Abstract

Objectives

To assess providers’ recommendations as to comfort care versus medical and surgical management in clinical scenarios of newborns with severe bowel loss and to assess how a variety of factors influence providers’ decision making.

Study design

We conducted a survey of pediatric surgeons and neonatologists via the American Pediatric Surgical Association and American Academy of Pediatrics Section of Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine. We examined how respondents’ recommendations were affected by a variety of patient and provider factors.

Results

288 neonatologists and 316 pediatric surgeons responded. Irrespective of remaining bowel length, comfort care was recommended by 73% of providers for a premature infant with necrotizing enterocolitis and 54% for a full-term infant with midgut volvulus. Presence of comorbidities and earlier gestational age increased the proportion of providers recommending comfort care. Neonatologists were more likely to recommend comfort care than surgeons across all scenarios (odds ratio 1.45–2.00, P < .05), and this difference was more pronounced with infants born closer to term. In making these recommendations, neonatologists placed more importance on neurodevelopmental outcomes (p<0.001), and surgeons emphasized experience with long-term quality of life (p<0.001).

Conclusion

Despite a contemporary survival of >90% in infants with intestinal failure, a majority of providers still recommend comfort care in infants with massive bowel loss. Significant differences were identified in clinical decision-making between surgeons and neonatologists. These data reinforce the need for targeted education on long-term outcomes in intestinal failure to neonatal and surgical providers.

Keywords: Intestinal failure, premature infant

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) can lead to significant bowel loss and persistent intestinal failure (IF). Long-term survival and clinical outcomes of infants with IF have improved over recent decades, though significant chronic morbidity remains. (1,2) A portion of this improvement in survival is related to prevention and treatment of parenteral nutrition-associated liver disease, and centralization of care at multidisciplinary IF centers.(1–3)

Despite these recent advances, there is currently no standard of care defining the minimum length of residual bowel for which comfort care should be recommended in the neonate with NEC and significant bowel loss. Individual neonatologists and pediatric surgeons make recommendations to families on a case-by-case basis. Evidence to guide the clinical decision making of neonatologists and pediatric surgeons in this scenario, and literature describing how providers arrive at these recommendations is lacking. Additionally, because IF care has become more centralized, neonatologists and pediatric surgeons outside of specialized centers may be less familiar with the contemporary long-term prognosis in this population.

To address these questions, we designed a survey for both neonatal and pediatric surgical providers. We hypothesized that there would be significant intra- and inter-disciplinary heterogeneity in the care recommendations from both groups concerning neonates with severe NEC and significant bowel loss. Furthermore, we hypothesized that the factors deemed important in the decision-making process would differ between disciplines.

Methods

An anonymous web-based survey was created to assess provider recommendations regarding comfort care versus full medical and surgical management in several clinical scenarios. First, scenarios were provided describing infants with varied disease processes (NEC, midgut volvulus), comorbidities [none, bilateral grade IV intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), severe respiratory distress syndrome (RDS)], and gestational ages (25 weeks, 32 weeks, full term). In each scenario, respondents were asked for the residual bowel length (<30 cm, <20 cm, <10 cm, or never) at which they would recommend comfort care over full medical and surgical management. Second, we asked respondents to rate the importance of a variety of factors influencing their decision making. Third, respondents were asked to report how capable they felt of discussing with families various topics pertinent to decision making surrounding prematurity and IF. Fourth, respondents were asked for opinions (agree, disagree, or don’t know) on several statements regarding childhood outcomes of premature infants with minimal residual bowel. Finally, we queried respondents for demographic information including specialty, practice setting, experience, and availability of services within the participant’s institution including intestinal transplantation and intestinal rehabilitation programs. The Seattle Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board considered this study exempt. The full survey is available in the Appendix (available at www.jpeds.com).

The survey was distributed via electronic mail to 1130 pediatric surgeons through the American Pediatric Surgical Association and 2900 neonatology providers through the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine. The surveys were available to respondents from July 12 to August 8, 2016. All survey data was recorded in a secure REDCap database.

Analysis was performed using R 3.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna). Intergroup differences were evaluated using a Chi-Square test of independence if the answers had no obvious order and via proportional-odds logistic regression models (POMs) when such an order existed. For questions regarding comfort care decisions, more detailed POMs also adjusted for clinicians’ reported years of experience, as well as examined the effect of hospital characteristics. POM results are reported as odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). No formal multiple-testing adjustment was performed, but considering the number of questions the significance level was lowered to p<0.01, with 0.01<p<0.05 considered suggestive.

