Abstract

Objective:

This study aims to examine whether, in a large implementation program of collaborative care in safety net primary care clinics, psychiatric case review is associated with depression medication modification.

Methods:

Registry data were examined from an implementation of the collaborative care model (CCM) in Washington State and included adults from 178 primary care clinics with baseline Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) scores ≥10 (n = 14,960). Psychiatric case reviews and depression medications were extracted from the registry. Rates of new depression medications and psychiatric case reviews were calculated for all patients and in the subset of patients not improving by 8 weeks of treatment (defined as not achieving a PHQ-9 score of <10 or a ≥50% reduction in PHQ-9 score compared with baseline).

Results:

Half of patients (n = 7,448; 49.8%) received a new depression medication during treatment. Psychiatric case review in any given month was associated with a doubling of the probability of receiving a new medication in the following month (20.1% vs. 10.9%, p<0.001). This remained true in patients not improving after 8 weeks in treatment (18.3% vs. 9.6%, p<0.001). Among patients not improving, a psychiatric case review during weeks 8 – 12 was associated with a higher rate of new medications during weeks 8 – 16 or weeks 8 – 20.

Conclusions:

In a collaborative care program, psychiatric case review is associated with higher rates of subsequent new depression medications. This supports the importance of psychiatric case review in reducing clinical inertia in collaborative care treatment of depression.

INTRODUCTION

Of the 7.6% of American adults who suffer from depression (1), only 9% receive adequate treatment (2). Among patients who receive treatment for depression, more than half receive treatment in primary care settings (3). In depression, as in many chronic conditions (4–8), clinical inertia is a major contributor to inadequate management (9,10). Clinical inertia is defined as a failure to initiate or intensify therapy despite a clear indication and recognition of the need to do so (11), and can be identified in contexts where there are recognized clinical goals or targets, a recommended therapy that can be measured, and a specified time window for appropriate initiation and intensification of treatment (12).

One mechanism to potentially address clinical inertia for depression in primary care may be through collaborative care management (CCM). CCM is an evidence-based integrated care model for the treatment of depression and other behavioral health disorders in primary care, in which there is closely monitored treatment to target through regular measurement and observation by care managers (13). There is a substantial evidence base for collaborative care, including more than 80 randomized control trials, suggesting that collaborative care is twice as effective as usual primary care treatment of patients with depression (14). For example, in the Improving Mood Promoting Access to Collaborative Care Treatment (IMPACT) trial, the largest trial of CCM, collaborative care was associated with higher rates of antidepressant use and psychotherapy treatment compared to treatment as usual (15). In addition, in a multi-site trial of CCM for depression and poorly controlled diabetes (16), CCM led to a six fold increase in antidepressant initiations and adjustments compared to treatment as usual (17). These initiations and adjustments occurred earlier in treatment among patients receiving CCM (compared to usual primary care management), suggesting a reduction in clinical inertia.

Reasons for reduced clinical inertia in collaborative care depression treatment might include closer monitoring of patients, increased primary care provider confidence in prescribing due to the use of standardized treatment algorithms, or through psychiatric case review for patients who are not improving with treatment. We have shown that among patients receiving collaborative care who have not responded to treatment after 8 weeks, psychiatric case review in the subsequent month strongly predicted improvement within 6 months (18), suggesting psychiatric case review may help overcome inertia and lead to changes in management that could explain improvement in depression outcomes in CCM.

Despite the above evidence, it is not clear whether the antidepressant medication treatment intensification observed in clinical trials of CCM interventions is feasible in real-world practice settings. Further, consulting psychiatrists in CCM models make recommendations for modifications in treatment plans, both behavioral treatment (i.e. different psychotherapeutic techniques or modalities) and pharmacotherapy. Regarding pharmacotherapy, they may recommend starting a new medication, escalating the dose of a current medication, switching medications, augmenting a medication, or stopping an inappropriate medication. There are multiple barriers to the implementation of these recommendations, each of which can decrease the likelihood of a change in treatment. In order to study how psychiatric case review affects the course of medication management in CCM for depression, we examined data from a large, state-wide CCM program implemented in almost 200 safety net primary care clinics, using new medications as an indicator for changes in treatment. We hypothesize that psychiatric case review in CCM is associated with a greater likelihood of subsequent change in depression medications.

