Abstract

Rhizosphere microbial community composition can be influenced by different biotic and abiotic factors. We investigated the composition and co-variation of rhizosphere bacterial and fungal communities from two sorghum genotypes (BRS330 and SRN-39) in three different plant growth stages (emergence of the second leaf, (day10), vegetative to reproductive differentiation point (day 35), and at the last visible emerged leaf (day 50)) in two different soil types, Clue field (CF) and Vredepeel (VD). We observed that either bacterial or fungal community had its composition stronger influenced by soil followed by plant growth stage and cultivar. However, the influence of plant growth stage was higher on fungal community composition than on the bacterial community composition. Furthermore, we showed that sorghum rhizosphere bacterial and fungal communities can affect each other’s composition and structure. The decrease in relative abundance of the fungus genus Gibberella over plant growth stages was followed by decrease of the bacterial families Oxalobacteracea and Sphingobacteriacea. Although cultivar effect was not the major responsible for bacterial and fungal community composition, cultivar SRN-39 showed to promote a stronger co-variance between bacterial and fungal communities.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00248-017-1108-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: 16S rRNA, 18S rRNA, Rhizosphere, Sorghum bicolor genotypes

Introduction

The rhizosphere harbors a wide range of microorganisms, which have been shown to influence significantly plant growth, root architecture, and nutrient uptake [1–4]. Conversely, the composition of microbial rhizosphere communities is influenced by biotic and abiotic factors including plant species (or genotypes) and soil management [5–7].

Studies on the impact of different soil fertilization managements on the composition of the bacterial community in the rhizosphere of sorghum have shown that the bacterial community is more affected by compost than by inorganic fertilizers [8]. In addition, geographic location and soil characteristics are the main factors explaining the variability in the structure of the bacterial community in the rhizosphere of sorghum [9]. Moreover, in an earlier study, we found soil to be the most important factor on sorghum rhizosphere bacterial community assembly followed by plant growth stage and plant genotype [10]. Furthermore, we found that along plant growth stage, the impact of soil on the bacterial community assembly reduced and, unlike, the impact of plant genotype increased.

Most of rhizosphere community studies focus on either bacterial or fungal communities. However, the dynamics of both combined communities in different plant species are rather uncommon, but are of great relevance. Marschner et al. [11] showed that arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) infection changes the bacterial community composition in the rhizosphere of maize with time. While studying the impact of elevated atmospheric CO2 on the carbon flow in the rhizosphere in Festuca rubra, Drigo et al. [12] found that the allocation of labile photosynthates from AMF to soil promoted shifts on fungal and bacterial rhizosphere microbial communities. Vázquez et al. [13] showed that the interaction between AMF and the microbial inoculants Azospirillum, Pseudomonas, and Trichoderma induced changes in the microbial population in the rhizosphere of maize. Additionally, through the taxonomic assignment of the annotated rRNA and mRNA reads Chapelle et al. [14] found that Sphingobacteriaceae and Oxalobacteraceae were more abundant in rhizosphere of sugar beet inoculated with Rhizoctonia solani than in non-fungal inoculated plant cultivated in suppressive soil. However, these studies are focused in a single group or single species of fungi effect on bacterial community.

Although studies of combined fungal and bacterial diversity and community composition have been performed in rhizosphere, very few studies have directly correlated the composition of one community to another [15, 16]. Particularly in sorghum, as far as we know, there are no studies on mutual effects on the composition and diversity of bacteria and fungi in the rhizosphere. Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench is the fifth cereal most produced worldwide and is a staple food for more than 500 million people in 30 countries [17]. Sorghum is considered to be drought and salinity tolerant and its adaptation to low fertility soils allows the cultivation of this cereal in tropical areas under adverse climate conditions [18]. Here, we aimed to evaluate the variation of fungal and bacterial communities and the relationship of both communities in rhizosphere of different sorghum genotypes in different soils. We tested the hypothesis that (i) fungal-bacterial interaction in the sorghum rhizosphere is modulated by the tripartite factors: plant genotype, soil type, and plant growth stage and (ii) fungal and bacterial rhizosphere communities compositions are modulated by changes in each other’s abundances.

Material and Methods

Soil Sampling

The soils were collected from two locations in The Netherlands: Clue field (CF) (52°03′37.91″ N and 5°45′7.074″ E) characterized as Arenosol soil (natural soil on former but abandoned field) and Vredepeel (VD) (51°32′25.8″ N and 5°51′15.1″ E) characterized as Gleyic Podzol soil (agriculture field). From each area, the soil samples were collected (0–20 cm topsoil layer) from five points equidistant at 50 m from each other. Once collected, the soil was sieved (4 mm mesh size) and homogenized. The physical and chemical characteristics of each soil are described in Table S1.

Sorghum bicolor Cultivars and Mesocosm Experiment

Two different cultivars from different origins were chosen to assess the bacterial and fungal communities composition in the rhizosphere of S. bicolor: BRS330 cultivar—a hybrid grain resistant to anthracnose, leaf blight, leaf rust, and sooty stripe [19, 20]—and cultivar SRN-39 (grain)—a high producer of orobanchol (strigolactone molecule) root exudate [10] and resistant against the root parasitic weed Striga hermonthica (Del.) Benth [21]. The seeds of cultivar BRS330 were from “Embrapa Milho e Sorgo” (Brazil) and the seeds of cultivar SRN-39 originally released in Niger and Sudan (Africa) [22, 23] were provided by the Laboratory of Plant Physiology—Wageningen University (Netherlands).

