Abstract

The functional impact of most genomic alterations found in cancer, alone or in combination, remains largely unknown. Here we integrate tumor barcoding, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing and ultra-deep barcode sequencing to interrogate pairwise combinations of tumor suppressor alterations in autochthonous mouse models of human lung adenocarcinoma. We map the tumor suppressive effects of 31 common lung adenocarcinoma genotypes and identify a landscape of context dependence and differential effect strengths.

Cancer growth is largely the consequence of multiple, cooperative genomic alterations1–3. Cancer genome sequencing has catalogued many of these alterations; however, the combinatorial effects of these alterations on tumor growth is largely unknown1,4. Most putative drivers are altered in less than 10% of tumors2, suggesting that these alterations may be inert, weakly beneficial, or beneficial only in certain genomic contexts. Inferring genetic interactions through co-occurrence rates alone is practically impossible, as the number of possible combinations scales factorially with candidate gene number. Genetically engineered mouse models can provide insight into gene function in tumors growing in an autochthonous setting; however, practical considerations have prevented broad studies of combinatorial tumor suppressor gene inactivation (Supplementary Fig. 1a)5,6. Hence our understanding of the genetic interactions that drive tumor growth in vivo remains limited.

To address these practical challenges, we recently developed a method to quantitatively measure the effect of many different tumor suppressor gene alterations in parallel using tumor barcoding coupled with high-throughput barcode sequencing (Tuba-seq)7. Tuba-seq combines genetically engineered mouse models of lung adenocarcinoma with CRISPR/Cas9-mediated tumor suppressor inactivation, tumor barcoding and deep sequencing of DNA barcodes. Because Tuba-seq measures the size of every tumor and is compatible with multiplexing tumor genotypes in individual mice, growth effects can be measured with unprecedented precision, sensitivity and throughput7. Here we employ this approach to systematically analyze pairwise combinations of tumor suppressor alterations in vivo. We quantified the growth of oncogenic KrasG12D-driven lung tumors with 31 common tumor suppressor genotypes (Supplementary Fig. 1a). We identified unexpected genetic interactions, found that the effects of most tumor suppressors are context-dependent, and explain several patterns of genetic alterations in human lung adenocarcinoma.

The tumor suppressor TP53 is inactivated in more than half of human lung adenocarcinomas1, 4. To determine the effect of Trp53 (p53) deletion on the growth suppressive effects of ten other putative tumor suppressors, we initiated tumors in KrasLSL-G12D; Rosa26LSL-tdTomato; H11LSL-Cas9 (KT;Cas9) and KT; Trp53flox/flox; Cas9 (KPT;Cas9) mice using a pool of barcoded Lenti-sgRNA/Cre vectors targeting many common tumor suppressor genes and four barcoded Lenti-sgInert/Cre vectors (Lenti-sgTS-Pool/Cre; Fig. 1, Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2, and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2)7. The barcodes in the LentisgRNA/Cre vectors contain two components, which uniquely identify each tumor and its sgRNA, respectively (sgID-BC; Supplementary Fig. 2b)7. Thus, the number of neoplastic cells in each tumor of each genotype can be determined using our Tuba-seq approach: amplification of the sgID-BC region from bulk tumor-bearing lung genomic DNA, deep sequencing of the product, and tallying of each barcode using our analysis pipeline7. Using this approach, tumor sizes were determined 15 weeks after tumor initiation, when the lungs contained widespread hyperplasias, adenomas and some early adenocarcinomas7.

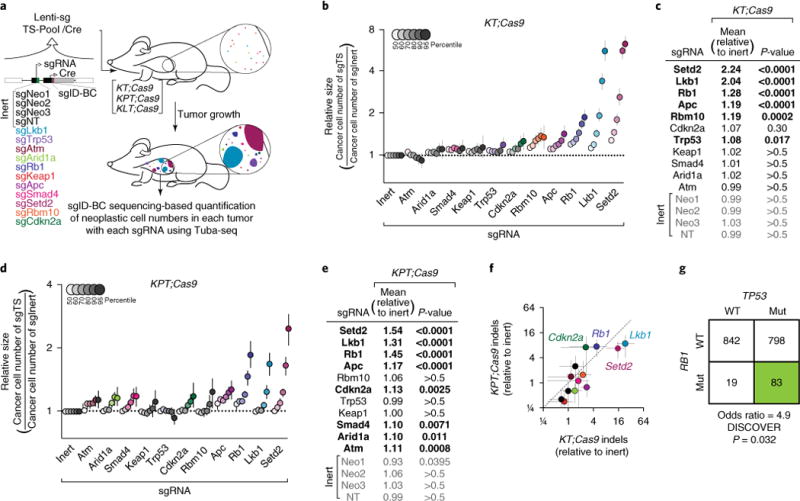

Fig. 1. trp53 deficiency alters the growth effects of tumor suppression in KrasG12D-driven lung tumors in vivo.

