Abstract

Asthma is a global and increasingly prevalent disease. According to the World Health Organization, approximately 235 million people suffer from asthma. Studies suggest that fine particulate matter (PM2.5) can induce innate immune responses, promote allergic sensitization, and exacerbate asthmatic symptoms and airway hyper-responsiveness. Recently, severe asthma and allergic sensitization have been associated with T-helper cell type 17 (TH17) activation. Few studies have investigated the links between PM2.5 exposure, allergic sensitization, asthma, and TH17 activation. This study aimed to determine whether (1) low-dose extracts of PM2.5 from California (PMCA) or China (PMCH) enhance allergic sensitization in mice following exposure to house dust mite (HDM) allergen; (2) eosinophilic or neutrophilic inflammatory responses result from PM and HDM exposure; and (3) TH17-associated cytokines are increased in the lung following exposure to PM and/or HDM. Ten-week-old male BALB/c mice (n = 6–10/group) were intranasally instilled with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), PM+PBS, HDM, or PM+HDM, on days 1, 3, and 5 (sensitization experiments), and PBS or HDM on days 12–14 (challenge experiments). Pulmonary function, bronchoalveolar lavage cell differentials, plasma immunoglobulin (Ig) protein levels, and lung tissue pathology, cyto-/chemo-kine proteins, and gene expression were assessed on day 15. Results indicated low-dose PM2.5 extracts can enhance allergic sensitization and TH17-associated responses. Although PMCA+HDM significantly decreased pulmonary function, and significantly increased neutrophils, Igs, and TH17-related protein and gene levels compared with HDM, there were no significant differences between HDM and PMCH+HDM treatments. This may result from greater copper and oxidized organic content in PMCA versus PMCH.

Keywords: PM2.5, neutrophils, lung, TH17 cytokines, allergy, sensitization

Asthma is a global and increasingly prevalent disease, with at least 383 000 attributed deaths in 2015 (CDC, 2017; WHO, 2017). It affects 24.6 million Americans with an overall population prevalence of approximately 7.8%, including 8.4% for children 0–18-years old and 7.6% for adults ≥18-years old (CDC, 2017). China is one of the most asthma-afflicted countries, with approximately 30 million people affected by the disease (Zhang et al., 2016). The national average prevalence of asthma was 2.46% in 2012 (Fu et al., 2016), and increased ambient levels of particulate matter (PM) with an aerodynamic diameter ≤2.5 µm (PM2.5) is a risk factor for asthma (Chen et al., 2016).

Airway inflammation is a fundamental element of asthma, and chronic eosinophilic inflammation, a T-helper cell type 2 (TH2) immune response is common in some asthmatic patients (Fahy, 2015). However, TH2 immune responses alone can’t explain the heterogeneous nature of asthma, including eosinophilic and noneosinophilic phenotypes. Recent studies indicate severe asthma is associated with increased T-helper cell type 17 (TH17), not TH2, cytokines (Kim et al., 2016; Massoud et al., 2016).

TH17 cells, which mediate neutrophil recruitment, may play an influential role in severe asthma pathogenesis (Kim et al., 2016). People with severe asthma show acute airway hyper-responsiveness (AHR), robust neutrophilia, and high interleukin (IL)-17A production (Manni et al., 2014; Moore et al., 2014). In addition to IL-17A, TH17 cells also produce IL-17F, -21, and -22, which are known to mediate neutrophilia and influence asthma severity (Ouyang et al., 2008). Neutrophilic inflammation is associated with poor lung function and airflow obstruction in asthma (Al-Ramli et al., 2009; Moore et al., 2014).

The ability of PM to promote allergic sensitization to inhaled allergens has been studied for almost 20 years (Lambert et al., 2000). Extensive epidemiological, clinical intervention, and animal model studies suggest urban PM, a major ambient air pollutant with at least 4.2 million attributed deaths in 2015 (Landrigan et al., 2017), contributes to respiratory disease (Guan et al., 2016), and possesses immunological adjuvant activity that promotes allergic responses. Recently, PM was shown to induce IL-17A and AHR (Saunders et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2017) as well as downstream inflammatory products of TH17 cells in lungs of exposed mice (Kuroda et al., 2016).This prompted us to explore the roles of PM2.5 and TH17 cells in allergic asthma. Previous in vivo studies demonstrated associations between allergic responses and PM doses ≥200 µg (Gold et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2017). However, to our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate, in an animal model of allergic asthma, whether (1) low-dose extracts of ambient PM2.5 from 2 geographically distinct areas can lead to enhanced allergic sensitization following exposure to house dust mite (HDM) allergen, a ubiquitous allergen that causes allergies and asthma; and (2) PM2.5 extracts enhance allergic asthma via TH17-induced neutrophils. Most mouse studies of PM2.5 and asthma, including those by Castañeda and Pinkerton (2016), Castañeda et al. (2017), Gold et al. (2016), and Wang et al. (2017) focused on TH2-mediated eosinophilic asthma.

In the present study, PM2.5 was collected from Sacramento, the capital of California, and Jinan, a provincial capital city in China. Both cities experience high air pollution (Ryan-Ibarra et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2017) and asthma rates, and are located in valleys making emissions difficult to dissipate, especially in the winter during strong meteorological inversions. In 2012, Sacramento County’s lifetime asthma prevalence was estimated at 10.6% of children and 16.4% of adults, which is greater for both groups compared with the national rates of 9.5% and 8.2%, respectively (California Health Interview Survey, 2012). Sacramento is the 14th-ranked U.S. city displaying high short-term particulate air pollution. Similarly, Jinan is one of the most air polluted cities in eastern China. In 2013, the annual average concentration of PM2.5 was 108 μg/m3, much greater than the safe level (10 μg/m3) recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2016; Zhang et al., 2017). Asthma prevalence for all ages in Jinan was 1.1% (Wang et al., 2013).

In this study, PM2.5 collected from Sacramento and Jinan was suspended in water to produce stock extract samples of PM2.5 from Sacramento, California (PMCA) and PM2.5 from Jinan, China (PMCH), respectively. These samples were chemically characterized, and administered to mice following allergic sensitization with HDM intermittently over a 2-week period. Pulmonary function measurements were made, and pulmonary inflammation was assessed by bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cell differentials and lung histopathology. Cytokines known to induce the differentiation of TH17 cells from naive T cells, neutrophilic chemokines, and other TH17-related cyto-/chemo-kines were measured.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ambient PM2.5 collection and extraction

Ambient PM2.5 was collected during the winters (December months) of 2013 in downtown Sacramento, California, and 2015 in downtown Jinan, Shandong, China. The sampling site in downtown Sacramento was located on the rooftop of a 2 story building at the northeast corner of T Street and 13th Street (38°34'N, −121°29'W). The sampling site in downtown Jinan was located on the rooftop of a 3 story building at the primary school of Wang She Rem (36°40'N, −117°09'E). Both sampling sites are within a quarter mile of a major freeway interchange and surrounded by a mixture of residential, commercial, and industrial sources.

In Sacramento, PM2.5 was collected for 7 days with a high-volume sampler system (Tisch Environmental Inc., TE-6070V-2.5-HVS) that was equipped with a PM2.5 size-selective head (Tisch Environmental Inc., TE-6001), operated at a flow rate of 40 cfm, and loaded with Teflon-coated borosilicate glass microfiber filters (Pall Corporation, TX40H120WW-8X10). Glass filters from Sacramento were precleaned via successive sonication in Milli-Q water, dichloromethane, and hexane.

In Jinan, PM2.5 was collected for 1 day on 90 mm diameter sized quartz microfiber filters (Whatman) using a high-volume particle collector (Thermo Anderson, USA) fitted with a PM2.5 inlet, and operated at a flow rate of 1.13 m3/min. Quartz filters from China were preheated at 450°C for 24 h before sampling to eliminate endotoxin.

The primary difference between the 2 sampling systems was the type of filter used to collect PM. Both systems deployed PM2.5 size cuts, and flow rate and sampling time differences only affect the total PM mass sampled. Since both filter types used glass microfibers, it is assumed that the retention efficiency with respect to PM composition is similar between them.

After particle collection, all particle extractions and sample preparations were performed at the University of California, Davis. Collection sample filters were weighed to calculate the Sacramento and Jinan PM2.5 concentrations, placed in Milli-Q water, and bath sonicated for 1 h at 60 sonications/min. The sonicated PM samples were then filtered using a 0.2-μm pore size syringe filter. The filtered extracts from Sacramento and Jinan (PMCA and PMCH, respectively; approximately 100 ml each) were lyophilized to dry PM to determine the exact mass of extracted PMCA and PMCH, resuspended in Milli-Q water to produce stock PMCA and PMCH samples with final PM concentrations of 1 mg/ml, and frozen at −20°C.

It is possible that extraction protocols have compositional biases that, when applied to samples of significantly different composition, may produce an enrichment in 1 sample over the other for specific classes of compounds. However, this is very difficult to measure, and its effect on toxicological response is assumed to be negligible in this study since the filters from Jinan and Sacramento were extracted using identical techniques, and both chemical and toxicological comparisons were made with respect to the sample extracts. Details of extraction methods used in this study can be found in Bein and Wexler (2015), which describes a comprehensive inter-comparison of the compositional variance produced by different extraction protocols on a single PM sample. The study by Bein and Wexler (2015) illustrates the significance of directly characterizing the extracted PM used in toxicological studies, and standardizing filter extraction objectives and procedures to avoid introducing study bias.

Characterization of PM stock samples by high-resolution aerosol mass spectrometry

All chemical characterization tests were performed at the University of California, Davis. Frozen stock samples of PMCA and PMCH were thawed to approximately 4°C and sonicated as described above for 20 min to ensure thorough dispersion of the PM. These samples were then analyzed for size, organic species, nitrate (NO3−), sulfate (), chloride (Cl−), and ammonium () using high-resolution aerosol mass spectrometry (HR-AMS), a technique extensively used to characterize the composition of ambient aerosols (Canagaratna et al., 2007). In this process, the defrosted and sonicated stock PMCA and PMCH samples were diluted by a factor of 10, and 1 ml of each sample was atomized using a constant output aerosol generator with argon. The generated aerosol passed through a silica gel drier before being sampled by HR-AMS. The elemental composition of the organic fraction in each of the samples was determined by the method of Aiken et al. (2008) to indicate the average degree of oxidation of organic matter in the particles. Additional details on the analytical methods and data analysis for the chemical characterization of the stock samples are described elsewhere (Sun et al., 2011).

Measurement of metals in PM stock samples by inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry

Metals were measured using an Agilent 8900 Triple Quadrupole inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) at the University of California, Davis. PMCA and PMCH stock samples were analyzed for a broad range of elements, including but not limited to manganese (Mn), iron (Fe), copper (Cu), arsenic (As), nickel (Ni), and lead (Pb) (Table 1). To each of the previously defrosted stock samples, 0.06 ml of concentrated nitric acid (15.968 M, Fischer Scientific) was added, followed by the addition of Milli-Q water. The final volume of each sample was 2 ml, and the resulting concentrations of the samples analyzed by ICP-MS were 0.34 mg/ml for PMCA and 0.45 mg/ml for PMCH. Aerosolized particles were generated by nebulizing the samples, which were then introduced by an argon carrier gas into a high-temperature argon plasma. Calibration standards were run as well.

