Abstract

Background

The lunge is a closed kinetic chain exercise that athletes frequently use as part of training and rehabilitative programs. While typically performed on a stable surface, modifications include the use of balance platforms to create an unstable surface and suspension equipment. Suspension training exercises are theorized to be higher demand exercises and may be considered a progression from exercises on stable surfaces. Comparison of muscle recruitment between the suspended lunge and the standard lunge has not been reported.

Hypothesis and purpose

The purpose was to compare differences in muscle recruitment between a standard lunge and a suspended lunge. We hypothesized that hip and thigh muscle recruitment with a suspended lunge would be greater than a standard lunge due to less inherent support with the suspended lunge exercise.

Study Design

Analytic, observational cross-sectional study design.

Methods

Thirty healthy participants (15 male and 15 female) voluntarily participated in this study. Electromyographic (EMG) muscle recruitment was measured in five hip and thigh muscles while performing a standard and suspended lunge. EMG was expressed as a percentage of EMG with a maximal voluntary isometric contraction (MVIC).

Results

Recruitment was significantly greater in the suspended lunge condition compared to the standard lunge for the hamstrings (p < .001), gluteus medius (p < .001), gluteus maximus (p<.001), and adductor longus (p < .001). There was no significant difference in rectus femoris recruitment between conditions (p = .154).

Conclusion

Based on EMG findings, the suspended lunge is a more demanding exercise for hip muscles, compared to the standard lunge.

Level of evidence

Level 3 Mechanism-based reasoning intervention study trial.

Clinical relevance

The results of this study can assist clinicians in designing and progressing lower extremity exercise programs. With greater muscle recruitment, the suspended lunge is a more demanding exercise for hip muscles and can be considered a progression of the standard lunge as part of an exercise program

What is known about the subject?

Muscle recruitment associated with the lunge exercise, variations of the lunge, and similar exercises has been reported. The use of suspension training exercise equipment has been reported for upper extremity exercises however not for the lower extremity.

What does this study add to existing knowledge?

Results of this study provide novel EMG information related to the lunge exercise using suspension training exercise equipment. Clinicians can use this information designing lower extremity exercise programs.

Keywords: Electromyography, Exercise Therapy, Lunge, Suspension Training

INTRODUCTION

The lunge is a closed kinetic chain functional multi-joint exercise that replicates movements found in sports and common daily activities.1 Clinicians use both closed kinetic chain and open kinetic chain exercises for lower extremity programs with closed kinetic chain exercises such as the lunge generally favored due to functional implications. Lower extremity exercises such as the lunge may be used with the goal of enhancing the performance of muscles surrounding the hip. Common lower extremity conditions that may benefit from enhancing hip muscle performance include, but not exclusive to patellofemoral pain,2 anterior cruciate ligament injury,3 and iliotibial band syndrome.4

Based on electromyographic (EMG) levels of muscle recruitment, the standard lunge exercise has been shown to produce low to moderate EMG levels for hip and thigh musculature.1,5,6. EMG levels found with the standard lunge have been compared to modified lunge techniques as well as similar lower extremity exercises. Investigating the influence of trunk position on EMG activation with a standard lunge, Farrokhi et al.5 found that a forward trunk lean during the standard lunge exercise significantly increased gluteus maximus and biceps femoris EMG levels when compared to an upright trunk position. Recruitment of the vastus lateralis was not significantly different between the two conditions. Comparing the lunge to similar exercises, Boudreau et al.6 found the rectus femoris, gluteus maximus, and gluteus medius were recruited in a progression from least to greatest during a single-leg step-up-and-over-lunge, standard lunge, and single leg squat. Support provided by both extremities was hypothesized as a contributing factor to the step-up-and-over-lunge and standard lunge having lower EMG levels as compared to the single leg squat.

The use of suspension exercise equipment has become popular in the athletic community. Use of these devices decreases the stability component of an exercise which increases muscular demands while performing comparable exercises7. For example, performing upper extremity exercises, such as the push-up, using suspension training equipment requires more muscle recruitment as compared to a standard push-up.8,9 To our knowledge, the use of suspension training equipment for lower extremity exercises is not reported. The purpose of this study was to investigate differences in muscle recruitment between a standard lunge and a suspended lunge exercise. We hypothesized that muscle recruitment in a suspended lunge would be greater than a standard lunge.

