Abstract

Objectives:

Latina women are disproportionately affected by HIV in the US, and account for 30% of all HIV infections in Miami-Dade County, Florida. The main risk for Latina women is heterosexual contact. Little is known about the relational and cultural factors that may impact women’s HIV risk perception. This study aims to describe Latina women’s perception of their HIV risk within a relational, cultural, and linguistic context.

Design:

Eight focus groups of Latina women (n = 28), four English speaking groups and four Spanish speaking groups, were conducted between December 2013 and May 2014. Women were recruited from a diversion program for criminal justice clients and by word of mouth. Eligibility criteria included the following: self-identify as Hispanic/Latino, 18–49 years of age, and self-identify as heterosexual. A two-level open coding analytic approach was conducted to identify themes across groups.

Results:

Most participants were foreign-born (61%) and represented the following countries: Cuba (47%), Honduras (17.5%), Mexico (12%), as well as Nicaragua, Puerto Rico, Colombia, and Venezuela (15%). Participant ages ranged between 18 and 49, with a mean age of 32 years. Relationship factors were important in perceiving HIV risk including male infidelity, women’s trust in their male partners, relationship type, and getting caught up in the heat of the moment. For women in the English speaking groups, drug use and trading sex for drugs were also reasons cited for putting them at risk for HIV. English speaking women also reported that women should take more responsibility regarding condom use.

Conclusion:

Findings emphasize the importance of taking relational and cultural context into account when developing HIV prevention programs for Latina women. Interventions targeting English speaking Latina women should focus on women being more proactive in their sexual health; interventions focused on Spanish speaking women might target their prevention messages to either men or couples.

Keywords: Hispanic, HIV, women, condom, relationship, gender roles, mariansimo, machismo

… I have risked myself for a lot of things, and that’s one of the main things, that I think for Cuban ladies, fall into these trap of these men because we love hard and we’re wife material: we do to please them whatever they want, and we do. [24 year old Cuban-American woman, English Group 1]

Lowering the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection rate in the United States remains a major public health priority. Currently, there are approximately 1.1 million people living with HIV in the United States (Millett et al. 2010) with the majority of cases being from populations of color. Latinos, who comprise only 17% of the US population; account for 21% of all new HIV infections (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2015). In metropolitan areas with large Latino populations such as Miami, the HIV rate may be higher. For example, between 2004 and 2013, the proportion of all newly reported HIV infections among Latinos in Miami-Dade County increased from 34% to 46% (FDOH 2014); and, adult HIV infections among Latinos led all other race/ethnic groups making Latinos the most affected group in Miami (FDOH-MDC 2014).

Latina women have also been disproportionately impacted by the virus. In the United States they account for 19% of all women living with HIV and approximately 30% of all HIV infection cases among women in Miami-Dade County (CDC 2014; FDOH-MDC 2014). Most (84%) new infections among Latina women are transmitted through heterosexual contact (CDC 2014). Perceived susceptibility to HIV plays an important factor in condom decision-making. Previous evidence demonstrates that some individuals’ under-estimate their risk of HIV as opposed to overestimating it (Cianelli et al. 2010). In the case of Latina women, they may perceive themselves to be at low risk for HIV based on their own personal behavior even though their partner’s behaviors may be high risk. This low risk perception may be more prominent among recent immigrant women, or women who are less acculturated to the US culture versus women who were born in the United States (Sánchez et al. 2010). In the present study, we wanted to describe Latina women’s perception of their risk for HIV, and whether perceptions varied by language preference. We conducted focus groups with both English-speaking and Spanish speaking Latina women living in Miami, Florida to explore how Latina women perceive their own HIV risk; and whether themes regarding risk vary by the women’s language preference.

Traditional gender roles and HIV risk

The theory of gender and power suggests that the power differential between men and women affects health behaviors such as sexual communication and other HIV-related behaviors (Alvarez and Villarruel 2015; Wingood and DiClemente 2000). Connell (1987) wrote that the theory of gender and power consisted of three concepts: sexual division of labor, the sexual division of power, and cathexis. Cathexis refers to the affective attachments and social norms that women may prescribe to and emphasize as their role as sexual partners. (Raj et al. 1999; Wingood and DiClemente 2000). It is essentially the affective aspect of condom decision-making, which is heavily influenced by cultural norms and traditional gender roles.

Gender inequalities in the Hispanic culture can be seen in cultural concepts such as machismo/caballerismo and marianismo. Machismo refers to the social dominance and opportunities that men have over women in economic, legal, judicial, political, cultural, and psychological areas. This cultural component is problematic since young men are expected to be sexually experienced before and after marriage, and this may increase the risk of HIV and other STI’s for their partners (Cianelli, Ferrer, and McElmurry 2008). Yet, machismo also seems to have a positive aspect, which has been referred to in the literature as caballerismo. Caballerismo is linked to more positive attributes such as social responsibility, emotional connectedness (Arciniega et al. 2008), and a good provider for the family. Caballerismo has also been linked to positive traits such as self-esteem (Ojeda and Piña-Watson 2014). Just as machismo/caballerismo are the gender expectations for men, marianismo is the gender expectations for women. Marianismo refers to the notion of women being chaste, and subordinate to others (Piña-Watson et al. 2016; Piña-Watson et al. 2014); especially to their male partners. Cultural characteristics for marianismo include abstinence until marriage, bearing children, devotion, and duty to the family (Villarruel et al. 2007). For women, the cultural value of marianismo also encourages women to be ‘good wives’ by being submissive and dependent on men. Women are expected to restrict their feelings, opinions and choices and relinquish this role to men. These beliefs may lead women to deny their partner’s infidelities, which may expose them to HIV and/or other STI’s. Based on marianismo, women are expected to suppress their opinions about intercourse and make themselves sexually available to men, which may explain the negative association of contraception and condom use among Hispanic women (Cianelli, Ferrer, and McElmurry 2008; Villarruel et al. 2007).

