Abstract

For gene therapy of gain-of-function autosomal dominant diseases, either correcting or deleting the disease allele is potentially curative. To test whether there may be an advantage of one approach over the other for WHIM (warts, hypogammaglobulinemia, infections, and myelokathexis) syndrome — a primary immunodeficiency disorder caused by gain-of-function autosomal dominant mutations in chemokine receptor CXCR4 — we performed competitive transplantation experiments using both lethally irradiated WT (Cxcr4+/+) and unconditioned WHIM (Cxcr4+/w) recipient mice. In both models, hematopoietic reconstitution was markedly superior using BM cells from donors hemizygous for Cxcr4 (Cxcr4+/o) compared with BM cells from Cxcr4+/+ donors. Remarkably, only approximately 6% Cxcr4+/o hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) chimerism after transplantation in unconditioned Cxcr4+/w recipient BM supported more than 70% long-term donor myeloid chimerism in blood and corrected myeloid cell deficiency in blood. Donor Cxcr4+/o HSCs differentiated normally and did not undergo exhaustion as late as 465 days after transplantation. Thus, disease allele deletion resulting in Cxcr4 haploinsufficiency was superior to disease allele repair in a mouse model of gene therapy for WHIM syndrome, allowing correction of leukopenia without recipient conditioning.

Keywords: Immunology, Stem cells

Keywords: Bone marrow transplantation, Chemokines, Hematopoietic stem cells

Introduction

WHIM (warts, hypogammaglobulinemia, infections, and myelokathexis) syndrome is a rare combined primary immunodeficiency disease caused by gain-of-function autosomal dominant mutations in CXCR4, a G protein–coupled receptor for the chemokine CXCL12 (1, 2). Among other functions, CXCR4 normally promotes BM homing and retention of neutrophils and hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) , as well as HSC quiescence (3–6). The WHIM mutation increases BM retention of neutrophils, causing neutropenia, a hematologic picture referred to as myelokathexis (7–9). G-CSF, which is commonly used to treat neutropenia in patients with WHIM, selectively increases the neutrophil count in part by inducing degradation of CXCL12, thereby reducing CXCR4 signaling (2, 10).

Discovery of CXCR4 as the disease gene in WHIM syndrome has provided a precise target for development of novel therapeutic strategies. Regarding drug development, 2 specific CXCR4 antagonists, plerixafor (Mozobil, Sanofi, AMD3100) and X4P-001 (AMD11070), are currently in clinical trials (11–13). With regard to cure, several patients have been cured by allogeneic BM transplantation (14, 15), and one patient has been cured by spontaneous deletion of the WHIM allele in a single HSC by chromothripsis (chromosome shattering). Remarkably, the chromothriptic HSC in this patient acquired a selective growth advantage leading to approximately 100% chimerism with CXCR4-haploinsufficient (CXCR4+/o) myeloid cells (16). The genetic mechanism responsible for myeloid repopulation remains undefined, in large part because 163 other genes were also deleted by the chromothriptic event. Nevertheless, a potential contribution from CXCR4 haploinsufficiency alone is supported by a mouse model of the patient in which the haploinsufficient (Cxcr4+/o) genotype conferred a strong long-term engraftment advantage over both WHIM (Cxcr4+/w) and WT (Cxcr4+/+) genotypes after competitive BM transplantation in lethally irradiated congenic recipient mice (16).

Importantly, cure of these patients demonstrates that the hematologic phenotypes and infection susceptibility in WHIM syndrome are driven by expression of the WHIM allele in hematopoietic cells, which suggests that both correcting and deleting the disease allele in patient HSCs are rational curative gene therapy strategies. The Cxcr4+/o/Cxcr4+/+ competitive BM transplantation experiments in lethally irradiated mice suggested that disease allele deletion may actually be superior to disease allele correction as a gene therapy strategy because of the potential for enhanced engraftment of Cxcr4+/o HSCs. Here we test this hypothesis directly in mouse models of gene therapy for WHIM syndrome.

Results and Discussion

Cxcr4 genotype is a major determinant of hematopoietic reconstitution during competitive BM transplantation in lethally irradiated mice.

