosine, iNOS, hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), HO-1, TGF-β and collagen I, markers of ROS/RNS and renal fibrosis, were enhanced in the kidney. In addition, nephrotoxicity caused by TiO2 NPs was mitigated by inhibition of iNOS and ROS scavenging treatment, suggesting that renal fibrosis caused by NPs may be associated with a ROS/RNS-related HIF-1α-upregulated TGF-β signaling pathway.69 Our recent studies confirmed the ability of TiO2 NPs to trigger renal fibrosis in mice potentially associated with induction of chronic renal inflammation and activation of the Wnt pathway including increased expression of Wnt2, Wnt3, Wnt4, Wnt5a, Wnt6, Wnt7a, Wnt9a, Wnt10a, Wnt11, Fz1, Fz5, Fz7, LRP5, Abcb1b, cyclin D1, Myc, Col1a1, Fn, Twist, and α-SMA, and decreased expression of Dkk1, Dkk2, Dkk3, Dkk4, and sFRP/FrzB,70 activation of the TGF-β/Smads/p38MAPK pathway including increased expression of TGFβ1, Smad2, Smad3, ECM, a-SMA, p38MAPK, and NF-κB, and reduced Smad7 expression in renal inflammation and fibrosis in mice.71

Spleen

Investigations into the toxicity of TiO2 NPs in the mouse spleen have been conducted by our research group. Mice were intraperitoneally injected with TiO2 NPs at concentrations of 5–150 mg per kg BW daily for 45 days. We found that NPs accumulated in the spleen, resulting in pathological changes (congestion and lymph nodule proliferation) in spleen tissue, and splenocyte apoptosis. In addition, accumulation of ROS, activation of caspase-3 and -9, inhibition of Bcl-2 expression, and alterations in the levels of Bax as well as cytochrome c were observed in the NP-exposed mouse spleen.72 Furthermore, a 30-day exposure test suggested that TiO2 NPs caused OS and a reduction in immune capacity in the mouse spleen, which was mediated by the p38-Nrf-2 signaling pathway.73

In order to study chronic spleen injury induced by TiO2 NPs and its probable mechanisms, we treated mice with 2.5, 5, and 10 mg per kg BW TiO2 NPs for 90 consecutive days. Spleen histopathology significantly changed, spleen and thymus indices increased, and immunoglobulin, blood cells, platelets, hemoglobin and lymphocyte subsets in mice correlated with decreased immunity. Moreover, the expression of inflammatory and apoptotic cytokines significantly altered, resulting in splenocyte inflammation and apoptosis.74 The expression levels of macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α, eotaxin, monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1, IFN-γ, IL-13, migration inhibitory factor, CD69, protein tyrosine kinase 1, basic fibroblast growth factor, Fasl, NKG2D, NKp46, 2B4 and GzmB involved in immune responses, lymphocyte healing and apoptosis were changed.75 Furthermore, microarray analysis showed that the expression of 1041 genes concerned with immune/inflammatory responses, apoptosis, OS, signal transduction, cell proliferation/division and translation in the NP-exposed mouse spleen at a dose of 10 mg per kg BW was altered. In particular, Cyp2e1, Sod3, Mt1, Mt2, Atf4, Chac1, H2-k1, Cxcl13, Ccl24, Cd14, Lbp, Cd80, Cd86, Cd28, Il7r, Il12a, Cfd, and Fcnb may be potential biomarkers of splenic toxicity induced by TiO2 NP exposure.76

The time toxicity effect of TiO2 NPs (10 mg per kg BW for 15–90 days) on the mouse spleen was investigated. The results showed that TiO2 were deposited in the spleen, resulting in ROS overproduction, and splenic inflammation and necrosis in a time-dependent manner. In addition, the expression of COX-2, prostaglandin E2, ERK, AP-1, CRE, AKT, JNK2, MAPKs, PI3K, c-Jun and c-Fos in the spleen was activated. These findings suggested that the MAPKs/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway → AP-1/CRE induction → COX-2 expression was potentially related to the time toxic effect of TiO2 NPs in the mouse spleen.77

The systemic immune response can be induced by TiO2 NP exposure in rats. Slight congestion, increased proliferation of T cells and B cells following mitogen stimulation and enhancement of NK cell killing activity occurred in the spleen, accompanied by an increased number of B cells in the blood.78 Following intraperitoneal injection of TiO2 NPs (<25 or <100 nm) once a day for 7 days in mice, the number of splenocytes and T-lymphocytes was reduced, and the development of B-lymphocytes was delayed. In addition, NPs induced significant reductions in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated spleen cell proliferation, macrophage activity and the content of NK cells among splenocytes. Furthermore, tumor growth was subsequently promoted in mice treated with TiO2 NPs once a day for 28 days prior to implantation of B16F10 melanoma cells. These studies showed that the potential pro-carcinogenic capability of TiO2 NPs may involve the immunomodulation of B- and T-lymphocytes, macrophages, and NK cells.79 Gustafsson et al. demonstrated that DA rats had a higher immune response to inhalation of TiO2 NPs compared to BN rats with induced allergic airway disease, which may be influenced by genetic variation.80

The regulating effect of TiO2 NPs to sensitization induced by dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB) in BALB/c mice via subcutaneous injection was investigated.81 TiO2 NPs induced an increase in lymph node proliferation, augmentation of the Th2 response, and alterations in IL-4 and IL-10 levels, leading to increased dermal sensitization potency of DNCB. When NC/Nga mice were intradermally injected with TiO2 NPs (15, 50 or 100 nm) and mite allergen in their right ears, overproduction of IL-4, an increase in total IgE and histamine in the serum, reduction in IFN-γ, and augmentation of IL-13 expression in the ear were observed.82 These findings demonstrated that NPs aggravated AD-like skin lesions under skin barrier dysfunction/defect conditions related to mite allergen, potentially dependent on Th2-biased immune responses or histamine release in NC/Nga mice.

Brain

The CNS is a potentially susceptible target following TiO2 NP exposure. TiO2 NPs can cause increased generation of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and TNF-α, augmentation of the binding activity of NF-κB, increased levels of ROS and activation of microglia in the septic brain of C57BL/6 mice induced by LPS exposure.83 Our research group investigated the short exposure (14 days) toxicity of TiO2 NPs (0–150 mg per kg BW) in mice. The results showed that NP toxicity in the brain exhibited a dose-dependent increase, inducing brain damage and OS.84 For example, filamentous neurons and inflammatory neurocytes were found after high-dose TiO2 NP treatment, and increased lipid peroxidation, decreased antioxidative capacity, accumulation of NO, and reduced glutamic acid and acetylcholinesterase activities were observed in the brain of TiO2-treated mice. When the mice were treated with TiO2 NPs (5, 10 and 50 mg per kg BW) daily for 60 days, we found that the contents of the elements Ca, Mg, Na, K, Fe and Zn, the activities of Na+/K+-ATPase, Ca2+-ATPase, Ca2+/Mg2+-ATPase, acetylcholine esterase and NO synthase, and the levels of some monoamine neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine and dopamine were altered, and the central cholinergic system was disturbed in the brain.85 In addition, accumulation of NPs, ROS and apoptosis accompanied by changes in the levels of caspase-3 and -9, Bcl-2, Bax and cytochrome c were seen in the hippocampus.86 These factors potentially led to impairment of spatial recognition memory in TiO2 NP-exposed mice.

