Abstract

Purpose

Several tau PET tracers have been developed, but it remains unclear whether they bind to the same molecular target on the heterogeneous tau pathology. In this study we evaluated the binding of two chemically different tau-specific PET tracers (11C-THK5351 and 11C-PBB3) in a head-to-head, in vivo, multimodal design.

Methods

Nine patients with a diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment or probable Alzheimer’s disease and cerebrospinal fluid biomarker evidence supportive of the presence of Alzheimer’s disease brain pathology were recruited after thorough clinical assessment. All patients underwent imaging with the tau-specific PET tracers 11C-THK5351 and 11C-PBB3 on the same day, as well as imaging with the amyloid-beta-specific tracer 11C-AZD2184, a T1-MRI sequence, and neuropsychological assessment.

Results

The load and regional distribution of binding differed between 11C-THK5351 and 11C-PBB3 with no statistically significant regional correlations observed between the tracers. The binding pattern of 11C-PBB3, but not that of 11C-THK5351, in the temporal lobe resembled that of 11C-AZD2184, with strong correlations detected between 11C-PBB3 and 11C-AZD2184 in the temporal and occipital lobes. Global cognition correlated more closely with 11C-THK5351 than with 11C-PBB3 binding. Similarly, cerebrospinal fluid tau measures and entorhinal cortex thickness were more closely correlated with 11C-THK5351 than with 11C-PBB3 binding.

Conclusion

This research suggests different molecular targets for these tracers; while 11C-PBB3 appeared to preferentially bind to tau deposits with a close spatial relationship to amyloid-beta, the binding pattern of 11C-THK5351 fitted the expected distribution of tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease better and was more closely related to downstream disease markers.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00259-018-4012-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Tau, Neurofibrillary tangles, Amyloid-beta, Alzheimer’s disease, PET imaging, Neurodegeneration

Introduction

The aggregation of abnormally hyperphosphorylated tau protein in neurofibrillary tangles and the aggregation of amyloid-beta fibrils in extracellular plaques are the main neuropathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1]. In recent years, families of PET tracers that selectively target tau pathology have been developed, and many research groups have evaluated them in vivo. All tracers have favourable pharmacokinetics, show low binding in young healthy volunteers considered to be devoid of tau pathology and high binding in patients with AD, with a regional pattern strongly resembling the distribution of tau pathology as described by classical autopsy studies in the field [2–4].

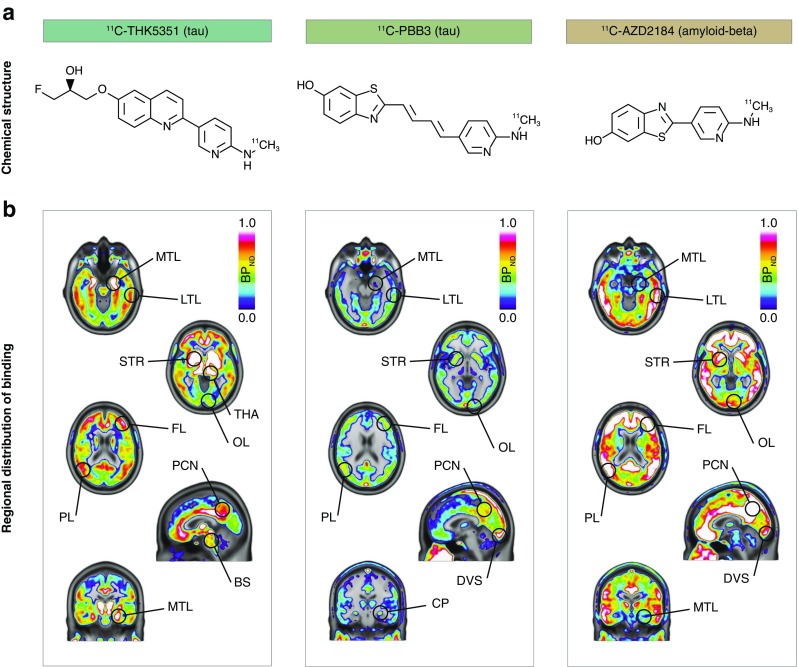

Despite the similar findings reported for all tau PET tracers in different cohorts, the distinct chemical structures of the tracers (Fig. 1a) call into question the similarity of their targets. Indeed, recent in vitro evidence highlights differences in the binding sites of tracers derived from different chemical families, when investigated in the same brain tissue [5, 6]. This should perhaps come as no surprise, since the existing body of research suggests that tau pathology offers a complex target for molecular imaging because of its heterogeneity in terms of tau isoforms affected, conformations adopted, maturation stages of the aggregates and cell types affected [7]. Therefore, although all the developed tracers are designed to target tau, it is likely that their specific targets on tau pathology are substantially different.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures (a) and average binding potential (BPND) images (b) of 11C-ΤΗΚ5351 (tau), 11C-PBB3 (tau) and 11C-AZD2184 (amyloid-beta) in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (prodromal or dementia; n = 9). The results presented were derived from data without correction for the partial volume effect. BS brainstem, CP choroid plexus, DVS dural venous sinus, FL frontal lobe, LTL lateral temporal lobe, MTL medial temporal lobe, OL occipital lobe, PCN precuneus, PL parietal lobe, STR striatum, THA thalamus

The relationships between tau tracer binding and other markers of AD have been assessed, to date, mainly in nonconsecutive studies. The results have indicated that the regional patterns of tau tracer binding are different from those of amyloid-beta tracers, although regional correlations exist [8–11]. Furthermore, the binding of all tau tracers is related to cognitive decline as well as regional neurodegeneration [8, 10–13]; this association becomes more obvious as neurodegeneration advances, as shown by the only longitudinal study [14]. However, since all these investigations were performed in individual cohorts using different tau tracers, it remains unclear whether the relationship between the tracers and the other markers of AD would be different when examined in a head-to-head design.

The aim of this multimodal study was to assess the binding properties of two chemically different tau-specific PET tracers (11C-THK5351 and 11C-PBB3) in vivo when injected into the same patients on the same day, and to examine their relationship with markers of amyloid-beta deposition, cognitive impairment and measures of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) tau and medial temporal atrophy.