Table 1.

Concentrations of Various Elements Measured in the California and China PM Samples by ICP-MS

| Sample Concentration (ppm) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Element | California | China | Fold Differencea |

| Potassium (K) | 15.306 | 11.757 | 1.3 |

| Calcium (Ca) | 7.605 | 5.206 | 1.5 |

| Sodium (Na) | 18.805 | 23.677 | 0.8 |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 1.722 | 1.072 | 1.6 |

| Aluminum (Al) | 0.878 | 0.7 | 1.3 |

| Manganese (Mn) | 0.106 | 0.226 | 0.5 |

| Iron (Fe) | 1.119 | 0.337 | 3.3 |

| Copper (Cu)b | 2.13 | 0.119 | 17.9 |

| Zinc (Zn) | 3.735 | 2.045 | 1.8 |

| Selenium (Se) | 0.011 | 0.066 | 0.2 |

| Nickel (Ni) | 0.027 | 0.023 | 1.2 |

| Lead (Pb) | 0.046 | 0.305 | 0.2 |

Fold difference compares values from California and China samples.

Bold font indicates the element with the greatest fold difference.

Animal model: HDM allergen and PM administration

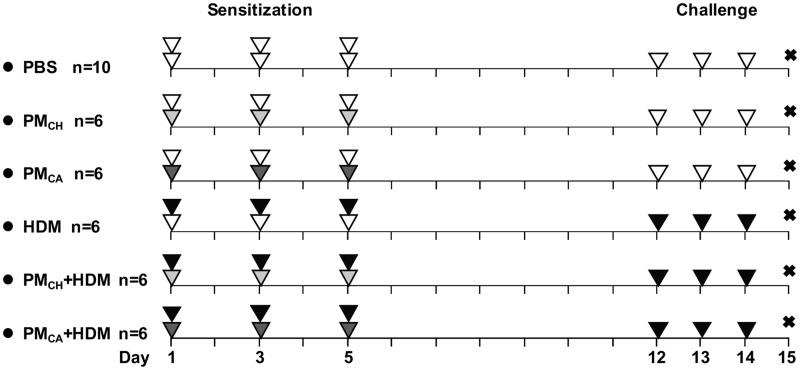

Ten-week-old male BALB/c mice were purchased from Harlan Laboratories (Livermore, California). Animal housing and experiments were reviewed and approved by the UC Davis Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The mice were acclimated for 1 week and then randomly divided into 6 groups (n = 6–10 mice per group) at the start of a 14-day intermittent exposure protocol which included sensitization and challenge experiments (illustrated in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Allergic sensitization and challenge protocol. A total of 6 different treatment groups are shown along with their respective sensitization/challenge instillates. Sensitization and challenge experiments are shown on the left (days 1, 3, and 5) and right (days 12–14) sides, respectively. The “X” represents the day 15 necropsy. Intranasal instillates were PBS (white triangle), HDM allergen solution (black triangle), and/or extracts of PMCH (light gray triangle) or PMCA (dark gray triangle). Each triangle in the figure represents 1 instillation. For the sensitization procedures, the first (33.3 µl/mouse) and second (25 µl/mouse) instillations of the day are represented by the bottom and top triangles, respectively. The single instillation given during each challenge day was at a volume of 25 µl/mouse.

Prior to beginning sensitization experiments, which were performed on days 1, 3, and 5, HDM allergen extract (Greer Laboratories, Lenoir, North Carolina) was dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; delivery vehicle) to produce a 1 mg/ml HDM solution. Stock samples of PMCA and PMCH were defrosted and sonicated as described earlier for 20 min immediately prior to administration.

During the sensitization experiments, each mouse was intranasally instilled twice per day with a 15-min rest period between each instillation. Upon the first instillation of the day, all mice received 33.3 µl of PBS (negative control) or 1 of the 2 stock PM samples. Given that the PMCA and PMCH sample concentrations were 1 mg/ml, the PM dose was 33.3 µg/mouse/day. Upon the second instillation of the day, all mice received 25 µl of PBS or the HDM solution (positive control). Given that the HDM solution was also 1 mg/ml, all mice instilled with it received 25 µg HDM/day. During the sensitization experiments, the total instillation volume for all mice was 58.3 µl/day.

Challenge experiments were performed on days 12–14. During these experiments, mice were instilled once per day with 25 µl of PBS or the HDM solution. As a result of the sensitization/challenge experiments, treatment groups included (1) PBS/PBS; (2) PMCA/PBS; (3) PMCH/PBS; (4) HDM/HDM; (5) PMCA+HDM/HDM; or (6) PMCH+HDM/HDM. These groups are abbreviated as PBS, PMCA, PMCH, HDM, PMCA+HDM, and PMCH+HDM, respectively. The experimental protocol was modeled after that developed by Castañeda and Pinkerton (2016) to study various characteristics of air pollution (eg, PM size, source, chemical composition) and discern how they may affect allergic responses in a mouse model of asthma.

Pulmonary function measurements

On day 15 (24 h after the final challenge), mice were deeply anesthetized with tiletamine-zolazepam (50 mg/kg) and dexmedetomidine (0.7 mg/kg) by intraperitoneal injection and paralyzed with an intramuscular injection of succinylcholine (1 mg). The mice were intratracheally cannulated, and a FlexiVent System (SCIREQ, Montreal, Canada) was used for pulmonary function measurements and AHR tests, which use methacholine (MCh) challenges (doses: 1.25, 2.5, 5, and 10 mg/ml). AHR is a diagnostic index of asthma. Measurement of AHR by MCh challenge is recommended to determine asthma severity. Ventilation was set at a frequency of 200 breaths/min with a tidal volume (volume of a resting breath) of 10 ml/kg. Respiratory system input impedance measures were obtained to distinguish central and peripheral lung mechanics.

Resistance (a measure of airflow due the presence of airway secretions and/or hyper-reactive airway smooth muscle tone), compliance (a measure of the distensibility of the lungs), and elastance (a measure of the recoil of the lungs due to the elasticity of the lung tissues, ie, airways and parenchyma) were measured for the whole respiratory system. Central airway resistance, tissue hysteresis (a measure of the function of pulmonary surfactant of the lungs; how well the lungs inflate/deflate), and tissue elastance were determined after forced oscillation perturbation was applied. The forced oscillation technique enables measurement of lung function in mice in a comprehensive, detailed, precise and reproducible manner. It provides measurements of respiratory system mechanics through the analysis of pressure and volume signals acquired in reaction to predefined, small amplitude, oscillatory airflow waves, which are typically applied at the mouse airway opening (McGovern et al., 2013). All pulmonary function data were measured in triplicate and averaged for each animal (n = 6/treatment group). The EC200RL (effective MCh concentration that leads to a 2-fold increase in resistance) was calculated from the MCh challenge results to determine AHR.

BAL collection and cellular analysis

After the pulmonary function measurements, mice (n = 6/treatment group) were weighed, euthanized with an intraperitoneal injection of Beuthanasia-D (1 mg/ml), and intratracheally cannulated. The left lung was clamped, while the right lung was lavaged with 2 volumes of 0.6 ml cold sterile PBS (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, Missouri) prior to being snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. The lavage fluid was centrifuged at 500 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The resulting supernatant was removed and frozen, and the cells were resuspended in 500 µl of PBS.

Cell numbers and viability were determined via hemocytometer using a 0.4% trypan blue solution (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were spun onto slides (1.5 × 103 cells/slide) using a Shandon Cytospin (Thermo Shandon, Inc., Pittsburg, Pennsylvania). Slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for cell differential analysis. A total of 500 cells per slide were counted to determine macrophage, neutrophil, eosinophil, and lymphocyte cell composition of the BAL. All analyses on the BAL cells were blind.

Lung histopathology

From each mouse, the left lung lobe was collected and inflation-fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, Pennsylvania) at 30-cm water pressure for a minimum of 1 h, and subsequently stored in 4% paraformaldehyde until tissue processing. The fixed left lung was sagittally cut into 4 slices (levels). Each slice was dehydrated and embedded in a paraffin block for use with histopathological and immunohistochemical assays. Five-micron thick tissue sections were cut from each of the 4 lung levels with a microtome, mounted on glass slides, and stained with H&E and alcian blue/periodic acid-Schiff (AB/PAS).

Tissue sections were evaluated for inflammation and mucus using a categorical numeric scoring system of 0–4, as described elsewhere (Massoud et al., 2016), with modifications. All histopathology evaluations were done blind, and scores were averaged for each animal. In general, inflammation was evaluated throughout the parenchyma of each lung level, and for an average of 10 individual airways. For each level of the lung examined, individual airway scores were based on the following: no inflammation (0); presence of mild inflammation (1); moderate inflammation around a bronchiole (2); marked inflammation around a bronchiole (3); and inflammation extending beyond the bronchiole (4). The rubric for these scores is shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

The abundance of stored mucosubances (based on AB/PAS staining) was also evaluated using a numeric scoring system of 0–4. Scores were given based on the following: no evidence of AB/PAS stained cells (0); occasional AB/PAS-stained cells found in 1 airway (1); occasional AB/PAS-stained cells found in more than 3 airways (2); abundant AB/PAS-stained cells in more than 3 airways (3); and abundant AB/PAS stained cells and AB/PAS stained mucus plugs present in the airway lumen (4). The rubric for the AB/PAS scores is shown in Supplementary Figure 2.

Lung immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical evaluation was performed as described elsewhere (Castañeda and Pinkerton, 2016). For each mouse, 3-mm thick tissue sections from each of the 4 paraffin-embedded lung levels were cut with a microtome, mounted on glass slides, and incubated with primary antibodies to CD4 (Abcam; ab183685) and IL-17 (Abcam; ab79056). TH17 cells are a distinct subset of CD4+ T cells, and have been suggested to play an important role in regulating immunity associated with severe asthma. IL-17 is the primary cytokine secreted by TH17 cells, and has been immunolocalized to neutrophils (Brodlie et al., 2011), macrophages (Brodlie et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2012), and nasal polyp epithelial cells (Xia et al., 2014), which express IL-17 receptors. A horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled antirabbit polymer secondary antibody (DAKO EnVision System) was used with a 3, 3’-diaminobenzidine substrate chromogen system (Agilent, Santa Clara, California). Tissue sections were then counterstained with hematoxylin and coverslipped for examination.