We first conducted competitive transplantation experiments with lethally irradiated WT (Cxcr4+/+) recipient mice and 1:1 BM mixtures from all 3 possible pairings of congenic donor mice distinguished by the following Cxcr4 genotypes: Cxcr4+/+, Cxcr4+/o (Cxcr4 hemizygous/haploinsufficient), and Cxcr4+/w (WHIM model mice). The Cxcr4+/o/Cxcr4+/+ and Cxcr4+/o/Cxcr4+/w competitions confirmed our previously published results (16) and are included as contemporaneous comparators for the Cxcr4+/+/Cxcr4+/w competition, which has not been previously tested. In all 3 competitions, recipient blood reconstitution with donor-derived leukocytes was strongly polarized with the rank order Cxcr4+/o, which is greater than Cxcr4+/+, which is greater than Cxcr4+/w (Figure 1A and Supplemental Figure 1A; supplemental material available online with this article; https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI120375DS1). The rank order was stable out to 300 days, HSC intrinsic (Figure 1B, Supplemental Figure 1B, and Supplemental Figure 2), and independent of the CD45 genetic background of the donor mice (Supplemental Figure 3).

Figure 1. The Cxcr4 genotype rank order for peripheral blood reconstitution after competitive BM transplantation in lethally irradiated mice is Cxcr4+/o, which is greater than Cxcr4+/+, which is greater than Cxcr4+/w.

(A and B) Donor-derived leukocyte frequencies after transplantation with total BM cells (A) or FACS-purified Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+CD48–CD34–CD150+ HSCs (B). Experiment design is shown on the left of each row of graphs. Data are the percentage (mean ± SEM) of total donor-derived cells for each subset indicated. See Supplemental Figure 1, A and B, for representative flow cytometry plots and transplantation conditions. (C) Donor-derived absolute leukocyte counts after competitive BM transplantation. Experiment design is shown on the left. Data are absolute numbers of donor-derived cells per milliliter (mean ± SEM) of the subset indicated. The average absolute blood counts of naive Cxcr4+/+ (black dashed lines, n = 58) and Cxcr4+/w (blue dotted lines, n = 38) mice from our colony are also presented. Each recipient was transplanted with 5 million BM cells (A and C) or 2,000 HSCs (B). For all conditions, n was at least 5 mice. SEM was less than 5% of the mean at all time points lacking visible error bars. Results were verified in 3 additional independent experiments for A. +/o, +/+, and +/w denote Cxcr4+/o, Cxcr4+/+, and Cxcr4+/w donors, respectively. P values, 2-way ANOVA.

For the Cxcr4+/o/Cxcr4+/w competition, the absolute numbers of Cxcr4+/o donor-derived mature leukocytes rapidly increased to the average value for each subset for Cxcr4+/+ mice, whereas the absolute numbers of Cxcr4+/w donor-derived mature leukocytes remained below the average value for Cxcr4+/w mice (Figure 1C). In contrast, when each donor BM was transplanted independently into lethally irradiated Cxcr4+/+ recipients, the steady state absolute numbers of donor-derived peripheral blood leukocytes in the recipients consistently tracked the average values for the corresponding subset in donor mice (Supplemental Figure 4). Thus, the results identify competitive suppression of Cxcr4+/w leukocyte reconstitution in peripheral blood by Cxcr4+/o hematopoiesis in the same mouse.

The superiority of Cxcr4+/o BM for reconstituting peripheral blood leukocytes after competitive transplantation in lethally irradiated mice involves an early HSC proliferative advantage and superior long-term HSC engraftment.

