We investigated the prevalence of latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) among the residents in seven long-term care facilities (LTCFs) located in different regions of Taiwan and compared the performance of two interferon gamma release assays, i.e., QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube (QFT-GIT) and QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus (QFT-Plus) for screening LTBI. We also assessed the diagnostic performance against a composite reference standard (subjects with persistent-positive, transient-positive, and negative results from QFTs during reproducibility analysis were classified as definite, possible, and not LTBI, respectively).

KEYWORDS: latent tuberculosis infection, QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube, QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus, long-term care facilities, older adults

ABSTRACT

We investigated the prevalence of latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) among the residents in seven long-term care facilities (LTCFs) located in different regions of Taiwan and compared the performance of two interferon gamma release assays, i.e., QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube (QFT-GIT) and QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus (QFT-Plus) for screening LTBI. We also assessed the diagnostic performance against a composite reference standard (subjects with persistent-positive, transient-positive, and negative results from QFTs during reproducibility analysis were classified as definite, possible, and not LTBI, respectively). Two hundred forty-four residents were enrolled, and 229 subjects were included in the analysis. The median age was 80 years (range, 60 to 102 years old), and 117 (51.1%) were male. Among them, 66 (28.8%) and 74 (32.3%) subjects had positive results from QFT-GIT and QFT-Plus, respectively, and the results for 215 (93.9%) subjects showed agreement. Using the composite reference standard, 66 (28.8%), 11 (4.8%), and 152 (66.4%) were classified as definite, possible, and not LTBI, respectively. For definite LTBI, the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of QFT-GIT were 89.4%, 95.7%, 89.4%, and 95.7%, respectively, and those for QFT-Plus were 100.0%, 95.1%, 89.2%, and 100.0%, respectively. The sensitivity of QFT-GIT decreased gradually with patient age. Compared to QFT-GIT, QFT-Plus displayed significantly higher sensitivity (100.0% versus 89.4%, P = 0.013) and similar specificity (95.1% versus 95.7%). In conclusion, a high prevalence of LTBI was found among elders in LTCFs in Taiwan. The new QFT-Plus test demonstrated a higher sensitivity than QFT-GIT in the older adults in LTCFs.

INTRODUCTION

There are 10.4 million new cases of tuberculosis (TB), which is responsible for 1.4 million deaths annually worldwide and continues to pose a leading health problem (1). TB incidence in Taiwan has decreased over the last decade, but Taiwan is still a country with moderate TB incidence, with a TB incidence of 43.9 per 100,000 people in 2016 (2). In Taiwan, there is a high burden of TB in older adults (≥65 years old), who account for 12.9% of the Taiwanese population but represent 56.2% of all TB cases (3). TB incidence rates rise progressively with advancing age, from 54.8 per 100,000 in those aged 55 to 64, to 191.9 per 100,000 in those aged 65 and older (2). Hence, addressing the burden of TB in older adults is a public health priority.

One of the three pillars of the World Health Organization (WHO) End TB Strategy is TB prevention. An important component of TB prevention is the diagnosis and treatment of latent tuberculosis infections (LTBIs) in countries with a TB incidence <100:100,000, because a large proportion of TB cases in these countries is due to LTBI reactivation (3). Older adults residing in long-term care facilities (LTCFs) have rates of TB that are 2 to 3 times as high as those living in the community (4). Greater exposure, multiple comorbidities, malnutrition, and the waning immunity of older residents living in LTCFs contribute to an increased risk of progression from LTBI to active TB (5). Atypical and nonspecific symptoms of TB in older adults (6), especially in LTCF residents (7), also lead to delays in diagnosis (8) and increase the risk of transmission to close contacts (9). Targeted screening of populations at high risk of LTBI and those living in environments at high risk of spreading TB, such as LTCFs, homeless shelters, and correctional facilities, has been suggested for TB control by recent guidelines (10–12).

The tuberculin skin test (TST) and interferon gamma release assays (IGRAs) are commonly used LTBI screening tools (13). The TST is widely used and inexpensive (13). The American Thoracic Society, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the American Geriatric Society have recommended a two-step TST for LTBI screening at the time of admission to an LTCF (9, 14). Although the first TST can be falsely negative because of waning immunity or malnutrition, a two-step TST can help to improve the sensitivity by identifying false negatives (15). There are two commercially available IGRAs, i.e., the QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube (QFT-GIT) (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and the T-SPOT.TB (Oxford Immunotec, Abingdon, UK). IGRAs offer higher specificity than the TST in a bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG)-vaccinated population (16), and they are as sensitive as the TST for LTBI. Using IGRAs could potentially simplify testing practices and obviate follow-ups to the TST. However, IGRAs have reduced sensitivity in children and immunocompromised subjects, such as HIV-infected individuals (16).

The newest generation of QFT-GIT, QuantiFERON-TB Plus (QFT-Plus), was developed recently (17). QFT-Plus has two TB antigen tubes: TB antigen tube 1 (TB1) and TB antigen tube 2 (TB2). TB1 contains peptides from ESAT-6 and CFP-10 (TB-7.7 present in QFT-GIT has been removed), which are designed to elicit an immune response from CD4+ T-helper lymphocytes. TB2 contains an additional set of peptides targeted for a cell-mediated immune response from CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Previous studies found higher Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific CD8+ T-cell responses in active tuberculosis disease (18) and in those with recent M. tuberculosis exposure (19); therefore, QFT-Plus was expected to improve the sensitivity, especially in immunocompromised populations.

As the proportion of Taiwanese adults aged ≥65 years continues to expand, there is a need to diagnose LTBI and prevent TB in older adults, particularly those living in LTCFs. The performance and test variability of this new generation IGRA among older adults in LTCFs remains uncertain. Therefore, our primary objective was to investigate the prevalence of LTBI and its associated factors among older adults in LTCFs. We also aimed to evaluate the performance and test the variability of QFT-GIT and QFT-Plus, using direct comparisons and reproducibility analyses in this setting.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects and setting.

This study was conducted between January and July 2017 among seven LTCFs in Taiwan (one in northern, five in southern, and one in eastern Taiwan). The target population for this study was old residents (≥60 years) without histories of TB. After signing the consent form, the demographic data, comorbidity status, and BCG vaccination status (presence of BCG scar or not) were collected. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Kaohsiung Medical University, Chung-Ho Memorial Hospital [KMUHIRB-SV (I)-20160057].

Laboratory study.

The participants' blood samples were tested by two IGRA methods: QFT-GIT and QFT-Plus (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Blood samples were collected in lithium heparin tubes by trained staffs. The blood samples were stored in a box at room temperature and transported to the central laboratory at National Taiwan University Hospital within 8 h. The test results were interpreted according to the manufacturer's criteria (cutoff level, 0.35 IU/ml), and a positive result observed in the antigen tube in QFT-GIT or one of the single antigen tubes (TB1 or TB2) in QFT-Plus was interpreted as a positive result.

Reproducibility analysis and composite reference standard.

In the absence of a gold-standard test for LTBI against which to compare test accuracy, the results from a reproducibility analysis were used as surrogate reference standards. Blood sampling was repeated within 2 weeks if participants had a positive or indeterminate test result in at least one of the two IGRAs. If the repeated test was negative or indeterminate, a third test was performed within 2 weeks. A composite reference standard was defined from subjects with at least two positive results, transient-positive results, and negative results of either the QFT-GIT or QFT-Plus test classified as “definite,” “possible,” and “not” LTBI, respectively.

