Abstract

Background

A cascade of care framework has been proposed to identify and address implementation gaps in addiction medicine. Using this framework, we characterized temporal trends in engagement in care for opioid use disorder (OUD) in Vancouver, Canada.

Methods

Using data from two cohorts of people who use drugs, we assessed the yearly proportion of daily opioid users achieving four sequential stages of the OUD cascade of care [linkage to addiction care; linkage to opioid agonist treatment (OAT); retention in OAT; and stability] between 2006 and 2016. We evaluated temporal trends of cascade indicators, adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics, HIV/HCV status, substance use patterns, and social-structural exposures.

Results

We included 1615 daily opioid users. Between 2006 and 2016, we observed improvements in linkage to care (73.2% to 78.9%, p=<0.001), linkage to (69.2% to 70.6%, p=0.011) and retention in OAT (29.1% to 35.5%, p=<0.001), and stability (10.4% to 17.1%, p=<0.001). In adjusted analyses, later calendar year of observation was associated with increased odds of linkage to care (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR] = 1.02, 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 1.01–1.04), retention in OAT (AOR 1.02, 95% CI: 1.01–1.04) and stability (AOR=1.03, 95% CI: 1.01–1.05), but not with linkage to OAT (AOR 1.00, 95% CI: 0.98–1.01).

Conclusions

Temporal improvements in OUD cascade of care indicators were observed. However, only a third of participants were retained in OAT in 2016. These findings suggest the need for novel approaches to improve engagement in care for OUD to address the escalating opioid-related overdose crisis.

Keywords: cascade of care, opioid use disorder, opioid agonist therapy, quality indicators, addiction, methadone, buprenorphine/naloxone, performance metrics

1. Introduction

North America is facing a public health crisis from opioid-related morbidity and mortality. More than 42,000 people in the United States (U.S.) died from an opioid overdose in 2016, and it is estimated that over 2.5 million Americans have an opioid use disorder (OUD) (Seth et al., 2018). In Canada, some jurisdictions are facing similar overdose epidemics, largely as a result of illicitly manufactured fentanyl and related analogues (BC Coroners Service, 2018; Gomes et al., 2017). For example, in British Columbia (BC) there were over 1,400 illicit drug overdose deaths in 2017 (30.1 deaths per 100,000 individuals), an almost three-fold increase from 2015 (BC Coroners Service, 2018).

Untreated OUD remains one of the major drivers of the present opioid overdose crisis. Indeed, despite the known benefits of opioid agonist therapy (OAT) with buprenorphine/naloxone or methadone in reducing opioid-related morbidity and mortality (Connery, 2015; Degenhardt et al., 2011; MacArthur et al., 2012; Sordo et al., 2017), significant barriers to uptake and retention in OAT persist (Sharma et al., 2017). Accordingly, there remains an urgent need to expand access to OAT (Murthy, 2016; Nosyk et al., 2013; Socias and Ahamad, 2016), and scale-up has begun in some settings. Rigorously monitoring the progress of such initiatives will be critical to optimize their impact. Drawing from recent efforts to scale up access to antiretroviral therapy to curb the HIV epidemic, the cascade of care framework has been recently proposed as a potential tool to monitor care for substance use disorders (Socias et al., 2016; Williams et al., 2017). Therefore, the objective of this analysis was to empirically test the cascade of care framework as a tool to characterize temporal changes in engagement in care for OUD in Vancouver, Canada, between 2006–2016.

2. Material and methods

2.1 Study setting

Vancouver is home to a large number of people who use/inject illicit drugs (PWUD/PWID), which has been estimated to be approximately 12,000 (Remis et al., 1998). During the 1990s, the city experienced an outbreak of HIV among PWID, which peaked in 1994–1996 (Hyshka et al., 2012). In response, provincial authorities adopted a multifaceted approach, including the scale up of harm reduction services (e.g., needle and syringe distribution programs, the first supervised injection site in North America), low-threshold addiction treatment programs (including OAT programs), and expansion of antiretroviral treatment coverage. As a result of these policies, the number of new HIV infections among PWID declined, and has remained low, particularly since 2008 (Montaner et al., 2014).

BC’s OAT program was established in 1996, and rapidly expanded from less than 3,000 enrolled individuals in 1996 to more than 19,000 in 2016 (Eibl et al., 2017; Office of the Provincial Health Officer, 2017). Medical care and prescription drugs received in the context of OAT are fully publicly funded for low-income residents; individuals who are not eligible for this benefit are responsible for paying for a percentage of the medication cost either through private insurance plans or out-of-pocket (Eibl et al., 2017). Both methadone and buprenorphine/naloxone can be prescribed by primary care physicians and dispensed through community-based pharmacies in a low-threshold OAT model (Nosyk et al., 2013). Methadone maintenance therapy (MMT) has historically been the standard of care for OUD in BC, and in 2016 over 80% of individuals on OAT in the province were on MMT (Office of the Provincial Health Officer, 2017). Buprenorphine/naloxone was introduced to the provincial drug formulary in 2010. Since then, the number of individuals receiving buprenorphine-based OAT has been steadily increasing, particularly after 2015 when buprenorphine/naloxone was added as regular health care benefit (i.e., no need to previously “fail” MMT) (Office of the Provincial Health Officer, 2017). During the study period, injectable OAT (i.e., diacetylmorphine and hydromorphone) was only available in research settings. In February 2014, a number of regulatory changes were introduced to BC’s OAT program, including a change in the methadone formulation, and restrictions in pharmacy delivery services, which resulted in a number of concerns among OAT clients (McNeil et al., 2015; Socias et al., 2017).