Materials and methods

Study sample

Eleven patients were originally recruited to participate in a cross-sectional, multimodal, head-to-head, in vivo comparison study of the binding characteristics of the tau-specific PET tracers 11C-THK5351 and 11C-PBB3. All were recruited from the Memory Clinic of the Department of Geriatric Medicine, Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden, where they underwent thorough clinical investigation including medical history, physical examination, laboratory blood tests, apolipoprotein E genotyping, neuropsychological assessment, CSF sampling and structural imaging. The inclusion criteria for the study included objective evidence of cognitive impairment in the neuropsychological assessment and CSF biomarker findings supportive of the presence of AD pathological changes [15]. Seven of the eleven patients fulfilled clinically the Petersen criteria [16] for mild cognitive impairment, while four patients fulfilled the NINCDS-ADRDA [17] and DSM-IV criteria for dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. For the purposes of this study and based on the AD-consistent CSF profile, all patients with mild cognitive impairment were reclassified as having prodromal AD and all patients with AD as having AD dementia [15]. No non-AD-related pathology was detected on MRI in any of the patients, as evaluated by an experienced neuroradiologist at the Karolinska University Hospital. Two patients were excluded because of technical issues during the PET acquisitions.

Neuropsychological assessment

All participants completed a large battery of neuropsychological tests. The selection of tests was based on previous observations with tau PET imaging [13]. Premorbid cognitive function was assessed with the Swedish National Adult Reading Test (irregularly spelled words; ISW) [18], while current global cognitive function was assessed with the Full Scale Intelligence Quotient (FSIQ), which is based on five subtests from the Weschler Adult Intelligence Scale (Similarities, Information, Block design, Digit span, and Digit symbol) [19]. A summary z-score, based on a reference group of healthy controls, was calculated to describe each individual’s cognitive decline from the estimated premorbid cognitive function (decline in FSIQ: premorbid cognitive function, ISW, minus current FSIQ) [20, 21]. Episodic memory performance was assessed using the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure (ROCF) delayed recall test, after z-score transformation using a reference group of healthy controls [21]. One patient did not complete the ROCF delayed recall test. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score was used as a clinical measure of global cognition.

Image acquisition

11C-THK5351 and 11C-PBB3 PET measurements were planned for all participants on the same day (median 0 [quartile 1:quartile 3 0:2] days) for imaging tau pathology. An 11C-AZD2184 dynamic PET measurement was planned within 2 weeks (3 [3:9] days) for imaging amyloid-beta deposition. A three-dimensional, T1-weighted MRI sequence was performed after a median of 9 [6:67] days to assess medial temporal atrophy.

The 11C-THK5351, 11C-PBB3 and 11C-AZD2184 PET measurements were acquired on a high-resolution research tomograph (HRRT; CTI/Siemens, Knoxville, TN, USA) in list mode, at the Centre for Psychiatric Research, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden. All tracers were synthesized according to standard good manufacturing practice, as described previously [22–24]. The tracer THK5351, although originally developed as an 18F tracer, was labelled with 11C for the purposes of this project, to allow multitracer imaging on the same day as the 11C-PBB3 acquisitions. An individual plaster helmet was made for each participant prior to PET, and was used to minimize head movement during the PET acquisition. For 11C-THK5351, 38 frames were acquired over 93 min, and for 11C-PBB3 and 11C-AZD2184, 33 frames were acquired over 63 min, starting simultaneously with intravenous injection of 350 [322:414] MBq, 343 [300:420] MBq and 308 [295:347] MBq, respectively. The injected mass for each tracer was similar: 0.40 [0.35:0.52] μg, 0.33 [0.20:0.60] μg and 0.20 [0.17:0.44] μg, respectively. A longer acquisition time was used for THK5351 since this was the first in vivo evaluation of the tracer when labelled with 11C. The radiosynthesis and injection of 11C-PBB3 were carried out without fluorescent lighting to avoid photoisomerization of the tracer [23]. All acquisitions were reconstructed using ordered-subsets expectation maximization.

Three-dimensional, sagittal magnetization-prepared, rapid gradient-echo, T1-weighted MRI sequences were acquired on a 1.5-T Siemens MAGNETOM Avanto imaging system (Siemens AG, Muenchen, Germany) at Praktikertjänst Röntgen Odenplan, Stockholm, Sweden. The parameters applied were as follows: repetition time/echo time/inversion time 1,790/3.53/1,100 ms, field of view 256 × 256 mm, acquisition matrix 256 × 208 mm, flip angle 15°, and slice thickness 1 mm. Full brain and skull coverage was required for the MRI datasets and detailed quality control was carried out on all images according to previously published criteria [25].

Regions of interest for PET quantification

All individual T1-weighted MRI images were first segmented into six tissue classes (grey matter, white matter, CSF, bone, soft tissue, and air/background) using SPM12 [26]. The inverse nonlinear transformation matrix was used to spatially wrap the anatomical automatic labelling atlas [27] to the individual’s native MRI space. Application of the individual grey matter masks resulted in individual grey matter regions of interest (ROIs). The choice of ROIs for quantifying tracer binding was based on the findings of previously published tau PET imaging studies [8, 11]; the hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus, fusiform gyrus, inferior temporal gyrus, and medial and lateral occipital lobes (Online Resource 1), and the composite ROIs temporal, frontal, parietal and occipital cortices were selected.

PET image preprocessing

The individual grey matter ROIs were applied to the dynamic 11C-THK5351, 11C-PBB3 and 11C-AZD2184 images in the native PET space, through an intermediate MRI to PET coregistration step using SPM12, to preserve the high resolution of the PET data. Voxel-based kinetic modelling for all tracers was applied with the wavelet-aided parametric imaging method [28] to obtain high resolution, noise-robust nondisplaceable binding potential (BPND) images over the following measurement intervals: 8–93 min for 11C-THK5351, 8–63 min for 11C-PBB3 and 45–63 min for 11C-AZD2184. The cerebellar cortex was used as the reference region for quantifying the binding of all tracers, a region that has been previously validated against using arterial input function data for both THK5351 and PBB3 [29, 30]. A BPND isocortical threshold of 0.40 for amyloid-beta positivity was applied to the 11C-AZD2184 PET data [31, 32].

THK5351 has no known brain-penetrating metabolites [33] that would affect quantification of the tracer’s binding, but this is not the case for PBB3, which shows such a radiometabolite [23, 34]. Interestingly, however, it has been shown that PBB3 binding can be accurately quantified with simplified reference models, despite the presence of the metabolite, as illustrated using arterial sampling to obtain the parent and metabolite input functions [30]. It is worth noting, however, that in no case can we rule out the possibility that the signal from the radiolabelled PBB3 metabolite is contributing to a certain low degree to the total signal quantified by kinetic models not employing arterial data. In our study, in order validate the voxel-based quantification of 11C-THK5351 and 11C-PBB3, we carried out region-based kinetic modelling using the reference Logan graphical method [35] and the original multilinear reference tissue model [36] (Online Resource 2), respectively, as proposed previously for each tracer [29, 30, 37].