a, Tuba-seq approach to study combinatorial tumor suppressor inactivation in vivo. Tumors were initiated with Lenti-sgTS-Pool/Cre (containing four inert sgRNA vectors and eleven vectors targeting known and candidate tumor suppressor genes) in three different genetically engineered mouse backgrounds: KrasLSL-G12D/+; Rosa26LSL-tdTomato; H11LSL-Cas9 (KT;Cas9), KT; Trp53flox/flox; Cas9 (KPT;Cas9) and KT; Lkb1flox/flox; Cas9 (KLT;Cas9). Each sgRNA vector contains a unique sgID and a random barcode, which was used to quantify individual tumor sizes via deep sequencing. b, Analysis of relative tumor sizes in KT;Cas9 mice 15 weeks after tumor initiation. Relative size of tumors at the indicated percentiles is merged data from 10 mice, normalized to the average size of sgInert tumors. Error bars throughout this study denote 95% confidence intervals determined by bootstrap sampling. Percentiles that are significantly different from sgInert are in color. c, Estimates of mean tumor size, assuming a log-normal tumor size distribution, identified sgRNAs that significantly increased growth in KT;Cas9 mice. Bonferroni-corrected, bootstrapped P-values are shown. sgRNAs with P < 0.05 are bold. d,e, Same as b,c, except for merged data from 12 KPT;Cas9 mice. f, Abundance of indels at targeted loci relative to median of genome-targeting inert sgRNAs Neo1–Neo3. Coloring according to a. g, Functional mutations in TP53 and RB1 in human lung adenocarcinomas from TCGA and GENIE datasets (see URLs; N = 1,792). RB1 and TP53 alterations co-occur, as predicted from Tuba-seq fitness measurements. WT, wild type; Mut, mutated.

Tuba-seq analysis of KT;Cas9 and KPT;Cas9 mice uncovered an altered spectrum of tumor suppressive effects for many of the genes in our survey (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 3). Tumor sizes were summarized by two previously vetted measures: log-normal (LN) mean and the size of the 95th percentile tumor (Fig. 1c,d and Methods)7. In Trp53-deficient tumors, inactivation of Rb1, Setd2, Lkb1 (Stk11), Cdkn2a or Apc still provided a growth advantage while Smad4, Arid1a and Atm emerged as tumor suppressors only in the absence of Trp53 (Fig. 1b–e and Supplementary Fig. 3). The emergence of additional tumor suppressors in this background suggests that Trp53 deficiency potentiates subsequent tumor evolution8. By enabling more mutations to be adaptive, Trp53 loss may decrease the predictability of tumor evolution9 and facilitate sub-sequent evolution, including the emergence of treatment resistance and metastatic disease10,11.

Coincident deletion of Trp53 not only enabled more alterations to be adaptive, but also significantly changed the magnitude of effect of tumor suppressor loss. In KT;Cas9 mice, Rb1 deficiency increased tumor size less than Lkb1 or Setd2 deficiency (Fig. 1b–e and Supplementary Fig. 4a; P < 0.0001 bootstrap test unless other-wise specified; Methods). In contrast, in the context of Trp53 deficiency, Rb1 deficiency conferred a growth advantage comparable to that of Lkb1 or Setd2 deficiency (P = 0.14 and 0.5, respectively), consistent with a strong complementary interaction between the Trp53 and Rb1 tumor suppressor pathways (Fig. 1d,e)12. Quantification of Cas9-generated indels at each targeted locus in bulk KPT;Cas9 lung DNA identified comparably high percentages of Lkb1, Setd2 and Rb1 alleles with indels (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Fig. 5). Finally, we confirmed the effect of coincident inactivation of Trp53 and Rb1 on lung cancer growth using conventional Cre/loxP-based mouse models (Supplementary Fig. 4b–d).

The quantitatively different growth benefits of Rb1 inactivation in Trp53-proficient versus Trp53-deficient tumors presented the opportunity to investigate whether changes in the fitness strength of a driver alter the frequency of its alterations in human lung adenocarcinomas. Co-occurrence of RB1 alterations (single nucleotide variants and copy number variants) and TP53 alterations were indeed enriched in human lung adenocarcinoma (P = 0.03; Fig. 1h and Supplementary Fig. 4e,f)1,4. Notably, despite a ~5-fold enrichment in the co-occurrence of these two alterations, this interaction would be statistically insignificant in a naive survey of all potential pairwise driver interactions after correcting for multiple-hypothesis testing, thus illustrating the need to study genetic interactions beyond co-occurrence patterns (P = 0.32 after Bonferroni correction for 10 pairwise interactions)13.

Next we investigated the effects of combinatorial loss of Lkb1 and other putative tumor suppressors by initiating tumors with Lenti-sgTS-Pool/Cre in KT; Lkb1flox/flox; Cas9 (KLT;Cas9) mice (Fig. 2a,b and Supplementary Fig. 3g–i). We investigated Lkb1 because it is frequently inactivated in human lung adenocarcinoma1,4 and because Lkb1 loss dramatically increases lung tumor growth in autochthonous models7,14 (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Notably, both the number of adaptive tumor suppressor losses and the median growth benefit was attenuated in the already fast-growing Lkb1-deficient tumors (irrespective of changes in statistical power between mouse back-grounds; P < 0.05, Methods). This once again demonstrates that a single alteration can dramatically change the fitness landscape of tumors. The general attenuation of fitness benefits as additional growth-promoting alterations are acquired, termed diminishing returns epistasis, is common in evolution15,16 and suggests that tumors may eventually reach a fitness plateau.

