Abstract

Sorghum is a multipurpose crop that is cultivated worldwide. Plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) have important roles in enhancing sorghum biomass and nutrient uptake and suppressing plant pathogens. The aim of this research was to test the effects of the endophytic bacterial species Kosakonia radicincitans strain IAC/BECa 99, Enterobacter asburiae strain IAC/BECa 128, Pseudomonas fluorescens strain IAC/BECa 141, Burkholderia tropica strain IAC/BECa 135 and Herbaspirillum frisingense strain IAC/BECa 152 on the growth and root architecture of four sorghum cultivars (SRN-39, Shanqui-Red, BRS330, BRS509), with different uses and strigolactone profiles. We hypothesized that the different bacterial species would trigger different growth plant responses in different sorghum cultivars. Burkholderia tropica and H. frisingense significantly increased the plant biomass of cultivars SRN-39 and BRS330. Moreover, cultivar BRS330 inoculated with either strain displayed isolates significant decrease in average root diameter. This study shows that Burkholderia tropica strain IAC/BECa 135 and H. frisingense strain IAC/BECa 152 are promising PGPB strains for use as inocula for sustainable sorghum cultivation.

Keywords: Nutrient uptake, Plant biomass, Phosphorus solubilizer, Plant growth-promoting bacteria, Strigolactone, Root architecture

Introduction

The plant sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) originated on the African continent and is cultivated worldwide (Rao et al., 2014). Sorghum has a short growth period, and is therefore a preferred cereal in arid and semi-arid regions (Farre & Faci, 2006; Wu et al., 2010; Funnell-Harris, Sattler & Pedersen, 2013). In Africa, sorghum is mainly cultivated by small farmers as staple food and for beverage production (Haiyambo, Reinhold-Hurek & Chimwamurombe, 2015). By contrast, sorghum is mostly used for the feed market in North and Central America and for animal feedstock, ethanol production, and soil coverage in South America (Dutra et al., 2013; Perazzo et al., 2013; Damasceno, Schaffert & Dweikat, 2014; Rao et al., 2014). Sorghum is currently the fifth most cultivated cereal worldwide (Ramu et al., 2013) and in 2014, approximately 71 million tons of sorghum grains were produced around the world (FAO, 2018).

Sorghum producers often face yield problems due to soil nutrient deficits, limited access to chemical fertilizers, and the frequent need to combat plant pathogens (Haiyambo, Reinhold-Hurek & Chimwamurombe, 2015). Although conventional agricultural methods, such as chemical fertilization and pesticide application, can be used to overcome these limitations, the environmental side effects of these practices may be unsustainable As an alternative, the use of plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) as biofertilizers not only enhances plant biomass and nutrient uptake but also improves pathogen control (Bhattacharyya & Jha, 2012; Dawwam et al., 2013). PGPB can alter the root architecture and promote plant growth by directly facilitating nutrient acquisition or modulating plant hormone levels or by indirectly inhibiting pathogenic organisms (Bhattacharyya & Jha, 2012; Glick, 2012). The best-known processes of plant nutrient acquisition mediated by PGPB are nitrogen fixation, phosphate (P) solubilization and iron sequestration (Lucy, Reed & Glick, 2004). Different groups of bacteria produce plant growth regulators, such as cytokinins, gibberellins, indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), and ethylene, that may also affect the plant’s hormonal balance (Amara, Khalid & Hayat, 2015). Moreover, PGPB can promote plant growth by fixing N2 and inhibiting plant pathogens by producing antibiotics or lytic enzymes or competing for resources, which can limit disease incidence and severity (Glick, 2012; Da Silveira et al., 2016). In addition to the bacterial modification of plant metabolism, plant exudates have the potential to modify rhizosphere microbial community assembly and interactions (Haichar et al., 2014; Vurukonda et al., 2016). Recent studies suggest that the plant hormone strigolactone (SL) plays an important role in plant rhizosphere bacterial community composition (Funnell-Harris, Pedersen & Marx, 2008; Schlemper et al., 2017). Furthermore, Peláez-Vico et al. (2016) showed that the PGPB Sinorhizobium meliloti reduces orobanchol and orobanchyl acetate levels in nodulated alfalfa plants under P starvation, suggesting a role of SL in rhizobial–legume interactions. In a in vitro assay, Peláez-Vico et al. (2016) demonstrated that swarming motility of Sinorhizobium meliloti is triggered by the synthetic SL analogue GR24.

Many aspects of the interaction between PGPB and plants have been addressed for a wide range of plant species. Specifically in sorghum, some studies have focused on the interaction of PGPB strains isolated from third-party host species as inoculants for the sorghum rhizosphere (Matiru & Dakora, 2004; Dos Santos et al., 2017), whereas other works have reported the inoculation in other plant species of bacterial strains isolated from sorghum.

Matching beneficial bacteria with their preferred crops might optimize root colonization and biocontrol (Raaijmakers & Weller, 2001), especially when different plants are cropped in soils with the same bacterial composition. In this context, it is extremely important to identify bacterial candidates that have similar growth effects on plants that share the same soil. In Brazil, sorghum have been planted during the sugarcane off season as well as in former sugarcane fields (May et al., 2013), and therefore sorghum and sugarcane are frequently exposed to the same soil. Endophytic bacteria with plant growth-promoting traits isolated from sugarcane have been shown to increase biomass and plant N content when inoculated in plantlets of sugarcane. For example, Govindarajan et al. (2006) observed an increase in sugarcane yield of 20%, while Sevilla et al. (2001) observed increases of 31% in plant dry matter, 43% in N accumulation, and 25% in productivity in two sugarcane varieties. We hypothesized that different bacterial species isolated from sugarcane will trigger different growth plant responses in different sorghum cultivars. Thus, to determine if endophytic strains characterized as PGPB in sugarcane can act as non-host-specific PGPB benefiting sorghum performance, we tested the effect of five bacterial strains on the plant biomass and root architecture of four Sorghum bicolor cultivars with different uses and characteristics: SRN-39, an African grain cultivar that produces high amounts of orobanchol; Shanqui-Red (SQR), a Chinese cultivar that produces high amount of 5-deoxystrigol; BRS330, a hybrid grain cultivar from Brazil and BRS509, a hybrid saccharin cultivar from Brazil that produces both orobanchol and sorgomol (Schlemper et al., 2017).

