Abstract

Objective

To describe the contemporary epidemiology of pediatric sepsis in children with chronic disease, and the contribution of chronic diseases to mortality. We examined the incidence and hospital mortality of pediatric sepsis in a nationally representative sample and described the contribution of chronic diseases to hospital mortality.

Study design

We analyzed the 2013 Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD) using a retrospective cohort design. We included non-neonatal patients <19 years old hospitalized with sepsis. We examined patient characteristics and the distribution of chronic disease and estimated national incidence and described hospital mortality. We used mixed effects logistic regression to explore the association between chronic diseases and hospital mortality.

Results

A total of 16,387 admissions, representing 14,243 unique patients, were hospitalized with sepsis. The national incidence was 0.72 cases per 1000 per year (54,060 cases annually). Most (68.6%) had a chronic disease. The in-hospital mortality was 3.7% overall; 0.7% for previously healthy patients and 5.1% for patients with chronic disease. In multivariable analysis, oncologic, hematologic, metabolic, neurologic, cardiac and renal disease, and solid organ transplant were associated with increased in-hospital mortality.

Conclusions

More than 2 out of 3 children admitted with sepsis have at least 1 chronic disease and these patients have a higher in-hospital mortality than previously healthy patients. The burden of sepsis in hospitalized children is highest in pediatric patients with chronic disease.

Sepsis and septic shock remain significant causes of morbidity and mortality for children in the United States and around the world. An analysis of a 7-state dataset of pediatric sepsis patients in 1995 estimated that there were 75,000 cases in the United States (US) annually (1). A subsequent update using data from 2000 and 2005 showed a 1.6-fold increase in incidence from 0.56 per 1000 children to 0.89 per 1000 children (2), but more recent estimates are not available. Conversely, the hospital mortality has declined in some analyses. For example, the hospital mortality decreased from 10.3% in 1995 to 8.9% in 2005 (1,2), and a longitudinal analysis of a cohort of patients admitted to a pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) with sepsis from 2004-2012 also showed a decline from 18.9% to 12.0% (3).

Recent reports have found that the majority of children with sepsis have at least one chronic disease (4,5), but contemporary national estimates of the prevalence of sepsis and risk of hospital mortality in children with different chronic diseases are not available. Although prior studies showed increased hospital mortality in pediatric patients with sepsis and a history of cancer or hematopoietic stem cell transplant (6) and congenital heart disease (7,8), the interaction of other chronic diseases with mortality risk in pediatric sepsis has not been previously described. The Improving Pediatric Sepsis Outcomes (IPSO) initiative, recently implemented by the Children’s Hospital Association (9), incorporates special considerations for children with cancer, but no guidance exists for children with other chronic diseases. We sought to describe the proportion of children hospitalized with sepsis who had chronic disease, and in-hospital mortality in children with different chronic diseases as well as previously healthy children. We hypothesized that children with chronic disease would have higher in-hospital mortality than previously healthy children.

Methods

We used a retrospective cohort design and the Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD) (10) from 2013, which includes 49% of all hospital admissions in the US. The NRD includes hospitalizations for children who were between 1 and 18 years old from 21 states and hospitalizations for children less than 1 year old from 9 states. This study was deemed exempt by the University of Pittsburgh institutional review board.

We estimated the national incidence of sepsis using the weights provided by the NRD and described the hospital mortality and 90-day readmission rate for all pediatric hospitalizations and across different subgroups. We examined the proportion of sepsis cases among children with different chronic diseases and the relationship between individual chronic diseases and hospital mortality after adjusting for potential confounders.

Identification of sepsis

We limited our study to admissions of non-neonatal pediatric patients <19 years old because neonatal patients have different risk factors for sepsis and outcomes than pediatric patients (11). We identified neonatal admissions using neonatal-specific diagnosis codes (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9 CM) 760.xx-779.xx). We included all non-neonatal pediatric admissions discharged between January 1st, 2013 and December 31st, 2013. We identified admissions with sepsis or septic shock using ICD-9 CM codes for infection and at least one organ dysfunction using codes in the first 15 diagnosis fields (combination codes, Appendix; available at www.jpeds.com) or those with codes for sepsis, severe sepsis or septic shock (ICD-9 CM codes 995.91, 995.92 and 785.52) in 25 diagnosis fields. We used both approaches because prior evaluations have found poor correlation and differential outcomes between cases identified using either approach (12). We performed limited descriptive analyses in patients identified using sepsis codes and stratifying by sepsis without organ failure compared with sepsis with identified organ failure, severe sepsis or septic shock.