METHODS

Participants and Setting

Our data are from the Washington State Mental Health Integration Program (MHIP), a publicly funded implementation of the CCM in a network of 178 community health clinics that are diverse in geographic location, size, and patient populations served. Established in 2008, the program serves patients with mental health and substance abuse conditions who receive primary care in participating clinics. Clinics use a Web-based registry (Mental Health Integrated Tracking System (MHITS)) to systematically follow care management activities and clinical outcomes. The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (19) was used to track depressive symptoms and assist in population management. The current analyses included patients who initiated care with MHIP between January 1, 2008 and September 30, 2014, were 18 years or older at the time of initial assessment, had clinically significant depression at the time of enrollment (PHQ-9 score ≥10), and had at least one follow-up contact with the care manager in the first 6 months of treatment. For patients with more than 1 episode of depression treatment during this time frame, only the initial episode was included. The Institutional Review Boards at the Weill Cornell Medical College and University of Washington approved this study, with a waiver of informed consent for individual patients.

Demographic and clinical characteristics.

Demographic information (age and gender), clinical characteristics (comorbid behavioral health diagnoses), and severity of depressive symptoms (based on PHQ-9 score) were obtained from MHITS. Behavioral health diagnoses (anxiety, PTSD, substance abuses, psychosis, and bipolar disorder) were as documented in MHITS by the care managers and were not confirmed by diagnostic testing.

Psychiatric case review

In the CCM model, psychiatric case review occurs through weekly meetings with the care manager. There were no documented cases where the psychiatric consultant saw patients in person. We derived dichotomous indicators of whether a given case/patient received at least one psychiatric consult or review based on documentation in MHITS. Analysis was conducted every 4 weeks for the first 6 months since initial assessment (or until patient exit from the program, defined by the date of the patient’s last contact with the care manager).

New depression medication

Current medications were recorded at initial assessment and follow-up contacts with the care manager. A comprehensive list of medications to treat depression (Appendix 1) was generated, and included all FDA-approved medications for depression or augmentation of depression, as well as mood stabilizers and antipsychotics. Given that we included all patients with a PHQ-9 score ≥ 10 regardless of psychiatric diagnoses, mood stabilizers and antipsychotics were included, as they may have been prescribed to target depressive symptoms in patients with bipolar disorder, psychotic disorder, or PTSD.

We operationalized our outcome of interest as having a new depression medication. This indicator encompasses several forms of medication management, including initiation of depression medication therapy, switching to a new medication, and augmenting current therapy with an additional medication. Unfortunately, dose adjustments of a current depression medication could not be evaluated because of limitations of the dataset. We developed an analytical algorithm to generate monthly indicators of whether a patient had a new antidepressant in a given month based on current and past medications documented in MHITS.

Statistical Analysis

We first conducted descriptive analysis to examine the rates of having at least one psychiatric case review over months 1 – 6 and of having a new depression medication over months 2 – 7. We started the series of new depression medications in month 2 because we wanted to capture new medications as a result of treatment adjustment. We then estimated a patient-month level linear probability model to test the hypothesis that psychiatric case review in the current month increases the probability that the patient starts a new depression medication in the following month. The model controlled for patient gender and age, PHQ-9 scores, and comorbid behavioral health conditions at initial assessment, months since initial assessment, months since the clinic started MHIP implementation (as a proxy for clinic experience with CCM), and dichotomous indicators of clinics to capture all time invariant, between-clinic differences contributing to the outcome. Robust standard errors were derived taking in to account clustering of months of the same patient.

We further conducted analysis at the patient level, but sub-setting to patients who did not achieve clinically significant improvement in depression by 8 weeks of treatment. Clinically significant improvement in depression was defined as having any follow-up PHQ-9 score of < 10, or achieving a ≥ 50% reduction in the PHQ-9 score from baseline. This subgroup of patients has a clear clinical indication for treatment intensification, and for whom the harm of clinical inertia is especially salient. We evaluated whether psychiatric case review during weeks 8 – 12 predicted a new depression medication in weeks 8 – 16 or 8 – 20. Restricting psychiatric case review to weeks 8 – 12 was based on the CCM protocol that recommends psychiatric case review for cases in which patients do not respond to initial treatment. A previous study found psychiatric case review during this time period was associated with higher rates of depression improvement (18). The observation window for new depression medications (8 – 16 and 8 – 20 weeks) were selected to accommodate the lag between psychiatric recommendation to start a new medication and actual initiation of that medication by the patient. We estimated a linear probability model for each analysis (psychiatric case review in weeks 8 – 12 predicting new depression medication in weeks 8 – 16 and 8 – 20), controlling for the same set of baseline patient characteristics and clinic fixed effects (described above).

