With spreading applications of fluorescent quantum dots (QDs) in biomedical fields in recent years, there is increasing concern over their toxicity.

With spreading applications of fluorescent quantum dots (QDs) in biomedical fields in recent years, there is increasing concern over their toxicity.

Abstract

With spreading applications of fluorescent quantum dots (QDs) in biomedical fields in recent years, there is increasing concern over their toxicity. Among various factors, surface ligands play critical roles. Previous studies usually employed QDs with different kinds of surface ligands, but general principles were difficult to be obtained since it was hard to compare these surface ligands with varied chemical structures without common features. Herein, the physicochemical properties of two types of CdTe QDs were kept very similar, but different in the surface ligands with mercaptoacetic acid (TGA) and 3-mercaptopropionic acid (MPA), respectively. These two types of homologous ligands only had a difference in one methylene group (–CH2–). The interactions of the two types of CdTe QDs with bovine serum albumin (BSA), which was one of the main components of cell culture, were studied by fluorescence, UV-vis absorption, and circular dichroism spectroscopy. It was found that the fluorescence quenching of BSA by CdTe QDs followed a static quenching mechanism, and there was no obvious difference in the Stern–Volmer quenching constants and binding constants. The thermodynamic parameters of the two types of QDs were similar. BSA underwent conformational changes upon association with these QDs. By comparing the cytotoxicity of these two types of QDs, TGA-capped QDs were found to be less cytotoxic than MPA-capped QDs. Besides, in the presence of serum proteins, the cytotoxicity of the QDs was reduced. QDs in the absence of serum proteins had a higher internalization efficiency, compared with those in the medium with serum. To the best of our knowledge, this is a rare study focusing on surface ligands with such small variations at the biomolecular and cellular levels. These findings can provide new insights for the design and applications of QDs in complex biological media.

Introduction

Compared with conventional organic dyes, fluorescent semiconductor quantum dots (QDs) exhibit excellent properties such as broad absorption, narrow emission, high photoluminescence quantum yields, tunable emission wavelength, and anti-photobleaching.1 As a result, QDs have important biomedical applications in imaging, tracking, bioanalysis and so on.2–4 However, the potential toxicity of QDs and the released heavy metal ions has attracted much attention.5–11 When QDs are exposed to living systems, strong adsorption of various proteins takes place. The biological response of cells and organisms to exposure to QDs crucially depends on the properties of the protein adsorption layer forming on the surfaces, the so-called “protein corona”.12 On the other hand, once QDs interact with proteins, they might alter the protein conformation, and influence the normal protein function, which could induce unexpected biological reactions and lead to toxicity.13

Recently, some studies reported the interactions between proteins and nanoparticles (NPs).14 It was reported that surface charge and size have great influence on the interactions between nanoparticles and proteins. Our previous study showed that the interactions between negatively charged QDs and human serum albumin (HSA) were mainly based on the formation of complexes, whereas the interaction mechanism between the positive QDs and HSA was significantly different.15 The interactions between negatively charged QDs and HSA occurred due to the adsorption behavior, which depended on the nanoparticle itself rather than on the ligands, and the adsorption of HSA onto the surface of positively charged QDs would result in the aggregation of nanoparticles. Our recent study analyzed the adsorption of plasma proteins on Au nanoclusters (NCs). The results showed that the interaction enthalpy and entropy changes depended on the properties of proteins. Thermodynamic studies indicated that the interactions between Au NCs and HSA and γ-globulins were driven by hydrophobic forces, and the electrostatic interactions played predominant roles in the adsorption process for transferrin.16 Most studies focused on Au NCs,17,18 Ag NCs,19,20 magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles,21,22 carbon nanotubes,23,24 and CdSe@ZnS QDs.25 Although there were a few reports about the interactions between plasma proteins and CdTe QDs, little was known about the effect of surface ligands on the interaction of CdTe QDs with plasma proteins and the cytotoxicity influenced by the protein corona until now.

Serum albumins are the most abundant proteins in plasma.26 As the major soluble protein constituents of the circulatory system, they have many physiological functions.27 Among the serum albumins, bovine serum albumin (BSA) has a wide range of physiological functions involving binding, transportation and delivery of endogenous and exogenous substances in blood.28 It contains 583 amino acid residues with a molecular weight of 66 430,29 and two tryptophan moieties at positions 134 and 212, as well as tyrosine and phenylalanine.30 BSA was the major component of the protein corona formed after the exposure of QDs to the cell culture. So, we selected BSA as a model protein.

Among various factors, surface ligands are critical. Previous studies usually employed QDs with different surface ligands, e.g. glutathione (GSH), N-acetylcysteine (NAC), 3-mercaptopropionic acid (MPA), etc., but general principles were difficult to be obtained from these QDs since it was hard to compare these surface ligands with varied chemical structures without common features. In the present work, we synthesized mercaptoacetic acid (TGA) capped CdTe QDs (TGA-CdTe QDs) and MPA capped CdTe QDs (MPA-CdTe QDs) (Chart 1). Attempts to synthesize more homologous ligand-capped CdTe QDs failed. 4-Mercaptobutyric acid (MBA) and 5-mercaptovaleric acid (MVA) were not easily available. There is no report on CdTe QDs modified with MBA or MVA. Regarding mercapto acids with longer carbon chains, 6-mercaptohexanoic acid (MHA) and 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid (MUA) were not used in the aqueous phase synthesis of CdTe QDs because of their very poor water solubility. As a result, CdTe QDs capped with MBA, MVA, MHA and MUA in the aqueous phase synthesis are far less than those capped with TGA and MPA. The physicochemical properties, e.g. size, hydrodynamic diameter and surface charge, of TGA- and MPA-CdTe QDs were kept very similar. These two types of homologous ligands only had a difference in one methylene group (–CH2–). This design will highly facilitate the inspection of possible results caused by small changes in surface properties. The interactions of QDs and BSA were determined using fluorescence, UV-vis absorption, and circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy. Particularly, we compared the cytotoxicity induced by TGA-CdTe QDs and MPA-CdTe QDs using the standard 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2-H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. We also addressed the question as to how the protein corona affects the uptake of QDs by using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry and flow cytometry, and the subsequent cytotoxicity. To the best of our knowledge, this is a rare example of studying the biological effects of surface properties with such minor variations (only one methylene group in the chemical structure of the surface ligand) toward proteins and cells.