Inoculation of the cultivars SRN-39 and BRS330 with Burkholderia tropica or Herbaspirillum frisingense strains resulted in significant increases in plant biomass. Moreover, cultivar BRS330 exhibited significant increases in average root diameter when inoculated with either strain. This study shows that Burkholderia tropica strain IAC/BECa 135 and H. frisingense strain IAC/BECa 152 are promising PGPB strains for use as inocula for sustainable sorghum cultivation.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial isolates and screening of plant growth promotion traits

Five bacterial endophytic strains isolated from sugarcane stem belonging to Agronomic Institute of Campinas (IAC)—Brazil culture collection were used for this experiment: Kosakonia radicincitans strain IAC/BECa-99 (KF542909.1), Enterobacter asburiae strain IAC/BECa-128 (JX155407.1), Pseudomonas fluorescens strain IAC/BECa-141 (KJ588202.1), Burkholderia tropica strain IAC/BECa-135 (KJ670083.1), and H. frisingense strain IAC/BECa-152 (JX155400.1).

Phosphate solubilization test: the strains were cultured on culture medium containing inorganic phosphate (CaHPO4) according to the method of Katznelson & Bose (1959). The experiment was performed in triplicate for 5 days. The ability of the bacteria to solubilize calcium phosphate was verified by the formation of a clear halo surrounding the colonies.

Indole-3-acetic acid test: the strains were grown in culture medium containing L-tryptophan, the precursor of IAA (Bric, Bostock & Silverstone, 1991), covered with a nitrocellulose membrane, and incubated at 28 °C in the dark for 24 h. The nitrocellulose membranes were immersed in Salkowski’s solution and incubated at room temperature for up to 3 h. The formation of a red-purplish halo around the colonies indicated IAA production.

Siderophore production: siderophore production by the strains was measured using the method of Schwyn & Neilands (1987), in which a dye, chromeazurol S (CAS), is released from a dye-iron complex when a ligand sequesters the iron complex. This release causes a color change from blue to yellow–orange. In this case, the ligant was one or more of the siderophores found in the culture supernatants of the bacterial strains.

Hydrogen cyanide (HCN) test: the production of HCN by all strains was assessed according to Bakker & Schippers (1987). Moistened filter paper with picric acid solution (5%) and Na2CO3 (2%) was added to the top of the Petri dishes and incubated at 28 °C for 36 h. The experiments were performed in triplicate for each strain, and a colour change of the paper from yellow to orange–red indicated the ability to produce HCN.

Antifungal activity assay by paired culture (PC) test: the antagonistic properties of the strains against two pathogenic fungi, Bipolaris sacchari and Ceratocystis paradoxa, were evaluated using the PC method. The fungi were cultured in Petri dishes containing PDA medium for 7 days (C. paradoxa) and 10 days (Bipolaris sacchari). For the PC tests, the bacterial strains (grown in DYGS liquid medium for 4 days) were arranged as streaks on one side of the Petri dish with PDA medium; 5 mm of PDA culture medium containing the pathogen mycelial disc was placed on the opposite side. The control treatment contained only the pathogen mycelial disc of the pathogen. An antagonistic reaction was confirmed by the formation of a zone of inhibition (haloes without mycelial growth). The tests were performed using five replicates per treatment.

Sorghum cultivars

Four sorghum cultivars differing in use, origin, and strigolactone production were chosen for inoculation with the selected PGPB. The cultivars were SRN-39, an African sorghum that produces a high amount of orobanchol; SQR a Chinese sorghum that produces mostly 5-deoxystrigol; BRS330, a hybrid Sorghum bicolor grain from Brazil; and BRS509, a hybrid Sorghum bicolor saccharin from Brazil that produces both 5-deoxystrigol and sorgomol.