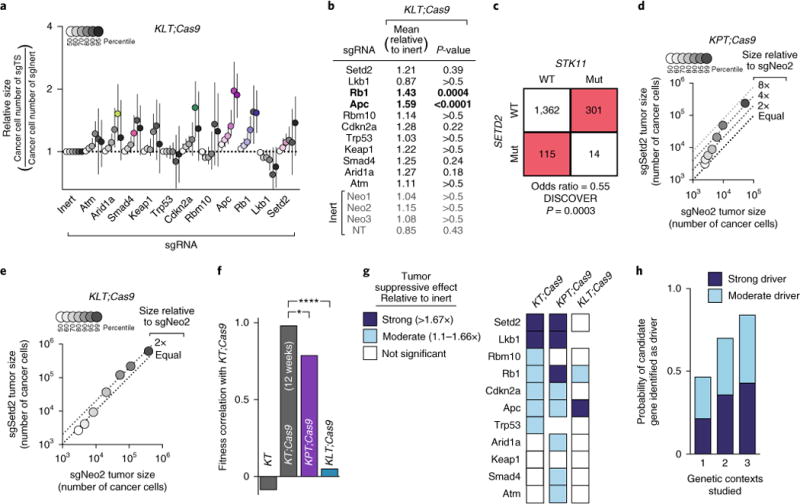

Fig. 2. Attenuated effects of tumor suppressor inactivation in Lkb1-deficient tumors further highlights a rugged fitness landscape.

a, Tumor sizes at indicated percentiles for each sgRNA relative to the average of sgInert-containing tumors at the same percentiles. Merged data from 13 KT; Lkb1flox/flox; Cas9 (KLT;Cas9) mice 15 weeks after tumor initiation with Lenti-sgTS-Pool/Cre. Percentiles significantly different from sgInert are in color. Error bars denote 95% confidence intervals determined by bootstrap sampling. b, Estimates of mean tumor size, assuming a log-normal tumor size distribution, identified sgRNAs that significantly increase growth in KLT;Cas9 mice. Bonferroni-corrected, bootstrapped P-values are shown. P < 0.05 indicated by bold. c, Mutual exclusivity of STK11 (LKB1) and SETD2 mutations in human lung adenocarcinomas from TCGA and GENIE datasets (N = 1,792). WT, wild type; Mut, mutated. d, Tumor sizes in KPT;Cas9 mice with Lenti-sgSetd2/Cre-initiated tumors (N = 7) versus KPT;Cas9 mice with Lenti-sgNeo2/Cre-initiated tumors (N = 3). LN mean size is 2.4-fold greater in Lenti-sgSetd2/Cre-initiated tumors than Lenti-sgNeo2/Cre-initiated tumors and the 95th percentile of tumor size is 4.6-fold greater. e, Tumor sizes in KLT;Cas9 mice with Lenti-sgSetd2/Cre-initiated tumors (N = 7) versus KLT;Cas9 mice with Lenti-sgNeo2/Cre-initiated tumors (N = 5). Relative LN mean and relative 95th percentile are both significantly less than in Fig. 2d (P = 0.04 and P < 0.0001, respectively). f, Pearson correlations of fitness effect of tumor suppressors (determined by LN mean) across genetic backgrounds. sgTrp53 and sgLkb1 growth rates are excluded in KPT;Cas9 and KLT;Cas9 mice, respectively. *P = 0.04, ****P < 0.0001. g, Differential effect of each tumor suppressor gene with coincident Trp53 or Lkb1 deficiency. 95th percentiles that significantly deviate from sgInert tumors are in blue. h, Likelihood of identifying candidate tumor suppressors as drivers (as defined in g) versus the number of contexts studied. All possible genetic contexts were averaged.

Apc and Rb1 inactivation were the only alterations that pro-vided a significant growth advantage to Lkb1-deficient tumors (Fig. 2a,b). The ability of Rb1 deficiency to increase tumor size, even with coincident Lkb1 deficiency, emphasizes the integral role of Rb1 in cell cycle regulation12,17 and fundamentally different mechanism of action from Lkb118. Apc loss is also a key driver of lung cancer growth7,19, and Apc was tumor suppressive in all three backgrounds studied.

Surprisingly, the effect of Setd2 deficiency on the growth of Lkb1-deficient tumors was modest and not statistically significant (Fig. 2a,b). This redundancy is striking because both Lkb1 and Setd2 inactivation strongly promote growth in KT;Cas9 and KPT;Cas9 mice and because there is no evidence that these genes function in the same pathway7,20. We tested and confirmed the context dependence of Setd2 inactivation by initiating tumors with Lenti-sgNeo2/Cre and Lenti-sgSetd2/Cre in KPT, KPT;Cas9 and KLT;Cas9 mice. Setd2 inactivation enhanced Lkb1-proficient lung tumor growth while conferring little, if any, growth advantage on Lkb1-deficient tumors (Fig. 2d,e and Supplementary Fig. 6). This observation is also well supported by the mutual exclusivity of LKB1 and SETD2 alterations in human lung adenocarcinoma (P < 0.001, Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 6).

