SUMMARY

The ability to target the Cas9 nuclease to DNA sequences via Watson-Crick base pairing with a single guide RNA (sgRNA) has provided a dynamic tool for genome editing and an essential component of adaptive immune systems in bacteria. After generating a double strand break n(DSB), Cas9 remains stably bound to the DNA. Here we show persistent Cas9 binding blocks access to the DSB by repair enzymes, reducing genome editing efficiency. Cas9 can be dislodged by translocating RNA polymerases, but only if the polymerase approaches from one direction towards the Cas9-DSB complex. By exploiting these RNA polymerase-Cas9 interactions, Cas9 can be conditionally converted into a multi-turnover nuclease, mediating increased mutagenesis frequencies in mammalian cells and enhancing bacterial immunity to bacteriophages. These consequences of a stable Cas9-DSB complex provide insights into the evolution of PAM sequences and a simple method of improving selection of highly active sgRNA for genome editing.

eTOC blurb

Clarke et al show that persistent DNA binding of Cas9 precludes repair of DNA breaks. Translocating RNA polymerases can dislodge Cas9 from DNA, but only in a highly strand-biased manner. This effect is suggested to mediate strand-biased increases in genome editing efficiency in mammalian cells and CRISPR immunity bacteria.

INTRODUCTION

The clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) system provides bacteria and archaebacteria an adaptive immune system (Barrangou and Marraffini, 2014). In type II CRISPR systems, immunity begins during the adaptation phase wherein foreign DNA elements near the system’s protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence are recognized, then processed and inserted as the spacers into the CRISPR locus (Barrangou et al., 2007; Garneau et al., 2010; Heler et al., 2015). The immunization phase then begins through expression of the CRISPR loci, and is characterized by spacer transcripts being processed into crRNA (Deltcheva et al., 2011). The crRNA direct Cas9 nuclease activity to foreign DNA by forming a ribonucleoprotein complex with Cas9 and tracrRNA, and using the crRNA sequence to identify targets (Jinek et al., 2012). The PAM is an important component that prevents Cas9 from cutting the spacer sequence in its own genome by enabling nuclease activity only when the crRNA target sequence is adjacent to the short DNA sequence also used during the capture of spacers from the foreign DNA (Heler et al., 2015). For repurposing Cas9 to edit gigabase sized genomes, Watson-Crick base pairing of the 5′ 20bp of a single guide RNA (sgRNA) has provided sufficient specificity for widespread use of S. pyogenes Cas9 (spCas9) in editing various genomes, including those of mammals (Hsu et al., 2013; Jinek et al., 2013; Mali et al., 2013).

The basic biochemical and biophysical characteristics of spCas9 have been elucidated and exploited for genome editing. The ability to target a single site within the genome without off-target effects has been the focus of considerable research effort (Chen et al., 2017; Kleinstiver et al., 2016; Slaymaker et al., 2016). The relatively minor restrictions the PAM places on genomic sites that can be targeted, and the ease of targeting Cas9 by expressing a short sgRNA have combined to support widespread and pervasive use of Cas9 for genome editing (Barrangou and Doudna, 2016).

In addition to the biochemical properties of Cas9 that provide its target specificity, the nuclease displays other unique properties that distinguish it from non-RNA-guided effector nucleases of bacterial immune systems, such as restriction endonucleases. In contrast to other endonucleases, Cas9 exhibits a remarkably stable enzyme-product state wherein the nuclease remains bound to the double strand break (DSB) it generates (Jinek et al., 2014; Nishimasu et al., 2014; Richardson et al., 2016). The Cas9-DSB state has been shown to persist in vitro for ~5.5 hrs (Richardson et al., 2016). Nuclease dead Cas9 (dCas9) and active Cas9 display the same slow off-rate in vitro (Richardson et al., 2016). Recent characterization of dCas9 in E. coli reported stable binding to target DNA until DNA replication occurs (Jones et al., 2017). Although persistence of Cas9 binding for hour-long periods has not been examined in mammalian cells, fluorescence recovery after photobleaching and single molecule fluorescence studies demonstrated persistence of dCas9 binding during minute-long observations (Knight et al., 2015). Thus the slow off-rate appears to affect Cas9 functionality in vitro and in vivo.

In contrast to the rapid characterization for how Cas9 targets DNA, the consequences of the persistent enzyme-product state are not understood. The single-turnover characteristic could limit Cas9’s effectiveness when DNA substrates are abundant, such as during phage infection. When DNA substrates are rare, such as when Cas9 is used to edit a unique mammalian genomic sequence, persistence of Cas9-DSB could preclude repair of the DSB by the cell. To date, experimental techniques to manipulate the kinetics of Cas9 dissociation from the DSB have been limited, which has prevented direct analysis of the consequences of the highly stable enzyme-product complex.

In this study, we show that the Cas9-DSB complex can be disrupted by RNA polymerase transcription activity through the Cas9 target site, but only if the sgRNA of Cas9 is annealed to the DNA strand used as the template by the RNA polymerase. The profound difference caused by the direction of the translocating RNA polymerase enabled examination of the effects of the persistent Cas9-DSB state. Dislodging Cas9 from the DSB stimulates editing efficiency in cells by allowing the ends of the DSB to be accessed by DNA repair machinery. This mechanism causes sgRNA to be more effective if they anneal to the template DNA strand of transcribed genes and also increases the immunity mediated by crRNA that anneal to the template strand of bacteriophage genomes through RNA polymerase mediated multi-turnover Cas9 nuclease activity. These data provide insights into the biology of the CRISPR system and provide a simple method of enhancing probability of successful genome editing by choosing sgRNA that anneal to the template strand of DNA.

RESULTS

Active transcription through Cas9 target sites increases genome editing frequencies

Several genomic factors that affect genome editing frequencies have been identified with previous studies, including nucleosome occupancy, DNase hyper-sensitive sites (DHSS), and histone marks (H3K4me3) associated with active transcription (Chari et al., 2015; Horlbeck et al., 2016). To complement these findings using a distinct approach, we focused on being able to detect a large range of mutation frequencies as a way to identify genomic variables affecting Cas9-mediated mutagenesis. We examined a collection of 40 sgRNA, each targeting the coding sequence in a different gene (Table S1). Transient transfections were used to express Cas9 and an sgRNA in mouse ES cells, then genomic DNA was isolated four days after transfection, and indels were measured by targeted deep sequencing of each genomic target site. Analysis of these 40 sgRNA target sites revealed a wide range of indel frequencies, from 1.5% to 53.7% (Fig. 1A, Table S1). Most sgRNA (33 of 40) displayed a similar and high mutagenesis activity (>30% indel formation). Unexpectedly, the distribution of mutation frequencies was distinctly bimodal, with seven of the 40 displaying substantially lower activity that separated them from the majority of sgRNA (Fig 1A). Interestingly, six of the seven poorly performing sgRNA annealed to the DNA strand that was not used by RNA Pol II as the template for transcription, i.e. the non-template strand (Fig 1B,C, Table S1). The seventh annealed to the template strand of a gene (Actbl2) that was not expressed in ES cells (Fig 1B,C, Table S1). For simplicity, sgRNA that anneal to the non-template strand of a transcribed DNA will hereafter be referred to as “non-template sgRNA”, and those that anneal to the template strand of a transcribed DNA will be referred to as “template sgRNA” (Fig 1C).

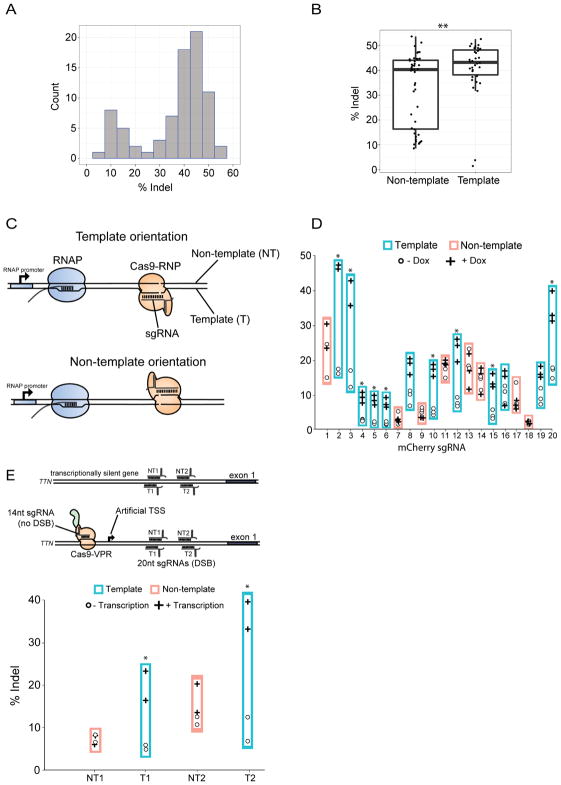

Figure 1. Transcription mediated displacement of Cas9 from the DSB increases genome editing frequencies and is strand dependent.

A, Bimodal distribution of indel frequencies of 40 distinct mouse genes four days after transient transfection of Cas9 and sgRNA expression plasmids. Individual observations from biological duplicates for each sgRNA were binned according to their mutation frequencies (% indel), and the number of sgRNA that fell into each bin is displayed (count). See also Table S1.

B, Indel frequencies associated with the 40 sgRNA in (A) were separated by whether the sgRNA annealed to the DNA strand used as the template for transcription by RNA polymerase II (RNAP), or the non-template DNA strand. There are 17 template strand and 23 non-template sgRNA. Each point represents a mutation frequency of independent transfections, n=2 for each sgRNA. **p < 0.01.

C, Schematic illustrating orientation of Cas9, target DNA, and an approaching RNAP for the two possible RNAP and Cas9 collision orientations: with a template sgRNA and non-template sgRNA.

