Abstract

The Fourier transform (FT), a cornerstone of optical processing, enables rapid evaluation of fundamental mathematical operations, such as derivatives and integrals. Conventionally, a converging lens performs an optical FT in free space when light passes through it. The speed of the transformation is limited by the thickness and the focal length of the lens. By using the wave nature of surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs), here we demonstrate that the FT can be implemented in a planar configuration with a minimal propagation distance of around 10 μm, resulting in an increase of speed by four to five orders of magnitude. The photonic FT was tested by synthesizing intricate SPP waves with their Fourier components. The reduced dimensionality in the minuscule device allows the future development of an ultrafast on-chip photonic information processing platform for large-scale optical computing.

Keywords: diffraction, Fourier optics, optical computing, optical information processing, surface plasmon polaritons

Introduction

Fourier analysis is the process of decomposing a general function into the sum of a set of simpler periodic functions, which corresponds to the mathematical operation of a Fourier transform (FT). It gives rise to many fundamental principles in physics, engineering, and mathematics1. For instance, spectroscopic measurement of the spectrum (FT of the waveform in the time domain) of white light shows the energy distribution over the constituent electromagnetic waves of different frequencies. As for a monochromatic electromagnetic waveform, the FT of the spatial distribution of the field gives the angular spectrum, where each point in the spectrum represents a constituent planewave propagating in a specific direction2,3. On the other hand, Fourier synthesis, the process opposite to Fourier analysis, reconstructs a function from its spectrum using the inverse FT (IFT). Differentiated only by a parity operator, the IFT and FT can, in practice, be implemented using the same physical process. In optics, it is remarkably simple that a single converging lens performs the complicated FT/IFT at the speed of light, such that the complex amplitudes in the front and back focal planes become an FT pair (with some additional scaling factors) 4. This lays the foundation for most experimental works in the area of Fourier optics5,6, enabling the analysis of the angular spectrum of light and the synthesis of light in the reverse process. The optical FT carried out by a lens also forms a basis of optical computing7,8 due to its parallelism and unrivalled speed, which is ultimately limited by the size of the optical system. Recently, planar structures have been shown to be able to perform mathematical operations as light passes through, providing a possibility to replace conventional lens-based optical systems, but the fundamental principle is still based on free-space optics9. In fact, the physical footprint of such optical information processing systems could be reduced substantially if these operations could be carried out solely in a two-dimensional (2D) space rather than in free-space. Plasmonic nanostructures offer a rare opportunity to manipulate light at the deep subwavelength scale, which has been demonstrated as a route to substantially reduce the size of many photonic devices10,11,12,13,14 including basic optics, such as waveplates15,16,17, phase plates18,19, and color filters20,21,22. Here, we report that the complex operation of an FT can be performed in a single 2D plane via surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs)—a propagating surface wave strongly confined at a dielectric-metal interface, which travel at a velocity very close to the speed of light. Besides the reduced dimensionality, the SPP-based device is able to increase the speed of the photonic FT by several orders of magnitude with a minimal spatial separation between the input and output.

Materials and methods

Diffraction integral of SPPs and Fourier relationship

For monochromatic propagating SPPs at a source-free metal/dielectric interface in the xz plane, the out-of-plane electric field Ey (in the dielectric medium) satisfies the 2D Helmholtz equation (the section Two-dimensional wave equation, Supplementary Information):

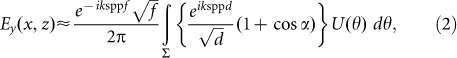

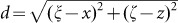

where kspp is the wavevector of the SPPs. The FT performed in free space by a converging lens is, in fact, enabled by the spherical wavefront produced by the lens. Despite the change of dimensionality, a parallel relationship can exist for surface waves such as SPPs. Using the 2D form of the integral theorem of Helmholtz and Kirchhoff23, we calculate the disturbance at point Q in the focal region of a converging cylindrical surface wave as illustrated in Figure 1a provided the focal length (>10 μm) is much larger than the wavelength of the SPPs (the section Propagation integral for SPPs, Supplementary Information):