Clinical characteristics

We examined clinical characteristics for each admission, including demographics, chronic diseases, severity of illness, utilization of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) during hospital stay, and hospital characteristics. We used the pediatric complex chronic conditions classification (PCCC) system, version 2 to identify chronic diseases (13). Briefly, this system incorporates ICD-9 CM codes for chronic conditions in children that are expected to last at least 12 months and involve one or multiple organ systems severely enough to require specialty pediatric care, or include technology or medical device dependence. We assessed illness severity using the all-patient refined diagnosis-related group (APRDRG), a proprietary and validated tool used across all Health Care and Utilization Project (HCUP) datasets. We assessed organ failure using ICD-9 CM codes for mechanical ventilation (96.7), shock including septic shock (458.8, 458.9, 785.50, 785.52, 785.59), acute kidney injury (584.X, 788.5), and failure of the neurologic (293.0, 293.1, 293.9, 348.3X, 780.09), hepatic (570.X, 573.4), and hematologic (286.6, 286.7, 286.9, 287.49, 287.5) systems. We assessed admissions that involved ECMO using procedure code 39.65. We described hospitals where patients received care using the pre-defined categorical variable from the NRD for metropolitan teaching, metropolitan non-teaching, or non-metropolitan hospitals.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.4 and R 3.3.3. The clinical characteristics of the sample of pediatric admissions with sepsis were quantified using frequencies and percentage of the total number of admissions.

We calculated the incidence of sepsis for all pediatric cases and stratified by age and coding criteria (combination and sepsis codes). We estimated the national incidence of sepsis in non-neonatal children younger than 19 years old by applying the sampling weights and strata provided by the NRD (14). No other analyses utilized the NRD sampling weights. We reported hospital mortality for all pediatric sepsis cases and stratified by age, chronic diseases, and coding criteria.

We examined the relationship between individual chronic diseases and hospital mortality among children hospitalized with sepsis by fitting a multivariable mixed effects logistic regression model and adjusting for demographic features (age and sex) and admitting hospital type. Random intercepts were included to account for correlation of outcomes among patients who received care within similar types of hospital and within the same hospital. We limited the logistic regression analysis to one admission per sepsis patient using the unique patient linking identification in the NRD; specifically, only the first chronological admission involving sepsis in 2013 was included in the analysis.

Results

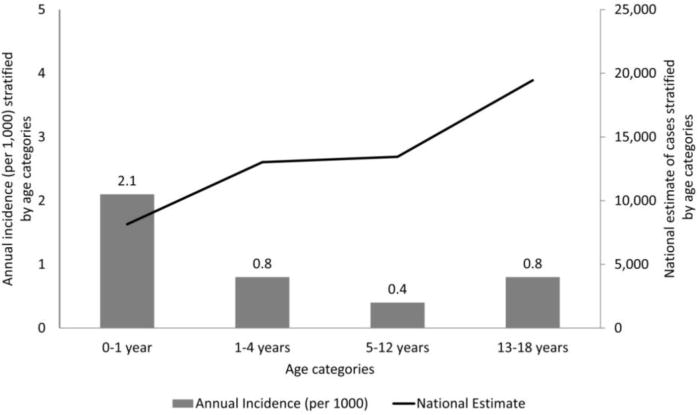

Of the 14,325,172 admissions in the NRD, 1,227,931 admissions were in patients younger than 19 years of age, of which 309,675 (25.2%) were neonatal admissions. Of the 918,256 non-neonatal pediatric admissions, 16,387 met criteria for sepsis. The estimated national incidence in the pediatric population was 0.72 per 1000, with an estimated 54,060 cases per year (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Incidence and estimated annual cases of pediatric sepsis by age group. Incidence on left y-axis with corresponding bar graphs (per 1000/year). Total estimated annual cases in each age group on right y-axis with corresponding line graph.