METHODS

Participants

Thirty healthy participants (15 male and 15 female) with a mean age of 23.9 ± 1.7 years volunteered to participate in this study (BMI: 24.21 ± 2.88). Participants were recruited via word of mouth. Based on an a priori power analysis, 24 or more participants were needed to detect differences in recruitment of 10% maximal voluntary isometric contraction (MVIC) or greater (effect size = 0.6) among the two testing positions, assuming correlations among repeated measures of .75 or greater, at 80% power and at alpha = .05 . We recruited a sample size 25% greater than that indicated by the power analysis to offset potential attrition.

Inclusionary criteria included healthy individuals between the age of 18 and 30 years old with the ability to perform three consecutive repetitions of the two chosen exercises. Exclusionary criteria included any current pain, pathology, trauma, or lower extremity surgery that would compromise ability to perform the lunge exercises. Prior to beginning study procedures, all participants provided signed consent. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the author's institution.

Instrumentation

A TRX® suspension trainer (San Francisco, CA) was used for the suspended lunge. The trainer was anchored to a support beam approximately eight feet above the floor.

Raw EMG signals were collected at 1000 Hz through a 16-bit NI-DAQ PCI-6220 AD card (National Instruments Corporation, Austin TX) with BagnoliTM DE 3.1 double differential surface EMG sensors and a Bagnoli-16 amplifier (Delsys Inc., Boston, MA). The sensor contacts were made from 99.9% pure silver bars 10 mm in length and spaced 10 mm apart. The preamplifiers had a gain of 10 v/v. The combined preamplifier and main amplifier permitted a gain from 100 to 10,000 Hz. The common mode rejection ratio was 92 dB at 60 Hz, input impedance was greater than 1015 Ω at 100 Hz and estimated noise was less than 1.2 μV. Raw EMG signals were processed with EMGworks Data Acquisition and Analysis software (Delsys Inc., Boston, MA).

Procedures

This analytic, observational cross-sectional study was conducted in a research laboratory setting. Study procedures were explained to the participants upon arrival after which signed informed consent was provided. Participants rode on a stationary bike for five minutes as a warm-up. They were next screened to determine their ability to conduct three consecutive repetitions of a standard lunge. To determine leg dominance, participants were asked with which leg they would kick a ball.5 Electrodes were placed on the dominant limb rectus femoris, gluteus medius, gluteus maximus, hamstrings, and adductor longus as described by Criswell.10 The rectus femoris electrode was placed on the anterior thigh half the distance between the anterior inferior iliac spine and proximal border of the patella. The gluteus medius electrode was along the proximal third of the distance between the most superior point of the iliac crest and the greater trochanter. The gluteus maximus electrode was placed halfway between the greater trochanter and the sacral spine. The hamstring electrode was placed on the posterior thigh half the distance from gluteal fold to the popliteal fossa. The adductor longus was palpated during an isometric contraction and the electrode was placed directly over the muscle belly about 4 cm from the pubic tubercle. The skin where the electrodes were placed was scrubbed thoroughly with alcohol wipes to reduce surface impedance. All electrodes were placed in parallel with the muscle's line of action.

Prior to performing the lunge exercises, EMG for the tested muscles was recorded during a “make test” in which the subject performed a maximal contraction over a period of five seconds.5 After instruction and a submaximal practice bout, a single MVIC was performed. Verbal encouragement was provided by examiners during each MVIC recording. For the gluteus maximus MVIC test, the subject was positioned prone on a treatment table with a pillow under their abdomen. The knee was flexed to 90 °. A belt was looped around the table and the distal thigh with a towel placed between the belt and the thigh for comfort. The subject raised their thigh into the belt pushing their heel toward the ceiling.11 For the gluteus medius, the subject was positioned sidelying on the non-dominant side. The test leg was extended to neutral and supported with a small step stool in approximately 5 ° of hip abduction. A belt was wrapped under the table and over the superior surface of the test leg just proximal to the lateral malleolus. The subject performed the MVIC by raising their leg against the belt.11 To test the hamstring, the subject was positioned in prone with a pillow under the abdomen. The knee of the test leg was flexed to 90 °. The examiner provided resistance at the subject's ankle as the subject attempted to flex the knee.11 The rectus femoris was tested in supine. The dominant leg was positioned in about 30 ° of hip flexion with the knee extended. The examiner provided resistance just proximal to the ankle as the subject attempted to raise the leg towards the ceiling. The adductor longus was tested with the subject positioned in side-lying on the dominant leg side. The non-dominant hip was flexed with the knee resting on a stool. The examiner provided a force proximal to the knee as the subject attempted to lift their leg.12