|

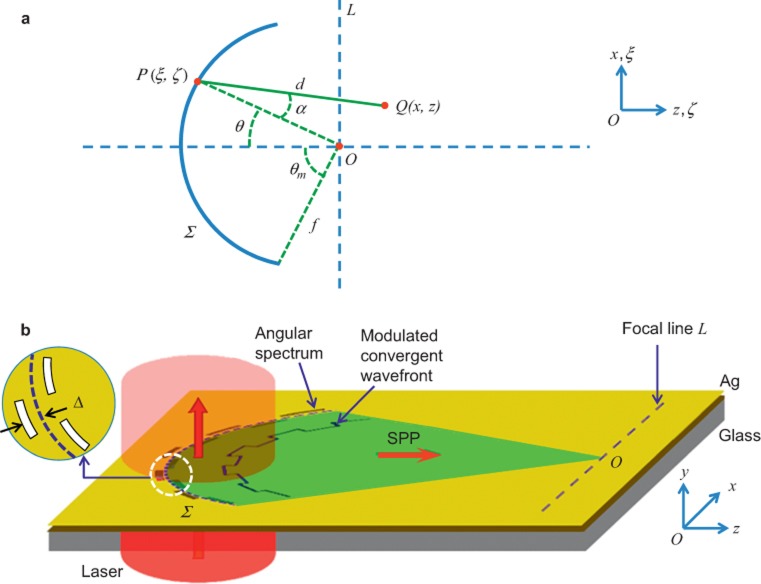

Figure 1.

(a) Schematics of in-plane FT performed by surface wave propagation. In a plane, the disturbance at any point Q(x,z) in the vicinity of focus O(0,0) can be calculated by summing up the contributions from all the points, e.g., P(ξ,ζ) on a convergent wavefront (depicted as the arc Σ with the radius f). d is the distance between P and Q. α measures the inclination angle of the distance with respect to the normal of the arc. The focal line L is perpendicular to the horizontal axis (z or ζ) across the focus. θ is the polar angle in the corresponding polar coordinates. (b) Slits in the angular spectrum represented by a reference arc are perforated in the optically opaque metal film (e.g., Ag) on a glass substrate. When illuminated by a coherent light source such as a laser, the slits generate converging SPPs at the air–Ag interface. The converging wavefront is modulated by the displacement Δ(θ) of the slits from the reference arc (blue dashed curve).

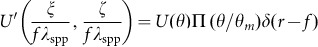

where U(θ) is the complex amplitude on the arc Σ of a reference circle with radius f, the distance between P(ξ, ζ) on Σ and Q(x, z) is  , and α is the inclination angle of the distance with respect to the normal of the arc. We discover that, to a good approximation, a 2D Fourier relationship can be found for the complex amplitude U(θ) along an arc of a converging surface wave and the field distribution Ey(x, z) in the vicinity of the geometrical focus (the section Two-dimensional Fourier relationship for a converging SPP, Supplementary Information):

, and α is the inclination angle of the distance with respect to the normal of the arc. We discover that, to a good approximation, a 2D Fourier relationship can be found for the complex amplitude U(θ) along an arc of a converging surface wave and the field distribution Ey(x, z) in the vicinity of the geometrical focus (the section Two-dimensional Fourier relationship for a converging SPP, Supplementary Information):

with  , where λspp is the wavelength of the SPP;

, where λspp is the wavelength of the SPP;  ; θm is the maximal half polar angle of the arc; Π(•) and δ(•) are the rectangular function and the Dirac delta function, respectively; Fn{•} denotes the n-dimensional FT.

; θm is the maximal half polar angle of the arc; Π(•) and δ(•) are the rectangular function and the Dirac delta function, respectively; Fn{•} denotes the n-dimensional FT.