Most genes in our study exhibited context-dependent growth effects, driving tumor growth only in the presence or absence of Trp53 or Lkb1 (Fig. 2f,g). Even the tumor suppressor alterations that conferred advantage in all three contexts (Rb1 and Apc) still exhibited context-dependent magnitudes of tumor suppression. Such widespread context dependency is overlooked by global surveys of drivers, where driver interactions are either ignored1,2 or presumed to be sufficiently rare and/or weak to justify considering only marginal correlations3,13. Nonetheless, our fitness measurements generally agree with mutation co-occurrence patterns in human lung cancer, despite the limited statistical resolution of these data (Spearman R = 0.50, P = 0.03, Supplementary Fig. 7)1,4. Furthermore, lung cancers do not appear to be unique in their degree of context dependency (Supplementary Fig. 7c), suggesting that direct measurement of context dependency in other cancer types is warranted.

This rugged landscape of tumor evolution has several implications. First, to understand gene function, it is necessary to investigate putative drivers in multiple genetic contexts, as most genes in our survey (8 of 11) were adaptive in only some contexts (Fig. 2h). Second, broader fitness profiling is needed. Power analyses suggest that ~500 moderate-strength interactions could be surveyed using Tuba-seq in a 100-mouse cohort (Supplementary Fig. 8). Larger genomic screens could survey more putative drivers, interactions with other oncogenic events, or triplets of tumor suppressor alterations. Lastly, this extensive context dependency suggests that most driver alterations sweep to fixation infrequently because they are beneficial only in specific genetic contexts.

Our study of the fitness effects of combinatorial tumor suppressor losses in vivo has identified unexpected genetic interactions that were validated by traditional methodologies, as well as by human lung adenocarcinoma genomics data. Our barcoded and multiplexed in vivo genome-editing approach could be easily employed to interrogate these genetic interactions’ impacts on therapeutic response, cell signaling or metastatic progression.

Methods

Methods, including statements of data availability and any associated accession codes and references, are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-018-0083-2.

Mice and tumor initiation

KrasLSL-G12D (K), Lkb1flox (L), Trp53flox (P), R26LSL-Tomato (T), H11LSL-Cas9 (Cas9) and Rb1flox mice have been described21–26. Lung tumors were initiated by intratracheal transduction of mice as previously described27 using lentiviral-Cre vectors at indicated titers. Tumor burden was assessed by fluorescence microscopy and histology where indicated. All experiments were performed in accordance with Stanford University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

Lentiviral titers and time of analysis

Lentiviral titers administered to KT;Cas9, KPT;Cas9 and KLT;Cas9 mice were 22 × 103, 9 × 103 and 4.5 × 103 infectious particles per mouse, respectively. These titers were chosen to approximately balance total tumor burden across the mice at the time of analysis at 15 weeks after tumor initiation (i.e. backgrounds with faster-growing tumors on average received lower titers). Anticipated growth rates were determined previously7. 15 weeks was chosen because tumors grown for 15 weeks in KT;Cas9 mice exhibited easily resolved differences in tumor size (by both Tuba-seq and histological analysis)7.

Generation of the barcoded Lenti-sgTS-Pool/Cre vector pool

To enable quantification of the number of cancer cells in individual tumors in parallel using high-throughput sequencing, we diversified lentiviral-sgRNA/Cre vectors with a short barcode sequence that contains a sequence unique to each sgRNA (sgID) and a sequence unique to each tumor (BC). Cancer cells in individual tumors contain a lentiviral vector that stably integrated into the genome of the initial transduced lung epithelial cell7. We generated tumors using a pool of 15 barcoded Lenti-U6-sgRNA/PGK-Cre vectors in three different genetic backgrounds by initiating tumors in three different genotypes of mice: KT; H11LSL-Cas9/LSL-Cas9 (KT;Cas9), KPT; H11LSL-Cas9/LSL-Cas9 (KPT;Cas9) and KT; Lkb1flox/flox; H11LSL-Cas9/LSL-Cas9 (KLT;Cas9). The design and barcoding of these lentiviral sgRNA/Cre vectors was previously described7. We pooled barcoded Lenti-sgRNA-sgID-BC/Cre vectors (sgLkb1, sgTrp53, sgApc, sgAtm, sgArid1a, sgCdkn2a, sgKeap1, sgNeo1, sgNeo2, sgNeo3, sgNT1, sgRb1, sgRbm10, sgSetd2 and sgSmad4) to generate Lenti-sgTS-Pool/Cre, as previously described7. A detailed protocol for barcoding lentiviral vectors can be found on Protocol Exchange28.

Production, purification and titering of lentivirus

Lentiviral vectors were produced using polyethylenimine-based transfection of 293 T cells with the lentiviral vectors and delta8.2 and VSV-G packaging plasmids. Lenti-sgTS-Pool/Cre, Lenti-sgSetd2/Cre and Lenti-sgNeo2/Cre were generated for tumor initiation as described previously7. Concentrated lentiviral particles were titered by transducing LSL-YFP cells (a gift from A. Sweet-Cordero, UCSF), determining the percent YFP-positive cells by flow cytometry, and comparing the titer to a lentiviral preparation of known titer.

Generation of benchmark cell lines

Three barcoded Lenti-Cre vectors with the sgID TTCTGCCT and unique BC barcodes were used to generate benchmark cell lines that were added to each bulk lung sample at a known cell number to enable calculation of the cancer cell number within each tumor, as previously described7.