Four random pictures were taken per lung level, for a total of 16 pictures per mouse, using brightfield microscopy (400×). Image J software (National Institutes of Health) was used to examine positive cells, total cells (denominator), and surface area in all 16 pictures/mouse. Cells were identified as being positive (+) or unstained for CD4 and IL-17 to derive the percentages of CD4+ and IL-17+ cells within focal areas of the highest cellular inflammation in each level. In total, 125 cells were counted in each picture by viewing nuclei. Thus, 500 cells were counted per level, and a total of 2000 cells were counted per mouse (500 cells/level × 4 levels/mouse = 2000 cells per mouse). There were no significant differences in surface area among the 6 animal groups (n = 6/group).

Circulating immunoglobulins in blood serum

Serum samples were collected from all mice at necropsy via cardiac puncture for measurement of nonspecific immunoglobulin E (IgE), HDM-specific IgE, and HDM-specific IgG1. High serum IgE production is key in the development of allergic asthma (Pelaia et al., 2017). IgG1 plays a role in immediate-onset pulmonary hypersensitivity responses (Griffiths-Johnson et al., 1993). Serum levels of nonspecific IgE were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol (BioLegend, San Diego, California). To assess HDM-specific IgE and IgG1 levels in the serum, ELISA plates were coated with 50 µg/ml HDM overnight at 4°C, and incubated with diluted serum (1:2 IgE or 1:10 IgG1; eBioscience, San Diego, California). Antibodies were detected using biotin-conjugated antimouse IgE and HRP-conjugated antimouse IgG1 (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, Alabama). Protein levels were analyzed in duplicate for each animal.

Measurement of cytokine and chemokine protein concentrations in the lung

The middle lobe of the right lung was homogenized with a cell lysis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California). The total protein concentration was assessed via Lowry protein assay (Bio-Rad). Mouse IL-17A and IL-17F (BioLegend) proteins in lung homogenate were determined using commercially available ELISA sets. ELISAs were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All samples and standards were measured in duplicate, standardized to total lung protein, and expressed as picograms of cytokine per milligram of lung tissue (pg/mg).

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

Total ribonucleic acid (RNA) was isolated from the right caudal lung lobe of each mouse using a Quick-RNA MiniPrep Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, California), and converted to copy deoxyribonucleic acid (cDNA) using a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California) to prevent degradation in storage at −20°C. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed on a Roche LightCycler 480 using SYBR Green I Master (Roche, Indianapolis, Indiana), and mouse-specific PCR primers were applied for the following genes: Muc5ac; IL-17A, -17F, -21, -22, and -27; CXCL-1, -2, and -10; CCL-1, -2, and 7; G-CSF; GM-CSF; and MMP1, 2, 3, and 9. The primers for each gene were designed on the basis of the respective mRNA sequences using OLIGO primer analysis software provided by Steve Rozen and the Whitehead Institute/MIT Center for Genome Research (Rozen and Skaletsky, 2000). Pulmonary Muc5ac expression is associated with goblet cell hyperplasia and mucus production in allergic airway disease (Evans et al., 2015). IL-27 has been shown to inhibit TH17 cell production of IL-17 and suppress other TH17-related cytokines like IL-21 and -22 (Liu and Rohowsky-Kochan, 2011). IL-17 induces expression of CXCL-1, CXCL-2, CXCL-10, CCL-1, CCL-2, and CCL-7 neutrophil chemoattractants (Veldhoen, 2017); recruits immune cells through induction of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) like MMP-1, -2, -3, and -9 (Khokha et al., 2013; van Nieuwenhuijze et al., 2015); and can also modulate responses of recruited cells, for example, through induction of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), which promotes expansion and enhances survival of neutrophils and macrophages (Parsonage et al., 2008).

Gene expression (mRNA) was assessed using the (ΔΔ-Ct) method (Hellemans et al., 2007), and standardized to the expression of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), which was used as a housekeeping gene. Single-amplicon quality was verified by melting curve analysis. Relative gene expression was calculated using the ΔΔ-Ct method normalized to GAPDH. Primers used in this study are detailed in Supplementary Table 1.

Statistical methods

Presence of outliers was tested for bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) data using scattergraphs in SSPS software (version 17.0). No outliers were found; however, 4 animals were excluded from the PBS group for all measured endpoints to ensure equal group sizes (n = 6/group). All other statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, California). All treatment groups were compared by 1-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey’s multiple comparison test. All data were expressed as means ± SEM. A value of p < .05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Composition of PMCA and PMCH

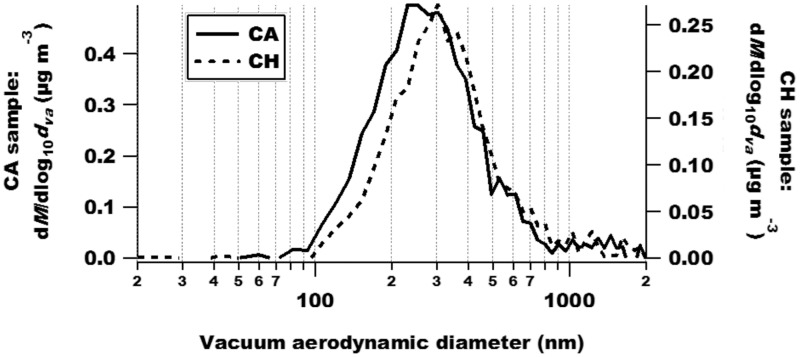

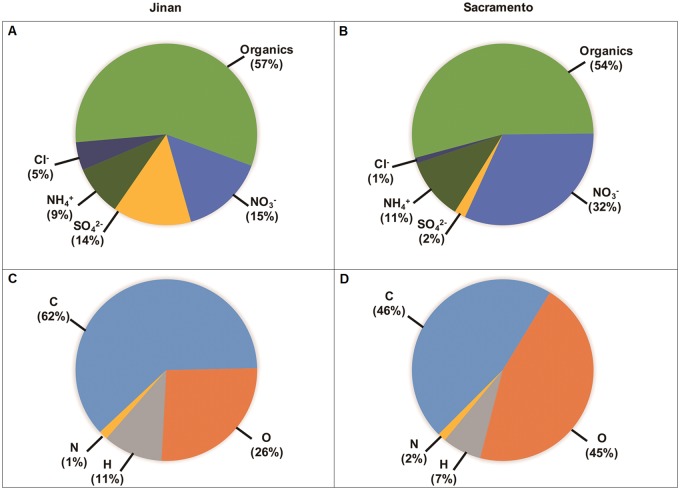

HR-AMS results indicated that the size of particulates in the silica gel-dried PM samples was ≤ 2 µm (Figure 2). PMCA and PMCH consisted largely of organic compounds (54% and 57% of total PM mass, Figs. 3B and 3A, respectively). However, organic matter in PMCA was more oxidized (45% oxygen; Figure 3D) than in PMCH (26% oxygen; Figure 3C) on a mass basis. Another major difference between the 2 PM extracts was that PMCA had a much greater percent of NO3− (32%) and lower percent of (2%) by mass (Figure 3B) versus PMCH (15% and 14%, respectively; Figure 3A). PMCA and PMCH contained a wide range of elements as indicated by ICP-MS (Table 1); however, these elements differed in concentration. In particular, the concentration of Cu was much higher in the former versus the latter (2.13 vs. 0.119 parts per million (ppm), respectively; a 17.9-fold difference) as was that of Fe (1.12 vs. 0.337 ppm, respectively; a 3.3-fold difference) to a lesser degree.

Figure 2.

HR-AMS results show that extracts of PMCA and PMCH have similar size distributions. In general terms, the graph shows the change in particle mass concentration as a function of particle size. The mass-weighted size distributions are on the y-axes, and the vacuum aerodynamic diameter is on the x-axis. In the y-axes, “dM” denotes the change in mass, and “dva” represents the change in the vacuum aerodynamic diameter.

Figure 3.

The average chemical composition of wintertime PM from Jinan, China, and Sacramento, California. Characterization was done by high-resolution time-of-flight aerosol mass spectrometry. Top pie charts (A, B) illustrate bulk PM composition, including organics. Bottom pie charts (C, D) show elemental composition.

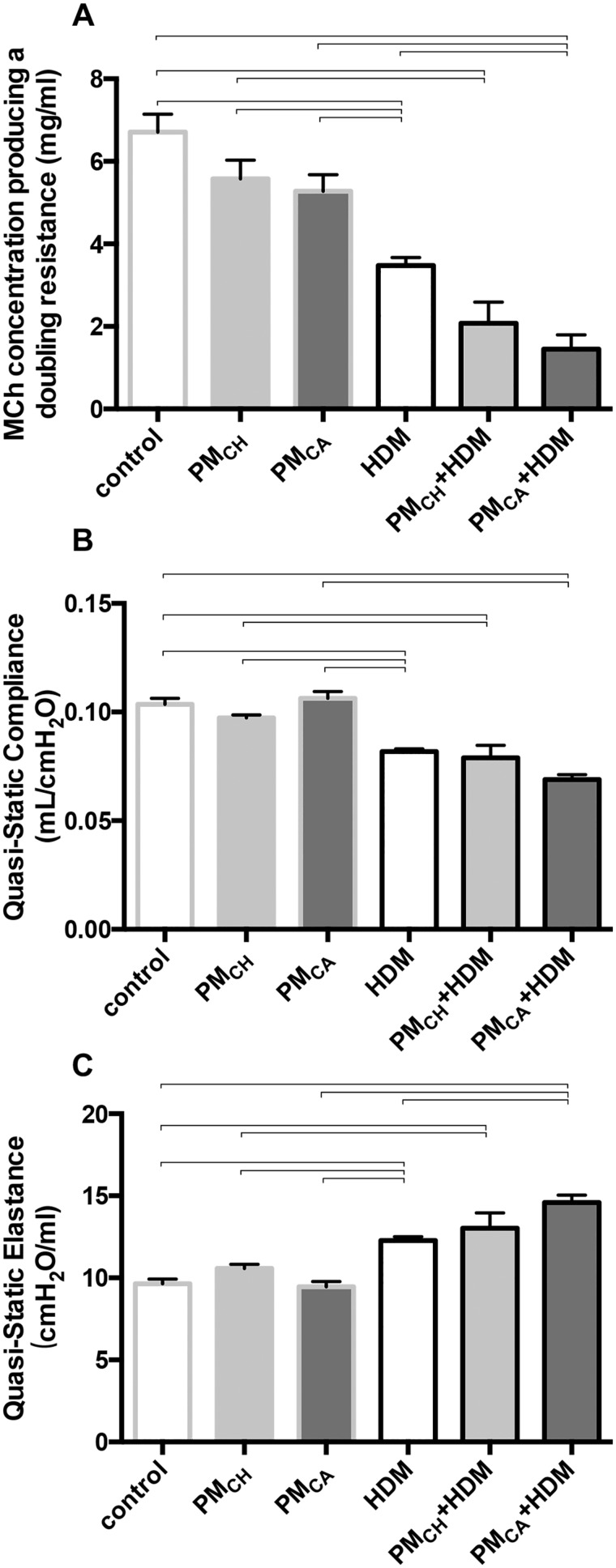

PMCA Exposure Exacerbated Airway Hyper-Reactivity and Impaired Pulmonary Function in HDM-Sensitized Mice