Projection-slice theorem of SPPs in the focal plane

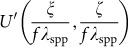

Consequently, using the projection-slice theorem, we find a one-dimensional (1D) Fourier relationship between the field distribution on the focal line L (perpendicular to the propagation axis) and the projection of the complex amplitude U(θ) onto the same line L (the section Projection-slice theorem, Supplementary Information):

where  is the projection of

is the projection of  onto the focal line L and this expression is valid near the focus.

onto the focal line L and this expression is valid near the focus.

This result is instrumental to understanding the present work and we use it here to demonstrate the following examples of Fourier synthesis of a surface wave Ey(x, z) from its angular spectrum. This is made possible through controlling the input U(θ) on a reference arc, since a monochromatic directional surface wave can be fully represented by its transverse profile Ey(x, z = 0).

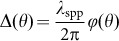

In Figure 1b, we implement U(θ) on an arc consisting of discrete subwavelength slits equally spaced in the azimuthal direction. When illuminated by a laser beam, the ensemble of slits produces SPPs which form a convergent wavefront. Each slit is displaced in the radial direction from the reference arc by  , where ϕ(θ) is the phase of U(θ). To simplify the design, we use phase-only functions for U(θ), since the spectral phase alone is sufficient to synthesize most of surface waves with finite transverse dimensions24. The spectral amplitude can be modulated in the design by controlling the width of slits.

, where ϕ(θ) is the phase of U(θ). To simplify the design, we use phase-only functions for U(θ), since the spectral phase alone is sufficient to synthesize most of surface waves with finite transverse dimensions24. The spectral amplitude can be modulated in the design by controlling the width of slits.

Sample preparation and fabrication

After depositing a 300 nm thick Ag layer onto a silica substrate via electron beam evaporation, we milled the subwavelength slits with a nominal width of 240 nm through the Ag film using a focused ion beam (Zeiss, AURIGA 60). The Ag film is thick enough to entirely block the incident beam, since the penetration depth of 632.8 nm light is just 24 nm in Ag (εAg = – 15.93 + 1.077i). This helps to improve the signal-to-noise ratio of the measured near-field intensity distribution of SPPs. The radius of the reference arc is 15 µm which is a balance between the number of slits and the propagation loss (the SPP propagation length at an Ag/air interface is around 22 µm at this wavelength). In the experiment, these subwavelength slits are designed in a discrete pattern composed of several segments.

Near-field intensity distribution measurements

The intensity distributions of SPP waves were measured by a near-field scanning optical microscope (NSOM, NT-MDT/NTEGRIS Solaris) equipped with an aluminum-coated fiber tip with a 100 nm diameter aperture working in collection mode. The laser was first expanded by a telescope system to a ∼10 mm diameter spot before slightly focused by a low numerical aperture objective lens (4×, NA = 0.13) onto the sample surface, incident from the substrate side. SPPs are excited when the slits are illuminated with the laser beam. Detailed experimental setup is given in the section Experimental setup for measurement of the Supplementary Information.

Results and discussion

Synthesis of plasmonic Weber beam in the Fourier space

First we synthesized a new type of SPP wave dubbed the plasmonic Weber beam (PWB), which we prove to be a rigorous non-diffracting solution of the 1D Helmholtz equation in parabolic cylindrical coordinates (the section Derivation of plasmonic Weber beams in parabolic cylindrical coordinates, Supplementary Information), giving an explicit form of the dominant electric field Ey at z = 0 as:

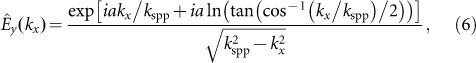

where 2ksppa is the defined separation constant, and 2F1[a; b; v] is the confluent hypergeometric function of the first kind. The complex angular spectrum of the PWB is given by (sections Derivation of plasmonic Weber beams in parabolic cylindrical coordinates and Angular spectrum of the PWB, Supplementary Information):

|

where kx = kspp sin θ is the transverse wavevector. Thus the corresponding offset of the slits (Figure 1b) from the reference arc is given by:

where mod{p, q} gives the remainder after division of p by q.

