The MiR-146a/TRAF6/NF-κB axis is important for the regulation of hematopoiesis and the immune system.

The MiR-146a/TRAF6/NF-κB axis is important for the regulation of hematopoiesis and the immune system.

Abstract

The MiR-146a/TRAF6/NF-κB axis is important for the regulation of hematopoiesis and the immune system. To identify the key axis that regulates benzene-induced hematotoxicity or even leukemia, we investigated miR-146a expression in human CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) and human acute promyelocytic leukemia cells (HL-60) during the differentiation process. By performing a colony formation assay and flow cytometry on cells in the differentiation process after hydroquinone treatment, we found that hydroquinone induced a marked reduction of differentiation toward myeloid cells and immune cells in CD34+ cells (5 days exposure) as well as in HL-60 cells (3 h exposure). Further study using real-time PCR and western blot showed that the impaired myeloid differentiation was accompanied by the up-regulation of miR-146a and the down-regulation of TRAF6 and NF-κB. Using the miR-146a-5p inhibitor to suppress miR-146a expression could relieve the inhibitory effect on myeloid differentiation induced by hydroquinone to a certain extent. At the same time, the level of TRAF6 protein, as well as the phosphorylated IκBα protein which indicates NF-κB transcriptional activity was restored to the same levels as the control group. These results suggested that hydroquinone induced a dysregulation of miR-146a and its downstream NF-κB transcriptional factor pathway, which might be an early event in the generation of benzene-induced differentiation disturbance and subsequent leukemogenesis.

1. Introduction

Benzene, which is an important industrial material and a ubiquitous environmental contaminant, affects people in many fields of industry including luggage jobs, leather mills, paint factories, and petroleum chemical plants.1 Benzene exposure can induce leukemia, such as acute myeloid leukemia, acute and chronic lymphocytic leukemia, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, multiple myeloma and aplastic anemia. The mechanism of benzene hematotoxicity has not been fully elucidated, but the current research consensus is that the active metabolites derived from benzene are the ultimate toxicants and cause bone marrow toxicity and leukemia. Hydroquinone, one of the main metabolites of benzene, has been confirmed to cause genetic damage.2,3 There is evidence that hydroquinone can interfere with the differentiation of hematopoietic cells,4–6 which has been considered to be one of the direct causes of benzene hematotoxicity.

Small non-coding RNA molecules such as microRNAs are one kind of the important epigenetic regulatory molecules that can regulate the expression of more than one third of human genes by inhibiting mRNA translation or degrading them at the post-transcriptional stage.7 The regulation of microRNAs is involved in many biological processes, including growth and development, cell proliferation and apoptosis, cell metabolism and cell differentiation.8 MicroRNAs are also closely associated with the toxic effects of chemical substances such as benzopyrene9 and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).10 A growing number of studies11–13 show that aberrant expression of microRNAs is related to the development of hematopoietic disorders. MiR-146a, a member of the miR-146 miRNA family located on chromosome 5, serves as a negative feedback regulator of two Toll-like receptor downstream adapter proteins, together with TRAF6 (TNF receptor-associated factor 6) and IRAK1 (IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 1). MiR-146a also participates in the regulation of NF-κB transcriptional activity which plays an important role in the process of hematopoietic cell differentiation and cellular immunity.14–17 The abnormal expression of miR-146a, TRAF6 and changes in NF-κB transcriptional activity are frequently seen in a variety of blood diseases, such as myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS),18,19 myeloproliferative disorders, myeloid sarcoma and lymphoma.

In view of this evidence, we speculated that the miR-146a/TRAF6/NF-κB axis might also be involved in the regulation of hematotoxicity induced by benzene. In this study, we aimed to investigate the role of miR-146a in hematopoietic progenitor cell (HPC) differentiation induced by hydroquinone in vitro. Our results demonstrate that the miR-146a/TRAF6/NF-κB axis plays a role in benzene induced hematotoxicity.

2. Materials and methods

2a. Antibodies and reagents

Alexa fluor 488-CD11b, PE-CD14, APC-CD15, FITC-CD33, FITC-CD34, FITC-CD71 and their corresponding isotype control antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences. PE-CD235a and its corresponding isotype control antibody were purchased from eBiosciences. Anti-human NF-κB P65, anti-human TRAF6, anti-human IκB-α and HRP-conjugated secondary antibody were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA. Anti-human Phospho-IκBα, anti-human β-actin and anti-human Histone H3 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, USA. Anti-human GAPDH was purchased from Proteintech.

Ficoll-Paque Plus was purchased from GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK. MACS CD34 progenitor isolation kit was purchased from Miltenyi Biotech, Inc., Auburn, CA. Stem Cell Growth Factors (SGF), interleukin-3 (IL-3), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), and erythropoietin (EPO) were purchased from Peprotech, London, UK. 12-Myristate13-acetate (PMA) was purchased from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, China. Iscove's Modified Dulbecco's Medium was purchased from Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA. Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was purchased from Gibco Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA. StemMACS HSC-CFU Media was purchased from Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany. Nuclear and cytoplasmic protein extraction kit and BCA protein assay kit were purchased from Beyotime institute of biotechnology, China.

2b. Cord blood samples

Cord blood was obtained with informed consent from healthy pregnant woman of spontaneous full-term delivery. Then HPCs were isolated from these umbilical cord blood samples. All samples were negative for HIV, CMV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C. All experiments were performed in compliance with the relevant laws and institutional guidelines, and were approved by the Ethics Review Committee on Biomedical Research of the School of Public Health, Sun Yat-sen University.

2c. CD34+ HPCs isolation, culture and hydroquinone treatment

Mononuclear cells (MNCs) were isolated from umbilical cord blood using Ficoll-Paque Plus density gradient centrifugation. CD34+ cells were isolated using the MACS CD34 progenitor isolation kit using immunomagnetic beads followed a protocol described previously.20 The purity of the isolated CD34+ cells was determined using flow cytometric analysis and routinely ranged from 90–99%. The CD34+ cells were seeded into complete medium immediately after isolation and were cultured for 24 h. The complete culture media consisted of Iscove's Modified Dulbecco's Medium with 30% FBS, 100 U mL–1 penicillin, 100 μg mL–1 streptomycin, 50 ng mL–1 SCF, 20 ng mL–1 IL-3, 20 ng mL–1 GM-CSF, 50 ng mL–1 G-CSF and 3 U mL–1 EPO.

