Abstract

People regulate their eating behavior in many ways. They may respond to overeating by compensating with healthy eating behavior or increased exercise (i.e., a sensible tradeoff), or by continuing to eat poorly (i.e., disinhibition). Conversely, people may respond to a healthy eating event by subsequently eating poorly (i.e., self-licensing) or by continuing to eat healthily (i.e., promotion spillover). We propose that people may also change their behaviors in anticipation of an unhealthy eating event, a phenomenon that we will refer to as pre-compensation. Using a survey of 430 attendees of the Minnesota State Fair over two years, we explored whether, when, and how people compensated before and after this tempting eating event. We found evidence that people use both pre-compensatory and post-compensatory strategies, with a preference for changing their eating (rather than exercise) behavior. There was no evidence that people who pre-compensated were more likely to self-license by indulging in a greater number of foods or calories at the fair than those who did not. Finally, people who pre-compensated were more likely to also post-compensate. These results suggest that changing eating or exercise behavior before exposure to a situation with many tempting foods may be a successful strategy for enjoying oneself without excessively overeating.

Keywords: self-regulation, disinhibition effect, self-licensing, compensation strategies, eating behavior

After indulging in a highly caloric, high-fat meal, many people aim to reduce their food consumption for the rest of the day to offset the negative repercussions of the unhealthy behavior (Knäuper, Rabiau, Cohen, & Patriciu, 2004; Rabiau, Knäuper, & Miquelon, 2006). This compensatory behavior generally occurs after a self-regulatory lapse (e.g., watching what one eats after indulging at Thanksgiving dinner; Tomiyama, Moskovich, Haltom, Ju, & Mann, 2009) or within a single eating episode (e.g., ordering a diet soda to accompany a cheeseburger; Chandon & Wansink, 2007). It is also possible, however, that people compensate by changing their behavior before an event in which they anticipate indulging. This form of compensation, which we will refer to as “pre-compensation,” is the focus of the current study.

People generally believe that they can offset, or compensate for, the negative effects associated with overeating by later restricting their eating or increasing their exercise (Knäuper et al., 2004; Rabiau et al., 2006), and there is evidence that in some circumstances, people may make sensible trade-offs to compensate for their lapses in self-regulation. For example, dieters who were compelled to consume a milkshake for a study compensated for those calories by subsequently eating less throughout the remainder of the day (Tomiyama et al., 2009), and non-dieters have been shown to do the same (Timko, Juarascio, & Chowansky, 2012).

At other times, however, people fail to compensate for unhealthy eating with healthier eating or increased physical activity. In a well-known series of studies (Herman & Mack, 1975), dieters who were required to break their diet by consuming a milkshake subsequently ate more ice cream during an in-lab taste-test than did non-dieters. This disinhibition effect, as it is called (Herman & Polivy, 1984), has been shown to occur when people have no choice but to remain in a room and sample tempting foods, rather than when they are free to choose their own activities and environments (e.g., Tomiyama et al., 2009). In sum, after a self-regulatory lapse, people can either compensate by changing their behavior in healthy ways, or they may continue to act in unhealthy ways.

Although compensation is typically conceptualized in terms of behaviors completed after an unhealthy behavior in order to offset it, it is also possible to conceptualize compensation in terms of the behaviors that people allow themselves to engage in after behaving in a healthy way. Self-licensing refers to when people compensate for their healthy behavior by engaging in a subsequent unhealthy behavior (de Witt Huberts, Evers, & de Ridder, 2012). In one study, subjects were given either a sandwich that they perceived as healthy or a sandwich that they perceived as unhealthy and then were able to select the rest of their meal from a menu (Chandon & Wansink, 2007). The participants who were given the healthy sandwich ordered additional foods that ultimately made their meals less healthy than the meals of participants initially given an unhealthy sandwich. This suggests that a perceived self-regulatory success gave the participants license to indulge for the remainder of the meal. Similarly, in focus groups of regular exercisers, many people reported rewarding themselves with food on days that they exercised (Dohle, Wansink, & Zehnder, 2015). Furthermore, in a study in which physical activity was framed to be thought of as effortful exercise or as a fun scenic walk, people were more likely to increase their consumption of a dessert or snack when it was framed as exercise (Werle, Wansink, & Payne, 2015), again suggesting a self-licensing effect. Finally, in an experimental study of overweight and obese women, the majority (63%) compensated for a moderate-intensity exercise session by subsequently eating more or by being less active compared to after a rest session (Emery, Levine, & Jakicic, 2016).