Chart 1. Diagram of TGA or MPA-capped CdTe QDs. (a) Mercaptoacetic acid (TGA) capped CdTe QDs (TGA-CdTe QDs) and (b) 3-mercaptopropionic acid (MPA) capped CdTe QDs (MPA-CdTe QDs).

Experimental

Reagents

CdCl2 (99.99%), NaBH4 (99%), tellurium powder (99.999%, about 200 mesh), bovine serum albumin (BSA), 3-mercaptopropionic acid (MPA, 99%), mercaptoacetic acid (TGA, 99%), sodium chloride (NaCl), potassium chloride (KCl), potassium phosphate dibasic (K2HPO4), and potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KH2PO4) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. (China). Chlorpromazine hydrochloride (≥98%) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and used without further purification. Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Gibco Invitrogen. l-Glutamin, penicillin, streptomycin and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) were obtained from Amresco Inc. Other chemicals were of analytical reagent grade. Ultrapure water with 18.2 MΩ cm (Millipore Simplicity) was used in all synthesis.

Synthesis of CdTe QDs

The synthesis procedure of CdTe QDs was in accordance with the literature method with minor modifications.31 Briefly, 0.0368 g CdCl2 (0.2 mmol) was dissolved in 100 mL of ultrapure water bubbled with N2 for 30 min. Subsequently, 23.6 μL TGA (0.340 mmol) or 33.4 μL MPA (0.340 mmol) was added and the pH of the mixture was adjusted to 10 by dropwise addition of a 1 M NaOH solution under a N2 atmosphere. Then 0.05 g tellurium powder and 0.05 g NaBH4 were dissolved in 4 mL ultrapure water under vigorous stirring. When the freshly prepared NaHTe solution turned light purple, 200 μL NaHTe solution was added into a CdCl2 precursor solution. The resulting colloidal solution was refluxed under nitrogen flow at 100 °C for 6 h to obtain TGA-CdTe QDs and for 4 h to obtain MPA-CdTe QDs. The crude product was precipitated using acetone with centrifugation at 6500 rpm for 15 min and the resultant precipitate was re-dispersed in ultrapure water, and then kept at 4 °C in the dark for further use. The particle sizes of CdTe QDs were determined from the first absorption maximum of the UV-vis absorption spectra according to the following equation:32

|

1 |

where D denotes the particle size of the CdTe QD sample, and λ represents the wavelength of the first excitonic absorption peak of the corresponding sample.

Fluorescence spectroscopy

Fluorescence analyses were performed on an LS-55 fluorophotometer (PerkinElmer, USA) with a circulating bath. The excitation and emission wavelengths of BSA were 280 nm and 346 nm, respectively. Titrations were performed using trace syringes. The concentration of the proteins was kept at 2 μM, and CdTe QDs of different concentrations were added into the solution, resulting in fluorescence quenching.

UV-visible absorption spectroscopy

A spectrophotometer (Cary Series UV-Vis Spectrophotometer) was used to measure the absorption spectra of CdTe QDs. The absorption spectra were measured using a 1 cm quartz cell. The wavelength of the spectra was measured between 190 and 500 nm.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy

CD measurements were performed on a circular dichroism photomultiplier (Applied Photophysics Limited, UK) at 25 °C. The CD spectra of BSA were recorded in the range of 260–190 nm. The instrument was controlled using Chirascan software. Quartz cells with a path length of 0.1 cm were used, and the scanning speed was set at 200 nm min–1. Appropriate buffer solutions, measured under the same experimental conditions, were taken as blanks and subtracted from the sample spectra. Each spectrum was the average of three scans.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) and zeta potential measurements

DLS and zeta potential measurements were performed using a Malvern ZetasizerNanoZS instrument. Samples were prepared in PBS at a concentration of 1 nM QDs and measurements were performed at 25 °C. For the diameter, the average and standard deviation of 3 measurements were reported, and for the zeta potential, the average and standard deviation of 3 measurements were reported.

Cell culture

HeLa cells (cervical cancer cell line) were maintained in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum, and all growth media were supplemented with 1% l-glutamine and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Amersco). Cell culture was performed under a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C. For all experiments, cells were harvested from subconfluent cultures using trypsin and resuspended in a fresh complete medium before plating.

Cytotoxicity assay

The viability of cells in the presence of QD nanoparticles was investigated using the 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT, Sigma) assay. For the cell toxicity assay, HeLa cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well and cultured in 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 24 h. The cells were then incubated with TGA-QDs and MPA-QDs with or without serum. Next, cells were incubated in media containing 0.5 mg mL–1 of MTT for 4 h. The medium was then replaced with 150 μL dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and the absorbance was monitored at 570 nm using a microplate reader (Elx800, BioTek, USA). Relative cell viability was calculated as a percentage of the control group, to which QDs had not been added.

Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS)

HeLa cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. For uptake studies, 100 000 cells were seeded per well of a 6-well plate. The next day, the cells were incubated with 80 nM QDs in DMEM with or without serum for 4 h. The cells were then washed three times with PBS to remove excess QDs. The cells were collected by scraping in DMEM and counted using a hemacytometer (Hausser Scientific). The cells were then digested in 3% HCl in HNO3 for 1 h at 55 °C. These samples were diluted with an ICP matrix containing 2% HCl and 2% HNO3, and an internal standard was added to a final concentration of 1 ppb rhodium. The samples were then analyzed using an ICP-MS (Thermo Electron) to determine the Cd content. The reported values represent the average and standard deviation from three wells. The uptake of QDs, represented by the Cd content (ppb per cell), was calculated by dividing the total concentration by the cell number in each cell suspension.

Flow cytometry

HeLa cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. For uptake studies, 100 000 cells were seeded per well of a 6-well plate. The next day, the cells were incubated with 80 nM QDs in DMEM with or without serum for 4 h. After incubation with QDs, the culture medium was removed. Then the cells were trypsinized and washed twice with PBS buffer. The cells were analyzed using a flow cytometer (BD, USA). For statistical significance, at least 3000 cells were analyzed in each sample. The mean fluorescence intensity of each sample was plotted following dead cell and doublet exclusion. The values reported represent the mean and standard deviation of triplicate experiments with values normalized to the fluorescence associated with the HeLa cells studied. The samples were then analyzed on a flow cytometer.

Results

Characterization

In comparison with TGA-CdTe QDs, MPA-CdTe QDs have similar surface functional groups which contain a carboxylic acid and a thiol, but different lengths of the carbon chain (Chart 1). The absorption and fluorescence properties of the different TGA-CdTe QDs and MPA-CdTe QDs were characterized first. As shown in Fig. 1, the absorption maximum of both CdTe QDs is located at 520 nm. The emission maximum of TGA-CdTe QDs is located at 559 nm, and that of MPA-CdTe QDs is located at 561 nm. The fluorescence emission spectra of the two types of CdTe QDs are both narrow and symmetric, indicating their good size distribution. With Rhodamine B as the reference, the fluorescence quantum yields of TGA-CdTe QDs and MPA-CdTe QDs in aqueous solutions were determined to be 0.42 and 0.39, respectively. Under the irradiation of a UV lamp, both QDs exhibit bright fluorescence (insets in Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. UV-vis absorption spectra and fluorescence spectra of TGA-CdTe QDs (a) and MPA-CdTe QDs (b). The insets are the photographs of QDs under the irradiation of a UV lamp at 365 nm.

The particle sizes of CdTe QDs could be controlled simply by varying the reaction time and were determined using eqn (1). The results showed that the particle sizes of the as-prepared CdTe QDs were ∼2.8 nm with the first absorption maximum of 520 nm. The TEM images indicated that these QDs were nearly spherical with good size distribution and excellent monodispersity (Fig. S1†) and their concentrations were calculated from their absorption using the Lambert–Beer's law:

| A = εcl | 2 |

where A is the absorbance of CdTe QDs at the first excitonic absorption peak, c is the concentration of CdTe QDs, l is the path length of the radiation beam and ε represents the molar extinction coefficients of QDs, which could be obtained from the formula: ε = 10 043 × D2.32