Based on the results from Kerzic P. J. et al. hydroquinone dissolved in PBS (PH 7.4) was added to the complete medium to reach final concentrations of 0, 1.0, 2.5 and 5.0 μM after the initiation of culture.21 Cells were harvested at 5 days, 8 days and 12 days to detect related indicators.22,23 During the 12 days period, cultures were maintained by addition of fresh medium and hydroquinone.

2d. HL-60 cell culture, transfection and hydroquinone treatment

Human promyelocytic leukemia cells (HL-60) cells were incubated in complete medium consisting of RPMI 1640, 10% FBS, 100 U per mL penicillin and 100 μg per mL streptomycin at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. For this experiment, a miR-146a-5p inhibitor was synthesized by RiboBio Co. Ltd (Guangzhou, China). Transfection of the inhibitor was performed using Lipofectamine™ RNAiMAX (Invitrogen, Life Technologies Co., Branford USA). The silencing efficiency, determined by qRT-PCR analysis, was approximately 85% for HL-60 cells. After that the transfected cells were exposed to various doses of hydroquinone (0, 0.5, 1.0, 2.5 and 5.0 μM) for 3 h according to Oliveira,6 and then washed with PBS to eliminate any remaining hydroquinone and induced to differentiate towards monocytes/macrophages for 72 h using 20 nM Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA). The cells were harvested for further assays.

2e. Colony-forming unit (CFU) assay

CD34+ HPCs were resuspended in Iscove's Modified Dulbecco's Medium (IMDM) supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum at 5000 cells per 1 mL of medium. About 0.3 mL of cell suspension was added to 3 mL of StemMACS HSC-CFU Media containing IMDM, 1% methylcellulose, 30% fetal bovine serum, 1% bovine serum albumin, l-glutamine (2 mM), 2-mercaptoethanol (0.1 mM), stem cell factor (SCF; 50 ng ml–1), interleukin-3 (IL-3; 20 ng mL–1), interleukin-6 (IL-6; 20 ng mL–1), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF; 20 ng mL–1), granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF; 20 ng mL–1) and erythrogenin (EPO; 3U mL–1). The mixtures were vortexed vigorously and then stood for 10 min to allow bubbles to dissipate. The cell suspension was dispensed into three 35 mm dishes for one triplicate assay at a volume of 1.1 mL per dish via a syringe with needles. All dishes were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 12 days, at which time colonies were identified and scored under an inverted fluorescence microscope.

2f. Flow cytometric analysis

To confirm the purity of the isolated CD34+ cells and the surface markers in differentiated cells, single cell suspensions were resuspended at approximately 2–5 × 105 cells per ml in PBS containing 1% FBS and stained with anti-human antibodies for 30 min at 4 °C. The cells were washed and analyzed using a Gallios flow cytometer using isotype staining as a control for nonspecific binding. The antibody cocktails consisted of Alexa fluor 488-CD11b, PE-CD14, APC-CD15, FITC-CD33, FITC-CD34, FITC-CD71 and PE-CD235a.

2g. RNA extraction and real-time quantitative PCR analysis

For gene-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR), total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent from cultured cells following the manufacturer's recommended protocol. Reverse transcription was performed using a PrimeScript™ RT reagent, and the real-time quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using a SYBR Green PCR Master Mix on the ABI Viia7 Detection System. The primer sequences are shown in ESI 1.†

2h. Protein extraction and western blot analysis

Cells were harvested and washed twice with ice-cold PBS. Total cellular protein was prepared using an SDS lysis buffer supplemented with 1% phosphatase inhibitors, while the cytoplasmic protein lysate and nuclear protein lysate were separated using a Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Protein Extraction Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. The protein concentrations were quantified using a BCA Protein assay Kit. An aliquot of prepared proteins was processed using 10% SDS-polyacrylamide separating gels and 5% stacking gels, and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were hybridized with the following primary antibodies: anti-human NF-κB P65 (1 : 3000), anti-human TRAF6 (1 : 2000), anti-human IκB-α (1 : 2000), anti-human Phospho-IκBα (1 : 1000), anti-human β-actin (1 : 10 000), anti-human Histone H3 (1 : 2000) and anti-human GAPDH (1 : 30 000). After washing in PBST three times, the membranes were further incubated with a HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1 : 2000) diluted in 2.5% non-fat milk-PBST. The activity of horseradish peroxidase which was bound to the secondary antibody was detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence method after washing off the unbound secondary antibody. Western blotting of β-actin, GAPDH and Histone H3 were performed to confirm the amounts of loaded total protein, cytoplasmic protein and nuclear protein, respectively. Protein expression levels were determined by analyzing mean gray values of optical signals captured on the sensitive films using Gel-Pro analyzer software.