The experimental design and sampling consisted of three replicates of two soil types, two sorghum cultivars, and three plant growth stages, in total 36 experimental units randomly distributed in a greenhouse. Fifteen seeds of each sorghum cultivar were sown in soils in plastic pots (6.5 L). The pots were kept under controlled temperature and photoperiod conditions (22 °C/17 °C day/night and photoperiod 16/8 h light/dark). After 5 days, plantlets were trimmed to five seedlings per pot. Rhizosphere soil was sampled after in three different plant growth stages: at the emergence of the second leaf (day10), at the emergency of the fifth leaf when the plants migrate from vegetative to reproductive differentiation point (day 35), and at the last visible emerged leaf (day 50) before the plant flowering. At the first stage of plant growth (day 10), rhizosphere soil was sampled removing the whole plant and brushing the soil adhered to the seminal roots, and for the last stages of plant growth (days 35 and 50), rhizosphere soil was sampled with a cylindrical auger (6 × 150 mm). Bulk soil samples were taken from pots without plants. Rhizosphere and bulk soil samples for DNA extraction were kept at − 80 °C.

DNA Extraction and 16S rRNA Partial Gene Sequencing

DNA was extracted from 0.25 g of soil of each sample using DNA Power soil DNA isolation kit (Mo Bio Laboratories, Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA). DNA integrity was checked by agarose gel (1.5%) electrophoresis in TBE (Tris-borate-EDTA) buffer. DNA from each treatment was used as template for 16S rRNA and 18S rRNA partial genes fragments amplification. The amplification of the 16S rRNA partial gene was performed using the primer set 515F and 806R [24]. Primers contained multiplex tags for sample identification. PCR was carried out using 0.2 μl of 0.056 U fast StartExpTaq Polymerase (Roche Applied Sciences, Indianapolis, IN, USA), 2.5 μl dNTP (2 mM each), 0.25 μl of each primer, and 1.0 μl of DNA template. Thermocycling conditions were as follows: denaturing at 95 °C for 5 min followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 53 °C for 30 s, extension at 72 °C for 60 s followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. As negative control, water was used instead of DNA, and as positive control DNA of Escherichia coli was used. For the 18S rRNA partial gene amplification, a fungal-specific primer set FR1 and FF390.1 [25] was used to amplify a 350 bp region of the 18S rRNA gene. Primers contained multiplex tags for sample identification. PCR reactions were carried out using 2.5 μl of 2 mM dNTP, 0.5 μl of each primer, 1.0 μl of DNA template, and 0.2 μl of 0.056 U of Fast StartExp-Polymerase (Roche Applied Sciences, Indianapolis, IN, USA). The PCR reaction had an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 58 °C for 30 s, extension at 72 °C for 60 s, and the final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. As negative control, water was used instead of DNA. The PCR products were purified using QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen Technologies) and their quality were checked before and after the purification in agarose gel electrophoresis in TBE buffer. The PCR amplicons were quantified using Fragment analyser™—Automated CE system (Advanced Analytical Technologies, Inc) and equimolar pooled. The samples were sequenced in PGM machine on Ion Torrent (Life technology) in Korea (Macrogen Inc. Company, South Korea).

Data Analyses

16S and 18S rRNA Sequences Processing

Forward and reverse primer sequences in the library FASTQ file of each sample were removed using Flexbar version 2.5 [26]. Sequences were filtered for quality criteria with a Phred quality score of 25 and with minimum sequence length of 150 bp by running the FASTQ-MCF [27]. After filtering, FASTQ files were converted to FASTA format and concatenated into a single file. Chimera sequences were detected using the UCHIME algorithm implemented in VSEARCH [28]. The reads were clustered into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTU), within evolutionary distance of 97% using the UPARSE [29] performed with VSEARCH version 1.0.10 [30]. The OTU table was converted to biological observation matrix (BIOM) format 1.3.1 [31] and using the RDP Classifier version 2.10 [32], taxonomic information for each OTU was added to the BIOM file. All procedures were implemented in a Snakemake workflow [33]. The number of sequences in each library was rarefied (alpha_rarefaction.py) to 2.000 sequences for bacteria and to 550 sequences for fungi prior to diversity analyses in QIIME 1.8.0 [34]. The 16S rRNA and 18S rRNA sequence data are available at the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/) under the study accession number PRJEB21895 (ERP024198).

Statistical Analyses

To check the treatment effects on sorghum rhizosphere bacterial and fungal communities composition, between-classes analysis (BCA) and co-inertia analysis (COIA) were performed in R v3.3.3 using the package “ade4” [35]. To explore the dissimilarities of treatments within each community, a principal component analysis (PCA) was used to create BCA tables using the function “bca.” In order to find the similarity of bacterial and fungal community within treatments, BCA tables were used to conduct co-inertia analysis for the two soils using the function “coinertia.” Monte-Carlo test was applied for BCA and COIA using 999 random permutations. For co-inertia, “RV.test” R function was used to perform Monte-Carlo test. As a result of COIA, plots with arrows are formed. The back of the arrow represents the location of bacterial community organisms and the tip of arrow represents the location of fungal community organisms. The strength of the relationship between both communities is inversely related to the length of the arrow. Arrows projected to the same direction showed strong association between the treatments with respect to the microbial composition [36]. Bacterial and fungal community structure co-variance scores were given by COIA analysis. Family groups responsible for such co-variance were those had higher score than the 95% of sample normal distribution. This was calculated by the standard deviation multiplied by 1.96, what is the range that corresponds to 95% of normal distribution of the standard deviation.