Traditional gender roles are very prominent in the Hispanic culture. Along with a strong promotion of masculinity and early sexual behavior, machismo also refers to displays of strength, aggression, and protective behaviors toward family (Pardo et al. 2012). In the Latino culture, decisions regarding sexual intercourse and discussion of sexual topics are commonly the responsibility of the men and it is considered inappropriate for women to discuss sexuality (Rojas-Guyler, Ellis, and Sanders 2005). Due to the stereotypical ideal of machismo, Hispanic men possess more control over sexual relationships which can lead to power struggles that hinder sexual communication and negotiation for Hispanic women (Soler et al. 2000). This power imbalance between Hispanic men and women may contribute to the risk of heterosexual transmission of HIV among Hispanic women (Rojas-Guyler, Ellis, and Sanders 2005).

Acculturation as a risk factor

Acculturation differences among Hispanic immigrants may also have an influence on HIV/AIDS risk behaviors. Acculturation refers to the process in which immigrants adopt attitudes, language, and norms of the dominant culture (Marin and Marin 1991). There are both unidimensional and multi-dimensional measures of acculturation (Wallace et al. 2009). Recent studies suggest that acculturation as a concept is very complex, and should include environmental factors such as the role that the context of reception may play in the acculturation process (Schwartz et al. 2010). However, language use is also often used as a reliable proxy measure of acculturation mainly because it correlates well with other acculturation measures; it explains most of the variance in acculturation scales, and it is easily administered (Lara et al. 2005; Hunt, Schneider, and Comer 2004; Oh et al. 2011).

The traditional roles for Hispanic women can potentially be challenged by the US culture during the acculturation process (Rojas-Guyler, Ellis, and Sanders 2005). These cultural differences can lead to more risky sexual behaviors among Hispanic women. Previous findings have demonstrated a positive relationship between levels of acculturation and sexual risk behaviors (Schwartz et al. 2011). Compared to women with higher acculturation levels, less acculturated women were less likely to have multiple partners, report a lower number of lifetime partners, and report later age of first sexual intercourse (Rojas-Guyler, Ellis, and Sanders 2005; Lee and Hahm 2010).

However, previous studies have shown less acculturated Hispanic women may be more at risk for HIV infection than more acculturated women due to a lack of sexual communication and safer sex negotiation with their partners (Albarracin, Albarracin, and Durantini 2008; Alvarez and Villarruel 2015), and they are less likely to report consistent condom use (Rojas-Guyler, Ellis, and Sanders 2005). Other studies have also suggested that highly acculturated Hispanic women are less likely to use contraception (Roncancio, Ward, and Berenson 2012). HIV prevention programs need to take into account the varying risk factors among both groups of women in order to properly tailor risk reduction interventions (Rojas-Guyler, Ellis, and Sanders 2005) including relationship and cultural factors. In order to better tailor intervention for Latina women, a clearer understanding of how they perceive their own risk within the context of their relationships is needed.

Theoretical framework

The Information-Motivation-Behavioral skills (IMB) Model of HIV preventive behavior (Fisher and Fisher 1992) is a widely utilized theoretical model to guide HIV prevention research. Although initially developed some 15 years ago, the model remains a well-established conceptualization for explaining HIV risk and prevention efforts (Fisher et al. 2002). The IMB model was deemed appropriate for this study for several reasons: (1) it continues to be used for effective HIV prevention interventions (Fisher et al. 2002; Malow et al. 2009); (2) it emphasizes elicitation research, which is congruent with qualitative research; and (3) it has been used successfully with Latino populations (Jones et al. 2008; Knauz et al. 2007; Malow et al. 2009). In brief, the IMB model posits that HIV preventive behavior is a function of three primary factors: (1) information about HIV transmission and prevention; (2) motivation to reduce HIV risk; and (3) acquisition of behavioral skills for performing risk reduction. Relationship and cultural factors may serve as moderator of these factors. For example, gender norms could influence how much information a woman has, and cultural factors could influence the motivations that Latina women may hold regarding HIV prevention behaviors such as condom negotiations.

The present study

Based on the Information, Motivation, and Behavioral theory (IMB) (Fisher, Fisher, and Harman 2003), the present study utilized a focus group methodology to examine barriers to condom use among Latina women living in Miami, Florida. Interview guide questions focused on information-, motivational-, and behavioral-related factors of HIV risk. Data from eight focus groups (four groups of English speaking women; four groups of Spanish speaking women) were collected between December 2012 and June 2013 as part of a larger study to develop an HIV prevention intervention for Latinos. Language is often used as a proxy for acculturation and therefore, groups were conducted separately by language to explore any differences in risk by acculturation. A thematic analysis using a two-level open coding analytical approach was conducted to identify recurrent themes across groups.

Method

Participants

Eight focus groups were conducted with a total of 28 Latina women. Nine participants were recruited from the Advocate Program, a social service agency for those who are involved in the criminal justice system. Nineteen were recruited from other community agencies or word of mouth. Focus group participants were grouped by language preference; that is, four groups of Spanish-speaking Latina women (n = 13), and four groups of English-speaking Latina women (n = 15). Female participants racially identified as white (68%), black (3.5%), and other (28.5%). The ‘other’ category included terms such as American, Hispanic, Latina, Latin-Hispanic, mixed, and Mexican American. Most participants were foreign-born (61%) and represented the following countries: Cuba (47%), Honduras (17.5%), Mexico (12%), as well as Nicaragua, Puerto Rico, Colombia, and Venezuela (15%). Participant ages ranged between 18 and 49, with a mean age of 32 years (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics of the focus group participants.

| Variables | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Race | |

| White | 19 (68%) |

| Black | 1 (4%) |

| Other | 8 (28%) |

| Country of Origin | |

| US | 11 |

| Cuba | 8 |

| Nicaragua | 1 |

| Honduras | 3 |

| Colombia | 1 |

| Puerto Rico | 1 |

| Mexico | 2 |

| Venezuela | 1 |

| Time in United States | |

| Native born | 11 |

| 1−5 years | 1 |

| 6–10 years | 4 |

| 11–15 years | 4 |

| 16–20 years | 4 |

| 20+ years | 4 |

| Criminal Justice/Drug Involved | 21 |

| Related to someone CJ/Drug Involved | 7 |

Note: CJ = Criminal justice.

