Abstract

Background

To investigate the incidence and related risk factors of delirium in elderly patients with hip fracture.

Methods

This is a retrospective study, performed in a medical center from October 2014 to February 2017, which enrolled all subjects aged over 65 years who were admitted for hip surgeries (hip arthroplasty, proximal femoral nail fixation). Univariate and multivariate logistic analysis was used to determine the incidence and risk factors of delirium. Delirium was assessed according to the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM).

Results

Overall, 19.29% of total 306 patients (mean age 81.9 ± 5.4 years) were identified as delirium. The delirium was significantly associated (p < 0.05) with the factors of age, hospitalization, diabetes, preoperative hematocrit (HCT), perioperative protein consumption, transfusion volume, preoperative leukocyte level, albumin level, American Society of Anesthesiologists (NYHA) classification, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification, blood loss, coronary heart disease, and cerebral infarction. Multivariate analysis of the variables confirmed that age (> 75 years old), diabetes, and ASA classification (> 2 level) are the independent risk factors of postoperative delirium (POD). In addition, patients in delirium had prolonged hospitalization and high perioperative albumin infusion.

Conclusion

The elderly patients over the age of 75 years with the history of diabetes or ASA classification > 2 level were at higher risk of POD. Delirium is an important postoperative complication, which had prolonged hospitalization and high perioperative albumin infusion.

Level of evidence: III

Keywords: Delirium, Risk factors, Hip facture

Background

Delirium, or acute cognitive function state, is a common postoperative complication that is manifested by a change of mindset and attention deficit over time [1]. Previous literature has described that the incidence of delirium in hospitalized patients vary from 11 to 42% according to population studied [2]. However, the incidence of delirium is 51% following orthopedic surgery for hip fractures. Moreover, in ICU, up to 81% of patients manifest delirium [3]. Postoperative delirium (POD) is associated with extended lengths of stay, higher patient care costs, increased morbidity, and functional and cognitive decline [4]. POD has been reported to be associated with a large number of risk factors: age, dementia, impaired left ventricular function, electrolyte disorder, alcoholism, smoking, high perioperative transfusion requirements, intraoperative pressure fluctuation, and use of benzodiazepine [5–9]. POD occurs mostly in some types of surgery, such as hip surgery, major gastrointestinal surgery, and major cardiac surgery [10–12]. The occurrence and development of delirium following the hip surgery in the elderly is not conducive to the early functional exercise and rehabilitation process [13, 14].The preoperative assessment of the risk factors for delirium is one of the ways to clarify the pathogenesis of POD and propose effective prevention measures. This study focused on elderly patients (aged 65 years or more) admitted to a hospital for conditions (including femoral neck fracture, intertrochanteric fracture) and general surgical procedures (hip arthroplasty, proximal femoral nail fixation). Univariate and multivariate logistic analysis was used to determine the incidence and risk factors of delirium and provide a reliable and accurate theoretical basis for the prevention and treatment of POD.