Mesocosm experiment

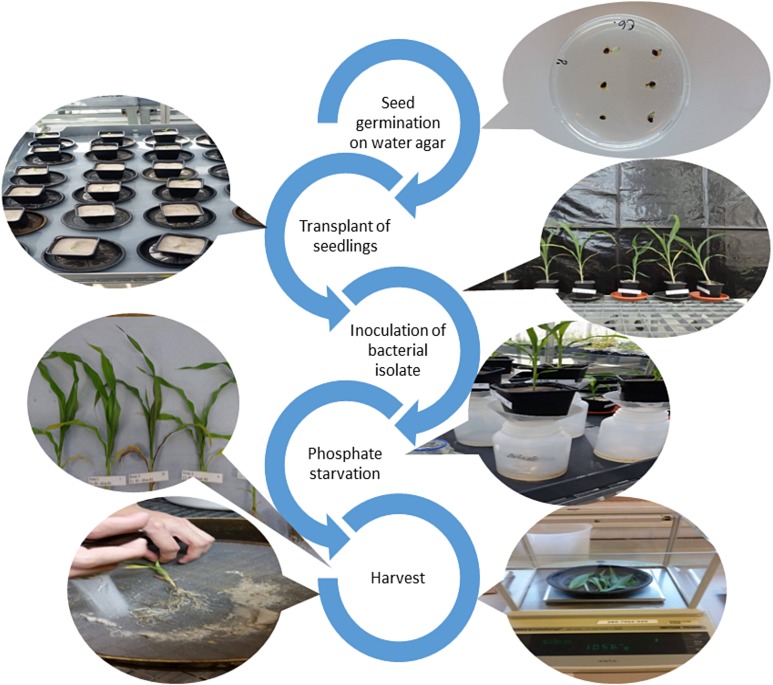

The experiment was performed in a greenhouse of the Netherlands Institute of Ecology (NIOO-KNAW), located in Wageningen, the Netherlands. The experiment was carried out from September to October 2016, with a total duration of 30 days. A complete random design was used. The treatments consisted of four sorghum cultivars, each one inoculated independently with five bacterial isolates, with a total of nine replicates per treatment. A non-inoculated treatment under phosphate starvation conditions was established as a control. Seeds were disinfected as described by Liu et al. (2013). Briefly, seeds were soaked in 70% ethanol for 3 min, transferred to a new tube containing 2.5% sodium hypochlorite solution, and shaken for 5 min. The seeds were then washed with 70% ethanol solution for 30 s. Finally, the seeds were rinsed with sterile water four times. After the last washing step, 20 μl of the remaining water was plated on Petri dishes with Luria-Bertani (LB) medium to confirm the success of disinfection. After disinfection, the seeds were placed in Petri dishes containing 1% water agar medium, and the plates were incubated at 25 °C for 2 days in the dark for seed germination. The experiment is illustrated in Fig. 1. When radicle emerged from the seed coat, the seedlings were transplanted from the Petri dishes to 11 × 11 × 12 cm plastic pots filled with autoclaved silver sand as substrate. The pots containing one plant each were maintained under greenhouse conditions for 4 weeks. During the first week, the pots were watered with 1/2 Hoagland 10% P nutrient solution, followed by P starvation. To create P starvation conditions, the substrate with plants was first flushed with 500 mL of 1/2-strength Hoagland nutrient solution without phosphate to remove any remaining phosphate in the substrate by drainage through the pot. After 2 days, to simulate field conditions, two g (125 μM) of insoluble tricalcium phosphate (Ca3(PO4)2), which can be solubilized by microorganisms but not taken up directly by the plant (Estrada et al., 2013), was diluted in Hoagland nutrient solution and applied to the pots. The watering regime was maintained by applying 25 ml of nutrient solution every 2 days.

Figure 1. Illustration of the different steps of the study (photos: T. Schlemper and F. Silva Gutierrez).

Bacterial inoculation

Bacterial isolates were taken from single colonies grown in Petri dishes containing LB medium at 30 °C for 2–3 days and stored at 4 °C. Bacterial cells of each strain were then grown overnight at 31 °C in LB liquid medium and subsequently inoculated again in a fresh LB medium until reaching the desired inoculum density (108 cfu ml−1) (Mishra et al., 2016). After transplanting, and during plant growth, bacterial isolates were applied three times on the top of the sandy substrate directly at the location of the seedling roots. The control treatment was inoculation with LB medium without bacteria. The first inoculation was performed on the third day after transplanting, the second on the second day after P starvation, and the last 1 week later. The inoculation was performed three times to ensure a sufficient bacterial cell density surrounding the plant roots. Loss or dilution of the bacterial inoculum during either the P starvation treatment or the watering regime was possible due to the great drainage potential of the sandy substrate. A density of 108 cfu ml−1 in a volume of 1 ml was used for each bacterial strain at each inoculation time.

Harvesting

After 4 weeks of transplanting, the experimental plants were harvested, and six plants per treatment were taken for biomass and root architecture measurements. The plants were carefully collected from the pots and the root system was rinsed with tap water to remove sand particles. The plants were then divided into shoot and root parts for root architecture and plant dry biomass measurements.

Root architecture

For root architecture measurements, the roots were sectioned in three parts, spread along a rectangular acrylic tray and placed in an EPSON scanner Ver. 3.9.3 1NL. The measured root architecture parameters were the specific root area (SRA), specific root length (SRL), AvD, and specific root density (SRD). All parameters were analyzed in WINRHIZO™ program V2005b. Specific root area was calculated by dividing the surface area by the root dry biomass. Specific root length was calculated by the following formula:

Plant biomass

The shoot and root parts were dried at room temperature for 4 h, until no remaining water could be observed on their surfaces. The fresh weights of both parts were obtained using an electronic scale. The shoot and root parts were then placed in an oven at 60 °C for 72 h. The percentage of biomass was calculated by dividing the dry weight biomass by the fresh weight and multiplying by 100.

Statistical analysis

The plant dry biomass and root architecture data were analysed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Duncan’s test (P < 0.05) using the IBM SPSS Statistics 23 program.

Results

Bacterial strains and PGPB effect on sorghum plant biomass

The five bacterial strains exhibited different characteristics in terms of specific plant growth-promotion traits (Table 1). Strain IAC/BECa 128 (E. asburiae) had the capability to solubilize phosphate. All strains produced IAA, except strain IAC/BECa 135 (Burkholderia tropica). Strains IAC/BECa 99 (K. radicincitans), IAC/BECa 128 (E. asburiae) and IAC/BECa 152 (H. frisingense) produced siderophores. Strain IAC/BECa 141 (P. fluorescens) produced hydrogen cyanide and strain IAC/BECa 99 (K. radicincitans) exhibited amplification of nifH gene. All strains were antagonistic to the growth of the pathogens Fusarium verticillioides and C. paradoxa; however, only strain IAC/BECa 141 (P. fluorescens) was antagonistic to the pathogen Bipolaris sacchari.

Table 1. Plant growth promotion characteristics of five bacterial strains.

| PGPR trait | Strain | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IAC/BECa 99 | IAC/BECa 128 | IAC/BECa 135 | IAC/BECa 141 | IAC/BECa 152 | |

| P solubilization | − | + | − | − | − |

| IAA | + | + | − | + | + |

| Siderophore | + | + | − | − | + |

| Hydrogen cyanide | − | − | − | + | − |

| nifH gene | + | − | − | − | − |

| Antagonism to: | |||||

| Bipolaris Sacchari | − | − | − | + | + |

| Fusarium verticillioides | + | + | + | + | + |

| Ceratocystis paradoxa | + | + | + | + | + |

Notes:

Plant growth promotion characteristics of five bacterial strains IAC/BECa 99 (Kosakonia radicincitans), IAC/BECa 128 (Enterobacter asburiae), IAC/BECa 135 (Burkholderia tropica), IAC/BECa 141 (Pseudomonas fluorescens), and IAC/BECa 152 (Herbaspirillum frisingense).

Positive (+) and negative (−) signals mean positive and negative result for each plant growth promotion traits listed.

Sorghum cultivar SRN39 exhibited a significant increase in root dry biomass when inoculated with Burkholderia tropica strain IAC/BECa 135 or H. frisingense strain IAC/BECa 152, and a significantly higher shoot biomass when inoculated with E. asburiae strain IAC/BECa 128 or H. frisingense strain IAC/BECa 152, compared with the control (Table 2). Cultivar BRS330 displayed a significant increase in root dry biomass when inoculated with strain IAC/BECa 135 (Burkholderia tropica) or IAC/BECa 152 (H. frisingense) compared with the control. However, when inoculated with E. asburiae strain IAC/BECa 128, this cultivar exhibited a significant decrease in shoot biomass compared with the non-inoculated control. Cultivars SQR and BRS509 did not exhibit any significant differences in biomass when inoculated with any of the strains compared to the control (Table 2).