Isolation of genomic DNA from mouse lungs and preparation of sgID-BC libraries

Genomic DNA was isolated from bulk tumor-bearing lung tissue from each of the mice, and Illumina sequencing libraries were prepared as previously described7. Detailed protocols can be found on Protocol Exchange29.

Identifying distinct sgRNAs and tumors via ultra-deep sequencing

A pair of unique DNA barcodes distinctly identify each tumor. These barcodes were detected via next-generation sequencing on Illumina HiSeq (2500 or 4000) platforms. Reads were filtered for quality and congruence with the expected lentiviral sequences flanking the barcodes, trimmed, and sorted into tallies of unique sequences. These unique barcode sequences were then annotated as tumors using the Tuba-seq barcode clustering algorithm described previously7 and publicly released (see URLs). GC-content amplification bias was then subtracted using a fourth-order polynomial fit to the residual relationship between barcode GC-content and tumor size (LN mean size of all barcodes with a particular GC content after the LN mean effect of each sgRNA in each mouse has been subtracted), as recommended previously7. Lastly, the absolute number of neoplastic cells in each tumor was determined by multiplying the number of barcode reads for each tumor by the cell number of the three benchmark controls (500,000 cells, added to each mouse lung before lysis and DNA isolation) divided by their mean barcode tallies, as described previously7.

Statistical summary of tumor size distributions

Tumor size distributions across mice were cut off at 500 cells, the current resolution limit of Tuba-seq. Tumor sizes were normalized by dividing absolute tumor size by the median sgInert tumor size within a given mouse. This controls for the observed variability in median tumor size between replicate mice. Relative tumor sizes were then aggregated across replicate mice to produce a final size distribution for each genotype. All of these steps, and their statistical rationale, were described previously7.

We use two previously vetted7 metrics to represent the distribution of tumor sizes observed in our various experiments: the 95th percentile of the tumor size distribution and the maximum-likelihood estimate of the mean based on a log-normal distribution (LN mean). Two summary statistics were used because Tuba-seq has identified reproducible differences in the shape of the tumor size distribution generated by different tumor suppressor alterations7, therefore making it impossible to completely summarize growth effects with any single measure. Briefly, the 95th percentile represents the best non-parametric summary of tumor growth, avoids issues intrinsic to the inefficiency of Cas9-mediated generation of frameshift mutations and focuses on growth differences between larger tumors, which are likely more relevant to cancer morbidity than small hyperplasias. The LN mean estimate represents the best overall parametric summary of tumor growth based on maximum likelihood quality of fit of various common parametric distributions. All Tuba-seq findings discussed in the main text were confirmed by both the LN mean summary measure and the 95th percentile summary measure, thus reducing the likelihood that these findings represent spurious growth effects.

Change in sgID representation was also used to assess tumor suppressive effects in a manner independent of the Tuba-seq pipeline (Supplementary Fig. 3). sgID representation was determined by tallying the reads associated with each sgID within each mouse (1 nucleotide mismatch was permitted). Relative sgID representation was determined by dividing each tally by the average tally of inert sgIDs within each mouse. Change in representation of each sgID was determined by dividing relative sgID representation in KT;Cas9, KPT;Cas9 and KLT;Cas9 mice by the mean relative sgID representation of tumors in the KT mice (which lack Cas9 and therefore do not introduce null alleles at the sgRNA target sites) transduced with the same Lenti-sgTS-Pool/Cre pool and grown for 12 weeks. Tumor growth distributions in KT mice were generated previously7. P-values and confidence intervals were determined by bootstrapping individual mouse sgID tallies for 2 million permutations (described below).

Our previous analysis of variance on the various sources of noise and experimental error in Tuba-seq found that change in sgID representation has less statistical resolution compared to measures that incorporate the sizes of all individual tumors and consider the entire tumor size distribution (also evident in Supplementary Fig. 3). This analysis of variance also found that it was unnecessary to normalize tumor size distributions by their representation in the Lenti-sgTS-Pool/Cre pool, as Tuba-seq accurately measures tumor number (i.e., the representation of each sgTS within the pool need not be explicitly accounted for when performing Tuba-seq analysis because Tuba-seq automatically identifies greater pool representation by virtue of there being more tumors). Hence, only bulk measurements that do not implicitly infer titers—i.e., relative sgID representation (not percentiles nor LN mean)—were normalized by representation in the lentiviral pool, as determined by tumor growth data in KT mice.

Statistical tests

Unless otherwise specified, all P-values and 95% confidence internals were determined using the bootstrap resampling method. Estimates of the sampling distribution of every reported statistic were determined by redrawing from all observed relative tumor sizes using the bootstrap method (sampling with replacement of equal size to the observed sample). 10,000 bootstrap samples were drawn for any P-value reported to a 0.05 false discovery rate (FDR), 200,000 bootstrap samples were drawn for any percentile statistic reported, and 2,000,000 bootstrap samples were drawn for all LN mean estimates. P-values below a 0.0001 FDR (after correcting for multiple-hypothesis testing using the Bonferroni method) were reported as < 0.0001, as anything smaller exceeds the statistical power of our bootstrapping approach.