Methods

Patients and design

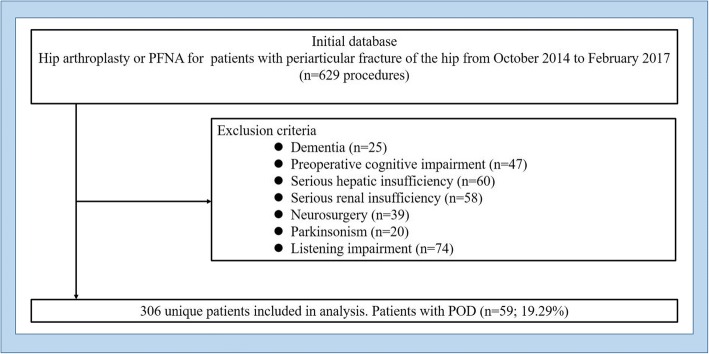

After obtaining approval from Tianjin Medical University General Hospital Ethics Review Board, we retrospectively reviewed the medical records of all patients aged over 65 years who underwent hip surgery. Thus, patient’s information described in this article was obtained from medical records. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (I) hip fracture (femoral neck fracture, intertrochanteric fracture), (II) the elderly aged over 65 years old, and (III) elective surgery (hip arthroplasty, proximal femoral nail fixation). Exclusion criteria were as follows: (I) preoperative history of schizophrenia, epilepsy, parkinsonism, dementia, delirium, brain injury, or neurosurgery; (II) communication and listening impairment; (III) serious hepatic insufficiency (Child-Pugh class C), serious renal insufficiency (undergoing dialysis before surgery), and hemopathy (leukemia, lymphoma, aplastic anemia); and (IV) preoperative cognitive impairment. The specific content is displayed in the flow chart Fig. 1. Of the patients who participated, the relevant preoperative intraoperative and postoperative demographic and clinicopathologic parameters were recorded. The medical history including cerebral infarction, coronary heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, and the use of benzodiazepines, hypnotics, narcotic drugs, and antiarrhythmic was collected. The suspicious symptoms of POD were evaluated daily after operation by a nerve physician and two trained nurses according to Confusion Assessment Method (CAM). The CAM instrument, which can be completed in less than 5 min, consists of nine operationalized criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-HI-R). The diagnosis of delirium by CAM requires the presence of features 1 and 2 and either 3 or 4. The specific content is presented in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the specific contentᅟ

Table 1.

Specific content of the Confusion Assessment Method

| The Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) | |

|---|---|

| Feature 1 | Acute change in mental status with a fluctuating course |

| Is there evidence of an acute change in mental status from the patient’s baseline? Did this behavior fluctuate during the past day, that is, tend to come and go or increase and decrease in severity? This feature is usually obtained from a family member or nurse and is shown by positive responses. | |

| Feature 2 | Inattention |

| Dose the patients have difficulty focusing attention, for example, being easily distractible, or having difficulty keeping track of what was being said? | |

| Feature 3 | Disorganized thinking |

| This feature is shown by a positive response to the following question: Was the patient’s thinking disorganized or incoherent, such as rambling or irrelevant conversation, unclear or illogical flow of ideas, or unpredictable switching from subject to subject? | |

| Feature 4 | Altered level of consciousness |

| Overall, how would you rate this patient’s level of consciousness? (alert [normal], vigilant [hyperalert], lethargic [drowsy, easily aroused], stupor [difficult to arouse], or coma [unarousable]) | |

The diagnosis of delirium by CAM requires the presence of features 1 and 2 and either 3 or 4

Collection of risk factors

The preoperative risk factors include age, gender, body mass index (BMI), cerebral infarction, coronary heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, American Society of Anesthesiologists (NYHA) classification, Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification, deep venous thrombosis (DVT), use of benzodiazepines, hypnotics, narcotic drugs, antiarrhythmic, hematocrit (HCT), leucocyte count, albumin, total protein (TP) and hemoglobin (Hb), and preoperative hospitalization.

The intraoperative risk factors include duration of operation and anesthesia, type of surgery and anesthesia, blood transfusion volume, and blood loss.

The postoperative risk factors include protein consumption, hematocrit, leucocyte count, hospitalization, hemoglobin, sodium, and potassium.

Statistical analysis

We use SPSS Statistical software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) to perform the statistical analysis. Unless otherwise indicated, data are reported as the number of events and their percentage for frequency data and as mean and SD for continuous data. Group comparisons were analyzed by Student’s t test for frequency data and the chi-squared test for ordered categorical data. Univariate logistic analysis was used to identify the risk factors associated with POD. The variables identified as xsignificant in univariate analysis were subsequently included in a stepwise multivariate logistic analysis to identify independent predictors of delirium. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Incidence of postoperative delirium (POD)

Based on the preset inclusion and exclusion criteria, 629 individuals were enrolled from the inception of October 2014 to February 2017 and 323 patients were excluded. The non-delirium group comprised 247 cases, and the delirium group comprised 59 cases. The incidence of POD was 59 (19.29%), including 23 males and 36 females, ranging in age from 70 to 93 years with an average of 81.9 ± 5.4 years old. Two hundred forty-seven cases had no delirium, including 81 males and 166 females, ranging in age from 65 to 96 years, with an average 76.4 ± 8.1 years old.

Comparison between the two groups

Patients with POD were assigned to the delirium group, and the patients without delirium were assigned to non-delirium group. We compared the various factors between the two groups (Table 2). There were significant differences between the two groups in diabetes, cerebral infarction, coronary heart disease, duration of hospitalization, preoperative hospitalization, preoperative hematocrit, postoperative albumin consumption, blood transfusion, preoperative albumin, preoperative and postoperative leucocyte count, ASA classification, NYHA classification.

Table 2.