2.2 Study design and population

Data for this study were drawn from two harmonized open and ongoing community-recruited prospective cohorts of over 2,000 adult PWUD: the Vancouver Injection Drug Users Study (VIDUS) and the AIDS Care Cohort to Evaluate exposure to Survival Services (ACCESS). VIDUS consists of HIV-negative adults (i.e., ≥ 18 years old) who injected drugs in the month prior to enrolment and began recruitment in 1996. ACCESS started in 2005, and consists of HIV-positive adults who used illicit drugs (other than or in addition to cannabis) in the previous month. Individuals are recruited through snowball sampling and extensive street outreach in the greater Vancouver region. Average semi-annual follow-up rates for the two cohorts are approximately 70%.

Study procedures for the two cohorts are harmonized to allow for pooled analyses, and have been described in detail previously (Strathdee et al., 1998; Wood et al., 2008). In brief, after providing written informed consent, at baseline and semi-annually thereafter, participants undergo an interviewer-administered questionnaire, provide blood for HIV/ HCV serological testing and HIV clinical monitoring as appropriate, and are examined by a study nurse. The questionnaire collects information on socio-demographic characteristics, drug use patterns, health care access and utilization, including HIV and addiction care, as well as other relevant social-structural exposures, such as housing status and criminal justice system exposure. Participants received a $30 honorarium at each study visit. The studies have received approval by the University of British Columbia/Providence Health Care Research Ethics Board.

For the present study, the analytic sample was restricted to participants enrolled between January 1, 2006 and December 31, 2016 who reported ≥ daily non-medical opioid use (e.g., heroin, street methadone, street fentanyl, street oxycodone) in the past six months at the baseline interview (hereafter, daily opioid users). Participants with no baseline daily non-medical opioid use, but who reported subsequent daily non-medical opioid use during follow-up, were included from that time point forward.

2.3 Measures

Our primary outcome of interest was achievement of each of the four defined stages along the OUD cascade of care. Although no standardized definitions exist for these indicators, whenever possible we followed and adapted those recently proposed to track the quality of addiction (Socias et al., 2016; Williams et al., 2017) and HIV care (Nosyk et al., 2014). For each calendar year (from 2006 to 2016) we assessed the following indicators: (1) linked to addiction care (i.e., ≥ one observation in a given calendar year where the participant reported being enrolled in any addiction treatment in the previous six months, including OAT, residential treatment, detox); (2) linkage to OAT [i.e., ≥ one observation in a given calendar year where the participant reported being enrolled in OAT (methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone) in the previous six months]; (3) retained in OAT (i.e., ≥ two observations in a given calendar year at least three months apart where the participant reported being enrolled on OAT); and (4) stable (i.e., no self-reported overdoses, no binge drug use and no fair/poor self-reported health due to drug use among participants retained in OAT in the calendar year). Participants with no reports of addiction treatment in a given calendar year were considered unlinked to care for that year. In this model, individuals need to have reached all previous stages in order to be eligible to achieve subsequent stages. That is, an individual cannot be retained in OAT, unless they were previously linked to OAT, which in turns requires to be linked to general addiction services. Individuals can also move from one stage to another (increasing or decreasing their engagement with addiction health services) over time.

Our primary explanatory variable of interest was calendar year of observation. We also considered other covariates that have been shown to influence engagement in healthcare among PWUD. These included: socio-demographic characteristics (age, sex, ethnicity, maximum educational attainment); drug use patterns (≥ daily cocaine injection, ≥ daily crack use); comorbidities (HIV and HCV infection); and social-structural exposures (homelessness, incarceration). All socio-demographic characteristics except for age were time-fixed at baseline; age was time-updated on July 1 of each year; and all other variables were time-updated and refer to the six-month period prior to the interview.

2.4 Missing data

Missing data was overall low, with a median number of one missed follow-up visit (interquartile range [IQR] 0–3) and <1% of missing data for explanatory variables. During the study period, 147 (9.1%) participants died, and 13 (0.8%) were lost to follow-up.

2.5 Statistical analyses

As a first step, we conducted descriptive statistics to examine baseline characteristics of the entire sample. Then, percentages of participants at each stage of the cascade were determined, using as denominator the total population of daily opioid users who completed at least one follow-up visit in a given year. Temporal trends of the proportion of daily opioid users in each stage of the OUD cascade of care were investigated using the Cochran-Armitage test. Finally, we used generalized estimating equation (GEE) regression modeling, using an exchangeable correlation structure, to analyze marginal changes in engagement in OUD care over time. We constructed separate models for each of the four proposed cascade stages (i.e., linked to addiction care, initiated OAT, retained in OAT, and stable). Each multivariable model included calendar year of observation, as well as covariates associated with a particular outcome of interest in bivariable analysis at a p-value <0.10. We used a confounding model approach previously described by Maldonado and Greenland (1993).