Power analyses

We used power analyses for two purposes: first, to determine whether the changes we observed in growth effects of putative tumor suppressors across the KT;Cas9, KPT;Cas9 and KLT;Cas9 mouse backgrounds were simply the result of changes in statistical power between these three backgrounds, and second, to calculate the number of mice need to enable the analyze of different numbers of experimental sgRNAs with sufficient statistical resolution.

Because KT;Cas9, KPT;Cas9 and KLT;Cas9 mice received different titers of lentiviral vectors (to balance total tumor burden), we investigated the possibility that the differences in the numbers of tumors analyzed between these mice altered the statistical power sufficiently to cause the changes observed in tumor suppressor effect in each background. KT;Cas9 mice were initiated with the highest titer and had the most tumors, while KLT;Cas9 mice were initiated with the lowest titer and had the fewest tumors. Thus, we drew random samples of tumors from KT;Cas9 mice of a quantity equal to the number of tumors in KLT;Cas9 mice and compared the number of statistically significant interactions observed in these two, now equally sized, sets of tumors. This comparison was made via nested resampling: 2,000 random samples (with replacement) of tumors from KT;Cas9 mice were drawn, and the statistically significant functional tumor suppressors (0.05 FDR increase in LN mean relative to sgInert values) were determined using a second, bootstrap resampling, of these random samples. sgLkb1 was excluded, as this guide cannot be adaptive in the KLT;Cas9 background. Finally, a sampling distribution of the number of functional tumor suppressors was generated and compared to the number of functional tumor suppressors in the KLT;Cas9 background (two, sgRb1 and sgApc). Despite this reduction in the statistical resolution of growth effects in KT;Cas9 mice, more functional tumor suppressors were identified in the KT;Cas9 background than the KLT;Cas9 background (P < 0.05, N = 44,743 tumors in both the KLT;Cas9 and downsampled KT;Cas9 mice cohorts, two-sided test).

To project the effects of using larger mouse cohorts and larger Lenti-sgTS/Cre pools on the likelihood of identifying (i) functional tumor suppressors and (ii) driver interactions, we performed an additional power analysis, wherein tumors were presumed to abide by LN size distributions with parameters identical to the maximum likelihood estimates (MLEs) of observed size distributions.

For the statistical significance of tumor suppression, we compared MLEs of both the log-transformed mean and s.d. of sgLkb1 (strong driver), sgRb1 (moderate driver) and sgCdkn2a (weak driver) to the MLEs of all sgInert tumors (null hypothesis). Because a LN distribution is normal after a log transformation, the statistical significance of hypothetical experiments were determined using a two-sided, unequal-variance Student’s t-test based on these log-transformed MLEs of the mean and s.d. of the representative tumor size distributions. The number of degrees of freedom in these tests were determined by projecting the number of tumors that would arise in an experiment assuming that mice harbored the same number of tumors as were present in our KT;Cas9 mice with the same fraction of tumors initiated with Lenti-sgInert/Cre vectors. Lastly, raw P-values were transformed into estimates of the family-wise error rate (FWER) using the Bonferroni correction.

For the statistical significance of driver interactions, we compared the MLEs of sgSetd2 (normalized to median sgInert) in KLT;Cas9 mice relative to the normalized sgSetd2 size distribution in KT;Cas9 mice (strong interaction), normalized sgRb1 size distribution in KPT;Cas9 versus KT;Cas9 mice (moderate interaction) and normalized sgRbm10 size distribution in KT;Cas9 versus KPT;Cas9 mice (very weak interaction). The number of tumors and FWER were determined as described in the above paragraph. Because the LN distribution is scale invariant, a Student’s t-test of log-transformed statistics remains equally effective after normalizing sizes relative to median sgInert, provided that the degrees of freedom are reduced accordingly.

This approach was used to generate Supplementary Fig. 8. This power analysis concludes that much larger screens are possible (> 500 putative tumor suppressors or interaction pairs) and that it is useful to study tumor suppressor effects in a variety of genetic backgrounds even when this comes at the expense of reduced sample size within each background.

Analysis of indels at target sites

To confirm CRISPR/Cas9-induced indel formation in vivo, the targeted region of each gene of interest was PCR-amplified from genomic DNA extracted from bulk lung samples using GoTaq Green polymerase (Promega M7123) and primer pairs that yield short amplicons amenable to paired-end sequencing as previously described7. For each of the 14 targeted regions, alignments to octamer ‘anchor’ sequences ~25 bp on either side of the targeted region were conducted using bowtie2. Reads were required to contain both anchors to be linked to a given region. The length of each fragment between the two anchors was then determined and deviations from the expected length were then defined as indel-containing reads. The percentage of reads with indels at each target site in each tumor suppressor was normalized to the median percentage of indels observed in each of the three sgNeo target sites.

Quantification of tumor area and barcode sequencing of tumors induced with Lenti-sgSetd2/Cre and Lenti-sgNeo/Cre

To confirm the observed redundancy of loss of Setd2 with loss of Lkb1, we analyzed tumor growth with and without Setd2 loss in the KPT, KPT;Cas9 and KLT;Cas9 mice using de-multiplexed vectors, a second sgRNA targeting Setd2, and traditional tumor size quantification. These changes are intended to test whether technical details about the vectors, sgRNA design, or quantification method would alter our conclusions about the presence of this genetic interaction. Lenti-sgSetd2/Cre and Lenti-sgNeo/Cre vectors were administered to KPT, KPT;Cas9 and KLT;Cas9 mice. Lenti-sgSetd2/Cre and Lenti-sgNeo/Cre at 2 × 104 infectious units per mouse were used to initiate tumors in KPT and KPT;Cas9 mice. Lenti-sgSetd2/Cre and Lenti-sgNeo/Cre at 1 × 104 infectious units per mouse were used to initiate tumors in KLT;Cas9 mice. Mice were analyzed after 9 weeks of tumor growth.