In order to validate the quantification of tracer binding used in the present work, the dynamic PET data were also corrected for the partial volume effect (PVE) using the geometric transfer matrix method (data are shown in Online Resource 3) [38]. The results presented here in the main body of the text including all main figures were derived from PVE-uncorrected data.

Cortical thickness measurements

FreeSurfer image processing software, version 6.0 (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu) was used to measure the cortical thickness on T1-weighted MRI images. Cortical reconstruction was performed as described in detail elsewhere [39]. Quality control of the output was carried out. The thickness of the entorhinal cortex was selected in this study as a measure of medial temporal atrophy, based on previous findings with another tau PET tracer [40] showing that entorhinal thickness rather than hippocampal volumes is more closely related to local tau PET tracer binding.

Cerebrospinal fluid measurements

CSF samples were obtained via lumbar puncture from all patients, under nonfasting conditions, as part of routine memory assessment. Levels of amyloid-beta (Aβ1–42), total tau (t-tau), and phosphorylated tau181p (p-tau181p) were determined using commercially available sandwich ELISAs (Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium) at the Clinical Neurochemistry Laboratory, Gothenburg University, Mölndal, Sweden. The Aβ1–42, t-tau and p-tau181p reference values used to determine AD-consistent abnormalities in the clinical assessment of the patients were <550 pg/mL, >400 pg/mL and >80 pg/mL, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as number or medians [quartile 1:quartile 3]. Correlations between modalities were analysed using the nonparametric Spearman coefficient. The associations between the tracers in terms of local binding were investigated in the four main lobes and the four temporal ROIs. Associations between tracer binding and age, CSF tau measures, decline in FSIQ and ROCF delayed recall were examined in the temporal ROIs. Associations between entorhinal cortex thickness and local tracer binding were also investigated; the tracer binding was evaluated in the parahippocampal gyrus, since in the atlas used to sample the PET data the entorhinal cortex was included in the parahippocampal gyrus ROI [27]. The association between tracer binding and MMSE results was examined in relation to binding in the four main lobes because of the gross nature of MMSE. The cut-off for statistical significance was p < 0.05 (two-tailed). All analyses were carried out using R software, version 3.4.0 (https://www.R-project.org/).

Results

The characteristics of the study sample are summarized in Table 1. The patients were relatively young (65 [61:70] years), mildly cognitively impaired (MMSE score 27 [25:28]), apolipoprotein E ε4 carriers and amyloid-beta positive based on their 11C-AZD2184 PET measurement (isocortical binding 0.91 [0.88:0.95] BPND, cut-off for amyloid-beta positivity 0.40 BPND; for more information see the section PET image preprocessing).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Number of participants | 9 |

| Gender (M/F) | 4/5 |

| Age (years) | 65 [61:70] |

| Education (years) | 12 [12:13] |

| Clinical diagnosis | |

| Prodromal AD | 5 |

| AD dementia | 4 |

| APOE carriers | |

| ε3/ε4 | 5 |

| ε4/ε4 | 4 |

| Cognitive performance | |

| MMSE score | 27 [25:28] |

| Decline in FSIQ based on ISW (z-scores)a | −2.04 [−0.97:−2.16] |

| ROCF delayed recall (z-scores)a | −1.45 [−1.15:−2.09]c |

| CSF biomarkersb | |

| Aβ1–42 (pg/mL) | 477 [380:539] |

| Total tau (pg/mL) | 548 [450:897] |

| Phosphorylated tau181 (pg/mL) | 66 [57:94] |

Data are presented as medians [quartile 1:quartile 3] or as number

Aβ amyloid-beta, AD Alzheimer’s disease, APOE apolipoprotein E, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, FSIQ Full-Scale Intelligence Quotient, ISW Irregularly Spelled Words test, ROCF Rey-Osterrieth complex figure test

aDecline in FSIQ based on ISW and performance in the ROCF delayed recall test are expressed as z-scores in comparison with a reference group of healthy controls [21]

bThe local reference values for Aβ1–42, total tau, and phosphorylated tau181p used to determine abnormalities in the clinical assessment of the patients were <550 pg/mL, >400 pg/mL, and >80 pg/mL, respectively

cOne patient did not complete the ROCF delayed recall test

Load and regional distribution of tracer binding

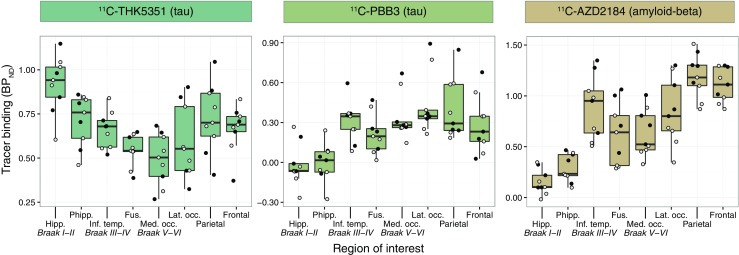

Binding of the tau-specific tracers 11C-THK5351 and 11C-PBB3 was observed in the temporal lobes and other isocortical areas (Fig. 1b). 11C-THK5351 showed substantially higher grey matter binding than 11C-PBB3. Both tracers showed very low white matter binding. Regional differences in the binding patterns of the two tracers were observed, especially in the temporal lobes. 11C-THK5351 binding was higher in the medial than in the lateral temporal lobe, while the opposite pattern was observed for 11C-PBB3. Briefly, the highest cortical 11C-THK5351 binding was detected in the hippocampus (allocortex), while lower binding was detected in the inferior temporal gyrus, and the lowest cortical binding of the tracer was observed in the medial areas of the occipital lobe (Fig. 2). In contrast, 11C-PBB3 showed minimal binding in the hippocampus, and the highest binding in the temporal lobe was seen in the inferior temporal gyrus. The lack of binding of 11C-PBB3 in the hippocampus, in contrast to the extensive binding in the adjacent choroid plexus, could be better appreciated on high-resolution PET imaging data (Online Resource 4). 11C-THK5351 showed off-target binding in the thalamus and brain stem and 11C-PBB3 showed off-target binding in the dural venous sinuses and choroid plexus. Both tracers showed high binding in the striatum, cingulate gyri and precuneus, although this binding was substantially greater for 11C-THK5351. PVE correction of tracer binding resulted in higher BPND values across ROIs for both tracers, although the regional distribution pattern was essentially the same (Online Resource 3).

Fig. 2.