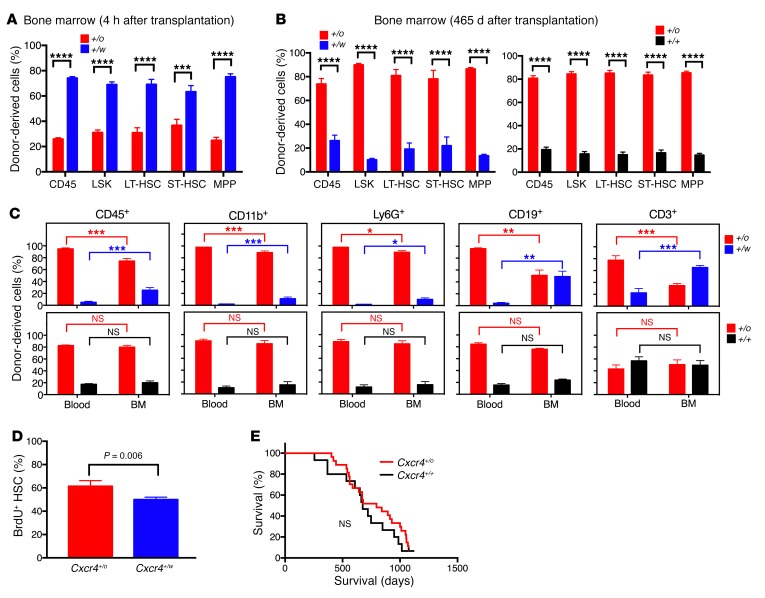

We next evaluated potential mechanisms for the hematopoietic reconstitution rank order conferred by Cxcr4 genotype. We first tested HSC homing to BM, which is known to be mediated by CXCR4 (7, 17). Consistent with this, 4 hours after a 50:50 mixture of Cxcr4+/o and Cxcr4+/w lineage-negative BM cells was coinjected into lethally irradiated mice, Cxcr4+/w HSCs and hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) outnumbered Cxcr4+/o HSCs and HPCs in the BM by an approximately 4:1 margin (Figure 2A). However, this ratio was inverted when BM was analyzed 465 days after competitive transplantation, aligning with the Cxcr4 genotype rank order for blood reconstitution by mature donor-derived leukocytes in the same animals (Figure 2B). This provides evidence for a posthoming BM engraftment advantage conferred by Cxcr4 haploinsufficiency to transplanted HSCs.

Figure 2. The superiority of Cxcr4+/o BM for blood reconstitution after competitive transplantation in lethally irradiated mice involves an early HSC proliferative advantage and superior long-term engraftment, but not an HSC BM-homing advantage.

(A) Homing. Equal numbers of Cxcr4+/o and Cxcr4+/w lineage-negative BM cells were cotransplanted into lethally irradiated mice. Four hours later, the recipient BM was analyzed for donor-derived cells. (B) Long-term engraftment of HSCs and HPCs. (C) Mature leukocyte retention. Blood and BM cells of the mice in Figure 1B were analyzed on day 465 after transplantation. Data (n = 5) are the percentage (mean ± SEM) of total donor-derived cells specific for the indicated Cxcr4 genotype (abbreviated as +/o, +/+, and +/w) for the indicated HSCs and HPCs (A and B) and mature leukocytes (C) from individual experiments and are representative of 2 independent experiments in A–C. (D) HSC proliferation (see Supplemental Figure 5 for details). Data (n = 5) are the percentage (mean ± SEM) of BrdU+ HSCs for each donor from a single experiment representative of 2 independent experiments. (E) Survival. Cxcr4+/+ (n = 15) and Cxcr4+/o (n = 27) littermates were observed in specific pathogen-free conditions. Lin–, lineage-negative leukocytes; LT-HSC, long-term engrafting HSCs; ST-HSC, short-term engrafting HSCs; LSK, lin–Sca1+c-kit–; MPP, multipotent progenitors. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005; **** P < 0.001; NS, not significant, Student’s t test.

CXCR4 is also known to mediate retention of HSCs and neutrophils in BM (4, 18). Thus, biased BM retention of mature Cxcr4+/w leukocytes must be considered as a potential explanation for the blood results. We found no evidence for this in the Cxcr4+/o/Cxcr4+/+ competition (Figure 2C). However, in the Cxcr4+/o/Cxcr4+/w competition, we observed significantly higher frequencies of mature Cxcr4+/w leukocytes, especially B and T cells, in BM than in blood, and conversely, higher frequencies of Cxcr4+/o mature leukocytes in blood than in BM (Figure 2C). Thus, biased BM retention of certain mature leukocytes in this competition may contribute to the net hematopoietic reconstitution activity rank order conferred by Cxcr4 genotype to transplanted BM.