Four tumor-bearing lobes from each lung were fixed in 4% formalin and paraffin-embedded. Hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed using standard methods. Percent tumor area (tumor area divided by total lung area) was determined using ImageJ. The distribution of the number of cancer cells in the tumors in the remaining lung lobe from these mice was determined using Tuba-seq7.

Confirmation of Rb1-mediated tumor suppression in Trp53-deficient background

To test the quantitative increase in fitness of Rb1 loss in the Trp53-deficient background that we observed using our multiplexed Tuba-seq protocol, we investigated the growth effects of Rb1 loss in Trp53-deficient and Trp53-proficient backgrounds using conventional Cre/loxP mouse models. KrasLSL-G12D/+ (K) and KrasLSL-G12D/+; Rb1flox/flox (K;Rbflox/flox) mice were transduced with 3 × 107 Adeno-CMV-Cre virus (University of Iowa Viral Vector Core). KrasLSL-G12D/+; Trp53flox/flox (KP) and KrasLSL-G12D/+; Trp53flox/flox; Rb1flox/flox (KP;Rbflox/flox) mice were transduced with 5 × 106 Adeno-CMV-Cre. All mice were analyzed 12 weeks after tumor initiation. Tumor areas was determined by histology as described above.

Micro-computed tomographic and histologic analyses

Tumors were visualized by micro-computed tomography (μ CT) as described30. Briefly, lungs were collected, perfused with PBS to remove blood, and inflated with 4% formalin. The lungs were then sequentially kept in formalin and 20% IsoVue370/PBS over 2 separate days. Before imaging, each lung was perfused with soybean oil. Lungs were scanned with an eXplore Locus microCT scanner (GE Healthcare) at 22 μ m resolution. Images were visualized and reconstructed using GE eXplore software.

Fitness correlations with KT;Cas9 background

Fitness vectors for each mouse background (KT;Cas9, KPT;Cas9, KLT;Cas9) were determined using the relative LN mean estimates of growth for every tumor suppressor in our screen (excluding all inert sgRNAs). Pearson correlations with previously published KT;Cas9 (12 week) mice and KT mice were also determined7. Fitness vectors based on the relative 95th percentile tumor sizes exhibited a highly similar correlation matrix. The sgTrp53 and sgLkb1 LN mean estimates were excluded when correlating to KPT;Cas9 and KLT;Cas9 mice, respectively, as these guide RNAs do not induce genetic changes in the respective backgrounds. 200,000 bootstrap samplings of relative tumor sizes (as described in “Statistical tests”) were drawn to produce P-values describing the likelihood that two correlation coefficients are identical. As positive and negative controls, the fitness vectors for KT;Cas9 (12 weeks) mice and KT (12 weeks) mice were determined from previous data7.

Analysis of co-occurrence and mutual exclusivity from human data

TCGA lung adenocarcinoma somatic mutation and copy number were downloaded from the NCI Genomic Data Commons website (see URLs) and AACR GENIE (Genomics Evidence Neoplasia Information Exchange) via Synapse (see URLs) from the subset “Lung Adenocarcinoma”. Silent mutations were removed from both datasets. Deletions from TCGA datasets were called as described in Curtis et al.31. The DISCOVER statistical test was used to determine co-occurrence and mutual exclusivity13. A total of 230 samples (TCGA, 2014)1 and 1,563 samples (GENIE, 2017)4 were studied.

URLs

Code, https://github.com/petrov-lab/tuba-seq; Addgene, https://www.addgene.org/; Genomic Data Commons, http://gdc.cancer.gov; Synapse, http://www.synapse.org/#!Synapse:syn7222066.

Life Sciences Reporting Summary

Further information on experimental design is available in the Life Sciences Reporting Summary.

Data availability

All major components of this study have been made publicly available. Plasmids have been described previously7 and are available on Addgene (see URLs). H11LSL-Cas9 mice are available from Jackson Laboratories (Jax 027650, 028239, 026816, 027632) and combination of strains can be requested directly from our laboratory. Tuba-seq protocols, including lentiviral vector barcoding28, genomic DNA extraction and library preparation29, are available on Protocol Exchange.