However, it is also possible that people can respond to a healthy behavior by continuing to act in a healthy way. Although little research to date has examined how a healthy behavior could lead to a second, healthy behavior, in Dolan and Galizzi’s (2015) review of behavioral compensation, when the performance of behavior A encourages the performance of behavior B in the same direction, it is referred to as a promotion spillover. An example of a positive promotion spillover is the finding that for some individuals, more frequent exercise encourages healthier eating behavior (Dohle et al., 2015).

In sum, people can respond to an eating event in multiple ways (see Table 1 for a summary). If the initial eating behavior is unhealthy, they may compensate by increasing healthy eating behavior (Tomiyama et al., 2009) or exercise (Dohle et al., 2015; Fleig, Küper, Lippke, Schwarzer, & Wiedemann, 2015) later in the day—the sensible tradeoff effect. However, for dieters, an unhealthy eating event may lead them to continue to eat poorly (at least for the rest of that meal; Herman & Mack, 1975; Herman & Polivy, 1984)—the disinhibition effect. Conversely, if the initial eating behavior is healthy, or if people have exercised (Dhar & Simonson, 1999; Dohle et al., 2015), they may then allow themselves to indulge in unhealthy foods (Chandon & Wansink, 2007) or to consume more food and/or be less active (Emery et al., 2016)—the self-licensing effect. Finally, the performance of a healthy behavior (e.g., exercise) sometimes promotes additional healthy behavior (e.g., eating) (Dohle et al., 2015)—the promotion spillover effect.

Table 1.

Summary of Relationships Between Sequential Healthy versus Unhealthy Behaviors

| Subsequent Behavior | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unhealthy | Healthy | ||

| Initial Behavior | Unhealthy | Disinhibition | Sensible trade-off |

| Healthy | Self-licensing | Promotion spillover | |

These four effects appear to occur spontaneously in response to engaging in a healthy or unhealthy behavior. The focus of our current work, however, is on the extent to which people plan ahead for upcoming unhealthy behavior by intentionally engaging in healthy behavior, or pre-compensating. We hypothesize that when people anticipate being exposed to a highly tempting eating event, they may pre-compensate by changing their eating or exercise behavior. We explore how common this behavior is, and how it influences subsequent eating behavior. Does compensating in anticipation of an eating event help people keep their consumption within their normal range of calories despite indulging in unhealthy foods at the event (i.e., a sensible trade-off), or does it result in greater overall consumption (i.e., self-licensing) compared to people who do not pre-compensate?

The current study addressed these questions by examining compensation behaviors that occur around a popular eating event: the Minnesota State Fair. The Minnesota State Fair is known for its remarkable assortment of unique and appetizing, yet highly caloric foods (e.g., fried cookie dough, macaroni and cheese on a stick). In fact, for many, the primary draw of the state fair is the food. Therefore, it is a setting in which people may be inclined to far exceed their normal caloric intake, and it is likely that many people go to the fair aware of this possibility, making the Minnesota State Fair an ideal setting to explore how people regulate their eating when surrounded by temptation. Using a survey of fairgoers, we examined the frequency of pre-compensation, and explored when, how, and which people compensated before and after this tempting eating event.

Method

Participants

Participants were attendees of the Minnesota State Fair in two successive years. They were recruited after they entered or as they walked by a building dedicated specifically for research that housed multiple researcher teams studying a variety of topics in the social and health sciences. In Year 1, both data collection sessions were in the afternoon/evening from 3:00pm-9:00pm. In Year 2, two of the data collection sessions were in the afternoon/evening, and the other two sessions were in the morning/early afternoon from 9:00am-3:00pm. In order to participate, people indicated that they were over 18 years of age and that they had already eaten at least one food item at the fair that day.