3. Results

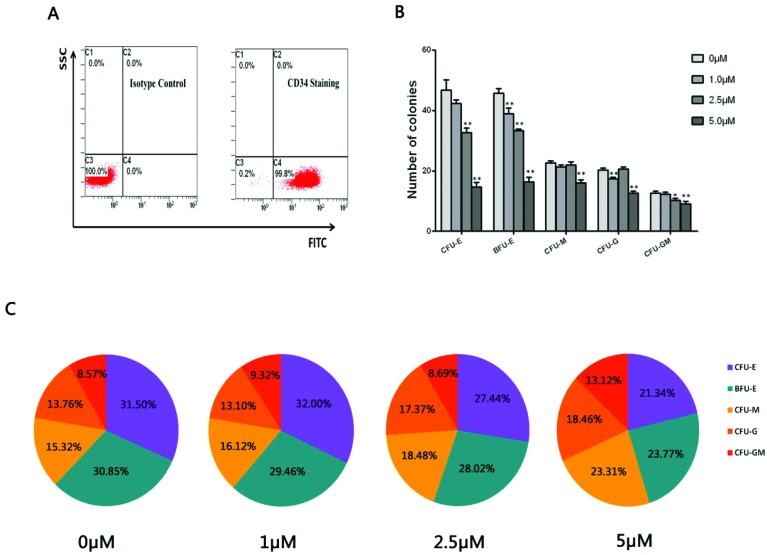

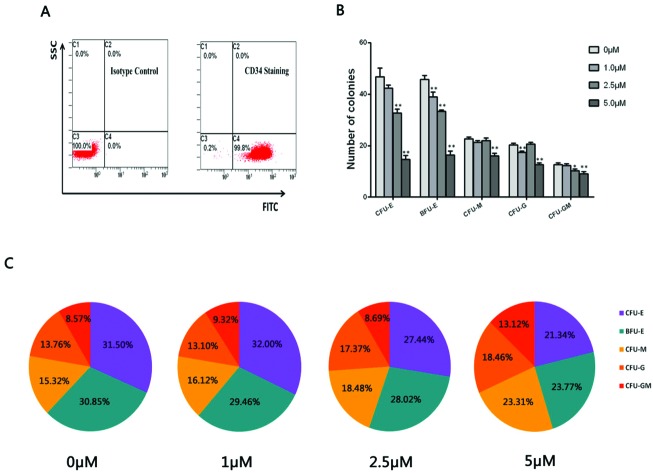

3a. Hydroquinone inhibited CD34+ HPCs colony formation

Flow cytometric analysis was performed to detect the purity of CD34+ HPCs through inspecting the CD34 membrane antigen expression positive rate. A representative FACS analysis showed the CD34+ purity was above 99% as presented in Fig. 1A. A CFU assay was performed to observe the colony formation of CD34+ HPCs (the colony-forming unit pictures are shown in ESI 2†). As shown in Fig. 1B, there was a decrease in erythroid and myeloid cell colonies including CFU-E, BFU-E, CFU-M, CFU-G and CFU-GM colonies in the hydroquinone treatment groups compared with the control group (P < 0.01). Concomitantly a more obvious decrease in numbers of erythroid colony BFU-E and CFU-E colonies was observed, suggesting varying degrees of inhibitory effects on colony formation after various doses of hydroquinone treatment. Via in-depth analysis, we established that myeloid cells derived colony CFU-M, CFU-G and CFU-GM colonies exhibited a gradual change in proportions in the presence of the hydroquinone treatment (P < 0.01), while the erythroid colony CFU-E and BFU-E colonies exhibited a gradually decreasing proportion along with the increasing dose of hydroquinone (P < 0.01) (Fig. 1C). Taken together, hydroquinone inhibited erythroid cell colony formation and promoted myeloid cell colony formation in vitro, suggested hydroquinone exposure could cause HPCs functional damage and an altered erythroid-myeloid differentiation program.

Fig. 1. Flow cytometry detected the purity of CD34+ cells isolated from umbilical cord blood and colony formation of CD34+ HPCs cultured in vitro. CD34+ purity identification of enriched cells through immunomagnetic separation was up to 99.8% as detected by flow cytometry (A). CD34+ HPCs were treated with different doses of hydroquinone and plated in triplicate in a semi-solid methylcellulose culture for colony-forming cell (CFC) assays and absolute numbers of colonies were counted 12 days after initiating seeding. The content and proportions of each category of colony in each treatment group were calculated after 12 days of culture. The results show a substantially reduced number of colonies in a dose dependent manner, especially the CFU-E and BFU-M in both the number of clones (B) and clone percentage (C). Data represent the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (Student's t test).

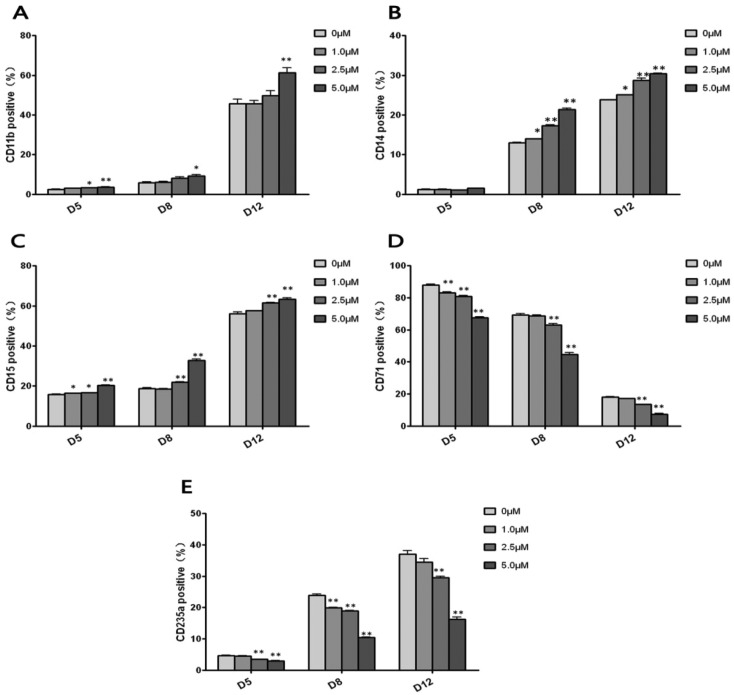

3b. Hydroquinone suppressed hematopoietic cells generation and differentiation

To investigate whether hydroquinone induces dynamic differentiation of hematopoietic cells, we performed flow cytometric assays to evaluate the generations of multi-lineage hematopoietic cells at different time points (5 days, 8 days, 12 days) after different concentrations of hydroquinone treatment. In this study, to identify myeloid cell, monocyte-macrophage, granulocyte and erythrocyte development, the surface markers CD11b, CD14, CD15, CD71 and CD235a were adopted to identify the differentiation of CD34+ HPCs. As shown in Fig. 2A–C, CD11b+, CD14+, and CD15+ cells increased in a dose dependent and time dependent manner (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01), while the proportion of CD71+ cells decreased in a dose dependent and time dependent manner (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2D). Although the CD235a+ cells increased in a time dependent manner, it was obvious that the positive rate was reduced by hydroquinone exposure in a dose dependent manner at 5 days, 8 days and 12 days (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2E). After 12 days of hydroquinone treatment the HPC, myeloid cell (CD11b+), monocyte-macrophage (CD14+), and granulocyte (CD15+) proportions increased when compared to the control cells, which was consistent with the colony formation results (Fig. 1C). Moreover, the erythroid cells (CD71+, CD235a+) markedly declined, especially in the 5 μM hydroquinone treatment group, the CD71+ and CD235a+ cells decreased by more than 50% compared to the control group (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2D and E). Thus, hydroquinone was able to suppress CD34+ cells proliferation and differentiation in vitro.

