Abstract

Background

Constitutive methylation of tumor suppressor genes are associated with increased cancer risk. However, to date, the question of epimutational transmission of these genes remains unresolved. Here, we studied the potential transmission of BRCA1 and MGMT promoter methylations in mother-newborn pairs.

Methods

A total of 1014 female subjects (cancer-free women, n = 268; delivering women, n = 295; newborn females, n = 302; breast cancer patients, n = 67; ovarian cancer patients, n = 82) were screened for methylation status in white blood cells (WBC) using methylation-specific PCR and bisulfite pyrosequencing assays. In addition, BRCA1 gene expression levels were analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR.

Results

We found similar methylation frequencies in newborn and adults for both BRCA1 (9.9 and 9.3%) and MGMT (12.3 and 13.1%). Of the 290 mother-newborn pairs analyzed for promoter methylation, 20 mothers were found to be positive for BRCA1 and 29 for MGMT. Four mother-newborn pairs were positive for methylated BRCA1 (20%) and nine pairs were positive for methylated MGMT (31%). Intriguingly, the delivering women had 26% lower BRCA1 and MGMT methylation frequencies than those of the cancer-free female subjects. BRCA1 was downregulated in both cancer-free woman carriers and breast cancer patients but not in newborn carriers. There was a statistically significant association between the MGMT promoter methylation and late-onset breast cancers.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that BRCA1and MGMT epimutations are present from the early life of the carriers. We show the transmission of BRCA1 and MGMT epimutations from mother to daughter. Our data also point at the possible demethylation of BRCA1and MGMT during pregnancy.

Keywords: BRCA1, MGMT, Methylation, Transmission, Blood, Breast cancer, Ovarian cancer

Background

Defects in epigenetic manipulation, which results in the atypical transcriptional silencing of active genes and/or reactivation of silent genes, are defined as “Epimutation” [1]. This non-genetic change is a potent mechanism responsible for the suppression of various tumor suppressor genes; hence, it is considered as a mechanism for cancer predisposition [2]. The presence of epimutation in all animal tissues could be either germ line, with evidence of inheritance, or constitutional, with no evidence of inheritance [3–5]. DNA repair genes have been reported to be inactivated in many cancer types by epigenetic silencing mechanism. Deficiencies in these genes usually lead to genetic instability, which is an important mechanism in cancer initiation and/or progression.

BRCA1 is a DNA repair gene that is expressed in all mammalian cells. This gene plays an important role in the error-free pathway of homologous recombination [6], which repairs double-strand breaks. Cells that lack BRCA1 protein are prone to acquire mutations and chromosomal rearrangements, which can lead to carcinogenesis. It is well established that germline BRCA1 mutations are responsible for many familial cancer types including breast and ovarian cancers [7]. Similarly, methylation in the BRCA1 promoter is a mechanism for BRCA1 inactivation during early carcinogenesis. Constitutive BRCA1 methylation has been found to be associated with a 3.5-fold increase in the risk of developing early-onset breast cancer and a major predisposition factor for serous ovarian cancer [8–13]. This renders the constitutive BRCA1 promoter methylation as a potential predictive biomarker for breast and ovarian cancer predisposition [12].

MGMT is another DNA repair gene that is also inactivated in human cancers by promoter methylation [14, 15]. It is involved in the removal of an alkyl group from the O6 position of the guanine nucleotide [16]. The loss of MGMT activity leads to G>A transition due to the inability of removing the mutagenic adducts from guanine [17] resulting in DNA aberrations and tumor progression [18]. It has been reported that MGMT methylation is a common mechanism in triple negative breast cancers (TNBC) where it has been detected in 83.1% of the cases with a weak association with advanced age [19]. Furthermore, MGMT promoter methylation and the lack of MGMT expression were found to be associated with the mucinous and clear cell subtypes of epithelial ovarian cancer [20]. To date, the prevalence of MGMT methylation in cancer-free individuals and its potential inheritance have not been studied.

Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance is the passage of epigenetic markers, such as DNA methylation, through germline from one generation to the next. Evidences of epimutation inheritance have been reported for the DNA mismatch repair genes MLH1 and MSH2 [21–23]. Since no association has been found between the presence of BRCA1 methylation in peripheral blood cells and age [9, 10], it has been also suggested that BRCA1 epimutation might be inherited. However, up to date, the question of germ line BRCA1epimutation inheritance remains unresolved.

In this study, we investigated the prevalence of BRCA1 and MGMT promoter methylations in white blood cells (WBC) from cancer-free women and newborn females. In addition, we investigated the potential transmission of the epimutation of the two genes from mother to daughter in mother-newborn female pairs.