Near-field measurement of PWB

In the experiment, we used a linearly polarized He-Ne laser with wavelength of 632.8 nm as the coherent source to excite SPPs. Subsequently, these converging SPP waves propagate and interfere at the geometrical focus forming the PWB, and its near-field intensity distribution is measured by NSOM. We choose an angular spectrum ranging from −60° to 60° for the Fourier synthesis of the PWB. The effect of the truncated spectrum on the reconstruction is minimal as the main feature of the PWB is preserved (the section Dependence of PWB on angular range of nanostructure, Supplementary Information).

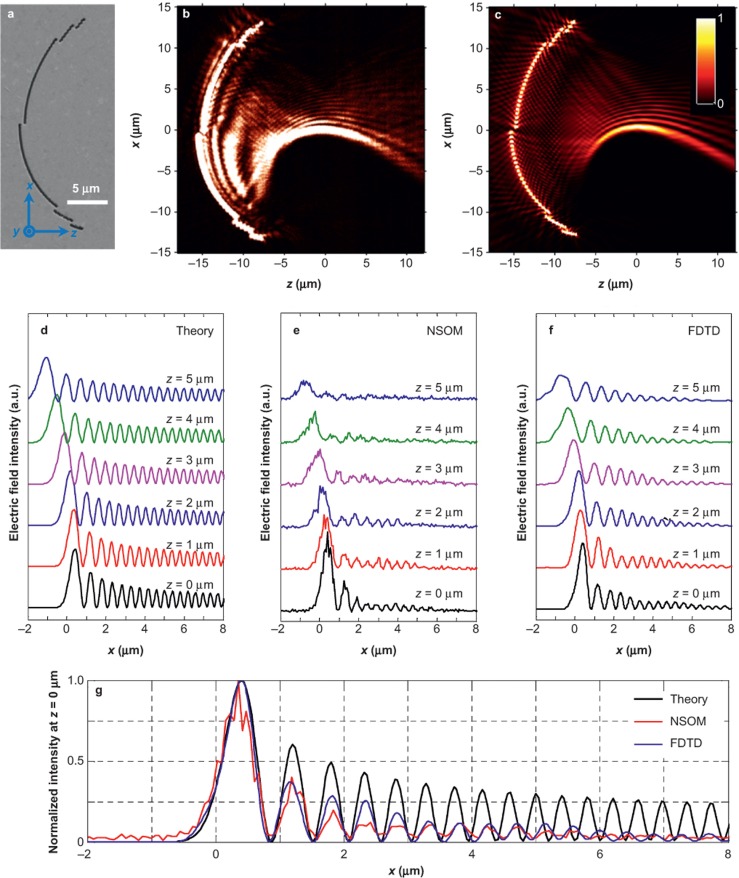

Figure 2a gives the scanning electron microscope micrograph of the first plasmonic nanostructure with a = 40. The NSOM measurement results and supporting numerical calculations using the finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) method in Figure 2b and 2c are in good agreement. The synthetic PWBs propagate along curved trajectories for more than 10 µm beyond the focal line. To verify that the SPP wave is indeed a PWB, we studied its evolution dynamics along its propagation direction and make quantitative comparisons to the experimental results, FDTD simulations, and the theoretical predictions (the section Derivation of plasmonic Weber beams in parabolic cylindrical coordinates, Supplementary Information for the explicit expression of the PWB). The snapshots of the electric field intensity distributions along the +z direction ranging from 0 to 5 µm in steps of 1 µm are juxtaposed in Figure 2d–2f accordingly. All the profiles exhibit the self-bending property consistent with the theory. For example, from z=0 to z = 4 μm, the lateral shifts of the main peak from NSOM, FDTD, and theory are measured as 1.1, 1.16 and 1.48 µm, respectively. However, the intensity of the side lobes in the NSOM and FDTD decreases much faster than the corresponding theoretical prediction. This is attributed to the additional amplitude modulation induced by the polarization selectivity of the slits (the section Angular spectrum of the PWB, Supplementary Information). The arc radius also has a small influence on the properties of the generated PWBs. Due to the spatial extension of the PWB, the actual angular spectrum at points far away from the geometrical center will deviate from the theoretical prediction given by Equation (6). This causes the PWB’s trajectory to be laterally shifted from the original design (the section Effect of the arc radius on the PWB properties, Supplementary Information). In order to improve the excitation efficiency of the SPPs, the structures can be repeated. For example, three periods with separation of λspp can improve the excitation efficiency by six times and the signal-to-noise ratio is much better (the section PWB generation at different geometric parameters (single-period slit of a = 60 and multiple-period slits), Supplementary Information).