Table 2. Root and shoot biomass (%) of four cultivars of sorghum (SRN-39, SQR, BRS330 and BRS509) inoculated with five bacterial isolates.

| Cultivars | Bacterial isolate | Root biomass (%) | Shoot biomass (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SRN-39 | Control | 18.10 ± 1.19c | 22.20 ± 0.73c |

| IAC/BECa 99 | 21.52 ± 0.75b,c | 23.66 ± 0.50b,c | |

| IAC/BECa 128 | 24.83 ± 3.03a,b,c | 25.22 ± 0.98b | |

| IAC/BECa 135 | 27.48 ± 3.20a,b | 23.82 ± 0.37b,c | |

| IAC/BECa 141 | 21.46 ± 2.06b,c | 23.94 ± 0.68b,c | |

| IAC/BECa 152 | 31.47 ± 1.74a | 28.51 ± 1.34a | |

| SQR | Control | 29.52 ± 2.84a | 22.21 ± 0.88a |

| IAC/BECa 99 | 24.50 ± 2.25a | 19.62 ± 1.15a | |

| IAC/BECa 128 | 25.67 ± 1.90a | 19.56 ± 0.97a | |

| IAC/BECa 135 | 31.15 ± 3.24a | 19.69 ± 0.64a | |

| IAC/BECa 141 | 29.26 ± 3.56a | 20.31 ± 0.87a | |

| IAC/BECa 152 | 33.64 ± 1.59a | 20.94 ± 0.37a | |

| BRS330 | Control | 13.19 ± 0.69b,c | 20.75 ± 0.35a |

| IAC/BECa 99 | 12.58 ± 0.48b,c | 19.92 ± 0.54ab | |

| IAC/BECa 128 | 11.77 ± 0.69c | 19.82 ± 0.32b | |

| IAC/BECa 135 | 19.17 ± 2.30a | 21.24 ± 0.33a | |

| IAC/BECa 141 | 16.14 ± 1.02a,b | 19.91 ± 0.48a,b | |

| IAC/BECa 152 | 18.43 ± 0.98a | 20.50 ± 0.30a,b | |

| BRS509 | Control | 24.13 ± 2.00a,b | 25.38 ± 1.46a |

| IAC/BECa 99 | 20.79 ± 2.60b | 23.56 ± 0.23a | |

| IAC/BECa 128 | 24.57 ± 0.88a,b | 22.73 ± 0.65a | |

| IAC/BECa 135 | 28.29 ± 2.38a | 22.48 ± 0.44a | |

| IAC/BECa 141 | 20.68 ± 1.62b | 22.97 ± 0.48a | |

| IAC/BECa 152 | 24.04 ± 1.70a,b | 23.44 ± 1.50a |

Notes:

Root and shoot biomass (%) of four cultivars of sorghum (SRN-39, SQR, BRS330 and BRS509) inoculated with five bacterial isolates IAC/BECa 99 (Kosakonia radicincitans), IAC/BECa 128 (Enterobacter asburiae), IAC/BECa 135 (Burkholderia tropica), IAC/BECa 141 (Pseudomonas fluorescens), and IAC/BECa 152 (Herbaspirillum frisingense).

The values are means of replicates (n = 6) ± (SE). For each parameter, letters compare (on column) the means between the bacterial inoculums treatments within the same cultivar. Means followed by the same letter are not statistically different by Duncan test (P < 0.05).

PGPB effects on root architecture

Cultivars SRN39, SQR, and BRS509 did not display significant differences in root architecture parameters when inoculated with any strain compared with the control. However, cultivar BRS330 inoculated with E. asburiae strain IAC/BECa 128 exhibited a significantly higher SRA and SRL compared with the control. Furthermore, when inoculated with Burkholderia tropica strain IAC/BECa 135 or H. frisingense strain IAC/BECa 152, the same cultivar exhibited a significant decrease in AvD compared with the control (Table 3). Cultivar BRS 330 inoculated with Burkholderia tropica (IAC/BECa 135), P. fluorescens (IAC/BECa 141) or H. frisingense (IAC/BECa 152) had a higher SRD compared than the treatment inoculated with E. asburiae (IAC/BECa 128) but not the control.

Table 3. Specific root area, specific root length, average of root diameter, and specific root density of our cultivars of sorghum.

| Cultivars | Isolates | SRA (cm2/g) | SRL (cm/g) | AvD (mm) | RDENS (cm3/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRN-39 | Control | 847.29 ± 44.46a | 687.39 ± 66.85a | 0.40 ± 0.02a | 0.12 ± 0.00a |

| IAC/BECa 99 | 1027.44 ± 130.77a | 867.21 ± 151.8a | 0.39 ± 0.02a | 0.11 ± 0.01a | |

| IAC/BECa 128 | 1061.95 ± 146.42a | 881.21 ± 66.73a | 0.38 ± 0.03a | 0.11 ± 0.02a | |

| IAC/BECa 135 | 1016.59 ± 59.11a | 882.89 ± 91.54a | 0.38 ± 0.02a | 0.11 ± 0.01a | |

| IAC/BECa 141 | 1044.78 ± 68.45a | 883.43 ± 67.29a | 0.38 ± 0.02a | 0.10 ± 0.01a | |

| IAC/BECa 152 | 914.74 ± 50.78a | 802.62 ± 69.77a | 0.37 ± 0.01a | 0.12 ± 0.00a | |

| SQR | Control | 1021.64 ± 41.81a | 909.61 ± 69.28a | 0.36 ± 0.01a | 0.11 ± 0.00a,b |

| IAC/BECa 99 | 1034.82 ± 58.91a | 922.61 ± 62.72a | 0.36 ± 0.01a | 0.11 ± 0.01a,b | |

| IAC/BECa 128 | 1217.28 ± 204.39a | 1220.4 ± 310.4a | 0.35 ± 0.02a | 0.10 ± 0.01a,b | |