Statistical analysis.

Categorical variables were compared using a chi-square test or Fisher's exact test, where appropriate, and differences in continuous variables were analyzed using a Student's t test. The data are presented as numbers (percentages), means ± standard deviations, or percentages (95% confidence intervals) unless otherwise noted. The statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 12 software (StataCorp LLC, TX, USA). Two-sided P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

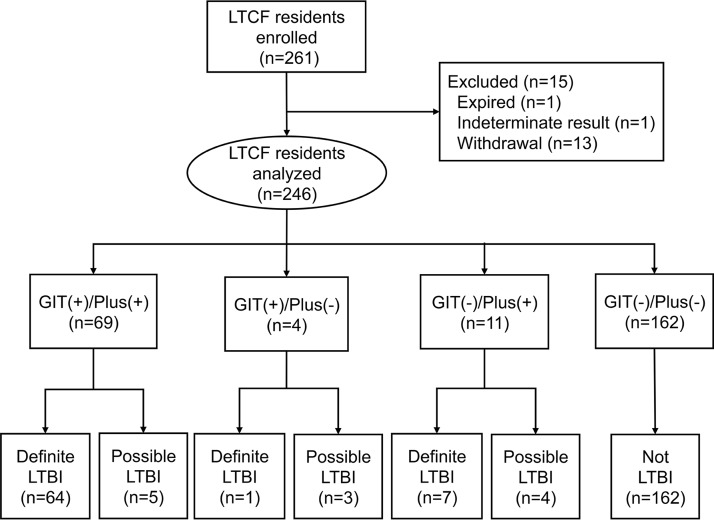

We enrolled 244 residents in seven long-term care facilities between January and July 2017 in northern, southern, and eastern Taiwan. Fifteen (6.1%) were excluded from the analysis (one died, 13 withdrew from the study, and one had persistent indeterminate QFT results) (Fig. 1). The remaining 229 (93.9%) subjects had a median age of 80 (60 to 102) years, of which 117 (51.1%) were male (Fig. 1 and Table 1).

FIG 1.

Flow diagram of the study participants.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of enrolled subjects according to results obtained from QFT-GIT and QFT-Plus

| Characteristic | No. of patients | QFT-GITa |

QFT-Plusb, no. (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) |

P value | No. (%) |

P value | No.(%) of positive results in: |

|||||

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | TB1 | TB2 | ||||

| Age (yr) | 0.251 | 0.924 | |||||||

| 60–64 | 9 | 5 (55.6) | 4 (44.4) | 3 (33.3) | 6 (66.7) | 3 (33.3) | 3 (33.3) | ||

| 65–74 | 34 | 11 (32.4) | 23 (67.6) | 11 (32.4) | 23 (67.6) | 11 (32.4) | 10 (29.4) | ||

| 75–84 | 108 | 31 (28.7) | 77 (71.3) | 37 (34.3) | 71 (65.7) | 26 (24.1) | 36 (33.3) | ||

| ≥85 | 78 | 19 (24.4) | 59 (75.6) | 23 (29.5) | 55 (70.5) | 21 (26.9) | 20 (25.6) | ||

| Sex | 0.382 | 0.159 | |||||||

| Female | 112 | 29 (25.9) | 83 (74.1) | 31 (27.7) | 81 (72.3) | 29 (25.9) | 29 (25.9) | ||

| Male | 117 | 37 (31.6) | 80 (68.4) | 43 (36.8) | 74 (63.2) | 32 (27.4) | 40 (34.2) | ||

| Body mass index | 0.248 | 0.124 | |||||||

| <18.5 | 52 | 11 (21.2) | 41 (78.8) | 13 (25.0) | 39 (75.0) | 10 (19.2) | 13 (25.0) | ||

| 18.5–24 | 117 | 39 (33.3) | 78 (66.7) | 45 (38.5) | 72 (61.5) | 37 (31.6) | 40 (34.2) | ||

| >24 | 60 | 16 (26.7) | 44 (73.3) | 16 (26.7) | 44 (73.3) | 14 (23.3) | 16 (26.7) | ||

| Smoking | 0.318 | 0.381 | |||||||

| Never | 168 | 47 (28.0) | 121 (72.0) | 51 (30.4) | 117 (69.6) | 43 (25.6) | 47 (28.0) | ||

| Ever | 51 | 14 (27.5) | 37 (72.5) | 18 (35.3) | 33 (64.7) | 14 (27.5) | 17 (33.3) | ||

| Current | 10 | 5 (50.0) | 5 (50.0) | 5 (50.0) | 5 (50.0) | 4 (40.0) | 5 (50.0) | ||

| Barthel index | 0.322 | 0.585 | |||||||

| <40 | 101 | 24 (23.8) | 77 (76.2) | 29 (28.7) | 72 (71.3) | 22 (21.8) | 27 (26.7) | ||

| 41–59 | 51 | 17 (33.3) | 34 (66.7) | 18 (35.3) | 33 (64.7) | 16 (31.4) | 17 (33.3) | ||

| >60 | 77 | 25 (32.5) | 52 (67.5) | 27 (35.1) | 50 (64.9) | 23 (29.9) | 25 (32.5) | ||

| BCG vaccination | 0.659 | 1.000 | |||||||

| No | 96 | 26 (27.1) | 70 (72.9) | 31 (32.3) | 65 (67.7) | 25 (26.0) | 30 (31.3) | ||

| Yes | 133 | 40 (30.1) | 93 (69.9) | 43 (32.3) | 90 (67.7) | 36 (27.1) | 39 (29.3) | ||

| Comorbidities | |||||||||

| Hypertension | 0.050 | 0.109 | |||||||

| No | 87 | 32 (36.8) | 55 (63.2) | 34 (39.1) | 53 (60.9) | 27 (31.0) | 32 (36.8) | ||

| Yes | 142 | 34 (23.9) | 108 (76.1) | 40 (28.2) | 102 (71.8) | 34 (23.9) | 37 (26.1) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.119 | 0.096 | |||||||

| No | 155 | 50 (32.3) | 105 (67.7) | 56 (36.1) | 99 (63.9) | 45 (29.0) | 53 (34.2) | ||

| Yes | 74 | 16 (21.6) | 58 (78.4) | 18 (24.3) | 56 (75.7) | 16 (21.6) | 16 (21.6) | ||

| Dementia | 1.000 | 0.639 | |||||||

| No | 165 | 48 (29.1) | 117 (70.9) | 55 (33.3) | 110 (66.7) | 44 (26.7) | 51 (30.9) | ||

| Yes | 64 | 18 (28.1) | 46 (71.9) | 19 (29.7) | 45 (70.3) | 17 (26.6) | 18 (28.1) | ||

| Cerebral vascular accident | 0.351 | 0.452 | |||||||

| No | 154 | 41 (26.6) | 113 (73.4) | 47 (30.5) | 107 (69.5) | 40 (26.0) | 43 (27.9) | ||

| Yes | 75 | 25 (33.3) | 50 (66.7) | 27 (36.0) | 48 (64.0) | 21 (28.0) | 26 (34.7) | ||

| Heart disease | 0.448 | 0.581 | |||||||

| No | 188 | 52 (27.7) | 136 (72.3) | 59 (31.4) | 129 (68.6) | 48 (25.5) | 54 (28.7) | ||