D, Mutagenesis frequencies mediated by 20 different sgRNA targeting a genomic mCherry measured by T7E1 assays (see also Fig S2E). mCherry transcription is controlled by doxycycline (dox) (see Fig S2D). Plusses (+dox/mCherry expression) and cirlces (−dox/no mCherry expression) represent individual biological replicates testing the effect of transcription on mutagenesis levels mediated by each sgRNA. Genomic DNA was isolated 48h after transfection. *p<0.05.

E, The strand bias was tested at a silent endogenous gene through synthetically activating transcription of the human TTN gene using Cas9-VPR construct. Nuclease active Cas9-VPR was targeted to activate transcription but not introduce DSBs through using a 14nt sgRNA. Simultaneously, a 20nt sgRNA targeted to either the template or non-template strand was provided to drive transcription mediated by 14nt-Cas9-VPR through Cas9 cleavage sites. Genomic DNA was harvest 48h after transfected and mutation frequencies were analyzed via T7E1 assays. Each point represents a biological replicate.

To assess the correlation between transcription and indel mutagenesis with additional sgRNA, the large dataset from Chari et al was re-examined. The relationship between indel formation and template/non-template status of sgRNA was tested. Transcription through each targeted site was evaluated by RNA-seq FPKM levels from the same cell line (Fig S1A)(Chavez et al., 2015). Each target gene and its corresponding sgRNA were binned into quartiles based on FPKM values. High levels of gene transcription positively correlated with higher mutation frequency, with a significant ~2 fold difference between quartiles 1 and 4 (Fig S1B, left). This effect from transcription appeared to be caused by increased efficiency from template strand sgRNA (Fig S1B, middle), because transcription levels did not generate statistically significant differences among the bins of non-template sgRNA (Fig S1B, right).

To directly test the effects of transcription through the Cas9 target site, we used a mouse ES cell line harboring a doxycycline (dox) inducible mCherry gene (Fig S1D). Twenty sgRNA (12 template, 8 non-template) targeting the mCherry gene were first assessed for their ability to stimulate Cas9 digestion of DNA in in vitro reactions by generating each RNA individually then digesting an mCherry containing plasmid. (Fig S1C). All sgRNA were able to stimulate DSB formation in vitro, although five (#5, 11, 12, 14, and 16) required higher concentrations of Cas9 than the other 15 sgRNA (Fig S1C). Mutagenesis frequencies mediated by the 20 sgRNA in vivo were measured by T7 endonuclease 1 (T7E1) activities on PCR products generated from genomic DNA isolated two days after transfection (Fig. S1E). Without dox-induced transcription of mCherry, the 20 sgRNA displayed a range of indel formation (3%–21%), and the ranges of indel frequencies derived from template sgRNA were not significantly different than non-template sgRNA (Fig. 1D, S1E). Stimulating mCherry transcription with dox following transfection did not significantly affect mutagenesis mediated by any of the non-template sgRNA (Fig 1D). By contrast, mutagenesis by 9 of 12 template-strand sgRNA was significantly increased by transcription through the target site (Fig. 1D). The stimulation of mutagenesis caused by transcriptional activity was substantial (2–3 fold) for those sgRNA that were affected.

The transcription-dependent template-strand effect on genome editing was tested on an endogenous gene in HEK293 cells by controlling the level of expression with a CRISPR-activation system. The system uses a truncated sgRNA using only 14 nucleotides to target a nuclease active Cas9-VPR fusion protein to the TTN gene as previously described (Kiani et al., 2015). The truncated sgRNA is sufficient to stimulate transcription of TTN (Fig. S1F), but it does not stimulate significant mutagenesis at that site (Kiani et al., 2015; Liao et al., 2017). The system enabled concomitant targeting of Cas9 nuclease by co-transfection with full length sgRNA, which were used to target sequences downstream of the transcriptional start site (Fig 1E). In the absence of the 14nt sgRNA stimulating TTN transcription, the template and non-template sgRNA displayed similar levels of indel mutagenesis (Fig. 1E, S1G). Upon stimulation of TTN transcription with addition of the 14nt sgRNA, indel frequency was stimulated by 2.5 to 4 fold for template sgRNA but not for non-template sgRNA (Fig 1E, S1G).

Together, these results show that transcription through a Cas9 target site can stimulate mutagenesis in cells, provided the sgRNA anneals to the DNA strand that serves as the template for the RNA polymerase. We suggest that the transcription-mediated stimulation of mutagenesis prevents template sgRNA from displaying weak indel mutagenesis activity. By contrast, non-template sgRNA are more likely to provide weak activity because they do not benefit from transcription through the target site. Mechanisms underlying this phenomenon are examined below.

Cas9 precludes double stranded break repair enzymes from accessing DNA ends

We tested the possibility that the different mutagenesis frequencies from non-template versus template sgRNA were caused by different levels of DNA repair. To determine if template sgRNA elicited an elevated DNA repair response, multiple sgRNA, either all template or all non-template, were transfected into cells with Cas9. We selected the sgRNA subsets (8 or 4 target genes) from the group of 40 (Table S1) where each of the sgRNA generated >30% indel frequency after five days of expression (Fig 1A,B). Because each of these sgRNA target a single gene and target one of the potential strands, we designed complementary sgRNA that target the other strand for all genes in order to compare strand-biased effects on DNA repair activities generated by Cas9 at the same genes. Twenty four hours after transfection, protein lysates from cells were used for Western blot analysis of phosphorylated histone 2AX, a marker for the cellular response to DNA damage and induction of DNA repair activity. Compared to the no-sgRNA control, the non-template sgRNA pools generated a relatively modest (1.4 to 2.1 fold for 8 and 4 genes respectively) stimulation of H2AX phosphorylation (Fig 2A). The template sgRNA were significantly more effective at stimulating H2AX phosphorylation (2.9 to 7.6 fold for 8 and 4 genes respectively) in cells, suggesting a higher frequency of DNA repair occurring in cells with template sgRNA.

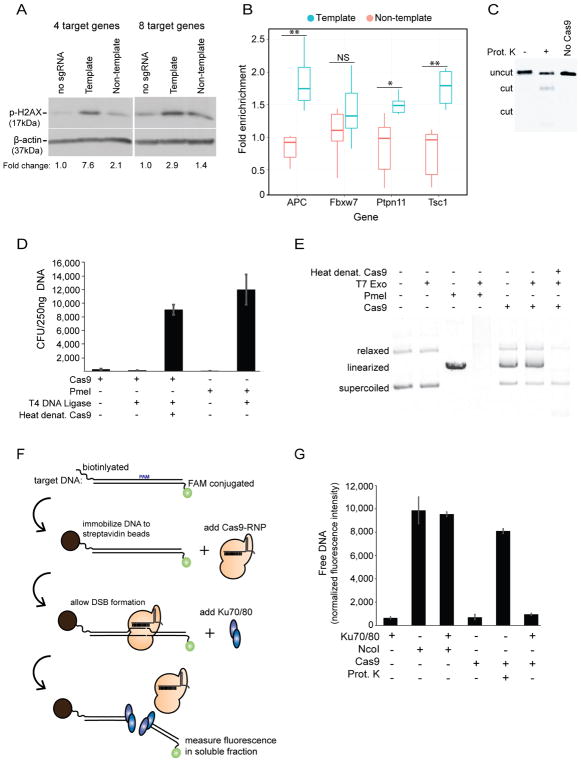

Figure 2. The Cas9-DSB complex precludes DNA repair activities in vitro.

A, Detection of phospo-H2AX levels 24hrs after transfecting mouse ES cells with pools of either template or non-template sgRNAs. sgRNA that mediated >30% indel were selected sgRNA (Fig 1A,B, Table S1). For each sgRNA, a new sgRNA annealing the opposite strand of the same gene was made. To compare strand among the same sets of genes, pools of 4 or 8 sgRNA consisted of the previously characterized and newly generated sgRNA. Western blot analysis was used to determine fold change of phospo-H2AX signal with denistometric measurement of bands and normalization to the loading control (β-actin) and the no sgRNA control. Four target genes: APC, FBXW7, PTPN11, and TSC1. Eight target genes: APC, FBXW7, PTPN11, TSC1, VPS16, VPS54, RAB7, and RANPBP3.

B, Differences in Ku70/80 binding at template or non-template Cas9-generated DSBs was measured by chromatin immunoprecipitation of Ku70/80 bound DNA followed by quantitative PCR (ChIP-qPCR). ChIP DNA was isolated 24 hours after transfection of DNA to express the pool of four sgRNA from (A), DNA precipitated by Ku70/80 antibodies at each target site was measured through qPCR amplifying a sequence adjacent to each Cas9 cleavage site. For each transfected cell population, two biological replicates were harvested, and each was split into three technical replicates prior to immunoprecipitation. Data are expressed as enrichment of the target site compared to the negative control site (Gapdh). **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

C, Agarose gel electrophoresis of an in vitro reaction where linear dsDNA was digested by Cas9 for 30 minutes, then treated with Proteinase K to release the cleaved DNA products.

D, The ability of T4 DNA ligase to repair a Cas9-generated DSB in a circular plasmid DNA was measured through E. coli colony formation on ampicillin-containing plates (CFU) after transformation. Cas9 or restriction endonuclease (PmeI) digestion of plasmid DNA prevented CFU following transformation. T4 DNA ligase activity repaired the DSB and stimulated CFU if plasmid was cut with PmeI, or if Cas9 was denatured at 75C for 10m before addition of ligase. T4 DNA ligase did not stimulate CFU if Cas9 was not denatured. Values represent mean +/− s.d., n=3.