Results

Cancer-free women and newborns have similar frequencies of WBC BRCA1 promoter methylation

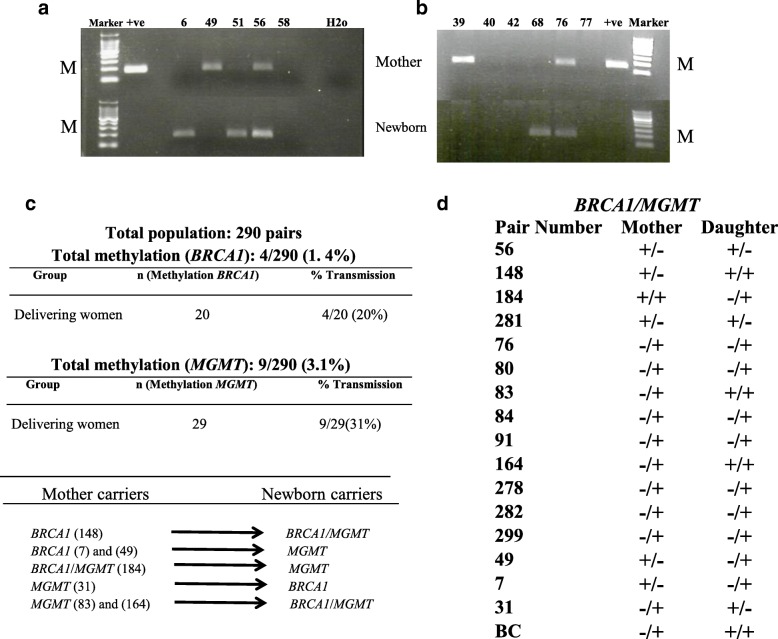

To investigate the potential transmission of methylated BRCA1 promoter from mother to daughter, we examined the BRCA1 promoter methylation status in DNA from WBC using MSP assay in a cohort of 865 female subjects (cancer-free women, n = 268; delivering women, n = 295; newborn females, n = 302). The cohort of the mothers and newborns included 290 mother-newborn pairs. We detected the BRCA1 promoter methylation in 25 of 268 (9.3%) cancer-free women and in 20 of 295 (6.8%) delivering women (Fig. 1a and Table 1). Interestingly, 30 of 302 (9.9%) newborns were positive for the methylated BRCA1 promoter. This shows that cancer-free women and newborns have similar frequencies of BRCA1 promoter methylation in their WBC.

Fig. 1.

BRCA1and MGMT promoter methylation status in DNA from WBC. MSP analysis of a BRCA1 promoter and b MGMT promoter. Totally methylated bisulfite-modified DNA was used as positive (+ve) control. Only the methylated bands are shown (M). Top panel for mothers, bottom panel for newborns. c, d Summary of BRCA1 and MGMT methylation transmission from mothers to daughters. (+) positive for methylation, (−) negative for methylation

Table 1.

Percentage of WBC DNA BRCA1 and MGMT methylations

| Total population (n = 1014) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gene | Group | Promoter methylation (%) |

| BRCA1 | Control women | 25/268 (9.3) |

| Delivering women | 20/295 (6.8) | |

| Newborns | 30/302 (9.9) | |

| Breast cancer | 5/67 (7.5) | |

| Ovarian cancer | 13/82 (15.8) | |

| MGMT | Control women | 35/268 (13.1) |

| Delivering women | 29/295 (9.8) | |

| Newborns | 37/302 (12.3) | |

| Breast cancer | 10/67 (15) | |

| Ovarian cancer | 17/82 (20.7) | |

| Group | Methylation (%) | |

| BRCA1/MGMT | Control women | 6/25 (24) |

| Delivering women | 2/20 (10) | |

| Newborns | 3/30 (10) | |

| Breast cancer | 0 | |

| Ovarian cancer | 5/17 (29.4) | |

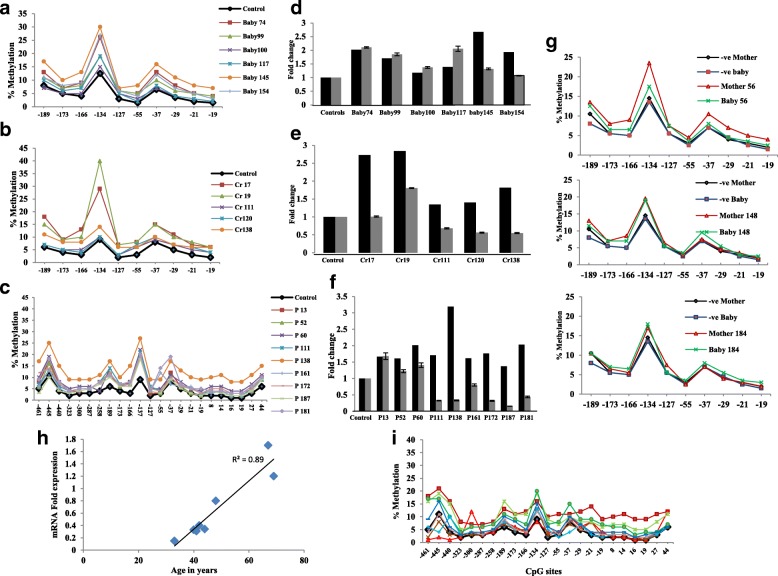

Cancer-free woman and newborn carriers have similar levels and pattern of WBC BRCA1 promoter CpG Island methylation

To further elucidate the BRCA1 promoter methylation status in newborn carriers as compared to woman carriers, we analyzed the level and the pattern of the BRCA1 promoter methylation in their WBC. The methylation levels and patterns were studied by sodium bisulfite pyrosequencing in 10 CpG sites located in the BRCA1 promoter at the 5′ flanking region. This region is known to have a strong promoter activity. Both women and newborns’ WBC DNA showed a distinct pattern of BRCA1 methylation wherein − 134 and − 37 sites showed higher levels of methylation compared to other sites (Fig. 2a, b). Furthermore, both DNA types contained similar levels of methylation across the 10 CpG sites. This indicates that the level and pattern of WBC BRCA1 promoter methylation are similar in woman and newborn carriers.