Patient’s clinical characteristics

| Variable | Delirium (n = 59) | Non-delirium (n = 247) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 81.9 ± 5.4 | 76.4 ± 8.1 | t = − 0.647 | p = 0.000 |

| Gender(M/F) | 23/36 | 81/166 | χ2 = 0.813 | p = 0.367 |

| Hypertension (n) | 27 | 147 | χ2 = 3.672 | p = 0.550 |

| Coronary heart disease (n) | 35 | 187 | χ2 = 6.421 | p = 0.011 |

| Diabetes (n) | 36 | 192 | χ2 = 7.006 | p = 0.008 |

| Cerebral infarction (n) | 44 | 214 | χ2 = 5.240 | p = 0.020 |

| Hospitalization | 24.2 ± 15.1 | 16.0 ± 7.2 | t = − 4.102 | p = 0.000 |

| Preoperative hospitalization | 5.5 ± 3.4 | 3.7 ± 1.7 | t = − 3.677 | p = 0.000 |

| Albumin infusion | 16.7 ± 33.1 | 1.8 ± 7.1 | t = − 3.449 | p = 0.000 |

| Preoperative HCT | 33.5 ± 4.9 | 35.2 ± 5.2 | t = 2.327 | p = 0.021 |

| Postoperative HCT | 28.2 ± 4.9 | 29.4 ± 4.8 | t = 1.641 | p = 0.102 |

| BMI | 22.2 ± 3.2 | 22.7 ± 3.2 | t = 1.080 | p = 0.281 |

| Blood transfusion volume | 1.4 + 2.1 | 0.5 ± 1.0 | t = − 3.296 | p = 0.002 |

| Preoperative leucocyte count | 9.6 ± 2.6 | 8 ± 2.1 | t = − 4.072 | p = 0.000 |

| Preoperative Hb | 11.3 ± 1.6 | 12.0 ± 5.5 | t = 0.840 | p = 0.402 |

| Preoperative albumin | 36.5 ± 3.7 | 37.8 ± 4.0 | t = 2.132 | p = 0.034 |

| Preoperative TP | 64.6 ± 4.8 | 64.7 ± 5.8 | t = 0.046 | p = 0.963 |

| NYHA | 2.2 ± 0.7 | 1.8 ± 0.6 | t = − 3.606 | p = 0.001 |

| ASA | 2.9 ± 0.5 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | t = − 7.713 | p = 0.000 |

| Anesthesia | 25/34 | 126/121 | χ2 = 1.422 | p = 0.233 |

| Surgery | 30/29 | 114/133 | χ2 = 0.421 | p = 0.516 |

| Operation time | 88.5 ± 40.3 | 79.0 ± 24.3 | t = − 1.733 | p = 0.088 |

| The anesthesia time | 157.7 ± 50.9 | 150.3 ± 33.4 | t = − 1.066 | p = 0.290 |

| Intraoperative blood loss | 127.1 ± 95.2 | 105.1 ± 33.4 | t = − 1.666 | p = 0.046 |

| Postoperative Na+ | 139.0 ± 4.7 | 139.6 ± 4.0 | t = 0.922 | p = 0.357 |

| Postoperative K+ | 4.3 ± 0.5 | 4.3 ± 0.4 | t = 0.309 | p = 0.758 |

| Postoperative leucocyte count | 9.6 ± 2.6 | 8.6 ± 2.4 | t = − 2.717 | p = 0.007 |

| Postoperative Hb | 9.4 ± 1.9 | 9.7 ± 1.6 | t = 1.237 | p = 0.217 |

| DVT (N) | 15 | 52 | t = 0.523 | p = 0.466 |

ASA American Society of Anesthesiologists, NYHA New York Heart Association, BMI body mass index, DVT deep venous thrombosis, HCT hematocrit, Hb hemoglobin, TP total protein, F female, M male, N numbers

Logistic regression analysis

Univariate logistic analysis showed that five factors including age (OR 1.090 95% CI 1.021–1.163 p = 0.009), diabetes (OR 0.330 95% CI 0.132–0.822 p = 0.017), duration of hospitalization (OR 1.106 95% CI 1.053–1.162 p = 0.000), ASA classification (OR 4.735 95% CI 1.975–11.355 p = 0.000), and albumin infusion (OR 1.051 95% CI 1.008–1.096 p = 0.020) are associated with POD (Table 3). The remaining risk factors were not significant in univariate logistic analysis. The result of five factors identified as significant in univariate analysis were included into multivariate analysis. The results indicate that age (OR 1.082 95% CI 1.026–1.140 p = 0.003), ASA classification (OR 3.022 95% CI 1.409–6.479 p = 0.004), and diabetes (OR 1.041 95% CI 1.009–1.075 p = 0.011) were independent risk factors for POD in elderly patients (Table 4). In addition, delirium was associated with prolonged hospitalization and high perioperative protein consumption.