Procedure

We began recruiting focus group participants in December 2012 at The Advocate Program. We focused on three sites in Miami-Dade County: Little Havana, the Doral area, and the South Dade area of Miami because of the diverse Latino clientele, but most of our recruiting efforts were spent in Little Havana due to its high Latino population. Recruitment was done via presentation to the classes/groups of clients held at The Advocate Program, or by approaching clients in their waiting rooms. Flyers explaining the study were also posted in these locations. Participants were given a card or flyer with all the study contact information or they provided their contact information to obtain more details about participating in the study. Most participants signed up to learn more about the study. The project director called each potential participant, described the study in detail; and, if the participant was interested, conducted a brief phone screener to determine eligibility. Once participants were found eligible, they were scheduled for a focus group.

Focus group participants were initially deemed eligible if they were in some type of substance use outpatient program, involved in the criminal justice system, self-identified as Hispanic or Latino, were between 18 and 49 years of age, and self-identified as heterosexual. After a couple of months, we encountered difficulties finding women participants because they were underrepresented in the Advocate Program. Therefore, the recruitment criteria was expanded to also include Latina women who were related or involved with someone with criminal justice involvement (see Table 1 for a breakdown). We advertised the study via flyers and were able to recruit Latina women from other treatment programs as well as through those who had family members or friends attending classes at The Advocate Program. All together we screened 69 women. Of those, 51 women were eligible. Reasons for ineligibility included age, sexual orientation, or they simply were no longer interested or too busy to participate.

The eight focus groups contained two to seven women in each group with an average of four per group. There were 15 women in the English speaking groups and 13 women in the Spanish speaking groups. The groups lasted approximately 60–90 minutes. Each group was audio-recorded. There was a moderator and an assistant taking notes. Participants were consented before the group began and some general rules were provided such as the importance of maintaining the confidentiality of the group members. Each participant was given a number and was subsequently identified by that number in the group. No names were used in the group. Because this was a larger study on developing an HIV and Hepatitis C (HCV) prevention intervention, the interview guide consisted of several topic areas and questions including knowledge about HIV and HCV, motivations and attitudes toward risk reduction, barriers to risk reduction, HIV-related behavioral skill deficits and strengths, and real life safer sex decision-making scenarios. For the present study, the following questions from the interview guide were relevant: (1) what would you say are the attitudes about condom use among you and friends (probe: how about attitudes of your family? Of Latino men? Of Latina women); (2) what are some situations that make it hard for someone to be safe or reduce their risk for HIV? HCV?; (3) What might have helped that person to be safe or reduce their risk in that situation; and (4) how is condom use viewed in the Latino culture? All focus group discussions were transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis plan

NVivo qualitative data analysis software (QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 10, 2012) was used to analyze the transcripts. A two-level open coding approach was conducted. First, all focus group transcriptions were analyzed for emergent themes using a grounded theory approach (Glaser and Strauss 1967). The first level served as a form of data categorizing and organization. Two bilingual, bicultural, independent coders (Project Director, and a graduate research assistant) coded all the transcripts for main themes. Once a theme was identified, coders would select the block of text representing that conversation or discussion that included the theme. After the first transcript, the coders met to agree on the main themes. Agreement was reached by consensus. Ten main themes emerged from this first level of open coding of the data: Background, Communication, Condom Use, Culture, Drug & Alcohol, Knowledge, Love & Trust, Meeting Place, Perception of Problem, Scenarios, & Stigma. These themes were used to create a codebook, and all subsequent transcripts were coded using this codebook. Both coders would code each focus group transcript independently and then meet to determine agreement after each focus group. This was done for all groups until all focus group transcriptions were categorized into these themes. Inter-coder reliability was good with an overall Kappa of .80. A second level of open coding was then conducted with the theme of interest for the present study – Condom Use.

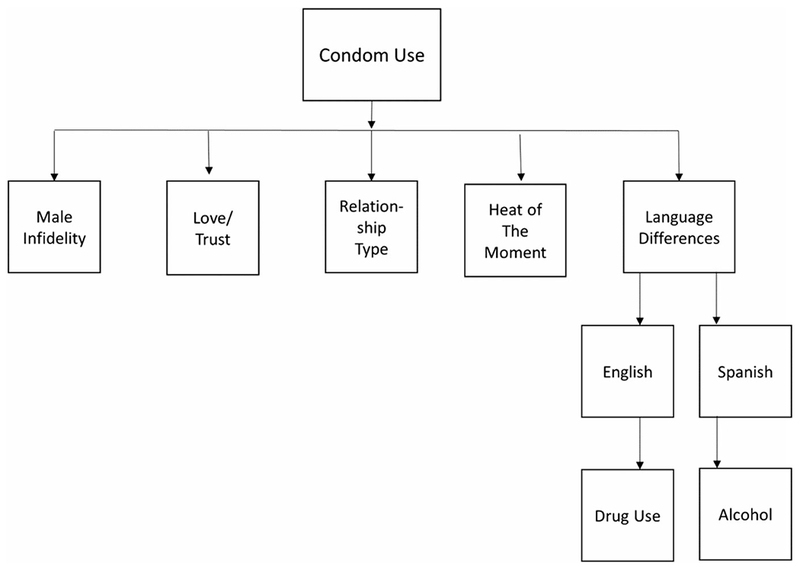

The main theme of Condom use included any references to condom use including attitudes, behaviors, and reasons for using or not using condoms. This main theme was further analyzed using an open coding approach for sub-themes. The lead author coded Condom Use for sub-themes by hand, which comprises the main findings for this paper (see Figure 1 for coding scheme). The themes that were mentioned the most are presented here. For the purposes of trustworthiness, all sub-themes discussed more than once, and how many times they were mentioned by groups are presented in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Coding scheme diagram.

