Abstract

2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD), the classic aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) agonist, is a potent environmental toxicant and endocrine-disrupting chemical (EDC) with known developmental toxicity in humans, rodents, and fish. Early life exposure to some EDCs, including TCDD, is linked to the occurrence of adult-onset and multigenerational disease. Previous work exposing juvenile F0 zebrafish (Danio rerio) to 50 ppt (parts per trillion) TCDD during reproductive development has shown male-mediated transgenerational decreases in fertility (F0–F2) and histologic and transcriptomic alterations in F0 testes. Here, we analyzed male germline alterations in F1 and F2 adult fish, looking for changes in testicular histology and gene expression inherited through the male lineage that could account for decreased reproductive capacity. Testes of TCDD-lineage F1 fish displayed an increase in spermatogonia (immature germ cells) and decrease in spermatozoa (mature germ cells). No histological changes were present in F2 fish. Transcriptomic analysis of exposed F1 and F2 testes revealed alterations in lipid and glucose metabolism, oxidation, xenobiotic response, and sperm cell development and maintenance genes, all of which are implicated in fertility outcomes. Overall, we found that differential expression of reproductive genes and reduced capacity of sperm cells to mature could account for the reproductive defects previously seen in TCDD-exposed male zebrafish and their descendants, providing insight into the distinct multigenerational effects of toxicant exposure.

Keywords: toxicity, transgenerational, dioxin, zebrafish, testicular tissue, microarray

The long-term outcomes of exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), natural or synthetic compounds that interfere with hormonal signaling pathways, are a heavy burden on society in terms of health outcomes and financial impact. The World Health Organization (WHO) and Endocrine Society have released statements of concern regarding the increasing role of exposure to environmental EDCs in disease outcomes, including rises in male infertility, genital malformations, and adverse pregnancy outcomes (Bergman et al., 2013; Gore et al., 2015), and recent estimates put the cost of EDC-linked disease at $340 billion (2.33% GDP) in the United States, and the equivalent of $217 billion (1.28% GDP) in the European Union (Attina et al., 2016). Although EDCs are usually detected at very low levels in the environment, these quantities are enough to potentially alter the highly sensitive endocrine system (Welshons et al., 2003). Many of these chemicals are bioaccumulative and have long half-lives in the human body (ASTDR, 1998; Steele et al., 1986) with potential for additive or synergistic effects with the milieu of other chemicals in the environment (Kortenkamp, 2014). Exposure to many of these compounds, particularly those that are lipophilic, during pregnancy or infancy may disrupt critical windows of development (Brouwer et al., 1999; Eckstrum et al., 2018; Zoeller et al., 2012), leading to life-long and multigenerational disease outcomes (Baker et al., 2014a,b; Brehm et al., 2018; Bruner-Tran and Osteen, 2011). Altering the endocrine system during these crucial timeframes can result in altered reprogramming of the epigenome (Manikkam et al., 2012; Skinner et al., 2013). As the methylome is heritable through the male germline in zebrafish (Jiang et al., 2013b), this has implications for inheritance of disease-causing epimutations across generations.

TCDD, or 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin, is an EDC and environmental contaminant known as the most potent ligand for the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) (Denison and Nagy, 2003). Highly bioaccumulative and lipophilic (ATSDR, 1998), TCDD is persistent in the environment and affects a vast variety of physiological systems and model organisms (Bruner-Tran and Osteen, 2011; Hermsen et al., 2008; Hornung et al., 1999). Although environmental levels of TCDD have declined over recent decades (Aylward and Hays, 2002), its persistence in humans (ASDTR, 1998), as well as its ability to model effects of other environmental AhR ligands (Okey, 2007), make it a useful and informative chemical to study. Of particular interest are the reproductive effects of early TCDD exposure, which extend for multiple generations (Baker et al., 2014a,b; Bruner-Tran and Osteen, 2011; Sanabria et al., 2016).

In zebrafish (Danio rerio), an NIH-validated model organism with relatively rapid turnover time, high fecundity, and endocrine signaling similar to that of humans (Peterson and Macrae, 2012; Teraoka et al., 2003), exposure to low-level dioxin (50 pg/ml) during gonadal differentiation and maturation (at 3 and 7 weeks postfertilization [wpf]) in the F0 generation resulted in transgenerational decreases in number of eggs elicited and fertilized (Baker et al., 2013, 2014b). Outcrosses with control fish for each generation (F0–F2) revealed that these effects were attributable to the male lineage. In fact, testicular histopathology and transcriptomics for the F0 generation indicated delayed spermiation and alteration in several genes involved in fertility, spermatogenesis, or lipid metabolism, pathways implicated in this male-mediated reduction in fertility (Baker et al., 2016).

In this study, we perform analysis on testes from subsequent generations to interrogate the persistence of delayed spermiation in the F1 TCDD-lineage generation and transcriptomic alterations in both F1 and F2 TCDD-lineage generations. Thus, we can characterize the cross-generational impact of early life F0 generation EDC exposure, as well as the physiological and genetic alterations potentially underlying these reproductive outcomes. The initial study was the first instance of transgenerational inheritance of disease using zebrafish as a model organism, and our further investigation of these findings will enhance the use of this organism in modelling human disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fish husbandry

AB lineage zebrafish were maintained on a 14:10 h light/dark cycle (Westerfield, 2000) in reverse osmosis water buffered with Instant Ocean salts (60 mg/l, Aquarium Systems, Mentor, Ohio), with temperatures maintained at 27°C–30°C. Fish were fed 2 times daily and euthanized with an overdose of tricaine methanesulfonate (MS-222; 1.67 mg/ml). Adult fish were raised on a recirculating system at a maximum density of 5 fish per liter. F0 fish were raised in beakers with daily water changes of 40%–60% at a density of 5 fish per 400 ml beaker between 3 and 6 weeks, and 5 fish per 800 ml beaker between 6 and 9 weeks postfertilization (wpf). Animal use protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at Wayne State University and the University of Wisconsin-Madison, according to the National Institutes of Health Guide to the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Protocol No. M00489).