RESULTS

The analyses included 14,960 adults in the WA state MHIP program with baseline PHQ-9 scores ≥10. Table 1 summarizes their demographic and clinical characteristics. Severe depressive symptoms, as indicated by a PHQ-9 score ≥ 20, were present in 42% of patients. The majority of patients also had comorbid anxiety (70.3%), while a substantial number of patients had comorbid PTSD (30.2%) or substance abuse (21.8%). The majority were on a depression medication at initial assessment (58.7%). Over the course of 24 weeks of treatment (or until last contact with care manager), 49.8% received a new depression medication.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients treated in a collaborative care model for depression.

| Characteristic | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic | ||

| Male | 6,815 | 45.6 |

| Female | 7,742 | 51.8 |

| Missing gender | 403 | 2.7 |

| Age | ||

| 18–29 | 3,127 | 20.9 |

| 30–39 | 3,268 | 21.8 |

| 40–49 | 4,381 | 29.3 |

| 50–59 | 3,413 | 22.8 |

| ≥60 | 771 | 5.2 |

| Baseline Patient Health Questionnaire-9 Score* | ||

| 10–14 | 3,840 | 25.7 |

| 15–19 | 4,838 | 32.3 |

| ≥20 | 6,282 | 42.0 |

| Documented comorbid behavioral health condition at baseline | ||

| Anxiety disorder | 10,522 | 70.3 |

| Bipolar disorder | 2,771 | 18.5 |

| Psychotic disorder | 635 | 4.2 |

| PTSD | 4,524 | 30.2 |

| Substance use disorder | 3,266 | 21.8 |

| On depression medication at baseline | 8,781 | 58.7 |

| Any depression medication from 0 to 24 weeks | 7,448 | 49.8 |

For PHQ-9, possible scores range from 0 – 27, with higher number indicating more severe depressive symptoms.