Table 2.

All sub-themes and times mentioned across groups (n = 28).

| Subthemes | E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Use as Risky | 5 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 17 | |

| Relationship Type | 5 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 17 | |

| Love as a risk/Trust | 3 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 14 | |||

| Male Infidelity | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 12 | |||

| Alcohol | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 10 | ||

| Heat of the Moment | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 9 | |||

| Men don’t like condoms/don’t want to use/don’t have | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 9 | |||

| Men don’t care about being safe/riskier | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 7 | |||

| Sex feels better without condoms | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 | ||

| Women don’t use/like condoms | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 6 | ||||

| Latino men sexually curious, want anal sex | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||||

| Men hypersexual | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |||||

| Commitment means no condoms | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | |||||

| Women weak/need to get tougher/allows infidelity | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | |||||

| Women promiscuous/multiple partners | 4 | 4 | |||||||

| Women responsible | 2 | 2 | 4 | ||||||

| Condom discussion | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | |||||

| Protective factors | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | |||||

| Never/rarely used a condom | 4 | 4 | |||||||

| Always uses condoms/condom use accepted | 3 | 1 | 4 | ||||||

| Condom use/testing when trading sex | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||

| Women get checked/tested | 3 | 3 | |||||||

| Appearance | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||||||

| Women decide condom use | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||||

| Men don’t use condoms/women use condoms as power | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Men take condoms off/ejaculate inside | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Women don’t like anal sex | 2 | 2 | |||||||

| Risky if knows partner for long time | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Use condoms as contraceptive | 2 | 2 | |||||||

| Don’t want to offend/want to feel love | 2 | 2 | |||||||

| Trading sex – no condoms | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Men decide condom use | 2 | 2 | |||||||

| Tricking – with condoms | 2 | 2 | |||||||

| Single women carry condoms | 2 | 2 | |||||||

| Condom use as birth control issue | 2 | 2 | |||||||

| Machismo | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||

| Women are embarrassed to buy condoms | 2 | 2 | |||||||

| No condom discussion between couple | 2 | 2 | |||||||

| Foreign-born men/men offended if you want to use condoms | 2 | 2 |

Notes: E1 = English-speaking women group 1 (n = 5); E2 = English-Speaking women group 2 (n = 2); E3 = English-speaking women’s group 3 (n = 5); E4 = English-speaking women’s group 4 (n = 3); S1 = Spanish-speaking women’s group 1 (n = 2); S2 = Spanish-speaking women’s group 2 (n = 2); S3 = Spanish-speaking women’s group 3 (n = 5); S4 = Spanish-speaking women’s group 4 (n = 4).

Results

Women spoke about some of the reasons they did not use condoms and other factors that put them at risk for HIV. All the sub-themes mentioned more than once across all groups are listed in Table 2. However, the most recurrent sub-themes related to condom use behavior for Latina women were: Male Infidelity, Love and Trust, Relationship Type, and the Heat of the Moment. Most of these recurrent subthemes were found to be common across both English and Spanish speaking women’s groups. However, there were also other sub-themes unique or more predominant in either the English speaking or the Spanish speaking groups. Recurrent subthemes are presented below.

Common themes mentioned by both English and Spanish speaking women

Male infidelity

Five out of the eight groups mentioned male infidelity as a risk factor, and it was a theme found among both English and Spanish speaking women. Some women spoke about male infidelity in general terms and as if it were part of the cultural norm or characteristic of being a man; whereas others spoke specifically about their own partner’s betrayal. Below, one woman speaks to men’s behavior in general but also suggested that women are also promiscuous; whereas another woman speaks about the consequences she experienced because of her own partner’s infidelities.

“but they, they are not faithful, the men go out to the corner and they are already looking around at other women, and the women also, on the street are bad …” (Original transcript: “… pero ellos, no son fieles, los hombres salen a la esquina y ya están viendo pa’ los lados otras mujeres, y las mujeres también, en la calle estan de madre” [42 year old Venezuelan-born woman, Spanish Group 2])

… he would go and sleep with girls behind my back, he would go sleep with his baby mama behind my back, he slept with my best friend, without a condom, he used like, he never used a condom with nobody, he ended up giving me something and I had to have it cured … [22 year old Cuban-American woman, English Group 3]

Although one woman spoke about other risk factors, she perceived her main risk factor for HIV was male infidelity because she would not use condoms with her regular partner who was also paying for sex with multiple partners.

… when I used to do drugs, I used to go, I used to get money to go have sex. I used to sell myself too, but I always used a condom outside, but with him I never did, and little did I know, that he was out there paying for girls too … [24 year old Cuban-American woman, Group 1]

Others suggested that male infidelity was the woman’s responsibility. There was some talk that it is part of the culture and that male infidelity continues because women allow it. It was also implied that it is women’s responsibility if they choose to stay in a relationship with a man that cheats. That is, women need to use condoms with regular partners that are known to cheat. This theme is seen in the quotes below.

“that comes from the culture, but it’s because the women permit it, the women also are doing, by letting them, the day that women say enough, I think they will solve that situation” (Original Transcript: “eso viene en la cultura, pero es porque las mujeres se lo permiten, la mujer también está haciendo, para permitírselo, el dia que la mujer diga hasta aqui, yo pienso que ellos va a componer esa situación” [47 year old Honduran-born woman, Spanish group 3])

“if you know that your partner is unfaithful and that person decides to stay with that person, you need to use a condom” (Original Transcript: “si sabe que su pareja le es infiel y esa persona decide seguir con esa persona, tiene que usar condón” [47 year old Honduran-born woman, Spanish group 3])

Love and trust

For Latina women, there was a lot of discussion around the concept of love and trust being a risk factor for them. Part of being in a loving relationship for them meant trusting their partners even though this seems contradictory to the general notion held by women, which is that men have multiple partners.