Results

Overall, 288 neonatologists and 316 pediatric surgeons responded to the survey, for response rates of 10% and 28% respectively. Among neonatology providers, 265 were attending neonatologists, 20 were neonatology fellows, two were advanced practitioners or nurses, and one was a neonatal hospitalist. 80% of respondents from both provider groups worked at academic hospitals. Approximately half of respondents reported that their current hospital had a pediatric IF program. More pediatric surgeons were trained at an institution with a pediatric IF program compared with neonatologists (40% vs 27%, p=0.001). Surgeons and neonatologists had a median of 15 and 18 years of post-fellowship clinical experience, respectively. Complete demographic information is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics

| Pediatric Surgeon | Neonatologist | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discipline | 316 (52%) | 288 (48%) | |

| Years Since Completion of Training | 0.02 | ||

| <5 | 78 (25%) | 54 (19%) | |

| 5–9 | 46 (16%) | 44 (15%) | |

| 10–19 | 72 (23%) | 45 (16%) | |

| 20–29 | 72 (23%) | 66 (23%) | |

| 30+ | 48 (15%) | 66 (23%) | |

| Academic Hospital | 260 (82%) | 221 (77%) | 0.11 |

| Hospital Type | <0.001 | ||

| Children’s Hospital | 164 (52%) | 104 (36%) | |

| Children’s Hospital within Adult Hospital | 137 (43%) | 120 (42%) | |

| Adult Hospital | 15 (5%) | 64 (22%) | |

| Pediatric Intestinal Failure Program | |||

| At Current Hospital | 167 (53%) | 136 (47%) | 0.04 |

| At Training Hospital | 127 (40%) | 77 (27%) | 0.001 |

| Intestinal Transplants Performed at Current Hospital | 49 (16%) | 30 (10%) | 0.009 |

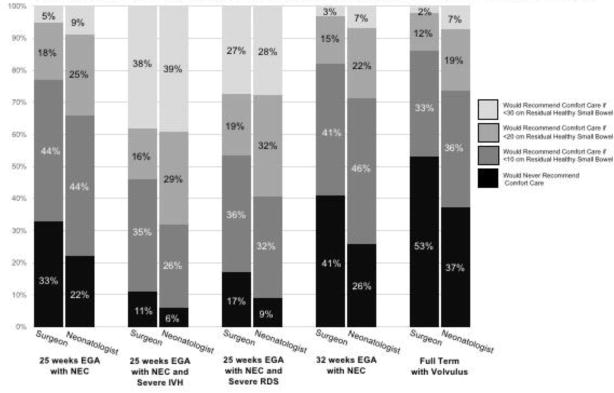

Providers’ responses as to whether they would recommend comfort care in the different clinical scenarios are outlined in Figure 1. For the 25-week premature infant with NEC and no comorbidities, 33% of surgeons and 22% of neonatal providers would recommend aggressive medical and surgical treatment regardless of bowel length. Providers from both disciplines were more likely to recommend comfort care for the 25-week premature infant with bilateral Grade IV IVH (p<0.001) and severe RDS on high frequency oscillatory ventilation (p<0.001) compared with a similarly premature infant with minimal residual small bowel free of additional comorbidities. Both neonatal and surgical providers were less likely to recommend comfort care in infants of later gestational age. For example, for a full-term infant with midgut volvulus and massive bowel loss, 53% of surgeons and 37% of neonatal providers would recommend full treatment regardless of bowel length compared with 27% and 22%, respectively, for a 25-week premature infant with no comorbidities.

Figure 1. Recommendations of Pediatric Surgeons and Neonatologists Across Various Scenarios.

The x-axis on the graph represents percentage of total respondents of each discipline. Each pair of bars on the y-axis compares the responses of pediatric surgeons and neonatologists to 5 different scenarios. Neonatologists were more likely to recommend comfort care than pediatric surgeons across all scenarios, and gestational age and presence of comorbidities also affected recommendations.

Neonatologists were more likely to recommend comfort care than surgeons across all scenarios (ORs ranging from 1.45–2.00, p<0.01 except for one scenario p=0.02, Figure 1). This recommendation difference was more pronounced with infants who were closer to term gestation. Neonatologists were twice as likely to recommend comfort care in the full-term infant with midgut volvulus compared with surgeons (OR 2.00, CI 1.47 – 2.73, p<0.001). In the 32-week and full-term scenarios, providers who had been practicing longer were more likely to recommend comfort care (OR 1.09 and 1.10, respectively). Further evaluation of the experience effect stratified by discipline revealed that it was significant only among neonatologists (ORs 1.13 and 1.17, p<0.01) and not among surgeons (ORs 1.05 and 1.03; p=0.3 and 0.5.). For the 25-week scenarios, the effect of experience pointed in the same direction among neonatologists but was weaker and not significant. Hospital type and presence of an intestinal transplant or IF program were not associated with providers’ recommendations.

Both surgeons and neonatal providers reported that the most important factors that influenced their clinical recommendations were experience with long-term survival of infants with minimal residual small bowel and interpretation of the current literature on long-term outcomes in this population (Table 2). Surgeons were more likely to cite experience with long-term quality of life in children with short bowel syndrome as an important factor (p<0.001) and neonatologists more frequently reported knowledge of long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes of extreme prematurity and/or short bowel syndrome (p<0.001).

Table 2.