E, Agarose gel analysis of a circular plasmid DNA incubated with T7 exonuclease and the conditions indicated above each lane. PmeI and heat denaturation of Cas9 were as described in (D). Cas9 prevented DNA ends from serving as a substrate for T7 exonuclease unless reactions were heat denatured prior to exonuclease addition. All reactions were treated with Proteinase K before gel loading.

F, Schematic depicting the experiment in (G) to test if Ku70/80 can displace Cas9 from its DSB. The Cas9-DSB complex is formed on target DNA that is biotinylated on one end and fluorescein (FAM) conjugated on the other. If purified human Ku70/80 displaces Cas9 from the DSB, release of the fluorescent DNA end is measured as soluble fluorescence.

G, Liberation of fluorescent DNA ends into the soluble fraction after challenging the target DNA with indicated conditions. NcoI is a restriction endonuclease that cuts the DNA substrate and functions as the control for maximum fluorescence, and maximum fluorescence of Cas9 digested DNA was assessed through Proteinase K treatment after Cas9-DSB formation. See also Fig S2D. Values represent mean +/− s.d., n=3.

The onset of DNA repair at the Cas9 target site was examined with chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays using antibodies specific for Ku70/80 DNA end binding proteins. As an early step in non homologous end joining (NHEJ) repair of DSB, binding of Ku70/80 at Cas9 target sites was used to assess whether template sgRNA were more effective at stimulating repair than non-template sgRNA. The set of four template or non-template sgRNA were cotransfected with Cas9 in mouse ES cells, proteins were crosslinked to DNA after 24 hours, and chromatin was subjected to Ku70/80 ChIP assays. Three (APC, Ptpn11, Tsc1) of the four template sgRNA significantly increased Ku70/80 binding compared to control genomic sites (Fig 2B). By contrast, none of the non-template sgRNA significantly increased Ku70/80 binding in transfected cells such that it was detectable with this ChIP assay. The results of this assay are consistent with increased frequency of DNA repair occurring at template sgRNA compared to non-template sgRNA.

Previous biochemical experiments demonstrated that Cas9 remains tightly associated with DNA after generating a DSB (Jinek et al., 2014; Nishimasu et al., 2014; Richardson et al., 2016). Consistent with this property, in vitro Cas9 nuclease reactions (as in Fig 1D) required removal of Cas9 with proteinase K in order visualize migration of DNA products into an agarose gel by electrophoresis (Fig 2C). A priori, it is not known if any endogenous activity indeed displaces Cas9 from genomic DSB, but Richardson and colleagues showed that challenging the enzyme-product complex with ssDNA displaced Cas9 from the DSB in vitro and also simulated mutagenesis in cells, but only when the ssDNA was complementary to the non-target, PAM distal strand (Richardson et al., 2016). Although a variety of DNA metabolic activities, including nucleosome remodeling and DNA replication, may be capable of displacing Cas9 from DSB, those activities are difficult to predict or control in a genomic-site-specific manner. By contrast, the direction of RNA polymerase through a gene is well annotated throughout the genome, and can be experimentally controlled. Interestingly, the asymmetry in the ability of ssDNA to displace Cas9 from the DSB is consistent with Cas9 being more sensitive to collisions in the template strand orientation compared to the non-template strand orientation (described more extensively below) (Richardson et al., 2016). Therefore, we posited that the strand-bias has differing effects on persistent binding of Cas9 to the DSB, leading to the difference in observed phospho-H2AX signals (Fig 2A) and Ku70/80 binding (Fig 2B). Furthermore, we hypothesized that the Cas9-DSB complex directly prevents DNA repair activities, thus making removal of Cas9 an important step for efficient genome editing.

To begin to test this hypothesis, we determined if persistence of Cas9 binding to DNA prevents DNA end-binding proteins from accessing the Cas9-generated DSB in vitro. We tested whether T4 DNA ligase could evict Cas9 from the DSB by first forming Cas9-DSB complexes on a circular plasmid DNA, then adding T4 DNA ligase and incubating at 16°C before using the reactions for bacterial transformation into E. coli. A lack of antibiotic-resistant colonies indicated that the ligase was unable to access and repair the Cas9 bound plasmid that encoded ampicillin resistance (Fig 2D). Removing Cas9 by a brief heat denaturation before the ligase reaction restored colony-formation, demonstrating that the Cas9-generated DSB was a competent substrate for T4 DNA ligase if Cas9 was removed from the DNA (Fig 2D). DNA exonuclease activity was examined by comparing degradation of a circular DNA linearized by either a restriction endonuclease or by Cas9 (Fig 2E). Exonuclease activity was prevented at the Cas9-generated DNA ends, unless Cas9 protein was removed by heat denaturation (Fig 2E). These indicate that the persistence of the Cas9-DSB complex prevents the DNA ends from being used as substrates for DNA repair enzymes.

To test whether mammalian DSB end binding proteins could evict Cas9 from its DSB, Cas9 was targeted to a DNA that was immobilized on a bead at one end and fluorescently tagged at the other end. Disruption of the Cas9-DSB complex was detected by measuring soluble fluorescence (Fig. 2F). As a positive control, Cas9 digested DNA was treated with proteinase K to release the fluorescent tag from the bead. When challenging the Cas9-DSB with purified human Ku 70/80, a 100x molar excess of the Ku70/80 complex was incapable of displacing Cas9 from the DSB (Fig. 2G), despite Ku70/80 binding to the other DNA ends present in the reaction (Fig. S2C). Although these in vitro observations use a DNA substrate that is not subjected to events occurring on genomic DNA in cells, they demonstrate that the persistent Cas9 binding to DNA can cause the DSB to be inaccessible to DNA end binding proteins. This property is consistent with the possibility that perdurance of Cas9-DSB complex constitutes a rate limiting step during genome editing in vivo.

The Cas9-DSB complex is disrupted by translocating RNA polymerases

We hypothesized that transcription through a Cas9 site increases indel formation, because a translocating RNA polymerase dislodges Cas9 from its DSB (diagramed in Fig 3A). Removing Cas9 from the DSB could stimulate mutagenesis by decreasing the time it takes for the DNA ends to become accessible to cellular repair machinery. To determine if RNA polymerase (RNAP) translocation through the Cas9 site was sufficient to make the DSB accessible to other proteins, we utilized a dsDNA Cas9 substrate harboring the T7 promoter upstream of the cleavage site. The promoter and Cas9 site were orientated so that the sgRNA annealed to the DNA strand that was used as the template by T7 RNAP for transcription. A combined reaction was performed wherein Cas9 digestion of the DNA occurred at the same time as T7 RNAP transcription of the same DNA (Fig 3B). T7 RNAP transcription through the Cas9 site allowed the DSB to be effective substrates for T5 exonuclease activity to degrade the DNA (Fig. 3B). This result indicated that translocation of a T7 RNAP through the Cas9-DSB complex made the DNA ends accessible.

Figure 3. The Cas9-DSB complex is disrupted by translocating RNA polymerases if the sgRNA anneals to the template strand.

A, Schematic illustrating orientation of Cas9 RNP, target DNA, and T7 RNAP translocation colliding with the PAM-distal surface of Cas9 for a template sgRNA and disruption of the enzyme-product complex.

B, DNA degradation by T5 exonuclease ability to access Cas9 generated DSB ends in the presence or absence of T7 RNAP transcription was visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis. Plasmid DNA harboring a T7 promoter was digested with Cas9 or PmeI restriction endonuclease for 30 min prior to incubation with T5 exonuclease and/or T7 RNAP. All reactions were treated with Proteinase K before gel loading.

C, Schematic illustrating experiment in (D) to test whether T7 RNAP can evict Cas9 from the DSB and whether T7 RNAP-displaced Cas9 molecules retain activity. In the presence of inactive T7 RNAP, the Cas9-DSB complex was formed on a Target DNA 1, which contains a T7 RNAP promoter on either end of the DNA for either collision orientation. After 30 minute incubation, rNTPs and a second substrate (Target DNA 2) are simultaneously added. Target DNA 2 lacks a T7 promoter. Target DNA 1 and target DNA 2 each have the same DNA sequence targeted by Cas9. The addition of rNTPs and Target DNA 2 stimulates T7 RNAp transcription and provide a sensor of displaced Cas9 molecules.

D, Agarose gel for the experiment described in (C). Template and Non-template refer to location of T7 promoter on Target DNA 1. Cleavage of target DNA 2 indicates displacement of active Cas9 from Target DNA 1 over time.

E, The ability for T7 RNAP to displace Cas9 with various sgRNA was measured similar to (C), except target DNA 2 was biotinylated on one end and FAM conjugated on the other end, as illustrated in Fig S2D. The 20 mCherry sgRNA (from Fig 1D, S1C) were subjected to the assay in the presence or absence of rNTPs. The fold change in fluorescence levels as a result of T7 RNAP mediated displacement was measured through fluorescence in the soluble fraction. Values are mean +/− s.d.; n=3 for each sgRNA.

F, Fold change Cas9 activity dislodged from mCherry DNA by mammalian RNA Pol II activity from nuclear extracts. Activity was measured by the soluble fraction fluorescent levels for a fluorescent, as above. RNA Pol II activity was controlled by addition of α-amanitin. See also Fig. S2D. Values are mean +/− s.d.; n=2 for each sgRNA.

The DNA strands emanating from one side of the Cas9-DSB complex display more freedom than DNA from the opposite side. As mentioned above, DNA at the PAM-distal surface of Cas9 (Fig 3A) is vulnerable to dissociation when challenged, whereas DNA at the PAM-proximal surface of Cas9 is not (Richardson et al., 2016). The 5′ to 3′ direction of RNA polymerization causes a translocating RNAP to collide with PAM-distal surface of the Cas9-DSB when the sgRNA anneals to the DNA strand used as a template by RNAP (as displayed in Fig 3A). Conversely, when the sgRNA anneals to the non-template strand, translocation of the RNAP will result in a collision with the PAM-proximal surface of the Cas9-DSB complex. We hypothesized that these differences could affect genome editing in vivo if the orientation of the collision affected the ability of RNAP to disrupt the Cas9-DSB complex.