To assess the robustness of our models, we conducted a series of sensitivity analyses. First, to estimate subject-specific effects, we re-ran the analyses using a mixed-effects modelling approach [i.e., generalized linear mixed effect model (GLMM)]. Second, to further examine temporal trends in engagement in OUD care, we fitted an ordinal GLMM, where higher stages in the cascade were coded with higher values. Third, to explore the impacts of regulatory changes introduced to the BC OAT program in 2014, we built a model using as primary explanatory variable a categorical measure of year, dichotomized at </≥ year 2014. Fourth, all analyses were conducted using R studio (Version 3.2.4) (R Core Team, 2016), and all p-values are two-sided.

3. Results

Between January 2006 and December 2016, 1615 daily opioid users were enrolled, of whom 1479 (91.6%) reported daily opioid use at their baseline visit. These 1615 participants contributed 9137 person-years of observation, or a median of six years per participant (IQR 2–10), with an average yearly retention rate of 74%. Baseline characteristics of participants, stratified by gender, are reported in Table 1. The median age was 41 years (IQR 34–47), 992 (61.4%) were male, 992 (61.4%) were Caucasian, 585 (36.2%) were living with HIV and 1428 (88.4%) were HCV-antibody positive.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 1615 ≥ daily opioid users, stratified by gender, Vancouver, Canada, 2006–2016.

| Characteristic | Total, n (%) N = 1615) |

Gender, n (%) | p - value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Male (n = 992) | Female (n = 623) | |||

| Socio-demographics | ||||

| Age (median, IQR) | 41 (34–48) | 43 (36–49) | 38 (31–45) | <0.001† |

| Caucasian ethnicity | 992 (61.4) | 692 (69.8) | 300 (48.2) | <0.001 |

| ≥High school education | 769 (47.6) | 507 (51.1) | 262 (42.1) | 0.001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| HIV-positive# | 585 (36.2) | 356 (35.9) | 229 (36.8) | 0.723 |

| HCV-positive# | 1428 (88.4) | 879 (88.6) | 549 (88.1) | 0.833 |

| Substance use-related factors | ||||

| ≥Daily cocaine injection# | 206 (12.8) | 132 (13.3) | 74 (11.9) | 0.402 |

| ≥Daily crack use# | 742 (45.9) | 415 (41.8) | 327 (52.5) | <0.001 |

| Social-structural factors | ||||

| Homeless# | 668 (41.4) | 409 (41.2) | 259 (41.6) | 0.829 |

| Incarceration# | 356 (22.0) | 238 (24.0) | 118 (18.9) | 0.020 |

IQR, interquartile range.

Refers to the 6-month period prior to enrolment

Wilcoxon rank sum test

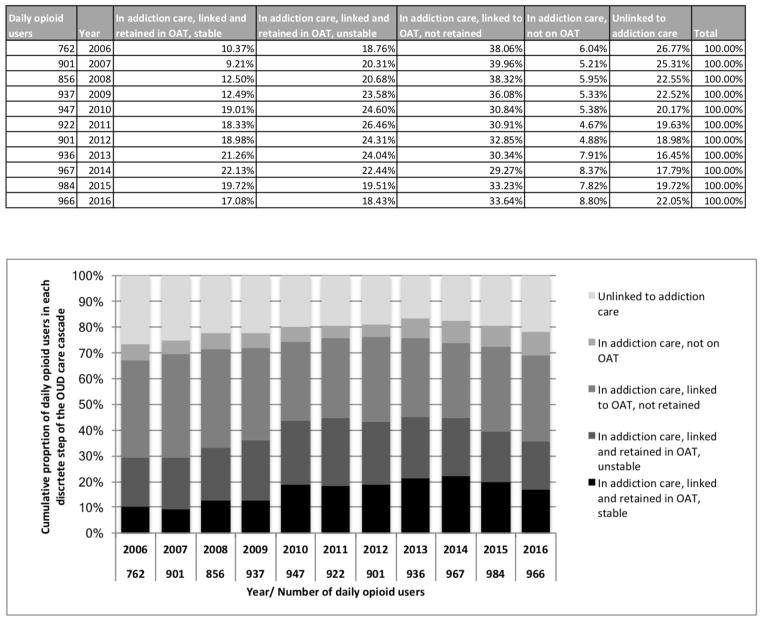

Figure 1 depicts changes over time of the proportion of participants achieving each stage of the OUD cascade of care. This figure displays the relative contributions of mutually exclusive stages to a particular stage of the cascade in a given year. For example, although the proportion of individuals linked to OAT (sum of black, darkest grey and second darkest grey bars) was similar for 2009 and 2015 (72.2% and 72.5%, respectively), the proportion of individuals who were linked but not retained in OAT (second darkest grey) was higher in 2009 (36.1% vs. 33.2%), while the proportion of those retained in OAT and stable (black) was higher in 2015 (19.7% vs. 12.5%).

Figure 1.

Temporal trends in the proportion of participants ever reporting ≥ daily non-medical opioid use in each OUD care cascade stage, Vancouver, Canada, 2006–2016.