Boxplots illustrating the regional quantification of the binding of 11C-ΤΗΚ5351 (tau), 11C-PBB3 (tau) and 11C-AZD2184 (amyloid-beta) in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (prodromal or dementia; n = 9). The results presented were derived from data without correction for the partial volume effect. Open circles patients with prodromal Alzheimer’s disease, closed circles patients with Alzheimer’s disease dementia; horizontal lines median values, lower and upper hinges first and third quartiles, whiskers range of values excluding potential outliers. Braak I-VI regions of interest roughly matching the neuropathological Braak staging system for neurofibrillary tangle pathology for demonstration purposes only [53], Fus. fusiform gyrus, Hipp. hippocampus, Inf. temp. inferior temporal gyrus, Lat. occ. lateral occipital cortex, Med. occ. medial occipital cortex, Phipp. parahippocampal gyrus

Online Resource 5 shows the time–activity curves for 11C-THK5351 and 11C-PBB3 in the participating patients. Both were rapidly taken up by the brain, although uptake of 11C-THK5351 was greater and the overall kinetics were faster over the measurement interval compared with 11C-PBB3.

In all patients, isocortical binding of the amyloid-beta-specific tracer 11C-AZD2184 was widespread, with a binding distribution pattern that was largely distinct from those of 11C-THK5351 and 11C-PBB3. Interestingly, however, the binding pattern of 11C-AZD2184 in the temporal lobe resembled that of 11C-PBB3; binding was higher in the lateral temporal lobe than in the medial areas (Figs. 1b and 2). Off-target binding of 11C-AZD2184 was observed in the dural venous sinuses.

Association between tracers with respect to binding

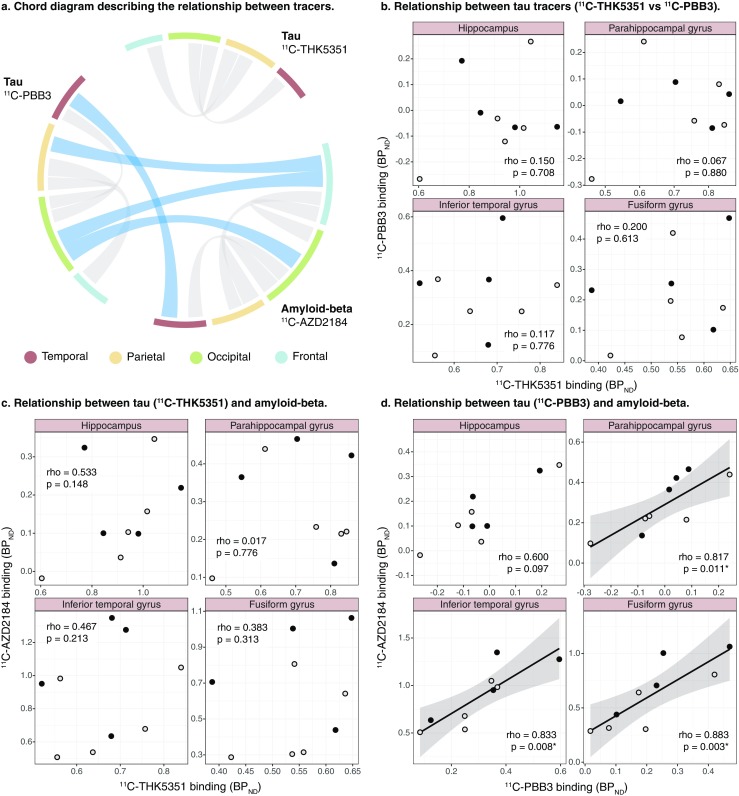

Intriguingly, there were no correlations between 11C-THK5351 and 11C-PBB3 with respect to binding in the four main lobes or the temporal ROIs (Fig. 3a, b).

Fig. 3.

Chord diagram (a) and scatterplots (b–d) showing the relationships between the binding (BPND) of the tau tracers 11C-ΤΗΚ5351 and 11C-PBB3, and the amyloid-beta tracer 11C-AZD2184. The results presented were derived from data without correction for the partial volume effect. The weight of the strings in the chord diagram represents the strength of the statistically significant Spearman’s regional correlations within or between tracers (grey and blue strings, respectively). Open circles patients with prodromal Alzheimer’s disease, closed circles patients with Alzheimer’s disease dementia (rho Spearman’s rho). *p < 0.05

There were no correlations between 11C-THK5351 and 11C-AZD2184 binding across all ROIs (Fig. 3a, c). In contrast, the local binding of 11C-PBB3 and of 11C-AZD2184 correlated positively in the temporal and occipital lobes (rho = 0.750, p = 0.020, and rho = 0.817, p = 0.007, respectively; Fig. 3a). In more detail, 11C-PBB3 and 11C-AZD2184 binding correlated strongly in all temporal sub-ROIs examined, except the hippocampus in which a trend was observed (Fig. 3d).

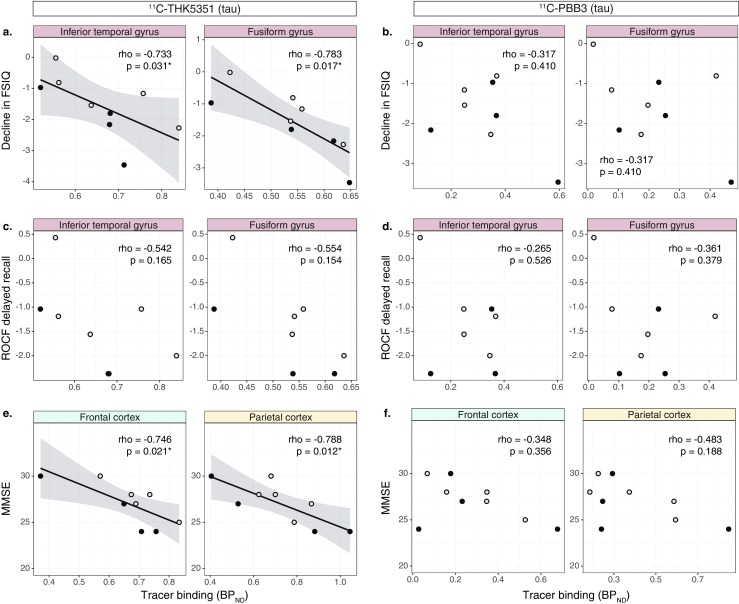

Association between tau tracer binding and cognitive performance

11C-THK5351 binding in the inferior temporal and fusiform gyri correlated negatively with decline in FSIQ (Fig. 4a). 11C-THK5351 binding showed a moderate correlation with ROCF delayed recall, although the association did not reach statistical significance (rho = −0.542 to −0.602, p = 0.114–0.165; Fig. 4c). No statistically significant correlation was detected between 11C-PBB3 binding and decline in FSIQ (Fig. 4b) or ROCF delayed recall test scores (rho = −0.133 to −0.361, p = 0.379–0.754; Fig. 4d). 11C-THK5351 binding in the frontal and parietal lobes correlated negatively with MMSE score (Fig. 4e). 11C-PBB3 binding was also negatively correlated with MMSE score, although the outlier profile of a single patient resulted in a statistically nonsignificant correlation between the two (Fig. 4f). The outlier patient (AD dementia, MMSE score 24) had the poorest education (8 years) of the study sample and clear discordance in the binding of the two tau-specific tracers. The exclusion of this patient resulted in statistically significant negative correlations between 11C-PBB3 binding and MMSE score in the frontal, parietal and occipital lobes (n = 8, rho = −0.740 to −0.837, p = 0.010–0.036).