To infer how the rhizosphere bacterial community co-varied with the factors soil, cultivar, and plant growth stage, the bacterial and fungal abundance data were transformed by Hellinger transformation [37] using the package Vegan version 2.4.0 [38] and the co-variance was measured by the coefficient RV-Value by multiple factor analysis (MFA) using the package “FactoMineR” [39] in R v3.1.3 program. Moreover, using the same R package, we applied permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) using Bray-Curtis distance matrix with 999 permutations to test the influence of the factors soil, plant growth stage, and cultivar in the rhizosphere bacterial and fungal community.

In order to check for dissimilarities within the microbial communities, treatments were divided into subsets and principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) were performed in QIIME 1.9.1 using the script beta_diversity_through_plots.py with Bray-Curtis distance matrices. Distance matrices generated by PCoA were used to perform PERMANOVA analysis with 9999 random permutations (P < 0.05). For the PCoAs where the treatment effects were significant, microbial community family groups responsible for the dissimilarities were checked. Differences in mean proportion was tested through Welch’s test (P < 0.05) using the Statistical Analysis of Metagenomics Profiles (STAMP) v2.1.3 program [40]. To avoid false discovery rates (FDR), Benjamini-Hochberg [41] was applied.

Alpha diversity index (Shannon), species richness (Chao1), as well as the total number of OTUs were calculated in QIIME 1.9.1 using the command alpha_diversity.py. In order to check for significant differences among samples, analysis of variance ANOVA and Tukey test (P < 0.05) was performed in R for each Alpha diversity index.

Results

Analysis of co-inertia (RV-coefficient) at family level revealed that soil type, plant growth stage, and cultivar explained 52.62, 22.70, and 12.73% of the rhizosphere bacterial community variation, respectively (Table S2). For the fungal community, soil type, plant growth stage, and cultivars explained 42.83, 26.02, and 14.99%, of the variation, respectively (Table S3). We tested the statistical significance of the factors soil, plant growth stage, and cultivar on the rhizosphere bacterial and fungal community structures by PERMANOVA using Bray-Curtis as distance matrix. The results showed that soil had significant effects on both the bacterial (F = 6.87; P < 0.001) and fungal (F = 7.89; P < 0.001) communities; plant growth stage had a significant effect only on the fungal community (F = 2.68; P < 0.001) and cultivar had no significant effect on both communities (Table S4).

Differences in Bacterial Community Structure

PERMANOVA test showed that the bacterial communities from the bulk soils of CF and VD were not significantly different (Pseudo-F: 1.40; P = 0.40) (Fig. S1). However, the same analysis, showed that the bacterial community was significant different in the rhizosphere soils of CF and VD (Pseudo-F: 6.9; P < 0.05) (Fig. S2). Through Welch’s test, we found that among the bacteria families driving this dissimilarity, Bradyrhizobiaceae was more abundant in rhizosphere soil of CF than VD, whereas Caulobactereaceae, Phyllobacteriaceae, and Xanthomonadaceae were more abundant in VD (Fig. S2). Welch’s test revealed a significant difference in rhizosphere bacterial composition between both CF (Pseudo-F: 2.3; P < 0.05) and VD (Pseudo-F: 2.55; P < 0.05) soils (Fig. S3). At CF soil, this difference was mainly caused by unclassified Spartobacteria family with high abundance in bulk soil, and Comamonadaceae, Oxalobacteraceae families and unclassified Alphaproteobacteria with higher abundances in the rhizosphere than in the bulk soil (Fig. S3). At VD soil, Oxalobacteraceae as well as organisms that could not be classified at family taxonomic level belonging to Acidobacteria Gp1, Myxococcales (Gammaproteobacteria), and Proteobacteria were significantly more abundant in rhizosphere than in bulk soil (Welch’s test; P < 0.05) (Fig. S3). PERMANOVA analysis comparing cultivars in the CF soil showed that the rhizosphere bacterial community of cultivar BRS330 significantly differed from that of cultivar SRN-39 (Pseudo-F: 1.14; P < 0.05) (Fig. 1a). Performing Welch’s test we found Bradyrhizobiaceae and Sphingomonadaceae with mean proportion significant highest in rhizosphere of BRS330, whereas Comamonadaceae and unclassified Acidobacteria Gp1 were significant highest in SRN-39 rhizosphere (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

a Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) and b differences in relative abundance of bacteria families between cultivars BRS330 and SRN-39, and c PCoA and d differences in relative abundance of bacteria families between days 10 and 35 at Clue field soil (Welch’s test; P < 0.05)

The only significant difference in the bacterial community composition found over growth stages was in CF soil between the day 10 and 35 of plant growth (Pseudo-F: 1.47; P < 0.05) (Fig. 1c). The two families responsible for this dissimilarity were Oxalobacteraceae and Sphingobacteriaceae with significant highest abundance at day 10 and not at day 35 (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1d).