Note: OUD, opioid use disorders. OAT, opioid agonist therapy.

All cascade indicators improved between 2006 and 2016. The proportion of participants out of addiction care decreased from 26.8% to 22.1% (p<0.001), while increases were seen for linkage to (67.2% to 69.1%, p=0.038) and retention in OAT (29.1% to 35.1%, p<0.001), and stability (10.4% to 17.1%, p<0.001). As these numbers suggest, the largest gains were in the last two stages of the cascade. However, as shown in Figure 1, after an initial steady improvement in cascade indicators (peaking in 2014), we observed a slight decline in the proportion of daily opioid users engaged in the OUD cascade of care in 2015–2016.

Table 2 presents the results of the unadjusted and adjusted GEE analyses of achieving each of the four stages of the OUD cascade care. In unadjusted analysis, later year of observation was significantly and positively associated with achieving each of the four cascade stages. Other variables that showed an overall positive association with progressing through the cascade in bivariable analyses were older age, Caucasian ethnicity, and HIV and HCV infection. Conversely, daily crack use, homelessness and incarceration were generally associated with less likelihood of achieving each of the four cascade stages. In the final adjusted models, later calendar year of observation remained significantly associated with increased odds of linkage to addiction care (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR] = 1.02, 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 1.01–1.04), retention in OAT (AOR = 1.02, 95%CI: 1.01–1.04) and stability (AOR=1.03, 95% CI: 1.01–1.05), but not with linkage to OAT (AOR = 1.00, 95% CI: 0.98–1.01).

Table 2.

Crude and adjusted GEE analyses of OUD cascade of care indicators among daily opioid users, Vancouver, Canada, 2006–2016.

| Linked to addiction care | Linked to OAT | Retained in OAT | Stable | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| OR (95% CI) | AOR (95 % CI)‡ | OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI)‡ | OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI)‡ | OR (95% CI) | AOR (95 % CI)‡ | |

| Primary variable of interest | ||||||||

| Calendar-year of observation | 1.05 (1.03 – 1.07) | 1.02 (1.01 – 1.04)* | 1.03 (1.01 – 1.04) | 1.00 (0.98 – 1.01) | 1.05 (1.04 – 1.07) | 1.02 (1.01 – 1.04)* | 1.10 (1.08 – 1.12) | 1.03 (1.01 – 1.05)* |

| Covariates | ||||||||

| Age (per year older)† | 1.03 (1.02 – 1.04)# | 1.01 (1.01 – 1.02)* | 1.02 (1.01 – 1.03)# | 1.01 (1.01 – 1.02)* | 1.04 (1.03 – 1.05)# | 1.03 (1.02 – 1.04)* | 1.05 (1.04 – 1.06)# | 1.03 (1.02 – 1.04)* |

| Male gender | 0.81 (0.68 – 0.97)# | 0.72 (0.60 – 0.87)* | 0.72 (0.61 – 0.86)# | 0.63 (0.52 – 0.75)* | 0.93 (0.81 – 1.07) | 1.11 (0.93 – 1.31) | ||

| Caucasian ethnicity | 1.38 (1.16 – 1.64)# | 1.50 (1.24 – 1.80)* | 1.34 (1.13 – 1.59)# | 1.49 (1.24 – 1.78)* | 1.20 (1.04 – 1.39)# | 1.12 (0.97 – 1.30) | 1.17 (0.99 – 1.39)# | |

| ≥High school education | 1.22 (1.02 – 1.45)# | 1.12 (0.95 – 1.33) | 1.09 (0.95 – 1.26) | 1.17 (0.99 – 1.38)# | ||||

| HIV–positive† | 1.45 (1.19 – 1.78)# | 1.39 (1.14 – 1.70)* | 1.70 (1.40 – 2.08)# | 1.63 (1.33 – 1.98)* | 1.26 (1.10 – 1.45)# | 1.07 (0.90 – 1.27) | ||

| HCV–positive† | 1.39 (1.06 – 1.83)# | 1.29 (0.95 – 1.68) | 1.64 (1.27 – 2.12)# | 1.40 (1.07 – 1.84)* | 1.79 (1.39 – 2.31)# | 1.49 (1.14 – 1.94)* | 1.57 (1.16 – 2.13)# | |

| ≥Daily cocaine injection† | 1.00 (0.84 – 1.19) | 0.97 (0.83 – 1.12) | 1.16 (1.00 – 1.35)# | 0.50 (0.39 – 0.64)# | ||||

| ≥Daily crack use† | 0.77 (0.69 – 0.86)# | 0.88 (0.78 – 0.98)* | 0.82 (0.73 – 0.91)# | 0.88 (0.79 – 0.99)* | 1.08 (0.96 – 1.21) | 0.41 (0.35 – 0.49)# | 0.52 (0.45 – 0.62)* | |

| Homeless† | 0.71 (0.64 – 0.79)# | 0.82 (0.73 – 0.91)* | 0.72 (0.61 – 0.86)# | 0.79 (0.71 – 0.87)* | 0.74 (0.66 – 0.82)# | 0.84 (0.75 – 0.93)* | 0.52 (0.44 – 0.61)# | 0.70 (0.59 – 0.83)* |

| Incarceration† | 0.74 (0.64 – 0.79)# | 0.87 (0.76 – 0.99)* | 0.76 (0.67 – 0.86)# | 0.87 (0.77 – 0.99)* | 0.77 (0.67 – 0.88)# | 0.47 (0.38 – 0.58)# | 0.67 (0.53 – 0.83)* | |