Fig. 2.

Methylation plots for BRCA1 promoter measured by bisulfite pyrosequencing assay. Levels and pattern of methylation of CpG sites along the BRCA1 promoter region in WBC from a newborn carriers, b woman carriers, c breast cancer patients, and i ovarian cancer patients. g Methylation plots for mother-newborn pairs. Black lines represent average values for control unmethylated samples, and colored lines represent single individuals. Numbers represent CpG sites relative to transcription start site. d–f Effect of promoter methylation on BRCA1 mRNA expression in WBC from newborn carriers, woman carriers, and breast cancer patients, respectively. Black bars represent fold change in BRCA1 promoter methylation. Gray bars represent fold change in BRCA1 expression. Cr carrier, P patient. h Correlation between BRCA1 mRNA levels in WBC and patient age. R2 correlation coefficient

BRCA1 epimutation is transmitted from mother to daughter

Interestingly, we found four out of the 20 mothers (20%), who were tested positive for BRCA1 methylation, had BRCA1 methylation-positive daughters (Fig. 1c, d). This result is the first indication of the transmission of BRCA1 epimutation from mother to daughter. To further verify the methylation in the positive mother-newborn pairs, the promoter region was analyzed by pyrosequencing in three pairs (Fig. 2g). Importantly, both mothers and newborns’ WBC DNA showed similar pattern and levels of methylation across the CpG sites analyzed. Importantly, we found one of the newborn carriers, who have a BRCA1 methylation-negative mother, has also a BRCA1 methylation negative father.

MGMT promoter is methylated in both cancer-free women and newborns

We have previously shown that the MGMT gene is methylated in WBC of cancer-free BRCA1 methylation carriers [24]. Thus, in this study, we sought to investigate whether there is an association between the presence of BRCA1 and MGMT promoter methylations in WBC. To this end, we analyzed the MGMT promoter methylation in WBC using MSP assay in the same cohort of 865 cancer-free females. We detected the MGMT methylation in 35 of 268 (13.1%) cancer-free women, in 29 of 295 (9.8%) delivering women, and in 37 of 302 (12.3%) newborns (Fig. 1b and Table 1). These results show a high prevalence of methylated MGMT promoter in both adult and newborns. Importantly, we found six women (24%), two delivering women (10%), and three newborns (10%) to be positive for paired BRCA1/MGMT methylation (Table 1).

MGMT epimutation is transmitted from mother to daughter

Interestingly, nine out of the 29 mothers (31%), who were tested positive for MGMT methylation, had MGMT methylation-positive daughters (Fig. 1c, d). This is also the first reported result suggesting the transmission of MGMT epimutation from mother to daughter. Additionally interesting, we found two BRCA1 methylation-positive mothers having MGMT methylation-positive daughters and vice versa (Fig. 1c, d). Notably, the mother of a BRCA1 woman carrier was a breast cancer patient who was positive for methylated MGMT (Fig. 1d).

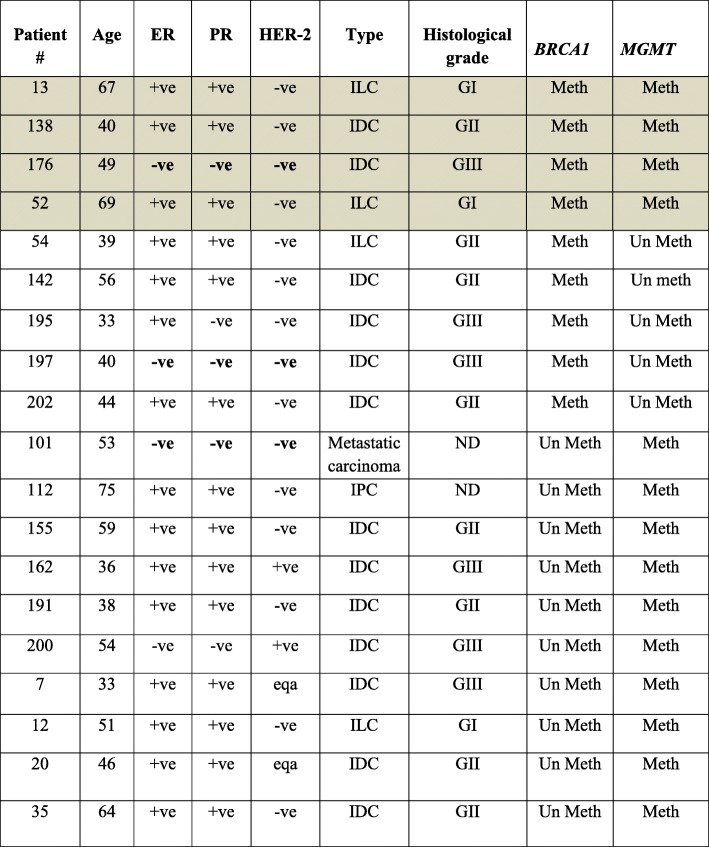

MGMT promoter methylation is associated with ovarian cancer and the late onset of breast cancer