Fluorescence spectroscopic studies

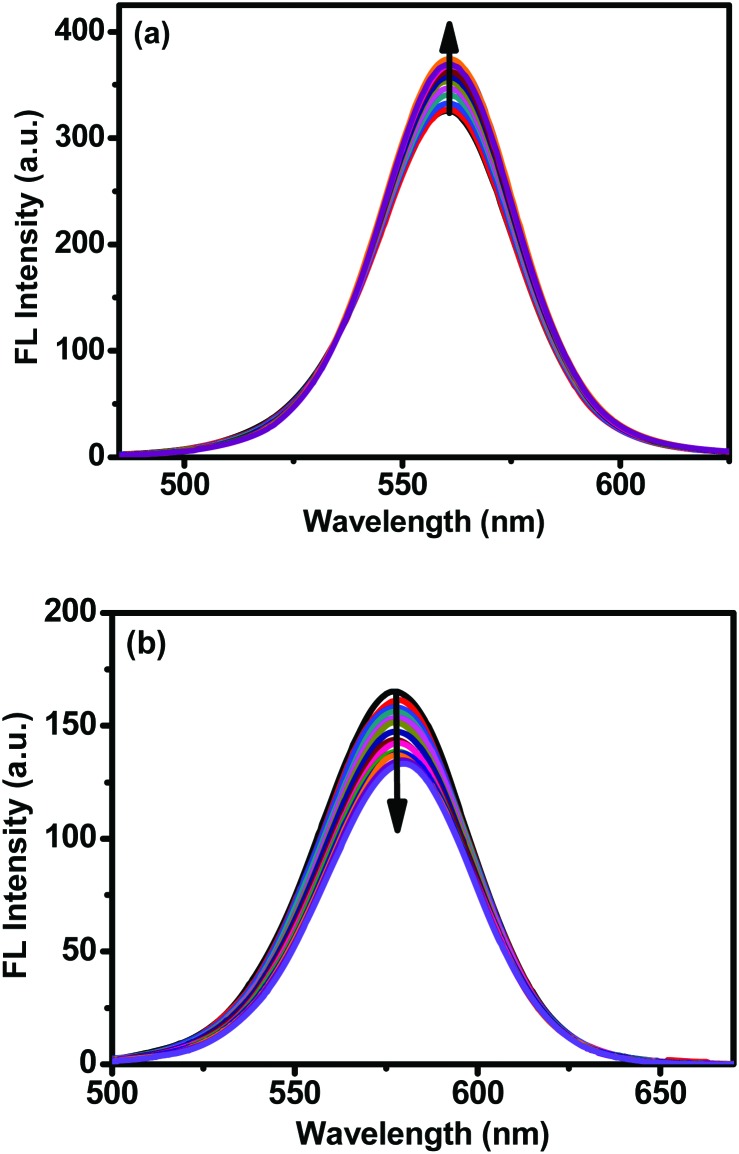

Fluorescence spectroscopy is widely used in the field of biological systems and molecular biophysics. Like many biophysical techniques, e.g. molecular dynamics simulations,33–36 fluorescence spectroscopic studies can be carried out at many levels ranging from a simple measurement of steady state emission to quite sophisticated time-resolved studies, for the interactions of biomolecules with small molecules, macromolecules, nanoparticles, etc.15,16 First, we considered the effects of serum protein on the CdTe QDs (Fig. 2). It was found that the fluorescence of TGA-CdTe QDs was enhanced by ∼10% in the presence of BSA. In contrast, the fluorescence of MPA-CdTe QDs decreased by ∼20% when exposed to BSA. This demonstrated that TGA-CdTe QDs were more stable.

Fig. 2. Effects of BSA on the fluorescence emission spectra of TGA-CdTe QDs (a) and MPA-CdTe QDs (b). [QDs] = 0.2 μM. [BSA] = 0–0.01 μM.

BSA has an intrinsic fluorescence peak contributed by amino acids tryptophan, tyrosine and phenylalanine at approximately 346 nm, which is mainly attributed to its tryptophan when the excitation is around 280 nm. We stabilized the concentration of BSA at 2 × 10–6 M. As shown in Fig. 3, both QDs could quench the intrinsic fluorescence of BSA. There are varieties of reasons which can result in the quenching of the fluorescence intensity, including energy transfer, complex formation, collision quenching, etc. Generally, the quenching mechanism can be classified into static and dynamic mechanisms. Both mechanisms can be expressed using the Stern–Volmer equation,37

| F0/F = 1 + KSV[Q] | 3 |

where F0 and F are fluorescence intensities in the absence and presence of the QDs, [Q] is the concentration of CdTe QDs, and KSV is the Stern–Volmer quenching constant. Higher temperature results in the dissociation of weakly bound complexes in static quenching; so KSV will reduce with higher temperature. In contrast, dynamic quenching is induced by collision; so higher temperature leads to larger KSV. From Table 1, it could be deduced that the interactions of QDs with BSA obey the static quenching mechanism since KSV is inversely correlated with temperature. The KSV for MPA-CdTe QDs is ∼2 fold lager than that for TGA-CdTe QDs.

Fig. 3. Fluorescence spectra of BSA in the absence and presence of TGA-CdTe QDs (a) and MPA-CdTe QDs (b). [BSA] = 2 μM.

Table 1. Stern–Volmer quenching constants KSV and binding constants Ka for the interactions of CdTe QDs with BSA.

| T (K) | K SV (106 L mol–1) | R 2 | K a (106 L mol–1) | R 2 | |

| TGA-CdTe QDs | 297 | 4.46 | 0.9990 | 2.53 | 0.9996 |

| 304 | 4.02 | 0.9993 | 2.03 | 0.9996 | |

| 310 | 3.88 | 0.9987 | 1.39 | 0.9997 | |

| MPA-CdTe QDs | 298 | 5.75 | 0.9990 | 5.24 | 0.9996 |

| 306 | 5.12 | 0.9993 | 3.68 | 0.9993 | |

| 310 | 4.99 | 0.9987 | 3.12 | 0.9993 |

Thermodynamics of the interactions of QDs with BSA

UV-vis absorption spectroscopy is a very simple and applicable method to explore the structural changes and complex formations.38 Thus, the absorption spectra of BSA, QDs and BSA–QD mixture were examined to further distinguish static and dynamic quenching. Dynamic quenching is largely caused by collision and merely affects the excited state of a fluorophore (BSA) and no variations occur in the absorption spectrum of the fluorophore, but a BSA–QD complex often forms during the static process and the UV-vis absorption spectrum changes. The difference absorption spectrum between BSA–QD system and QDs is obtained simply by subtraction of the absorption spectrum of BSA together with QDs by that of QDs. If there is no complex formed between BSA and QDs, the difference spectrum will overlap with the absorption spectrum of BSA. As shown in Fig. 4, the UV-vis absorption spectrum of BSA (red line) could not overlap with the difference absorption spectrum between BSA–QD system and QDs (black line) in the same wavelength range. These results confirmed the ground state complex formation of QDs with BSA and the static fluorescence quenching mechanism of the BSA–QD system, indicating that the fluorescence of BSA was mainly quenched by QDs through a static process.

Fig. 4. UV-vis absorption spectra of CdTe QDs. (a) Difference absorption spectrum between BSA–TGA-CdTe QD system and CdTe QDs. (b) Difference absorption spectrum between BSA–MPA-CdTe QD system and CdTe QDs. [BSA] = 2.0μM, [QDs] = 2.0 μM.

For the static quenching process, the data can be further analyzed through the modified Stern–Volmer equation:39

|

4 |

Herein, fa represents the molar fraction of the solvent-accessible fluorophore. Ka, which represents the effective quenching constant for the accessible fluorophore, is analogous to the associative binding constant for the quencher-acceptor. The dependence of F0/F on the reciprocal value of the QD concentration ([Q]–1) is fixed on the ordinate. The constant Ka is a quotient of an intercept fa–1 and slope (faKa)–1. As shown in Table 1, the binding constant also decreased with the increasing temperature, which was in accordance with the variation trend of KSV.