Fig. 2. Flow cytometry detected the development of each lineage of hematopoietic cells from CD34+ HPCs induced by hydroquinone. CD34+ HPCs were seeded in complete medium containing 0, 1.0, 2.5 and 5.0 μM hydroquinone and cultured for 12 consecutive days, and cells harvested at three time points (5 days, 8 days and 12 days) were used to analyze the membrane surface antigen expression positive rate by flow cytometry. CD11b (A), CD14 (B), and CD15 (C) were applied for identification of myeloid cell, monocyte-macrophage and granulocyte development, and CD71 (D) and CD235a (E) for erythrocyte development, respectively. With an increase in the culture time, the proportion of CD34+ cells decreased and the proportion of CD11b+, CD14+, CD15+, and CD235+ cells increased gradually, while CD71+ cells decreased significantly in a time dependent manner. Hydroquinone significantly inhibited differentiation of CD34+ cells into CD71+ and CD235+ cells in a dose dependent manner. Data represent the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (Student's t test).

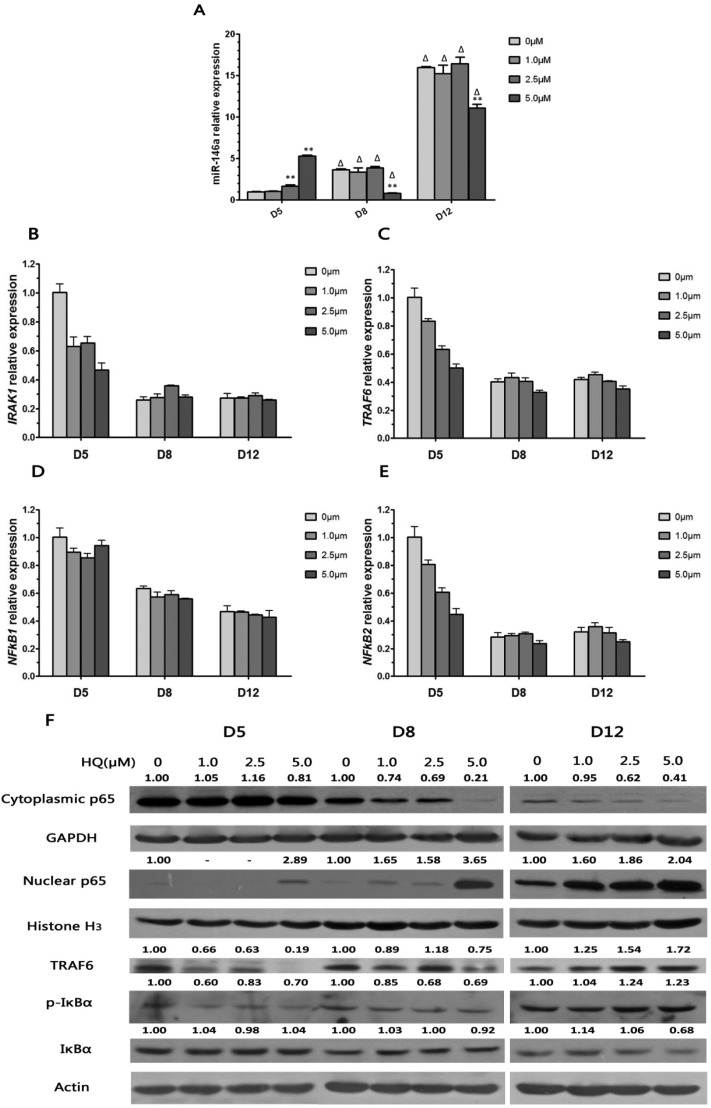

3c. TRAF6, NF-κB signatures in CD34+ HPC differentiation induced by hydroquinone

In order to clarify the mechanism of differentiation inhibition in HPCs induced by hydroquinone, qRT-PCR was firstly performed to detect the mRNA expression level of miR-146a which plays an important role in stem cell differentiation. As shown in Fig. 3A, the expression of miR-146a in CD34+ HPCs markedly increased during hydroquinone suppression of HPC differentiation when compared to the 0 μM hydroquinone treatment cells at 5 days, but it was significantly declined in the 5 μM hydroquinone treatment cells at 8 days (P < 0.01). The relative expression of miR-146a increased to 4 fold at 8 days and reached about 16 fold at 12 days (both P < 0.01) (Fig. 3A). The expression of miR-146a, unlike the results of 8 days and 12 days, was increased in a dose dependent manner at 5 days during CD34+ HPC differentiation after hydroquinone treatment. The expression of miR-146a in the 2.5 μM and 5.0 μM hydroquinone treatment groups was augmented nearly 1 and 4 times more than in the control group at 5 days, respectively (P < 0.01). However, at 8 days and 12 days, the intracellular expression of miR-146a in the 5.0 μM hydroquinone treatment group decreased by 77% and 31% compared to the control group, respectively (both P < 0.01). Altogether, the qRT-PCR results suggested that hydroquinone inhibited the CD34+ HPCs proliferation and differentiation accompanied with an up-regulation in miR-146a expression at the early differentiation stage.

Fig. 3. The expression of miR-146a and its target genes at the mRNA and protein level induced by hydroquinone. CD34+ HPCs were seeded in complete medium containing 0, 1.0, 2.5 and 5.0 μM hydroquinone and cultured for 12 consecutive days. Cells harvested at three time points (5 days, 8 days and 12 days) were used to detect expression levels of miR-146a and its target genes. QRT-PCR results showed that miR-146a expression increased (A) accompanied by its target gene IRAK1 (B), TRAF6 (C) and NF-κB related factors NF-κB1 (D), NF-κB2 (E) expression decreased gradually during CD34+ cell differentiation in a time dependent manner. More notable was that a higher concentration of hydroquinone (2.5 μM and 5.0 μM) could promote miR-146a expression significantly in the early CD34+ HPC differentiation stage (5 days), while producing no significant effect in the late differentiation stages (8 days and 12 days) (A). The expression of the genes IRAK1, TRAF6 and NF-κB2 showed a significant decrease at 5 days in a dose dependent manner, and correspondingly, TRAF6, p-IκBα and nuclear p65 protein expression were reduced (F). Data represent the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (Student's t test).