In order to value the epimutation of MGMT and BRCA1 in WBC from cancer-free women and newborns, we investigated the prevalence of the methylated BRCA1 and MGMT promoters in breast and ovarian cancer patients. To this end, we screened 67 breast and 82 ovarian cancer patients using MSP assay. We found that 5 out of 67 (7.5%) breast and 13 out of 82 (15.8%) ovarian cancer patients tested positive for BRCA1 promoter methylation (Table 1). Moreover, 10 of 67 (15%) breast and 17 of 82 (20.7%) ovarian cancer patients were positive for MGMT methylation (Table 1). We did not detect any case with both BRCA1 and MGMT methylations in breast cancer patients. However, in a cohort of 17 breast cancer patients who were tested positive for BRCA1 methylation in our previous study [24], four patients (23.5%) were found to be positive for MGMT methylation (Table 2). Interestingly, we found that the mean age for the onset of breast cancer in the BRCA1 methylation-positive patients was 40.3 ± 6.4 (95%CI 37.1–43.4) years compared to 50.9 ± 12.7 (95%CI 41.8–60) years for methylated MGMT and 56 ± 14.1(95%CI 33.8–78.7) years for both BRCA1/MGMT-methylated patients (p = 0.0044). This indicates a significant association between the MGMT methylation and late onset of the disease, (p = 0.0253) for MGMT alone and (p = 0.0157) for paired BRCA1/MGMT. Importantly, five of the 13 (38.5%) BRCA1 methylation-positive ovarian cancer patients had methylated MGMT gene. However, no association was found between the MGMT methylation and the onset of the disease (Table 3).

Table 2.

Clinical characterizations of BRCA1- and MGMT-methylated breast cancer-positive cases

Shaded area specifies patients identified in our previous study (reference [24])

ILC invasive lobular carcinoma, IDC invasive ductal carcinoma, ND no data

Table 3.

Clinical characterizations of BRCA1- and MGMT-methylated ovarian cancer patients

| Patient no. | Age | Type | Grade | BRCA1 | MGMT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 54 | Clear cell carcinoma | Advanced | Meth | Meth |

| 13 | 54 | Serous carcinoma | High | Meth | Meth |

| 36 | 55 | Ovarian serous carcinoma | High | Meth | Meth |

| 50 | 43 | Ovarian serous carcinoma. | High | Meth | Meth |

| 23 | 40 | Serous carcinoma | High | Mut/Meth | Meth |

| 38 | 54 | Serous carcinoma | ND | Mut/Meth | Un Meth |

| 7 | 57 | Papillary serous carcinoma | High | Meth | Un Meth |

| 24 | 53 | Serous adenocarcinoma | 3 | Meth | Un Meth |

| 27 | 47 | Serous carcinoma involving uterus | High | Meth | Un Meth |

| 52 | 67 | ovarian adenocarcinoma | High | Meth | Un Meth |

| 59 | 53 | ovarian serous carcinoma | High | Meth | Un Meth |

| 71 | 38 | Ovarian serous carcinoma | ND | Meth | Un Meth |

| 29 | 47 | Carcinoma of the right ovary | High | Meth | Un Meth |

| 6 | 58 | Papillary serous carcinoma | High | Mut | Meth |

| 14 | 34 | Serous adenocarcinoma | High | Mut | Meth |

| 47 | 65 | Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma | ND | Mut | Meth |

| 17 | 66 | serous ovarian carcinoma | ND | Mut | Meth |

| 69 | 41 | Ovarian serous carcinoma | ND | Mut | Meth |

| 4 | 38 | Clear cell carcinoma | GII | WT | Meth |

| 9 | 46 | papillary serous cancer | High | WT | Meth |

| 16 | 67 | Serous adenocarcinoma | High | WT | Meth |

| 44 | 88 | Metastatic granulosa cell tumor | ND | WT | Meth |

| 55 | 43 | serous carcinoma | High | WT | Meth |

| 60 | 49 | Granulosa cell tumor | ND | WT | Meth |

| 79 | 44 | Mucinous cyst adenocarcinoma | ND | WT | Meth |

Meth methylated, Mut mutated, WT wild type, ND no data

BRCA1 expression is reduced in breast cancer patients and woman carriers but not in newborn carriers

Next, we sought to assess the expression of BRCA1, at the level of mRNA, in WBC. To this end, we analyzed the expression level of the BRCA1 gene by real-time RT-PCR in the newborn carriers, woman carriers, and BRCA1 methylation-positive breast cancer patients. Interestingly, we did not find any reduction in the expression level of the BRCA1 in six highly methylated newborns as compared to unmethylated controls (Fig. 2a, d). However, in woman carriers, the expression level was reduced by two folds in three out of five woman carriers (Fig. 2b, e). Furthermore, we found a considerable reduction in the expression level of the BRCA1 in six out of nine breast cancer patients (Fig. 2c, f). Interestingly, the fold change of the BRCA1 expression level in breast cancer patients highly correlated (R = 0.89) with patient’s age in eight out of nine cases (Fig. 2h). We were not able to analyze the expression level of BRCA1 in ovarian cancer patients due to lack of RNA samples. However, we found extensive disorganization in the pattern and levels of methylation across the 23 CpG sites in the promoter region as compared to that in cancer-free woman and newborn carriers (Fig. 2i).