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of the variables

| Variable | B | SE | Wals | df | p valve | OR | 95% CI for exp (B) OR |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Age | 0.086 | 0.033 | 6.727 | 1 | 0.009 | 1.090 | 1.021 | 1.163 |

| Hospitalization | 0.101 | 0.025 | 15.958 | 1 | 0.000 | 1.106 | 1.053 | 1.162 |

| Gender | 0.207 | 0.454 | 0.207 | 1 | 0.649 | 1.229 | 0.505 | 2.992 |

| Hypertension | 0.388 | 0.454 | 0.730 | 1 | 0.393 | 1.474 | 0.605 | 3.590 |

| Diabetes | − 1.110 | 0.466 | 5.664 | 1 | 0.017 | 0.330 | 0.132 | 0.822 |

| Coronary heart disease | 0.408 | 0.505 | 0.652 | 1 | 0.419 | 1.504 | 0.559 | 4.408 |

| Cerebral infarction | 0.448 | 0.603 | 0.551 | 1 | 0.458 | 1.564 | 0.480 | 5.099 |

| Albumin infusion | 0.050 | 0.021 | 5.411 | 1 | 0.020 | 1.051 | 1.008 | 1.096 |

| Preoperative Hospitalization | 0.146 | 0.093 | 2.440 | 1 | 0.118 | 1.157 | 0.964 | 1.388 |

| Preoperative HCT | − 0.015 | 0.068 | 0.047 | 1 | 0.828 | 0.985 | 0.863 | 1.125 |

| Postoperative HCT | − 0.022 | 0.81 | 0.073 | 1 | 0.787 | 0.978 | 0.835 | 1.146 |

| BMI | − 0.085 | 0.072 | 1.398 | 1 | 0.237 | 0.919 | 0.799 | 1.057 |

| Blood transfusion volume | − 0.172 | 0.182 | 0.892 | 1 | 0.345 | 0.842 | 0.589 | 1.203 |

| Preoperative leucocyte count | 0.163 | 0.100 | 2.267 | 1 | 0.105 | 1.177 | 0.967 | 1.432 |

| Preoperative albumin | − 0.050 | 0.079 | 0.401 | 1 | 0.526 | 0.951 | 0.815 | 1.110 |

| Preoperative TP | − 0.016 | 0.051 | 0.105 | 1 | 0.746 | 0.984 | 0.890 | 1.087 |

| NYHA | 0.543 | 0.323 | 2.825 | 1 | 0.093 | 1.722 | 0.914 | 3.245 |

| ASA | 1.555 | 0.446 | 12.141 | 1 | 0.000 | 4.735 | 1.975 | 11.355 |

| Anesthesia | − 0.107 | 0.462 | 0.054 | 1 | 0.817 | 0.899 | 0.363 | 2.224 |

| Operation | − 0.111 | 0.479 | 0.053 | 1 | 0.817 | 0.895 | 0.350 | 2.287 |

| The operation time | 0.014 | 0.013 | 1.162 | 1 | 0.281 | 1.014 | 0.989 | 1.040 |

| The anesthesia time | 0.016 | 0.010 | 2.511 | 1 | 0.113 | 0.984 | 0.965 | 1.004 |

| Intraoperative blood loss | 0.006 | 0.003 | 3.522 | 1 | 0.061 | 1.006 | 1.000 | 1.013 |

| Postoperative Na+ | 0.063 | 0.055 | 1.313 | 1 | 0.252 | 0.939 | 0.843 | 1.046 |

| Postoperative K+ | 0.038 | 0.449 | 0.007 | 1 | 0.932 | 0.962 | 0.399 | 2.321 |

| Postoperative leucocyte count | 0.007 | 0.099 | 0.004 | 1 | 0.947 | 1.007 | 0.829 | 1.223 |

| Postoperative Hb | 0.160 | 0.224 | 0.515 | 1 | 0.473 | 1.174 | 0.758 | 1.820 |

| DVT | 0.338 | 0.516 | 0.428 | 1 | 0.513 | 1.402 | 0.509 | 3.856 |

ASA American Society of Anesthesiologists, NYHA New York Heart Association, BMI body mass index, DVT deep venous thrombosis, HCT hematocrit, Hb hemoglobin, TP total protein, CI confidence interval, OR odds ratio, SE standard error