These authors also conducted sub-chronic exposure experiments in which mice underwent intragastric or intranasal administration of 2.5–10 mg per kg BW TiO2 NPs for 90 consecutive days. TiO2 NPs induced pathological changes, neuroinflammation and spatial recognition impairment, and resulted in a significant reduction in long-term potentiation (LTP) and down-regulation of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor subunit (NR2A and NR2B) expression with concomitant inhibition of CaMKIV, cyclic-AMP responsive element binding proteins (CREB-1, CREB-2) and FosB/DFosB in hippocampal tissues.87,88 Furthermore, oxidative damage caused by TiO2 NPs in the brain was possibly related to the p38-Nrf-2 signaling pathway.89 Microarray data showed alterations in the expression of 249 known functional genes, especially Col1a1, serine/threonine-protein kinase 1, Ctnnb1, cysteine-serine-rich nuclear protein-1, Ddit4 and Cyp2e1 following exposure to 10 mg per kg BW TiO2 NPs, which contributed to the brain toxicity of NPs in mice.24 In a long-term (6 or 9 months) and low-dose (1.25–5 mg per kg BW) TiO2 NP exposure test, we proved that NPs also caused neurotoxicity which involved dysfunction of glutamate metabolism and its receptor expression,90 and impaired NMDA receptor-mediated postsynaptic signaling cascade,91 as well as mediation of neurotrophins and related receptor expression in mice.92

TiO2 NPs have the potential to penetrate the blood–placenta barrier and blood–brain barrier. Mohammadipour et al. and Gao et al. treated pregnant rats with TiO2 NPs (100 mg per kg BW) daily from gestational day (GD) 2 to (GD) 21.93,94 The results showed that NPs significantly decreased hippocampal cell proliferation, impaired learning and memory, and affected synaptic plasticity in the hippocampal dentate gyrus area in newborn rats. When rats were prenatally exposed to TiO2 NPs for 6–18 GD, the antioxidant status was impaired, oxidative damage to nucleic acids and lipids was induced by NPs in the brain of rat offspring, and the depressive-like behaviors during adulthood in the force swimming test and the sucrose preference test were enhanced.95

Heart and blood vessels

To investigate the negative effects of TiO2 NPs on the cardiovascular system in mice, our research group exposed mice to TiO2 NPs (5 nm, anatase) daily for 90 days.96 The results suggested that NPs accumulated in the heart, leading to sparse cardiac muscle fibers, inflammation, cell necrosis, and cardiac biochemical dysfunction. In addition, TiO2 NPs potentiated the production of ROS and lipids, protein and DNA peroxidation, and disturbed the antioxidant system in the mouse heart. Our recent research indicated that TiO2 NPs increased the expression of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, NF-κB, IL-4, IL-6, CK, CRP, ET-1, TGF-β, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), MCP-1, STAT1, STAT3, STAT6, T-bet, GATA3, GATA4, IFN-α, IFN-γ, p-PKC and p-ERK1/2 in the mouse inflamed heart.97,98 These findings indicated that cardiac lesions induced by exposure to TiO2 NPs may be mediated by alterations in Th1- or Th2-related cytokine expression,97 and NF-κB activation via the PKCε or ERK1/2 signaling cascades in mice.98

Rats were treated with alloxan to induce OS conditions before exposure to different doses (0.5, 5 and 50 mg per kg BW) of TiO2 NPs.99 The findings showed that NPs led to significant reductions in heart-related functional indices, and increased the concentrations of cardiac troponin I and creatine kinase-MB under OS conditions, suggesting that OS promoted the adverse effects of TiO2 NPs in the rat heart. Activation of the complement cascade and inflammatory response in the heart, and specific activation of complement factor 3 in the blood in C57BL/6 mice after TiO2 NP exposure were demonstrated in a recent study.100

Nurkiewicz et al. assessed the detrimental effects of TiO2 NPs on microvascular function in rats. A23187 infusion used to evaluate endothelium-dependent arteriolar dilation, indicated that TiO2 NP exposure resulted in arteriolar constrictions or impaired vasodilator responses.101 Exposure to 10 μg TiO2 NPs by inhalation for 24 h in rats caused enhancement of spontaneous tone in coronary arterioles and impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation in subepicardial arterioles;102 reduced microvascular NO bioavailability, increased adrenergic receptor sensitivity and altered COX-mediated vasoreactivity;103 increased the production of microvascular ROS and significant impairment in endothelium-dependent vasoreactivity in coronary arterioles.104 In addition, when rats were treated with TiO2 NPs at concentrations of 1.5 to 16 mg m–3 for 4 to 12 h, a significant increase in microvascular OS, a decrease in endothelium-dependent arteriolar dilation and microvascular NO production, and induction of the inflammatory process and systemic microvascular dysfunction were observed.105 Moreover, similar toxic effects following NP deposition in a dose-dependent manner were exhibited in rats following treatment with 4–90 μg TiO2 NPs.106

Modest effects on vasodilatory function and atherosclerotic plaque progression in the aorta were found following exposure to 0.5 mg per kg BW TiO2 NPs in ApoE(–/–) mice, an atherosclerosis susceptible animal model.107 Our research group investigated the interaction of TiO2 NPs (1.25, 2.5 or 5 mg per kg BW) by nasal instillation for 9 consecutive months with atherogenesis in mice. The data showed that NPs altered serum parameters such as NAD(P)H oxidase 4, CRP, E-selectin, endothelin-1, tissue factor, ICAM-1 and CVAM-1, resulting in atherogenesis coupled with pulmonary inflammation.108 Savi et al. reported that the cardiac conduction velocity and tissue excitability were increased, resulting in an enhanced propensity for inducible arrhythmias in rats exposed to TiO2 NPs (2 mg kg–1).109 Another study on TiO2 NP-treated ApoE(–/–) mice, revealed that NPs induced severe systemic inflammation (altered CRP level), endothelial dysfunction (altered level of NO and activity of eNOS) and lipid metabolism dysfunction (altered TC and HDL-C contents), contributing to the progression of atherosclerosis.110

Ovary and testis

When female mice were daily exposed to TiO2 NPs (2.5, 5 and 10 mg per kg BW) administered intragastrically for 90 days, the data showed that NPs accumulated in the ovary, resulting in significant reductions in the body weight, relative ovary weight and fertility. Altered hematological, serum parameters, and sex hormone levels, increased follicle atresia, and ovary inflammation and necrosis were also observed in TiO2 NP-treated mice.111 In addition, OS, ovarian damage, disrupted balance in mineral distributions and sex hormones, and reduced fertility or pregnancy rate were found in mice following exposure to 10 mg per kg BW TiO2 NPs. NP-exposed mice had higher expression of Cyp17a1 related to estradiol biosynthesis and Akr1c18 involved in progesterone metabolism compared with control mice, indicating that ovarian dysfunction caused by TiO2 NPs in mice may, to some degree, be via the regulation of key ovarian genes.112