| Yes | 41 | 14 (34.1) | 27 (65.9) | 15 (36.6) | 26 (63.4) | 13 (31.7) | 15 (36.6) | ||

| Parkinsonism | 1.000 | 0.620 | |||||||

| No | 210 | 61 (29.0) | 149 (71.0) | 69 (32.9) | 141 (67.1) | 57 (27.1) | 64 (30.5) | ||

| Yes | 19 | 5 (26.3) | 14 (73.7) | 5 (26.3) | 14 (73.7) | 4 (21.1) | 5 (26.3) | ||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 0.762 | ||||||||

| No | 215 | 63 (29.3) | 152 (70.7) | 70 (32.6) | 145 (67.4) | 58 (27.0) | 65 (30.2) | ||

| Yes | 14 | 3 (21.4) | 11 (78.6) | 4 (28.6) | 10 (71.4) | 3 (21.4) | 4 (28.6) | ||

| Other | 0.338 | 0.540 | |||||||

| No | 161 | 43 (26.7) | 118 (73.3) | 50 (31.1) | 111 (68.9) | 42 (26.1) | 45 (28.0) | ||

| Yes | 68 | 23 (33.8) | 45 (66.2) | 24 (35.3) | 44 (64.7) | 19 (27.9) | 24 (35.3) | ||

| Laboratory tests | |||||||||

| HbA1C (%) | 0.701 | 0.353 | |||||||

| <6.5 | 189 | 56 (29.6) | 133 (70.4) | 64 (33.9) | 125 (66.1) | 52 (27.5) | 60 (31.7) | ||

| ≥6.5 | 40 | 10 (25.0) | 30 (75.0) | 10 (25.0) | 30 (75.0) | 9 (22.5) | 9 (22.5) | ||

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.833 | 1.000 | |||||||

| <1.5 | 199 | 57 (28.6) | 142 (71.4) | 64 (32.2) | 135 (67.8) | 54 (27.1) | 59 (29.6) | ||

| ≥1.5 | 30 | 9 (30.0) | 21 (70.0) | 10 (33.3) | 20 (66.7) | 7 (23.3) | 10 (33.3) | ||

| Alanine transaminase (U/liter) | 0.784 | 0.592 | |||||||

| <35 | 212 | 62 (29.2) | 150 (70.8) | 70 (33.0) | 142 (67.0) | 57 (26.9) | 65 (30.7) | ||

| ≥35 | 17 | 4 (23.5) | 13 (76.5) | 4 (23.5) | 13 (76.5) | 4 (23.5) | 4 (23.5) | ||

| Albumin (g/dl) | 0.177 | 0.514 | |||||||

| <3.5 | 57 | 12 (21.1) | 45 (78.9) | 16 (28.1) | 41 (71.9) | 12 (21.1) | 15 (26.3) | ||

| ≥3.5 | 172 | 54 (31.4) | 118 (68.6) | 58 (33.7) | 114 (66.3) | 49 (28.5) | 54 (31.4) | ||

QFT-GIT, QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube.

QFT-Plus, QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus.

Of the 229 enrolled participants, 66 (28.8%) showed positive QFT-GIT test results and 163 (71.2%) showed negative results. Meanwhile, 74 (32.3%) subjects tested positive by the QFT-Plus test, whereas 155 (67.7%) tested negative. For the QFT-Plus test, 56 (24.5%) of 229 subjects were positive by both TB1 and TB2, five (2.2%) were positive by TB1 only, and 13 (5.7%) were positive by TB2 only. The demographic data, comorbidity, and laboratory results were similar among subjects with or without positive result in QFTs (Table 2). The head-to-head comparison between the QFT-GIT and the QFT-Plus results showed agreement in 215 (93.9%) subjects (63 tested positive with both, and 152 tested negative; kappa value = 0.86, P < 0.001). Eleven (4.8%) patients showed positive results only in the QFT-Plus test (four were positive by TB1 only, five were positive by TB2 only, and two were positive by TB1 and TB2), and three (1.3%) patients were QFT-GIT positive but QFT-Plus negative (Fig. 1).

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of enrolled subjects according to composite reference standard

| Characteristic | No. of patients | No. (%) of patients |

P value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definite LTBIa with positive results by: |

Possible LTBI with positive results by: |

Not LTBI (n = 152) | |||||||

| QFT-GITb and QFT-Plusc (n = 53) | QFT-GIT only (n = 3) | QFT-Plus only (n = 10) | QFT-GIT and QFT-Plus (n = 4) | QFT-GIT only (n = 3) | QFT-Plus only (n = 4) | ||||

| Age (yr) | 0.001 | ||||||||

| 60–64 | 9 | 3 (33.3) | 2 (22.2) | 4 (44.4) | |||||

| 65–74 | 34 | 9 (26.5) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (2.9) | 22 (64.7) | |||

| 75–84 | 108 | 24 (22.2) | 2 (1.9) | 4 (3.7) | 3 (2.8) | 4 (3.7) | 71 (65.7) | ||

| ≥85 | 78 | 17 (21.8) | 5 (6.4) | 1 (1.3) | 55 (70.5) | ||||

| Sex | 0.561 | ||||||||

| Female | 112 | 24 (21.4) | 2 (1.8) | 3 (2.7) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (1.8) | 1 (0.9) | 79 (70.5) | |

| Male | 117 | 29 (24.8) | 1 (0.9) | 7 (6.0) | 3 (2.6) | 1 (0.9) | 3 (2.6) | 73 (62.4) | |

| Body mass index | 0.807 | ||||||||

| <18.5 | 52 | 10 (19.2) | 2 (3.8) | 1 (1.9) | 39 (75.0) | ||||

| 18.5–24 | 117 | 31 (26.5) | 2 (1.7) | 6 (5.1) | 3 (2.6) | 2 (1.7) | 3 (2.6) | 70 (59.8) | |

| >24 | 60 | 12 (20.0) | 1 (1.7) | 2 (3.3) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.7) | 43 (71.7) | ||

| Smoking | 0.644 | ||||||||

| Never | 168 | 38 (22.6) | 2 (1.2) | 6 (3.6) | 2 (1.2) | 3 (1.8) | 3 (1.8) | 114 (67.9) | |

| Ever | 51 | 11 (21.6) | 1 (2.0) | 4 (7.8) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) | 33 (64.7) | ||

| Current | 10 | 4 (40.0) | 1 (10.0) | 5 (50.0) | |||||

| Barthel index | 0.742 | ||||||||

| <40 | 101 | 20 (19.8) | 1 (1.0) | 4 (4.0) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) | 3 (3.0) | 71 (70.3) | |

| 41–59 | 51 | 14 (27.5) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.0) | 2 (3.9) | 33 (64.7) | |||

| >60 | 77 | 19 (24.7) | 1 (1.3) | 5 (6.5) | 1 (1.3) | 2 (2.6) | 1 (1.3) | 48 (62.3) | |

| BCG vaccination | 0.631 | ||||||||

| No | 96 | 21 (21.9) | 1 (1.0) | 6 (6.3) | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.0) | 65 (67.7) | ||

| Yes | 133 | 32 (24.1) | 2 (1.5) | 4 (3.0) | 2 (1.5) | 3 (2.3) | 3 (2.3) | 87 (65.4) | |

| Comorbidities | |||||||||

| Hypertension | 0.392 | ||||||||

| No | 87 | 26 (29.9) | 1 (1.1) | 5 (5.7) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.3) | 1 (1.1) | 51 (58.6) | |