Next, we explored the target gene expression of miR-146a at the mRNA and protein levels to determine whether they were involved in hydroquinone interference in CD34+ HPCs differentiation in vitro. The CD34+ HPCs without hydroquinone treatment for 5 days served as the control group and the results are shown in Fig. 3B–E. Hydroquinone treatment reduced IRAK1, TRAF6, NF-κB1 and NF-κB2 gene expression at 5 days, and the IRAK1, TRAF6, and NF-κB2 expression at the mRNA level decreased in a dose dependent manner (P < 0.01). Meanwhile, the expression of IRAK1, TRAF6 and NF-κB2 in CD34+ HPCs treated with 5.0 μM hydroquinone declined by 50% as compared to the control group (P < 0.01). The results indicate that the target genes of miR-146a, Toll-like receptor signal transduction and NF-κB transcriptional activity were inhibited by hydroquinone during the early differentiation of CD34+ HPCs. However, the IRAK1, TRAF6, NF-κB1 and NF-κB2 gene expression patterns at 8 days and 12 days were different from those at 5 days. The mRNA expression levels of IRAK1, TRAF6, NF-kB1, NF-kB2 in the CD34+ HPCs decreased significantly at 8 days and 12 days compared to 5 days for the same hydroquinone concentration.

The real-time PCR results partly demonstrate that miR-146a participated in the regulation of CD34+ HPCs differentiation induced by hydroquinone in vitro. Subsequently, we analysed TRAF6, p-IκBα and nuclear p65 expression at the protein level in lysates from cultured CD34+ HPCs by Western blot to verify whether myeloid cell differentiation alteration induced by hydroquinone was related to TRAF6 expression and NF-κB transcriptional activity regulated by miR-146a. In order to identify the status of NF-κB activation, we examined the expression of p65 at the protein level in the nucleus and cytoplasm. The result showed a decrease of 34%, 37% and 81% in the protein level of TRAF6 at 5 days in the hydroquinone treatment groups compared to the control group (Fig. 3F). Correspondingly, the expression of phosphorylated IκBα protein showed a decrease of 40%, 17% and 30% (Fig. 3F). Moreover, cytoplasmic p65 and nuclear p65 protein were almost unchanged except nuclear p65 in the 5.0 μM hydroquinone treatment group, where an increased level was observed (Fig. 3F). It turned out that miR-146a up-regulation suppressed the TRAF6/Toll-like/NF-κB pathway in CD34+ HPCs with hydroquinone treatment at 5 days. On the contrary, a gradual increase in the TRAF6 protein level was observed at 12 days (Fig. 3F). In addition, the expression of phosphorylated IκBα and nuclear p65 protein drastically increased and the expression of cytoplasmic p65 markedly decreased during CD34+ HPCs differentiation induced by hydroquinone. Moreover, the expression of TRAF6, phosphorylated IκBα, cytoplasmic p65 and nuclear p65 changed between 5 days and 12 days (Fig. 3F). Taken together, the data identify that the miR-146a/Toll-like receptors/NF-κB pathway was involved in the differentiation inhibition of CD34+ HPCs during the early differentiation stages induced by hydroquinone in vitro.

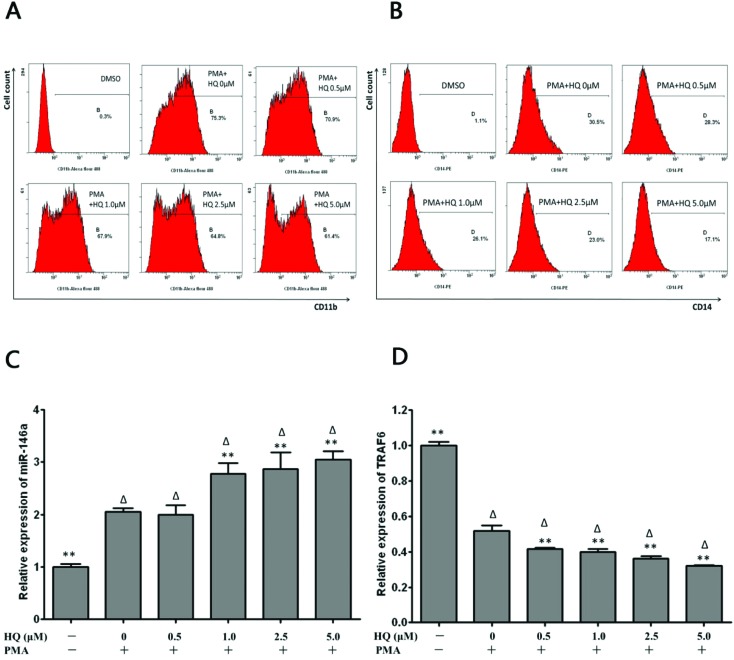

3d. miR-146a silencing attenuated the inhibition of cell differentiation induced by hydroquinone

In order to elucidate our hypothesis that miR-146a played a key role in benzene hematotoxicity, the HL-60 cell served as a cell differentiation model in vitro to explore the miR-146a regulatory effect. We examined the differentiation status of HL-60 cells after a short time (3 h) of hydroquinone treatment according to Oliveira.6 As shown in Fig. 4, the flow cytometer analysis showed a significant increase in the proportion of CD11b+ cells and CD14+ cells in the presence of 20 nM PMA, while hydroquinone treatment for 3 hours significantly reduced this differentiation towards monocytes-macrophages by a diminished proportion of CD11b+ cells and CD14+ cells compared to the control group in a dose dependent manner as shown in Fig. 4A and B.

Fig. 4. The effect of differentiation and expression of miR-146a and TRAF6 in HL-60 cells induced by hydroquinone. (A) CD11b expression was inhibited by hydroquinone after 3 h of exposure. (B) CD14 expression was inhibited by hydroquinone after 3 h of exposure. (C) Hydroquinone up-regulated the expression of miR-146a in HL-60 cells during differentiation after 3 h of exposure. (D) Hydroquinone down-regulated the expression of TRAF6 mRNA in HL-60 cells during differentiation after 3 h of exposure. Data represent the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (Student's t test).

As with miR-146a up-regulation in the HPC differentiation induced by hydroquinone, we also observed high expression when hydroquinone suppressed the HL-60 cell differentiation induced by PMA (Fig. 4C). Compared to the PMA+ HQ– control, the expression level of miR-146a in HL-60 cells which were treated with both PMA and hydroquinone increased by 35.1% (P = 0.002), 39.5% (P = 0.001) and 48.2% (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4C), which was accompanied by a great decrease in TRAF6 mRNA levels (both P < 0.01) (Fig. 4D).