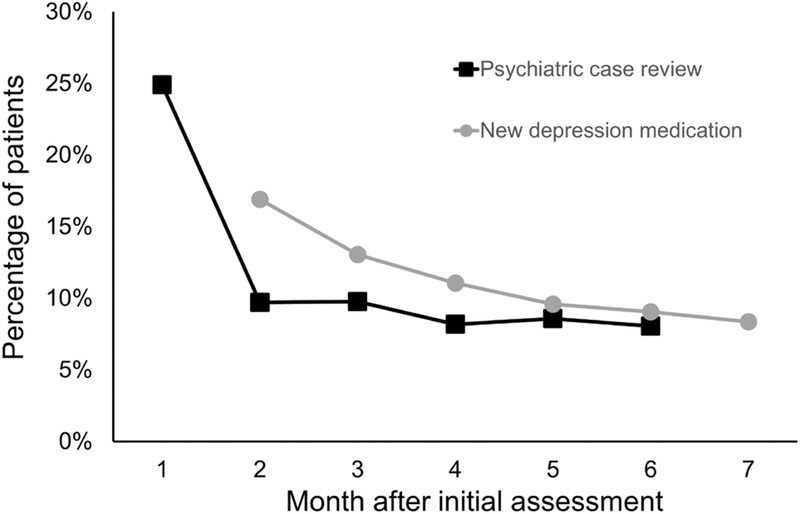

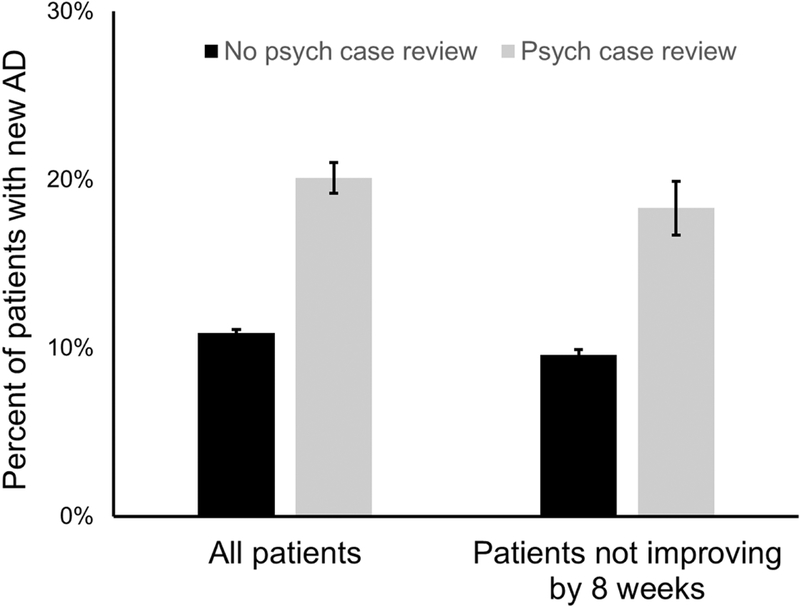

Figure 1 shows the rates of psychiatric case review and new depression medications over the course of 24 weeks of treatment. The highest monthly rate of psychiatric case review was 25%, which occurred during the first month of treatment. Rates in subsequent months dropped to around 10%. New depression medications had a similar pattern, with the highest percentage of new medications seen in the second month of treatment (16.9%), and a subsequent drop in new medications in the following months. Results of the adjusted analysis indicated that psychiatric case review in any given month was associated with nearly a doubling of the probability of a new depression medication in the following month from 10.9% (95% CI = 10.7 – 11.2%) to 20.1% (95% CI = 19.2 – 21.1%) (Figure 2).

Fig 1:

Rate of psychiatric case review and receipt of new antidepressant medications in the months after assessment among patients in a collaborative care model for treatment of depression.

Notes: Results are from a linear probability analysis that controlled for patients’ gender and age, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 score, and comorbid behavioral health conditions, as well as months since initial assessment, months since the clinic started the collaborative care model, and dichotomous clinic indicators.

Figure 2:

Average monthly receipt of new antidepressant medications among all patients in a collaborative care model for treatment of depression and among patients who did not improve by eight weeks of treatment, by receipt of a psychiatric case review in the previous month

Notes: Results are from a linear probability analysis that controlled for patients’ gender and age, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 score, and comorbid behavioral health conditions, as well as months since initial assessment, months since the clinic started the collaborative care model, and dichotomous clinic indicators.

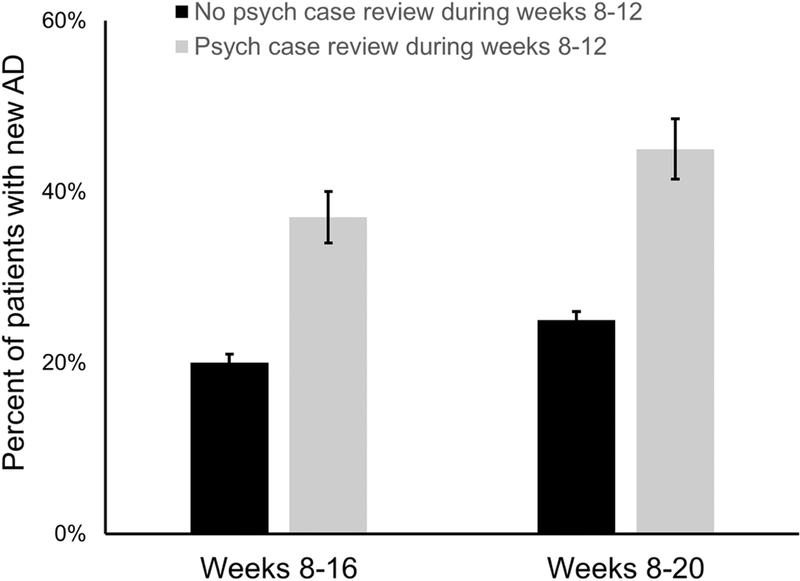

Among those patients who had not achieved significant improvement in depression at 8 weeks of treatment (n = 9892, 66.1%), a psychiatric case review in any month was associated with a significantly higher rate of new depression medications in the subsequent month (18.3% (95% CI = 16.7 – 19.9%) vs. 9.5% (95% CI = 9.3 – 10.0%)) (Figure 2). 9.1% of these patients received a psychiatric case review between weeks 8 – 12. Based on adjusted analysis, patients who received at least one psychiatric case review in weeks 8 – 12 had a significantly higher rate of new depression medications during weeks 8 – 16 (37% (95% CI = 34 – 40%) vs. 20% (95% CI = 20 – 21%)) or during weeks 8 – 20 (45% (95% CI = 42 – 49%) vs. 25% (95% CI = 25 – 26%)) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Receipt of new antidepressant medications during weeks 8–16 and weeks 8–20 among patients in a collaborative care model for treatment of depression who did not achieve clinically significant improvement in depression by eight weeks of treatment, by receipt of a psychiatric case review during weeks 8–12