When you love somebody you’re open to a lot of hurting, a lot of pain, a lot of diseases, because, at least personally me speaking, I love, and when I love I love hard … we do to please them whatever they want, and we do … but at least me, when I loved him so much, I knew he was out there cheating and I would still go ahead and sleep with him and still put myself in that danger. [24 year old Cuban-American woman, Group 1]

Latina women reported that the way they show their love to their partners is by trying to please them even if it meant putting themselves at risk. Not using a condom was seen as a sign of love, commitment, and intimacy.

women, sorry to say this, sometimes they [women] do whatever the men says they want to do [22 year old Cuban-born woman, Group 3]

… and you feel like you guys are in love or you like him a lot, whatever, you’re gonna fuck him without a condom … [20 year old Cuban-born woman, English group 4]

you wanna feel loved and that person doesn’t feel like you know you’re loving them if you have to wear a condom [27 year old Cuban-born woman, English group 4]

One woman suggested that in the Latino culture, women are taught to trust their partners and to do what the men want, while men are taught that they can do whatever they want and should not be held accountable.

“To the woman, they teach her to confide in their partner, and follow him, but the man is taught the opposite, you are the man and you do not need to give reasons nor information” (Original Transcript: “a la mujer la educaron para confiar en su pareja, y seguirlo, pero al varón le enseñaron lo diferente, es usted el hombre usted no tiene que dar razones ni información.” [39 year old Honduran-born woman, English group 4])

Relationship type

Condom use seems to be heavily dependent on relationship status for women. They reported using condoms with partners that they did not know very well, but for those who they knew or had been in a relationship with for a while, they would typically not use a condom. Again, suggesting that not using condoms represents intimacy and connectedness.

It depends on the relationship you have with the guys too because if he’s your man, and he doesn’t wanna use it, and also depends if you’re in the moment, … you’re gonna be like, oh forget it, just come on, but if it’s a stranger, you should put down on that, like not just give up so easily. [20 year old Cuban-born woman, English group 4]

“When I do not know a person, I have used it [condom] … but if for example I am with the children’s father, I do not use condoms.” (Original Transcript: “cuando yo no conozco una persona, yo lo he usado … pero si por ejemplo yo estoy con el papa de las niñas, no uso condones”. [29 year old Cuban-Puerto Rican woman, US born, Spanish Group 4])

Heat of the moment

For Latina women, discussion of their sexual risk seemed to be interwoven with their relationship context. In addition to talking about love and trust as putting them at risk and the type of relationship they have with their male partners, they also talked about passion and the ‘heat of the moment’. Women spoke about getting caught up in the moment and even if they had condoms or knew they should use condoms, they wouldn’t think of using them at that moment.

Once you get into it and the hormones and the heat gets turned on, it’s like that’s the last thing you thinking about [condoms] … [33 year old Honduran-American woman, English Group 2]

You just get so turned on, whatever you wanna call it and then like you just don’t think and then you just don’t use protection or whatever and then like when that happened to me I was like wow, why did I do that. [31 year old woman, country of origin data missing, English Group 3]

Some women suggested having the condom ready and available so that when the heat of the moment occurred it would be easier to use condoms.

“… You got to have the condom close, so that when the heat of the moment is bad, you don’t have to stand and walk to the bathroom to look for it, it is right there.” (Original Transcript: “… Tiene que ir al condón acerca, pa’que cuando el momento de calor esta ya grave, tú no tienes que pararte y caminar al baño a buscarlo, está allí mismo” [42 year old Cuban-American, Spanish Group 3])

Themes more predominant among the English speaking than Spanish speaking women

Drug use as a risk factor

Women mentioned drug use as a major risk factor for not using condoms. Although this theme was mentioned at least once in all but one group, the English speaking women talked about drug use more often within their groups than the Spanish speaking women. As mentioned in the following quotes, women discussed their own risky behaviors and situations while under the influence of drugs.

I barely wore a condom and I think about when I was on drugs and I didn’t care and, you know, when you’re on drugs you tend to do things you wouldn’t do when you’re sober, and I did have a lot of unprotected sex while I was using [38 year old Cuban-American woman, English Group 1]

I remember one time I got so high I was passed out, cause I was on Xanax, and then heroin, and all that stuff so I would do a shot, pass out and when I woke up I saw this guy on top of me … [33 year old Honduran-American woman, English Group 2]

The English speaking women talked about drugs in the context of trading sex for drugs or money. Trading sex was not mentioned in the Spanish group at all; however, it seemed to be part of the English speaking women’s drug use history. Because of their addiction, women were less careful with their sex trading partners especially if they were ‘regulars’.

I did have my two or three tricks, and he didn’t have a condom and it was like … oh let me go to the store to get a condom, and I was just so ready to be like look forget it, let’s get it done, cause I was worried about getting my next hit so, you know definitely an addiction, very, very high risk, cause all you’re worrying about is the next hit. [33 year old Honduran-American woman, Group 2]

Women’s role and responsibilities

The English speaking women were also more likely to talk about women’s role in making sex safer and discussing the need for women to take responsibility and exercise over their sexual health than the Spanish speaking women.

If we’re with somebody, we gotta know who we with to begin with. You gotta know who you’re giving it raw to, ‘cause at the end of the day, you’re the one laying in bed with them. They’re not forcing you to lay in bed with them. It was your option and your choice. [19 year old Cuban-born woman, Group 1]

One woman suggested that the use of contraceptives is typically a woman’s decision and therefore, condom use should be their decision as well.

It’s really up to the woman, you know, … because it’s the woman that gets the double shot, the woman that gets their tubes tied, the woman that gets the IUD, the woman that takes the pill, you know … [33 year old Honduran-American woman, Group 2]

Theme more common among the Spanish speaking rather than English-speaking women

Alcohol

In the Spanish speaking focus groups, the women spoke more about the effects of alcohol use on sexual risk behaviors than the English speaking women. They reported being worried for their single friends who go out and get drunk, and that drinking affects their judgment. In fact, one woman suggested that alcohol affects women more than men. The following quotes displays these themes.