TCDD exposure and spawning

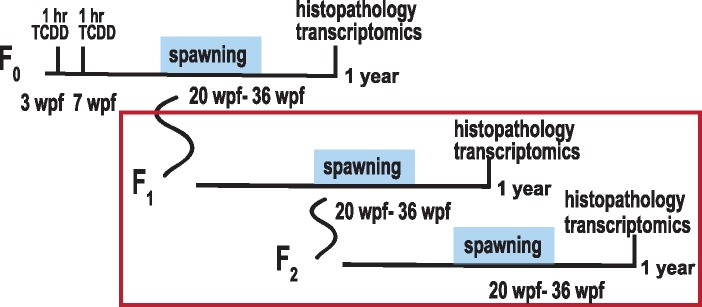

2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (>99% purity, Chemsyn) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as vehicle. Exposures occurred according to Baker et al. (2013). In brief, F0 fish were exposed to 50 pg/ml waterborne TCDD or 0.1% DMSO control in small beakers for 1 h at both 3 and 7 weeks post fertilization (wpf), during sexual differentiation and maturation. As indicated in Baker et al. (2016), 3 replicate blocks were exposed. Each block consisted of 8 vials, which each held 5 fish. Fish were raised to 6 months and group-spawned to create the F1 generation, which was indirectly exposed as germ cells within juvenile F0 fish (2 cohorts/block). F1 fish were subsequently spawned at six months to create the unexposed F2 generation (2 cohorts/block). At 1 year of age, F1 and F2 male fish were euthanized and collected for histologic and transcriptomic analysis. 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin exposure and spawning schema are diagrammed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

TCDD exposure paradigm. F0 zebrafish were exposed to 50 pg/ml TCDD for 1 h at 3 and 7 wpf (weeks post fertilization). Fish were spawned for fertility assessment at 20–36 wpf, and offspring from spawns were raised to create the next generation. Fish were assessed for testicular histology and transcriptomics at 1 year. F1 and F2 fish were not directly exposed to TCDD but were spawned and analyzed as described above. TCDD, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin.

Histology

Sample processing was performed according to Baker et al. (2016). For F1 and F2 generations, 6 male fish at 1 year of age from both TCDD and DMSO lineages were euthanized, fixed in 10% Zn-formalin, decalcified with Cal-ExII, and sagittally bisected. Fish were dehydrated in ethanol, cleared in xylene, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned at 5 μm thickness. Sections were mounted and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained. Testicular tissue was imaged using a Nikon SMZ18 stereomicroscope at 21.6× magnification with a Nikon DS-Qi2 camera. From at least 3 images, 9 seminiferous tubules with well-defined boundaries were selected per fish for quantification purposes. Germ cells within these seminiferous tubules were visually sorted into the four main stages of spermatogenic differentiation as follows: Spermatogonia (least mature), spermatocytes, spermatids, and spermatozoa (most mature). Supplementary Figure 1 demonstrates the categorization of these cell types within seminiferous tubules. ImageJ version 1.5 (http://imagej.nih.gov; last accessed January 6, 2016) was used to assess each tubule for the area occupied per cell type and for germinal epithelium width.

RNA isolation

Five male fish each from TCDD and DMSO lineages from F1 to F2 generations were euthanized, and testes were extracted, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Testes were homogenized in QIAzol lysis reagent (Qiagen), and RNA was isolated with the Qiagen RNEasy mini kit. RNA was quantified and purity was assessed with Nanodrop-1000 (ThermoFisher Scientific). The Agilent RNA 6000 Nano kit was used to assess RNA quality using an Agilent Bioanalyzer, as performed in Baker et al. (2016). RNA integrity number (RIN) values were between 7.1 and 8.2 for F1 and between 7.2 and 8.7 for the F2 (Supplementary Table 1).

Microarray

Whole genome transcriptomic changes in the testes of TCDD-lineage F1 and F2 male fish were examined through the use of Zebrafish Gene 1.0 ST Genome Arrays (Affymetrix). Procedure was carried out as previously described in Baker et al. (2016) for F0 fish. Briefly, RNA was isolated as described above from five TCDD-lineage and five control-lineage fish per generation (F1 and F2) and processed with the Ambion WT Expression Kit. Processing, labeling, and hybridization was carried out according to MIAME guidelines by the University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Gene Expression Center. Samples were end-terminus labeled according to the protocol from the Affymetrix GeneChip WT terminal labeling and hybridization user manual target (P/N 702808 Rev. 7), then fragmented and hybridized to independent Zebrafish Gene 1.0 ST Genome Arrays per each sample. Hybridization and analysis occurred according to Baker et al. (2016). In short, 10 μg cRNA was hybridized at 45°C for 16 h, and GeneChips were, respectively, washed and stained in the Affymetrix Fluidics Station 450 and scanned using the Affymetrix GeneArray Scanner GC3000 G7.

The Transcriptome Analysis Console (TAC, Affymetrix) was used to normalize gene expression data by calculating individual gene intensity per sample using the Tukey’s Biweight average (log 2 scale) for all eligible exon (probe selection regions [PSRs]) intensities in that gene. Then each PSR was normalized using the calculated gene intensity for that sample. Affymetrix Expression Console Software was used to assess data for outliers; none were found or removed from analysis. Condition 1 (TCDD-lineage) and Condition 2 (DMSO-lineage) normalized intensities were combined across PSRs and junctions within a gene. Genes of interest were defined as those with a p-value <.05 and an absolute fold change >1.5. Data were uploaded to NCBI GEO database (GSE111446). Pathway analysis was performed on genes of interest (as defined above) using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA). All F0 transcriptomic data included in this study for multigenerational comparison was reported in a previous study (Baker et al., 2016), and uploaded to NCBI GEO database (GSE77335).

qRT-PCR

qRT-PCR was run on a sampling of genes in order to validate microarray results. RNA from testes was isolated as described above and used to validate nine genes of interest using TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Life Technologies). Initially, RNA concentration was re-verified using RNA High Sensitivity assays on the Qubit Fluorometer (ThermoFisher Scientific). The High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit with MultiScribe Reverse Transcriptase was used to reverse-transcribe 10 μl of 50 ng/μl RNA into 20 μl of 25 ng/μl cDNA. The TaqMan Preamp Mastermix Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) was then used to preamplify 250 ng of cDNA for genes of interest. The preamplification reaction was 14 cycles long at a reaction volume of 50 μl. Probes used were either predesigned Taqman Gene Expression Assay probes [actb1 (Dr03432610_m1), aste1 (Dr03425048_m1), mhc1uba (Dr03144312_m1), si: dkeyp-72h1.1 (Dr03092415_m1), smyd1a (Dr03438580_m1), spata4 (Dr03421991_m1), and zgc: 158731 (Dr03149463_m1)], probes custom-designed to input sequences using the ThermoFisher Scientific Custom TaqMan Assay Design bioinformatics tool (mcf2la [Genomic Position: 1: 46675304–46697602; Assay ID: ARZTDZ7]), or probes custom-designed to input sequences by ThermoFisher Scientific bioinformatics design technicians (socs1a [NCBI RefSeq ID: NM_001003467; Custom ID: APYMJJM]).

qRT-PCR was analyzed using a QuantStudio 5. qRT-PCR reactions were plated using a Gilson 268 PIPETMAX liquid handling platform and were run in triplicate on 384-well plates. Reactions were performed using TaqMan Universal Master Mix (ThermoFisher Scientific), and reaction volumes were 20 μl, 2 μl of which consisted of preamplified cDNA. Manufacturers’ protocol was followed to determine thermal cycling parameters. Probes and qRT-PCR protocols are MIQE-compliant. Probes were selected or designed to provide best coverage according to the ThermoFisher database. 2−ΔΔCt (cycle threshold) methods were used to analyze qRT-PCR data by normalizing all transcripts to the reference gene actb1 (β-actin), which did not show alteration due to TCDD on either the microarray or qPCR.