No significant (p < .05) differences were observed between PBS, PMCA, and PMCH mice with respect to the EC200RL (Figure 4A) suggesting that exposure to PM alone was insufficient to produce AHR. However, mice exposed to HDM, PMCA+HDM, or PMCH+HDM exhibited moderately increased AHR with increasing doses of MCh when compared with control (PBS) mice. This hyper-responsiveness was evinced in the significantly (p < .05) lower MCh concentrations required to double airway resistance in HDM, PMCA+HDM, and PMCH+HDM mice versus PBS controls (Figure 4A). Although there were no significant (p < .05) differences in the EC200RL between PMCA+HDM and PMCH+HDM mice, the former had a significantly (p < .05) decreased EC200RL (2.30-fold) when compared with HDM-exposed mice, while the latter did not (Figure 4A). These results suggest PMCA (but not PMCH) exposure significantly exacerbated airway responsiveness induced by HDM. Significantly (p < .05) different groups reported above for the EC200RL, were the same in lung elastance tests (Figure 4C). However, while EC200RL appeared to decrease, lung elastance increased. Lung compliance was significantly decreased in HDM, PMCA+HDM, and PMCH+HDM mice in comparison to their PBS-exposed counterparts, but not between any of the HDM-exposed groups. Nonsignificant, downwardly trending EC200RL results in PMCH+HDM mice, and lung compliance results in the PMCA+HDM mice suggest that increasing the sample size in future experiments may enable detection of significant (p < .05) differences from the HDM group. Overall, these results suggest that the combined exposure to PM+HDM produced AHR and difficulty breathing similar to episodes of acute asthma. Decreased lung compliance and increased elastance are indicative of stiffer lungs that require extra work to expand during the inhalation breath. During episodes of asthma, airways constrict, restrict outward airflow, and trap air in the lungs. Because the lungs are already inflated, compliance is low. Although HDM alone was sufficient to produce these asthmatic effects, PMCA appeared to exacerbate them in HDM-exposed animals.

Figure 4.

Pulmonary function measurements. Graphs show results of mice intranasally instilled with PBS (control), PMCH, PMCA, and/or HDM allergen. A, Concentration of MCh required to double airway resistance (EC200RL). B, Quasi-static lung compliance. C, Quasi-static lung elastance. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Brackets indicate a significant (p < .05) difference between groups. “Control” animals were instilled with PBS alone during sensitization and challenge periods. EC200RL, lung compliance, and lung elastance means were calculated from 10, 3, and 3 measures per mouse, respectively (n = 6 for all treatment groups).

PM Exposure Increased Pulmonary Inflammation in HDM-Sensitized Mice

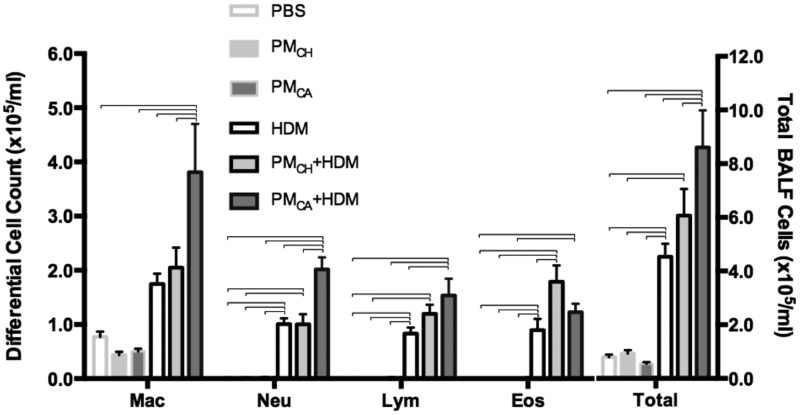

Airway inflammation was evaluated partly by the number of macrophages, eosinophils, neutrophils, and lymphocytes recovered via BAL (Figure 5). Significant (p < .05) increases in the total cells, eosinophils, neutrophils, and lymphocytes (but not macrophages) occurred in HDM, PMCA+HDM and PMCH+HDM mice relative to PBS, PMCA, and PMCH mice. There were also significant (p < .05) increases in macrophage, neutrophil, and lymphocyte numbers in PMCA+HDM mice compared with HDM and PMCH+HDM mice (macrophages and neutrophils only). In contrast, eosinophil numbers were significantly (p < .05) increased in PMCH+HDM versus HDM mice. Although there were no significant differences in eosinophil numbers observed between PMCA+HDM and HDM mice in the present study, increasing the sample size in future experiments may increase statistical power to enable detection of significant (p < .05) differences.

Figure 5.

Cells collected from BALF. Total numbers and differential counts of BAL cells stained with H&E are shown. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Brackets indicate a significant (p < .05) difference between groups. Abbreviations: Mac, macrophages; Neu, neutrophils; Lym, lymphocytes; Eos, eosinophils (n = 6 for all treatment groups).

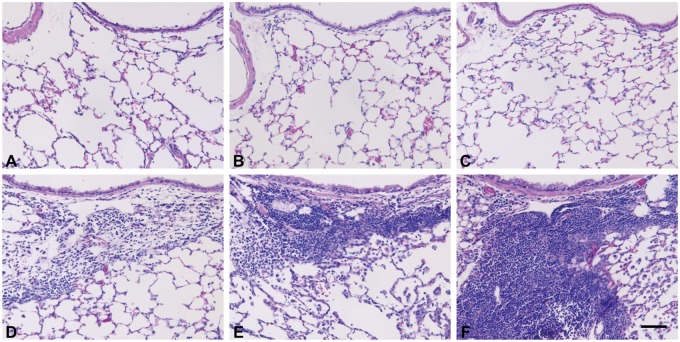

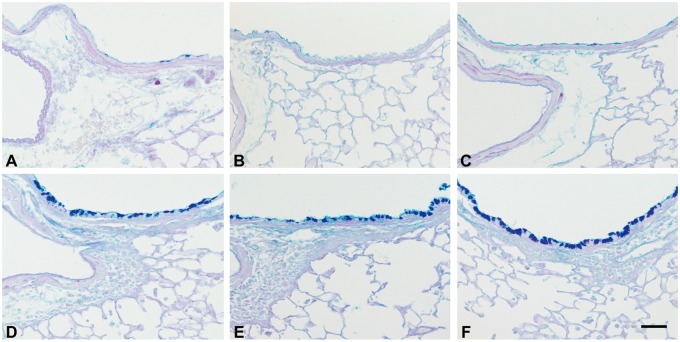

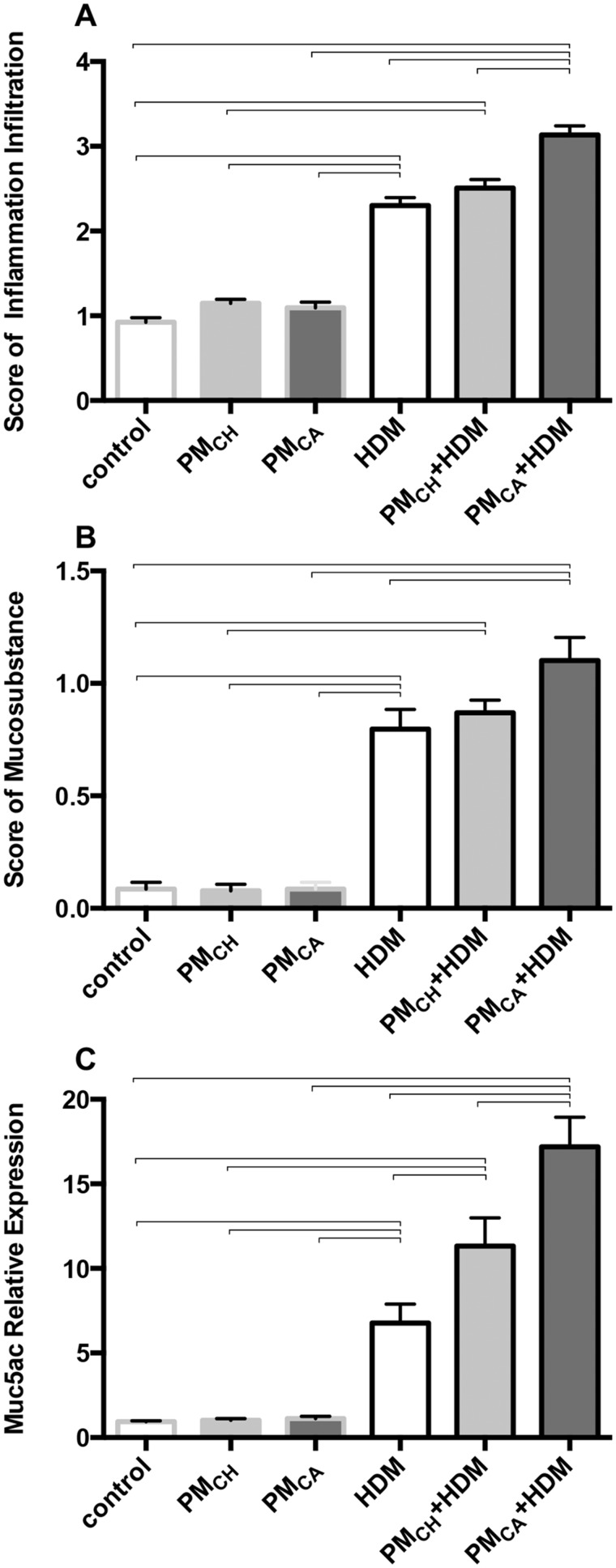

When compared with the PBS-treated mice (PBS control, PMCH, and PMCA), the HDM-challenged groups (HDM, PMCA+HDM and PMCH+HDM) displayed typical pathologic features of allergic airway inflammation such as numerous inflammatory cells in the bronchioles and adjacent perivascular regions (Figs. 6D–F), and mucus lining the airways (Figs. 7D–F). This was especially true for the PMCA+HDM mice, which had significantly (p < .05) increased inflammation, mucosubstance, and Muc5ac gene expression compared with HDM and PMCA mice (Figs. 8A–C, respectively). PMCH+HDM mice did not have the same response; only Muc5ac expression was significantly (p < .05) greater than in HDM mice (Figure 8C).

Figure 6.

PM exacerbates the airway inflammation produced by HDM allergen. Panels are brightfield microscopy images of typical responses observed in mouse lung tissue sections stained with H&E. Images show the following treatment groups: PBS (control; A); extracts of PMCH (B); extracts of PMCA (C); HDM (D); PMCH+HDM (E); and PMCA+HDM (F). Scale bar is 50 μm (n = 6 for all treatment groups).

Figure 7.