Figure 2.

(a) SEM micrograph of the plasmonic nanostructure in the angular spectrum of a PWB (a = 40), consisting of slits (240 nm in width) perforated into a 300 nm thick silver film and fabricated by FIB (Zeiss, 30 kV). The radial spatial shift with respect to reference arc (radius of 15 μm) determines the relative phase in the angular spectrum. The incident beam (λ = 632.8 nm) is z-polarized and illuminates the nanostructure from the substrate side. (b) NSOM measurement and (c) FDTD calculations results of electric field intensity distributions, showing excellent agreement in-between. The snapshots of the beam profiles at various propagation distances from 0 to 5 µm in a step of 1 µm obtained from theory, NSOM, and FDTD are shown in (d), (e), and (f), respectively. (g) Comparison of the normalized intensity distribution in the focal line (z = 0) in the cases of theory, NSOM, and FDTD.

Synthesis and experimental characterization of plasmonic Airy beam

Besides the synthesis of a new surface wave from its angular spectrum, the proposed on-chip FT also simplifies the generation of some well-known surface waves, especially when the angular spectrum of the desired wave is simple. A good example is the Plasmonic Airy Beam (PAB)25,26,27 whose angular spectrum can be represented as28:

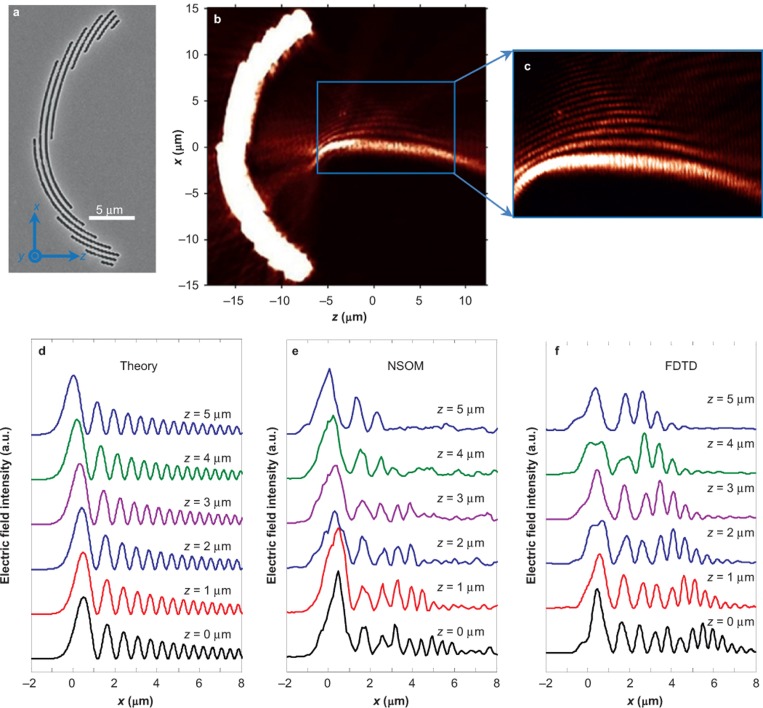

where the parameter b ≪ 1 describes the exponential apodization of the field profile and x0 determines the width of the main lobe. The angular spectrum is essentially a Gaussian distribution modified by a cubic phase term. Therefore, using the same Fourier synthesis procedure we can implement the specific cubic phase in the angular spectrum for the generation of a PAB. Taking the parameters as x0 = 0.5 μm and b = 0.02, we end up with the design shown in Figure 3a, where a three-period design was utilized to provide a better coupling efficiency. At the same polar angle, slits from various reference arcs of different radii are in-phase and thus will provide the same Fourier components in the direction of the focus. The experimental near-field intensity distributions are shown in Figure 3b. The Airy waveform is observed close to the focal plane with the characteristic non-diffracting and self-bending features. Overall consistency has been observed in Figure 3d–3f despite slight discrepancies that can be attributed to the contributions from the slits at large angles beyond the paraxial approximation implied by PABs.

Figure 3.

(a) SEM micrograph of three-period nanostructures to synthesize the PAB, which is a special case of the PWB under paraxial approximation. x0=0.5 μm, r0=15 μm, and b=0.02. (b) NSOM measurement results of near-field electric field intensity distribution. (c) Zoom-in view of the blue box area in (b). For quantitative comparison and comprehensive evaluation of the beam properties, we give the line-to-line intensity distributions from 0 to 5 µm in a step of 1 µm obtained from the analytical formula, NSOM measurement, and FDTD calculation in (d), (e), and (f), respectively.