Statistical analysis

Histologic quantification and qPCR gene expression data were analyzed using Student’s t-test in Microsoft Excel, and microarray data were analyzed with one-way between subject ANOVA comparing each generation independently (ie F1-TCDD vs F1-DMSO and F2-TCDD vs F2-DMSO) using the TAC. For all analyses, significant difference between treated and control was determined by p-value <.05.

RESULTS

Histology

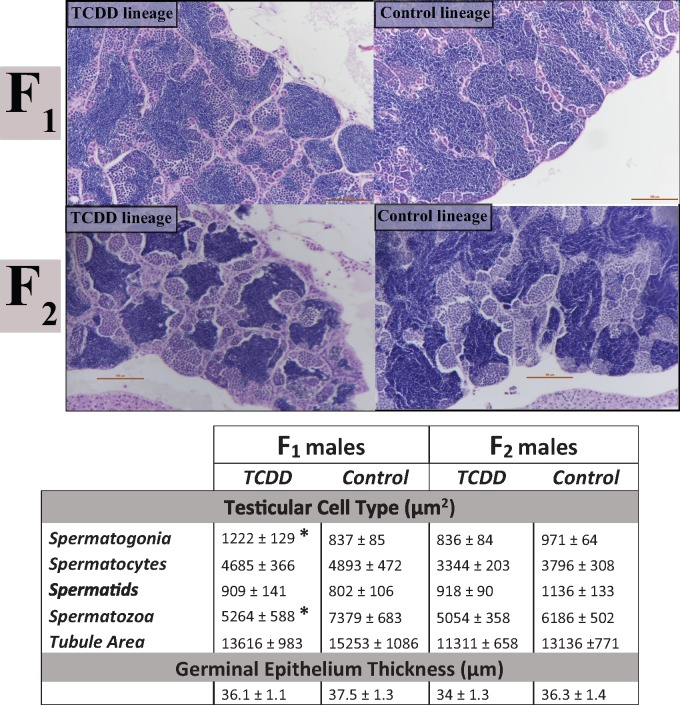

Based on our results in the F0 generation, we assessed ratios of germ/sperm cells within the testes in F1 and F2 testicular tissue. Quantification of germ/sperm cells revealed spermatogenic dysregulation in F1 TCDD-lineage fish. Seminiferous tubule size was not significantly different between the F1 TCDD and F1 DMSO (control) lineages. Within the seminiferous tubules, F1 TCDD-lineage fish demonstrated an increase in area occupied by spermatogonia (undifferentiated germ cells; p = .014) and a simultaneous decrease in area occupied by spermatozoa (mature sperm cells; p = .021) when compared with control fish (Figure 2). No differences were found in area between control and exposed fish for spermatocytes (p = .73) or spermatids (p = .55), both intermediate cell types, and no differences were noted in germinal epithelium width (p = .41) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Quantification of germ cell types within the testes (ImageJ). H&E images of testicular tissue at ×21.6 magnification indicate that TCDD-lineage F1 fish show a decreased area occupied by spermatozoa and an increased area of spermatogonia within seminiferous tubules. F2 fish did not demonstrate differences in germ cell area due to ancestral TCDD exposure compared with controls. Top row consists of F1 TCDD and control (DMSO) lineage testes. Second row consists of F2 TCDD and control (DMSO) lineage testes. Scale bars in images are 100 µm length. Values in the table below indicate the mean area (µm2) ± SEM of each cell type within seminiferous tubules or the mean width of the germinal epithelium (µm) ± SEM for TCDD or control lineages. *Significant difference from control, as defined by p < .05. H&E, Hematoxylin and eosin; TCDD, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; SEM, Standard Error of the Mean.

In the F2 generation, which demonstrated decreased reproductive capacity (Baker et al., 2014b), there was a trend toward a decrease in spermatozoa in TCDD-lineage F2 fish. No significant differences were observed in seminiferous tubule size, germinal epithelium width (p = .23), or any of the four germ/sperm cell types [spermatogonia (p = .20), spermatocytes (p = .22), spermatids (p = .17), and spermatozoa (p = .07)] (Figure 2).