To test a strand bias in the ability of RNAP to dislodge Cas9, we developed an assay that took advantage of the dislodged Cas9-RNP possibly being able to bind to another DNA molecule and generate a DSB in that DNA as long as it contained the sgRNA target sequence. First, Cas9 and a T7 promoter-containing target DNA (target DNA 1) were incubated (30 min) to allow DNA cleavage and formation of the Cas9-DSB complex. Next, a promoterless target DNA (target DNA 2) containing an identical Cas9 target site was added (Fig 3C). Note that a ten-fold molar excess of target DNA 1 relative to Cas9 and stability of the Cas9-DSB complex combined to prevent detectable cleavage of target DNA 2 in the absence of transcription (Fig. 3D). Transcription through the Cas9-DSB complex in target DNA 1 was activated by adding rNTPs, and we began measuring cleavage of target DNA 2 after two minutes of transcription. Target DNA 2 was cut rapidly after initiating transcription, but only if the sgRNA bound to target DNA 1 was annealed to the template strand (Fig 3D, right side). Collision with Cas9-DSB in the non-template orientation did not generate nuclease activity on target DNA 2 (Fig 3D, left side). Since target DNA 2 was not transcribed in this assay, the stimulation of its digestion by T7 RNAP could not be caused by a differential activity of Cas9 on actively transcribed DNA, per se. The rapid digestion of target DNA 2 after RNAP activation is most consistent with RNAP activity on target DNA 1 removing Cas9 from its DSB, and allowing it to digest another DNA molecule. Finally, the inability of T7 RNAP to stimulate target DNA 2 digestion in the non-template sgRNA orientation is consistent with Cas9-DSB complexes being resistant to dissolution by RNAP colliding with the PAM-proximal surface of Cas9. Together these data indicate that the Cas9-DSB complex can be disrupted by RNAP, if the sgRNA anneals to the template strand.

We examined whether the strand biased ability to displace Cas9 in vitro was a general phenomenon by measuring displacement levels for the 20 sgRNA targeted across a linear mCherry substrate. Reactions were performed in the presence or absence of rNTPs to compare transcription mediated displacement levels for each sgRNA. Displacement of Cas9 activity from a T7-containing mCherry DNA was measured using an immobilized, fluorescently tagged target DNA 2. After completion of the combined digestion/transcription reaction, displacement was assessed by fold change in soluble fluorescence stimulated by RNAP (Fig. 3E, S2D). These reactions showed that all template annealed sgRNA were compatible with displacement by T7 RNAP (Fig 3E). In contrast, all of the non-template sgRNA were recalcitrant to displacement (Fig 3E).

T7 RNAP and mammalian RNA Pol II can be considered very different from each other in terms of their biophysical and biochemical properties. Since the in vitro results elucidated above used T7 RNAP, but we propose that the in vivo genome editing effects of transcription are cause by RNA Pol II, the ability of RNA Pol II to displace Cas9 from its DSB were determined. A fluorescent displacement assay was performed essentially as described above for the T7 RNAP experiment (Fig 3E, S2D); however, target DNA 2 was used to detect Cas9 dislodged off of a CMV-mCherry template by RNA Pol II activity from mouse ES cell nuclear extracts (Fig. 3F, S2E). To determine dependence of transcription for Cas9 displacement, reactions were performed in the presence or absence of the RNA Pol II/III inhibitor, α-amanatin, (Fig. S2E). Fold changes in fluorescence levels revealed that none of the eight non-template sgRNA were significantly displaced (Fig 3F). Thus, the non-template sgRNA prevented displacement of Cas9 from DSB for either RNAP tested. By contrast, 10 out of 12 template sgRNA were substantially displaced by RNA Pol II activity (Fig 3F). Interestingly, template sgRNA displayed varying levels of displacement in both transcription scenarios, suggesting sgRNA-determined variability in disruption of the Cas9-DSB complex. Notably, two template sgRNA (#16,19) were not displaced by RNA Pol II activity, and a third (#8) displayed a low level of displacement relative to other template sgRNA. Levels of indel mutagenesis with these three template sgRNA did not significantly increase after transcriptional activation of mCherry in vivo (Fig 2E). Together, these data indicate that a strand biased RNA Pol II displacement of Cas9 from its DSB stimulates indel mutagenesis in cells.

RNA polymerase can convert Cas9 into a multi-turnover nuclease

When using Cas9 for genome editing in cells or organisms, the nuclease is typically expressed or delivered at a high molar ratio relative to its DNA substrates, which are often only 2–4 copies per cell. As such, efficiency of genome editing is likely less dependent on the capabilities of one Cas9 nuclease to processively digest many DNA substrates than it is on a rapid detection of the DSB by the cell’s repair machinery. However, when RNAP collides with the Cas9-DSB complex, the displaced Cas9 molecule retained its nuclease activity (Fig 3B,D), suggesting that Cas9 could be converted from a single-turnover nuclease to a multi-turnover nuclease. An ability of a single Cas9 molecule to digest many DNA substrates could be important when saturating levels of DNA targets need to be digested, such as when high multiplicities of infection occur during bacteriophage infection.

To determine the multi-turnover capabilities of Cas9, a twofold excess of a single, T7 promoter-containing target DNA was used as a substrate for in vitro Cas9 digestion reactions. To test template and non-template orientations using the same sgRNA, the promoter was placed on either end of the target DNA. After an initial 30 min digestion of half of the DNA, addition of rNTPs was used to initiate T7 RNAP activity, and RNAP-stimulated cleavage of DNA was measured for up to 30 min (Fig. 4A). Placing the T7 promoter so that the sgRNA annealed to the template strand stimulated Cas9 cleavage activity with rapid kinetics similar to those observed at the start of a reaction (Fig. 4A, S3A). No stimulation was observed with the non-template strand orientation (Fig. 4A). Continual displacement of Cas9 by T7 RNAP did not appear to disrupt the Cas9-sgRNA interaction, because Cas9 did not exchange sgRNA molecules after being displaced (Fig. S3B).

Figure 4. Strand dependent ability of translocating T7 RNA polymerase to stimulate in vitro multi-turnover nuclease activity by Cas9.

A, Multi-turnover nuclease capability of Cas9 was visualized by agarose gel analysis of hybrid reactions combining Cas9 nuclease and T7 RNAP transcription reactions. A T7 promoter was placed on either end of the target DNA to achieve template or non-template orientation. Cas9 was incubated with DNA for 30m as shown before initiating T7 RNAP with addition of rNTPs.

B, The multi-turnover capacity of template strand Cas9 was measured through titration of in the presence or absence of T7 RNAP. Target DNA was held constant at 150nM. Values represent mean +/− s.d., n=3. (See also Fig. S3C).

C, Titration of substrate in the presence or absence of T7 RNAP. Cas9 was held constant at 12.5nM. Values represent mean +/− s.d., n=2. (see also Fig S3D).

D, Multi-turnover Cas9 activity on various sgRNA was examined through hybrid digestion and transcription reactions of target DNAs harboring T7 RNAP promoters in the template or non-template strand orientation. See also Fig. S4A for schematics and Fig S4B,C and Fig S6 for representative gels. Values represent mean +/− s.d. of fold changes in cleavage by indicated sgRNA in the presence or absence of T7 RNAP, n=3.

Altering the amount of Cas9 (Fig. 4B) or the amount of T7-promoter-containing DNA substrate (Fig. 4C) in a reaction revealed substantial capabilities of Cas9 to function as a multi-turnover nuclease in vitro. Diluting Cas9 showed that T7 RNAP increased the capacity for template sgRNA orientation by 10-fold compared to reactions without T7 RNAP translocation through Cas9, which functioned as a single-turnover nuclease (Fig. 4B, S3C). The improved capacity increased kinetics of Cas9 activity at saturating substrate concentrations (Fig. 4C). T7 RNAP converted Cas9 to a multi-turnover nuclease for a variety of sgRNA and target DNAs tested, but only when the sgRNA annealed to the template DNA strand (Fig. 4D, S4A–C, S6). The magnitude of stimulation by T7 RNAP varied among template strand sgRNA, but it did not appear to correlate with GC content of the target site (Fig. S4D) or the GC content in the sequence next to the PAM (Fig. S4E). In summary, when combined with T7 RNAP and sgRNA in the template strand orientation, Cas9 was effectively transformed from a single-turnover enzyme into a multi-turnover enzyme.

PAM sequences and protospacer targets are more frequently located on template strand of Streptococci phages

We wondered whether the strand bias in Cas9’s potential to act as a multi-turnover nuclease contributed to bacterial immunity. Given a stoichiometry of multiple bacteriophage particles infecting individual bacterial cells, we reasoned that Cas9 functioning as a multi-turnover nuclease could have substantial benefits over a single-turnover nuclease. A multi-turnover nuclease could significantly enhance bacteriophage immunity by allowing a single Cas9 molecule to destroy more than one bacteriophage genome. Therefore, we examined whether there were differences in the frequencies of Cas9 predicted to act as a single-turnover versus multi-turnover nuclease on bacteriophage genomes.