Discussion and conclusions

In this study, we have screened a total of 865 females for their WBC BRCA1 and MGMT promoters’ methylation status by the MSP assay. The overall frequencies were 8.7% for the BRCA1 and 11.7% for the MGMT gene promoter. Remarkably, we found the frequency of BRCA1 methylation to be similar in both newborns and adult females and are analogous to our previously reported frequencies [11, 24]. Importantly, both newborn and adult samples showed identical pattern and levels of methylation across all the studied CpG sites in the BRCA1 promoter. This indicates that constitutional epimutation of the BRCA1gene is present from the early life of the carriers, as opposed to the belief that it is acquired later on during the lifetime of the individual.

The frequencies of BRCA1 and MGMT methylations in delivering women were about 26% lower than that of both adult and newborn females, suggesting that the BRCA1 and MGMT promoters are demethylated in women during pregnancy. Indeed, it has been reported that pregnancy reprograms the epigenome as a protective mechanism against breast cancer in women [25]. In addition, it was found that the IGF acid labile subunit, which is responsible for transporting the IGF1 protein in the blood circulation, is activated by hypomethylation whereas the IGF1R is silenced by hypermethylation [26]. Thus, the epigenetic modifications of these two genes could contribute to the protective outcome of early pregnancy and parity against breast cancers. Hence, it is plausible that in a portion of the delivering women, the BRCA1 and MGMT promoters are demethylated due to either parity or early pregnancy as a protective mechanism against breast and ovarian cancers. However, further studies with larger sample size are needed to verify this.

Our group is the first to report the transmission of the BRCA1 and MGMT epimutations from mothers to daughters. Although the overall frequency of inheritance was low, 1.4% for BRCA1 and 3.1% for MGMT, it accounted for a high proportion of the mother carriers. In a recent report, the authors have concluded that BRCA1 methylation is not transmitted from mother to daughter [27]. The discordance between the two studies could be due to the sample sizes, 6 mother-daughter pairs versus 290 pairs in our study. Although, in our study, BRCA1 methylation was not transmitted from father to daughter, we cannot rule out the potential inheritance through paternal germ line as only one father was tested. However, we can conclude from this result that the majority of BRCA1 epimutation appears to occur during early development, which could be due to an exposure to environmental insults. The finding that BRCA1 mother carriers have MGMT newborn carriers, and vice versa may indicate a possible link between the constitutional epimutation of these two genes. Additionally important, it does rule out the possibility of contamination of maternal blood in cord samples.

The inheritance of methylated cancer-associated genes has been previously reported [21, 22]. As constitutive methylation of BRCA1 and MGMT has been found to associate with an increased risk of cancer development [8–13, 28], it is conceivable to believe that the affected daughter has a high risk for developing these cancers. Indeed, it has been reported that a mother with constitutional MLH1 and who had Lynch syndrome has transmitted MLH1 epimutation to two of her children who developed also early colonic tumors [23].

It is still not clear whether epimutational inheritance occurs per se or it arises due to cross linkage to cis-acting genetic lesions. Several studies have revealed the constitutional epimutation of tumor suppressor genes to be linked to cis-acting genetic lesions [29–31]. As no such genetic lesion has been found in the promoter of BRCA1 to explain its methylation [13], the inheritance of BRCA1 methylation, we report in this study, may support the concept of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance.

In this study, we report a high frequency of constitutional BRCA1and MGMT methylation in breast and ovarian cancer. The detection of methylated BRCA1in WBC from ovarian cancer was reported previously in 20 out of 154 cases [32]. Although several studies have shown high frequencies of methylated MGMT promoter in breast and ovarian tumor tissues, our study is the first in finding the methylated MGMT in patients’ peripheral WBC [19, 20, 33, 34] suggesting that as in BRCA1, MGMT epigenetic modification in WBC also predispose women to breast and ovarian cancer. While we found a significant association between constitutional BRCA1 methylation and early onset breast cancers (≤ 40 years) [11, 24], the constitutional MGMT methylation was significantly associated with late onset (≥ 50 years). Our results are in concordance with a previous study where a weak association was found between MGMT methylation with advanced age in triple negative breast cancers [19].

The analysis of the pattern and levels of methylation across the CpG sites in the BRCA1 promoter region revealed that this pattern was very well-defined in the newborn and adult carriers but it was highly disorganized in the breast and ovarian cancer patients. Although in newborn carriers, we found high methylation levels in a region known to have strong promoter activity; this did not decrease the BRCA1expression. This is in accord with the argument that constitutional methylation is mono allelic [35]; consequently, only one allele of the BRCA1 gene is methylated in the newly born carriers. However, according to the Knudson’s two-hit hypothesis, in the breast cancer patients, the two alleles are affected through the progress of the patient’s life [36]. Indeed, in the woman carriers, a twofold decrease in the expression level of the BRCA1 mRNA was found in three out of five individuals, while the highest level of reduction in BRCA1 expression was detected in breast cancer cases, which, interestingly, correlated highly (R = 0.89) with patient’s age reflecting the association between BRCA1 promoter methylation and the early onset of the disease. Importantly, lower BRCA1 expression was detected in blood leukocytes from healthy unaffected BRCA1mutation carriers as compared to that in controls [37] indicating the similarity between the effect of methylated and mutated BRCA1.

In conclusion, we have clearly shown:

The transmission of both BRCA1 and MGMT epimutations from mother to daughter.

The frequencies of BRCA1 and MGMT epimutations in female newborns are similar to that of cancer-free women.

Our data point at the possible demethylation of BRCA1 and MGMT through reprograming of the epigenome during pregnancy.