The Tuba-seq pipeline has been publicly released (see URLs). The code used for this experiment has been archived, but is also under active open-source development for improved general use. Raw sequencing files and processed tumor calls from every mouse are available on GEO (GSE107716). Statistical analysis code used downstream of tumor calls was described previously7 and outlined above. We encourage direct contact with the authors who designed protocols and software, as best practices will evolve over time.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Chu and R. Ma for technical support, A. Orantes for administrative support, members of the Petrov and Winslow laboratories for comments, and T. Jacks for initial support. Z.N.R. and I.P.W. were supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program (GRFP). Z.N.R. was additionally supported by a Stanford Graduate Fellowship. I.P.W. was additionally supported by NIH F31CA210627 and NIH T32HG000044. C.D.M. was supported by NIH E25CA180993. J.J.B. was supported by NIH F32CA189659. J.A.S. was supported by Susan G. Komen for the Cure PDF16377256. D.P. is the Michelle and Kevin Douglas Professor of Biology. This work was supported by NIH R01CA175336 (to M.M.W.), R01CA207133 (to D.P. and M.M.W.), and in part by the Stanford Cancer Institute support grant (NIH P30CA124435). The authors would like to acknowledge the American Association for Cancer Research and its financial and material support in the development of the AACR Project GENIE registry, as well as members of the consortium for their commitment to data sharing. Interpretations are the responsibility of study authors.

Footnotes

Author contributions

Z.N.R. generated barcoded vectors, produced lentivirus and performed mouse analysis, indel analysis and analysis of single sgRNA tumor sizes. C.D.M. performed data analysis, including processing sequencing data, and all statistical analyses. I.P.W. generated the mouse models, selected tumor suppressors to investigate, designed sgRNAs, generated Lenti-sgRNA/Cre vectors, tested sgRNA cutting efficiency, produced lentivirus and performed indel analysis. J.A.S. and C.C. performed analysis of human cancer datasets. S.Y. and J.J.B. contributed to experiments and analyses. D.A.P. and M.M.W. oversaw the project. Z.N.R., C.D.M., D.A.P. and M.M.W. wrote the manuscript with comments from all authors.

Competing interests

Stanford University has filed a patent (US Provisional Application 62/481,067) based on this work in which Z.N.R., I.P.W., C.M., D.A.P., and M.M.W. are coinventors.

Supplementary information is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-018-0083-2.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Nature. 2014;511:543–550. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawrence MS, et al. Nature. 2014;505:495–501. doi: 10.1038/nature12912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mina M, et al. Cancer Cell. 2017;32:155–168.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.AACR Project GENIE Consortium. Cancer Discov. 2017;7:818–831. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kersten K, de Visser KE, van Miltenburg MH, Jonkers J. EMBO Mol Med. 2017;9:137–153. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201606857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frese KK, Tuveson DA. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:645–658. doi: 10.1038/nrc2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rogers ZN, et al. Nat Methods. 2017;14:737–742. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lenski RE, et al. Proc Biol Sci. 2015;282:20152292. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.2292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Visser JAGM, Krug J. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:480–490. doi: 10.1038/nrg3744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siegal ML, Leu J. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2014;45:496–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-120213-091705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keshelava N, et al. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6185–6193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sherr CJ, McCormick F. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:103–112. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canisius S, Martens JWM, Wessels LFA. Genome Biol. 2016;17:261. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1114-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ji H, et al. Nature. 2007;448:807–810. doi: 10.1038/nature06030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chou H-H, Chiu H-C, Delaney NF, Segrè D, Marx CJ. Science. 2011;332:1190–1192. doi: 10.1126/science.1203799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wünsche A, et al. Nat Ecol Evol. 2017;1:61. doi: 10.1038/s41559-016-0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burkhart DL, Sage J. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:671–682. doi: 10.1038/nrc2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hardie DG, Alessi DR. BMC Biol. 2013;11:36–47. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-11-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sánchez-Rivera FJ, et al. Nature. 2014;516:428–431. doi: 10.1038/nature13906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walter DM, et al. Cancer Res. 2017;77:1719–1729. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson EL, et al. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3243–3248. doi: 10.1101/gad.943001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madisen L, et al. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:133–140. doi: 10.1038/nn.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jonkers J, et al. Nat Genet. 2001;29:418–425. doi: 10.1038/ng747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakada D, Saunders TL, Morrison SJ. Nature. 2010;468:653–658. doi: 10.1038/nature09571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chiou SH, et al. Genes Dev. 2015;29:1576–1585. doi: 10.1101/gad.264861.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sage J, Miller AL, Pérez-Mancera PA, Wysocki JM, Jacks T. Nature. 2003;424:223–228. doi: 10.1038/nature01764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DuPage M, Dooley AL, Jacks T. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1064–1072. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rogers Z. Protoc Exch. 2017 doi: 10.1038/protex.2017.090. [DOI]

- 29.Rogers Z. Protoc Exch. 2017 doi: 10.1038/protex.2017.091. [DOI]

- 30.Caunt M, et al. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:331–342. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Curtis C, et al. Nature. 2012;486:346–352. doi: 10.1038/nature10983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All major components of this study have been made publicly available. Plasmids have been described previously7 and are available on Addgene (see URLs). H11LSL-Cas9 mice are available from Jackson Laboratories (Jax 027650, 028239, 026816, 027632) and combination of strains can be requested directly from our laboratory. Tuba-seq protocols, including lentiviral vector barcoding28, genomic DNA extraction and library preparation29, are available on Protocol Exchange.

The Tuba-seq pipeline has been publicly released (see URLs). The code used for this experiment has been archived, but is also under active open-source development for improved general use. Raw sequencing files and processed tumor calls from every mouse are available on GEO (GSE107716). Statistical analysis code used downstream of tumor calls was described previously7 and outlined above. We encourage direct contact with the authors who designed protocols and software, as best practices will evolve over time.