Interestingly, the nucleotide composition of bacteriophage genomes differ in the DNA strand replicated by leading strand versus lagging strand DNA synthesis (Jin et al., 2014; Kwan et al., 2005; Lobry, 1996; Uchiyama et al., 2008). This phenomenon has been named GC skew, and underlying causes for it remain uncertain. For Streptococcus phages that infect S. pyogenes and S. thermophilus, the GC skew is reflected in the nucleotide composition of the plus strand (34% adenine: 27% threonine, and 22% guanine: 17% cytosine). The structure of these bacteriophage genomes places the transcription of genes in predominantly one direction; thus, template strands have a different nucleotide composition than non-template strands. Consequently, the potential PAM sites for spCas9 (NGG) and S. thermophilus Cas9 (stCas9 -NNAGAAW) are not strand neutral. Instead, they preferentially target the template strand at about a 2:1 ratio for spCas9 and 3:1 ratio for stCas9 (Fig. 5A, B, S5A). Mapping crRNA identified from bacteriophage insensitive mutant strains to bacteriophage genomes showed that the actual frequency of crRNA annealing to the template strand are more abundant than those annealing to the non-template strand (Fig. S5B, Table S3) (Achigar et al., 2017; Levin et al., 2013). Thus, the combination of the GC-skew, bacteriophage genome structure, and the PAM sequence results in CRISPR targeting Cas9 to bacteriophage more frequently in a multi-turnover orientation. Rational engineering of Cas9 proteins showed that mutagenesis can relatively simply change the PAM sequence that Cas9 recognizes (Kleinstiver et al., 2016), indicating that the nuclease has potential to be preferentially targeted to either or neither strand in bacteriophage genomes. Based on the above correlations, we hypothesized that targeting Cas9 to anneal to the bacteriophage template strand provides a selective advantage by allowing Cas9 to function as a multi-turnover nuclease during active transcription through target sites.

Figure 5. PAM sequences across Streptococci phage are more frequently oriented on the template strand.

A, Of the 16 surveyed streptococcus phages, all harbor majority of PAM sequences on DNA strand corresponding to the transcription template strand. NNAGGAW = S. thermophilus PAM and NGG = S. pyogenes PAM.

B, Distribution of all PAM sequences among genomes analyzed in A.

Template targeted protospacers enhance bacterial adaptive immunity

To directly test a strand bias effect on bacterial immunity, we used two virulent versions of the ΦNM1 phage. One contains a mutation that inactivates the promoter required for transcription of the lysogeny cassette (ΦNM1γ6) (Goldberg et al., 2014). The other expresses the lysogeny cassette, but it harbors an inactivating deletion within the cI repressor gene (ΦNM1h1) (Fig. 6A). Therefore, neither phage can establish lysogeny, but they differ in the transcription of the lysogeny cassette.

Figure 6. Template strand-targeted protospacers enhance phage interference.

A, General organization of the phage ΦNM1 genome and targeting strategy of the lysogenic repressor gene in the ΦNM1h1 and ΦNM1γ6 mutant phages. The ΦNM1h1 mutant has defective lysogeny genes that transcriptionally active, while the ΦNM1γ6 mutant has transcriptionally silent lysogeny genes. 2 pairs of protospacers were designed to target the mutant phages so that each pair consists of crRNA annealing to either the template or non-template strand with PAM sites within 25bp of each other. S. aureus strains harboring S. pyogenes Cas9 and each of these spacers (RC1–4) were generated respectively for the experiment.

B, Growth curves of S. aureus strains harboring spacers RC1–4 after infection with ΦNM1h1 or ΦNM1γ6. T: template strand orientation. NT: non-template strand orientation.

To test the effect of transcription through a Cas9 target site, we generated different bacterial strains harboring spacers annealing to either template or non-template strand sequences within the repressor gene found in both ΦNM1γ6 and ΦNM1h1 (Fig. 6A). Each strain was infected with each phage, and their survival was determined by measuring OD600 over time (Fig. 6B). The interference efficiency of each spacer against the two phages was interpreted from plate-reader growth curves of infected bacterial cultures. The two spacers targeting the non-template strand (RC2 and RC4) showed similar interference against either phage regardless of whether transcription was active (ΦNM1h1) or inactive (ΦNM1γ6). On the contrary, spacers targeting the template strand (RC1 or RC3) were notably more effective at providing immunity against the actively transcribed target (ΦNM1h1) than the inactive target (ΦNM1γ6). The same four target sites within ΦNM1 were tested for the ability of T7 RNAP translocation to turn Cas9 into a multi-turnover nuclease in vitro (Fig. S6), demonstrating the template strand bias effect on the phage genome. These results show that active transcription across Cas9 targets improves CRISPR immunity by converting Cas9 into a multi-turnover enzyme, but the effect appears to be restricted to Cas9 annealed to the template strand.

DISCUSSION

The consequences of the persistent Cas9-DSB state were elucidated by identifying conditions that dissociate Cas9 from its DNA products. The stable enzyme-product complex precludes DNA repair activities, but it can be disrupted by translocating RNA polymerases in a strand biased manner, conditionally converting Cas9 into a multi-turnover nuclease. This dislodging from the DSB had significant effects on genome editing and bacterial immunity, by increasing mutation frequencies in mammalian cells and mediating enhanced phage interference through multi-turnover nuclease activity.

Although this study focuses on the effects of RNA polymerases on the Cas9-DSB complex, other activities involving DNA translocating proteins or DNA metabolism are also likely to effect removal of Cas9 and mutagenesis at the DSB. The ability of non-template sgRNA to direct even low levels of mutagenesis ostensibly demonstrates that Cas9 in this orientation gets displaced from its DSB. The process of DNA synthesis is certainly sufficient to generate force needed to dislodge Cas9 from a DSB, and individual DNA helicases may also be capable of removing Cas9. In contrast to these other DNA metabolic activities, translocation of RNA polymerase is well annotated across mammalian genomes. In addition, the frequency of interactions is significantly different; multiple RNA polymerase molecules translocate a site in a highly expressed gene, which encounters DNA replication machinery only once per cell division. We suggest the frequency is important, because blunt-ended Cas9 DSBs are frequently repaired in an error free manner; therefore iterative break-repair cycles are required for high mutation rates in Cas9 treated cells. In practice, low mutation rates can be overcome by continuous Cas9 activity over long time periods; however, doing so will increase the probability of off-target mutations and should be avoided.

This new understanding of the interaction between Cas9 and RNA polymerases can be directly applied to CRISPR-Cas9 based genome editing procedures. Our sample of 20 sgRNA to the same gene demonstrates that all these sgRNA are competent to mediate Cas9 digestion of substrates in vitro, yet they displayed substantial variability for indel frequency in vivo. Genomic factors, such as nucleosome occupancy, have previously been shown to affect indel frequency (Horlbeck et al., 2016); however, they are unlikely to affect variability here because all sgRNA targeted a single locus, which should not vary in any of the previously identified factors. Instead a large degree of variability among sgRNA was clearly attributable to the direction of RNA pol II translocation through the Cas9 target site. Although the 2–3 fold increased mutagenesis should be considered substantial, more benefit to genome editing will likely be gained by reducing the probability of using a so-called “dud” sgRNA by avoiding non-template sgRNA. Subsequent research resulting in the modification of Cas9 or discovery of small molecules that destabilize the Cas9-DSB complex could stimulate CRISPR-Cas9 based mutagenesis, especially at non-transcribed sites and in cells with low DNA metabolic activity. In the absence of such advances, our findings provide a simple and straight forward path for increasing efficiency of Cas9-mediated mutagenesis, which is to preferentially use only sgRNA that anneal to the template strand.

This strand biased removal of Cas9 from its DSB is interesting to consider alongside recent biochemical analyses of dCas9 dissociation from DNA. The DNA emerging from the PAM-proximal surface of Cas9 is double stranded and is not accessible to exogenous ssDNA for strand invasion (Richardson et al., 2016). Because of the RNA:DNA hybrid between the sgRNA and target DNA, the DNA emerging from the PAM-distal surface is single stranded, and ssDNA hybridization to PAM-distal sequence can displace dCas9 from its target (Jinek et al., 2014; Nishimasu et al., 2014; Richardson et al., 2016). Mismatched base pairing had the greatest effect on dCas9 dissociation when located at PAM-distal positions, suggesting that the 5′ end of the guide RNA contributes most significantly to the Cas9 off-rate (Boyle et al., 2017). RNA polymerases approaching the PAM-distal surface of the Cas9-DSB complex should have freedom to collide with Cas9. We suggest that a physical collision from RNA polymerases dislodges Cas9 from the DSB, facilitating repair of the DSB, and enabling the Cas9 molecule to cut an additional target DNA. The GC content of the target site and sequence adjacent to the PAM did not significantly affect displacement of Cas9 from the DSB for either orientation. Further biophysical studies are needed to determine why some template sgRNA were more affected by RNA Pol II translocation than others.

Multiple studies have shown that after the CRISPR-Cas9 immune response, some of the acquired viral spacers are highly represented in the population of surviving bacteria (Heler et al., 2015; Paez-Espino et al., 2013). Most likely multiple factors determine the success of a new spacer, but it is tempting to speculate that one such factor could be the disposition of the target sequence with respect to its transcription. Our results suggest that spacers leading to the engagement of Cas9 with its target in a disposition where the nuclease can be removed by RNAP after cleavage would allow a more efficient cleavage of the often multiple phage genomes infecting the host. Such spacers would mediate a more robust immune response, and therefore would be positively selected from the pool of all the acquired spacers. It is possible that the strand biased PAM sequences of StCas9 and SpCas9 evolved to target the strand of bacteriophage genomes where it can become multi-turnover. In comparing evolution of PAM sequences and bacteriophage genomes, it should be noted that the distribution of PAM sequences on either strand of the bacteriophage genome may differ among bacteriophage that infect a given bacteria. However, in the organisms examined here, Steptococci and their associated bacteriophage, the PAM sequence used by Cas9 to target the more effective strand is relatively simple, and altering it requires only a small number of mutations (Kleinstiver et al., 2015). By contrast, the GC-skew is pervasive over the entirety of the bacteriophage genome and is effectively unchangeable relative to the PAM sequence. We propose that targeting the bacteriophage template strand provides an advantage because it will more frequently result in multi-turnover nucleases upon transcription of lytic genes.