Comparison of How Various Factors Influence Recommendations to Families

| Pediatric Surgeons | Neonatologists | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| My experience with long-term survival of infants with minimal residual small bowel | 0.83 | ||

| Very Important | 165 (52.2%) | 151 (52.4%) | |

| Important | 126 (39.9%) | 107 (37.2%) | |

| Somewhat Important | 21 (6.6%) | 29 (10.1%) | |

| Not at all Important | 4 (1.3%) | 1 (0.3%) | |

| My interpretation of the current literature with regards to long-term outcomes in pediatric short bowel syndrome | 0.17 | ||

| Very Important | 134 (42.4%) | 133 (46.2%) | |

| Important | 147 (46.5%) | 135 (46.9%) | |

| Somewhat Important | 34 (10.8%) | 20 (6.9%) | |

| Not at all Important | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Education on current outcomes in intestinal failure from a conference/Grand Rounds | 0.39 | ||

| Very Important | 60 (19.0%) | 48 (16.7%) | |

| Important | 115 (36.4%) | 114 (39.6%) | |

| Somewhat Important | 103 (32.6%) | 71 (24.7%) | |

| Not at all Important | 38 (12.0%) | 55 (19.1%) | |

| My experience with the long-term quality of life in children with short bowel syndrome | <0.001 | ||

| Very Important | 164 (51.9%) | 98 (34.0%) | |

| Important | 127 (40.2%) | 128 (44.4%) | |

| Somewhat Important | 23 (7.2%) | 51 (17.7%) | |

| Not at all Important | 2 (0.6%) | 11 (3.8%) | |

| My view on the potential for success in intestinal transplantation | <0.001 | ||

| Very Important | 113 (35.8%) | 71 (24.7%) | |

| Important | 144 (45.6%) | 133 (46.2%) | |

| Somewhat Important | 46 (14.6%) | 72 (25.0%) | |

| Not at all Important | 13 (4.1%) | 12 (4.2%) | |

| My knowledge of long term neurodevelopmental outcomes of extreme prematurity and/or short bowel syndrome | <0.001 | ||

| Very Important | 115 (36.4%) | 151 (52.4%) | |

| Important | 151 (47.8%) | 110 (38.2%) | |

| Somewhat Important | 44 (13.9%) | 26 (9.0%) | |

| Not at all Important | 6 (1.9%) | 1 (0.3%) | |

| My faith or religion | 0.71 | ||

| Very Important | 15 (4.7%) | 15 (5.2%) | |

| Important | 26 (8.2%) | 21 (7.3%) | |

| Somewhat Important | 46 (14.6%) | 39 (13.5%) | |

| Not at all Important | 229 (72.5%) | 213 (74.0%) | |

| My training | 0.31 | ||

| Very Important | 59 (18.7%) | 51 (17.7%) | |

| Important | 143 (45.3%) | 124 (43.1%) | |

| Somewhat Important | 74 (23.4%) | 63 (21.9%) | |

| Not at all Important | 40 (12.7%) | 50 (17.4%) | |

| The standard of care at my institution | 0.001 | ||

| Very Important | 51 (16.1%) | 53 (18.4%) | |

| Important | 113 (35.8%) | 137 (47.6%) | |

| Somewhat Important | 90 (28.5%) | 71 (24.7%) | |

| Not at all Important | 16 (19.6%) | 27 (9.4%) | |

| The infant’s family/social situation | 0.13 | ||

| Very Important | 64 (20.3%) | 84 (29.2%) | |

| Important | 118 (37.3%) | 84 (29.2%) | |

| Somewhat Important | 68 (21.5%) | 69 (24.0%) | |

| Not at all Important | 66 (20.9%) | 51 (17.7%) | |

Respondents felt most capable of discussing the option of comfort care and the risks of parenteral nutrition-associated liver failure, and least capable of discussing outcomes from intestinal transplantation and neurodevelopment outcomes in children with IF (Table 3). Compared with surgeons, a greater percentage of neonatal providers felt capable of discussing neurodevelopmental outcomes of both prematurity and IF (p<0.001). Neonatologists also felt more capable of discussing comfort care (p=0.001). More surgeons felt capable of discussing the long-term care needs for children with IF, the likelihood of patient survival and attaining enteral autonomy, and outcomes from intestinal transplantation (p<0.001).

Table 3.

Capability of Discussing Various Factors Important in Decision-Making with Families

| Pediatric Surgeons | Neonatologists | Sum | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Option of Comfort Care | 0.001 | |||

| Very Capable | 216 (68.4%) | 231 (80.2%) | 447 (74.0%) | |

| Capable | 92 (29.1%) | 51 (17.7%) | 143 (23.7%) | |

| Somewhat Capable | 8 (2.5%) | 6 (2.1%) | 14 (2.3%) | |

| Not at all Capable | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Outcomes from Intestinal Transplantation | <0.001 | |||

| Very Capable | 67 (21.2%) | 24 (8.3%) | 91 (15.1%) | |

| Capable | 146 (46.2%) | 101 (35.1%) | 247 (40.9%) | |

| Somewhat Capable | 99 (31.3%) | 122 (42.4%) | 221 (36.6%) | |

| Not at all Capable | 4 (1.3%) | 41 (14.2%) | 45 (7.5%) | |

| Long-Term Quality of Life for the Child | 0.003 | |||

| Very Capable | 117 (37.0%) | 80 (27.8%) | 197 (32.6%) | |

| Capable | 163 (51.6%) | 155 (53.8%) | 318 (52.6%) | |

| Somewhat Capable | 36 (11.4%) | 48 (16.7%) | 84 (13.9%) | |

| Not at all Capable | 0 (0%) | 5 (1.7%) | 5 (0.8%) | |

| Long-Term Quality of Life for the Family | 0.004 | |||

| Very Capable | 116 (36.7%) | 72 (25.0%) | 188 (31.1%) | |

| Capable | 148 (46.8%) | 157 (54.5%) | 305 (50.5%) | |

| Somewhat Capable | 49 (15.5%) | 52 (18.1%) | 101 (16.7%) | |

| Not at all Capable | 3 (0.9%) | 7 (2.4%) | 10 (1.7%) | |

| Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Intestinal Failure | <0.001 | |||