Differences in Fungal Community Structure

The fungal community in both CF and VD bulk soils did not significantly differ (Pseudo-F: 2.00; P = 0.20) (Fig. S4). However, the fungal rhizosphere community in CF soil was significantly different from that in VD soil (Pseudo-F: 7.9; P < 0.05) (Fig. S5). Hypocreaceae and unclassified Mortierellales were more abundant in the sorghum rhizosphere in CF soil than in VD soil. In contrast, the organisms that could not be classified at the family level belonging to the groups of Saccharomycetales, Sordariales, and Sordariomycetes were significantly more abundant in the rhizosphere community in VD than in CF soil (Fig. S5). PCoA showed a clear distinction in the rhizosphere fungal communities at day 10 as compared to day 35 (Pseudo-F: 2.75; P < 0.05) and 50 (Pseudo-F: 2.24; P < 0.05) in CF soil (Fig. 2a, c). Nectriaceae was found to be the major group responsible for these dissimilarities with higher abundance at day 10 than at days 35 and 50. On the other hand, the abundances of unclassified Chaetothyriales and unclassified Leotiomycetes were lower at day 10 than at days 35 and 50 (Fig. 2b, d). Overall, Nectriaceae was the most abundant fungal family in the Clue field rhizosphere soil (Fig. S6).

Fig. 2.

a Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) and b differences in relative abundance of fungi families between days 10 and 35, and c PCoA and d differences in relative abundance of fungi families between days 10 and 50 in Clue field rhizosphere samples (Welch’s test; P < 0.05)

In VD soil, the rhizosphere fungal community also showed to be different between early (day 10) and late (day 50) plant growth stages (Fig. 3a). Despite the difference in rhizosphere fungal community presented by PCoA plot and PERMANOVA analysis, only one fungal group could be assigned to be responsible for this dissimilarity; unclassified Hypocreales showed higher abundance at day 10 than at day 50 of plant growth (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

a Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) and b differences in relative abundance of fungi families between days 10 and 50 in Vredepeel rhizosphere samples (Welch’s test; P < 0.05)

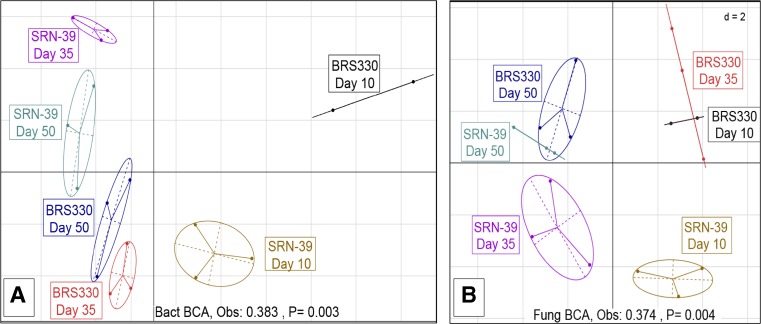

Between-Class and Co-Inertia Analyses

Between classes analysis (BCA) was performed to check for dissimilarities in the total microbial rhizosphere community. At CF soil, bacterial and fungal communities composition were significantly different across sorghum treatments explaining 38% (P = 0.03) and 37% (P = 0.04) of total variation, respectively. Ellipses representing bacterial community composition of the cultivars BRS330 and SRN-39 at early sampling showed a clear separation from the ellipses of the two later samplings (Fig. 4a). For the fungal community, although this separation remained consistent for cultivar SRN-39, for cultivar BRS330, the ellipse separation was more evident in the last sampling (day 50) than the early sampling points (days 10 and 35) (Fig. 4b). At VD soil the rhizosphere bacterial community composition was significantly different among sorghum treatments, explaining 36.8% (P = 0.001) of the total variation. Ellipses dispositions representing the bacterial community of cultivar BRS330 showed a clear separation between the composition of days 10 and 35 to the day 50 of plant growth. Conversely, bacterial community present in rhizosphere cultivar SRN-39 showed similarity between the latest two stages of plant growth (days 35 and 50) with dissimilarity to the day 10 of plant growth (Fig. 5a). No significant difference was found for rhizosphere fungal community at VD soil (Monte-Carlo test) (Fig. 5b).

Fig. 4.

Between-class analysis (BCA) of a bacterial and b fungal communities in sorghum rhizosphere of cultivars BRS 330 and SRN-39 at days 10, 35, and 50 of plant growth stage in Clue field soil

Fig. 5.

Between-class analysis (BCA) of a bacterial and b fungal communities in sorghum rhizosphere of cultivars BRS 330 and SRN-39 at days 10, 35, and 50 of plant growth stage in Vredepeel soil