Mice treated with HDM allergen or PM+HDM have visibly increased levels of airway mucosubstances. Panels are brightfield microscopy images of typical responses observed in mouse lung tissue sections stained with AB/PAS. Mucosubstances appear as dark staining along the airway. Images show the following treatment groups: PBS (control; A); extracts of PMCH (B); extracts of PMCA (C); HDM (D); PMCH+HDM (E); and PMCA+HDM (F). Each group had an n = 6.Scale bar is 50 μm.

Figure 8.

The combination of PM and HDM allergen produces significantly more airway inflammation and mucus than all other treatments. Graphs show semiquantitative scoring results for airway inflammation (A), mucosubstances (B), and Muc5acs gene expression (C). Results are from 1-way ANOVAs considering the effect of treatment. Data in these panels are shown as the mean ± SEM, and brackets indicate a significant (p < .05) difference between groups (n = 6 for all treatment groups).

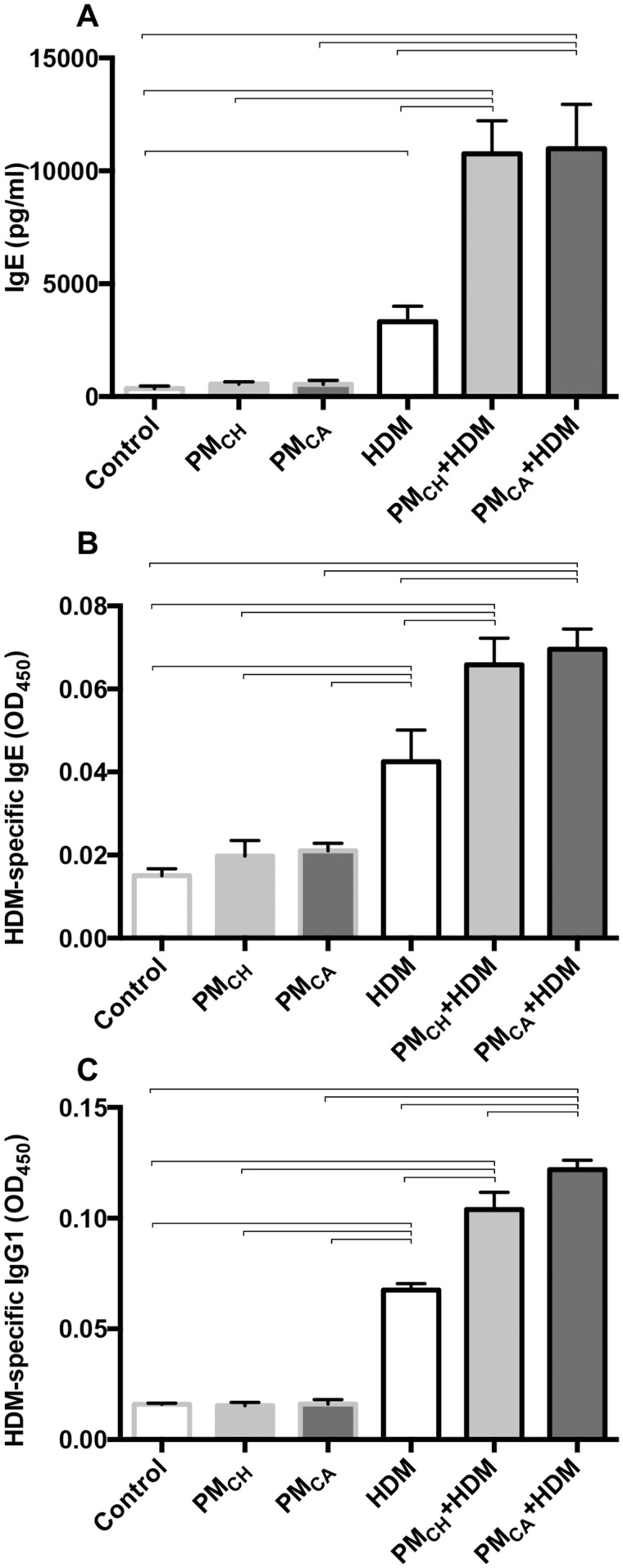

PM Exposure Exacerbated Systemic and Airway Ig Secretion in HDM-Exposed Mice

Serum levels of nonspecific IgE, HDM-specific IgE, and HDM-specific IgG1 (Figs. 9A–C, respectively) were significantly (p < .05) elevated in the HDM-challenged groups versus their PBS counterparts, and in the PM+HDM versus HDM groups. Nonspecific serum IgE levels were increased 3.31-fold in PMCA+HDM mice, and 3.24-fold in PMCH+HDM mice compared with HDM mice (Figure 9A). HDM-specific IgE (Figure 9B) was 1.64- and 1.55-fold greater, and HDM-specific IgG1 (Figure 9C) was 1.80- and 1.54-fold greater in PMCA+HDM and PMCH+HDM mice, respectively, versus HDM mice. PMCA+HDM mice also had significantly (p < .05) greater serum HDM-specific IgG1 than PMCH+HDM mice (Figure 9C).

Figure 9.

Ig protein levels measured in blood serum by ELISA. Panels show nonspecific IgE levels (A), HDM-specific IgE levels (B), and HDM-specific IgG1 levels (C). Protein levels were analyzed in duplicate for each animal and averaged for each treatment group. Data were analyzed by ANOVAs considering the effect of treatment, and are shown as the mean ± SEM. Brackets indicate a significant (p < .05) difference between groups (n = 6 for all treatment groups).

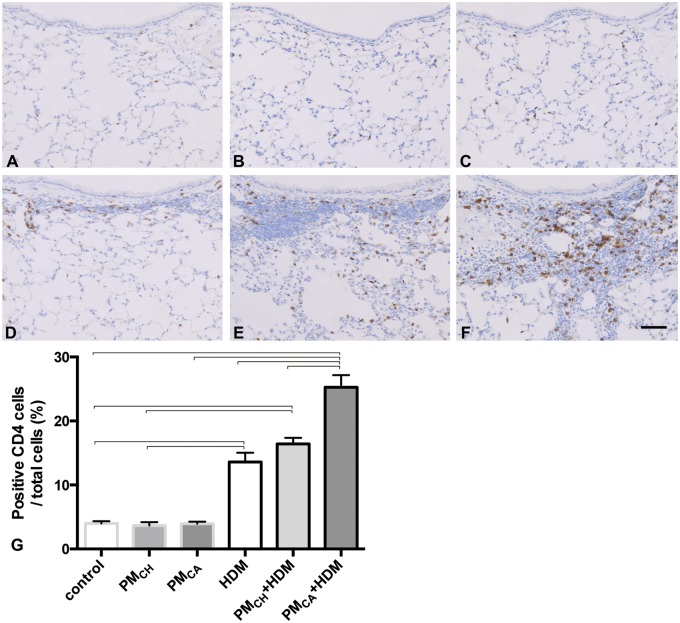

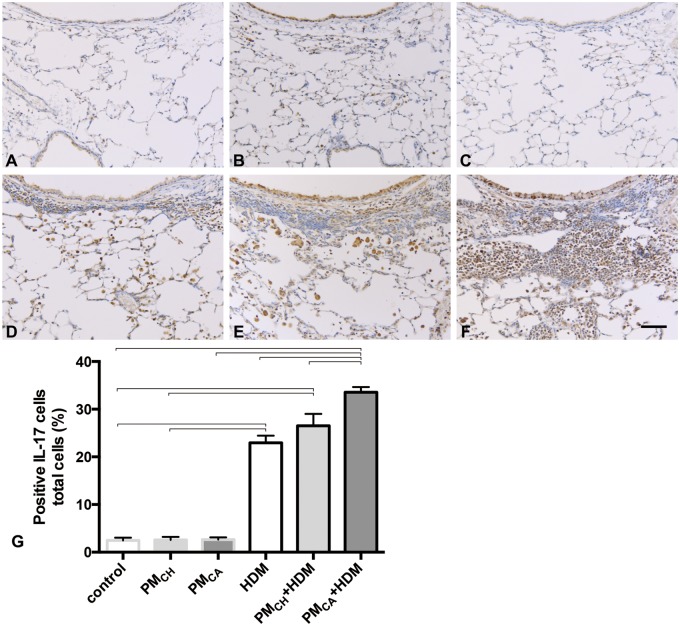

PM Exposure Enhanced the Development of TH17 Immune Responses in HDM-Exposed Mice

Immunohistochemical staining revealed CD4+ (Figure 10) and IL-17+ (Figure 11) cells located around airways and in the lung parenchyma with PM and/or HDM exposure. PMCA+HDM mice had a significantly greater percent of CD4+ and IL-17+ cells (Figs. 10G and 11G, respectively) than HDM or PMCH+HDM mice. The IL-17 likely stained activated TH17-cells, and IL-17-bound cells with IL-17 receptors (eg, neutrophils, macrophages, and epithelial cells). It is possible that necrotic death of IL-17-bound cells may also have contributed to the tissue staining.

Figure 10.

Exposure to California PM and HDM allergen (PMCA+HDM) produces the strongest influx of CD4-positive cells into the lungs. Panels (A–F) are brightfield microscopy images of typical responses observed in mouse lung tissue sections stained for CD4 markers of T-helper type 17 (TH17) cells. CD+ cells appear as dark staining. Images show the following treatment groups: PBS (control; A); extracts of PMCH (B); extracts of PMCA (C); HDM (D); PMCH+HDM (E); and PMCA+HDM (F). Each group had an n = 6. Scale bar is 50 μm. Panel G shows the percent of CD4+ cells. Data were analyzed by an ANOVA considering the effect of treatment, and are shown as the mean ± SEM. Brackets indicate a significant (p < .05) difference between groups.

Figure 11.

Exposure to California PM and HDM allergen (PMCA+HDM) produces the strongest influx of IL-17-positive cells into the lungs. Panels (A–F) are brightfield microscopy images of typical responses observed in mouse lung tissue sections stained for IL-17 markers of T-helper type 17 (TH17) cells. IL-17+ cells appear as dark staining. Images show the following treatment groups: PBS (control; A); extracts of PMCH (B); extracts of PMCA (C); HDM (D); PMCH+HDM (E); and PMCA+HDM (F). Each group had an n = 6. Scale bar is 50 μm. Panel (G) shows the percent of IL-17+ cells. Data were analyzed by an ANOVA considering the effect of treatment, and are shown as the mean ± SEM. Brackets indicate a significant (p < .05) difference between groups.