Participants were 430 attendees (n = 198 in Year 1; n = 232 in Year 2; 91.5% White, 3.3% Asian/Asian-American, 1.0% Hispanic, 0.7% Black/African-American, and 3.5% multi-ethnic/other), between the ages of 18 to 83 years old (M = 42.5, SD = 16.1), 70.2% of whom were women. Participants reported an average body mass index (BMI) of 26.5 kg/m2 ranging from 16 to 55 (SD = 5.8 kg/m2).1 There were no demographic differences across years. In Year 1, all participants were compensated with $5, and in Year 2, participants were entered into a raffle to win one of six $100 gift cards.

Procedure

After providing consent, participants completed a survey about their eating behavior at the fair so far that day, any changes that they had made to their eating and exercise behavior before the fair, and any changes they were planning to make after attending the fair. Participants in the Year 2 sample were also emailed a follow-up survey at 6:00pm the day after their visit to the fair. The follow-up survey asked participants to again report on their eating behavior from the previous day’s visit to the fair and on whether they had made any changes to their eating and exercise behavior since attending the fair. Of the Year 2 participants, 53.9% (125 out of 232) responded to the follow-up survey.

Materials

State fair survey.

Food consumed at the fair.

To measure the types of foods that participants consumed at the fair, we compiled a list of 287 foods that were available at the Minnesota State Fair in Year 1 and added an additional 150 foods that were either new to the fair in Year 2 or that we had previously missed for a total of 437 food items in Year 2. Participants used a search box to find and select the foods that they had eaten so far at the fair that day. If they could not find a food that they had eaten, they were able to enter the name of the food and the vendor, or a description of it. A paper list of all of the foods was also available for participants’ reference. After listing all of the foods that they had eaten, participants were asked to estimate the percentage of each food item that they had consumed so that we could account for unfinished and shared foods in their calorie total.

To estimate the number of calories in each of the foods on our list, we first searched for the food using a list of typical state fair foods and their associated calories. If we could not find the food on that list, we searched for the food item sequentially on CalorieKing, SparkPeople, WebMD, and MyFitnessPal (in that order), such that once a calorie estimate was found, it was recorded. The calories in foods consisting of multiple components that could not otherwise be found were calculated by adding together the calorie estimates for each part of the dish.

Pre-compensation behavior.

Participants were asked whether they had changed any of their usual eating and exercise behavior before attending the fair. If participants indicated that they had changed their usual eating behavior before the fair, they were then asked a series of questions probing how, when, and why they changed their eating behavior. First, they selected from a list of how they might have changed their eating behavior: whether they 1) ate less than usual, 2) ate more than usual, 3) ate more healthy foods than usual, 4) ate fewer unhealthy foods than usual, or 5) other (with the option to fill in a response). Second, they indicated how long before the fair they had changed their usual eating behavior: 1) since that morning, 2) since the day before, 3) for a few days before the fair, or 4) for more than a few days before the fair. Third, in the Year 2 survey, participants indicated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree”; 7 = “strongly agree”) the extent to which they agreed with each of seven reasons for changing their usual eating behavior before the fair: 1) trying to lose weight, 2) trying to maintain weight, 3) wanting to be healthy, 4) wanting to enjoy the food at the fair as much as possible, 5) wanting to compensate for the many calories eaten at the fair, 6) not wanting to be tempted to eat too much at the fair, and 7) not wanting to feel guilty for eating a lot of food at the fair. If participants indicated that they had changed their usual exercise behavior before attending the fair, they were asked a similar series of how, when, why, and to what effect questions. The how-related exercise questions were the only ones to differ substantively from the eating questions. Participants indicated whether they 1) spent more time exercising than usual, 2) increased the intensity of their exercise compared to their normal routine, or 3) other (with the option to fill in a response).

Post-compensation intentions.