STAR METHODS

Contact for Reagent and Resource Sharing

Further information and requests for reagents can be directed to, and will be fulfilled, by the corresponding author Bradley J. Merrill (merrillb@uic.edu).

Experimental Model and Subject Details

Cell culture

Mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells harboring the Rex1:EGFPd2 insertion (A gift from Dr. Austin Smith) (Kalkan and Smith, 2014), or a Rosa26::TetOn-Otx2-mCherry insertion(A gift from Dr. Shen-his Yang) (Yang et al., 2014) were maintained 10cm dishes previously coated with 0.1% gelatin in Knockout DMEM media supplemented with the following: 15% KnockOut Serum Replacement, 2mM l-Glutamin, 1mM HEPES, 1× MEM NEAA, 55μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 U/ml LIF, and 3μM CHIR99021. Cell cultures were routinely split 1:10 with 0.25% trypsin–EDTA every 2–3 days.

HEK293 cells (A gift from Dr. Sojin Shikano) were cultured in high glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Pen/Strep and were split every 2–3 days using 0.25% trypsin–EDTA.

Method Details

Recombinant Cas9 purification

Cas9 (pMJ806, Addgene #39312) was expressed and purified by a combination of affinity, ion exchange and size exclusion chromatographic steps as previously described (Anders et al., 2015).

sgRNA synthesis for in vitro Cas9-RNP

All sgRNAs were cloned into pSPgRNA (Addgene, #47108) following the protocol optimized for pX330 base plasmids (https://www.addgene.org/crispr/zhang/) (Cong et al., 2013). sgRNA oligo sequences, listed without BbsI sticky ends used for cloning, can be found in Supplementary Figures S1H, S2A, and S5D. Templates for in vitro transcription were generated via PCR mediated fusion of the T7 RNAP promoter to the 5′ end of the sgRNA sequence using the appropriate pSPgRNA as the reaction template DNA. PCR reactions were performed using Phusion high GC buffer (NEB) and standard PCR conditions (98°C for 30s, 30 cycles of 9 8°C for 5s, 64°C for 10s and 72°C for 15s, and one cycl e of 72°C for 5m). PCR products were then column pu rified (Qiagen) and eluted in TE (10mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1mM EDTA). DNA concentrations were determined using a Nanodrop 2000 (ThermoFisher Scientific), and then were diluted to 200nM when used as templates for in vitro transcription reactions. The transcription reactions contained 5.0μg/ml purified recombinant T7 RNAP (a gift from Dr. Miljan Simonovic) and 1x transcription buffer (40mM Tris-HCl pH8.0, 2mM spermidine, 10mM MgCl2, 5mM DTT, 2.5mM rNTPs). Following incubation at 37°C for 1 hour, reactions were treated with RNase free DNase I (ThermoFisher Scientific) and column purified using the Zymo RNA Clean & Concentrator kit following the manufacturer’s protocol. The purified RNA products were eluted from the column in 15μl of water.

DNA templates for in vitro Cas9 nuclease reactions

Linear target DNAs for hybrid digestion and transcription assays: mouse Lef1, mCherry, and GFP target DNAs were generated by PCR amplification using 50ng genomic DNA from mESC Rosa26::TetON-Otx2-mCherry cells in a reaction using Phusion high GC buffer (NEB) and standard PCR conditions (98°C for 30s, 30 cycles of 98°C for 5s, 64°C for 10s and 72°C for 15s, and one cycle of 72 °C for 5m). ΦNM1 genomic DNA was amplified with the same parameters, except using Phusion HF buffer. All PCR products were column purified (Qiagen), eluted in TE, and concentrations were determined with a Nanodrop 2000 (ThermoFisher Scientific). For experiments testing effects of T7 RNAP on Cas9, the DNA template was a segment of the mouse Lef1 gene generated with primer set #1 (Table S4), unless otherwise stated.

Plasmid target DNAs: For reactions that required circular dsDNA templates (experiments testing accessibility of exonuclease or ligase enzymes), plasmid target DNAs were prepared using TOPO TA cloning. PCR products of the previously described Lef1::PGK-neo and Ctnnb1::EGFP DNA sequences (Shy et al., 2016) were cloned into the pCR4-TOPO Vector (ThermoFisher Scientific).

In vitro Cas9 DSB formation assays

The basic Cas9 DSB formation assay was prepared in 1x Cas9 digestion buffer (40mM Tris, pH8.0, 10mM MgCl2, 5mM DTT) with a final concentration of 100nM Cas9, unless otherwise stated. Prior to addition of DNA templates, sgRNA was added in molar excess, and incubated at room temperature for 10 min to ensure formation of the Cas9-RNP. Target DNA was added to a final concentration of 200nM and a final reaction volume of 50μl, unless otherwise stated. Reactions were incubated at 37°C for 25 min, then either heat inactivated at 75°C for 10 min or treated with Prot einase K at 37°C for 15 min. DNA fragments from por tion of each reaction (usually 15μl) were separated by electrophoresis 1.5% agarose gel, and visualized with ethidium bromide staining.

For reactions involving T7 RNAP transcription, basic Cas9 digestion conditions were applied, except 1x transcription buffer was used, unless otherwise stated. Upon addition of the target DNA, T7 RNAP was added to a final concentration of 5.0μg/ml. Reactions were placed at 37°C for 25 min, unl ess otherwise stated, and then heat inactivated at 75°C for 10 min. DNase free RNase A (NEB) was added to all reactions except Fig S4A and S5E, then incubated at 37°C for 30 min befo re separating DNA fragments on a 1.5% agarose gel.

T7 and T5 exonuclease assays were performed in 1x Cas9 digestion buffer, unless otherwise stated. T7 exonuclease assays was performed with the Lef1::PGK-Neo plasmid and digested using sgLef1. T5 exonuclease assays were performed with Ctnnb1::EGFP plasmid and digested using sgG2. T5 exonuclease assays containing T7 RNAP were performed in 1x transcription buffer. All reactions contained 100nM Cas9:RNP, 200nM target DNA, and 10U of the appropriate exonuclease. Reactions were subject to Proteinase K treatment before loading onto a 1% agarose gel.

T4 DNA ligase and Cas9 digestion assays were performed in T4 DNA Ligase buffer containing ATP (NEB). Cas9 containing reactions were performed with 200nM Cas9:RNP (sgLef1) and 100nM Lef1::PGK-Neo plasmid were allowed to incubate for 30 min at 37°C, then the temperature was lowered to 16°C and 40U of T4 DNA ligase (NEB) was added and allowed 30 min of incubation. Reactions were transformed into competent DH5a in 3 serial dilutions, and ampicillin-resistant colony forming units determined following overnight incubation at 37°C.

Titrations of Cas9 or substrate: Cas9 hybrid digestion and transcription reactions were performed using sgG2 and a GFP target DNA generated with primer set #6 (Table S4). Cleavage frequencies were measure using ImageJ.

Ku70/80 competition assay

Recombinant human Ku70/80 was purified as previously described (Hanakahi, 2007). A 5′ biotinylated primer (5′ BIOSG-GCCTCACACGGAATCT 3′) and a 3′ FAM conjugated primer (5′ GAGAGCCCTCTCCCAATCTTC-FAM 3′) (Integrated DNA Technologies) were used to amplify a 650bp Lef1 target DNA, PCR products were column purified (Qiagen), and eluted in TE. MyOne Dynabeads (ThermoFisher) were prepared as described by the manufacturer to immobilize 750ng of target DNA to ~4μl of beads. Cas9 and sgRNA were pre-incubated in 1x Cas9 digestion buffer (40mM Tris, pH8.0, 10mM MgCl2, 5mM DTT) for 30 min at room temperature, added to the immobilized DNA in a 5:1 molar ratio, and incubated for 25 min at 37°C. Control reactions witho ut Cas9, but containing DNase, NcoI, and/or Ku70/80 were prepared simultaneously and incubated for 25 min at 37°C. Reactions containing Cas9 were then subject to Proteinase K treatment or addition of excess Ku70/80 (100 fold excess), and incubated for 15 min at 37°C. Bea d-bound DNA fragments were then collected by placing reaction tubes on a magnet, and 10μl of the soluble fraction was transferred to a 384 well plate in technical triplicates. FAM fluorescence levels were measured using a Tecan Infinite Pro200. Calculations were made after subtracting the background fluorescence levels of reactions containing the immobilized but uncleaved FAM labeled DNA. Three independently set up reactions were performed for each reaction condition.

Mammalian nuclear extract preparation

mESC were grown in a 10cm dish to 10×106 confluency and scraped into 3 ml PBS, then pelleted at 16,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was then asp irated and the pellet was resuspended in 800 ul of ice cold Buffer A (10mM HEPES pH 7.9, 1.5mM MgCl2, 10mM KCL, 0.5mM DTT, and 1% protease inhibitors). The pellet was incubated on ice for 10 min, vortexed for 10 sec, then centrifuged at 4°C at 4,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant (cytoplasmic fraction) was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in 200μl of Buffer B (10mM HEPES pH 7.9, 0.4mM NaCl, 10mM KCL, 1.5mM MgCl2, 0.1mM EDTA, 12.5% glycerol, 0.5mM DTT, and 1% protease inhibitors). The resuspended pellet was incubated on ice for 30 min then centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant (nucl ear fraction) was aliquoted and stored at −80°C.