| IAC/BECa 135 | 1239.66 ± 109.67a | 1056.5 ±116.53a | 0.38 ± 0.02a | 0.09 ± 0.01b | |

| IAC/BECa 141 | 1284.28 ± 207.40a | 1214.2 ± 211.88a | 0.34 ± 0.01a | 0.10 ± 0.01b | |

| IAC/BECa 152 | 917.84 ± 26.31a | 894.24 ± 32.09a | 0.33 ± 0.01a | 0.13 ± 0.00a | |

| BRS330 | Control | 881.00 ± 28.55b | 609.24 ± 23.55b | 0.46 ± 0.01a | 0.10 ± 0.00a,b |

| IAC/BECa 99 | 926.69 ± 66.26a,b | 677.58 ± 47.12a,b | 0.43 ± 0.01a,b | 0.10 ± 0.01a,b | |

| IAC/BECa 128 | 1101.94 ± 96.50a | 774.88 ± 72.32a | 0.46 ± 0.01a | 0.08 ± 0.01b | |

| IAC/BECa 135 | 841.07 ± 80.40b | 645.94 ± 60.04a,b | 0.41 ± 0.01b | 0.12 ± 0.01a | |

| IAC/BECa 141 | 767.82 ± 44.72b | 561.31 ± 32.04b | 0.44 ± 0.01a,b | 0.12 ± 0.01a | |

| IAC/BECa 152 | 786.94 ± 14.98b | 605.28 ± 18.08b | 0.42 ± 0.01b | 0.12 ± 0.00a | |

| BRS509 | Control | 1337.8 ± 665.09a | 1121.9 ± 531.2a | 0.38 ± 0.03a,b | 0.17 ± 0.04a |

| IAC/BECa 99 | 707.81 ± 68.59a | 553.35 ± 62.87a | 0.41 ± 0.01a | 0.14 ± 0.01a | |

| IAC/BECa 128 | 633.89 ± 45.40a | 524.96 ± 35.46a | 0.38 ± 0.01a,b | 0.17 ± 0.01a | |

| IAC/BECa 135 | 779.74 ± 53.88a | 662.51 ± 50.39a | 0.38 ± 0.01a,b | 0.14 ± 0.01a | |

| IAC/BECa 141 | 1130.4 ± 230.66a | 1138 ± 325.22a | 0.34 ± 0.02b | 0.12 ± 0.01a | |

| IAC/BECa 152 | 703.37 ± 79.40a | 622.32 ± 74.82a | 0.36 ± 0.01a,b | 0.17 ± 0.02a |

Notes:

Specific root area (SRA), specific root length (SRL), average of root diameter (AvD), and specific root density (RDENS) four cultivars of sorghum (SRN-39, SQR, BRS330 and BRS509) inoculated with five bacterial isolates (IAC/BECa 99 (Kosakonia radicincitans), IAC/BECa 128 (Enterobacter asburiae), IAC/BECa 135 (Burkholderia tropica), IAC/BECa 141 (Pseudomonas fluorescens), and IAC/BECa 152 (Herbaspirillum frisingense).

Values are means of replicates (n = 6) ± (SE). For each parameter, letters compare (on column) the means between the bacterial inoculum treatments within the same cultivar. Means followed by the same letter are not statistically different by Duncan test (P < 0.05).

Discussion

This work aimed to evaluate the effect of five bacterial strains isolated from sugarcane on the plant growth and root architecture of four sorghum cultivars. Cultivars SRN-39 and BRS330 inoculated with Burkholderia tropica strain IAC/BECa 135 or H. frisingense strain IAC/BECa 152 and cultivar SRN-39 inoculated with E. asburiae strain IAC/BECa 128 or H. frisingense strain IAC/BECa 152 exhibited significant increases in sorghum root and shoot biomass, respectively, compared with the control. Although the number of replicates in our study was small (6) our results corroborate those of Chiarini et al. (1998), who found that isolates belonging to the genera Burkholderia and Enterobacter co-inoculated in the sorghum rhizosphere promoted a significant increase in root growth compared to non-inoculated plants. Furthermore, species belonging to the genera Burkholderia and Herbaspirillum promote the growth of sugarcane and maize (Pereira et al., 2014; Da Silva et al., 2016), which, like sorghum, are C4 grass species. H. frisingense strain IAC/BECa 152 produces siderophores and IAA, whereas Burkholderia tropica strain IAC/BECa 135 does not. The strain IAC/BECa 152 might possess a set of mechanisms that improve plant nutrient uptake either by increasing nutrient availability in the rhizosphere or influencing the biochemical mechanisms underlying nutritional processes (Pii et al., 2015). Such mechanisms include changes in the root system architecture and shoot-to-root biomass ratio, increases in proton efflux by modulating H+ATPase activities, indirect effects of IAA produced by PGPB, or acidification of the rhizosphere to enhance nutrient solubility (Pii et al., 2015). In addition to growth regulators, siderophores can be produced and are known to assist Fe acquisition by roots (Saravanan, Madhaiyan & Thangaraju, 2007; Mehnaz et al., 2013).

In contrast to the effects of Burkholderia tropica, H. frisingense and E. asburiae on the growth of both grain sorghum cultivars, these strains had no significant effect on BRS 509 (sweet sorghum) and on SQR cultivars compared with the control. Interestingly, in accordance with our results, Dos Santos et al. (2017) observed significant increase in the biomass of grass and grain sorghum inoculated with Burkholderia ssp. or Herbaspirillum ssp. but not sweet sorghum inoculated with the same isolates. Taken together with our results, these findings suggest that the effects of strains of Burkholderia tropica and H. frisingense on plant growth are dependent on sorghum genotype. It is unclear why the effects of these strains were greater in certain sorghum cultivars than others. However, different sorghum genotypes release different SL molecules in different quantities under P starvation (Schlemper et al., 2017). Thus, the high relative abundance of the genus Burkholderia in the rhizosphere of sorghum cultivar SRN-39 could be related to the level of orobanchol, which is 300 and 1,100 times higher in SRN-39 than in the cultivars SQR, BRS330 and BRS509 as suggested by Schlemper et al. (2017).