Participants were asked whether they were planning to change any of their eating and exercise behavior after attending the fair using modified versions of the questions used for pre-compensation behavior.

Follow-up survey: Post-compensation behavior.

In Year 2 only, participants were also e-mailed a follow-up survey the day after they had completed the survey at the state fair. They were asked whether they had changed any of their eating and exercise behaviors since attending the fair, using modified versions of the pre-compensation questions.

Results

The distributions for number of foods eaten, calories consumed, age, and BMI are all non-normal. Therefore, when testing for difference between groups on these variables, we used Wilcoxon’s rank sum test (with continuity correction when appropriate), instead of t-tests. This test tends to yield more conservative p-values than do t-tests.2

Consumption at the Fair

Participants ate between 1 and 17 different fair foods (M = 2.99, SD = 1.96; see Figure 1). After accounting for the percent of each food consumed (by removing shared and discarded calories), participants ate between 15 and 6072 calories (M = 1040.21, SD = 723.36; see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distributions for calories and number of foods eaten at the fair. The red line depicts the mean, and the red area depicts the kernel density estimate.

Pre-compensation Behaviors

Who, what, when, and how.

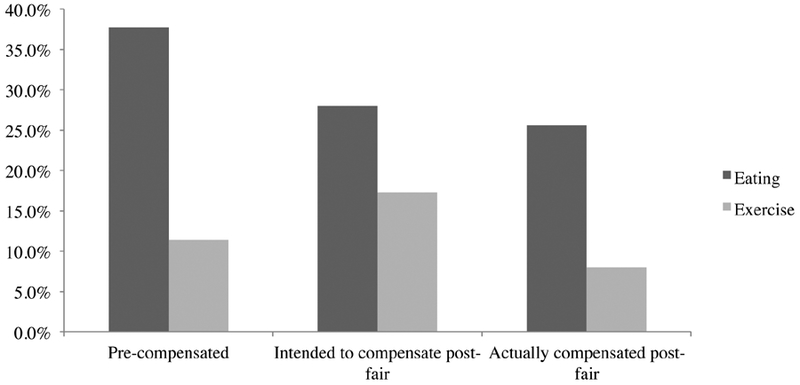

Across survey years, as we hypothesized, participants did engage in pre-compensation. In fact, 37.7% (n = 162) of participants (n = 430) reported making healthy changes to their usual eating behavior before attending the fair (see Figure 2), by eating less food overall (59.0%, n = 95), fewer unhealthy foods (48.1%, n = 77), and/or more healthy foods (32.7% n = 53). The majority (54.0%, n = 75) of respondents who changed their eating behavior before the fair made their changes the same day, whereas 20.9% (n = 29) did so the day before the fair, and 25.1% (n = 35) did so more than a day before the fair.3 A greater proportion of women (40.8%) reported changing their eating behavior before the fair than did men (29.9%; χ2(1, n = 426) = 4.50, p = .034), but there were no other age, ethnic, or BMI differences between those who did and did not pre-compensate by changing their eating (all p’s > .267).

Figure 2.

The percentages of participants who reported changing their exercise or eating behavior before the fair, after the fair, or were planning to do so after the fair.

It was less common to make pre-compensatory changes to one’s exercise behavior. Just 11.4% (n = 49) of participants (n = 430) reported changing their usual exercise behavior before attending the fair (see Figure 2). Of these participants, 62.5% (n = 30) indicated that they exercised for longer, and 47.9% (n = 23) reported increasing the intensity of their exercise. Of those who changed their exercise behavior before the fair, about one third (35.7%, n = 15) indicated that they made their changes earlier that day, 19.0% (n = 8) did so the day before the fair, and 45.3% (n =19) did so more than a day before the fair.4 There were no age, gender, ethnic, or BMI differences between participants who did and did not pre-compensate by changing their exercise (all p’s > .146).

Reasons for pre-compensating.