Clinical characteristics

The clinical characteristics of the 16,387 pediatric admissions are shown in Table 1. Among these admissions, 11,247 (68.6%) involved patients with at least one chronic disease. Furthermore, 6,576 (40.1%) had explicit codes for sepsis, and 12,762 (77.9%) were identified using combination coding. Within the group identified using explicit codes, 3,364 had sepsis without organ dysfunction identified, 964 had a sepsis code and an organ dysfunction code, and 2,278 had severe sepsis or septic shock. Among the group with sepsis without organ dysfunction, 43.6% (n=1,465) of admissions had a chronic disease. Among admissions with sepsis codes and organ dysfunction, 73.2% (n=684) had a chronic disease, and among those with severe sepsis or septic shock, 74.9% (n=1,706) had a chronic disease. Less than half of admissions (34.9%, n=5,712) received invasive mechanical ventilation, and 19.0% (n=3,114) of admissions had shock. Within the cohort, 114 (0.7%) of admissions involved ECMO, and 12 (10.5%) of these admissions were previously healthy patients. In terms of illness severity, 6,754 (41.2%) had extreme illness severity using the proprietary APRDRG methodology and 3,046 (18.6%) had extreme risk of mortality.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics by frequency (percent) of admissions for sepsis among non-neonatal children younger than 19 years.

| Variable | All admissions with sepsis (N=16,387) | Admissions with sepsis codes (N=6,576)* | Admissions with combination codes (N=12,762)* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic** | |||

| Age <1 year | 1,453 (8.9) | 661 (10.1) | 1,018 (8) |

| Age 1-4 years | 4,058 (24.8) | 1,398 (21.3) | 3,236 (25.4) |

| Age 5-12 years | 4,311 (26.3) | 1,531 (23.3) | 3,570 (28) |

| Age 13-18 years | 6,565 (40.1) | 2,986 (45.4) | 4,938 (38.7) |

| Female | 8,231 (50.2) | 3,451 (52.5) | 6,228 (48.8) |

| Public insurance | 9,525 (58.2) | 3,747 (57.1) | 7,489 (58.8) |

| Chronic disease*** | |||

| Previously healthy | 5,140 (31.4) | 2,721 (41.4) | 3,171 (24.8) |

| Any chronic disease | 11,247 (68.6) | 3,855 (58.6) | 9,591 (75.2) |

| Neurologic or neuromuscular conditions | 4,364 (26.6) | 1,069 (16.3) | 4,026 (31.5) |

| Cardiovascular conditions | 2,592 (15.8) | 886 (13.5) | 2,279 (17.9) |

| Respiratory conditions | 2,935 (17.9) | 465 (7.1) | 2,824 (22.1) |

| Renal and urologic conditions | 1,735 (10.6) | 649 (9.9) | 1,491 (11.7) |

| Gastrointestinal and hepatologic conditions | 4,580 (27.9) | 1,315 (20) | 4,029 (31.6) |

| Hematologic and immunologic conditions | 2,137 (13) | 1,109 (16.9) | 1,615 (12.7) |