“I am afraid for some of my friends because they go to the clubs and drink too much, they get drunk and they go with any good looking man they find.” (Original Transcript: “yo tengo miedo por alguna de mis amigas porque van a las discotecas y toman mucho, se emborrachan entonces se van con cualquier hombre bonito que se encuentran”) [28 year old Cuban-American woman, Spanish Group 1]

“With the women I think the alcohol affects the women more” (Original Transcript: “con las mujeres creo que el alcohol le afecta más a las mujeres”) [28 year old Cuban-American woman, Spanish Group 1]

“I think that when the people are drunk, they don’t think” (Original Transcript: “yo pienso que cuando la gente estan tomados, no piensan …”) [47 year old Honduran-born woman, Spanish Group 3]

Discussion

Summary of findings

Latina women discussed perceptions of their HIV risk mainly within a relational context focused on love and trust as risk factors, male infidelity, condom use by relationship type, and getting caught up in the heat of the moment. The concept that cathexis, or the notion that affective attachment and social norms (Connell 1987; Wingood and DiClemente 2000), leads to a lack of power within the relationship, was evident in all groups. The need for more attention on the emotional aspect of HIV risk, especially for women, has been emphasized in previous studies (Syvertsen et al. 2015; Wingood and DiClemente 2000), yet a minority of HIV prevention theories or interventions address this emotional aspect. In a recent study, Syvertsen et al. (2015), found that among Latina sex workers, unprotected sex with their primary partner was related to love and trust. In contrast, they found men were more likely to agree that they might have other partners whereas the women reported that they will be with their partners for life (Syvertsen et al. 2015). Other studies report women not using condoms with their partners for fear of losing them (Cianelli et al. 2013). The women in our study also reported that male infidelity was a common risk factor, yet continued abstinence from condoms to establish emotional connectedness. Previous studies have also found this contradiction of women’s knowledge or expectations of male infidelity but still continue to put themselves at risk by not using condoms (Cianelli, Ferrer, and McElmurry 2008; Cianelli et al. 2013). Future prevention efforts should propose different ways that Latina women or couples can achieve emotional connectedness while still using condoms, as well as promoting condom use among men with their casual partners.

Previous studies have found cultural norms, such as machismo and marianismo, to be related to relationship dynamics important to HIV prevention such as condom negotiation skills (Cianelli, Ferrer, and McElmurry 2008; Cianelli et al. 2013; Gonzalez-Guarda et al. 2011; Peragallo 1996), and this is congruent with the present findings. However, future studies could also examine other cultural norms less understood regarding HIV risk such as simpatia, which refers to the importance for Latinos to maintain harmony within their relationships (Griffith et al. 1998), and which is evident when women stated that bringing up condoms would offend their partners. Another cultural norm is the importance of family relationships. Perhaps one way to address the emotional aspect of HIV risk is to focus on the importance offamily for Latina women. For example, one study found that family connectedness was related to less sexual risk taking among Latinos (Landau et al. 2000). HIV prevention efforts targeting Latina women might focus on how taking care of themselves is showing love and respect for their families. More qualitative research is needed to better understand and utilize positive aspects of cultural norms such as simpatia, family importance and machismo/caballerismo, in HIV prevention efforts.

Implications

Our findings have implications for HIV interventions targeting Latina women. There are currently 96 risk reduction interventions in the CDC’s HIV compendium, yet only 2 interventions are couple-level interventions (CDC 2016). Only one intervention included a subsample of Latino couples, Connect2 (El-Bassel et al. 2011). There is a need for more couple-level interventions targeting Latinos. Intervention studies targeting Latina women will need to take their relationship and cultural context into account to achieve effectiveness.

The present findings also suggest that theoretical models that attempt to explain HIV risk such as the IMB theory, need to include relationship and cultural factors. For example, Latina women’s strong desire for emotional connectedness with their primary partners appears to be a strong motivator and should be included in the IMB model as part of the motivation construct; cultural norms (i.e. marianismo, simpatia) have an impact on behavioral skills such as condom negotiation skills or condom use skills and could be an important moderator; and marianismo can also dictate how much knowledge a Latina woman may have about HIV. In sum, future studies should examine the role of relationship and cultural factors within the IMB model and other intrapsychic theoretical models, and whether they serve as mediating or moderating roles.

Finally, there were also some subtle differences in themes between the English and Spanish speaking women. For example, in the English speaking groups, drug use and tricking were discussed much more than the Spanish groups. In fact, none of the Spanish speaking women discussed tricking as a risk factor, and there was minimal references to drugs. For these women, alcohol seemed to play a larger role in participating in risky sexual behavior. This finding is congruent with the literature that suggests that drug use is a risk factor for Latina women (Cianelli et al. 2013; Gonzalez-Guarda et al. 2011) especially those who have lived in the US longer. This could be due to the fact that acculturated Latina women are more likely to use drugs than less acculturated women (Amaro and De la Torre 2002); or it could be that more traditional Latina women are more reserved and therefore less likely to acknowledge any drug use or tricking behavior in a group setting. Although additional risk factors such as drug use and tricking were discussed in the English groups, women seem to think their main source of risk for HIV was still their main partner’s infidelity.

Another interesting difference between the English and Spanish speaking women was how the English speaking women emphasized Latina women’s responsibility for being safe, and the important role that women played in their own sexual health. This topic was not heard in the discussion with the Spanish speaking women. For them, the responsibility for using condoms seemed to primarily rest on the men. This finding has implications for HIV prevention interventions with Latina women particularly for interventions that focus on intrapsychic factors such as motivational interviewing, empowerment theory, or the stages of change theory. The extent to which Latina women believe they are responsible and have the skills and power to enact changes in their sexual relationships will be important factors to consider when tailoring interventions to women with different acculturation levels. For example, interventions targeting highly acculturated women can utilize more proactive and individualistic strategies to effectively promote sexual health among Latina women; whereas interventions that work with less acculturated women may find it more effective to work with the couple or with the men directly in order decrease women’s risk.