| Yes | 142 | 27 (19.0) | 2 (1.4) | 5 (3.5) | 3 (2.1) | 1 (0.7) | 3 (2.1) | 101 (71.1) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.757 | ||||||||

| No | 155 | 40 (25.8) | 2 (1.3) | 8 (5.2) | 3 (1.9) | 2 (1.3) | 3 (1.9) | 97 (62.6) | |

| Yes | 74 | 13 (17.6) | 1 (1.4) | 2 (2.7) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) | 55 (74.3) | |

| Dementia | 0.393 | ||||||||

| No | 165 | 37 (22.4) | 3 (1.8) | 10 (6.1) | 3 (1.8) | 2 (1.2) | 2 (1.2) | 108 (65.5) | |

| Yes | 64 | 16 (25.0) | 1 (1.6) | 1 (1.6) | 2 (3.1) | 44 (68.8) | |||

| Cerebral vascular accident | 0.959 | ||||||||

| No | 154 | 33 (21.4) | 2 (1.3) | 7 (4.5) | 3 (1.9) | 2 (1.3) | 2 (1.3) | 105 (68.2) | |

| Yes | 75 | 20 (26.7) | 1 (1.3) | 3 (4.0) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.3) | 2 (2.7) | 47 (62.7) | |

| Heart disease | 0.066 | ||||||||

| No | 188 | 42 (22.3) | 3 (1.6) | 9 (4.8) | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.6) | 4 (2.1) | 126 (67.0) | |

| Yes | 41 | 11 (26.8) | 1 (2.4) | 3 (7.3) | 26 (63.4) | ||||

| Parkinsonism | 0.764 | ||||||||

| No | 210 | 49 (23.3) | 3 (1.4) | 10 (4.8) | 3 (1.4) | 3 (1.4) | 4 (1.9) | 138 (65.7) | |

| Yes | 19 | 4 (21.1) | 1 (5.3) | 14 (73.7) | |||||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | |||||||||

| No | 215 | 50 (23.3) | 3 (1.4) | 10 (4.7) | 4 (1.9) | 3 (1.4) | 3 (1.4) | 142 (66.0) | |

| Yes | 14 | 3 (21.4) | 1 (7.1) | 10 (71.4) | |||||

| Other | 0.457 | ||||||||

| No | 161 | 36 (22.4) | 1 (0.6) | 9 (5.6) | 2 (1.2) | 2 (1.2) | 2 (1.2) | 109 (67.7) | |

| Yes | 68 | 17 (25.0) | 2 (2.9) | 1 (1.5) | 2 (2.9) | 1 (1.5) | 2 (2.9) | 43 (63.2) | |

| Laboratory tests | |||||||||

| HbA1C (%) | 0.260 | ||||||||

| <6.5 | 189 | 46 (24.3) | 2 (1.1) | 9 (4.8) | 4 (2.1) | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.6) | 124 (65.6) | |

| ≥6.5 | 40 | 7 (17.5) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (2.5) | 2 (5.0) | 1 (2.5) | 28 (70.0) | ||

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | |||||||||

| <1.5 | 199 | 47 (23.6) | 3 (1.5) | 9 (4.5) | 2 (1.0) | 3 (1.5) | 3 (1.5) | 132 (66.3) | |

| ≥1.5 | 30 | 6 (20.0) | 1 (3.3) | 2 (6.7) | 1 (3.3) | 20 (66.7) | |||

| Alanine transaminase (U/liter) | 0.378 | ||||||||

| <35 | 212 | 49 (23.1) | 3 (1.4) | 10 (4.7) | 4 (1.9) | 3 (1.4) | 4 (1.9) | 139 (65.6) | |

| ≥35 | 17 | 4 (23.5) | 13 (76.5) | ||||||

| Albumin (g/dl) | 0.402 | ||||||||

| <3.5 | 57 | 10 (17.5) | 2 (3.5) | 2 (3.5) | 2 (3.5) | 41 (71.9) | |||

| ≥3.5 | 172 | 43 (25.0) | 3 (1.7) | 8 (4.7) | 2 (1.2) | 3 (1.7) | 2 (1.2) | 111 (64.5) | |

LTBI, latent TB infection.

QFT-GIT, QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube.

QFT-Plus, QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus.

For 77 subjects with any positive QFT results (either QFT-GIT or QFT-Plus positive), the tests were repeated within 2 weeks to evaluate the reproducibility (Table 2). Among 66 subjects with initially positive QFT-GIT, 15 were reversed to negative, yielding a reversion rate of 22.7%. Among those 15 subjects with reversion in QFT-GIT, 5 (33.3%) were converted to positive after a third test, producing a final total of 56 (84.8%) stable positives and 10 (15.2%) transient positives (permanent reversion). Meanwhile, among 74 subjects who tested positive with QFT-Plus initially, 16 were reversed to negative, yielding a reversion rate of 21.6%. Among those QFT-Plus reversion subjects, 5 (31.3%) were converted to positive after a third test, producing a final total of 63 (85.1%) stable positives and 11 (14.9%) transient positives (permanent reversion). According to the definition of the composite reference standard, 66 (28.8%), 11 (4.8%), and 152 (66.4%) subjects were classified as “definite,” “possible,” and “not” LTBI, respectively (Table 2).

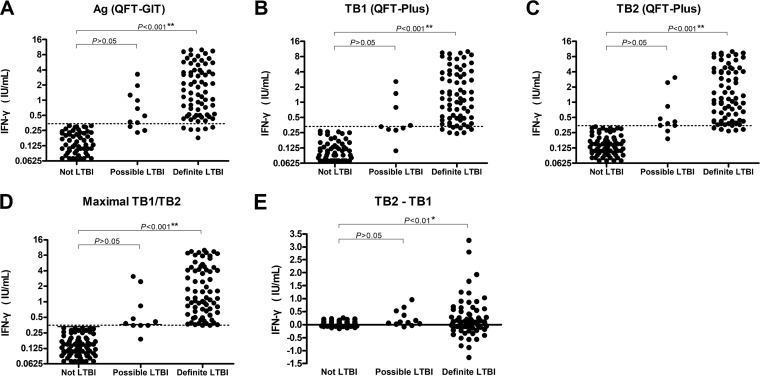

Among the 66 subjects with definite LTBI, 59 (89.4%) were positive by the QFT-GIT test and all (100.0%) were positive by the QFT-Plus test (53 had concomitant positives in TB1 and TB2, four were positive by TB1 only, and nine were positive by TB2 only). These findings resulted in a lower false-negative rate in the QFT-Plus test (n = 0, 0.0%) than the QFT-GIT test (n = 7, 10.6%) (P = 0.029) (Tables 3 and 4). Among the 11 subjects with possible LTBI, seven (63.6%) tested positive by the QFT-GIT test and eight (72.7%) tested positive by the QFT-Plus test (three positive by TB1 and TB2 and one and four had low interferon gamma levels close to the cutoff for TB1 only and TB2 only, respectively). Figure 2 shows subjects with definite LTBI had significantly higher interferon gamma levels than those without definite LTBI in the QFT-GIT test (2.63 ± 2.68 versus 0.10 ± 0.34 IU/ml, respectively, P < 0.001), TB1 (2.38 ± 2.67 versus 0.07 ± 0.26 IU/ml, respectively, P < 0.001) and TB2 (2.60 ± 2.79 versus 0.11 ± 0.33 IU/ml, respectively, P < 0.001), and higher values of TB2 minus TB1 (0.21 ± 0.72 versus 0.04 ± 0.12 IU/ml, respectively, P < 0.01). In contrast, the interferon gamma levels among subjects with possible LTBI were similar to those without LTBI.