The reasons that participants rated most highly for pre-compensating by changing their eating were: wanting to enjoy the food at the fair as much as possible (M = 5.67, SD = 1.53), wanting to be healthy (M = 5.58, SD = 1.59), trying to lose weight (M = 4.47, SD= 1.95), and not wanting to feel guilty for eating a lot of food at the fair (M= 4.39, SD = 2.10). The highest rated reasons that participants gave for pre-compensating by changing their exercise were: wanting to be healthy (M = 5.67, SD = 2.28), not wanting to feel guilty for eating a lot of food at the fair (M = 4.83, SD = 2.50), trying to lose weight (M = SD = 2.45), and wanting to compensate for the many calories eaten at the fair (M = 4.22, SD = 2.51).

Consequences of pre-compensation.

Changing eating behavior before the fair did not lead participants to consume more foods or calories at the fair than participants who did not change their eating beforehand (see Table 2), according to a Wilcoxon rank-sum test, (, p = .926 for foods; , p = .547 for calories). Participants who increased their exercise behavior before the fair consumed marginally fewer foods and significantly fewer calories at the fair than the participants who did not (, 95% CI [−1.0, 4.8 × 10−5], p = .083 for foods; , 95% CI [−392.0, −59.0], p = .008 for calories; see Table 2).

Table 2.

The Average Number of Foods and Calories Consumed by Compensation Strategy Used

| Compensation Strategy Used | n | Foods | Calories | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | p-value | Mean (SD) | p-value | |||

| Pre-compensated | ||||||

| Eating | Yes | 162 | 2.98 (1.99) | 0.926 | 1067.5 (762.3) | 0.547 |

| No | 268 | 3.00 (1.94) | 1023.7 (699.7) | |||

| Exercise | Yes | 49 | 2.39 (1.08) | 0.083 | 774.9 (478.0) | 0.008 |

| No | 381 | 3.07 (2.03) | 1074.3 (742.7) | |||

| Intended to compensate post-fair | ||||||

| Eating | Yes | 120 | 2.93 (1.82) | 0.997 | 1049.9 (708.7) | 0.780 |

| No | 309 | 3.00 (2.01) | 1034.1 (730.1) | |||

| Exercise | Yes | 74 | 2.89 (1.87) | 0.728 | 1035.5 (751.6) | 0.824 |

| No | 353 | 3.00 (1.98) | 1038.2 (719.1) | |||

| Actually compensated post-fair | ||||||

| Eating | Yes | 32 | 2.75 (1.72) | 0.202 | 1062.3 (847.0) | 0.250 |

| No | 93 | 3.13 (1.75) | 1143.6 (684.5) | |||

| Exercise | Yes | 10 | 4.10 (1.85) | 0.041 | 1674.3 (1083.7) | 0.091 |

| No | 115 | 2.94 (1.71) | 1074.8 (672.9) | |||

Compensation Intentions & Behaviors After the Fair

Intentions to compensate post-fair.

About 28.0% (n =120) of participants reported that they planned to change their eating in healthy ways after the fair, and 17.3% (n = 74) of participants reported that they planned to increase their usual exercise behavior after the fair (see Figure 2).5 There were no differences in the number of foods or calories consumed at the fair between participants who were planning to change their eating behavior after the fair and participants were not (, p = 0.997 for foods; , p = .780 for calories; see Table 2), or between participants who were planning to change their exercise behavior after the fair and those who were not (, p = 0.728 for foods; , p = 0.824 for calories; see Table 2).

Those who planned to change their eating behavior after the fair (n = 117) had marginally higher BMIs (M = 27.36 kg/m2) than those who did not plan to change (n = 304; M = 26.22 kg/m2, , 95% CI [−.04, 2.06], p = .061). Similarly, those who planned to change their exercise behavior (n = 72) had significantly higher BMIs (M = 28.28 kg/m2,) than those who did not (n = 347; M = 26.14 kg/m2, , 95% CI [.29, 3.11], p = .018). Furthermore, there were differences in plans to post-compensate by ethnicity for eating (p = .031), but not exercise (p > .548): non-White people were more likely to plan to change their eating (44.4%) after the fair than were White people (26.2%; χ2(1, n = 426) = 4.63, p = .031). There were no other differences between these groups by age or gender (all p’s > .175), although the participants who said that they would post-compensate by changing their exercise behavior were marginally younger (M = 39.7, n = 73) than those who did not (M = 43.1, n = 351, , 95% CI [−8.00, 0.00], p = .064).