Nuclear extract and Cas9-VPR transcriptional activity validation (qPCR)

Nuclear extracts: nuclear extract (6μl per reaction) was added to reactions containing: 12μl 1x NE transcription buffer (20mM HEPES pH 7.9, 100mM KCL, 0.2mM EDTA, 0.5mM DTT, 20% glycerol), 3μl of 50mM MgCl2, 1.2μl 25mM rNTPs, and 38nM CMV-mCherry (serving as RNA Pol II transcription template, see below for PCR amplification procedure) to create final reaction volumes of 45μl. Control reactions contained 6μg of α-amanitin (Sigma-Aldrich #04622) or lacked rNTPs. Reactions were incubated at 37°C for 45 min, then 10U of DNase I was added (ThermoFisher) and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. After completion of DNA digestion, 150μl of TE and 200μl of 25:24:1 phenol:chloroform:isoamyl (Sigma-Aldrich) were added. Reactions were then vortexed for 15 sec, briefly centrifuged, then the aqueous layer was transferred to a fresh 1.5 ml tube. RNA was precipitated from the mixture by adding 3 volumes of ice cold 100% ethanol, then centrifuged for 10min at top speed. RNAs were reconstituted in water and diluted to 500ng/μl. 1μg of RNA was converted to cDNA using Superscript III (ThermoFisher) and quantitative real time PCR was performed using primer set #10 (Table S4) by combining 250ng of cDNA from each sample was with Perfecta SYBR Green Supermix (Quanta #95053). qPCR was performed on a C1000 thermal cycler and CFX96 Real Time System (Bio-Rad) with the following parameters: 95°C for 2 min, then 40 cycles of 95°C for 30s and 60°C for 45s. Quantities were normalized to control reactions of CMV-mCherry DNA used to create a standard curve. Standard log transformation of Ct values and standard curve equation was then applied before calculating fold change of experimental conditions over the no rNTP condition.

Cas9-VPR transcriptional activation validation: 48 hours after transfection of reagents containing Cas9-VPR targeted to TTN with a 14nt sgRNA, roughly 1.5 million HEK293 cells were harvested for RNA through washing twice with PBS then adding 600ul of Trizol. RNA was purified using the DirectZol kit (Zymo) including the DNAse I digestion step. Purified RNA was eluted using 20ul of water. cDNA generation and qPCR protocol was performed as mentioned above. Transcriptional activity of Cas9-VPR at the target site was analyzed through calculating ΔΔCt for the sgTTN (correctly targeted) condition to a non-targeted control.

Fluorescent Cas9-RNP displacement assay

Generation of RNA Pol II or T7 RNAP promoter containing target DNAs

CMV-mCherry was amplified with primer set #11 (Table S4) to include the polyA from pmCherry-C1 (Clontech), and T7-mCherry was amplified with primer set #4 (Table S4). PCRs conditions contained Phusion high HF buffer (NEB) and standard PCR conditions (98°C for 30s, 30 cycles of 98°C for 5s, 64°C for 10s and 72°C for 20s, and one cycle of 72 °C for 5m), and PCR products were column purified (Qiagen), and eluted in TE.

Generation of displaced Cas9 fluorescent detection substrates

Fluorescent target DNAs (FT-DNA) were generated to contain 3 or 4 Cas9 target sites per FT-DNA to accommodate all 20 mCherry sgRNA, rendering DNAs that range from 134bp to 90bp (Table S2). FT-DNAs were prepared by ordering single stranded sense ultramers (IDT) and PCR amplifying with a 5′ biotinylated primer (5′ BIOSG-CGTAAACGGCCACAAGTTCAG 3′) and a 3′ FAM conjugated primer (5′ CTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATGCC-FAM 3′). PCR conditions consisted of Phusion high HF buffer (NEB) and standard PCR conditions (98°C for 30s, 30 cycles of 98°C for 5s, 61°C for 10s and 72°C for 5s, and one cycle of 72°C for 5m), and PCR products were column purified (Qiagen), and eluted in TE.

Displacement assays with mammalian nuclear extracts

To test the effect of RNA polymerase II, Cas9 digestion reactions were carried out in 15μl reactions containing: in 4μl of 1x NE transcription buffer, 1μl of 50mM MgCl2, 0.4μl 25mM rNTPs, and 2.1μl of freshly thawed nuclear extract. Cas9 was added to a final concentration of 26nM and respective sgRNA was added in excess, then incubated at RT for 10 min to allow formation of RNP. After formation of the RNP, 6μg of α-amanitin was added to respective reactions, then CMV-mCherry was added to a final concentration to all reactions to a final concentration of 38nM and to render a final volume of 15ul for all reactions. Reactions were then incubated at 37°C for 45 min. While the hy brid transcription/digestion reactions were incubating, FT-DNAs were immobilized to MyOne Dynabeads (ThermoFisher) as described by the manufacturer. The immobilized FT-DNAs were heated at 75°C for 5 min to remove non-specific binding, then washed twice, then resuspended in 1x NE transcription so FT-DNA was at a concentration of 100ng/μl. Upon completion of the Cas9 transcription/digestion reactions, the bead:FT-DNA conjugates were added to each reaction so FT-DNAs were in 2:1 molar ratio to CMV-mCherry. The reactions were incubated at 37°C for 15min, then heated at 75 °C for 10 min to denature the displaced Cas9 which was bound to FT-DNAs thereby releasing the cleaved fluorescent end of the FT-DNAs into the soluble fraction. All reactions were then placed on a magnet, and the soluble fraction was removed and placed into a suitable plate for reading FAM fluorescence levels were measured using a Tecan Infinite Pro200. Calculations were made after subtracting the background fluorescence levels of reactions containing the immobilized but uncleaved FT-DNAs respectively. Two independently set up reactions were performed for each reaction condition.

Displacement assays with T7 RNA polymerase

Reactions were performed in the exact manner as the mammalian nuclear extract displacement assays except with minimal changes: reaction buffer was 1x transcription buffer, and presence or absence of transcription was controlled through presence or absence of rNTPs rather than using α-amanitin. Two independently set up reactions were performed for each reaction condition.

Transfection and selection conditions

Within 2 hrs of transfections, 0.25 × 105 ES cells were freshly plated in each well of 24 wells dishes. For each well, 2.5μl of Lipofectamine 2000 and relevant DNAs were incubated in 125μl OPTI-MEM (GIBCO #31985) before adding to wells. For the Cas9 mutagenesis of 40 distinct genes in ES cells, transfections included 150ng pPGKpuro (Addgene plasmid # 11349), 150ng pX330 (lacking sgRNA insert), and 150ng of the relevant pSPgRNA plasmid. To assess background mutation rate due to possible deep sequencing or amplification errors, a transfection containing pSPgRNA with empty sgRNA site was assessed alongside the other sgRNA-containing transfections. Two days after transfection, cells were split into 2μg/ml puromycin and selection was applied for 48hrs before isolating genomic DNA by overnight lysis with Bradley Lysis buffer (10mM Tris-HCl, 10mM EDTA, 0.5% SDS, 10mM NaCl) containing 1mg/ml Proteinase K, followed with EtOH/NaCl precipitation, two 70% EtOH washes, and eluted in 50μl of TE. For mCherry targeting, transfections contained the same DNA, except pSPgRNA targeted the mCherry genomic insertion, genomic DNA was isolated 48 hours after transfection in 50μl of Quick Extract solution (Epicentre) for T7E1 assays.

Western blot

~2 million ES cells were collected from 6 well plates after washing twice with PBS, then scraping into 600ul of PBS followed by pelleting at 5,000 rpm for 5 minutes. The cell pellet was then resuspended in 100ul of preheated (98°C) 2x Laemmli lysis buffer (4% SDS, 20% glycerol, 120mM Tris-Cl, 0.02% w/v bromophenol blue) and heated at 98°C for 10m. While still hot, each sample was resuspended with a 25 gauge needle to shear genomic DNA. 25μl of each sample was loaded onto a 12% SDS PAGE gel and then transferred to 0.22μm PVDF membranes. Membranes were blocked for 1 hour at room temperature with 5% BSA before probing for phospho-H2AX, or 5% milk before probing for β-actin. Anti-phospho-H2AX was diluted to 0.05ug/ml in 5% BSA, and anti-β-actin was diluted 1:2000 in 5% milk. Both primary antibodies were incubated o/n at 4°C.

Ku70/80 Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

~3.5 million ES cell were seeded onto 10cm dishes in 9ml of media then immediately transfected with a 1ml solution containing Cas9 expression and 4 template or 4 non-template sgRNA expression plasmids. 24 hours after transfection, crosslinking was performed by adding 270μl of 37% formaldehyde to each dish. Cells were then rotated gently at RT for 12.5 min, and then 540μl of 2.5M glycine was added to quench the reaction. Cells were then washed with cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS) twice prior to harvesting by silicon cell scrapers and centrifugation (4°C, 4000 rpm), followed by flash freezing with liquid nitrogen and storage at −80°C. After thawing, all subsequent steps were performed at 4°C or on ice and fresh protease inhibitors were added to each lysis buffer. Cells were resuspended in lysis buffer (LB) 1 (50 mM Hepes pH 7.7, 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10% Glycerol, 0.5% NP-40, 0.25% Trtiton-X-100) and gently rotated for 20 min. Cells were pelleted for 10 min at 2500 RPM and then in LB 2 (200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 10 mM Tris pH 7.5). After incubation for 10 minutes under constant rotation, cells were pelleted again and resuspended in LB 3 (1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% Na-deoxycholate). Sonication was performed using a Branson Digital Sonifier 450 at 60% amplitude on ice for 15 cycles (30 seconds ON, 60 seconds OFF) to obtain an average DNA fragment size of 500 bp. After sonication, 1/10 volume of 10% Triton-X-100 was added and then the samples were centrifuged for 10 min at max speed to remove cellular debris. 100μl of each chromatin extract was uncrosslinked at 65°C overnig ht, treated with RNaseA for 1 hour, then proteinase K for 1 hour, and then purified using phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation to determine the concentration of DNA and to serve as an input control.