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis of the variables

| Variable | B | SE | Wals | df | p valve | OR | 95% CI for exp (B) OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Age | 0.079 | 0.027 | 8.546 | 8.546 | 0.003 | 1.082 | 1.026 | 1.140 |

| Hospitalization | 0.101 | 0.022 | 21.712 | 21.712 | 0.000 | 1.106 | 1.060 | 1.154 |

| Diabetes | 0.041 | 0.016 | 6.409 | 6.409 | 0.011 | 1.041 | 1.009 | 1.075 |

| Protein consumption | 1.686 | 0.369 | 20.823 | 20.823 | 0.000 | 5.396 | 2.616 | 11.131 |

| ASA | 1.106 | 0.389 | 8.077 | 8.077 | 0.004 | 3.022 | 1.409 | 6.479 |

| Anesthesia | 0.079 | 0.027 | 8.546 | 8.546 | 0.003 | 1.082 | 1.026 | 1.140 |

ASA American Society of Anesthesiologists, CI confidence interval, OR odds ratio, SE standard error

Discussion

Delirium is an important postoperative complication which can cause delayed recovery, prolonged hospitalization, and the waste of medical resources [15]. The incidence of POD in our research was 19.29% compared with the incidence rate of 13 to 48% reported by other research [6, 16]. Inouye SK reported that the occurrence of delirium following hip surgery is 12–51% [3]. A variety of diagnostic criteria may be the cause of a significant difference in the incidence of POD. A review of 25 studies showed that 11 instruments have been used to identify the delirium and the CAM was the best choice [17]. Furthermore, small simple size, inclusion criteria, surgery procedures, and anesthesia may lead to variations in incidence rates and risk factors [18, 19]. In our study, delirium was identified by nerve physician according to the evaluation tool of CAM. These measures were designed to ensure the accuracy and integrity of the study.

Although a number of theories have been proposed in an attempt to explain the processes leading to the development of delirium, there is no effective way for the prevention or treatment of POD [20]. The comprehensive assessment of the risk factors for delirium can improves the preventive measures. Many factors were supposed to be associated with POD, such as anesthesia, intraoperative blood loss, blood transfusion, malnutrition, electrolyte disorder high perioperative transfusion requirements, intraoperative pressure fluctuation, and use of benzodiazepine [5, 21, 22]. The results of our research indicate that age (> 75 years old), diabetes, and ASA classification (> 2 level) were strongly independently associated with POD.

Advanced age was consistently considered to be an overlapping risk factor in a review of 80 primary data collection studies by Dyer et al. [23, 24]. Previous studies showed that the occurrence rate of POD increased by 2% when the age of the patient increased by 1 year [4, 25]. Wang et al. [5] believe that the incidence of postoperative delirium in patients aged 70~79 years and over 80 years was higher than that in patients under 70 years old, and the odds ratio (OR) values were 6.33 and 26.37 respectively. Consistent with previous reports, our study demonstrated that the elderly patients over the age of 75 years is the independent risk factors of POD. Older patients are thought to be more susceptible because of the association between aging and the impaired physiologic compensatory capability to adjust to the physical stress of surgery [26]. The changes in the content of central neurotransmitters such as acetylcholine, norepinephrine, epinephrine, and gamma aminobutyric acid are an important cause of delirium as the age increases [27, 28]. In addition, the sensitivity of various mechanisms of blood pressure regulation in the elderly is reduced, so hypotension is easily induced in the induction period. Prolonged hypotension leads to low cerebral perfusion, cerebral ischemia, hypoxia, impairment of brain function, metabolic disorder, disorder of orientation, hallucination, irritability, etc. Edlund et al. [29] found that hypotension within a period of time (systolic pressure of < 100 mmHg) was an independent risk factor for POD and combined epidural anesthesia could lead to a decrease of at least 30% of the blood pressure in the hip joint. The mean arterial pressure fluctuated 30% relative to baseline level when the duration of hypotension lasted for 1 min, which means that the risk of stroke increased by 1.3% [30]. However, Steve [26] believes that age was not an independent risk factor for POD. One reason that age was not significant in multivariate analysis could be that this study dichotomized the age group (i.e., >75 years), while our study use yearly increments in multivariate analysis.