-

MGMT epimutation is associated with ovarian cancer and the late onset of breast cancer.

Our study sheds some light on the potential use of epimutations in cord blood as predictive biomarkers for cancer.

Methods

Study population

The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written consent before participation. Ten milliliters of cord blood and 10 ml of maternal peripheral blood were collected at the time of delivery at Al Yamamah Hospital (Riyadh), age of mothers range 19–46 years. Additionally, 10 ml of fresh peripheral blood was collected from cancer-free females, age range 15–50 years, and from breast and ovarian cancer patients coming to the oncology department in King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Clinicopathological data (age, histological grade, and ER and PR status) were provided by the Department of Pathology. All blood samples were collected into EDTA tubes.

Blood DNA and RNA isolation

Blood samples were immediately centrifuged at 2000×g for 10 min at 4 °C, and WBCs were carefully collected and transferred into two 2-ml Eppendorf tubes, one containing 900 ml RBC Lysis solution for subsequent DNA extraction using the Gentra Puregene Blood Kit and the other tube contained 1.2 ml RNALater solution for subsequent RNA extraction using RiboPure Blood Kit (Ambion).

Methylation-specific PCR

DNA was treated with sodium bisulfate DNA and purified using EpiTect Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. The DNA was then amplified using published PCR primers for BRCA1 and MGMT [38, 39] that distinguish methylated and unmethylated DNA. PCR products were electrophoresed on 2% agarose gels and stained with Ethidium bromide. Totally methylated bisulfite-treated DNA was used as positive control. All the PCR reactions were repeated at least twice.

Bisulfite pyrosequencing

DNA methylation was quantified by bisulfite pyrosequencing. Five different assays were designed using the PyroMark Assay Design software (Qiagen) in order to analyze the methylation status of 23 CpG sites across the BRCA1 promoter. All the primers used in PCR amplifications and sequencings are listed in Table 4. The PCR and pyrosequencing reactions were performed using PyroMark products and reagents (Qiagen) as previously described [40]. Methylation quantification was performed using PyroMark Q24 software (Qiagen).

Table 4.

Bisulfite pyrosequencing and real-time PCR primers

| Primers sequences | No. of CpG sites | Annealing temp | |

|---|---|---|---|

| F1 R1Bio Sequencing |

GGTATTGGATGTTTTTTTTTATAAGATTAT CCAATCCCCCACTCTTTC ATTATAGTTTTTAAGGAATATTGTG |

3 | 56 |

| F2 R2 Sequencing |

GAAAGAGTGGGGGATTGGGATT AAAATACCTACCCTCTAACCTCTACT ACCTCTACTCTTCCA |

4 | 60 |

| F3 R3 Bio Sequencing |

AGGGTAGGTATTTTATGGTAAATTTAGGT TATCTAAAAAACCCCACAACCTATCC ATGGTAAATTTAGGTAGAATTTT |

5 | 60 |

| F4 R4Bio Sequencing |

AGATTGGGTGGTTAATTTAGAGT TCTAAAAAACCCCACAACCTATCC GGAAAAGAGAGGGAATTATAGATAA |

6 | 58 |

| F5 R5 Bio Sequencing |

GGGGTAGATTGGGTGGTTAA TTATCTAAAAAACCCCACAACCTATC GAGAGGTTGTTGTTTAG |

5 | 58 |

| BRCA1 | F 5′–TGTAGGCTCCTTTTGGTTATATCATTC–3′ R 5′–CATGCTGAAACT TCTCAACCAGAA–3′ |

59 °C | |

| β- Actin | F 5′–TCC CTG GAG AAG AGC TAC GA–3′ R 5′–TGA AGG TAG TTT CGT GGA TGC–3′ |

59 °C | |

F forward, R reverse

Real-time PCR

cDNA was generated from RNA by Superscript III (Invitrogen) reverse transcriptase and random hexomers. Quantitative real-time PCR was then performed with primer pairs specific for BRCA1 transcript using Actin as an internal control. Primers are listed in Table 4. PCR was performed with SYBR green using CFX96 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad). The relative BRCA1 expression was calculated based on the threshold cycle (Ct) value using the 2−ΔΔct method. The fold change of mRNA expression was done relative to unmethylated cancer-free women for breast cancer patients and woman carriers and relative to unmethylated babies for the newly born baby carriers.

Statistical analysis

General linear regression (GLM) was performed to determine the statistical significance for the association between BRCA1and MGMT promoter methylation and age of patients. All observed differences were considered to be significant when associated with a p value < 0.05.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the mothers, patients, and controls who participated in this study. We would like to acknowledge Dr. Abdelilah Aboussekhra for revising the article.

Funding

This work was supported by The National Comprehensive Plan for science and Technology, project number 14-MED2307-20.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Authors’ contributions

NM conceived and designed the study. NM, MS, NY, and BS performed the data analysis. LA, SM, and HH contributed to the sample and data collection. NM drafted the manuscript with the help from BK and HA. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written consent before the participation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Nisreen Al-Moghrabi, Phone: 966 11 4647272, Email: nisreen@kfshrc.edu.sa.

Maram Al-Showimi, Phone: 966 11 4647272, Email: malshowimi@kfshrc.edu.sa.

Nujoud Al-Yousef, Phone: 966 11 4647272, Email: nyousef@kfshrc.edu.sa.