When inoculated with E. asburiae strain IAC/BECa 128, cultivar BRS330 displayed an increase in SRL and area compared with the control. These finding are in agreement with a study by Kryuchkova et al. (2014), who reported that Enterobacter species can promote increased root length and lateral roots in sunflower. The strain IAC/BECa 128 can solubilize phosphate, which trait might explain the increase in root biomass. The cultivar BRS330 inoculated with strain IAC/BECa 135 (Burkholderia tropica) or IAC/BECa 152 (H. frisingense) exhibited a significant decrease in average root diameter compared with the control but slight increase in root density. Plants under P deficiency conditions may increase root density probably to enhance nutrient acquisition (Kapulnik & Koltai, 2014). Moreover, species belonging to the genus Herbaspirillum can influence plant root architecture and improve signaling pathways of plant hormone production (Straub et al., 2013). No significant effects on sorghum growth or root architecture modification were observed when K. radicincitans strain IAC/BECa-99 or P. fluorescens strain IAC/BECa-141 was inoculated in the rhizosphere of any evaluated sorghum cultivar. Although there are many reports on the effects of K. radicincitans (formerly known as E. radicincitans) on a range of plants, such as Arabidopsis thaliana, radish, and tomato (Berger, Brock & Ruppel, 2013; Brock et al., 2013; Berger et al., 2015), there are no reports on the effects of this bacterial species on sorghum growth or root architecture modification. With respect to P. fluorescens, Marcos et al. (2016) found that the strain IAC/BECa 141, when used as an inoculant applied to two sugarcane varieties, increased chlorophyll a content without changing plant growth. Kumar et al. (2012) studying the effect of seven different fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. strains with single or multiple PGPR traits, in sorghum growth, observed that all strains were able to increase sorghum growth compared to a non-inoculated control. Our results demonstrated that selected bacterial strains characterized as PGPB in sugarcane were able to promote plant growth and root architecture modification in sorghum. Based on the reproducibility of the performance of bacterial strains for different crops, our findings shed light on the identification of bacterial candidate strains for improving the growth and yield of crops that share the same soil bacterial source in intercropping or crop rotation systems. However, since we did not evaluate the bacterial community that actually colonized the root system, it is difficult to confirm that the differences we observed in sorghum biomass were due to the effects of the inoculation or a side effect of the plant due to the simple presence of these bacterial cells in the rhizosphere. Hence, we strongly recommend future studies to recover the bacterial community from the endosphere and rhizosphere compartments as proof of inoculation. We suggest that SL plays a role in the effectiveness of PGPB in promoting the growth of specific sorghum genotypes, although our experimental set-up did not allow us to make a straightforward conclusion. More specific experiments are needed to better address the relationship between plant SL production and plant bacterial infection.

Conclusion

Here, we demonstrated that bacteria strains characterized as PGPB in sugarcane were able to promote plant growth and root architecture modification in sorghum. Our results demonstrated that cultivars SRN-39 and BRS330 inoculated with Burkholderia tropica strain IAC/BECa 135 or H. frisingense frisingense strain IAC/BECa 152 exhibited a significant increase in plant biomass. Moreover, cultivar BRS330 inoculated with either strain displayed a significant decrease in AvD. The results of this study indicate that Burkholderia tropica strain IAC/BECa 135 and H. frisingense strain IAC/BECa 152 are promising PGPB strains for use as inocula for sustainable sorghum cultivation.

Supplemental Information

Sheet 1: Plant biomass raw data.

Sheet 2: Root architecture raw data.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dr. Francisco de Souza and Prof. Harro Bouwmeester for providing sorghum seeds. Publication number 6558 of the NIOO-KNAW, Netherlands Institute of Ecology.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Brazilian Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES: 1549-13-8), The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, FAPESP and CNPq (NWO-FAPESP 729.004.003; NWO-CNPq 729.004.013-456420/2013-4). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Adriana P.D. Silveira, Email: apdsil@iac.sp.gov.br.

Eiko E. Kuramae, Email: E.Kuramae@nioo.knaw.nl.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Thiago R. Schlemper conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Mauricio R. Dimitrov conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Federico A.O. Silva Gutierrez performed the experiments, approved the final draft.

Johannes A. van Veen contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Adriana P.D. Silveira analyzed the data, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft, the bacterial strains.

Eiko E. Kuramae conceived and designed the experiments, analyzed the data, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft.

Data Availability

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The raw data are provided in the Supplemental File.