Diabetes is thought to increase the risk of dementia and mild cognitive impairment, as well as an accelerated cognitive decline [31] The cause of susceptibility to delirium in diabetic patients is that there is a general change in the microvascular structure of the brain: the decrease in the number of capillaries, the thickening of the basement membrane, and the increase of the arteriovenous short circuit, which makes the brain tissue more vulnerable to hypoxic damage when the perfusion pressure drops or the blood flow is not smooth [32]. The evaluation of cerebral blood flow and radiation-activity ratio of brain tissue by SPECT indicated that the decrease of senile cerebral blood flow is aggravated by hyperglycemia [33, 34]. A meta-analysis of 14 studies demonstrates that diabetic patients are more prone to cognitive dysfunction [22]. Our research shows that diabetes is associated with an increased incidence of POD, which is consistent with a prospective observational study conducted by Sabol [35], while a single systematic review concluded that diabetes was unrelated to cognitive dysfunction. Reasons for disparity from our findings are that true effect sizes for the association of diabetes with cognitive dysfunction may have been underestimated. Patients with undiagnosed diabetes were included in the respective “no diabetes” groups while the patients with confirmed diabetes were included in our study [36].

The result of our research shows that ASA classification (> 2 level) was strongly independently associated with POD. Several studies have shown that the ASA status is associated with an impaired general physical status and multiple comorbidities [37, 38]. The comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, and preoperative cognitive impairment have been previously proved to be the risk factors of delirium in elderly patients [24, 25], and our results corroborated this finding. Multiple comorbidities probably increase baseline vulnerability in older adults, contributing to POD, if combined with other precipitating factors such as major hip surgery. However, Brouquet et al. [39] believe ASA classification (> 3 level) is more likely to lead to POD in elderly patients undergoing major abdominal surgery. The reason may be due to the difference of age criteria for inclusion in the population. All consecutive patients aged 75 years or more were included in Brouquet’s study, while we focused on elderly patients aged 65 years or more.

A practical important finding of our research is that patients in delirium group need more protein consumption during the perioperative period. It accords well with the researches indicating that postoperative delirium is associated with malnutrition and nutritional supplementation could reduce the occurrence of delirium and mortality in the duration of acute trauma and after 4 months [40–42].

To sum up, we recommend that preoperatively comprehensive, accurate management of elderly patients with diabetes and comorbidity could reduce the happening of POD. Furthermore, malnutrition intervention including protein application is beneficial to recovery of patients in delirium group.

This study has some limitations. First, the selected two common types of hip surgery cannot represent the incidence of POD across all kinds of orthopedic surgery. Second, case collection does not follow the principle of randomization. Third, there are misdiagnoses for POD even when medical records were carefully checked.

Conclusion

The elderly patients over the age of 75 years with the history of diabetes or ASA classification > 2 level were at higher risk of POD. Delirium is an important postoperative complication, which had prolonged hospitalization and high perioperative albumin infusion.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81501887).

Availability of data and materials

As this paper is a retrospective study, there are no patient data sets. The search strategy for the study selection supports the conclusion of our research.

Abbreviations

- ASA

American Society of Anesthesiologists

- BMI

Body mass index

- DSM-HI-R

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

- DVT

Deep venous thrombosis

- Hb

Hemoglobin

- HCT

Hematocrit

- NYHA

New York Heart Association

- OR

Odds ratio

- POD

Postoperative delirium

- SD

Standard derivation

- TP

Total protein

Authors’ contributions

YFQ and ZJL conceived of the design of the study. XW and LCS performed and collected the data and contributed to the design of the study. CGW, YFQ, and HL prepared and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final content of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The approval was obtained from the Tianjin Medical University General Hospital Ethics Review Board. Investigators have to obtain informed consent before enrolling participants in trials.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Chen-guang Wang and Ya-fei Qin are co-first authors.

Chen-guang Wang and Ya-fei Qin contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Chen-guang Wang, Email: lhtjmu@126.com.

Ya-fei Qin, Email: 1337903734@qq.com.

Xin Wan, Email: 601118203@qq.com.

Li-cheng Song, Email: 1207434116@qq.com.

Zhi-jun Li, Email: hansontijmu@gmail.com.

Hui Li, Phone: 086-13920551011, Email: lihuitjmu@163.com.