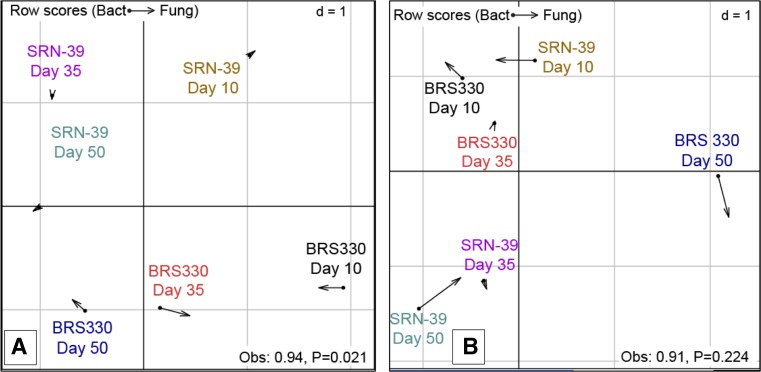

Co-variance between rhizosphere bacterial and fungal community structures was determined using co-inertia analysis (COIA). Plotting bacterial and fungal community’s ordination together resulted in a new ordination plot where an arrow links bacterial to fungal community positions. We observed that treatments in CF and VD soils explained 94 and 91% of the rhizosphere microbial community variation, respectively (Fig. 6a, b). The variation between the bacterial and fungal communities was significantly different in CF soil (P = 0.02). Shorter arrows in cultivar SRN-39 than in cultivar BRS330, in each growth stage, indicate stronger relationship between bacterial and fungal communities in the SRN-39 rhizosphere than in the BRS330 rhizosphere. For cultivar SRN-39, the projection of arrows by day 10 in the opposite direction of days 35 and 50 of plant growth showed that day 10 had a weak similarity on the variation of bacterial-fungal communities compared with days 35 and 50 of plant growth stage. No significant difference was found for VD soil (P = 0.22) (Monte-Carlo test) (Fig. 6b). For each soil, we assessed the representatives of rhizosphere bacterial and fungal communities responsible for the co-variance of each co-inertia axis (Tables S5 and S6).

Fig. 6.

Co-inertia analysis (COIA) of bacterial and fungal communities in a Clue field and b Vredepeel soils. Arrows represent the co-variation of both communities within the treatments: cultivar BRS 330 and SRN-39 at days 10, 35, and 50 of plant growth stage

Alpha Diversity

For bacteria community, Tukey tests applied to all alpha diversity indices (number of OTUs, Chao1 and Shannon (H′)) showed no significant differences between VD and CF bulk soils (P > 0.05). The rhizosphere bacterial community of cultivar SRN-39 at day 10 had significant lower number of OTUs and lower diversity (Shannon H′) in CF than in VD soil. No significant difference in Shannon diversity, Chao1 or number of OTUs was found comparing bulk soil and rhizosphere in CF soil. The rhizosphere community of both cultivars grown in VD soil, at each growth stage, showed higher bacterial diversity and number of OTUs than in bulk soil. However, for both cultivars planted in VD soil, no difference was found among the OTUs and diversity of rhizosphere bacterial community throughout sampling time. For both cultivars planted in CF soil, the richness of the rhizosphere bacterial community was not different from that of bulk soil. In VD soil, the richness (Chao1) in the rhizospheres of cultivars BRS330, at day 10 and SRN-39 at day 50 was significantly higher than the bulk soil, whereas no significant difference was evidenced among rhizosphere treatments (Table S7). For fungal community, no difference in alpha diversity was found (Table S8).

Discussion

Our first hypothesis that fungal-bacterial interaction in the sorghum rhizosphere is modulated by the tripartite factors: plant genotype, soil type, and plant growth stage is accepted. Out results showed that for both bacterial and fungal communities, soil plays the major role in their assembly in sorghum rhizosphere. Although bacterial and fungal community structures showed the same trend regarding to the influence of soil, growth stage, and sorghum cultivar, fungal communities showed to be more influenced by plant growth stage than bacterial communities. Similarly, Han et al. [42] found plant growth stage a dominant factor determining the structure of the fungal community as compared to edaphic factors in the soybean rhizosphere. We suggest that the fungal community composition was more affected by plant growth stage than the bacterial community composition as the result of the versatility that fungi can interact with plants in different stages of plant development, acting as pathogens, symbionts, and saprotrophic [43–45]. Moreover, plants release different exudates of different chemical structure complexities during different growth stages [46], which may have larger effects on fungi in the rhizosphere than on bacteria.

The influence of plant growth stage on the fungal rhizosphere community is evidenced by the significant higher relative abundance of Nectriaceae at day 10 (38.8%) compared with day 35 (18%) and 50 (12%) in the CF soil. Nectriaceae showed the highest relative abundance (21%) among fungal families, all belonging to the Gibberella genus (Fig. S6). Similar results were found by Grudzinska-Sterno et al. [47] in wheat growth stages that Gibberella avenacea significantly decreased, at least four times fold, from young to mature plants. All Gibberella species are sexual stages of Fusarium species [48], which genus contains many plant pathogens and mycotoxin producers, being of great agricultural and economical importance [49]. At CF soil, the bacterial families of Sphingobacteriaceae and Oxalobacteraceae decreased significantly in time. Corroborating with our findings, Green et al. [50] studying the bacterial community composition of cucumber root observed a decrease in abundance of Oxalobacteraceae from early to late plant growth stage. The second hypothesis that fungal and bacterial rhizosphere communities’ compositions are modulated by changes in each other’s abundances is accepted. Although the relationship in the observed abundances of Sphingobacteriaceae and Oxalobacteraceae bacteria and Gibberella fungi was not experimentally assessed, we suggest that there may be some link between these organisms, as both bacterial families are known to be antagonist to fungal activity. Oxalobacteraceae were reported to have antifungal, chitinolytic, and mycophagous characteristics, being suppressive toward fungi plant pathogens including Fusarium species [44, 51, 52]. Moreover, Fusarium species are known to produce oxalic acid [53] that may have attracted members of Oxalobacteraceae that are characterized for their ability to degrade oxalate [54, 55].