References

- Amara, Khalid & Hayat (2015).Amara U, Khalid R, Hayat R. Soil bacteria and phytohormones for sustainable crop production. In: Maheshwari DK, editor. Bacterial Metabolites in Sustainable Agroecosystem. Springer Cham; 2015. pp. 87–103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker & Schippers (1987).Bakker AW, Schippers B. Microbial cyanide production in the rhizosphere in relation to potato yield reduction and Pseudomonas spp-mediated plant growth-stimulation. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 1987;19:451–457. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Brock & Ruppel (2013).Berger B, Brock AK, Ruppel S. Nitrogen supply influences plant growth and transcriptional responses induced by Enterobacter radicincitans in Solanum lycopersicum. Plant and Soil. 2013;370(1–2):641–652. doi: 10.1007/s11104-013-1633-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berger et al. (2015).Berger B, Wiesner M, Brock AK, Schreiner M, Ruppel S. K. radicincitans, a beneficial bacteria that promotes radish growth under field conditions. Agronomy for Sustainable Development. 2015;35(4):1521–1528. doi: 10.1007/s13593-015-0324-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya & Jha (2012).Bhattacharyya P, Jha D. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR): emergence in agriculture. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2012;28(4):1327–1350. doi: 10.1007/s11274-011-0979-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bric, Bostock & Silverstone (1991).Bric JM, Bostock RM, Silverstone SE. Rapid in situ assay for indoleacetic acid production by bacteria immobilized on a nitrocellulose membrane. Applied and environmental Microbiology. 1991;57:535–538. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.2.535-538.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock et al. (2013).Brock AK, Berger B, Mewis I, Ruppel S. Impact of the PGPB Enterobacter radicincitans DSM 16656 on growth, glucosinolate profile, and immune responses of Arabidopsis thaliana. Microbial Ecology. 2013;65(3):661–670. doi: 10.1007/s00248-012-0146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiarini et al. (1998).Chiarini L, Bevivino A, Tabacchioni S, Dalmastri C. Inoculation of Burkholderia cepacia, Pseudomonas fluorescens and Enterobacter sp. on Sorghum bicolor: root colonization and plant growth promotion of dual strain inocula. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 1998;30(1):81–87. doi: 10.1016/s0038-0717(97)00096-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Damasceno, Schaffert & Dweikat (2014).Damasceno CM, Schaffert RE, Dweikat I. Mining genetic diversity of sorghum as a bioenergy feedstock. In: Maureen M, Marcos B, Nick C, editors. Plants and BioEnergy. Springer; 2014. pp. 81–106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva et al. (2016).Da Silva PRA, Vidal MS, De Paula Soares C, Polese V, Simões-Araújo JL, Baldani JI. Selection and evaluation of reference genes for RT-qPCR expression studies on Burkholderia tropica strain Ppe8, a sugarcane-associated diazotrophic bacterium grown with different carbon sources or sugarcane juice. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 2016;109(11):1493–1502. doi: 10.1007/s10482-016-0751-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Silveira et al. (2016).Da Silveira APD, Sala VMR, Cardoso EJBN, Labanca EG, Cipriano MAP. Nitrogen metabolism and growth of wheat plant under diazotrophic endophytic bacteria inoculation. Applied Soil Ecology. 2016;107:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2016.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dawwam et al. (2013).Dawwam G, Elbeltagy A, Emara H, Abbas I, Hassan M. Beneficial effect of plant growth promoting bacteria isolated from the roots of potato plant. Annals of Agricultural Sciences. 2013;58(2):195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.aoas.2013.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos et al. (2017).Dos Santos CLR, Alves GC, De Matos Macedo AV, Giori FG, Pereira W, Urquiaga S, Reis VM. Contribution of a mixed inoculant containing strains of Burkholderia spp. and Herbaspirillum ssp. to the growth of three sorghum genotypes under increased nitrogen fertilization levels. Applied Soil Ecology. 2017;113:96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2017.02.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dutra et al. (2013).Dutra ED, Barbosa Neto AG, De Souza RB, De Morais Junior MA, Tabosa JN, Cezar Menezes RS. Ethanol production from the stem juice of different sweet sorghum cultivars in the state of Pernambuco, Northeast of Brazil. Sugar Tech. 2013;15(3):316–321. doi: 10.1007/s12355-013-0240-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada et al. (2013).Estrada GA, Baldani VLD, De Oliveira DM, Urquiaga S, Baldani JI. Selection of phosphate-solubilizing diazotrophic Herbaspirillum and Burkholderia strains and their effect on rice crop yield and nutrient uptake. Plant and Soil. 2013;369(1–2):115–129. doi: 10.1007/s11104-012-1550-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- FAO (2008).Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) Faostat–Annual sorghum production. 2008. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC. [28 July 2018]. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC

- Farre & Faci (2006).Farre I, Faci JM. Comparative response of maize (Zea mays L.) and sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L. Moench) to deficit irrigation in a Mediterranean environment. Agricultural Water Management. 2006;83(1–2):135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.agwat.2005.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Funnell-Harris, Pedersen & Marx (2008).Funnell-Harris DL, Pedersen JF, Marx DB. Effect of sorghum seedlings, and previous crop, on soil fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. Plant and Soil. 2008;311:173–187. [Google Scholar]