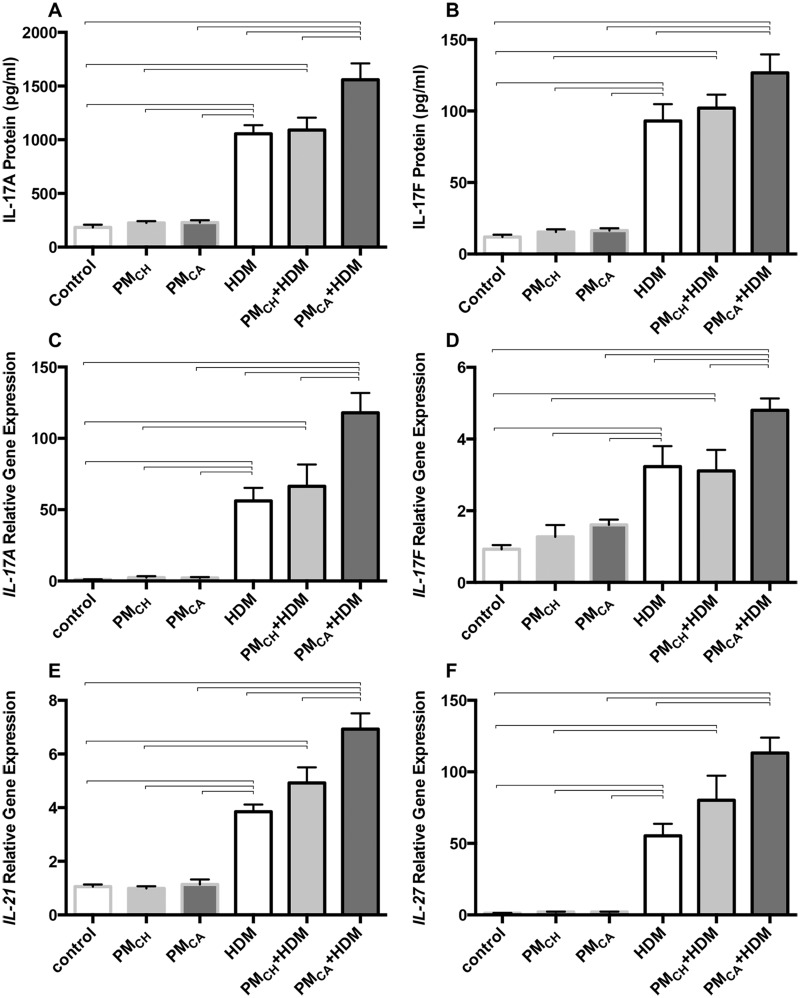

Expression of TH17-related pulmonary cytokine proteins and genes were determined in response to the high number of BAL neutrophils found in PMCA+HDM mice (Figure 12). When compared with HDM and/or PMCH+HDM mice, PMCA+HDM mice expressed significantly (p < .05) higher protein levels of IL-17A (Figure 12A), and IL-17F (versus HDM only; Figure12B), as well as increased mRNA levels of IL-17A (Figure 12C), IL-17F (Figure 12D), IL-21 (Figure 12E) and IL-27 (vs. HDM only; Figure 12F). These differences were not found between HDM and PMCH+HDM mice. Especially given IL-17A gene expression, which was increased 56- and 118-fold above PBS controls in HDM and PMCA+HDM mice, respectively (Figure 12C), the data suggest that PMCA contributes to the development of a TH17 immune response in HDM-exposed mice even when IL-27 is also elevated. IL-27-mediated crosstalk may partially explain this somewhat paradoxical result, as it has been shown to suppress TH17-related cytokines (Liu and Rohowsky-Kochan, 2011), induce TH17 differentiation (Nurieva et al., 2007), and facilitate eosinophil accumulation (Hu et al., 2011) in different signaling cascades.

Figure 12.

Exposure to California PM and HDM allergen (PMCA+HDM) significantly increases the protein and gene expression profiles of T-helper cell type 17 (TH-17)- cytokines above other treatments. Graphs show results obtained from analysis of mouse lung proteins via ELISA and genes (mRNA) via PCR. Analyzed proteins included IL-17A (A) and IL-17F (B). Protein levels were analyzed in duplicate for each animal and averaged for each treatment group. Analyzed genes included IL-17A (C), IL-17F (D), IL-21 (E), and IL-27 (F). Gene expression is shown as relative expression to the housekeeping gene, GAPDH. Gene levels were analyzed for each animal and averaged for each treatment group. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM. Brackets indicate a significant (p < .05) difference between groups (n = 6 for all treatment groups).

IL-17 and Neutrophil-Related Cytokines Increase Following PM Exposure During Allergic Sensitization

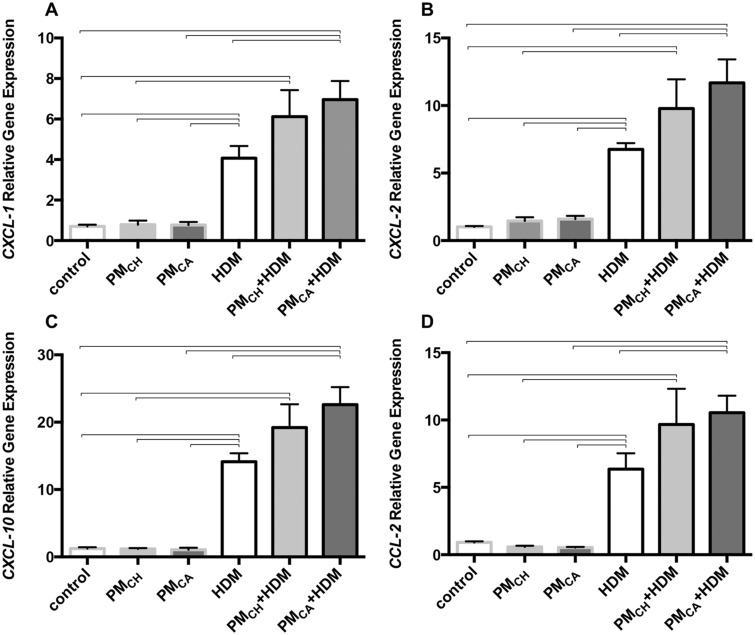

IL-17 induces the expression of key neutrophil and monocyte chemoattractants, such as CCL2, CXCL-1, -2, and -10 (Manni et al., 2014). Gene expression of CXCL-1, -2 and -10 and CCL2 (Figs. 13A–D, respectively) was significantly (p < .05) elevated in the lungs of HDM-challenged mice versus their PBS counterparts, and in PMCA+HDM versus HDM mice. This latter change in expression patterns was not found for the PMCH+HDM group. No differences among groups were found for MMP-1, -2, -3, and -9 or G-CSF and GM-CSF (data not shown).

Figure 13.

Exposure to California PM and HDM allergen (PMCA+HDM) significantly increases the gene expression profiles of T-helper cell type 17 (TH-17)-associated neutrophil chemoattractants above other treatments. Graphs show results obtained from analysis of mouse lungs via PCR. Analyzed genes (mRNA) included CXCL-1 (A), CXCL-2 (B), CXCL-10 (C), and CCL-2 (D). Gene expression is shown as relative expression to the housekeeping gene, GAPDH. Gene levels were analyzed in triplicate for each animal and averaged for each treatment group. Data are shown as the mean ± SEM. Brackets indicate a significant (p < .05) difference between groups (n = 6 for all treatment groups).

DISCUSSION

Chemical Differences Between PMCA and PMCH Contributed to Contrasting Inflammatory Responses

Although air pollution is significantly higher in China, asthma prevalence is approximately 3-fold greater in the United States (Fu et al., 2016; Ryan-Ibarra et al., 2016). Research suggests asthma is influenced by environment and genetics (Chen et al., 2016). Therefore, combined effects of PM exposure and genetic polymorphisms likely contribute to lower asthma prevalence in Jinan versus Sacramento.

In this study, we determined PMCA enhanced HDM-induced allergic airway inflammation to a greater extent than PMCH (Figs. 4A, 5, 6F, 7F, 8A–C, 9B, and 9C). PMCA+HDM also produced a neutrophil-activating TH17 cytokine response (Figs. 10F, 11F, 12, and 13) in the lung rather than eosinophilic inflammation, which was observed in PMCH+HDM mice (Figure 5).

Although PM sampling occurred on different continents, the study design fostered a cohesive set of protocols. Samples were collected during winter, when PM concentrations tend to be higher than summer. Higher winter PM concentrations are due to fuel combustion heating of buildings, and meteorological conditions that allow pollutants to accumulate and concentrate (Wang et al., 2016). Winter periods are associated with increased hospital admissions and incidence of cardiovascular and respiratory disease (Guan et al., 2016).

PM characterization suggested similar emission sources were present in Jinan and Sacramento during winter. These sources included fossil fuels used for heating and transportation (gasoline and diesel emissions, traffic-related air pollutants), cooking, and agricultural production. Chemical analyses of Jinan and Sacramento PM samples revealed the Cu, Fe, and oxidized organic concentrations were much higher in PMCA versus PMCH. A previous study by our lab (Sun et al., 2017) suggested the greater inflammatory effects (ie, BALF neutrophils and lung CXCL-1) observed in mice upon acute exposure to PMCA versus PM from Taiyuan, China (PMTY) was due in part to a difference in Cu content. Sun et al. (2017) reported Cu and oxidized organic content were 24-times and 10% higher, respectively, in PMCA versus PMTY, while Fe content was equal. In the present study, Cu, Fe, and oxidized organic content were approximately 18-times, 3.3-times, and 19% higher, respectively, in PMCA versus PMCH. The confluence of results from the 2 studies suggests that Cu and oxidized organic content may be driving the differential patterns of inflammation observed.

Cu is a transition metal that can reduce oxygen to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS; Charrier et al. 2014). Oxidized organics in PM are strongly linked to inflammatory responses (Liu et al., 2014) and ROS generation (Ghio et al., 1996; Verma et al., 2015). Complexation of metals by oxidized organics can result in lipid-soluble, membrane-permeable products (Shinyashiki et al., 2009), and the imbalance of ROS and antioxidant defenses can result in oxidative stress and exacerbated asthma symptoms. ROS are major determinants of asthma severity (Sahiner et al., 2011). They can promote inflammatory cell influx across the endothelium into the lungs (Mittal et al., 2014); activate signaling cascades leading to goblet cell metaplasia and mucus hypersecretion (Casalino-Matsuda et al., 2006); or effect epithelial cell apoptosis and inactivation of antioxidant enzymes (Qu et al., 2017). In vitro studies suggest ROS can induce calcium (Ca2+) sparks, which may result in increased airway smooth muscle cell contractility and AHR in sensitized animals (Tuo et al., 2013). In the present study, neutrophilia (Figure 5), subepithelial lung inflammation (Figure 8A), Muc5ac lung expression (Figure 8C), and AHR (Figure 4A) were all significantly increased (p ≤ .05) in PMCA+HDM versus PMCH+HDM and/or HDM mice. Given that activated alveolar macrophages and neutrophils have been shown to generate stronger respiratory bursts (ie, more ROS) in asthmatic versus nonasthmatic subjects, and ROS generation has been correlated to AHR, additional ROS from inhaled Cu and oxidized organic complexes could further unbalance redox homeostasis and increase oxidative stress and asthma symptomatology (Nadeem et al., 2008).