| Very Capable | 49 (15.5%) | 71 (24.7%0 | 120 (19.9%) | |

| Capable | 137 (43.4%) | 143 (49.7%) | 280 (46.4%) | |

| Somewhat Capable | 117 (37.0%) | 65 (22.6%) | 182 (30.1%) | |

| Not at all Capable | 13 (4.1%) | 9 (3.1%) | 22 (3.6%) | |

| Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Prematurity | <0.001 | |||

| Very Capable | 55 (17.4%) | 228 (79.2%) | 283 (46.9%) | |

| Capable | 133 (42.1%) | 57 (19.8%) | 190 (31.5%) | |

| Somewhat Capable | 119 (37.7%) | 3 (1.0%) | 122 (20.2%) | |

| Not at all Capable | 9 (2.8%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (1.5%) | |

| Risk of PN Associated Liver Disease | 0.026 | |||

| Very Capable | 160 (50.6%) | 173 (60.1%) | 333 (55.1%) | |

| Capable | 142 (44.9%) | 103 (35.8%) | 245 (40.6%) | |

| Somewhat Capable | 13 (4.1%) | 12 (4.2%) | 24 (4.1%) | |

| Not at all Capable | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.2%) | |

| Description of Long-term Care Needed in Intestinal Failure | <0.001 | |||

| Very Capable | 160 (50.6%) | 88 (30.6%) | 248 (41.1%) | |

| Capable | 136 (43.0%) | 159 (48.3%) | 275 (45.5%) | |

| Somewhat Capable | 17 (5.4%) | 50 (17.4%) | 67 (11.1%) | |

| Not at all Capable | 3 (0.9%) | 11 (3.8%) | 14 (2.3%) | |

| Likelihood of Survival with Bowel Resection and Full Medical Treatment | <0.001 | |||

| Very Capable | 129 (40.8%) | 80 (27.8%) | 209 (34.6%) | |

| Capable | 167 (52.8%) | 141 (49.0%) | 308 (51.0%) | |

| Somewhat Capable | 19 (6.0%) | 61 (21.2%) | 80 (13.2%) | |

| Not at all Capable | 1 (0.3%) | 6 (2.1%) | 7 (1.2%) | |

| Likelihood of Patient Attaining Intestinal Autonomy (full enteral nutrition) over time | <0.001 | |||

| Very Capable | 116 (36.7%) | 48 (16.7%) | 164 (27.2%) | |

| Capable | 162 (51.3%) | 131 (45.5%) | 293 (48.5%) | |

| Somewhat Capable | 38 (12.0%) | 90 (31.2%) | 128 (21.2%) | |

| Not at all Capable | 0 (0%) | 19 (6.6%) | 19 (3.1%) | |

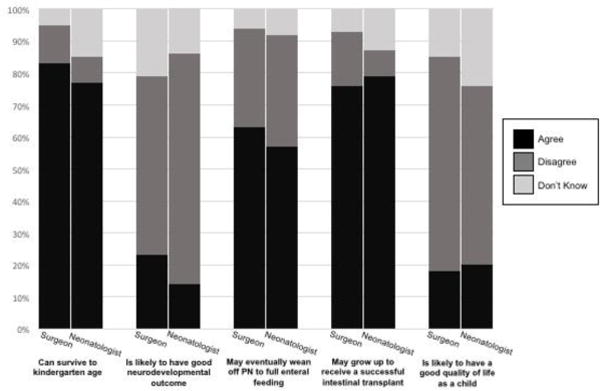

Eighty percent of survey respondents felt that a premature infant with minimal residual bowel could survive to kindergarten age and 60% felt that this child may eventually wean off PN (Figure 2). However, only 19% of participants responded that this child will likely have a good neurodevelopmental outcome and similarly only 19% of respondents thought this child would have a good quality of life. 77% of respondents felt that such a child may receive a successful intestinal transplant. Compared with surgeons, neonatal providers were more likely to disagree that a premature infant with minimal residual bowel is likely to have a good neurodevelopmental outcome (OR 2.04, p=0.001) and were more likely to express uncertainty regarding whether this child would survive to kindergarten age (OR 3.20, p<0.001).

Figure 2. Opinions of Pediatric Surgeons and Neonatologists on Several Statements Regarding Long-term Outcomes in Premature Infants with Minimal Residual Bowel.

The x-axis on the graph represents percentage of total respondents of each discipline. Each pair of bars on the y-axis compares the responses of pediatric surgeons and neonatologists to 5 different statements. Neonatologists were more likely to disagree that a premature infant with minimal residual bowel is likely to have a good neurodevelopmental outcome and were more likely to express uncertainty regarding whether this child would survive to kindergarten. Surgeons were more likely to disagree that this child may receive a successful intestinal transplant.