TABLE 3.

Performance of QFT-GIT and QFT-Plus for definite LTBI according to different characteristicsa

| Characteristic | No. of patients |

Performance (% [95% confidence interval]) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definite LTBI and test result that was: |

Not definite LTBI and test result that was: |

||||||||

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Accuracy | |

| QFT-GITb | |||||||||

| All | 59 | 7 | 7 | 156 | 89.4 (79.4–95.6) | 95.7 (91.4–98.3) | 89.4 (79.4–95.6) | 95.7 (91.4–98.3) | 93.9 (90.0–96.6) |

| Age (yr) | |||||||||

| 60–64 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 100.0 (29.2–100.0) | 66.7 (22.3–95.7) | 60.0 (14.7–94.7) | 100.0 (39.8–100.0) | 77.8 (40.0–97.2) |

| 65–74 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 22 | 90.9 (58.7–99.8) | 95.7 (78.1–99.9) | 90.9 (58.7–99.8) | 95.7 (78.1–99.9) | 94.1 (80.3–99.3) |

| 75–84 | 28 | 2 | 3 | 75 | 93.3 (77.9–99.2) | 96.2 (89.2–99.2) | 90.3 (74.2–98.0) | 97.4 (90.9–99.7) | 95.4 (89.5–98.5) |

| ≥85 | 18 | 4 | 1 | 55 | 81.8 (59.7–94.8) | 98.2 (90.4–100.0) | 94.7 (74.0–99.9) | 93.2 (83.5–98.1) | 93.6 (85.7–97.9) |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 26 | 3 | 3 | 80 | 89.7 (72.6–97.8) | 96.4 (89.8–99.2) | 89.7 (72.6–97.8) | 96.4 (89.8–99.2) | 94.6 (88.7–98.0) |

| Male | 33 | 4 | 4 | 76 | 89.2 (74.6–97.0) | 95.0 (87.7–98.6) | 89.2 (74.6–97.0) | 95.0 (87.7–98.6) | 93.2 (87.0–97.0) |

| Albumin (g/dl) | |||||||||

| <3.5 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 43 | 83.3 (51.6–97.9) | 95.6 (84.9–99.5) | 83.3 (51.6–97.9) | 95.6 (84.9–99.5) | 93.0 (83.0–98.1) |

| ≥3.5 | 49 | 5 | 5 | 113 | 90.7 (79.7–96.9) | 95.8 (90.4–98.6) | 90.7 (79.7–96.9) | 95.8 (90.4–98.6) | 94.2 (89.6–97.2) |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | |||||||||

| <1.5 | 52 | 7 | 5 | 135 | 88.1 (77.1–95.1) | 96.4 (91.9–98.8) | 91.2 (80.7–97.1) | 95.1 (90.1–98.0) | 94.0 (89.7–96.8) |

| ≥1.5 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 21 | 100.0 (59.0–100.0) | 91.3 (72.0–98.9) | 77.8 (40.0–97.2) | 100.0 (83.9–100.0) | 93.3 (77.9–99.2) |

| HbA1C (%) | |||||||||

| <6.5 | 51 | 6 | 5 | 127 | 89.5 (78.5–96.0) | 96.2 (91.4–98.8) | 91.1 (80.4–97.0) | 95.5 (90.4–98.3) | 94.2 (89.8–97.1) |

| ≥6.5 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 29 | 88.9 (51.8–99.7) | 93.5 (78.6–99.2) | 80.0 (44.4–97.5) | 96.7 (82.8–99.9) | 92.5 (79.6–98.4) |

| Diabetes mellitus | |||||||||

| No | 45 | 5 | 5 | 100 | 90.0 (78.2–96.7) | 95.2 (89.2–98.4) | 90.0 (78.2–96.7) | 95.2 (89.2–98.4) | 93.5 (88.5–96.9) |

| Yes | 14 | 2 | 2 | 56 | 87.5 (61.7–98.4) | 96.6 (88.1–99.6) | 87.5 (61.7–98.4) | 96.6 (88.1–99.6) | 94.6 (86.7–98.5) |

| QFT-Plusc | |||||||||

| All | 66 | 0 | 8 | 155 | 100.0 (94.6–100.0) | 95.1 (90.6–97.9) | 89.2 (79.8–95.2) | 100.0 (97.6–100.0) | 96.5 (93.2–98.5) |

| Age (yr) | |||||||||

| 60–64 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 100.0 (29.2–100.0) | 100.0 (54.1–100.0) | 100.0 (29.2–100.0) | 100.0 (54.1–100.0) | 100.0 (66.4–100.0) |

| 65–74 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 100.0 (71.5–100.0) | 100.0 (85.2–100.0) | 100.0 (71.5–100.0) | 100.0 (85.2–100.0) | 100.0 (89.7–100.0) |

| 75–84 | 30 | 0 | 7 | 71 | 100.0 (88.4–100.0) | 91.0 (82.4–96.3) | 81.1 (64.8–92.0) | 100.0 (94.9–100.0) | 93.5 (87.1–97.4) |

| ≥85 | 22 | 0 | 1 | 55 | 100.0 (84.6–100.0) | 98.2 (90.4–100.0) | 95.7 (78.1–99.9) | 100.0 (93.5–100.0) | 98.7 (93.1–100.0) |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 29 | 0 | 2 | 81 | 100.0 (88.1–100.0) | 97.6 (91.6–99.7) | 93.5 (78.6–99.2) | 100.0 (95.5–100.0) | 98.2 (93.7–99.8) |

| Male | 37 | 0 | 6 | 74 | 100.0 (90.5–100.0) | 92.5 (84.4–97.2) | 86.0 (72.1–94.7) | 100.0 (95.1–100.0) | 94.9 (89.2–98.1) |

| Albumin (g/dl) | |||||||||

| <3.5 | 12 | 0 | 4 | 41 | 100.0 (73.5–100.0) | 91.1 (78.8–97.5) | 75.0 (47.6–92.7) | 100.0 (91.4–100.0) | 93.0 (83.0–98.1) |

| ≥3.5 | 54 | 0 | 4 | 114 | 100.0 (93.4–100.0) | 96.6 (91.5–99.1) | 93.1 (83.3–98.1) | 100.0 (96.8–100.0) | 97.7 (94.2–99.4) |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | |||||||||

| <1.5 | 59 | 0 | 5 | 135 | 100.0 (93.9–100.0) | 96.4 (91.9–98.8) | 92.2 (82.7–97.4) | 100.0 (97.3–100.0) | 97.5 (94.2–99.2) |

| ≥1.5 | 7 | 0 | 3 | 20 | 100.0 (59.0–100.0) | 87.0 (66.4–97.2) | 70.0 (34.8–93.3) | 100.0 (83.2–100.0) | 90.0 (73.5–97.9) |

| HbA1C (%) | |||||||||

| <6.5 | 57 | 0 | 7 | 125 | 100.0 (93.7–100.0) | 94.7 (89.4–97.8) | 89.1 (78.8–95.5) | 100.0 (97.1–100.0) | 96.3 (92.5–98.5) |

| ≥6.5 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 30 | 100.0 (66.4–100.0) | 96.8 (83.3–99.9) | 90.0 (55.5–99.7) | 100.0 (88.4–100.0) | 97.5 (86.8–99.9) |

| Diabetes mellitus | |||||||||

| No | 50 | 0 | 6 | 99 | 100.0 (92.9–100.0) | 94.3 (88.0–97.9) | 89.3 (78.1–96.0) | 100.0 (96.3–100.0) | 96.1 (91.8–98.6) |

| Yes | 16 | 0 | 2 | 56 | 100.0 (79.4–100.0) | 96.6 (88.1–99.6) | 88.9 (65.3–98.6) | 100.0 (93.6–100.0) | 97.3 (90.6–99.7) |

LTBI, latent TB infection.

