Abstract

This observational cohort study evaluated the effect of a second blood pressure (BP) measurement on the rate of BP control among more than 38 000 patients with diagnosed hypertension and who were followed in primary care.

Hypertension (HTN) is an important clinical problem affecting nearly 80 million people in the United States.1 Despite the recognized importance of blood pressure (BP) control for those with HTN, only 54% of patients with HTN seen in primary care have their BP controlled (defined as systolic BP <140 mm Hg and diastolic BP <90 mm Hg).1 Blood pressure measurement error (including inappropriate cuff size, talking during measurement, terminal digit preference, and incorrect arm and body positioning) is a major cause of poor BP control2 and reducing measurement error has the potential to avoid overtreatment. The American Heart Association recommends repeating a BP measurement at the same clinic visit with at least 1 minute separating BP readings,2 yet in busy primary care practices BP often is measured only once. We evaluated the effect of a second BP measurement on the rate of BP control among more than 38 000 patients with diagnosed HTN and followed in primary care.

Methods

MetroHealth granted institutional review board approval and waived the requirement for written informed consent. As part of ongoing quality improvement, we introduced an advisory alert into our electronic health record (EHR) to remind staff to remeasure the BP when the initial BP was elevated (≥140/90 mm Hg). To assess the association of repeated BP measurement with BP control, we queried the EHR to obtain all recorded BP values for patients with a problem list diagnosis of HTN who were seen in a primary care clinic between January 1 and December 31, 2016, at MetroHealth, an urban safety-net system in Cleveland, Ohio. Our primary outcomes were (1) the change in systolic BP (final minus initial reading) among patients with an initially elevated BP (≥140/90 mm Hg) who had a repeated measurement during the same visit and (2) the proportion of patients whose BP was controlled on the final reading overall and stratified by initial systolic BP level. We also assessed the contribution of regression to the mean3 to the systolic BP change.