Refers to the 6-month period prior to the interview

Only the variables included in the final multivariable confounder model are presented in this column

p<0.10 in the unadjusted analyses and considered for inclusion in the multivariable model

p<0.05 in the final multivariable confounder model

Sensitivity analyses estimating subject-specific effects yielded similar results to the main analysis (supplementary table 11). Likewise, the multivariable ordinal model identified a trend towards higher engagement in OUD care over time (AOR = 1.01, 95% CI: 1.00–1.02, supplementary table 21). Finally, the model exploring the impact of the regulatory changes introduced to the BC OAT program in 2014 showed that years 2014–2016 were associated with decreased odds of linkage to (AOR = 0.72–95% CI: 0.61–0.85) and retention in OAT (AOR = 0.89–95% CI: 0.79–0.99; supplementary table 31).

4. Discussion

Originally proposed to measure the population-level performance of HIV care systems (Gardner et al., 2011), the cascade of care framework has been adapted to evaluate the quality of health care delivery for other communicable and non-communicable chronic diseases, such as hepatitis C and diabetes (Ali et al., 2014; Socias et al., 2015; Socias et al., 2016). To our knowledge, this is the first study to utilize a cascade of care framework to characterize temporal patterns of engagement in OUD care.

This study identified marginal improvements in the four OUD cascade of care indicators assessed over an 11-year period in Vancouver, resulting in an overall reduction of individuals out of addiction care. This progress might be a reflection of efforts to expand access to low-threshold addiction treatment as part of the province’s response to HIV among PWID beginning in the mid-1990s (Hyshka et al., 2012; Montaner et al., 2014). The largest gains were observed in the last two cascade stages. While this is encouraging, it should be noted that after a steady increase in the proportion of participants meeting each of the cascade stages between 2006 and 2014, we observed a declining trend in the last two years of the study period. This worsening of cascade indicators occurred after regulatory changes to the BC OAT program in February 2014, and are consistent with prior research (McNeil et al., 2015; Socias et al., 2017). Specifically, both quantitative and qualitative studies demonstrated interruptions in OAT and co-dispensed medications (e.g., antiretroviral therapy) following restrictions on pharmacy delivery services, as well as increases in injection opioid use, which might be explained by “change intolerance” to the new methadone formulation experienced by some OAT clients (McNeil et al., 2015; Socias et al., 2017). Importantly, had a quality improvement framework (e.g., cascade of care) been in place (Clarke et al., 2016), it may have facilitated early identification of the worsening of cascade indicators, interventions to prevent attrition, and potentially averted some of the overdose deaths observed during this period.

Our analysis also revealed that the majority of our sample (ranging between 70% and 85%) was linked to addiction treatment during the study period, of whom, most had also initiated OAT. These figures stand in sharp contrast with estimates from the U.S. indicating that only 20–40% of individuals with OUD receive any addiction care in a given year, and even less initiate evidence-based OAT (Williams et al., 2017). These differences in accessibility to addiction care, and in particular to OAT, may be partially explained by the low-threshold OAT model employed in Vancouver, where both methadone and buprenorphine/naloxone can be prescribed by primary care physicians and are dispensed through community-based pharmacies (Nosyk et al., 2013). That said, these findings should be interpreted with caution as results from the present analysis may not be generalizable to the overall population of people with OUD in Vancouver. In addition, while OUD treatment access rates observed in this study is reassuring, these numbers also indicate that in 2016 approximately 30% of participants were not receiving evidence-based treatment for OUD (including almost one quarter who were completely out of addiction care). This is concerning, since the expansion of access to evidence-based treatment for OUD (i.e., OAT) has been identified as one of the major priorities to address the overdose crisis (Murthy, 2016; Socias and Ahamad, 2016). Fragmentation of addiction-related services, lack of trained addiction medicine providers, persistent criminalization and incarceration of PWUD, and stigma have been cited as structural barriers to linkage to OAT (Nosyk et al., 2013; Sharma et al., 2017). Overcoming such barriers will require a multidisciplinary and collaborative approach, including the training of health care providers in evidence-based OUD care, and expansion and integration of addiction services to promote continuity of care. For example, rapid (re)-initiation of buprenorphine/naloxone in emergency departments or other acute care settings with coordinated referral to primary care for follow-up addiction care has been shown to be feasible and effective in linking individuals to care in other chronic diseases (D’Onofrio et al., 2015; Pilcher et al., 2017), and thus deserves further evaluation.