Actual compensation post-fair.

In the follow-up survey administered the day after the fair (only in Year 2, n = 125), we asked participants about their actual behavior in the 24 hours since leaving the fair. We found that 25.6% (n = 32) of participants reported making healthy changes to their usual eating behavior since attending the fair, and 8.0% (n = 10) of participants reported that they had increased their usual exercise behavior after attending the fair (see Figure 2).6 There were no differences in the number of foods or calories consumed at the fair between participants who changed their eating behavior after the fair and those who did not (, p = .202 for foods; , p = .250 for calories; see Table 2). Participants who changed their exercise behavior after the fair, however, consumed significantly more foods and marginally more calories at the fair than those who did not (, 95% CI [3.0 × 10−5, 3.00], p = .041 for foods; , 95% CI [−110, 1212], p = .091 for calories; see Table 2). There were no differences in age, gender, ethnicity, or BMI between those who made changes to their eating behavior or their exercise behavior after the fair and those who did not (all p’s > .127).

Intention-behavior congruency.

Are the people who made changes after the fair the same people who reported that they were planning to make those changes? Of the participants who planned to compensate by changing their eating behavior after the fair, 52.9% (n = 18) post-compensated by changing their eating behavior after the fair. Of those who planned to compensate by changing their exercise behavior after the fair, 31.3% (n = 5) post-compensated by changing their exercise behavior after the fair.

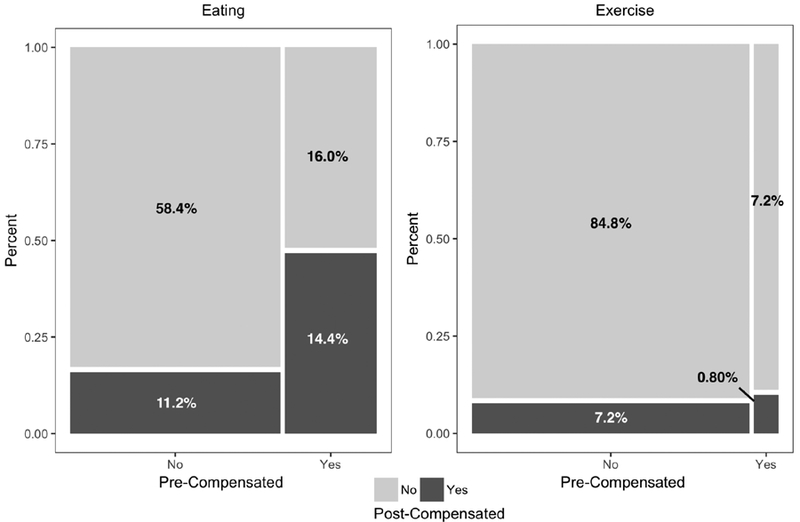

Pre- and post-compensation.

We were able to explore (in Year 2) whether people who pre-compensated also engaged in compensation after the fair (see Figure 3). With regard to eating behavior, 16% of participants (n = 20) only engaged in pre-compensation, 11.2% (n = 14) only engaged in post-compensation, 14.4% (n = 18) engaged in both pre- and post compensation, and 58.4% (n = 73) of participants did not engage in either form of compensation. Participants who pre-compensated by changing their eating were also more likely to post-compensate (47.4%) than were those who did not pre-compensate (16.1%; χ2(1, n = 125) = 11.99, p = .0005, see left panel of Figure 3). With regard to exercise behavior, 7.2% of participants (n = 9) only engaged in pre-compensation, 7.2% (n = 9) only engaged in post-compensation, 0.80% (n = 1) engaged in both pre- and post compensation, and 84.8% of participants (n = 106) did not engage in either form of compensation (see right panel of Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Mosaic plots depicting cross tabulation of pre- and post- compensation for eating and exercise respectively. Total percentages are depicted in tiles. Percentage of people who compensated after the fair (post-compensation) given pre-compensation status is depicted on the y-axis.