Fig. 4.

Scatterplots showing the relationships between the binding (BPND) of the tau tracers (11C-ΤΗΚ5351 and 11C-PBB3) and the decline in FSIQ (global cognition; a, b), ROCF delayed recall (episodic memory; c, d) and MMSE (global cognition; e, f). The declines in FSIQ and ROCF delayed recall are expressed as z-scores from comparison with a reference group of healthy controls [21]. The results presented were derived from data without correction for the partial volume effect. Open circles patients with prodromal Alzheimer’s disease, closed circles patients with Alzheimer’s disease dementia (rho Spearman’s rho). *p < 0.05

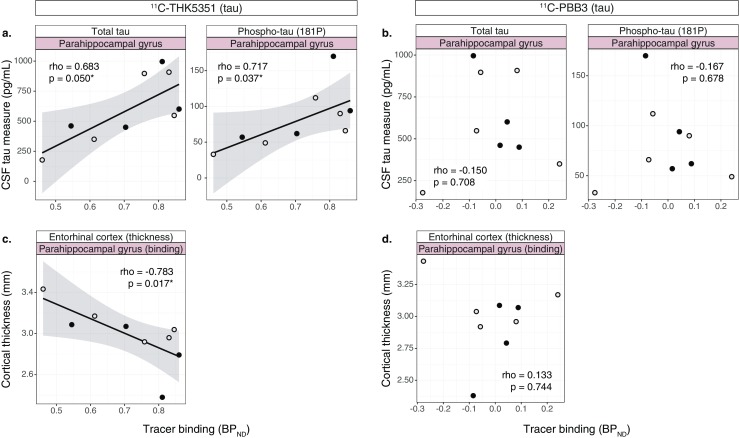

Association between tau tracer binding and other markers of disease

11C-THK5351 binding in the parahippocampal gyrus was significantly positively correlated with CSF tau levels (t-tau and p-tau181p; Fig. 5a); the correlation was not significant in the other temporal ROIs examined except for a trend for a significant correlation between 11C-THK5351 binding and p-tau181p in the inferior temporal gyrus (rho = 0.617, p = 0.086). In contrast, there were no significant correlations between 11C-PBB3 binding and CSF tau levels (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 5.

Scatterplots showing the relationships between the binding (BPND) of the tau tracers (11C-ΤΗΚ5351 and 11C-PBB3) and CSF tau measures (a, b), and entorhinal cortex thickness (c, d). The results presented were derived from data without correction for the partial volume effect. Open circles patients with prodromal Alzheimer’s disease, closed circles patients with Alzheimer’s disease dementia (rho Spearman’s rho). *p < 0.05

11C-THK5351 binding in the parahippocampal gyrus correlated negatively with entorhinal cortex thickness (rho = −0.783, p = 0.017), but there was no correlation between 11C-PBB3 binding and cortical thickness in the same ROI (Fig. 5c, d).

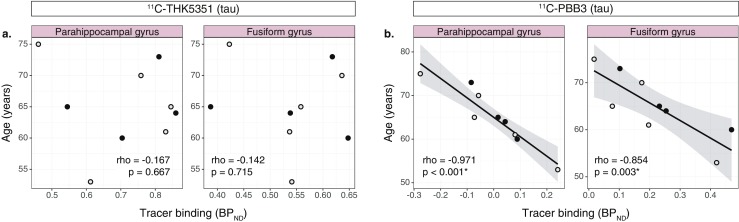

Association between tau tracer binding and age

There were strong negative correlations between 11C-PBB3 binding and age in all temporal ROIs examined (rho = −0.812 to −0.971, p < 0.01; Fig. 6b). No correlations were detected between 11C-THK5351 binding and age in the temporal ROIs examined (Fig. 6a).

Fig. 6.

Scatterplots showing the relationships between the binding (BPND) of the tau tracers (11C-ΤΗΚ5351 and 11C-PBB3) and age (a, b). The results presented were derived from data without correction for the partial volume effect. Open circles patients with prodromal Alzheimer’s disease, closed circles patients with Alzheimer’s disease dementia (rho Spearman’s rho). *p < 0.05

Discussion

The aim of this study was to compare two tau-specific PET tracers in vivo. 11C labelling of both tracers allowed their injection into the same patients with AD (prodromal or dementia) on the same day. The two tracers (11C-THK5351 and 11C-PBB3) differed in both load and regional distribution pattern of binding in the AD brain. Moreover, they displayed different patterns of associations with other markers of the disease, including markers of amyloid-beta deposition, cognitive impairment, CSF tau and medial temporal atrophy.

Distinctive binding properties of the tau-specific tracers

11C-THK5351 showed overall substantially higher binding than 11C-PBB3, in agreement with in vitro autoradiography observations [6]. While the regional distribution of 11C-THK5351 closely matched the classical distribution pattern of tau pathology [3, 4], the same did not apply for 11C-PBB3. 11C-PBB3 bound only minimally in the medial temporal lobe, an area known for its abundance of tau pathology early in the AD trajectory. It was somewhat surprising that there was no relationship between the binding of 11C-THK5351 and 11C-PBB3 either in the temporal lobe or across the whole cortex. While the sample was small and thus only strong relationships between modalities could be detected, the scatterplots indicated a lack of relationship between the two. Altogether, the differences in regional distribution and the lack of correlation between 11C-THK5351 and 11C-PBB3 binding indicate differences in the molecular targets of the tracers. This may be a result of their different chemical structures and is in agreement with findings of in vitro studies that directly compared the binding characteristics of the three most prominent tau-specific tracers (THK5351, AV-1451 and PBB3) and showed distinct binding sites for the tracers [5, 6]. Nevertheless, the complexity of tau pathology, in terms of the isoforms affected (three and four repeat tau), conformations adopted (paired helical, straight and twisted tau filaments) and types of deposits formed (e.g. neurofibrillary tangles, neuritic plaques, neuropil threads, glial tau deposits), does not preclude the possibility that both 11C-THK5351 and 11C-PBB3 bind to tau – although to different specific targets, as indicated previously by in vitro results [6].