The binding forces can be elucidated using the thermodynamic parameters. The enthalpy change (ΔH) can be evaluated using the van't Hoff eqn (5).

|

5 |

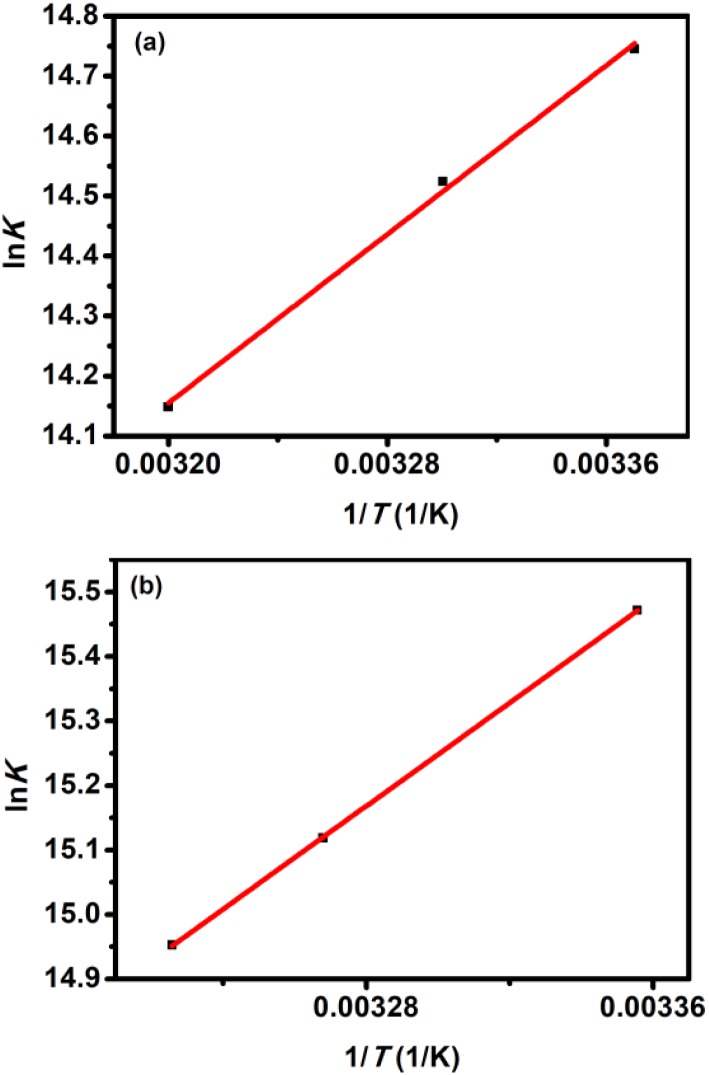

where Ka is analogous to the binding constants at the corresponding temperature, and R is the gas constant. As shown in Fig. 5, the enthalpy change (ΔH) was calculated from the slope of the van't Hoff relationship. The free energy change (ΔG) is then calculated from the following eqn (6):

| ΔG = –RT ln Ka | 6 |

Fig. 5. van't Hoff plots of QD–BSA systems: (a) TGA-CdTe QD–BSA system and (b) MPA-CdTe QD–BSA system.

The entropy change (ΔS) is then calculated from eqn (7):

| ΔG = ΔH – TΔS | 7 |

Negative ΔG demonstrated that the adsorption of BSA onto CdTe QDs was a spontaneous process. Furthermore, the binding forces were electrostatic as indicated by the negative ΔH and positive ΔS (Table 2).40 However, there are almost no differences among the thermodynamic parameters between TGA-CdTe QDs and MPA-CdTe QDs, indicating a similar principle for the adsorption of protein onto both CdTe QDs. So, we need a comprehensive evaluation strategy to find out and amplify these subtle differences.

Table 2. Thermodynamic parameters of the interactions of QDs with BSA at 298 K.

| ΔH (kJ mol–1) | ΔG (kJ mol–1) | ΔS (J mol–1 K–1) | R 2 | |

| TGA-CdTe QDs | –29.24 | –36.40 | 24.03 | 0.995 |

| MPA-CdTe QDs | –33.26 | –38.07 | 16.96 | 0.999 |

Secondary structural changes of BSA

CD spectroscopy makes it easy to analyze the secondary structural variations of proteins. Two negative bands appear at around 208 and 222 nm in the ultraviolet region, respectively, which are characteristic of the α-helix of a protein. The addition of QDs caused a decrease in both bands of BSA (Fig. 6), indicating that the binding of BSA to the surface of the QDs caused conformational alterations of proteins. The above-mentioned results might be attributed to the formation of a complex between BSA and QDs, which induced the conformational changes of proteins. Since the α-helix is one of the elements of the secondary structure, the structure change of BSA could be evaluated from the content of the α-helix structure. The CD spectra were analyzed using the algorithm SELCON3, with 43 model proteins with known precise secondary structures being used as the reference set. The percentages of different secondary structures for BSA in the absence and presence of QDs are all presented in Table 3.

Fig. 6. CD spectra of BSA in the presence of different concentrations of CdTe QDs. [CdTe QDs] = 0.8 μM. [BSA] = 4 μM.

Table 3. Fractions of the secondary structure of BSA in the absence and presence of TGA-CdTe QDs and MPA-CdTe QDs.

| Systems | Fraction of secondary structures |

|||

| α-Helix (%) | β-sheet (%) | Turn (%) | Random (%) | |

| BSA | 51.5 | 7.5 | 15.7 | 26.2 |

| BSA + TGA-CdTe QDs | 43.9 | 12.4 | 17.7 | 27.2 |

| BSA + MPA-CdTe QDs | 43.0 | 12.1 | 17.9 | 27.3 |

Hydrodynamic sizes and zeta potentials

DLS studies have confirmed the equilateral triangular prism model shape from the X-ray structure for (bovine) serum albumin in solution, using triangular sides of 8.4 nm and a thickness of 3.15 nm.41 In the DLS experiments, the results showed that the hydrodynamic sizes of QDs increased with the addition of BSA until they reached a plateau (Table 4). ΔRH, namely the thickness of the BSA layer, is a key parameter based on which we can obtain the adsorption of BSA on surfaces of CdTe QDs. To assess the adsorption orientation of transferrin (Tf) onto chiral surfaces of AuNPs, Chen et al. employed DLS to determine changes in the hydrodynamic radius(RH) of Pen-AuNPs before and after interacting with Tf. RH represents the mean z-average hydrodynamic diameter calculated using the method of cumulants.42 Herein, the ΔRH value was ∼3 nm for both CdTe QDs. The results were in accordance with previous reports.12,43 In the meantime, we monitored the changes of the surface zeta potential of QDs with the addition of BSA (Table 5). Results showed that the zeta potentials of QDs decreased after the addition of BSA. It indicated that BSA attached to the surface of QDs and changed the surface charges.

