The safety assessment of a flavour substance examines several factors, including metabolic and physiological disposition data.

The safety assessment of a flavour substance examines several factors, including metabolic and physiological disposition data.

Abstract

The safety assessment of a flavour substance examines several factors, including metabolic and physiological disposition data. The present article provides an overview of the metabolism and disposition of flavour substances by identifying general applicable principles of metabolism to illustrate how information on metabolic fate is taken into account in their safety evaluation. The metabolism of the majority of flavour substances involves a series both of enzymatic and non-enzymatic biotransformation that often results in products that are more hydrophilic and more readily excretable than their precursors. Flavours can undergo metabolic reactions, such as oxidation, reduction, or hydrolysis that alter a functional group relative to the parent compound. The altered functional group may serve as a reaction site for a subsequent metabolic transformation. Metabolic intermediates undergo conjugation with an endogenous agent such as glucuronic acid, sulphate, glutathione, amino acids, or acetate. Such conjugates are typically readily excreted through the kidneys and liver. This paper summarizes the types of metabolic reactions that have been documented for flavour substances that are added to the human food chain, the methodologies available for metabolic studies, and the factors that affect the metabolic fate of a flavour substance.

Introduction

This paper is intended for toxicologists and other scientists who are non-specialists in metabolism and unfamiliar with flavour ingredient safety assessment. This paper will provide an overview of the role of metabolism studies as they are considered in toxicological evaluations of chemically defined flavour substances. The paper will also underscore the role of metabolism in safety evaluation of chemically defined flavour substances.

Spices, herbs and other flavouring materials have been used since ancient times to add zest and quality to foods. They have been used by peoples of all cultures to make foods and beverages more attractive and enjoyable and in some cases to make the less agreeable flavours of some food ingredients more palatable. In the late nineteenth century, with the advent of large-scale food processing, there was an associated need to develop food flavours that could be incorporated into the new methods of mass food production on a commercial basis. In response to this need, new businesses in Germany and Switzerland initially expanded into this new area of flavour chemistry and technology and were responsible for developing bulk scale production of synthetic aromatic substances for use in the food industry. The great majority of these flavouring substances were identical to the flavour constituents occurring naturally in food. This subsequently led to efforts to “improve” the natural flavours through modifications of the molecular structure of natural substances, and in this way, numerous new substances have been created for use by the food industry. In more recent years, developments in molecular biology have enabled the cloning of taste receptors to support the discovery of a new generation of flavour substances, particularly those that can modify taste perception. These types of flavour ingredients are termed flavour modifiers or modulators.1

The addition of flavour ingredients to the human food supply is an important subject and the evaluation of their safety is paramount to protect public health. The safety evaluation of flavours is challenging for a number of reasons. First, the large number of substances concerned covers a broad swathe of chemical space and includes synthetic substances (those that are nature-identical as well as novel molecules), essential oils, oleoresins and extracts, immediately raising the question as to whether it is logistically possible to conduct full toxicological evaluation through animal and related studies. This leads to the second issue, which is an economic one: the volumes of use of many flavours can be very small (1–10 kg per year) worldwide so that there is no economic base to support a traditional full-scale toxicology evaluation program, considering that such a program could cost many hundreds of thousands of dollars per substance examined. Nevertheless, there are many data that are available and studies that can be conducted on flavours, including experimental studies and predictive assessments of metabolic fate.

It is clear that consideration of metabolism serves an important role in the safety evaluation of flavours. The objective of this paper is to address the role and importance of metabolic data in the safety evaluation of food flavouring substances. This paper will provide an overview of the principles of metabolism as applicable to flavours, the role of metabolism studies in flavour safety assessment decision-making, the types of metabolism data sought with scientific rationale, and the advantages and limitations. We will highlight important pathways and specific examples of the metabolism of known flavour ingredients to illustrate this foundational knowledge for non-specialists to the field. In order to better understand the role of metabolism information in the safety assessment process for flavour ingredients, we will first describe historical aspects of the regulatory framework for safety of flavour ingredients in the United States, and the basic elements to flavour safety assessment.

Over the past half-century, regulatory agencies worldwide and international health authorities including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the United Nation's Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA), the European Commission (Council of Europe, Scientific Committee on Food, and European Food Safety Authority (EFSA)) and the Japanese Food Safety Commission (JFSC) have considered the unique demands of administrative oversight and conduct of the safety evaluation of food flavour ingredients given the large number of substances involved.

In 1958, the United States Congress enacted the Food Additives Amendment to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act (FD&C Act)† . In the Amendment, Congress defined the term ‘food additive’ and also stated that ‘substances that are generally recognized, among experts qualified by scientific training and experience to evaluate their safety as having been adequately shown… to be safe under the conditions of their intended use’ are excluded from the definition. Thus, in the 1958 Amendment, Congress recognized that many food substances do not require a formal premarket review by the U.S. FDA to assure their safety because the safety of such substances has been established by the long history of safe use in food, or because the substance can be shown to be safe under its customary or projected conditions of use and the safety information on the substance is generally recognized and available to scientists. Under this regulatory concept, and as later delineated by the U.S. FDA in its proposed rule,2 these particular substances are referred to as “generally recognized as safe” under intended conditions of use, also termed GRAS. A brief history of the US food and drug law and of the development and application of the GRAS concept is provided on the US FDA's website‡ ,§ .

Historically, the first non-regulatory entity to perform the safety evaluation of flavours in a comprehensive and systematic way was a panel of expert scientists outside of the industry and appointed by the Flavor and Extract Manufacturers Association (FEMA), a U.S.-based trade association.3,4 This panel of scientists is an independent group of internationally-recognized experts qualified by training and experience to evaluate the safety of food ingredients. Starting in 1960, under the leadership of Drs Benjamin Oser and Richard Hall, this ‘expert panel’ known today as FEXPAN (FEMA Expert Panel), began its novel and pioneering program to assess the safety of flavour substances under the GRAS regulatory concept. Over the course of U.S. legislative and regulatory history of food ingredient safety that is founded in the provisions of the 1958 Amendment to the FD&C Act, the GRAS concept has matured into a food safety assessment mechanism that efficiently and effectively upholds the protection of public health. The FEXPAN has played a role in contributing to the public health success of GRAS with rigorous, objective, and scientifically sound determinations on the safety of flavouring ingredients proposed to be added to food for human consumption in the United States. One important element of the general recognition standard of GRAS is the publication of scientific data, information, methods, and principles that generate common knowledge about the safety of these substances.2 To the point of this paper, the FEXPAN has embraced this element of the GRAS concept over its history through detailed publications of the Panel's safety decisions, in-depth scientific literature reviews, and critical scientific interpretations on flavour ingredient safety assessment principles, procedures, and criteria.5–10 Collectively, these publications provide a transparent, comprehensive, consistent, and proactive approach to the evaluation of the safety of flavour ingredients in the context of protecting human health. The origins of these publications by the FEXPAN start with the publication of the GRAS 3 list.11

In the course of over 50 years, a series of GRAS lists have been published detailing the FEMA GRAS™ safety status of more than 2700 single chemically-defined substances and about 300 natural flavour complexes. Currently, the GRAS list is at its 27th publication (GRAS 27) and can be found in the journal Food Technology as well on FEMA's public website.10,12 The GRAS list publications specify the ingredient identity, conditions of intended use (e.g., permitted use levels and food categories), and the scientific basis and information supporting the determinations for each flavouring substance. The FEXPAN may also conclude a substance is no longer GRAS and remove it from the FEMA GRAS list in the publication (deGRASed). Reasons for a substance to be deGRASed may include identification of new data affecting a prior GRAS decision, in which case the re-evaluation of the substance by FEXPAN may lead to a request to the GRAS applicant for additional experimental studies to be performed in order to support safety under the intended use conditions. An additional reason may be the finding that the technical effect of flavouring for a particular substance is no longer in use.12 Thus, the safety determinations of flavouring substances are published in the public domain. Recognizing that the exchange of the flavour safety information and collaborative partnership with the government is important for public health, the information on FEMA GRAS determinations is also provided to the U.S. FDA. The U.S. FDA is the regulatory agency that has ultimate authority over the human safety of food ingredients added to the food supply in the United States. These communications serve an instrumental role for public knowledge of flavour safety and supporting public health.

Thus, the dissemination of the FEXPAN safety assessment practices helps the public to better understand the criteria applied to arrive at a safety decision on a flavour ingredient and its intended use conditions proposed as GRAS. The factors considered to establish the safety of a flavour substance are listed below. Importantly, if information for items d, f, and g (see below) are not available for the substance under evaluation, information available for structurally analogous chemicals may be relied upon, under expert judgment.

(a) Purity and manufacturing process.

(b) Estimates of human dietary intake through surveys of intended use levels and food categories for use of the flavour; assessment of potential exposure.

(c) Natural occurrence in foods.

(d) Toxicology studies of the flavouring substance and the relationship of levels of oral intake to threshold of toxicological concern (TTC), and No-Observed-Adverse-Effect-Level (NOAEL) values, and consideration of a Margin of Safety (MOS). Such studies could include reproductive and developmental toxicology studies, studies on receptor binding and the mechanism of action for toxicity.

(e) Chemical structure, functional group attributes, and physicochemical properties: Relation to other substances based on molecular structure in terms of substructural features and entire structural class; presence or absence of structural alerts for toxicity.

(f) Genotoxic potential of the substance under evaluation.

(g) Metabolism and physiological disposition of the substance under evaluation.