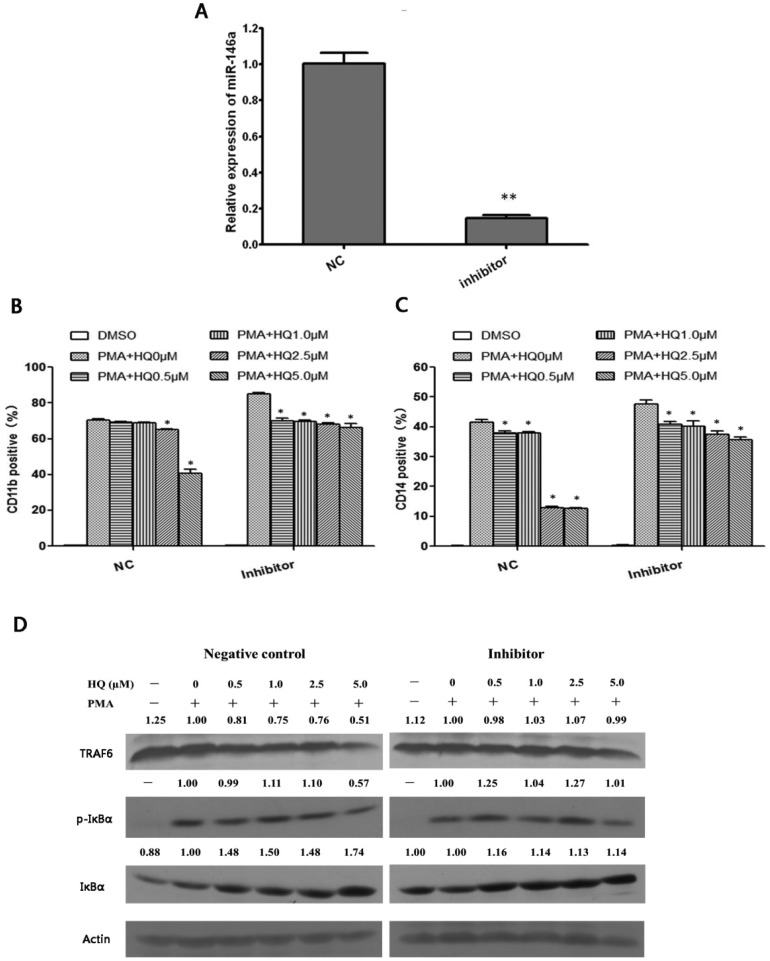

To clarify whether miR-146a mediated hydroquinone inhibition of cell differentiation through the Toll-like receptor signalling pathway, a miR-146a-5p inhibitor was transfected into HL-60 cells and then the differentiation status after PMA induction in the presence of hydroquinone was evaluated. It was observed that inhibition of miR-146a expression (Fig. 5A) reduced the decrease in CD11b+ cells and CD14+ cells compared to the negative control (P < 0.05, Fig. 5B and C).

Fig. 5. Hydroquinone inhibited HL-60 cell differentiation through the miRNA-146a/TRAF6/NF-κB pathway. MiR-146a was successfully inhibited by the inhibitor (A). The expression of CD11b in hydroquinone treated HL-60 cells during differentiation induced by PMA in the absence or presence of miR-146a inhibitors (B). The expression of CD14 in hydroquinone treated HL-60 cells during differentiation induced by PMA in the absence or presence of miR-146a inhibitors (C). TRAF6 protein expression and NF-κB transcriptional activity analysis in treated HL-60 cells during differentiation induced by PMA in the absence or presence of miR-146a inhibitors (D). Data represent the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (Student's t test).

Next, we investigated the expression of TRAF6 and phosphorylated IκBα protein to clarify whether the Toll-like receptor/NF-κB pathway was involved in inhibition of HL-60 cell differentiation towards monocytes-macrophages induced by hydroquinone. As shown in Fig. 5D, hydroquinone could induce a gradual decrease in TRAF6 protein in a dose dependent manner, with the maximum decrease at approximately 49% in the 5.0 μM of hydroquinone treatment group compared to the negative control group. Correspondingly, the levels of IκBα protein showed elevation to 48%, 50%, 48% and 74%. But the level of phosphorylated IκBα protein remained unchanged except a 43% decrease in the 5.0 μM hydroquinone treatment group (Fig. 5D, left). The results implied that NF-κB activation was inhibited by hydroquinone in the HL-60 cells. In contrast, the effects observed in the negative control group were abrogated upon inhibition of miR-146a. We found that the inhibition of miR-146a caused the expression level of TRAF6 protein to recover to the levels of the control (PMA+HQ–). Furthermore, compared to the control (PMA+ HQ–), the level of phosphorylated IκBα protein expression increased by 25%, 4%, 27%, and 1%, and the level of total IκBα protein increased by 16%, 14%, 13%, and 14% (Fig. 5D, right). Taken together, the miR-146a/Toll-like receptor/NF-κB pathway is involved in the inhibition of HL-60 cell differentiation towards monocytes-macrophages induced by hydroquinone.

4. Discussion

Benzene poses a significant health concern as an industrial chemical as well as an environmental contaminant. The most severe damage to human health associated with chronic benzene exposure is hematological system damage, including aplastic anemia, a decrease in peripheral blood cells, myelodysplastic syndrome, acute and chronic myeloid leukemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and possibly multiple myeloma.24 The understanding of how benzene and its metabolites affect the hematological system will contribute to an earlier prediction of toxicity and better prevention of adverse health outcomes. In this study, we identified a negative feedback mechanism involving the miR-146a/TRAF6/NF-κB axis in inhibiting CD34+ and HL-60 cell differentiation induced by hydroquinone. Our findings show a potential epigenetic marker, whereby changes in miR-146a expression might be an early event in the benzene-induced disorder of HPC differentiation and subsequent leukemogenesis.