Microarray

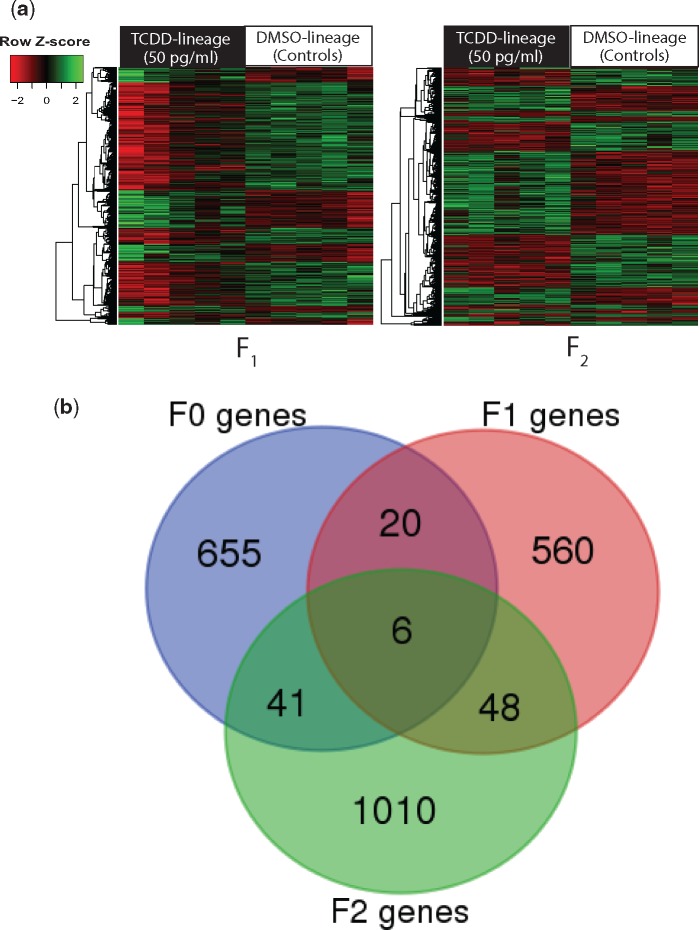

Whole-genome microarray analysis on F1 and F2 adults showed that 634 genes were differentially expressed in F1 TCDD-lineage fish when compared with DMSO-lineage fish; 560 of those genes were uniquely altered in the F1 generation (Figure 3). When compared with controls, 68% of these genes were significantly downregulated and 32% were upregulated. In the F2 generation of TCDD-lineage fish, 1105 genes were differentially expressed, with 1010 of those genes unique to the F2 generation. Of those genes, 46% were downregulated, and 54% were upregulated. Table 1 indicates several differentially expressed genes of interest from F0 to F2 generations, and the 100 most differentially regulated annotated genes in either direction are included in Supplementary Table 2. The most highly upregulated gene from the F1 generation was acyl-Coenzyme A oxidase 1, palmitoyl (acox1), a peroxisomal β-oxidation enzyme involved in lipid metabolism (Rakhshandehroo et al., 2010), with a fold change of 10.65 and a p-value of .0071. Spermatogenesis associated 4 (spata4), a gene enriched in the testes and suspected to play a role in regulating germ cell apoptosis (Jiang et al., 2015), was also highly downregulated (−19.12). Though the microarray p-value was just above the cutoff for significance (p = .050589), qRT-PCR analysis successfully validated the gene as significantly downregulated. Other dysregulated genes with roles in infertility included gcga (7.96, p = .034) and gcgb (2.08, p = .030), or glucagon a and b, ins, or preproinsulin (3.86, p = .038), and sgk1, or serum/glucocorticoid regulated kinase 1 (2.22, p = .039). In the F2 generation, one of the most differentially regulated genes was ftr50, or finTRIM (tripartite motif) family, member 50 (−131.88, p = .038), a member of a gene family implicated in antiviral immunity (Luo et al., 2017). Similar to the F1 generation, several genes involved in spermatogenesis and fertility were also upregulated, including spata4 (8.22, p = .000078), acox1 (6.12, p = .000522), nudt15, or nudix (nucleoside diphosphate linked moiety X)-type motif 15 (3.68, p = .002318), a gene involved in xenobiotic response and mediating oxidative toxicity (Cai et al., 2003) and hsp70, or heat shock protein 70 (1.98, p = .002).

Figure 3.

Differentially expressed transcripts in TCDD-lineage F1–F2 generations (microarray) and multigenerational (F0–F2) transcriptomic overlap. A, Microarray results for F1 and F2 generations. Heatmapper (http://www1.heatmapper.ca; last accessed February 18, 2018) (Babicki et al., 2016). was used to hierarchically cluster differentially expressed (p-value <.05, FC >1.5) transcripts by similar expression level (row clustering) using Euclidean distance. Individual fish are grouped by treatment (TCDD-lineage vs DMSO-lineage) and each column indicates an individual. The scale indicates normalized (z-score) transcript expression levels. B, Venn diagram indicating overlap among differentially expressed transcripts in TCDD-lineage F0–F2 generations. Differentially expressed transcripts (FC >1.5; p-value <.05) in the TCDD lineage for each generation were uploaded into the Bioinformatics and Evolutionary Genomics custom Venn diagram generator (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/; last accessed January 7, 2018) and assessed for overlap across generations. Minimal transgenerational overlap is present. TCDD, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin; FC, fold change; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide.

Table 1.

Microarray Values for Differentially Expressed Genes Involved in Fertility or Spermatogenesis in TCDD-lineage F0–F2 Testes

| Symbol | Name | F0 |

F1 |

F2 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FC | p-value | FC | p-value | FC | p-value | ||

| acox1 | Acyl-coenzyme A oxidase 1 | −1.32 | >0.1 | 10.65 | 0.0071 | 6.12 | 0.000522 |

| gcga | Glucagon a | 1.3 | >0.1 | 7.96 | 0.034 | 3.14 | >0.1 |

| ins | Preproinsulin | 1.17 | >0.1 | 3.86 | 0.038 | 3.06 | 0.099364 |

| sgk1 | Serum/glucocorticoid regulated kinase 1 | 1.32 | 0.03904 | 2.22 | 0.039 | −1.17 | >0.1 |

| gcgb | Glucagon b | −1.09 | >0.1 | 2.08 | 0.03 | 2.52 | >0.1 |

| spata4 | Spermatogenesis associated 4 | −1.77 | 0.073348 | −19.12 | 0.050589 | 8.22 | 0.000078 |

| nudt15 | Nudix (nucleoside diphosphate linked moiety X)-type motif 15 | −3.03 | 0.0086 | −2.48 | 0.094414 | 3.68 | 0.002318 |

| hsp70 | Heat shock protein 70 | −1.49 | 0.022 | −1.21 | >0.1 | 1.98 | 0.002 |

| ftr50 | finTRIM( tripartite motif) family, member 50 | 1.14 | >0.1 | −18.24 | >0.1 | −131.88 | 0.038 |

Fold changes and p-values for microarray data are listed per gene; p-value is determined using ANOVA. Bolded text indicates significant difference from control (FC >1.5, p-value <0.05).

TCDD, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin; FC, fold change; ANOVA, analysis of variance.

To verify that effects on gene expression were not due to any direct exposure to TCDD, cyp1a transcripts were assessed; no cyp1a induction was found in F1 or F2 TCDD-lineage testicular tissue (Supplementary Table 3). In a similar vein, a variety of hormone synthesis, hormone response, and classical AhR battery response transcripts were not altered by TCDD exposure in the F1 or F2 generations (Supplementary Table 3).

Ingenuity pathway analysis was performed on differentially regulated genes, as defined above (FC >1.5, p-value <.05) using GenBank IDs; in the F1 generation, 139 molecules were accessible for analysis with IPA, and 164 molecules were available in the F2 generation. A table of the most enriched disease and biologic functions is included as Supplementary Table 4 with specific pathways involved in reproductive function listed in Table 2. As indicated in Supplementary Table, endocrine system disorders and metabolic disease were 2 of the top 5 enriched diseases and disorders for the F1 generation. Several of the specific enriched pathways in the F1 generation (Table 2) included reproductive system disease, metabolic disease, and lipid metabolism, which are all functions implicated in fertility and spermatogenesis. For pathways that were enriched in the IPA analysis of the F2 generation, inflammatory and immunological disease were among the most upregulated pathways, which corresponds with the large number of immune (finTRIM family, major histocompatibility complex class I UBA, granulin family) genes differentially regulated in the F2 generation (Supplementary Table 2). The affected pathways related to fertility and spermatogenesis in the F2 generation included cell-to-cell signaling and interaction, cellular movement, reproductive system disease, cellular compromise, lipid metabolism, and metabolic disease.

Table 2.