CXCR4 is also known to inhibit cell proliferation (5). Consistent with this, in our previous report we found that Cxcr4+/o HSCs were hyperproliferative compared with Cxcr4+/+ HSCs (16). Likewise, here we found that BrdU+ cell frequency was approximately 20% greater for Cxcr4+/o HSCs than for Cxcr4+/w HSCs 20 hours after BrdU injection 7 days after competitive transplantation (Figure 2D and Supplemental Figure 5). Thus, the superiority of Cxcr4+/o BM for reconstituting peripheral blood leukocytes after competitive transplantation in lethally irradiated mice may involve an early HSC proliferative advantage.

Although enhanced HSC proliferation has been reported to possibly result in HSC exhaustion and depletion, and maintenance of HSCs in quiescence has been reported to favor long-term hematopoiesis (19–21), we did not observe any evidence of BM failure as late as 465 days after competitive transplantation of Cxcr4+/o HSCs (Figure 1B, Figure 2C, and Supplemental Figure 6). Furthermore, in a formal aging study we found no difference in survival and health of Cxcr4+/o mice compared with Cxcr4+/+ littermates (Figure 2E).

Leukopenia can be corrected in WHIM mice by Cxcr4+/o BM transplantation without recipient conditioning.

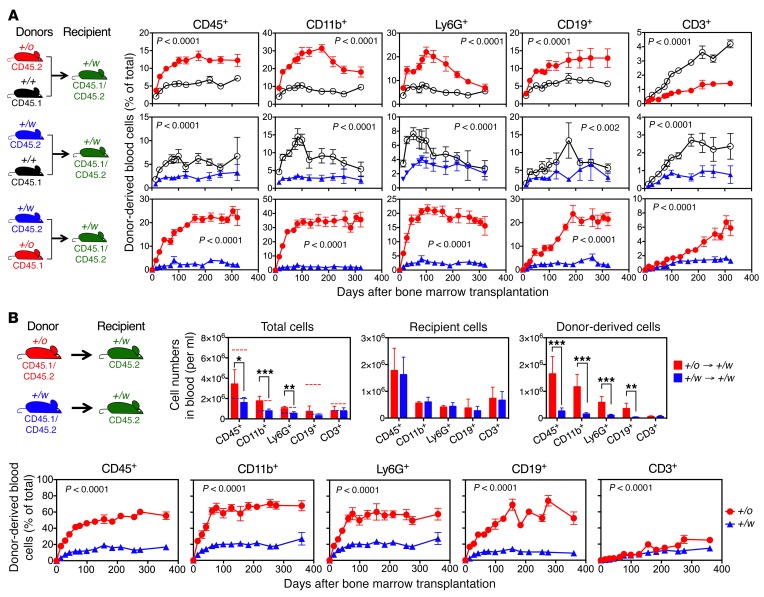

We next tested whether Cxcr4 genotype also affects engraftment after competitive BM transplantation in unconditioned congenic recipient mice. Overall, the Cxcr4 genotype rank order for donor leukocyte reconstitution in peripheral blood was the same as when lethally irradiated Cxcr4+/+mice were tested as the recipients: Cxcr4+/o, which is greater than Cxcr4+/+, which is greater than Cxcr4+/w (compare Figure 1A and Figure 3A). In the Cxcr4+/o/Cxcr4+/w competition, the frequency of differentially marked Cxcr4+/w donor-derived cells was only 1%–4%, whereas the frequencies of donor-derived Cxcr4+/o myeloid and B cells reached a plateau of 20%–40% by 100 days after transplantation that remained stable out to 315 days when the experiment was arbitrarily terminated. Cxcr4+/+ BM also had increased engraftment activity relative to Cxcr4+/w BM, but the difference was only approximately 2-fold and declined toward the end of the experiment for neutrophils and B cells. In the direct Cxcr4+/o/Cxcr4+/+ competition, Cxcr4+/o donor-derived cell frequency for each leukocyte subset in the peripheral blood was approximately 2- to 3-fold greater than for the corresponding Cxcr4+/+ subsets, and this advantage was sustained long-term for CD11b+, CD19+, and CD3+ subsets, but not for neutrophils (Figure 3A). Overall, for each BM donor, myeloid cells reconstituted the best and CD3+ cells the least well.

Figure 3. Correction of myeloid cytopenia in unconditioned WHIM mice by congenic Cxcr4+/o BM transplantation.