Table 4. Variation in size distribution of QDs in the presence of BSA.

| [TGA-CdTe QDs] : [BSA] | Size (nm) | [MPA-CdTe QDs] : [BSA] | Size (nm) |

| 1 : 0 | 5.93 ± 1.16 | 1 : 0 | 6.07 ± 1.89 |

| 1 : 1 | 7.39 ± 1.45 | 1 : 1 | 6.37 ± 0.77 |

| 1 : 2 | 7.67 ± 1.37 | 1 : 2 | 7.18 ± 1.20 |

| 1 : 3 | 8.16 ± 1.74 | 1 : 3 | 8.18 ± 1.13 |

| 1 : 4 | 8.59 ± 1.41 | 1 : 4 | 8.42 ± 1.23 |

| 1 : 5 | 8.78 ± 1.50 | 1 : 5 | 8.70 ± 1.21 |

| 1 : 6 | 8.87 ± 1.47 | 1 : 6 | 8.41 ± 1.24 |

Table 5. Zeta potential in the absence and presence of QDs. [BSA] = [QDs] = 2 μM.

| ζ (mV) | ζ (mV) | ||

| TGA-CdTe QDs | –38.4 | MPA-CdTe QDs | –36.6 |

| BSA | –6.46 | BSA | –6.46 |

| TGA-CdTe QDs + BSA | –13.4 | MPA-CdTe QDs + BSA | –13.9 |

Cytotoxicity

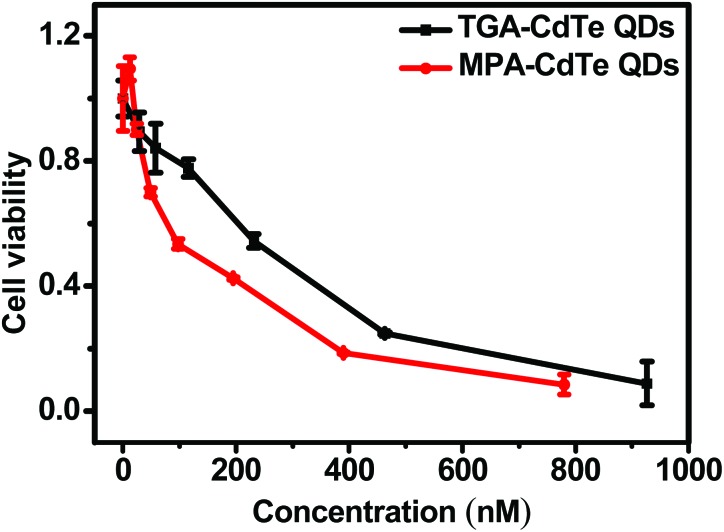

Based on the above results with BSA, we then performed an experiment to determine whether the lengths of ligands influenced the cytotoxicity of QDs using the standard MTT assay. We found that TGA-CdTe QDs caused less cytotoxicity than MPA-CdTe QDs (Fig. 7). Half inhibitory concentration (IC50), with serum in medium (serum is contained in most biological media), for TGA-CdTe QDs was 0.243 ± 0.023 μM while that for MPA-CdTe QDs was 0.138 ± 0.020 μM (Table 6). Since the two types of QDs had similar physicochemical properties, the stability and subsequent release of cadmium ions might be responsible for their cytotoxicity. A previous study found that TGA-capped QDs were stable for about 16–19 days at room temperature while MPA-capped QDs were stable only for 8–10 days.44 Besides, theoretical investigations were performed to find the nature of ligand's effect on the stability of the capped QDs. The calculated theoretical data revealed that TGA formed a more stable complex with metal ions than MPA. The stable surface coating of the QDs prevents their oxidation and avoids the release of cadmium ions, a known toxin and suspected carcinogen.45 Our recent study showed that TGA-CdTe QDs and MPA-CdTe QDs could impair mitochondrial energy metabolism and affect mitochondrial lipid peroxidation.46 The QDs could also induce membrane permeability transition (MPT) as evidenced by mitochondrial swelling, decreased membrane fluidity and collapsed membrane potential. However, TGA-CdTe QDs had a smaller effect on the MPT compared with MPA-CdTe QDs, which could be explained by the better stability of TGA-CdTe QDs. Our previous study also found that the percentage of released cadmium ions by MPA-CdTe (3.50%), when exposed to biological systems, was ∼10 fold larger than that by TGA-CdTe QDs (0.34%). Therefore, the more stable the TGA-CdTe QDs were, the less cytotoxicity was exhibited.

Fig. 7. Effects of QDs on cell viability determined by the MTT assay. HeLa cells were incubated with different doses of QDs for 24 h.