Discussion

Outcomes in children with IF have improved significantly over the past two decades(4). Survival into school age and beyond is now a reasonable expectation even in children with the shortest bowel remnants(5). Studies have demonstrated improvements in the long-term prognosis for babies with severe NEC and that children with NEC as the underlying etiology for IF are more likely to attain enteral autonomy(6,7). However, these children require chronic intestinal rehabilitation, and some may go on to require intestinal transplantation. This ongoing care represents a significant utilization of health care resources, and the decision to proceed with full treatment of these patients in the early neonatal period has considerable long-term implications. Yet, the opinions and practices of pediatric surgeons and neonatologists about these important decisions have not been assessed in the current era of IF management. By exploring this in detail using survey methodology, our goal was to increase awareness of how different management strategies are utilized and identify areas where provider groups could benefit from targeted education.

The survey results demonstrate that a large number of surgical and neonatal providers would still recommend comfort care despite the improvements in long-term outcomes in IF management. We anticipated that a majority of respondents from both specialties would recommend comfort care in an extremely premature neonate with massive bowel loss from NEC and also in infants with significant comorbidities. However, this pattern persisted in older newborns with similar intestinal pathology. For example, 66% of providers would recommend comfort care for a 32-week infant with massive bowel loss due to NEC depending on bowel length, and 63% of neonatologists would recommend comfort care in a full-term infant with massive bowel loss due to midgut volvulus. These data are striking in that, even in the absence of extreme prematurity, survey respondents demonstrated a preference for comfort care in this population of infants. Although survey participants indicated their interpretation of current outcomes-based literature was an important factor in their responses, the most recent data from intestinal rehabilitation centers report >90% survival in patients similar to the hypothetical subjects presented in the survey(4,8–10).

The frequent recommendation for comfort care in this survey may indicate that respondents were incorporating their views on overall quality of life for long-term pediatric IF survivors. Although robust trends toward increased survival have been reported(1–3,8,10), few publications have addressed what this survival looks like. Data are conflicted as to the neurodevelopmental outcomes of these children and the quality of life over time for the child and the family, although these studies do not preclude favorable outcomes in this population(11–14). In addition, surgical NEC has been associated with neurodevelopmental impairment independent of IF(15–17). Indeed, although the majority of survey respondents felt that a premature baby with minimal residual bowel could survive to school age and that this baby could receive a successful intestinal transplant, only a small percentage reported that this child could have a good neurodevelopmental outcome and a good quality of life.

Remaining bowel length also made a difference in provider recommendations. Compared with scenarios in which <10 cm of viable small bowel survived, providers were more likely to recommend full clinical treatment in infants with 20 cm and 30 cm of remnant small bowel. Although respondents were likely incorporating their beliefs as to the long-term prognosis and prospect of enteral autonomy with different bowel lengths into their recommendations, emerging data demonstrate that the improvements in long-term survival also extend to ultrashort bowel syndrome(5,18). Many such patients remain parenteral nutrition-dependent but still attend school and participate in sports and other typical childhood activities. Targeted education to neonatal and surgical providers on long-term survival even in the most severe forms of short bowel syndrome would likely be valuable and contribute to the clinical care of these patients.

Across all scenarios, neonatologists were significantly more likely than pediatric surgeons to recommend comfort care. Neonatologists were also more likely to recommend comfort care in neonates with longer lengths of residual small bowel. This relationship became stronger as the gestational age of the infant increased in our survey scenarios. In this way, the survey identified striking disagreements between surgeons and neonatologists as to recommendations for comfort care in older neonates such as the 32-week gestation infant and the full-term newborn.

The survey data provide some foundation for reasons behind these differences in provider responses. Neonatologists were more likely to indicate that neurodevelopmental outcomes influenced their survey responses and were less likely to agree that a good neurodevelopmental outcome was possible in this population. It is possible that neonatologists’ knowledge of the literature on neurodevelopmental impairment in premature infants with NEC can explain their increased predilection to recommend comfort care. Alternatively, surgeons may prefer operative intervention because of their technical expertise or familiarity with the operating room. As this study utilized online survey methodology, provider groups may have interpreted the questions or clinical scenarios differently.

The differences in recommendations between disciplines in the present study have been noted previously with other diagnoses that carry an uncertain prognosis. Cummings et al compared opinions regarding intestinal transplant for neonates with intestinal failure between neonatologists and pediatric surgeons(19). They found that for an otherwise healthy premature neonate with NEC totalis, 32% of neonatologists and 19% of surgeons would opt to close the abdomen and proceed with comfort care without discussing intestinal rehabilitation or transplant. The most common reasons cited for not offering transplant were long-term burden to the child and the family which is similar to the concerns about quality of life in our survey. Previous studies have demonstrated that neonatologists are less optimistic than cardiologists regarding quality of life after surgical treatment of hypoplastic left heart syndrome and significantly less likely to recommend surgical intervention(20,21). A similar pattern was identified when comparing neonatologists’ and pulmonologists’ attitudes towards management of infants with Trisomy 18(22).