(A) Cxcr4+/o BM is superior to Cxcr4+/+ BM for establishing durable hematopoietic chimerism in unconditioned congenic Cxcr4+/w recipients. Experiment design is shown on the left of each row of graphs. Donor-derived cell frequencies for each Cxcr4 genotype are shown for the leukocyte subsets indicated. Data are the percentage (mean ± SEM) of total cells for each subset (n = 5–8 mice per data point). Donor genotypes are abbreviated as +/o, +/+, and +/w. See Supplemental Figure 7 for representative flow cytometry plots and transplantation conditions. (B) Correction of myeloid cytopenia. Noncompetitive transplantation of 5 × 107 total BM cells from Cxcr4+/o (red) or Cxcr4+/w (blue) donor mice to unconditioned Cxcr4+/w recipients. Experiment design is shown on the upper left. The lower panels show donor-derived cell frequencies for the leukocyte subsets indicated, presented as the percentage (mean ± SEM) of total cells for each subset (n = 5 mice per data point). Donor genotypes are abbreviated as +/o and +/w. The upper right 3 panels show leukocyte subset counts of total cells, recipient cells, and donor-derived cells at day 120 after transplantation of unconditioned Cxcr4+/w mice receiving Cxcr4+/o (red) or Cxcr4+/w (blue) BM. Dashed lines indicate average values of blood counts for each subset of naive Cxcr4+/+ (red, n = 58) or Cxcr4+/w (blue, n = 38) mice in our colony. Symbols +/o→+/w and +/w→+/w are the abbreviations of Cxcr4+/w mice receiving Cxcr4+/o BM (red) and Cxcr4+/w mice receiving Cxcr4+/w BM (blue), respectively. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005. Single comparisons, Student’s t test; multiple comparisons, 2-way ANOVA.

Since chimerism in an unconditioned congenic transplantation system is donor BM cell dose–dependent (22), we tested different doses and found that transplantation of 5 × 107 Cxcr4+/o BM cells alone into unconditioned Cxcr4+/w recipients (Figure 3B), which established 60%–70% donor chimerism at steady state for total leukocytes, myeloid cells, and B cells (Figure 3B), restored the absolute myeloid cell counts to the normal range for Cxcr4+/+ mice (Figure 3B). In contrast, transplantation of 5 × 107 Cxcr4+/w BM cells alone resulted in no greater than 15% Cxcr4+/w donor-derived CD45+ cells in peripheral blood (Figure 3B), and did not significantly increase the absolute cell number (Figure 3B).

Low-level Cxcr4+/o HSC and HPC engraftment is sufficient to correct leukopenia in unconditioned WHIM mice.