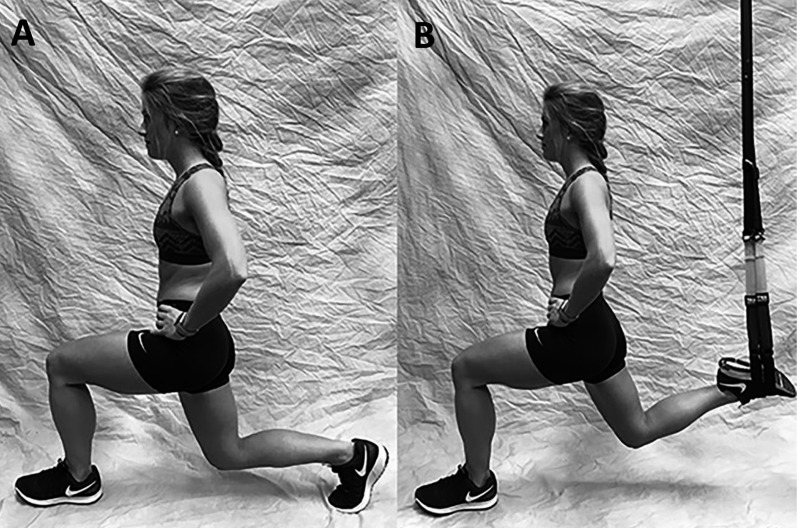

The order of lunge exercise was randomized. Each lunge exercise was verbally explained and visually demonstrated. Illustrations of the exercises can be seen in Figure 1. The subject was allowed to practice prior to recording the lunge trial. The standard lunge was performed by positioning the foot of the dominant leg forward a distance equal to a measurement from the greater trochanter to the floor.5 Once positioned, the subject performed the lunge by flexing their forward knee to 90 degrees.1 The trunk was maintained in a vertical position. The subject's hands were maintained on hips. The pace of descent and ascent were each three seconds in duration with a one to two second hold at the 90˚ knee flexion position. A metronome was used for pacing. The lunge depth and trunk position were monitored visually by the examiner. Three consecutive lunges were performed.

Figure 1.

Full knee flexion position for standard lunge (A) and suspended lunge (B).

The suspended lunge was performed with the dorsum of the non-dominant foot placed in the suspension strap loop. The level of the TRX® suspension loop was adjusted and positioned to place the tibia parallel to the floor. The subject performed the lunge by sliding the suspended limb along with the torso in a posterior direction and flexing the forward knee to 90˚. The pace of exercise, vertical trunk position and hand position was the same as during the standard lunge

Data Processing

EMG signals were band-pass filtered between 20 and 450 Hz with a 4th order Butterworth filter and processed with a room mean square algorithm over 200-ms time constants with sliding windows. To standardize our EMG analysis, we identified from the rectus femoris EMG signal the descending and ascending phases of each lunge repetition. We subsequently analyzed data from the ascending phases only. During the ascending phase of each lunge repetition, we identified peak EMG recruitment from each muscle and analyzed the mean EMG signal over a one-second duration surrounding the peak. Our method for selecting EMG signals to analyze was similar to that of Farokhi et al,5 and enabled us to avoid analyzing low levels of EMG recruitment during lunge cycles that commonly occur at movement initiation and termination. Data for each participant were averaged across three lunge repetitions in both conditions.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Descriptive statistics (mean and SD) for normalized EMG data were calculated and the distributions examined to assess whether data were normally distributed. Based on Shapiro-Wilk tests, data from eight of the 10 distributions departed significantly (p < .05) from being normally distributed. We therefore transformed the EMG data with natural logarithmic transformations and subsequently conducted our inferential statistical analyses with the transformed data. We next compared EMG data between the two lunge conditions with a repeated measures analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), using participant sex as a covariate in the analysis since others have reported sex differences in muscle recruitment in similar exercises.13,14 All inferential tests were conducted at α = .05. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 22.0 software (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