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis-Generated List of Select Pathways Implicated in Reproduction and Fertility in TCDD-Lineage F1 and F2 Zebrafish Testes

| p-value | # of genes | |

|---|---|---|

| F1 IPA Genes | ||

| Vitamin and mineral metabolism | ||

| Synthesis of glucocorticoid | 9.85E−03 | 2 |

| Synthesis of steroid hormone | 1.17E−02 | 3 |

| Metabolism of aldosterone | 6.27E−03 | 1 |

| Reproductive system disease | ||

| Disorder of pregnancy | 4.61E−03 | 12 |

| Abortion | 6.37E−03 | 3 |

| Impotence | 1.07E−02 | 2 |

| Female infertility | 1.15E−02 | 2 |

| Panhypopituitarism-X-linked | 5.77E−04 | 2 |

| Metabolic disease | ||

| Glucose metabolism disorder | 1.60E−04 | 26 |

| Disorder of lipid metabolism | 9.75E−03 | 6 |

| Hypoinsulinemia | 7.59E−03 | 2 |

| Lipid metabolism | ||

| Quantity of steroid hormone | 9.00E−05 | 7 |

| Quantity of steroid | 2.26E−03 | 11 |

| Synthesis of lipid | 3.60E−03 | 14 |

| Synthesis of fatty acid | 3.85E−03 | 8 |

| Synthesis of long chain fatty acid | 5.02E−04 | 3 |

| Conversion of phospholipid | 6.23E−03 | 2 |

| Reduction of palmitoyl-coenzyme A | 6.27E−03 | 1 |

| Concentration of corticosterone | 1.16E−03 | 5 |

| F2 IPA Genes | ||

| Cell-to-cell signaling and interaction | ||

| Adhesion of spermatids | 1.60E−02 | 1 |

| Cellular movement | ||

| Movement of spermatids | 2.40E−02 | 1 |

| Reproductive system disease | ||

| Antley-Bixler syndrome with genital anomalies | 8.05E−03 | 1 |

| and disordered steroidogenesis | ||

| Abortion | 1.26E−02 | 3 |

| Cytotoxicity of gonadal cell lines | 2.40E−02 | 1 |

| Cell viability of gonadal cell lines | 1.46E−02 | 2 |

| Metabolic disease | ||

| Combined oxidative phosphorylation deficiency 5 | 8.05E−03 | 1 |

| Disorder of lipid metabolism | 8.95E−03 | 7 |

| High density lipoprotein deficiency type 2 | 1.60E−02 | 1 |

| Cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase deficiency | 8.05E−03 | 1 |

| Lipid metabolism | ||

| Attachment of cholesterol | 8.05E−03 | 1 |

| Oxidation of long chain fatty acid | 1.90E−02 | 3 |

| Loss of sterol | 1.60E−02 | 1 |

| Abnormal quantity of phospholipid | 1.58E−02 | |

| Cellular compromise | ||

| Depletion of lipid droplets | 8.05E−03 | 1 |

Number of differentially expressed genes involved in each pathway is noted. Bolded rows indicate comparatively enriched pathways (≥3 genes). TCDD, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin.

We compared differentially expressed transcripts from F0 to F2 generations and found minimal overlap (Figure 3); only 6 transcripts are consistently altered in the TCDD exposure lineage across all three generations (Table 3). Three of the 6 transcripts are predicted to code for the novel immune-type receptor 3, related 1-like (nitr3r.1l), and 1 is predicted to code for the gastrula zinc finger protein (XlCGF52.1). No homologous sequences/genes for the remaining two transcripts were identified despite a search using Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST; http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi; last accessed January 13, 2018). Five out of the 6 transcripts were downregulated in both the F0 and F1 but upregulated in the F2 generation, whereas the 6th was downregulated in all three generations. In both the F0 and F1 generations, 20 differentially expressed transcripts were selectively altered. In the F1 and F2 generations, 48 transcripts were altered including acox1, which is upregulated in both generations, and 41 transcripts were altered in both the F0 and F2 generations, including nudt15, which is downregulated in the F0 but upregulated in the F2 generation.

Table 3.

Microarray Transcripts Differentially Expressed in TCDD-Lineage Fish Across All 3 Generations (F0–F2)

| F0–F2 Microarray Overlap | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Computer-Predicted |

F0 |

F1 |

F2 |

|||||||

|

Transcript No. |

Gene ID |

Symbol |

Name |

FC |

p-Value |

FC |

p-Value |

FC |

p-Value |

|

| 13280478 | XM_005166663 | nitr3r.1l | novel immune-type receptor 3, related 1-like | −1.59 | 0.030 | −2.09 | 0.039 | 1.52 | 0.015 | |

| 13284886 | XM_005166663 | nitr3r.1l | novel immune-type receptor 3, related 1-like | −1.59 | 0.030 | −2.09 | 0.039 | 1.52 | 0.015 | |

| 13280442 | XM_005166663 | nitr3r.1l | novel immune-type receptor 3, related 1-like | −1.59 | 0.030 | −2.09 | 0.039 | 1.52 | 0.015 | |

| 13273229 | XM_003201642 | XlCGF52.1 | gastrula zinc finger protein | −1.71 | 0.005 | −1.52 | 0.046 | 1.98 | 0.012 | |

|

Unidentified |

F0 |

F1 |

F2 |

|||||||

|

Transcript No. |

Gene ID |

Genomic Location |

FC |

p-Value |

FC |

p-Value |

FC |

p-Value |

||

| 13201649 | – | chr5: 7194748–7196383 | −1.72 | 0.035 | −2.16 | 0.026 | 2.69 | < .001 | ||

| 13022462 | – | chr15: 43367712–43368245 | −3.58 | 0.009 | −2.99 | 0.002 | −4.21 | 0.002 | ||

TCDD, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin; BLAST, Basic Local Alignment Search Tool; FC, fold change.

qRT-PCR

Genes from the F1 and F2 generations were selected for qRT-PCR validation of microarray results based on microarray values (high fold change or low p-values) or relevance to spermatogenesis (Supplementary Table 5). The direction of fold change was consistent between the two methods for all genes.

DISCUSSION

Our results correspond with other studies that found dysregulation in spermatogenic cells and multigenerational infertility as a result of TCDD exposure (Baker et al., 2014b; Bruner-Tran et al., 2014; Chahoud et al., 1992; Sanabria et al., 2016). Histological analysis of F1 and F2 testes revealed an altered germ/sperm cell ratio in TCDD-lineage F1 fish, with increases in the area of immature spermatogonia and decreases in mature spermatozoa, whereas no changes were present in intermediate cell types. Additionally, though testicular germinal epithelium was reduced in width in the F0 generation (Baker et al., 2016), this did not persist into the F1 or F2 generations. Ablation/reduction of germinal epithelium is a well-established endpoint of reproductive toxicity (Baker et al., 2016; Chahoud et al., 1992; Cordeiro et al., 2018), but may be an effect of direct toxicant-induced damage to seminiferous tubule structure. Intriguingly, the shift in germ/sperm cell ratio persisted from the F0 parental generation, which were directly exposed to TCDD as juveniles (Baker et al., 2016), to the indirectly exposed F1 generation, and trended towards significance in the unexposed F2 generation.