MiR-146a, one member of the miR-146 family, acts as a guardian of hematopoietic stem cell proliferation and differentiation.25 The expression of miR-146a in bone marrow mononuclear cells in patients with an undifferentiated type of acute myeloid leukemia (FAB type M1) is 6 times higher than those who suffer from acute monocytic leukemia (FAB type M5), revealing that high expression of miR-146a may inhibit tissue cell differentiation, to cause maintenance of a poorly differentiated immature state.26 Hematopoietic stem cells with a high expression of miR-146a could significantly reduce their differentiation to red blood cells and lymphocytes, and their survival is also decreased. The loss of miR-146a expression may lead to bone marrow tumors, inflammatory cell infiltration, hepatosplenomegaly and other symptoms of the liver and spleen.27 Furthermore, expression and function abnormalities of miR-146a are also reported as a consequence of pollutant exposure such as cigarette smoke28,29 and cooking oil fumes.30 This causes us to speculate that miR-146a may also be a target molecule influenced by benzene in the context of occupational exposure and environmental pollution. In this study we found that hydroquinone inhibited HPCs at the early stages of their differentiation along with causing changes in the expression of miR-146a, and this phenomenon was also observed in the PMA induced HL-60 cell differentiation. Interestingly, the inhibitory effect of hydroquinone on the differentiation decreased when the expression of miR-146a was blocked in HL-60 cells. These results indicate that miR-146a is involved in the inhibition of HPC differentiation induced by hydroquinone in vitro. Inflammatory factors such as IL-1,31 IL-6,32 and IL-8,33 which are correlated with immune cell activation and differentiation, are target molecules which are induced by benzene as reported by many researchers. Furthermore, such cytokines are also downstream response factors of miR-146a.34,35 Thus, whether there is a mechanistic link between hydroquinone, miR-146a, inflammatory factor release and immune cell differentiation still needs to be further explored.

When CD34+ cells are cultured in vitro at 5 days, the ratio of CD34+ cells decreases to 50%, at 8 days to 20%, and almost no CD34+ cells are detected at 12 days,23 so the key period for the differentiation of CD34+ cells is the first five days. Hydroquinone can interfere with the differentiation and proliferation of CD34+ cells, leading to abnormal differentiation and proliferation disorders. Our study was mainly concerned with the effect of hydroquinone on the cell differentiation and explored the related mechanism, thus the validation of differentiation inhibition by hydroquinone in HL-60 cells took only a short time. Recent research shows that miR-146a can target binding to TRAF6 and IRAK1, which are upstream regulatory proteins of the NF-κB transcription factor, forming a negative feedback regulatory pathway of the proliferation and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells as well as the development of hematological malignancies.25,36 During the early differentiation of HPCs in vitro, hydroquinone prompted an up-regulation of miR-146a expression, and then inhibited IARK1 and TRAF6 protein expression, thereby blocking the NF-κB signaling pathway, ultimately resulting in the low differentiation state of the cells.26 The human acute myeloid leukemia cell line (HL-60 cells) can be induced by a variety of inducing agents to differentiate into monocytes, macrophages and granulocytes. Hydroquinone was also able, through a similar pathway, to up-regulate miR-146a expression and further inhibit the TRAF6/NF-kB signaling pathway to impair the differentiation of HL-60 cells into granulocyte-macrophage cells induced by PMA. Therefore, it could be considered that hydroquinone up-regulated miR-146a expression and thereby inhibited the TRAF6/NF-kB signaling pathway to affect the early stage of the hematopoietic progenitor cell differentiation.

Interestingly, we observed a decline in miR-146a expression at 8 days and 12 days in a dose dependent manner, which might be involved with the increased expression of TRAF6 and the enhanced transcriptional activity of NF-κB. MiR-146a is a negative regulator of TRAF6, IRAK1 and NF-κB signaling pathway. The reduced expression of miR-146a partially relieved the inhibitory effect on its downstream target genes TRAF6 and IRAK1. And the inhibitory effect of the NF-κB signaling pathway was decreased after miR-146a subsequently down-regulated its expression. At the same time, with the extension of the cell culture and differentiation period, TRAF6 expression and NF-κB activity were enhanced along with the increased percentages of myeloid immune cells in these relatively mature cells through the action of hydroquinone, which was similar to the molecular events observed in mice suffering from inflammatory cell infiltration, hepatosplenomegaly and even more serious acute myeloid leukemia when TRAF6 was overexpressed.36 The overexpression of TRAF6 in hematopoietic stem cells could increase the probability of suffering from acute myeloid leukemia in mice.25 Innate immune activation and differentiation disorders have been implicated in hematological neoplasms and solid tumors as evidenced by recent research.37,38 Innate immune cells play a pro-inflammatory role in cancer mainly through the secretion of cytokines, chemotactic factors, matrix metalloproteinases, and producing ROS. For example, macrophages can secrete MMP9 (matrix metalloproteinases 9), MMP7 (matrix metalloproteinases 7) and COX2 (cytochrome c oxidase subunit 2) to promote cell proliferation and angiogenesis, and tumor formation.39 While granulocytes can induce the production of ROS and activation of related transcription factors to promote the proliferation of tumor cells.40 In addition, innate immune cells can secrete a lot of cytokines such as TNFα and IL-6 which can promote the activation of NF-κB and STAT3 transcription factors and the proliferation of tumor cells. Toll like receptor 4, a classic innate cell immune activation receptor resident in the upstream position of TRAF6, has been found to undergo intensified expression in bone marrow cells and CD34+ cells derived from MDS patients,41,42 demonstrating that Toll like receptor mediated immune cell abnormalities participate in malignant transformation of the hematopoietic system. These findings might be attributed to the down-regulation of miR-146a, and the increase in TRAF6 and NF-κB, thus leading to an enhanced Toll like receptor signal transduction and eventually excessive immune cell generation which is different from the early stage of differentiation. This could be an early event in the malignant transformation of the hematopoietic system.

In conclusion, the data we present above demonstrate that the exogenous chemical benzene and its metabolites exert inhibitory effects on hematopoietic progenitor cell differentiation at an early stage to maintain them in an early state of differentiation through the TRAF6/NF-kB signaling pathway. Because of the inhibition of differentiation by the action of hydroquinone, the percentages of myeloid immune cells increased and innate immune cell activation at the later stage of cell differentiation might contribute to the malignant transformation of the hematopoietic system. Therefore, the miR-146a/TRAF6/NF-κB axis participated in the hematopoietic toxicity induced by benzene, regardless of the stage of differentiation of the hematopoietic progenitor cells. Abnormal expression of miR-146a may be an early molecular event through which benzene exerts influence on the bone marrow cells, and is expected to be a target of the treatment of benzene poisoning.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (81372962, 81402658), the key Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (81430079) and the National “Twelfth Five-Year” Plan for Science & Technology (2014BAI12B01).