This study has several limitations. The response rate, particularly among neonatologists, was low (10% for neonatologists, 28% for surgeons). Our response rate is consistent with the typical response rate for electronic surveys distributed by the AAP Section on Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine(23). Response bias may be inherent in our survey, such that neonatologists and surgeons who are more interested in this population may have been more likely to respond. This bias could result in an overestimation of the knowledge and familiarity of both groups with issues related to IF. In addition, the survey asked about respondents’ views on patients with “minimal residual bowel” and this may have been interpreted differently across survey participants. Finally, respondents may not fully have understood the practical differences between different bowel lengths in the various scenarios thereby leading to bias in their likelihood to recommend comfort care.

Despite these limitations, assuming that providers answered the survey scenarios with the best interest of the child and family in mind, these differences in provider attitudes likely translate to variances in clinical care. These differences also suggest that the infant’s physician team has a contrasting view of long-term outcomes in this diagnosis. In the absence of definitive, long-term data on the outcomes of these children, the discrepancy in provider recommendations emphasizes the need for a multi-disciplinary team approach when these patient care scenarios arise in the operating room and the neonatal intensive care unit. Even though the 2 groups have a shared knowledge base from training and experience, neonatologists and pediatric surgeons also have complementary strengths and weaknesses as demonstrated by the survey data. Both sets of providers have their own specialty-specific knowledge of the literature and can provide important prognostic details to the family about what long-term survival would look like. Ideally, parental counseling should be tailored to each family’s specific situation with thorough yet succinct discussions involving both a surgeon and a neonatologist together. Given the recent advances in intestinal failure management, it is equally important to include a physician with experience or advanced training in intestinal rehabilitation or intestinal transplant in the conversation with the family.

This study also highlights the paucity of data as to the functional outcomes of long-term survivors with pediatric IF. Few studies have reported the quality of life and neurodevelopmental outcomes in this population as they enter school age. Most of our survey participants believed that survival into childhood was possible in this population but had a pessimistic view of the quality of life in surviving infants. This view likely affected respondents’ recommendations for comfort care in the different scenarios. Now that pediatric IF has become a chronic disease, there is a pressing need to fully define the long-term natural history in these children. Formal prospective evaluation of neurocognition and quality of life in this population should be prioritized.

Acknowledgments

Funded by ITHS, the National Institutes of Health Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1 TR002319).

Abbreviations

- NEC

Necrotizing enterocolitis

- IF

Intestinal Failure

- PN

Parenteral nutrition

- POM

Proportional-odds logistic regression model

- OR

Odds ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

Appendix

Attitudes surrounding the surgical and medical management of neonates with intestinal failure

Dear Neonatology and Pediatric Surgical Colleagues,

There is wide variation in opinion regarding decisions of whether to proceed with full medical and surgical treatment or comfort care in infants with severe necrotizing enterocolitis and massive bowel loss. In the past decade, long-term outcomes of intestinal failure in children have improved dramatically. We are seeking your thoughts on the optimal care for infants with massive bowel loss from necrotizing enterocolitis. This study is being conducted by neonatologists and pediatric surgeons at Seattle Children’s Hospital and University of Washington Medical Center.

The survey should take approximately 5 minutes to complete. It consists of patient scenarios and questions about care options in this population followed by a brief demographic survey. The survey is anonymous and has been reviewed by the Institutional Review Board at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

At the end of the survey you may choose to enter a raffle for an Apple Watch. To ensure anonymity of the surveys, entry into the raffle will not be linked with survey responses.

Please contact us with any questions or concerns at gillian.pet@seattlechildrens.org.

Thank you for your participation!

Gillian C. Pet MD, Neonatology Fellow; Patrick J. Javid MD, Pediatric Surgeon; Ryan M. McAdams MD, Neonatologist;

Adam Goldin MD, Pediatric Surgeon; Lilah Melzer, Medical Student

A premature baby who is 2 weeks old has necrotizing enterocolitis requiring surgical intervention. In the following patient scenarios, please indicate when you would recommend comfort care rather than bowel resection with medical/surgical therapy for this patient. (For each scenario one answer only)

-

A baby born at 25 weeks gestation without other significant comorbidities

- If the baby had less than 10 cm of viable small bowel

- If the baby had less than 20 cm of viable small bowel

- If the baby had less than 30 cm of viable small bowel

- I would not recommend comfort care for this patient regardless of the length of viable residual bowel

-

A baby born at 25 weeks gestation with bilateral grade 4 intraventricular hemorrhages

- If the baby had less than 10 cm of viable small bowel

- If the baby had less than 20 cm of viable small bowel

- If the baby had less than 30 cm of viable small bowel

- I would not recommend comfort care for this patient regardless of the length of viable residual bowel

-

A baby born at 25 weeks gestation with severe respiratory distress syndrome requiring 80-100% oxygen and high frequency oscillatory ventilation since birth

- If the baby had less than 10 cm of viable small bowel

- If the baby had less than 20 cm of viable small bowel

- If the baby had less than 30 cm of viable small bowel

- I would not recommend comfort care for this patient regardless of the length of viable residual bowel

-

4a. Please rate how the following factors may influence your recommendations in the above scenarios:

Very important Important Somewhat Important Not At All Important My experience with long-term survival of infants with minimal residual small bowel My interpretation of the current literature with regards to long-term outcomes in pediatric short bowel syndrome Education on current outcomes in intestinal failure from a conference/Grand Rounds My experience with the long term quality of life in children with short bowel syndrome My view of the potential for success in intestinal transplantation My knowledge of long term neurodevelopmental outcomes of extreme prematurity and/or short bowel syndrome My faith or religion My training The standard of care at my institution The infant’s family/social situation b. Please list any other factors that may influence your recommendations to this family

OPEN FREE TEXT BOX HERE

- 5. Please rate how capable you would feel of discussing the following aspects of intestinal failure and/or prematurity with this family.