Bushra Al-Shahrani, Phone: 966 11 4647272, Email: balshahrani9@kfshrc.edu.sa.

Bedri Karakas, Phone: 966 11 4647272, Email: bkarakas@kfshrc.edu.sa.

Lamyaa Alghofaili, Phone: +966) 11 215-7777, Email: lalghofaili@alfaisal.edu.

Hannah Almubarak, Phone: +966) 11 215-7777, Email: Hannah.fmubarak@gmail.com.

Safia Madkhali, Phone: +966) 11 4299999, Email: sfhmadkhli@gmail.com.

Hind Al Humaidan, Phone: +966) 11 215-7777, Email: hahumaidan@kfshrc.edu.sa.

References

- 1.Cropley JE, Martin DI, Suter CM. Germline epimutation in humans. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9(12):1861–1868. doi: 10.2217/14622416.9.12.1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones PA, Baylin SB. The fundamental role of epigenetic events in cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3(6):415–428. doi: 10.1038/nrg816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chong S, Youngson NA, Whitelaw E. Heritable germline epimutation is not the same as transgenerational epigenetic inheritance. Nat Genet. 2007;39(5):574–575. doi: 10.1038/ng0507-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horsthemke B. Heritable germline epimutations in humans. Nat Genet. 2007;39(5):573–574. doi: 10.1038/ng0507-573b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suter CM, Martin DI. Inherited epimutation or a haplotypic basis for the propensity to silence? Nat Genet. 2007;39(5):573. doi: 10.1038/ng0507-573a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacinto FV, Esteller M. Mutator pathways unleashed by epigenetic silencing in human cancer. Mutagenesis. 2007;22(4):247–253. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gem009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Welcsh PL, King MC. BRCA1 and BRCA2 and the genetics of breast and ovarian cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10(7):705–713. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.7.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matros E, Wang ZC, Lodeiro G, Miron A, Iglehart JD, Richardson AL. BRCA1 promoter methylation in sporadic breast tumors: relationship to gene expression profiles. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;91(2):179–186. doi: 10.1007/s10549-004-7603-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwamoto T, Yamamoto N, Taguchi T, Tamaki Y, Noguchi S. BRCA1 promoter methylation in peripheral blood cells is associated with increased risk of breast cancer with BRCA1 promoter methylation. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;129(1):69–77. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1188-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kontorovich T, Cohen Y, Nir U, Friedman E. Promoter methylation patterns of ATM, ATR, BRCA1, BRCA2 and p53 as putative cancer risk modifiers in Jewish BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;116(1):195–200. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0121-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Moghrabi N, Al-Qasem AJ, Aboussekhra A. Methylation-related mutations in the BRCA1 promoter in peripheral blood cells from cancer-free women. Int J Oncol. 2011;39(1):129–135. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong EM, Southey MC, Fox SB, Brown MA, Dowty JG, Jenkins MA, Giles GG, Hopper JL, Dobrovic A. Constitutional methylation of the BRCA1 promoter is specifically associated with BRCA1 mutation-associated pathology in early-onset breast cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4(1):23–33. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hansmann T, Pliushch G, Leubner M, Kroll P, Endt D, Gehrig A, Preisler-Adams S, Wieacker P, Haaf T. Constitutive promoter methylation of BRCA1 and RAD51C in patients with familial ovarian cancer and early-onset sporadic breast cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(21):4669–4679. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cho YH, Yazici H, Wu HC, Terry MB, Gonzalez K, Qu M, Dalay N, Santella RM. Aberrant promoter hypermethylation and genomic hypomethylation in tumor, adjacent normal tissues and blood from breast cancer patients. Anticancer Res. 2010;30(7):2489–2496. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho YH, McCullough LE, Gammon MD, Wu HC, Zhang YJ, Wang Q, Xu X, Teitelbaum SL, Neugut AI, Chen J, et al. Promoter hypermethylation in white blood cell DNA and breast cancer risk. J Cancer. 2015;6(9):819–824. doi: 10.7150/jca.12174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daniels DS, Woo TT, Luu KX, Noll DM, Clarke ND, Pegg AE, Tainer JA. DNA binding and nucleotide flipping by the human DNA repair protein AGT. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11(8):714–720. doi: 10.1038/nsmb791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerson SL. MGMT: its role in cancer aetiology and cancer therapeutics. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(4):296–307. doi: 10.1038/nrc1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim JI, Suh JT, Choi KU, Kang HJ, Shin DH, Lee IS, Moon TY, Kim WT. Inactivation of O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase in soft tissue sarcomas: association with K-ras mutations. Hum Pathol. 2009;40(7):934–941. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fumagalli C, Pruneri G, Possanzini P, Manzotti M, Barile M, Feroce I, Colleoni M, Bonanni B, Maisonneuve P, Radice P, et al. Methylation of O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) promoter gene in triple-negative breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134(1):131–137. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1945-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roh HJ, Suh DS, Choi KU, Yoo HJ, Joo WD, Yoon MS. Inactivation of O(6)-methyguanine-DNA methyltransferase by promoter hypermethylation: association of epithelial ovarian carcinogenesis in specific histological types. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2011;37(7):851–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2010.01452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hitchins MP, Wong JJ, Suthers G, Suter CM, Martin DI, Hawkins NJ, Ward RL. Inheritance of a cancer-associated MLH1 germ-line epimutation. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(7):697–705. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morak M, Schackert HK, Rahner N, Betz B, Ebert M, Walldorf C, Royer-Pokora B, Schulmann K, von Knebel-Doeberitz M, Dietmaier W, et al. Further evidence for heritability of an epimutation in one of 12 cases with MLH1 promoter methylation in blood cells clinically displaying HNPCC. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16(7):804–811. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crepin M, Dieu MC, Lejeune S, Escande F, Boidin D, Porchet N, Morin G, Manouvrier S, Mathieu M, Buisine MP. Evidence of constitutional MLH1 epimutation associated to transgenerational inheritance of cancer susceptibility. Hum Mutat. 2012;33(1):180–188. doi: 10.1002/humu.21617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al-Moghrabi N, Nofel A, Al-Yousef N, Madkhali S, Bin Amer SM, Alaiya A, Shinwari Z, Al-Tweigeri T, Karakas B, Tulbah A, et al. The molecular significance of methylated BRCA1 promoter in white blood cells of cancer-free females. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:830. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katz TA. Potential mechanisms underlying the protective effect of pregnancy against breast cancer: a focus on the IGF pathway. Front Oncol. 2016;6:228. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2016.00228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katz TA, Liao SG, Palmieri VJ, Dearth RK, Pathiraja TN, Huo Z, Shaw P, Small S, Davidson NE, Peters DG, et al. Targeted DNA methylation screen in the mouse mammary genome reveals a parity-induced hypermethylation of Igf1r that persists long after parturition. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2015;8(10):1000–1009. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-15-0178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wojdacz TK, Harari F, Vahter M, Broberg K. Discordant pattern of BRCA1 gene epimutation in blood between mothers and daughters. J Clin Pathol. 2015;68(7):575–577. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2015-202982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shen L, Kondo Y, Rosner GL, Xiao L, Hernandez NS, Vilaythong J, Houlihan PS, Krouse RS, Prasad AR, Einspahr JG, et al. MGMT promoter methylation and field defect in sporadic colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(18):1330–1338. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hitchins MP, Rapkins RW, Kwok CT, Srivastava S, Wong JJ, Khachigian LM, Polly P, Goldblatt J, Ward RL. Dominantly inherited constitutional epigenetic silencing of MLH1 in a cancer-affected family is linked to a single nucleotide variant within the 5'UTR. Cancer Cell. 2011;20(2):200–213. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ligtenberg MJ, Kuiper RP, Chan TL, Goossens M, Hebeda KM, Voorendt M, Lee TY, Bodmer D, Hoenselaar E, Hendriks-Cornelissen SJ, et al. Heritable somatic methylation and inactivation of MSH2 in families with Lynch syndrome due to deletion of the 3′ exons of TACSTD1. Nat Genet. 2009;41(1):112–117. doi: 10.1038/ng.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Candiloro IL, Dobrovic A. Detection of MGMT promoter methylation in normal individuals is strongly associated with the T allele of the rs16906252 MGMT promoter single nucleotide polymorphism. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2009;2(10):862–867. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dobrovic A, Mikeska T, Alsop K, Candiloro I, George J, Mitchell G, Bowtell D. Constitutional BRCA1 methylation is a major predisposition factor for high-grade serous ovarian cancer. [abstract]. In: Proceedings of the 105th Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research; 2014 Apr 5-9; San Diego, CA. Philadelphia (PA): AACR; Cancer Res 2014;74(19 Suppl):Abstract nr 290. 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2014-290.