PMCA Potentiated Allergic Asthma Responses in HDM-Exposed Mice

Inflammation, decreased lung function, airway alterations, and increased IgE/IgG and mucus secretion are hallmarks of asthma. Alterations in AHR, compliance, and elastance have been attributed to direct effects on airway remodeling and contractility (Chesne et al., 2015). Elevated IgE, IgG1, and mucus are strongly associated with the development of allergic hypersensitivity (Sibilano et al., 2016). In the present study, PMCA+HDM treatment resulted in significant (p < .05) lung neutrophilia; (Figure 5); lung function decrements (Figure 4); and mucus, HDM-specific IgE, and HDM-specific IgG increments (Figs. 7, 8B, and 8C; 9B; and 9C, respectively) relative to HDM. These findings suggest exposure to PMCA during HDM allergen sensitization contributed to development of AHR.

Although much of the allergic asthma research on PM has focused on TH2-dominant eosinophilic disease, in the present study, neutrophilia appeared to be directly related to PMCA exposure. Neutrophils were increased in BALF (Figure 5) and the subepithelium of airways (Figs. 6 and 8A) in PMCA+HDM, but not PMCH+HDM, mice compared with HDM and PMCA groups.

TH17-Associated Cytokines Influenced Asthmatic Effects Observed in HDM and PMCA+HDM Mice

Studies suggest pulmonary TH17 cytokine levels in asthmatics predominantly correlate with AHR incidence and asthma severity (Halwani et al., 2017; Veldhoen, 2017). Despite associations between TH17 cytokines and severe asthma, little is known about the regulation of TH17 cytokine production in air pollution-associated asthma, or the mechanisms by which TH17 cytokines drive severe disease. We hypothesized increased susceptibility to AHR was associated with more production of TH17-associated cytokines (IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-22, and IL-21). PMCA was found to promote HDM-induced asthma, resulting in increased protein and gene production of IL-17 (Figs. 11F–G, and 12A–D). In a study of IL-17A-related asthma (Halwani et al., 2017), neutralizing antibodies to IL-17A homodimers strongly blocked neutrophilic airway inflammation mediated by adoptive transfer of ovalbumin-specific polarized TH17 cells and airway challenge with antigen (Liang et al., 2007). In this study, positive staining for IL-17 was significantly increased in PMCA+HDM versus HDM mice (Figure 11G). IL-17F shares the greatest homology (55%) with IL-17A and is also produced by TH17 cells (Dubin and Kolls, 2009). IL-17 actively participates in inducing expression of pro-inflammatory neutrophil and monocyte chemoattractants like CCL-2, CXCL-1, CXCL-2, and CXCL-10 (Manni et al., 2014; Veldhoen, 2017), which were elevated in PMCA+HDM mice compared with HDM and PMCH+HDM mice (Figure 13) in the present study. Although IL-17 also recruits and mediates responses of immune cells through induction of MMPs, G-CSF, and GM-CSF, their levels were not significantly different among the various treatment groups.

PMCA Exposure Results in Increased IL-21, an Upstream Cytokine That Promotes TH17 Responses, in HDM-Sensitized Mice

The combination of IL-21 and transforming growth factor-β can induce naive T cells to differentiate into TH17 cells (Veldhoen, 2017). We found that IL-21 was significantly increased in PMCA+HDM mice compared with HDM and PMCH+HDM mice (Figure 12E). Several studies suggest IL-21, a pleiotropic cytokine capable of activating most lymphocyte populations (Parrish-Novak et al., 2000), is produced by IL-27-induced transcription factor c-Maf (Pot et al., 2009). IL-27 expression is reportedly significantly greater in sputum from patients with severe neutrophilic asthma (Li et al., 2010). Because TH17 cells are a major source of IL-21, an autocrine amplification loop has been proposed by which TH17 cells enhance their own differentiation and precursor frequency (Nurieva et al., 2007). Researchers found that TH17 cells produced IL-21, which exerted critical functions in TH17 cell development (Ouyang et al., 2008). It is possible that PM2.5 activates dendritic cells and/or macrophages to produce and secrete IL-27, which then increases IL-21 levels to induce the differentiation of TH17 cells. This may be a key mechanism in PM-related allergic sensitization. In the present study, we observed elevated IL-27 in PMCA+HDM mice compared with HDM-treated mice (Figure 12F).

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first of its kind to compare how exposure to different sources of PM contributes to allergic sensitization, challenge, and neutrophilic inflammation in asthma. Future studies may benefit from comparative analysis of equivalent doses of PMCH, PMCA, and specific components thereof (eg, Cu ions and/or oxidized organics). We conclude that: (1) low-dose PM2.5 extracts can significantly exacerbate asthmatic responses in HDM-sensitized animals (Figure 4); (2) toxicity of PMCA+HDM is greater than PMCH+HDM (Figs. 5, 6E, 6F, 8A, and 8C); (3) PMCA exposure during the period of allergic sensitization to HDM significantly increases levels of TH17-associated cytokines (IL-17A, -17F, and IL-21; Figs. 12A–E) and IL-17-enhanced chemokines (CCL2, CXCL1, 2, and 10) involved in neutrophil (not eosinophil) recruitment (Figs. 13A–D; (4) IL-21 is a plausible activator of TH17 cytokines (Figure 12E); and (5) higher levels of oxidized organic compounds and Cu in PMCA may be partly responsible for its greater toxicity (Figure 3 and Table 1, respectively).

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at Toxicological Sciences online.

FUNDING

This work was supported the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health [grant number OHO7550]; and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences [grant numbers P30 ES023513, P51 OD011107, and R01 ES019898]; in addition to a scholarship from the Chinese Ministry of Education’s China Scholarship Council (CSC).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Imelda Espiritu, Dale Uyeminami, Sarah Kado, and Janice Peake for technical assistance during the course of this study. Special thanks to Dr Rona Silva for help with comprehensive technical editing of this article, as well as Dr Laura Van Winkle and Patti Edwards for use of the Cellular and Molecular Imaging (CAMI) Core at the Center for Health and the Environment.

REFERENCES

- Aiken A. C., Decarlo P. F., Kroll J. H., Worsnop D. R., Huffman J. A., Docherty K. S., Ulbrich I. M., Mohr C., Kimmel J. R., Sueper D., et al. (2008). O/C and OM/OC ratios of primary, secondary, and ambient organic aerosols with high-resolution time-of-flight aerosol mass spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 42, 4478–4485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ramli W., Prefontaine D., Chouiali F., Martin J. G., Olivenstein R., Lemiere C., Hamid Q. (2009). T(H)17-associated cytokines (IL-17A and IL-17F) in severe asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 123, 1185–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bein K., Wexler A. S. (2015). Compositional variance in extracted particulate matter using different filter extraction techniques. Atmos. Environ. 107, 24–34. [Google Scholar]

- Brodlie, M., McKean, M. C., Johnson, G. E., Anderson, A. E., Hilkens, C. M., Fisher, A. J., Corris, P. A., Lordan, J. L., and Ward, C. (2011). Raised interleukin-17 is immunolocalised to neutrophils in cystic fibrosis lung disease. Eur. Respir. J 37(6), 1378–1385. [DOI] [PubMed]

- California Health Interview Survey. 2012. UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, California Health Interview Survey, Los Angeles, CA.

- Canagaratna M. R., Jayne J. T., Jimenez J. L., Allan J. D., Alfarra M. R., Zhang Q., Onasch T. B., Drewnick F., Coe H., Middlebrook A., et al. (2007). Chemical and microphysical characterization of ambient aerosols with the aerodyne aerosol mass spectrometer. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 26, 185–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda A. R., Bein K. J., Smiley-Jewell S., Pinkerton K. E. (2017). Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) enhances allergic sensitization in BALB/c mice. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 80, 197–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda A. R., Pinkerton K. E. (2016). Investigating the effects of particulate matter on house dust mite and ovalbumin allergic airway inflammation in mice. Curr. Protoc. Toxicol. 68, 18–18.1–18.18.18.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casalino-Matsuda S. M., Monzón M. E., Forteza R. M. (2006). Epidermal growth factor receptor activation by epidermal growth factor mediates oxidant-induced goblet cell metaplasia in human airway epithelium. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 34, 581–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. (2017). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_data.htm. Last Accessed May 26, 2018.

- Charrier J., McFall A. S., Richards-Henderson N. K., Anastasio C. (2014). Hydrogen peroxide formation in a surrogate lung fluid by transition metals and quinones present in particulate matter. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 7010–7017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Wong G. W. K., Li J. (2016). Environmental exposure and genetic predisposition as risk factors for asthma in China. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 8, 92–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesne J., Braza F., Chadeuf G., Mahay G., Cheminant M. A., Loy J., Brouard S., Sauzeau V., Loirand G., Magnan A. (2015). Prime role of IL-17A in neutrophilia and airway smooth muscle contraction in a house dust mite-induced allergic asthma model. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 135, 1643. e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubin P. J., Kolls J. K. (2009). Interleukin-17A and interleukin-17F: A tale of two cytokines. Immunity 30, 9–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans C. M., Raclawska D. S., Ttofali F., Liptzin D. R., Fletcher A. A., Harper D. N., McGing M. A., McElwee M. M., Williams O. W., Sanchez E., et al. (2015). The polymeric mucin Muc5ac is required for allergic airway hyperreactivity. Nat. Commun. 6, 6281.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahy J. V. (2015). Type 2 inflammation in asthma–present in most, absent in many. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 57–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Q. L., Du Y., Xu G., Zhang H., Cheng L., Wang Y. J., Zhu D. D., Lv W., Liu S. X., Li P. Z., et al. (2016). Prevalence and occupational and environmental risk factors of self-reported asthma: Evidence from a cross-sectional survey in seven Chinese cities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 13, 1084–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghio A. J., Stonehuerner J., Pritchard R. J., Piantadosi C. A., Quigley D. R., Dreher K. L., Costa D. L. (1996). Humic-like substances in air pollution particulates correlate with concentrations of transition metals and oxidant generation. Inhal. Toxicol. 8, 479–494. [Google Scholar]