Male Kunming mice were used to investigate the underlying effects of TiO2 NP (10–250 mg per kg BW) exposure on testosterone (T) synthesis and spermatogenesis from the postnatal day 28 (PND 28) to PND 70.113 The results showed that TiO2 NPs increased spermatozoa abnormalities in the epididymis, decreased the layers of spermatogenic cells and vacuoles in seminiferous tubules, reduced the serum T levels, and altered the expression of 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase and P450 17α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase in the testis as well as cytochrome P450-19, a key enzyme in the translation of T to estradiol (E2). These results suggested that TiO2 NPs decreased the levels of serum T via alterations in both the synthesis and translation of T, resulting in reduced spermatogenesis in NP-exposed mice. Recently, we reported that testicular damage, sperm malformations, altered levels of serum sex hormones, changes in gene expression involved in spermatogenesis, and steroid and hormone metabolism were induced following TiO2 NP exposure in male mice.114 Furthermore, TiO2 NPs were demonstrated to alter the expression of testis-specific genes including Cdc2, Cyclin B1, Dmcl, TERT, Tesmin, TESP-1, XPD, XRCCI, Gsk3-β, and PGAM4 genes and proteins in the mouse testis,115 and cause biochemical dysfunction, including decreased lactate dehydrogenase, sorbitol dehydrogenase, succinate dehydrogenase, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, Na+/K+-ATPase, Ca2+-ATPase, and Ca2+/Mg2+-ATPase, and increased activities of acid phosphatase, alkaline phosphatase, and nitric oxide synthase in the testis,115 thus leading to suppression of spermatogenesis.115,116 Moreover, long-term exposure to TiO2 NPs resulted in low fertility and testicular inflammation in mice, which was demonstrated to involve numerous biomarkers of immune function impairment in the testis, e.g., TiO2 NPs suppressed the expression of TAM receptors and SOCS1/3, and induced the expression of TLRs and pro-inflammatory cytokines. The reproductive toxicity and immunological dysfunction in male mice induced by long-term exposure to TiO2 NPs may be closely associated with dysfunction of the TAM/TLR3-mediated signaling pathway in the mouse testis.117

TiO2 NPs at concentrations of 5, 25 and 50 mg kg–1 by intravenous injection induced OS, decreased the activities of antioxidant enzymes, increased lipid peroxidase, reduced the sperm count, decreased testosterone activity, and led to cell apoptosis in male Wistar rats.118 Short-term (5 days) oral exposure to anatase-TiO2 NPs (0–2 mg per kg BW per day) in rats induced histological alterations (ovarian granulosa) in females, increased T levels in high-dose males and decreased T levels in females.119 Exposure to TiO2 NPs in pregnant rats caused toxicity in rat offspring,93–95 suggesting that NPs have the ability to penetrate the blood–placental barrier, resulting in reproductive toxicity.

The in vivo toxicity of TiO2 NPs in mice and rats is summarized in Table 1. Taken together, TiO2 NPs may reach various organs by means of the blood circulation via various routes, inducing multiple negative effects. It is noteworthy that the routes of exposure, particle size, exposure dose, time and model, and surface conditions should be a focus of research due to their significant influence on NP-induced systemic toxicity.

Table 1. The in vivo toxicity of TiO2 NPs in mice or rats.

| Target system | Size & structure | Model | Dose (mg kg–1) | Exposure route | Exposure time | Result | Ref. |

| Lung | 2–5 nm, An | Mice | 8.88 mg m–3 | INH | 4 h d–1 for 10 d | Macrophages↑ in BALF, pneumonia | 45 |

| 19–21 nm, Ru | Mice | 0.1 or 0.5 mg | I.t. | 3 d, 1 w, 2 w | Emphysema & apop. | 46 | |

| 5 nm, An | Mice | 2.5, 5 & 10 | I.t. | 90 d | Pulmonary OS, infla. | 47 | |

| 5 nm, An | Mice | 10 | I.t. | 15–90 d | Lung OS, edema, infla., apop., Nrf2↑ | 48 | |

| Si-Coated | Mice | 10 mg m–3 | INH | 2 h, 2 h/4 d for 4 w | Pulmonary neutrophilia & infla. | 49 | |

| 21 nm, An/Ru | Rats | 5 | I.t. | Up to 90 d | Innate immune & lymphocytes↑ | 50 | |

| 18 nm, An/Ru | Rats | 15, 30, 60 & 70 | I.p. | 21 d | Lung pathologic damage, OS | 51 | |

| Liver, stomach and intestine | 5 nm, An | Mice | 5, 10, 50, 100 & 150 | I.p. | 14 d | Liver pathologic damage, infla., apop., dysfunction | 52 |

| 5 nm, An | Mice | 62.5, 125 & 250 | I.g. | 30 d | Liver dysfunction, coagulation & immune system damage | 53 | |

| 5 nm, An | Mice | 5, 10 & 50 | I.g. | 60 d | Liver pathologic damage, OS, infla., apop., dysfunction | 54, 55 | |

| 5 nm, An | Mice | 2.5, 5 & 10 | I.g. | 90 d or 6 m | Hepatic infla., apop., changes in gene expression, liver dysfunction | 56, 57 | |

| 50.4 ± 5.6 nm (TEM), An | Rats | 63, 126 & 252 mg | I.p. | 24 & 48 h | Liver ROS release, hepatocytes atrophy, apop. & necrosis | 58 | |

| — | Rats | Up to 10 | I.g. | 28 d | Changes of protein spots, proteins expression↑ in liver microsomes | 59 | |

| 21 nm, An | Mice | 150 | Oral | 2 w | Liver dysfunction, infla., apop., DNA damage | 60 | |

| 75 ± 15 nm (TEM), An | Rats | 10, 50 & 200 | Oral | 30 d | Liver edema, non-allergic mast cell↑ in stomach; intestinal permeability & Mo contents↓ | 62 | |

| 43 nm, An/Ru | Mice | 5, 50 & 500 | Oral | 5 d | OS, infla., apop., chronic gastritis | 63 | |

| 36.15 nm, An | Rats | 50, 100 & 150 | I.h. | 28 d | Liver toxicity, OS, apop., steatosis, necrosis, ballooning degeneration, and fibrosis | 64 | |

| Kidney | 50 & 120 nm | Mice | 5000 | Oral | 7 d | Kidney toxicity, oxidative damages | 65 |

| 5 nm, An | Mice | 5, 10, 50, 100 & 150 | I.p. | 14 d | Kidney pathologic changes, OS, dysfunction & nephritis | 66 | |

| 5 nm, An | Mice | 2.5, 5 & 10 | I.g. | 90 d | Renal OS, peroxidation of lipid, protein and DNA, GSH depletion, nephritis, dysfunction, vital gene expression changed | 67, 68 | |

| — | Mice | 0.1, 0.25 & 0.5 mg | I.t. | 4 w | ROS/RNS release, renal fibrosis | 69 | |

| 5 nm, An | Mice | 1.25, 2.5 & 5 | I.g. | 9 m | Renal fibrosis associated with infla. & Wnt pathway↑ | 70 | |