- Funnell-Harris, Sattler & Pedersen (2013).Funnell-Harris DL, Sattler SE, Pedersen JF. Characterization of fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. associated with roots and soil of two sorghum genotypes. European Journal of Plant Pathology. 2013;136(3):469–481. doi: 10.1007/s10658-013-0179-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glick (2012).Glick BR. Plant growth-promoting bacteria: mechanisms and applications. Scientifica. 2012;2012:1–15. doi: 10.6064/2012/963401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindarajan et al. (2006).Govindarajan M, Balandreau J, Muthukumarasamy R, Revathi G, Lakshminarasimhan C. Improved yield of micropropagated sugarcane following inoculation by endophytic Burkholderia vietnamiensis. Plant Soil. 2006;280(1–2):239–252. doi: 10.1007/s11104-005-3223-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haichar et al. (2014).Haichar FEZ, Santaella C, Heulin T, Achouak W. Root exudates mediated interactions belowground. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2014;77:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.06.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haiyambo, Reinhold-Hurek & Chimwamurombe (2015).Haiyambo DH, Reinhold-Hurek B, Chimwamurombe PM. Effects of plant growth promoting bacterial isolates from Kavango on the vegetative growth of Sorghum bicolor. African Journal of Microbiology Research. 2015;9(10):725–729. doi: 10.5897/ajmr2014.7205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kapulnik & Koltai (2014).Kapulnik Y, Koltai H. Strigolactone involvement in root development, response to abiotic stress, and interactions with the biotic soil environment. Plant Physiology. 2014;166(2):560–569. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.244939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katznelson & Bose (1959).Katznelson H, Bose B. Metabolic activity and phosphate-dissolving capability of bacterial isolates from wheat roots, rhizosphere, and non-rhizosphere soil. Canadian Journal of Microbiology. 1959;5:79–85. doi: 10.1139/m59-010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kryuchkova et al. (2014).Kryuchkova YV, Burygin GL, Gogoleva NE, Gogolev YV, Chernyshova MP, Makarov OE, Fedorov EE, Turkovskaya OV. Isolation and characterization of a glyphosate-degrading rhizosphere strain, Enterobacter cloacae K7. Microbiological Research. 2014;169(1):99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar et al. (2012).Kumar GP, Kishore N, Amalraj ELD, Ahmed S, Rasul A, Desai S. Evaluation of fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. with single and multiple PGPR traits for plant growth promotion of sorghum in combination with AM fungi. Plant Growth Regulation. 2012;67(2):133–140. doi: 10.1007/s10725-012-9670-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu et al. (2013).Liu F, Xing S, Ma H, Du Z, Ma B. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria affect the growth and nutrient uptake of Fraxinus americana container seedlings. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2013;97(10):4617–4625. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4255-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucy, Reed & Glick (2004).Lucy M, Reed E, Glick BR. Applications of free living plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 2004;86(1):1–25. doi: 10.1023/b:anto.0000024903.10757.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcos et al. (2016).Marcos FCC, Iório RDPF, Silveira APDD, Ribeiro RV, Machado EC, Lagôa AMMDA. Endophytic bacteria affect sugarcane physiology without changing plant growth. Bragantia. 2016;75(1):1–9. doi: 10.1590/1678-4499.256. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matiru & Dakora (2004).Matiru VN, Dakora FD. Potential use of rhizobial bacteria as promoters of plant growth for increased yield in landraces of African cereal crops. African Journal of Biotechnology. 2004;3(1):1–7. doi: 10.5897/ajb2004.000-2002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- May et al. (2013).May A, Mendes S, Silva D, Parrella R, Miranda R, Silva A, Pacheco T, Aquino L, Cota L, Costa R. Cultivo de sorgo sacarino em áreas de reforma de canaviais. Sete Lagoas: Embrapa Milho e Sorgo; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mehnaz et al. (2013).Mehnaz S, Saleem RSZ, Yameen B, Pianet I, Schnakenburg G, Pietraszkiewicz H, Valeriote F, Josten M, Sahl H-G, Franzblau SG. Lahorenoic acids A–C, ortho-dialkyl-substituted aromatic acids from the biocontrol strain Pseudomonas aurantiaca PB-St2. Journal of Natural Products. 2013;76:135–141. doi: 10.1021/np3005166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra et al. (2016).Mishra V, Gupta A, Kaur P, Singh S, Singh N, Gehlot P, Singh J. Synergistic effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and plant growth promoting rhizobacteria in bioremediation of iron contaminated soils. International Journal of Phytoremediation. 2016;18(7):697–703. doi: 10.1080/15226514.2015.1131231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peláez-Vico et al. (2016).Peláez-Vico MA, Bernabéu-Roda L, Kohlen W, Soto MJ, López-Ráez JA. Strigolactones in the Rhizobium-legume symbiosis: stimulatory effect on bacterial surface motility and down-regulation of their levels in nodulated plants. Plant Science. 2016;245:119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perazzo et al. (2013).Perazzo AF, Santos EM, Pinho RMA, Campos FS, Ramos JPD, De Aquino MM, Da Silva TC, Bezerra HFC. Agronomic characteristics and rain use efficiency of sorghum genotypes in semiarid. Ciencia Rural. 2013;43(10):1771–1776. doi: 10.1590/S0103-84782013001000007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira et al. (2014).Pereira TP, Do Amaral FP, Dall’Asta P, Brod FC, Arisi AC. Real-time PCR quantification of the plant growth promoting bacteria Herbaspirillum seropedicae strain SmR1 in maize roots. Molecular Biotechnology. 2014;56(7):660–670. doi: 10.1007/s12033-014-9742-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pii et al. (2015).Pii Y, Mimmo T, Tomasi T, Terzano R, Cesco S, Crecchio C. Microbial interactions in the rhizosphere: beneficial influences of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria on nutriente acquisition process. A review. Biology and Fertility of Soils. 2015;51(4):403–415. doi: 10.1007/s00374-015-0996-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raaijmakers & Weller (2001).Raaijmakers JM, Weller DM. Exploiting genotypic diversity of 2,4-Diacetylphloroglucinol-producing Pseudomonas spp.: characterization of superior root-colonizing P. fluorescens strain Q8r1-96. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2001;67(6):2545–2554. doi: 10.1128/aem.67.6.2545-2554.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramu et al. (2013).Ramu P, Billot C, Rami JF, Senthilvel S, Upadhyaya HD, Reddy LA, Hash CT. Assessment of genetic diversity in the sorghum reference set using EST-SSR markers. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2013;126(8):2051–2064. doi: 10.1007/s00122-013-2117-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao et al. (2014).Rao S, Reddy BV, Nagaraj N, Upadhyaya HD. Sorghum production for diversified uses. In: Wang YH, Upadhyaya HD, Kole C, editors. Genetics, Genomics and Breeding of Sorghum. CRC Press; 2014. pp. 1–27.978-1-4822-1008-8 [Google Scholar]

- Saravanan, Madhaiyan & Thangaraju (2007).Saravanan V, Madhaiyan M, Thangaraju M. Solubilization of zinc compounds by the diazotrophic, plant growth promoting bacterium Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus. Chemosphere. 2007;66:1794–1798. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.07.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlemper et al. (2017).Schlemper TR, Leite MF, Lucheta AR, Shimels M, Bouwmeester HJ, Van Veen JA, Kuramae EE. Rhizobacterial community structure differences among sorghum cultivars in different growth stages and soils. FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 2017;93(8):1–11. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fix096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwyn & Neilands (1987).Schwyn B, Neilands J. Universal chemical assay for the detection and determination of siderophores. Analytical Biochemistry. 1987;160:47–56. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90612-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevilla et al. (2001).Sevilla M, Burris RH, Gunapala N, Kennedy C. Comparison of benefit to sugarcane plant growth and 15N2 incorporation following inoculation of sterile plants with Acetobacter diazotrophicus wild-type and Nif− mutant strains. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2001;14(3):358–366. doi: 10.1094/mpmi.2001.14.3.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub et al. (2013).Straub D, Yang H, Liu Y, Tsap T, Ludewig U. Root ethylene signalling is involved in Miscanthus sinensis growth promotion by the bacterial endophyte Herbaspirillum frisingense GSF30(T) Journal of Experimental Botany. 2013;64(14):4603–4615. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vurukonda et al. (2016).Vurukonda SSKP, Vardharajula S, Shrivastava M, SkZ A. Enhancement of drought stress tolerance in crops by plant growth promoting rhizobacteria. Microbiological Research. 2016;184:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu et al. (2010).Wu XR, Staggenborg S, Propheter JL, Rooney WL, Yu JM, Wang DH. Features of sweet sorghum juice and their performance in ethanol fermentation. Industrial Crops and Products. 2010;31(1):164–170. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2009.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sheet 1: Plant biomass raw data.

Sheet 2: Root architecture raw data.

Data Availability Statement

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The raw data are provided in the Supplemental File.