- Gold M. J., Hiebert P. R., Park H. Y., Stefanowicz D., Le A., Starkey M. R., Deane A., Brown A. C., Liu G., Horvat J. C., et al. (2016). Mucosal production of uric acid by airway epithelial cells contributes to particulate matter-induced allergic sensitization. Mucosal Immunol. 9, 809–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths-Johnson D., Jin R., Karol M. H. (1993). Role of purified IgG1 in pulmonary hypersensitivity responses of the guinea pig. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health 40, 117–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan W. J., Zheng X. Y., Chung K. F., Zhong N. S. (2016). Impact of air pollution on the burden of chronic respiratory diseases in China: Time for urgent action. Lancet 388, 1939–1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halwani R., Sultana A., Vazquez-Tello A., Jamhawi A., Al-Masri A. A., Al-Muhsen S. (2017). Th-17 regulatory cytokines IL-21, IL-23, and IL-6 enhance neutrophil production of IL-17 cytokines during asthma. J. Asthma 54, 893–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellemans J., Mortier G., De Paepe A., Speleman F., Vandesompele J. (2007). qBase relative quantification framework and software for management and automated analysis of real-time quantitative PCR data. Genome Biol. 8, R19.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S., Wong, C. K., and Lam, C. W. (2011). Activation of eosinophils by IL-12 family cytokine IL-27: Implications of the pleiotropic roles of IL-27 in allergic responses. Immunobiology216(1-2), 54–65. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Khokha, R., Murthy, A., and Weiss, A. (2013). Metalloproteinases and their natural inhibitors in inflammation and immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol 13(9), 649–665. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kim R. Y., Rae B., Neal R., Donovan C., Pinkerton J., Balachandran L., Starkey M. R., Knight D. A., Horvat J. C., Hansbro P. M. (2016). Elucidating novel disease mechanisms in severe asthma. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 5, e91.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda E., Ozasa K., Temizoz B., Ohata K., Koo C. X., Kanuma T., Kusakabe T., Kobari S., Horie M., Morimoto Y., et al. (2016). Inhaled fine particles induce alveolar macrophage death and interleukin-1alpha release to promote inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue formation. Immunity 45, 1299–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert A. L., Dong W., Selgrade M. K., Gilmour M. I. (2000). Enhanced allergic sensitization by residual oil fly ash particles is mediated by soluble metal constituents. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 165, 84–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrigan P. J., Fuller R., Acosta N. J. R., Adeyi O., Arnold R., Basu N. N., Balde A. B., Bertollini R., Bose-O'Reilly S., Boufford J. I., et al. (2017). The Lancet Commission on pollution and health. Lancet (London, England) 391(10119), 462–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. J., Wang W., Baines K. J., Bowden N. A., Hansbro P. M., Gibson P. G., Kumar R. K., Foster P. S., Yang M. (2010). IL-27/IFN-gamma induce MyD88-dependent steroid-resistant airway hyperresponsiveness by inhibiting glucocorticoid signaling in macrophages. J. Immunol. 185, 4401–4409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang S. C., Long A. J., Bennett F., Whitters M. J., Karim R., Collins M., Goldman S. J., Dunussi-Joannopoulos K., Williams C. M., Wright J. F., et al. (2007). An IL-17F/A heterodimer protein is produced by mouse Th17 cells and induces airway neutrophil recruitment. J. Immunol. 179, 7791–7799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Rohowsky-Kochan C. (2011). Interleukin-27-mediated suppression of human Th17 cells is associated with activation of STAT1 and suppressor of cytokine signaling protein 1. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 31, 459–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L., Ge, D., Ma, L., Mei, J., Liu, S., Zhang, Q., Ren, F., Liao, H., Pu, Q., Wang, T., et al (2012). Interleukin-17 and prostaglandin E2 are involved in formation of an M2 macrophage-dominant microenvironment in lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol 7(7), 1091–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Liu Q., Baumgartner J., Zhang Y., Liu Y., Sun Y., Zhang M. (2014). Oxidative potential and inflammatory impacts of source apportioned ambient air pollution in Beijing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 12920–12929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manni M. L., Trudeau J. B., Scheller E. V., Mandalapu S., Elloso M. M., Kolls J. K., Wenzel S. E., Alcorn J. F. (2014). The complex relationship between inflammation and lung function in severe asthma. Mucosal Immunol. 7, 1186–1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massoud A. H., Charbonnier L. M., Lopez D., Pellegrini M., Phipatanakul W., Chatila T. A. (2016). An asthma-associated IL4R variant exacerbates airway inflammation by promoting conversion of regulatory T cells to TH17-like cells. Nat. Med. 22, 1013–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGovern T. K., Robichaud A., Fereydoonzad L., Schuessler T. F., Martin J. G. (2013). Evaluation of respiratory system mechanics in mice using the forced oscillation technique. J. Vis. Exp. (75), e50172. May 15, doi: 10.3791/50172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal M., Siddiqui M. R., Tran K., Reddy S. P., Malik A. B. (2014). Reactive oxygen species in inflammation and tissue injury. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 20, 1126–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore W. C., Hastie A. T., Li X., Li H., Busse W. W., Jarjour N. N., Wenzel S. E., Peters S. P., Meyers D. A., Bleecker E. R. (2014). Sputum neutrophil counts are associated with more severe asthma phenotypes using cluster analysis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 133, 1557–1563.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeem A., Masood A., Siddiqui N. (2008). Oxidant–antioxidant imbalance in asthma: Scientific evidence, epidemiological data and possible therapeutic options. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2, 215–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurieva R., Yang X. O., Martinez G., Zhang Y., Panopoulos A. D., Ma L., Schluns K., Tian Q., Watowich S. S., Jetten A. M., et al. (2007). Essential autocrine regulation by IL-21 in the generation of inflammatory T cells. Nature 448, 480–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang W., Kolls J. K., Zheng Y. (2008). The biological functions of T helper 17 cell effector cytokines in inflammation. Immunity 28, 454–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrish-Novak J., Dillon S. R., Nelson A., Hammond A., Sprecher C., Gross J. A., Johnston J., Madden K., Xu W., West J., et al. (2000). Interleukin 21 and its receptor are involved in NK cell expansion and regulation of lymphocyte function. Nature 408, 57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsonage G., Filer A., Bik M., Hardie D., Lax S., Howlett K., Church L. D., Raza K., Wong S. H., Trebilcock E., et al. (2008). Prolonged, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-dependent, neutrophil survival following rheumatoid synovial fibroblast activation by IL-17 and TNFalpha. Arthritis Res. Ther. 10, R47.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelaia G., Canonica G. W., Matucci A., Paolini R., Triggiani M., Paggiaro P. (2017). Targeted therapy in severe asthma today: Focus on immunoglobulin E. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 11, 1979–1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pot C., Jin H., Awasthi A., Liu S. M., Lai C. Y., Madan R., Sharpe A. H., Karp C. L., Miaw S. C., Ho I. C., et al. (2009). Cutting edge: IL-27 induces the transcription factor c-Maf, cytokine IL-21, and the costimulatory receptor ICOS that coordinately act together to promote differentiation of IL-10-producing Tr1 cells. J. Immunol. 183, 797–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu J., Li Y., Zhong W., Gao P., Hu C. (2017). Recent developments in the role of reactive oxygen species in allergic asthma. J. Thorac. Dis. 9, E32–E43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozen S., Skaletsky H. (2000). Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol. Biol. 132, 365–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan-Ibarra S., Milet M., Lutzker L., Rodriguez D., Induni M., Kreutzer R. (2016). Age, period, and cohort effects in adult lifetime asthma prevalence in California: An application of hierarchical age-period-cohort analysis. Ann. Epidemiol. 26, 87–92. e1-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahiner U. M., Birben E., Erzurum S., Sackesen C., Kalayci O. (2011). Oxidative stress in asthma. World Allergy Organ. J. 4, 151–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders V., Breysse P., Clark J., Sproles A., Davila M., Wills-Karp M. (2010). Particulate matter-induced airway hyperresponsiveness is lymphocyte dependent. Environ. Health Perspect. 118, 640–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinyashiki M., Eiguren-Fernandez A., Schmitz D. A., Di Stefano E., Li N., Linak W. P., Cho S. H., Froines J. R., Cho A. K. (2009). Electrophilic and redox properties of diesel exhaust particles. Environ. Res. 109, 239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibilano R., Gaudenzio N., DeGorter M. K., Reber L. L., Hernandez J. D., Starkl P. M., Zurek O. W., Tsai M., Zahner S., Montgomery S. B., et al. (2016). A TNFRSF14-FcvarepsilonRI-mast cell pathway contributes to development of multiple features of asthma pathology in mice. Nat. Commun. 7, 13696.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Zhang Q., Zheng M., Ding X., Edgerton E. S., Wang X. (2011). Characterization and source apportionment of water-soluble organic matter in atmospheric fine particles (PM2.5) with high-resolution aerosol mass spectrometry and GC–MS. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 4854–4861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X., Wei H., Young D. E., Bein K. J., Smiley-Jewell S. M., Zhang Q., Fulgar C. C. B., Castañeda A. R., Pham A. K., Li W., et al. (2017). Differential pulmonary effects of wintertime California and China particulate matter in healthy young mice. Toxicol. Lett. 278, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuo Q. R., Ma Y. F., Chen W., Luo X. J., Shen J., Guo D., Zheng Y. M., Wang Y. X., Ji G., Liu Q. H. (2013). Reactive oxygen species induce a Ca(2+)-spark increase in sensitized murine airway smooth muscle cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 434, 498–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Nieuwenhuijze A. E., van de Loo F. A., Walgreen B., Bennink M., Helsen M., van den Bersselaar L., Wicks I. P., van den Berg W. B., Koenders M. I. (2015). Complementary action of granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-17A induces interleukin-23, receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand, and matrix metalloproteinases and drives bone and cartilage pathology in experimental arthritis: Rationale for combination therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 17, 163.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhoen M. (2017). Interleukin 17 is a chief orchestrator of immunity. Nat. Immunol. 18, 612–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma V., Fang T., Xu L., Peltier R. E., Russell A. G., Ng N. L., Weber R. J. (2015). Organic aerosols associated with the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by water-soluble PM2.5. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 4646–4656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Xiao W., Ma D., Zhang Y., Wang Q., Wang C., Ji X., He B., Wu X., Chen H., et al. (2013). Cross-sectional epidemiological survey of asthma in Jinan, China. Respirology 18, 313–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Zhou X., Ma Y., Cao Z., Wu R., Wang W. (2016). Carbonaceous aerosols over China–review of observations, emissions, and climate forcing. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 23, 1671–1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Hui Y., Zhao L., Hao Y., Guo H., Ren F. (2017). Oral administration of Lactobacillus paracasei L9 attenuates PM2.5-induced enhancement of airway hyperresponsiveness and allergic airway response in murine model of asthma. PLoS One 12, e0171721.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2016). Ambient air pollution: A global assessment of exposure and burden of disease. Available at: http://www.who.int/phe/publications/air-pollution-global-assessment/en/. Last Accessed May 26, 2018.

- WHO. (2017). Asthma Fact Sheet. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs307/en/. Last Accessed May 26, 2018.

- Xia, W., Bai, J., Wu, X., Wei, Y., Feng, S., Li, L., Zhang, J., Xiong, G., Fan, Y., Shi, J., et al. (2014). Interleukin-17A promotes MUC5AC expression and goblet cell hyperplasia in nasal polyps via the Act1-mediated pathway. PLoS One9(6), e98915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhang J., Dai J., Yan L., Fu W., Yi J., Chen Y., Liu C., Xu D., Wang Q. (2016). Air pollutants, climate, and the prevalence of pediatric asthma in urban areas of China. BioMed. Res. Int. 2016, 2935163.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Liu Y., Cui L., Liu S., Yin X., Li H. (2017). Ambient air pollution, smog episodes and mortality in Jinan, China. Sci. Rep. 7, 11209.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.