To prepare the Ku70/80 antibody for immunoprecipitation, 4ug antibody per ChIP was incubated with 20ul of Protein G Dynabeads. Each condition was split into three technical triplicates and then Ku70/80 immunoprecipitation was performed by incubating 10μg chromatin extract overnight at 4°C with the antibody bound beads while gently rocking. The beads were then washed 4 times with 500ul RIPA buffer (50 mM Hepes, 1mM EDTA, 0.7% Na-deoxycholate, 1% NP-40, 0.5 M LiCl) and once with 500ul TBS (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.6). Bound complexes were eluted from the beads by resuspending in 400ul elution buffer (50mM Tris pH 8, 10mM EDTA, 1% SDS) and heating at 65°C with occasional vortexing. Crosslinks were reversed by incubation at 65°C overnight, and sampl es were treated with RNase A and proteinase K subsequently for 1 hour each. DNA was isolated using phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation, followed by resuspension in 200ul Tris-EDTA. To compare the amount of immunoprecipitated DNA for each condition, qPCR was performed following the aforementioned general protocol. 5ul input and ChIP DNA for each condition was added to each 25ul qPCR reaction, and Gapdh served as the negative control region. Primers used for quantitative PCR following ChIP are listed in the Table S4. Ct values for each input were corrected to account for the difference in starting chromatin extract amount for input vs ChIP, and then the level of DNA immunoprecipitated as detected by the qPCR was calculated as a % of input for each condition. Finally, the % input of each target site was divided by the % input of the Gadph control to determine fold enrichment of Ku70/80 bound DNA.

T7 endonuclease 1 assays

Genomic DNA was used as a template in a PCR reaction using Phusion polymerase (NEB) and standard PCR conditions (98°C for 30s, 30 cycles of 98°C for 5s, 55°C for 10s and 72°C for 25s, and one cycle of 72 °C for 5m). 5μl of each PCR product was added to 19μl of 1x NEBuffer 2 (NEB), denatured at 95C for 10 min, then brought down to room temperature by decreasing the temperature 1C per second. 1μl of T7E1 (NEB) was added to each reaction, and allowed to incubate at 37°C for 25 min. DNA fragments were separated by electrophoresis through a 1.5% agarose gel. Gel images were analyzed and indel frequencies were quantified using ImageJ.

Flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions were prepared by trypsinization and re-suspension in 2% FBS/PBS/2mM EDTA. Cells were analysed on a LSRFortessa flow cytometer. Data analysis was performed using FlowJo v9.3.2. Live cells were gated by forward scatter and side scatter area. Singlets were gated by side scatter area and side scatter width. At least 5 × 105 singlet, live cells were counted for each sample. mCherry fluorescence events were quantified by gating the appropriate channel using fluorescence negative cells as control.

Targeted deep-sequencing preparation

Preparation: genomic DNA was harvested four days after transfection and approximately 100ng of DNA was used in PCR to amplify respective target sites while attaching adapter sequences for subsequent barcoding steps (Table S1 for NGS primers). PCR products were analyzed via agarose gel and then distinct amplicons were pooled for each replicate respectively in equal amounts based on ImageJ quantification. Pooled PCR products were purified with AMPure beads (Agilent), and 5ng of the purified pools was barcoded with Fluidigm Access Array barcodes using AccuPrimer II (ThermoFisher Scientific) PCR mix (95°C for 5m, 8 cycles of 95°C for 30s, 60°C for 30s and 72°C for 30s, and one cyc le of 72°C for 7m). Barcoded PCR products were anal yzed on a 2200 TapeStation (Agilent) before and after 2 rounds of 0.6x SPRI bead purification to exclude primer dimers. A final pool of amplicons was created and loaded onto an Illumina MiniSeq generating 150bp paired-end reads.

Generation of spacers targeting ΦNM1

Plasmids harboring Cas9, tracrRNA and single-spacer arrays targeting ΦNM1 were constructed via BsaI cloning onto pDB114 as described previously (Heler et al., 2015). Specifically, spacers RC1 (plasmid pRH320), RC2 (pRH322), RC3 (pRH324) and RC4 (pRH326) were constructed by annealing oligo pairs H560-H561, H564-H565, H568-H569 and H572-H573, respectively. Each pair of annealed oligos contains compatible BsaI overhangs and can be found in Table S3.

ΦNM1 infection assays

Phage ΦNM1h1 was isolated as an escaper of CRISPR type III targeting of ΦNM1 with spacer 4B (Goldberg et al., 2014). Plate reader growth curves of bacteria infected with phage were conducted as described previously (Goldberg et al., 2014) with minor modifications. Overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 into 2ml of fresh BHI supplemented with appropriate antibiotics and 5mM CaCl2 and grown to an OD600 of ~0.2. Immune cells carrying targeting spacers were diluted with cells lacking CRISPR-Cas in a 1:10,000 ratio and infected with either ΦNM1h1 or ΦNM1g6 at MOI 1. To produce plate reader growth curves, 200μl of infected cultures, normalized for OD600, were transferred to a 96-well plate in triplicate. OD600 measurements were collected every 10 min for 24 hrs.

Quantifications

Agarose gel quantifications

For all Cas9 digestion reactions and T7E1 assays, percent cleavage values were determined by measuring densitometry of individual DNA bands in ImageJ, then dividing the total cleaved DNA by total DNA.

Targeted deep-sequencing analysis

Determination of indel frequencies made use of CRISPResso command line tools that demultiplexed by amplicon, where appropriate, and then determined indel frequency by alignment to reference amplicon files (Pinello et al., 2016). Outputs were assembled and analyzed using custom command-line, python, and R scripts which are available upon request.

Bioinformatic analysis of RNA seq vs indel frequencies

The source of large scale indel mutagenesis and RNA-seq data were from previously published reports (Chari et al., 2015; Chavez et al., 2016). Blat and bedtools command line tools (Quinlan and Hall, 2010) were used to classify each of the sgRNA used by Chari et al (Chari et al., 2015) as targeting either the template or non-template gene strand. All data were merged and visualized using RStudio version 1.0.136 (package: ggplot2), allowing for the determination of the effect of FPKM and strand orientation on indel frequency.

Statistical Analysis

Agarose gel quantifications for T7E1

The three biological replicates of the mutagenesis data presented in Fig. 1E were analyzed for statistical significance using RStudio. Statistical analyses were performed by generating p values for each sgRNA with a two sample t-test to compare plus and minus doxycycline, then all p values were adjusted via Bonferroni correction.

ChIP-qPCR comparisons

Template and non-template groups for each gene were analyzed for statistical significance in R studio using a two sample t-test where all p values were adjusted via Bonferroni correction

Targeted deep-sequencing comparisons

Statistical analyses were performed by pooling indel frequencies for all sgRNA annealing to the template or non-template strand, creating two separate groups. Then, unpaired, two tailed t-test was performed.

Bioinformatic analysis of RNA seq vs indel frequencies

Statistical analyses and significance were determined with Multiple Comparisons of Means with Tukey contrasts (package: multcomp).

Data and Software Availability

All scripts for statistical analysis or preparation of NGS data mentioned throughout the methods section are available upon request.

Raw sequencing data will be available on NCBI (SRP148739). Unprocessed gels are available on Mendeley (doi:10.17632/k3tkmh7fj4.1).

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table S4 – Oligonucleotide sequences used in this study. Related to Star Methods.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Persistent Cas9 binding blocks DNA repair proteins from accessing Cas9-generated breaks

RNA Polymerase can dislodge Cas9 from DNA breaks in a highly strand-biased manner

Dislodging Cas9 with RNA polymerase generates a multi-turnover nuclease activity

Targeting of Cas9 to phage genome is strand-biased towards multi-turnover activities

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ying Su and Dr. Arnon Lavie for assistance with the purification of Cas9, Dr. Sylvain Moineau for assistance with bacteriophage genomics, Dr. Stefan Green and the DNA Services core facility at UIC for assistance with sequencing, Dr. Miljan Simonovic for his assistance with interpretation of in vitro experiments. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [R01-HD081534 to B.J.M; 1DP2AI104556 to L.A.M.], and the UIC Center for Clinical and Translational Sciences [R.C., M.S.M.]. R.H. is the recipient of a Howard Hughes International Student Research Fellowship. L.A.M. is supported by the Rita Allen Scholars Program, a Burroughs Wellcome Fund PATH award, and a HHMI-Simons Faculty Scholar Award, N.Y.C. and G.M.C. are supported by a US National Institutes of Health National Human Genome Research Institute grant no. RM1 HG008525 and the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, A.C. is supported by a Burroughs Wellcome Fund CAMS award.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.C. and B.J.M. jointly designed the study; R.H. and L.A.M. conceived the phage experiments. R.C., R.H., M.S.M. and M.R. designed and performed experiments; L.H., G.M.C., and M.R. provided reagents; R.C., and M.S.M. conducted analysis of mutation frequency with technical advice and support from N.C.Y., and A.C. R.C., R.H., L.A.M., and B.J.M. wrote the manuscript with significant advice and discussion from all authors.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

L.A.M is the founder of Intellia Therapeutics and a member of its scientific advisory board. G.M.C’s technology transfer, advisory roles and funding sources are declared at arep.med.harvard.edu/gmc/tech.html.