Limitations and strengths

This study has several limitations. It had a small sample size and utilized focus groups based on a convenient sample; therefore, it should not be considered representative of the Latina population. However, the sample of women was diverse and represented several Latin American countries, as well as US born and foreign-born women. Because of the focus group setting, women may not have felt comfortable sharing. We tried to address this issue by emphasizing confidentiality within the group and by using two trained bilingual, bicultural facilitators. The groups also tended to be small, which made it easier for women to share. Lastly, some women were recruited from a diversion program and therefore were involved in some criminal justice case, while others were not. This was not assessed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the emotional aspect of Latina women’s relationships and condom use decision-making needs to be better understood by acknowledging the relationship context including power differentials that may exist due to emotional attachments and/or social norms. Future studies should examine how to tailor prevention messages such as using condoms in more culturally acceptable ways for women. Also, interventions that target Latina women should take acculturation into account. That is, interventions that target more English speaking Latina women may find it effective to focus on proactive strategies and empowerment-based interventions. On the other hand, to reduce HIV risk among Spanish speaking women, researchers may want to focus solely on men or develop couple-based interventions. Future studies should explore both options by conducting further qualitative research on their acceptability as well as piloting these interventions.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) under Grant R34DA031063. Steven Martin’s work was supported in part by an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant number U54-GM104941 (PI: Binder-Macleod).

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Albarracin J, Albarracin D, and Durantini M. 2008. “Effects of HIV-prevention Interventions for Samples with Higher and Lower Percents of Latinos and Latin Americans: A Meta-analysis of Change in Condom Use and Knowledge.” AIDS and Behavior 12 (4): 521–543. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9209-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez C, and Villarruel A. 2015. “Association of Gender Norms, Relationship and Intrapersonal Variables, and Acculturation with Sexual Communication among Young Adult Latinos.” Research in Nursing & Health 38 (2): 121–132. doi: 10.1002/nur.21645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaro H, and De la Torre A. 2002. “Public Health Needs and Scientific Opportunities in Research on Latinas.” American Journal of Public Health 92 (4): 525–529. doi: 10.1002/nur.21645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arciniega GM, Anderson TC, Tovar-Blank ZG, and Tracey TJG. 2008. “Toward a Fuller Conception of Machismo: Development of a Traditional Machismo and Caballerismo Scale.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 55: 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2014. “National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention. HIV among Women.” Accessed May 26, 2015 http://www.cdc.gov/HIV/risk/gender/women/facts/index.html.

- CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2015. “National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention. HIV and AIDS among Latinos.” Accessed May 26, 2015 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/racialethnic/hispanicLatinos/facts/index.html.

- CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2016. “Complete Listing of Risk Reduction Evidence-based Behavioral Interventions.” Accessed June 9, 2016 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/research/interventionresearch/compendium/rr/complete.html.

- Cianelli R, Ferrer L, and McElmurry BJ. 2008. “HIV Prevention and Low-income Chilean Women: Machismo, Marianismo, and HIV Misconceptions.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 10 (3): 297–306. doi: 10.1080/13691050701861439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cianelli R, Villegas N, Gonzalez-Guarda R, Kaelber L, and Peragallo N. 2010. “HIV Susceptibility among Hispanic Women in South Florida.” Journal of Community Health Nursing 27 (4): 207–215. doi: 10.1080/07370016.2010.515458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cianelli R, Villegas N, Lawson S, Ferrer L, Kaelber L, Peragallo N, and Yaya A. 2013. “Unique Factors that Place Older Hispanic Women at Risk for HIV: Intimate Partner Violence, Machismo, and Marianismo.” Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 24 (4): 341–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell RW 1987. Gender and Power: Society, the Person and Sexual Politics. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Wu E, Witte S, Chang M, Hill J, and Remien RH. 2011. “Couple-based HIV Prevention for Low-income Drug Users from New York City: A Randomized Controlled Trial to Reduce Dual Risks.” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 58: 198–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, and Fisher WA. 1992. “Changing AIDS-Risk Behavior.” Psychological Bulletin, 111 (3): 455–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Bryan AD, and Misovich SJ. 2002. “Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills Model-based HIV Risk Behavior Change Intervention for Inner-City High School Youth.” Health Psychology, 21 (2): 177–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher WA, Fisher JD, and Harman J. 2003. “The Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills Model: A General Social Psychological Approach to Understanding and Promoting Health Behavior” In Social Psychological Foundations of Health and Illness, edited by Suls J and Wallston KA. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. doi: 10.1002/9780470753552.ch4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Florida Department of Health. Florida data: Florida Department of Health. Bureau of Communicable Disease, HIV/AIDS and Hepatitis Section. 2014. Accessed May 26, 2015 http://www.floridahealth.gov/diseases-and-conditions/aids/surveillance/_documents/partnership-slide-sets/2014/part11a-14.pdf.

- Florida Department of Health Miami-Dade County: HIV/AIDS Surveillance. 2014. Accessed May 26, 2015 http://miamidade.floridahealth.gov/programs-and-services/infectious-disease-services/hiv-aids-services/_documents/hiv-surveillance-monthly-report-december-2014-12.pdf.