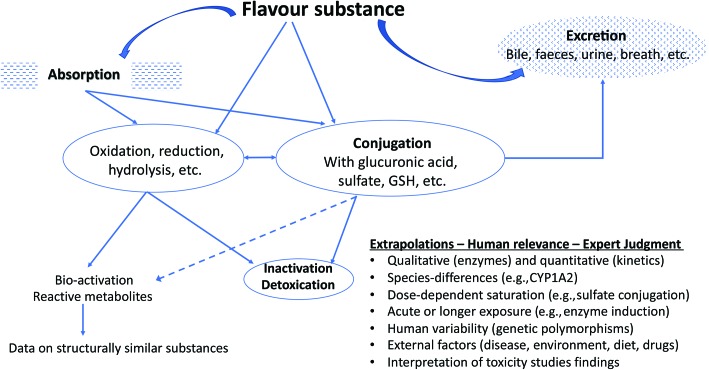

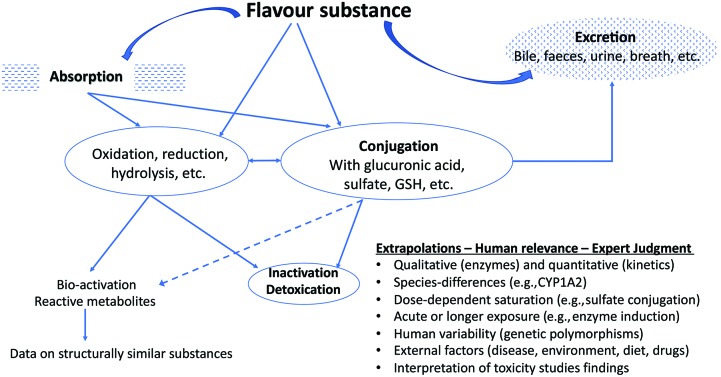

The above criteria are evidentiary standards applied to each individual flavour substance under review and consideration of a FEMA GRAS status. In the present review, we draw attention to criterion (g) ‘metabolism and physiological disposition of the substance under evaluation’ and will explain how this aspect is generally evaluated by the FEXPAN in GRAS evaluations on flavour substances. A representation of the considerations of metabolism in flavour substance safety evaluation is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Example of typical oxidative metabolism and conjugation reactions using flavour ingredients.

The metabolism of flavour substances: an overview

It is almost axiomatic that virtually all flavour substances, if absorbed, will undergo metabolic biotransformation in the body before their elimination. In this paper, the terms metabolism and biotransformation will be used synonymously. Also, use of the term xenobiotic is introduced in relation to chemicals foreign to the body and their biotransformation.13 The excretion of xenobiotic substances is an essential biological process that usually occurs after a metabolic step or biotransformation that converts the substance to a new product (i.e., metabolite). Excretion represents the removal or elimination of metabolites as waste products (from a mammalian organism) through the excretory system. Urine and faecal waste are the most commonly noted excretory matter, although sweat and exhalation also contribute to the expelling of waste to some degree. The removal of unnecessary materials from the body has likely evolved to avoid long-term accumulations of substances and is an effective way for the body to mitigate potential adverse effects from exposure to xenobiotics and their metabolites.

In terms of metabolic capacity, the body is endowed with a vast and complex network of enzymes distributed over practically all tissues and organs with varying levels of expression and catalytic activities.14–20 These enzymes are commonly referred to as xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes.21 Xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes in themselves or in combination with other enzymes, contribute to the biological function of biotransformation of xenobiotics through precise biochemical reactions that are enzyme specific and typically require the presence of endogenously produced cofactors. In general, the majority of flavour substances are metabolized, which underscores the purpose of this paper. The metabolites of flavours and other xenobiotics are generally more hydrophilic in character and more readily excretable than their precursors.

It is also important to point out that under normal conditions many flavour substances undergo normal intermediary metabolism, such as the processing of carboxylic acid metabolites through the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, or follow catabolic pathways yielding innocuous products. For example, amino acids such as alanine (FEMA 3818) undergo degradation and biotransformation (oxidative deamination) to α-keto acids that are completely oxidized to CO2 and water, or provide three or four carbon units that are converted via gluconeogenesis to produce glucose, or via ketogenesis to produce ketones.22 Another example is the flavour l-glutamate (FEMA 3285), which is deaminated in the mitochondria yielding NH4+vial-glutamate dehydrogenase. The ammonium ion is used either in other metabolic pathways, or converted to urea for excretion. Products from amino acid degradation ultimately enter the citric acid cycle (e.g., catabolism of alanine to acetyl coenzyme A). Although these occur with flavours, this paper will not focus on biotransformation of endogenous reactants.

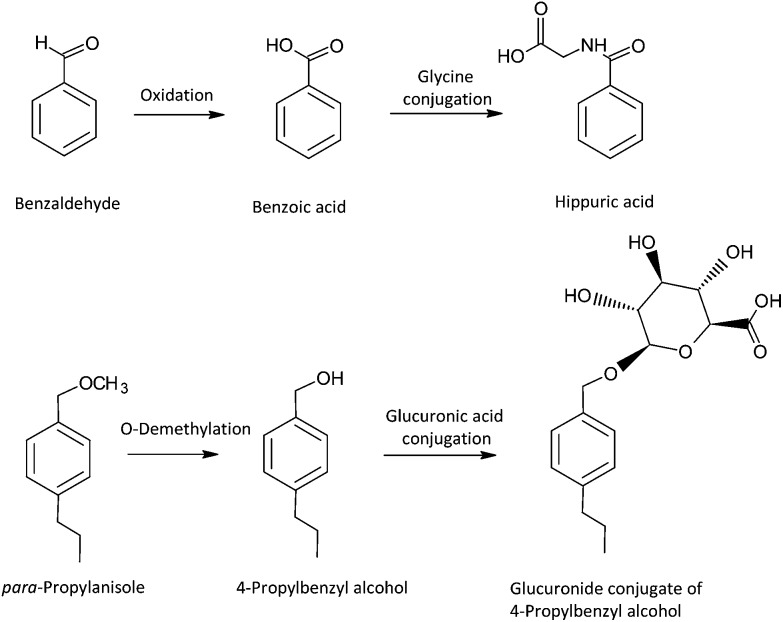

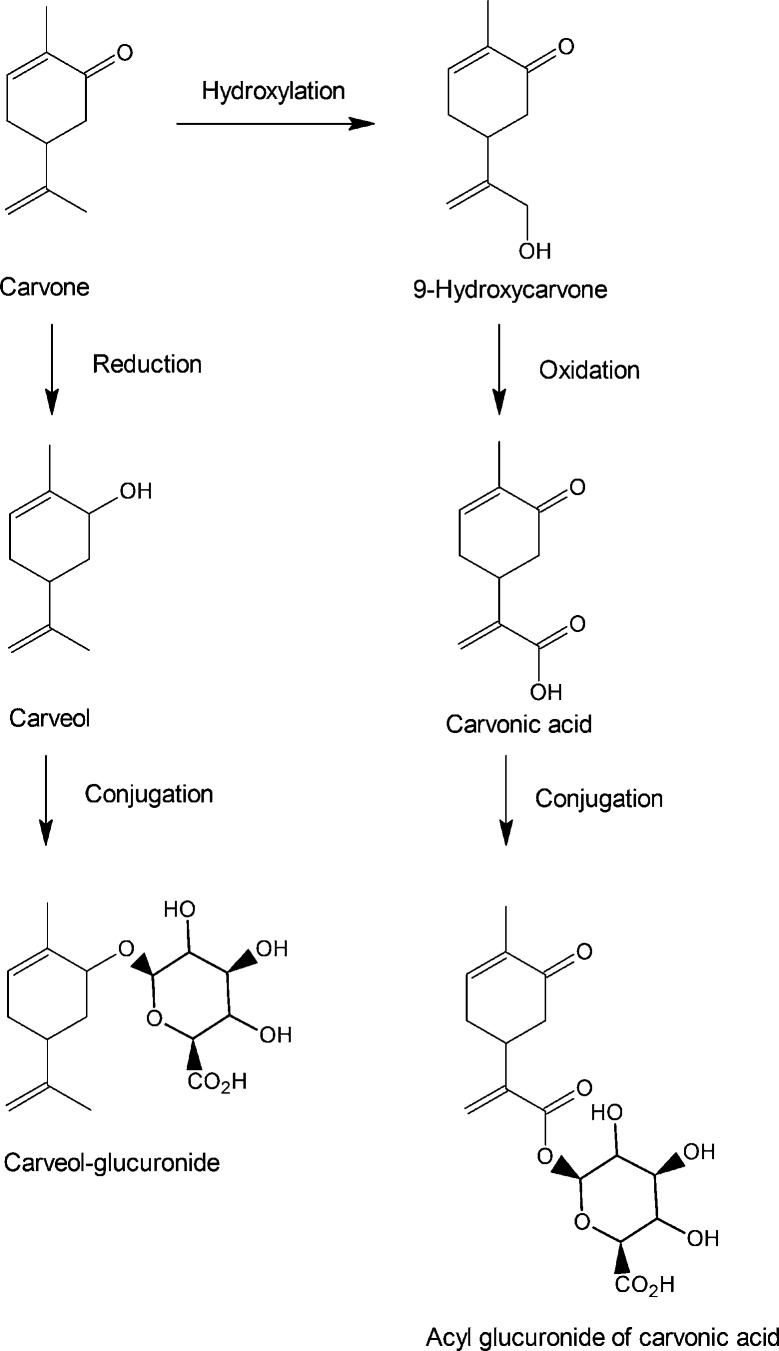

The enzymatic metabolism of xenobiotics, including flavour ingredients, has been classically termed biphasic. Originally, xenobiotic metabolism was categorically divided into Phase I and II reactions by one of the founders of the study of xenobiotic metabolism, Richard Tecwyn Williams.23 According to Williams, “Phase I” referred to reactions that may increase or decrease toxicity of a xenobiotic, and “Phase II” referred to the general trend that reactions in this category may result in detoxication of a xenobiotic. It also suggested that Phase I metabolic reactions occur first, and then Phase II reactions follow. This terminology is certainly recognized today, even in drug-interaction regulatory guidance documents,24,25 and this biphasic process can occur with flavour substances such as benzaldehyde26 and para-propylanisol,27,28 as shown in Fig. 2. However, because conjugation reactions from the Phase II category may precede a Phase I process, and there are several examples where Phase II enzymes may activate or increase the toxicity of some xenobiotics (e.g., acyl glucuronidation of carboxylic acids), the classification does not represent an inherent biochemical phenomenon. Moreover, the subsequent excretion of metabolites from the cells by various active transporter proteins is often referred to as Phase III,29 but this process can occur on the parent form of the xenobiotic even before a Phase I enzyme processes the molecule. Although this article recognizes the tremendous fundamental contributions of Williams to xenobiotic metabolism, in order to remain consistent with the realm of biological and biochemical possibilities of the biotransformation of xenobiotics,30 this article will describe individual biotransformation reactions pertaining to flavours rather than use the phase classification terminology.