| 5 nm, An | Mice | 2.5, 5 & 10 | I.g. | 6 m | Renal infla. & fibrosis | 71 | |

| Spleen | 5 nm, An | Mice | 5, 50 & 150 | I.p. | 45 d | Splenic pathologic changes, ROS↑, apop. | 72 |

| 5 nm, An | Mice | 5, 50 & 150 | I.g. | 30 d | Spleen OS, immune capacity↓, p38-Nrf-2 pathway↑ | 73 | |

| 5 nm, An | Mice | 2.5, 5 & 10 | I.g. | 90 d | Spleen infla., apop., immune dysfunction, related gene expression changed | 74–76 | |

| 5 nm, An | Mice | 10 | I.g. | 15–90 d | Splenic ROS release, infla. | 77 | |

| 21 nm, An/Ru | Rats | 0.5, 4 & 32 | I.t. | Twice per w, 4 w | Spleen immunocyte activity↑, number of B cells↑ in blood | 78 | |

| <25 or 100 nm | Mice | — | I.p. | Once per d, 7–28 d | Tumor growth↑ involving in immunomodulation | 79 | |

| 21 nm, An/Ru | Rats | Up to 0.168 mg | INH | Up to 70 d | Immune response | 80 | |

| 10–25 nm, An | Mice | 4, 40 or 400 mg l–1 | I.h. | 1, 2 & 5 d | Dermal sensitization potency of DNCB↑ | 81 | |

| 15, 50 or 100 nm | Mice | — | I.d. | — | AD-like skin lesions↑ under skin barrier damage conditions | 82 | |

| Brain and hippocampus | 21 nm, An/Ru | Mice | 1 mg | I.p. | 2, 6 or 24 h | ROS, microglia & infla.↑ in septic brain | 83 |

| 5 nm, An | Mice | 5, 10, 50, 100 & 150 | I.p. | 14 d | Pathological changes, OS & lipid peroxidation in brain | 84 | |

| 5 nm, An | Mice | 5, 10 & 50 | I.g. | 60 d | Disturbance of the homeostasis of trace elements, enzymes and neurotransmitter systems in brain; accumulated NPs, ROS and apop. in hippocampus; damaged spatial recognition memory in mice | 85, 86 | |

| 5 nm, An | Mice | 2.5, 5 & 10 | I.g. | 90 d | Spatial recognition impairment, LTP↓, infla. in hippocampus | 87, 88 | |

| 5 nm, An | Mice | 2.5, 5 & 10 | I.n. | 90 d | Overproliferation of glial cells, OS, apop., p38-Nrf-2 pathway↑, gene expression changed in brain | 2, 89 | |

| 5 nm, An | Mice | 1.25, 2.5 & 5 | I.n. | 6 or 9 m | Neurotoxicity, dysfunction of glutamate metabolism; impaired NMDA receptor-mediated postsynaptic signaling cascade | 90, 91 | |

| 5 nm, An | Mice | 0.25, 0.5 & 1 | I.n. | 9 m | Neuroinfla., impaired neurotrophin-mediated signaling pathways | 92 | |

| <25 or 10 nm, An | Rats | 100 | I.g. | 2–21 GD | Hippocampal cell proliferation↓ & synaptic plasticity was affected, impaired learning and memory in rat offspring | 93, 94 | |

| 5 nm, An | Rats | 1000 mg l–1 | I.h. | 6, 9, 12, 15 & 18 GD | Oxidative damage to nucleic acids and lipids in the brain of newborn rats, enhanced the depressive-like behaviors during adulthood | 95 | |

| Heart and vessel | 5 nm, An | Mice | 2.5, 5 & 10 | I.g. | 90 d | Cardiac OS, sparse muscle fibers, infla., biochemical dysfunction | 96 |

| 5 nm, An | Mice | 1.25, 2.5, 5 & 10 | I.g. | 90 d, 180 d | Cardiac infla. | 97, 98 | |

| Rod-like, Ru | Rats | 0.5, 5 & 50 | I.m. I.p. | 48 h | Heart dysfunction under OS | 99 | |

| — | Mice | 18 or 162 μg | I.t. | 24 h | Heart complement cascade, infla. & complement factor 3 in blood ↑ | 100 | |

| 21 nm, P25 | Rat | 4,6,10,19 & 38 μg | INH | 24 h | Arteriolar constrictions, impaired vasodilator responses | 101 | |

| 21 nm, P25 | Rats | 10 μg | INH | 24 h | Microvascular OS, damage of vasoreactivity in artery | 102–104 | |

| 100 nm | Rats | 1.5 to 16 mg m–3 | INH | 24 h | Microvascular OS, infla., systemic microvascular dysfunction | 105 | |

| 21 nm, P25 | Rats | 4–90 μ | IN | 24 | Microvascular OS, nitrosative stress & dysfunction | 106 | |

| 21.6 nm, Ru | Mice | 0.5 | I.t. | 2 & 26 h or once per w for 4 w | Modest effects on vasodilatory function & atherosclerotic plaque progression in aorta | 107 | |

| 5 nm, An | Mice | 1.25, 2.5 & 5 | I.n. | 9 m | Altered serum parameters & atherogenesis related to pneumonia | 108 | |

| 25–35 nm | Rats | 2 | I.t. | 4 h | Cardiac conduction velocity, tissue excitability ↑, arrhythmias | 109 | |

| 5–10 nm, An | Mice | 10, 50 & 100 μg | I.t. | 6 w | Systemic infla., endothelial & lipid metabolism dysfunction, atherosclerosis | 110 | |

| Ovary and testis | 5 nm, An | Mice | 2.5, 5 & 10 | I.g. | 90 d | Altered hematological, serum parameters and sex hormone levels, atretic follicle↑, ovary infla. & necrosis, fertility↓ | 111 |

| 5 nm, An | Mice | 10 | I.g. | 90 d | OS, ovary damage & dysfunction, regulation of key ovarian genes | 112 | |

| 25 nm, An | Mice | 10, 50 or 250 | Oral | 28–70 PND | Spermatogenesis & serum testosterone↓ | 113 | |

| 5 nm, An | Mice | 1.25, 2.5, 5 & 10 | I.g. | 90 d, 180 d, 270 d | Sperm malformations, testis damage, altered levels of serum sex hormone & gene expressions; oxidative damage & apop. | 114–117 | |

| 21 nm | Rats | 5, 25 & 50 | I.v. | 30 d | OS, sperm count & testosterone activity↓, apop. | 118 | |

| An | Rats | 1 & 2 | Oral | 5 d | Ovarian granulose, changed levels of testosterone | 119 | |

| 5–25 nm, An | Rats | Up to 100 | I.g. I.h. | 2–21 GD | Reproductive toxicity | 93–96 | |

TiO2 NPs of 5 nm in size resulted in greater pulmonary toxicity than 21 nm and 50 nm TiO2 NPs in the rat lung. Increased activities of LDH and ALP were observed when the exposure dose was >5 mg kg–1, whereas 21 nm NPs increased ALP activity only if the treatment dose was 5 and 50 mg kg–1, and 50 nm TiO2 NPs showed no toxicity. In addition, when the concentration of NPs was 50 mg kg–1, phagocytosis of AMs was suppressed by 5 nm TiO2 NPs but enhanced by 50 nm NPs.120 These data suggest that the adverse effects of TiO2 NPs may be associated with the NP size and exposure dose. Bruno et al. found that TiO2 NPs were more toxic to the rat lung than TiO2 microparticles, and 5 nm TiO2 NPs particularly destroyed the antioxidant activity compensating for membrane damage in liver cells in comparison with 10 nm TiO2 NPs.121 Our research group demonstrated the dose-dependent toxicity of anatase-TiO2 NPs (5 nm), on the lung,47 liver,52,55 kidney,68,69 ovary,112 testis,114,116 brain and hippocampus84,86 in ICR mice.