Finally, in line with administrative health data from the province and elsewhere (Office of the Provincial Health Officer, 2017; Timko et al., 2016), we noted a major loss at the retention in care stage, with just over a third of participants being retained in OAT in 2016 — a 50% loss from the previous stage. This high attrition rate may reflect patient choice, discontent with certain forms of OAT or difficulty in finding an OAT provider in the community (McEachern et al., 2016; Teruya et al., 2014; Yarborough et al., 2016). In particular, MMT presents patient acceptability challenges as a result of a range of reported concerns with the side effect profile of methadone, including sedation, sexual dysfunction, and tooth decay (Yee et al., 2014), as well as the need for daily attendance at a pharmacy for witnessed ingestion. Buprenorphine/naloxone-based OAT may present a relative advantage in this regard given the better tolerability and safety profile, as well as the potential for take-home doses, which may contribute to patient autonomy and satisfaction (Connery, 2015) and lower overdose risk (Sordo et al., 2017). Of note, in the present analysis we observed a steep increase in retention and stability rates after 2010, which coincided with the introduction of buprenorphine/naloxone in the province drug formulary. An alternative explanation to low retention rates observed in this setting may relate to preferences among some clinicians for early tapering (Nosyk et al., 2010). For example, an evaluation of the MMT program in BC indicated that almost half of all treatment episodes between 1996–2006 included an attempted taper, with 70% of them occurring within 12 months of treatment initiation (Nosyk et al., 2010), and that the majority of the cases were unsuccessful. These findings reinforce the need for evidence-based guidelines for the management of OUD (including recommendations for long-term maintenance OAT), especially since sustained engagement in OAT has been associated with improved outcomes, including reduced illicit opioid use and mortality (Sordo et al., 2017; Timko et al., 2016). As suggested by a recent systematic review (Sordo et al., 2017), the opioid-related and overall mortality risk is sharply reduced after the first four weeks of OAT, remaining low thereafter while on OAT and increasing again after OAT cessation, further highlighting the critical importance of efforts to improve retention, particularly during the first “golden month” of OAT (Manhapra et al., 2017). Within the health system, patient navigation models may hold promise as a relatively low-cost strategy (particularly if peers are recruited as navigators) to promote engagement (Byers, 2012). Indeed, patient navigation programs have been found to improve engagement with the health system, health outcomes and treatment satisfaction for a number of chronic diseases, particularly among vulnerable populations (Ali-Faisal et al., 2017). Alongside continued efforts to improve access and retention to low-threshold MMT and buprenorphine-based OAT, additional evidence-based treatments are needed for individuals who may not have benefited from these limited choices, including oral (e.g., slow-release oral morphine) (Beck et al., 2014) and injectable alternatives (e.g., diacetylmorphine, hydromorphone) (Kerr et al., 2010; Oviedo-Joekes et al., 2016).

Limitations to our study include the non-random selection of our study sample. Therefore, findings from this analysis may not be representative of patterns of engagement in the OUD cascade of care in Vancouver or other settings. However, outcome measure rates observed in this analysis are consistent with those observed at the provincial level (Office of the Provincial Health Officer, 2017). Second, our study instrument did not allow for diagnosis and severity of OUD. Although we included daily opioid users as a proxy for the population of individuals with OUD in our cohorts, the need for OUD treatment may have been over-estimated. Third, many measures, including OAT access and utilization and substance use, were based on self-report, which might be prone to responses biases. However, prior research has shown PWUD’s reports of drug use and addiction treatment to be reliable (De Irala et al., 1996; Langendam et al., 1999). Fourth, although our multivariable analyses indicated temporal improvements in some indicators of opioid addiction care, given the observational nature of the study we cannot exclude the possibility of unmeasured confounding. In addition, causal factors related to these changes were not investigated. Finally, the statistical modelling used (i.e., confounding model) does not allow for unbiased inferences of associations of covariates and each of the outcomes. Thus, further research is needed to confirm associations found in bivariable analyses.

5. Conclusions

In summary, using a cascade of care framework, we found overall improvements in four OUD care indicators among two-community recruited cohorts of PWUD in Vancouver, Canada. Although this is encouraging, our analysis also showed that, coinciding with the escalation of the opioid crisis in this setting, there was a worsening of these performance measures, with only over a third of participants being retained in OAT in 2016. These results point to the urgent need for novel approaches to improve linkage and retention in OAT, as well as to expand OAT alternatives to address the opioid-related overdose crisis. The cascade of care framework has high potential to monitor and evaluate these efforts, and anticipate and address future crises.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Most opioid use disorder cascade of care indicators improved between 2006—2016

A worsening trend arose after 2014

Only one third of participants were retained in opioid agonist therapy in 2016

The cascade of care has potential to monitor efforts to optimize opioid addiction care

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the study participants for their contributions to the research, as well as current and past researchers and staff. We would specifically like to thank: Tricia Collingham, Jennifer Matthews, Steve Kain, and Sarah Sheridan for their research and administrative assistance.

Role of the Funding Sources

This work was supported by the US National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) at the US National Institutes of Health (NIH; U01-DA038886 and U01-DA021525). MES is supported by Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR) and Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) fellowship awards. M-JM is supported in part by NIH (U01-DA021525), a Scholar Award from MSFHR and a New Investigator award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). EW is supported in part by a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Inner City Medicine. TK is supported in part by a CIHR Foundation Grant (20R74326). JM is supported by the British Columbia Ministry of Health and through an Avant-Garde Award from NIDA at the NIH (1DP1DA026182). KH is supported by the St. Paul’s Hospital Foundation, a CIHR New Investigator Award and MSFHR Scholar Award. SN is supported by a Health Professional Investigator Scholar Award from MSFHR. JM is supported by the British Columbia Ministry of Health and through an Avant-Garde Award from NIDA at the NIH (1DP1DA026182). KH is supported by the St. Paul’s Hospital Foundation, a CIHR New Investigator Award and MSFHR Scholar Award.