QFT-GIT, QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube.

QFT-Plus, QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus.

TABLE 4.

Characteristics of subjects with discordant results obtained from QFT-GIT and QFT-Plus and classification of LTBI by composite reference standard

| No. | Sexa | Age (yr) | BMIb | Smoking history | Comorbidityc | QFT-GITd |

QFT-Pluse |

Classification of LTBIf | HbA1C (%) | Creatinine (mg/dl) | Alanine transaminase (U/liter) | Albumin/globulin (g/dl) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IFGg (IU/ml) | Result | IFG (IU/ml) |

Result | ||||||||||||

| TB1 | TB2 | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | F | 88 | 23.4 | Never | Hypertension | 0.28 | Negative | 0.35 | 0.28 | Positive | Definite | 5.7 | 0.9 | 6 | 4.5/3.9 |

| 2 | M | 77 | 27.6 | Past | Hypertension | 0.26 | Negative | 0.48 | 0.41 | Positive | Definite | 5.4 | 1 | 16 | 4.5/3.2 |

| 3 | M | 82 | 21.2 | Past | Heart disease | 0.18 | Negative | 0.33 | 0.62 | Positive | Definite | 6.8 | 0.7 | 12 | 4.0/3.1 |

| 4 | F | 91 | 22.8 | Never | Hypertension, CVA | 0.29 | Negative | 0.36 | 0.49 | Positive | Definite | 5.7 | 0.5 | 5 | 3.8/3.0 |

| 5 | M | 68 | 19.2 | Never | None | 0.26 | Negative | 0.39 | 0.29 | Positive | Definite | 4.9 | 0.8 | 14 | 3.5/3.7 |

| 6 | M | 88 | 19.7 | Past | Hypertension, DM | 0.27 | Negative | 0.44 | 0.29 | Positive | Definite | 5.6 | 0.9 | 23 | 3.2/3.9 |

| 7 | F | 88 | 15.9 | Never | DM | −0.1 | Negative | 0.29 | 0.39 | Positive | Definite | 5.8 | 0.3 | 14 | 3.4/4.0 |

| 8 | F | 81 | 22.9 | Never | Hypertension, DM, dementia | 0.3 | Negative | 0.35 | 0.27 | Positive | Possible | 7.8 | 1 | 10 | 3.5/2.7 |

| 9 | M | 76 | 15.2 | Past | COPD, dementia, CVA, hepatitis C, peptic ulcer | 0.23 | Negative | 0.29 | 0.35 | Positive | Possible | 5.9 | 0.7 | 10 | 3.0/4.4 |

| 10 | M | 83 | 19.2 | Never | Hypertension, CKD | 0.25 | Negative | 0.28 | 0.38 | Positive | Possible | 6.2 | 6.3 | 8 | 3.6/3.1 |

| 11 | M | 78 | 20.9 | Never | Hypertension, CVA, peptic ulcer | 0.02 | Negative | 0.05 | 0.41 | Positive | Possible | 5.2 | 0.5 | 4 | 3.2/3.8 |

| 12 | M | 61 | 20.6 | Never | Bipolar I disorder, CVA | 0.37 | Positive | −0.15 | −0.18 | Negative | Possible | 6.5 | 0.6 | 23 | 3.9/3.7 |

| 13 | F | 67 | 21.1 | Never | DM, dementia | 0.68 | Positive | 0.11 | 0.19 | Negative | Possible | 7.5 | 0.6 | 11 | 4.4/3.4 |

| 14 | F | 64 | 26.6 | Never | Hypertension | 1.95 | Positive | −0.77 | −0.1 | Negative | Possible | 5.7 | 0.6 | 6 | 3.8/3.6 |

M, male; F, female.

BMI, body mass index.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; DM, diabetes mellitus; CKD, chronic kidney disease.

QFT-GIT, QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube.

QFT-Plus, QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus.

LTBI, latent TB infection.

IFG, interferon gamma.

FIG 2.

Interferon gamma (IFN-γ) responses to stimulation with QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube (QFT-GIT) antigen (Ag) (A), QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus (QFT-Plus) antigens in TB1 (B) and TB2 (C), maximal levels of TB1/TB2 (D), and differences between TB1 and TB2 (TB2 minus TB1) (E) among definite, possible, and not latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) groups. A P value of <0.016 was considered significant after Bonferroni correction.

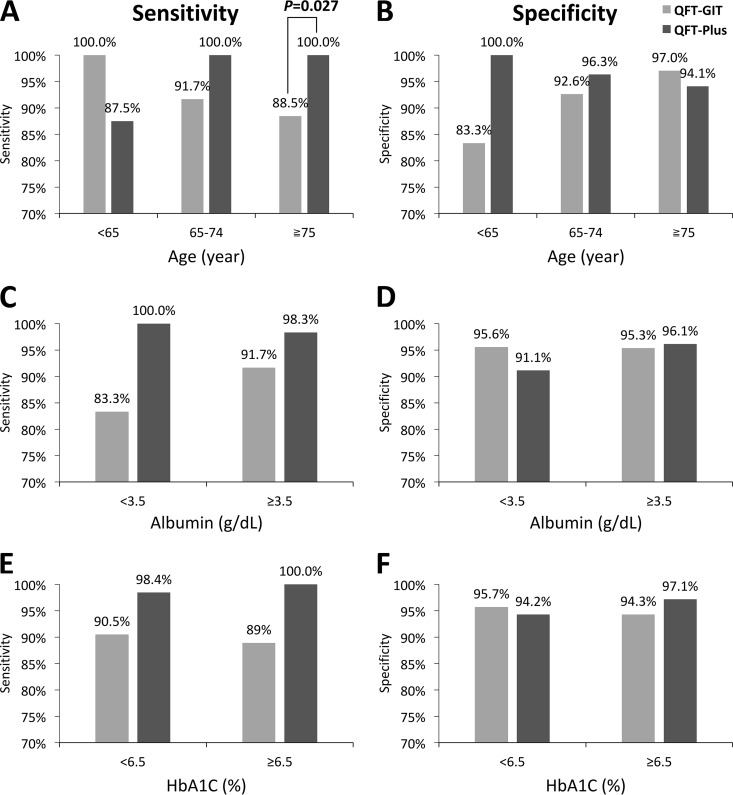

For definite LTBI, the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) of the QFT-GIT were 89.4%, 95.7%, 89.4%, and 95.7%, respectively, whereas the corresponding values for QFT-Plus were 100.0%, 95.1%, 89.2%, and 100.0% (Table 3). Compared with QFT-GIT, QFT-Plus had a higher sensitivity (100.0% versus 89.4%, P = 0.013) and similar specificity (95.1% versus. 95.7%, P = 1.000). The sensitivity of the QFT-GIT test decreased gradually with subject age, whereas the QFT-Plus test displayed a significantly higher sensitivity (100.0% versus 88.5%, P = 0.027) and similar specificity (94.0% versus 97.0%) among subjects aged ≥75 years (Fig. 3).