Discussion

The primary goal of this study was to explore whether people changed their eating or exercise behaviors before attending an event that offered large quantities of highly caloric, highly tempting, and highly promoted foods. We found that it was common to make pre-compensatory changes to one’s eating (but less common to make these changes to one’s exercise), and that participants said they made these changes so that they could enjoy the fair food without gaining weight and without feeling guilty about it. To our surprise, these pre-compensatory changes were actually more common than intentions to change behavior after the fair, as well as actual changes after the fair. The focus of the literature has been on the traditional forms of compensation after behavioral lapses, and we contend that pre-compensation is a worthwhile behavior for further study.

Pre-compensating in anticipation of an indulgent eating event is a sensible trade-off if people end up consuming the same amount of food (or less) overall as they would have consumed on a more typical day. However, pre-compensation could also backfire if it prompts people to eat more overall than they would have eaten under normal circumstances—as is the case when a person’s small reduction in eating before an event is used to license a larger increase in consumption at the event (de Witt Huberts et al., 2012). There were no differences in consumption between participants who had pre-compensated and those who did not, suggesting that participants did not use their pre-compensation to license excessive over-consumption at the fair. However, because participants did not quantify the extent of their pre-compensation (e.g., how many fewer calories they consumed than usual, or how many more calories were burned from exercise than usual), we could not precisely assess whether their compensation fully made up for what they ate at the fair. People who pre-compensated with exercise actually consumed somewhat fewer foods and calories at the fair than people who did not do so, suggesting that pre-compensation with exercise may have instead resulted in a promotion spillover. That is, the performance of one positive health behavior – exercise – facilitated the performance of another health behavior – healthy eating (Dolan & Galizzi, 2015).

People who do not pre-compensate and change their behavior before a tempting eating event may of course still compensate for any self-regulatory lapses after the event by changing their regular eating or exercise behavior (Timko et al., 2012; Tomiyama et al., 2009). We found that approximately one-third of fairgoers expressed intentions to change their eating behavior after the fair, compared to one-sixth who planned to change their exercise behavior. Consistent with the well-documented gap between intentions and behavior (Webb & Sheeran, 2006), only about half of those who intended to change their behavior after the fair actually did so.

Finally, people who used pre-compensatory strategies were more likely to also post-compensate. This may be due at least in part to dispositional factors. Some people are more likely to engage in healthy behaviors than others, regardless of when those behaviors occur. On the other hand, it may also be the case that pre-compensation sets the stage for later healthy behaviors. For example, if people pre-compensated for the fair by purchasing healthier snacks than usual, it would be easier for them to continue eating healthy after the fair because they would have healthier foods available.

Although this study provides a novel and naturalistic examination of compensation behaviors in anticipation of and in response to an unhealthy eating environment, there are several limitations to consider. First, participants had to self-report the foods they consumed, and they may not have remembered each food accurately, been able to find each food with the search box in our survey, or been willing to report their consumption honestly. Second, we did not ask participants the extent to which they altered their behavior before the fair; therefore, we could not fully assess the extent to which pre-compensating helped offset what they ate at the fair. Third, the sample population was limited to fairgoers who chose to enter the research building at the state fair, suggesting that they may have been more likely to do activities at the fair other than eating, potentially making them an atypical sample of fairgoers. And although we specifically chose the fair setting because the unique nature of the fair provided an opportunity to explore pre-compensation, this setting may not generalize to other occasions in which overeating is likely (e.g., Thanksgiving).

Overall, many fairgoers spontaneously used pre-compensation strategies in anticipation of the tempting eating event and doing so did not appear to license them to overeat at the event. Future studies need to carefully measure the calories saved in the pre-compensatory eating as well as the calories consumed during the tempting event, so that the effectiveness of pre-compensation as a healthy eating strategy can be tested more rigorously. In addition, it will be important to assess whether pre-compensatory strategies are effective when induced in people who may not have spontaneously used them. If so, this may be a promising strategy for people who want to get through a highly tempting situation without excessive overeating.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the University of Minnesota Clinical and Translational Science Institute for the Driven 2 Discover Community Collaborative.