All participants that entered the study completed both exercise conditions. Significantly greater EMG muscle recruitment was found in the suspended lunge condition compared to the standard lunge for the hamstrings (p = .001), gluteus medius (p < .001), gluteus maximus (p<.001), and adductor longus (p < .001). No significant difference was found in rectus femoris EMG recruitment between conditions (p = .434). Data are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of muscle recruitment (% maximal voluntary isometric contraction) in the standard and suspended lunge conditions, adjusted for sex differences* in recruitment.

| Muscle | Standard lunge (Mean ± SD)† | Suspended lunge (Mean ± SD)† | 95% CI of difference | F-ratio | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rectus femoris | 22.1 ± 22.2 | 24.5 ± 22.0 | -0.3 to 6.9 | 0.630 | .434 |

| Hamstring | 8.7 ± 13.2 | 13.1 ± 20.1 | 3.0 to 9.9 | 14.001 | .001 |

| Gluteus medius | 15.3 ± 11.4 | 24.1 ± 15.1 | 6.3 to 12.4 | 57.569 | <.001 |

| Gluteus maximus | 12.9 ± 8.9 | 19.5 ± 10.1 | 4.6 to 9.2 | 37.250 | <.001 |

| Adductor longus | 9.7 ± 8.3 | 16.6 ± 13.3 | 5.0 to 11.2 | 24.196 | <.001 |

Notes: *Female participants recruited the gluteus medius to a greater extent than male participants (24.4% MVIC vs 15.1%, p = .024) across both testing conditions; analysis of unadjusted recruitment between standard and suspended lunges yields a similar statistical outcome (F = 65.679, p < .001).

Mean values represent reverse natural log transformed data so data reflect % MVIC values.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to compare magnitudes of muscle recruitment between the standard lunge and the suspended lunge. We hypothesized that muscle recruitment in a suspended lunge would be greater than a standard lunge as a result of the unstable support for the trailing limb with the suspended lunge exercise. Our hypothesis was confirmed with four of the five muscles tested with the gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, hamstrings, and adductor longus demonstrating significantly greater muscle fiber recruitment. The rectus femoris did not have significantly greater muscle recruitment in the suspended lunge compared to the standard lunge. We hypothesize that the rectus femoris worked similarly in both exercises to control the motion at the hip and knee (of flexion and extension), whereas the other muscles were recruited in greater magnitude with the suspended lunge in order to stabilize the hip and pelvis in the frontal and transverse planes. Similar to our results, Farrokhi et al.5 did not find a difference in quadriceps recruitment with varied trunk positions during a squat exercise which may suggest quadriceps muscle recruitment is more related to body weight load than stability.

We expressed muscle recruitment as a percent of the MVIC. Digiovine et al.15 categorized EMG muscle recruitment greater than 60% MVIC as Very High, 41-60% MVIC as High, 21-40% MVIC as Moderate, and 0-20% MVIC as Low levels of recruitment. Based on these categories we found the rectus femoris muscle had a moderate level of muscle recruitment in both the standard and suspended lunge conditions. The gluteus medius moved from a low level of recruitment in the standard lunge to a moderate level of recruitment in the suspended lunge. The remaining muscles were in the low level of recruitment for both lunges however, all five muscles demonstrated statistically greater muscle recruitment (normalized to MVIC) in the suspended lunges as compared to standard lunges.

The low and moderate levels of muscle recruitment for the standard lunge have been reported previously.1,5,6 With a standard lunge, Boudreau et al.6 found the gluteus maximus and adductor muscle groups were in the moderate level of recruitment with the rectus femoris and gluteus medius groups in the low level of recruitment. Some of the difference in levels of activation as compared to our results may be explained by different methods utilized to establish the MVIC's of the tested muscles. Whereas we tested muscles with the subject lying on a plinth, Boudreau tested participants in standing resulting in a different reference to determine the percent MVIC. Ekstrom et al.1 reported the gluteus maximus and gluteus medius to achieve the moderate level of recruitment with the hamstrings achieving only the low level of recruitment. The standard lunge was performed by stepping forward with the lead leg and holding a five-second isometric contraction with the lead leg knee flexed 90 ° then returning to the starting position. The timing of the descent and ascent phases were not described other than being performed slowly. Similar to our findings, Farrokhi et al.5 reported that the gluteus maximus and hamstrings achieved the low level of muscle recruitment for the standard lunge.