Although the effect of plant growth on the dissimilarity of fungal community was evidenced for both soils, this effect was stronger in CF than VD soil. Furthermore, bacterial and fungal communities showed significant variation between each other at CF soil, whereas no difference was verified in VD soil. We hypothesize that influence of CF soil on microbial community variation is linked with low soil fertility. The fertility of CF measured by the sum of bases was less than half of that of VD soil [10]. Additionally, at CF soil the co-variance of bacterial and fungal communities of the rhizosphere of cultivar SRN-39 was higher than at cultivar BRS330 for all plant growth stages. Although cultivar had smaller effects on the selection of bacterial and fungal communities, it may play an important role in the interaction of both microbial communities. However, given the relative small effects of cultivars and growth stages on rhizosphere microbial community composition, we conclude that the effects of growth stage and cultivar differences on microbial community composition were soil dependent.

The initial community (bulk soil) either for bacterial or fungal community did not differ between both soils regarding α and β-diversity. However, soils showed to have different microbial community β-diversity composition at the rhizosphere compartment. We speculate that this difference may be linked with the variation on carbon inputs released by plants to the rhizosphere depending on soil characteristics [56, 57]. The fungal diversity did not differ among treatments for the both soils.

The results revealed in this work lead us to the conclusion that fungal and bacterial communities varied with each other in sorghum rhizosphere. The strength of this co-variance is dependent of soil, plant growth stage, plant genotype, and microbial composition. Although cultivar effect was not the major responsible for bacterial and fungal community composition, cultivar SRN-39 showed to promote a stronger co-variation between bacterial and fungal communities.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(DOCX 214 kb)

(DOCX 1.8 mb)

(DOCX 1.49 mb)

(DOCX 213 kb)

(DOCX 610 kb)

(DOCX 278 kb)

(DOCX 18.1 kb)

(DOCX 16.6 kb)

(DOCX 16.7 kb)

(DOCX 17.9 kb)

(DOCX 18 kb)

(DOCX 19.1 kb)

(DOCX 20.3 kb)

(DOCX 20 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Agata Pijl for laboratory assistance, Mattias de Hollander and Marcio Leite for bioinformatics and statistics support, and Dr. Francisco de Souza and Prof. Harro Bouwmeester for providing sorghum seeds. Publication number 6412 of the NIOO-KNAW, Netherlands Institute of Ecology.

Funding Information

This work was supported by Brazilian Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES: 1549-13-8) and The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO, 729.004.003).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00248-017-1108-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Bonfante P, Anca IA. Plants, mycorrhizal fungi, and bacteria: a network of interactions. Ann Rev Microbiol. 2009;63:363–383. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.091208.073504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vacheron J, Desbrosses G, Bouffaud M-L, Touraine B, Prigent-Combaret C. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria and root system functioning. Front Plant Sci. 2013;17:356. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berendsen RL, Pieterse CMJ, Bakker PAHM. The rhizosphere microbiome and plant health. Trends Plant Sci. 2012;17:478–486. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mendes LW, Kuramae EE, Navarrete AA, van Veen JA, Tsai SM. Taxonomical and functional microbial community selection in soybean rhizosphere. ISME J. 2014;8:1577–1587. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Navarrete AA, Kuramae EE, de Hollander M, Pijl AS, van Veen JA, Tsai SM. Acidobacterial community responses to agricultural management of soybean in Amazon forest soils. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2013;83:607–621. doi: 10.1111/1574-6941.12018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lima AB, Cannavan FS, Navarrete AA, Teixeira WG, Kuramae EE, Tsai SM. Amazonian dark earth and plant species from the Amazon region contribute to shape rhizosphere bacterial communities. Microb Ecol. 2015;69:855–866. doi: 10.1007/s00248-014-0472-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inceoglu O, Salles JF, van Overbeek L, van Elsas JD. Effects of plant genotype and growth stage on the betaproteobacterial communities associated with different potato cultivars in two fields. App Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:3675–3684. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00040-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lavecchia A, Curci M, Jangid K, Whitman WB, Ricciuti P, Pascazio S, Crecchio C. Microbial 16S gene-based composition of a sorghum cropped rhizosphere soil under different fertilization managements. Biol Fert Soils. 2015;51:661–672. doi: 10.1007/s00374-015-1017-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramond JB, Tshabuse F, Bopda CW, Cowan DA, Tuffin MI. Evidence of variability in the structure and recruitment of rhizospheric and endophytic bacterial communities associated with arable sweet sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L) Moench) Plant Soil. 2013;372:265–278. doi: 10.1007/s11104-013-1737-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schlemper TR, Leite MF, Lucheta AR, Shimels M, Bouwmeester HJ, van Veen JA, Kuramae EE (2017) Rhizobacterial community structure differences among sorghum cultivars in different growth stages and soils. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 10.1093/femsec/fix096 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Marschner P, Crowley DE, Lieberei R. Arbuscular mycorrhizal infection changes the bacterial 16 S rDNA community composition in the rhizosphere of maize. Mycorrhiza. 2001;11:297–302. doi: 10.1007/s00572-001-0136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drigo B, Kowalchuk GA, Knapp BA, Pijl AS, Boschker HTS, van Veen JA. Impacts of 3 years of elevated atmospheric CO2 on rhizosphere carbon flow and microbial community dynamics. Glob Change Biol. 2013;19(2):621–636. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vázquez MM, César S, Azcón R, Barea JM. Interactions between arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and other microbial inoculants (Azospirillum, Pseudomonas, Trichoderma) and their effects on microbial population and enzyme activities in the rhizosphere of maize plants. Applied Soil Ecol. 2000;15:261–272. doi: 10.1016/S0929-1393(00)00075-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chapelle E, Mendes R, Bakker PAH, Raaijmakers JM. Fungal invasion of the rhizosphere microbiome. ISME J. 2016;10:265–268. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cassman NA, Leite MF, Pan Y, de Hollander M, van Veen JA, Kuramae EE. Plant and soil fungal but not soil bacterial communities are linked in long-term fertilized grassland. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:1–11. doi: 10.1038/srep23680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bell TH, Hassan SE-D, Lauron-Moreau A, Al-Otaibi F, Hijri M, Yergeau E, St-Arnaud M. Linkage between bacterial and fungal rhizosphere communities in hydrocarbon-contaminated soils is related to plant phylogeny. ISME J. 2014;8:331–343. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rao SP, Reddy BVS, Nagaraj N, Upadhyaya HD (2014) Sorghum production for diversified uses. In: Wang YH, Upadhyaya HD, Kole C (eds) Genetics, genomics and breeding of Sorghum. CRC Press, FL, pp 1–27