Footnotes

Four people neglected to report age, gender, and ethnicity. Nine people failed to report either weight or height,

The dataset, codebook, and analysis script available at osf.io/2vzyh.

The number of respondents to each question varied. Of the 162 participants who made changes to their eating behavior, 161, 160, and 162 responded to the question about less food, fewer unhealthy foods, and more healthy foods respectively. 129 responded to the question about when they made that change.

The number of respondents to each question varied. Of the 49 participants who made changes to their exercise behavior, 48 responded to questions about duration and intensity of exercise, and 42 indicated the time at which changes were made.

Of the 430 participants, 429 and 427 responded to the eating and exercise intention questions respectively.

All 125 participants responded to both questions about changing their eating and exercise behavior.

References

- Chandon P, & Wansink B (2007). The biasing health halos of fast food restaurant health claims: Lower calorie estimates and higher side-dish consumption intentions. Journal of Consumer Research, 34, 301–314. doi: 10.1086/519499 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Witt Huberts JC, Evers C, & de Ridder DTD (2012). License to sin: Self-licensing as a mechanism underlying hedonic consumption. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42, 490–496. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.861 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar R, & Simonson I (1999). Making complementary choices in consumption episodes: Highlighting versus balancing. Journal of Marketing Research, 36, 29–44. doi: 10.2307/3151913 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dohle S, Wansink B, & Zehnder L (2015). Exercise and food compensation: Exploring diet-related beliefs and behaviors of regular exercisers. Journal of Physical Activity & Health, 12, 322–327. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2013-0383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan P, & Galizzi MM (2015). Like ripples on a pond: Behavioral spillovers and their implications for research and policy. Journal of Economic Psychology, 47, 1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2014.12.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Emery RL, Levine MD, & Jakicic JM (2016). Examining the effect of binge eating and disinhibition on compensatory changes in energy balance following exercise among overweight and obese women. Eating Behaviors, 22, 10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.03.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleig L, Küper C, Lippke S, Schwarzer R, & Wiedemann AU (2015). Cross-behavior associations and multiple health behavior change: A longitudinal study on physical activity and fruit and vegetable intake. Journal of Health Psychology, 20, 525–534. doi: 10.1177/1359105315574951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman CP, & Mack D (1975). Restrained and unrestrained eating. Journal of Personality, 43, 647–660. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1975.tb00727.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman CP, & Polivy J (1984). A boundary model for the regulation of eating In Stunkard AJ & Stellar E (Eds.), Eating and its disorders (pp. 141–156). New York: Raven Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knäuper B, Rabiau M, Cohen O, & Patriciu N (2004). Compensatory health beliefs: Scale development and psychometric properties. Psychology & Health, 19, 607–624. doi: 10.1080/0887044042000196737 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rabiau M, Knäuper B, & Miquelon P (2006). The eternal quest for optimal balance between maximizing pleasure and minimizing harm: The compensatory health beliefs model. British Journal of Health Psychology, 11, 139–153. doi: 10.1348/135910705X52237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timko CA, Juarascio A, & Chowansky A (2012). The effect of a pre-load experiment on subsequent food consumption. Caloric and macronutrient intake in the days following a pre-load manipulation. Appetite, 58, 747–753. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.11.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomiyama AJ, Moskovich A, Haltom KB, Ju T, & Mann T (2009). Consumption after a diet violation: Disinhibition or compensation? Psychological Science, 20, 1275–1281. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02436.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb TL, & Sheeran P (2006). Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 249–268. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werle COC, Wansink B, & Payne CR (2015). Is it fun or exercise? The framing of physical activity biases subsequent snacking. Marketing Letters, 26, 691–702. doi: 10.1007/s11002-014-9301-6Is [DOI] [Google Scholar]