- 33.Munot K, Bell SM, Lane S, Horgan K, Hanby AM, Speirs V. Pattern of expression of genes linked to epigenetic silencing in human breast cancer. Hum Pathol. 2006;37(8):989–999. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharma G, Mirza S, Parshad R, Srivastava A, Gupta SD, Pandya P, Ralhan R. Clinical significance of promoter hypermethylation of DNA repair genes in tumor and serum DNA in invasive ductal breast carcinoma patients. Life Sci. 2010;87(3–4):83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wojdacz TK, Thestrup BB, Overgaard J, Hansen LL. Methylation of cancer related genes in tumor and peripheral blood DNA from the same breast cancer patient as two independent events. Diagn Pathol. 2011;6:116. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-6-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knudson AG. Hereditary cancer: two hits revisited. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1996;122(3):135–140. doi: 10.1007/BF01366952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chehade R, Pettapiece-Phillips R, Salmena L, Kotlyar M, Jurisica I, Narod SA, Akbari MR, Kotsopoulos J. Reduced BRCA1 transcript levels in freshly isolated blood leukocytes from BRCA1 mutation carriers is mutation specific. Breast Cancer Res. 2016;18(1):87. doi: 10.1186/s13058-016-0739-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Birgisdottir V, Stefansson OA, Bodvarsdottir SK, Hilmarsdottir H, Jonasson JG, Eyfjord JE. Epigenetic silencing and deletion of the BRCA1 gene in sporadic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8(4):R38. doi: 10.1186/bcr1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Esteller M, Hamilton SR, Burger PC, Baylin SB, Herman JG. Inactivation of the DNA repair gene O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase by promoter hypermethylation is a common event in primary human neoplasia. Cancer Res. 1999;59(4):793–797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tost J, Gut IG. DNA methylation analysis by pyrosequencing. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(9):2265–2275. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.