Notes: Results are from a linear probability analysis that controlled for patients’ gender and age, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 score, and comorbid behavioral health conditions, as well as months since initial assessment, months since the clinic started the collaborative care model, and dichotomous clinic indicators.

DISCUSSION

In this analysis of data from a statewide program of collaborative care in safety net primary care clinics, receiving a psychiatric case review in any month was associated with twice the probability of receiving a new depression medication in the subsequent month. Further, among patients who did not achieve clinically significant improvement after 8 weeks of treatment, psychiatric case review during weeks 8 – 12 was associated with higher rates of new depression medications in the following weeks, even though only 9.1% received a psychiatric case review during this critical treatment period. In our prior work, we showed that psychiatric case review for patients who do not achieve improvement in depression by week 8 strongly predicted improvement within 6 months of treatment (18). Our current study specifically examines one important mechanism by which psychiatric case review could have led to improved patient outcome: through improved antidepressant management. Our findings indicate that timely psychiatric case review may have led to increased rates of new medications to treat depression by reducing clinical inertia.

Combined with the results of our prior study, our current findings suggest that improving rates of psychiatric case review in CCM may be one important strategy to improve outcomes. One system-level approach to improving rates of psychiatric case review could be the use of pay-for-performance initiatives, which significantly increased rates of psychiatric case reviews in CCM for depression (20). Such initiatives, which tie payment to meeting certain quality targets (such as a target rate of psychiatric case review among patients not improving), were also associated with improved depression outcomes (20). While these programs may require investments in collecting key quality parameters at a practice level (21), they can be relatively easily incorporated into the CCM for depression, as the model already focuses on tracking care processes and patients’ clinical outcomes (20).

Our study has several limitations. First, the identification of depression medication through documentation by care managers may under-report medication use compared to pharmacy claims or electronic health record data. This may, in part, explain the low rate of new medication to target depression (10 – 18% per month). Further, data limitation precluded evaluation of dose adjustments to medications already prescribed, which is another important form of treatment intensification. Also, treatment intensification through addition of various psychotherapies, adjustments in the type of psychotherapy provided or the intensity of a given therapy, or referrals to higher levels of care or alternative indicated treatment centers (such as substance abuse treatment) were also not evaluated. These limitations, however, would lead to an under-estimation of the impact of psychiatric case review on treatment intensification. An additional limitation is that given we relied on care manager updates of medication lists to identify new medications, there is the possibility that the act of case review itself could affect these updates. This could falsely increase the observed association between psychiatric case review and subsequent new depression medications. While, this is a possibility, we feel the likelihood of this occurrence is low and does not account for the entire degree of association we observed.

In addition, all patients who had a PHQ-9 score of 10 or higher were included in the study sample, regardless of their primary psychiatric diagnosis. Many patients who were included had diagnoses other than major depressive disorder, and a significant percentage had bipolar disorder, a comorbid psychotic disorder, or a comorbid substance use disorder. We included patients with substance use disorders in these analyses to better reflect clinical practice, in which patients are enrolled in CCM treatment regardless of diagnosis. Medication recommendations from psychiatrists in these cases may include medications to treat depression, as well as other classes of medications, such as antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, and promoters of alcohol abstinence. Although we included many of these medication classes in our analysis, data on some classes, such as medications to promote abstinence in substance use disorders, may not have been captured. Therefore, the rates of medication changes resulting from psychiatric case review that we observed among these complex patients with comorbidity may underestimate the actual number of treatment changes.

Finally, CCM is a complex, team-based intervention, and there are several steps between psychiatric recommendation for a medication change and the documentation of the change by a care manager at a clinic visit: the care manager must relay the recommendation to the PCP, the PCP must send the prescription to the pharmacy, the patient must pick up the prescription and begin taking it, the care manager must confirm that the patient has started to take the medication, and then document this change in the registry. The current study supports the psychiatric review as a critical component to reduce clinical inertia and promote prompt treatment intensification in this complex intervention. Further work is needed to understand the optimal clinical workflow and protocols for data reporting in order to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of the model in clinical settings.