Fig. 2. Example of typical oxidative metabolism and conjugation reactions using flavour ingredients.

Additionally, we indicate to the interested reader that descriptions of the metabolism of other types of chemicals, such as drugs and toxic substances, can be found in other texts which employ similar general principles,31–35 as well as information on functional group characteristics.36 For readers interested in mammalian cellular energy metabolism and metabolism as it relates to endocrinology and diseases, there is also a large array of texts and biochemistry literature available.37–40

Biotransformation reactions

There are several biotransformation reactions involved in the processing of flavour substances that produce metabolites and reactive intermediates. Predominant reactions relevant to flavours include oxidation, reduction, hydrolysis (enzymatic and non-enzymatic), and conjugation of the parent substance or resulting metabolite. Resulting metabolites from these types of reactions contain functional groups (–OH, –COOH, –NH2, or –SH) that are suitable to undergo the biochemical conjugation reactions. Conjugation reactions yield metabolites that have been modified by coupling with endogenous reactants at the aforementioned functional groups. These endogenous reactants used for conjugation include UDP glucuronic acid, acetyl CoA, glutathione, glycine, phosphoadenosyl phosphosulphate, and S-adenosylmethionine. The conjugation process may be thought of as a biological trapping reaction of a metabolite by an endogenous reactant (e.g., amino acids). As a consequence, the conjugated metabolite often has a larger molecular weight and has been effectively converted from a hydrophobic molecule into a hydrophilic one. Due to the increased polarity of conjugated metabolites, enhanced acceleration of elimination from the body results, thereby mitigating the potential for induction of toxicological effects by circulating metabolites. However, it is also to be noted that detoxication is not always the inevitable outcome of metabolism. The enzymes concerned with the metabolism of flavour substances may in some cases produce metabolites that are more toxic than the parent compound (bioactivation). This is most likely to occur within the context of oxidative metabolism but occasionally conjugated metabolites can represent a bioactivated metabolite. There are a number of biochemical and chemical mechanisms by which metabolites may be bioactivated to reactive species capable of inducing toxicities (e.g., bind to proteins, DNA, and other cellular macromolecules). A large number of literature reviews and research papers are published on this subject that pertain to a diversity of xenobiotics, highlighting mechanisms,41–43 methods of detection,44,45 pharmacological effects and prodrug design,46,47 toxicant biomarkers for regulatory science, and the role of bioactivation in chronic toxicities relevant to human safety and public health.48–50

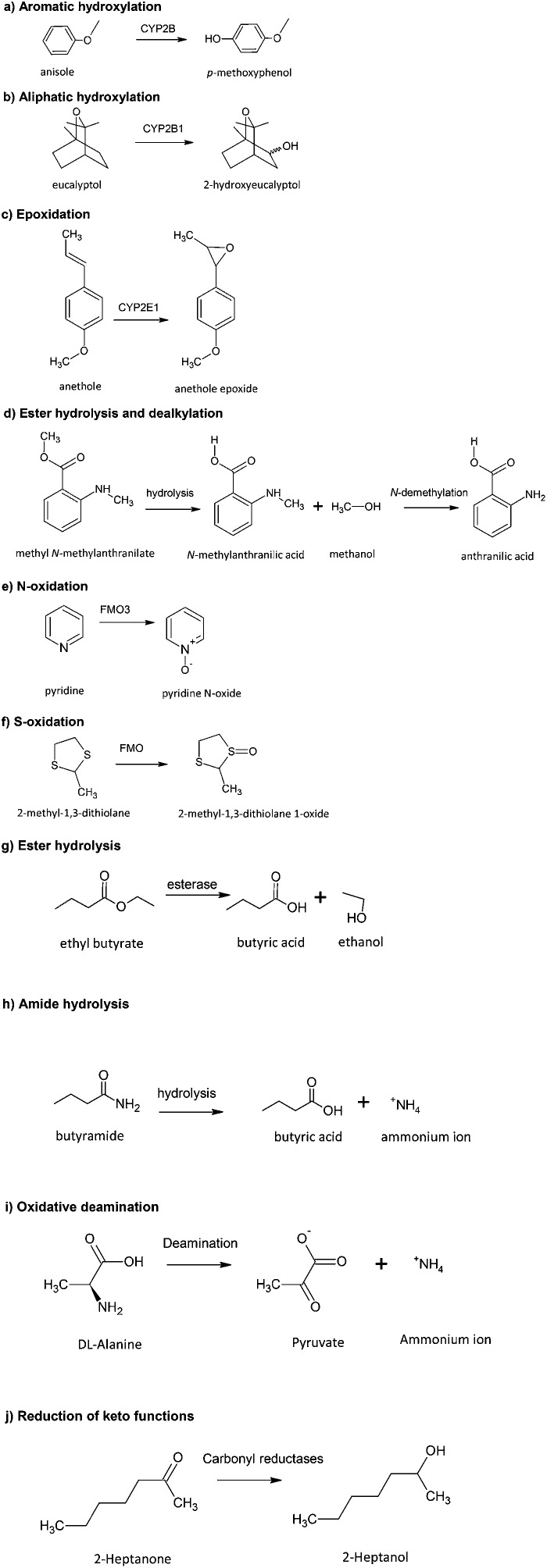

Examples of the various types of metabolic reactions are shown in Table 1 with specific examples of flavours for each pathway and related references. Fig. 3 shows examples of the structural changes associated with the different pathways. The main features of these reactions can be summarized as follows:

Table 1. Various types of metabolic pathways of flavour substances.

| Primary metabolic pathway | Example | FEMA no. | Technical function | Ref. |

| Aromatic hydroxylation | Diphenyl ether | 3667 | Imparts flavour, green | 10 and 147 |

| Aliphatic hydroxylation | d-Limonene | 2633 | Aroma and imparts flavour, green mint | 10 and 148 |

| O-Dealkylation | Estragole | 2411 | Imparts flavour, anise, liquorice | 10 and 27 |

| Oxidative deamination | Alanine | 3818 | Imparts flavour. Cooked, browned, roasted meat | 149 and 150 |

| N-Dealkylation | Methyl N-methyl-anthranilate | 2718 | Imparts flavour, floral, must | 10 and 151 |

| Epoxidation | trans-Anethole | 2086 | Imparts flavour, anise | 10 and 152 |

| N-Oxidation | Pyridine | 2966 | Imparts flavour, fishy | 153 and 154 |

| S-Oxidation | Propyl disulphide | 3228 | Imparts flavour, cooked meat, garlic, onion, pungent, sulphur | 10, 155 and 156 |

| S-Alkylation | 2-Methyl-3-(methylthio)furan | 3949 | Imparts flavour, savoury | 10, 157 and 158 |

| Reduction of ketone | 2-Heptanone | 2544 | Imparts flavour, blue cheese, fruit, green, spice cooked | 10 and 159 |

| Hydrolysis of epoxide | Ethyl methylphenylglycidate | 2444 | Imparts flavour, fruit | 10, 151 and 160 |

| Hydrolysis of esters | Ethyl butyrate | 2427 | Imparts flavour, apple, butter, cheese, pineapple, strawberry | 10 and 161 |

| Hydrolysis of acetals | Benzaldehyde dimethyl acetal | 2128 | Imparts flavour, green | 10 and 162 |

| Hydrolysis of lactones | Mint lactone | 3764 | Impart flavour, caramel and coumarin | 163 and 164 |

| Oxidation to CO2 & H2O | Octanoic acid | 2799 | Imparts flavour, cheese, fat, grass, oil | 10, 22, 165 and 166 |

Fig. 3. Examples of various types of metabolic reactions of flavouring substances.

(a) Aromatic hydroxylation: A very common reaction for flavour substances containing an aromatic ring function resulting in the generation of a phenolic metabolite. The formation of the phenol can involve the intermediate formation of an epoxide, which may have toxicological implications (Fig. 3a).

(b) Aliphatic hydroxylation: A common metabolic reaction of flavours containing an aliphatic function. Oxidation may occur at the terminal carbon (omega), omega-1, or another position (Fig. 3b). Such products may undergo further oxidation (e.g. β-oxidation) to generate carboxylic acids.

(c) Epoxidation: Oxygenation across a double bond (e.g., olefin, aryl moiety) produces an epoxide (Fig. 3c). These are normally unstable and reactive and therefore of toxicological interest. They may be converted by hydration to dihydrodiols (by epoxide hydrolase), converted to phenols, react with glutathione or link covalently to proteins and DNA.

(d) Dealkylation: This reaction can readily occur with flavour substances that contain a secondary (Fig. 3d) or tertiary amine function, an alkoxy group, or an alkyl substituted thiol function.

(e) N-Oxidation: Occurs with flavour substances that contain a trivalent nitrogen function, as with pyridine, quinolone, and tertiary amine structures (e.g. trimethylamine) to give the corresponding N-oxides (Fig. 3e). Oxidation of primary and secondary amines results in N-hydroxylation products. The formation of N-hydroxylamines presents toxicity concerns due to their activation to more reactive products following conjugation by acetylation (N-esters breakdown to nitrenium ion products), and also by N-glucuronidation, O-acetylation, and O-sulphation reactions.