Footnotes

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi:...

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi:...

Contributors

MES, EW and MJM designed the study. EN conducted the statistical analysis. MES wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results, provided critical revisions to the article, and read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The University of British Columbia has received unstructured funding from NG Biomed, Ltd., an applicant to the Canadian federal government for a licence to produce medical cannabis, to support M-JM. JM has received limited unrestricted funding, paid to his institution, from Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Merck and ViiV Healthcare. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ali MK, Bullard KM, Gregg EW, Del Rio C. A cascade of care for diabetes in the United States: Visualizing the gaps. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:681–689. doi: 10.7326/M14-0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali-Faisal SF, Colella TJ, Medina-Jaudes N, Benz Scott L. The effectiveness of patient navigation to improve healthcare utilization outcomes: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100:436–448. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BC Coroners Service. Illicit Drug Overdose Deaths in BC (Jan 2008 – Feb 2018) 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Beck T, Haasen C, Verthein U, Walcher S, Schuler C, Backmund M, Ruckes C, Reimer J. Maintenance treatment for opioid dependence with slow-release oral morphine: A randomized cross-over, non-inferiority study versus methadone. Addiction. 2014;109:617–626. doi: 10.1111/add.12440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers T. Assessing the value of patient navigation for completing cancer screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:1618–1619. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke CM, Cheng T, Reims KG, Steinbock CM, Thumath M, Milligan RS, Barrios R. Implementation of HIV treatment as prevention strategy in 17 Canadian sites: Immediate and sustained outcomes from a 35-month Quality Improvement Collaborative. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25:345–354. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connery HS. Medication-assisted treatment of opioid use disorder: Review of the evidence and future directions. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2015;23:63–75. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio G, O’Connor PG, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, Busch SH, Owens PH, Bernstein SL, Fiellin DA. Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313:1636–1644. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.3474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Irala J, Bigelow C, McCusker J, Hindin R, Zheng L. Reliability of self-reported human immunodeficiency virus risk behaviors in a residential drug treatment population. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143:725–732. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Bucello C, Mathers B, Briegleb C, Ali H, Hickman M, McLaren J. Mortality among regular or dependent users of heroin and other opioids: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Addiction. 2011;106:32–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eibl JK, Morin K, Leinonen E, Marsh DC. The state of opioid agonist therapy in Canada 20 years after federal oversight. Can J Psychiatry. 2017;62:444–450. doi: 10.1177/0706743717711167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, Del Rio C, Burman WJ. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:793–800. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes T, Greaves S, Martins D, Bandola D, Tadrous M, Singh S, Juurlink D, Mamdani M, Paterson M, Ebejer M, May D, Quercia J. Latest trends in opioid-related deaths in Ontario: 1991 to 2015. Ontario Drug Policy Research Network; Toronto, ON, Canada: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hyshka E, Strathdee S, Wood E, Kerr T. Needle exchange and the HIV epidemic in Vancouver: Lessons learned from 15 years of research. Int J Drug Policy. 2012;23:261–270. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr T, Montaner JS, Wood E. Science and politics of heroin prescription. Lancet. 2010;375:1849–1850. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60544-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langendam MW, van Haastrecht HJ, van Ameijden EJ. The validity of drug users’ self-reports in a non-treatment setting: Prevalence and predictors of incorrect reporting methadone treatment modalities. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28:514–520. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.3.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacArthur GJ, Minozzi S, Martin N, Vickerman P, Deren S, Bruneau J, Degenhardt L, Hickman M. Opiate substitution treatment and HIV transmission in people who inject drugs: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:e5945. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado G, Greenland S. Simulation study of confounder-selection strategies. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138:923–936. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manhapra A, Rosenheck R, Fiellin DA. Opioid substitution treatment is linked to reduced risk of death in opioid use disorder. BMJ. 2017:357. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEachern J, Ahamad K, Nolan S, Mead A, Wood E, Klimas J. A needs assessment of the number of comprehensive addiction care physicians required in a canadian setting. J Addict Med. 2016;10:255–261. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil R, Kerr T, Anderson S, Maher L, Keewatin C, Milloy MJ, Wood E, Small W. Negotiating structural vulnerability following regulatory changes to a provincial methadone program in Vancouver, Canada: A qualitative study. Soc Sci Med. 2015;133:168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaner JS, Lima VD, Harrigan PR, Lourenco L, Yip B, Nosyk B, Wood E, Kerr T, Shannon K, Moore D, Hogg RS, Barrios R, Gilbert M, Krajden M, Gustafson R, Daly P, Kendall P. Expansion of HAART coverage is associated with sustained decreases in HIV/AIDS morbidity, mortality and HIV transmission: The “HIV treatment as prevention” experience in a Canadian setting. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87872. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy VH. Ending the opioid epidemic - A call to action. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2413–2415. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1612578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosyk B, Anglin MD, Brissette S, Kerr T, Marsh DC, Schackman BR, Wood E, Montaner JSG. A call for evidence-based medical treatment of opioid dependence in the United States and Canada. Health Affairs. 2013;32:1462–1469. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosyk B, Marsh DC, Sun H, Schechter MT, Anis AH. Trends in methadone maintenance treatment participation, retention, and compliance to dosing guidelines in British Columbia, Canada: 1996–2006. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;39:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosyk B, Montaner JS, Colley G, Lima VD, Chan K, Heath K, Yip B, Samji H, Gilbert M, Barrios R, Gustafson R, Hogg RS, Group SHAS. The cascade of HIV care in British Columbia, Canada, 1996–2011: A population-based retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:40–49. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70254-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Provincial Health Officer. BC Opioid Substitution Treatment System, Performance Measures 2014/2015 – 2015/2016. British Columbia Ministry of Health; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Oviedo-Joekes E, Guh D, Brissette S, Marchand K, MacDonald S, Lock K, Harrison S, Janmohamed A, Anis AH, Krausz M, Marsh DC, Schechter MT. Hydromorphone compared with diacetylmorphine for long-term opioid dependence: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:447–455. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilcher CD, Ospina-Norvell C, Dasgupta A, Jones D, Hartogensis W, Torres S, Calderon F, Demicco E, Geng E, Gandhi M, Havlir DV, Hatano H. The effect of same-day observed initiation of antiretroviral therapy on hiv viral load and treatment outcomes in a us public health setting. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;74:44–51. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Remis RS, Strathdee SA, Millson M, Leclerc P, Degani N, Palmer RWH, Taylor C, Bruneau J, Hogg RS, Routledge R. Consortium to characterize injection drug users in Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver, Canada: Final report. University of Toronto; Toronto, ON: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Seth P, Scholl L, Rudd RA, Bacon S. Overdose deaths involving opioids, cocaine, and psychostimulants - United States, 2015–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:349–358. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6712a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A, Kelly SM, Mitchell SG, Gryczynski J, O’Grady KE, Schwartz RP. Update on barriers to pharmacotherapy for opioid use disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19:35. doi: 10.1007/s11920-017-0783-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socias ME, Ahamad K. An urgent call to increase access to evidence-based opioid agonist therapy for prescription opioid use disorders. CMAJ. 2016;188:1208–1209. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.160554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socias ME, Shannon K, Montaner JS, Guillemi S, Dobrer S, Nguyen P, Goldenberg S, Deering K. Gaps in the hepatitis C continuum of care among sex workers in Vancouver, British Columbia: Implications for voluntary hepatitis C virus testing, treatment and care. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;29:411–416. doi: 10.1155/2015/381870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socias ME, Volkow N, Wood E. Adopting the ‘cascade of care’ framework: An opportunity to close the implementation gap in addiction care? Addiction. 2016;111:2079–2081. doi: 10.1111/add.13479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socias ME, Wood E, McNeil R, Kerr T, Dong H, Shoveller J, Montaner J, Milloy MJ. Unintended impacts of regulatory changes to British Columbia Methadone Maintenance Program on addiction and HIV-related outcomes: An interrupted time series analysis. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;45:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, Indave BI, Degenhardt L, Wiessing L, Ferri M, Pastor-Barriuso R. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2017;357:j1550. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Palepu A, Cornelisse PG, Yip B, O’Shaughnessy MV, Montaner JS, Schechter MT, Hogg RS. Barriers to use of free antiretroviral therapy in injection drug users. JAMA. 1998;280:547–549. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.6.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teruya C, Schwartz RP, Mitchell SG, Hasson AL, Thomas C, Buoncristiani SH, Hser YI, Wiest K, Cohen AJ, Glick N, Jacobs P, McLaughlin P, Ling W. Patient perspectives on buprenorphine/naloxone: A qualitative study of retention during the starting treatment with agonist replacement therapies (START) study. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2014;46:412–426. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2014.921743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timko C, Schultz NR, Cucciare MA, Vittorio L, Garrison-Diehn C. Retention in medication-assisted treatment for opiate dependence: A systematic review. J Addict Dis. 2016;35:22–35. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2016.1100960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AR, Nunes E, Olfson M. To battle the opioid overdose epidemic, deploy the ‘cascade of care’ model. Health Affairs Blog. 2017 https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/catalog/ac:m37pvmcvgf.

- Wood E, Hogg RS, Lima VD, Kerr T, Yip B, Marshall BD, Montaner JS. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and survival in HIV-infected injection drug users. JAMA. 2008;300:550–554. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarborough BJ, Stumbo SP, McCarty D, Mertens J, Weisner C, Green CA. Methadone, buprenorphine and preferences for opioid agonist treatment: A qualitative analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;160:112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee A, Loh HS, Hisham Hashim HM, Ng CG. The prevalence of sexual dysfunction among male patients on methadone and buprenorphine treatments: A meta-analysis study. J Sex Med. 2014;11:22–32. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.