FIG 3.

Sensitivities and specificities of QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube (QFT-GIT) and QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus (QFT-Plus) for definite latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) according to age, albumin, and HbA1C levels.

DISCUSSION

This study is, to our knowledge, the first to determine the prevalence of LTBI among residents in LTCFs. We found an overall prevalence of definite LTBI in 28.8% of older adults (60 to 102 years old) in LTCFs. The sensitivity of QFT-GIT was shown to decrease with subject age, and the QFT-Plus test had a higher sensitivity than the QFT-GIT test, with similar specificity, especially among the older participants (≥75 years).

Among older adults, most TB cases came from the reactivation of LTBI rather than a recent transmission (20, 21). An accurate diagnosis of LTBI in older adults is critical, because residents in LTCFs often have poorer outcomes during TB treatment and are more likely to be diagnosed with TB after death (7). Older adults are also at the highest risk of LTBI, because they are more likely to be exposed to TB during their lifetime and live through a time with high TB prevalence. The finding that 28.8% of older residents were positive for LTBI is important because of the likelihood that many LTCF residents have comorbidities associated with the reactivation of LTBI (11). These include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal failure, diabetes mellitus, steroid use, and frailty conditions. The high prevalence of LTBI may reflect the high proportion of elderly populations in the selected LTCFs, which included 47.2% aged 75 to 84 years and 34.1% aged >85 years. Therefore, LTCFs need to have a process for follow-up of residents who are identified with a positive QFT test result. Residents with positive QFTs should have a comprehensive medical examination, including chest radiograph to rule out active TB, before being offered LTBI treatment. Documented LTBI status also enables a consideration of TB in differential diagnoses for patients who exhibit nonspecific TB symptoms (e.g., cough, sputum production, weight loss, or fever).

Although previous studies have shown that the sensitivity of TSTs, but not IGRAs, may diminish with patient age (4, 22), in this study, we found that the sensitivity of the QFT-GIT test could decrease with age, but that of the QFT-Plus test did not. TB1 contains long peptides and is designed to elicit a CD4+ T-cell response, whereas TB2 contains long peptides with additional short peptides for CD8+ T cells and is designed to elicit both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses (23). The difference between these tubes might provide a surrogate marker of the magnitude of the CD8+ T-cell responses. Barcellini and his colleagues first found that this difference was higher in smear-positive than in smear-negative active TB patients (17) and may indicate a higher magnitude of CD8+ T-cell responses in smear-positive TB individuals (24). By stratifying the TB1 and TB2 results, Petruccioli et al. found that the majority of LTBI subjects simultaneously responded to both TB1 and TB2 antigens, and that an “only to TB2” response was associated with active TB (23). However, in our study among older adults in LTCFs, we found 13 (5.7%) residents who had an “only to TB2” response, and most of them (n = 9, 69.2%) were categorized as definite LTBI. After extensive radiology and sputum examination, no active tuberculosis was found. This finding is consistent with the finding by cytometry that CD8+ T cells induced by TB2 are found in 11% of LTBIs (25). Furthermore, positive TB2 test results significantly increased the sensitivity of QFT-Plus, from 86.4% to 100.0% (P = 0.004), leading to a higher overall sensitivity than that of QFT-GIT (100.0% versus 89.4%, respectively, P = 0.003).

Previous studies have found that IGRAs tend to have a high variability with high rates of conversions and reversions in serial testing (26). The elevated test variability leads to uncertainty over whether the positive result is “transient” or “stable,” with treatment being beneficial to those subjects with transient-positive QFTs. Using a reproducibility analysis by repeated testing within 1 month, we found a reversion rate of 21.6% for QFT-Plus, which was similar to the reversion rate of 22.7% for QFT-GIT. Furthermore, 33.3% and 31.3% of reversions for QFT-GIT and QFT-Plus showed positive conversions for the third test, yielding a similar permanent reversion rate for both QFTs (15.2% versus 14.9% for QFT-GIT and QFT-Plus, respectively) and a similar transient reversion rate (7.6% versus 6.8% for QFT-GIT and QFT-Plus, respectively).

The high rate of reversion might be caused by the transient-positive results in QFTs. Among 11 subjects with transient-positive QFTs results (possible LTBI), we found seven (63.6%) who were transient positive by QFT-GIT, and four (36.3%) subjects who tested as transient positive in TB1. This might indicate that removing the TB7.7 antigen from TB1 slightly improves the specificity of TB1, which is consistent with recent findings in Japan (27). However, there were seven (63.6%) subjects with transient-positive results in TB2, showing that the specificity of the QFT-Plus test was slightly compromised. With the improved specificity of TB1 and improved sensitivity but slightly less specificity in TB2, the QFT-Plus test had a better overall sensitivity than QFT-GIT, with similar specificity. For definite LTBI prediction, QFT-Plus had a similar PPV as QFT-GIT (89.2% versus 89.4%, respectively, P = 1.000) but better NPV (100.0% versus 95.7%, respectively, P = 0.015).

Without serial tests in subjects with concomitant QFT-GIT and QFT-Plus negative results, we could not determine the conversion rate of our study population. However, we used a reproducibility analysis to assess the rates of transient- and stable-positive results, clarifying the testing variability and performance for predicting stable-positive results, which might indicate true LTBI.

The high prevalence of LTBI noted in LTCF residents suggests that testing upon admission for all LTCF residents may be warranted from a public health standpoint. The high prevalence of LTBI in these LTCFs also underscores the growing need to address whether to treat such individuals for their own health as well as for the benefit of other LTCF residents. The American Thoracic Society and CDC guidelines state that high-risk individuals diagnosed with LTBI should be offered prophylactic treatment “irrespective of age” (28). Despite this, the concern about isoniazid-associated hepatotoxicity in older adults (29), as well as less experience and comfort with LTBI treatment regimens, contributed to lower rates of LTBI treatment in LTCFs (30). As LTBI treatment regimens become shorter and present fewer adverse effects (31), the opportunities for preventing TB and its transmission among older adults with LTBIs will be substantial.

In conclusion, we found a high prevalence (28.8%) of definite LTBI (stable-positive QFTs) among residents in LTCFs, with the new QFT-Plus test demonstrating an improved sensitivity in older adults with a specificity of approximately 95%.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Executive Yuan, Taiwan (MOHW106-CDC-C-114-000101).