(f) S-Oxidation: Found with flavour compounds containing divalent sulphur functions. Such sulphur centres may be first oxidized to sulfoxides (S O) and subsequently to sulfones (O S O) (Fig. 3f).

(g) Hydrolysis of esters: A commonly encountered reaction. Many of these compounds readily undergo hydrolysis by various esterase enzymes to the corresponding alcohol and carboxylic acid, which may themselves be further metabolized (Fig. 3g). Non-enzymatic hydrolysis under acidic or alkaline conditions and microbial hydrolysis (e.g., glycosides to aglycones) also occur in the gastrointestinal tract.

(h) Amide hydrolysis: Occurs with amide functions. Hydrolysis is normally much less extensive compared to esters and can be mediated by amidases present in plasma and the liver (Fig. 3h).

(i) Oxidative deamination: Results in corresponding amines and oxidized by-products (Fig. 3i).

(j) Reduction of keto functions: Occurs with certain flavour substances containing a ketone functional group (Fig. 3j). Reduction results in the formation of the corresponding secondary alcohol; the reduction can be stereoselective so that different ratios of the corresponding R- and S- forms are generated.

Conjugative metabolism of flavour substances

Conjugation reactions are normally important for the detoxication and subsequent excretion of flavour substances. As mentioned earlier, they involve a conjugation reaction between the flavour substance (or, more often, the metabolite resulting from oxidation, reduction, or hydrolysis) and an endogenous conjugating agent; these reactions involve a conjugation enzyme and a relevant co-factor that provides the moiety to be coupled to the metabolite.

It should be stressed that if the flavour substance contains in its molecular structure a suitable functional group for the conjugating enzyme then it may undergo directly a metabolic conjugating reaction without the intervention of another biotransformation process such as an oxidative reaction. An example is the flavour menthol which contains a hydroxyl group that can participate in a conjugation reaction with glucuronic acid to form the product menthylglucuronide, without an oxidative reaction occurring. Table 2 shows the major conjugation reactions known to occur with flavour substances. The main types of conjugation pathways can be summarized as follows:

Table 2. Metabolic conjugation reactions for flavouring substances.

| Conjugation reaction | Functional group | Enzyme |

| Glucuronidation | –OH, –COOH, –NH2, –SH | UDP-glucuronyl transferase |

| Sulphation | –OH, –NH2, –SO2NH2 | Sulfotransferases |

| Methylation | –OH, –NH2, –SH | Methyltransferases |

| Amino acid | –COOH | Butyryl-CoA (glycine and glutamine) synthetase (or ligase) and N-acyltransferase |

| –N–OH | Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase | |

| Glutathione | Epoxide, α,β-unsaturated aldehyde or ketone | Glutathione S-transferases |

| Acetylation | –NH2, –SO2NH2, –OH | N-Acetyltransferases |

(a) Glucuronidation: From the perspective of the wide spectrum of functional groups available on molecular structures that can be conjugated with a glucuronic acid, glucuronidation is important. Furthermore, the relative abundance and ease of generation of the co-factor, UDP-glucuronic acid, as well as the ubiquitous nature of the enzyme family, UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs), further highlights the importance of the glucuronidation reaction. Glucuronide metabolites are most frequently excreted in urine. Although primarily a true “detoxication” reaction, glucuronidation occasionally results in reactive forms of the conjugate, as with the acyl glucuronides of some carboxylic acids, which can react covalently with proteins. From the perspective of the safety evaluation of food flavours, glucuronidation is important particularly because of the wide spectrum of substrate functional groups for UGTs, including hydroxyl and carboxylic acid groups, primary, secondary, and tertiary amines, and thiols and sulfoxides. These functional groups are very common in the structures of flavour substances.

(b) Sulphation: An important conjugation pathway for phenolic flavour substances, as well as N–OH amines, and alcohols, amines, and thiols to a lesser extent. The reaction involves “active sulphate” in the form of 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphosulfate (PAPS) and a sulfotransferase (SULT), of which there are numerous forms with varying substrate preferences. From the point of view of flavours, sulphation is of significance for three reasons: (1) it occurs with numerous flavour compounds, particularly phenolic substances, (2) there are a large number of subfamilies, and these enzymes are widely distributed in human tissues,14 (3) it is low Vmax but also low Km and therefore can be important at low substrate concentrations, but is easily saturated by an excess of substrate, and (4) some sulphate conjugates are chemically reactive and can interact with proteins and nucleic acids with toxic sequelae. The issue of saturation becomes particularly relevant in the context of chronic administration studies using high doses, where the “normal” pathway of conjugation is exhausted and alternative pathways come into operation; this metabolic switch at a high dose may have toxicological implications that are not relevant to the low-dose intakes encountered with the use of flavouring substances.

(c) Glutathione conjugation: From the perspective of a cell-protective mechanism, this is one of the most important and recognized metabolic conjugation mechanisms in terms of toxicological relevance. Some flavour substances and other xenobiotics can be metabolized by oxidation reactions to generate new products that are reactive because of electrophilic properties (e.g., epoxides). Glutathione represents a cellular defensive mechanism to readily detoxicate electrophiles through the formation of a glutathione conjugate. Glutathione (GSH) is a tripeptide comprised of glycine, cysteine, and glutamic acid (linked to cysteine via the γ-carboxylic group instead of the usual α-carboxylic group). GSH represents an efficient and effective, endogenously-produced nucleophile that through a biochemical reaction facilitated by the enzyme family of glutathione S-transferases forms a conjugate with electrophilic functional groups on substances such as epoxides and thioethers. If a substance is electrophilic, then it may conjugate with GSH chemically, without the need for an enzyme catalysed reaction. Most flavours are not highly electrophilic, but it is possible that some metabolites of flavours are electrophilic species, and so the mammalian cell possesses a natural defence mechanism to ensure such species are short-lived and do not perturb normal cellular homeostasis. In fact, the cell retains a high concentration of a basic reservoir of GSH in the mM range that can act as a “sink” to trap potentially harmful electrophilic metabolites. The glutathione S-transferases are located in the cytosol.51 Glutathione conjugates formed in the liver are primarily excreted in the bile. In the liver and kidneys, they undergo further metabolism via the mercapturic acid pathway. This involves sequential loss of the glutamic acid and glycine by γ-glutamyltransferase and aminopeptidase M, followed by N-acetylation of the remaining cysteine conjugate to form the resulting mercapturic acids (N-acetyl-l-cysteine S-conjugate). This mercapturate metabolite is generally more water soluble than the parent substance and is more readily excreted in the urine. In the kidney, the cysteine conjugate may undergo further biotransformation by cysteine conjugate β-lyase, which removes pyruvate and ammonia from the molecule to produce a thiol metabolite. This cysteine conjugate can be oxidized to a sulfoxide or sulfone. The cellular reservoir of glutathione and its replenishment mechanism are not inexhaustible and can be overwhelmed by excess of substrate. However, this scenario is not typical for flavours that are generally used at low levels.

(d) Methylation: O-, S- and N-methylation reactions can occur at catechol functions, thiols, and secondary or tertiary nitrogen functions including heterocycles such as pyridine and quinoline. The methylation of thiols produces the methyl-substituted sulphide that can undergo subsequent S-oxidation. The reactions are catalysed by specific O-, S-, and N-methyltransferases and utilize the co-factor S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) as methyl donor. Methyltransferases are found in a variety of tissues including the liver, kidney, lung, adrenals, and pineal gland.

(e) N-Acetylation of amine functions: This is a relatively uncommon reaction for flavour materials. The acetylation reaction is catalysed by the enzyme(s) N-acetyltransferase (NAT) and involves acetyl CoA as the source of active acetate.

(f) Amino acid conjugations: These were the first metabolic conjugation reactions to have been discovered, starting with the conversion of benzoic acid to benzoyl glycine (hippuric acid) in 1842.52 These reactions involve the conjugation of a carboxylic acid with the amino group of an amino acid, forming an amide. The reactions involve the conversion of a carboxylic acid to its CoA-derivative catalysed by the enzyme acyl CoA synthetase, followed by transfer to the recipient amino acid by an N-acyltransferase enzyme. Both enzymes are associated with the mitochondrial matrix. The most commonly encountered amino acid in these reactions is glycine, but humans and other primate species utilize glutamine as the conjugating agent for phenylacetic acid and related acids. Taurine is also used. Aromatic hydroxylamines are also conjugated with amino acids, albeit to the carboxylic group of the amino acid, in a reaction catalysed by the enzyme aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase. While the amino acid conjugation to the carboxylic group of a substance is a detoxication reaction, the conjugation of amino acids to hydroxylamines is a metabolic activation reaction leading to nitrenium and carbonium products of the N-ester.

Types of metabolic information available for flavour substances

There are many sources of metabolic data for flavour substances, some being of more value and relevance than others. Metabolic data may be obtained from in vivo, in vitro, ex vivo, and in silico approaches, or the integration of in silico methods with empirical data. In silico predictions may be generated based on metabolic analogies with related compounds whose metabolism is well established. In this respect, there is a priority (hierarchy) in the source of metabolic information as used by FEXPAN in their GRAS evaluations, in the order described below:

(1) Human in vivo data generated by a comprehensive qualitative and quantitative experimental determination of the fate of the flavour substance in human subjects as determined by analyses of biological samples including urine, faeces, and plasma. If the data are comprehensive it may be possible to formulate a full “metabolic map” for the fate of the compound. Such detailed studies are resource intensive, expensive, and under some circumstances would be considered invasive. Such complete data are available for relatively few flavour agents such as anethole, methyleugenol, benzaldehyde and vanillin.27,53–56 Table 3 shows a list of flavour substances for which reasonable human metabolic data are available. The value of human metabolic data is enhanced if associated pharmacokinetic data are also available (see Table 4).