Exposure time may be another important factor in the toxicity of TiO2 NPs. Our research group found that the expression of Nrf2, HO-1 and the glutamate–cysteine ligase catalytic subunit (GCLC) from 15 days to 75 days of exposure was significantly activated by TiO2 NPs, whereas 90 days of exposure caused a considerable decrease in the expression levels of these three factors in the mouse lung.48 In addition, NPs elicited a time-dependent effect in the mouse liver and spleen.56,77 Subcutaneous injection of TiO2 NPs resulted in significant immune effects in B6C3F1 mice, but no such effects were observed following oral or dermal administration of TiO2 NPs. These results provide insight into the contribution of exposure routes in TiO2 NP toxicity.122 Delivered dose rate may be a key determinant of acute respiratory tract inflammation when TiO2 NPs have an equivalent deposition. F-344 rats were treated with the same deposited doses of TiO2 NPs by single and repeated high dose rate intratracheal instillation as well as low dose rate whole body aerosol inhalation. The results indicated that high dose rate delivery caused severe inflammation compared to low dose rate delivery.123

It is necessary to take into account the alterations in toxicological potential of TiO2 NPs induced by surface coating, area or modification. Uncoated TiO2 NPs do not induce significant inflammation, whereas SiO2-coated TiO2 NPs (cnTiO2) induced pulmonary neutrophilia and inflammation in mice. The induction of acute phase response genes, inflammatory cascades, and changes in microRNAs were triggered by surface-coated TiO2NPs in C57BL/6BomTac mice.124

Rats treated with TiO2 NPs of two different specific surface areas (TiO2-S50: 50 m2 g–1, and TiO2-S210: 210 m2 g–1) showed that low-dose TiO2-S210 induced a significant decrease in SOD and GSH-Px activities in the kidney, and increased MDA levels in the liver and kidney were caused by high-dose TiO2-S210 which only appeared in the liver after TiO2-S50 exposure. SOD and GSH-Px activities in the liver or kidney in the low TiO2-S210 exposure group were significantly less than that in the low TiO2-S50 group.125 These findings suggest that the surface area of TiO2 NPs plays a vital role in NP-induced toxicity.

The exposure model, a crucial factor in TiO2 NP exposure, should not be ignored. Rossi et al. used ovalbumin to induce allergic pulmonary inflammation (asthma) in mice.126 Allergic pneumonia was dramatically suppressed by TiO2 NP treatment, while TiO2 NP-exposed healthy mice showed pulmonary neutrophilia and the inflammatory response. This suppressive effect on lung inflammation in asthmatic rats was also proved by Scarino et al.127 In contrast, TiO2 NPs exacerbated pneumonia in respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)-infected mice.128 Rats of different ages may have different toxicological sensitivities to TiO2 NPs. Toxic effects of TiO2 NPs in the liver, heart and stomach were found in young rats (3-weeks), while only slight injury in the liver and kidney, and intestinal permeability damage were found in adult (8-weeks) rats. In addition, the biomarkers for identifying oral toxicity of NPs in young and adult rats were different.60

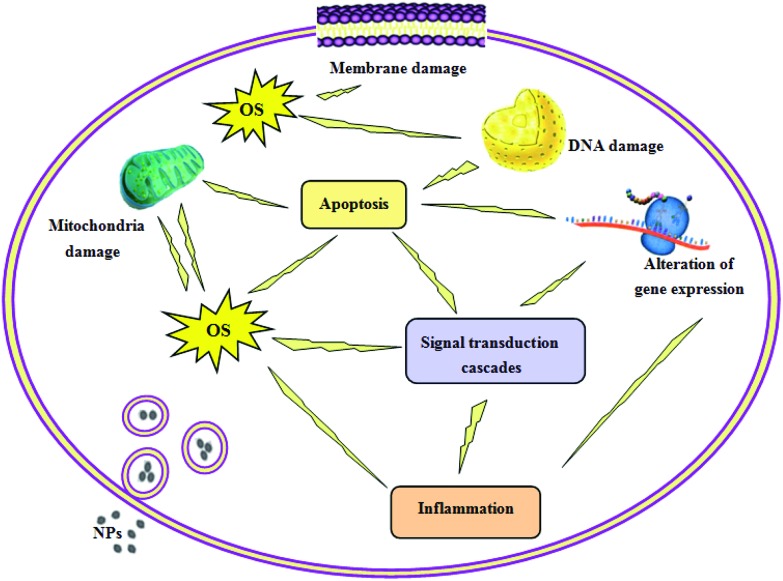

TiO2 NPs may interact with the plasma membrane resulting in membrane dysfunction and damage, and induce the production of ROS and membrane lipid layer fracture. Although the toxic mechanisms of TiO2 NPs are unclear, when NPs enter into the cells, they may induce cytotoxic responses including OS, inflammatory and apoptotic responses, oxidative DNA damage, mitochondria damage and activation of signaling pathways as well as alterations in the expression of related genes, which may be responsible for their toxicity.

The major studies mentioned in the present review have demonstrated that TiO2 NP exposure results in the production of ROS, generally accompanied by lipid peroxidation, disturbance of the antioxidant system and activation of some oxidants. This phenomenon is known as OS which is regarded as a key player in TiO2 NP-induced toxicity. Increases in the serum liver function enzyme activities, liver coefficient and MDA levels, suppression of the hepatic GSH level, and activation of inflammation as well as DNA damage were observed in TiO2 NP-exposed mice. However, when antioxidants (idebenone, carnosine and vitamin E) were administered orally, the damage caused by TiO2 NPs was alleviated.129

Our research group found that TiO2 NPs resulted in the inflammatory response by altering the expression of several pro-inflammatory cytokines (NF-κB, MIF, IL-6, IL-1β, CRP and TNF-α), potentially inducing toxicity in mice.47,51,68,75,87,96,111 Inflammation induced by exposure to TiO2 NPs is a general phenomenon, which was confirmed in other studies.100,120,123 In addition, the inflammatory process may be associated with OS. Morishige et al. reported that IL-1β production was dependent on active cathepsin B and ROS production in THP-1 cells.130 Al-Rasheed et al. reported that renal dysfunction and immuno-inflammatory response biomarkers induced by TiO2 NPs in rats were alleviated by co-administration of either quercetin or idebenone due to their antioxidant properties.131