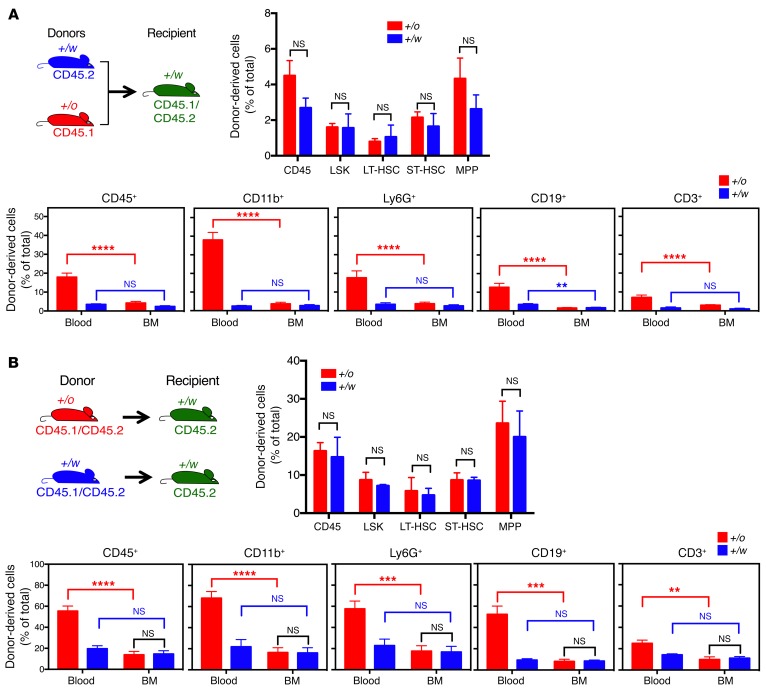

At termination, 385 days after cotransplantation of unconditioned Cxcr4+/w recipients with 107 Cxcr4+/o and 107 Cxcr4+/w donor BM cells (time course described in Figure 3A), the frequencies of mature Cxcr4+/w donor-derived leukocytes were very low and similar for each subset in BM and peripheral blood (Figure 4A). The BM frequencies of Cxcr4+/w donor-derived HSCs and HPCs were also very low (Figure 4A). In contrast, the frequencies of mature Cxcr4+/o donor-derived leukocytes were much higher in peripheral blood for each subset than in BM (Figure 4A). Surprisingly, the frequencies of Cxcr4+/o donor-derived HSCs and HPCs in BM were also low and similar to the frequencies of Cxcr4+/w donor-derived HSCs and HPCs in BM (Figure 4A). The same pattern of results was obtained when unconditioned Cxcr4+/w recipients underwent transplantation separately with 5 × 107 BM cells from either Cxcr4+/o or Cxcr4+/w donors (time course described in Figure 3B), and were analyzed 348 days after transplantation (Figure 4B). These data are consistent with a BM egress advantage for donor-derived mature leukocytes conferred by Cxcr4 haploinsufficiency over the Cxcr4+/w genotype.

Figure 4. Low-level Cxcr4+/o HSC engraftment after BM transplantation is sufficient to correct leukopenia in unconditioned WHIM mice.

(A) Competitive model. BM cells (107) from each of the indicated donors were mixed (final donor BM cell ratio was 47:53, Cxcr4+/o/Cxcr4+/w, Supplemental Figure 7) and transplanted into each unconditioned Cxcr4+/w mouse. Experiment design is shown on the upper left. Recipient mice were euthanized on day 385 after transplantation for mature leukocyte subset analysis in blood and BM, and HSC and HPC analysis in BM. (B) Noncompetitive model. Total BM cells (5 × 107) from each of the indicated donors were transplanted separately into unconditioned Cxcr4+/w mice. Experiment design is shown on the upper left. Mice were euthanized on day 348 after transplantation for mature leukocyte subset analysis in blood and BM, and HSC and HPC analysis in BM. For both A and B, data are the percentage (mean ± SEM) of total cells contributed by the indicated donor (Cxcr4 genotype abbreviated as +/o or +/w) for each indicated HSC/HPC subset in BM and mature leukocyte subset in BM and blood (n = 5 mice per data point). **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005; ****P < 0.001, Student’s t test. NS, not significant.

Taken together, our results provide evidence in 2 transplantation models that WHIM allele silencing, as represented by the Cxcr4+/o genotype, is superior to WHIM allele correction, as represented by the Cxcr4+/+ genotype, as a cure strategy in a mouse model of WHIM syndrome. Importantly, transplantation of Cxcr4+/o BM, but not Cxcr4+/w BM, in unconditioned Cxcr4+/w recipients corrected myeloid cell deficiency in the blood, a major phenotype in WHIM syndrome that predisposes patients to bacterial infections. Even low levels of donor Cxcr4+/o LT-HSCs (~6% of total HSCs) in the BM of unconditioned Cxcr4+/w mice after transplantation resulted in correction of the blood.

In lethally irradiated recipients, the major mechanism involves markedly enhanced BM engraftment of Cxcr4+/o HSCs. This was associated with early enhanced Cxcr4+/o HSC proliferation, which may overcome the BM homing disadvantage of these cells relative to Cxcr4+/w HSCs. The proliferation data in the lethally irradiated recipient transplantation model are consistent with previous reports indicating that WT CXCR4 negatively regulates HSC proliferation (5). At steady state in the model, the great majority of myeloid cells are from the Cxcr4+/o BM donor in both recipient BM and blood, suggesting that differential retention of mature donor-derived Cxcr4+/o versus Cxcr4+/w leukocytes in the BM plays little if any role in explaining the almost complete reconstitution of the blood with Cxcr4+/o myeloid cells. In contrast, differential BM retention of lymphoid cells may contribute substantially to the predominance of Cxcr4+/o lymphoid cells in the blood.