Table 3. Flavouring substances with human metabolic data.

| Substance | Ref. |

| Allyl isothiocyanate | 167–170 |

| Anethole | 53 and 171 |

| Benzoic acid | 172–177 |

| Benzyl alcohol | 178 and 179 |

| Borneol | 180 |

| Butyrolactone | 181–184 |

| Camphor | 185 and 186 |

| δ-3-Carene | 187–190 |

| (+)-Carvone | 119 |

| (–)-Carvone | 119 |

| Cinnamic acid | 191 |

| Cyclohexanone | 192 |

| Estragole | 75, 193 and 194 |

| Eucalyptol | 195–198 |

| Eugenol | 199–201 |

| Furfural | 135, 202 and 203 |

| Furaneol | 144, 204 and 205 |

| d-Limonene | 188, 206–212 |

| Menthol | 213–217 |

| Methyleugenol | 56, 76 and 218–221 |

| Methyl salicylate | 222–225 |

| Phenethyl alcohol | 226 and 227 |

| Phenol | 228–230 |

| 2-Phenoxyethanol | 231 and 232 |

| Phenylacetic acid | 104 and 233–235 |

| α-Pinene | 188, 236 and 237 |

| p-Propylanisole | 27 |

| Propylene glycol | 238–240 |

| (+)-Pulegone | 241 |

| (–)-Pulegone | 241 |

Table 4. Examples of flavouring materials with pharmacokinetic data.

| Substance | Species | Route | % Excreted in urine and/or faeces (h) | Time to Cmax (h) | Elimination t1/2 (h) | Ref. |

| Allyl isothiocyanate | Human | Oral | 44–66 (4) | <4 | 167 | |

| Allyl isothiocyanate | Rat | Oral | 73–87 (72) | 0.6 | 242 and 243 | |

| Allyl isothiocyanate | Mouse | Oral | 80 (72) | 0.25 | 242 and 243 | |

| Anethole | Human | Oral | >50 (8) | 53 | ||

| Anethole | Human | Oral | 60 (12) | 244 | ||

| Benzoic acid | Mouse | ip | 88–89(24) | 245 | ||

| Benzyl alcohol | Mouse | Oral | <0.05 | 246 | ||

| Benzyl alcohol | Rat | Oral | <0.15 | 246 | ||

| Benzyl isothiocyanate | Human | Oral | 54 (10) | 2–6 | 247 | |

| Borneol | Human | Oral | 80 (10) | 248 | ||

| Butyrolactone | Rat | iv | <0.02 | 249 | ||

| Camphor | Rat | Oral | 0.5 | 2.3 | 250 | |

| Camphor | Mouse | Oral | 0.33 | 250 | ||

| Cinnamaldehyde | Rat | Oral | 98 (24) | 251 | ||

| Cinnamic acid | Human | Oral | 0.04 | <0.33 | 252 | |

| Cyclohexane carboxylic acid | Rat | Oral | >98 (7) | 253 | ||

| p-Cymene | Rat | Oral | 60–80 (48) | 254 | ||

| Estragole | Human | Oral | 70 (48) | 27 | ||

| Ethyl maltol | Dog | Oral | 64.5 (24) | 255 | ||

| Eucalyptol | Rabbit | Oral | 0.5 | 198 | ||

| Eucalyptol | Human | Inhalation | 1.7 | 197 | ||

| Eugenol | Human | Oral | 71 (3) | <2 | 200 | |

| 97 (24) | ||||||

| Eugenol | Rat | Oral | 83 (24) | 201 | ||

| Isoeugenol | Rat | Oral | 85 (72) | 256 and 257 | ||

| Isoeugenol | Rat and mouse | Oral | 0.08 | 258 | ||

| Isoeugenol | Rat | Oral | <0.33 | 257 | ||

| Isoeugenol | Mouse | Oral | <0.33 | 257 | ||

| Isoeugenol methyl ether | Rat | Oral | 79–90 (24) | 259 | ||

| d-Limonene | Human | Inhalation | 0.05 (P1) | 208 | ||

| 0.5 (P2) | ||||||

| 12.5 (P3) | ||||||

| d-Limonene | Human | Oral | 60–90 (48) | 209 | ||

| Maltol | Dog | Oral | 57.3 (24) | 255 | ||

| 2-(4-Methoxyphenoxy) propanoate | Rat | Oral | 88–98 (24) | 0.5 | 0.24 | 260 and 261 |

| 2-(4-Methoxyphenoxy) propanoate | Human | Oral | 97 (24) | 262 | ||

| 3 l-Menthoxy-1,2-propanediol | Dog | Oral | 92 (48) | 263 | ||

| N-Methyl anthranilate | Human | Oral | 100 (24) | 264 | ||

| Methyleugenol | Rat | Oral | <0.1 | 1–2 | 56 | |

| Methyleugenol | Mouse | Oral | <0.1 | 1–2 | 56 | |

| Methyleugenol | Human | Oral | 0.25 | 1.5 | 56 | |

| Methylpyrazine | Rat | Oral | 90 (24) | 265 | ||

| Perillyl alcohol | Rat | Oral | <0.25 | <0.25 | 266 | |

| Perillyl alcohol | Dog | Oral | <0.15 | <0.15 | 267 | |

| Phenethyl isothiocyanate | Human | Oral | 3.7 | 268 | ||

| Phenethyl isothiocyanate | Rat | Oral | 88 (48) | 2.9 | 21.7 | 269 |

| 2-Phenoxyethanol | Rat | Oral | >90 (24) | 231 | ||

| 2-Phenoxyethanol | Rat | Oral | 90 (24) | 232 | ||

| 2-Phenoxyethanol | Human | Oral | 100 (24) | 231 | ||

| Phenylacetic acid | Human | Oral | 98 (24) | 104 | ||

| 4-Phenyl-3-buten-2-one | Rat | Oral | >70 (6) | <0.12 | 0.28 | 160 |

| 2-Phenylpropionic acid | Human | Oral | 95–100 (24) | <3 | 270 | |

| 2-Phenylpropionic acid | Rhesus monkey | ip | 71–82 (24) | 270 | ||

| 2-Phenylpropionic acid | Rat | ip | 71–82 (24) | 3.8 | 271 | |

| α-Pinene | Human | Inhalation | 0.08 (P1) | 236 | ||

| 1 (P2) | ||||||

| 10 (P3) | ||||||

| p-Propylanisole | Human | Oral | 67 (8) | 27 |

(2) Animal in vivo metabolism: These are the most commonly encountered metabolic data for flavour substances and are obtained from laboratory studies on species such as rats, mice, and occasionally dogs. Such data can be particularly informative if gathered in the species that has been used for subchronic and chronic toxicity testing. Care has to be taken in the evaluation of such data because of the occurrence of species differences in metabolism, both in terms of rates and metabolic pathways. If there are species differences in metabolic pathways for a given substance, then extrapolation from animal to humans becomes a major limitation. Some of these differences are minimized in studies conducted in what are called “humanized” animal metabolic models, which carry one or more expressed specific human genes in the genome of the animal, usually a mouse or rat as these are common in vivo models in experimental toxicology and metabolism studies.57,58 Because mouse embryonic stem (ES) cell culture is well established, traditionally, mice have been used to create humanized animal models to study human metabolism. Briefly, the mouse gene is replaced by the human gene; the introduced human gene becomes part of the mouse genome and is expressed to produce the human enzyme. In genetic parlance, the mouse gene is knocked out and the human gene is knocked in. The technique relies on homologous recombination between a genetic construct introduced in the ES cell (through transfection) and the target genetic locus in the mouse genome. Homologous recombination introduces the human gene from the introduced genetic construct into the mouse genome, thereby replacing the mouse gene sequence. With the improvement of the knockout/knockin technology, the number of steps involved to accomplish this has been simplified and reduced. This technique usually replaces one allele out of two, thereby creating a heterozygous genotype. Two such heterozygous parents are bred to obtain the homozygous animals. Sometimes, homozygosity could become lethal for the animals. If no such limitations exist, homozygous animals are used to study metabolism. The human protein expression in mouse cells under physiological conditions is ensured by using mouse promoter and regulatory sequences. The expression of the human protein can be further controlled by using either a constitutive promoter or a tissue-specific promoter. The use of a constitutive promoter results in the expression of the human protein in all mouse tissues, whereas the use of a tissue-specific promoter restricts the expression in specific tissue where the promoter is active.

Historically, mice have been the predominant species for generating a transgenic animal model because rat ES cell culture was not successful. However, stable rat ES cells have become available,59 and as the technology develops, the rat will present as a more common “humanized” animal model. There are several reviews on this topic, which are helpful for understanding the technology as it pertains to toxicology and its role for improving our understanding of specific enzymes, transporters, and receptors regulating metabolism.60–65 With the advent of direct genome editing technology, obtaining humanized rat models easily has become a reality. Because the rat is the most widely used animal model for studies submitted to regulatory agencies, it is expected that the generation of humanized rat models for metabolism studies will soon take off.

For metabolic studies, useful targets for humanization into rodents are the cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes CYP2A6, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, and CYP3A4 because these enzymes are found in the human liver but are absent in mouse and rat liver.66 As the liver plays a central role in xenobiotic metabolism,61 generating these enzymes in animal models can be a powerful tool, although there are limitations.65 It is important to note that other enzymes involved in xenobiotic metabolism of flavours, such as the human UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1 (UGT1A), human arylamine N-acetyltransferase 2 (NAT2), and human sulfotransferases 1A1 (SULT1A1) and 1A2 (SULT1A2), have been successfully expressed in specific organs of mice to enable examination of their molecular regulation and function.16,67–69 Mouse models that neither express the mouse or human protein are also available and are termed as global “knockouts”. This approach enables analysis of the role of a particular enzyme in pathophysiological events. In addition, genetic knockouts can serve as a control for a humanized model to assess relevance of a given gene product in the disposition and toxicity of a substance. Examples of global knockouts that have been generated for enzymes relevant to the metabolism of flavours include knockouts for alcohol dehydrogenase, aldehyde dehydrogenase, CYP2E1, and CYP3A.70–73 There are other relevant knockout mouse models for enzymes metabolizing flavours but to present a full overview is beyond the scope of this paper. The important point with these in vivo technologies is that if marked species differences are anticipated to occur between rodents and humans in the metabolism of xenobiotics, then the humanized animal models of xenobiotic metabolism can be utilized to help overcome the challenge of building a more predictive model of the human response to xenobiotics.