Conclusions

In summary, we have established a Fourier relationship embedded in the propagation of surface waves, which enables a photonic FT/IFT performed with SPPs. This allows one to design FT-based planar devices to be incorporated into existing integrated optics, marking another step toward on-chip optical computing. Compared with the optical FT in free space, the on-chip configuration plasmonic nanostructures offer four to five orders of magnitude of enhanced processing speed due to the reduced footprint of the device. Considering the short focal length (∼10 μm) of a converging surface wave, the FT can now be finished in tens of femtoseconds. Besides the promising applications in optical computing, one can further synthesize intricate surface waves and even create new exotic surface waveforms (e.g., designer SPPs) to accommodate the wide range of applications of SPPs29,30,31,32.

Authors’ contributions

S.S.K., G.Y., and J.L. designed the experiments, interpreted the results, and prepared the manuscript. E.B. and B.A. prepared the samples. Q.W., L.D., D.Z., D.T., and X.Y. carried out the experiments. All authors commented on the manuscript.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Acknowledgments

This work is partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China 61427819 and the Ministry of Science and Technology of China under National Basic Research Program of China (973) grant (No. 2015CB352004). The preparation of samples was performed in part at the Melbourne Centre for Nanofabrication (MCN) in the Victorian Node of the Australian National Fabrication Facility (ANFF). S.S.K. and J.L. are recipients of the Discovery Early Career Researcher Award funded by the Australian Research Council under projects DE120102352 and DE130100954, respectively. S.S.K. acknowledges the financial support from the La Trobe Research Focus Area (RFA) of Understanding Diseases, the Melbourne Collaboration Grant and the Interdisciplinary Seed Fund through the Melbourne Materials Institute (MMI). J.L. acknowledges the financial support from the Defence Science Institute, Australia. G.H.Y. acknowledges the Advanced Optics in Engineering Programme with Grant number 122-360-0009 from the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) and Singapore Ministry of Education Academic Research Fund Tier 3 with Grant number MOE2011-T3-1-005. Q.W. acknowledges the fellowship support from the A*STAR. The authors would like to thank Dr Henry Cai (Carl Zeiss Pte Ltd, Singapore) for his assistance in preparing the samples.

Note: Accepted article preview online 24 October 2015

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary Information for this article can be found on the Light: Science & Applications' website(http://www.nature.com/lsa/).