References

- 1.Zenilman ME. Delirium: an important postoperative complication. Jama. 2017;317(1):77–78. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.18174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siddiqi N, AO H, Holmes JD. Occurrence and outcome of delirium in medical in-patients: a systematic literature review. Age Ageing. 2006;35(4):350–364. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inouye SK, Westendorp RG, Saczynski JS. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet. 2014;383(9920):911–922. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60688-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guo Y, Jia P, Zhang J, Wang X, Jiang H, Jiang W. Prevalence and risk factors of postoperative delirium in elderly hip fracture patients. J Int Med Res. 2016;44(2):317–327. doi: 10.1177/0300060515624936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang LH, Xu DJ, Wei XJ, Chang HT, Xu GH. Electrolyte disorders and aging: risk factors for delirium in patients undergoing orthopedic surgeries. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):418. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-1130-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oh ES, Sieber FE, Leoutsakos JM, Inouye SK, Lee HB. Sex differences in hip fracture surgery: preoperative risk factors for delirium and postoperative outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(8):1616–1621. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinho C, Cruz S, Santos A, Abelha FJ. Postoperative delirium: age and low functional reserve as independent risk factors. J Clin Anesthesia. 2016;33:507–513. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirsch J, DePalma G, Tsai TT, Sands LP, Leung JM. Impact of intraoperative hypotension and blood pressure fluctuations on early postoperative delirium after non-cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesthesia. 2015;115(3):418–426. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeu458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mangusan RF, Hooper V, Denslow SA, Travis L. Outcomes associated with postoperative delirium after cardiac surgery. Am J Crit Care. 2015;24(2):156–163. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2015137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scholz AF, Oldroyd C, McCarthy K, Quinn TJ, Hewitt J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of risk factors for postoperative delirium among older patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery. Br J Surg. 2016;103(2):e21–e28. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ten Broeke M, Koster S, Konings T, Hensens AG, van der Palen J. Can we predict a delirium after cardiac surgery? A validation study of a delirium risk checklist. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2018;17(3):255–261. doi: 10.1177/1474515117733365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen W, Ke X, Wang X, Sun X, Wang J, Yang G, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for postoperative delirium in total joint arthroplasty patients: a prospective study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;46:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2017.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krogseth M, Wyller TB, Engedal K, Juliebo V. Delirium is a risk factor for institutionalization and functional decline in older hip fracture patients. J Psychosom Res. 2014;76(1):68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muangpaisan W, Wongprikron A, Srinonprasert V, Suwanpatoomlerd S, Sutipornpalangkul W, Assantchai P. Incidence and risk factors of acute delirium in older patients with hip fracture in Siriraj Hospital. J Med Assoc Thai. 2015;98(4):423–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brooks PB. Postoperative delirium in elderly patients. Am J Nurs. 2012;112(9):38–49. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000418922.53224.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scholtens RM, van Munster BC, van Faassen M, van Kempen MF, Kema IP, de Rooij SE. Plasma melatonin levels in hip fracture patients with and without delirium: a confirmation study. Mech Ageing Dev. 2017;167:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2017.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong CL, Holroyd-Leduc J, Simel DL, Straus SE. Does this patient have delirium?: value of bedside instruments. Jama. 2010;304(7):779–786. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruce AJ, Ritchie CW, Blizard R, Lai R, Raven P. The incidence of delirium associated with orthopedic surgery: a meta-analytic review. Int Psychogeriatrics. 2007;19(2):197–214. doi: 10.1017/S104161020600425X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dasgupta M, Dumbrell AC. Preoperative risk assessment for delirium after noncardiac surgery: a systematic review. J Am Geriatrics Soc. 2006;54(10):1578–1589. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martocchia A, Curto M, Comite F, Scaccianoce S, Girardi P, Ferracuti S, et al. The prevention and treatment of delirium in elderly patients following hip fracture surgery. Recent Pat CNS Drug Discov. 2015;10(1):55–64. doi: 10.2174/1574889810666150216152624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mazzola P, Ward L, Zazzetta S, Broggini V, Anzuini A, Valcarcel B, et al. Association between preoperative malnutrition and postoperative delirium after hip fracture surgery in older adults. J Am Geriatrics Soc. 2017;65(6):1222–1228. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feinkohl I, Winterer G, Pischon T. Diabetes is associated with risk of postoperative cognitive dysfunction: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2017;33(5). 10.1002/dmrr.2884. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Trabold B, Metterlein T. Postoperative delirium: risk factors, prevention, and treatment. J Cardiothoracic Vasc Anesthesia. 2014;28(5):1352–1360. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2014.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dyer CB, Ashton CM, Teasdale TA. Postoperative delirium. A review of 80 primary data-collection studies. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(5):461–465. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1995.00430050035004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hassanzadeh H, Jain A, Tan EW, Stein BE, Van Hoy ML, Stewart NN, et al. Postoperative incentive spirometry use. Orthopedics. 2012;35(6):e927–e931. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20120525-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Castro SM, Unlu C, Tuynman JB, Honig A, van Wagensveld BA, Steller EP, et al. Incidence and risk factors of delirium in the elderly general surgical patient. Am J Surg. 2014;208(1):26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inouye SK, Charpentier PA. Precipitating factors for delirium in hospitalized elderly persons. Predictive model and interrelationship with baseline vulnerability. Jama. 1996;275(11):852–857. doi: 10.1001/jama.1996.03530350034031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qiu Y, Huang X, Huang L, Tang L, Jiang J, Chen L, et al. 5-HT(1A) receptor antagonist improves behavior performance of delirium rats through inhibiting PI3K/Akt/mTOR activation-induced NLRP3 activity. IUBMB life. 2016;68(4):311–319. doi: 10.1002/iub.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edlund A, Lundstrom M, Brannstrom B, Bucht G, Gustafson Y. Delirium before and after operation for femoral neck fracture. J Am Geriatrics Soc. 2001;49(10):1335–1340. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bijker JB, Persoon S, Peelen LM, Moons KG, Kalkman CJ, Kappelle LJ, et al. Intraoperative hypotension and perioperative ischemic stroke after general surgery: a nested case-control study. Anesthesiology. 2012;116(3):658–664. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182472320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cukierman T, Gerstein HC, Williamson JD. Cognitive decline and dementia in diabetes--systematic overview of prospective observational studies. Diabetologia. 2005;48(12):2460–2469. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-0023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaw S, Wang X, Redd H, Alexander GD, Isales CM, Marrero MB. High glucose augments the angiotensin II-induced activation of JAK2 in vascular smooth muscle cells via the polyol pathway. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(33):30634–30641. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305008200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirao K, Hanyu H, Sato T, Kanetaka H, Shimizu S, Sakurai H, et al. A longitudinal SPECT study of different patterns of regional cerebral blood flow in alzheimer’s disease with or without diabetes. Dementia and geriatric cognitive disorders extra. 2011;1(1):62–74. doi: 10.1159/000323865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaplar M, Paragh G, Erdei A, Csongradi E, Varga E, Garai I, et al. Changes in cerebral blood flow detected by SPECT in type 1 and type 2 diabetic patients. J Nucl Med. 2009;50(12):1993–1998. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.066068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi CM, Wang DX, Chen KS, Gu XE. Incidence and risk factors of delirium in critically ill patients after non-cardiac surgery. Chin Med J. 2010;123(8):993–999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beagley J, Guariguata L, Weil C, Motala AA. Global estimates of undiagnosed diabetes in adults. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103(2):150–160. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alves A, Panis Y, Mantion G, Slim K, Kwiatkowski F, Vicaut E. The AFC score: validation of a 4-item predicting score of postoperative mortality after colorectal resection for cancer or diverticulitis: results of a prospective multicenter study in 1049 patients. Ann Surg. 2007;246(1):91–96. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3180602ff5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Belghiti J, Hiramatsu K, Benoist S, Massault P, Sauvanet A, Farges O. Seven hundred forty-seven hepatectomies in the 1990s: an update to evaluate the actual risk of liver resection. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191(1):38–46. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(00)00261-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brouquet A, Cudennec T, Benoist S, Moulias S, Beauchet A, Penna C, et al. Impaired mobility, ASA status and administration of tramadol are risk factors for postoperative delirium in patients aged 75 years or more after major abdominal surgery. Ann Surg. 2010;251(4):759–765. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181c1cfc9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olofsson B, Stenvall M, Lundstrom M, Svensson O, Gustafson Y. Malnutrition in hip fracture patients: an intervention study. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16(11):2027–2038. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lundstrom M, Olofsson B, Stenvall M, Karlsson S, Nyberg L, Englund U, et al. Postoperative delirium in old patients with femoral neck fracture: a randomized intervention study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2007;19(3):178–186. doi: 10.1007/BF03324687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duncan DG, Beck SJ, Hood K, Johansen A. Using dietetic assistants to improve the outcome of hip fracture: a randomised controlled trial of nutritional support in an acute trauma ward. Age Ageing. 2006;35(2):148–153. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afj011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

As this paper is a retrospective study, there are no patient data sets. The search strategy for the study selection supports the conclusion of our research.