(3) In vitro approaches: These provide alternatives to the use of human or animal in vivo approaches and act as models to understand in vivo metabolism. There are various in vitro approaches possible. Among the most common are the use of homogenates of specific tissues (e.g. liver or kidney) and tissue microsomal preparations. In some situations, the use of specific cloned forms of the drug-metabolizing enzymes provides an assessment on the role of specific enzymes in the metabolism of a substance. Microsomal preparations from humanized animal models as described above provide the additional advantage of using human P450 and other highly relevant enzymes as powerful tools for providing a more detailed and mechanistic understanding of human specific biotransformation pathways. Another advantage with in vitro approaches is the ease in controlling experimental conditions. Approaches of these types can yield valuable information concerning the specific metabolic pathways for a flavour substance, the functional groups that are centres of metabolism and the nature and extent of any conjugation reactions. Such studies can never adequately replace appropriate in vivo investigations as they cannot reflect, inter alia, contributions of extrahepatic sites of metabolism or the possible contribution of the gut flora, absorption, distribution, excretion, and dose. Ultimately, these approaches can provide a guide or forecast of what could occur in vivo but cannot be regarded as definitive. The main disadvantage of in vitro approaches is that there can be high variation between models such that extrapolation to the in vivo human response based on non-clinical in vitro tests can be difficult.

(4) In silico approaches include human knowledge-based and computational metabolic prediction systems: A number of in silico approaches are available and the field has grown tremendously in recent years. A non-exclusive list includes human knowledge-based systems such as Meteor Nexus¶ , Metasite‖ , ADMET** , META† , and computationally driven systems, such as SMARTCyp‡ , MetaPrint 2D§ , MetaDrug¶ , Simcyp‖ , and others, have been developed for the purpose of predicting the metabolic fate and pharmacokinetic profiles of organic compounds in mammalian systems. These approaches utilize currently available metabolic data for a large number of substances as a basis set upon which the prediction of the metabolic fate of a compound is made. Using such in silico prediction models, it is of importance to keep in mind that metabolic fate prediction can be confounded by many factors, including animal species, genetic factors (polymorphisms), route of administration, non-enzymatic reactions (e.g., hydrolysis in the stomach), and dose, among others. Of heightened interest is the application of physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK), in silico modelling towards assessing the absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion (ADME) processes and their underlying biological and physiological drivers.74 Solution of PBPK models generates outcomes that indicate, for example, the tissue concentration of a compound or its metabolite over time at any dose. PBPK models have been developed to predict plasma concentrations of dietary constituents and their metabolites in human subjects.75–79 Such models are informed with in vitro metabolic parameters, which underscores the value of in vitro metabolism studies. The integration of in vitro metabolic data in PBPK models to predict dose- and species-dependent in vivo effects of flavouring substances such as estragole and coumarin has been conducted to learn of the possible implications and relevance of bioactivated metabolites of flavours to humans.80,81 Computerized prediction of biotransformation behaviour can be a useful guide to experimental design and as decision-support to better understand the contribution of metabolites to biological effects in humans, but it cannot replace data obtained by in vivo investigations. Consequently, expert judgment and expertise is critical in assessing the output of these in silico predictions for mammalian systems.

Factors affecting the metabolism of flavour substances

Although the great majority of flavour substances will undergo metabolic change in the body, and this is crucial to assessing the potential for toxicity, the nature and extent of metabolism can be influenced and determined by a variety of endogenous and exogenous factors. Endogenous factors include genetic variability, physiological and pathophysiological conditions, while exogenous factors include enzyme inducers, enzyme inhibitors, and diet.

Distinct genetic based differences in enzyme expression and activity are well known especially for the human CYP enzymes, which are responsible for a large portion of the xenobiotic transformation reactions.18 Variants in enzymatic activity are notable for CYP2C9, CYP2C19, and CYP2D6, but many are also described for enzymes involved in important conjugation reactions including UDP-glucuronosyltransferases and N-acetyltransferase enzymes.19 Of relevance to food science, dietary carcinogens (heterocyclic aromatic amines) are conjugated by N-acetyltransferase enzyme 1 (NAT1) and N-acetyltransferase enzyme 2 (NAT2).82 Human NAT1 and NAT2 genes encode these enzymes that are highly polymorphic, leading to phenotype variants with interindividual differences in enzyme activities and inducibility.83 These differences in enzyme activities can alter bioactivation and detoxication efficiency, which has been studied as a factor in influencing cancer risk between individuals and population groups.82,84,85 It is now possible to phenotype the activity of many metabolizing enzymes in humans using drugs as probes. Likewise, it is possible to evaluate genotypes, although genotype alone does not always predict phenotype. In addition to genetics as an endogenous factor, metabolism of xenobiotics can be subject to physiological conditions such as co-factor supply,86 and an array of pathophysiological conditions that may modulate metabolizing enzyme activity of which some of the better characterized are chronic liver disease states such as cirrhosis and inflammation.87–90 Also, age-associated changes in expression of xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes have been reported in rodents.91 However, how all these changes affect flavour metabolism is not known and their clinical relevance is also still under investigation.

Exogenous factors affecting the metabolism of xenobiotics include exposure to substances that inhibit and induce the protein expression and enzymatic activity of metabolizing enzymes. Whether inhibition of the enzyme is clinically important depends upon the kinetics of the specific enzymes of interest as well as the concentration of the inhibitor in the vicinity of the enzyme. There are a plethora of reviews in the field of modulation of enzyme expression and activity and the critical role receptors play as xenobiotic sensors regulating expression, and to give a full overview is beyond the scope of this article.19,92–94 However, it is well-known that pharmaceuticals, environmental contaminants, and dietary constituents can contribute to modulating expression and the regulatory factors involved.90,95

For flavour substances, the most important factors determining the metabolic profile detected in an experimental setup are the selection of animal species, exposure level (dose), acute as opposed to chronic dosing, genetic variability, and sometimes minor structural changes in the flavour molecule itself. Since evaluating the potential toxicity of flavour substances is often reliant to understanding metabolism, and because the toxicology of such substances is usually determined in animal laboratory species, it is important to understand the metabolic patterns in test animals and how these relate to humans in order to decide whether these data are relevant to human safety.

Species differences in the metabolism of flavour substances

Animal species may differ in the way they metabolize flavour substances in two respects, namely, the pathways of metabolism utilized and the rates of biotransformation. This is not entirely surprising in view of the different genetic backgrounds and environmental factors that help determine metabolic capabilities. Although there may be a common generality in the pattern of metabolism between the species, quite marked species differences can emerge in terms of metabolic pathways utilized. If this is the case, it follows that animal test species used for example in 30- or 90-day safety studies of a flavour substance could be exposed to an array of metabolites different from that seen in humans. This is particularly important when considering metabolite contribution in the overall toxicity assessment. However, the occurrence of a metabolite only in humans and not in any animal test species is relatively uncommon.96 These are termed “human-specific metabolites” by the FDA and in the case of drugs there is World Harmonization guidance for assessing toxicity of them when the fraction exceeds 10% of total (human) metabolites. Moreover, some studies have reported significant differences in catalytic activities between animal species (rat, mouse, dog, monkey) with respect to major enzymes such as the CYPs.97 Such information can enable appropriate selection of a non-clinical model species for metabolic studies. Nonetheless, if a metabolite is formed in humans and not in animals, the advent of in vitro human liver microsome studies can help allay concern to identify potential qualitative and/or quantitative differences so that species-species extrapolation in metabolic profiles between humans and animals is attainable. A few examples of species differences in metabolic reactions will be used to illustrate these points.

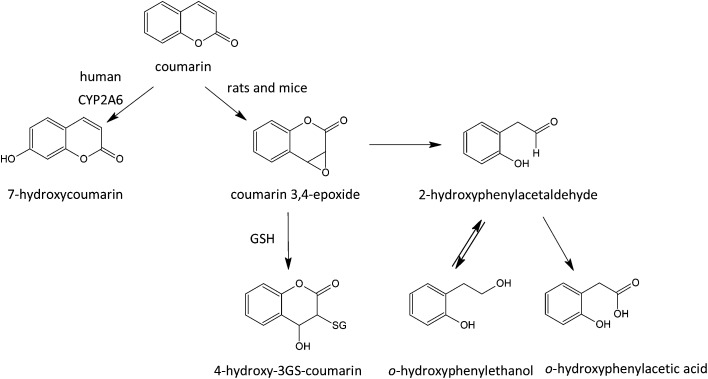

Hydroxylation, a very common metabolic pathway, can exhibit marked species variation. A primary driver is interspecies variations in catalytic activity of CYP enzymes.98 The CYP1A2 enzyme is well known for this. In the case of aromatic hydroxylation, some species (rat, mice, rabbit, Guinea pig) can favour hydroxylation in a vacant para-position while others (dog, cat) can favour ortho-hydroxylation.99 In the rat, coumarin is metabolized by epoxidation followed by ring opening to an aromatic aldehyde metabolite, which is considered to be responsible for the hepatotoxicity and hepatocarcinogenicity of the compound in this species.100 In humans, hydroxylation to 7-hydroxycoumarin is the favoured route,100,101 while in the rat this pathway is of minimal importance. In addition, species differences can occur with respect to the major conjugation reactions, as exemplified by reference to the metabolism of two simple flavour compounds, phenol and phenylacetic acid.102 Humans metabolize phenol by conjugation with glucuronic acid and sulphate, whereas the cat utilizes sulphate exclusively and the pig just glucuronic acid.103 In most laboratory species phenylacetic acid is conjugated with glycine (and to a lesser extent, taurine) but in humans it is conjugated with glutamine.104 There are other commonly recognized species peculiarities; for instance the dog is unable to N-acetylate aromatic amine functions,105 and the Guinea pig is unable to N-acetylate arylcysteine conjugates to mercapturic acids.53 There are also metabolic reactions that seem to be specific to certain species; the glutamine conjugation of phenylacetic acid derivatives appears to be the preserve of humans, New and Old World primate species,104 and the remarkable conversion to benzoic acid of the dietary chemical quinic acid appears specific to humans.106 Thus, in the evaluation of the safety of a flavour substance from studies in laboratory species, it is relevant that the metabolic profile should be reasonably similar to that in the human situation, or that metabolic differences are reviewed by experts in metabolism and considered for their toxicological relevance.