Table 6. IC50 (μM) of CdTe QDs with or without serum.

| Serum free | With serum | |

| TGA-CdTe QDs | 0.076± 0.003 | 0.243 ± 0.023 |

| MPA-CdTe QDs | 0.037 ± 0.007 | 0.138 ± 0.020 |

Moreover, it is noteworthy that CdTe QDs with serum exhibited much less cytotoxicity than those without serum, as indicated by the 3–4 fold larger IC50 in the presence of serum (Table 6). Serum proteins might have a protective effect on the toxicity of CdTe QDs. When proteins attached onto QDs, they would form protein corona, thus hindering the release of cadmium ions by QDs, while the bare QDs possessed high surface energy, resulting in stronger adhesion to the cell membrane and subsequent cell damage.

Cell uptake

It has been observed that the uptake of nanoparticles under serum-free conditions is, in most cases, higher than that measured for the same nanoparticles in the presence of serum. Herein, inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) was employed to find out whether the serum caused any difference in the cell uptake or not, considering that the concentration of QDs inside cells could be represented by the cadmium element. To determine the effect of serum proteins on QDs’ uptake level, cells were incubated with QDs in medium without and with serum. By using this method, it can be found how uptake efficiency would vary when QDs were covered or not by a corona, prior to their interaction with cells. The cell uptake of TGA-CdTe QDs was less than that of MPA-CdTe QDs by HeLa cells, irrespective of the presence or absence of serum (Table 7). This was not unexpected since the MTT assay had proved that TGA-CdTe QDs were less cytotoxic than MPA-CdTe QDs. Uptake and association of both QDs to HeLa cells in the presence of serum was altered to some extent. When QDs were exposed to cells under serum-free conditions, cell uptake was higher, which was in accordance with the MTT assay. Interestingly, the cell uptake of TGA-CdTe QDs (1.98 × 10–4 ppb per cell) was 76% of that of MPA-CdTe QDs (2.60 × 10–4 ppb per cell). This percentage was reduced to 59% when QDs were exposed to serum. It demonstrated that proteins could reduce the difference of cell uptake of different QDs. The proteins could act as a mask to cover the different surface properties of QDs, or a Trojan horse for QDs.

Table 7. The cell uptake of QDs by HeLa cells (10–4 ppb per cell).

| Serum free | With serum | |

| TGA-CdTe QDs | 1.98 ± 0.07 | 1.04 ± 0.01 |

| MPA-CdTe QDs | 2.60 ± 0.05 | 1.76 ± 0.04 |

This result was also confirmed by the flow cytometric studies. As QDs exhibited bright fluorescence upon irradiation, the cell uptake could be feasibly analyzed using a flow cytometer after incubation of cells with QDs. The two types of QDs had similar fluorescence quantum yields (0.42 and 0.39) in a buffer solution, and TGA-CdTe QDs were more photophysically stable (Fig. 2). The relative fluorescence intensity could represent the level of cell uptake. The relative fluorescence intensity of cells incubated with TGA-CdTe QDs was weaker than that of cells with MPA-CdTe QDs, regardless of treatment with serum or being serum free, indicating lower cell uptake of TGA-CdTe QDs (Fig. 8). Besides, the cell uptake was reduced in the presence of serum for both QDs.

Fig. 8. Flow cytometric analysis of the relative fluorescence intensity of cells incubated with TGA-CdTe QDs and MPA-CdTe QDs (80 nM) for 4 h. The relative fluorescence intensity can represent the relative quantity of cell uptake.

Conclusions

This work has realized an in-depth understanding of not only the interaction mechanisms between BSA and CdTe QDs but also the subsequent cytotoxicity of QDs. We have investigated the role of the length of the carbon chain of surface ligands on the protein binding of CdTe QDs. Given similar physical and chemical properties, the interactions between homologous ligand-capped QDs and serum proteins were similar. However, there were significant differences toward cells due to different stabilities of different ligand-capped QDs. In short, the more stable the QDs are, the less cytotoxicity they would cause. Furthermore, the greater cytotoxicity of MPA-CdTe QDs was partly attributed to their larger uptake by cells. Besides, when QDs were exposed to cells with serum proteins in cell culture, both the cell uptake and cytotoxicity were clearly reduced. This work will highly contribute to the design of biomedical QDs, and the understanding of how they will interact with proteins and behave in complex biological media.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21573168, 21773178, 21503283, and 21473125).

Footnotes

†Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/c7tx00301c

References

- Zhou J., Shirahata N., Sun H., Ghosh B., Ogawara M., Teng Y., Zhou S., Chu R. G. S., Fujii M., Qiu J. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2013;4:402–408. doi: 10.1021/jz302122a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voura E. B., Jaiswal J. K., Mattoussi H., Simon S. M. Nat. Med. 2004;10:993–998. doi: 10.1038/nm1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J. P., Guo W. W., Yin J. Y., Wang E. K. Talanta. 2009;77:1858–1863. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2008.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X. H., Cui Y. Y., Levenson R. M., Chung L. W. K., Nie S. M. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004;22:969–976. doi: 10.1038/nbt994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X. L., Lai L., Tian F. F., Jiang F. L., Xiao Q., Li Y., Yu Q. L. Y., Li D. W., Wang J., Zhang Q. M., Zhu B. F., Li R., Liu Y. Small. 2012;8:2680–2689. doi: 10.1002/smll.201200591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei J., Yang L. Y., Lai L., Xu Z. Q., Wang C., Zhao J., Jin J. C., Jiang F. L., Liu Y. Chemosphere. 2014;112:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.03.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai L., Jin J. C., Xu Z. Q., Mei P., Jiang F. L., Liu Y. Chemosphere. 2015;135:240–249. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai L., Jin J. C., Xu Z. Q., Ge Y. S., Jiang F. L., Liu Y. J. Membr. Biol. 2015;248:727–740. doi: 10.1007/s00232-015-9785-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. H., Liu X. R., Zhang Y., Tian F. F., Zhao G. Y., Yu Q. L. Y., Jiang F. L., Liu Y. Toxicol. Res. 2012;1:137. [Google Scholar]