Differential relationship with amyloid-beta

The similarities between 11C-PBB3 and 11C-AZD2184 in terms of regional distribution, especially in the temporal lobe, as well as the very strong regional correlations in tracer binding could potentially raise the question as to the molecular target of 11C-PBB3. Furthermore, the facts that 11C-PBB3 and 11C-AZD2184 have similar chemical structures, although the linker domains differ in length, and have common off-target signals in the dural venous sinuses, add to this uncertainty. Similarities in the molecular targets of 11C-PBB3 and 11C-AZD2184 indicate limited specificity of 11C-PBB3 for tau and a potential binding affinity of the tracer for the more abundant (in the AD brain) amyloid-beta. However, early in vitro evidence to date excludes this possibility [9], although more detailed in vitro competition studies are lacking for further validating the tracer specificity. Additionally, an earlier study that focused on a generally older, more severely affected sample of patients did not show a relationship between 11C-PBB3 binding and amyloid-beta burden globally, indicating that the latter relationship could occur only in the early stages of the disease or in distinct brain regions [10]. Indeed, in our study, the regional correlations between 11C-PBB3 and 11C-AZD2184 binding were limited to the temporal and occipital lobes. The latter areas are well known as the richest areas for neuritic plaques [41] (i.e. dense-core amyloid-beta plaques surrounded by tau-rich dystrophic neurites [42]) in the AD brain. Based on this evidence, it is conceivable that 11C-PBB3 binds preferentially to tau deposits located in close proximity to the abundant amyloid-beta plaques in the early symptomatic stages of AD examined in this study, while 11C-THK5351 appears to bind to a wider range of tau deposits [43], based on the regional distribution of the tracer. This hypothesis, however, remains to be proven with thorough ante-/post-mortem investigations.

Differential relationships with cognitive performance and other disease markers

A substantial overlap was observed in terms of 11C-THK5351 and 11C-PBB3 binding between prodromal and dementia stage AD, although the more detailed neuropsychological evaluation that was employed highlighted that the tracers were able to track the underlying cognitive impairment. More specifically, both tau tracers were similarly correlated with MMSE score, as found in previous studies [10, 13, 44], although this did not apply to a more sensitive measure of global cognition: 11C-THK5351 was more sensitive to declines in FSIQ than 11C-PBB3. This is consistent with evidence suggesting that 11C-THK5351 binding detects tau deposits that are more closely related to atrophy, consistent with post-mortem observations linking tau pathology to neurodegeneration [45, 46]. Furthermore, the rather close relationship between 11C-THK5351, but not 11C-PBB3, binding and CSF tau levels, similarly to evidence for another tau tracer (18F-AV-1451) [47], suggests that the 11C-THK5351 molecular target is more closely related to the soluble tau in CSF than to the tau target of 11C-PBB3.

Age-dependent binding

The strong negative relationship between age and 11C-PBB3 binding in the temporal lobe was unexpected in our study, especially because of the limited sample size and the narrow age range of the participants. Exploring the age effect was not one of the aims of this study, but was rather an observation while investigating covariates that could potentially have affected the analyses of correlations with cognitive or atrophy measures. Therefore, this finding should be interpreted with caution and its relevance requires further investigation in a larger sample.

Tracer characteristics and off-target binding

Recent evidence indicates off-target binding of THK5351 and AV-1451 to monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) [6, 48–50]. In line with the findings of these studies, we observed increased binding of 11C-THK5351 in MAO-B-rich areas (striatum, thalamus, cingulate gyri) [51]. Interestingly, however, extensive binding of 11C-PBB3 was also observed in the same areas (i.e. striatum and cingulate gyri, but not thalamus). The low tau pathology levels in the striatum and cingulate gyri together with the abundance of MAO-B in the same areas [3, 4, 51] suggest that the three most prominent tau-specific tracers (THK5351, AV-1451 and PBB3) [52], although chemically different, may show some affinity for MAO-B, which could explain their in vivo off-target binding. Further work is required to investigate the contribution of MAO-B binding to the off-target signal of the existing tau tracers, to determine which ROIs are more heavily affected by this off-target signal, and to examine whether structural similarities between tau fibrils and MAO-B are responsible for the observed interaction of the tracers with MAO-B.

The off-target signal of 11C-PBB3 in vascular structures (i.e. choroid plexus and dural venous sinuses) could have important implications for quantifying tracer binding. The high binding of 11C-PBB3 in the hippocampus that has previously been reported in images from conventional, relatively low-resolution PET systems [9] can now be attributed to spill-over from the intense 11C-PBB3 signal in the adjacent choroid plexus. Moreover, the high off-target signal of 11C-PBB3 from the dural venous sinuses could complicate the quantification of the tracer because of spill-over of signal from ROIs in close proximity to the sinuses, such as large portions of the parietal, occipital and cerebellar cortices. As an example, the use of the cerebellar cortex (affected by spill-over) as a reference region for 11C-PBB3 could prove problematic and lead to underestimation of tracer binding and even negative binding values, especially in ROIs with relatively poor binding. The recognition of off-target binding of the existing tracers and the complications that this binding could cause for quantification of tracer binding is of particular interest as the tracers are employed in ever larger cohorts.

Limitations

Although the homogeneous sample of patients with AD (prodromal or dementia) in this study was adequate in terms of size with respect to the main aim, the head-to-head comparison of the binding properties of the two tau-specific tracers, it limits the generalizability of the findings when describing the relationships with different biomarkers. Therefore, although we can reach conclusions about differential relationships between the tracers and the different markers of the disease, we cannot exclude the possibility that the relationships that did not reach the threshold for statistical significance were not substantial. More specifically, this study was not designed to refute evidence found in earlier studies, which used larger sample sizes and therefore had greater power to investigate the exact strength of the relationships between the binding of the tracers and the different markers of the disease. In those studies, moderate correlations were found between (a) binding of tracers of the THK family and local amyloid-beta deposition in selected regions, (b) binding of 11C-PBB3 and whole-brain grey matter atrophy, and (c) binding of both families of tracers with measures of episodic memory [10, 11, 13, 44]. Lastly, an important limitation of this study lies in the characteristics of the study sample – all participants were relatively young, apolipoprotein E ε4 carriers and had a clear AD-consistent CSF profile – which could limit substantially the generalizability of our findings in the diverse population of patients undergoing cognitive assessment in the clinical setting.