Dose-dependent metabolism: metabolic overload and metabolic switching

Excess exposure to a flavour substance can, inter alia, result in the saturation of one or more of the pathways involved in its metabolism. Such a situation is not uncommon and it is indeed seen with some of the high dose levels employed in subchronic and chronic safety studies in animal species. Such a saturation can arise for two reasons; firstly, the metabolic enzyme involved may be saturated by excess of substrate; and secondly, due to depletion and relative lack of any appropriate co-factors. Examples of the first include saturation by excess substrate of the various cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in the oxidative metabolism of flavour substances, such as those with low catalytic rates or subject to metabolic inactivation. With respect to depletion (exhaustion) of co-factors, this can occur with the sulphate and amino acid conjugation mechanisms, which are dependent upon restricted supplies of co-factors; in the case of sulphate, this involves availability of its active form, 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphosulphate (PAPS) and, in the case of the glycine conjugation, availability of the amino acid itself can be a limiting factor. This can become evident by the utilization of alternate pathways of metabolism, or switching to a novel route or another tissue. For obvious reasons this phenomenon is known as “dose-dependent metabolism” or “metabolic switching” and in these cases the results of such studies may be misleading or irrelevant to humans at low dose levels.

Dose-dependent metabolism is generally not a problem in the context of human exposure to flavour substances because of the generally low levels of use of these chemicals, but it can be a major issue with respect to the design, employment, and interpretation of the results of animal safety studies and investigations in vitro. This problem can be illustrated by consideration of the metabolism and toxicity of the flavour substance cinnamyl anthranilate. Chronic dosing with high levels of this substance can induce peroxisome proliferation via interaction with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα activator) and lead to liver tumours in mice and rats, pancreatic acinar cell, and Leydig cell tumours in rats, all in a dose-dependent manner.107 The neoplastic and non-neoplastic lesions seen with cinnamyl anthranilate appear to be associated with peroxisome proliferation (PPARα activation). Metabolic studies with cinnamyl anthranilate show that its biotransformation is dose-dependent.108 Low dose levels are, as would be expected, initially hydrolysed to the constituent alcohol and acid, namely cinnamyl alcohol and anthranilic acid, presumably by esterase activity. However, at high doses, because of saturation of the esterases, the intact ester becomes systemically available and this intact molecule is responsible for peroxisome proliferation (PPARα activation) and subsequent events. As far as the human situation is concerned, these animal toxicity findings at high doses would seem of little relevance on the basis that the low levels used in food would be hydrolysed, and the intact ester would never become bioavailable as such. Furthermore, there are major differences in the proliferative response to PPARα activation in rodents and humans.109,110

A further aspect of high dose chronic studies of flavour substances in laboratory animals which has received little attention is the question of enzyme induction, as to how this may alter the pattern of metabolism seen in the acute dose state compared to that following chronic administration. As outlined in the previous section, many of the enzymes involved in the metabolism of flavour agents can, at least on theoretical grounds, be induced by chronic exposure to a particular chemical. Thus, many chemicals can induce one or more of the various cytochrome P450 enzymes including CYP1A1, CYP2B, CYP2C, CYP3A, and CYP4A as well as the UGT enzymes. Examples of known inducers include ethanol, isosafrole, safrole, butylated hydroxyanisole, and butylated hydroxytoluene.111,112

Pharmacokinetics/toxicokinetics of flavour substances

Pharmacokinetics (toxicokinetics) can be described as the mathematical description of the time course of disposition (absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion) of a chemical in the body. For flavours, it describes, among other things, their longevity or period of residence in the body. For flavour substances, it is clearly highly desirable that, once having performed their technical function of imparting flavour, they should be rapidly cleared from the body in an innocuous form. There are important pharmacokinetic parameters, namely, plasma half-life (t1/2; the time required for the plasma concentration of a flavour substance to reach half of its initial peak plasma concentration; in minutes or hours), the clearance (the volume of plasma that is cleared of the substance per unit of time; mL per minute), and volume of distribution (the estimated apparent space in which the substance is distributed so that it results in a given plasma concentration; L per kg bw) that can be used to interpret the significance of exposure to these chemicals. These parameters can be determined for animals and humans from appropriate quantitative measurements on plasma and urine of a parent flavour substance and its metabolites on a time basis. In general, it is expected that most flavour agents, based on their chemical structures (e.g., esters), would be characterized following absorption by short plasma half-lives, low volumes of distribution, and rapid elimination times. Some examples of pharmacokinetic parameters determined for flavours in humans and laboratory species are shown in Table 4. Such data are not available for the majority of flavour substances, even in cases where some information about the metabolic products is available. It can be concluded that the majority of flavouring substances reach their maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) rapidly (<1 h) following absorption, have relatively short elimination half-lives (hours), and the majority of metabolites are excreted mainly into the urine and faeces within 24 hours. Because human pharmacokinetic data are not commonly available for flavour substances, a modern and well-accepted method of assessing kinetic parameters is to perform physiological-based pharmacokinetic modelling (PBPK).76,80,81 When validated for the oral route of administration in the rat, PBPK models can enable defining human pharmacokinetics of a substance by inputting human values based on literature data and in vitro studies into the model, without the need for human experiments.

Enzymes involved in the oxidative metabolism of flavour substances

Various enzymes that can be involved in the metabolic oxidation, reduction, or hydrolysis reactions of flavour substances are shown in Table 5. The great majority of flavour substances will undergo one or more of these reactions during the course of their biotransformation. Numerous diverse enzyme systems can be involved and the most important of these, in the context of flavour substance metabolism, are the CYP enzymes. However, the flavin-containing monooxygenases (FMOs), the alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenases (ADH and ALDH, respectively), and xanthine oxidoreductases (XOR) are also noteworthy.

Table 5. Enzymes involved in oxidative, reductive, and hydrolysis reactions of flavour substances.

| Reaction type | Enzyme |

| Oxidation | Cytochrome P450 enzymes (microsomal mixed function oxidases) |

| Flavin-containing monooxygenases | |

| Alcohol dehydrogenase | |

| Aldehyde dehydrogenase | |

| Aldehyde oxidase | |

| Amine oxidases | |

| Xanthine oxidoreductase | |

| Reduction | Cytochrome P450 |

| NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase | |

| Hydrolysis | Various esterases |

The cytochrome P450 system

The cytochrome P450 (CYP) system is located in the endoplasmic reticulum of many cells found principally in the liver, intestines, lungs, and kidneys, and at somewhat lower levels in other tissues.43 The oxidation mechanism requires the complete mixed function oxidase system (i.e., cytochrome P450, NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase, NADPH, cytochrome b5 (in some cases), and a lipid bilayer) and involves the insertion of a single atom of oxygen into the flavour molecule, or an equivalent reaction. This metabolite may be the final product or, depending on the structure of this initial oxidation product, may undergo a rearrangement or decomposition. There are numerous CYP enzymes derived from different gene families and sub-families. The situation is highly complex; to date, 57 discrete CYP genes have been identified in humans.112,113 Many of the gene products (P450s) are involved in the metabolism of endogenous substances such as steroids, fat-soluble vitamins, and fatty acids. A recent calculation showed that of xenobiotics including general chemicals, natural and physiological compounds, and drugs, >90% of enzymatic oxidation–reduction reactions are catalysed by the CYP enzymes.18 However, an important cluster of CYPs appear to be mainly involved in the metabolism of xenobiotic substances, including many food flavour substances, and these include cytochromes CYP1A1, CYP1A2, CYP2A6, CYP2C8/9/18/19, CYP3A4/5/7, CYP2B, CYP2D6, and CYP2E1. Similar, but not identical CYPs are found in other mammals such as the mouse, rat, and dog, species used in conventional acute, subchronic, and chronic safety studies of flavour substances. There are a number of general features of the CYP system that need to be outlined. Firstly, the tissue levels of expressed forms of CYPs can vary quite dramatically between different individuals and this can determine marked interindividual variations in the oxidative metabolism of various substrates. The reasons for this variation are not always entirely clear; it can, in part, be a heritable trait, but other factors include variants, hormonal influences, diet, and the inducing effect of other chemicals. Several of the human CYPs (e.g., CYP3A4, CYP2C9, CYP2C19) can be induced by exposure to a variety of chemicals and in some instances by exposure to the substrate itself. This feature of “enzyme induction” and its consequences merit consideration in the context of the evaluation of the outcomes of chronic and subchronic safety studies on flavour materials, where sustained exposure induces the CYP enzymes resulting in a change in metabolism from that seen in acute dosing. A further feature of the CYPs is that some exhibit genetic polymorphism in the human population; examples of this include CYP2D6, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, and CYP2E1.114 The existence of polymorphic variants can determine the occurrence of different human phenotypes with respect to their ability to metabolize xenobiotics. The so-called Extensive (EM) and Poor Metabolizer (PM) phenotypes are an example. These phenotypic differences are known to be particularly important in the context of the responses to and use of certain drugs, as they can be associated with adverse reactions and modified therapeutic responses. The extent to which such polymorphic differences would be important in the metabolism of food flavours in humans is a rather unstudied area. However, recent studies have revealed that adequate predictions on interindividual human variation can be made with Monte Carlo-based PBPK modelling using simulations on the formation of metabolites from the flavours estragole and methyleugenol.75,76