| Metabolic conditions | 1,965 (12) | 807 (12.3) | 1,681 (13.2) |

| Congenital and genetic conditions | 1,939 (11.8) | 565 (8.6) | 1,716 (13.4) |

| Oncologic conditions | 2,216 (13.5) | 995 (15.1) | 1,770 (13.9) |

| Technology dependence | 5,842 (35.7) | 1,653 (25.1) | 5,207 (40.8) |

| Solid organ transplant | 868 (5.3) | 329 (5) | 731 (5.7) |

| Organ failure | |||

| Need for mechanical ventilation | 5,712 (34.9) | 1,313 (20) | 5,654 (44.3) |

| Presence of shock | 3,114 (19.0) | 1,795 (27.3) | 3,071 (24.1) |

| Acute renal failure | 2,190 (13.4) | 665 (10.1) | 2,163 (16.9) |

| Neurologic failure | 1,329 (8.1) | 227 (3.5) | 1,317 (10.3) |

| Hepatic failure | 190 (1.2) | 94 (1.4) | 181 (1.4) |

| Hematologic failure | 3,316 (20.2) | 940 (14.3) | 3,287 (25.8) |

| APRDRG Illness severity | |||

| Mild/moderate severity | 3,561 (21.7) | 2,079 (31.6) | 1,666 (13.1) |

| Major severity | 6,031 (36.8) | 1,678 (25.5) | 5,009 (39.2) |

| Extreme severity | 6,754 (41.2) | 2,808 (42.7) | 6,053 (47.4) |

| APRDRG Risk of Mortality | |||

| Mild/moderate risk | 8,380 (51.1) | 3,074 (46.7) | 5,599 (43.9) |

| Major risk | 4,920 (30) | 1,624 (24.7) | 4,242 (33.2) |

| Extreme risk | 3,046 (18.6) | 1,867 (28.4) | 2,887 (22.6) |

| Hospital type | |||

| Metropolitan teaching | 13,661 (83.4) | 5,048 (76.8) | 11,202 (87.8) |

| Metropolitan non-teaching | 2,140 (13.1) | 1,141 (17.4) | 1,305 (10.2) |

| Non-metropolitan | 586 (3.6) | 387 (5.9) | 255 (2) |

| Length of stay (median and IQR) | 7 (3, 16) | 6 (3, 15) | 8 (4, 18) |

Because patients could meet either or both definitions, categories add to more than total number in cohort.

Age ranges are inclusive; e.g. ages 1-4 include patients of age 1, 2, 3 and 4 years.

Because patients could have more than one chronic disease, percentages add to more than 100%

Hospital mortality

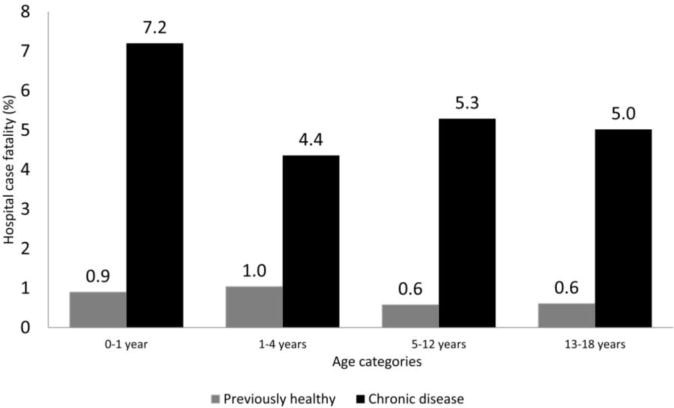

The hospital mortality rate among all non-neonatal pediatric admissions with sepsis was 3.7% (607 of 16,387). The hospital mortality among admissions without a chronic disease was 0.7% (37 of 5,140) and was 5.1% (570 of 11,247) among admissions with a chronic disease, with 93.9% of in-hospital mortality in this cohort occurring in patients with chronic disease. Similar results were observed regardless of age group (Figure 2). The hospital mortality among admissions identified using combination coding alone was 4.4% (565 of 12,762), and was 5.5% (360 of 6,576) among admissions with codes for sepsis, severe sepsis, or septic shock. Among the subpopulation who received ECMO, the mortality rate was 33.3% (4 of 12) in previously healthy patients and 39.2% (40 of 102) in those with any chronic disease.

Figure 2.

Hospital mortality by age group and chronic disease. Previously healthy patients in each age group are shown as gray bar and patients with chronic disease are shown as black bar.

We fit a multivariable model of in-hospital mortality among the 14,243 first chronological admissions that had complete data for hospital mortality and covariates (Table 2). Most chronic diseases were associated with increased hospital mortality.

Table 2.