According to the OECD Guidance Document for the Diagnosis of Endocrine-Related Histopathology of Fish Gonads (Johnson et al., 2009), such a shift in germ cell ratio is considered both a primary (increase in spermatogonia) and secondary (decrease in spermatozoa) indication of EDC-induced histopathological disruption. Also known as hypospermatogenesis, this shift is a major category of testicular dysgenesis syndrome that is impacted by environmental factors during early programming events (Bhattacharya and Majumdar, 2015; Mocarelli et al., 2007). Thus, the persistence of this shift in germ/sperm cell ratio is likely explained by inheritance of epimutations, a hypothesis that is further supported by our previous finding that transgenerational infertility following TCDD exposure in zebrafish is transmitted through the male germline (Baker et al., 2014b), as well as the sex-specific mechanism of zebrafish genome reprogramming, ie the male epigenetic lineage controls the reprogramming process, with the female lineage silenced (Jiang et al., 2013b). Additionally, accumulation of TCDD in lipophilic reservoirs (Lanham et al., 2012) and the germ line would be minimal, if any, given the short period of TCDD exposure (1 h), time between exposure and spawning (4 months), small size of the juvenile fish, and lack of cyp1a induction as assessed by microarray in F1 and F2 testicular tissues, thus limiting the possibility of direct exposure of subsequent generations.

Whole genome microarray analysis on TCDD-lineage F1 and F2 testicular tissue revealed dysregulation of glucose regulation, lipid metabolism, and germ cell development genes heavily implicated in fertility and spermatogenesis. In the F1 generation, glucagon a/b and preproinsulin, both involved in glucose regulation, were upregulated despite their conflicting role in glucose metabolism: Glucagon upregulates and insulin downregulates glucose levels (Zhao et al., 2018). Upregulation of both genes may indicate that one is primarily altered by TCDD, whereas the other is upregulated as a feedback mechanism for maintaining glucose homeostasis. Tightly regulated glucose metabolism is essential for the maintenance of spermatogenic germ cells and subsequent functionality of sperm cells (Alves et al., 2013). Therefore, any disruption can lead to reduced fertility outcomes. Additionally, the cell survival regulator sgk1 (serum glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1) was upregulated in the F1 generation. Sgk1, induced in response to hormonal stimuli, has been linked with coordination and maintenance of reproductive function in females, and was upregulated in a model of testicular torsion (Cho et al., 2011), an injury that leads to ischemia in the testes, subsequent germ cell apoptosis, and infertility (Filho et al., 2004). In the F2 generation, hsp70, a chaperone and quality control protein (Mayer and Bukau, 2005) that is also dysregulated in the F0 generation (Baker et al., 2016) and is positively correlated with infertility in human sperm samples (Erata et al., 2008), was upregulated, suggesting a compensatory mechanism to counteract germ cell apoptosis.

Despite minimal overlap in differentially expressed transcripts across generations, several genes with importance in reproductive function were differentially expressed in more than one generation. Acox1, for instance, was upregulated across both F1 and F2 generations. Normal peroxisomal function as mediated by acox1 is critical for fertility (Fan et al., 1996). The upstream regulator of acox1, PPARα (peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor alpha), engages in crosstalk with the AhR (Ernst et al., 2014; Shaban et al., 2004), and thus TCDD and dioxin-like compounds, as AhR ligands, may misregulate PPARα signaling pathways. Increases in acox1 activity also correspond with an overall increase in peroxisomal activity, and therefore can be associated with the presence of increased oxidative stress (Zeng et al., 2017), a TCDD-induced outcome (Latchoumycandane et al., 2003) that can result in infertility through damaging sperm membrane and DNA (Tremellen, 2008).

Spata4, a testis-specific gene closely associated with spermatogenic fate and regulation of Sertoli cell proliferation (Jiang et al., 2013a, 2015), was altered in both F1 and F2 generations. Spata4 was downregulated in the F1 generation, which corresponds with our histopathologic findings of hypospermatogonia; previous studies also found decreases in spata4 expression accompanied by inhibition of spermatogenesis in fish exposed to flame retardants (Li et al., 2014). Conversely, spata4 was greatly upregulated in the F2 generation. Likewise, nudt15, a xenobiotic response gene involved in mediating oxidative stress (Cai et al., 2003), was upregulated in the F2 generation, whereas in the F0, it was downregulated. The upregulation of both genes in the F2 may indicate lingering epigenetic changes that compensated for TCDD-induced pathway dysregulation in the F1 generation, ie F2 generation is adapting to a toxicant that is no longer present. Supporting this idea, a greater percentage of differentially expressed genes shift from downregulation to upregulation between the F1 and F2 (from 32% to 54% upregulated, respectively).

Several families of genes involved in immune response were also dysregulated. Specifically, multiple finTRIM family and granulin genes were downregulated in the F2 generation. Furthermore, nitr3r.1l, the gene associated with 3 of the 6 differentially expressed transcripts across all generations, is an immune receptor gene, indicating that immune response is disrupted across generations, but particularly in the F2. Disruption of immune function on a broad scale can have implications for fertility, as several inflammatory cytokines and factors involved in immune response are also involved in supporting and signaling within germ cell populations (Loveland et al., 2017). Misregulation of the immune system in reproductive tissues can lead to inflammation or infection, well-established causal factors for impaired spermatogenesis and decreased sperm count and quality (Schuppe et al., 2008).

Transcriptomic analysis in all three generations showed dysregulation in many of the same pathways, including lipid and steroid metabolism, oxidative stress, glucose metabolism, spermatogenesis, and germ cell development, although overlap in specific genes was minimal. A greater number of genes involved in germ cell development and maturation were differentially regulated in the F0 when compared with subsequent generations (Baker et al., 2016). Overall, however, a similar number of genes were differentially altered between the F0 (Baker et al., 2016) and F1 generations. The transcriptome of the F2 generation was evidently more altered due to ancestral TCDD exposure with almost twice the number of differentially expressed transcripts as the previous two generations. This comparative abundance of differentially expressed transcripts in the F2 runs counterintuitive to expected results, as effects of direct exposure to TCDD would reasonably be more severe than subsequent generations. However, certain outcomes only present transgenerationally; previously, exposure to a plastics mixture during gestation resulted in a variety of disease outcomes across generations, with some (obesity) only present in the rodent F3 generation (Manikkam et al., 2013). The mechanisms underlying these multigenerational findings deserve further interrogation, particularly concerning the type and genomic location of potential epimutations.