Flavin-containing monooxygenases (FMOs)

This enzyme system is important for the oxygenation of numerous nucleophilic organic nitrogen and sulphur containing substances.115 FMOs are a multi-gene family encoding different flavin-containing monooxygenase enzymes and these have been characterized into eight subgroups (FMO A–H), with each FMO form having different substrate preferences.116,117 FMOs are distinct from CYP enzymes in terms of mechanism and substrates. FMOs oxidize highly nucleophilic substrates via a two-electron mechanism, whilst CYPs accept considerably less nucleophilic substances and oxidize via sequential one-electron processes.86 The FMOs use either NADH or NADPH as a source of reducing equivalents. They are particularly abundant in the liver but are also found in other tissues, including kidney and lung. One of the FMOs, namely FMOB (formerly referred to as FMO3) exhibits genetic polymorphism and this is clearly seen in the different human abilities to metabolize (N-oxygenate) the flavouring substance trimethylamine (FEMA 3241). Most individuals convert trimethylamine, with its typical “fish-like” odour, to its non-odorous N-oxide through the activity of FMOB. However, a few individuals with an inherited defective form of FMOB are unable to oxidize the malodorous trimethylamine and they excrete unusual amounts of the free amine in their urine, expired air, and sweat. This results in the unfortunate clinical picture of “Fish Malodour Syndrome”, in which affected individuals acquire the disagreeable and unpleasant odour of rotting fish. A similar situation can arise for non-genetic reasons in individuals with excess exposure to the food constituent and flavour choline. Excess choline is converted by the gut bacteria to trimethylamine, which is absorbed and the amounts gaining access to the systemic circulation exceed the metabolic capacity of FMOB and the non-oxidized excess results in a “fish-malodour” type syndrome.

FEXPAN procedure for the evaluation of metabolism data in the context of the safety assessment of flavour substances

Safety evaluations are performed on a “weight of evidence” approach relying on expert judgment to integrate all relevant data on a substance and structurally related substances. As indicated above, metabolic data are essential criteria that are taken into account by the Panel when assessing the potential GRAS status of food flavours. Based on the structure and on predicted or known metabolism of the substance, the Panel develops a metabolic map for the fate of the substance in humans and other animals. The essential question is whether or not the flavour candidate is either known to be, or judged to be by reference to analogous structures, able to undergo effective and safe metabolic clearance following absorption. The approach taken to answer this question is essentially hierarchical and sequential, and uses all metabolic information that is available, i.e. in vivo, in vitro, ex vivo.

For instance, a highly informative situation is when human metabolic data are available and a full “metabolic map” detailing the biotransformation of the flavouring substance can be constructed and major metabolic pathways have been unequivocally established. An even more optimal situation is where, in addition to the human metabolic data, metabolic data are also available for the species used in subchronic or chronic toxicity studies enabling a species comparison of metabolic disposition and evaluation of the adequateness of the animal model. Such desirable comprehensive studies, however, as pointed out before, are technically demanding and expensive and can be viewed as invasive, and are thus not often available. Alternatively, in vitro metabolic data are usually the main type of metabolism evidence available for food flavour agents. However, there are limitations to the value of such in vitro studies as they may not necessarily reflect what is happening in the much more complex whole body situation. For example, in vitro data cannot account for all possible metabolic transformations that occur in the gastrointestinal environment by microflora, whereby the products formed are different to the parent compound. The results of such studies should be regarded as a forecast. However, if the chemical structure bears functional groups with potential to hydrolyse (e.g., amides) then study to investigate the potential and rate of hydrolysis of the flavour substance is very useful.

For the approximately 2700 FEMA GRAS substances, specific metabolic information (in vivo, in vitro, and both) is available for about 25% of these materials. When such data is lacking, the first course of action is to assess whether or not the flavour substance belongs to one of the flavour structural groups (i.e., Congeneric Groups), as shown in Table 6. A second approach is to determine whether or not there exists adequate metabolic information to support that particular Congeneric Group as a whole. Thus, for simple aliphatic esters, such as amyl acetate and ethyl butyrate, there is an abundance of evidence that such esters undergo rapid metabolic hydrolysis to their corresponding alcohol and carboxylic acid. In addition, perusal of functional groups present in the flavour molecule can permit reasonable forecasts of the metabolic options available, i.e. oxidation, reduction, hydrolysis, and various conjugation reactions.

Table 6. Principal metabolic pathways for typical chemical groups relevant to flavouring substances.

| Chemical group | Main metabolic pathways |

| Aliphatic Allyl Esters | Hydrolysis, oxidation to acrolein, conjugation with glutathione, oxidation of corresponding alcohol to the aldehyde and later to carboxylic acid, and excretion as mercapturic acid conjugate |

| Saturated Aliphatic, Acyclic, Linear Primary Alcohols, Aldehydes, Carboxylic Acids and Related Esters | Hydrolysis of esters and acetals; resulting oxygenated functional group undergoes oxidation followed by β-oxidation to form CO2 and H2O in the fatty acid pathway and tricarboxylic acid cycle |

| Saturated Aliphatic, Acyclic, Branched-chain Primary Alcohols, Aldehydes, Carboxylic Acids and Related Esters | Hydrolysis of esters and acetals to yield oxygenated function group that undergoes complete metabolism to CO2 and H2O, ω-oxidation to yield additional oxygenated functional group, conjugation and excretion/hydrolysis & oxidation of oxygenated functional group |

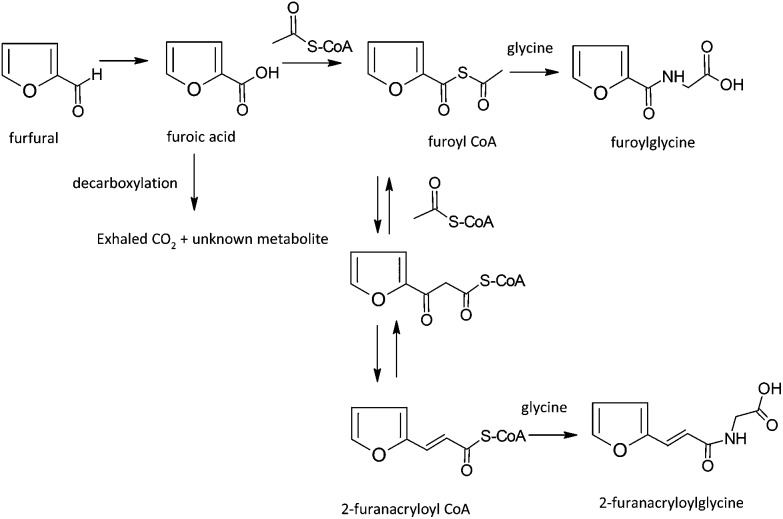

| Furfural and derivatives | Hydrolysis of esters and acetals, oxidation of resulting alcohol or aldehyde to furoic acid followed by conjugation with glycine. Condensation with acetyl CoA can produce a furfurylacrylic acid metabolite |

| Saturated and Unsaturated Aliphatic Acyclic Secondary Alcohols, Ketones and Related Esters | Hydrolysis of esters or ketals, conjugation of resulting alcohols with glucuronic acid, reduction of alicyclic ketones to yield alcohols followed by conjugation and excretion. Alpha-oxidation if a penultimate ketone is present |

| Linear and Branched-chain Aliphatic, Unsaturated, Unconjugated Alcohols, Aldehydes, Carboxylic Acids and Related Esters | Hydrolysis and β-oxidation to form CO2 and H2O in the fatty acid pathway and tricarboxylic acid cycle/ω-oxidation to yield diacid-type metabolites |

| Aliphatic and Aromatic Tertiary Alcohols and Related Esters | Conjugation with glucuronic acid and excretion and additional hydroxylation of substituents to yield polar poly-oxygenated metabolites |

| Aliphatic Acyclic and Alicyclic α-Diketones and Related α-Hydroxyketones | Reduction to yield diol followed by conjugation and excretion, conjugation of the hydroxyl ketone followed by excretion |

| Aliphatic and Aromatic Sulphides and Thiols | Sulfides are dealkylated to the corresponding thiols, which may be oxidized and undergo desulfurization. Sulfides may form mixed disulphides with available sulfhydryl groups such as glutathione. Thiols may be methylated and then oxidized to the corresponding sulfoxide or sulfone followed by excretion |

| Aliphatic Primary Alcohols, Aldehydes, Carboxylic Acids, Acetals and Esters Containing Additional Oxygenated Functional Groups | Hydrolysis of esters and acetals, followed by oxidation of the corresponding acid and complete metabolism in fatty acid pathways and tricarboxylic acid cycle |

| Cinnamyl Alcohol, Cinnamaldehyde, Cinnamic Acid, and Related Esters | Hydrolysis of ester or acetal to yield corresponding alcohol or aldehyde that is further oxidized to the acid followed by β-oxidation and cleavage to yield a hippuric acid derivative |

| Furfuryl Alcohol and Related Substances | Hydrolysis of esters and acetals, oxidation of resulting alcohol or aldehyde to furoic acid followed by conjugation with glycine. Condensation with acetyl CoA may produce a furfurylacrylic acid metabolite |

| Phenol and Phenol Derivatives | Conjugation with glucuronic acid or sulphate followed by excretion |