Conclusion

The load and regional distribution of 11C-THK5351 and 11C-PBB3 binding suggest different molecular targets for the two tracers, with no similarities observed between them, apart from the common off-target signal from MAO-B-rich areas. The 11C-THK5351 pattern fitted best with the expected distribution of tau pathology in AD and related more closely to markers of CSF tau, medial temporal atrophy and cognitive impairment. In contrast, and based on the strong relationships with the amyloid-beta tracer, we suggest that 11C-PBB3 could, in the early symptomatic stages of AD, show preferential binding to tau deposits spatially related to amyloid-beta, which could explain its limited association with more downstream markers of the disease (i.e. neurodegeneration and cognitive impairment).

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 3710 kb)

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and their relatives for making this study possible.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Swedish Research Council (project 05817), the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research (SSF), the Regional Agreement on Medical Training and Clinical Research (ALF) for Stockholm County Council, the Old Servants Foundation, the Sigurd and Elsa Goljes Memorial, the Axel Linder Foundation, the Gun and Bertil Stohne Foundation, the KI Funds, the Swedish Brain Fund, the Swedish Alzheimer’s Foundation (Alzheimerfonden), the Dementia Foundation (demensfonden), the KTH-SLL grants and the EU FW7 large-scale integrating project INMiND (http://www.uni-muenster.de/INMiND).

Conflicts of interest

H.S. and M.H. hold a patent on the PET tracer PBB3, which was used in the study reported here (JP 5422782/EP 12 884 742.3). N.O. receives royalties from GE Healthcare Corp. for the PET tracer THK5351, which was used in the study reported here.

All other authors declare no conflicts on interest.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm, Sweden, and by the Medical Products Agency in Sweden (Läkemedelsverket; EudraCT: 2015–005506-11). The use of all tracers was approved by the Radiation Safety Committee at the Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden, and all procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the principles of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments, or comparable ethical standards, as well as with those of the International Conference on Harmonisation/Good Clinical Practice guidelines.

Informed consent

All participants and their caregivers provided written informed consent prior to the investigation

References

- 1.Hyman BT, Phelps CH, Beach TG, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, Carrillo MC, et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saint-Aubert L, Lemoine L, Chiotis K, Leuzy A, Rodriguez-Vieitez E, Nordberg A. Tau PET imaging: present and future directions. Mol Neurodegener. 2017;12:19. doi: 10.1186/s13024-017-0162-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delacourte A, David JP, Sergeant N, Buee L, Wattez A, Vermersch P, et al. The biochemical pathway of neurofibrillary degeneration in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1999;52:1158–1165. doi: 10.1212/WNL.52.6.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ono M, Sahara N, Kumata K, Ji B, Ni R, Koga S, et al. Distinct binding of PET ligands PBB3 and AV-1451 to tau fibril strains in neurodegenerative tauopathies. Brain. 2017;140:764–780. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lemoine L, Gillberg PG, Svedberg M, Stepanov V, Jia Z, Huang J, et al. Comparative binding properties of the tau PET tracers THK5117, THK5351, PBB3, and T807 in postmortem Alzheimer brains. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2017;9:96. doi: 10.1186/s13195-017-0325-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Villemagne VL, Fodero-Tavoletti MT, Masters CL, Rowe CC. Tau imaging: early progress and future directions. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:114–124. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70252-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson KA, Schultz A, Betensky RA, Becker JA, Sepulcre J, Rentz D, et al. Tau positron emission tomographic imaging in aging and early Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2016;79:110–119. doi: 10.1002/ana.24546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maruyama M, Shimada H, Suhara T, Shinotoh H, Ji B, Maeda J, et al. Imaging of tau pathology in a tauopathy mouse model and in Alzheimer patients compared to normal controls. Neuron. 2013;79:1094–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shimada H, Kitamura S, Shinotoh H, Endo H, Niwa F, Hirano S, et al. Association between Abeta and tau accumulations and their influence on clinical features in aging and Alzheimer’s disease spectrum brains: a [11C]PBB3-PET study. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;6:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2016.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiotis K, Saint-Aubert L, Savitcheva I, Jelic V, Andersen P, Jonasson M, et al. Imaging in-vivo tau pathology in Alzheimer’s disease with THK5317 PET in a multimodal paradigm. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43:1686–1699. doi: 10.1007/s00259-016-3363-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ossenkoppele R, Schonhaut DR, Scholl M, Lockhart SN, Ayakta N, Baker SL, et al. Tau PET patterns mirror clinical and neuroanatomical variability in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2016;139:1551–1567. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saint-Aubert L, Almkvist O, Chiotis K, Almeida R, Wall A, Nordberg A. Regional tau deposition measured by [18F]THK5317 positron emission tomography is associated to cognition via glucose metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2016;8:38. doi: 10.1186/s13195-016-0204-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiotis K, Saint-Aubert L, Rodriguez-Vieitez E, Leuzy A, Almkvist O, Savitcheva I, et al. Longitudinal changes of tau PET imaging in relation to hypometabolism in prodromal and Alzheimer’s disease dementia. Mol Psychiatry. 2017 doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, Hampel H, Molinuevo JL, Blennow K, et al. Advancing research diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease: the IWG-2 criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:614–629. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:303–308. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA work group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/WNL.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tallberg IM, Wenneborg K, Almkvist O. Reading words with irregular decoding rules: a test of premorbid cognitive function? Scand J Psychol. 2006;47:531–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2006.00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wechsler D. WAIS-R manual: Wechsler adult intelligence scale-revised. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Almkvist O, Tallberg IM. Cognitive decline from estimated premorbid status predicts neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychology. 2009;23:117–124. doi: 10.1037/a0014074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bergman I, Blomberg M, Almkvist O. The importance of impaired physical health and age in normal cognitive aging. Scand J Psychol. 2007;48:115–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2007.00594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stepanov V, Svedberg M, Jia Z, Krasikova R, Lemoine L, Okamura N, et al. Development of [11C]/[3H]THK-5351 – a potential novel carbon-11 tau imaging PET radioligand. Nucl Med Biol. 2017;46:50–53. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hashimoto H, Kawamura K, Igarashi N, Takei M, Fujishiro T, Aihara Y, et al. Radiosynthesis, photoisomerization, biodistribution, and metabolite analysis of 11C-PBB3 as a clinically useful PET probe for imaging of tau pathology. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:1532–1538. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.139550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andersson JD, Varnas K, Cselenyi Z, Gulyas B, Wensbo D, Finnema SJ, et al. Radiosynthesis of the candidate beta-amyloid radioligand [(11)C]AZD2184: positron emission tomography examination and metabolite analysis in cynomolgus monkeys. Synapse. 2010;64:733–741. doi: 10.1002/syn.20782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simmons A, Westman E, Muehlboeck S, Mecocci P, Vellas B, Tsolaki M, et al. MRI measures of Alzheimer’s disease and the AddNeuroMed study. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1180:47–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ashburner J, Friston KJ. Unified segmentation. Neuroimage. 2005;26:839–851. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N, et al. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. Neuroimage. 2002;15:273–289. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cselenyi Z, Olsson H, Farde L, Gulyas B. Wavelet-aided parametric mapping of cerebral dopamine D2 receptors using the high affinity PET radioligand [11C]FLB 457. Neuroimage. 2002;17:47–60. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jonasson M, Wall A, Chiotis K, Saint-Aubert L, Wilking H, Sprycha M, et al. Tracer kinetic analysis of (S)-18F-THK5117 as a PET tracer for assessing tau pathology. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:574–581. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.158519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kimura Y, Ichise M, Ito H, Shimada H, Ikoma Y, Seki C, et al. PET quantification of tau pathology in human brain with 11C-PBB3. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:1359–1365. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.160127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schain M, Forsberg A, Lansner A, Halldin C, Varrone A, Farde L. Amyloid clustering for classification of Alzheimer’s disease based on pair-wise correlation between PET-image voxels. International Symposium on Functional NeuroReceptor Mapping of the Living Brain. Amsterdam, Netherlands: P-060; 2014.