Very capable Capable Somewhat Capable Not At All Capable Option of comfort care Outcomes from Intestinal transplantation Long term quality of life for the child Long term quality of life for the family Neurodevelopmental outcomes in intestinal failure Neurodevelopmental outcomes in prematurity Risks of parenteral nutrition associated liver disease Description of the long term care needed in intestinal failure Likelihood of survival with bowel resection and full medical treatment Likelihood of patient attaining enteral autonomy (full enteral nutrition) over time - 6. Please rate your opinions on the following statements:

Agree Disagree I Don’t Know A premature infant with minimal residual bowel can survive to kindergarten age A premature infant with minimal residual bowel is likely to have a good neurodevelopmental outcome A premature infant with minimal residual bowel may eventually wean off of TPN to full enteral feeding. A premature infant with minimal residual bowel may grow up to receive a successful intestinal transplant A premature infant with minimal residual bowel is likely to have a good quality of life as a child -

7. A premature baby born at 32 weeks gestation without other significant comorbidities has necrotizing enterocolitis requiring surgical intervention. Please indicate when you would recommend comfort care rather than bowel resection with definitive medical/surgical therapy for this baby (choose one answer):

- If the baby had less than 10 cm of viable small bowel

- If the baby had less than 20 cm of viable small bowel

- If the baby had less than 30 cm of viable small bowel

- I would not recommend comfort care for this patient regardless of the length of viable residual bowel

-

8. A baby born at full term develops midgut volvulus at 10 days of age. Please indicate when you would recommend comfort care rather than bowel resection and definitive medical/surgical therapy to the baby’s family (Choose one answer only.)

- If the baby had less than 10 cm of viable small bowel

- If the baby had less than 20 cm of viable small bowel

- If the baby had less than 30 cm of viable small bowel

- I would not recommend comfort care for this patient regardless of the length of viable residual bowel

Demographics:

Please indicate your field

- Pediatric Surgery

- Neonatology

(will redirect to appropriate demographic questions

Surgery Demographics:

In what you did you graduate pediatric surgery fellowship?

-

Do you work in an academic practice that is affiliated with a university?

- Yes

- No

-

Which of the following best describes the hospital where you primarily work?

- Freestanding children’s hospital

- Children’s hospital within an adult hospital

- Adult hospital

In what state is the hospital where you primarily work located? (List of states/territories)

-

Do you or another surgeon at your hospital perform bowel lengthening procedures?

- Yes

- No

- I don’t know

-

Are pediatric intestinal transplants performed at the hospital where you work or in your hospital system?

- Yes

- No

- I don’t know

-

Does the hospital where you work or your hospital system have a dedicated pediatric intestinal failure/short bowel program?

- Yes

- No

- I don’t know

-

Did the hospital where you completed your pediatric surgery fellowship have a dedicated pediatric intestinal failure/short bowel program?

- Yes

- No

- I don’t know

-

Neonatology Demographics:

What type of practitioner are you?

- Attending Neonatologist

- Fellow

- Resident

- Hospitalist

- Other advanced practitioner (APN, NNP, PA, etc)

- Other (please specify)

In what year did you complete your neonatology training?

-

Do you work in an academic practice that is affiliated with a university?

- Yes

- No

-

Which of the following best describes the hospital where you primarily work?

- Freestanding children’s hospital

- Children’s hospital within an adult hospital

- Adult hospital

-

In what state is the hospital where you primarily work located?

- (List of states/territories)

-

What level (defined by the AAP Levels of Neonatal Care) is the NICU where you primarily work?

- Level II (limited to infants >32 weeks and >1500 grams without significant respiratory support)

- Level III (all ELBW infants that require mechanical ventilation, HFOV, iNO, specialty referrals)

- Level IV (all ELBW infants that fulfill level III criteria plus the ability to provide surgical repair for complex congenital or acquired conditions)

-

Is there a pediatric general surgeon at the hospital where you work or in your hospital system?

- Yes

- No

- I don’t know

-

Are pediatric intestinal transplants performed at the hospital where you work or in your hospital system?

- Yes

- No

- I don’t know

-

Does the hospital where you work or your hospital system have a dedicated pediatric intestinal failure/short bowel program?

- Yes

- No

- I don’t know

-

Did the hospital where you completed your neonatology fellowship training have a dedicated pediatric intestinal failure/short bowel program?

- Yes

- No

- I don’t know/not applicable

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Portions of this study were presented as a poster at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting, May 6–9, 2017, San Francisco, California.