We declare no conflicts of interest and have no association with Qiagen.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. 2016. Global tuberculosis report 2016. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control. 2017. Statistics of communicable diseases and surveillance report 2016. Centers for Disease Control, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taipei, Taiwan. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lönnroth K, Migliori GB, Abubakar I, D'Ambrosio L, de Vries G, Diel R, Douglas P, Falzon D, Gaudreau MA, Goletti D, González Ochoa ER, LoBue P, Matteelli A, Njoo H, Solovic I, Story A, Tayeb T, van der Werf MJ, Weil D, Zellweger JP, Abdel Aziz M, Al Lawati MR, Aliberti S, Arrazola de Oñate W, Barreira D, Bhatia V, Blasi F, Bloom A, Bruchfeld J, Castelli F, Centis R, Chemtob D, Cirillo DM, Colorado A, Dadu A, Dahle UR, De Paoli L, Dias HM, Duarte R, Fattorini L, Gaga M, Getahun H, Glaziou P, Goguadze L, Del Granado M, Haas W, Järvinen A, Kwon GY, Mosca D, Nahid P, et al. . 2015. Towards tuberculosis elimination: an action framework for low-incidence countries. Eur Respir J 45:928–952. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00214014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hochberg NS, Horsburgh CR Jr. 2013. Prevention of tuberculosis in older adults in the United States: obstacles and opportunities. Clin Infect Dis 56:1240–1247. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stead WW. 1998. Tuberculosis among elderly persons, as observed among nursing home residents. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2(9 Suppl 1):S64–S70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Negin J, Abimbola S, Marais BJ. 2015. Tuberculosis among older adults–time to take notice. Int J Infect Dis 32:135–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chitnis AS, Robsky K, Schecter GF, Westenhouse J, Barry PM. 2015. Trends in tuberculosis cases among nursing home residents, California, 2000 to 2009. J Am Geriatr Soc 63:1098–1104. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan CH, Woo J, Or KK, Chan RC, Cheung W. 1995. The effect of age on the presentation of patients with tuberculosis. Tuber Lung Dis 76:290–294. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8479(05)80026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Advisory Committee for Elimination of Tuberculosis. 1990. Prevention and control of tuberculosis in facilities providing long-term care to the elderly Recommendations of the Advisory Committee for Elimination of Tuberculosis. MMWR Recomm Rep 39(RR-10):7–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Thoracic Society. 2000. Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. American Thoracic Society. MMWR Recomm Rep 49(RR-6):1–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horsburgh CR Jr, Rubin EJ. 2011. Clinical practice. Latent tuberculosis infection in the United States. N Engl J Med 364:1441–1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Thoracic Society, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2000. Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society was adopted by the ATS Board of Directors, July 1999. This is a Joint Statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). This statement was endorsed by the Council of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. (IDSA), September 1999, and the sections of this statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 161(4 Pt 2):S221–S247. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.supplement_3.ats600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Getahun H, Matteelli A, Chaisson RE, Raviglione M. 2015. Latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. N Engl J Med 372:2127–2135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1405427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finucane TE. 1988. The American Geriatrics Society statement on two-step PPD testing for nursing home patients on admission. J Am Geriatr Soc 36:77–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1988.tb03438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slutkin G, Perez-Stable EJ, Hopewell PC. 1986. Time course and boosting of tuberculin reactions in nursing home residents. Am Rev Respir Dis 134:1048–1051. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.134.5.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sester M, Sotgiu G, Lange C, Giehl C, Girardi E, Migliori GB, Bossink A, Dheda K, Diel R, Dominguez J, Lipman M, Nemeth J, Ravn P, Winkler S, Huitric E, Sandgren A, Manissero D. 2011. Interferon-gamma release assays for the diagnosis of active tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 37:100–111. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00114810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barcellini L, Borroni E, Brown J, Brunetti E, Codecasa L, Cugnata F, Dal Monte P, Di Serio C, Goletti D, Lombardi G, Lipman M, Rancoita PM, Tadolini M, Cirillo DM. 2016. First independent evaluation of QuantiFERON-TB Plus performance. Eur Respir J 47:1587–1590. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02033-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rozot V, Vigano S, Mazza-Stalder J, Idrizi E, Day CL, Perreau M, Lazor-Blanchet C, Petruccioli E, Hanekom W, Goletti D, Bart PA, Nicod L, Pantaleo G, Harari A. 2013. Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific CD8+ T cells are functionally and phenotypically different between latent infection and active disease. Eur J Immunol 43:1568–1577. doi: 10.1002/eji.201243262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nikolova M, Markova R, Drenska R, Muhtarova M, Todorova Y, Dimitrov V, Taskov H, Saltini C, Amicosante M. 2013. Antigen-specific CD4- and CD8-positive signatures in different phases of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 75(3):277–281. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yuen CM, Kammerer JS, Marks K, Navin TR, France AM. 2016. Recent transmission of tuberculosis - United States, 2011-2014. PLoS One 11:e0153728. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.France AM, Grant J, Kammerer JS, Navin TR. 2015. A field-validated approach using surveillance and genotyping data to estimate tuberculosis attributable to recent transmission in the United States. Am J Epidemiol 182:799–807. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gautam M, Darroch J, Bassett P, Davies PD. 2012. Tuberculosis infection in the indigenous elderly white UK population: a study of IGRAs. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 16:564. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petruccioli E, Vanini V, Chiacchio T, Cuzzi G, Cirillo DM, Palmieri F, Ippolito G, Goletti D. 2017. Analytical evaluation of QuantiFERON-Plus and QuantiFERON-Gold In-Tube assays in subjects with or without tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 106:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Day CL, Abrahams DA, Lerumo L, Janse van Rensburg E, Stone L, O'rie T, Pienaar B, de Kock M, Kaplan G, Mahomed H, Dheda K, Hanekom WA. 2011. Functional capacity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific T cell responses in humans is associated with mycobacterial load. J Immunol 187:2222–2232. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petruccioli E, Chiacchio T, Pepponi I, Vanini V, Urso R, Cuzzi G, Barcellini L, Cirillo DM, Palmieri F, Ippolito G, Goletti D. 2016. First characterization of the CD4 and CD8 T-cell responses to QuantiFERON-TB Plus. J Infect 73(6):588–597. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knierer J, Gallegos Morales EN, Schablon A, Nienhaus A, Kersten JF. 2017. QFT-Plus: a plus in variability? - Evaluation of new generation IGRA in serial testing of students with a migration background in Germany. J Occup Med Toxicol 12:1. doi: 10.1186/s12995-016-0148-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yi L, Sasaki Y, Nagai H, Ishikawa S, Takamori M, Sakashita K, Saito T, Fukushima K, Igarashi Y, Aono A, Chikamatsu K, Yamada H, Takaki A, Mori T, Mitarai S. 2016. Evaluation of QuantiFERON-TB Gold Plus for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in Japan. Sci Rep 6:30617. doi: 10.1038/srep30617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2011. Recommendations for use of an isoniazid-rifapentine regimen with direct observation to treat latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 60:1650–1653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saukkonen JJ, Cohn DL, Jasmer RM, Schenker S, Jereb JA, Nolan CM, Peloquin CA, Gordin FM, Nunes D, Strader DB, Bernardo J, Venkataramanan R, Sterling TR, ATS (American Thoracic Society) Hepatotoxicity of Antituberculosis Therapy Subcommittee. 2006. An official ATS statement: hepatotoxicity of antituberculosis therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 174:935–952. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200510-1666ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reddy D, Walker J, White LF, Brandeis GH, Russell ML, Horsburgh CR Jr, Hochberg NS. 2017. Latent tuberculosis infection testing practices in long-term care facilities, Boston, Massachusetts. J Am Geriatr Soc 65:1145–1151. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sterling TR, Villarino ME, Borisov AS, Shang N, Gordin F, Bliven-Sizemore E, Hackman J, Hamilton CD, Menzies D, Kerrigan A, Weis SE, Weiner M, Wing D, Conde MB, Bozeman L, Horsburgh CR Jr, Chaisson RE, TB Trials Consortium PREVENT TB Study Team. 2011. Three months of rifapentine and isoniazid for latent tuberculosis infection. N Engl J Med 365:2155–2166. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]