Footnotes

†Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/c5tx00419e

References

- McHale C. M., Zhang L., Smith M. T. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:240–252. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedli C. C., Rao N. R., Reuhl K. R., Witmer C. M., Snyder R. Arch. Toxicol. 1996;70:135–144. doi: 10.1007/s002040050252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. T., Zhang L., Jeng M., Wang Y., Guo W., Duramad P., Hubbard A. E., Hofstadler G., Holland N. T. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:1485–1490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazel B. A., Baum C., Kalf G. F. Stem Cells. 1996;14:730–742. doi: 10.1002/stem.140730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X. R., Xue M., Li X. F., Wang Y., Wang J., Han Q. L., Yi Z. C. Toxicol. Lett. 2011;203:190–199. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira N. L., Kalf G. Blood. 1992;79:627–633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis B. P., Burge C. B., Bartel D. P. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calin G. A., Croce C. M. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:857–866. doi: 10.1038/nrc1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D., Wang Q., Liu C., Duan H., Zeng X., Zhang B., Li X., Zhao J., Tang S., Li Z., Xing X., Yang P., Chen L., Zeng J., Zhu X., Zhang S., Zhang Z., Ma L., He Z., Wang E., Xiao Y., Zheng Y., Chen W. Toxicol. Sci. 2012;125:382–391. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Q., Huang S., Zhang X., Zhang W., Feng J., Wang T., Hu D., Guan L., Li J., Dai X., Deng H., Zhang X., Wu T. Environ. Health Perspect. 2014;122:719–725. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1307080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi S., Lu J., Sun M., Li Z., Zhang H., Neilly M. B., Wang Y., Qian Z., Jin J., Zhang Y., Bohlander S. K., Le Beau M. M., Larson R. A., Golub T. R., Rowley J. D., Chen J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:19971–19976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709313104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazi F., Racanicchi S., Zardo G., Starnes L. M., Mancini M., Travaglini L., Diverio D., Ammatuna E., Cimino G., Lo-Coco F., Grignani F., Nervi C. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:457–466. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgantas 3rd R. W., Hildreth R., Morisot S., Alder J., Liu C. G., Heimfeld S., Calin G. A., Croce C. M., Civin C. I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:2750–2755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610983104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltran J. A., Peek J., Chang S. L. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2006;6:1331–1340. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2006.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anfernee Kai-Wing T., Chi-Keung W., Xiao-Ling S., Guo-Yuan Z., Hon-Yeung C., Mengsu Y., Wang-Fun F. Exp. Cell Res. 2007;313:1722–1734. [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. P., Su Y. C., Hu C. W., Lei H. Y. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20:515–523. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. P., Su Y. C., Lee P. H., Lei H. Y. Autophagy. 2013;9:619–621. doi: 10.4161/auto.23546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starczynowski D. T., Fargiropoulos K. Nat. Med. 2010;16:49–58. doi: 10.1038/nm.2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starczynowski D. T., Kuchenbauer F., Wegrzyn J., Rouhi A., Petriv O., Hansen C. L., Humphries R. K., Karsan A. Exp. Hematol. 2011;39:167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiroto A., Kazumi Y., Piernicola B., Yan Z., Ronald H., Nadim M. Blood. 2007;109:3570–3578. [Google Scholar]

- Kerzic P. J., Pyatt D. W., Zheng J. H., Gross S. A., Le A., Irons R. D. Toxicology. 2003;187:127–137. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(03)00064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faivre L., Parietti V., Sineriz F., Chantepie S., Gilbert-Sirieix M., Albanese P., Larghero J., Vanneaux V. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2016;7:3. doi: 10.1186/s13287-015-0267-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler B., Testa U., Condorelli G., Vitelli L., Valtieri M., Peschle C. Stem Cells. 1998;16(Suppl 1):51–73. doi: 10.1002/stem.5530160808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes R. B., Songnian Y., Dosemeci M., Linet M. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2001;40:117–126. doi: 10.1002/ajim.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J. L., Rao D. S., Oconnell R. M., Garcia-Flores Y., Baltimore D. Elife. 2013;2:228–235. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labbaye C., Testa U. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2012;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SM P., A Q.-C. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2010:10. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan J. A., Zago M., Nair P., Li P. Z., Bourbeau J., Tan W. C., Hamid Q., Eidelman D. H., Benedetti A. L., Baglole C. J. Respir. Res. 2015:16. doi: 10.1186/s12931-015-0214-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrijens K., Bollati V., Nawrot T. S. Environ. Health Perspect. 2015;123:399–411. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1408459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Z., Cui Z., Guan P., Li X., Wu W., Ren Y., He Q., Zhou B. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128572. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renz J. F., Kalf G. F. Blood. 1991;78:938–944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale C. M., Zhang L., Lan Q., Li G., Hubbard A. E., Forrest M. S., Vermeulen R., Chen J., Shen M., Rappaport S. M., Yin S., Smith M. T., Rothman N. Genomics. 2009;93:343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bironaite D., Siegel D., Moran J. L., Weksler B. B., Ross D. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2004;149:177–188. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldin M. P., Taganov K. D., Rao D. S., Lili Y., Zhao J. L., Manorama K., Yvette G. F., Mui L., Asli D., Jessica X. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208:1189–1201. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H., Huang X., Lu C., Cairo M. S., Zhou X. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:2831–2841. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.591420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J. L., Rao D. S., Boldin M. P., Taganov K. D., O'Connell R. M., Baltimore D. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:9184–9189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105398108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Li M., Campbell R. A., Burkhardt K., Zhu D., Li S. G., Lee H. J., Wang C., Zeng Z., Gordon M. S., Bonavida B., Berenson J. R. Oncogene. 2006;25:6520–6527. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth R. N., Ruslan M. Science. 2007;317:124–127. [Google Scholar]

- de Visser K. E., Eichten A., Coussens L. M. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:24–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grivennikov S. I., Greten F. R., Karin M. Cell. 2010;140:883–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maratheftis C. I., Evangelos A., Moutsopoulos H. M., Michael V. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007;13:1154–1160. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irene G. Á. G., Yue W., Hui Y., Sherry P., Carlos B. R., George C., Boyano-Adánez M. D. C., Guillermo G. M. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93404–e93404. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.