TiO2 NPs induced OS, oxidative DNA damage, and activation of the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis in the liver of mice.79 Exposure to TiO2 NPs elevated [Ca2+]i, reduced mitochondrial membrane potential, up-regulated the expression levels of cytochrome c, Bax, caspase-3, glucose-regulated protein 78, C/EBP homologous protein and caspase-12, and down-regulated Bcl-2 expression, leading to hippocampal neuron and Sertoli cell apoptosis, which were associated with the mitochondria-mediated signaling pathway.132,133 These data indicated that mitochondria contributed to apoptosis caused by TiO2 NPs. TiO2 NP-induced apoptosis is probably mediated by OS. Pretreatment with N-(mercaptopropionyl)glycine (N-MPG), a ROS scavenger, inhibited PC12 apoptosis induced by TiO2 NPs.134 In addition, ROS generation may be attributed to mitochondrial dysfunction during mitochondrial respiration.135

Interestingly, our data showed that TiO2 NPs directly inserted themselves into DNA base pairs or were bound to DNA nucleotides that bound with three oxygen or nitrogen atoms and two phosphorus atoms of DNA with the Ti–O(N) and Ti–P bond lengths of 0.187 and 0.238 nm, respectively, inducing DNA cleavage in the mouse liver.136 These findings provide evidence that TiO2 NPs have genotoxic potential. Comet and cytokinesis-block micronucleus assays showed that TiO2 NPs induced DNA damage and a corresponding increase in the micronucleus frequency in A549 cells.137 In this study, changes in ATM, P53, Cdc-2, ATR, H2AX, and Cyclin B1 gene expression, suggesting the induction of DNA double strand breaks, were also observed via genomic and proteomic analyses. Furthermore, the results demonstrated that DNA damage may be attributed to increased OS. Another investigation on HepG2 cells indicated that the generation of ROS with a concomitant reduction in GSH levels and an increase in lipid peroxidation resulted in oxidative DNA damage after TiO2 NP treatment.138

Activation of signaling transduction cascades may be a potential mechanism of TiO2 NP-induced toxicity. Increased phosphorylation of IRS1 (Ser307) and reduced phosphorylation of AKT (Ser473) were related to the induction of insulin resistance in TiO2 NP-exposed mice.139 Our findings demonstrated the production of the Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-5, up-regulation of their target genes (IL-5, IFN-γ, GATA3, T-bet and STAT3), and down-regulation of the target gene STAT1, which contributed to the development of hepatic inflammation in mice following TiO2 NP treatment.57 Inhibition of the activation of two MAPKs, p38 and JNK with selective inhibitors SB203580 and SP600125 or by an RNA interference technique, respectively, suppressed TiO2 NP-induced apoptosis in human lymphocytes.140

The authors found that the changes in gene expression related to the immune/inflammatory response, apoptosis, OS, metabolic process, stress response, cell cycle, ion transport, signal transduction, cell proliferation, cytoskeleton, and cell differentiation may be due to the toxicity of TiO2 NPs.56,69,76,112,114 For instance, the changed expression of Ly6e, Adam3, Tdrd6, Spata19, Tnp2 and Prm1 involved in spermatogenesis, and Sc4 mol, Psmc3ip, Mvd, Srd5a2, Lep and Cyp2e1 associated with steroid and hormone metabolism may be associated with testicular damage and sex hormone disturbance induced by TiO2 NPs. Alterations in the expression of key genes also occurred in other investigations.46,141,142 The potential toxic mechanisms of TiO2 NPs are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. The potential mechanisms of TiO2 NP-induced toxicity.

4. Summary

TiO2 NPs can enter the blood circulation through various routes (respiratory tract, injection, dermal and GIT), translocated to different systems and result in toxicity in various organs including the lung, liver, stomach, intestine, kidney, spleen, brain, hippocampus, heart, blood vessels, ovary and testis in mice and rats. This toxicity is possibly associated with the routes of exposure, particle size, exposure dose, time and model, and surface conditions; OS, inflammatory and apoptotic responses, DNA damage, mitochondria damage and signaling transduction cascade response.

Current investigations into the toxicity of NPs are mainly dependent on a limited number of experimental animal studies, whereas there are few reports on the toxic effects of TiO2 NPs in the human body. In addition, full risk assessment in relation to their exposure routes requires further study, especially controversial issues such as whether TiO2 NPs penetrate intact skin and enter the human body. Further detailed studies should focus on the mechanisms of TiO2 NP-induced toxicity.

At present, only NIOSH has recommended a TiO2 NP exposure limit, related to their diverse characteristics and wide applications, making exposure hazard assessment difficult to conduct. Although the novel application of TiO2 NPs in drug delivery systems is designed to reduce the toxicity of drugs and to increase biocompatibility, they may pose a significant health risk to humans. More attention should be focused on the bio-safety evaluation of TiO2 NP carriers in drug delivery applications.

In addition, the physicochemical properties of TiO2 NPs including their crystalline structure, surface area, surface coating or modification and size distribution should be investigated in future studies. Different exposure routes, doses and timing of TiO2 NP exposure lead to different systemic responses. Interestingly, the delivered dose rate of TiO2 NPs may affect their toxicity, and the exposure model may be another explanation for the toxicity of NPs. These factors should not be ignored.

Furthermore, TiO2 NPs can cause OS and DNA damage, potentially inducing gene mutations/deletions, leading to mutagenesis, carcinogenicity, and subsequently the development of tumors and cancer. There is evidence to suggest that TiO2 NPs induce tumor-like phenotypes in AGS cells,142 and tumor growth was significantly increased when mice were pre-treated with TiO2 NPs.79 Respiratory system studies support the carcinogenicity of TiO2 NPs via intratracheal and inhalation administration.143,144 However, carcinogenic capability and the underlying carcinogenic mechanisms of TiO2 NPs require further investigation.

In conclusion, although TiO2 NPs have been studied extensively in recent years, further research is required to elucidate their possible health effects to determine risk assessment and management.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31671033, 81473007, 81273036, 30901218), the National Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (grant no. BK20161306), the Top-notch Academic Programs Project of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PPZY2015A018), and the Bringing New Ideas Foundation of Huaiyin Normal University (201510323053X). The authors gratefully acknowledge the earmarked fund (CARS-22-ZJ0504) from the China Agriculture Research System (CARS) and a project funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions, P. R. China.

References

- Roco M. C. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2001;3:353–360. [Google Scholar]

- Choi H., Stathatos E., Dionysiou D. D. Appl. Catal., B. 2006;63:60–67. [Google Scholar]

- Esterkin C. R., Negro A. C., Alfano O. M., Cassano A. E. AIChE J. 2005;51:2298–2310. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J. and Egerton T., Titanium Compounds, Inorganic, in Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology, John Wiley & Sons, New York, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kaida T., Kobayashi K., Adachi M., Suzuki F. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2004;55(2):219–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colvin V. L. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21(10):1166–1170. doi: 10.1038/nbt875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiser M., Kreyling W. G. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2010;7:2. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-7-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H. T., Ma L. L., Zhao J. F., Liu J., Yan J. Y., Ruan J., Hong F. S. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2009;129:170–180. doi: 10.1007/s12011-008-8285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovanović B. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manage. 2015;11(1):10–20. doi: 10.1002/ieam.1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H., Magaye R., Castranova V., Zhao J. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2013;10:15. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-10-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iavicoli I., Leso V., Berggamschi A. J. Nanomater. 2012;2012:36. [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. R., Tang M. J. Southeast Univ. 2011;30(6):945–952. [Google Scholar]