Association between individual chronic diseases and hospital mortality among 14,243 unique non-neonatal sepsis patients.

| Proportion who died (%) | Odds ratio* (95% confidence interval) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurologic or neuromuscular conditions | 6.9 | 3.4 (2.8, 4.3) | <0.0001 |

| Cardiovascular conditions | 8.3 | 2.8 (2.3, 3.4) | <0.0001 |

| Respiratory conditions | 5.1 | 1.1 (0.9, 1.5) | 0.3859 |

| Renal and urologic conditions | 7.1 | 1.7 (1.3, 2.2) | <0.0001 |

| Gastrointestinal and hepatologic conditions | 4.0 | 0.64 (0.49, 0.83) | 0.0007 |

| Hematologic and immunologic conditions | 6.8 | 1.9 (1.5, 2.4) | <0.0001 |

| Metabolic conditions | 6.1 | 1.4 (1.1, 1.8) | 0.0043 |

| Congenital and genetic conditions | 5.0 | 1.1 (0.87, 1.5) | 0.356 |

| Oncologic conditions | 7.0 | 2.0 (1.5, 2.5) | <0.0001 |

| Technology dependence | 5.5 | 1.1 (0.83, 1.4) | 0.5649 |

| Solid organ transplant | 7.4 | 1.5 (1.1, 2.2) | 0.0124 |

Adjusted for individual hospital effect, age group, and sex using multivariable mixed-effects logistic regression model.

Discussion

In a nationally representative cohort of pediatric sepsis patients, we showed that the proportion with a chronic disease has increased compared with prior studies (1,2,15), and over 68% of admissions now have at least one chronic disease. We also found that patients with severe sepsis and septic shock or sepsis with identified organ dysfunction had a higher prevalence of chronic disease than those with sepsis without identified organ dysfunction. This underscores the continued national shift in the burden of sepsis from previously healthy to chronically ill children (1,4,5). In contrast, the overall hospital mortality and the hospital mortality across various subgroups is lower compared with prior estimates (2,15,16).

Our findings highlight the divergent outcomes in previously healthy and chronically ill children with sepsis. In the analysis of the 7-state data in 1995 (1), 49.7% of the pediatric sepsis cases had a chronic disease and the hospital mortality in previously healthy patients and those with chronic disease was 8.0% and 12.9%, respectively. The more recent analysis of the 2003 KID (15) database found that 34.1% of the cohort with severe sepsis had a chronic disease and hospital mortality in previously healthy patients and those with a chronic disease of 2.3% and 7.8%, respectively, with an overall hospital mortality rate of 4.2%. We showed that 68.6% of the pediatric sepsis cases had a chronic disease and their hospital mortality was 5.1%, compared with a hospital mortality of 0.7% in previously healthy patients. Our data source and methodology for sepsis identification, chronic diseases, and mortality were similar to this previous study, although our study did include some patients with a diagnosis of sepsis alone without administrative coding for organ dysfunction. The lower mortality rate in previously healthy children in our study may reflect lower illness severity than in the analysis of sepsis in the KID database, but may also be indicative of coding changes, improvements in sepsis recognition or advances in pediatric ICU care (17,18).

Patients with underlying oncologic disease, transplant patients, and those with hematologic, immunologic, metabolic, neurologic, cardiac, or renal disease had a significantly increased risk of hospital mortality in multivariable analyses. Some of these findings, such as the association between oncologic or cardiac disease and hospital mortality, are consistent with previous studies (7,8,21,22). However, the association between organ transplant, neurologic or renal disease and increased hospital mortality has not previously been evaluated in children. Patients with technology dependence did not have increased hospital mortality, and neither did patients with underlying pulmonary or gastrointestinal disease. There are multiple potential explanations for the increased risk of hospital mortality in children with sepsis and chronic disease. These patients may have limited organ reserve, a dysregulated immune response, or sepsis may represent a terminal event for families of chronically ill children and they may elect not to escalate care or to withdraw care.

Children with chronic diseases represent a significant proportion of all children admitted to the hospital and to the pediatric ICU (19,20). The higher hospital mortality among specific groups of patients with chronic disease highlights the importance of increased vigilance and early aggressive therapy in these groups and the importance of immunosuppression and underlying organ dysfunction in risk stratification for pediatric patients with sepsis. An important implication of our findings is the need to conduct future studies to examine long-term morbidity and mortality, because the reduction in hospital mortality observed in our study may not persist after hospital discharge, especially among children with chronic disease.