Results

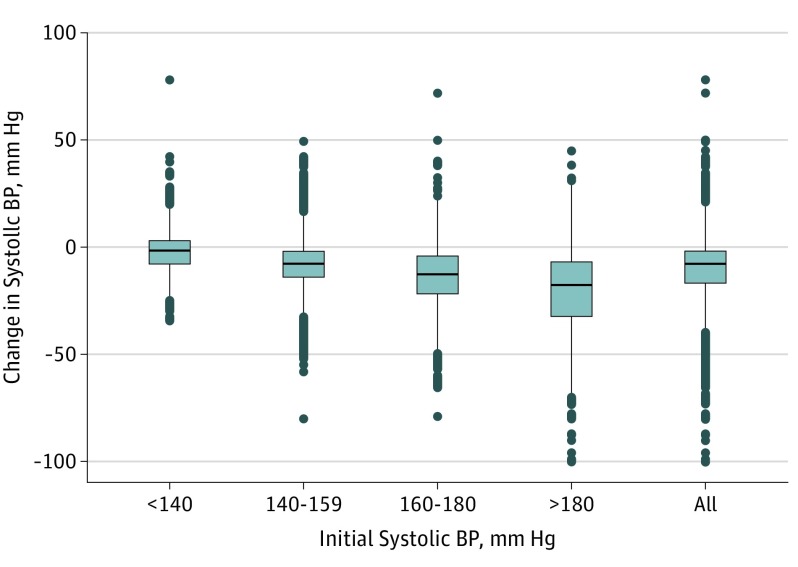

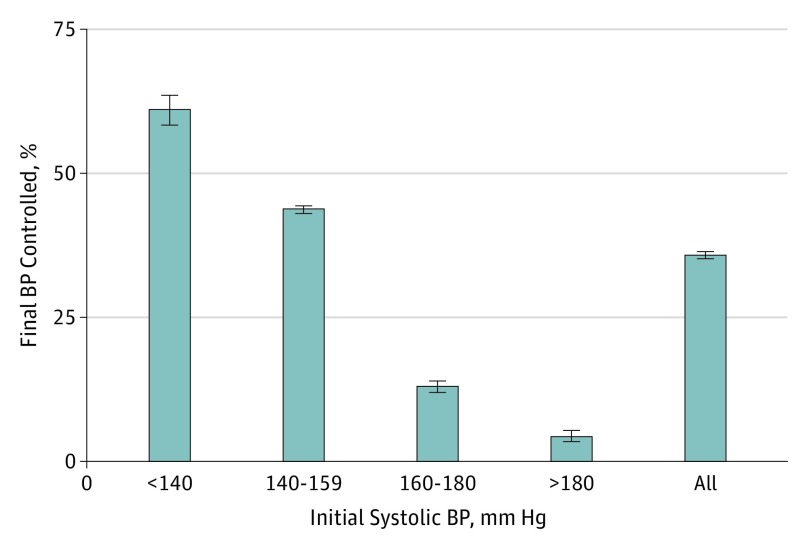

During the study period, 38 260 patients with HTN made 80 864 primary care office visits. The mean age was 61 years, 22 623 (59%) were female, 16 301 (43%) were black, and 10 340 (27%) were on Medicaid and 2105 (6%) were uninsured. The initial BP was at least 140/90 mm Hg at 31 531 visits (39%) and an initially elevated BP was remeasured at 26 089 visits (83%). The median change (final minus initial reading) in systolic BP was −8 mm Hg (interquartile range, 2-17 mm Hg). The change in systolic BP was positively associated with the initial BP value; the higher the initial systolic BP, the greater the change in final systolic BP (Figure 1). Among all patients with a repeated BP measurement, 9358 (36%) of final BP readings were lower than 140/90 mm Hg, with those closest to the threshold more likely to be controlled on repeated measurement (Figure 2). Overall, repeated measurement of an initially elevated BP was associated with increased HTN control rate from 61% to 73%. The estimated effect of regression to the mean was 6.1 mm Hg, accounting for nearly 65% of the mean observed decrease in systolic BP.

Figure 1. Median Change in Systolic Blood Pressure (BP) by Subgroup.

Boxes show the median as the line across the middle and the 25th and 75th percentiles as ends. Lines represent the 25th percentiles – 1.5 × (75th – 25th percentile) and the 75th percentile +1.5 × (75th – 25th percentiles). Dots represent observations that were outliers.

Figure 2. Proportion of Visits in Which Initially Elevated Blood Pressure (BP) Was Controlled on Repeated Measurement by Initial Systolic BP (in mm Hg).

Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

Discussion

Among a large sample of patients with HTN, repeated measurement of an initially elevated BP was associated with a median of 8 mm Hg improvement in systolic BP. Our result agrees with the 11 mm Hg-decrease recently described in a sample of 73 primary care patients.4 While much of the change in systolic BP may be attributed to regression to the mean, the observed decrease remains clinically important, comparable with that associated with addition of an antihypertensive medication.5 As the health care system moves toward value-based care initiatives, such as accountable care organizations and shared savings programs, implementing routine repeated measurement for an initially elevated BP may contribute to improved decision making around HTN management and should be considered a standard component of programs to improve BP control.

References

- 1.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. ; Writing Group Members; American Heart Association Statistics Committee; Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart disease and stroke statistics-2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133(4):e38-e360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, et al. ; Council on High Blood Pressure Research Professional and Public Education Subcommittee, American Heart Association . Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans: an AHA scientific statement from the Council on High Blood Pressure Research Professional and Public Education Subcommittee. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2005;7(2):102-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shepard DS, Finison LJ. Blood pressure reductions: correcting for regression to the mean. Prev Med. 1983;12(2):304-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daimee UA, Done D, Tang W, Tu XM, Bisognano JD, Bayer WH. The utility of repeating automated blood pressure measurements in the primary care office. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016;18(3):250-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002;288(23):2981-2997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]