References

- 1.Hess RA, Welch KB, Brown PI. Survival outcomes of pediatric intestinal failure patients: analysis of factors contributing to improved survival over the past two decades. Journal of Surgical. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Modi BP, Langer M, Ching YA, Valim C, Waterford SD, Iglesias J, et al. Improved survival in a multidisciplinary short bowel syndrome program. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2008 Jan;43(1):20–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sigalet D, Boctor D, Robertson M, Lam V, Brindle M, Sarkhosh K, et al. Improved Outcomes in Paediatric Intestinal Failure with Aggressive Prevention of Liver Disease. European Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2009 Oct 28;19(06):348–53. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1241865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duggan CP, Jaksic T. Pediatric Intestinal Failure. N Engl J Med. 2017 Aug 17;377(7):666–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1602650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanchez SE, Javid PJ, Healey PJ, Reyes J, Horslen SP. Ultrashort bowel syndrome in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013 Jan;56(1):36–9. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318266245f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khan FA, Squires RH, Litman HJ, Balint J, Carter BA, Fisher JG, et al. Predictors of Enteral Autonomy in Children with Intestinal Failure: A Multicenter Cohort Study. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2015 Jul;167(1):29–34.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sparks EA, Khan FA, Fisher JG, Fullerton BS, Hall A, Raphael BP, et al. Necrotizing enterocolitis is associated with earlier achievement of enteral autonomy in children with short bowel syndrome. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2016 Jan;51(1):92–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Javid PJ, Malone FR, Reyes J, Healey PJ, Horslen SP. The American Journal of Surgery. 5. Vol. 199. Elsevier Inc; 2010. May 1, The experience of a regional pediatric intestinal failure program: Successful outcomes from intestinal rehabilitation; pp. 676–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stanger JD, Oliveira C, Blackmore C, Avitzur Y, Wales PW. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 5. Vol. 48. Elsevier Inc; 2013. May 1, The impact of multidisciplinary intestinal rehabilitation programs on the outcome of pediatric patients with intestinal failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis; pp. 983–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oliveira C, de Silva NT, Stanojevic S, Avitzur Y, Bayoumi AM, Ungar WJ, et al. Change of Outcomes in Pediatric Intestinal Failure: Use of Time-Series Analysis to Assess the Evolution of an Intestinal Rehabilitation Program. J Am Coll Surg. 2016 Jun;222(6):1180–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.So S, Patterson C, Gold A, Rogers A, Kosar C, de Silva N, et al. Early neurodevelopmental outcomes of infants with intestinal failure. Early Hum Dev. 2016 Oct;101:11–6. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2016.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chesley PM, Sanchez SE, Melzer L, Oron AP, Horslen SP, Bennett FC, et al. Neurodevelopmental and Cognitive Outcomes in Children With Intestinal Failure. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016 Jul;63(1):41–5. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mutanen A, Kosola S, Merras-Salmio L, Kolho K-L, Pakarinen MP. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 11. Vol. 50. Elsevier Inc; 2015. Nov 1, Long-term health-related quality of life of patients with pediatric onset intestinal failure; pp. 1854–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanchez SE, McAteer JP, Goldin AB, Horslen S, Huebner CE, Javid PJ. Health-related quality of life in children with intestinal failure. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013 Sep;57(3):330–4. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182999961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hintz SR. Neurodevelopmental and Growth Outcomes of Extremely Low Birth Weight Infants After Necrotizing Enterocolitis. PEDIATRICS. 2005 Mar 1;115(3):696–703. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shah TA, Meinzen-Derr J, Gratton T, Steichen J, Donovan EF, Yolton K, et al. Hospital and neurodevelopmental outcomes of extremely low-birth-weight infants with necrotizing enterocolitis and spontaneous intestinal perforation. J Perinatol. 2011 Dec 8;32(7):552–8. doi: 10.1038/jp.2011.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wadhawan R, Oh W, Hintz SR, Blakely ML, Das A, Bell EF, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants with spontaneous intestinal perforation or surgical necrotizing enterocolitis. J Perinatol. 2013 Oct 17;34(1):64–70. doi: 10.1038/jp.2013.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Infantino BJ, Mercer DF, Hobson BD, Fischer RT, Gerhardt BK, Grant WJ, et al. Successful rehabilitation in pediatric ultrashort small bowel syndrome. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2013 Nov;163(5):1361–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cummings CL, Diefenbach KA, Mercurio MR. Counselling variation among physicians regarding intestinal transplant for short bowel syndrome. J Med Ethics. 2014 Oct;40(10):665–70. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2012-101269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kon AA, Ackerson L, Lo B. How pediatricians counsel parents when no “best-choice” management exists: lessons to be learned from hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004 May;158(5):436–41. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.5.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooper TR, Garcia-Prats JA, Brody BA. Managing disagreements in the management of short bowel and hypoplastic left heart syndrome. PEDIATRICS. 1999 Oct;104(4):e48. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.4.e48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hurley EH, Krishnan S, Parton LA, Dozor AJ. Differences in perspective on prognosis and treatment of children with trisomy 18. Am J Med Genet. 2014 Aug 6;164(10):2551–6. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feltman DM, Du H, Leuthner SR. Survey of neonatologists’ attitudes toward limiting life-sustaining treatments in the neonatal intensive care unit. Nature Publishing Group. 2011 Dec 15;32(11):886–92. doi: 10.1038/jp.2011.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]