The quite different BM results in the 2 transplantation models tested here suggest that the increased proliferative potential of Cxcr4+/o HSCs over Cxcr4+/w HSCs may only become manifest when stem cell niches are present in great excess over available donor HSCs or when it is needed for an immune response. The number of HSCs in BM is thought to be limited by the total number of specific niches available (5, 23). We speculate that in the lethally irradiated recipient model, the proliferative advantage of Cxcr4+/o HSCs is not limited by niche availability. In contrast, in unconditioned WHIM mice, most niches are already occupied. Therefore, HSC engraftment is limited regardless of the Cxcr4 genotype. In unconditioned Cxcr4+/w recipients, leukopenia may stimulate production of mature leukocytes from both Cxcr4+/w and Cxcr4+/o HSCs. However, differential HSC proliferation and mature myeloid cell egress from BM may provide the selective mechanism for restoring the peripheral myeloid cell counts to normal with donor-derived Cxcr4+/o but not Cxcr4+/w cells. A limitation of this interpretation is that it is difficult to directly evaluate donor-derived HSC proliferation in vivo in unconditioned recipients due to the paucity of these cells in BM and the slow time course of engraftment.

Importantly, we found that reconstitution of unconditioned WHIM mice with Cxcr4+/o leukocytes was durable after BM transplantation, and that survival in mice with a single copy of Cxcr4 in their hematopoietic cells is normal. Although our results are not consistent with CXCR4 haploinsufficiency being the sole genetic explanation for the patient with WHIM who was cured by chromothripsis (16), they do suggest that CXCR4 haploinsufficiency may have contributed. The patient is also haploinsufficient for 163 other genes, so many other possible genetic mechanisms must be considered. Nevertheless, our results support further development of a cure strategy for WHIM syndrome focused on syngeneic transplantation of patient HSCs in which the WHIM allele has been deleted by gene editing and patient conditioning is limited or even unnecessary.

Methods

Detailed methods are described in the Supplemental Methods online.

Statistics.

All data are presented as mean ± SEM. The 2-tailed Student’s t test was used for single comparisons and 2-way ANOVA was used for multiple comparisons. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Study approval.

All animal experiments were approved by the IACUC of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Author contributions

JLG, DHM, and PMM designed the experiments. JLG, EY, MS, AY, QL, AA, and AOA generated and analyzed the data, with supervision and analysis by JLG, DHM, and PMM. JG and PMM wrote the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

WHIM mice were provided by Francoise Bachelerie and Karl Balabanian (INSERM UMRS-996, Universite Paris Sud). This work was supported by the Division of Intramural Research of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH.

Version 1. 05/01/2018

In-Press Preview

Version 2. 06/25/2018

Electronic publication

Version 3. 08/01/2018

Print issue publication

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: JG, MS, EY, QL, DHM, and PMM are listed as inventors on USA patent application 20170196911.

Reference information: J Clin Invest. 2018;128(8):3312–3318.https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI120375.

See the related Commentary at Enhancement of stem cell engraftment on a WHIM.

Contributor Information

Ji-Liang Gao, Email: JGAO@niaid.nih.gov.

Erin Yim, Email: erinyim92@gmail.com.

Marie Siwicki, Email: marie.siwicki@gmail.com.

Alexander Yang, Email: alexander.yang@nih.gov.

Qian Liu, Email: liujoy@niaid.nih.gov.

Ari Azani, Email: ariazani@gmail.com.

Albert Owusu-Ansah, Email: albert.owusu-ansah@nih.gov.

David H. McDermott, Email: dmcdermott@niaid.nih.gov.

Philip M. Murphy, Email: pmm@nih.gov.