- Simko M., Mattsson M. O. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2010;7:42. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-7-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhlfeld C., Geiser M., Kapp N., Gehr P., Rothen-Rutishauser B. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2007;4:7. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Liu Y., Jiao F., Lao F., Li W., Gu Y., Li Y., Ge C., Zhou G., Li B. Toxicol. 2008;254:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sager T. M., Kommineni C., Castranova V. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2008;5:17. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-5-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Li J., Yin J., Li W., Kang C., Huang Q., Li Q. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2010;10:8544–8549. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2010.2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Tang M., Zhang T. Proc. ICNT. 2008;12(3):19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hagens W. I., Oomen A. G., de Jong W. H., Cassee F. R., Sips A. J. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2007;49:217–229. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomer M. C., Thompson R. P., Powell J. J. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2002;61:123–130. doi: 10.1079/pns2001134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir A., Westerhoff P., Fabricius L., Hristovski K., von Goetz N. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;46:2242–2250. doi: 10.1021/es204168d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillyer J. F., Albrecht R. M. J. Pharm. Sci. 2001;90:1927–1936. doi: 10.1002/jps.1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Zhou G., Chen C., Yu H., Wang T., Ma Y., Jia G., Gao Y., Li B., Sun J., Li Y., Jiao F., Zhao Y., Chai Z. Toxicol. Lett. 2007;168(2):176–185. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ze Y. G., Hu R. P., Wang X. C., Sang X. Z., Ze X., Li B., Su J. J., Wang Y., Guan N., Zhao X. Y., Gui S. X., Zhu L., Cheng Z., Cheng J., Sheng L., Sun Q. Q., Wang L., Hong F. S. J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part A. 2014;102(2):470–478. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz J., Hohenberg H., Pflucker F., Gartner E., Will T., Pfeiffer S., Wepf R., Wendel V., Gers-Barlag H., Wittern K. P. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2002;54:157–163. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pflucker F., Wendel V., Hohenberg H., Gartner E., Will T., Pfeiffer S., Wepf R., Gers-Barlag H. Skin Pharmacol. Appl. Skin Physiol. 2001;14:92–97. doi: 10.1159/000056396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamer A. O., Leibold E., van Ravenzwaay B. Toxicol. in Vitro. 2006;20:301–307. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadrieh N., Wokovich A. M., Gopee N. V., Zheng J., Haines D., Parmiter D., Siitonen P. H., Cozart C. R., Patri A. K., McNeil S. E. Toxicol. Sci. 2010;115:156–166. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman M. D., Stotland M., Ellis J. I. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2009;61:685–692. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennat C., Müller-Goymann C. C. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2000;22(4):271–283. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-2494.2000.00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouse J. G., Yang J., Ryman-Rasmussen J. P., Barron A. R., Monteiro-Riviere N. A. Nano Lett. 2007;7(1):155–160. doi: 10.1021/nl062464m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Dong X., Zhao J., Tang G. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2009;29:330–337. doi: 10.1002/jat.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabian E., Landsiedel R., Ma-Hock L., Wiench K., Wohlleben W., van Ravenzwaay B. Arch. Toxicol. 2008;82:151–157. doi: 10.1007/s00204-007-0253-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Z. J., Mortimer G., Schiller T., Musumeci A., Martin D., Minchin R. F. Nanotechnol. 2009;20:455101. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/20/45/455101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagens W. I., Oomen A. G., de Jong W. H., Cassee F. R., Sips A. J. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2007;49:217–229. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braydich-Stolle K., Schaeublin N. M., Murdock R. C., Jiang J., Biswas P., Schlager J. J., Hussain S. M. J. Nanopart. Res. 2009;11:1361–1374. [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Chen C., Liu Y., Jia F., Li W., Lao F., Lia Y., Li B., Ge C., Zhou G., Gao Y., Zhao Y. L., Chai Z. F. Toxicol. Lett. 2008;183:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita K., Yoshioka Y., Higashisaka K., Mimura K., Morishita Y., Nozaki M., Yoshida T., Ogura T., Nabeshi H., Nagano K., Abe Y., Kamada H., Monobe Y., Imazawa T., Aoshima H., Shishido K., Kawai Y., Mayumi T., Tsunoda S., Itoh N., Yoshikawa T., Yanagihara I., Saito S., Tsutsumi Y. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011;6:321–328. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda K., Suzuki K., Ishihara A., Kubo-Irie M., Fujimoto R., Tabota M., Oshio S., Nihei Y., Ihara T., Sugamata M. J. Health Sci. 2009;55:95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Möller W., Kreyling W. G., Schmid O., Semmler-Behnke M. and Schulz H., Deposition, Retention and Clearance, and Translocation of Inhaled Fine and Nano-Particles in the Respiratory Tract, in Particle-Lung Interactions, ed. P. Gehr, C. Mühlfeld, B. Rothen Rutishauser and F. Blank, Informa Healthcare, USA, New York, 2nd edn, 2009, ch. 5, pp. 79–107. [Google Scholar]