Muscle recruitment in the standard lunge has been compared to other single-leg closed kinetic chain exercises including the single-leg step up and single-leg squat. Boudreau et al.6 reported increasingly greater muscle recruitment for the gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, and rectus femoris starting with the single-leg step up (16.5%, 15.2%, 10.8%, respectively), to the standard lunge (21.7%, 17.7%, 19.1%), and greatest recruitment being achieved with the single-leg squat (35.2%, 30.1%, 26.7%). Our results for recruitment during the standard lunge were similar for the same muscles. While muscle recruitment of the gluteus maximus, gluteus medius and rectus femoris for the suspended lunge in our study was less than the single-leg squat reported in the Boudreau et al.6 study, the suspended lunge may fit between the standard lunge and single-leg squat in the progression of lower extremity exercises, based upon magnitude of muscle recruitment (%MVIC).

Our study recruited healthy participants between the ages of 18 and 30 years, thus we are unable to report how lower extremity pathology or older and younger participants may affect muscle activation patterns. While it was determined that EMG muscle recruitment of the gluteus medius was greater in females, our purpose was to investigate the difference between lunge conditions, not between men and women. The study was under-powered to investigate this difference, risking a type 2 error for sex comparisons. Future studies should investigate if lower extremity pathology and/or sex differences influence muscle recruitment patterns when performing a lunge or suspended lunge.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate that the suspended lunge is a more demanding exercise compared to the standard lunge, requiring greater muscle recruitment of the gluteus maximus, gluteus medius, hamstrings and adductor longus than with the standard lunge exercise. Therefore, the suspended lunge can be viewed as a progression from the standard lunge. Clinicians can use this information in designing exercise and physical therapy rehabilitation programs.

References

- 1.Ekstrom RA Donatelli RA Carp KC. Electromyographic analysis of core trunk, hip, and thigh muscles during 9 rehabilitation exercises. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2007;37(12):754-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hewett TE Myer GD Ford KR, et al. Biomechanical measures of neuromuscular control and valgus loading of the knee predict anterior cruciate ligament injury risk in female athletes a prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(4):492-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Souza RB Powers CM. Differences in hip kinematics, muscle strength, and muscle activation between subjects with and without patellofemoral pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39(1):12-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fredericson M Cookingham CL Chaudhari AM Dowdell BC Oestreicher N Sahrmann SA. Hip abductor weakness in distance runners with iliotibial band syndrome. Clin J Sport Med. 2000;10(3):169-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farrokhi S Pollard CD Souza RB Chen YJ Reischl S Powers CM. Trunk position influences the kinematics, kinetics, and muscle activity of the lead lower extremity during the forward lunge exercise. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008;38(7):403-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boudreau SN Dwyer MK Mattacola CG Lattermann C Uhl TL McKeon JM. Hip-muscle activation during the lunge, single-leg squat, and step-up-and-over exercises. J Sport Rehabil. 2009;18(1):91-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris S Ruffin E Brewer W Ortiz A. Muscle activation patterns during suspension training exercises. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2017;12(1):42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Snarr RL Esco MR. Electromyographic comparison of traditional and suspension push-ups. J Hum Kinet. 2013;39(1):75-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGill SM Cannon J Andersen JT. Analysis of pushing exercises: Muscle activity and spine load while contrasting techniques on stable surfaces with a labile suspension strap training system. J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28(1):105-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Criswell E. Cram's introduction to surface electromyography. second ed: Jones & Bartlett Publishers; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hislop H Avers D Brown M. Daniels and Worthingham's Muscle Testing-E-Book: Techniques of Manual Examination and Performance Testing. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krause DA Schlagel SJ Stember BM Zoetewey JE Hollman JH. Influence of lever arm and stabilization on measures of hip abduction and adduction torque obtained by hand-held dynamometry. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(1):37-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeller BL McCrory JL Kibler WB Uhl TL. Differences in kinematics and electromyographic activity between men and women during the single-legged squat. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(3):449-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dwyer MK Boudreau SN Mattacola CG Uhl TL Lattermann C. Comparison of lower extremity kinematics and hip muscle activation during rehabilitation tasks between sexes. J Athl Train. 2010;45(2):181-190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Digiovine NM Jobe FW Pink M Perry J. An electromyographic analysis of the upper extremity in pitching. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1992;1(1):15-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]