- 18.Pinho RMA, Santos EM, Oliveira JSD, Bezerra HFC, Freitas PMDD, Perazzo AF, Ramos RCS, Silva APGD (2015) Sorghum cultivars of different purposes silage. Ciênc Rural 45(2):298–303

- 19.Cota LV, da Costa RV, da Silva DD, Rodrigues JAS, Tardin FD, da Parrella, RAC (2012) Avaliação da resistência de híbridos e linhagens de sorgo a Exserohilum turcicum. http://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br/handle/doc/943804. Accessed 21 Aug 2017

- 20.Cota LV, da Silva DD, da Costa RV, Ramos TCDAA (2013) Caracterização e identificação de fontes de resistência à mancha foliar causada por Ramulispora sorghi em genótipos de sorgo. http://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br/handle/doc/982959. Accessed 21 Aug 2017

- 21.Gobena D, Shimels M, Rich PJ, Ruyter-Spira C, Bouwmeester H, Kanuganti S, Mengiste T, Ejeta G. Mutation in sorghum low germination stimulant 1 alters strigolactones and causes striga resistance. PNAS. 2017;114:4471–4476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1618965114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olembo K, M’mboyi F, Kiplagat S, Oyufi F. Sorghum breeding in sub-saharan Africa. Nairobi: African Biotechnology; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ejeta G (2005) Integrating biotechnology, breeding, and agronomy in the control of the parasitic weed Striga spp in sorghum. In: Tuberosa R, Phillips RL, Gale M (eds) In the wake of the double helix: from the green revolution to the gene revolution, Bologna Bologna, pp 239–251

- 24.Bergmann GT, Bates ST, Eilers KG, Lauber CL, Caporaso JG, Walters WA, Knight R, Fierer N. The under-recognized dominance of Verrucomicrobia in soil bacterial communities. Soil Biol Biochem. 2011;43:1450–1455. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verbruggen E, Kuramae EE, Hillekens R, de Hollander M, Kiers ET, Röling WF, Kowalchuk GA, van der Heijden MG. Testing potential effects of maize expressing the Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ab endotoxin (Bt maize) on mycorrhizal fungal communities via DNA-and RNA-based pyrosequencing and molecular fingerprinting. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:7384–7392. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01372-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dodt M, Roehr JT, Ahmed R, Dieterich C. FLEXBAR—flexible barcode and adapter processing for next-generation sequencing platforms. Biology. 2012;1:895–905. doi: 10.3390/biology1030895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aronesty E (2011) Ea-utils : Command-line tools for processing biological sequencing data. https://github.com/ExpressionAnalysis/ea-utils. Accessed 21 Aug 2017

- 28.Edgar RC, Haas BJ, Clemente JC, Quince C, Knight R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2194–2200. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flouri T, Ijaz U, Mahé F, Nichols B, Quince C, Rognes T (2015) VSEARCH GitHub repository. Release 1.0. 16. Database: GitHub. https://github.com/torognes/vsearch Accessed 21 Aug 2017