- Blank F., Rothen-Rutishauser B., Gehr P. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2007;36:669–677. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0234OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiser M., Casaulta M., Kupferschmid B., Schulz H., Semmler-Behnke M., Kreyling W. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2008;38:371–376. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0138OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO), Environmental Health Criteria 24- Titanium. In International Programme on Chemical Safety, World Health Organization, Geneva, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Huggins C. B., Froehlich J. P. J. Exp. Med. 1966;124:1099–1106. doi: 10.1084/jem.124.6.1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassian V. H., O'shaughnessy P. T., Adamcakova-Dodd A., Pettibone J. M., Thorne P. S. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007;115(3):397–402. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H. W., Su S. F., Chien C. T., Lin W. H., Yu S. L., Chou C. C., Chen Jeremy J. W., Yang P. C. FASEB J. 2006;20:1732–1741. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6485fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q. Q., Tan D. L., Ze Y. G., Sang X. Z., Liu X. R., Gui S. X., Cheng Z., Cheng J., Hu R. P., Gao G. D., Liu G., Zhu M., Zhao X. Y., Sheng L., Wang L., Tang M., Hong F. S. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012;235–236:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2012.05.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q. Q., Tan D. L., Zhou Q. P., Liu X. R., Cheng Z., Liu G., Zhu M., Sang X. Z., Gui S. X., Cheng J., Hu R. P., Tang M., Hong F. S. J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part A. 2012;100:2554–2562. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi E. M., Pylkkänen L., Koivisto A. J., Vippola M., Jensen K. A., Miettinen M., Sirola K., Nykäsenoja H., Karisola P., Stjernvall T., Vanhala E., Kiilunen M., Pasanen P., Mäkinen M., Hämeri K., Joutsensaari J., Tuomi T., Jokiniemi J., Wolff H., Savolainen K., Matikainen S., Alenius H. Toxicol. Sci. 2010;113(2):422–433. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson Å., Lindstedt E., Elfsmark L. S., Bucht A. J. Immunotoxicol. 2011;8(2):111–121. doi: 10.3109/1547691X.2010.546382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi F., Sadeghi L., Mohammadi A., Tanwir F., YousefiBabadi V., Izadnejad M. Bratisl. Lek. Listy. 2015;116(6):363–367. doi: 10.4149/bll_2015_069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L. L., Zhao J. F., Wang J., Duan Y. M., Liu J., Li N., Liu H. T., Yan J. Y., Ruan J., Hong F. S. Nanosacle Res. Lett. 2009;4:1275–1278. doi: 10.1007/s11671-009-9393-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Y. M., Liu J., Ma L. L., Li N., Liu H. T., Wang J., Zheng L., Liu C., Wang X. F., Zhang X. G., Yan J. Y., Wang H., Hong F. S. Biomaterials. 2010;31:894–899. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y. L., Gong X. L., Duan Y. M., Li N., Hu R. P., Liu H. T., Hong M. M., Zhou M., Wang L., Wang H., Hong F. S. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010;183:874–880. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.07.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y. L., Liu H. T., Zhou M., Duan Y. M., Li N., Gong X. L., Hu R. P., Hong M. M., Hong F. S. J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part A. 2011;96:221–229. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y. L., Liu H. T., Ze Y. G., Zhang Z. L., Hu Y. Y., Cheng Z., Hu R. P., Gao G. D., Cheng J., Gui S. X., Sang X. Z., Sun Q. Q., Wang L., Tang M., Hong F. S. Toxicol. Sci. 2012;128:171–185. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfs153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong J., Wang L., Zhao X. Y., Yu X. Y., Sheng L., Xu B. Q., Liu D., Zhu Y., Long Y., Hong F. S. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014;62(28):6871–6878. doi: 10.1021/jf501428w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alarifi S., Ali D., Al-Doaiss A. A., Ali B. A., Ahmed M., Al-Khedhairy A. A. Int. J. Nanomed. 2013;8:3937–3943. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S47174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tananova O. N., Arianova E. A., Gmoshinski I. V., Aksenov I. V., Zgoda V. G., Khoti-mchenko S. A., Vopr. Pitan., 2012, 812 , 18 –22 , . (in Russian) . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azim S. A., Darwish H. A., Rizk M. Z., Ali S. A., Kadry M. O. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 2015;67(4):305–314. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onishchenko G. E., Erokhina M. V., Abramchuk S. S., Shaitan K. V., Raspopov R. V., Smirnova V. V., Vasilevskaya L. S., Gmoshinski I. V., Kirpichnikov M. P., Tutelyan V. A. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2012;154(2):265–270. doi: 10.1007/s10517-012-1928-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Chen Z., Ba T., Pu J., Chen T., Song Y., Gu Y., Qian Q., Xu Y., Xiang K., Wang H., Jia G. Small. 2013;9(9–10):1742–1752. doi: 10.1002/smll.201201185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakeel M., Jabeen F., Qureshi A. N., Fakhr-e-Alam M. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2016;173(2):1–22. doi: 10.1007/s12011-016-0677-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramadan H., Mohamed H. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2015;83:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2015.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R., Niu Y., Li Y., Zhao C., Song B., Lia Y., Zhou Y. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2010;30(1):52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J. F., Wang J., Wang S. S., Zhao X. Y., Yan J. Y., Ruan J., Li N., Duan Y. M., Wang H., Hong F. S. J. Exp. Nanosci. 2010;5:447–462. [Google Scholar]

- Gui S. X., Zhang Z. L., Zheng L., Cui Y. L., Liu X. R., Li N., Sang X. Z., Sun Q. Q., Gao G. D., Cheng Z., Cheng J., Wang L., Tang M., Hong F. S. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011;195:365–370. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gui S. X., Li B. Y., Zhao X. Y., Sheng L., Hong J., Yu X. H., Sang X. Z., Sun Q. Q., Ze Y. G., Wang L., Hong F. S. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013;61(37):8959–8968. doi: 10.1021/jf402387e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang K. T., Wu C. T., Huang K. H., Lin W. C., Chen C. M., Guan S. S., Chiang C. K., Liu S. H. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2015;28(3):354–364. doi: 10.1021/tx500287f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong F. S., Hong J., Wang L., Zhou Y. J., Liu D., Xu B. Q., Yu X. H., Sheng L. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015;63(5):1639–1647. doi: 10.1021/jf5034834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong F. S., Wu N., Ge Y., Zhou Y. J., Shen T., Qiang Q., Zhang Q., Chen M., Wang Y., Wang L., Hong J. J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part A. 2016;104(6):1452–1461. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N., Duan Y. M., Hong M. M., Zheng L., Fei M., Zhao X. Y., Wang J., Cui Y. L., Liu H. T., Cai J. W., Gong S. J., Wang H., Hong F. S. Toxicol. Lett. 2010;195(2–3):161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.03.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Li N., Zheng L., Wang S. S., Wang Y., Zhao X. Y., Duan Y. M., Cui Y. L., Zhou M., Cai J. W., Gong S. J., Wang H., Hong F. S. Biol. Trace. Elem. Res. 2011;140(2):186–197. doi: 10.1007/s12011-010-8687-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang X. Z., Zheng L., Sun Q. Q., Li N., Cui Y. L., Hu R. P., Gao G. D., Cheng Z., Cheng J., Gui S. X., Liu H. T., Zhang Z., Hong F. S. J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part A. 2012;100(4):894–902. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang X. Z., Fei M., Sheng L., Zhao X. Y., Yu X. H., Hong J., Ze Y. G., Gui S. X., Sun Q. Q., Ze X., Wang L., Hong F. S. J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part A. 2014;102A:3562–3572. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng L., Wang L., Sang X. Z., Zhao X. Y., Hong J., Cheng S., Yu X. H., Liu D., Xu B. Q., Hu R. P., Sun Q. Q., Cheng J., Cheng Z., Gui S. X., Hong F. S. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014;278:180–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang X. Z., Li B., Ze Y. G., Hong J., Ze X., Gui S. X., Sun Q. Q., Liu H. T., Zhao X. Y., Sheng L., Liu D., Yu X. H., Wang L., Hong F. S. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013;61:5590–5599. doi: 10.1021/jf3035989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y., Zhang Y., Chang X., Zhang Y., Ma S., Sui J., Yin L., Pu Y., Liang G. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014;15(4):6961–6973. doi: 10.3390/ijms15046961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon E. Y., Yi G. H., Kang J. S., Lim J. S., Kim H. M., Pyo S. J. Immunotoxicol. 2011;8(1):56–67. doi: 10.3109/1547691X.2010.543995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson A., Jonasson S., Sandström T., Lorentzen J. C., Bucht A. Toxicol. 2014;326:74–85. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain S., Smulders S., De Vooght V., Ectors B., Boland S., Marano F., Van Landuyt K. L., Nemery B., Hoet P. H., Vanoirbeek J. A. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2012;9:15. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-9-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagisawa R., Takano H., Inoue K., Koike E., Kamachi T., Sadakane K., Ichinose T. Exp. Biol. Med. 2009;234(3):314–322. doi: 10.3181/0810-RM-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J. A., Lee E. J., Seo S. M., Kim H. S., Kang J. L., Park E. M. Neurosci. 2010;165:445–454. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]