Transgenerational studies of endocrine disruption have raised public and academic concern on a population-wide level, but the possibility that EDC exposure may induce generationally distinct transcriptomes, due to the interplay of differential mechanisms of toxicity across generations, complicates the clinical effort to rescue such phenotypes. As a whole, this multigenerational response gives insight into the nature of EDC-induced reproductive disease, and raises many potential ideas concerning the mechanism of epigenetic heritability of this disease, the genes to which it might be linked, and the mechanisms through which direct exposure, indirect exposure, and unexposed generations have their own unique, often opposing transcriptomic footprint, despite all exhibiting similar phenotypes of infertility.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at Toxicological Sciences online.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (T32 ES007015), the National Center for Advancement of Translational Sciences (K01 OD01462 to T.R.B.), and the WSU Center for Urban Responses to Environmental Stressors (P30 ES020957) (to T.R.B.).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Gene Expression Center for providing Affymetrix GeneChip services, and the Wayne State University Applied Genomics Technology Center for use of Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software. We are grateful to our lab manager Emily Crofts, Jeremy Shields, Camille Akemann, and the other members of the Baker laboratory for the time and effort they have dedicated to fish husbandry, laboratory maintenance, and their general advice and support on this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) (1998). Toxicological Profile for Chlorinated Dibenzo-p-Dioxins (CDDs). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- Alves M. G., Martins A. D., Cavaco J. E., Socorro S., Oliveira P. F. (2013). Diabetes, insulin-mediated glucose metabolism and Sertoli/blood-testis barrier function. Tissue Barriers 1, e23992.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attina T. M., Hauser R., Sathyanarayana S., Hunt P. A., Bourguignon J.-P., Myers J. P., DiGangi J., Zoeller R. T., Trasande L. (2016). Exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals in the USA: A population-based disease burden and cost analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 4, 996–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aylward L. L., Hays S. M. (2002). Temporal trends in human TCDD body burden: Decreases over three decades and implications for exposure levels. J. Expo. Anal. Environ. Epidemiol. 12, 319–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babicki S., Arndt D., Marcu A., Liang Y., Grant J. R., Maciejewski A., Wishart D. S. (2016). Heatmapper: Web-enabled heat mapping for all. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W147–W153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker B. B., Yee J. S., Meyer D. N., Yang D., Baker T. R. (2016). Histological and transcriptomic changes in male zebrafish testes due to early life exposure to low level 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Zebrafish 13, 413–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker T. R., Peterson R. E., Heideman W. (2013). Early dioxin exposure causes toxic effects in adult zebrafish. Toxicol. Sci. 135, 241–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker T. R., King-Heiden T. C., Peterson R. E., Heideman W. (2014). Dioxin induction of transgenerational inheritance of disease in zebrafish. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 398, 36–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker T. R., Peterson R. E., Heideman W. (2014). Using zebrafish as a model system for studying the transgenerational effects of dioxin. Toxicol. Sci. 138, 403–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman Å., Heindel J. J., Kasten T., Kidd K. A., Jobling S., Neira M., Zoeller R. T., Becher G., Bjerregaard P., Bornman R., et al. (2013). The impact of endocrine disruption: A consensus statement on the state of the science. Environ. Health Perspect. 121, a104–a106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya I., Majumdar S. S. (2015). Male infertility: Present and future. MGM J. Med. Sci. 2, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Brehm E., Rattan S., Gao L., Flaws J. A. (2018). Prenatal exposure to di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate causes long-term transgenerational effects on female reproduction in mice. Endocrinology 159, 795–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer A., Longnecker M. P., Birnbaum L. S., Cogliano J., Kostyniak P., Moore J., Schantz S., Winneke G. (1999). Characterization of potential endocrine-related health effects at low-dose levels of exposure to PCBs. Environ. Health Perspect. 107, 639–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruner-Tran K. L., Osteen K. G. (2011). Developmental exposure to TCDD reduces fertility and negatively affects pregnancy outcomes across multiple generations. Reprod. Toxicol. 31, 344–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruner-Tran K. L., Ding T., Yeoman K. B., Archibong A., Arosh J. A., Osteen K. G. (2014). Developmental exposure of mice to dioxin promotes transgenerational testicular inflammation and an increased risk of preterm birth in unexposed mating partners. PLoS One 9, e105084.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J.-P., Ishibashi T., Takagi Y., Hayakawa H., Sekiguchi M. (2003). Mouse MTH2 protein which prevents mutations caused by 8-oxoguanine nucleotides. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 305, 1073–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chahoud I., Hartmann J., Rune G. M., Neubert D. (1992). Reproductive toxicity and toxicokinetics of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Arch. Toxicol. 66, 567–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y.-M., Pu H.-F., Huang W. J., Ho L.-T., Wang S.-W., Wang P. S. (2011). Role of serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase-1 in regulating torsion-induced apoptosis in rats. Int. J. Androl. 34, 379–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro F., Gonçalves V., Moreira N., Slobodticov J. I., de Andrade Galvão N., de Souza Spinosa H., Bonamin L. V., Bondan E. F., Ciscato C. H. P., Barbosa C. M., et al. (2018). Ivermectin acute administration impaired the spermatogenesis and spermiogenesis of adult rats. Res. Vet. Sci. 117, 178–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denison M. S., Nagy S. R. (2003). Activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor by structurally diverse exogenous and endogenous chemicals. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 43, 309–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckstrum K. S., Edwards W., Banerjee A., Wang W., Flaws J. A., Katzenellenbogen J. A., Kim S. H., Raetzman L. T. (2018). Effects of exposure to the endocrine-disrupting chemical bisphenol a during critical windows of murine pituitary development. Endocrinology 159, 119–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erata G. O., Koçak Toker N., Durlanik O., Kadioğlu A., Aktan G., Aykaç Toker G. (2008). The role of heat shock protein 70 (Hsp 70) in male infertility: Is it a line of defense against sperm DNA fragmentation? Fertil. Steril. 90, 322–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst J., Jann J.-C., Biemann R., Koch H. M., Fischer B. (2014). Effects of the environmental contaminants DEHP and TCDD on estradiol synthesis and aryl hydrocarbon receptor and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor signalling in the human granulosa cell line KGN. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 20, 919–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan C. Y., Pan J., Chu R., Lee D., Kluckman K. D., Usuda N., Singh I., Yeldandi A. V., Rao M. S., Maeda N., et al. (1996). Targeted disruption of the peroxisomal fatty acyl-CoA oxidase gene: Generation of a mouse model of pseudoneonatal adrenoleukodystrophy. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 804, 530–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filho D. W., Torres M. A., Bordin A. L. B., Crezcynski-Pasa T. B., Boveris A. (2004). Spermatic cord torsion, reactive oxygen and nitrogen species and ischemia—reperfusion injury. Mol. Aspects Med. 25, 199–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore A. C., Chappell V. A., Fenton S. E., Flaws J. A., Nadal A., Prins G. S., Toppari J., Zoeller R. T. (2015). Executive summary to EDC-2: The Endocrine Society’s Second Scientific Statement on Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals. Endocr. Rev. 36, 593–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermsen S. A. B., Larsson S., Arima A., Muneoka A., Ihara T., Sumida H., Fukusato T., Kubota S., Yasuda M., Lind P. M. (2008). In utero and lactational exposure to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) affects bone tissue in rhesus monkeys. Toxicology 253, 147–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung M. W., Spitsbergen J. M., Peterson R. E. (1999). 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin alters cardiovascular and craniofacial development and function in sac fry of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Toxicol. Sci. 47, 40–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J., Zhang N., Shiba H., Li L., Wang Z. (2013). Spermatogenesis associated 4 promotes sertoli cell proliferation modulated negatively by regulatory factor X1. PLoS ONE 8, e75933.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J., Li L., Xie M., Fuji R., Liu S., Yin X., Li G., Wang Z. (2015). SPATA4 Counteracts etoposide-induced Apoptosis via modulating Bcl-2 family proteins in HeLa cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 38, 1458–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L., Zhang J., Wang J.-J., Wang L., Zhang L., Li G., Yang X., Ma X., Sun X., Cai J., et al. (2013). Sperm, but not oocyte, DNA methylome is inherited by zebrafish early embryos. Cell 153, 773–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R., Wolf J., Braunbeck T. (2009). OECD Guidance Document for the Diagnosis of Endocrine-Related Histopathology of Fish Gonads. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. [Google Scholar]