Our study has several strengths. We used a nationally representative dataset and the national incidence was estimated using weights. This approach contrasts with prior analyses that may be less generalizable because they were limited to select states (1,2) or used data obtained from pediatric ICUs or academic centers alone (4,5). We used two coding strategies to identify sepsis because both approaches have limitations. Although prior evaluations have shown a significant difference in mortality using different coding approaches to identify severe sepsis and septic shock (12), our results were less disparate. The size of our study allowed for assessment of the association of multiple chronic disease states with hospital mortality using a multivariable model.

Our study has several limitations. Quantification of sepsis occurrence and outcomes is difficult using administrative data in both the pediatric (5) and adult population (23), with varying definitions of severity, and occurrence is complex. It is possible that some of the organ dysfunction that we identified as associated with sepsis may have been the result of another primary disease process, and this may lead to misclassification bias. We identified chronic diseases using diagnostic criteria for complex chronic conditions (13) during the sepsis admission rather than using a lookback approach (24). Thus, there is a possibility that some of these diagnoses could be a result of the episode of sepsis instead of associated with the development of the disease. We excluded the neonatal population using neonatal diagnosis codes, but the possibility of unintentionally excluding some members of the infant population or unintentionally including members of the immediate antenatal population due to variability in coding strategies in this population also remains. Our estimate of hospital mortality is limited to in- hospital mortality and likely underrepresents long-term mortality in critically ill children. It is likely that there is a component of unmeasured confounding and confounding by indication in the mortality model, as chronic diseases are an important risk factor for pediatric fatality independent of sepsis, and we were unable to fully control for this effect in the study design. Finally, we were unable to distinguish between community-acquired and nosocomial sepsis and septic shock.

In conclusion, this analysis of a large and nationally representative dataset showed that pediatric sepsis patients often have chronic diseases and observed differential hospital mortality between previously healthy children and those with chronic disease with sepsis. Future evaluations should examine long-term mortality of pediatric sepsis patients, especially because a large proportion of pediatric sepsis patients have chronic diseases and sepsis may worsen their long-term outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01GM097471 and R34GM107650) and the National Institutes of Health (R35GM119519).

List of abbreviations

- NRD

Nationwide Readmissions Database

- PICU

Pediatric Intensive Care Unit

- ICD-9 CM

International Classification of Diseases Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

- APRDRG

All-patient refined diagnosis-related group

- HCUP

Health Care and Utilization Project

- ECMO

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

Appendix 1: Combination codes for sepsis using infection and organ dysfunction

Infection (001-005, 008-018, 020-027, 030-041, 090-098, 100-104,110-112, 114-118, 320, 322-325, 420-421, 451, 461-465, 481-482, 485-486, 494, 510, 513, 540-542, 562.01, 562.03, 562.11, 562.13, 566-567, 569.5, 569.83, 572.0, 572.1, 575.0, 590, 597, 599.0, 601, 614-616, 681-683, 686, 711.0, 730, 790.7, 996.6, 998.5, 995.92, 999.3)

Organ dysfunction (785.5, 458, 96.7, 348.3, 293, 348.1, 287.4, 287.5, 286.9, 286.6, 570, 573.4, 584)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Portions of this study were presented at the 46th Critical Care Congress, January 21-25, 2017, Honolulu, Hawaii.