- 31.McDonald D, Clemente JC, Kuczynski J, Rideout JR, Stombaugh J, Wendel D, Wilke A, Huse S, Hufnagle J, Meyer F. The biological observation matrix (BIOM) format or: how I learned to stop worrying and love the ome-ome. GigaScience. 2012;1:1–6. doi: 10.1186/2047-217X-1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cole JR, Wang Q, Fish JA, Chai B, McGarrell DM, Sun Y, Brown CT, Porras-Alfaro A, Kuske CR, Tiedje JM. Ribosomal database project: data and tools for high throughput rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D633–D642. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Köster J, Rahmann S. Snakemake—a scalable bioinformatics workflow engine. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:2520–2522. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Pena AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI, Huttley GA, Kelley ST, Knights D, Koenig JE, Ley RE, Lozupone CA, McDonald D, Muegge BD, Pirrung M, Reeder J, Sevinsky JR, Tumbaugh PJ, Walters WA, Widmann J, Yatsunenko T, Zaneveld J, Knight R. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dray S, Dufour A-B. The ade4 package: implementing the duality diagram for ecologists. J Stat Softw. 2007;22:1–20. doi: 10.18637/jss.v022.i04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Culhane AC, Perrière G, Higgins DG. Cross-platform comparison and visualisation of gene expression data using co-inertia analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2003;4:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Legendre P, Gallagher ED. Ecologically meaningful transformations for ordination of species data. Oecologia. 2001;129:271–280. doi: 10.1007/s004420100716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Friendly M, Kindt R, Legendre P, McGlinn D, Minchin PR, O'Hara RB, Simpson GL, Solymos P, Stevens MHH, Szoecs E, Wagner H (2016) Vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.4–3. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan Accessed 21 Aug 2017

- 39.Lê S, Josse J, Husson F. FactoMineR: an R package for multivariate analysis. J Stat Softw. 2008;25:1–18. doi: 10.18637/jss.v025.i01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parks DH, Tyson GW, Hugenholtz P, Beiko RG. STAMP: statistical analysis of taxonomic and functional profiles. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:3123–3124. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Royal Stat Soc Series B (Methodological) 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Han LL, Wang JT, Yang SH, Chen WF, Zhang LM, He JZ. Temporal dynamics of fungal communities in soybean rhizosphere. J Soils Sedim. 2017;17:491–498. doi: 10.1007/s11368-016-1534-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pasqualini D, Uhlmann A, Stürmer SL. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities influence growth and phosphorus concentration of woody plants species from the Atlantic rain forest in South Brazil. Forest Ecol Manag. 2007;245:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2007.04.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haack FS, Poehlein A, Kröger C, Voigt CA, Piepenbring M, Bode HB, Daniel R, Schäfer W, Streit WR. Molecular keys to the Janthinobacterium and Duganella spp. interaction with the plant pathogen Fusarium graminearum. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1668. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van der Wal A, Ottosson E, de Boer W. Neglected role of fungal community composition in explaining variation in wood decay rates. Ecology. 2015;96:124–133. doi: 10.1890/14-0242.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berg G, Smalla K. Plant species and soil type cooperatively shape the structure and function of microbial communities in the rhizosphere. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2009;68:1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2009.00654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grudzinska-Sterno M, Yuen J, Stenlid J, Djurle A. Fungal communities in organically grown winter wheat affected by plant organ and development stage. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2016;146:401–417. doi: 10.1007/s10658-016-0927-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Desjardins AE. Gibberella from A (venaceae) to Z (eae) 1 2. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2003;41:177–198. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.41.011703.115501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karlsson I, Edel-Hermann V, Gautheron N, Durling MB, Kolseth A-K, Steinberg C, Persson P, Friberg H. Genus-specific primers for study of Fusarium Communities in field samples. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82:491–501. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02748-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Green SJ, Inbar E, Michel FC, Hadar Y, Minz D. Succession of bacterial communities during early plant development: transition from seed to root and effect of compost amendment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:3975–3983. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02771-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cretoiu MS, Korthals GW, Visser JH, van Elsas JD. Chitin amendment increases soil suppressiveness toward plant pathogens and modulates the actinobacterial and oxalobacteraceal communities in an experimental agricultural field. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:5291–5301. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01361-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Boer W, Leveau JH, Kowalchuk GA, Gunnewiek PJK, Abeln EC, Figge MJ, Sjollema K, Janse JD, van Veen JA. Collimonas fungivorans gen. nov., sp. nov., a chitinolytic soil bacterium with the ability to grow on living fungal hyphae. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54:857–864. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02920-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Amaral DL, dos Anjos PN, de Souza VC, Aragão FJL, de Oliveira SM. Control of Fusarium oxysporum infection in transgenic tobacco carrying oxalate descarboxilase gene. J Appl Biol Biotech. 2017;5:079–083. doi: 10.7324/JABB.2017.50114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sahin N, Portillo MC, Kato Y, Schumann P. Description of Oxalicibacterium horti sp. nov. and Oxalicibacterium faecigallinarum sp. nov., new aerobic, yellow-pigmented, oxalotrophic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Let. 2009;296:198–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miller AW, Dearing D. The metabolic and ecological interactions of oxalate-degrading bacteria in the mammalian gut. Pathogens. 2013;2:636–652. doi: 10.3390/pathogens2040636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baudoin E, Benizri E, Guckert A. Impact of artificial root exudates on the bacterial community structure in bulk soil and maize rhizosphere. Soil Biol Biochem. 2003;35:1183–1192. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(03)00179-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Badri DV, Vivanco JM. Regulation and function of root exudates. Plant Cell Environ. 2009;32:666–668. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.01926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 214 kb)

(DOCX 1.8 mb)

(DOCX 1.49 mb)

(DOCX 213 kb)

(DOCX 610 kb)

(DOCX 278 kb)

(DOCX 18.1 kb)

(DOCX 16.6 kb)

(DOCX 16.7 kb)

(DOCX 17.9 kb)

(DOCX 18 kb)

(DOCX 19.1 kb)

(DOCX 20.3 kb)

(DOCX 20 kb)