- 32.Cselenyi Z, Forsberg A, Eriksdotter Jönhagen M, Halldin C, Julin P, Schou M, et al. Head-to-head comparison of amyloid-specific PET radioligands [18F]AZD4694 and [11C]AZD2184. Human Amyloid Imaging Conference. Miami, FL, USA: P-020; 2011.

- 33.Harada R, Furumoto S, Tago T, Furukawa K, Ishiki A, Tomita N, et al. Characterization of the radiolabeled metabolite of tau PET tracer (18)F-THK5351. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43:2211–2218. doi: 10.1007/s00259-016-3453-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hashimoto H, Kawamura K, Takei M, Igarashi N, Fujishiro T, Shiomi S, et al. Identification of a major radiometabolite of [11C]PBB3. Nucl Med Biol. 2015;42:905–910. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Logan J, Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Ding YS, Alexoff DL. Distribution volume ratios without blood sampling from graphical analysis of PET data. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1996;16:834–840. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199609000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ichise M, Liow JS, Lu JQ, Takano A, Model K, Toyama H, et al. Linearized reference tissue parametric imaging methods: application to [11C]DASB positron emission tomography studies of the serotonin transporter in human brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:1096–1112. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000085441.37552.CA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Betthauser TJ, Lao PJ, Murali D, Barnhart TE, Furumoto S, Okamura N, et al. In vivo comparison of tau radioligands (18)F-THK-5351 and (18)F-THK-5317. J Nucl Med. 2017;58:996–1002. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.182980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rousset OG, Ma Y, Evans AC. Correction for partial volume effects in PET: principle and validation. J Nucl Med. 1998;39:904–911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferreira D, Cavallin L, Granberg T, Lindberg O, Aguilar C, Mecocci P, et al. Quantitative validation of a visual rating scale for frontal atrophy: associations with clinical status, APOE e4, CSF biomarkers and cognition. Eur Radiol. 2016;26:2597–2610. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-4101-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maass A, Landau S, Baker SL, Horng A, Lockhart SN, La Joie R, et al. Comparison of multiple tau-PET measures as biomarkers in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage. 2017;157:448–463. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.05.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arnold SE, Hyman BT, Flory J, Damasio AR, Van Hoesen GW. The topographical and neuroanatomical distribution of neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaques in the cerebral cortex of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Cereb Cortex. 1991;1:103–116. doi: 10.1093/cercor/1.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Serrano-Pozo A, Frosch MP, Masliah E, Hyman BT. Neuropathological alterations in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2011;1:a006189. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harada R, Okamura N, Furumoto S, Tago T, Yanai K, Arai H, et al. Characteristics of tau and its ligands in PET imaging. Biomolecules. 2016;6:7. doi: 10.3390/biom6010007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kang JM, Lee SY, Seo S, Jeong HJ, Woo SH, Lee H, et al. Tau positron emission tomography using [18F]THK5351 and cerebral glucose hypometabolism in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2017;59:210–219. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Csernansky JG, Hamstra J, Wang L, McKeel D, Price JL, Gado M, et al. Correlations between antemortem hippocampal volume and postmortem neuropathology in AD subjects. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2004;18:190–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mitchell TW, Mufson EJ, Schneider JA, Cochran EJ, Nissanov J, Han LY, et al. Parahippocampal tau pathology in healthy aging, mild cognitive impairment, and early Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2002;51:182–189. doi: 10.1002/ana.10086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gordon BA, Friedrichsen K, Brier M, Blazey T, Su Y, Christensen J, et al. The relationship between cerebrospinal fluid markers of Alzheimer pathology and positron emission tomography tau imaging. Brain. 2016;139:2249–2260. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ng KP, Pascoal TA, Mathotaarachchi S, Therriault J, Kang MS, Shin M, et al. Monoamine oxidase B inhibitor, selegiline, reduces 18F-THK5351 uptake in the human brain. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2017;9:25. doi: 10.1186/s13195-017-0253-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harada R, Ishiki A, Kai H, Sato N, Furukawa K, Furumoto S, et al. Correlations of 18F-THK5351 PET with post-mortem burden of tau and astrogliosis in Alzheimer’s disease. J Nucl Med. 2018;59:671–674. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.117.197426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vermeiren C, Motte P, Viot D, Mairet-Coello G, Courade JP, Citron M, et al. The tau positron-emission tomography tracer AV-1451 binds with similar affinities to tau fibrils and monoamine oxidases. Mov Disord. 2018;33:273–281. doi: 10.1002/mds.27271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tong J, Meyer JH, Furukawa Y, Boileau I, Chang LJ, Wilson AA, et al. Distribution of monoamine oxidase proteins in human brain: implications for brain imaging studies. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:863–871. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Passamonti L, Vazquez Rodriguez P, Hong YT, Allinson KS, Williamson D, Borchert RJ, et al. 18F-AV-1451 positron emission tomography in Alzheimer’s disease and progressive supranuclear palsy. Brain. 2017;140:781–791. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, Al-Sarraj S, Bodi I, Bogdanovic N, Braak H, et al. Staging of neurofibrillary pathology in Alzheimer’s disease: a study of the BrainNet Europe consortium. Brain Pathol. 2008;18:484–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00147.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 3710 kb)