References

- 1.Hernandez PA, et al. Mutations in the chemokine receptor gene CXCR4 are associated with WHIM syndrome, a combined immunodeficiency disease. Nat Genet. 2003;34(1):70–74. doi: 10.1038/ng1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heusinkveld LE, et al. Pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapeutic strategies in WHIM syndrome immunodeficiency. Expert Opin Orphan Drugs. 2017;5(10):813–825. doi: 10.1080/21678707.2017.1375403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dar A, Kollet O, Lapidot T. Mutual, reciprocal SDF-1/CXCR4 interactions between hematopoietic and bone marrow stromal cells regulate human stem cell migration and development in NOD/SCID chimeric mice. Exp Hematol. 2006;34(8):967–975. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broxmeyer HE, et al. Rapid mobilization of murine and human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells with AMD3100, a CXCR4 antagonist. J Exp Med. 2005;201(8):1307–1318. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nie Y, Han YC, Zou YR. CXCR4 is required for the quiescence of primitive hematopoietic cells. J Exp Med. 2008;205(4):777–783. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sugiyama T, Kohara H, Noda M, Nagasawa T. Maintenance of the hematopoietic stem cell pool by CXCL12-CXCR4 chemokine signaling in bone marrow stromal cell niches. Immunity. 2006;25(6):977–988. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawai T, et al. WHIM syndrome myelokathexis reproduced in the NOD/SCID mouse xenotransplant model engrafted with healthy human stem cells transduced with C-terminus-truncated CXCR4. Blood. 2007;109(1):78–84. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-025296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorlin RJ, Gelb B, Diaz GA, Lofsness KG, Pittelkow MR, Fenyk JR. WHIM syndrome, an autosomal dominant disorder: clinical, hematological, and molecular studies. Am J Med Genet. 2000;91(5):368–376. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(20000424)91:5<368::AID-AJMG10>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDermott DH, et al. AMD3100 is a potent antagonist at CXCR4(R334X), a hyperfunctional mutant chemokine receptor and cause of WHIM syndrome. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15(10):2071–2081. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01210.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furze RC, Rankin SM. Neutrophil mobilization and clearance in the bone marrow. Immunology. 2008;125(3):281–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02950.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDermott DH, et al. A phase 1 clinical trial of long-term, low-dose treatment of WHIM syndrome with the CXCR4 antagonist plerixafor. Blood. 2014;123(15):2308–2316. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-09-527226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dale DC, et al. The CXCR4 antagonist plerixafor is a potential therapy for myelokathexis, WHIM syndrome. Blood. 2011;118(18):4963–4966. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-360586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDermott DH, et al. The CXCR4 antagonist plerixafor corrects panleukopenia in patients with WHIM syndrome. Blood. 2011;118(18):4957–4962. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-368084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moens L, et al. Successful hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for myelofibrosis in an adult with warts-hypogammaglobulinemia-immunodeficiency-myelokathexis syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(5):1485–1489.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krivan G, et al. Successful umbilical cord blood stem cell transplantation in a child with WHIM syndrome. Eur J Haematol. 2010;84(3):274–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2009.01368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDermott DH, et al. Chromothriptic cure of WHIM syndrome. Cell. 2015;160(4):686–699. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lapidot T, Kollet O. The essential roles of the chemokine SDF-1 and its receptor CXCR4 in human stem cell homing and repopulation of transplanted immune-deficient NOD/SCID and NOD/SCID/B2m(null) mice. Leukemia. 2002;16(10):1992–2003. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eash KJ, Greenbaum AM, Gopalan PK, Link DC. CXCR2 and CXCR4 antagonistically regulate neutrophil trafficking from murine bone marrow. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(7):2423–2431. doi: 10.1172/JCI41649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson A, et al. Hematopoietic stem cells reversibly switch from dormancy to self-renewal during homeostasis and repair. Cell. 2008;135(6):1118–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y, et al. CXCR4/CXCL12 axis counteracts hematopoietic stem cell exhaustion through selective protection against oxidative stress. Sci Rep. 2016;6:37827. doi: 10.1038/srep37827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugimura R, et al. Noncanonical Wnt signaling maintains hematopoietic stem cells in the niche. Cell. 2012;150(2):351–365. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Westerhuis G, van Pel M, Toes RE, Staal FJ, Fibbe WE. Chimerism levels after stem cell transplantation are primarily determined by the ratio of donor to host stem cells. Blood. 2011;117(16):4400–4401. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-328518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Busch K, et al. Fundamental properties of unperturbed haematopoiesis from stem cells in vivo. Nature. 2015;518(7540):542–546. doi: 10.1038/nature14242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.