References

- 1.Watson RS, Carcillo JA, Linde-Zwirble WT, Clermont G, Lidicker J, Angus DC. The epidemiology of severe sepsis in children in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:695–701. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200207-682OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartman ME, Linde-Zwirble WT, Angus DC, Watson RS. Trends in the Epidemiology of Pediatric Severe Sepsis. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14:686–93. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3182917fad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruth A, McCracken CE, Fortenberry JD, Hall M, Simon HK, Hebbar KB. Pediatric Severe Sepsis: Current Trends and Outcomes From the Pediatric Health Information Systems Database*. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15:828–38. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiss SL, Fitzgerald JC, Pappachan J, Wheeler D, Jaramillo-Bustamante JC, Salloo A, et al. Global epidemiology of pediatric severe sepsis: the sepsis prevalence, outcomes, and therapies study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015 May 15;191:1147–57. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201412-2323OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balamuth F, Weiss SL, Neuman MI, Scott H, Brady PW, Paul R, et al. Pediatric severe sepsis in U.S. children’s hospitals. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15:798–805. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zinter MS, DuBois SG, Spicer A, Matthay K, Sapru A. Pediatric cancer type predicts infection rate, need for critical care intervention, and mortality in the pediatric intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2014 Oct;40:1536–44. doi: 10.1007/s00134-014-3389-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ascher SB, Smith PB, Clark RH, Cohen-Wolkowiez M, Li JS, Watt K, et al. Sepsis in young infants with congenital heart disease. Early Hum Dev. 2012 May;88(Suppl 2):S92–7. doi: 10.1016/S0378-3782(12)70025-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abou Elella R, Najm HK, Balkhy H, Bullard L, Kabbani MS. Impact of Bloodstream Infection on the Outcome of Children Undergoing Cardiac Surgery. Pediatr Cardiol. 2010 May 10;31:483–9. doi: 10.1007/s00246-009-9624-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sepsis Collaborative [Internet] [cited 2017 Sep 25]. Available from: https://www.childrenshospitals.org/sepsiscollaborative.

- 10.NRD Overview [Internet] [cited 2017 Mar 20]. Available from: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nrdoverview.jsp.

- 11.Shah BA, Padbury JF. Neonatal sepsis. Virulence. 2014 Jan 1;5:170–8. doi: 10.4161/viru.26906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balamuth F, Weiss SL, Hall M, Neuman MI, Scott H, Brady PW, et al. Identifying Pediatric Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock: Accuracy of Diagnosis Codes. J Pediatr. 2015;167:1295–1300.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, Hall M, Dai D. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:199. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-14-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.NRD Tutorial [Internet] [cited 2017 Feb 18]. Available from: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/tech_assist/nrd/index.html.

- 15.Odetola FO, Gebremariam A, Freed GL. Patient and hospital correlates of clinical outcomes and resource utilization in severe pediatric sepsis. Pediatrics. 2007;119:487–94. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watson RS, Carcillo J. Scope and epidemiology of pediatric sepsis. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:S3–5. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000161289.22464.C3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Oliveira CF, de Oliveira DSF, Gottschald AFC, Moura JDG, Costa GA, Ventura AC, et al. ACCM/PALS haemodynamic support guidelines for paediatric septic shock: an outcomes comparison with and without monitoring central venous oxygen saturation. Intensive Care Med. 2008 Jun 28;34:1065–75. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han YY, Carcillo JA, Dragotta MA, Bills DM, Watson RS, Westerman ME, et al. Early Reversal of Pediatric-Neonatal Septic Shock by Community Physicians Is Associated With Improved Outcome. Pediatrics. 2003;112 doi: 10.1542/peds.112.4.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Odetola FO, Gebremariam A, Davis MM. Comorbid illnesses among critically ill hospitalized children: Impact on hospital resource use and mortality, 1997–2006. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2010;11:457–63. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181c514fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen E, Berry JG, Camacho X, Anderson G, Wodchis W, Guttmann A. Patterns and Costs of Health Care Use of Children With Medical Complexity. Pediatrics. 2012;130 doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zinter MS, DuBois SG, Spicer A, Matthay K, Sapru A. Pediatric cancer type predicts infection rate, need for critical care intervention, and mortality in the pediatric intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2014 Oct 15;40:1536–44. doi: 10.1007/s00134-014-3389-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zinter MS, Dvorak CC, Spicer A, Cowan MJ, Sapru A. New Insights Into Multicenter PICU Mortality Among Pediatric Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Patients. Crit Care Med. 2015 Sep;43:1986–94. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whittaker S-A, Mikkelsen ME, Gaieski DF, Koshy S, Kean C, Fuchs BD. Severe sepsis cohorts derived from claims-based strategies appear to be biased toward a more severely ill patient population. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:945–53. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827466f1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Preen DB, Holman CDJ, Spilsbury K, Semmens JB, Brameld KJ. Length of comorbidity lookback period affected regression model performance of administrative health data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006 Sep;59:940–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.