CONCLUSIONS

Using data from a large sample of a real-world implementation of CCM for depression, our study provides strong evidence that psychiatric case review is associated with changes in antidepressant treatment. Our findings support our hypothesis that psychiatric case review is one of the aspects contributing to treatment intensification in CCM for depression, thereby reducing clinical inertia. Overall low rates of documented psychiatric case review suggest that efforts to increase rates of case review may further improve treatment intensification. Future studies should also examine other aspects of treatment intensification, such as changes in behavioral treatments, changes in medication dosing, or referrals to higher levels of care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to thank Suzy Hunter, Youlim Choi, and Phyllis Johnson (Weill Cornell) for their excellent programming support. The authors would also like to thank Community Health Plan of Washington (CHPW) and Public Health Seattle & King County for sponsorship and funding of the Mental Health Integration Program (MHIP) and for data on quality of care and clinical outcomes collected in the context of ongoing quality improvement.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Mental Health Integration Program (MHIP) registry data were originally collected for quality improvement purposes and were funded by Community Health Plan of Washington and Public Health of Seattle and King County. YB and PJ were supported by grant number 1R01MH104200 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pratt LA, Brody DJ: Depression in U.S. Household Population, 2009–2012. [Internet], 2014. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db172.htm [PubMed]

- 2.Pence BW, O’Donnell JK, Gaynes BN: The depression treatment cascade in primary care: a public health perspective. Current Psychiatry Reports 14: 328–335, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al. : Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62: 629–640, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krym VF, Crawford B, MacDonald RD: Compliance with guidelines for emergency management of asthma in adults: experience at a tertiary care teaching hospital. CJEM 6: 321–326, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Connor PJ, Sperl-Hillen JM, Johnson PE, et al. : Clinical Inertia and Outpatient Medical Errors [Internet]; in Advances in Patient Safety: From Research to Implementation (Volume 2: Concepts and Methodology). Edited by Henriksen K, Battles JB, Marks ES, et al. Rockville (MD), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2005. [cited 2017 Feb 4]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK20513/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oh S- W, Lee HJ, Chin HJ, et al. : Adherence to clinical practice guidelines and outcomes in diabetic patients. International Journal for Quality in Health Care: Journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care 23: 413–419, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pittman DG, Fenton C, Chen W, et al. : Relation of statin nonadherence and treatment intensification. The American Journal of Cardiology 110: 1459–1463, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roumie CL, Elasy TA, Wallston KA, et al. : Clinical inertia: a common barrier to changing provider prescribing behavior. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety 33: 277–285, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henke RM, Zaslavsky AM, McGuire TG, et al. : Clinical inertia in depression treatment. Medical Care 47: 959–967, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hepner KA, Rowe M, Rost K, et al. : The effect of adherence to practice guidelines on depression outcomes. Annals of Internal Medicine 147: 320–329, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, et al. : Clinical inertia. Annals of Internal Medicine 135: 825–834, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aujoulat I, Jacquemin P, Rietzschel E, et al. : Factors associated with clinical inertia: an integrative review. Advances in Medical Education and Practice 5: 141–147, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Unützer J, Katon W, Williams JW, et al. : Improving primary care for depression in late life: the design of a multicenter randomized trial. Medical Care 39: 785–799, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, et al. : Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 10: CD006525, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. : Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 288: 2836–2845, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katon WJ, Lin EHB, Von Korff M, et al. : Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. The New England Journal of Medicine 363: 2611–2620, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin EHB, Von Korff M, Ciechanowski P, et al. : Treatment adjustment and medication adherence for complex patients with diabetes, heart disease, and depression: a randomized controlled trial. Annals of Family Medicine 10: 6–14, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bao Y, Druss BG, Jung H- Y, et al. : Unpacking Collaborative Care for Depression: Examining Two Essential Tasks for Implementation. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.) 67: 418–424, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB: The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine 16: 606–613, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Unützer J, Chan Y-F, Hafer E, et al. : Quality improvement with pay-for-performance incentives in integrated behavioral health care. American Journal of Public Health 102: e41–45, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bremer RW, Scholle SH, Keyser D, et al. : Pay for performance in behavioral health. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.) 59: 1419–1429, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.