- Glaser B, and Strauss A. 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies of Qualitative Research. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Guarda RM, Vasquez EP, Urrutia MT, Villarruel AM, and Peragallo N. 2011. “Hispanic Women’s Experiences with Substance Abuse, Intimate Partner Violence, and Risk for HIV.” Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 22 (1): 46–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith J, Joe G, Chatham L, and Simpson DD. 1998. “The Development and Validation of a Simpatia Scale for Hispanics Entering Drug Treatment.” Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 20 (4): 468–482. doi: 10.1177/07399863980204004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt LM, Schneider S, and Comer B. 2004. “Should ‘Acculturation’ be a Variable in Health Research? A Critical Review of Research on US Hispanics.” Social Science & Medicine 59 (5): 973–986. doi:0.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SG, Patsdaughter CA, Jorda ML, Hamilton M, and Malow R. 2008. “Senoritas: An HIV/Sexually Transmitted Infection Prevention Project for Latina College Students at a Hispanic-Serving University.” Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 19 (4): 311–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knauz RO, Safren SA, O’Cleirigh C, Capistrant BD, Driskell JR, Aguilar D, Salomon L, Hobson J, and Mayer KH. 2007. “Developing an HIV-Prevention Intervention for HIV-infected Men Who Have Sex with Men in HIV Care: Project Enhance.” AIDS and Behavior 11 (Suppl. 5): S117–S126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau J, Cole R, Tuttle J, Clements CD, and Stanton MD. 2000. “Family Connectedness and Women’s Sexual Risk Behaviors: Implications for the Prevention/Intervention of STD/HIV Infection*.” Family Process, 39 (4): 461–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian MI, Morales LS, and Bautista DEH. 2005. “Acculturation and Latino Health in the United States: A Review of the Literature and Its Sociopolitical Context.” Annual Review of Public Health 26 (1): 367–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, and Hahm HC. 2010. “Acculturation and Sexual Risk Behaviors among Latina Adolescents Transitioning to Young Adulthood.” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 39 (4): 414–427. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9495-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malow RM, Stein JA, McMahon RC, Devieux JG, Rosenberg R, and Jean-Gilles M. 2009. “Effects of a Culturally Adapted HIV Prevention Intervention in Haitian Youth.” The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Case. 20 (2): 110–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin G, and Marin BO. 1991. Research with Hispanic Populations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Millett G, Crowley J, Koh H, Valdiserri R, Frieden T, Dieffenbach C, Fenton K, et al. 2010. “A Way Forward: The National HIV/AIDS Strategy and Reducing HIV Incidence in the United States.” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 55 (S2): S144–S147. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181fbcb04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh A, Dodd K, Ballard-Barbash R, Perna FM, and Berrigan D. 2011. “Language Use and Adherence to Multiple Cancer Preventive Health Behaviors among Hispanics.” Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 13 (5): 849–859. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9456-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda L, and Piña-Watson B. 2014. “Caballerismo May Protect Against the Role of Machismo on Mexican Day Laborers’ Self-esteem.” Psychology of Men & Masculinity 15: 288–295. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo Y, Weisfeld C, Hill E, and Slatcher R. 2012. “Machismo and Marital Satisfaction in Mexican American Couples.” Journal of Cross-cultural Psychology 44 (2): 299–315. doi: 10.1177/0022022112443854. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peragallo N 1996. “Latino Women and AIDS Risk.” Public Health Nursing 13: 217–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piña-Watson B, Castillo LG, Jung E, Ojeda L, and Castillo-Reyes R. 2014. “The Marianismo Beliefs Scale: Validation with Mexican American Adolescent Girls and Boys.” Journal of Latina/o Psychology 2: 113–130. [Google Scholar]

- Piña-Watson B, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Dornhecker M, and Martinez AJ. 2016. “Moving Away From a Cultural Deficit to a Holistic Perspective: Traditional Gender Role Values, Academic Attitudes, and Educational Goals for Mexican Descent Adolescents.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 63: 307–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj A, Silverman J, Wingood GM, and DiClemente RJ. 1999. “Prevalence and Correlates of Relationship Abuse among A Community-based Sample of low Income African-American Women.” Violence Against Women 5: 272–291. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-Guyler L, Ellis N, and Sanders S. 2005. “Acculturation, Health Protective Sexual Communication, and HIV/AIDS Risk Behavior among Hispanic Women in a Large Midwestern City.” Health Education & Behavior 32 (6): 767–779. doi: 10.1177/1090198105277330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roncancio AM, Ward K, and Berenson A. 2012. “The Use of Effective Contraception among Young Hispanic Women: The Role of Acculturation.” Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 25 (1): 35–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez M, E. Rice, J. Stein, N. Milburn, and M. J. Rotheram-Borus. 2010. “Acculturation, Coping Styles, and Health Risk Behaviors among HIV Positive Latinas.” AIDS and Behavior 14 (2): 401–409.. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9618-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, and Szapocznik J. 2010. “Rethinking the Concept of Acculturation: Implications for Theory and Research.” American Psychologist 65 (4): 237–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S, Weisskirch R, Zamboanga B, Castillo L, Ham L, Huynh Q, Park I, Donovan R, Kim SY, and Vernon M. 2011. “Dimensions of Acculturation: Associations with Health Risk Behaviors among College Students from Immigrant Families.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 58 (1): 27–41. doi: 10.1037/a0021356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soler H, Quadagno D, Sly DF, Riehman KS, Eberstein IW, and Harrison DF. 2000. “Relationship Dynamics, Ethnicity and Condom Use among Low-income Women.” Family Planning Perspectives 32 (2): 82–88. 101. doi: 10.2307/2648216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syvertsen JL, A. R. Bazzi, G. Martinez, et al. 2015. “Love, Trust, and HIV Risk Among Female Sex Workers and Their Intimate Male Partners.” American Journal of Public Health 105 (8): 1667–1674.. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villarruel A, Jemmott J, Jemmott L, and Ronis D. 2007. “Predicting Condom Use among Sexually Experienced Latino Adolescents.” Western Journal of Nursing Research 29 (6): 724–738. doi: 10.1177/0193945907303102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace P, Pomery E, Latimer A, Martinez J, and Salovey P. 2009. “A Review of Acculturation Measures and their Utility in Studies Promoting Latino Health.” Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 32 (1): 37–54. doi: 10.1177/0739986309352341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingood G, and DiClemente R. 2000. “Application of the Theory of Gender and Power to Examine HIV-related Exposures, Risk Factors, and Effective Interventions for Women.” Health Education & Behavior 27 (5): 539–565. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]