Supplementary Information

References

- Bracewell RN. The Fourier Transform and Its Applications. Singapore: McGraw-Hill; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Clemmow PC. The Plane Wave Spectrum Representation of Electromagnetic Fields. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Born M, Wolf E. Principles of Optics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman JW. Introduction to Fourier Optics. Singapore: McGraw-Hill; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Duffieux PM. The Fourier Transform and Its Applications to Optics. New York: Wiley; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Stark H. Applications of Optical Fourier Transforms. Burlington: Elsevier; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Arsenault HH, Szoplik T, Macukow B. Optical Processing and Computing. New York: Academic Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield HJ, Dolev S. Why future supercomputing requires optics. Nat Photonics 2010; 4: 261–263. [Google Scholar]

- Silva A, Monticone F, Castaldi G, Galdi V, Alù A et al. Performing mathematical operations with metamaterials. Science 2014; 343: 160–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang N, Lee H, Sun C, Zhang X. Sub-diffraction-limited optical imaging with a sliver superlens. Science 2005; 308: 534–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zia R, Schuller JA, Chandran A, Brongersma ML. Plasmonics: the next chip-scale technology. Mater Today 2006; 9: 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Engheta N. Circuits with light at nanoscales: optical nanocircuits inspired by metamaterials. Science 2007; 317: 1698–1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosako T, Kadoya Y, Hofmann HF. Directional control of light by a nano-optical Yagi-Uda antenna. Nat Photonics 2010; 4: 312–315. [Google Scholar]

- Chang CM, Tseng ML, Cheng BH, Chu CH, Ho YZ et al. Three-dimensional plasmonic micro projector for light manipulation. Adv Mater 2013; 25: 1118–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drezet A, Genet C, Ebbesen TW. Miniature plasmonic wave plates. Phys Rev Lett 2008; 101: 043902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Alù A. Manipulating light polarization with ultrathin plasmonic metasurfaces. Phys Rev B 2011; 84: 205428. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts A, Lin L. Plasmonic quarter-wave plate. Opt Lett 2012, 37: 1820–1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu NF, Genevet P, Kats MA, Aieta F, Tetienne JP et al. Light propagation with phase discontinuities: generalized laws of reflection and refraction. Science 2011; 334: 333–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genevet P, Yu NF, Aieta F, Lin J, Kats MA et al. Ultra-thin plasmonic optical vortex plate based on phase discontinuities. Appl Phys Lett 2012; 100: 013101. [Google Scholar]

- Laux E, Genet C, Skauli T, Ebbesen TW. Plasmonic photon sorters for spectral and polarimetric imaging. Nat Photonics 2008; 2: 161–164. [Google Scholar]

- Xu T, Wu YK, Luo XG, Guo LJ. Plasmonic nanoresonators for high-resolution colour filtering and spectral imaging. Nat Commun 2010; 1: 59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokogawa S, Burgos SP, Atwater HA. Plasmonic color filters for CMOS image sensor applications. Nano Lett 2012; 12: 4349–4354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker BB, Copson ET. The Mathematical Theory of Huygens’ Principle. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim AV, Lim JS. The importance of phase in signals. Proc IEEE 1981; 69: 529–541. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Wang S, Liu YM, Yin XB, Lu CG et al. Plasmonic Airy beams with dynamically controlled trajectories. Opt Lett 2011; 36: 3191–3193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minovich A, Klein AE, Janunts N, Pertsch T, Neshev DN et al. Generation and near-field imaging of Airy surface plasmons. Phys Rev Lett 2011; 107: 116802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Li T, Wang SM, Zhang C, Zhu SN. Plasmonic Airy beam generated by in-plane diffraction. Phys Rev Lett 2011; 107: 126804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salandrino A, Christodoulides DN. Airy plasmon: a nondiffracting surface wave. Opt Lett 2010; 35: 2082–2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwater HA, Polman A. Plasmonics for improved photovoltaic devices. Nat Mater 2010; 9: 205–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brongersma ML, Shalaev VM. The case for plasmonics. Science 2010; 328: 440–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juan ML, Righini M, Quidant R. Plasmon nano-optical tweezers. Nat Photonics 2011; 5: 349–356. [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Park J, Cho SW, Lee SY, Kang M et al. Synthesis and dynamic switching of surface plasmon vortices with plasmonic vortex lens. Nano Lett 2010; 10: 529–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.