- Ma L., Liu J. Y., Dong J. X., Xiao Q., Zhao J., Jiang F. L. Toxicol. Res. 2017;6:822–830. doi: 10.1039/c7tx00204a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan L., Gao T., He H., Jiang F. L., Liu Y. Toxicol. Res. 2017;6:621–630. doi: 10.1039/c7tx00079k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. X., Shang L., Maffre P., Hohmann S., Kirschhöfer F., Brenner-Weiß G., Nienhaus G. U. Small. 2016;12:5836–5844. doi: 10.1002/smll.201602283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai J., Wang T. T., Wang Y. C., Jiang X. E. Biomater. Sci. 2014;2:493–501. doi: 10.1039/c3bm60224a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan R., Lai L., Xu Z. Q., Jiang F. L., Liu Y. Acta Phys.-Chim. Sin. 2017;33:2377–2387. [Google Scholar]

- Lai L., Lin C., Xu Z. Q., Han X. L., Tian F. F., Mei P., Li D. W., Ge Y. S., Jiang F. L., Zhang Y. Z., Liu Y. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A. 2012;97:366–376. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2012.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin M. M., Dong P., Chen W. Q., Xu S. P., Yang L. Y., Jiang F. L., Liu Y. Langmuir. 2017;33:5108–5116. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.7b00196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacerda S. H., Park J. J., Meuse C., Pristinski D., Becker L. M., Karim A., Douglas J. F. ACS Nano. 2010;4:365–379. doi: 10.1021/nn9011187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang R. X., Carney R. P., Stellacci F., Lau B. L. T. Nanoscale. 2013;5:6928–6935. doi: 10.1039/c3nr02117c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravindran A., Singh N., Raichur A. M., Chandrasekaran N., Mukherjee A. Colloids Surf., B. 2010;76:32–37. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G. K., Lu Y. F., Hou H. M., Liu Y. F. RSC Adv. 2017;7:9393–9401. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q. Q., Liang J. G., Han H. Y. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:10454–10458. doi: 10.1021/jp904004w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong L. J., Hu J. X., Qin D., Yan P. J. Pharm. Innov. 2015;10:13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ge C. C., Du J. F., Zhao L. N., Wang L. M., Liu Y., Li D. H., Yang Y. L., Zhou R. H., Zhao Y. L., Chai Z. F., Chen C. Y. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:16968–16973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105270108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng J., Yang M., Wang C. Y., Kong H., Wang R., Wang C., Xie S. S., Xu H. Y. New Carbon Mater. 2007;22:218–226. [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf S., Park J., Bichelberger M. A., Kantner K., Hartmann R., Maffre P., Said A. H., Feliu N., Lee J., Lee D., Nienhaus G. U., Kim S., Parak W. J. Nanoscale. 2016;8:17794–17800. doi: 10.1039/c6nr05805a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willard D. M., Carillo L. L., Jung J., Orden A. V. Nano Lett. 2001;1:469–474. [Google Scholar]

- Carter D. C., Ho J. X. Adv. Protein Chem. 1994;45:153–203. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60640-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosa T., Maruyama T., Otagiri M. Pharm. Res. 1997;14:1607–1612. doi: 10.1023/a:1012138604016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirayama K., Akashi S., Furuya M., Fukuhara K. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1990;173:639–646. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80083-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X. M., Carter D. C. Nature. 1992;358:209–215. doi: 10.1038/358209a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou L., Gu Z. Y., Zhang N., Zhang Y. L., Fang Z., Zhu W. H., Zhong X. H. J. Mater. Chem. 2008;18:2807–2815. [Google Scholar]

- Yu W. W., Qu L. H., Guo W. Z., Peng X. G. Chem. Mater. 2003;15:2854–2860. [Google Scholar]

- He H., Xu J., Cheng D. Y., Fu L., Ge Y. S., Jiang F. L., Liu Y. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2017;121:1211–1221. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b10460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. R., Beugelsdijk A., Chen J. H. Biophys. J. 2015;109:1049–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. R., Jia Z. G., Chen J. H. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2017;121:9160–9168. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b06768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. R., Chen J. H. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017;19:32421–32432. doi: 10.1039/c7cp06736d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y. J., Liu Y., Xiao X. H. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10:517–521. doi: 10.1021/bm801120k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue F. F., Liu L. Z., Mi Y. Y., Han H. Y., Liang J. G. RSC Adv. 2016;6:10215–10220. [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer S. S. Biochemistry. 1971;20:3254–3263. doi: 10.1021/bi00793a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross P. D., Subramanian S. Biochemistry. 1981;20:3096–3102. doi: 10.1021/bi00514a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer M. L., Duchowicz R., Carrasco B., de la Torre J. G., Acuna A. U. Biophys. J. 2001;80:2422–2430. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76211-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. Y., Wang M. Z., Lei R., Zhu S. F., Zhao Y. L., Chen C. Y. ACS Nano. 2017;11:4606–4616. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b00200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Röcker C., Pötzl M., Zhang F., Parak W. J., Nienhaus G. U. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2009;4:577–580. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primerapedrozo O. M., Arslan Z., Rasulev B., Rasulev B., Leszczynski J. Nanoscale. 2012;4:1312–1320. doi: 10.1039/c2nr11439a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Shi D., Cho H., Dong Z., Kulkarni A., Pauletti G. M., Wang W., Lian J., Liu W., Ren L., Zhang Q., Liu G., Huth C., Wang L., Ewing R. C. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2008;18:2489–2497. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang X., Wu C., Zhang B. R., Gao T., Zhao J., Ma L., Jiang F. L., Liu Y. Chemosphere. 2017;184:1108–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.06.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.