- Kortenkamp A. (2014). Low dose mixture effects of endocrine disrupters and their implications for regulatory thresholds in chemical risk assessment. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 19, 105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanham K. A., Peterson R. E., Heideman W. (2012). Sensitivity to dioxin decreases as zebrafish mature. Toxicol. Sci. 127, 360–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latchoumycandane C., Chitra K. C., Mathur P. P. (2003). 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) induces oxidative stress in the epididymis and epididymal sperm of adult rats. Arch. Toxicol. 77, 280–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Zhu L., Zha J., Wang Z. (2014). Effects of decabromodiphenyl ether (BDE-209) on mRNA transcription of thyroid hormone pathway and spermatogenesis associated genes in Chinese rare minnow (Gobiocypris rarus). Environ. Toxicol. 29, 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loveland K. L., Klein B., Pueschl D., Indumathy S., Bergmann M., Loveland B. E., Hedger M. P., Schuppe H.-C. (2017). Cytokines in male fertility and reproductive pathologies: Immunoregulation and Beyond. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 8, 307.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo K., Li Y., Xia L., Hu W., Gao W., Guo L., Tian G., Qi Z., Yuan H., Xu Q. (2017). Analysis of the expression patterns of the novel large multigene TRIM gene family (finTRIM) in zebrafish. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 66, 224–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manikkam M., Guerrero-Bosagna C., Tracey R., Haque M. M., Skinner M. K. (2012). Transgenerational actions of environmental compounds on reproductive disease and identification of epigenetic biomarkers of ancestral exposures. PLoS One 7, e31901.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manikkam M., Tracey R., Guerrero-Bosagna C., Skinner M. K. (2013). Plastics derived endocrine disruptors (BPA, DEHP and DBP) induce epigenetic transgenerational inheritance of obesity, reproductive disease and sperm epimutations. PLoS One 8, e55387.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer M. P., Bukau B. (2005). Hsp70 chaperones: Cellular functions and molecular mechanism. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62, 670–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mocarelli P., Gerthoux P. M., Patterson D. G., Milani S., Limonta G., Bertona M., Signorini S., Tramacere P., Colombo L., Crespi C., et al. (2007). Dioxin exposure, from infancy through puberty, produces endocrine disruption and affects human semen quality. Environ. Health Perspect. 116, 70–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okey A. B. (2007). An aryl hydrocarbon receptor odyssey to the shores of toxicology: The Deichmann Lecture, International Congress of Toxicology-XI. Toxicol. Sci. 98, 5–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson R. T., Macrae C. A. (2012). Systematic approaches to toxicology in the zebrafish. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 52, 433–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakhshandehroo M., Knoch B., Müller M., Kersten S. (2010). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha target genes. PPAR Res. 2010, 1.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanabria M., Cucielo M. S., Guerra M. T., Dos Santos Borges C., Banzato T. P., Perobelli J. E., Leite G. A. A., Anselmo-Franci J. A., De Grava Kempinas W. (2016). Sperm quality and fertility in rats after prenatal exposure to low doses of TCDD: a three-generation study. Reprod. Toxicol. 65, 29–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuppe H.-C., Meinhardt A., Allam J. P., Bergmann M., Weidner W., Haidl G. (2008). Chronic orchitis: A neglected cause of male infertility? Andrologia 40, 84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaban Z., El-Shazly S., Abdelhady S., Fattouh I., Muzandu K., Ishizuka M., Kimura K., Kazusaka A., Fujita S. (2004). Down regulation of hepatic PPARalpha function by AhR ligand. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 66, 1377–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner M. K., Haque C. G.-B. M., Nilsson E., Bhandari R., McCarrey J. R. (2013). Environmentally induced transgenerational epigenetic reprogramming of primordial germ cells and the subsequent germ line. PLoS One 8, e66318.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele G., Stehr-Green P., Welty E. (1986). Estimates of the biologic half-life of polychlorinated biphenyls in human serum. N. Engl. J. Med. 314, 926–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teraoka H., Dong W., Hiraga T. (2003). Zebrafish as a novel experimental model for developmental toxicology. Congenit. Anom. (Kyoto) 43, 123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremellen K. (2008). Oxidative stress and male infertility–a clinical perspective. Hum. Reprod. Update 14, 243–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerfield M. (2000). The Zebrafish Book. A Guide for the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish (Danio Rerio), 4th ed University of Oregon Press, Eugene. [Google Scholar]

- Welshons W. V., Thayer K. A., Judy B. M., Taylor J. A., Curran E. M., vom Saal F. S. (2003). Large effects from small exposures. I. Mechanisms for endocrine-disrupting chemicals with estrogenic activity. Environ. Health Perspect. 111, 994–1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng J., Deng S., Wang Y., Li P., Tang L., Pang Y. (2017). Specific inhibition of acyl-CoA oxidase-1 by an acetylenic acid improves hepatic lipid and reactive oxygen species (ROS) metabolism in rats fed a high fat diet. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 3800–3809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao F., Jiang G., Wei P., Wang H., Ru S. (2018). Bisphenol S exposure impairs glucose homeostasis in male zebrafish (Danio rerio). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 147, 794–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoeller R. T., Brown T. R., Doan L. L., Gore A. C., Skakkebaek N. E., Soto A. M., Woodruff T. J., Saal V., S F. (2012). Endocrine-disrupting chemicals and public health protection: A statement of principles from the Endocrine Society. Endocrinology 153, 4097–4110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.